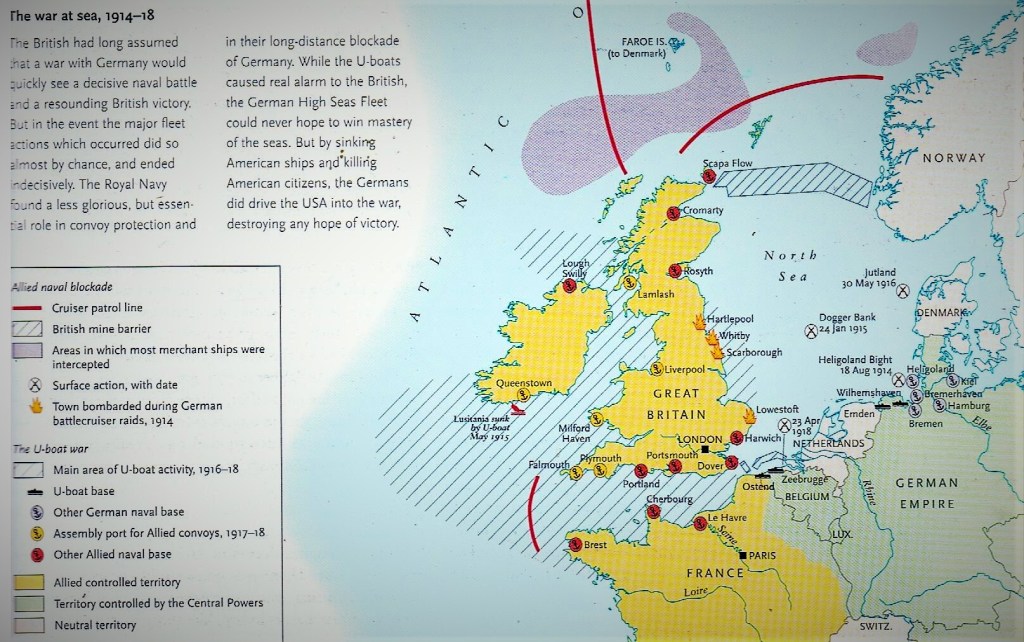

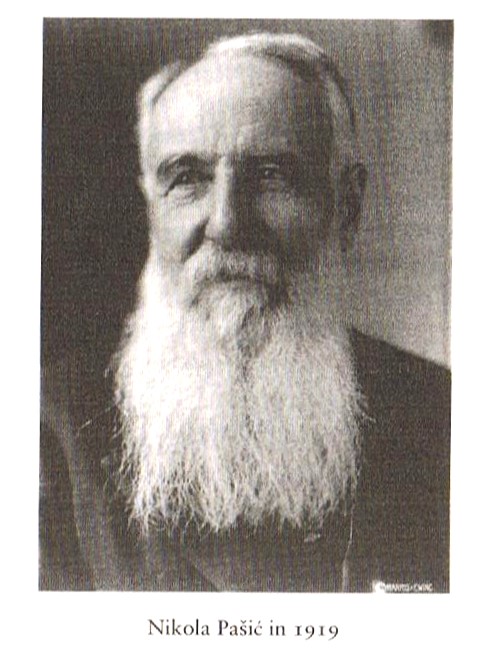

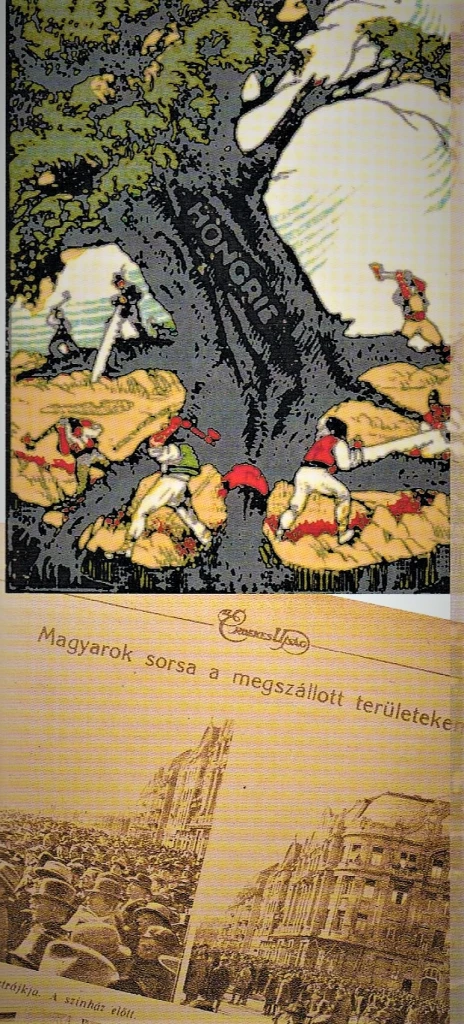

Chapter Three – From Sarajevo to War & Revolutions, 1914-1919:

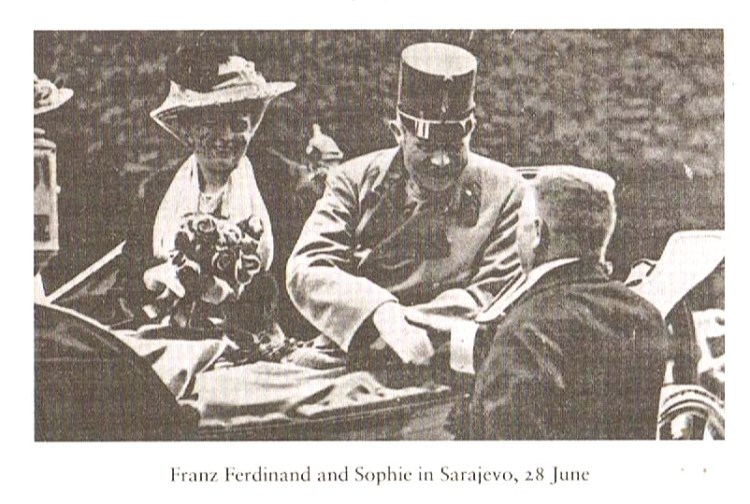

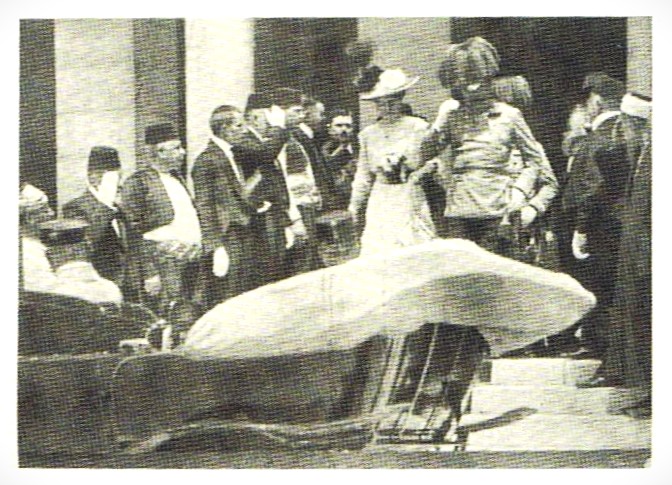

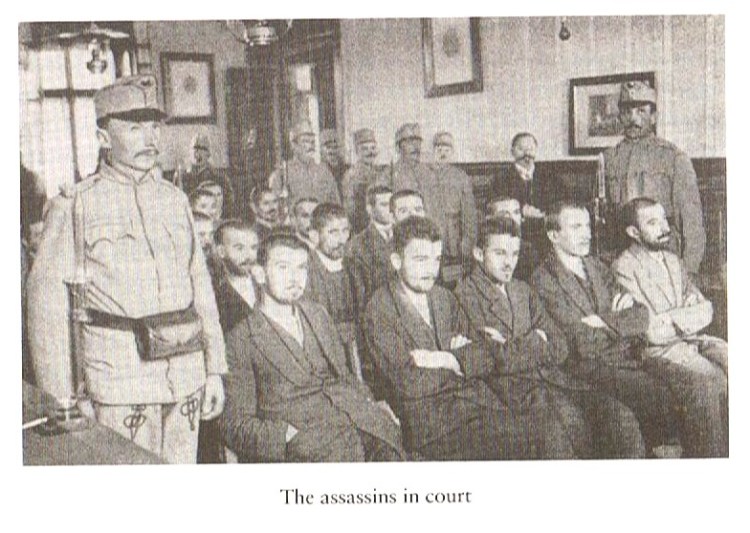

Archduke Franz Ferdinand favoured a policy of reconciliation with the Slavs in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. Because of this attitude, he was disliked both by the traditional ruling élite in Vienna and the Magyar bourgeois statesmen of Hungary. The Slavs within the empire, seeking union with the Serbs, also opposed him. Nevertheless, the Austrian government seized the opportunity of his assassination to charge the Serbian Government with complicity.

Ultimatums & Mobilisations:

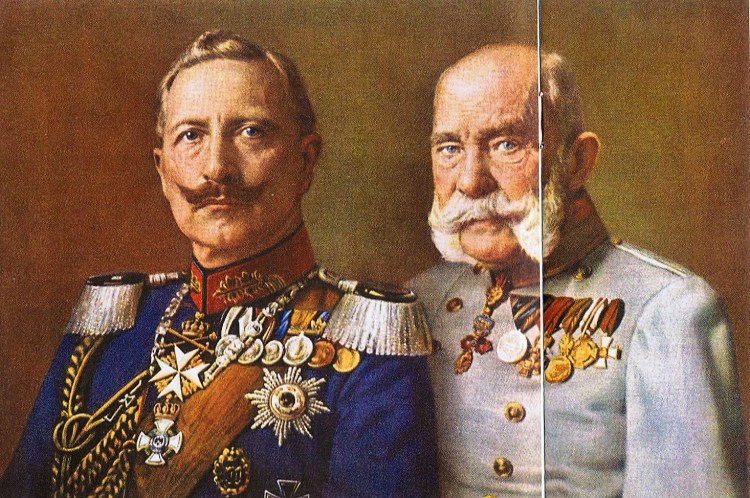

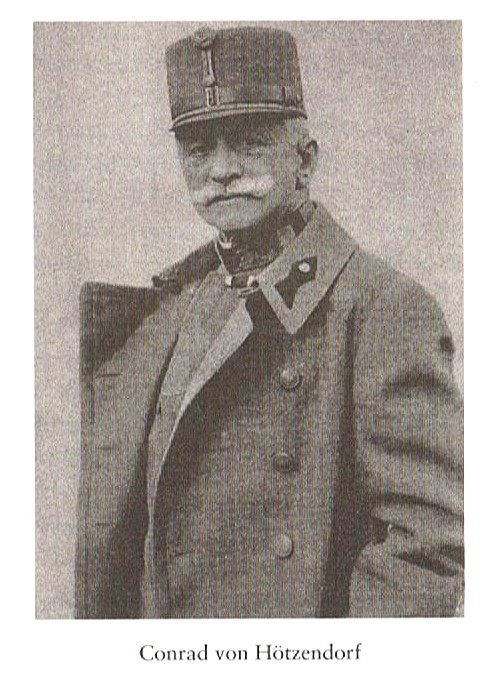

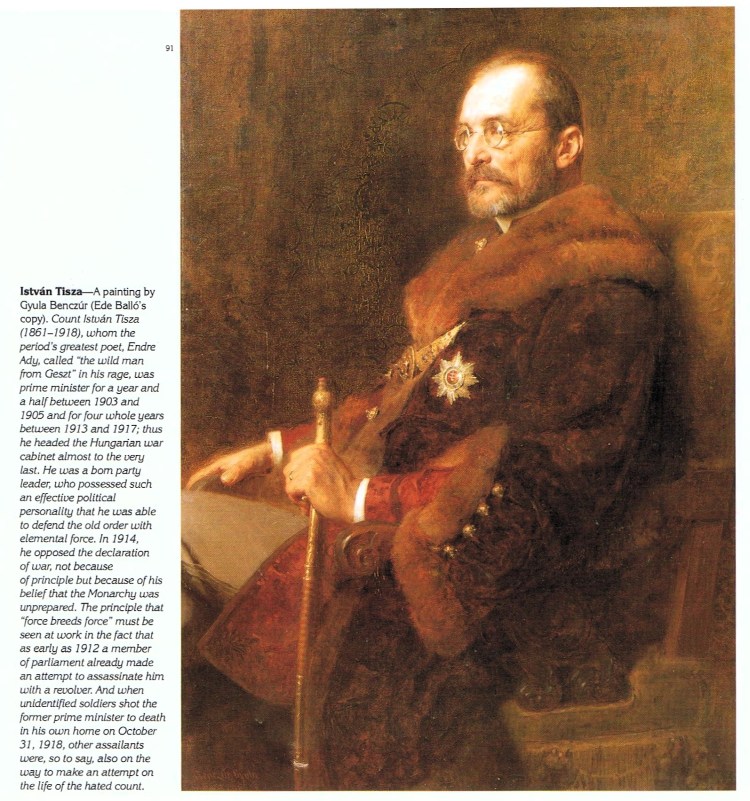

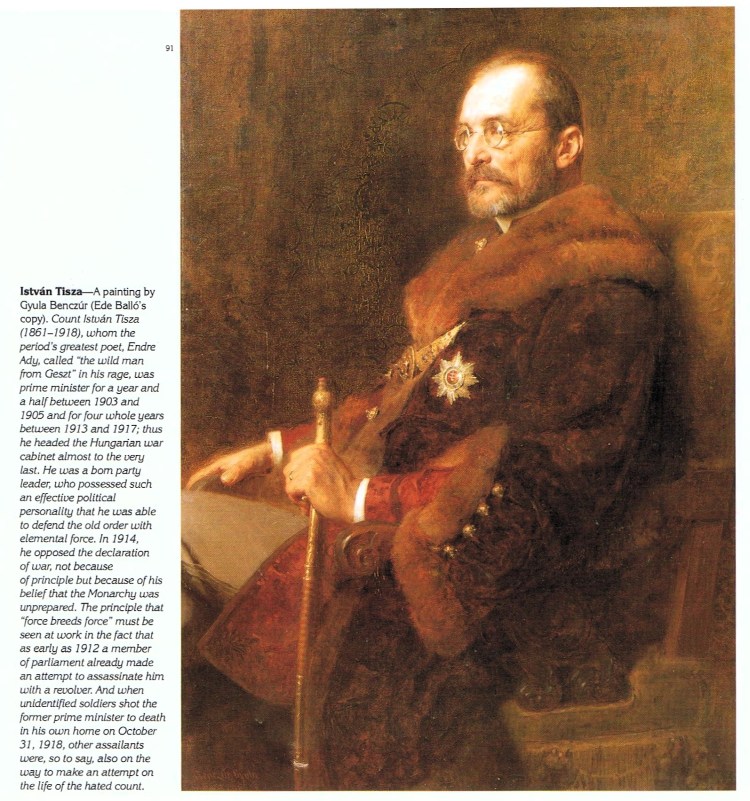

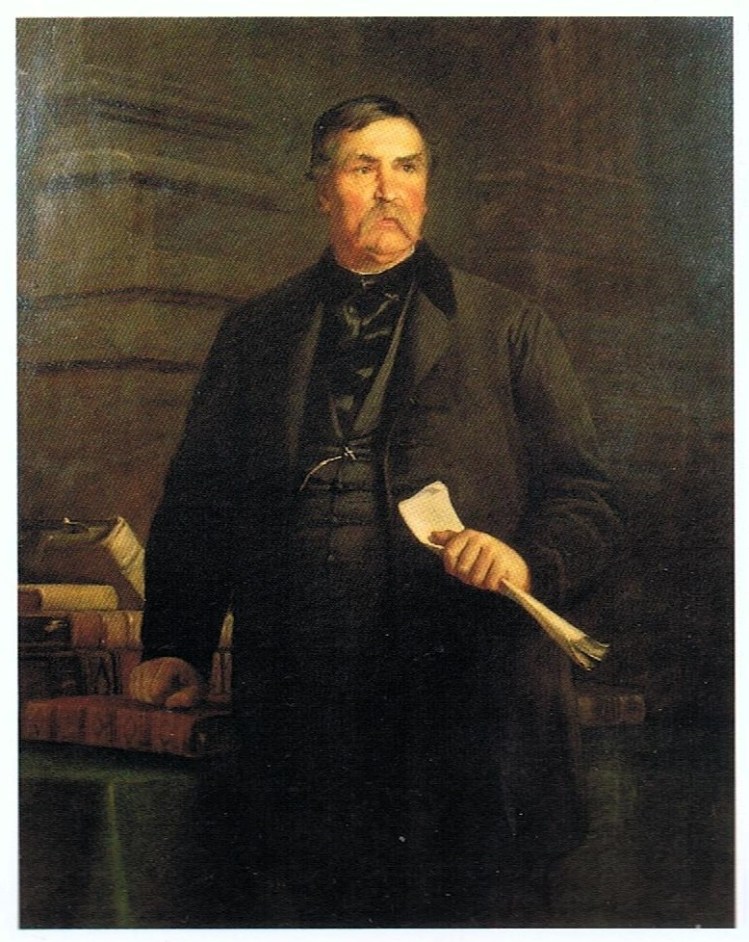

In Viennese political and military circles, the assassination of Franz Ferdinand was mostly seen as a golden opportunity to settle old scores with Serbia and not to re-establish the prestige of the Monarchy. In Berlin, Kaiser Wilhelm II and his generals thought that since an armed confrontation between the Central Powers and the Entente was inevitable, it was better to fight it before Germany’s hard-won advantage in the armament race was completely diminished. They brought pressure on the Common Council of Ministers, especially Tisza, the Hungarian premier, who was worried both by the prospect of a Romanian attack and therefore by the plan for the annexations in the Balkans and elsewhere, urged by the bellicose Austrian Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf and several political leaders both in Vienna and Budapest.

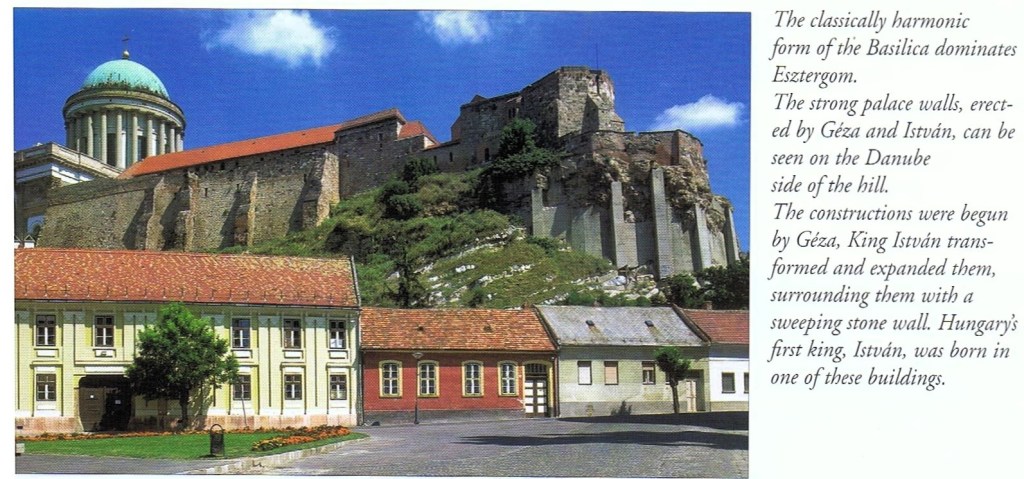

By mid-July 1914, a decision of sorts had been made about whether or not Austria-Hungary was going to war: the Austro-Hungarians, or at least the grouping around Berchtold, intended to seek a military resolution of their conflict with Serbia. Yet on all other issues, the policy-makers in Vienna had, as yet, failed to deliver coherent positions. There was still no agreement at the time Count Alexander Hoyos (Berchtold’s chef de cabinet) left for Berlin, on what policy should be pursued in Serbia after an Austrian victory. When he was asked there about Austria-Hungary’s post-war objectives, he responded with a bizarre improvisation: Serbia, he declared, would be partitioned between Austria, Bulgaria, and Romania. In reality, he had no authority to propose such a course of action, and no plan for partition had been agreed upon by his Austrian colleagues. He later explained that he had invented the policy because he feared that the Germans would lose faith in the Austro-Hungarians if they felt ‘that we could not formulate our Serbian policy precisely and had unclear objectives.’ (A. Hoyos, Meine Mission nach Berlin, in Fellner, Die Mission ‘Hoyos’, p.137. ) István Tisza, the Hungarian premier, was furious when he learned of Hoyos’s indiscretion; the Hungarians, even more than the political élite in Vienna, regarded the prospect of yet more angry South Slav Habsburg subjects with unalloyed horror. Vienna subsequently made it clear that no annexation of Serbian territory was intended. But Hoyos’s gaffe conveyed something of the chaotic way in which Austrian policy evolved during the crisis.

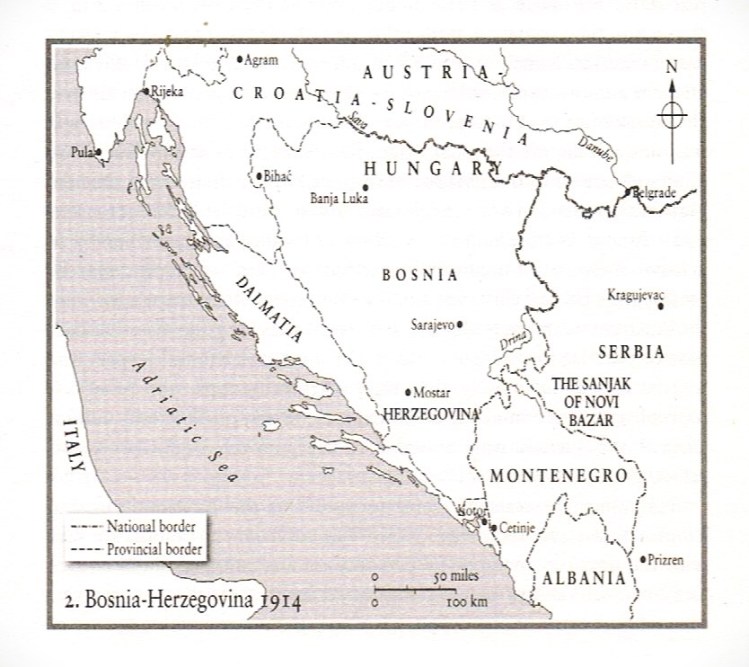

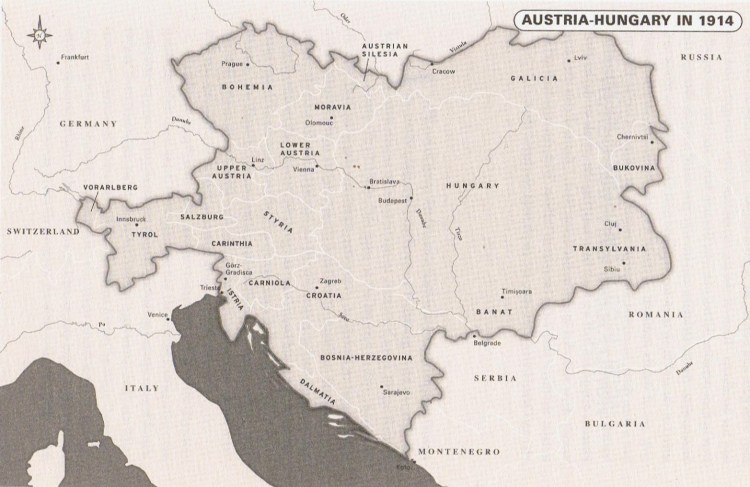

To alleviate the problem of the rural areas of the Habsburg lands, where military service in summertime created serious labour shortages at harvest time, the Austrian General Staff had devised a system of harvest ‘exeats’ that allowed men to return to their family farms to help with crops and then rejoin their units in time for their summer maneuvers. On 6th July, it was ascertained that troops serving in units at Agram (Zagreb), Graz, Pressburg (Bratislava), Craców, Temesvár, Innsbruck, and Budapest were currently on harvest leave and would not be returning to service until 25th July. It soon became clear, however, that it would be some time before military action could begin.

On 7th July, following Hoyos’s return from Berlin, it became clear that there was still no agreement among the principal decision-makers about how to proceed. Berchtold opened the Joint Ministerial Council by reminding his colleagues that Bosnia and Hercegovina would only be stabilised if the external threat from Belgrade was dealt with. If no action were taken, the monarchy’s ability to deal with the Russian-sponsored irredentist movements in its southern Slav and Romanian areas would steadily deteriorate. This was an argument calculated to appeal to Count Tisza, for whom the stability of Transylvania was a central concern. Tisza was not convinced, however, and in his reply to Berchtold, he conceded that the attitude of the Serbian press and the results of the police investigation in Sarajevo strengthened the case for a military strike. But first, he asserted, the diplomatic options needed to be exhausted.

There was general agreement that Belgrade had to be presented with an ultimatum, whose stipulations had to be firm, but not unfulfillable. Sufficient forces had to be made available to secure Transylvania against an opportunistic attack by Romania. Then Vienna would have to consolidate its position among the Balkan Powers: Vienna needed to seek closer relations with Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire, in the hope of creating a Balkan counterweight to Serbia and ‘forcing Romania to return to the Triple Alliance’. (‘Protocol of the Ministerial Council for Joint Affairs convened on 7 July 1914.’) There was nothing in this to surprise anyone around the table. This was also the familiar view from Budapest, in which Transylvania occupied centre stage. But Tisza faced a solid bloc of colleagues determined to confront Serbia with demands they expected Belgrade to reject.

The Austrian ministers knew that a purely diplomatic success would have no value at all since it would be read as a sign of Vienna’s weakness and irresolution in Belgrade, Bucharest, St Petersburg, and the southern Slav areas of the monarchy. Time was running out for Austria-Hungary as with each passing year, the monarchy’s security position on the Balkan peninsula became increasingly fragile. The ministers agreed to accept Count Tisza’s suggestion that mobilisation against Serbia should occur only after Belgrade had been confronted with an ultimatum. But all of the ministers except Tisza believed that a diplomatic success, even one involving a ‘sensational humiliation’ of Serbia, would be worthless and that the ultimatum must therefore be framed in terms harsh enough to ensure a rejection, ‘so that the way is open to a radical solution by means of military intervention.’ This discussion and decision marked a watershed, washing away any chance of a peaceful outcome. Yet there was still no sign of precipitate action. The option of an immediate surprise attack without a declaration of war was rejected. Tisza, whose agreement was constitutionally necessary for a resolution of such importance, continued to insist that Serbia should first be humiliated diplomatically. Only after a further week did he give way to the majority view, mainly because he became convinced that failure to address the Serbian question would have an unsettling effect on Hungarian Transylvania.

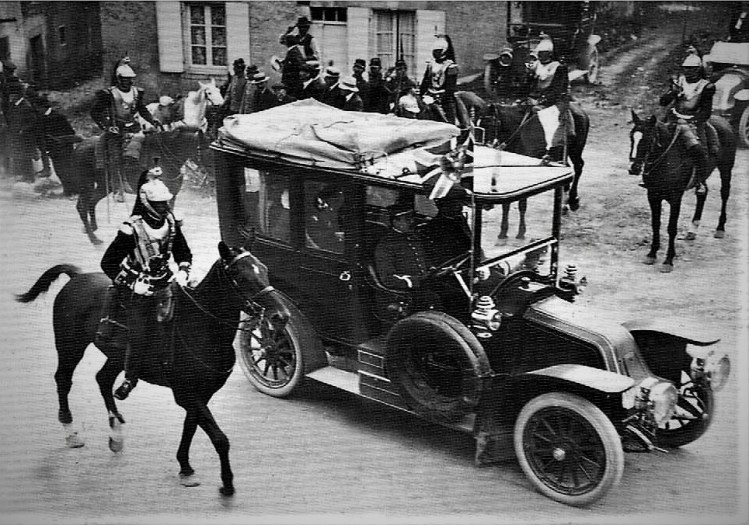

Without positive knowledge of Serbian complicity in the Sarajevo assassination, a harsh ultimatum demanding, among other things, an official denunciation of the movement for Greater Serbia and the free involvement of Austro-Hungarian agents in investigating the case on Serbian territory, was dispatched to Belgrade on 23rd July. It soon turned out that the great powers of the opposite camp were also not anti-war. Serbia rejected the ultimatum two days later not on grounds of innocence, but because it was prompted to do so by her Entente supporters. Within two weeks of the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war on Serbia on 28th July, allied obligations combining nationalist and imperialist dreams involved nearly the whole of the European continent, and significant regions of the world, in war.

In the meantime, a measure of unanimity was achieved in Vienna over the course of action to be followed. At a further summit meeting in the city on 14th July, it was agreed that a draft of the ultimatum would be checked and approved by the Council of Ministers on the 19th and the ultimatum would be presented to the Belgrade government only on 23rd July. This date was chosen to avoid a state visit by President Poincaré to St Petersburg in the days before, Berchtold and Tisza agreeing,

‘… that the sending of an ultimatum during this meeting in St Petersburg would be viewed as an affront and that personal discussion between the ambitious President of the Republic and His Majesty the Emperor of Russia… would heighten the likelihood of a military intervention by Russia and France‘.

(Berchtold’s Report to the Emperor, 14 July 1914).

From this moment onwards, secrecy was of the greatest possible importance, both for strategic and diplomatic reasons. It was essential for the Austro-Hungarians to avoid any action that might give the Serbs prior notice of their intentions and thereby give them time to steal a march on the Monarchy’s armies. Recent appraisals of Serbian military strength suggested that the Serbian army would not be a trivial opponent. Secrecy was also essential because it presented Vienna’s only hope of conveying its demands to Belgrade before the Entente powers had the opportunity for joint deliberations on how to respond. Berchtold therefore ordered that the press be firmly instructed to avoid the subject of Serbia. In its official relations with Russia, the Austro-Hungarians went out of their way to avoid even the slightest friction; Szapáry, their ambassador to St Petersburg, was particularly assiduous in his efforts to tranquilise the Russian foreign ministry with assurances that all would be well.

Yet these efforts attempted to disguise the many oddities involved in the Austro-Hungarian decision-making process. Berchtold, disparaged by many of the ‘hawks’ in his administration as a soft touch, incapable of forming clear resolutions, took control of the policy debate after 28th June in a quite impressive way. But he could only do this through an arduous, painstaking, and time-consuming consensus-building process. The puzzling dissonances in the documents that track the formulation of the Austro-Hungarian position to go to war reflect the need to incorporate opposing viewpoints. The momentous possibility of the decision leading to a Russian general mobilisation and the general European war that would undoubtedly follow was certainly glimpsed by the Austro-Hungarian decision-makers, who discussed it on several occasions. However, it was never fully integrated into the process by which the options were weighed and assessed. In particular, no sustained attention was given to the question of whether Austria-Hungary was in any position to wage a war with one or more other great powers.

There are several possible reasons for this myopic vision. One was the extraordinary confidence in the strength of German arms, which, it was assumed, was sufficient to deter, and failing that, to defeat Russia. The second was that the hive-like structure of the Austro-Hungarian political élite was simply not conducive to the formulation of decisions through the careful balancing of contradictory information. The contributors to the debate tended to indulge in rhetorical statements, often sharpened by mutual recrimination, rather than attempting to view the diplomatic and military choices facing the Monarchy in the round. These failings reflected the profound sense of isolation in Vienna and Budapest. The notion that the statement of the twin capitals had ‘a responsibility’ to Europe was nonsense, as one political insider noted,

‘Because there is no Europe. Public opinion in Russia and France … will always maintain that we are the guilty ones, even if the Serbs, in the midst of peace, invade us by the thousands one night, armed with bombs’.

Memorandum by Berthold Molden for the press department in Vienna, cited in Solomon Wank, ‘Desperate Counsel in Vienna in July 1914: Berthold Molden’s Unpublished Memorandum’, Central European History, 26/3 (1993), pp. 281-310.

However, the most important reason for the perplexing narrowness of the Austro-Hungarian policy debate is surely that they were so convinced of the rectitude of their case and of their proposed remedy against Serbia that they could conceive of no alternative to it – even Tisza had accepted by 7th July that Belgrade was implicated in the crimes at Sarajevo and was willing in principle to countenance a military response, provided the timing and diplomatic context were right. Nor is it easy to see how the Austro-Hungarians could have made a less drastic solution work, given the reluctance of the Serbian authorities to meet Austrian expectations, the absence of any international legal bodies capable of arbitrating in such cases, and the impossibility in the current international climate of enforcing the future compliance of Belgrade. Yet at the core of the Austro-Hungarian response was a temperamental, intuitive leap, an act of attrition founded on a shared understanding of what the Habsburg Empire had been, was still, and must be in future, if it were to remain a great power.

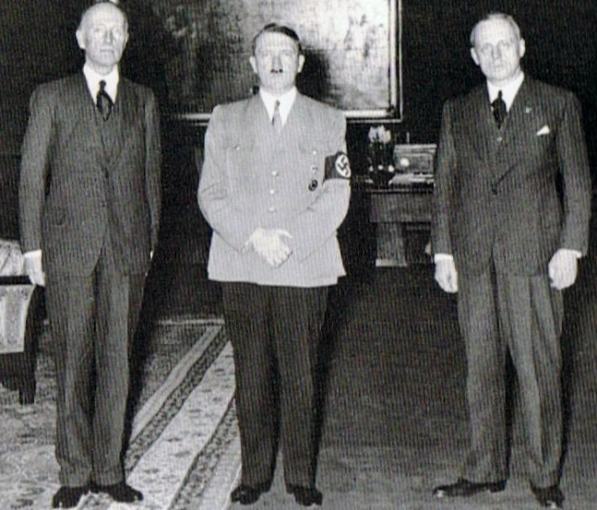

Austria-Hungary presented an ultimatum with demands which threatened the very existence of Serbia as an independent state. The Austrian statesmen believed that war with the Serbs would almost certainly lead to a general European war and that the ruin of the Austrian Empire was inevitable if they were defeated. They decided to take the risk. Emperor Franz Josef first sought and obtained the assurance of support from the Kaiser. Although Serbia accepted almost all of the humiliating demands of the ultimatum, Vienna treated the Serbian reply as a rejection. In the end, Tisza gave way because he knew that ‘Greater Hungary’ had only come about due to Bismarck’s intervention. He told the Belgian Minister, ‘Mon Cher, Allemagne est invincible.’

The Uncontrollable Storm of War:

War with Serbia followed on 28th July, and Budapest had paroxysms of enthusiasm. Even Count Apponyi said in Parliament, ‘At last’; ‘végre’. The Russians did protect Serbia, and Germany went to war, provoking trouble with Russia’s ally France and then giving the British no choice by invading Belgium, the neutrality of which Britain had guaranteed. In the last three days of July, a freak storm hit the microclimate of hilly Buda and the plain of Pest, destroying roofs and smashing the plate-glass windows of the cafés on the Danube embankment and the Oktogon, as the recruits marched towards the mobilisation trains. The now ‘late’ Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s main adviser, Count Czernin, said two things: that minority problems were a bore, and that the only difference in Austria was that they had a peculiarly multifarious collection. The main priority, for him, was to avoid a war. In his post-war memoirs, he also said:

‘We were bound to die, we were at liberty to choose the manner of our death and we chose the most terrible.’

Ottokar Czernin, In the World War (1920), p.38.

As noted previously, in 1867 Kossuth had written an open letter to Deák, warning that, without control of her own foreign policy and without her own army, Hungary would be dragged into Austro-German adventures which were not in her interest. Almost half a century later, it seemed that he had been proved right. Yet at the time he was writing, Austria-Hungary’s relations with a not yet unified Germany seemed a far more equal and positive partnership, and Kossuth’s alternative, a Balkan federation, was unattractive. Since then, Germany had become the most successful country in Europe, overtaking Great Britain and even rivaling the USA. Her education system was widely acknowledged as one of the best in the world. German universities attracted Hungarians in great numbers, including István Tisza, who studied Law at Heidelberg. Hungary now belonged firmly in the German orbit, whatever a posthumous ‘protector’ might have said. As early as 1878, Gyula Andrássy had set up Hungary’s Austro-German alliance. By 1914 the German cause had become very popular throughout the country, and very few Hungarians opposed the war: they did not have to be ‘dragged’ to the front.

Indeed, few in Hungary recognised the dilemmas, the tensions, and the traps that the country faced on the eve of the war in all their depth. On one side of the divide, Endre Ady, the poet, was the greatest of those who did, and he singled out with characteristic acuteness his nemesis: István Tisza. In the troublesome summer of 1914, the ‘deranged man of Geszt’, as Ady called the PM, after the seat of the Tisza estate, hesitated for two weeks, but in the end, he gave his sanction to decisions commencing the war which ultimately demolished ‘historic’ Hungary.

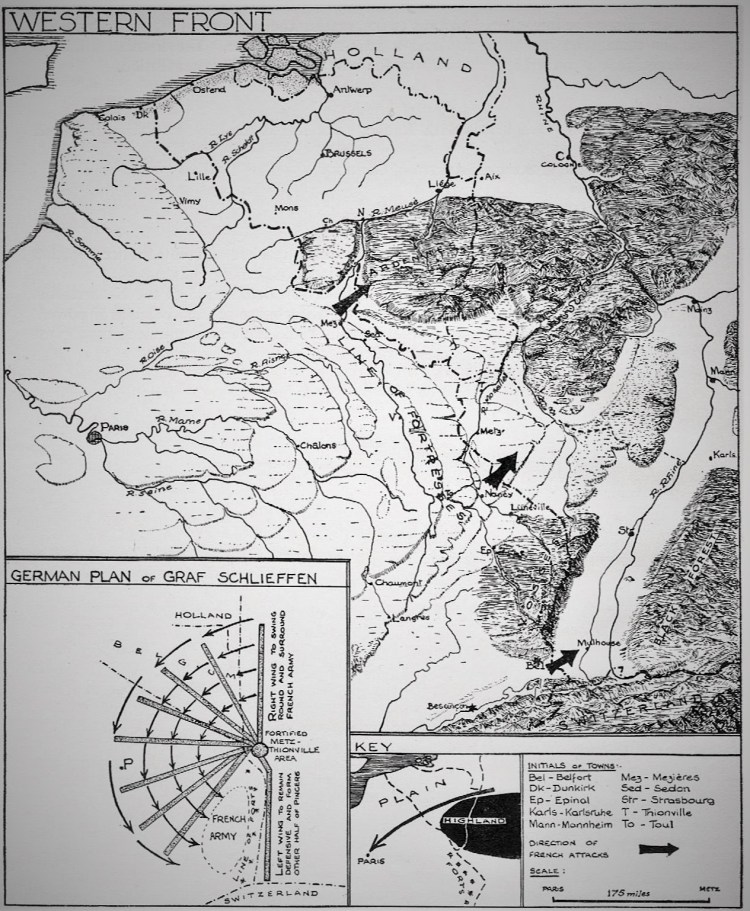

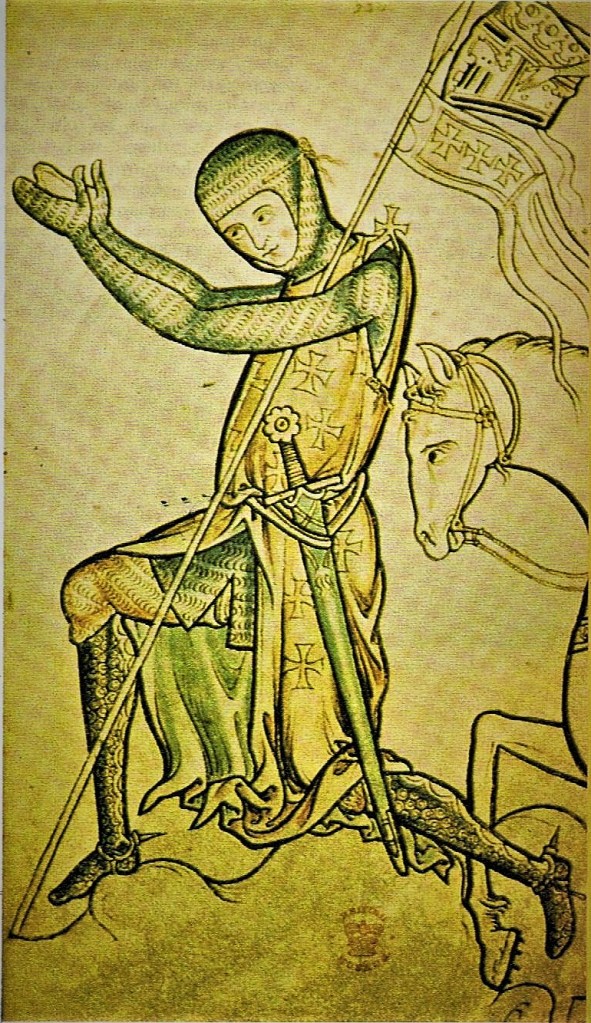

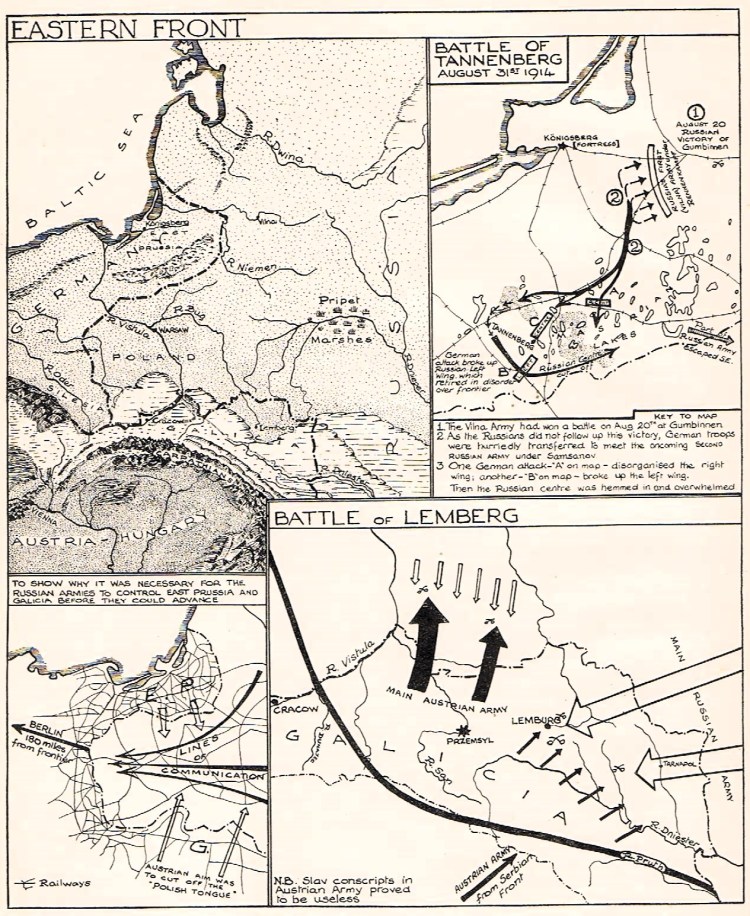

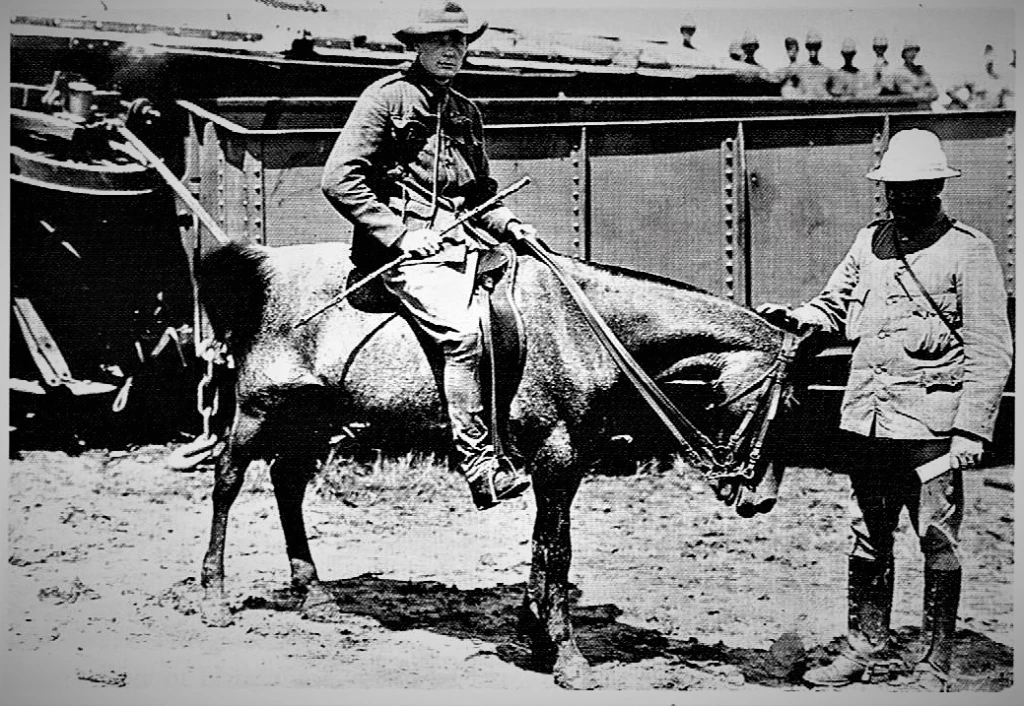

There was a universal belief, which seems incomprehensible a century later, that the war, though possibly brutish at times, would be short, involving a cast of Hungarian heroes pulling on their hussar uniforms and galloping off to glories, like in one of Miklós Banffy’s novels. The generals knew differently of course, that with millions of men and thousands of guns in the field, it could be very costly and last a long time, but economists and bankers ruled this out. Few people foresaw how paper money would fuel the war effort, and when the Hungarian Foreign Minister was asked how long the Empire could fight, he estimated three weeks. There had been an exchange of letters between Conrad von Hötzendorf and his opposite number, Helmuth von Moltke since 1909, when the Bosnian Crisis had first put a war with Russia on the table. In these, Moltke had intimated that Germany would send most of its troops against Belgium and France, and the idea was that, at the same time, the Austro-Hungarian army would keep the Russians busy in Galicia (southern Poland). Another romantic illusion was that the cavalry could sweep over the Carpathians led by the Hussars. The Austrians even nominated a governor of Warsaw just as the war broke out. Of course, they recognised that they would also have to deal with Serbia, which would mean them keeping part of the army in the Balkans for the time being.

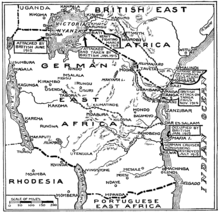

As Conrad wrote in his correspondence with Moltke, if Austria went to war with Serbia, it would send a large part of the army south. Still, if Russia intervened, Austria-Hungary would need most of its forces in the north-east, in Galicia. But what would happen if the Russians delayed intervention until these forces were committed to the Serbian Front? The Germans do not seem to have worried about this: after all, if Austria-Hungary took a proper role in the great battles to come with France and Russia, Serbia could always be sorted out later. The fact was that the Austro-Hungarians were trying to do too much, but due to imperial vainglory, they were not able to admit it. Their army, with forty-eight infantry divisions, was expecting to take on the Serbians’ fourteen and the Russians’ fifty. Conrad found a way around this by dividing the army into three groups. Group A, half of it, would go to Galicia; a ‘Minimal Balkan Group’, somewhat less than a quarter, would face Serbia; group B, the rest, four army corps in strength, two Hungarian and two Bohemian, would go south if Russia stayed out, north if it did not.

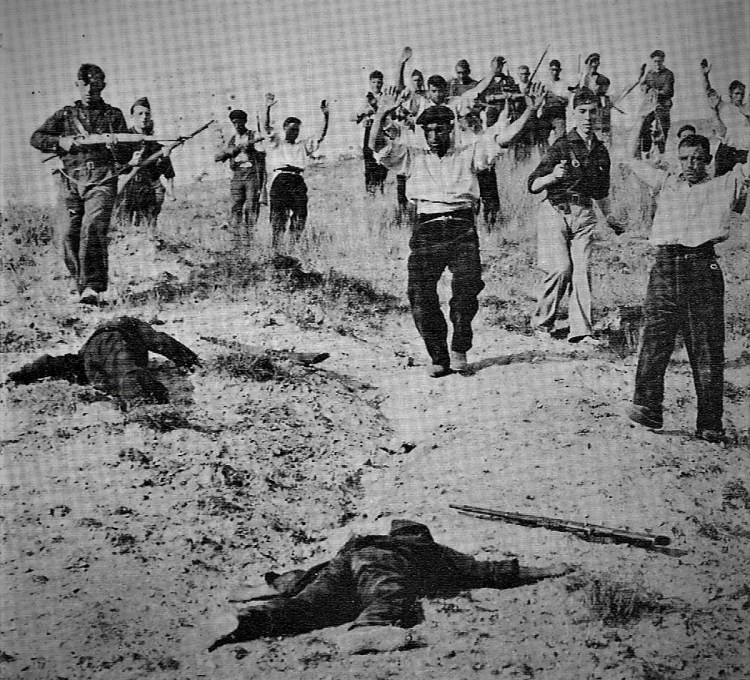

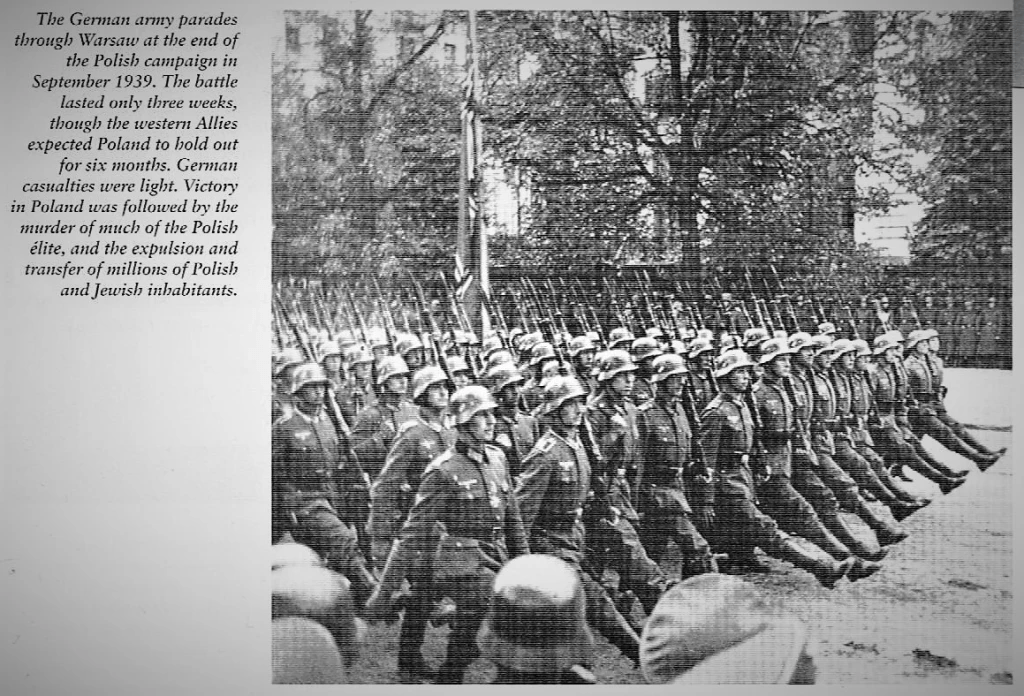

The truth was that the Austro-Hungarians did not want to fight Russia and found excuses not to do so. Berlin had told them to provoke a war with Serbia, but they delayed the presentation of their ultimatum for a month, and when the Serbians rejected it, took another three days before declaring war on 28th July. This enabled them to deploy Army Group B to the Serbian front, alleging that the Russian response was not clear. In the event, the Russian mobilisation was quite rapid, so when the Germans heard that their ally was proposing to fight a pan-European war by sending a large part of its army to a very secondary theatre, they were outraged, including the military attaché, Chief of the General Staff and the Kaiser himself. When the Austro-Hungarian army corps reached the Serbian border, it sat in tents while the Minimal Balkan Group, too small to do its job, was humiliatingly defeated by the Serbs. It then trundled across Hungary by train to Galicia and arrived just in time to take part in an enormous defeat. This was how poor military planning led to disastrous early outcomes for Austria-Hungary as it entered the war in July 1914.

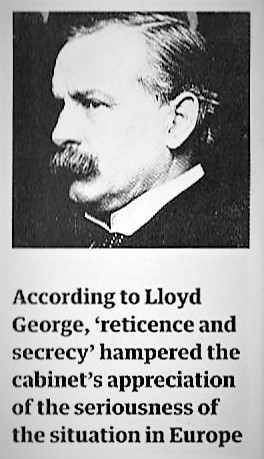

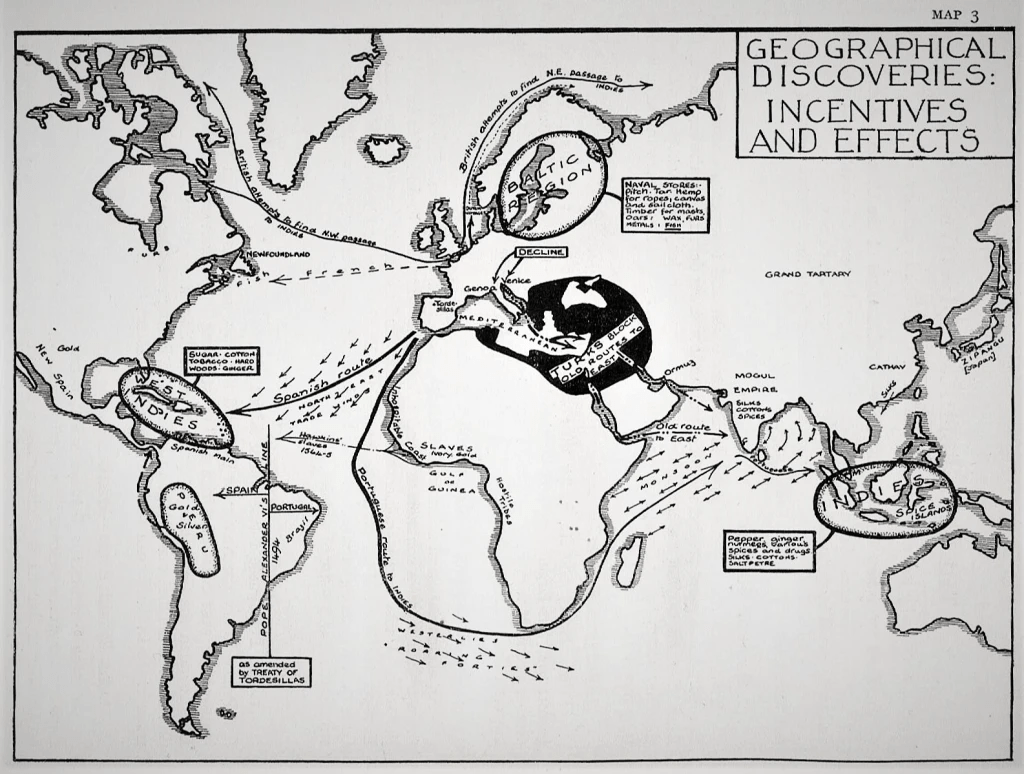

For their part, the Germans were anxious to confine the war to Austria and Serbia but were surprised by the strength of Russia’s support for Serbia and by the speed of the Tsar’s mobilisation. There were, however, no statesmen left uncommitted to war, and certainly none capable of controlling the situation; Bethman-Hollweg, the German Chancellor, and Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary, both attempted unsuccessfully to stay the hand of Austria. The Kaiser sent a twelve-hour ultimatum to Russia demanding a suspension of mobilisation, but this was not answered in time, so he declared war on Russia immediately. France stood by her ally, Russia, and declared war on Germany. Austria-Hungary’s ambitious war aims were two-fold, neither of which was purely defensive. These were:

‘(a) To crush the Pan-Slav movement, which made the task of controlling the Austrian Slavs more difficult.

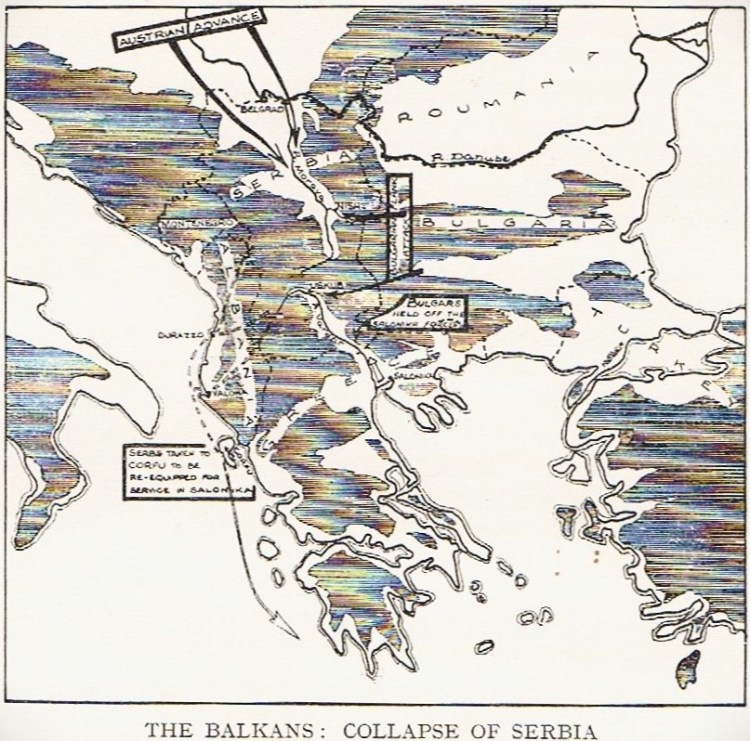

(b) To dominate the Balkans and, by crushing Serbia, to control the route to the Aegean port of Salonika.’

Irene Richards, et. al. (1938), A Sketch-Map History of the Great War and After, 1914-1935. London: Harrap., p. 18.

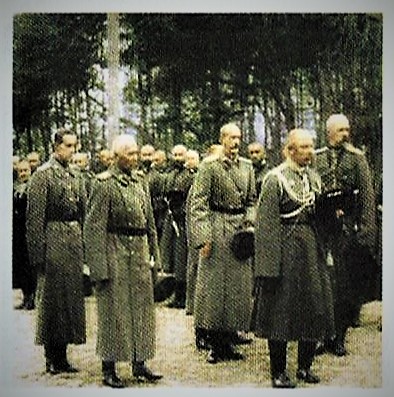

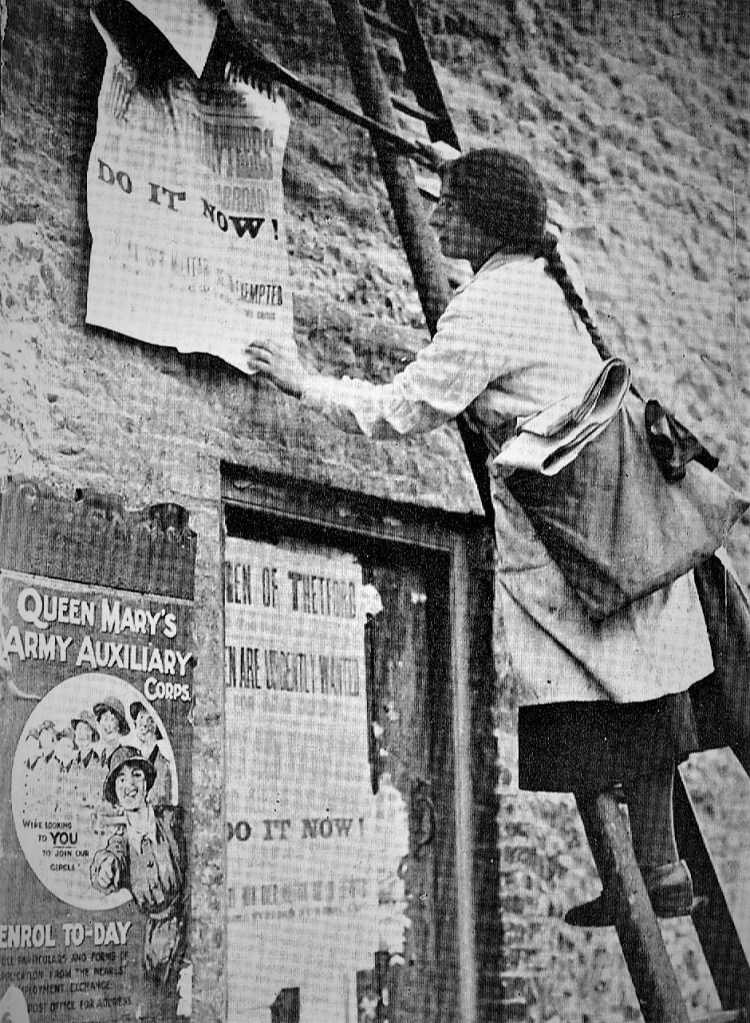

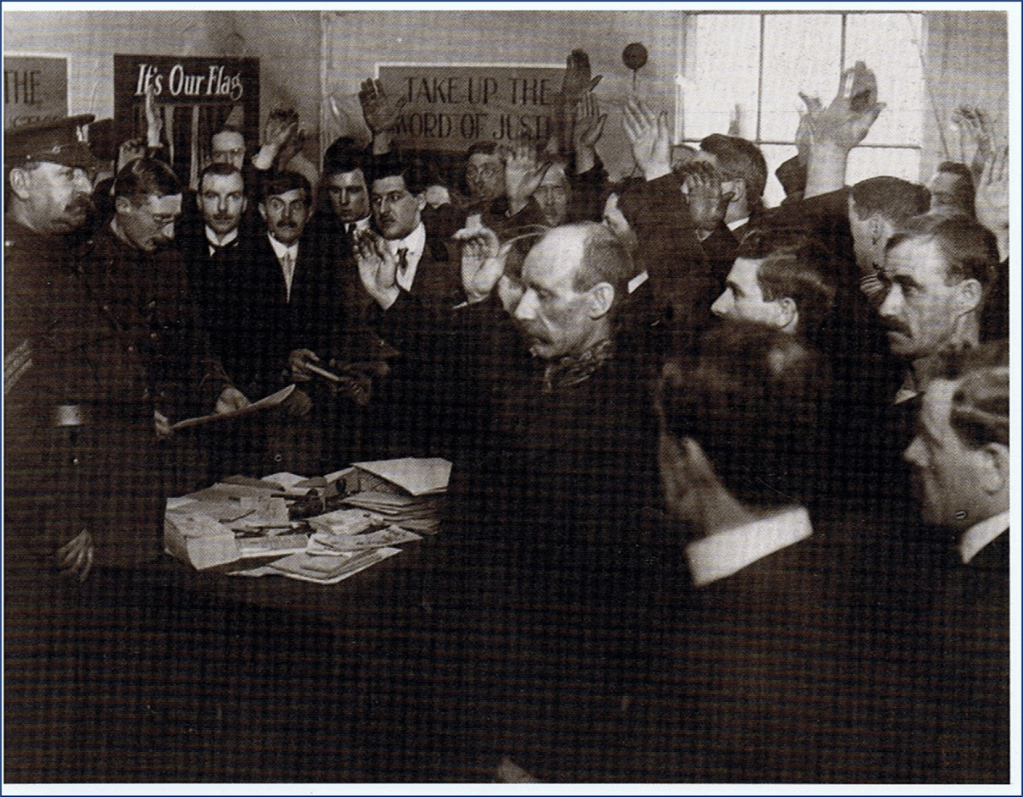

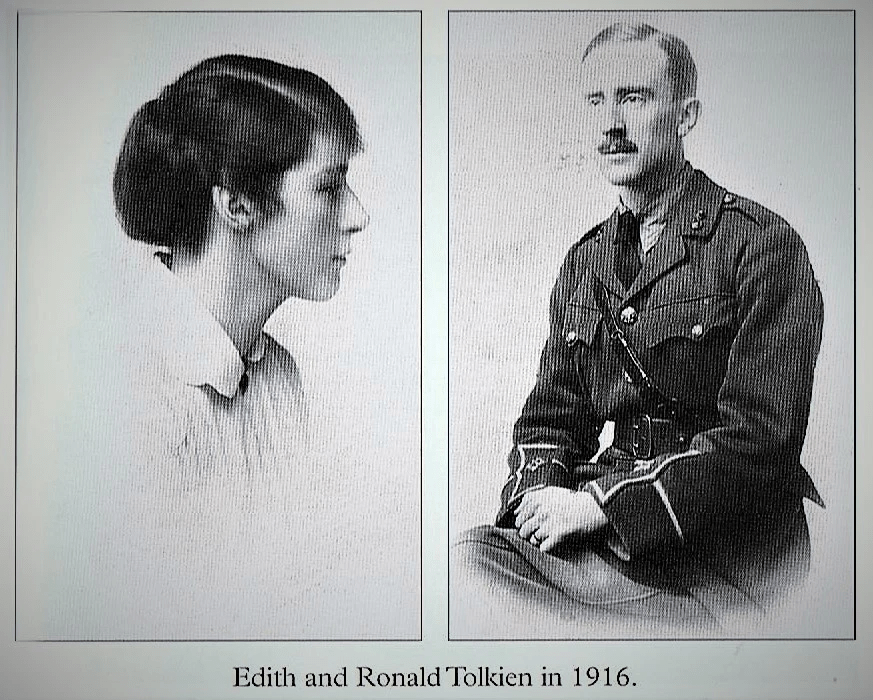

In Hungary, as elsewhere, the initial response to the outbreak of war was an outburst of patriotic enthusiasm. In parliament, which was prorogued and reconvened in November, the opposition Independence Party leader, Count Mihály Károlyi spoke of suspending political debate, hoping for democratic concessions in return for supporting the war effort. A similar motivation resulted in similar attitudes among the extra-parliamentary Social Democrats and even the national minorities, causing few headaches to the belligerent government in the early phases of the war. As in the West, Soldiers set out to the Eastern front amidst cheerful ceremonies, in the hope of returning victorious, as Wilhelm II said, ‘by the time the leaves fall’.

The War on the Eastern Front:

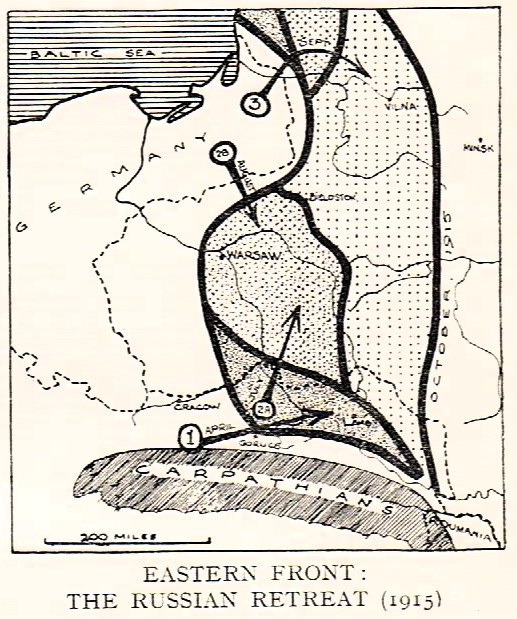

However, the war plans of the Central Powers were thwarted. Germany failed to inflict a decisive defeat on France in a lightning war and was therefore unable to lend sufficient support early enough to the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy for the containment of the Russian advance and the breaking of Serbia. Especially given the unexpectedly rapid Russian mobilisation, the forces of the Monarchy were not equal to coping with these tasks simultaneously. Although Belgrade was occupied in December 1914, the Russian army posed a direct threat to Hungarian territory. Over half of the initial Austro-Hungarian fighting force of 1.8 million died, was wounded, or fell into captivity during the first stages of the war on the fronts in Galicia and Serbia.

The Hungarian cavalry, splendidly arrayed, made a magnificent sight as it cantered across the Galician plains, but it soon ran out of fodder and returned with the hussars leading their horses on foot. The only cavalry engagement took place at Jaroslawice) when the two cavalry divisions decided to re-enact the Napoleonic Wars with a lance-and-sabre engagement which ended inconclusively. They were forced to abandon the chief city of Galicia, Lemburg (Lviv) on 3rd September. The old professional Habsburg army was almost destroyed during these first few weeks, losing about half a million men. But conscripts flowed in, and there was enough devotion to the imperial cause to keep the army in the field. This was particularly the case in Hungary, where nationalism was still strong, and there was no trouble among the non-Magyar recruits, who were mainly Croats, but even included some ‘loyal’ Serbs. Gradually, however, Austria-Hungary was being pulled into a bigger German vortex.

Conrad’s pre-war fears were coming true, for there was worse to come on the Eastern Front. It would have made sense if Austria-Hungary had offered to get out of the war following the defeat of Serbia the following autumn. The Western powers had no interest in destroying the Habsburg Monarchy at this point, for its destruction could only profit either Russia or Germany. One prominent figure in the Monarchy did guess how it would all end. This was Professor Tomás Masaryk, the leader of a small Czech progressive party, who in the winter of 1915 tried in vain to persuade the British that Czech independence might help their cause. Hungary did not have a Masyryk, however, and the only prominent figure who might have reacted in this way was Count Mihály Károlyi, who had been in France since the outbreak of the war. Otherwise, Hungary remained solidly behind the war and, with the control of food supplies within the empire, was able to assert itself and state money was being showered on arms factories in Hungary. A new crest was designed for the Empire in 1915, giving more prominence to the Hungarian insignia, and the non-Hungarian half of the empire was officially renamed Austria. Meanwhile, as Austro-Hungarian confidence revived, so did resentment at German domination, in particular in the wrangling between the two powers over the future of Poland, in which Hungary had a clear territorial stake.

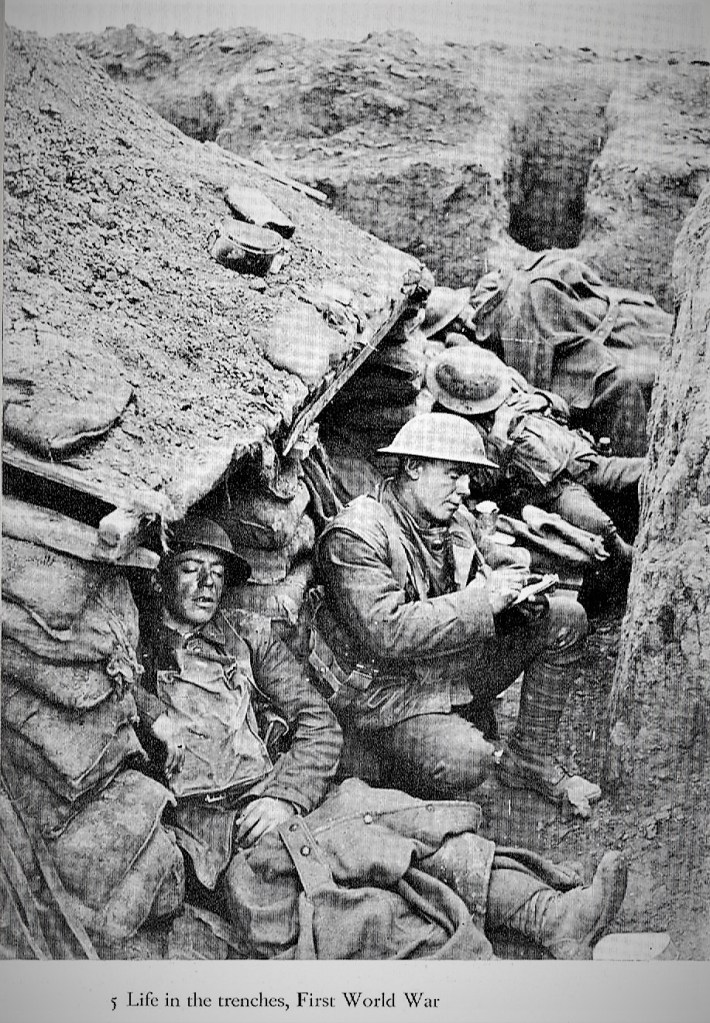

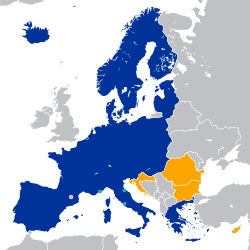

By the Spring of 1915, the type of attritional warfare that was becoming typical of the First World War was centred on the foot soldiers in the trenches armed with machine guns, and dependent on heavy artillery bombardment. This was the reality on both fronts. Until the entry of the USA into the war in April 1917, the sides were roughly equal, and the military balance was, if anything, slightly in favour of the Central Powers. Turkey hoped to avenge itself on Russia for losses suffered during the previous century, and Bulgaria was ambitious to expand further into the Balkans. Both joined the Central Powers, Turkey in the autumn of 1914, and Bulgaria in 1915, which finally helped the Monarchy to put down Serbia. By then, the Austro-Hungarian army had somewhat recovered from its earlier losses. With some German assistance, it was capable of significant success against its former allies that had now joined the side of the Entente. These included Italy, which was promised territorial acquisitions in the South Tyrol, the Adriatic, and Africa in the secret treaty of London in 1915, declaring war on the Central Powers in the following month.

At the same time, there was another field of diplomacy in play: besides propaganda directed at the hinterland of hostile countries, which naturally affected the ethnic minorities of Austria-Hungary, the Western allies gave shelter to the national committees of émigré politicians and encouraged their campaigns for the dismemberment of the Monarchy and the creation of ‘national’ states. The Yugoslav Committee, led by the Croatian Frano Supilo and Ante Trumbic, was established in London on 1st May 1915, with the programme of uniting Serbia and the South Slav inhabited territories of the Monarchy in a single, federative state (their Serbian counterparts, meanwhile, envisaged the future of the same territories as a centralised state governed from Belgrade); the leader of the Czech émigrés in Paris, Tomás Masaryk and Eduard Benes urged the creation of a Czecho-Slovak state including Carpatho-Ukraine and linked with a corridor to the future South Slav state to separate the Germans and Hungarians from each other. The Romanians, with claims to Transylvania as well as other parts of Hungary east of the River Tisza, emerged relatively late, founding the Committee of Romanian National Unity in Paris only in the latter stages of the war. A powerful Russian advance in the summer of 1916 on the eastern front prompted Romania to invade Transylvania. However, this offensive had collapsed within weeks, and in December 1916, the Austro-Hungarian army occupied Bucharest.

Until relatively late in the course of the war, the support given by the Entente powers to the high-blown demands of the national committees was largely tactical, and until the Spring of 1918, they contemplated various alternatives to the ‘destruction of Austria-Hungary’, as called for by Masaryk and Benes in 1916. They preferred (as did the representatives of the Czechs, the Ukrainians, and the South Slavs in the Austrian parliament convened in May 1917) a federal reorganisation of the Monarchy with wide-ranging autonomy granted to the nationalities, until it became clear that German influence over Austro-Hungarian policies was too great to negotiate a separate peace with it, and they convinced themselves that it could not be expected to play the traditional role of a counterpoise in the European balance of power any longer.

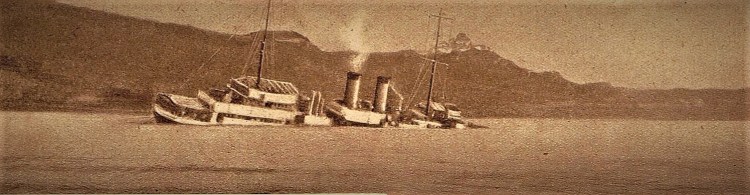

In the bloody battles fought on the slopes of the Alps and along the River Isonzo, the forces of the Monarchy fought with great determination and inflicted a decisive setback on the Italians at Carporetto in November 1917. However, the Congress of Oppressed Nations held in Rome in April 1918 served to weaken the cohesion of the Central Powers, with the recognition of the Czecho-Slovak and South Slav claims to sovereignty. Then, in the period between Russia’s falling out of the war, sealed by the Peace of Brest-Litovsk on 3rd March and the arrival of American troops on the western front in the summer, the military balance seemed, temporarily, to turn back in favour of the Central Powers. In reality, however, the multinational empire was on the brink of utter exhaustion by this time. Its economic and military resources had been under great strain since the first setbacks on the eastern front, which had also undermined the morale of the civilian population. In four years, Hungary sent somewhat over a third of the nine million soldiers of the monarchy to the eastern front, but among the casualties, half of the more than one million dead and nearly half of the two million prisoners came from the Hungarian half of the empire. Soldiers sent home increasingly exasperated letters, and in 1917 desertion, disobedience, and even mutiny were already endemic in the army.

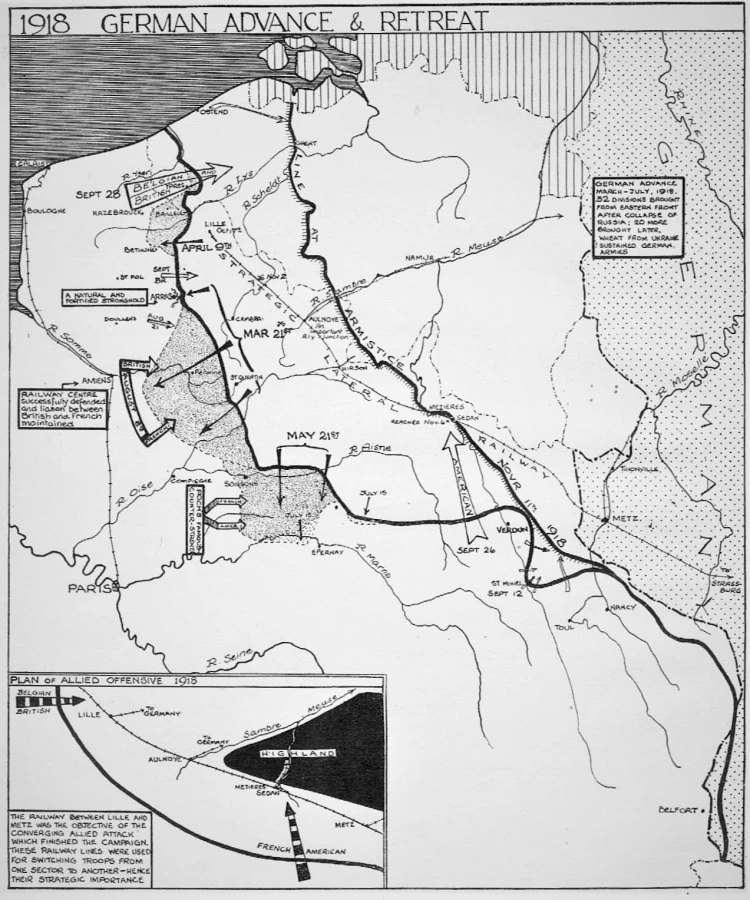

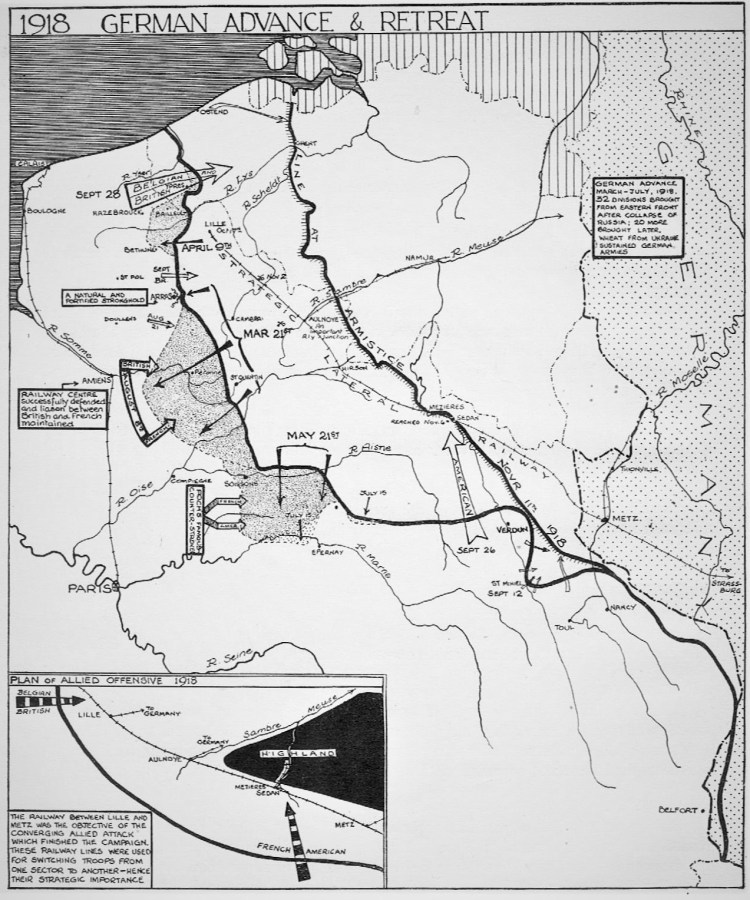

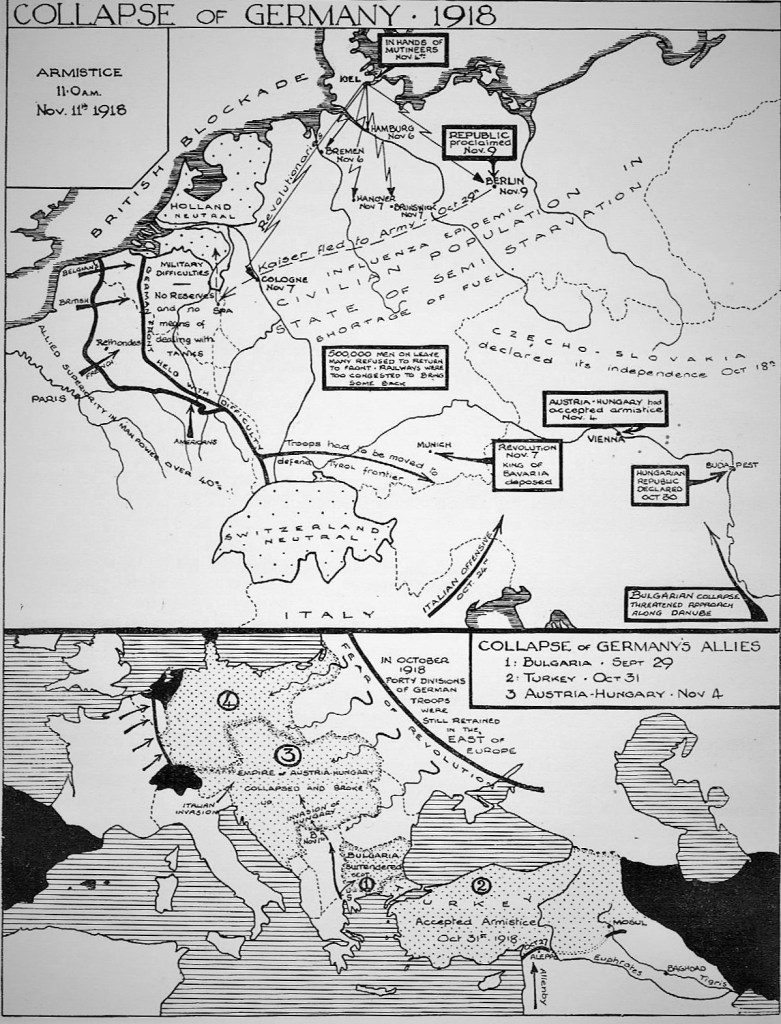

From behind the lines, the soldiers received reports of food shortages, inflation, requisitions, rationing, black marketeering, and general unrest. The general strike of 1918 involved half a million workers in all the major cities of Hungary. By this time, the traditional means of police, gendarmerie, and censorship were increasingly ineffective in suppressing the growing pacifist sentiment and the demands for social and political reform. The majority of the government party realised what the consequences of defeat would be for Hungary, whatever policies were adopted by that time. A moderate opposition, led by the younger Andrássy and Apponyi agreed that the war aims and the alliance policy ought to be maintained, but thought that well-considered reforms, instead of repression, would ensure the much-needed internal consolidation. Finally, a secessionist group of the Independence Party led by the increasingly influential Károlyi, from mid-1917 closely cooperating with radical democrats like Jászi, the Social Democratic Party, and a group of Christian Socialists, campaigning for universal suffrage and ‘peace without annexations’. Even amidst all the domestic turmoil, the military solution looked deceptively good until a few months before the end of the war: Austro-Hungarian armies were still deep in enemy lands, with the war aims apparently accomplished. It was only after the last great German offensive in the West had collapsed in August 1918, that the Entente counter-offensive started there as well as in the Balkans, that the Monarchy’s positions on all fronts became untenable. On 28th September, the Common Council of Ministers heard Foreign Minister István Burián’s brief and unequivocal verdict: ‘That is the end of it.’

Endings & Beginnings:

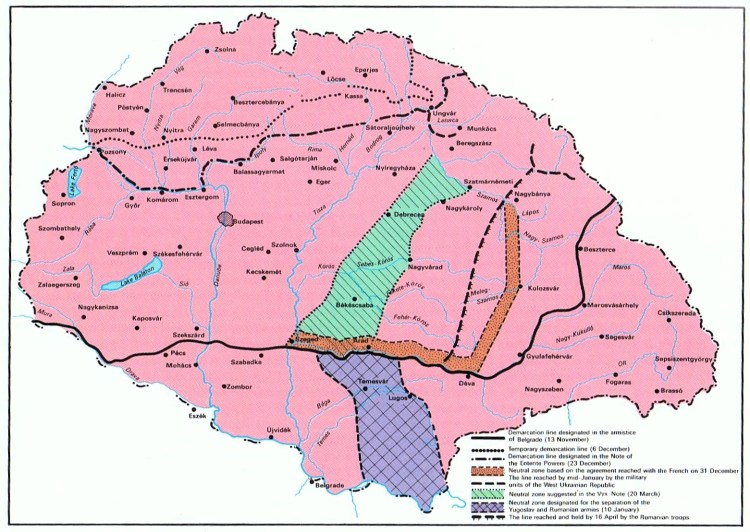

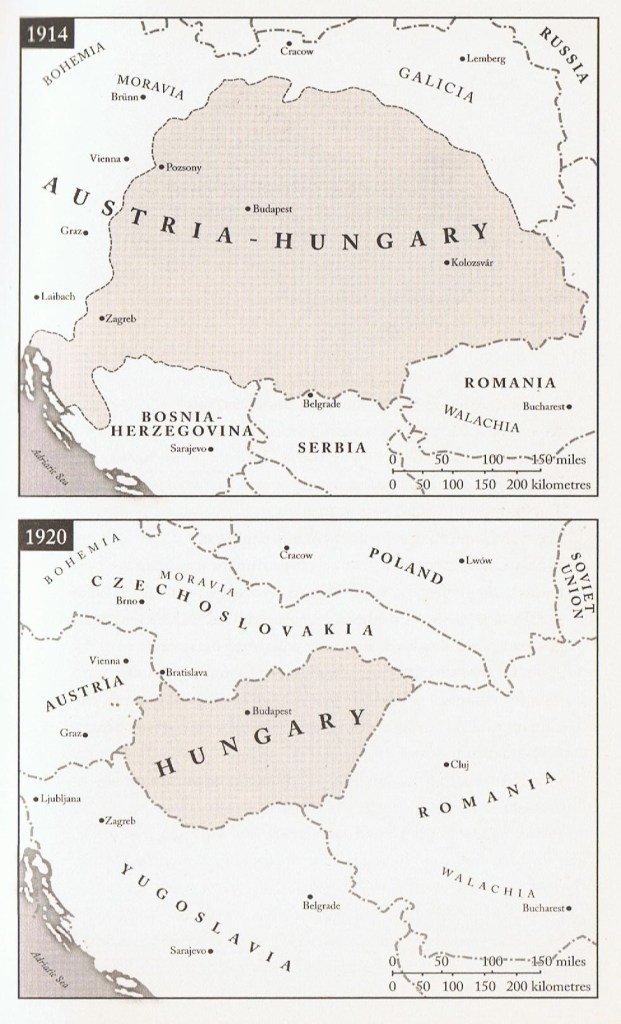

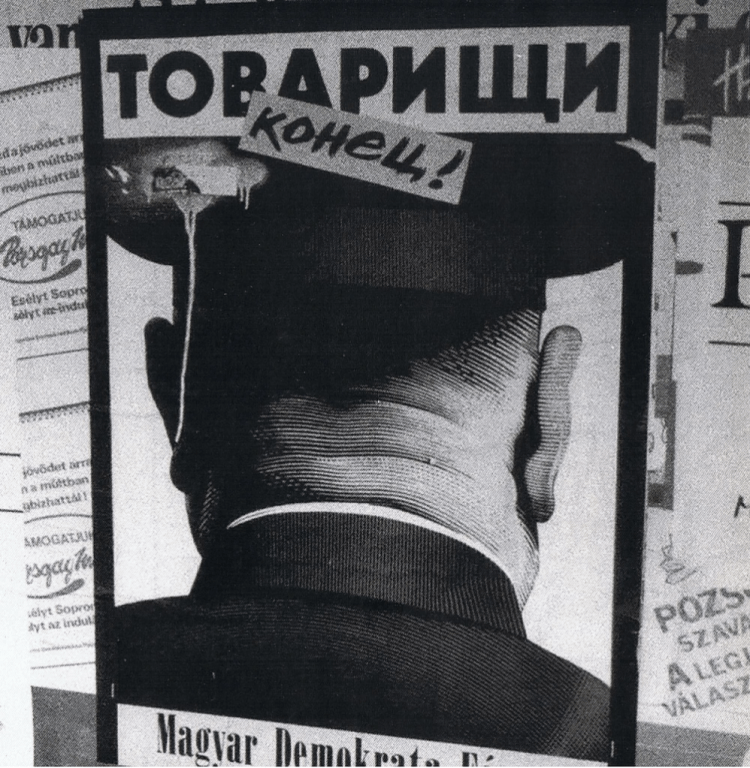

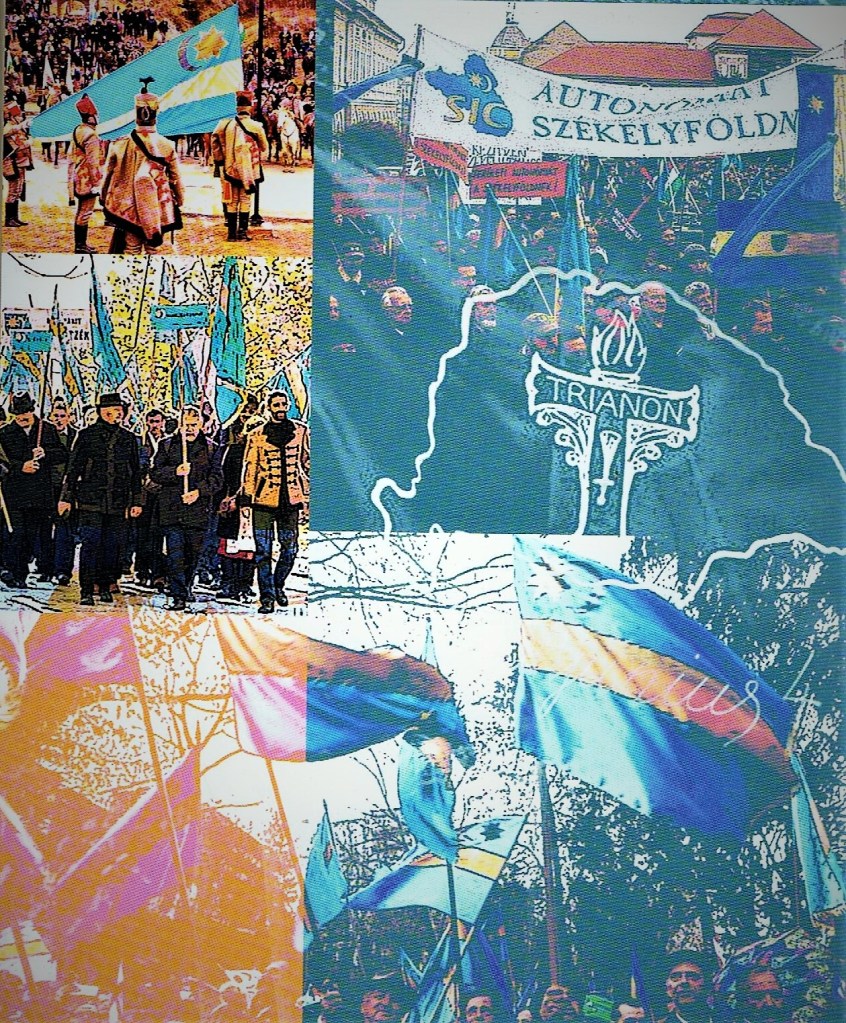

On 2nd October, the Monarchy solicited the Entente for an armistice and peace negotiations, based on Wilson’s fourteen points. But having recognised the Czecho-Slovak and South Slav claims, Wilson was no longer in a position to negotiate based on granting the ethnic minorities autonomy within an empire whose integrity would be maintained. By this time, the Monarchy was collapsing into chaos. By the first half of October, all the nationalities had their national councils, which proclaimed their independence, a move which now enjoyed the official sanction of the Entente; on 11th October, the Poles, and between the 28th and the 31st the Czechs, the Slovaks, the Croats, and the Ruthenes seceded, followed on 20th November by the Romanians. Finally, the provisional assembly in Vienna declared Austria an independent state. This, in turn, changed the face of Hungary beyond all recognition. Paradoxically, the dissolution of the historic Kingdom of Hungary, one of the greatest shocks the country suffered in terms of its economic resources, political influence, and self-confidence, also created the opportunity for a new beginning. The situation held out the promise of overhauling the ossified social and political structures and institutions that were partly responsible for the dissolution.

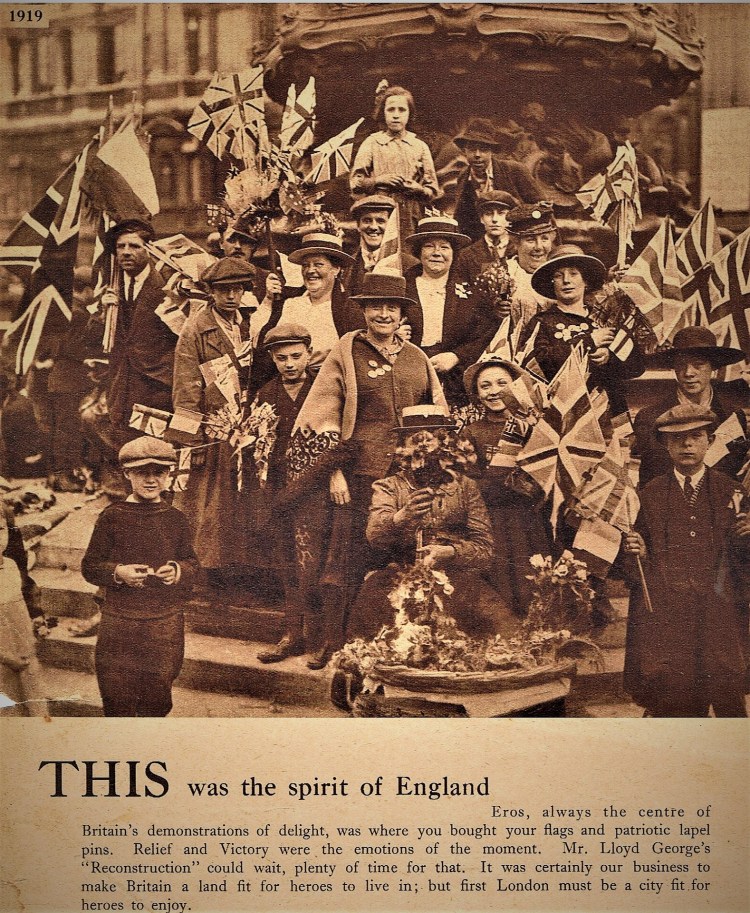

When 300,000 Hungarian former prisoners of war returned home in 1918, having seen what the Bolsheviks could do firsthand, their minds turned to the possibility of beginning a Red Revolution in their own country. At the beginning of November, they were joined by comrades from the Italian front where they had been given a humiliating armistice at the Villa Giusti near Padua. In Budapest, after brief resistance and a few casualties, great demonstrations caused a change in government. Tisza had already admitted on 24th October that the war was lost, and his rival, Mihály Károlyi, came to the fore, as the obvious opposition candidate. On 25th October, a National Council was set up, and when a crowd of its supporters moved on the Vár, there was a shooting, leaving three dead and seventy wounded. The new King/Emperor (since his uncle’s death on 21st November 1916), prevaricated, and the Palatine Archduke József appointed Károlyi as Prime Minister on 31st October. For a time, the atmosphere in Budapest was euphoric in what became known as the Aster Revolution, coming on All Saints’ Eve, when the custom was to wear a button-hole, which now became a revolutionary symbol. The Astoria Hotel became its centre, from where some soldiers drove to the house of István Tisza and shot him in front of his wife and niece. With an epidemic of Spanish influenza striking the capital and order breaking down, a deputation of high aristocrats, including an Eszterházy and a Szechényi, went to the King and asked him to abdicate. On 13th November, he stepped down from public affairs.

Károlyi faced another, immediate problem of an allied invasion. On the last days of the war, Romania had again invaded and was advancing into Transylvania, where it was met by local Romanians who intended to unite the country with those in Moldovia and Wallachia. In the southern provinces, there was similar disaffection among the Serbs and the Croats, aiming to set up the new Slav state (‘Yugoslavia’) under the Serbian king. Károlyi was unable to establish armistice lines because he had allowed the army to demobilise and disintegrate. So he went to see the Entente commander in Belgrade, Louis Franchet d’Esperey, announcing himself as head of the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council, which drew the famous response, “You’ve fallen that low, have you?” The only force offering resistance to the Romanians was the Székely Division, but it got no support from Budapest since it was viewed as counter-revolutionary. Only one Hungarian success was achieved, at Balassagyarmat, and that was despite Károlyi’s orders for the Széklers to stand down. By the following March, the Allied occupation had taken more Hungarian land, and the shrunken borders of post-Trianon Hungary were already beginning to take shape. Károlyi had hoped that long overdue radical reforms might stabilise the situation and that his nationalities’ secretary, Oszkár Jászi would be able, through federalisation, to retain the loyalty of the non-Magyar minorities. But the Czecho-Slovaks and Serbs were already establishing their own independent states, and Jászi got nowhere. Károlyi was discredited and forced to resign, and his government was replaced, from March to July 1919, by Béla Kun’s Soviet-style Republic.

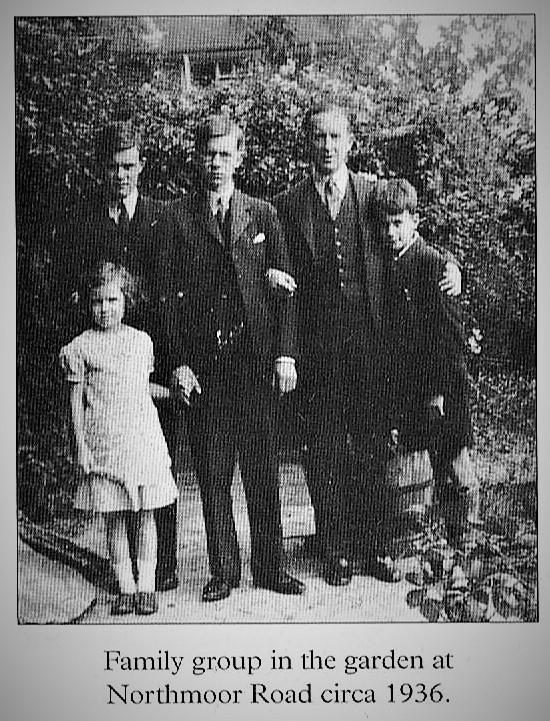

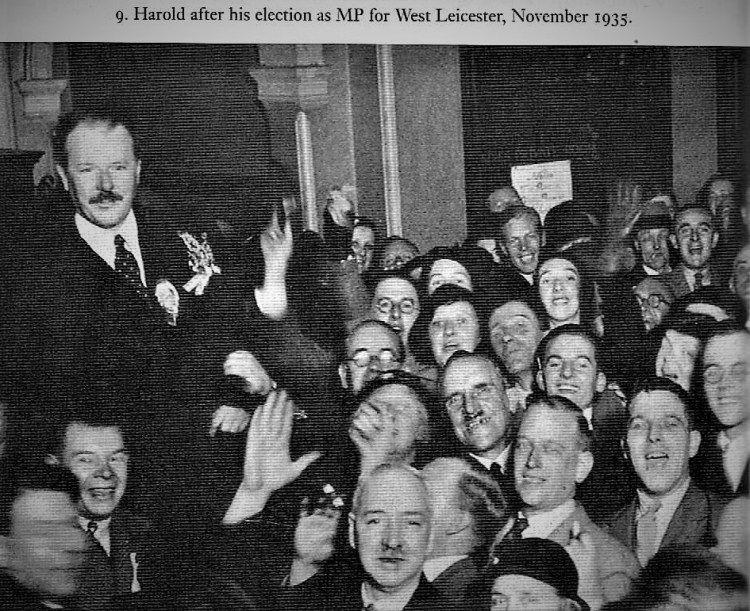

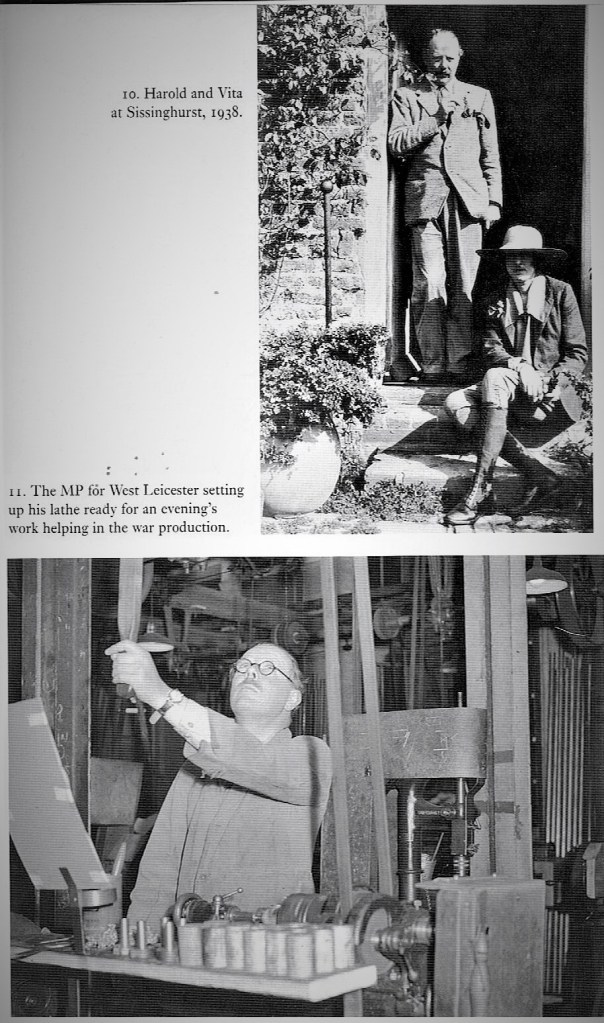

Aside from the insurmountable domestic hurdles Kun faced, he had great problems with the allies. In April, General Smuts, the South African member of the British War Cabinet, steamed into the Eastern Station in Budapest and stayed for twenty-four hours. Harold Nicolson, his Foreign Office aid, observed the city he had known before the war as a child in his father’s cramped accommodation on Andrássy Boulevard when his father had been posted there by the FO. The cramped nature of the apartment, he said, had robbed it of the ‘stately ease’ of its environs.

On 3rd April, Harold woke up to find their train resting in a siding at the Keleti Palyaudvár, encircled by Red Guards with ‘fixed bayonets and scarlet brassards’. Smuts insisted on conducting the negotiations from the wagon-lit, as to have done otherwise would have implied recognition of the new régime. Harold had last visited the city in 1912 when it was still in its heyday. It rained continuously throughout the day, and – to add to the gloom – there was also an energy crisis – with supplies of gas and electricity at a premium. The negotiations centred on whether or not the Bolsheviks would accept the Allies’ armistice proposals, lines that would commit them to considerable territorial losses, particularly to the Romanians. They hesitated all day, and in the interval, Harold decided to reacquaint himself with Pest. Later in his diary, he wrote: ‘The whole place is wretched – sad – unkempt.’ The Communists laid on scenes for him, tableaux such as the gathering of middle-class figures in the Hungaria Hotel, Budapest’s leading hotel, supposedly taking tea undisturbed. He was not deceived, however, especially since the Red’s own headquarters were in the hotel on the Danube Embankment. Red Guards with bayonets patrolled the hall, but in the foyer what remained of Budapest society ‘huddled sadly together with anxious eyes and in complete, ghastly silence,’ sipping their lemonade ‘while the band played.’ They left ‘as soon as possible … silent eyes search out at us as we go.’

Later that evening Kun returned to the train’s dining car and handed Smuts his answer. Smuts responded, ‘No gentlemen, this is a Note which I cannot accept. There must be no reservations.’ Although prepared to offer minor concessions, Smuts’ terms of reference were uncompromising. Kun had first to agree to the occupation by the Allies of a neutral zone separating the Bolsheviks from the Romanian army; if he complied, the Allies would be prepared to raise the blockade strangling their régime. He desperately needed allied recognition of his government, but he inserted a clause into Smuts’s draft agreement that the Romanian forces should withdraw to a line east of the neutral zone, in effect to evacuate Transylvania. Smuts would not countenance such a deal. He made a final appeal to reason. But the Bolsheviks, ‘silent and sullen’, proved obdurate. Smuts, behaving with ‘exquisite courtesy’, bid the Bolshevik leaders ‘goodbye’.

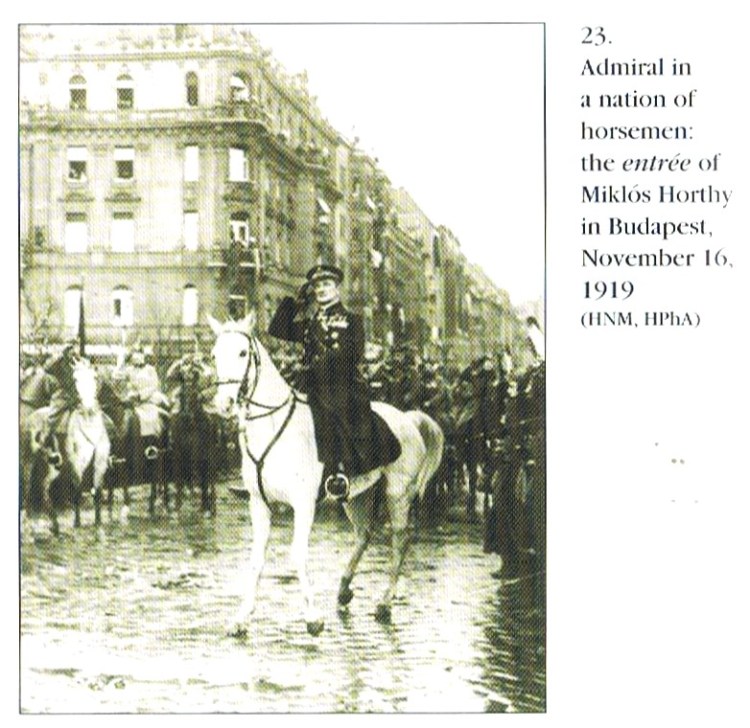

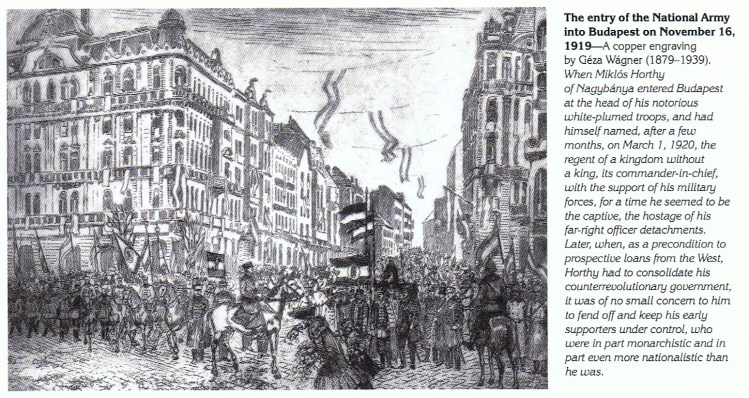

Smuts had formed the opinion that the Kun episode was ‘just an incident and not worth taking seriously’. On the day after he completed his account, The Allies authorised the Romanians and Czechoslovaks to move forward, whereupon Kun organised a ‘Red Army’ of his own, which did retake towns in Slovakia, including Kassa (Kosice), but his forces were eventually overwhelmed and in late July he had to resign in failure. On 1st August, Béla Kun fled the capital in the face of the invading Romanian armies. Central Hungary, and even Győr in the west, remained occupied by the Romanians, who looted comprehensively and were only stopped when they threatened the precious exhibits of the National Museum. The Romanians eventually left when a provisional government was established in Budapest, with the help of the British and a counter-revolutionary organisation led by ‘White’ officers that met at the Britannia Hotel in Pest. This comprised representatives of the old ruling cliques including Count Gyula Károlyi, Count István Bethlen, and Admiral Horthy, the latter becoming ‘Regent’.

For the world’s leaders gathered in Paris, the spectre of Bolshevism was truly haunting Europe: it threatened widespread starvation, social chaos, economic ruin, anarchy, and a violent, shocking end to the old order. It was small wonder, then, that Béla Kun’s strike for communism triggered many anxious moments for the Supreme Council at the Paris Conference, but this was not as much of a ‘trump card’ as it was for Germany when it came to securing good terms at Paris, as the difference between the two treaties proved. In Germany, by the end of 1918, the Communist revolution had been stopped, and a parliamentary republic was soon proclaimed at Weimar. The key to this was that the Social Democrats were in charge, and used the Freikorps on their own terms. In Hungary, the reactionaries made the running, leading to Admiral Horthy’s ‘white horse putsch’ of November 1919. By the time of Trianon, Béla Kun’s brief experiment was long over, but Hungary was paying the price for his brief but violent insurrection, in blood and land. In 1927, Harold Nicolson refused a posting to Budapest on the grounds that he had been too involved in defining Hungary’s frontiers at Paris, and, more jokingly, on the ‘social’ grounds that he could ‘neither shoot nor dance’ (Norman Rose, 2005; Harold Nicolson, pp. 6, 96-98, 153; extracts from letters and diaries).

Conclusion: To what extent was Hungary ‘dragged into’ the War by her allies?

Germany was anxious to confine the war to Austria and Serbia, and Italy did not become an active member of the Triple Alliance until 1915 when it declared war on France. Apparently, there were, however, no statesmen in either Austria-Hungary or Germany who were capable of controlling the situation, either before or during the July Crisis; Bethman-Holweg, the German Chancellor tried to stay the hand of Austria, without success, and the Prime Minister of Hungary, István Tisza, prevaricated as long as he could, before giving in to the pressure from the Imperial Council to back the ultimatum against Serbia. There were also longer-term causes going back to the 1870s, like the treatment of the minority nationalities, which were determined by the imperial partners, of whom Hungary took the hardest line with Serbia, Romania, and the other Slav nations. Hungary, of course, had more to lose from the growth of Pan-Slav nationalism. Clearly, however, the Alliance as a whole underestimated the speed and strength with which Russia would come to the aid of its ally, Serbia, turning a regional conflict into a world war. So while Hungary became tangled up in a complex web of Balkan rivalries, it was not a victim of Great Power machinations, but rather of its own sins of omission and commission.

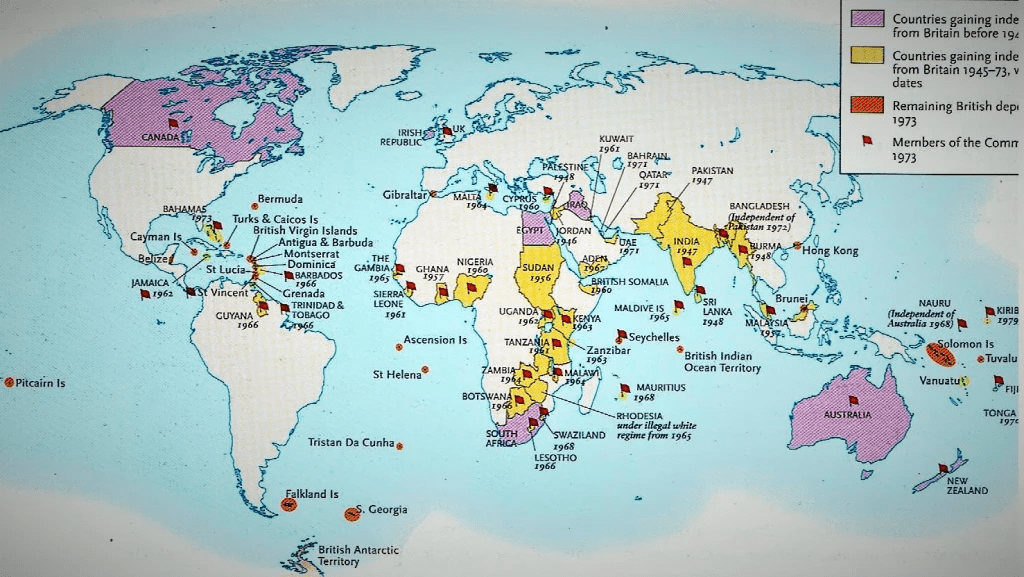

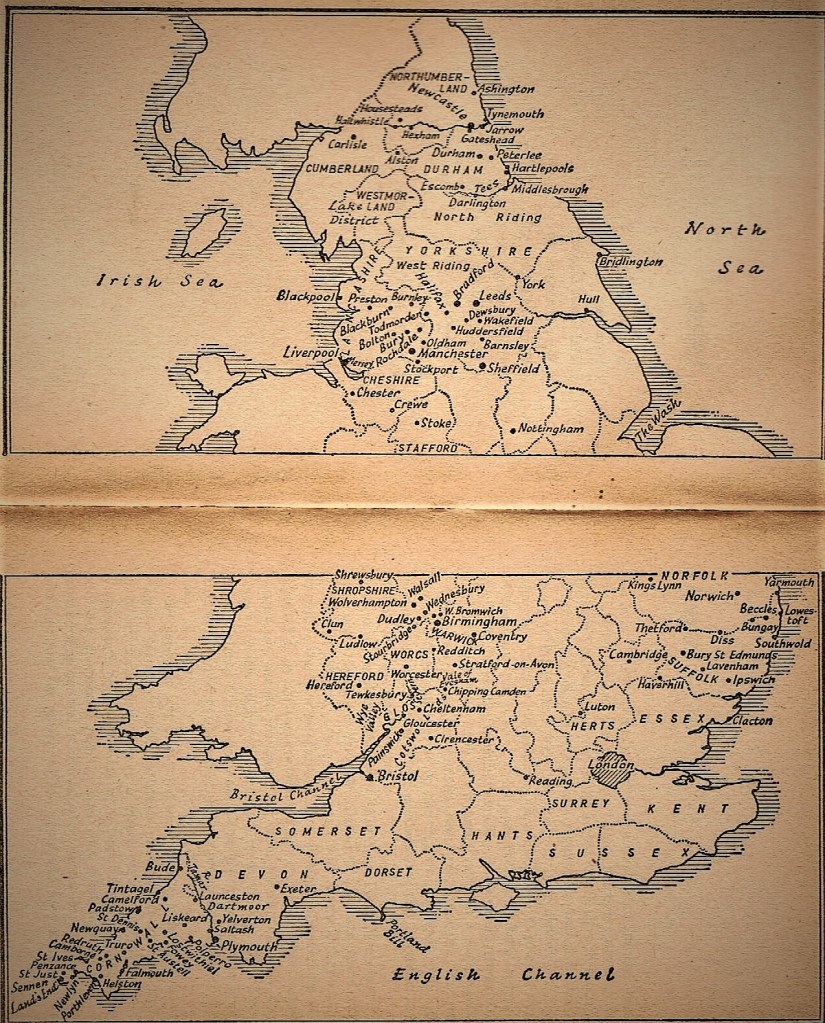

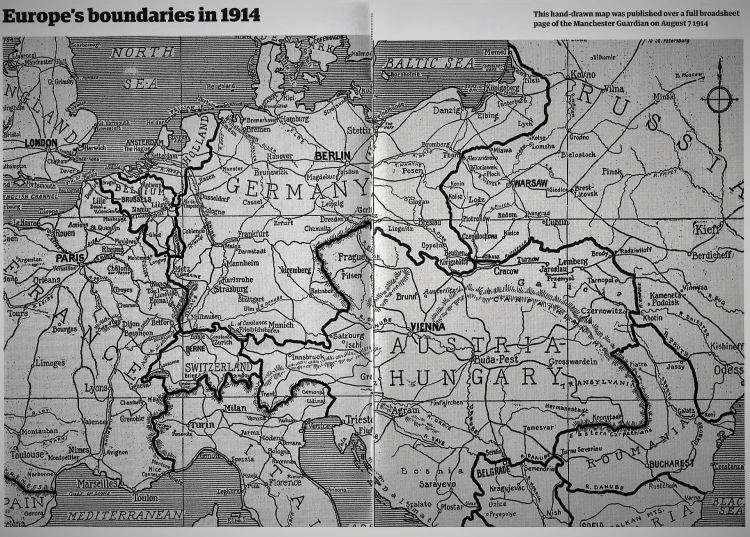

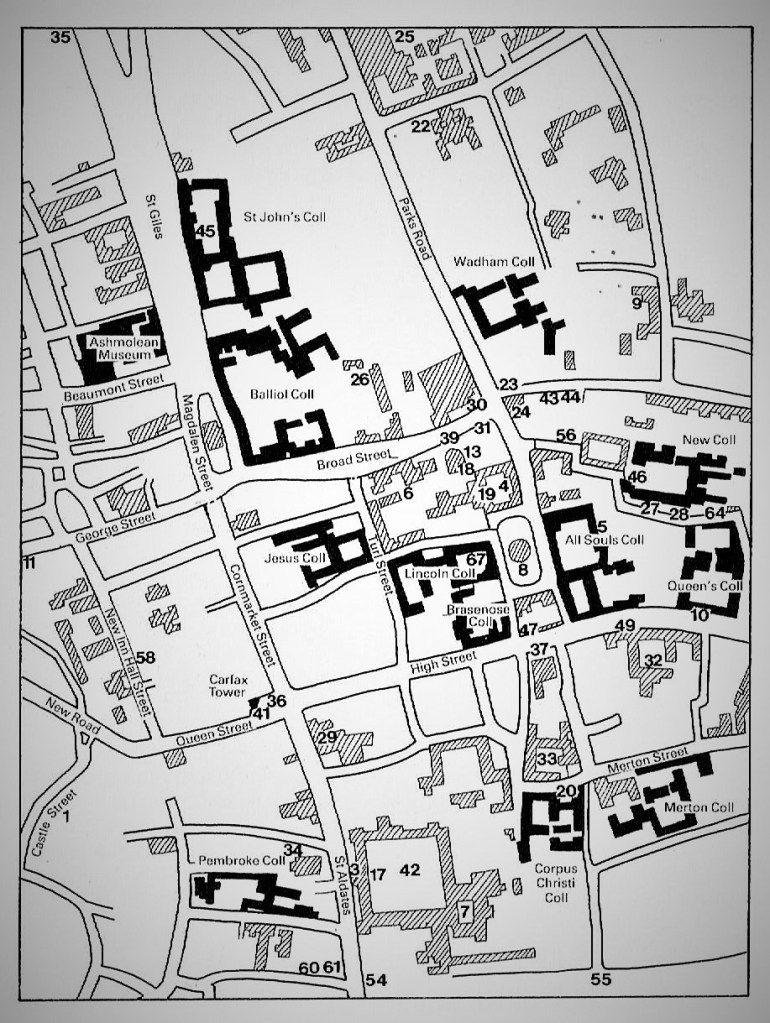

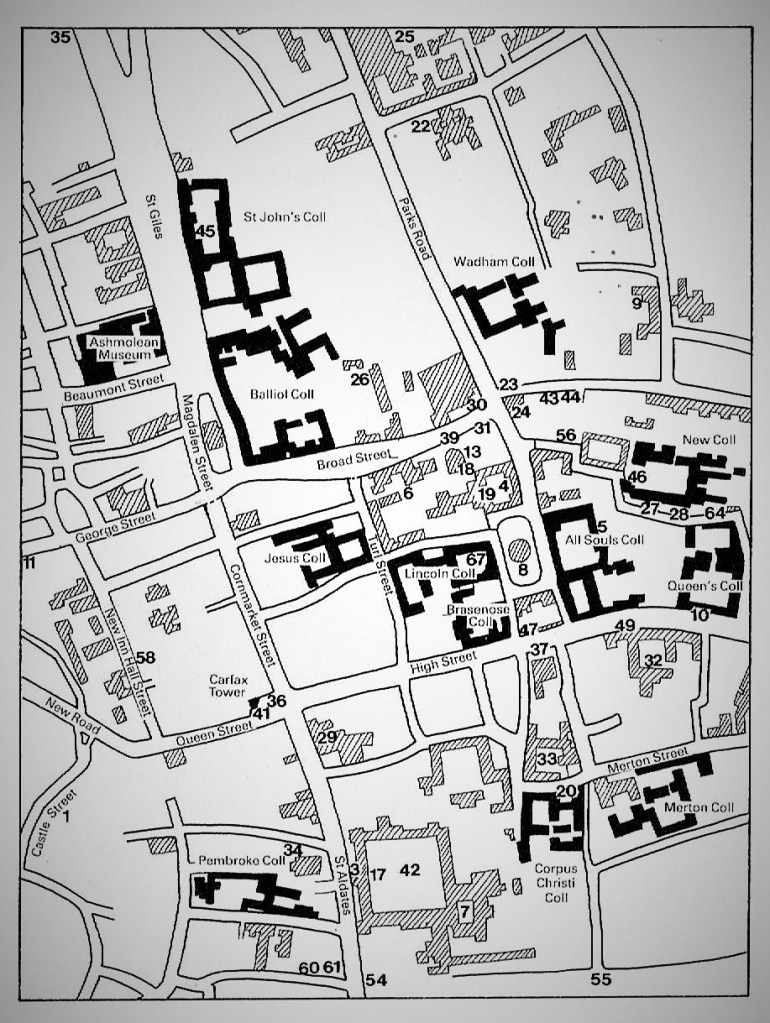

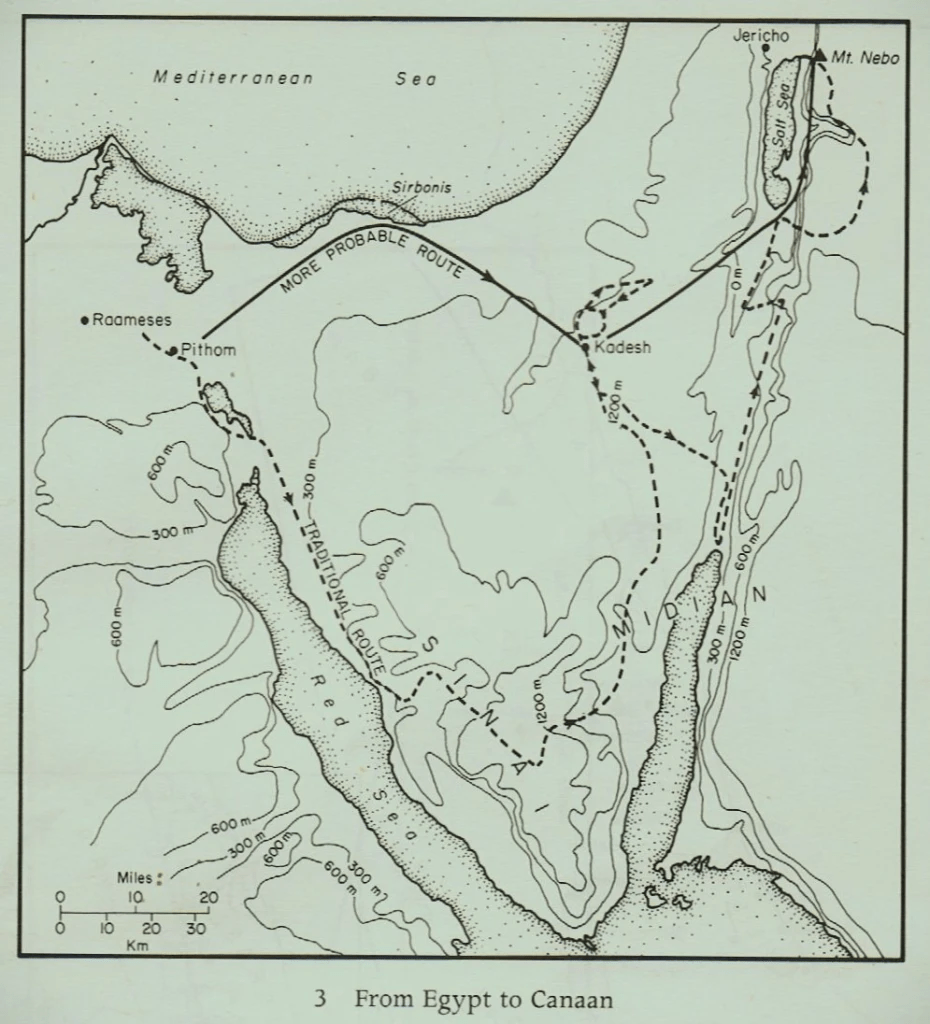

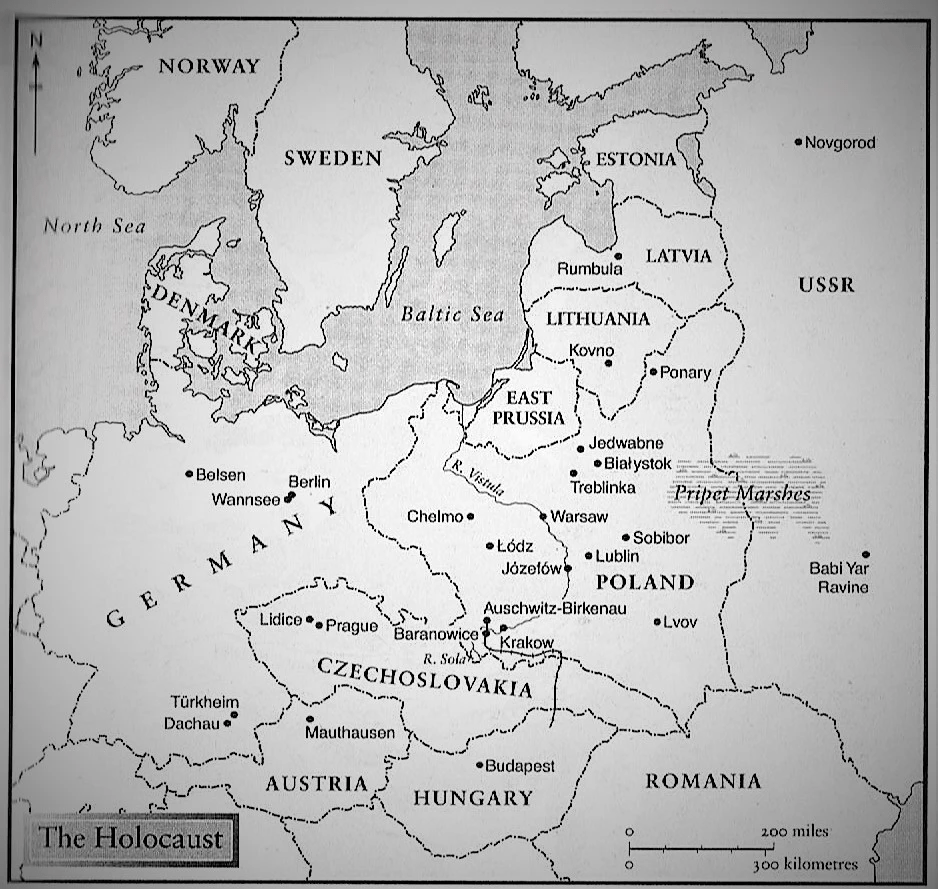

Appendix: Maps of Hungary & The Great War:

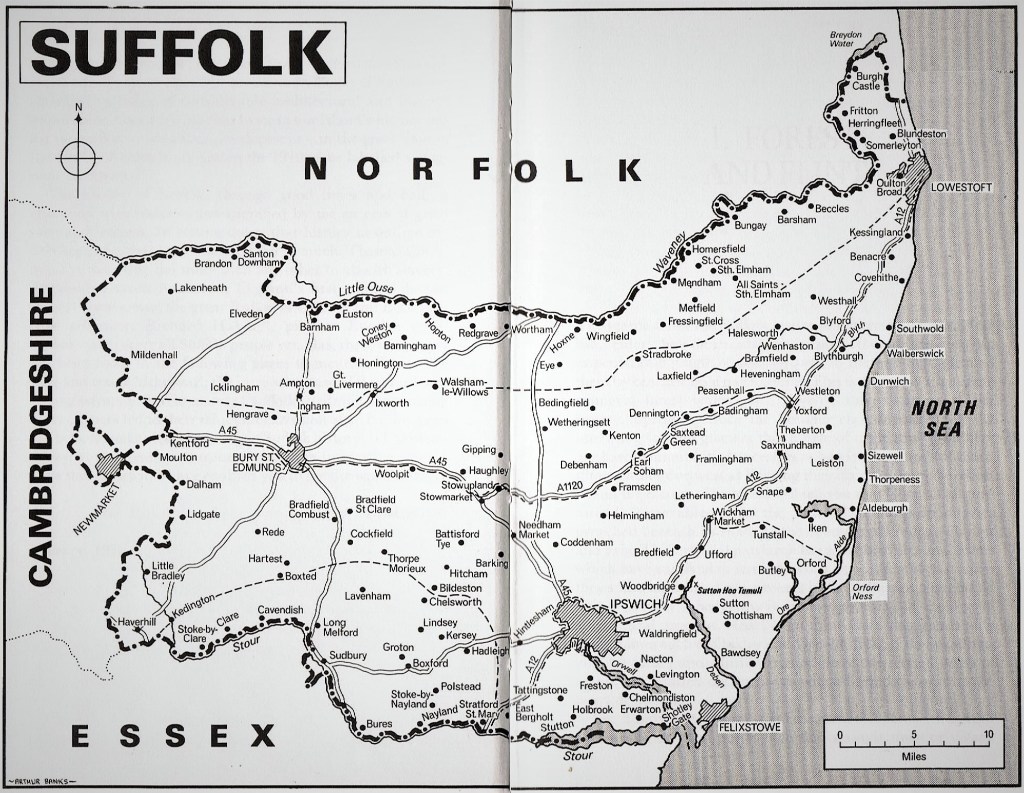

1. Austria-Hungary – Ethnic Diversity & Divisions:

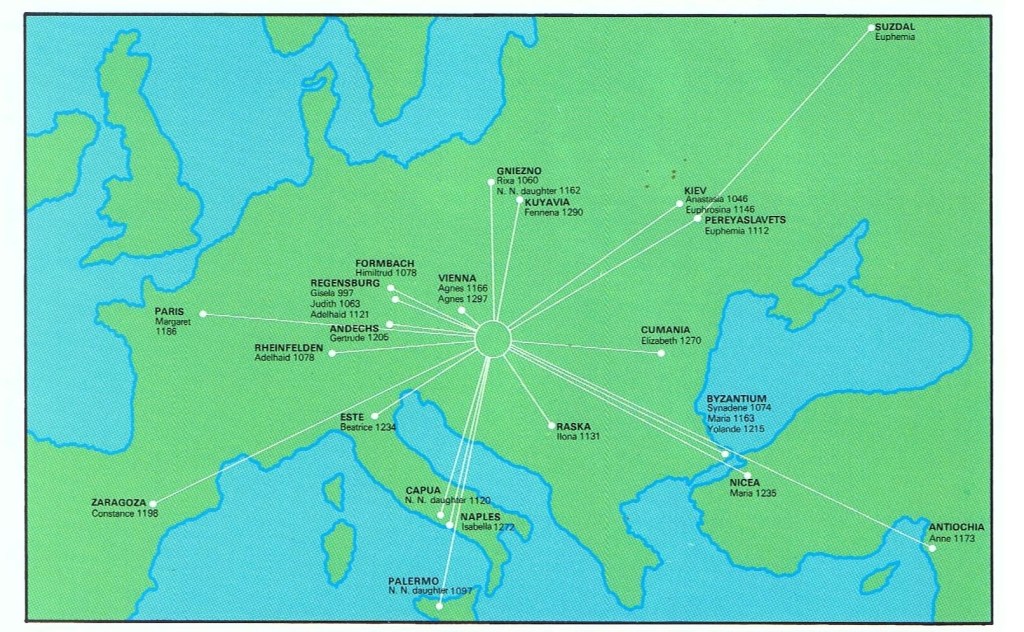

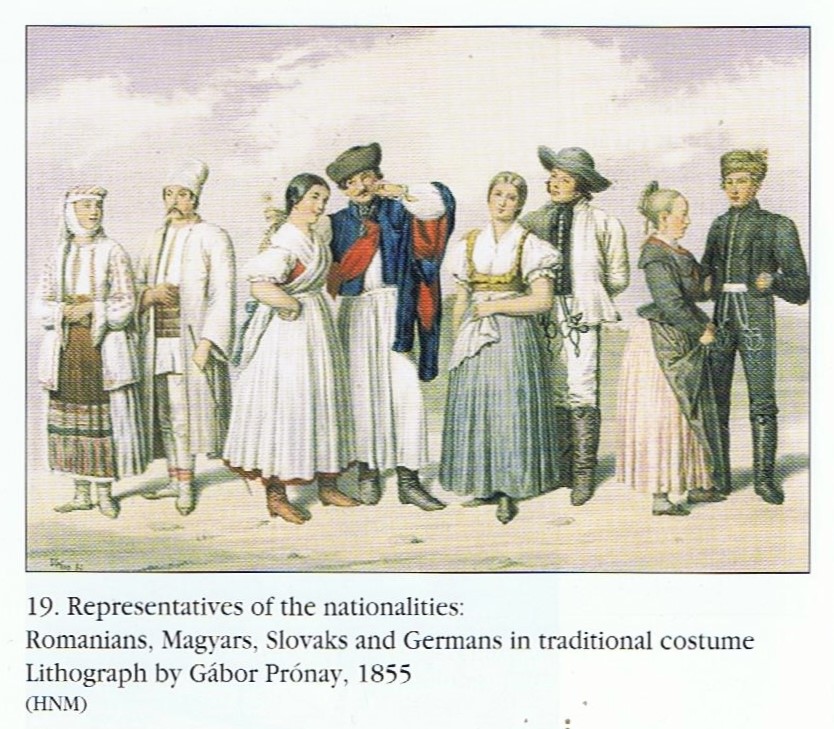

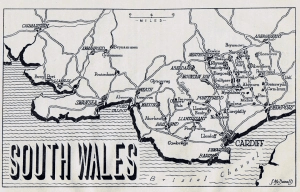

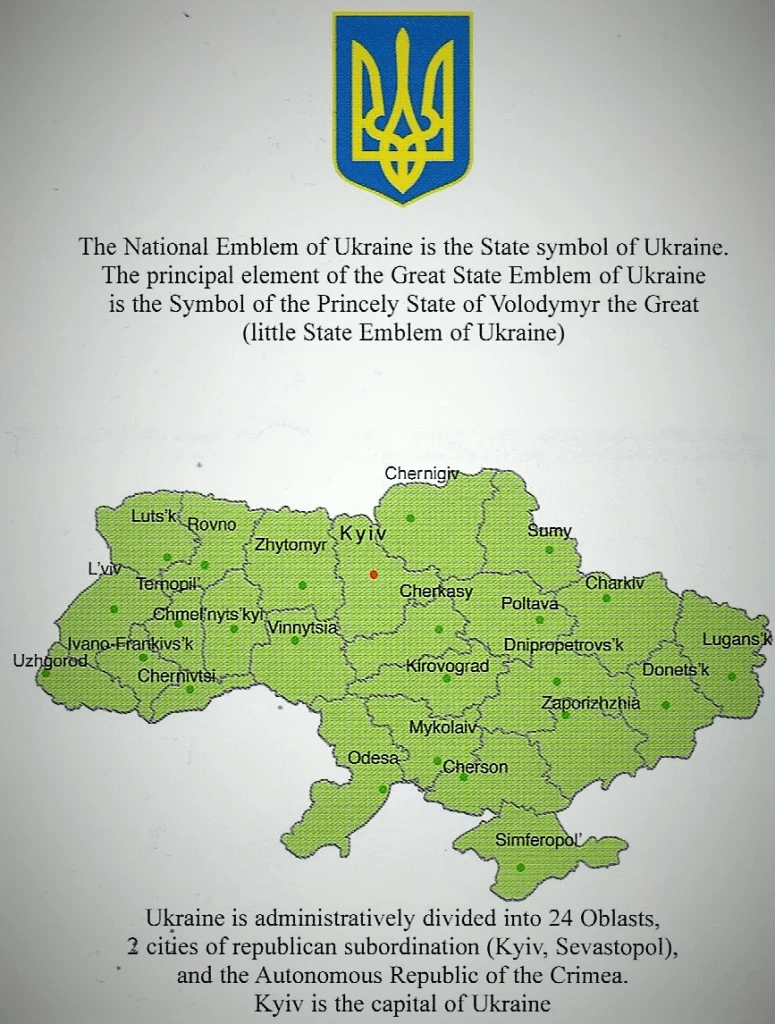

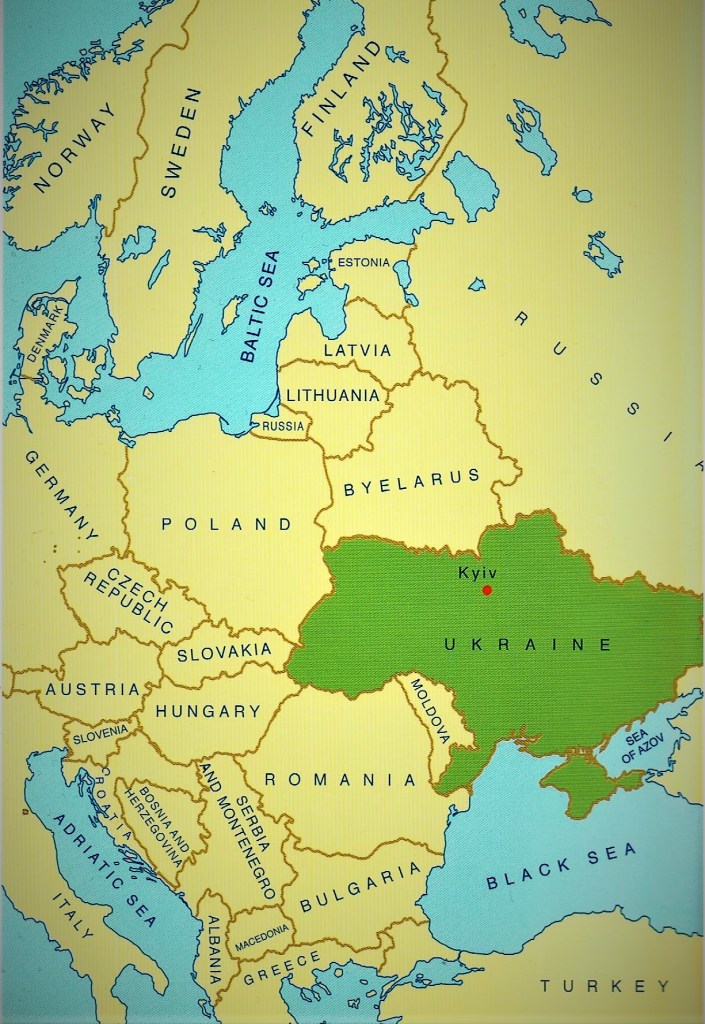

Franz Josef’s empire was a denial of the fashionable 19th-century doctrine of national self-determination. His subjects spoke at least twelve languages and adhered to four major religions – Catholicism, Protestantism, Orthodoxy, and Judaism. The Habsburgs had long recognised that ‘nationalism’ was their deadly enemy, but even an enemy based on loyalty to a dynasty rather than a national ideal could not avoid the issue of language rights. Although some Habsburg dominions possessed clear linguistic majorities, such as the overwhelmingly German-speaking provinces in the Alpine West or the Hungarian-speaking villages of the plains, most parts of the empire contained a mixture of peoples and faiths.

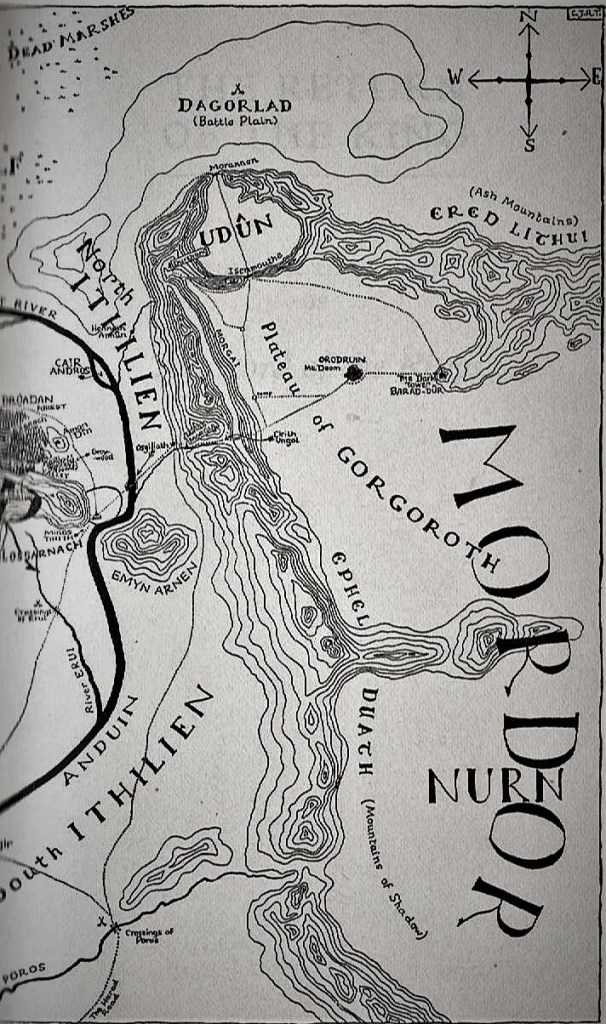

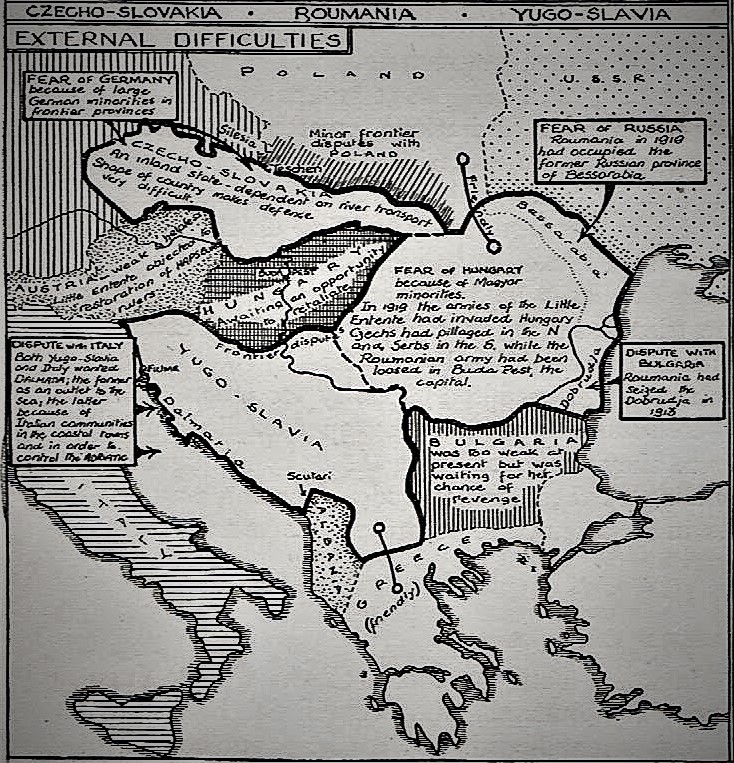

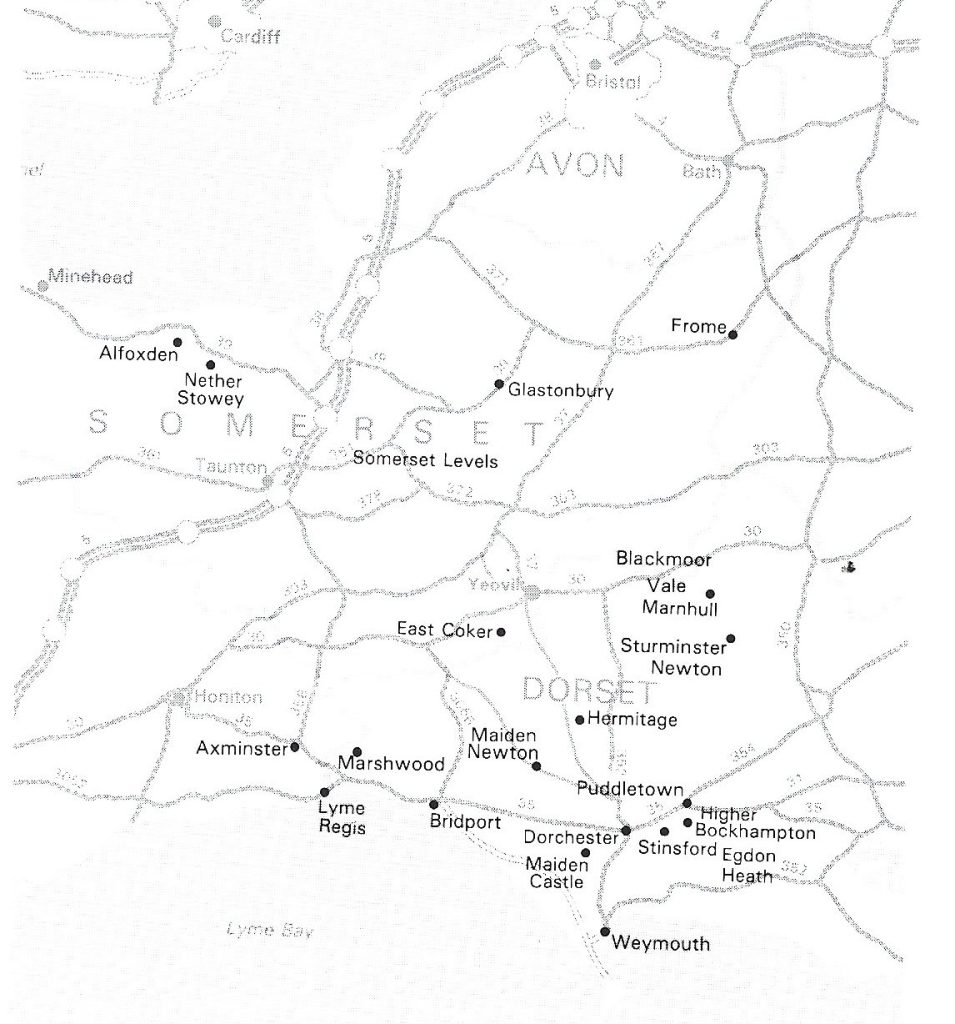

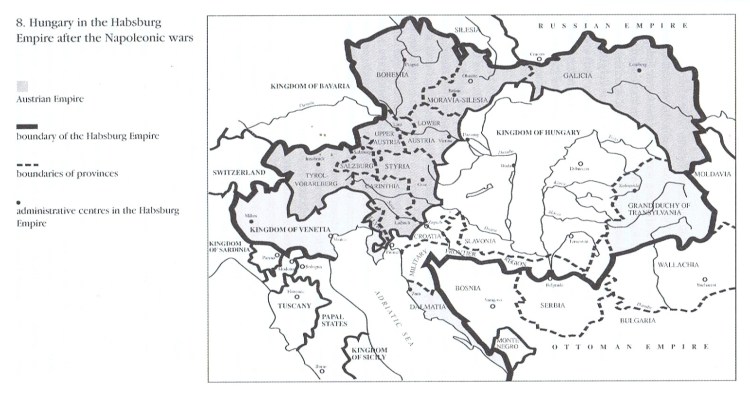

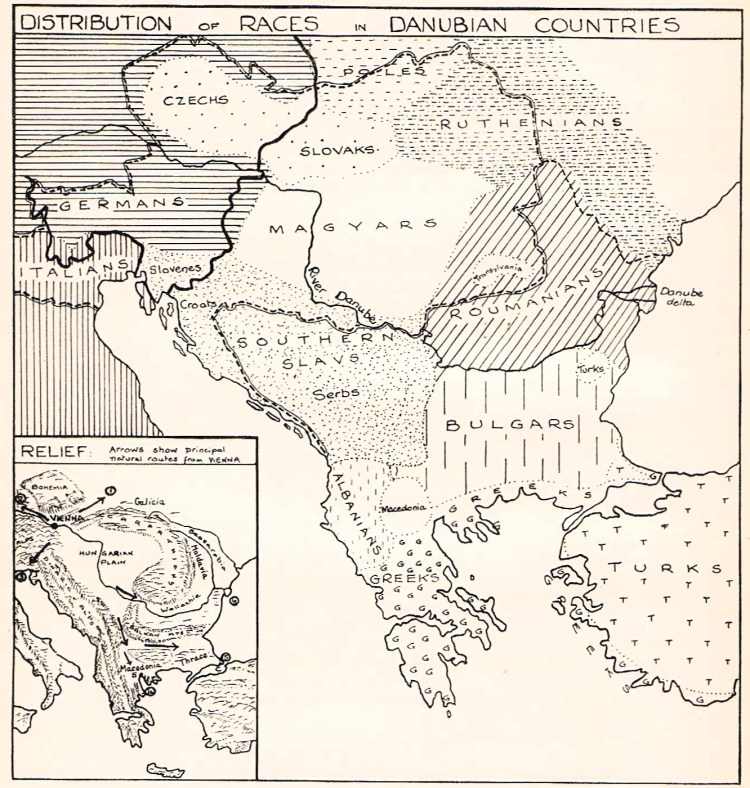

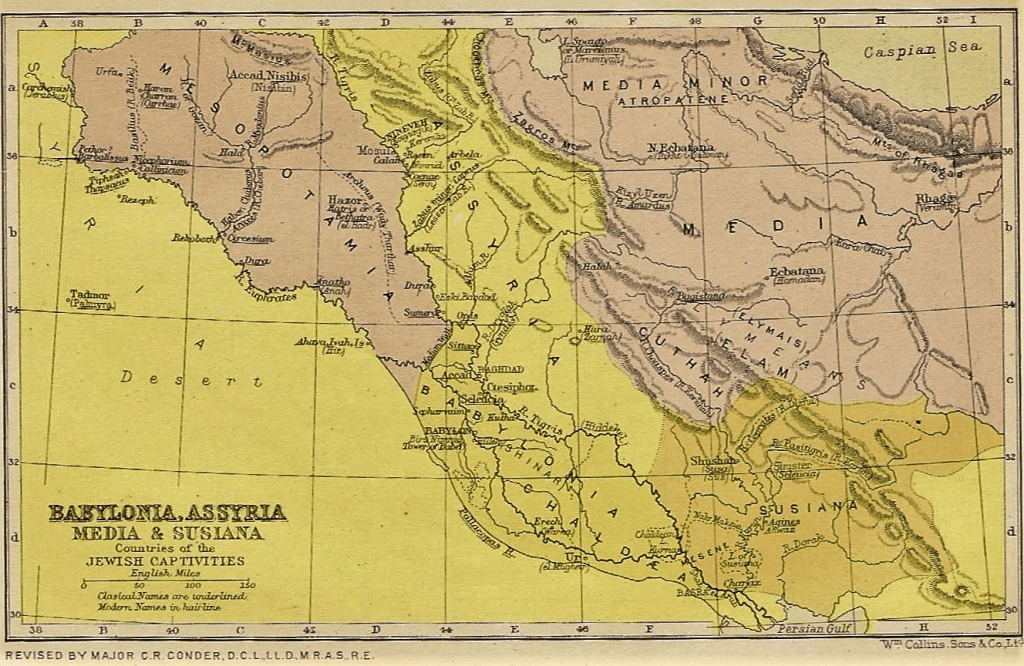

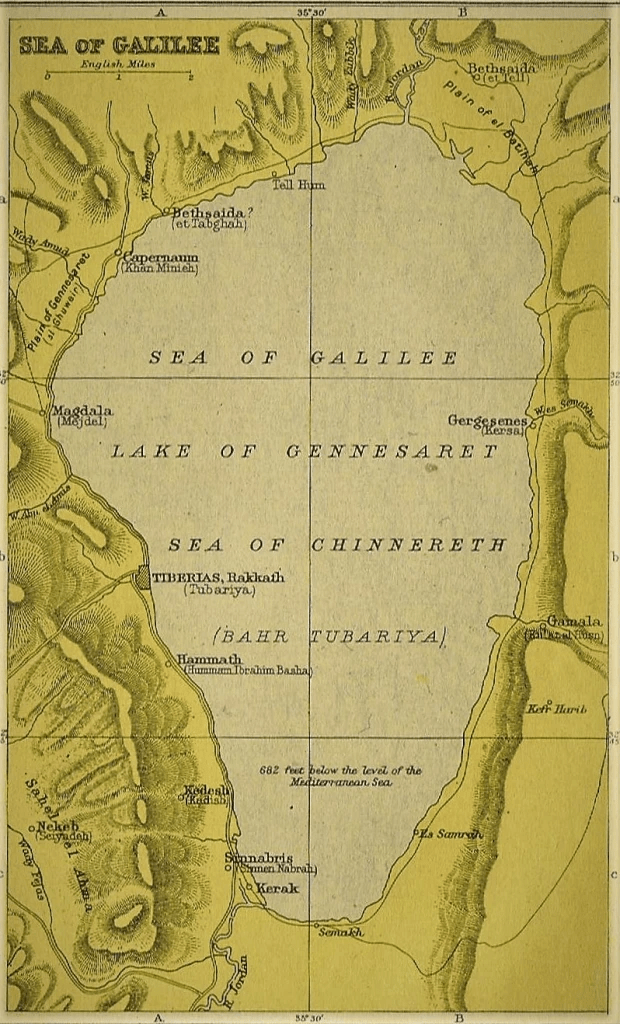

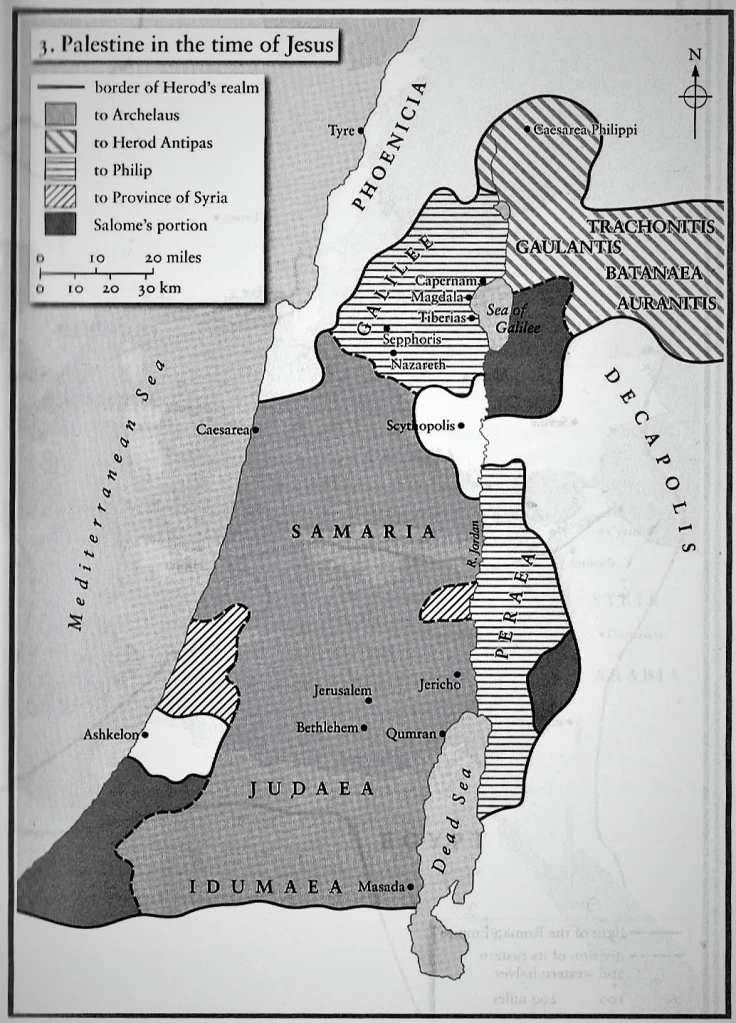

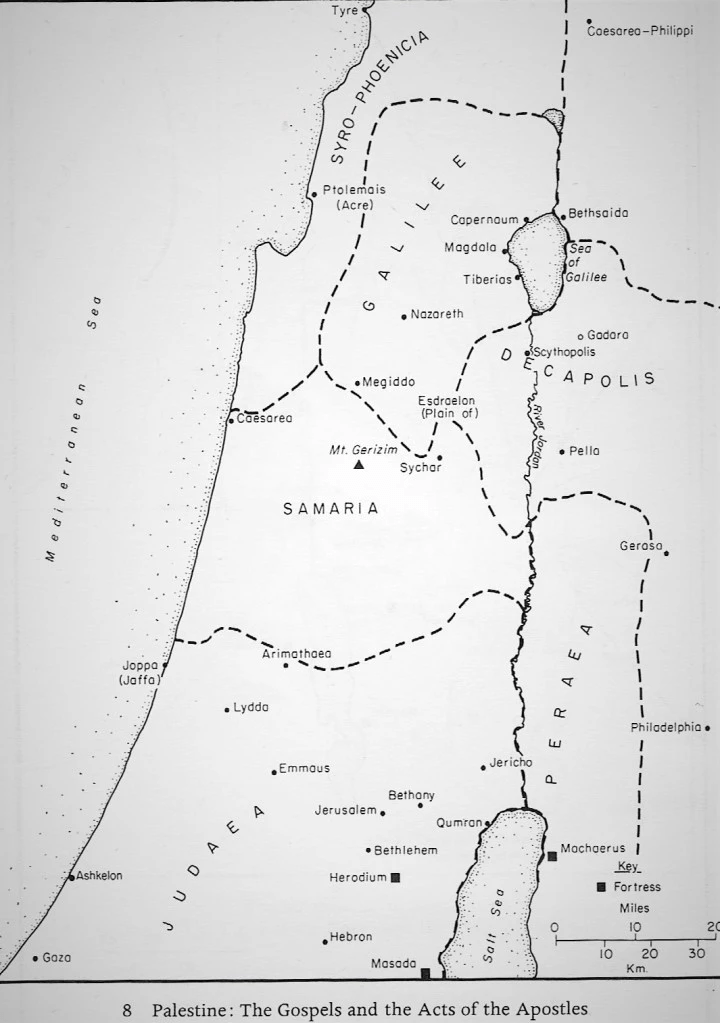

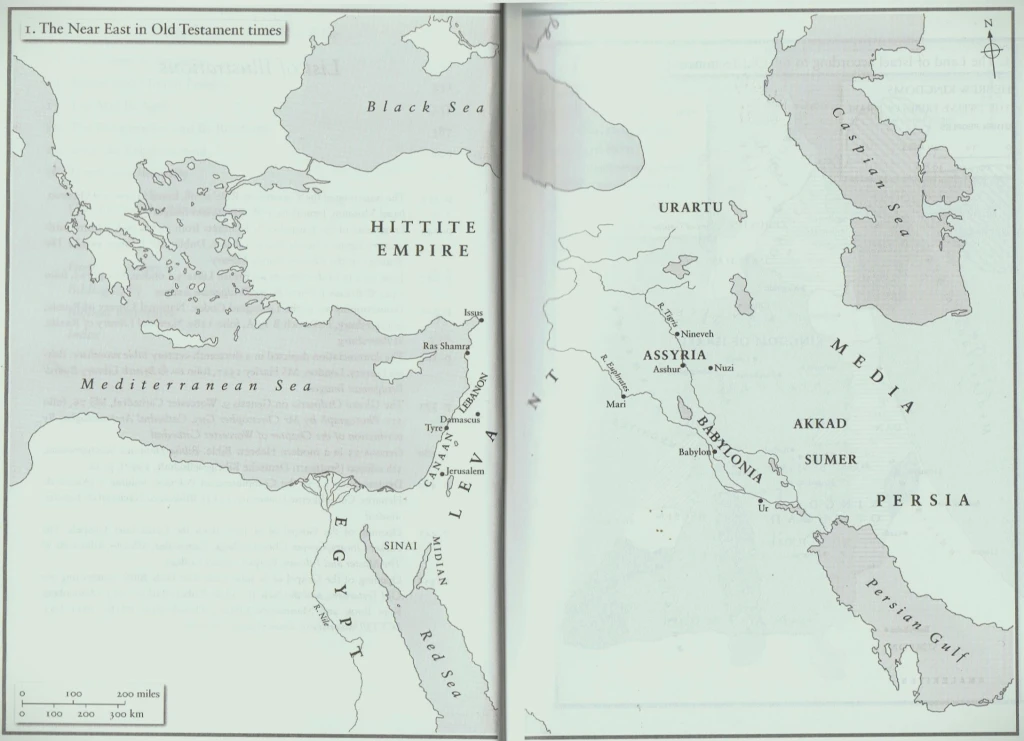

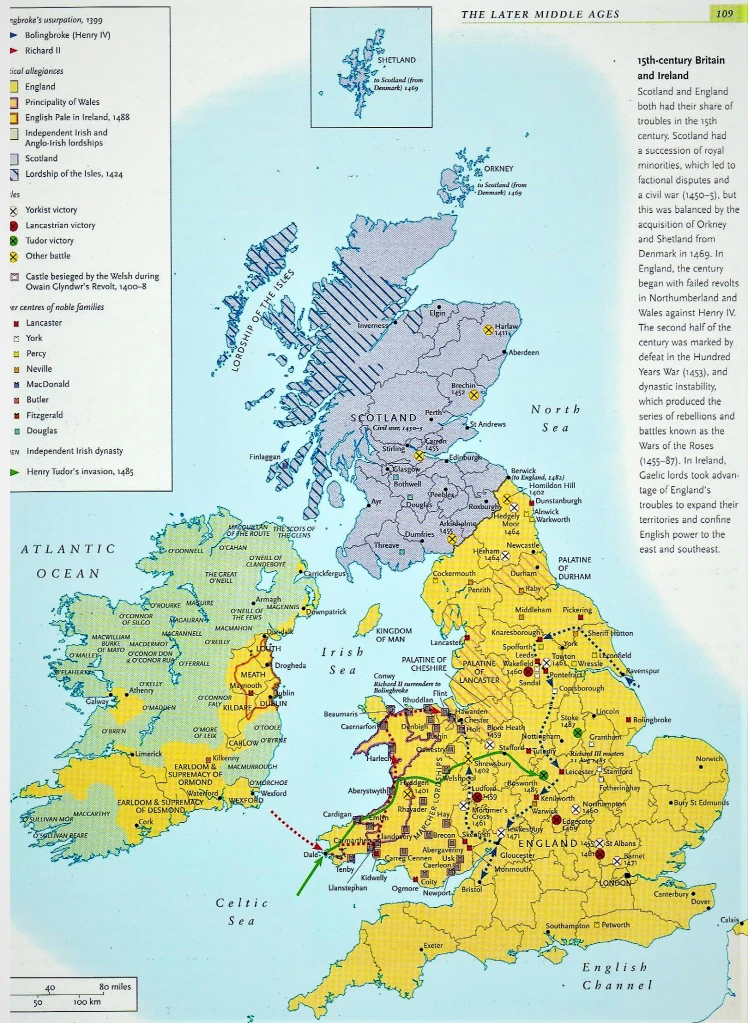

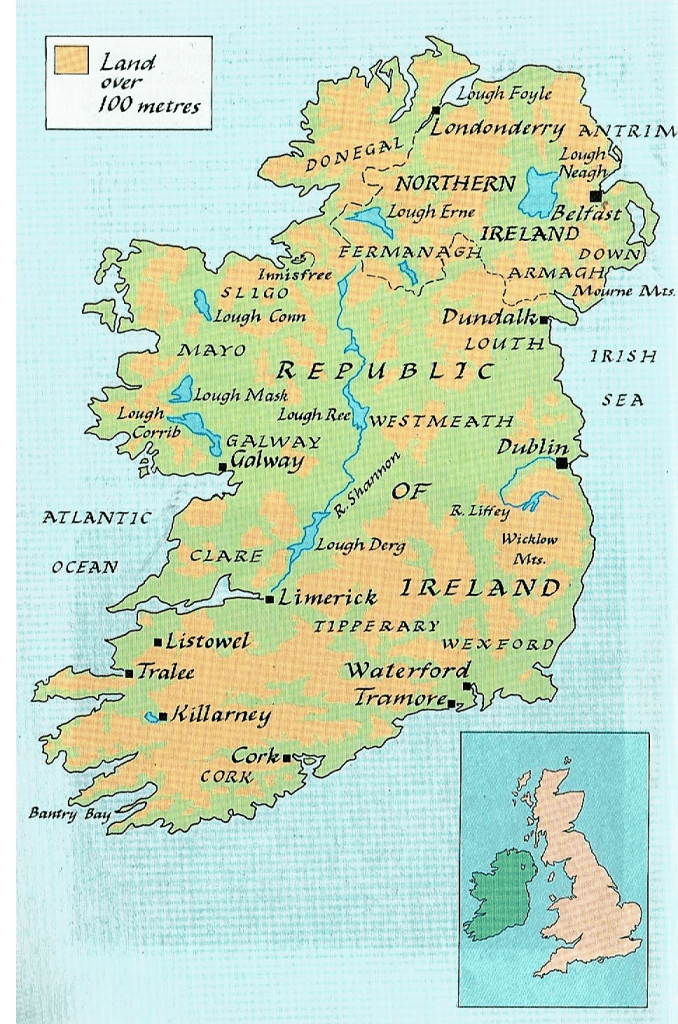

This was particularly the case in the counties in the Southern Danubian countries from the Danube’s bend in Hungary to its delta on the Black Sea. The inset map above illustrates the close relation between the relief of the Carpathian Basin and the distribution of the ethnic groups. The Magyars occupied the Hungarian Plain, the Germans were in the Alpine lands, and the Slavs were in the highlands surrounding the Plain. Further south, on the Macedonian Plain, there was a confused ethnic mix. The River Danube was interwoven with the lives of all these ethnic groups. Complicated as the main map above appears, it is only a simplified representation of the mixture of ‘races’ inhabiting the Danubian area. In each area were peoples other than those shown; only the majorities are shown, and in the case of Macedonia and part of Transylvania even this becomes impossible. In 1789 these peoples were grouped into two empires, either the Austrian (Habsburg) Empire or the Turkish (Ottoman) Empire.

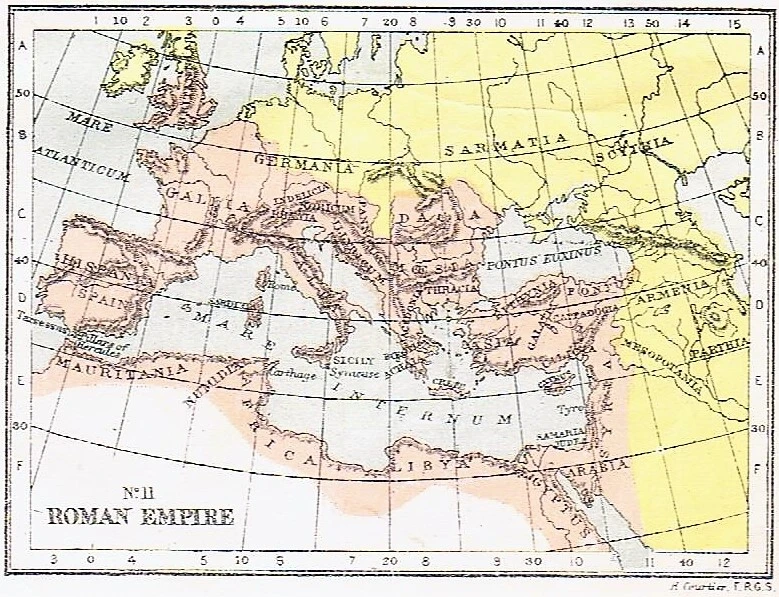

In the Austrian Empire, Germans were predominant in Austria, where the rise of Habsburg power in the German lands had been due to the strategic importance of Vienna, the guard of the Danube gateway into Western Europe against the Turks. When the Habsburgs built up their empire, the other natural routes of expansion were through the Moravian Gate into Poland (Galicia), over the low Alpine passes into Italy; down the Danube through Hungary to the Black Sea, with offshoots towards Salonika and the Aegean, and towards Constantinople (Istanbul) and the Bosphorus. The Magyars to the east of Vienna were only second in importance to the Germans and were given many concessions, including their own Diet. The Northern Slavs consisted of Czechs, who had once been independent in the Kingdom of Bohemia and Moravia, the Slovaks, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), and Poles (in Galicia and Besarrabia, acquired at the first partition of Poland in 1772); the Southern Slavs consisted of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Romanians were also Slavs, but originally of Western European origin.

As the 19th century progressed, the Habsburgs’ Slav subjects began asserting their identity through new national literature, music, and political organisations. Vienna’s difficulties with Budapest over Hungarian rights to self-rule made dealing with other peoples still more complicated. Although Hungarian liberals demanded that the ‘crownlands of St Stephen’ should enjoy autonomy within the empire, they were not happy to extend equal political and linguistic rights to their large Slovak, Romanian, or Serb minorities.

2. The Habsburg Empire, 1849-68:

It has been said that if the Austrian Empire had not existed it would have been necessary to invent it. The Austrian control of this great area brought together many peoples whose interests were bound together by the Danube, including many Jewish people and some Muslims. Communities of Turks were scattered throughout the empire, and Macedonia contained Greeks, Bulgars, Albanians, Serbs, and Turks. Throughout the nineteenth century, the various Slavic peoples sought to challenge or overthrow the Austrian authorities and set up separate national states. The weakness of Austria after the 1866 war with Prussia compelled Vienna to give ‘equality’ to the Magyars, but left the Slavs unsatisfied. The Serbs and Romanians within the Austrian empire wished to join those without. For the rise of the nations in the Balkans, see the maps below.

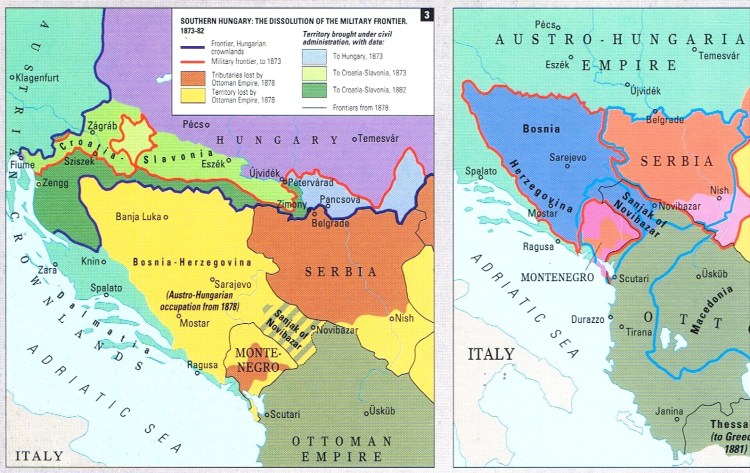

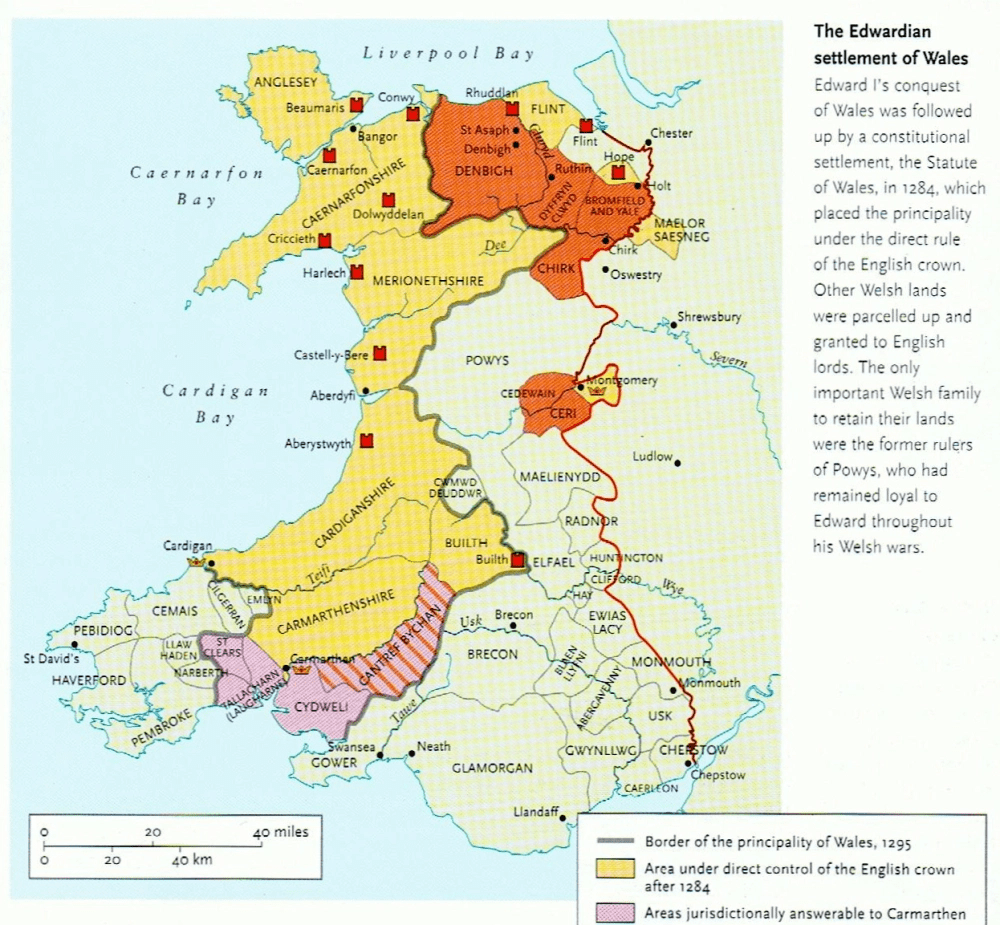

3. Southern Hungary – the Dissolution of the Military Frontier, 1873-82:

In 1789, the Mohammedan Turks had possessed loose control over a range of Christian peoples – Greeks, Bulgarians, Serbians (more numerous than in Austria), Romanians, and Albanians. The border between Christian Europe and the Muslim Ottoman Empire – the Military Frontier – was one of the great political fault lines of Europe. It was established by the Habsburgs in Croatia in the mid-16th century to guard the Habsburg lands against Ottoman incursion and then greatly expanded after 1699 following the expulsion of the Ottomans from most of Hungary by Prince Eugene. By the mid-19th century, with the Ottoman Empire in terminal decline, Hungarian demands for the return of the frontier lands to civilian administration increased and from 1873 the Military Frontier was accordingly parcelled out to Hungary and Croatia-Slavonia.

By 1882, the “Military Frontier” had been put under civilian administration. Mutual fear of disintegration kept Vienna and Budapest together after 1867, despite petty disputes about the title of the common army (Imperial or Royal according to where it was stationed) and the language of command.

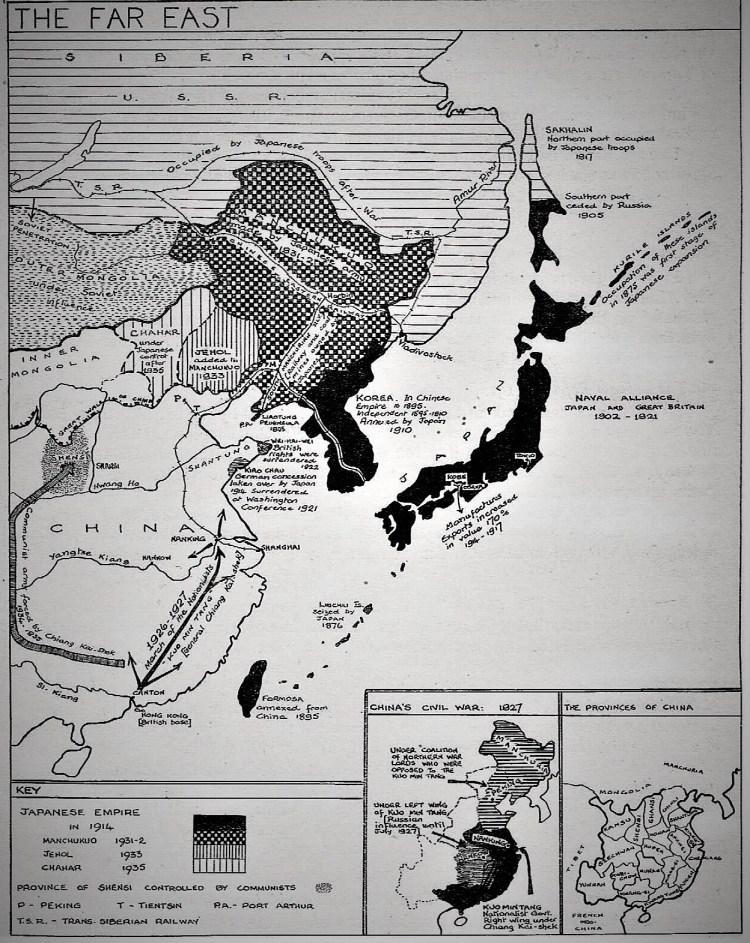

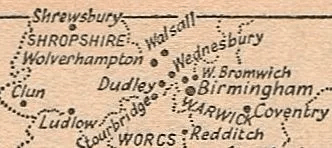

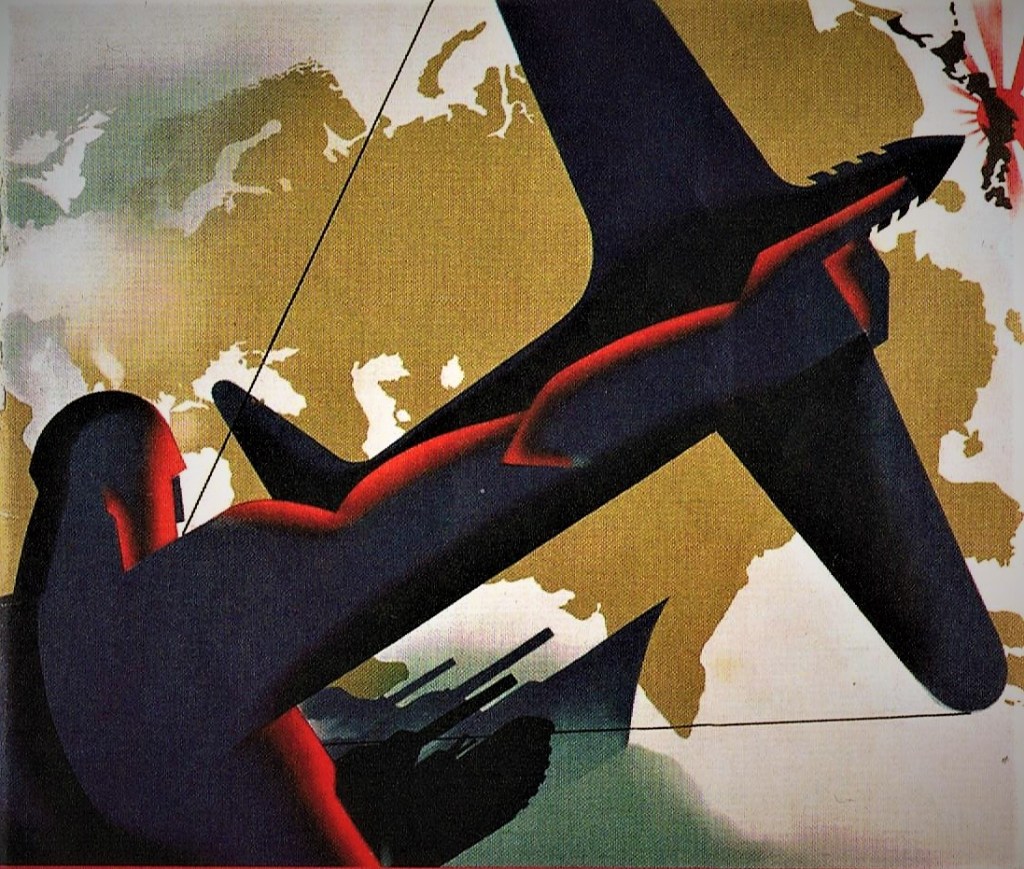

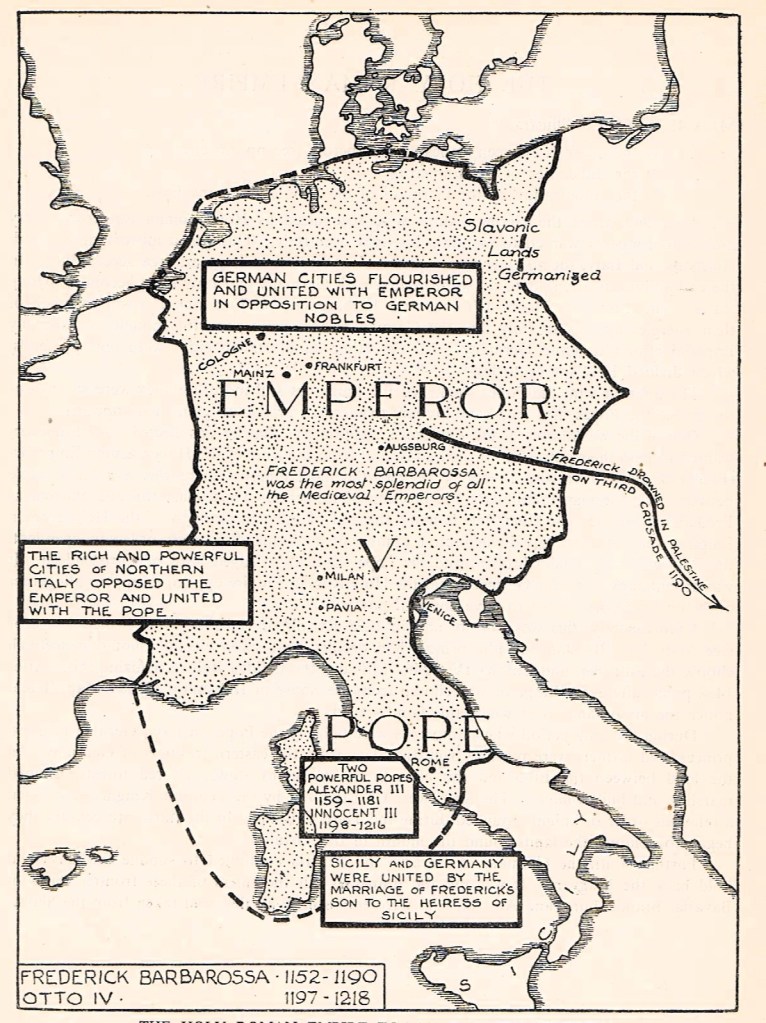

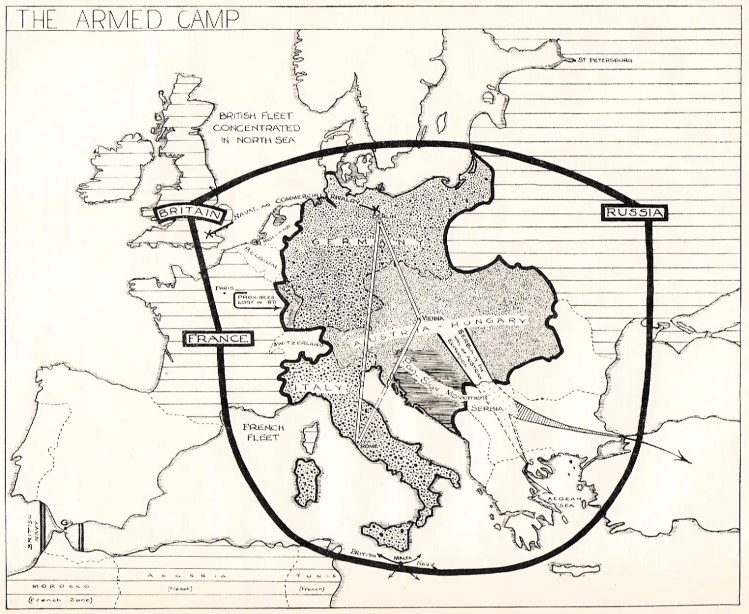

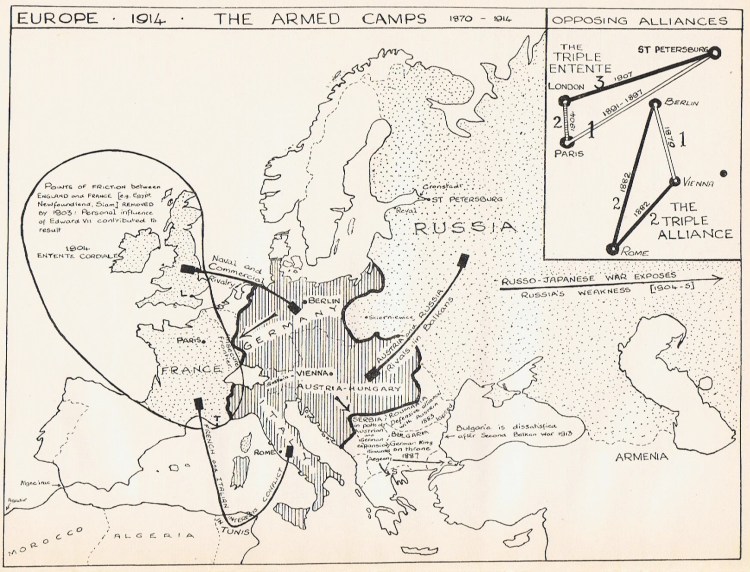

4. Sketch-Map Histories – The Armed Camps:

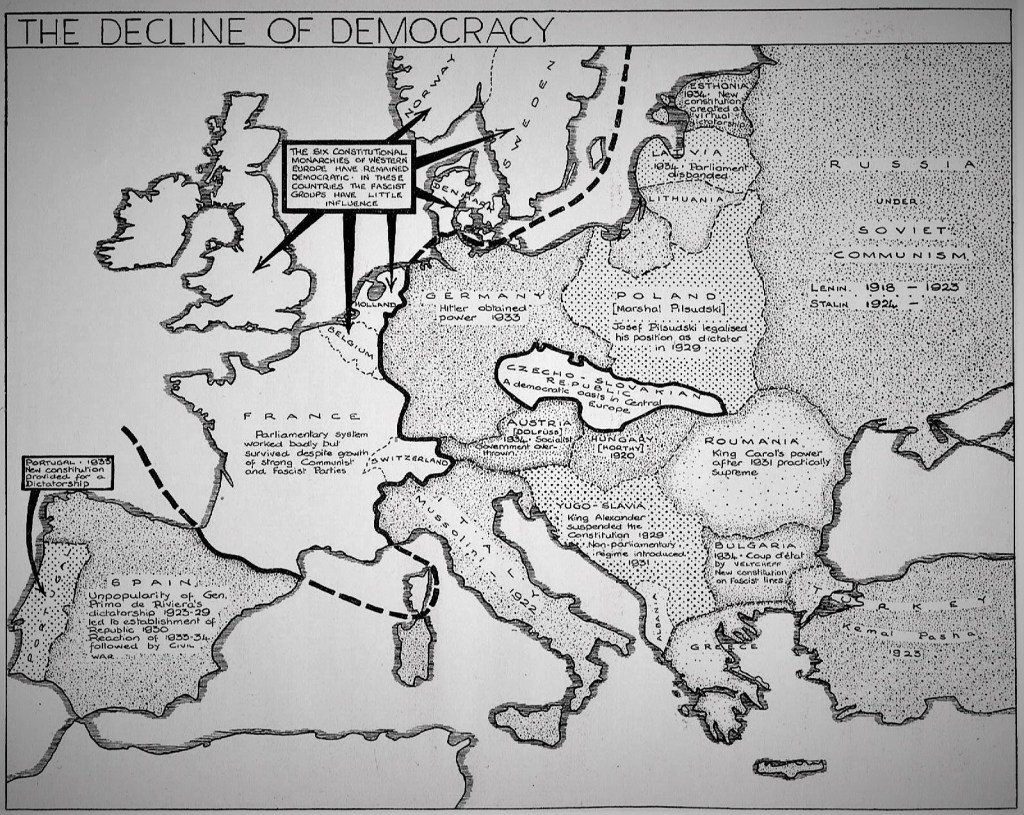

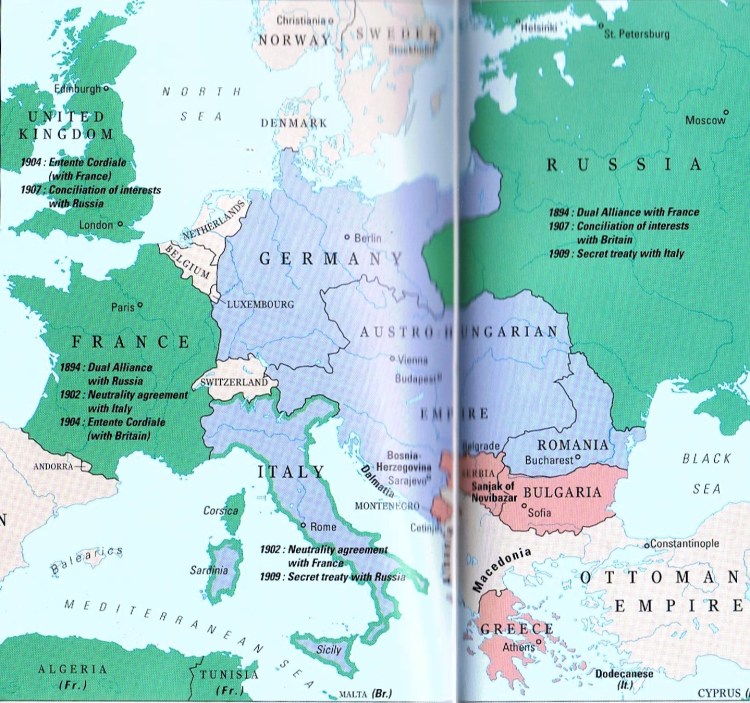

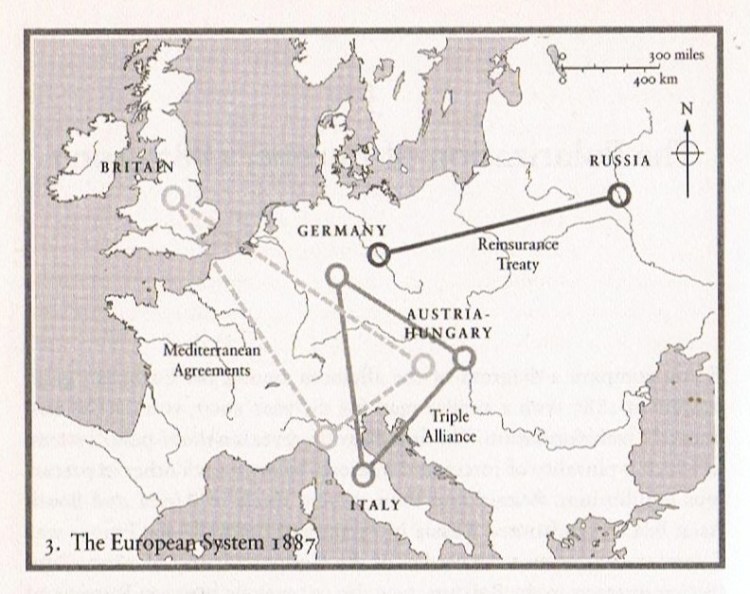

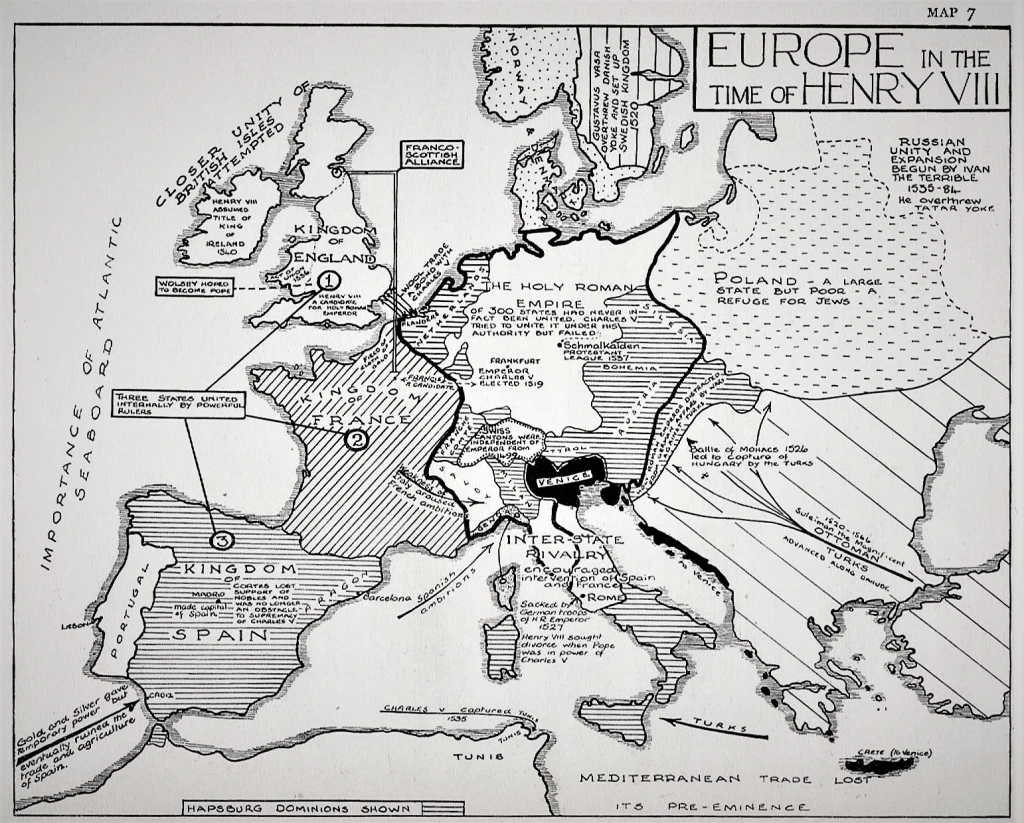

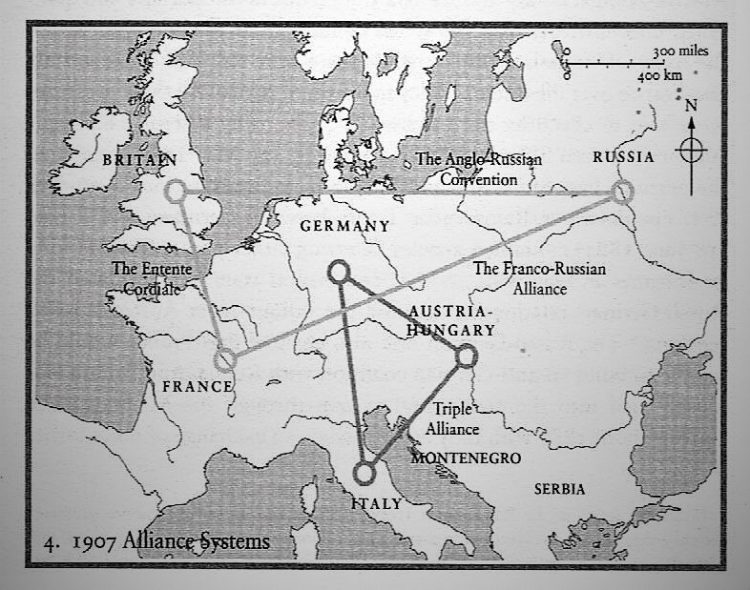

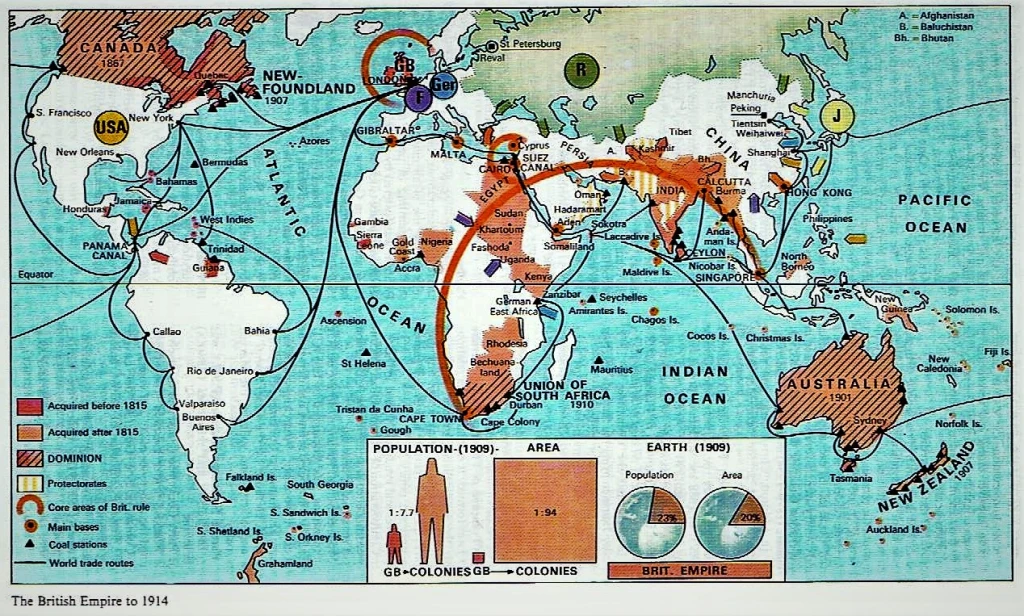

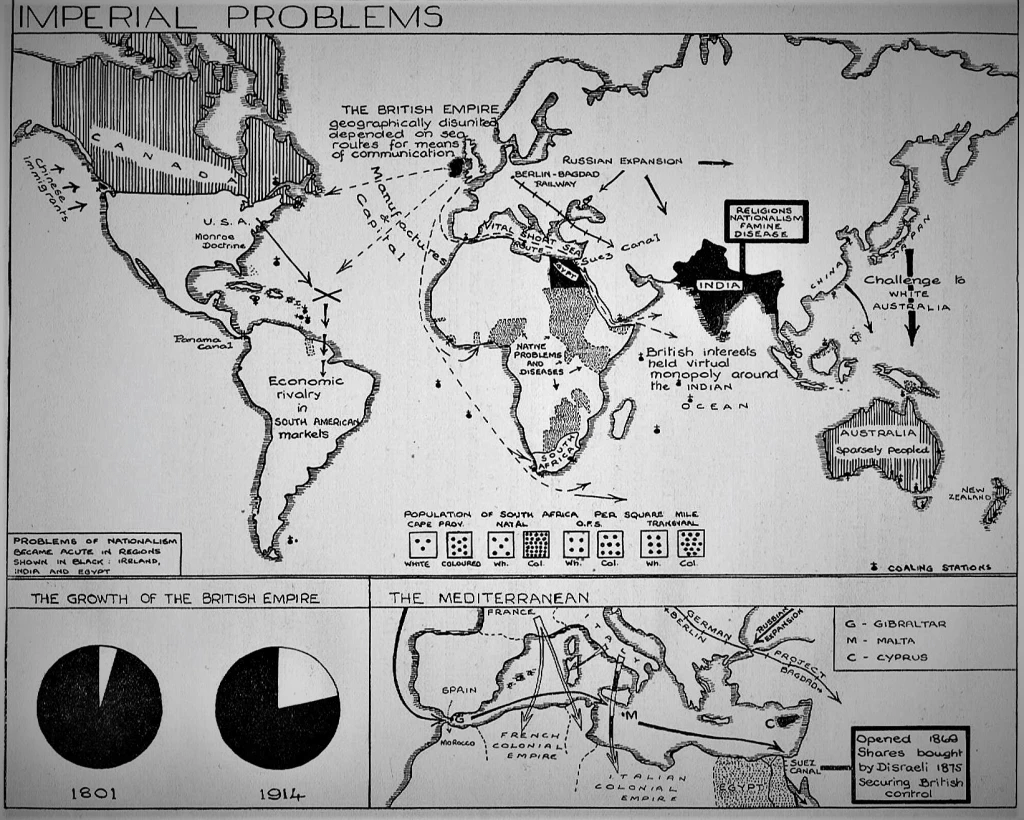

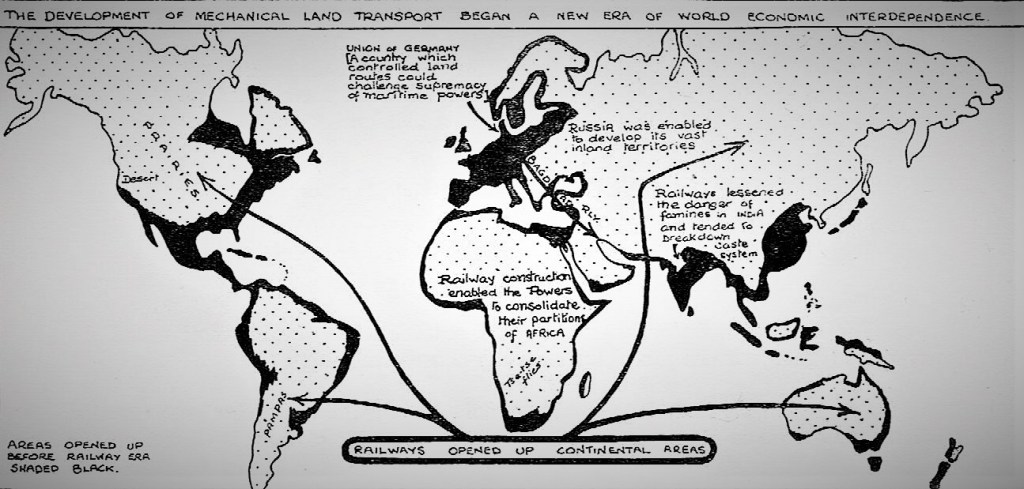

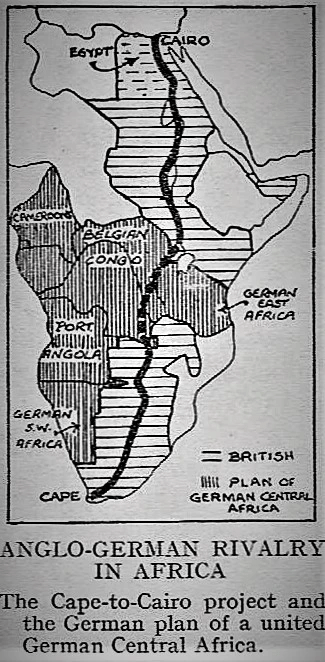

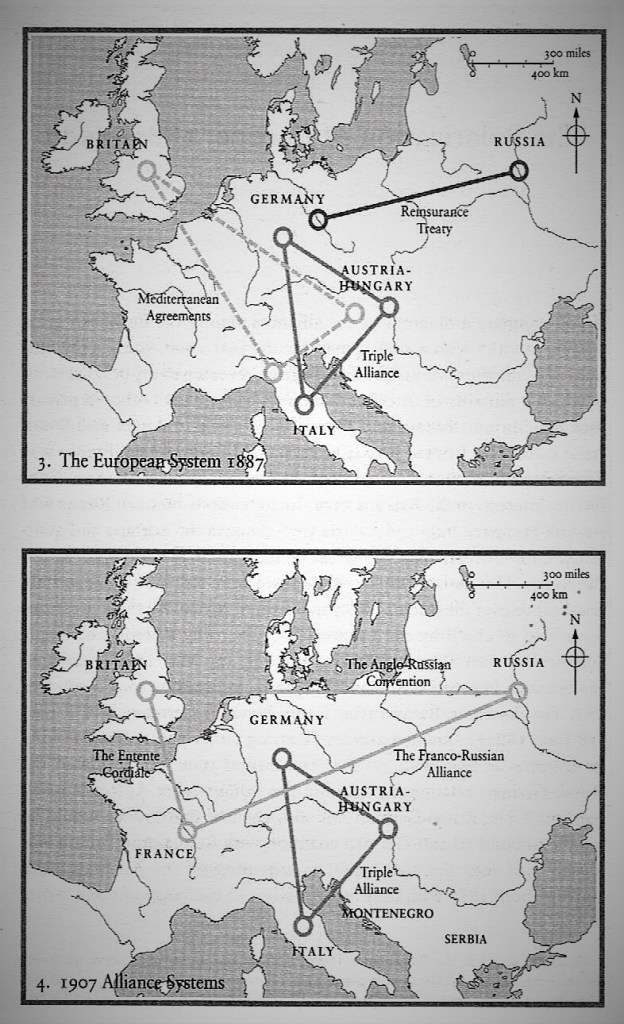

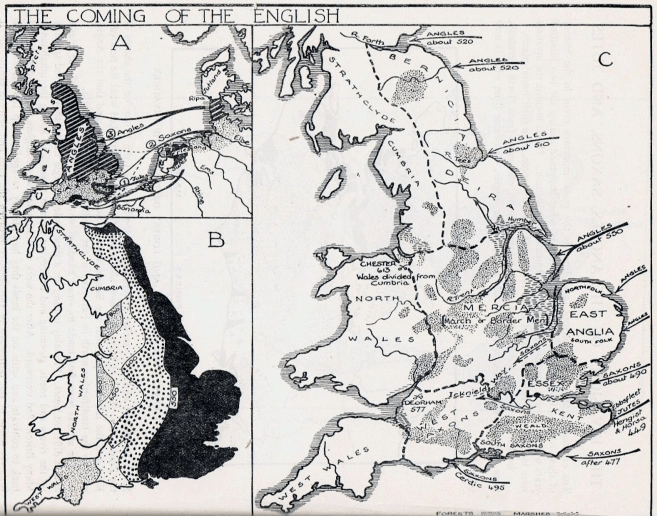

By the last decade of the nineteenth century, dynastic ties and fear of unrest had served to draw together the Great Powers to promote an essentially stable order across Europe through a multifaceted series of diplomatic alliances and alignments. This was the apogee of the European nation-state system. But whatever its apparent stability, the system was permanently threatened by Germany’s growing primacy among the Continental powers and by instability in the Balkans. One of the most striking characteristics of pre-world war Europe was its division into two rival alliances of opposing powers.

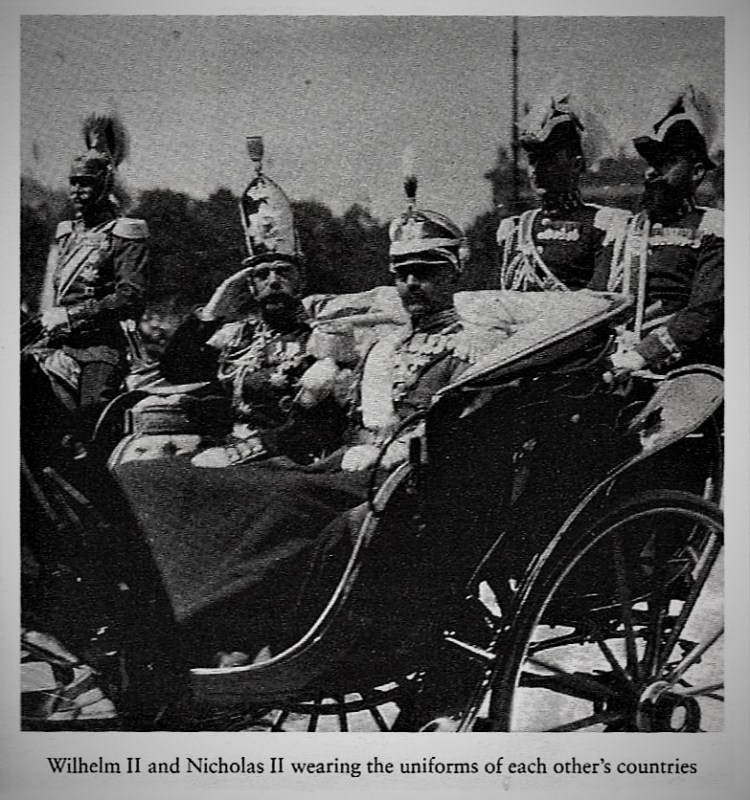

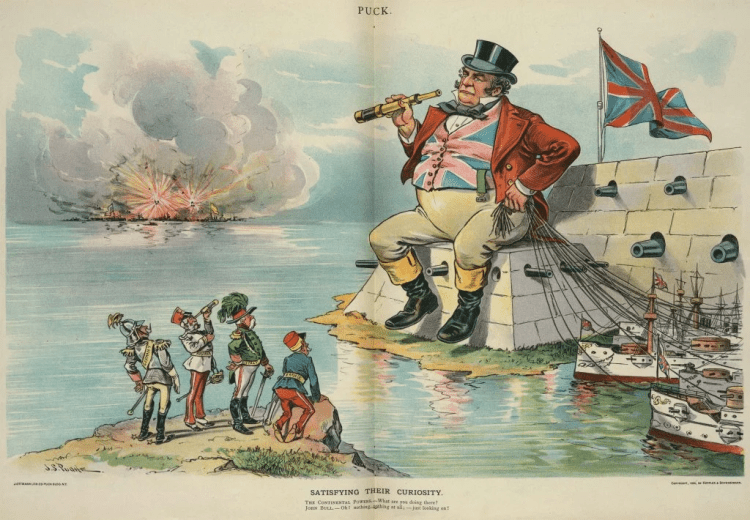

By 1914, Austria-Hungary was Germany’s only reliable ally. In the crisis after the murder of Archduke Ferdinand, Germany could not afford to abandon her even at the risk of a general European War. Furthermore, if war did come, the Kaiser’s generals wanted it sooner rather than later: the German army was increasingly certain that could defeat both France and Russia simultaneously.

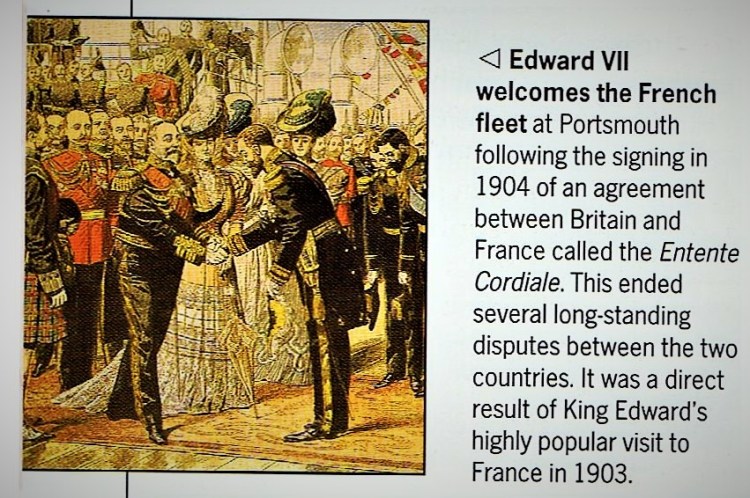

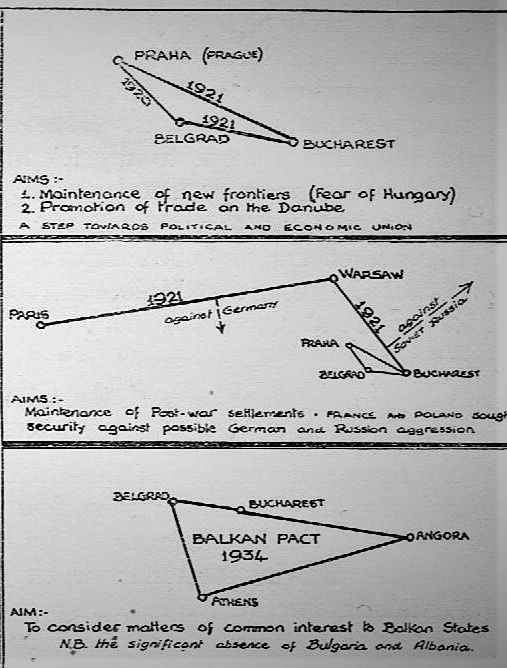

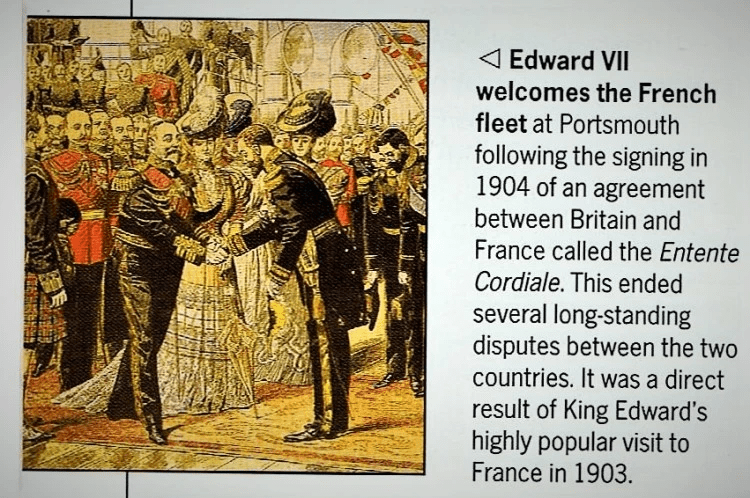

The Dual Entente of 1894 between France and Russia came about after Russia and France found themselves isolated while Central Europe was united in the Triple Alliance. By then, Germany’s expanding military strength caused France and Russia to become nervous allies. Overcoming a dislike for each other’s forms of government, they came closer together between 1894-1904 for mutual defence against their common rivals.

The Entente Cordiále of 1904 marked a dramatic shift in Great Britain’s thirty-year policy of splendid isolation from continental conflicts and alliances: at the beginning of the twentieth century, it appeared dangerous to remain friendless in Europe in the light of the rapid growth in Germany’s naval power. Imperial issues had added to Britain’s estrangement from both Russia and France for a century or more. At first, the obvious partner for Britain had seemed to be Germany, but the Kaiser’s ‘Great Navy’ policy posed a threat to Britain as a naval power. This forced the British into the arms of France. Imperial issues were settled amicably and an understanding with both France and Russia, The Triple Entente was reached in 1907. This guaranteed mutual defence in the case of a German attack. In Berlin, these measures of alleged self-defence were viewed more as a strategy of ‘encirclement’ of Germany. Facing declared enemies to the west and the east, Germany drew closer to Austria, whose strained relations with Russia finally cracked with the annexation of Bosnia-Hercegovina in 1908.

These alliances, though defensive in aim, created suspicion and uneasiness and led to the piling up of armaments. Moreover, a quarrel between any two states involved the rest; the dispute between Russia and Austria-Hungary tended to bring about a dispute between France and Germany. Meanwhile, no one could agree on the fate of the Christian populations of the Balkans beyond a pious regret that they should have to remain under Muslim rule. However understandable the failure to grasp the Balkan nettle at Berlin in 1878, the problems of the region’s numerous ethnic, nationalist, religious, and imperial rivalries were to fester unchecked into the twentieth century to everyone’s disadvantage.

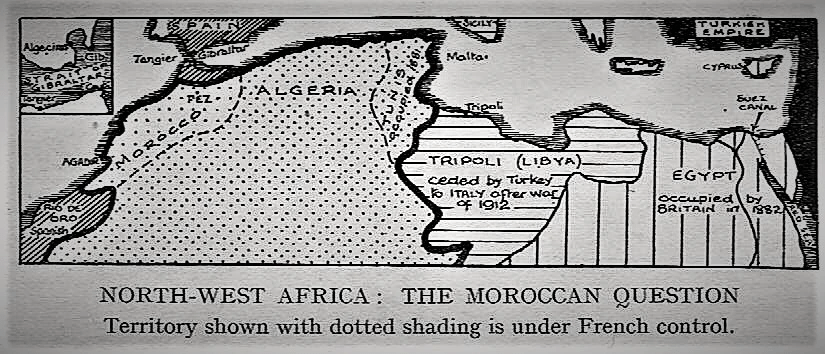

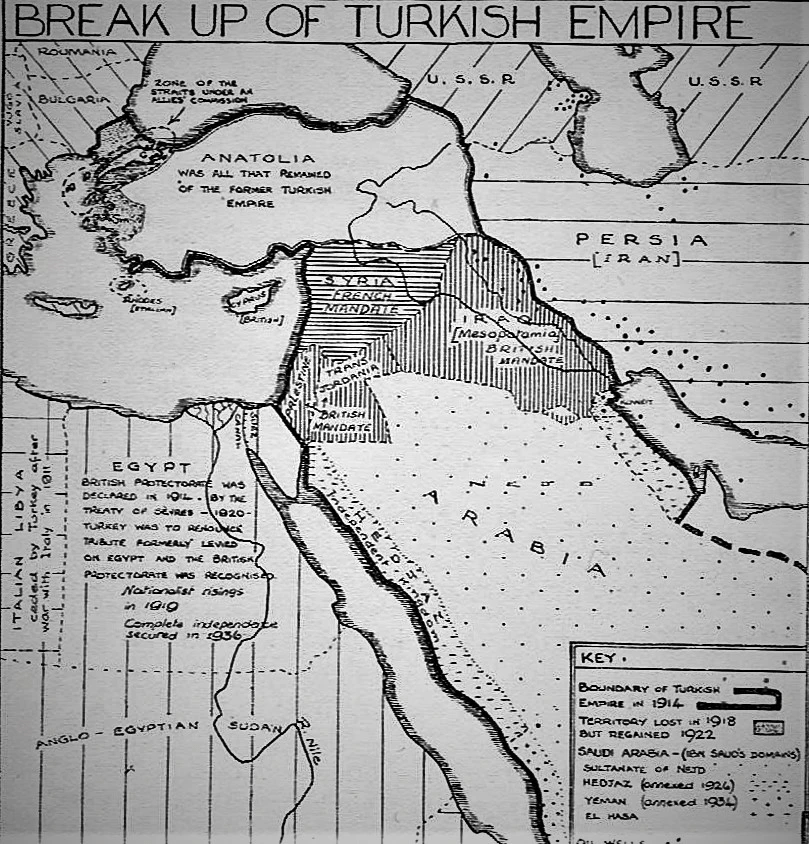

After 1901, when Germany had finally rejected British ‘overtures’, successive crises arose which heralded the approaching Great Power struggle. The crises concerned the Franco-German rivalry in North Africa and the Russo-Austrian rivalry in the Balkans. The chief storm centre in Europe was in the Turkish Empire, growing steadily weaker and forced to rely more and more upon Germany, the Sultan’s new ally. The Kaiser had shown his interest in Turkey in 1898 by his visit to the Sultan when all of Europe was horrified by the massacre of its Armenian subjects and by his announcement to extend German protection to the Muslim peoples of the Middle East. He had gained concessions for railway development under German direction – a prelude to his dream of a Berlin-Baghdad railway. This Drang Nach Osten conflicted with the aspiration of the Balkan peoples who endeavoured to secure their independence.

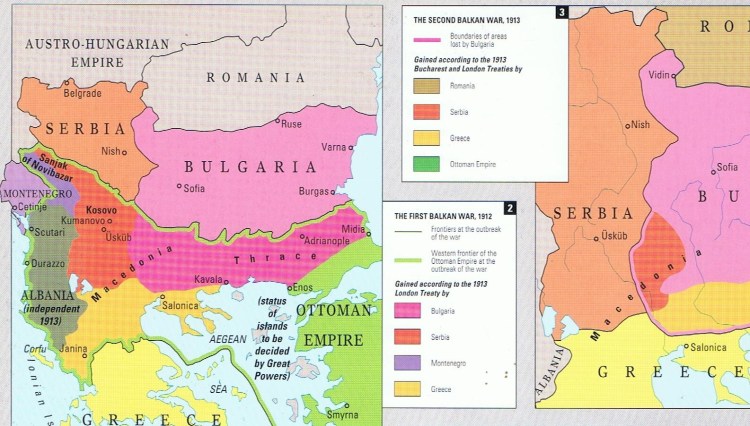

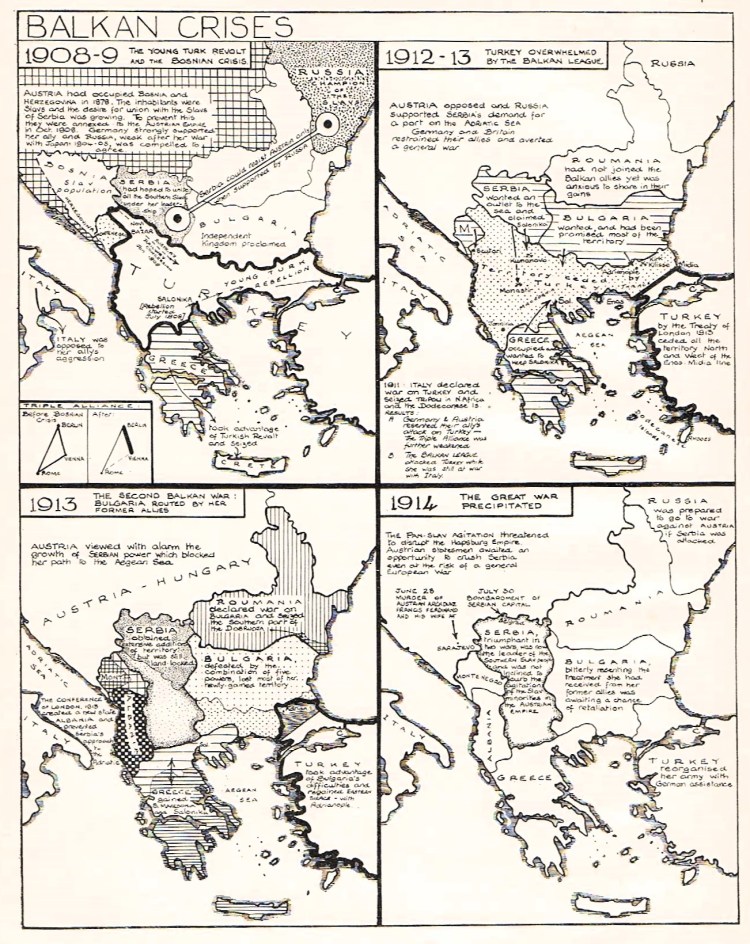

5.) The Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913:

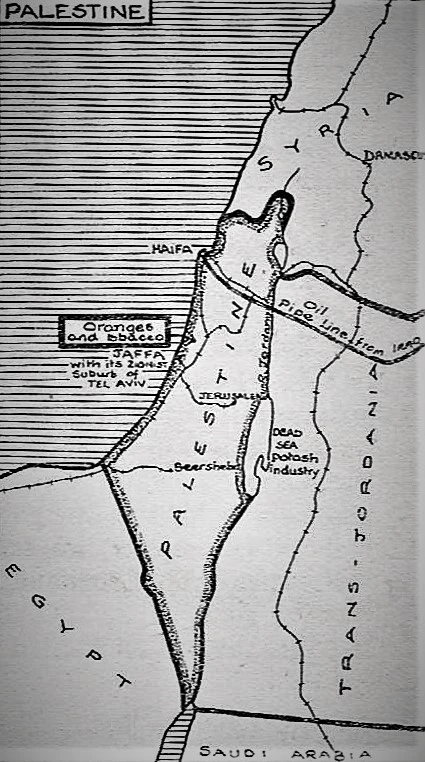

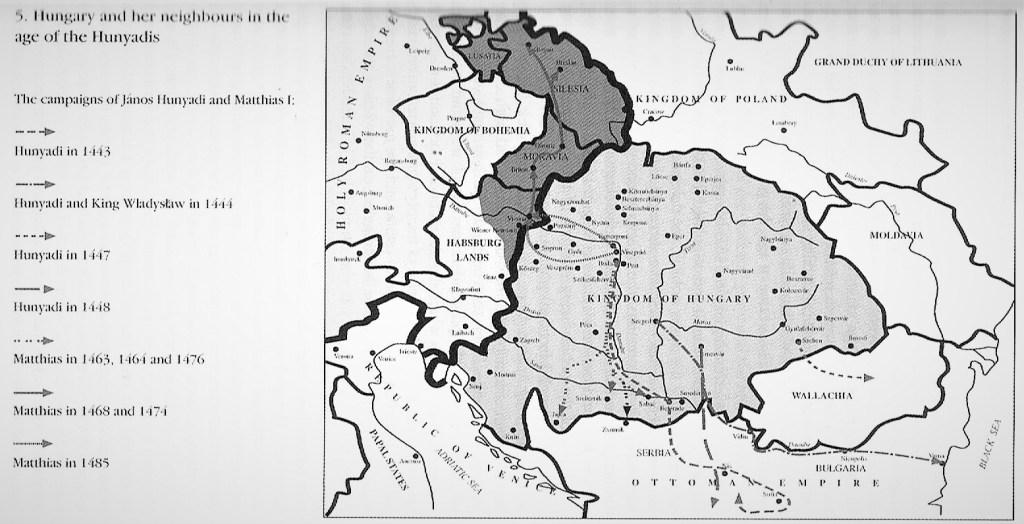

The ‘new’ Balkan states were united only by their hostility towards the Ottoman Empire, which in 1912 still held Albania and Macedonia. Taking advantage of its weakness, Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria formed a ‘Balkan League’ which attacked and defeated Turkey. This First Balkan War of 1912 gravely threatened the interests of Germany and Austria-Hungary, but the Great Powers agreed that the war should be kept localised. The anti-Ottoman alliance hoped to divide the Sultan’s European territories between them, and a conference was summoned in London in 1913 to settle the division of the territory which Turkey had been forced to surrender. It was mediated by the Great Powers and chaired by Britain, but it left everyone dissatisfied. The map above (left) shows the conflicting claims of the successful Balkan allies.

The great Aegean port of Salonica was coveted by all three victors. In the event, the Greek army had reached it just hours before the Bulgarians, who were left resentful when the London Conference confirmed that it as a Greek possession. But Bulgaria was compensated with a large tract of land from the Black Sea to the Kavala on the Aegean, including Adrianople. The province of Macedonia, with a mixed population of Slavs, Turks, Jews, and Greeks, was claimed by all three states, each with varying degrees of justice and all indifferent to the wishes of its inhabitants. The conquest by the three nations confirmed its division between Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece. The Treaty of London also confirmed the creation of the independent principality of Albania, a development resented by both Greece and Serbia. Serbia wanted a port on the Adriatic at Albania’s expense and feared moreover that an independent Albania would make her substantial Albanian minorities in Kosovo and Macedonia restive. Greece laid claim to northern Epirus (i.e. southern Albania), basing its claim on the Greek Orthodox community there. Threatened by hostile neighbours, Albania was pushed into looking first to Austria-Hungary and then to Italy for protection. Austria, supported by Germany, intervened to prevent Serbia from securing access to the sea through Albania. This was the second successful attempt by Austria to curb the Pan-Slav movement. War was averted only through the influence of Germany and Britain.

However, resentment at the Treaty of London quickly developed into a new war. Serbia was compensated by accession to territories in Macedonia at the expense of Bulgaria, who objected and reopened the war, this time against her former allies and a ‘new’ rival to the north, Romania. Determined to right the wrongs done to it in London, Bulgaria attacked its erstwhile allies, Greece and Serbia. Bulgarian military optimism was soon shown to be misplaced. The Greeks and Serbians, aided by Romania and Turkey, who swiftly realised the opportunity the Bulgarian offensive presented, had little difficulty in repulsing it. Bulgaria was overwhelmingly defeated by the new alliance against it, and Serbia annexed large territories at her expense. The greatly enlarged and strengthened Serbia aroused the deep resentment of Austria. Greece kept Salonica and took western Thrace. Resentful Bulgaria was confined to a barren stretch of the Aegean coast while Turkey recovered Adrianople in Thrace, maintaining a foothold in Europe. Romania, a non-combattant in the first Balkan War, received southern Dobruja for her efforts in the second. Once again, only Germany’s restraining influence, combined with Italy’s refusal to cooperate prevented an immediate attack. Instead, the Central Powers waited for a better reason to intervene to curb Serbia’s ambition.

6.) The Eve of the First World War – a Summary:

The boundaries between the Great Powers changed little in the century after the Congress of Vienna (1815). Germany, although now unified, Austria-Hungary, and Russia still shared largely the same frontiers established at Vienna, and most contemporary observers could be forgiven for regarding them as permanent. But, in practice, the emergence of small states on the periphery of the Powers, allied to tensions created by conflicting aspirations for autonomy and independence on the part of the many ethnic groups within the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires, marked the beginning of a process that threatened the territorial integrity of these empires.

Whatever its problems with nationalism, Russia at least had a majority ethnic group. Austria-Hungary lacked even this. The ‘Magyars’ made up half the population of the Kingdom of Hungary, the other half were Slovaks, Romanians, Serbs, and Croats as well as two million Germans. In the Austrian part of the empire, Germans amounted to only 35% of the population. Czechs, Poles, Slovenes, Italians, and several smaller groups made up the remainder. The very principle of national self-determination which had justified the unification of Germany was a threat to its Habsburg ally.

It was in the Balkans that nationalist aspirations were to prove the most volatile. Newly independent Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece all saw the decline of the Ottoman Empire as an opportunity to extend their territories at the expense of the Turks. At the same time, Austria-Hungary and Russia both sought to increase their influence in the region. With Britain’s abandonment of its role as the protector of the Ottoman Sultan, a policy originally intended to contain Russian ambitions, the way was left open for Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece in 1912 to attack the Turks. Dividing the spoils proved harder, as the maps above have demonstrated. More threateningly still, however, was the involvement of Austria-Hungary and Russia. While the former feared the destabilising effect Serbia might have on its large South Slav population, especially in Bosnia-Hercegovina, the latter was determined to resume her role as protector of Orthodox Christians in the region – if necessary against Catholic Austria-Hungary rather than Muslim Turkey.

With Austria-Hungary and Russia members of the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente respectively, their rivalry in the Balkans increasingly threatened to suck the whole of Europe into conflict. Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against Serbia in July 1914 following the Serbian-sponsored assassination in Sarajevo the previous month was the spark that lit the conflagration. Russia ordered a general mobilisation, and Germany responded in kind on 1st August, then declared war on Russia and France three days later. The following day, the Germans invaded Belgium, determined to smash the Triple Entente by drawing Britain into the war.

The Aftermath of the First World War:

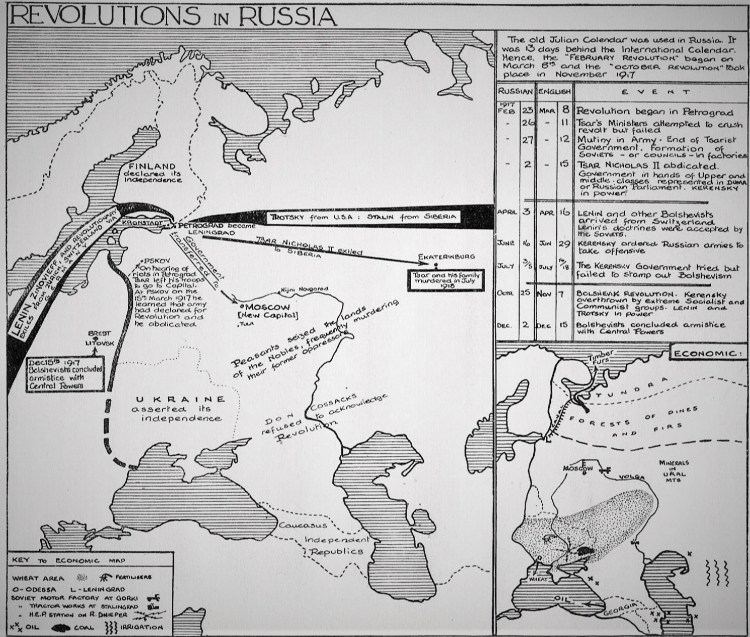

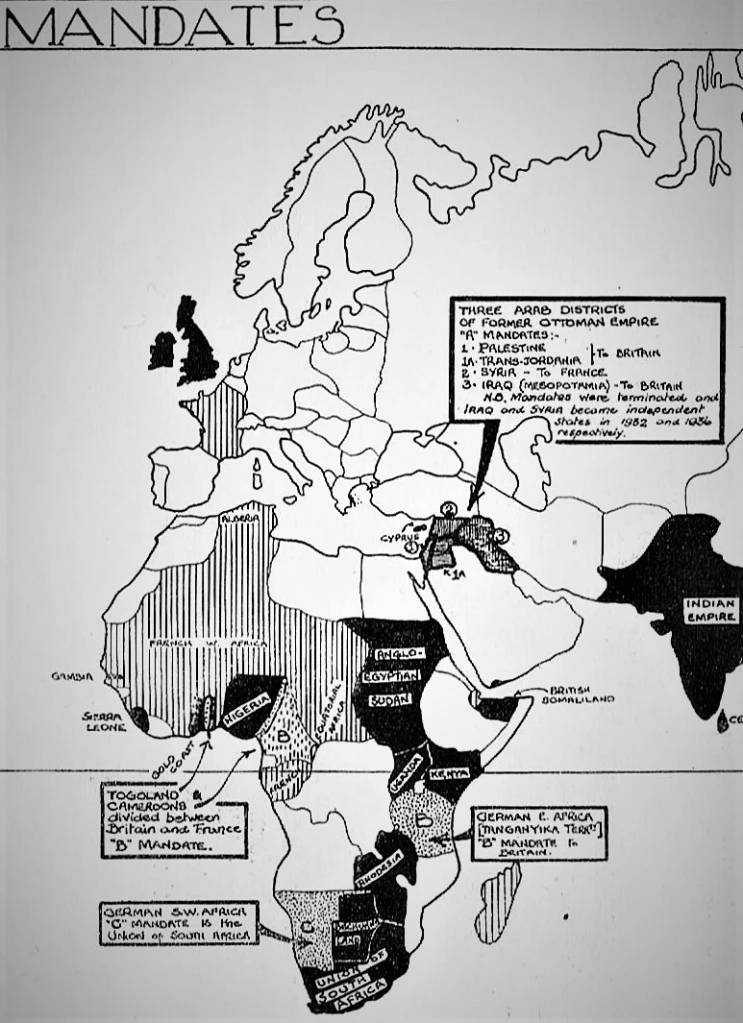

Despite the defeat of Germany and her allies in the autumn of 1918 and the signing of a string of peace treaties in Paris between the victorious allies and the defeated states in 1919 and 1920, it was several years before the boundaries of the new Europe were clearly established. Revolution and civil war plunged Russia, Germany, and much of what had been Austria-Hungary into chaos. The Europe that emerged was radically different. Russia and Germany had shrunk dramatically; the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires had disappeared, and a host of smaller states had appeared. In Russia, a communist government now ruled in place of the Tsar. The civil war that followed the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia found counterparts in Hungary (1919), as well as in Germany. The Paris Peace Settlement of 1919-20 left every post-war in central Europe with internal problems and potential border disputes. It proved easier to break up multi-national empires than to replace them with ethnically homogeneous states. Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia both had substantial Hungarian minorities, and Romania too had a large Magyar population, concentrated in Transylvania.

Sources:

Christopher Clark (2012), The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. London: Penguin Books.

Norman Stone (2019), Hungary: A Short History. London: Profile Books.

László Kontler (2009), A History of Hungary. Budapest: Atlantisz Publishing House.

Martyn Rady (2020), The Habsburgs: The Rise and Fall of a World Power. London: Allen Lane/ Penguin Random House.

István Lazar (1990), An Illustrated History of Hungary. Budapest: Corvina Books.

Norman Rose (2005), Harold Nicolson. London: Jonathan Cape/ Pimlico.

George Taylor (1936), A Sketch-Map History of Europe, 1789-1914. London: George G. Harrap.

Irene Richards (1938), A Sketch-Map History of the Great War and After, 1914-1935. London: George G. Harrap.

András Bereznay, et. al. (2001), The Times History of Europe: Three Thousand Years of History in Maps. London: HarperCollins.

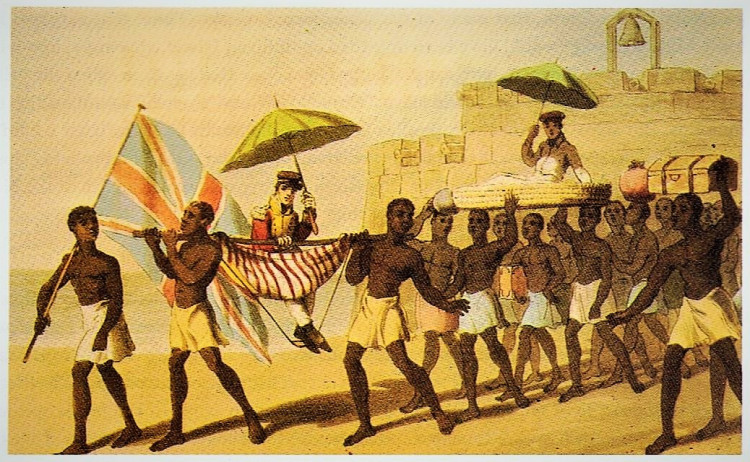

British and slavers, traded up rivers from the coasts in the early nineteenth century.

British and slavers, traded up rivers from the coasts in the early nineteenth century.

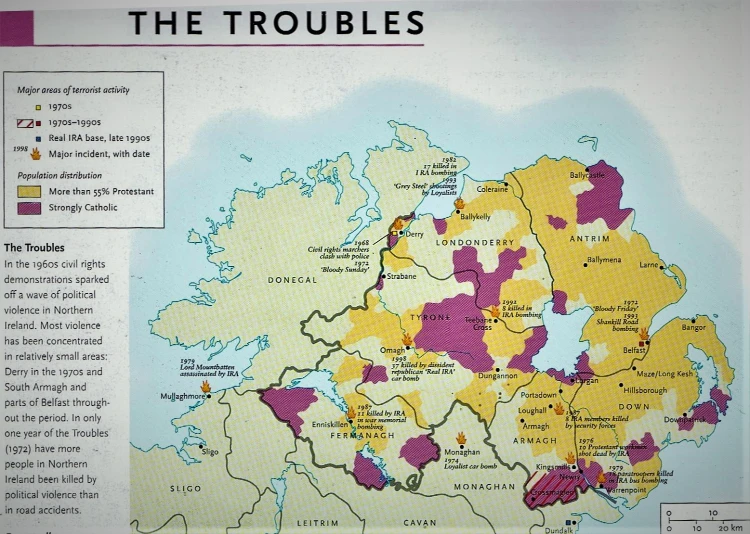

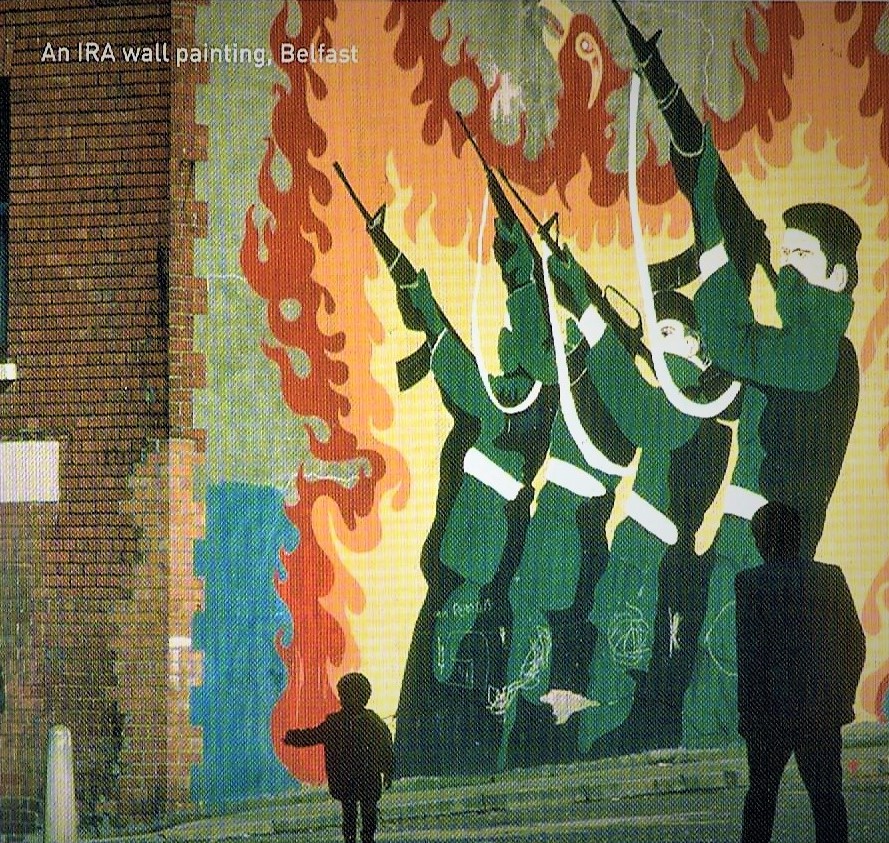

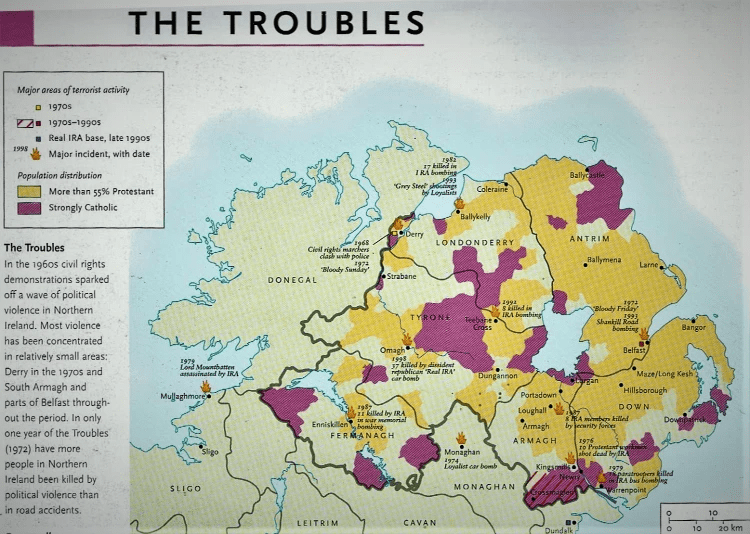

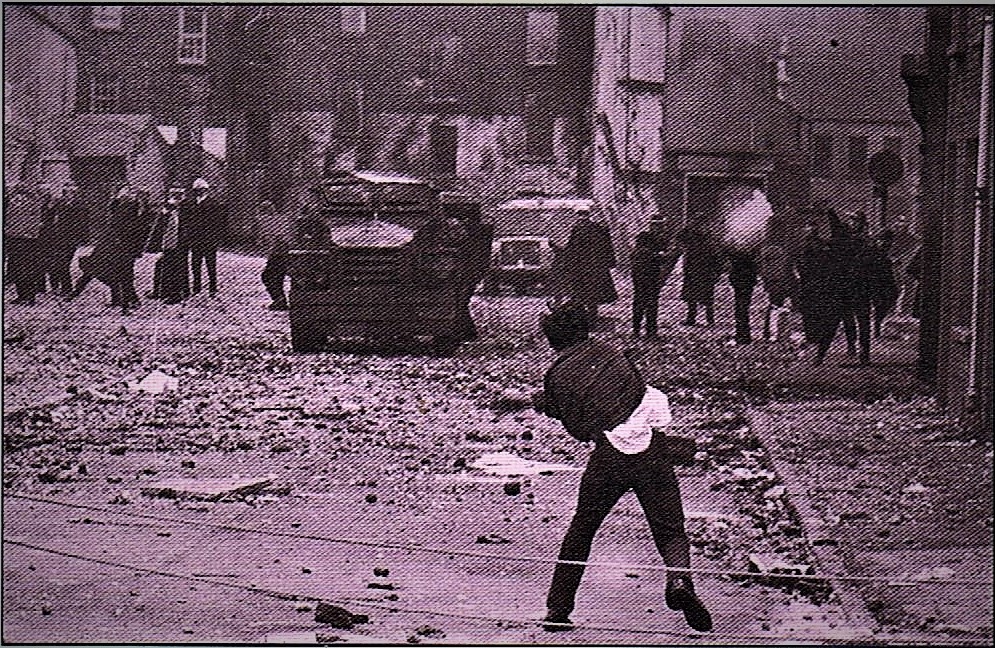

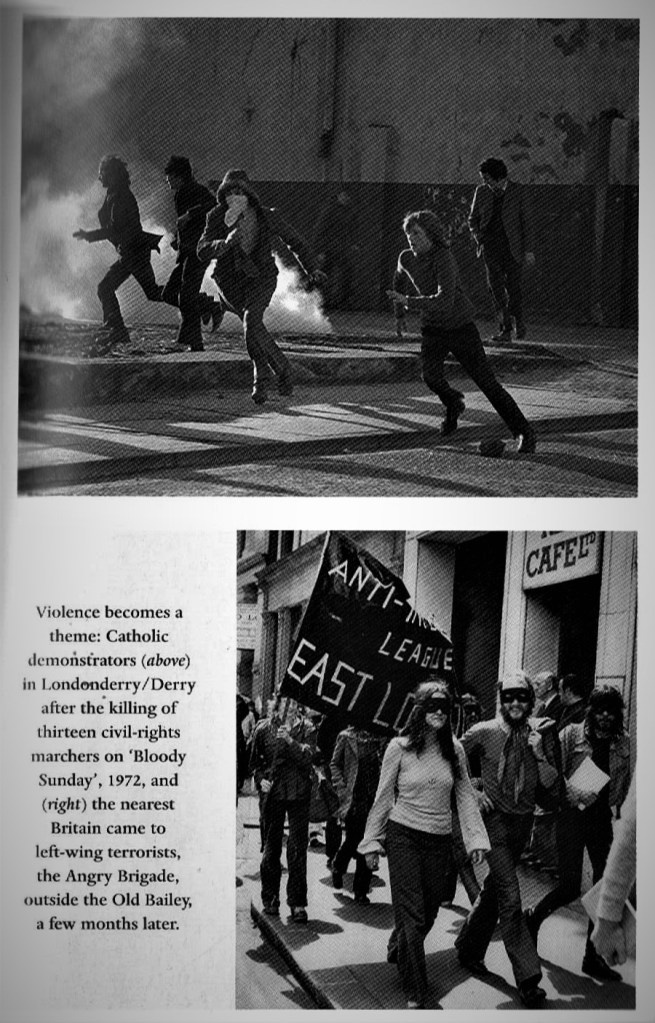

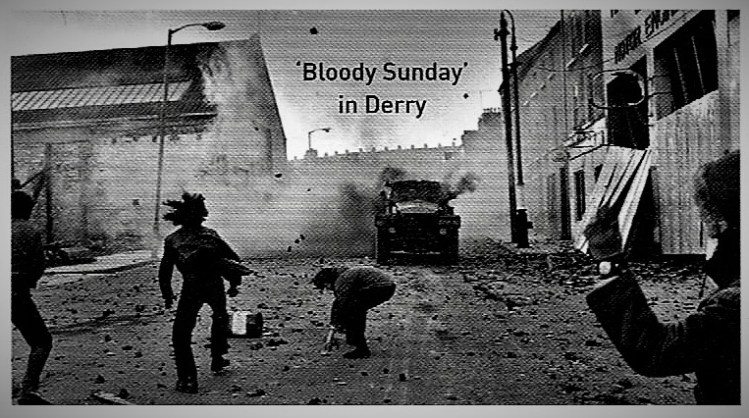

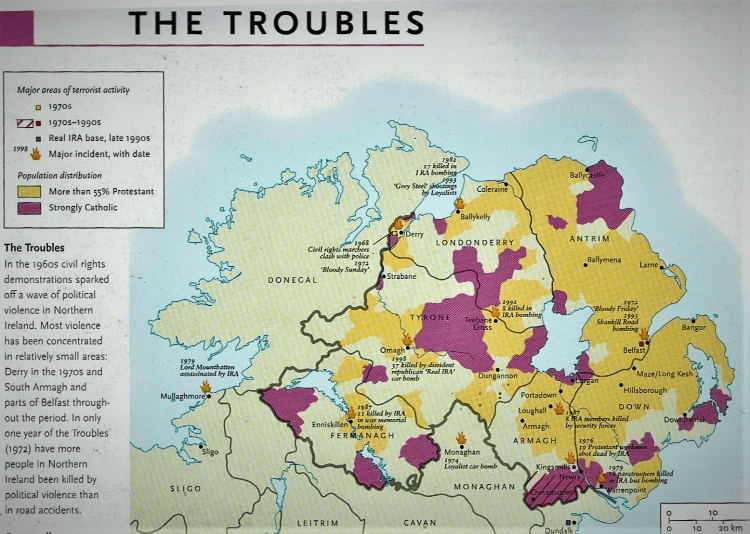

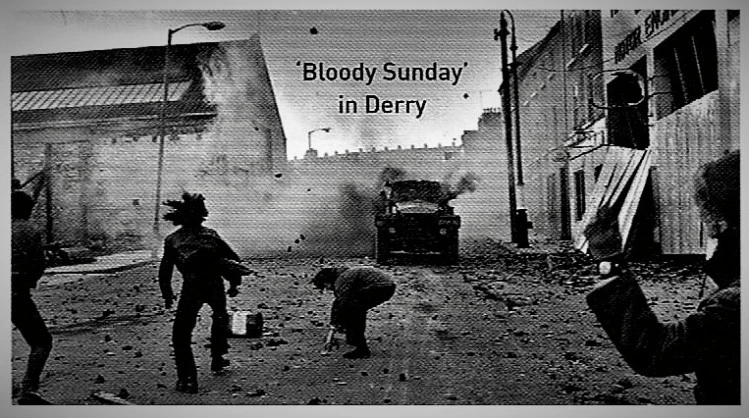

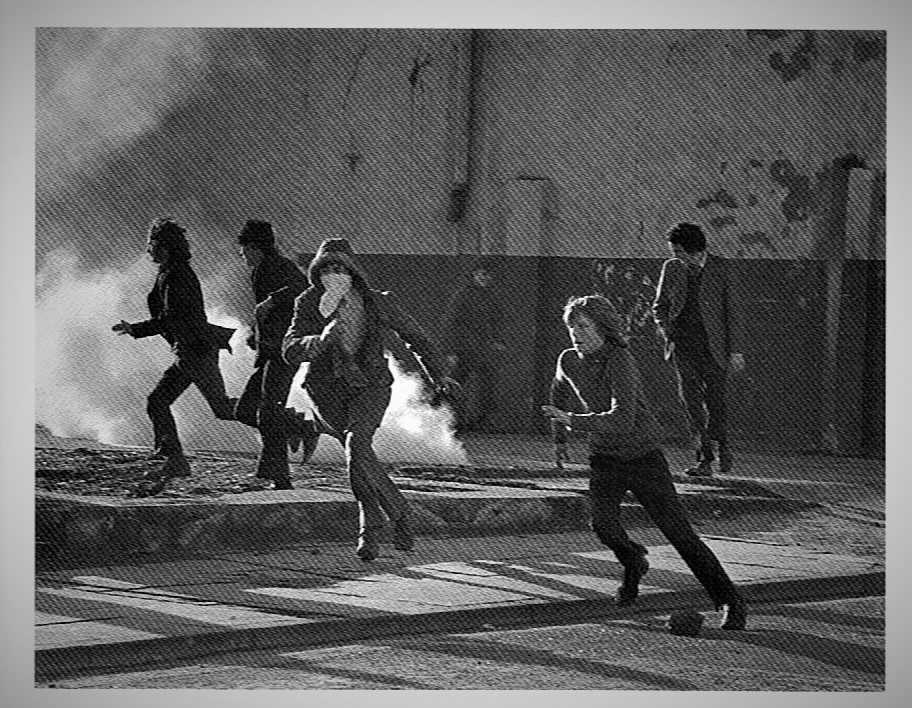

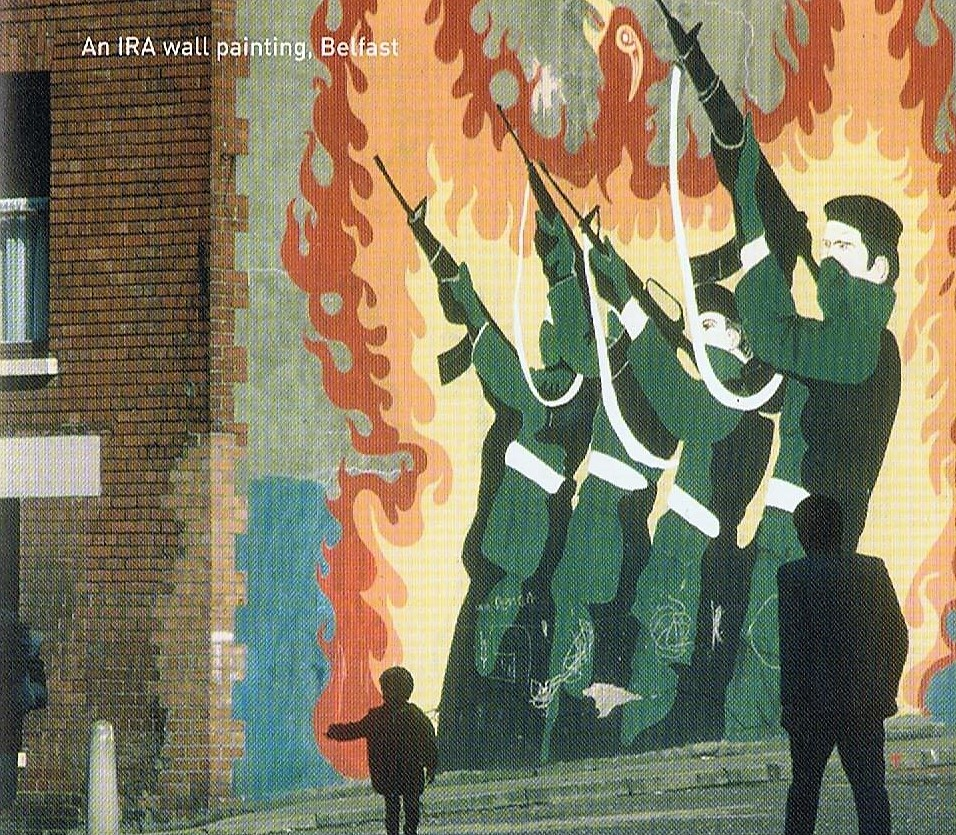

‘Bloody Sunday’ is commemorated in U2’s well-known 1983 song, the lyrics of which, while condemning the Army, are not at all supportive of ‘the battle call’ of the IRA:

‘Bloody Sunday’ is commemorated in U2’s well-known 1983 song, the lyrics of which, while condemning the Army, are not at all supportive of ‘the battle call’ of the IRA:

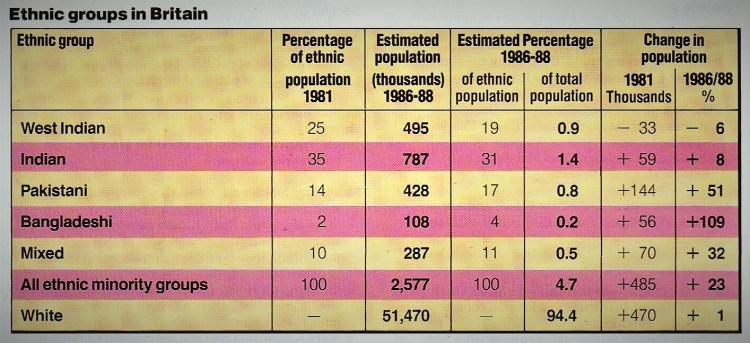

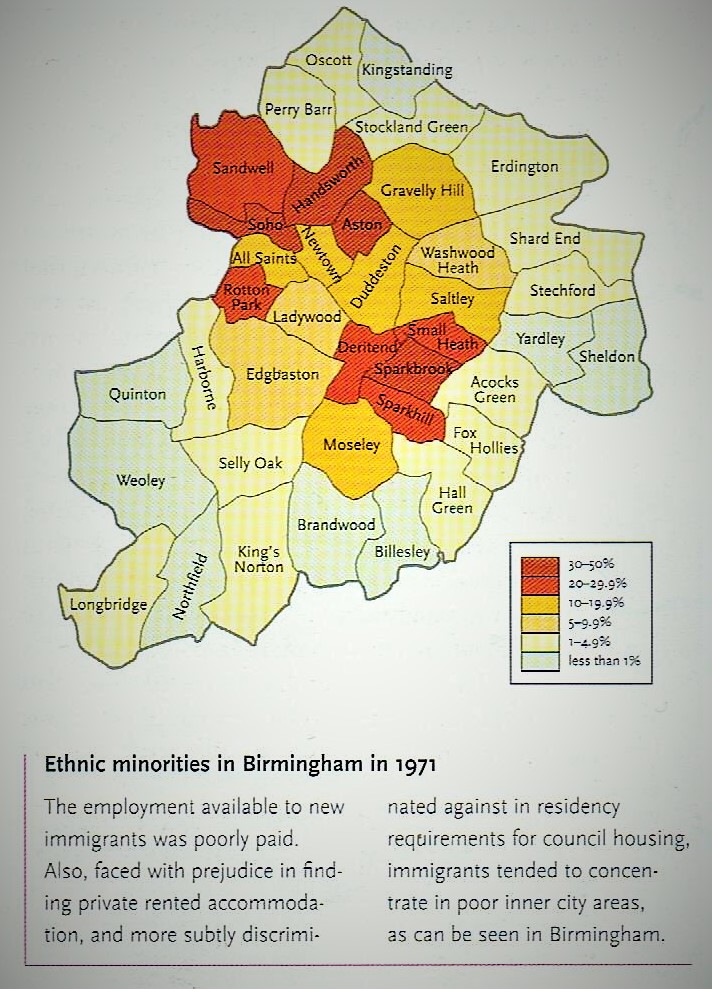

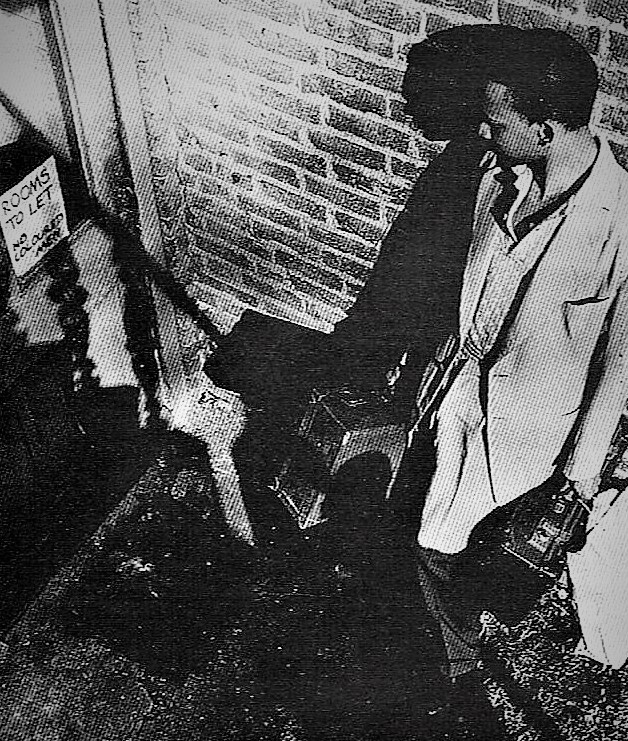

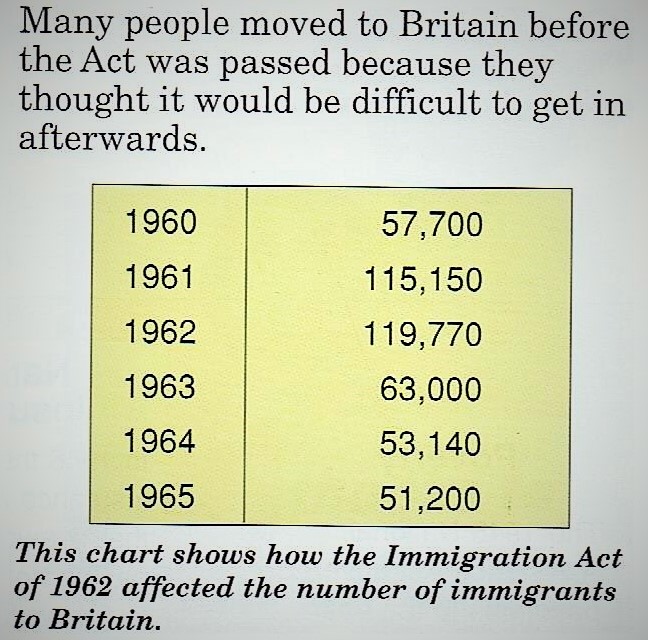

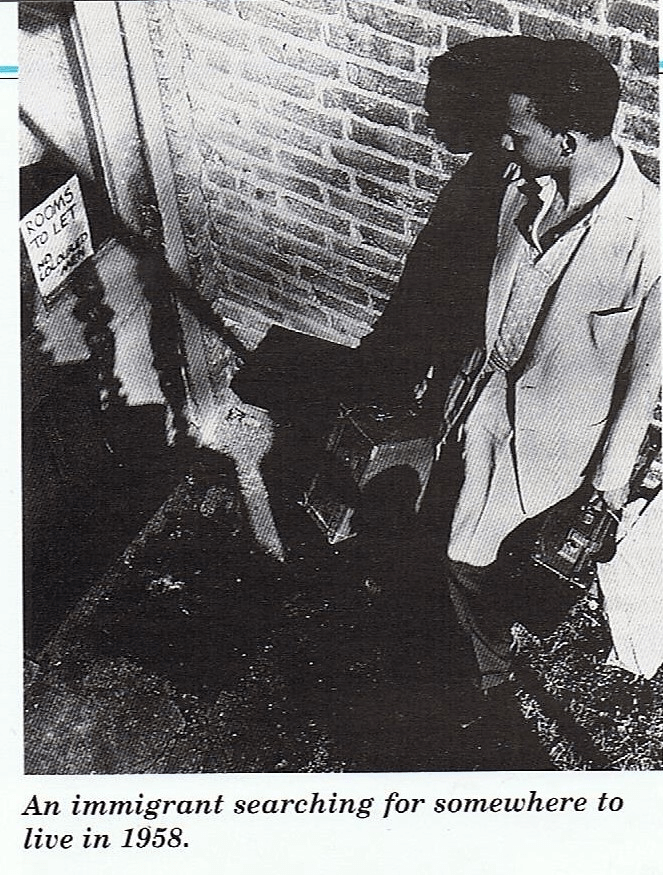

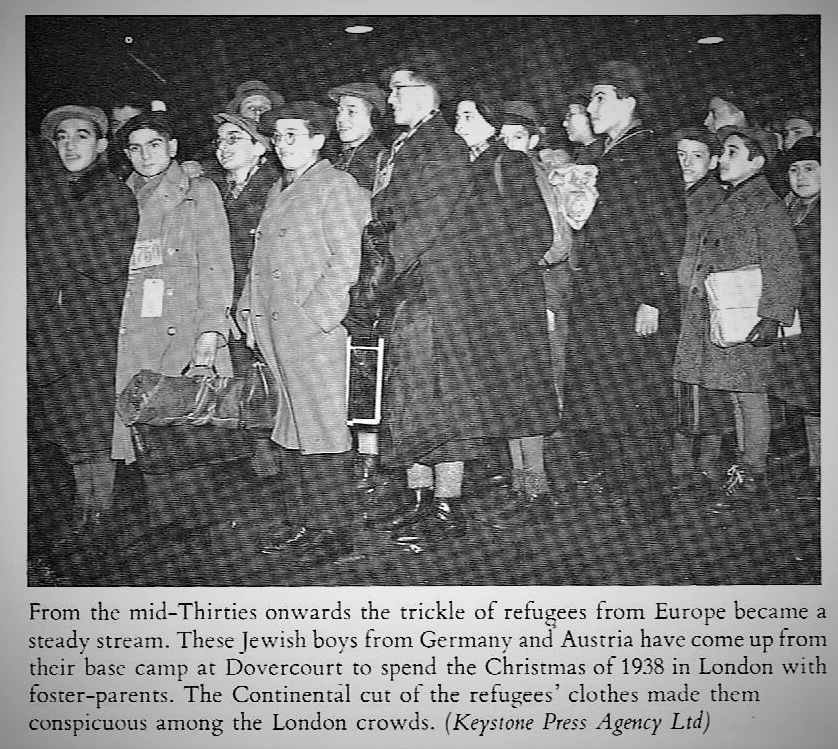

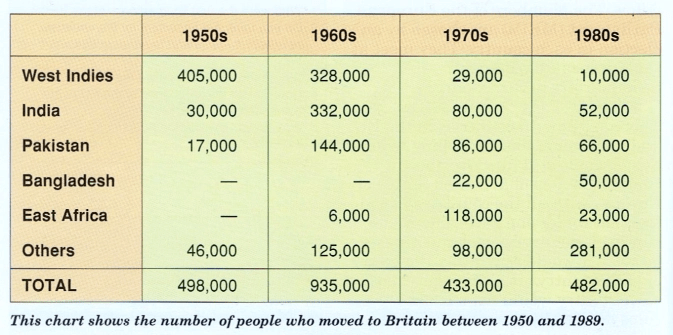

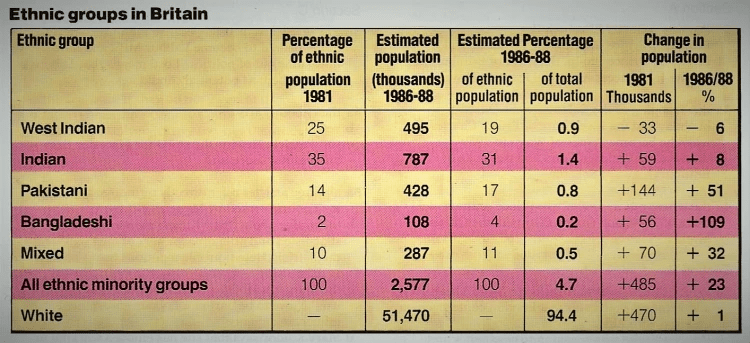

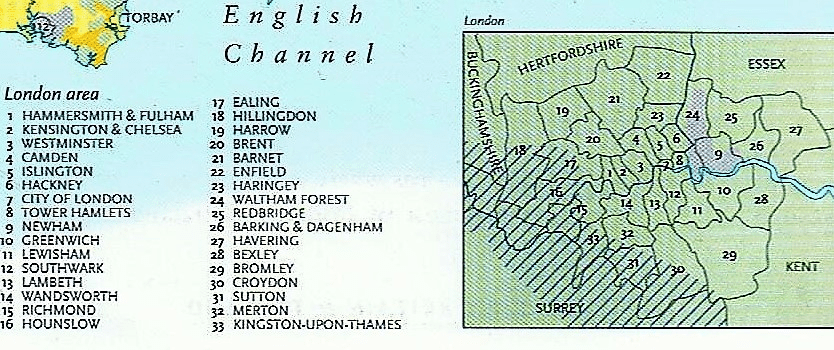

In addition, there was the sheer scale of the migration and the inability of the Home Office’s immigration and nationality department to regulate what was happening, to prevent illegal migrants from entering Britain, to spot those abusing the asylum system in order to settle in Britain and the failure to apprehend and deport people. Large articulated lorries filled with migrants, who had paid over their life savings to be taken to Britain, rumbled through the Channel Tunnel and the ferry ports. A Red Cross camp at Sangatte, near the French entrance to the ‘Chunnel’, was blamed by Britain for exacerbating the problem. By the end of 2002, an estimated 67,000 had passed through the camp to Britain. The then Home Secretary, David Blunkett finally agreed on a deal with the French to close the camp down, but by then many African, Asian and Balkan migrants, believed the British immigration and benefits systems to be easier than those of other EU countries, had simply moved across the continent and waited patiently for their chance to jump aboard a lorry to Britain.

In addition, there was the sheer scale of the migration and the inability of the Home Office’s immigration and nationality department to regulate what was happening, to prevent illegal migrants from entering Britain, to spot those abusing the asylum system in order to settle in Britain and the failure to apprehend and deport people. Large articulated lorries filled with migrants, who had paid over their life savings to be taken to Britain, rumbled through the Channel Tunnel and the ferry ports. A Red Cross camp at Sangatte, near the French entrance to the ‘Chunnel’, was blamed by Britain for exacerbating the problem. By the end of 2002, an estimated 67,000 had passed through the camp to Britain. The then Home Secretary, David Blunkett finally agreed on a deal with the French to close the camp down, but by then many African, Asian and Balkan migrants, believed the British immigration and benefits systems to be easier than those of other EU countries, had simply moved across the continent and waited patiently for their chance to jump aboard a lorry to Britain.

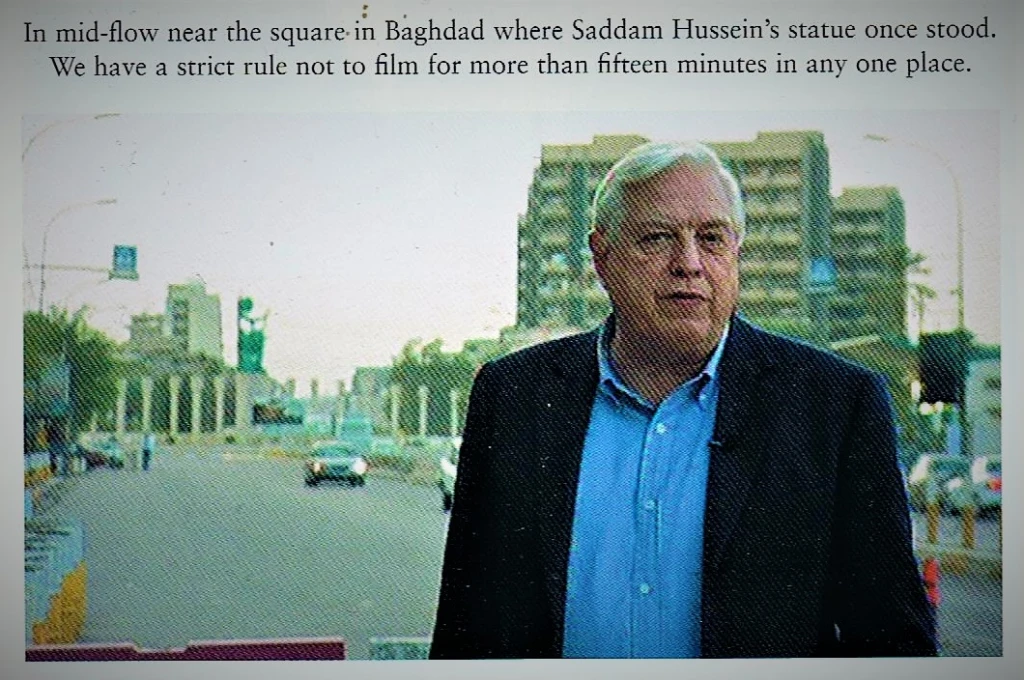

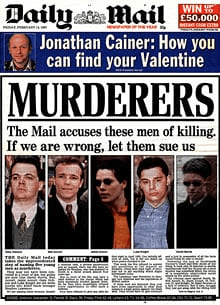

Tony Blair’s legacy continued to be paraded on the streets of Britain, here blaming him and George Bush for the rise of ‘The Islamic State’ in Iraq.

Tony Blair’s legacy continued to be paraded on the streets of Britain, here blaming him and George Bush for the rise of ‘The Islamic State’ in Iraq.