Revisiting the Story of Israel – “the Children of Abraham”:

The Bible is about the story of Israel, and of the new Israel which is the Christian Church. Christianity was nurtured in the cradle of Judaism, and the ministry of Jesus cannot be properly understood apart from the political situation of the first century A.D. (C.E.) and the messianic expectations of the time. In my second examination of the theology of the last fifty years on this theme, I am revisiting and reviewing the work of John Ferguson, a major influence on many of us who were engaged in our own ‘ministries of reconciliation’ in the mid-to-late 1970s. In his 1973 publication for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, The Politics of Love, Ferguson pointed out that it was true of most societies, until comparatively recent times, that the basic unit was not the individual but the group, the ‘extended’ family of the tribe, the neighbourhood, the local community and the nation, deriving from common ancestors. It was the proud boast of the Jewish people that they were “the children of Abraham” (Mt. 3: 9). This sense of ‘corporate personality’ or ‘collective identity’ is important since religion and morality are both matters for the whole community. There is individualism in both the Old and New Testaments, but it is always seen against the background of collective action in the interests of the group. This can be seen in the books of Jeremiah and Ezekiel, and in earlier books too, in which Yahweh is primarily the God of Israel and only secondarily the God of individual Israelites. The complex interrelations between the individual and the group is seen in the practice of representing groups under the guise of individuals, as the tribes of Israel. In the ‘Servant-songs’ of Isaiah, the ‘servant’ is explicitly identified with Israel:

He said to me, “You are my servant,

Israel through whom I shall win glory.

Isaiah 49: 3.

Paul’s letters are the oldest surviving document of Christendom, older than the four Gospels. Paul was aware of God’s grace to individuals in his grateful awareness of that grace in his own life. He does not forget individual men and women; the personal greetings at the end of his letters are one of the warmest parts of them. But his thinking emphasises the importance of their belonging to groups, to the nascent ecclesiastical fellowships. His letters are addressed to the congregation of God’s people at Corinth (1 Cor. 1: 2), to the Christian congregations of Galatia (Gal. 1: 2), and to the congregation of Thessalonians (1 Thess. 1: 1). By itself, this is little enough to prove the point, but he clearly thinks of them as being one united community: There is one body and one Spirit, as there is also one hope held out in God’s call to you; one Lord, one faith, one baptism; one God and father of all, who is over all and through all and in all (Eph. 4: 4-6), and again, You are all one person in Christ Jesus (Gal 3: 28). Where that corporate unity has been broken the church has ceased to be the church: Is Christ Divided, he asks (1 Cor 1: 13 AV). When Paul speaks continually of the Church as the body of Christ (1 Cor 12: 12-27; Eph. 4: 4-46; Col 1: 18), he is following the traditional practice of representing the group as an individual, and he carries on the metaphor to show how each individual can only find their identity within the group, as a limb of the body.

When Paul views the great sweep of Hebrew history, he thinks of the calling of the group, the nation. The Jewish people have their peculiar vocation; the Gentiles, or Greeks, are invited to share in that vocation. Paul’s language continues the personal metaphor, calling the two groups the natural-born son and the adopted child (Gal. 3: 29). The Jews were entrusted with the oracles of God (Rom. 3: 2). The Gentiles were strangers to the community of Israel (Eph. 2: 16), but the Christ Jesus has reconciled the two into a single body to God through the cross (Eph. 2: 16), and the Gentiles have become fellow-citizens with God’s people (Eph. 2: 19). Paul’s language is couched in corporate terms because in his thinking God is concerned with both “the Jews” and “the Greeks”, and not simply with individuals who happen to be Jews or Greeks. In fact, Paul was, in the words of C. H. Dodd, in quest of the Divine Commonwealth. The keyword here is ‘koinonia’, which is variously translated as ‘fellowship’, ‘communion’, ‘contribution’, ‘distribution’, ‘partnership’ and ‘sharing’. The word is found in Acts, referring to the common life of the Church (2: 42), and of the ‘sharing’ of material resources (4: 32). Both passages are to be seen in the light of the immediately preceding gift of the Holy Spirit. Indeed, the common life of the Church is to be seen as a sharing of the Spirit (Phil. 2: 1), a ‘fellowship’ in the Holy Spirit (2 Cor. 13-14), and also a ‘fellowship’ created by the Holy Spirit. This ‘community’ finds its being in sharing the life of Christ in the communion service (1 Cor 10: 16-17).

The ‘ecclesia’ also finds its expression and outcome in contributing to the needs of God’s people (Rom. 12, 13), in a common fund (Rom. 15: 26) in being ready to share (1 Tim. 6: 19). Above all, it also meant shared suffering (Rom. 8: 17; 2 Cor. 1: 7; Phil. 3: 10), shared with Christ, but shared also with one another. In summation, Paul can count Philemon as his partner in faith, one in fellowship with him. The corporate unity of the Church is a valid part of Paul’s witness. The context of Paul’s writing on the Eucharist makes it clear that he is thinking of the Church as the new and true Israel (1 Cor. 12: 12; Eph. 4: 13). The word ‘ecclesia’ means a public assembly of citizens summoned by a herald and was used in the Greek version of the Old Testament for the commonwealth of Israel. For Paul, there was no question about the starting point for this new commonwealth. It was always Jesus, as Tom Wright attests, …

Jesus as the shocking fulfilment of Israel’s hopes; Jesus as the genuinely human being, the true ‘image’; Jesus the embodiment of Israel’s God. … Jesus, above all, who had come to his kingdom, the true lordship of the world, … by dying under the weight of the world’s sin in order to break the power of the dark forces that had enslaved all humans, Israel included.

Jesus, who had thereby fulfilled the ancient promise, being “handed over because of our trespasses and raised because of our justification.” Jesus, who had been bodily raised from the dead on the third day and thereby announced to the world as the true Messiah, the “son of God” in all its senses (Messiah, Israel’s representative, embodiment of Israel’s God). Jesus, therefore, as the one in whom “all God’s promises find their yes,” the “goal of the law,” the true seed of Abraham, the ultimate “root of Jesse.”… the one whom to know, Paul declared, was worth more than all the privileges that the world, including the ancient biblical world, has to offer. Jesus was the starting point. And the goal.

The Political Testimony of the Old Testament:

John Ferguson maintains, therefore, that The Old Testament is a political book. In Exodus 21-23, we have a code of laws, sometimes called “The Book of the Covenant”. They are laws for a people, and the end of the last chapter makes it clear that the ‘you’ addressed is the whole Hebrew people. But if this is true of the Book of Covenant it is true also of the ten commandments. We are used to thinking of these as ethical injunctions to individuals, but they are the summary of a code of behaviour for a nation and for the Jewish people to do right, which uses the Deuteronomic introduction; Hear, O Israel (Deut. 6: 4). The code of Deuteronomy, whatever its date, does seem to be an expanded and humanised edition of the Book of the Covenant; it too is a code for a nation. Throughout the historical books, religion and politics are inextricably interwoven. Individuals may, of course, show righteousness and unrighteousness, but their offences are seen as corporate. Personal offences lead to political disaster and are requited upon the family group. Even when the principle is affirmed in Deuteronomy (24: 16), Jeremiah (31: 29-30) and Ezekiel (18: 2) that the individual stands responsible for his own sin, we cannot escape the corporate and political element. Deuteronomy, Jeremiah and Ezekiel are all concerned with the regeneration of Israel, and Jeremiah is intimately concerned with what we should today we would today call his government’s foreign policy.

The prophets are concerned with social and economic righteousness, as I have shown in my previous article on these themes. Amos rails against the fraudulent exploiters of the poor who are only interested in the price of corn and selling their wheat, giving short measure … and taking overweight in silver, tilting the scales fraudulently and selling the dust of the wheat. They buy the poor for silver and the destitute for a pair of shoes (8: 4-6). Amos is a particularly strong mouthpiece for social justice, but he stands squarely in the central prophetic tradition dominated by Isaiah and Jeremiah (see 3: 12 and 5: 1 respectively, plus the last chapters of Isaiah (58: 6)). As I have noted, the authors and editors of The Radical Bible (1972) had no difficulty in identifying suitable passages to include in their volume. We should not try to turn the Bible into a Marxist tract: it is not a work of political economy, but it is more radical than many Marxists and Christians care to admit. It is not merely concerned with the inner self of the individual; it is concerned with the overall health and wholeness of society. It was impossible for anyone living in a tribal society to conceive of a purely individualistic ethic and not to think collectively. Even by the time of Jesus, it would have also been impossible for a Jewish Rabbi to divorce the personal from the political. Even if we were to exempt Jesus himself from these limitations, his words could not have been heard and understood by his listeners as isolating the personal from the social, corporate and political. They would have heard his words through their contemporary ‘filter’ created by the climate of thought, their ‘tribal’ presuppositions and their framework of speech.

Christianity was therefore nurtured in the cradle of Judaism, and the Christian approach to politics cannot be understood apart from the political situation of the first century C. E. and the messianic expectations of that time. In order to understand these expectations, we need to go back into the Hebrew scriptures to trace the origins of the messianic traditions. Israel of old had been a theocracy, a single political and religious community, with no separation of the sacred and the secular. David (c. 1000 – 961) established a monarchical system after the ad hoc rule of Saul and established an Israelite Empire stretching from the border of Egypt to the Euphrates. As a powerful political state, Israel rapidly developed institutions which in many ways resembled those of its neighbours. These were politically necessary but entirely new to the Israelites since, only a few years previously, ‘Israel’ had consisted of a few loosely organised tribes under foreign domination. Efficient government required a professional civil service. David recruited this partly from native (Israelite and Canaanite) sources; but he also found it necessary to employ skilled scribes from other countries who had greater experience of administration, especially from Egypt. This central government at Jerusalem provided the king with advice on political problems, in the wisdom tradition of the Near East; it also administered justice under the king as chief judge, collected taxes and dues, organised a state labour force, kept administrative records and archives, and dealt with diplomatic affairs, maintaining correspondence with foreign powers and negotiating international treaties.

These developments had far-reaching consequences. In particular, they facilitated the stratification of Israelite society. The Canaanite cities were already accustomed to a highly stratified social structure, but this was the first time that freeborn Israelites had experienced rule by a wealthy, urban élite whose interests were far from identical with their own. In the reigns of David and Solomon, Jerusalem became a wealthy, cosmopolitan city in which this oligarchy enjoyed a standard of living far beyond anything which could have been dreamed of; but, apart from now being free from foreign oppression, the ordinary Israelite population, still consisting mainly of farmers, hardly felt the benefits of Israel’s new imperial wealth and status. Supreme above the new upper class stood the king. Whatever the divine sanctions by which he claimed to rule, and however much he might rely on the loyalty of the ordinary Israelite, one of the main sources of his power was his professional army, which owed him a purely personal loyalty. Many of its members were foreigners who had no reason for loyalty to Israel or to its God (II Sam. 8: 18; 11; 15: 18-22; 20: 7, 23). It was these ‘servants of David’ who, during Absalom’s rebellion, defeated the rebels – ‘the men of Israel’ – and restored David to the throne (II Sam. 18: 7). With his position secured by his personal army, David was able to play the part of an oriental monarch, gathering around him a court that imitated the splendour and ceremonial of foreign courts and tending to become isolated from the common people (II Sam. 15: 3f.). He was, however, too shrewd to succumb to the temptation of claiming for himself the semi-divine character that was claimed by other monarchies at the time. He knew that ultimately he could not retain the loyalty and affection of his people, and also that too great a departure from the old social and religious traditions of the Israelite people would put his throne in danger.

Solomon’s most enduring achievement was the building of the temple at Jerusalem. But he certainly can have had no inkling of the importance which this was to have in later times. He is also praised in several biblical passages for his wisdom (I Kings 3: 9-14), 16-28; 4: 29-34; 10: 1-10). But in only one of these passages does ‘wisdom’ mean statesmanship. Solomon may have been wise in other respects, but statesmanship was certainly not one of them. The early promise of political greatness for Israel was not fulfilled. Nevertheless, Israel during the reigns of David and Solomon had undergone fundamental changes which would never be reversed. It had been brought into the world of international politics, but also of international culture. The new confident, national spirit inspired by David’s achievements had given the people of Israel a new pride, but after the death of Solomon, the Kingdom was divided in two.

The Messianic Hope:

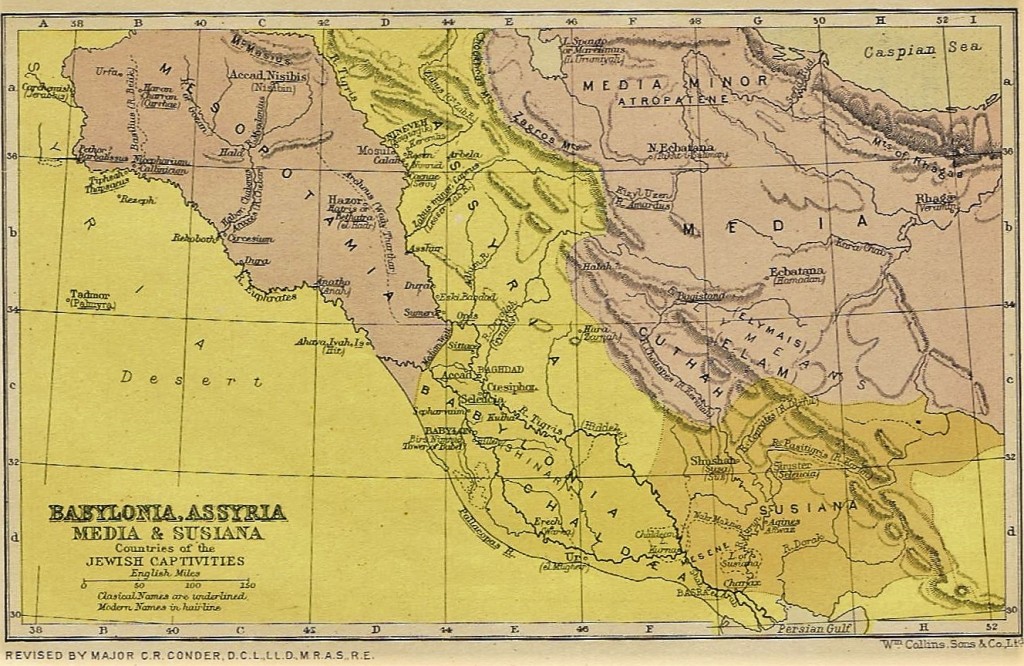

What, then, was the Messianic hope? The Israel of David and Solomon had been a theocracy, a single political and religious community. The disasters of 721 B.C. and 586 B.C., resulting in the destruction of Jerusalem and the deportation of the inhabitants further broke the unity. The exiles in Babylon had to learn to live a life dedicated to God in an alien political environment, and Jeremiah more than any other had shown the way towards this. But the comprehensive nature of the Hebrew religion made it impossible to divorce the sacred from the secular. Fifty years after the deportation to Babylon, the empire fell to Persia and the captive exiles were allowed to return home to Judah. They continued subject to Persia for two centuries, then after the coming of Alexander the Great, were subject to Greek dynasties, the Seleucids of Antioch and the Ptolemies of Egypt. The extreme hellenising policy of Antiochus Epiphanes led to revolt, and the accidents of history produced nearly a century of quasi-independence under the Hasmoneans, arousing a continuing desire for full independence which seemed always improbable but never impossible. The arrival of Pompey in 63 B.C. was the effective end of Israel’s claims to independence, though they dragged on among extremists for a quarter of a century which saw violent uprisings, by Alexander in 57, Aristobulus and Antigonus in 56, Alexander again in 55, Pitholaus in 52, and Antigonus in 41. In the end, Herod the Idumaean, a hated foreigner, prevailed. It was Herod’s death in 4 B.C. which brought about a troubled three-quarters of a century, with Rome never completely or consistently in charge. During this period, a shared apocalyptic vision developed in which the Messiah, the Anointed, was to be the deliver, the liberator, God’s ‘vicegerent’ of the restored kingdom. As T. W. Manson put it,

The religious soul of Israel must find a body. Hence the Messianic hope, the hope of restoring on a higher level the unity of national life that had been broken at the Exile.

There was a strong tradition that the Messiah would be a military leader. This tradition appears in Psalm 2: 9, in which the Messiah was foretold to break the nations with a rod of iron, and in Isaiah 9: 4-5, in which he was imagined as shattering the yoke which fetters Israel. The idea of a military Messiah was also especially strong in the apocryphal and historical literature of the pre-Christian epoch. For example, in the ‘tremendous seventeenth’ of The Psalms of Solomon, one of the most important of the Messianic visions, the Messiah would reduce the Gentiles under his yoke and in 2 Esdras 12: 31-33, the Messiah is revealed as the lion who is to destroy the Roman Empire. The most extreme account of the military Messiah is in Ezra 4, where the Messiah is depicted as the merciless conqueror of the Gentiles. So too in the writings of Philo, the foreigners would be repelled by the arms of the righteous under the leadership of a military hero. The general sense of the apocalyptic literature of the period is that, although the Messianic kingdom would be a peaceable kingdom, it would be imposed by force. The major passage to the contrary is the familiar one from Zechariah (9: 9-10). It is therefore significant that Jesus chose to fulfil that strand of prophecy. The second major aspect of the Messianic hope is that the scattered tribes of Israel would be reunited in a restored Jerusalem. The thought dates back to the earlier periods of exile. Isaiah announced that…

On that day, the Lord will make his power more glorious by recovering the remnant of his people, those who are still left, from Assyria and Egypt, from Pathros, from Cush and Elam, from Shinar, Mamath and the islands of the sea … On that day, a blast shall be blown on a great trumpet, … and those dispersed … will come in and worship the Lord on the holy mountain, in Jerusalem.

Isaiah 11: 11; 27: 13.

In the Psalms of Solomon, it is the Messiah himself who will restore Jerusalem (17: 33). Philo too writes of the ‘restoration of the exiles’; he was a traditionalist and this was part of the tradition. That tradition varied as to the role of the Gentiles and Isaiah’s vision of the extension of it was largely forgotten:

… it is too slight a task for you, as my servant,

to restore the tribes of Jacob,

to bring back the descendants of Israel:

I will make you a light to the nations,

to be my salvation to earth’s fathest bounds.

Isaiah 48: 6

The Political Context of Jesus’ Ministry:

The apocryphal first book of Enoch, a composite book, though including the work of a highly original writer, preserves the vision of the Messiah as the ‘Light of the Gentiles’ (48: 4). It was this vision that Jesus uses in his view of his Messiahship, with his explicit identification of himself with the Servant. The gospel-writer, in recording the song of Simeon, saw the coming of Jesus as “a light that will be a revelation to the heathen” (Luke 2: 32). Philo, though strongly Hellenised, looked forward to the eventual submission of the nations, whether freely or from fear. In general, the Messianic hope was for a returned Israel, however. The Gentiles would be conquered and driven away. There was no thought that they might be redeemed. John Ferguson goes on to argue that attempting to eliminate politics from the New Testament is to seek to eliminate historical texture from it and thereby to eliminate its contextual reality. In the New Testament, the idea of a military Messiah is never taken up, except for one passage in Revelation (19: 11-21), and even in that, the warfare is metaphorical or spiritual. Indeed, the most significant writers of the New Testament, such as Luke, make clear the contrast of Jesus’ Messiahship with the number of messianic pretenders who raised the flag of violent revolt (Acts 5: 35-39).

When Rome first came on the Palestinian scene, it had appeared as just one more competitor in the scramble for power, though a brutal and ruthless one at that. It succeeded in imposing peace and good order on the Hellenistic world, and adding to its cultural unity a political cohesion which it had lacked. It becomes appropriate to talk of the Graeco-Roman world in the first century B.C. The transformation of a predatory and aggressive power into the presiding genius of a highly-civilised international society was in large measure the work of the emperor Augustus, whose reign covers the transition from B.C. to A.D. (C.E.). The imperial rule was accepted willingly enough by most its eastern subjects. No doubt there were pockets of discontent of which Palestine was one, but with inherited memories of prolonged anarchy and misrule to which the strong arm of Rome had put an end, most of them knew when they were well off. Augustus had emerged from the civil wars as undisputed master of the whole Hellenistic world as far east as the Euphrates. Within the imperial frontier a few puppet principalities were allowed to survive, as a useful ‘buffer’ or an administrative convenience, but the greater part of the annexed territories was given a provincial organisation which amounted to to a business-like and efficient bureaucracy. Frontier provinces were placed under military governors in command of legionary troops, with troops, with the title ‘legate’. They were appointed directly by the emperor and were under his personal supervision. Peaceful provinces away from the frontiers had civilian governors with the title ‘proconsul’. They were nominally appointed by the Roman Senate, but the emperor had them well in hand. Minor provinces like Judaea might be administered by governors of inferior rank appointed by the emperor, with the title ‘prefect’ or ‘procurator’.

Within his province, the governor was invested with all the authority of the empire, subject only to the remote control of the emperor in Rome. He was responsible for every aspect of administration, but most particularly for the administration of justice, which he exercised by holding regular assizes in the principal cities of his province in turn. Roman rule, however, was not so severely centralised as to leave no room for a measure of local government. Throughout the eastern provinces, there were numerous partly self-governing cities. They might be ancient Greek city-states, like Athens or Ephesus, or cities founded after their pattern by Hellenistic monarchs, like Antioch-on-the-Orontes, the capital of the province of Syria. Or they might be Roman colonies, like Philippi in Macedonia. The original colonists had been former legionaries, who were given grants of land in the conquered territories by way of pension. Their institutions were closely modelled on those of the mother-city, and they took pride in their Roman citizenship. All these cities continued to be administered by their own magistrates and senates, who were allowed to exercise a certain degree of autonomy. It was no more than a shadow of the sovereign independence of the Greek cities in their prime, and it shrank with the years.

In Jewish Palestine, following Herod’s death, there followed first a period of divided authority between his three sons. There was an open revolt connected with the census of 6 C.E. when the Romans took over the direct administration of Judaea and Samaria. The census was associated with the takeover; it was to form the basis for the economic administration. The case against the publicani, the tax-collectors, was that they collaborated in the colonial economic rule; it should be noticed that Jesus, in associating the tax-collectors with ‘sinners’ and prostitutes was making a highly charged political comment (Mt. 9: 10; 18: 17; 21: 31). The Jewish patriots were aroused by the census, and an independence movement pledged to violent resistance formed under the leadership of Judas of Galilee, who is described by the Jewish historian Josephus as a “dangerous professor”. Josephus calls the rebels, “brigands” or Sicarii (‘dagger men’). Judas ben Hezekiah got a small army together and raided an arms store (a royal depot) at Sepphoris, storming the town. Every rebel got a weapon, but his revolt was crushed by the Roman legions, the town was burnt to the ground and its people were sold into slavery. Two thousand of his revolutionaries were crucified outside the town along the road and since Nazareth was not far away, the ten-year-old Jesus may well have seen the crosses in the distance. He may even, as a boy, have helped his father in the rebuilding of Sepphoris. By the time Jesus began his ministry, the very name ‘Galilean’ therefore came to mean ‘rebel’, synonymous with ‘Zealot’ or ‘freedom fighter’, and the Galileans were seen as born fighters. Although they were fighting, as they saw it, for God’s law and His rule, the people in the south regarded them as dangerous fanatics and anarchists, as Jesus had already discovered on a family visit to Jerusalem at Passover time, aged twelve.

At that time, there were still those who could remember Palestine before Pompey and many more who could remember it before Herod. There were also almost as many points of view among them as ‘learnéd’ men arguing about them. But all would agree that their people, the Jewish people, were a special people called by the One God to take a special part in the history of the world. Jesus would have no quarrel with that. But everything turned on what was meant by the words, ‘God’s People’. It was not enough just to use the words, as though it was quite plain what they meant and as though everybody agreed about that. It wasn’t plain and they didn’t agree. This was what the great debate was about, as Jesus no doubt found out for himself when he visited the temple in Jerusalem at the age of twelve and found himself having to prolong his participation in it. The scribes and Chief Priests were using the same words as he was but making them mean very different things. Everybody knew, however, that things could not go on the way they were, because the situation in which the Jewish people found themselves as the subjects of a foreign empire, was really intolerable. The only people who thought it wasn’t were the members of the aristocratic government in Jerusalem, who owed their being to their Roman overlords. In Judaea, the immediate period following the uprising of the two Judases seems to have been peaceable: Quirinius deposed the high priest Joazar, a reminder that Rome controlled even the highpriesthood, including a High Priest who had appeased them. Valerius Gratius, the procurator for the decade from A.D. 15 to 26, actually deposed and appointed four high priests; his last appointment was Caiaphas.

The natural effect of this was to alienate the patriotic extremists from the highpriesthood. The common people and their leaders longed for a great change. They felt that the root of the trouble was that they were an occupied country; if only they were free and ‘independent’, the ‘good time’ they all longed for would come. It was the presence of unbelieving foreigners – Roman soldiers, Greek citizens, foreign landlords – that made living as ‘God’s people’ impossible. Most people believed in some kind of what we would now call ‘segregation’, keeping themselves ‘separate’, having nothing to do as far as possible with foreigners. Lots of ordinary people, of course, simply could not avoid meeting foreigners and having to deal with them; using their money with its hated image of the emperor on it, carrying army baggage, working on foreign estates, selling market produce in Greek cities. ‘Religious’ people, like Pharisees and Zealots, had as little to do with foreigners and they certainly would not have a meal with him. The word ‘Pharisee’ itself meant ‘separatist’. Foreigners were not the only trouble for them, however, since living as ‘God’s People’ meant, for them, keeping God’s laws. Those laws were written down in the ‘Torah’ and were kept up to date by Bible scholars. For example, the scholars worked out the rules of what ‘working on the Sabbath’ meant in the first century, a very different era from when the ancient Hebrews were nomadic tribes and herdsmen. Many people believed that it was because they had not kept God’s laws that He had allowed the Romans to occupy their country.

The Zealots wanted to go much further, believing that matters could only be set straight by a Holy War, the violent overthrow of Roman rule. They could point to many stories and passages in the Bible to prove it. This was the debate in the Sanhedrin and the Temple in Jerusalem, but it was also the debate in the marketplaces in the villages. Just as he was drawn into the debate in the temple, so too Jesus was drawn into it during the fifteen or so subsequent years when he was living and working in Nazareth and the Galilean countryside. He listened and argued, reading the Bible scrolls carefully in the small village synagogue in Nazareth or the larger one in Capernaum, where he settled during his ministry. These were rarely quiet places, but more like local village halls, housing a school, a law court and a place of worship, with its library of ‘Torah’ scrolls behind the central ‘Bimah’. But there he could do his own thinking as well as listening to both Pharisees and Zealots, before making up his own mind. The issues had slowly become clear to him when, at about the age of thirty, he began his ministry after visiting his cousin John on the banks of the southern Jordan River.

Somebody had to take a stand. The leadership of the Jewish people was at stake at a crucial moment in their history, and Jesus knew where he stood. Yet the sound of the villagers singing a psalm still rang in his ears, a psalm that had been written not long before, in the time when Pompey had first taken over the country, in which the worshippers ask God to give them their own king again, one like David:

… a king strong enough to shatter the pagan rulers,

and to rid Jerusalem of the foreigners

who are trampling her streets

and destroying her.

Psalm 83.

Making relations between the Romans and the Jews even worse, the tactless anti-Semitism of Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judaea and Samaria between 26 and 36 C.E., led to several disturbances, eventually culminating in all-out war in 66 and the sack of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. Philo describes him as “naturally inflexible and relentlessly obdurate”; he charges him with “acts of corruption, insults, rapine, outrages upon the people, arrogance, repeated murders of innocent victims and constant and most galling savagery.” Pilate was a protégé of Sejanus, a virulent anti-Semite, who was, for a period before his fall, all-powerful at Rome. Pilate, probably early in his period in office, marched his army up to Jerusalem and quartered them there for the winter, standards and all. To carry the imperial insignia into the Holy City was a grave and seemingly deliberate offence to the Jews, and the previous procurators had avoided causing this. The episode as told by Josephus is both fascinating and frustrating. Pilate returned to Caesarea. Josephus records no violence in Jerusalem, but a massive nonviolent protest from Jerusalem to Caesaria, sixty miles away, and an orderly demonstration there for six days, not giving way to threats of violence, constant till Pilate withdrew the standards. These events must have taken place no more than two years before the beginning of Jesus’ ministry.

Great Expectations & the ‘Suffering Servant’ in the Gospels:

The expectation that Jesus might be the Messiah runs through the Gospel story, most strongly in the Fourth Gospel (John). John the Baptist refused the title for himself: another is the true Messiah. Andrew, initially one of John’s disciples, goes to Peter with the words “We have found the Messiah”. A woman from Samaria asks, “Can this be the Messiah?” The people try to proclaim him king: they are talking about him as the Messiah. In the other Gospels his leading follower, Simon Peter, openly calls him the Messiah and is praised for his inspiration. Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem is a messianic entry, according to Zechariah’s prophecy, though not in the military-style expected. He was executed on Pilate’s orders as ‘King of the Jews’, to the extreme annoyance of the Sanhedrin, and taunted with being Messiah. No doubt some of his disciples joined him with that expectation in mind and heart. Simon the Zealot, a name which identified him as a ‘freedom fighter’, perhaps Judas Iscariot, a name which identified him with a southern Zealot centre, Kerioth, and/or the Latin word Sicarius meaning ‘dagger-man’ and even Simon Peter himself, who bore the contemporary Accadian nickname of a revolutionary, Bar-Jonah (Mt. 16: 17). We know that he carried a sword (Jn. 18: 10), which he used during the arrest of Jesus, cutting off the ear of the High Priest’s servant. James and John, known as sons of thunder, may also have been men of violence (Mk. 10: 37; Lk. 9: 54). But Jesus did not behave like a military Messiah. In the wilderness, he was tempted to possess the kingdoms of the world, to gain political power by military means, a temptation which Jesus resisted. The kingdom which he proclaimed was not a new political state but the omnipresent sovereignty of God. He rejected the violent policies of the liberation movement and, if he drew some of them to him in the hope of him leading a national uprising, he also drew at least one hated collaborator, a tax collector.

No Zealot would have have numbered a known collaborator among his followers, nor would he have healed a Roman soldier (Mk. 2: 15; Mt. 9: 9-13; 10: 3; . No Zealot would have laid hands upon a Roman soldier or commended his faith (Mt. 8: 5-13) or told his followers to ‘love your enemies’, specifically referring to the Roman Army (Mt. 5: 38-48). And no Zealot would admit that anything was due to Caesar. Jesus took five thousand men into the countryside; it looked like the beginning of a military operation, but he gave them a lesson in practical community. Writing in the early 1960s, Hugh Montefiore suggested that the ‘feeding of the five thousand’ was a meeting at which the Zealots wanted “to initiate a revolt” with Jesus as their symbolic leader. To him, the arrangement of the men into rows of fifty suggested: “not so much catering convenience as a military operation”. It in association with this event that John records the attempt to make Jesus a king. Jesus evaded this and dismissed the people, thus resisting “a deliberate attempt to make him into a political and military Messiah”. Ferguson argued, however, that Jesus was ‘demonstrating a politics based on peace not war, a politics of sharing and mutual concern.’ His possible Messiahship naturally raised expectations among the Zealots, whose movement was one of military resistance.

When Peter proclaimed him as the Messiah, Jesus taught that he would suffer, and when Peter protested, Jesus called him Satan. Jesus seems to have been the first person to identify himself with the servant who suffers, depicted in Isaiah. His prophecies of the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple were deeply shocking. He could see that the violent uprising on which his people were set would only lead to still more violent suppression. At the same time, he proclaimed a messianic hope which was not centred on Jerusalem and the Temple. In Gethsemane, when arrested, he refused armed support and declared, “All those who take the sword shall perish by the sword”. Jesus allowed himself to be executed and conquered death through his suffering and resurrection. It is clear that he was executed for a political offence. In John’s Gospel, the initial arrest is undertaken by a Roman Guard (Jn. 18: 23). Crucifixion was a Roman punishment; the Jewish equivalent was stoning (Acts 7: 57). In laying the cross upon his followers (Mk. 8: 34), Jesus was foreseeing that the way he was electing to tread was a way which the Roman authorities might regard as rebellious. T. W. Manson observes that Jesus is aware of an irreconcilable hostility between the kingdom for which he stands and the Empire represented by Pontius Pilate. This makes further nonsense of the suggestion that Jesus was apolitical.

Jesus was profoundly and relevantly political. He was executed as ‘King of the Jews’ (Mk. 15: 2; 15: 18; 15: 26) and not for ‘blasphemy’ under Jewish Law, for which he would have been stoned. Gamaliel put him in the same category as Judas and Theudas (Acts 5: 36-37). The curious story of Barabbas raises historical problems, since there is no other record of the unlikely practice of releasing a prisoner at the festival, but the sub-plot does reinforce the the element of choice. Barabbas was a violent insurrectionist (Mk. 15: 7; Jn. 18: 40). It is the contrast between the man of violence and the man of nonviolent love, both arrested for political activity subversive to the status quo, which fits into the overall narrative. It is clear from the Gospel and the letters of Paul that Christian love is not an ideal aspiration but a practical path through a world of violence and evil; that its ultimate ‘weapon’ is suffering; and that it has to do with political and communal relationships and not just with personal encounters. In telling his followers to “love your enemies”, Jesus is speaking not of the Jewish dispensation to hate a personal enemy, but of their relationship with the Roman occupiers. This did not mean that Jesus did not view himself as a ‘liberator’ however, in the mainstream Messianic tradition. That was the characteristic of the Messiah that he expounded on the walk to Emmaus when he ultimately revealed himself to be “the man to liberate Israel” (Luke 24: 21; 24: 26).

Jesus’ Five Calls to Community & Commonwealth:

Jesus’ Messiahship is different; it is a call to the people. Ferguson picks out five ‘calls’ that he makes upon his followers. First, he calls them as a people to national repentance, to choose another way (Mk. 1: 15). Second, he calls for social justice, for community and commonwealth, for mutual concern and sharing. Thirdly, the path of his Messiahship is one of peace, not war. Peace is both a means and an end. This is most evident in his first entry into Jerusalem, fulfilling not the military prophecies but the peaceable prophecy of Zechariah. In Luke, the crowds actually raise the cry of peace (19: 38). In John, the contrast between the way of Jesus and the way of the Zealots, when he quotes: “These were all thieves and robbers”, referring not to prophets but to the Zealots, who led their deluded followers ‘like sheep to the slaughter’. Jesus, however, was the true shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep (Jn. 10: 8; 10: 11). This was the issue between ‘Jesus called Messiah’ and ‘Jesus called Bar-Abbas’ (Mt. 27: 16-17). Fourth, Jesus associates the Messiah with the Suffering and issues a summons to suffering. He invites his disciples to be a suffering community; I do not doubt that he would have wished Israel to be that suffering community but saw that neither the appeasers nor the Zealots would take that path. Finally, there is some indication that Jesus’s answer to the nationalist rejection of Rome and the Romans was an extension of the Gospel to Rome and the Romans, the Greeks, and other ‘gentiles’. Immediately after his temptation, Jesus heard of John’s arrest and went home to Galilee, according to Matthew:

… leaving Nazareth, he went and settled at Capernaum on the Sea of Galilee, in the district of Zebulun and Naphtali. This was to fulfil the passage in the prophet Isaiah which tells of … ‘the way of the Sea, the land beyond Jordan, heathen Galilee’, and says:

“The people that lived in darkness saw a great light; light dawned on the dwellers of the land of death’s dark shadow.“

From that day Jesus began to proclaim the message: ‘The kingdom of Heaven is upon you.’

Mt. 4: 12-17.

According to this version, therefore, his first preaching was in the Greek area and to Gentile Galilee, not just to the Jews. In this context, we may also consider his contact with many different Gentiles, Canaanites and Samaritans, and his contact with Philip’s Greek friends in Jerusalem, when he told them:

In truth, in very truth I tell you, a grain of wheat remains a solitary grain unless it falls into the ground and dies; but if it dies, it bears a rich harvest.

Jn. 12: 20-33

This implies the spread of the kingdom among the Gentiles through the power released by his death. At the crucifixion, it was a man from Africa who carried the cross and who evidently became a Christian as a result since his sons were well-known in the church (Mk. 15: 21) and that a Roman centurion at the moment of Jesus’s death saw through his bodily frailty to his divine power (Mk. 15: 39). In other words, Jesus offered an alternative policy to that of the Zealots. Part of this lay in his certainty that love is the channel of God’s redemptive power. With hindsight, this was what led to the conversion of the Romans and the defeat of the Roman Empire from within. Jesus did not acquiesce to Roman rule in Palestine, or he would not have been crucified.

According to another story about Pilate in Philo’s writings, which sheds light on his motivation for convicting and sentencing Jesus, Pilate set up some golden shield in Herod’s old palace in Jerusalem. These bore no offensive portraits or emblems, but they were inscribed with a dedication to the emperor. A delegation of Jews, presumably from the Sanhedrin, asked Pilate to remove them. When he refused to do so, they pleaded with him not to cause a revolt or breach of the peace. They threatened to appeal to the emperor which greatly upset Pilate and when they went ahead with it, the emperor wrote to Pilate ordering him to change policy. These events must have taken place after the fall of Sejanus when Tiberius was again concerning himself personally with government. At this time, Sejanus’ appointees were subject to a purge in Rome since Sejanus himself had been condemned for high treason and they were therefore all under suspicion. If these events were before the crucifixion, the threat to Pilate from the Sanhedrin was repeated in the words, “if you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar” (John 19: 12). The first charge by them against Pilate had been answered by a severe rebuke; a second could be fatal. A third clash concerned the building of an aqueduct for Jerusalem. This was, of course, an important benefit of ‘Roman Civilisation’, but controversy developed around Pilate’s proposal to pay for it from the Temple treasury. The reaction was violent and there was sabotage of the work and offensive behaviour shown to Pilate himself. He avoided a head-on confrontation with his troops but had armed agents in disguise moving among the protesting crowds, and on a signal using clubs to beat them up and disperse them.

Other disturbances form a shadowy background to the Gospels. There were Galileans ‘whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices’ (Luke 13: 1). We have no other evidence about this event or events, but the term ‘Galilean’, as noted, seems to have been synonymous for some with ‘Zealot’. It seems likely that Pilate’s action was a requital of violence with violence, and it also seems that Jesus answered by repudiating the approach of the Zealots: When he used the word ‘repent’ he meant ‘find a better policy’. There was an attempted uprising in Judaea at some point in the period before the crucifixion (Mk. 15: 7) in which Barabbas was captured, together with the ‘lesser’ brigands who were crucified with Jesus (Mk. 15: 27), which reveals something of the atmosphere into which Jesus chose to come, when he entered into Jerusalem at Passover. It was impossible for him to be apolitical. This was an atmosphere in which “He who is not for me is against me” (Mt. 12: 30), and “he who is not against us is on our side” (Mk. 9: 40). Neutrality was not an option. In his account of Jesus’ second entry into Jerusalem, for the Passover festival (the first is now believed to have taken place during ‘the feast of Tabernacles’ the previous autumn), Luke relates some important words of Jesus:

When he came in sight of the city, he wept over it and said,

“If only you had known, on this great day, the way that leads to peace! But no; it is hidden from your sight. For a time will come upon you, when your enemies will set up siegeworks against you; they will encircle you and and hem you in at every point; they will bring you to the ground, you and your children within your walls, and not leave you one stone upon another, because you did not recognise God’s moment when it came.”

Luke 19: 41-44

Many scholars think that this passage ‘foreseeing’ the destruction of Jerusalem is coloured by the Gospel writer’s knowledge of the siege of Jerusalem by Titus in A.D. 70, and was therefore written with the benefit of hindsight. But Ferguson points out that the language is very general, and that anyone writing with hindsight would have included far more graphic detail in Jesus’ prophecy. Cool political realism without any supernatural insight could have made the judgement of the outcome of the Zealot’s policies. Matthew too records Jesus agonising over the fate of Jerusalem (Mt. 23: 37). The apocalyptic discourse in Matthew also foretells the overthrow of the Temple, borrowing from Mark (13: 1-2), and few would now claim that Mark was written after A.D. 70. Either way, Jesus’ message, one which was reiterated by the late-first-century ‘church’ was clearly that there was a clear choice to be made between Jesus’ way of peace, and the violent resistance of the Zealots, the way of destruction. In the light of all this, Jesus’ prophecies of the fall of Jerusalem must have been deeply shocking for his Jewish followers to hear. They were completely alien to the Messianic role as conceived by most of his contemporaries, including many of his own disciples. They were tantamount to saying that the Messianic kingdom would not be centred on Jerusalem.

Jesus had a wider hope, and it is just at this point that the story of the Canaanite (Syro-Phoenician) woman who came to Jesus as he travelled along the coast is so important (Mark 15: 21-28). She addresses him by the Messianic title, “Son of David” and asks him to heal her daughter. The disciples try to send her away. If the words that Jesus uttered next were meant to be taken at face value, he would never have spoken them; he would simply have allowed his followers to hustle her off. He says, “I was sent to the lost sheep of the house of Israel, and to them alone.” This is the traditional Messianic function. The woman makes a quick and witty reply, and Jesus commends her faith and heals her daughter. It is the final outcome that matters. We might assume that either Jesus is revealing his human limitations, having had a limited view of the Messiahship, and this was a moment of illumination for him, or that all along he had held a wider view and was testing the woman. His silence is significant: he keeps a similar silence when confronted with the woman taken in adultery (John 8: 6); it suggests a sympathy with the woman and a rebuke to her opponents. John Ferguson suggests that Jesus saw, or came to see, the Messianic kingdom as the establishment of a new Israel which knows no national boundaries and not as a restoration of a physical Israel centred on Jerusalem. The third aspect of the Messianic kingdom is that it offered social justice, sustained with peace and righteousness, as Isaiah had attested (9: 7; 11: 4). Psalm 72 also speaks to this:

O God, endow the king with thy own justice,

and give thy righteousness to a king’s own son,

that he may judge the people rightly

and deal out justice to the poor and suffering.

72: 1-2.

May he have pity on the needy and the poor,

deliver the poor from death;

may he redeem them from oppression and violence

and may their blood be precious in his eyes.

72: 13-14.

In the seventeenth of The Psalms of Solomon, the keynotes of the Messiah’s reign are wisdom, righteousness and equity. Philo also looks forward to material prosperity, long life, large families, physical health, peace, and security from wild animals. Here too was something which Jesus saw as central to his own ministry. This is why he went to the synagogue at Nazareth and read the passage from Isaiah (61: 1-2) referring to the year of the Lord’s favour. This refers to the ‘Year of Jubilee’ when the land was supposed to be redistributed equitably (Lev. 25: 8 ff). In this, we see that the Messianic hope was political and that Jesus accepted that challenge when he said “Today in your very hearing this text has become true” (Luke 4: 21). Jesus was concerned with creating a new community, and when that began to appear one of their early concerns was economic sharing, for koinonia, for ‘community’ (Acts 4: 31-32). The new communities which sprang up after his death and resurrection were therefore the practical, collective fulfillment of the Jubilee promise of the Old Testament. In them, ‘sharing’ was not an individual choice or attitude, but a matter of communal obligation. This was, and still is, what makes the Messiah’s message so radical and controversial, if read correctly, and why it cannot be divorced from politics.

The Biography of the Holy Spirit & Birthday of the Church:

The Acts of the Apostles has been called without extravagance the biography of the Holy Spirit. From Pentecost, often referred to as ‘the birthday of the church’, its actions dominate every page. It seizes dramatically all those who receive it, and even the buildings are shaken by its power (Act 4: 31). The people cry out in ecstasy and speak in strange tongues (Acts 2: 4). Peter speaks of Jesus as receiving the Holy Spirit from the Father and making the gift of it to all who turn to him (Acts 2: 33-39). The Spirit gives courage (Acts 4: 31) and manifests itself in the quality of life of individuals (Acts 11: 23). From the Spirit comes the disciples’ power to speak and their healing power (Acts 4: 31; Acts 3; 1-10). It enables Stephen to see the glory of God (Acts 7: 55) and directs Philip to the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8: 29). Later, it guides the counsels and corporate decisions of the churches (Acts 15: 28). This is therefore no ‘ghost’, haunting an individual body, but a power or force which acts in the whole life of the nascent and disparate communities and their members. The same pattern runs through Paul’s letters. The Holy Spirit dwells in the Christian (Rom. 8: 9; I Cor. 6: 19; Eph. 2: 28). It shows us hidden truths, guides our understanding, tells us what to say (I Cor. 2: 6-16); it overcomes our lower nature and guides our conduct (Rom. 8: 4). The ‘fruits’ of the Spirit are “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control” (Gal. 5: 22). The Spirit is spoken of variously but indifferently as the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Christ, the Spirit of Jesus and the Spirit of the Lord (Acts 16: 8, Phil. 1: 19, II Cor. 3: 17). Again, it can work through bot individuals and communities:

In the same way, only the Spirit of God knows what God is. This is the Spirit that we have received from God … A man gifted with the Spirit can judge the worth of everything … We … possess the mind of Christ.

I Cor. 2: 11-16.

The first-century followers of ‘The Way’ went out to make all nations disciples of Jesus (Mt. 28: 19). Paul was a great missionary to the Gentiles, but he was not the only one. Peter began (Acts 10), then drew back (Gal. 2: 12), but was eventually crucified in Rome. Philip reached out to the Ethiopian ‘eunuch’ (Acts 8: 26-31). Tradition has it that Thomas went to India. The missionaries within the Roman empire were not interested in fomenting a military revolt against Rome; they aimed to transform Rome from within. But their commitment to Jesus’s radical agenda and ‘Way’ led them into conflict with the authorities in which the latter responded with customary violence. The followers of ‘the Way’, one of the earliest names for the Christian movement or ‘church’, met this with unflinching courage, and the blood of these early ‘Christians’ became the seed of the Church. But for now, they continued to act as a branch of Judaism, albeit a fresh offshoot, and were treated as such by the Romans. There is some evidence that they were mistakenly associated with the Zealots and other revolutionary Judaistic sects which were partly responsible for the indiscriminate persecution of the Judaeo-Christian communities. God’s plan had always been to unite all things in heaven and on earth in Jesus, which meant, from the Jewish point of view, that Jesus was the ultimate Temple, the ‘heaven-and-earth place’. This, already accomplished in his person, was now being implemented through his Spirit.

Paul always believed that God’s new creation was coming, perhaps soon, and that the corrupt and decaying world in which he lived would one day be rescued from this state of ‘slavery’ and death and emerge into new life under the glorious rule of God’s people, God’s new humanity – this he never doubted. Paul was therefore determined to establish and maintain ‘Jew-plus-Gentile’ communities and insisted on the unity of the church across all traditional boundaries. This was not about the establishment of a new “religion” and neither did it have anything to do with Paul being a “self-hating Jew”, a slur that is still repeated by anti-Semites today. Paul affirmed what he took to be the central principles of ‘the Jewish hope: One God, Israel’s Messiah, and resurrection itself. For him, what mattered was messianic eschatology and the community that embodied it. The One God had fulfilled not only a set of individual promises but the entire narrative of the ancient people of God. It was because of that fulfilment that the Gentiles were now being brought into the single-family. The Roman commander who arrested Paul outside the Temple in Jerusalem during his visit to perform the ceremony of purification, expected him to be a Zealot (Acts 21: 38). The commander allowed him to speak to the crowd who were angry with him for taking, as they assumed, a Gentile from Ephesus into the Temple. They had been stirred up by some Jews from Asia Minor who claimed that Paul had been going everywhere teaching everyone against the people of Israel, the Law of Moses, and the Temple. Paul addressed them in Hebrew from the steps of the Temple:

“I am a Jew, born in Tarsus of Cilicia, but brought up here in Jerusalem as a student of Gamaliel. I received strict instruction in the Law of our ancestors and was just as dedicated to God as you who are here today. I persecuted to death the people who followed this Way. I arrested men and women and threw them into prison. The High Priest and the whole Council can prove that I am telling the truth. …”

Acts 22: 1-5

Paul’s mission to the gentiles was not different from the idea of ‘forgiveness of sins’, but he was powerfully motivated by the belief that the old barriers between Jew and Gentile were abolished through the Messiah, in whom the promises of Psalm two had come true, that God would set his anointed king over the rulers of the nations, thus extending into every corner of the world the promises made to Abraham about his ‘inheritance’ – that Paul could summon every kind of background to “believing obedience.” That is why Paul’s work must be regarded just as much ‘social’ or ‘political’ as it is ‘theological’ or ‘religious.’ Every time he expounded ‘justification,’ it formed part of Paul’s argument that in the Messiah there was a single-family composed of believing Jews and Gentiles. This was a family that demonstrated to the world that there was a new way of being human. Paul saw himself as a working model of exactly this: Through the law, I died to the law, so that I might live to God. Paul took the stance he now did neither because he was some kind of ‘liberal’ Jew, nor because he was making pragmatic compromises to try to lure Gentiles into his communities, nor because he secretly hated his own culture and identity. He took his stance because of the Messiah who had radically transcended and transformed his life:

I have been crucified with the Messiah. I am, however, alive – but it isn’t me any longer; it’s the Messiah who lives in me.

Gal. 2: 19-20

(to be continued…)

Sources:

John Ferguson (1973), The Politics of Love: The New Testament and Non-Violent Revolution. Cambridge: James Clarke (in association with The Fellowship of Reconciliation).

John Ferguson (1977), War and Peace in the World’s Religions. London: Sheldon Press.

Robert C. Walton (ed.) (1970), A Source Book of the Bible for Teachers. London: SCM Press.

Alan T. Dale ( 1979), Portrait of Jesus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tom Wight (2018), Paul: A Biography. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

John Barton (2019), A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths. London: Allen Lane.