The (no-longer-so-dark) Dark Ages:

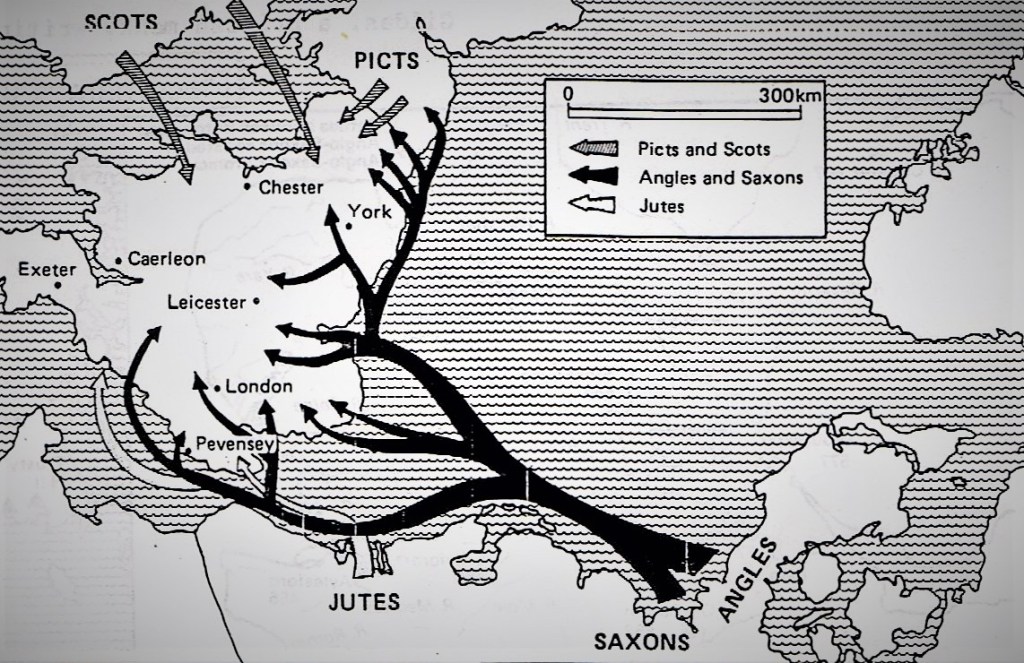

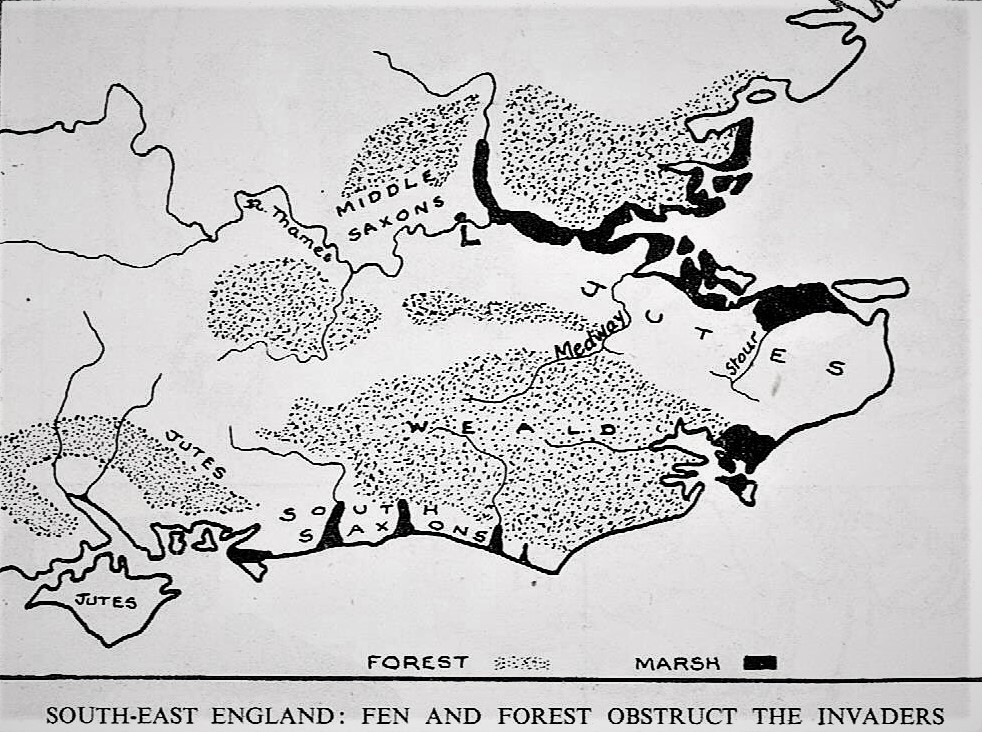

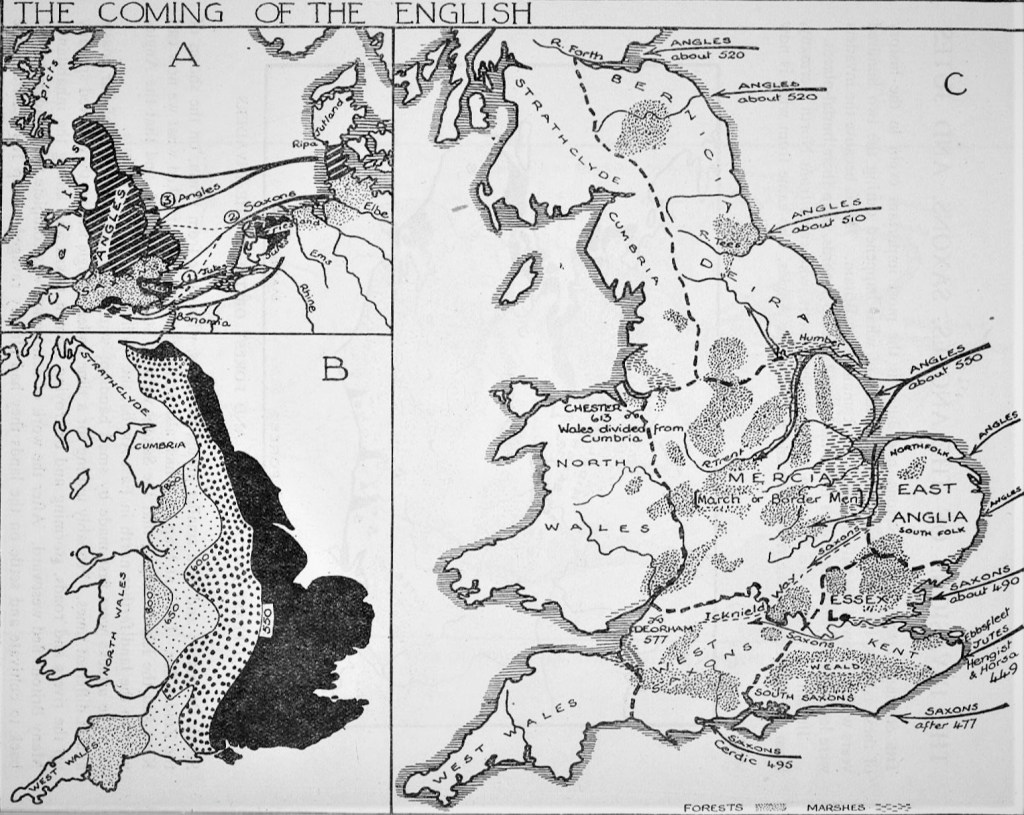

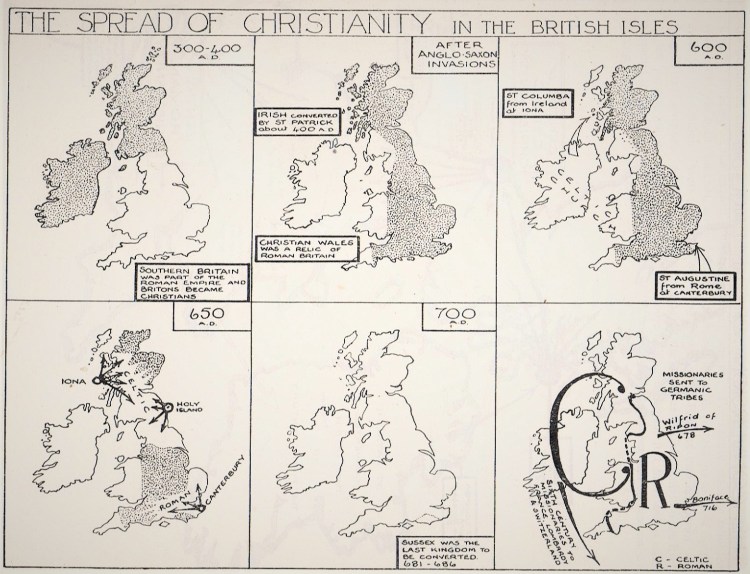

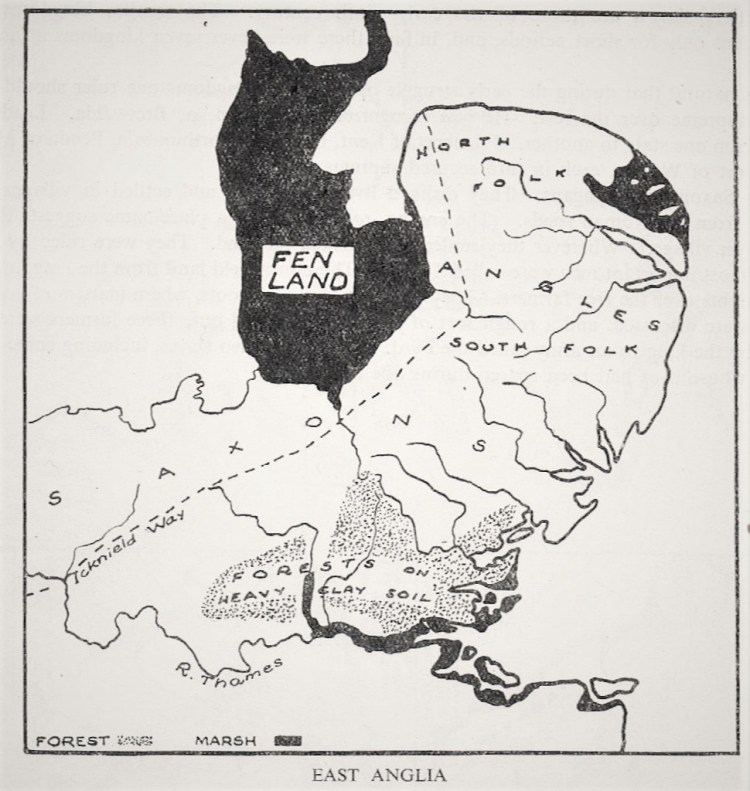

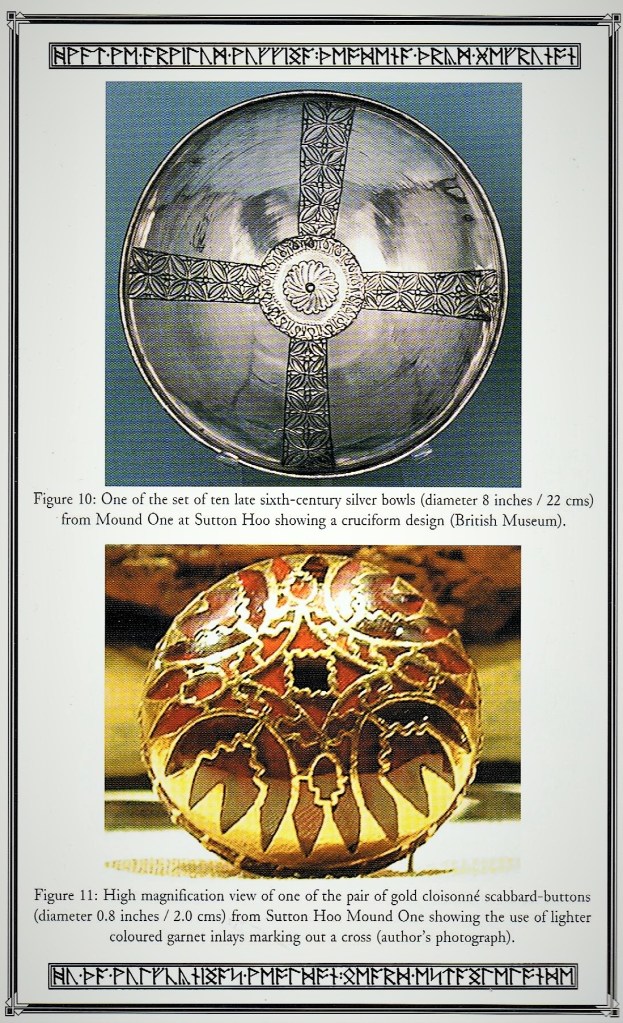

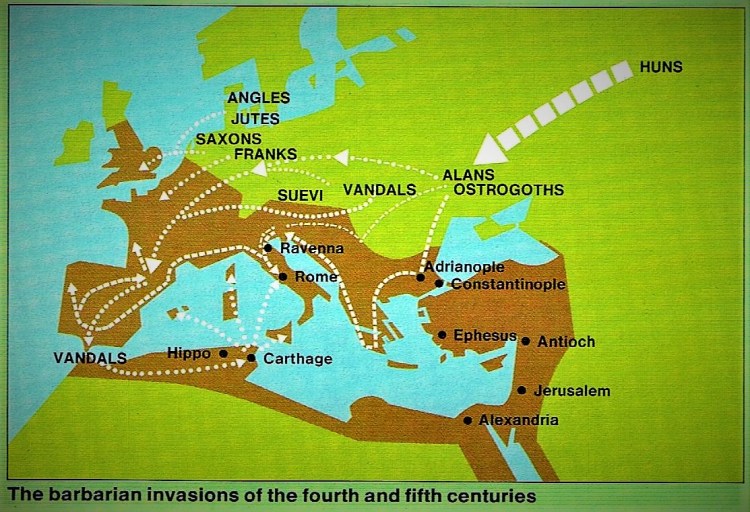

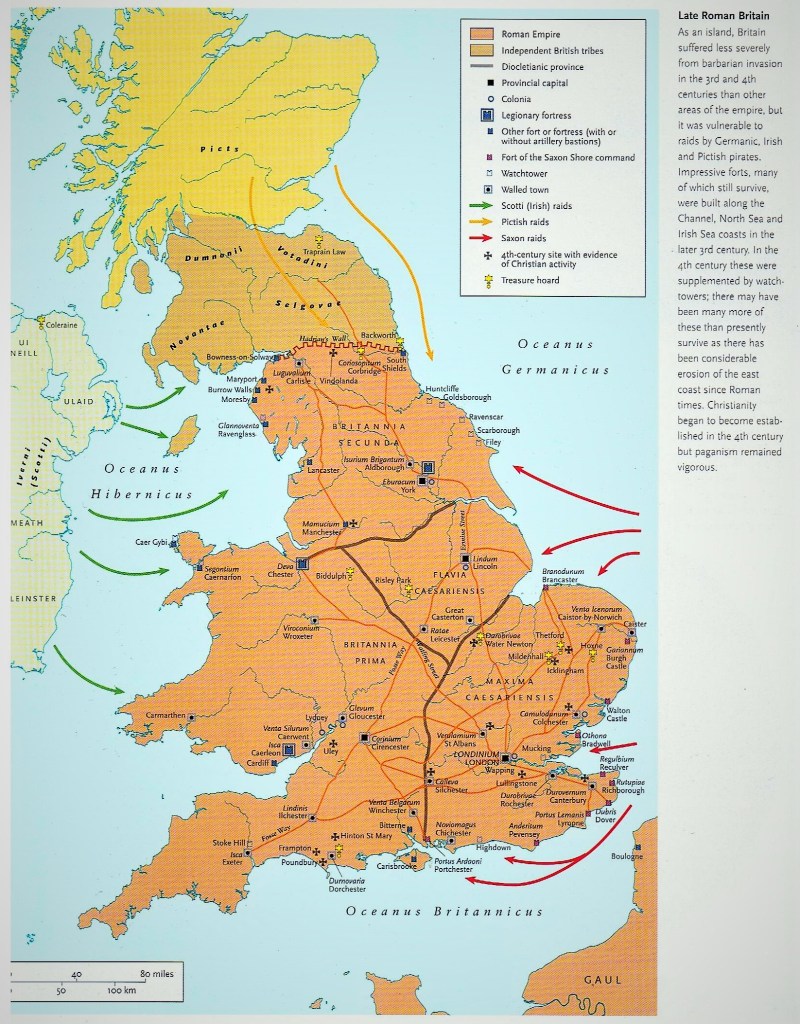

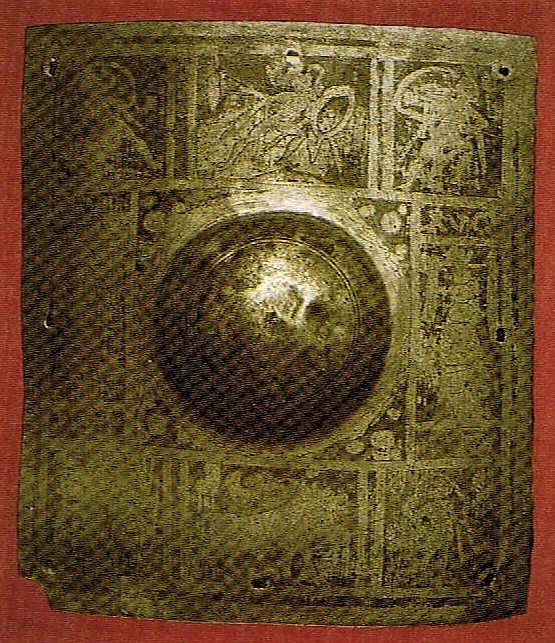

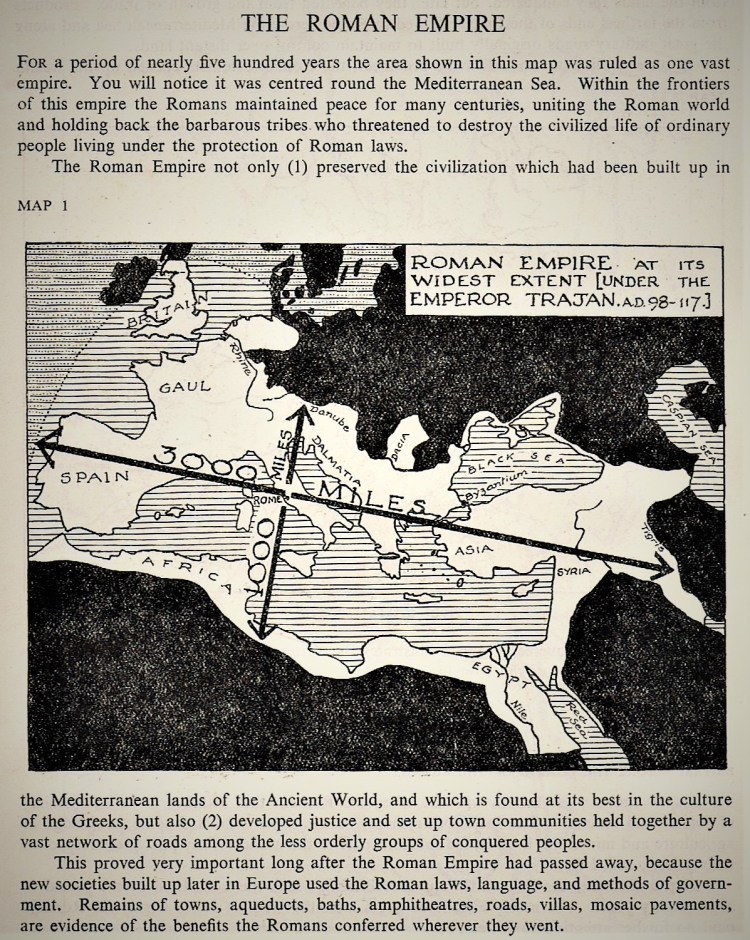

Since the discovery of the Sutton Hoo burial in Suffolk in 1939, archaeology has continued to shed light on the ‘Dark Ages’, where documentary evidence is lacking. The distribution of pagan fifth-century Anglo-Saxon burials indicates the probable areas of earliest English settlement in Britain. The English ‘advance’ continued throughout the period – though both English and British kingdoms fought amongst themselves as often as they fought against each other. British and Irish missionaries spread Christianity throughout the islands and were followed by continental and native English missionaries who also took part in the successful conversion of the pagan English in the later seventh century. In his 1977 book, A Short History of Suffolk, Derek Wilson wrote that ‘The Dark Ages’ was a term rightly frowned upon by historians. The implication that when the light of Roman civilization was extinguished Europe was plunged into four centuries of barbaric, heathen gloom could no longer be accepted. The Romans were conquerors; so were the Angles, the Saxons and the Jutes. Technically, the Romans had been more advanced, with a written language, in which they were able to record their disdain for the ‘barbarians’ without reply, but there the contrast ended. Therein, of course, lies the true meaning of the ‘dark ages’, since the historian is dependent for his or her ‘light’ on the chronicles left by scribes. But with the evidence unearthed by archaeologists, these centuries no longer remain quite so ‘dark’.

Northumbrian Ascendancy:

We know that Aethelfrith of Northumbria fought a significant battle against the Britons near Chester, the ‘City of Legions’, around the years 615-16. One consequence of Aethrlfrith’s campaign in Cheshire appears to have been that his dynastic enemy, Edwin of Deira, formerly, it seems, in exile in Mercia, where he had married the daughter of the Mercian king Cearl, now had to seek refuge elsewhere, further away from the growing power of Aethelfrith. This provides the background to the appearance of Edwin at the hall of the Wuffing king, Raedwald. A version of this story appears in an early Northumbrian document, The Life of St Gregory the Great, written at Whitby about twenty years before Bede completed his account. One historian has argued that this implies that Edwin’s exile at Raedwald’s royal hall was ‘a well-known fact of Northumbrian history’. Edwin may well have regarded Raedwald as his last hope of refuge against his ruthless enemy Aethelfrith. Bede goes on to tell us how Raedwald was harbouring his dynastic rival, an that Aethelfrith therefore despatched envoys offering the East Anglian king great wealth if he would order Edwin’s killing. Raedwald refused this pressure three times, the last of which when they were accompanied by dire threats of invasion and war. Bede portrays Raedwald as being on the verge of yielding up Edwin, but Edwin then received an offer to be ‘spirited away’ by an unknown friend who would guide the prince to a place where neither Raedwald nor Aethelfrith could reach him. But Edwin declined the offer, saying that he would not break faith with Raedwald, whom he held in such high honour that he would even be prepared to surrender his life to him.

Bede tells us how, then sitting alone outside the royal hall, Edwin was approached in his darkest hour by a mysterious stranger, who, like Ódin in disguise appearing to heroes of Scandinavian saga, made three prophecies in the form of three questions about his survival and future success. After the stranger had disappeared as mysteriously as he had now resolved to refuse to allow himself to be coerced by Aethelfrith’s bribes and threats. The friend then explained that it was Raedwald’s queen who had helped him make up his mind on the matter. As the Old English version of the story puts it,

She turned him from the evil direction of his mood, teaching him and admonishing that in no wise (it) became so noble (a) king and so excellent that he should his best friend put in need, (&) for gold sell (him), & his honour, for money’s greed & love forsake, which were dearer (than) all treasures.

T. Miller (ed.), The Old Version of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, p. 128.

Raedwald’s choice, then, was between peace with dishonour or war with honour, and his decision was to follow his pagan wife’s sound advice, in defence of the laws of hospitality and friendship. So Aethelfrith’s envoys were sent home for a third and last time, and Raedwald prepared for war. For Bede, this is just one episode in his narrative of his hero Edwin’s coming to the throne of Northumbria and his subsequent conversion to the church of Rome. Yet although the fate of the exiled prince Edwin may well have been one of the causes of the war between the two most powerful kings on the island of Britain at the time and can thus be seen as a contest between the overlord of north and the overlord of the south for the high kingship of all Britain.

The Battle of the River Idle:

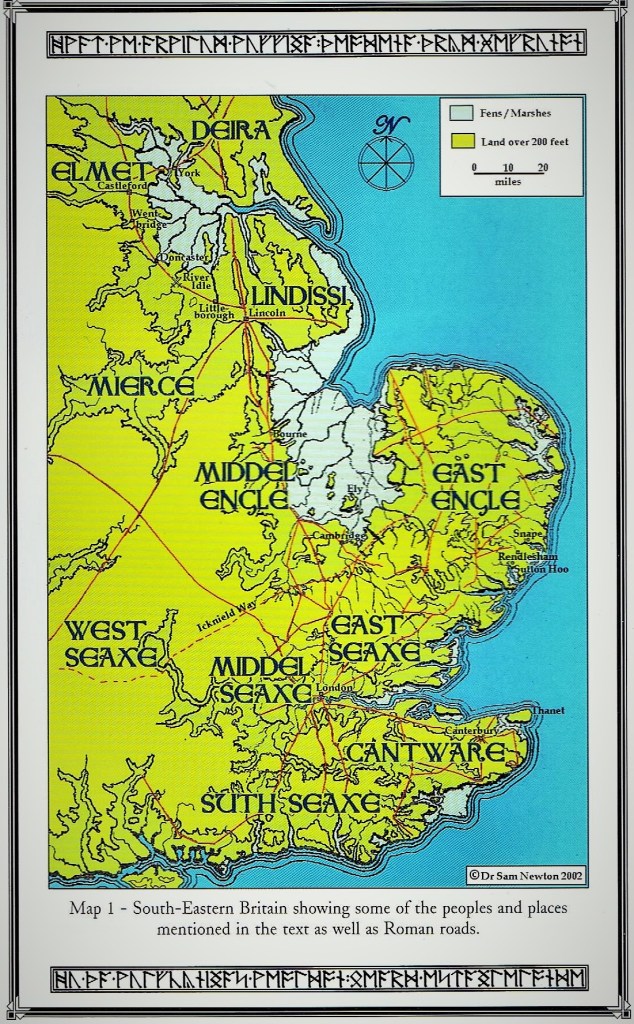

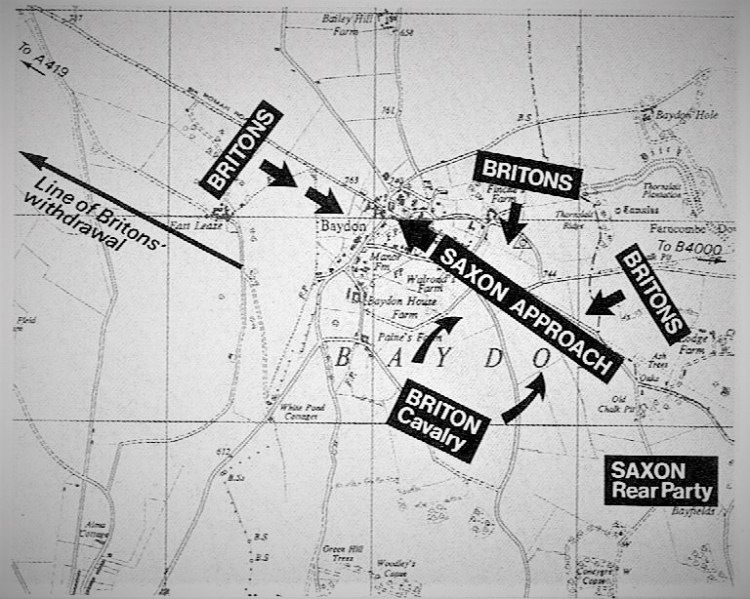

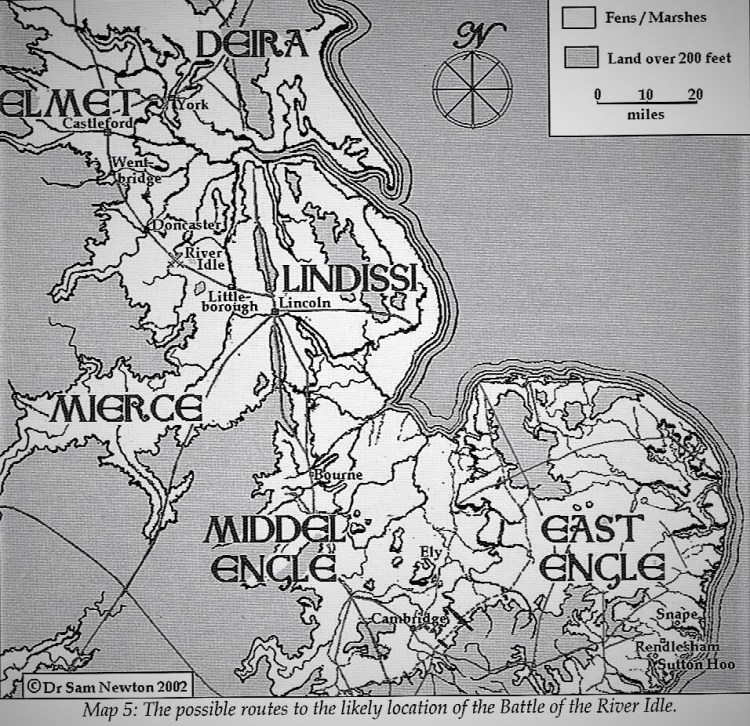

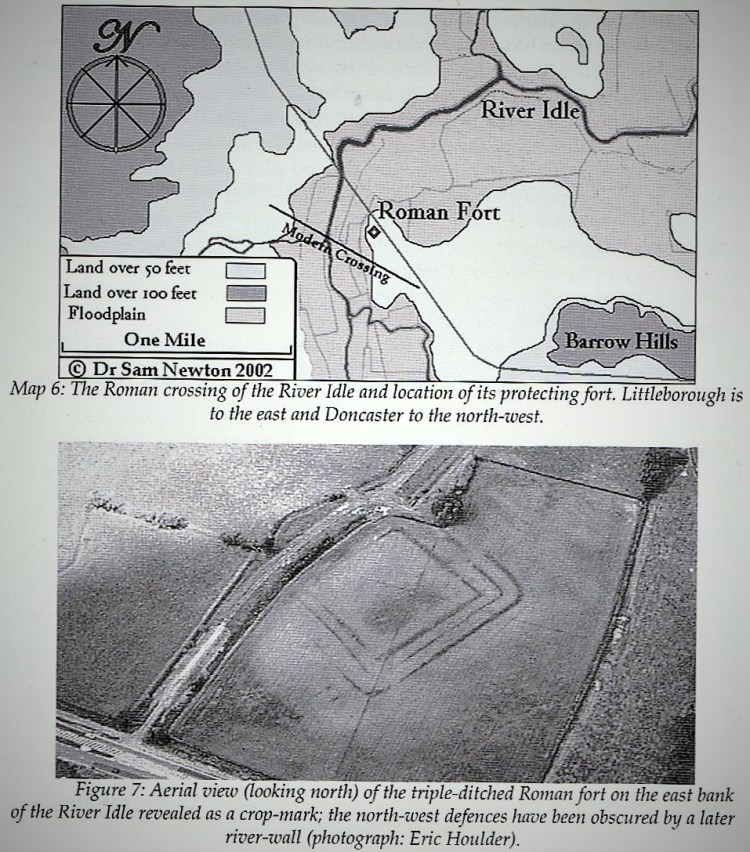

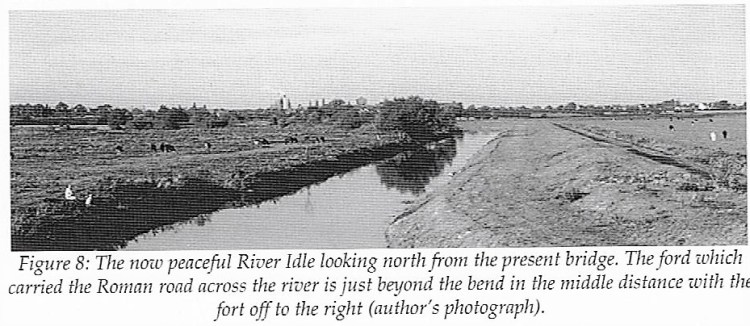

Bede’s account of the war between Raedwald and Aethelfrith is brief, and not without some Northumbrian bias. He states that Raedwald assembled a great army and marched north to meet Aethelfrith before the latter had time to summon his whole strength. It seems unlikely that the battle-hardened Northumbrian king would have launched an invasion force against East Anglia without sufficient forces to carry through his threat, but Aethelfrith’s forces were probably depleted after his recent campaign against the Britons both before and after the Battle of Chester. He may have, at the same time, have over-extended his military resources and become over-confident by his victories across the north. Bede tells us that the great battle between the Northumbrians and East Anglians took place on the Mercian border on the east bank of the River Idle. The River Idle, seemingly named for its meandering through a broad flood plain, was a tributary of the Trent, formed part of Mercia’s border in Bede’s time, but it is not clear that that was the case in 616-17. Yet the Idle appears to have formed a section of the border between two administrative areas during the Roman period, especially at the point where it is crossed by the main Roman road to the north. This road also crosses the great natural boundary of river and marsh formed by the Humber estuary and its various tributaries. It runs in a north-westerly direction from a point on Ermine Street just north of Lincoln, crossing the Trent at Littleborough, the Idle near Bawtry, the Don at Doncaster, the Went at Wentbridge, the Aire at Castleford, from where it runs north to Tadcaster. The road was of great strategic significance for the peoples both north and south of the Humber.

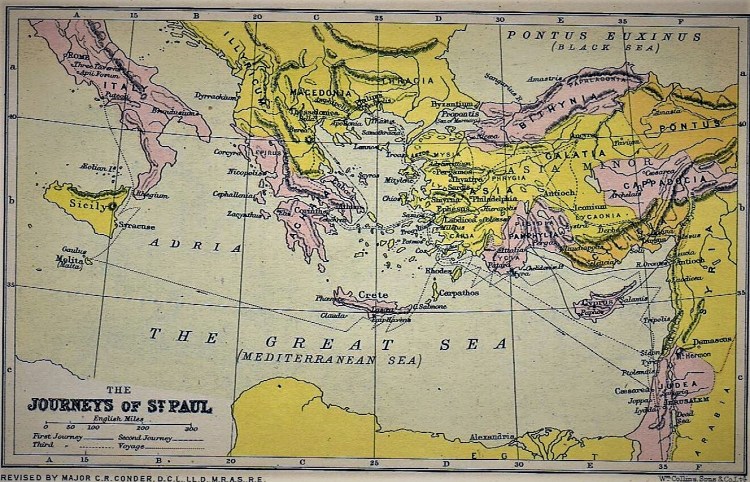

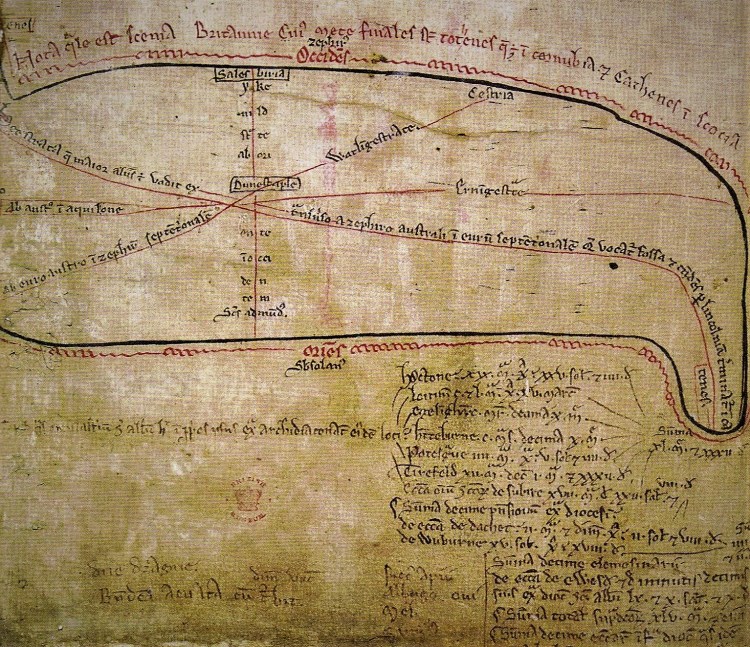

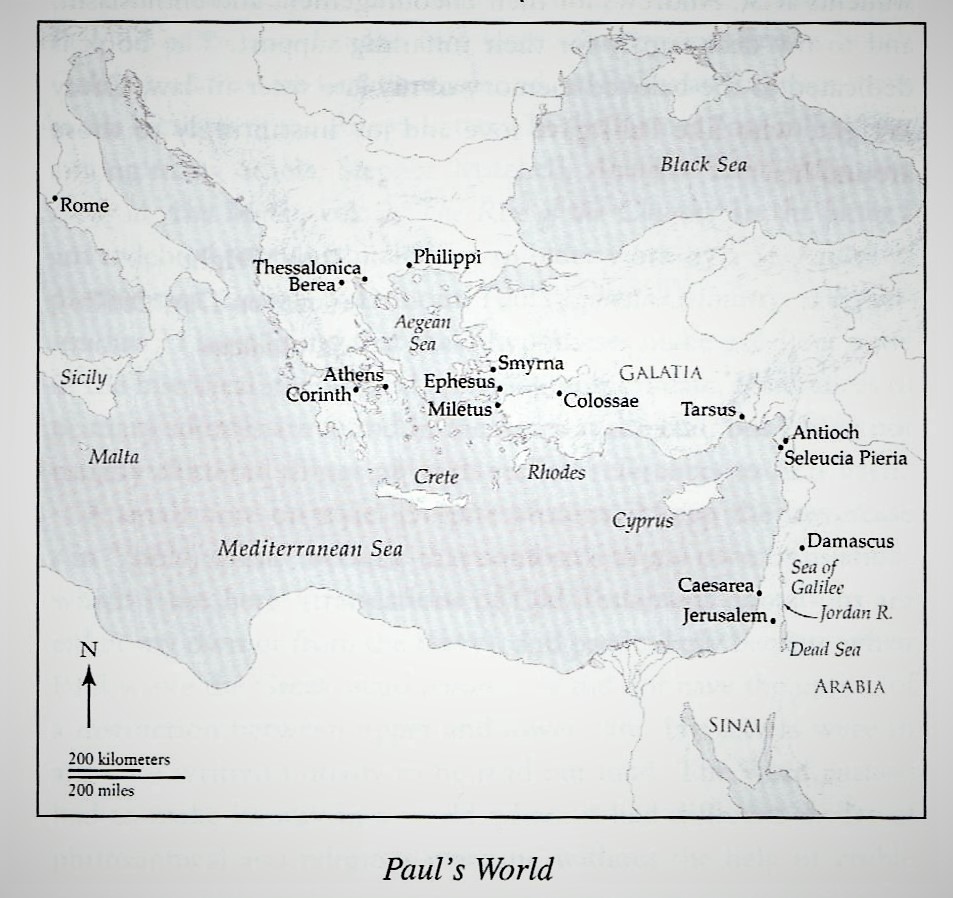

The suggestion is then that it was along this strategic road into the north that Raedwald advanced with his army to confront Aethelfrith. If this was the case, it becomes easier to trace his route on the ground, in the following series of maps. That Raedwald could organise and lead a long-distance military expedition on this scale implies that he was an experienced commander. His initial advance out of East Anglia could have followed two possible routes. He could have led his army overland along the Roman road from Cambridge along the southern edge of the great Fenland barrier until he came to Ermine Street, and thence along King Street via Bourne and Sleaford to Lincoln. Alternatively, he could have advanced more rapidly if he used a fleet using the former Roman army ferry crossing from Norfolk to Lincolnshire, approaching Lincoln from the east. The old Roman city of Lincoln then formed part of the kingdom of Lindsey, but it is not clear whether Raedwald’s overlordship extended over ‘Lindissi’. By whichever means he arrived at Lincoln, from the city Raedwald would have marched north along Ermine Street and then turned north-west towards Littleborough, a stronghold some eight miles down the road at the paved ford over the Trent. The river Idle crossing was twelve miles up the road from Littleborough and it was there that the battle with Aethelfrith is likely to have taken place. From the fourth century, this crossing had was controlled from its east bank by a Roman fort enclosing an area of about half an acre and protected by triple ditches, still visible from the air today.

Bede states specifically that the battle was fought on the east bank of the River Idle, which would place it in the same location as the Roman fort if Raedwald had been coming up the road from Littleborough. Bede’s statement would also imply that Aethelfrith would have been fighting with his back to the river, which would have put him at a tactical disadvantage. It is possible that the fort was still usable as a strong point at this time, and, if so, Aethelfrith may have refortified and occupied it to strengthen his position. Bede also tells us that there were two royal casualties; Raegenhere, and Aethelfrith himself, both of whom were killed in the clash of arms, but Bede gives us no more detail of the battle itself. For that, we have to rely upon an Old English poem, now lost, but which was available to the twelfth-century historian Henry of Huntingdon. In his Historia Anglorum, Henry refers implicitly to an independent vernacular account of the battle when he states, “it is said that the River Idle ran red with English blood”. Henry then provides a detailed report of the battle:

The fierce king, Ethelfrid (Aethelfrith), indignant that anyone should venture to resist him, rushed on the enemy boldly, but not in disorder, with a select body of veteran soldiers, though the troops of Raedwald made a brilliant and formidable display, marching in three bodies, with fluttering standards and bristling spears and helmets, while their numbers greatly exceeded their enemies’.

The king of the Northumbrians, as if he had found an easy prey, at once fell on those columns of Raedwald, and put to the sword Raegenhere, the king’s son, with the division he commanded, his own precursors to the shades below. Meanwhile, Raedwald, enraged but not appalled by this severe loss, stood invincibly firm with his two remaining columns.

The Northumbrians made vain attempts to penetrate them, and Aethelfrith, charging among the enemy’s squadrons, became separated from his own troops and was struck down on a heap of bodies he himself had slain. The death of their king was the signal for universal flight.

The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Angolorum, Book II, ch. 30).

Some historians have been sceptical about the authenticity of this account, stating that Henry was simply drawing on his own imagination to reconstruct the manoeuvres by which the battle was lost and won… and such things should not be quoted as history. This may be a largely fictional account, but the possibility that Henry was drawing on an Old English ‘saga’ of the battle, using the phrase unde dicitur (‘as it is written’) means that it cannot be simply discarded as such. The clash of such warriors and their armies, as well as the deaths of Raegenhere and Aethelfrith, are the kinds of stirring events that could have been woven into an Old English epic poem. As referred to in my previous article in connection with the battle of Chester of 1615/16, the Welsh Triads of the Island of Britain (Trioedd Ynys Prydein), refer indirectly to the “Three Chieftains of Deira and Bernicia” who had performed “three Fortunate Slayings”, one of which was of Aethefrith by “Sgafnell, the son of Dissynyndawd”. This suggests that British warriors fought with Raedwald and Edwin against the Northumbrians at the River Idle, perhaps forming the third column, as referred to in Henry of Huntingdon’s account, of surviving troops from the battle of Chester, seeking vengeance against Aethelfrith.

Despite the absence of detail from the few available sources, the battle was undoubtedly more significant than Bede’s brief mention implies. Above all, it was a victory for King Raedwald which demonstrated his military power and leadership. The loss of his son must have been a heavy personal price to pay, but not only was his overlordship of the south assured, but it also seems likely that he was now overlord of the north as well. His victory at the River Idle would have meant that Raedwald would have gained overall power over the lands in the north and west where Aethelfrith had been the overlord, especially when his sons became exiles as soon as Edwin succeeded to the kingdom of Northumbria. Raedwald would have become an overlord of all the ‘English’ kingdoms, north and south, though Bede attributes this achievement to Edwin, though he is probably referring to the period after Raedwald’s death, as at this point the East Anglian king was the only English king to be baptised. The Battle of the Idle may be regarded as the first successful ‘trial by combat’ for a Christian Anglo-Saxon king. Raedwald’s triumph there might well have been seen to demonstrate the power of the new God to deliver the blessings of victory, and it may well have been a significant factor in the decision of Eadbald of Kent to accept baptism, enabling the re-establishment of Roman Christianity at Canterbury. Bede tells us nothing about the last years of Raedwald’s life, but there is no reason to doubt that he retained his prestige and power, becoming the most powerful Anglo-Saxon ruler south of the Humber. Neither does Bede record the death of Raedwald, but it may be inferred from the dating of circumstantial events that he had passed away by about 624-25. It was shortly after the Battle of the River Idle, in 617, that Raedwald succeeded as Bretwalda and he, in turn, was followed by Edwin of Northumbria, whom Raedwald had restored to his throne. Bede recorded that:

The glorious reign of Edwin over English and British alike lasted seventeen years, during the last six of which … he laboured for Christ.

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731).

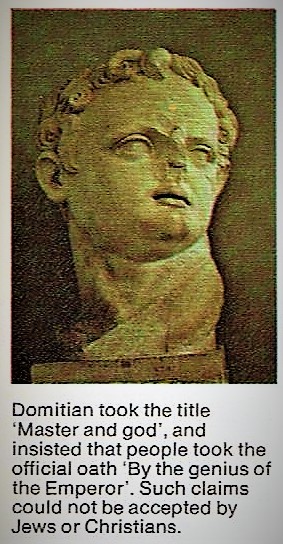

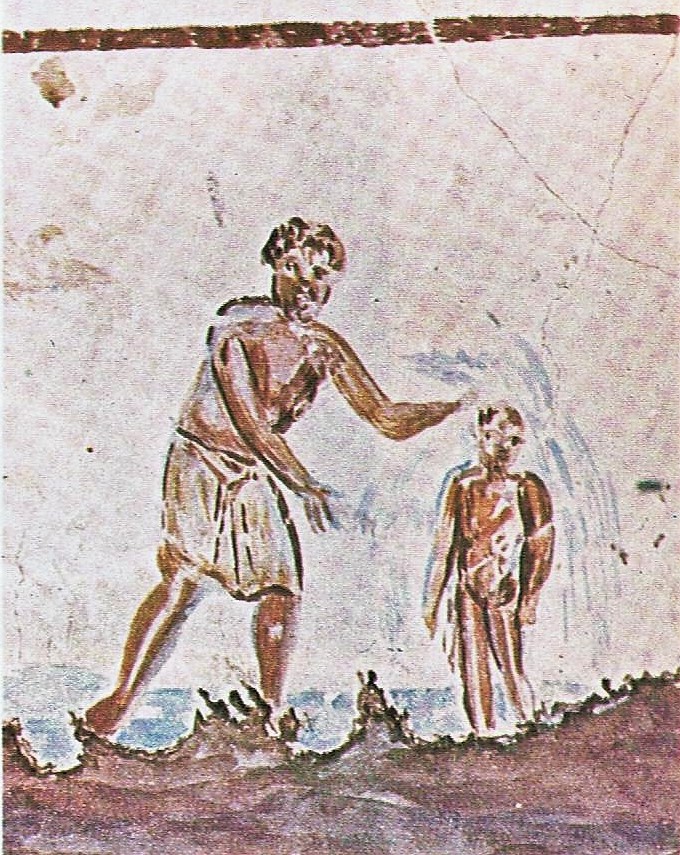

The impact of Christianity on Anglo-Saxon pagan society is well shown in the conversion by St Paulinus of the ‘great’ King Edwin of Northumbria (at least that is how Bede writes of him). Edwin had married the daughter of Aethelbert of Kent. She had been allowed to bring Paulinus with her as her confessor. Much pressure was brought to bear on Edwin who, as Bede records, was a wise and prudent man who often sat alone in silence for long periods, wondering which religion he should follow. After much reflection, he told Paulinus that he wished to consult his court. His ‘High Priest’, Coifi, recommended acceptance of Christianity and another courtier said that if Christianity could tell them more about what goes before this life and what follows, it was better than the old religion, then they should follow it. He compared the brief life of man on earth to the flight of a sparrow through the king’s mead-hall in the winter. After Coifi had asked to hear more from Paulinus, he himself volunteered to be the first to desecrate the temples of the religion of which he was the chief representative. Then carrying a spear and riding a stallion (both acts forbidden to a priest of his original religion) he went to the temple at Goodmanham, to the east of York, and hurled his spear at the temple, ordering it to be burnt. The great Minster of York rises on the site of the holy well where Paulinus baptised Edwin. Thus the Northumbrians adopted Christianity.

Christianity & the Heptarchy:

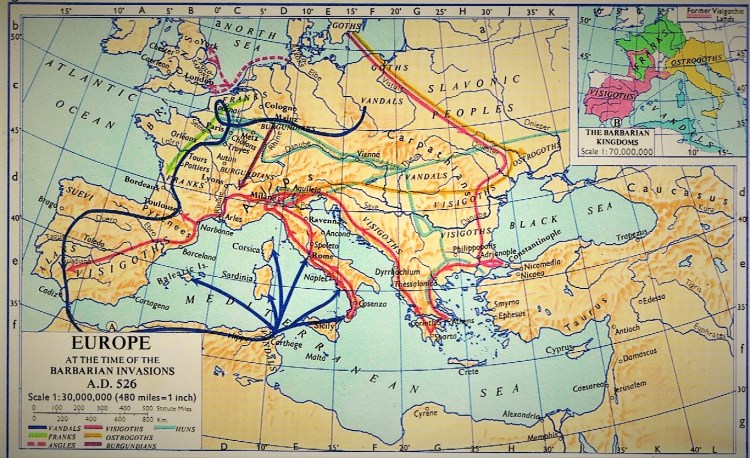

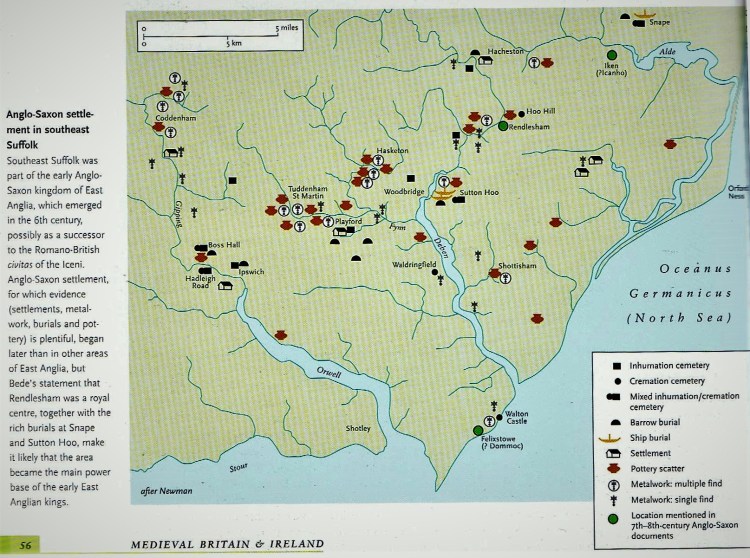

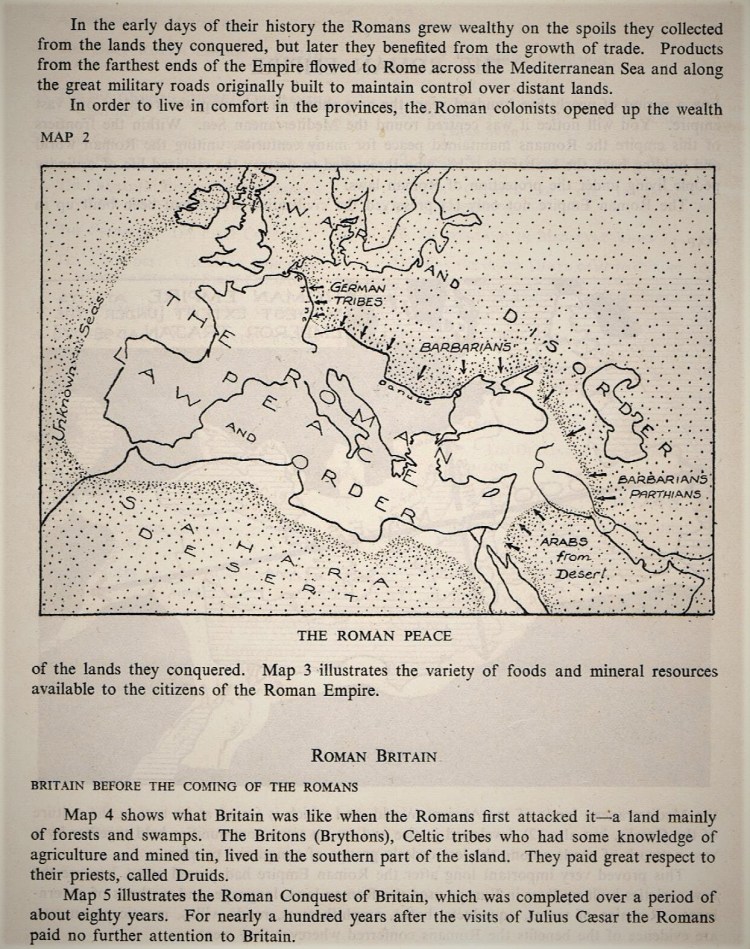

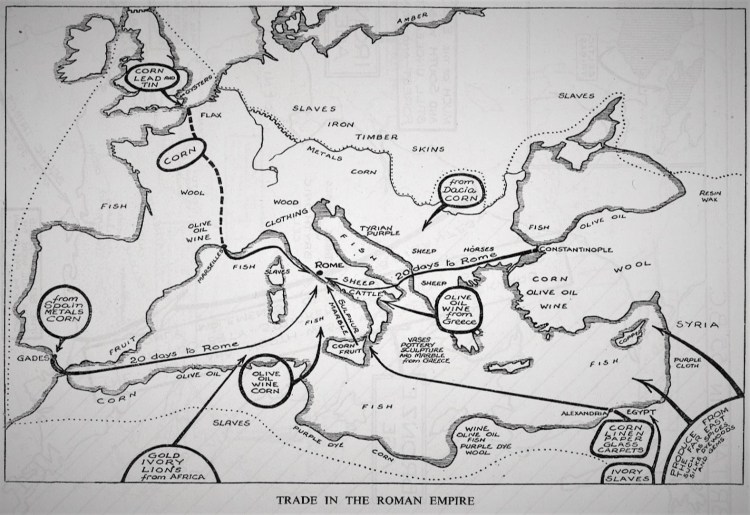

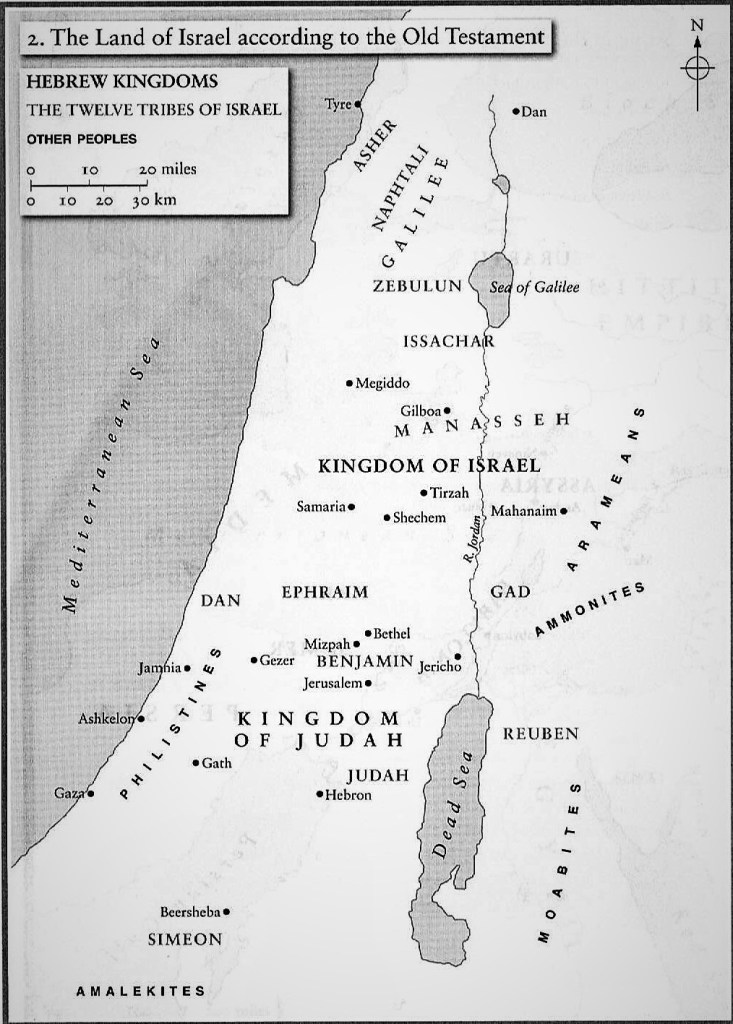

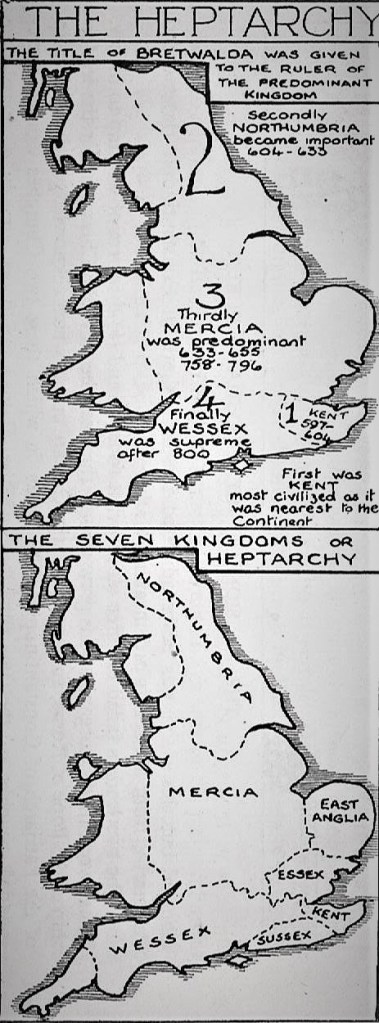

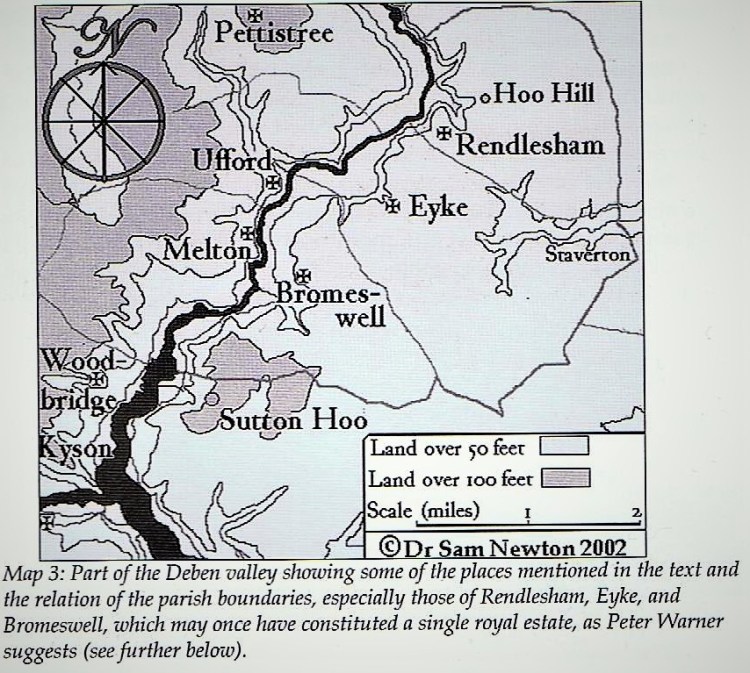

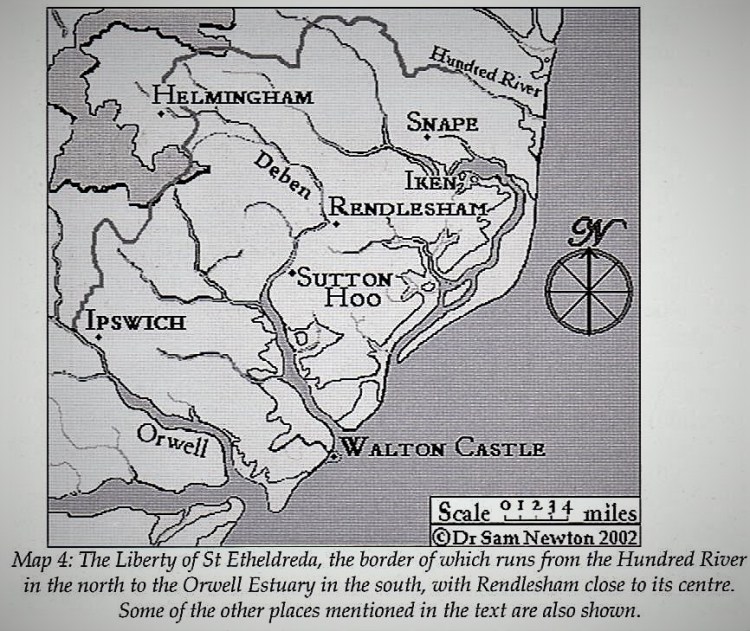

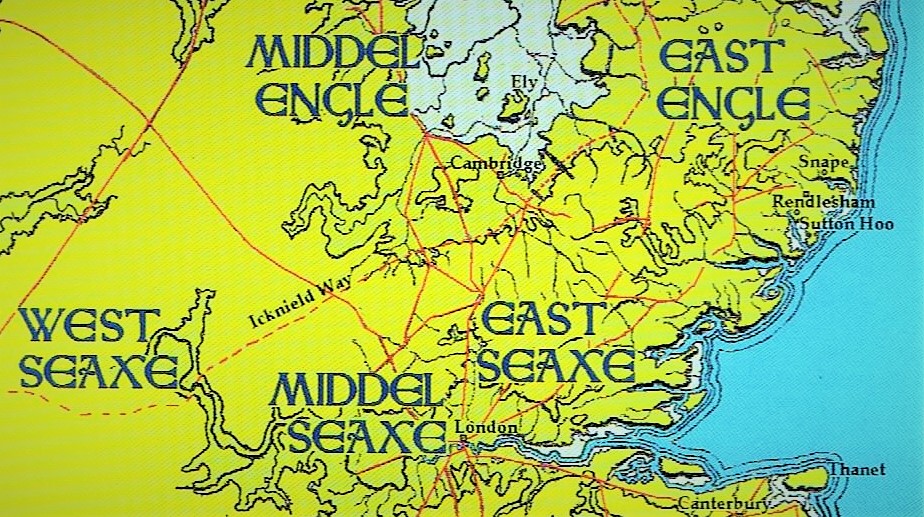

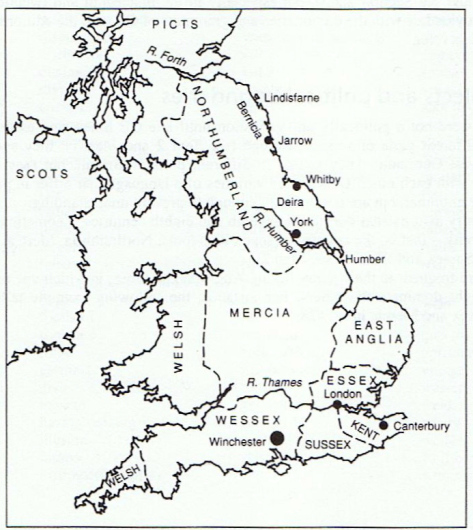

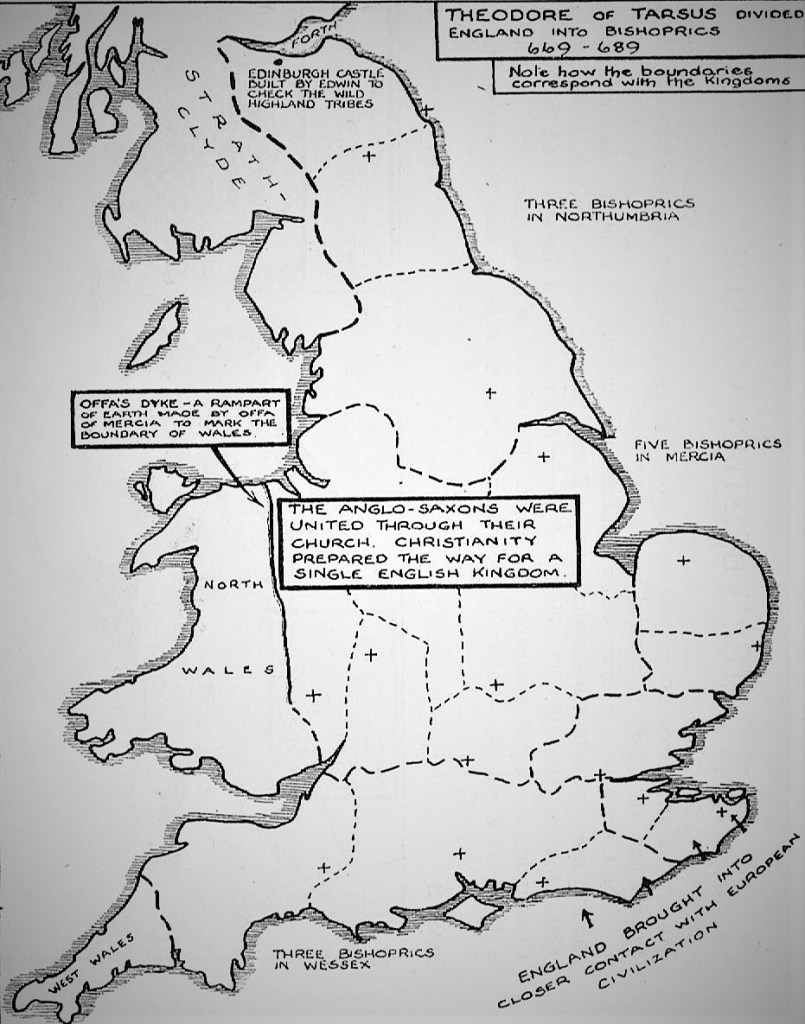

The maps on the right show how the Angles, Saxons and Jutes formed themselves into seven kingdoms, but they were sketched and published just after the second world war before the finds at Sutton Hoo were well known outside archaeological circles. Moreover, the frontiers shown are those of the early ninth century, as the inclusion of Offa’s Dyke reveals. The smaller kingdoms, such as East Anglia, were truly independent only for short periods, but one of these was the period of the reign of Raedwald, who became Bretwalda in 617, as confirmed by the twelfth-century Anglo-Norman poet Geffrei Gaimar, probably drawing on a lost version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Bede’s later chapter on the coming of Christianity to the East Anglian kingdom tells us of how circa 626-27, King Edwin of the Northern Angles (ruled c. 617-633) persuaded King Eorpwald of the Eastern Angles, Raedwald’s second son and eventual successor, to accept baptism. This would have meant that Raedwald was Bretwalda until, nearing death in 624-5, he handed the title to his friend and ally, Edwin. Recently, teams of archaeologists have been exploring a possible site at Rendlesham in Suffolk, located on the east bank of the River Deben some four miles upstream from Sutton Hoo.

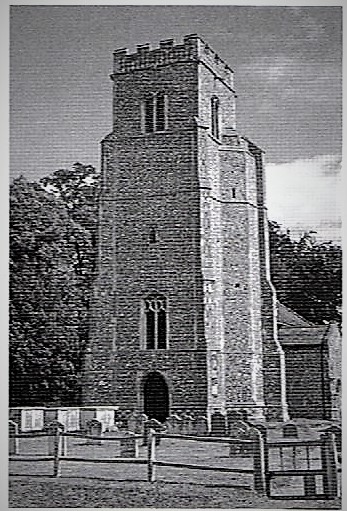

Rendlesham is named by Bede as ‘the house of Rendil’ and as a royal site in the reign of Raedwald’s nephew, Aethelwald, who ruled circa 655-664. There is a reference to this in Bede’s account of the return of Christianity to the kingdom of the East Saxons at around the same time. It refers to the baptism of Swithhelm, king of the East Saxons, by the Celtic monk Cedd at Rendlesham. Bede’s casual reference to Rendlesham as a royal hall is of great significance because it implies a complex of buildings including a great hall beside the royal church where Swithhelm was baptised. Archaeological and landscape evidence suggests that at least part of the royal site at Rendlesham was located in the vicinity of St Gregory’s church.

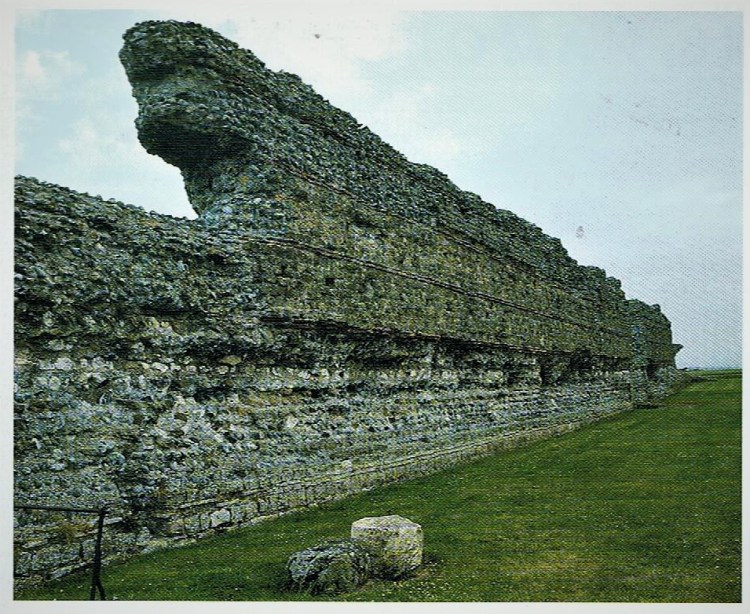

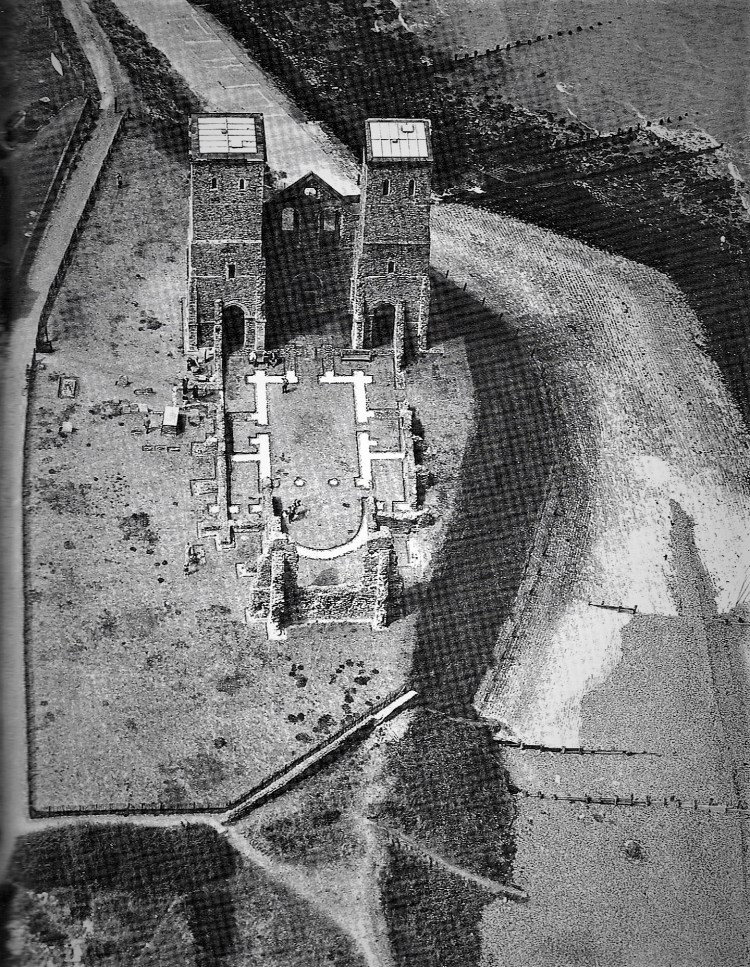

Raedwald’s successor, Eopwald, embraced Christianity only to be murdered soon after his accession by a pagan usurper, Ricbert, perhaps a stepson of Raedwald. Within three years the rightful heir, Sigebert, returned from exile among the Franks and regained the throne. The new king was an impressive and much-loved figure, possessing all the warrior skills of the Wuffings allied to a devotion to the Christian learning he had encountered in exile. On his return to East Anglia, he set Christian missionaries to work converting and educating his people. These were Felix, a sophisticated Burgundian brought up in the Frankish schools and Fursey, an Irish monk, aflame with Celtic zeal and mysticism. Felix was appointed Bishop of East Anglia by Archbishop Honorius in about 631. He established his base at Dummoc, an unidentified spot on the coast, possibly at Dunwich or Walton Castle (see the map below). There he built a cathedral and a school, and then set out as a Christian strategist to win the scattered souls of his large diocese over the following seventeen years. Bede calls him a pious cultivator of the spiritual field. As a young man, Fursey received a vision of heaven and hell and turned his back on home and comfort to become a wandering preacher. When he reached East Anglia, news of his holy life and heart-piercing eloquence soon came to Sigebert’s ears. He entreated the saint to stay and gave him the useless site of Burgh Castle as a base for his missionary work. There, using the stone from the ruined Roman fort and timber from the edge of the forest, Fursey built his monastery and his community imposed on themselves the full rigours of an ascetic discipline. For ten years, Fursey preached his way around East Anglia, winning hundreds with his exaltation of the love of God and his vivid descriptions of eternal bliss and damnation. He then returned to the kingdom of the Franks, where he died.

Fursey had a momentous influence on King Sigebert. Impressed by the teaching of the monks, the King resigned his pomp and power to become one himself. But these were difficult times for kings to give up office, with the conflict between the kingdoms of the Heptarchy evolving into a tri-cornered conflict between the great kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria in which the more minor kingdoms were merely pawns in a game which they nevertheless had to play. At the time when Sigebert vacated his throne, Mercia, under its pagan king Penda, was in the ascendant and in the 630s his forces were pressing hard on the East Anglian border. The traces of the earthworks hurriedly thrown up by the combined South Folk and North Folk can still be seen across today’s landscape, four lines of defence traversing the limestone ridge and obviously devised to fill the gaps between the natural obstacles of fen, forest and high ground through which the invaders had to come. The ‘Devil’s Dyke’, the most important of these, has a rampart which still stands over six feet tall, with a climb from the bottom of the ditch of ten metres. The first major crisis came in 636. The Mercians invaded in force and the East Anglians mustered to meet the challenge. But they had no confidence in their new king, Ecgric, and a group of them went over to Beodricsworth (Bury St Edmunds) Abbey to plead with Sigebert to lead them against the Mercians. But Sigebert refused to forsake his holy orders and eventually, his frenzied countrymen forced him to leave the cloister in his habit, convinced that even in this, the sight of him on the battlefield would inspire the East Anglians. They marched forwards and met the Mercians at some unknown point on the Icknield Way. Sigebert refused to forsake his vows, neither taking up a weapon nor armour. The battle was soon over, with both Sigebert and Ecgric among the dead, and their people routed.

Penda placed Anna on the throne, Raedwald’s nephew, to rule East Anglia as a vassal kingdom of Mercia. Like his predecessor, he was more renowned for his piety than his skills as a warrior, and he had four daughters who were even more devoted to their faith, founding monasteries and nunneries. It was at some time between the end of Raedwald’s reign and Sigebert’s reign that the Sutton Hoo burial took place, so the identity of the ‘missing king’ is still an open question, but he was certainly one who ruled as a Christian – at least nominally – over a still predominantly pagan kingdom. Anna spent much of his time at his manor at Exning and may have made it his capital. The site near Newmarket had many advantages: it lay near the centre of the Devil’s Dyke defence line and was a good rallying point for military contingents of both the North Folk and the South Folk. It was also not far from the important monastic centre established by Felix at Soham.

This whole area, centred on Rendlesham, Sutton Hoo and the Deben valley represent the old heartland of the Wuffing kingdom. Peter Warner describes this territory as both the cradle and resting-place of the early East Anglian kingdom. It was eventually bestowed as a Liberty by King Edgar (959-975), thus confirming the re-establishment of St Aetheldreda’s Abbey of Ely. In the year that Raedwald’s nephew, King Anna died in the Mercian massacre under the powerful pagan King Penda (654), Botolph built a monastery on the Alde estuary at Iken. Etheldreda or Aethelthryth (to give her name its proper spelling) was a Wuffing princess, being the saintly daughter of King Anna, and she fell under the spell of holy Felix and his monks. Her only ambition was to lead a life of contemplation and prayer, but as a princess, she was twice married off, apparently surviving both these ‘unions’ with her virginity intact. After twelve years of marriage to her second husband, Prince Egfrid of Northumbria, he gave her freedom to go and live as a nun, and she founded an Abbey on the Isle of Ely, doubling as a monastery for monks as well as nuns. As founding Abbess of Ely, she was enshrined as a saint after her death on 23 June 679. Following Edgar’s gift of the Five Hundreds of Wicklow, as the area came to be known, it remained a coherent territory until the late nineteenth century. All of this evidence adds weight to the argument that Raedwald’s temple of the two altars was within this territory and may have stood close to the royal hall site of the Wuffing kings at Rendlesham.

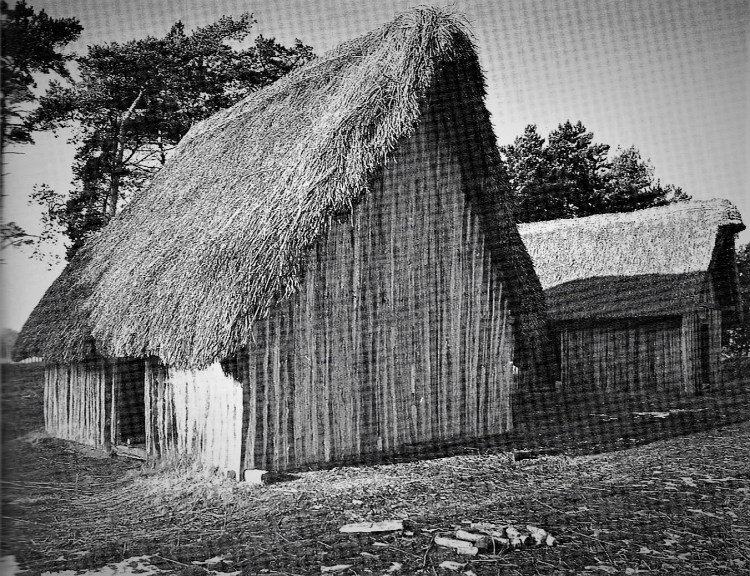

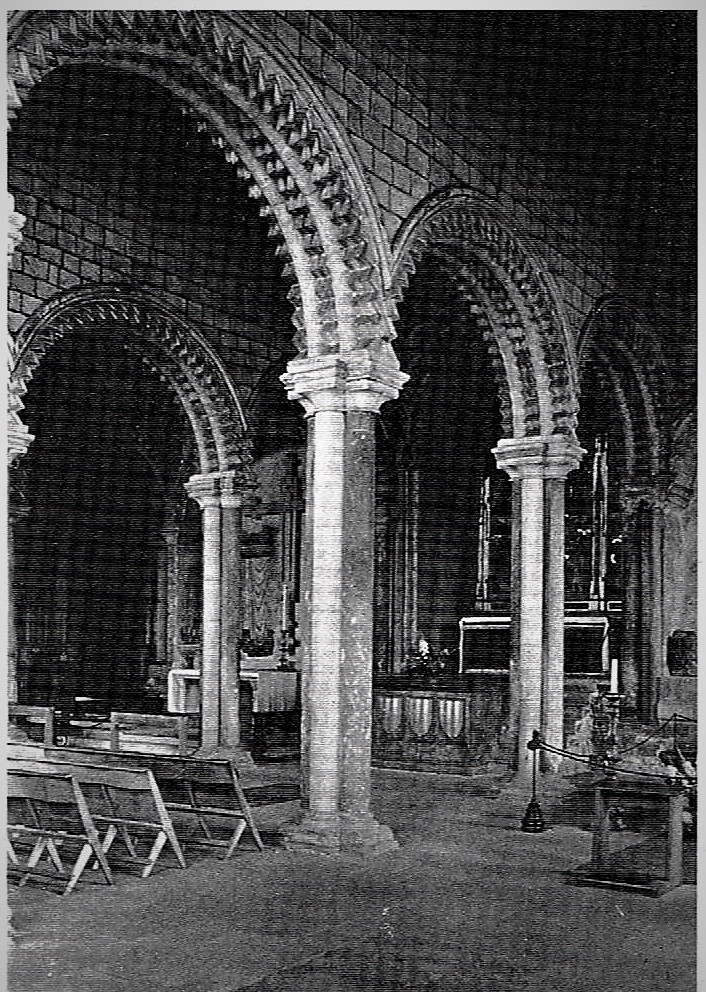

The last Wuffing king died almost a hundred years after Anna and that century produced few events which the monastic scribes thought worthy of recording. It would appear, as Wilson states, that the last generations of the Wuffing dynasty produced no men of stature to compare with the founders of the house. On the other hand, the people of East Anglia seem to have been left in peace. Though owing allegiance to the kings of Mercia, they were far enough away from the main arena of political and military conflict to be left much to their own devices. We would be wrong to think of these early Saxon Christians as worshipping in impressive stone churches and minsters bearing any similarity to those built from the tenth and eleventh centuries. The first Suffolk churches were for the most part very simple affairs of wood and thatch, remaining so even into the Norman period. Stone was not a natural building material locally, and only where earlier edifices existed in the form of disused fortifications, like the Roman sea-fort at Burgh Castle, or pagan shrines, was the more permanent material used. It was often the simple Saxon peasantry who raised these first churches, more for reasons of personal comfort than for devotion. Originally, services were held in the open and the only permanent feature was the altar, often converted from an old pagan shrine. This may well also have been the nature of Raedwald’s ‘temple’ of two altars at Rendlesham. When regular attendance was required by parish priests appointed by bishops and commanded by the kings and earls or thegns, they decided to build themselves barn-like structures before the altar to protect themselves from the elements. Thus the first ‘naves’ were built, probably using disused longboats (the word ‘navy’ has the same origin as ‘nave’), and thus began the tradition of the nave of the church being the responsibility of the parishioners while the priests were responsible for the maintenance of the sanctuary. For these transitioning Anglians, the use of ships in religious matters may not simply have been symbolic.

Northumbria, Edwin & Oswald:

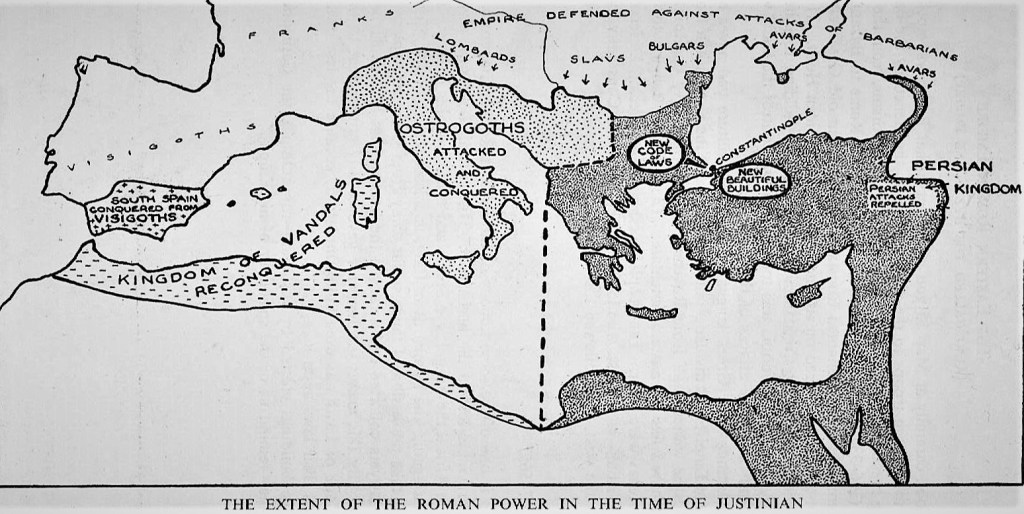

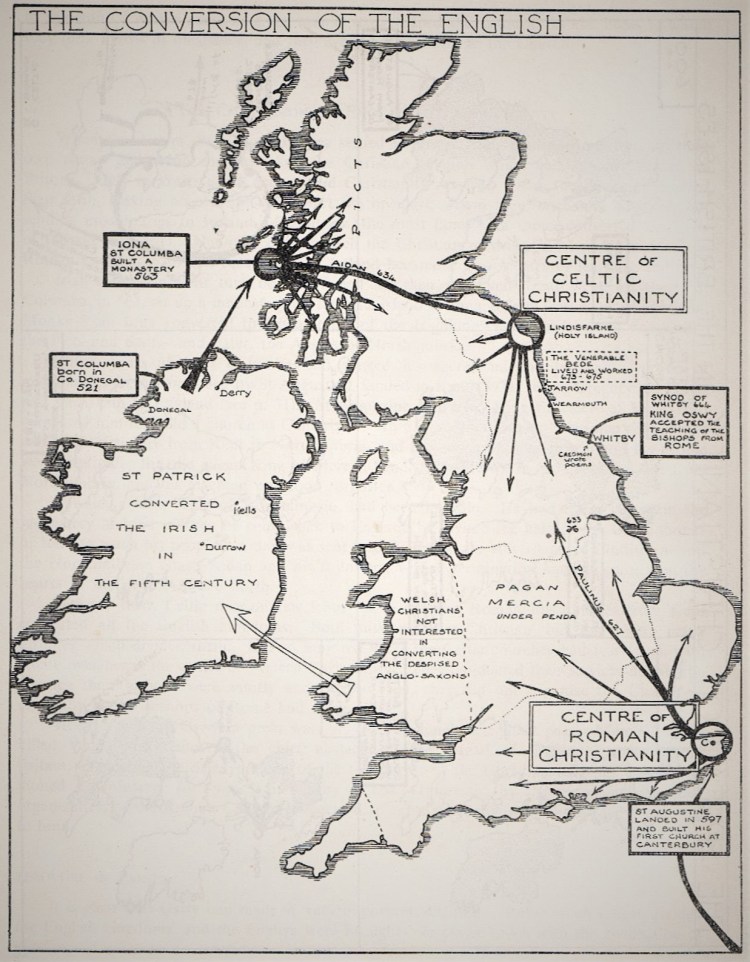

Over the course of the seventh century, Northumbria came to dominate its British neighbours through the aggressive energy of kings like Edwin, who became the first Christian king of Northumbria. His great military strength enabled him to conquer the small independent British kingdoms of Rheged and Elmet as the Anglian kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira coalesced into a single, powerful unit capable of extending its authority west of the Pennines and even down as far as Wessex, where he led his army to victory. Eventually, Northumbrian rule encompassed Whithorn in Galloway and briefly stretched as far north as the Tay. But Edwin’s invasion of Gwynedd and his conquest of Anglesey and the Isle of Man led to a counter-invasion of Northumbria. In 632 the allied forces of Penda of pagan Mercia and King Cadwallon of Gwynedd defeated the Northumbrian army on the plain called ‘Haethfelth’ (Hatfield in Yorkshire) where Edwin was slain in 633. The Britons attempted to cement their victory through the devastation of Northumbria, but although the kingdom was again split into the territories of Bernicia and Deira, Cadwallon was himself defeated in 633 at Heavenfield by Oswald of Bernicia. This victory reunited Northumbria and destroyed hopes of a British revival led by Gwynedd. Under Oswald, Northumbria rose to pre-eminence in England, but in returning northern England to Christianity after Paulinus himself was forced to return south, Oswald turned to Iona rather than Canterbury. The Iona community sent a monk who was not well received and who returned in disgust. In discussing what had gone wrong with his mission another monk, Aidan, voiced criticisms of his approach and, while he spoke, it dawned on his brothers that Aidan should be sent. Aidan formed a great friendship with Oswald and founded his monastery on the tidal island of Lindisfarne within sight of the king’s fortress of Bamburgh on its proud rock overlooking the North Sea. This long low green island, with the Farne Islands as outriders, preserves the ruins of the later medieval monastery.

Meanwhile, Oswald’s clash with the growing power of Mercia could not long be postponed. By this time, Mercia had emerged as the chief kingdom of the English Midlands, expanding westward to the Welsh marches and securing the area to the south of the Humber, under the rule of Penda. When Penda was not fighting the Northumbrians he was busy killing the kings of East Anglia on one side of his kingdom and wresting the lands of the ‘Hwicce’ from Wessex on the other (the Hwicce were once a very powerful tribe who formerly occupied a significant territory of Gloucestershire and Worcestershire). In 641 Penda defeated and killed Oswald at Maserfelth (Oswestry), assuming Oswald’s mantle as the most powerful ruler among the English kingdoms. Penda rampaged on elsewhere, and in 645 he was reported to have put Cenwedh of Wessex to flight because Cenwedh had deserted Penda’s sister.

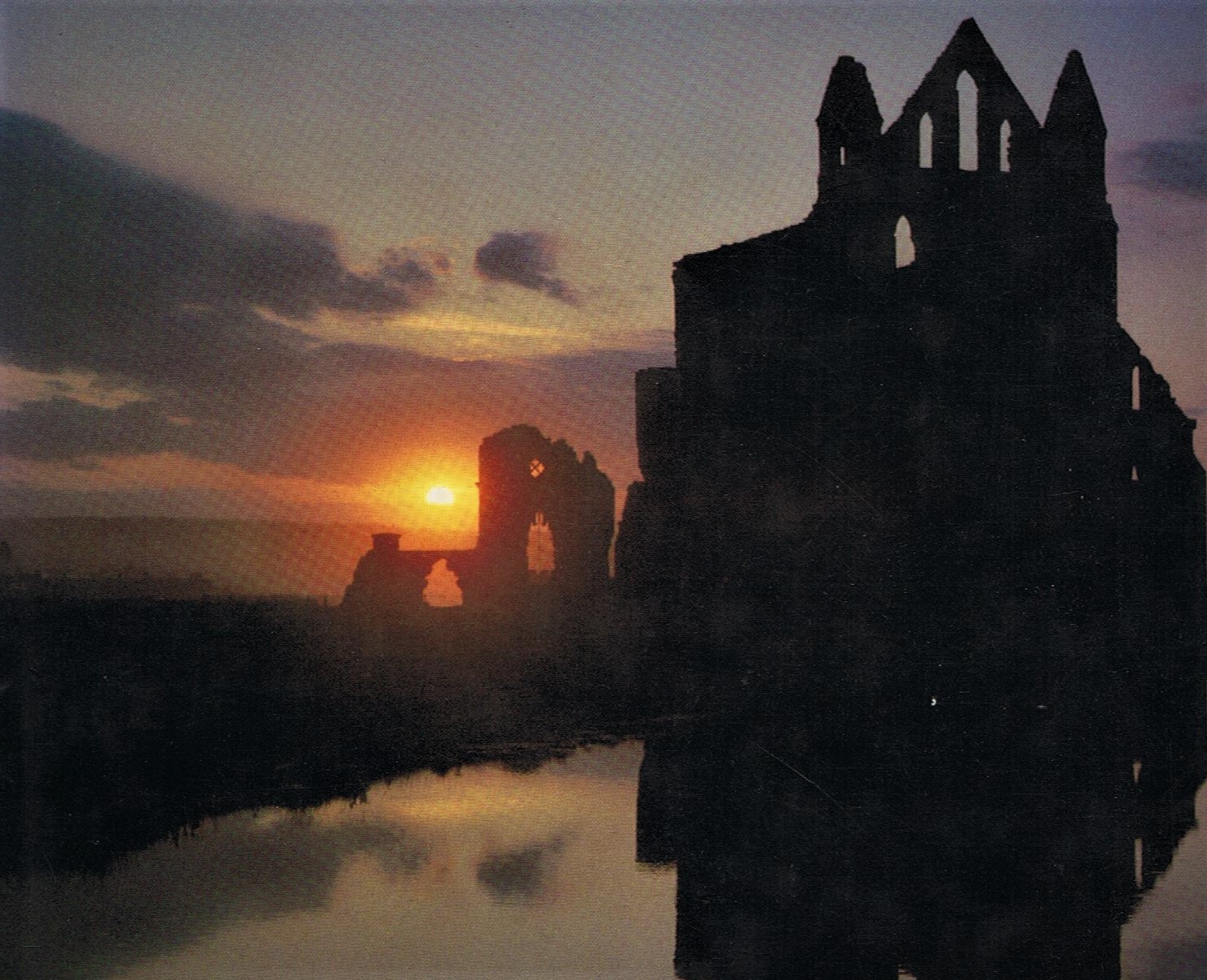

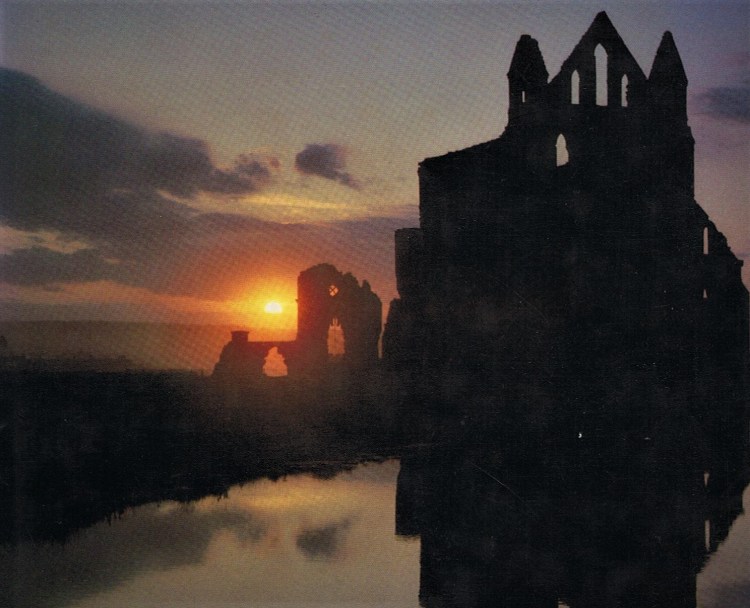

Oswiu, Cuthbert & the Synod of Whitby:

Northumbria, meanwhile, had again reverted to separate kingdoms, Oswin, ruling Deira and Oswiu, Bernicia. At the same time, although unable to reconquer the whole of Northumbria, the Mercian king was still determined to destroy the residual power of Bernicia. One of Lindisfarne’s first bishops was St Cuthbert who as a shepherd boy in the Lammermuir Hills in 651 had a vision of angels bearing St Aidan’s soul to heaven. Inspired by that vision, he joined the monastic community of Melrose Abbey under its founder Eata, who then took him to be the ‘guest master’ at Ripon and then onwards to Lindisfarne where he made Cuthbert prior. But Cuthbert longed for solitude and was given permission to retire to the Great Farne Island where he lived in a sunken turf oratory. He was forced to leave his retreat when he was consecrated bishop and had to fulfil his new duties.

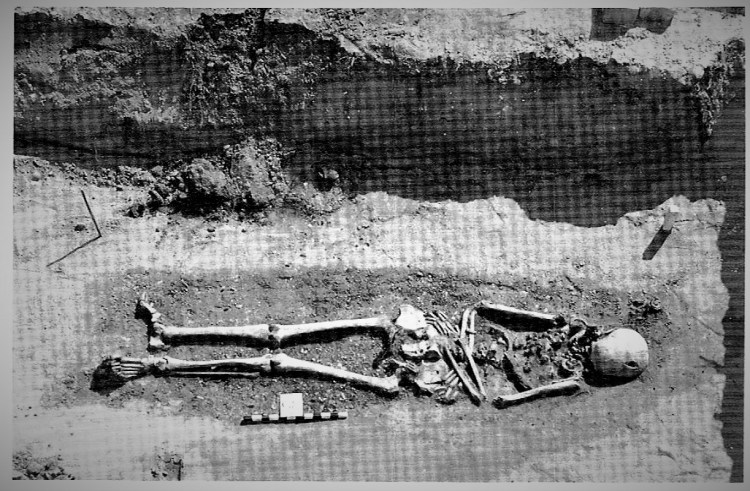

The strategic nature of Exning, the new royal capital of East Anglia, was put to the test in 654 when King Anna fell foul of his overlord, Penda. His Mercian hordes once more marched along the Icknield Way and Anna prepared to defend the Devil’s Dyke. Archaeological activity has uncovered a large burial ground of the period and many of the skeletons bear the marks of violence. How long the defenders withstood the siege or whether treachery played a part in Anna’s downfall we shall never know, but we know that the Dyke was breached and that the Mercians pursued their fleeing opponents back to the capital and beyond. For more than fifty miles the chase went on until Anna and his remnant were brought to battle near Blythborough. There, according to Henry of Huntingdon, the chronicler, Penda fell upon the East Anglians,

… like a wolf on timorous sheep, so that Anna and his host were devoured by his sword in a moment, and scarcely a man of them survived.

After this disaster, little is recorded about East Anglia in the chronicles. The people of East Anglia seem to have been, for the most part, left in peace to trade with the continent. Penda next mobilised a formidable coalition, including the new King Aethelhere of the East Angles, and the British Prince Cadafael of Gwynedd. Faced by this massive array of military strength, Oswiu sued for peace, even offering a lavish bribe of treasure which Penda refused. Although outnumbered and on the verge of defeat, Oswiu vanquished the Mercian army at the River Winwaed (Yorkshire) in 655, killing Penda in battle, together with thirty princes, including Aethehere, thereby removing most of Penda’s ‘loyal’ allies. Though owing allegiance to the kings of Mercia, the East Anglians were obviously considered far enough away from the main centres of political and military conflict to be left to their own devices.

In one battle, at Winwaedfeld, Oswiu had thus removed the chief obstacle to the spread of Christianity and the whole of ‘England’ was, at least officially, a Christian country. Both Mercia and Wessex acknowledged Oswiu as their overlord. It also seemed that would now become the dominant kingdom, and that the title of Bretwalda a would become theirs by hereditary right. Then in 664, realising the disadvantages of having competing forms of Christianity, Oswiu summoned a synod at Whitby. Cuthbert’s life bridged the time of the reconciliation of the Roman and the Celtic churches in Britain. St Augustine’s failure to make friends with the Celtic bishops of the West had led to the long separation of the Celtic Christians from much of Europe and their use of a different method for calculating the date of Easter had led to a further sharp division between the branches of the Church. This was settled at the Synod of Whitby in 664 when the argumentative St Wilfred used his forensic talents to defeat the Celtic opposition in the debate, after which monks and priests like Cuthbert, brought up in the Celtic tradition, accepted the Roman ways. Impressed by the power and superior organisation of the Roman Church, Oswiu decided to expel the Celtic missionaries, who returned to Iona in the Western Hebrides. When Cuthbert felt the approach of death, he returned to the beloved solitude of his island, where he died in 687.

Ecgfrith, the Picts & the Celts:

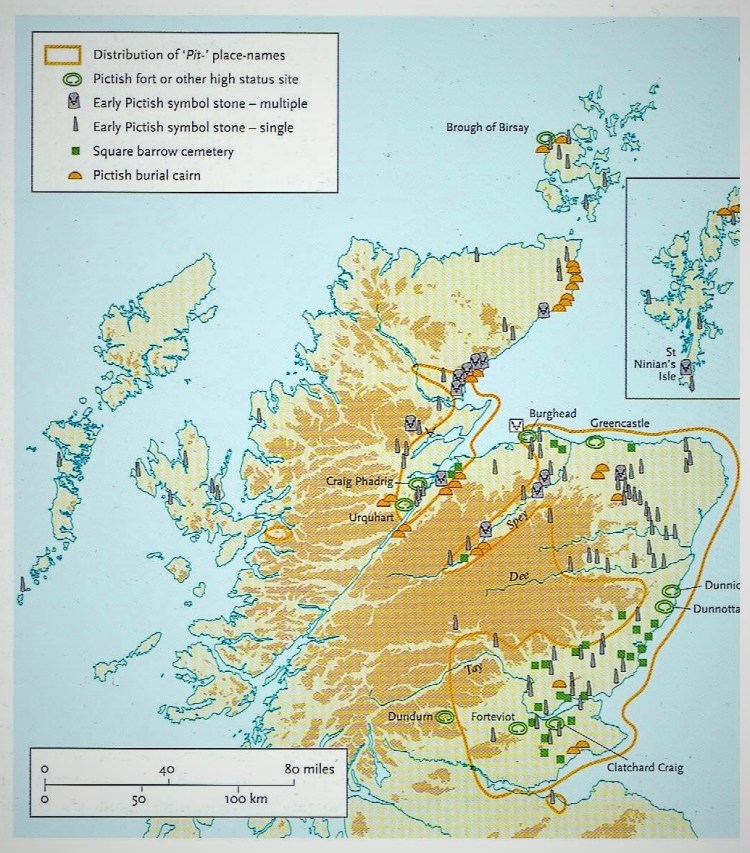

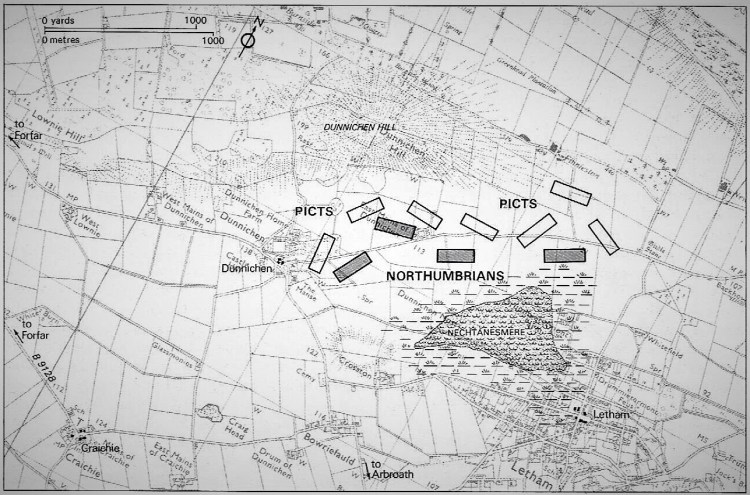

The reunification of the Church prepared the way for the Anglo-Saxons to be united under one king. Before Oswiu died in 670 he had driven the Picts back to the Tay, extracted tribute from the Cumbrians and the Welsh, and established a strong though decentralised grip on his Saxon sub-kingdoms. He was an early exponent of the ‘scorched earth’ policy in keeping the lands between Northumbria and ‘Scotland’ so barren that not even a Pictish army could find sustenance on them. It was only with Oswiu’s death in 670 that Mercian power began to reassert itself under the leadership of Penda’s son Wulfhere. In 674 Wulfhere invaded Northumbria and with an army drawn from all of the southern kingdoms, but he was repulsed by Oswiu’s son Ecgfrith, who proved himself equally able. He captured Cumberland and Westmorland from the Britons and even invaded Ireland. But in 678 Ecgfrith was defeated in turn by Wulfhere’s brother Aethelred at the battle of Trent, in what proved to be the last clash between the armies of Mercia and Northumbria for a generation. It was also the final attempt by Northumbria to gain control of the southern kingdoms and henceforth the Northumbrian kingdom’s concern would rest primarily with the north. In 685 Ecgfrith led an army northwards against the Picts, despite the protests of his advisers, for his expedition was considered by them as unnecessary aggression. The Picts, led by their king Brude Mac Beli, retreated before Ecgfrith’s advance, drawing him into the difficult territory of the Sidlaw Hills. They turned upon the pursuers and defeated them in battle near a loch called Nechtanesmere, by Dunnichen Hill, south-east of Forfar, shown on the map below. Dark Age battle sites, as noted above, are notoriously difficult to place in specific locations. The Battle known as that of ‘Dunnichen Moss’ or Nechtanesmere was fought on the banks of a loch, or ‘mere’ which has since disappeared. Its location has been pinpointed to an area between Dunnichen and Letham, south of the modern road between Forfar and Arbroath.

The battle was more of a running fight or mélée with the Northumbrians, disorganised by the speed of their pursuit, finally trapped against the shore of the loch between Dunnichen and Dunnichen Hill and its presence would further have restricted the Northumbrian deployment and presumably have provided a source of reinforcement for the Picts. Ecgfrith’s bodyguard made a last stand around their lord, but both he and most of his army was slain. With Ecgfrith’s defeat, Northumbria’s hegemony in northern Britain was replaced by an independent kingdom of the Picts. Ecgfrith’s successors were weak, and this was quickly recognised both within and outside Northumbria. The Picts were soon back to harrying the north, while to the south, the immediate future lay with Mercia, whose rise foreshadowed the decline and eventual collapse of Northumbria. They made East Anglia, Kent and Essex dependent states, and took the territory to the north of the Thames from Wessex, while also annexing Northumbrian lands south of the Trent.

Anglo-Saxon Christianity & the Celtic Church:

The warlike ethos of the Anglo-Saxon tribes had often centred on the semi-divine nature of their kings who claimed descent from Woden. The strong individualism and marked personalities of the Christian saints stood out in severe contrast to the tribalism of the peoples they converted. These tribes were guided by myths from the ancient past: the very concept of law amongst the Anglo-Saxons was that of ‘the doom’, something that could only be interpreted, not altered. The role of the individual mattered only in the context of the tribe. The missionaries who came from other societies broke through the closed and parochial nature of the tribe, bringing the hope of a way of life that could develop and change the individual personality, offering the idea of conscience as the light of inner emotional truth, and at the same time revealing the attractions of an international civilization in learning and the arts of an order far removed from from the blood-thirsty legends of the Teutonic past. The missionaries exhibited time and time again the one quality the Anglo-Saxons prized above all others: courage.

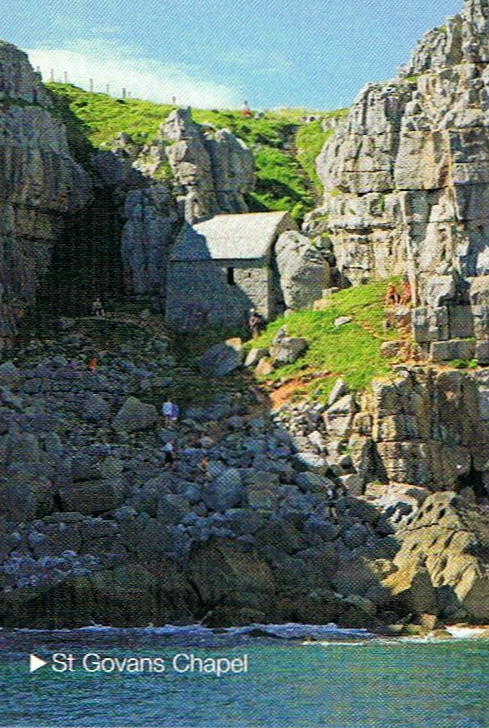

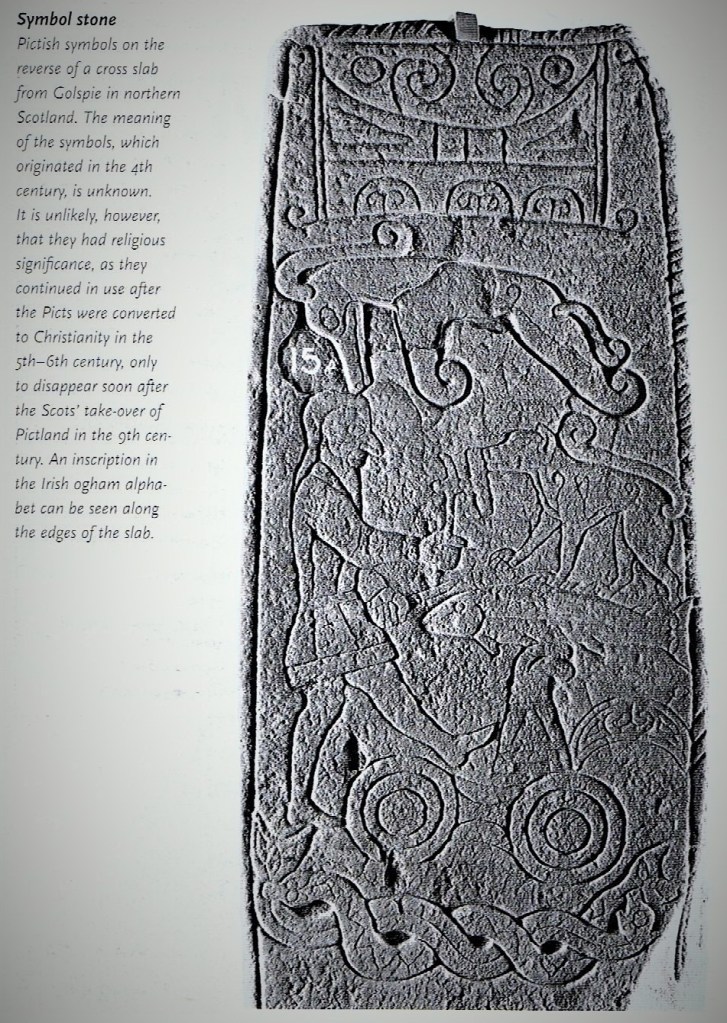

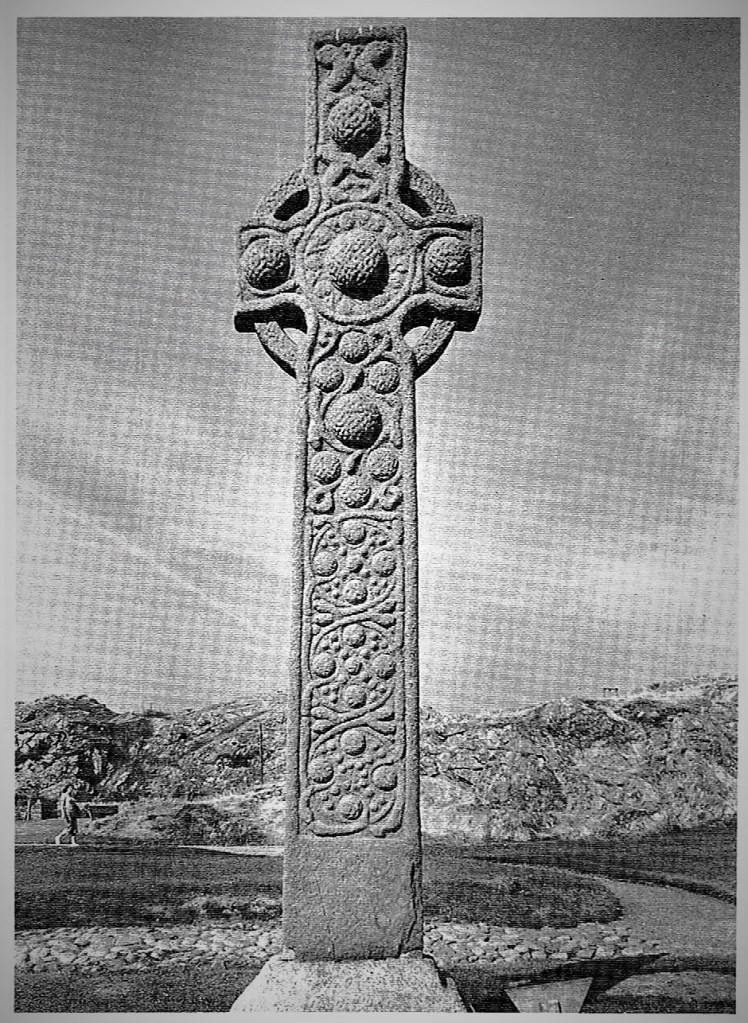

And just as St Patrick had drawn on the Irish veneration of the number three, so the missionaries in England found in telling the story of the crucifixion minds already prepared by the legend of Woden sacrificing himself upon the tree, a myth perhaps underlying the great Anglo-Saxon poem, The Dream of the Rood, quotations from which were carved on the Ruthwell Cross. By about the time the Cross was carved, around 700, the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity was largely complete and the Church was becoming increasingly political, not least because of its vast land-holdings. Nevertheless, religious authority was not effectively centralised in this period, despite the claims of Canterbury and York to authority beyond their local political boundaries. In terms of church art and architecture, the Anglo-Saxons invested far greater artistic energy into their buildings than in monumental sculpture, except in Northumbria. By contrast, an interest in monumentalism in religious art continued unbroken in the Celtic regions in the post-Roman era, though styles evolved over time. Extremely fine, though distinct, sculptural traditions developed in Pictland, Argyll, Ireland and Wales. In some cases, the presence of a collection of sculptures is all that now remains to provide evidence of the importance of a particular church.

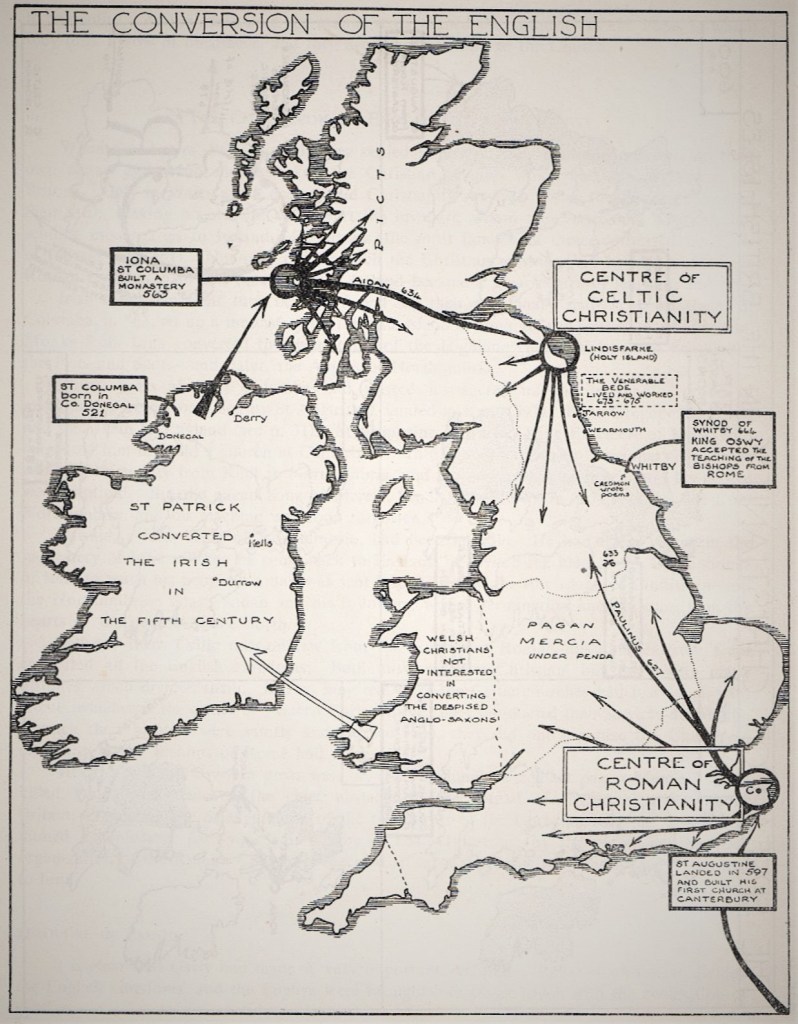

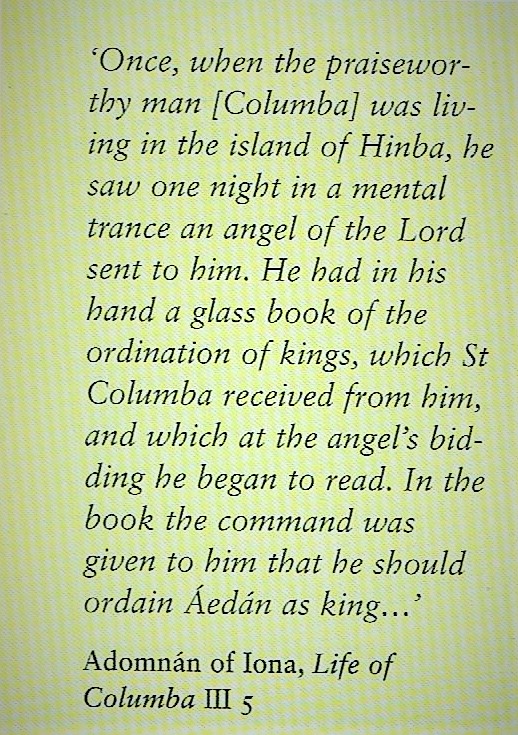

During the eighth and ninth centuries, despite its return to the ‘Roman fold’, the Celtic Church grew in influence, wealth and organisation. This development was, as we have seen, closely intertwined with secular political and dynastic developments, not least because the same royal and aristocratic families dominated both the Church and the Crown. Frequently, a particular saint became identified with a specific kingdom, which meant that the spread of saintly cults was strongly influenced by political concerns. In Ireland, the cult of Patrick (and thereby Armagh’s claims to primacy) was promoted by the Uí Néill. Northumbria’s influence is reflected in the churches dedicated to Saints Oswald and Cuthbert. Nowhere is the relationship between cult and kingdom easier to appreciate than in Dál Riata, whose ruling dynasty looked to St. Columba as their patron and protector. Founded by Columba in 563, the Abbey on Iona grew to become the greatest ecclesiastical centre in the British Isles, establishing an extensive network of associate monasteries, spreading from northern Britain to Kells and Durrow in the Irish Midlands, to Derry in the north of Ireland, and to Lindisfarne in Northumbria.

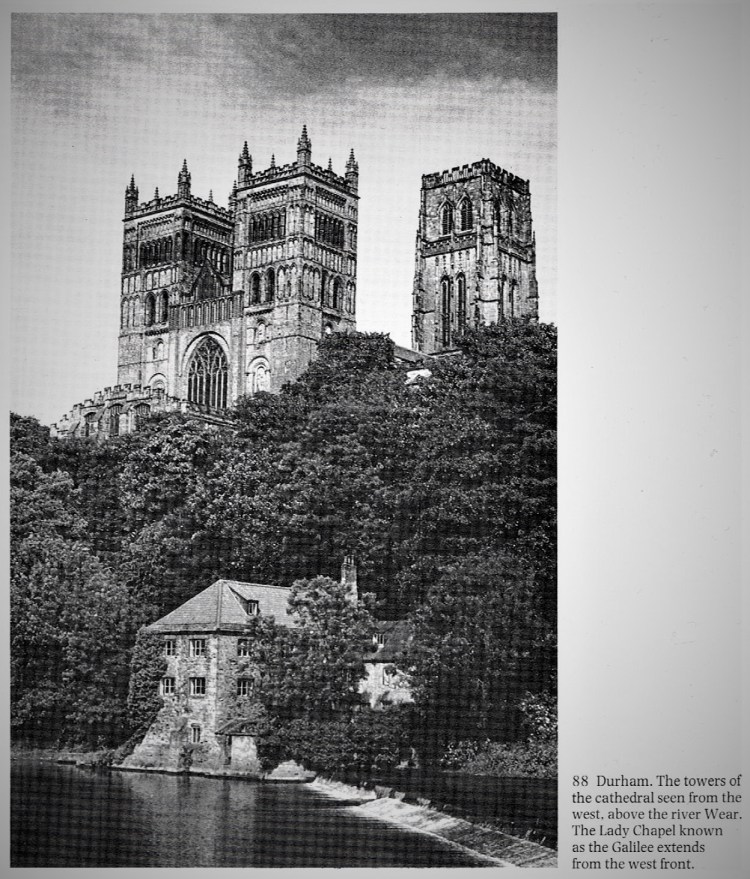

These were places of great scholarship and spiritual devotion, but they were also repositories of great wealth. From the late eighth century, Iona was repeatedly raided by Vikings, so that Columban relics were moved from Iona to Dunkeld where there was great enthusiasm for dedications to Columba and other Ionian saints. Cuthbert’s body remained at Lindisfarne until the Viking attack on the Abbey in 875 when the monks in fleeing took it with them together with the head of St. Oswald and the relics of St. Aidan. These relics were kept at Chester le Street for over a century until later Viking attacks forced the monks to move again. They went south until they found the great hill at Durham where they built a church, now superseded by the cathedral, one of the greatest architectural achievements in Europe.

In the South, Christianity had become part of the fabric of English life by the end of the eighth century. In East Anglia, preachers were sent out from Dummoe on regular tours. The monks of Burgh Castle, Soham and Boedericsworth ministered to the souls in their immediate localities and they wandered the hamlets of Suffolk to preach the Gospel and administer the sacraments. The religious houses of early date in Suffolk were modest constructions, like most of the early churches and abbeys of East Anglia, built with local materials of wood and thatch. Throughout much of what was recognisably becoming ‘England’, and with the backing of kings and thegns, Christianity passed rapidly from the age of missionary zeal to the age of the established religion. The upkeep of churches and clergy met by grants of land and by special levels approved by royal writ. ‘Plough-alms’ was a penny for every plough team and was payable fifteen days before Easter. ‘Church-scot’, the principal ecclesiastical levy fell due at Martinmas (11 November). Tithes of produce and stock were originally non-obligatory donations for the relief of the poor and needy but before many decades had passed they, too, had become sanctified by law. Perhaps most unpleasant of the ecclesiastical taxes was ‘soul-scot’, the burial fee which, we are told, was best paid at the open grave. The eighth century was not an age free from turmoil, yet such local and national conflicts as did occur took place against a background of stable, established relationships. Priest and layman, thane and churl, warrior and monk, every man knew his place in society, knew what his God and his king required of him. But some, like Bede, suggested it was becoming a decadent society, a society going soft:

As peace and prosperity prevail in these days, many of the Northumbrians, both noble and simple, together with their children, have laid aside their weapons, preferring to receive the tonsure and take monastic vows rather than study the arts of war. What the results of this will be will be seen in the next generation.

But none of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms could withstand the next groups of violent invaders. They came out of the far north this time, warriors from the fringes of the Baltic Sea: Norsemen, Vikings and Danes. For the English, although themselves relative newcomers of fewer than three hundred and fifty years, never had ‘terrors like these’ appeared in Britain. They came to raid and plunder at first and for fifty years their sporadic expeditions devastated small coastal areas. During the last decade of the eighth century and the first half of the ninth century, the Viking warlords probed the strength and weaknesses of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

In the eighth and the ninth centuries, the various polities that had emerged in post-Roman Britain became increasingly state-like in their organisation and institutions. Successful kingdoms, such as Wessex, Mercia, Northumbria, Gwynedd, Fortrui and Dál Riata, fought wars to expand their territories into large regional hegemonies. In Ireland, a less centralised political landscape evolved. There, as many as three hundred small kingdoms (Tuatha) existed. These were consolidated under the shifting control of overkings, but the rule of even the most successful of the provincial dynasties, the Uí Néill, was more contingent and fluid than its counterparts in Britain. There, the most northerly of the major kingdoms, Fortrui’s era of greatness was ushered in by the Pictish triumph over the expansionist Northumbrians at the battle of Nechtansmere in 685 (detailed above) and continued for most of the eighth century. A political and cultural high point was reached during the reign of Óengus I (died 761). The British kingdoms in southern Scotland were ruled from imposing, rock-perched hill-forts: in the west, the most powerful British kingdom was ruled from Dumbarton, dominating the mouth of the Clyde; in the east, the British kings of Gododdin surveyed their lands from the equally dramatic Edinburgh Castle rock. The Clyde-based kingdom survived into the eleventh century, while Edinburgh fell to the Northumbrians in 638. Lothian remained under Northumbrian control and became linguistically and culturally ‘anglicised’.

Competing Kingdoms of the Heptarchy – Mercia & Wessex:

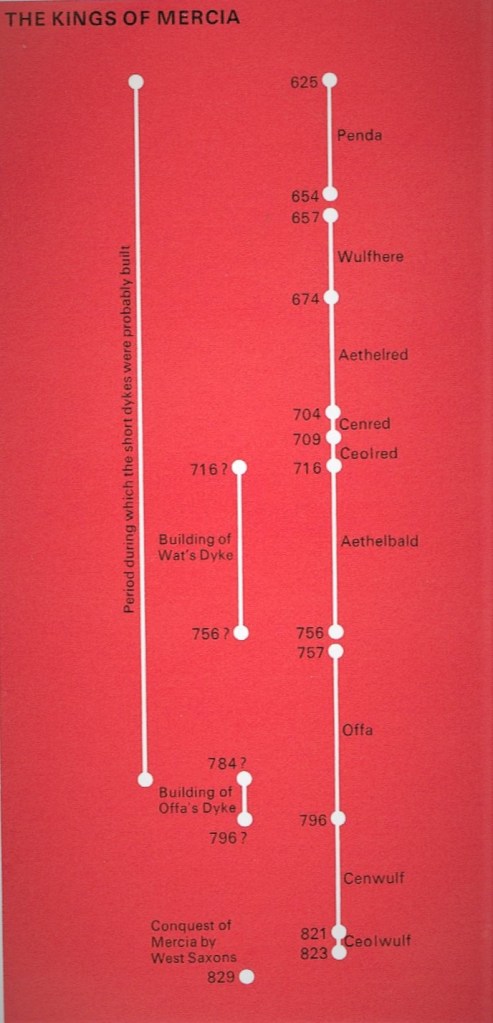

From the beginning of the seventh century to the beginning of the ninth century, the centre of power in the Heptarchy had passed from Northumbria to East Anglia (briefly) to Northumbria again, then to Mercia and finally to Wessex under Egbert, with its royal capital at Winchester. Generally good relations with the Welsh kingdoms to their west enabled the Mercians to campaign successfully against their Saxon neighbours. Offa, the son of Thingfrith, took the throne of Mercia amidst the civil war which followed the assassination of King Aethelbald in 757. The high watermark of Mercian hegemony came under Offa who ruled for thirty-nine years, from 757 to 796, achieving unprecedented power in southern Britain. Whereas Aethelbald had called himself King of the southern English, Offa was the first ruler to be styled ‘King of the English’, aspiring to rule all of the Heptarchy and to dominate the south, including Kent and Wessex.

Offa might with justice be called the first King of England, more than simply the successful leader of a regional faction, as Penda had been. All that we know of him shows the statesman, the strategist, and the man who was rightly respected in other countries. He was a contemporary of the great Charlemagne. Throughout the first half of the eighth century a protracted struggle had gone on along the ‘border’ areas, now called the ‘marches’. Offa defeated and drove back the Welsh from the line of furthest advance marked by various short dykes, building his long dyke from Chepstow in the south to a point two miles from Prestatyn in the north. This was probably begun following the the last Welsh action in 784. Offa’s Dyke is still impressive and it needs little imagination to visualise what it must have symbolised twelve hundred and fifty years ago. But it would have offered no more than token defence to an army, and was probably no more than a boundary, as it still is along some of its lengths. I have written extensively about Offa’s Dyke elsewhere on my website: chandlerozconsultants.wordpress.com.

Precisely the same applies to Wansdyke, an impressive fortification that stretches from Portishead on the shores of the Bristol Channel to the Inkpen Beacon in Berkshire, a distance of sixty miles. The bank is high enough and the ditch deep enough to offer a considerable obstacle to an advancing army, but its delaying effect would only have been temporary. It was probably built by Egbert who became King of Wessex in 800, but may have been started by his predecessor Kenulf. After Offa had died in 796, the new king of Mercia, a warlike predator, raided Kent, captured its king, cut off his hands and blinded him. The Wansdyke might not stop an army but it would stop similar lightning raids on Wessex if properly patrolled. Egbert was no mean warrior himself. In 815 he ravaged Cornwall from east to west; if he went this far from his base at Winchester he would need some sort of defensive line between his own kingdom and that of the turbulent Mercians. Beornwulf seems to have become King of Mercia by a coup d’état in 824. Like all usurpers who obtained the throne by an adroit move, he needed to give his army something to do and something to think about, as well as some rewards, lest they should look upon their new ruler with too critical an eye. There was, of course, every chance of him being toppled off the throne by an incursion from Wessex.

The ascendancy of Mercia was, however, abruptly ended following its defeat by Egbert of Wessex (died 839) at Ellendun in 825. Distracted by internal conflict, Mercia temporarily forfeited its supremacy in the south and Offa’s re-establishment of that dominance brought him into conflict with Sussex, Kent, Wessex and Wales. A crippling blow had been struck against Wessex in 779 at the battle of Bensington in Oxfordshire and it was not until Egbert, exiled by Offa, returned to take the throne of Wessex in 809 that the southern challenge to Mercia was rekindled. We know little of Egbert’s reign during the next twenty years but it is safe to assume that he was preparing for the period of intense military activity which he unleashed in 825. Egbert first turned westward advancing to Galford where his defeat of a British army brought eastern Cornwall within his control. Beornwulf, king of Mercia, had mobilised his forces but he did not take advantage of Egbert’s absence to immediately attack the heartland of Wessex. But then Beornwulf decided on a pre-emptive strike. He probably moved east as if to target in south-eastern England and then doubled back and came racing down the Berkshire Ridgeway. At Overton he twisted again, leaving the Ridgeway, and having made a survey from the observation point of Silbury Hill, he would then have come up the track by All Cannings Down. On the way he would have encountered other defensive earthworks, for this was clearly considered to be a vulnerable spot. Egbert, justifiably alarmed at this presence of a Mercian host on his northern border, had returned eastwards and the armies of Wessex and Mercia confronted each other at Ellandun, thought to be Allington, which is on the other side of the Wansdyke and therefore far removed from from the battlefield. We now believe that the battle was fought on the slopes between Allington Down and All Cannings Down.

Beornwulf was no novice at the art of war; whatever qualities he might have lacked, tactical appreciation would not be among them. He would know very well that if he made his approach to the Wansdyke too obvious, a suitable reception would be there to meet him. He would therefore have wished to have achieved one of the first principles of war, deception of the enemy, and having come down the Ridgeway rapidly, possibly with the advantage of surprise, he would have then sent a brief a small party ahead to suggest that he was marching by the quickest possible route to Salisbury. At that point Egbert would throw everything in his way, he hoped, but Beornwulf by a swift change of direction would be over the Wansdyke and on Egbert’s flank, if not actually behind him. However, although heavily outnumbered, Egbert chose to attack first and after a protracted struggle, his army gained the field and a decisive victory. Mercian losses were heavy for, in the words of the Chronicle,

Egbert had the victory and a great slaughter was made there.

So how did Egbert gain the victory in such adverse circumstances, and why did it turn into such a ‘great slaughter’? Undoubtedly, Egbert was the more experienced general. He had been on the throne for many years and had fought several successful campaigns against the Britons. He would have had spies and scouts in Mercia, and some even in circles very close to Beornwulf’s councils. As a good soldier, he would have believed in winning his battles before he fought them. Winning this battle would have involved preparing all possible approach routes so that an invading army would already have encountered significant resistance before it reached the Wansdyke. The ground at Allington must have looked highly dangerous, with forward earthworks, flanking slopes, deceptive hollows and an enclosed arena. Once among those slopes Beornwulf’s army would have little room for manoeuvre in any sense of the word. It’s possible to visualise his army as being trapped between the two sets of earthworks, desperately trying to force its way up to the Wansdyke and breakthrough, harassed by flank attacks, and unable to retreat and regroup without being disrupted. This was, it must be remembered, Saxon upon Saxon, the same weapons, the same techniques, the same dogged courage. Both armies would have learnt something from their forays against the Britons, and both probably had Cornish or Welsh in their ranks as bowmen or spearmen.

The West Saxons would have had some advantage from the fact that they were uphill to the Mercians; in all battles where hand-thrown missiles – spears, axes, darts, even arrows – were used the men on the upper slopes had a slight but vital margin of range. Missiles could be flighted to carry further from a height. Having put his men into that disadvantageous attack, Beornwulf would not be able to recover them and prevent their slaughter. Like many brilliant tactical moves, his rapid feint and change of direction deserved success. Unfortunately for him and his army, he met an even shrewder tactician. Beornwulf succeeded in escaping from the battlefield and fled eastwards to the East Angles, who killed him later in the same year. The ascendancy of Mercia was at an end and henceforth the Anglo-Saxon destiny would be controlled by Wessex. Egbert dispatched his army with his son Aethelwulf to Kent where they defeated Baldred and secured the submission not only of Kent but also of Essex, Surrey and Sussex. Four years later in 829, Egbert invaded and conquered Mercia with a great army and carried all before him as far as the Humber. The Northumbrians fought back but were themselves decisively defeated at Dore, being forced to accept Egbert as Bretwalda. He also took the title of ‘King of the Mercians’ for a year before the kingdom regained its independence and he turned his attention to conducting a successful campaign against the Welsh.

Before moving on from Ellandun, we should mention the other sites which other writers have suggested. Wroughton, immediately south of Swindon, has been claimed as a likely site, and so has Lydiard Tregoze, just to the west. Amesbury, also in Wiltshire, has also had its supporters. However, at none of these places is there any reason why they should have chosen for a major battle, in contrast to Allington which is in exactly the right place for the tactical and strategic situation of the time.

Locations of Power – The Kingdoms of Britain:

The series of earthworks known as Offa’s Dyke defined the frontier between the Britons and the Mercians. Within Wales, the post-Roman political landscape survived more intact. Topography, in the form of mountainous borders that defied potential enemies and political resilience, allowed the kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys, in particular, to consolidate their territories and develop into durable kingdoms and ‘principalities’, that would last until the Norman Conquest of Wales in the twelfth century. In Ireland, aggressive kings constructed elaborate structures of overlordship that allowed a few royal kindred groups to dominate whole provinces. These kindreds were large and complex, resulting in a great deal of competition for royal succession. Despite this inherent instability, exceptionally successful dynasties were able to construct and maintain large polities. The large northern and southern branches of the Uí Néill effectively dominated most of the north and east Midlands, while the Eoganacht dynasty came to rule Munster.

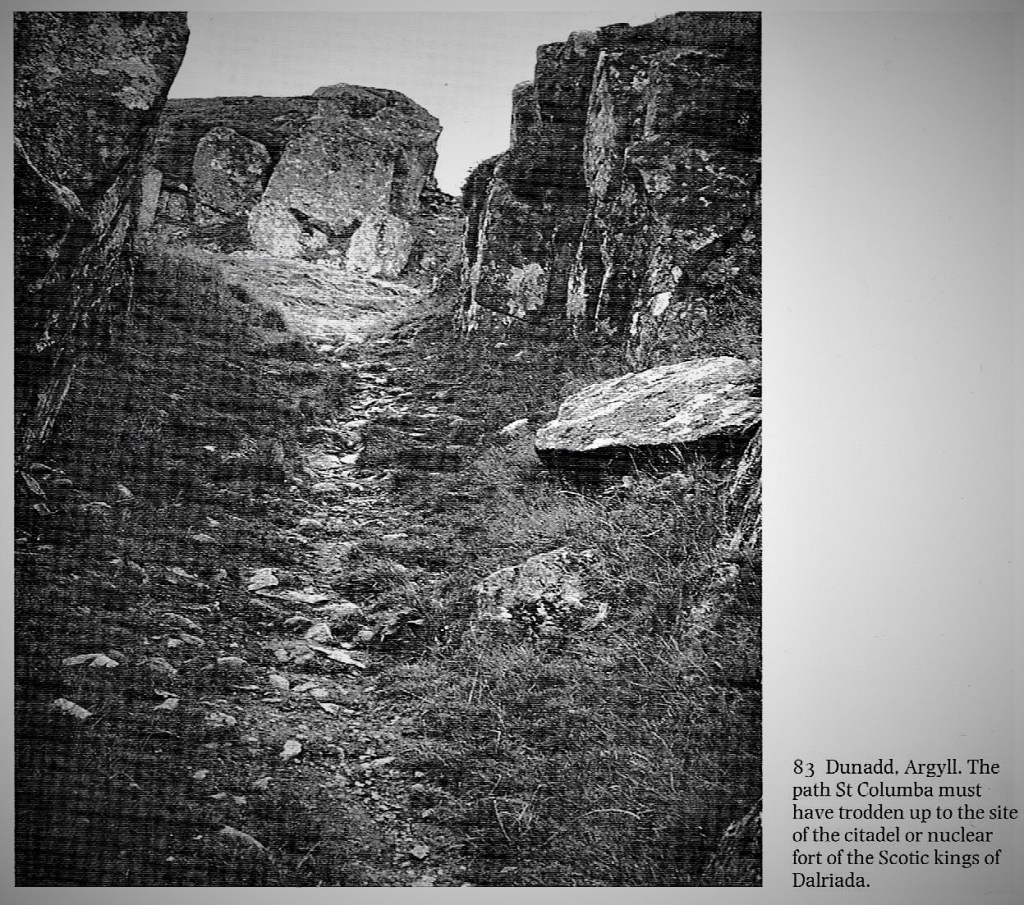

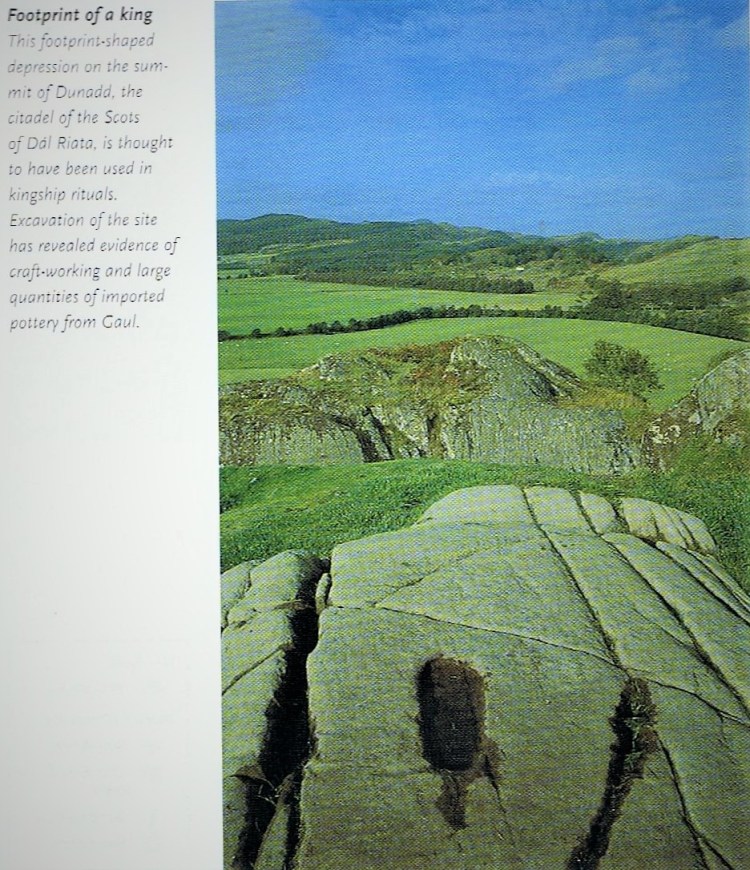

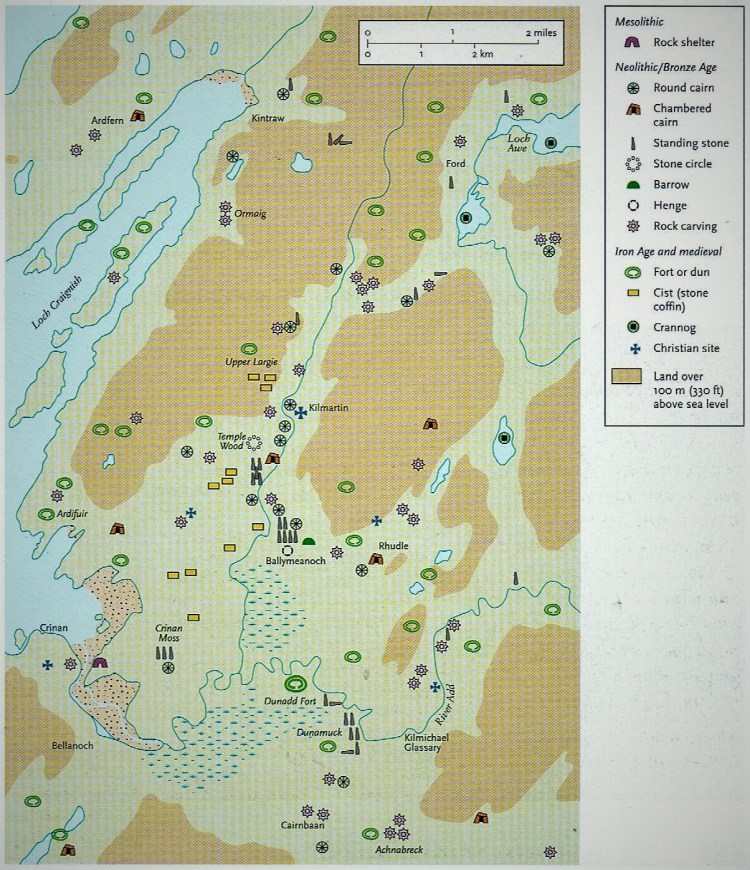

Traditionally, the extension of the kingdom of Dál Riata was not so much a recent Irish colony as the eastern part of a Gaelic-speaking zone that straddled the North Channel. The physical proximity and maritime culture encouraged deep connections between western Scotland and Ireland, which persisted throughout the Middle Ages. The characteristic form of royal settlement in Celtic-speaking Britain was the hill-fort. Although sometimes built on the sites of Iron Age hill-forts, the early medieval hill-fort was a new phenomenon. It tended to occupy a craggy knoll, rather than towering heights, and the elaborate masonry or earthwork ramparts were enclosed relatively small areas suitable for the residence of the king and his extended household. Although they are architecturally quite different from the later medieval castles, these fortified dwellings served a similar range of domestic, administrative and ceremonial functions. Where these have been excavated (for example, at Tintagel and Dunadd in Argyll) they have produced similar kinds of evidence for the manufacturing of fine metalwork and the importation of pottery, glassware and wine from the continent via the Irish Sea. These finds attest to regular trade with Gaul. Early medieval kings were keen to legitimise their power by associating themselves with sites of ancient authority. This is most obviously apparent from Dunadd, the chief royal fortress of Dál Riata, which, as shown on the map below, occupies a rocky knoll overlooking the richest prehistoric ritual landscape in western Scotland. Since Neolithic times people have been coming to the Kilmartin valley in Argyll to bury their dead, erecting standing stones and creating rock art on outcrops. These ancient associations cannot have been lost on the founders of Dunadd and were arguably a primary motive for the site’s selection.

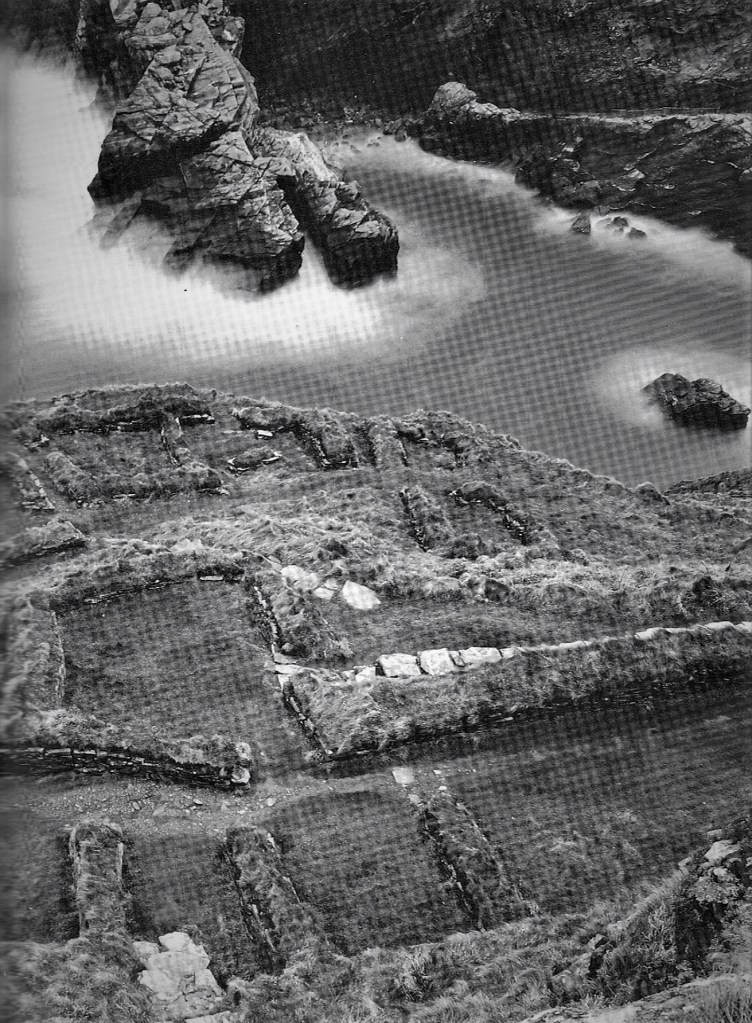

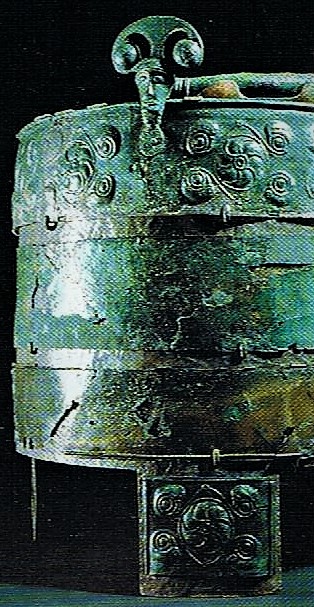

The Kilmartin valley in Argyll, shown on the map above, is the site of one of Scotland’s richest archaeological landscapes, with a continuous series of monuments dating back to the Neolithic age. These monuments confirmed the valley as a site of power and were almost certainly one of the reasons why the Scots of Dál Riata chose the craggy hill of Dunadd as the site of their capital. The large royal fort they built there included some symbolic carvings probably associated with the appointment of kings. A remarkable series of carvings near the summit of Dunadd suggest that it served as the inauguration place of the kings. The carvings included a single-shod footprint, a rock-cut basin, an incised boar and an ogham inscription. The footprint echoes royal ceremonies documented in Ireland, with their symbols of the physical union between the king and the land, and is part of a broader phenomenon found throughout Britain and Ireland where royal authority sought to create links with the ancestral path through the re-use of ancient sacred places. The highest point of the Dunadd complex was occupied by a fortified dwelling, built in the local dry-stone tradition. Such dwellings, first known from the Iron Age, are ubiquitous in western Scotland and are taken to indicate the presence of free property-owners. At Dunadd, however, the building was enclosed within two additional ramparts, creating considerable additional space for the royal household. Within this area was a royal workshop where fine metalworkers made brooches and other jewellery. The growth and development of Dunadd are closely linked to the fate of Dál Riata. It was founded in the sixth century and grew into the most important royal site in Argyll during the seventh and eighth centuries. The complex survived sacking by Picts in the mid-eighth century, only to be abandoned as the centre of Scottish power shifted east in the ninth century.

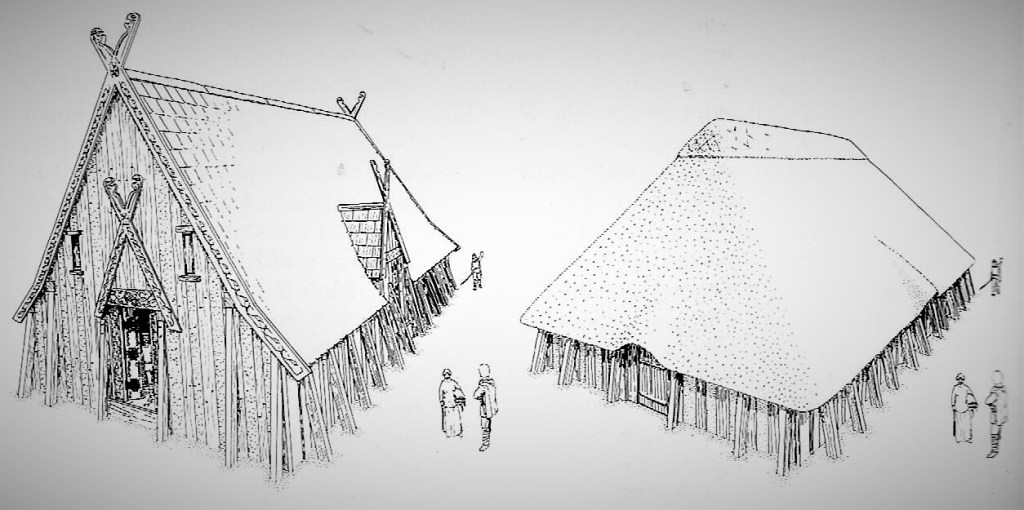

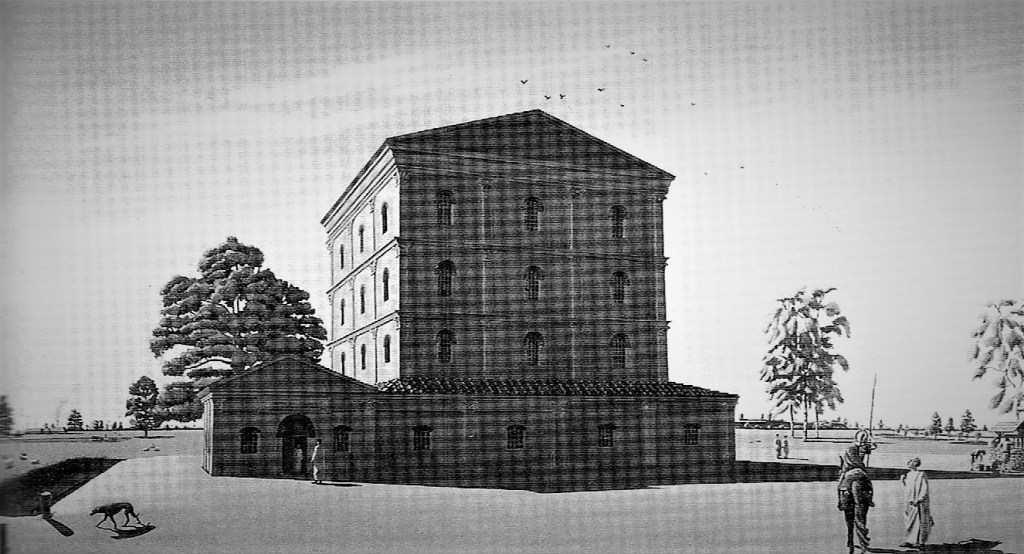

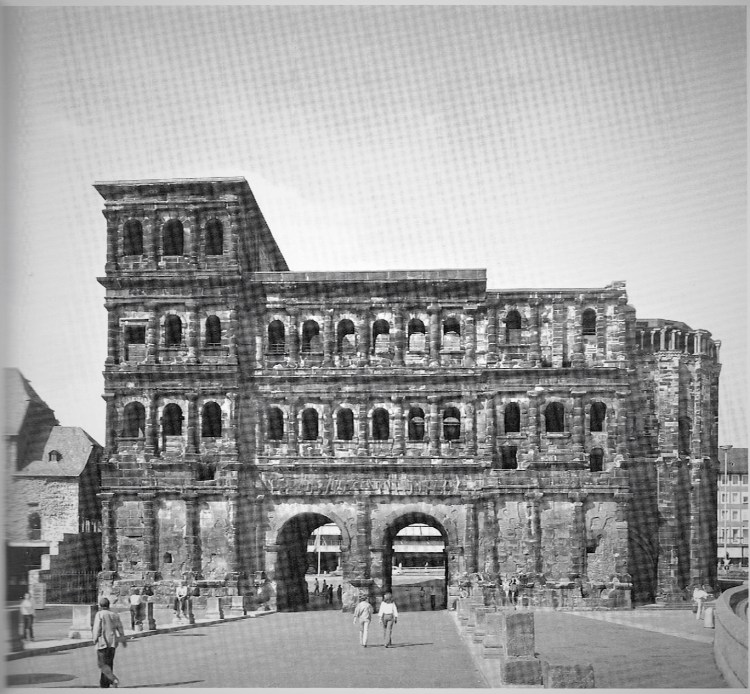

It was to take advantage of similar associations with past power that Anglo-Saxon rulers sometimes reoccupied ruined Roman sites, most typically at Winchester and York, where the late Roman town walls may have provided a measure of security along with prestige. They developed an élite architectural tradition that had more in common with post-Roman practices on the Continent. Bamburgh, Northumbria’s royal seat, is the major exception to the rule. It is a former British hill-fort perched on a coastal crag, a clear indication of the native contribution to the social structure of Northumbria. Conceptually, at the heart of the Anglo-Saxon royal complex was the hall, where the main ceremonial and administrative business of the lord was conducted. Excavations of royal halls, such as at Yeavering and Northampton, suggest that the descriptions of the magnificent hall of Heorot in Beowulf may not be greatly exaggerated.

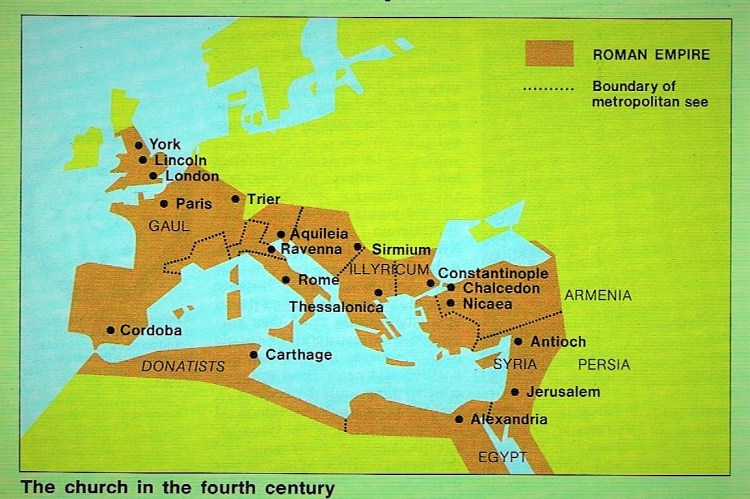

Unlike the British hill-forts, Anglo-Saxon royal centres do not seem to have been a focus of either trade or manufacturing. However, the Anglo-Saxons did participate in a cross-Channel trade network, which encouraged the development of royal emporia and coinage. Newly-established trading centres, such as Hamwith (Southampton) and Ipswich, quickly developed into significant towns, which became the commercial rivals of London. Despite East Anglia’s decline as a dynastic power after the fall of the House of the Wuffings, trade with the continent continued and in the eighth century, the minting of silver coins called sceattas began there. These coins have been found across a wide area of Frisia and northern Germany while imported items of bronze, iron and pottery have been excavated from East Anglian sites. Ipswich was almost certainly the leading port and industrial centre of the region. Kilns discovered there once produced large quantities of pottery which were diffused over a wide area of England and northern Europe. Dunwich, too, was a thriving fishing port that could pay the king an annual rent of sixty thousand herrings. Clearly, economic prosperity was not dependent on political power and prestige. It was also during this period that Norfolk and Suffolk began to emerge as distinct entities. There had always been differences between the settlers north and south of the Waveney, and these differences asserted themselves more as the power of the Wuffings declined. This division was the result of the reorganisation of the bishoprics by Archbishop Theodore shown on the map of the Heptarchy above, confirming the establishment of the Roman-Saxon Church. He divided the East Anglian diocese, with a new ‘seat’ at North Elmham for Norfolk, while Suffolk’s church continued to be administered from Dummoc.

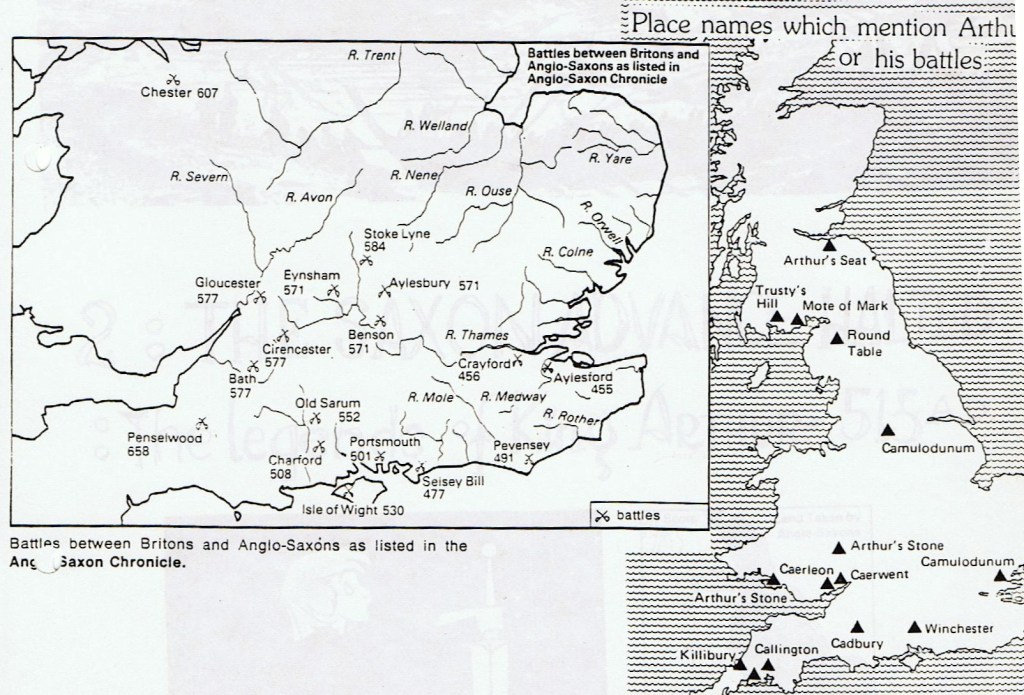

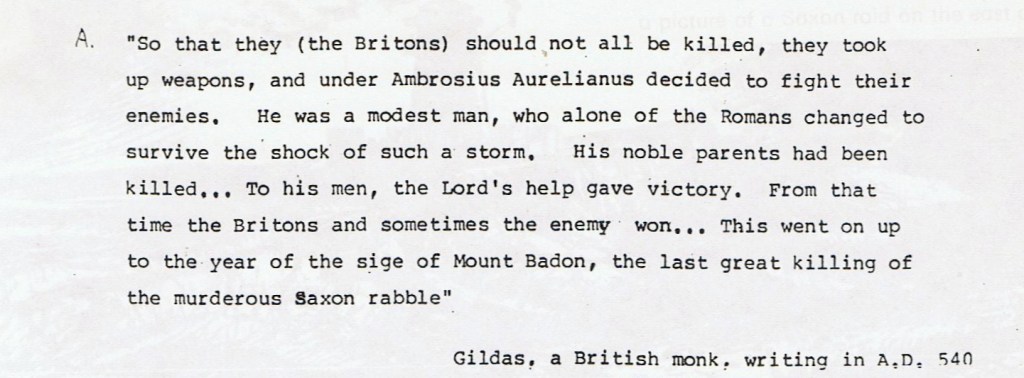

By the time of Egbert’s reign, the Anglo-Saxons were a very different people from those who fought the legendary Battle of Badon in 516, or even the Battle of the River Idle a century later. They were now all Christian and in many ways cultured and civilised. They had established settlements by clearing forests, often naming them after the local chief, as in Wolverhampton (‘Wulfhere’s home village’) and Birmingham (‘Beormund’s people’s home’). Egbert’s campaigns of 825 and 829 marked an important stage in the growing political unity of the English: he brought the resources and strength of the south, from Kent to Cornwall, under centralised authority at the time when the very existence of England was to be challenged by the warriors of Scandinavia. Wessex came to overshadow their Kentish and South Saxon neighbours while expanding westwards into British territory. Throughout this period, London, still the largest port in Britain, remained the greatest political prize in Britain, and control of London was the source of an extended conflict between Mercia and Wessex, ended only by the disruptions of the Viking wars. Egbert was not always successful. In 836 he lost a battle to the Vikings, though two years later he won an even larger battle against the combined forces of the Vikings and the Welsh at Hingston Down near Plymouth. By that time something was known of the relentless northern warriors, and though they were called ‘Danes’, many were from other Scandinavian countries as well. At this stage, Egbert was the only English king to put up much resistance against them, and after his death in 839 England sank steadily into decline. Egbert was a remarkable king, reigning over Wessex for thirty-seven years, the ancestor of all of England’s future monarchs except for the Tudors. His early life had been spent at the court of Charlemagne, which prepared him to become a great king, but like many of those who followed him, he would never have obtained the throne at all if a cousin had not died prematurely.

(to be continued)

Sources:

William Anderson & Clive Hicks (1983), Holy Places of the British Isles: A guide to the legendary and sacred sites. London: Ebury Press.

Catherine Hills (1986), Blood of the British: From Ice Age to Norman Conquest. London: Guild Publishing.

Derek Wilson (1977), A Short History of Suffolk. London: Batsford.

Sam Newton (2003), The Reckoning of King Raedwald: The Story of the King linked to the Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. Colchester: Red Bird Press.

Stephen Driscoll et. al. (eds.) (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British & Irish History. London: Penguin Books.

Philip Warner (1973, ’76), British Battlefields: The Midlands. Glasgow: Osprey Publishing/ Fontana.

David Smuurthwaite (1984), The Ordnance Survey Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain. Exeter: Webb & Bower.

Irene Richards & J. A. Morris (1936), A Sketch-Map History of Britain & Europe to 1485. London: Harrap.