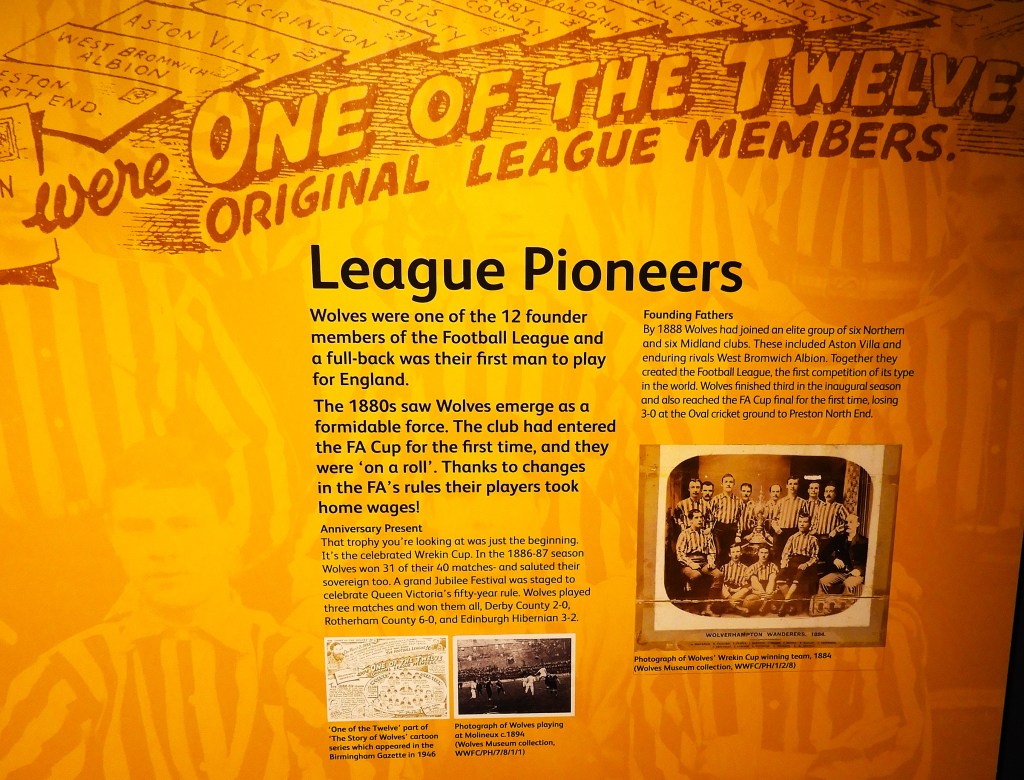

Episode Four: Scotland & England, 1093-1153

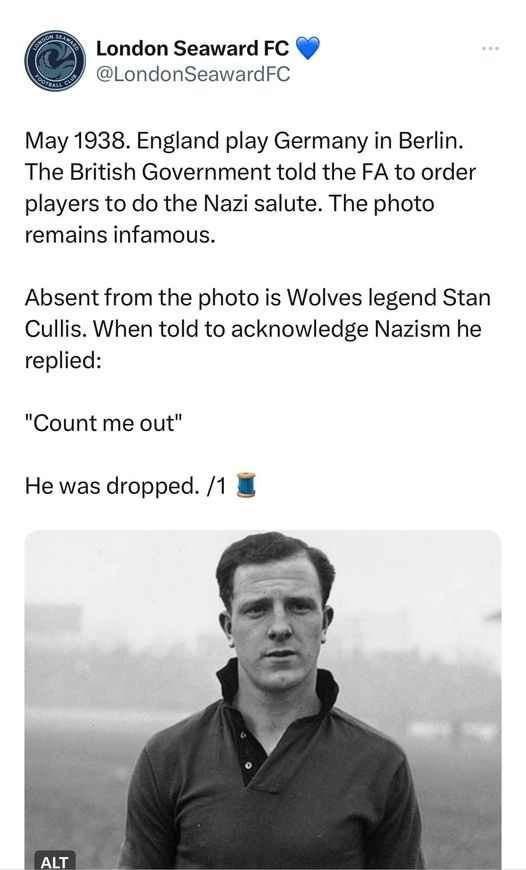

Scene Thirty-Nine – Dunfermline and Edinburgh, 1093; The Deaths of Malcolm and Margaret:

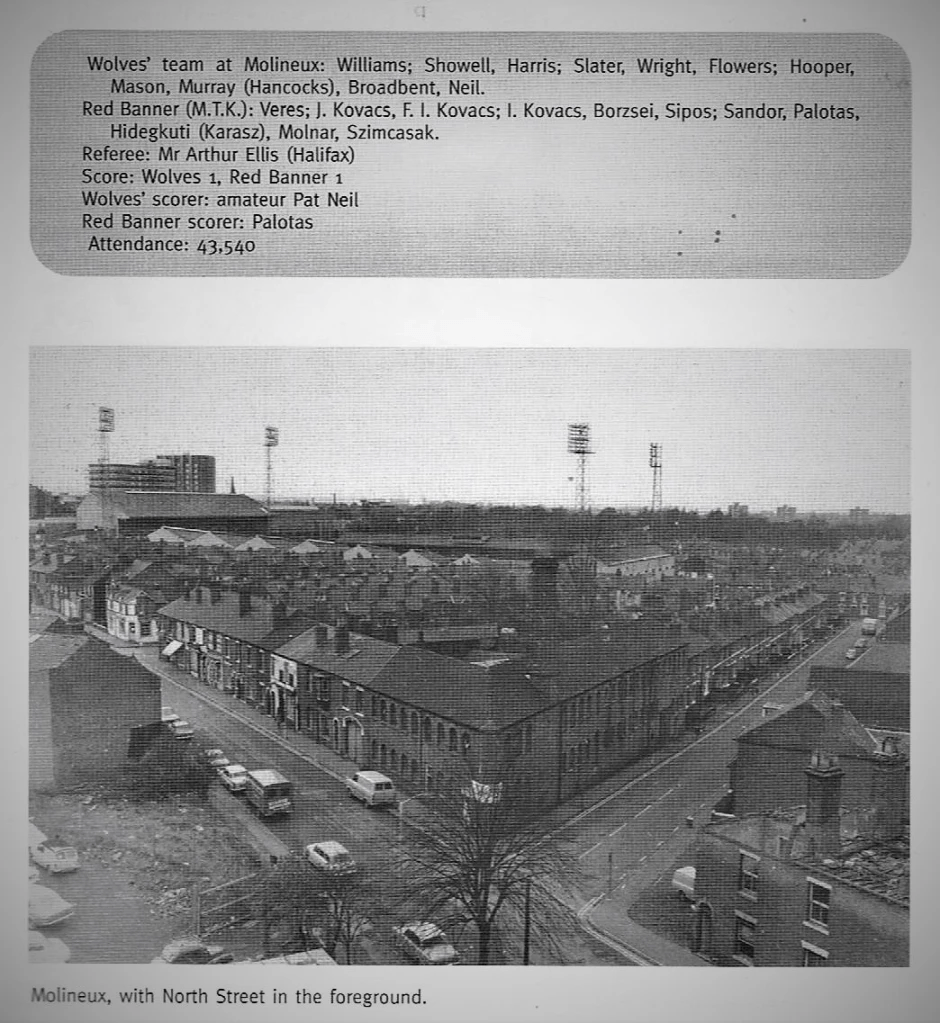

In 1092, the peace agreement between Rufus and Malcolm signed five years earlier, broke down due to the building of another new castle by the Normans at Carlisle, even though the Scots claimed and controlled most of Cumbria. But the immediate cause of the outbreak of hostilities concerned Malcolm’s personal estates in England, granted to him by William in 1072 to enable him to visit his English relatives, including his sister-in-law Cristina and his daughter Eadyth. Both were interned at Wilton Abbey. After King William died in 1087, Eadgar continued to support his eldest son, Robert Curthose, who succeeded him as Duke of Normandy, against his second son, William Rufus, who received the English throne as William II. Eadgar was one of Robert’s three principal advisors at this time. The war waged by Robert and his allies to overthrow William ended in defeat in 1091. As part of the settlement, Eadgar was deprived of the lands in Normandy confiscated from William’s supporters and granted to him by Robert. They were restored to their previous owners by the terms of the peace treaty. The disgruntled Eadgar travelled once more to Scotland, where Malcolm was preparing for war with William Rufus.

When William Rufus had marched north to be confronted by Malcolm’s army, the two kings opted to talk rather than fight. The negotiations were conducted by Eadgar on Malcom’s behalf and by the newly-reconciled Robert Curthose on behalf of his brother. The resulting agreement resulted in a reconciliation between William and Eadgar. Still, within months Robert left England, unhappy with William’s failure to fulfil the the truce, and Eadgar went to Normandy with him.

A party among the Scots hated the rule of Malcolm, seeing him as a favourer of Sassenaghs and foreigners. They may have included, in their view, his Kyíván and Hungarian nobles. Soon after his death was announced, a party was already in arms preparing to besiege the Castle of Edinburgh. Having returned to England, Eadgar went to Scotland again in 1093, on his diplomatic mission for Willam Rufus.

William Rufus wanted the lands to be returned to the Crown, but the two men agreed to a meeting to discuss this. Malcolm travelled south to Gloucester, stopping at the Abbey to visit Cristina and Eadyth, but Rufus refused to negotiate, insisting that the dispute should instead be judged by the English barons. Malcolm was insulted by this and immediately returned to Dunfermline, where (according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle), …

… he gathered his army and came harrowing into England with more hostility than behoved him.

Queen Margaret had tried to moderate her husband’s fury. She is known to have interceded with him for the release of English prisoners from the border wars of the previous decades. Although a reforming Catholic from her time growing to womanhood at Andrew’s court in Hungary, she was also respectful of the Scottish Church’s Celtic roots, instigating the restoration of Columba’s Abbey on Iona. Besides the great Romanesque and Gothic abbeys of the eleventh century, there were also smaller monuments of the Reform movement in Scotland, like the tiny chapel she built, now standing on a rampart of Edinburgh Castle.

But she had been ill for six months when Malcolm returned from his visit to Wilton Abbey and Gloucester, where he had an angry, confrontational meeting with William Rufus concerning his lands. Perhaps Queen Margaret, who was already too weak to ride out or rise from her bed, recognised the almost uncontrollable rage of her husband before he left with his army, and she had a premonition four days before she died. A priest who was with her during these last days reported that she told him,

“Perhaps on this very day, such a heavy calamity may befall this realm of Scotland as has not been for many ages past.”

The priest paid little attention to these words at the time, but a few days later a messenger arrived with the news that Malcolm had been slain on the very day that the Queen had spoken the ominous words. Before Malcolm left, she had been most urgent with him not to go with the army, but on that occasion, he had not followed her advice. Malcolm was accompanied by Edward, his eldest son by her and the heir-designate or Tánaiste, and by Edgar, her younger son.

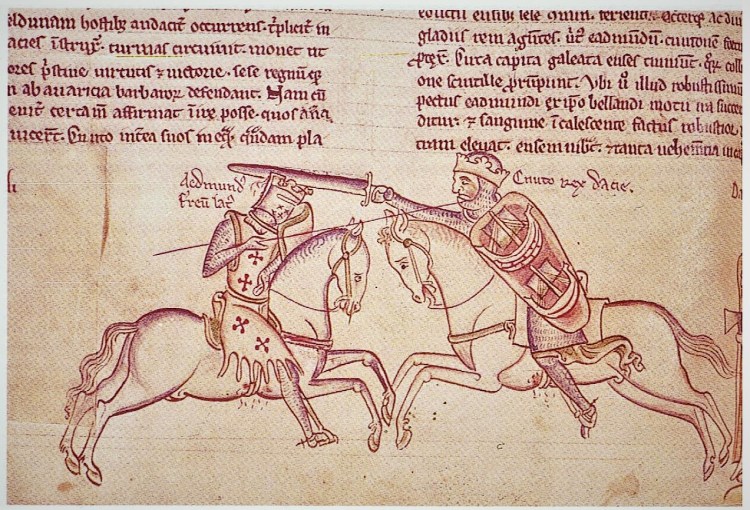

Even by the standards of the time, the ravaging of Northumbria by the Scots was regarded as harsh. While besieging Alnwick Castle on 13th November, they were ambushed by Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria, whose lands Malcolm had devastated. In what became known as the Battle of the River Aln, Malcolm was killed by Arkil Morel, steward of Bamburgh Castle, and Edward was mortally wounded. Margaret was said to have died nine days later, having received the news of their deaths from Edgar. On the eve of the fourth day following his as yet unheralded death,

… her weakness having somewhat abated, Margaret went to her oratory to hear Mass, and… there she took care to provide herself beforehand for her departure, which was now so near, with the holy Viaticum of the Body and Blood of our Lord. After partaking of this health-giving food, she returned to her bed, her former pains having assailed her with redoubled severity. The disease gained ground, and death was imminent. … Her face was already covered with a deadly pallor when she directed that I, and the other ministers of the sacred Altar along with me, should stand near her and commend her soul to Christ by our psalms.

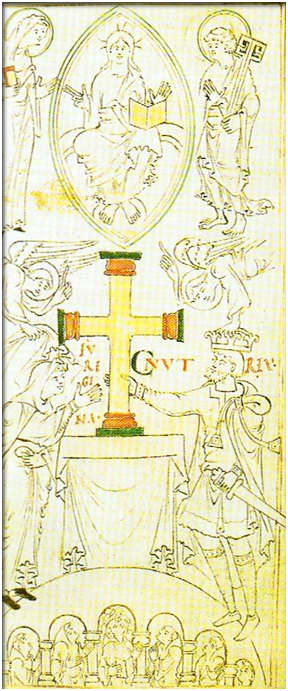

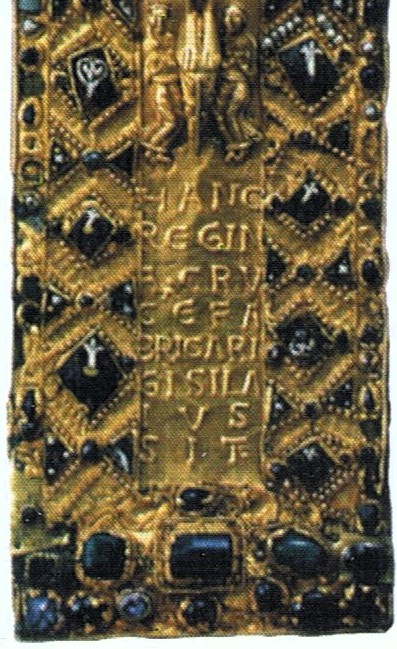

Moreover, she asked that a cross, called the Black Cross, which she always held in the greatest veneration, should be brought to her. There was some delay in opening the chest in which it was kept, during which the Queen, sighing deeply, exclaimed, ’O unhappy that we are! O guilty that we are! Shall we not be permitted once more to look upon the Holy Cross?!’ When at last it was got out of the chest and brought to her, she received it with reverance, and did her best to embrace it and kiss it, and several times she signed herself with it. Although every part of her body was now growing cold, still as long as the warmth of life throbbed at her heart she continued steadfast in prayer. She repeated the whole of the Fiftieth Psalm, and placing the cross before her eyes, she held it there with both her hands.

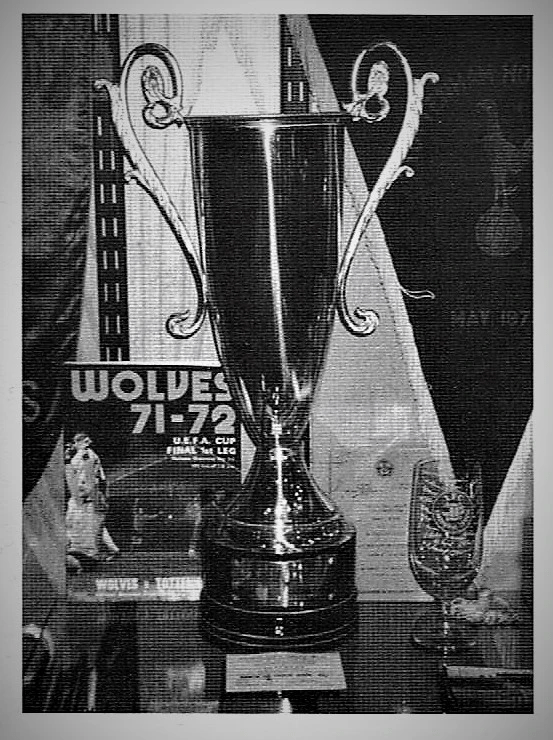

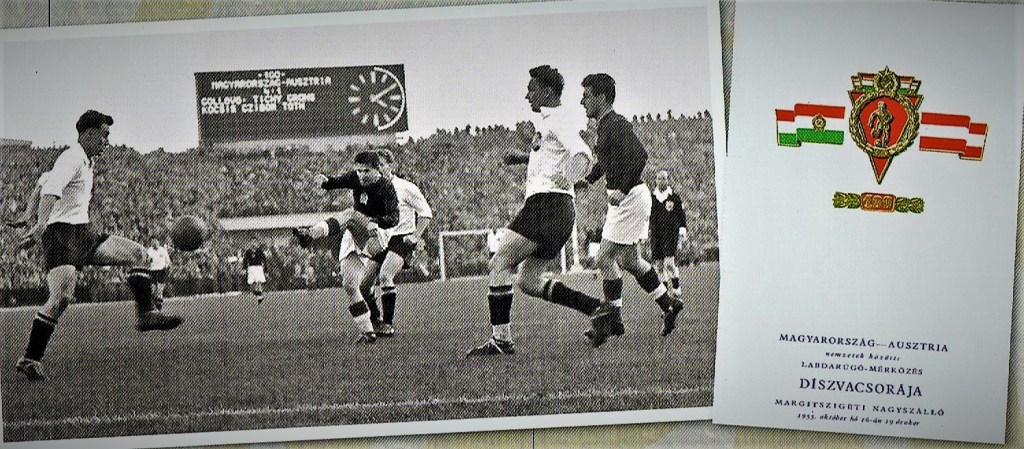

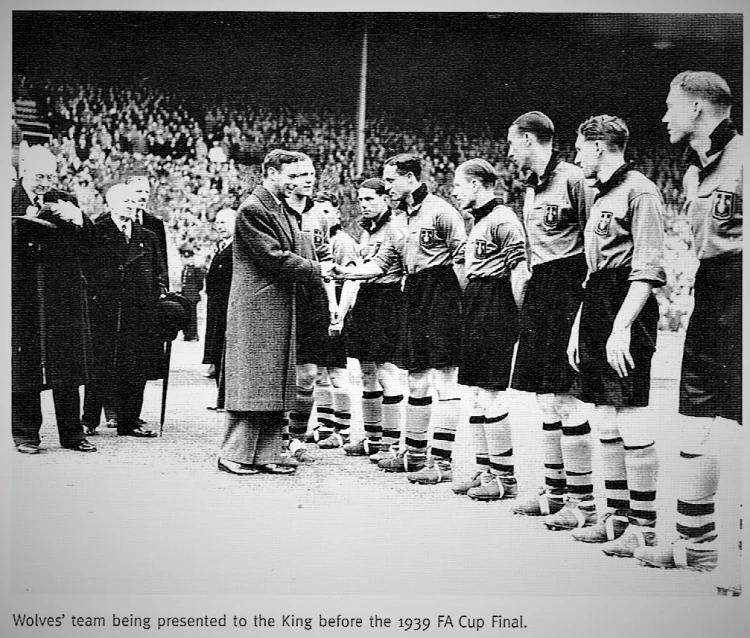

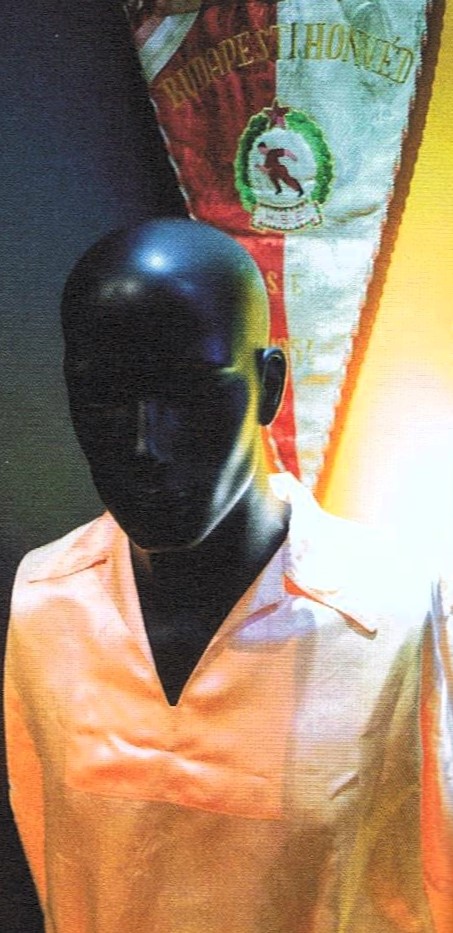

The Black Cross was first given by Gizela to Agatha in c.1045 when Gizela left Hungary to return to Bavaria (Niedenburg), where she lived out her life as a nun and died in c.1060. From Agatha, it passed to Margaret, presumably when Agatha returned to Bavaria in or after 1070. The cross isn’t described in detail, but it was gold set, encrusted with dark stones. It was at this point that her son, Edgar, returning from the army, entered the queen’s bedroom:

Conceive his distress at such a moment! Imagine to yourself how his heart was racked! He stood there in strait; everything was against him, and whither to turn himself he knew not. He had come to announce to his mother that his father and brother were both slain, and he found that mother, most dearly beloved by him, at the point of death. He knew not whom first to lament. Yet the loss of his dearest mother, when he saw her nearly dead before his eyes, stung him to his heart with the keenest pang. Besides all this, the condition of the realm occasioned him the deepest anxiety, for he was fully aware that the death of his father would be followed by an insurrection. Sadness and trouble beset him on every side. …

The queen, who seemed to the bystanders to be rapt in agony, suddenly rallied and spoke to her son. She asked him about his father and his brother. He was unwilling to tell the truth, and fearing that if she heard it she would immediately die, he replied that they were well. But with a deep sigh, she exclaimed,

“I know it, my son, I know it. By this holy cross, by the bond of our blood, I adjure you to tell me the truth.”

Thus pressed, he told her exactly all that had happened. … At that same moment, she had lost her husband and son, and disease was bringing her to a cruel death.

… Raising her eyes and hands towards heaven, she glorified God, saying…

“All praise to thee… who hast been pleased that I should endure such deep sorrow at my departing… and I trust that by means of this suffering… I should be cleansed from some of the stains of my sins. … Lord Jesus Christ, … deliver me.”

Her body was carried to the Church of the Holy Trinity at Edinburgh Castle, which she had built, and buried opposite the altar, and thus her body at length rests in that place in which, when alive, she used to humble herself with vigils, prayers and tears. Her place of death is not mentioned in Turgot’s Life of Margaret, but Fordun states that Margaret died in Edinburgh in Castro puellarum on 16 November1093, according to the Chronicle of Mailros. Wynton also related this in his verse form Orygynale Cronikil.

Malcolm’s body was taken to Tynemouth Priory for immediate burial but then was sent north-west for re-burial in the reign of his son, Alexander, at either Dunfermline Abbey or Iona (during the Scottish Reformation the bones of both Malcolm and Margaret were reinterred in Catholic Spain).

Forty; The Later Adventures of the Aetheling, Scotland and the Crusades, 1093-1126:

On his return from Flanders, Eadgar the Aetheling had been forced to pay homage to William, and a chronicler tells us that he dragged on a sluggish and contended life as the friend and pensioner of Norman patrons. Disappointed with the level of recompense and respect shown to him by William, however, in 1086 he renounced his allegiance to the Conqueror and moved with his retinue to Norman Apulia in Italy. The Domesday Book, compiled that year, records Eadgar’s possession of only two small estates in Hertfordshire. Clearly, he left for Italy not intending to return, but the venture in the Mediterranean was unsuccessful and within a year or so he had returned to England. But in 1093, following the death of his sister Margaret, Eadgar decided to go on his travels again, this time returning to his birthplace, Hungary, and from thence to the Eastern Mediterranean and Byzantium.

When the First Crusade was proclaimed in England in 1095, William Golafre (de Goulafriére), Suffolk sub-tenant, was one of the first Anglo-Norman knights to join the contingent of Robert of Normandy; in general, cross-channel family connections must have been how most crusaders from Britain were recruited.

The Norman army which had invaded England in 1066 was by no means exclusively Norman, nor were the new tenants-in-chief or barons of the thirty years following. They included men from many parts of France, who traced their ancestry to Flanders, Aquitaine, Anjou and Brittany, in addition to Normandy. The Golafre family were one noble family who really did come over with the Conqueror from St Evreux in Normandy where they were Lords of Mesnil Bernard. There is still a small town, or large village, called La Goulafriere.

Guillaume Goullafre can still be found in the archives of Bayeux Cathedral for the eleventh century (Chronology of the Ancient Nobility of the Duchy of Normandy, 1087-1096) where he appears on a list of lords who accompanied Robert Duke of Normandy on the first crusade in 1096. He is also listed as one of the Knights Templar. Leland also refers to a Guillaume Goulaffre (Dives Roll) and a Roger Gulafre, who claimed property from St. Evroult, where a great abbey still stands. He is referred to specifically as Lord of Mesnil Bernard. William Gulafre, as he later seems to have been known in England, held great estates in Suffolk at the time of Domesday (1086) and gave tithes to Eye Abbey.

William’s son, Roger Gulafre, was also of Suffolk, according to the Pipe Rolls of 1130, and Philip Gulafre held four fees in barony in the same county later in the twelfth century, as well as manors in Essex. They also seem to have inter-married with both French and Breton noble families who arrived in Suffolk during the Conquest. There was also increasing intermarriage between Normans and Saxons, but more often for land rather than love on the part of Norman nobles.

Malcolm’s successor, his brother Donald Bán, drove out the English and French soldiers who had risen high in Malcolm’s service and had aroused the jealousy of the existing Scottish aristocracy. This purge brought him into conflict with the Anglo-Norman monarchy, whose influence in Scotland had diminished following the Conqueror’s death. William helped Malcolm’s eldest son, Duncan, who had spent many years as a hostage at William I’s court and remained there when set free by William II, to overthrow his uncle, but Donald soon regained the throne and Duncan was killed.

In the forty years from 1093 to 1133, Jerusalem was taken for Christianity and north-western Europe’s population and settlements developed to a point not seen since the Celtic migrations of the fourth century BC.

The military and religious movement known as the Crusades began in 1095, with the call of Pope Urban II for a campaign to free the holy places of the Middle East from Muslim domination. Britain’s involvement with crusading was at first modest. A twelfth-century English chronicler wrote that of the events in Asia (’Minor’), only a faint murmur crossed the channel. When Pope Urban summoned the chivalry of Christendom to the Crusade, he also released in the masses across Europe hopes and hatreds which were to express themselves in ways quite alien to the aims of the papal policy.

The main object of Urban’s famous appeal was to provide Byzantium with the reinforcements it needed to drive the Seljuk Turks from Asia Minor; for he hoped that in return the Eastern (Orthodox) Church would acknowledge the supremacy of Rome so that the unity of Christendom would be restored.

In addition, he was concerned to indicate to the nobility an alternative outlet for martial energies which were still constantly bringing devastation to continental lands. The Church had, for half a century, been concerned with limiting feudal warfare by what it referred to as the Truce of God. Accordingly, in addition to the clerics, a large number of lesser nobles had come to Clermont to hear the Pope address the Council.

To those who would take part in the Crusade, Urban offered impressive rewards. A knight who took the Cross would earn a remission from temporal penalties for all his sins; if he died in battle, he would earn remission of sins. And there were to be material as well as spiritual rewards.

The great nobles of Western Europe set off in 1096 by different routes to Constantinople, crossing the Bosphorus and overrunning Asia Minor. However, Eadgar’s invasion of Scotland late in 1097 would have made it impossible for him to have been commander of the English fleet which arrived off the Syrian coast in March 1098, as claimed by Orderic. Another effort to restore the Anglo-Norman influence in Scotland through sponsorship of Malcolm’s sons was launched in 1097, and Eadgar made yet another journey north, this time in command of an invading army. Donald was ousted, and Eadgar installed his nephew and namesake, Malcolm and Margaret’s son Edgar, on the Scottish throne.

Moreover, Eadgar’s niece Eadyth, daughter of Malcolm and Margaret, married Henry I on 11th November 1100, becoming Queen Matilda, three months into Henry’s reign. While we have no record of the wedding guests, it is unlikely that Eadgar would have gone abroad before so auspicious a royal wedding. Finally, the English had an English Queen, a daughter of Wessex, of the true royal family of England, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pointedly put it.

After the ceremony, Eadgar travelled overland to join the fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean. No doubt, he took the route along the Danube through the land of his birth, Hungary, opened up to pilgrims by King István. He would then have sailed from Byzantium through the Dardanelles to the Levant and Syria, though there is no record of his journey.

In dealing with the variety of crusader armies reaching the western borders of Hungary, King Koloman had forged good relations with the French-led forces, defeated those of the prophetae and did not permit both those of William the Carpenter, Viscount of Melun and those of Count Emich of Leiningen to cross the country. In addition, the marriage of King Ladislas’s fabulously beautiful daughter, Piroska, had earned Hungary the goodwill of Constantinople.

The reigns of both Ladislas and Koloman brought about a fundamental change in Hungary’s international standing. Whereas throughout the eleventh century, the nascent kingdom had to defend itself against German expansionism, in the next three centuries it was emboldened by the conquest of Dalmatia and Croatia, and it was able to pursue expansionist policies of its own. Koloman’s economic policies continued the work of Ladislas, imposing higher taxes on commerce, which was refreshed by the influx of Jews who had been expelled from Bohemia by the Crusaders. However, there is little evidence of a renewal of direct relations between the English and Hungarian monarchies until the end of the fifteenth century.

The crusaders entered Jerusalem in 1099 and the group led by Eadgar distinguished itself in the service of the Byzantine emperor on the Crusade of 1101-2. William of Malmesbury recorded that Eadgar made his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1102 so that Orderic’s report is probably the result of his conflation of the English fleet’s expedition with Eadgar’s later journey.

On his way back from Jerusalem, Eadgar was given rich gifts by both the Byzantine and German emperors, each of whom offered him an honoured place at court, but he insisted on returning home, whether that was to be England or Scotland. Some historians, however, have suggested that at some point in these years he served in the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine Empire, in a unit that was composed primarily of English exiles under the leadership of Siward Barn, released from captivity by William at the end of his reign, whom Eadgar had known from his time in exile at the court of King Malcolm. Siward was reported as being in the company of Eadgar at Wearmouth after the failure of the northern rising and the Harrying of the North, and to have accompanied him to Scotland. He was then arrested by William’s troops at the siege of Ely in 1072 and imprisoned until 1087. From there, he went to Byzantium where he became the Sigurd Jarl commanding the other Anglo-Danish exiles in the Emperor’s service.

Forty-one – 1100; Godfric and Godiva – the Anglophile Norman Monarch and his Wessex Wife:

A temporary truce between the royal brothers, William and Robert, had prevailed from 1096 when Robert left to fight in the First Crusade, but four years later Rufus was killed while hunting in the New Forest, leaving either Robert or the youngest son, Henry to be crowned as England’s new king. Robert hurriedly returned from the East, and the struggle for supremacy resumed.

Back in Europe, Eadgar again took the side of Robert Curthose in the internal struggles of the Norman dynasty, firstly against William Rufus and then against Henry Beauclerc. But when he was taken prisoner at the Battle of Tinchebrai in 1106 and sent back to England, he was pardoned and released by King Henry, who was by then his nephew through his marriage to Matilda (Eadyth). The dynastic struggle ended when Henry captured Robert, who spent the rest of his life in prison, dying in 1134, a year before Henry’s own death.

Henry’s victory at Tinchebrai over Duke Robert was the culminating point in the struggle for Normandy and after nineteen years, the King of England was once more Duke of Normandy; like Hastings, the battle was a touchstone of prestige among the Normans, a battle with which the aristocracy wished to be associated if they possibly could be.

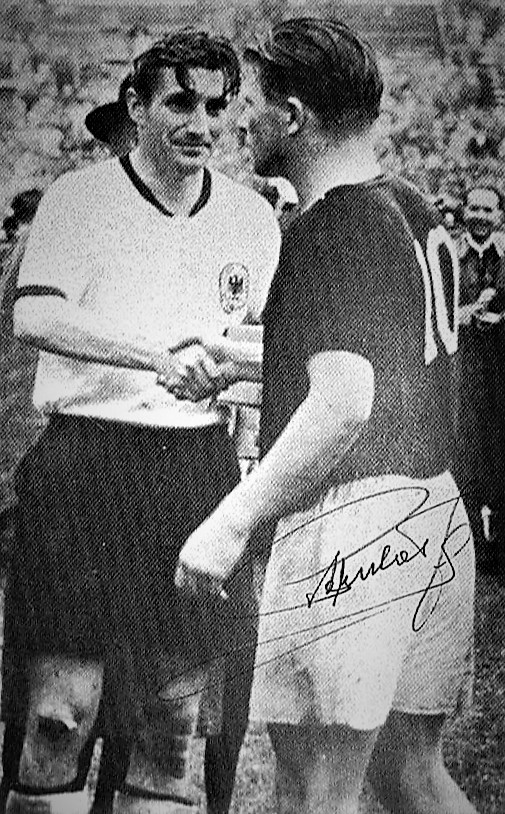

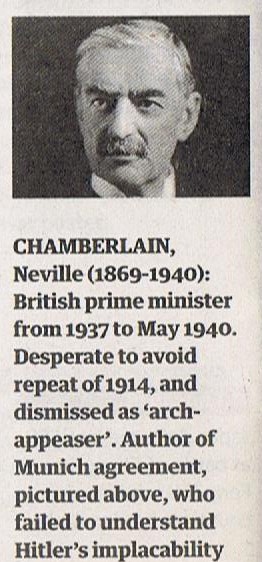

Born in England, married in England to an Anglo-Scottish princess and buried in England, William’s youngest son, Henry, appears to have been the first royal Norman anglophile. His marriage was a major factor in this and came about because Margaret of Scotland’s sister Cristina (pictured above) became a nun in southern England and became acquainted with Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury (1033/4-1109). Margaret’s daughter, Eadyth, was placed in the care of Cristina, who took her first to Romsey Abbey and later to Wilton Abbey in Wiltshire, not far from Winchester. However, although Cristina made her niece wear a nun’s veil to protect her from the lust of the Normans, she never took holy orders and fought to maintain her status as a marriageable woman. Her father, Malcolm, is said to have torn her headdress from her when he first visited her at Wilton. The Abbey was a place of education for other royal children during the early medieval period.

While there, she met Henry at William Rufus’s Court following the death of her parents in 1093, and on the couple’s marriage, William of Malmesbury wrote that Henry had long been attached to her. Orderic Vitalis also wrote that Henry had long adored her character and capacity. He also wrote that she was not bad-looking, despite her excessive face painting which, he claimed, didn’t improve her appearance. She testified to Anselm at Lambeth Palace that she had not become a nun, and he held a council at which he ruled that she was eligible to marry the King and become his Queen Consort. At her coronation, she took the regnal name of her Great Aunt Matilda in order to appease the Norman noblemen at court, and became known to the people as Good Queen Maud.

He and his Eadyth christened their daughter Matilda, for the benefit of their Norman baronage, but privately called her by the Anglo-Saxon title ‘Aethelic,’ while their son William was given the title ‘Aetheling’, like his great uncle, Eadgar. During the English investiture crisis of 1103-1107, Queen Matilda acted as an intercessor between Henry and Anselm. England and Scotland also grew closer during Henry and Matilda’s reign, especially after Margaret’s youngest son David’s accession to the Scottish throne.

Henry ‘Beauclerc’ (1100-1135) helped Normans and Saxons to live side by side in peace and granted a charter upholding the best of the English laws. He set up a King’s Court (Curia Regis), where disputes and crimes were dealt with by trained lawyers. As a result, the chroniclers recorded, the people learned the value of the King’s Peace. Some of his plans to systematise this means of justice were carried out by Henry II.

Towards the end of his reign, in a sign of his commitment to compromise within the English Church, Henry appointed a Saxon priest, Aethelwolf to the newly created Bishopric of Carlisle. In addition to teaching her husband English, Matilda was responsible for encouraging William of Malmesbury to write his History of the English Kings. The chronicler had written of England after the Conquest as:

… the habitation of strangers and the dominion of foreigners. There is today no Englishman who is either earl, bishop or abbot. The newcomers devour the riches and entrails of England, and there is no hope of the misery coming to an end.

Clearly, Henry set out to effect a reconciliation between the Normans and the English. According to William of Malmesbury however, none of this went down well with the Normans at Henry’s court who openly mocked the king and queen, calling them Godric and Godgifu (Godiva), but it did play well with the majority of the king’s English subjects across the country as a whole. No doubt, this was Henry’s intention.

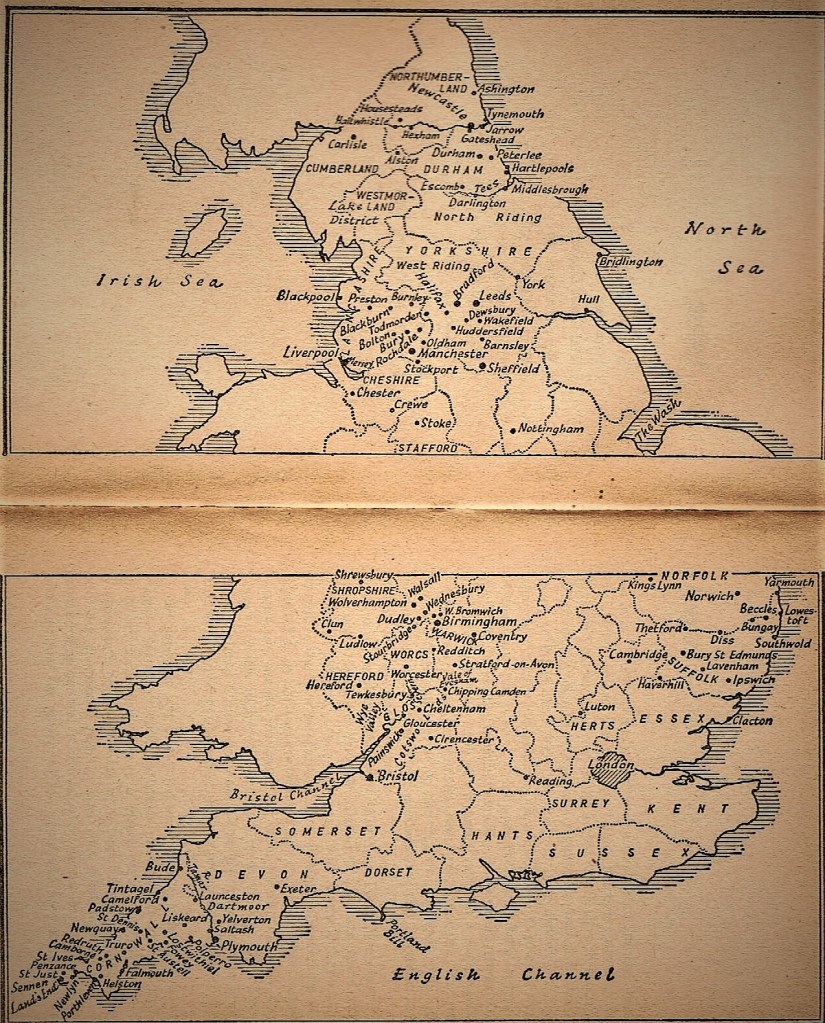

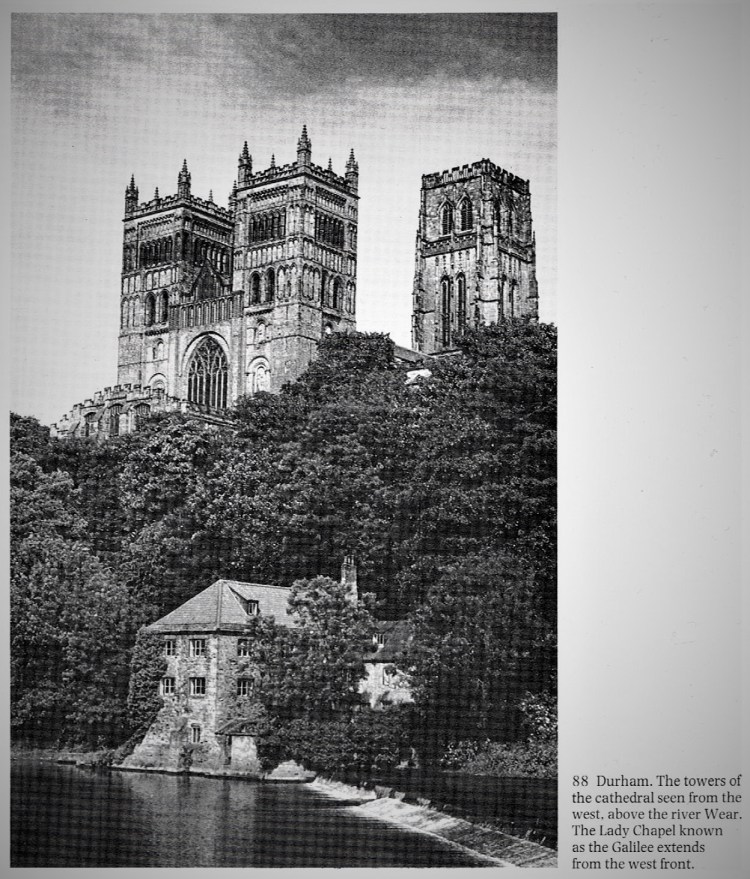

King Henry also reached out to the Scots by giving the hand of Matilda of Huntingdon, daughter of Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria, to David I of Scotland. The marriage brought with it The Honour of Huntingdon, a lordship scattered through the shires of Northampton, Huntingdon and Bedford. These new territories increased David’s status not just as the undisputed king north of the border, but as one of the most powerful magnates in the Kingdom of the English. In addition, he acquired the former lordship of Waltheof, covering the far north of England including Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumberland, as well as the overlordship of the bishopric of Durham. He was, effectively, ‘King in the North’. Despite his sister Eadyth’s death in 1118, David retained the favour of King Henry and was the first to take the oath to uphold the succession of his niece, Matilda, to the English throne.

Forty-two; 1113 – Scotland & the Borders to the reign of David:

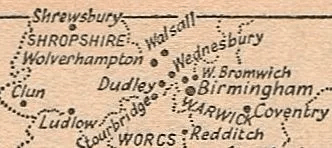

The Normans faced an even less well-developed border with their northern neighbours than with the Welsh. There were no clear geographical boundaries capable of preventing political expansion, and ethnicity by itself could not serve as the basis for states. Nor could language, so that what eventually became Scotland, and, to a lesser extent, Cumberland and Northumberland, were ethnically, linguistically, culturally diverse territories which often ovelapped each other, including Scots, Picts, Gaels, Britons, Angles and Saxons.

Until the mid-twelfth century, it was unclear whether much of what eventually became lowland Scotland and northern England, in particular Cumbria and Northumbria, would be part of the Kingdom of England or the Kingdom of Scotland. The mixture of populations in Cumbria and Lothian ensured that there was no obvious border. William II’s conquest of Cumbria in 1092 played a major role in fixing the frontier with England, but many of the northern and western isles still remained in the possession of Norway, a continuing, complicating factor for the Plantagenet kings.

The Scottish King David I had been Prince of the Cumbrians (1113-24) before becoming King of Scotland. He spent most of his childhood in Scotland but was exiled to England in 1093, after being orphaned by the deaths of Malcolm and Margaret. As their second youngest son, he became a dependant of his aunt and uncle, Henry I and Queen Matilda. The three royal brothers, David, Alexander and Edgar, had been in their mother’s room when she died.

According to The Melrose Chronicle, the three brothers were then besieged in Edinburgh Castle by their paternal uncle, Donald III, who had made himself king and forced his three nephews into exile. John of Fordun later wrote that Eadgar Aetheling arranged an escort for them into England. From Westminster, King William II opposed Donald’s succession and sent the exiled boys’ half-brother, Duncan, into Scotland with an army, but he was killed within a year. When William was accidentally killed, his younger brother Henry became king and married David’s sister, Eadyth, making David his brother-in-law and an important figure at the English court. Despite his Gaelic upbringing, by the end of his time at court, David was a fully Anglo-Norman prince. When King Edgar died, he was succeeded by Alexander, and David became Prince of the Cumbrians in 1113. In the same year, Henry returned from Normandy and David founded Selkirk Abbey. This and King Henry’s backing seems to have been enough to force Alexander to recognise his younger brother’s claims to southern Scotland.

When his brother, Alexander I died in 1124, David took over the Kingdom of Alba but had to engage in dynastic warfare against his nephew, Máel Coluim mac Alexandair, a struggle that lasted a full decade. In 1134, Máel Coluim was captured and imprisoned in Roxburgh Castle. By the time King Henry died in December 1135, David had more of Scotland under his control than any Scottish king before, but his plans for the north began to encounter problems in the 1150s when the King of Norway gained fealty over Orkney.

Eadgar Aetheling travelled to Scotland once more late in life, around the year 1120 and was still alive in 1125, according to William of Malmesbury, growing old in the country in privacy and quiet. Having finally given up his claim to the English throne, the ‘Aetheling’ died in 1126, not long after his niece, Eadyth (Queen Matilda) in 1121. Before her death, Queen Matilda honoured her mother by founding the house of Holy Trinity in Aldgate, London.

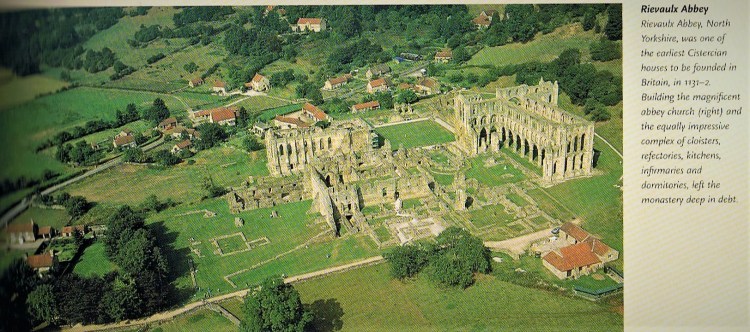

The founding order, the Premonstratensians, had also been particularly important in Scotland, founding the house at Dryburgh on the border and reviving the holy site of St Ninian’s white church at Whithorn. But the most enduring of the new orders were the Cistercians. From their first foundation at Waverley in Surrey (1128) by William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, the order quickly spread throughout Britain. They founded the abbeys of Rievaulx, Fountains and Byland in North Yorkshire, Tintern in Wales, Thame in Oxfordshire, and Coombe Abbey in Warwickshire.

The Cistercians exploited their far-flung estates through granges, model farms operated by lay brothers who supervised paid labourers. Most of these were established in the twelfth century, the great era of Cistercian expansion. By then, Yorkshire had forty-six granges. The size of a grange depended on the type of land, so that in North Wales, where it was mostly mountainous and barren, Aberconwy’s grange covered twelve thousand acres, whereas the average size of the granges in east Yorkshire was less than five hundred acres. In rural districts, where parishes might be far apart and ill-equipped, monasteries had always provided a pastoral ministry.

Scottish Cistercian monasteries such as Sweetheart and Glenluce operated a mission field covering much of southwest Scotland. The Augustinian canons, founded at the beginning of the twelfth century, supplemented the work of parish priests by combining extra-mural ministry with cloistered life. The main purpose of the monastery, however, remained the contemplation and worship of God within the abbey walls. Most monasteries, like Waverley, were slenderly endowed and remained poor throughout their first century. The building of the magnificent abbey church of Rievaulx, together with the equally impressive complex of cloisters, refectories, kitchens, infirmaries and dormitories, left the monastery deep in debt.

Forty-three; The White Ship Disaster and Succession Crisis, 1120-35:

The death of Henry I of England in 1135 left another disputed succession in England. Prince William, King Henry’s only legitimate son and heir, had perished in the wreck of the White Ship in 1120 and Henry’s second marriage, following the death of Matilda of Scotland, to Adeliza, the daughter of Geoffrey of Louvain, failed to produce a new male heir. In an attempt to secure the succession of his daughter, Empress Matilda (so-titled because she had inherited the German Empire from her first husband), Henry extracted an oath of allegiance to her from the Anglo-Norman barons in December 1126.

But Stephen, younger brother of Theobold II, Count of Blois, laid claim to the Crown on the pretext that Matilda’s mother had taken holy orders as a nun, and therefore that her marriage to Henry was null and void, meaning that Matilda was also illegitimate. This was despite Archbishop Anselm’s ruling before her marriage and coronation. Henry did little to ensure her succession apart from the oath, but her uncle, David I of Scotland, was among the first to take the oath.

Empress Matilda remained a popular choice in Wessex and West Mercia, acquiring the epithet, Lady of the English, an echo of the title given by the Mercians to Aethelflaeda two centuries previously. But her popularity did not extend to the Anglo-Norman barons and élite of London. Although the Saxons might support the concept of a female monarch, Stephen’s Norman supporters would not. Moreover, Matilda’s second marriage to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, a traditional and much-hated enemy of the Norman aristocracy, provoked criticism from them, so that the question of the succession was, in reality, far from settled. There were alternative candidates but Stephen of Blois, Henry’s nephew, emerged as a favourite and seized the throne in the confusion that followed the king’s death.

One of the nobles who played a major role in this seizure of the English Crown was Hugh Bigod, who had succeeded to his brother’s estates in East Anglia after the latter had been drowned in the White Ship disaster of 1120. Bigod had plenty of scope for self-aggrandisement and coat-turning during the era of the Anarchy after 1135. Hurrying back from Rouen, where he had been attending the dying King, Hugh convinced the Archbishop of Canterbury that, on his deathbed, Henry had nominated Stephen as his heir. He did this not out of respect for Henry’s dying wishes, but because he saw Stephen as a weak man whom the barons could easily manipulate. As soon as these expectations proved unfounded, Bigod raised the standard of revolt at Norwich. There he was besieged by Stephen and forced to surrender. However, Stephen pardoned the troublesome baron with more charity than wisdom.

Stephen acted quickly, and took ship to London, where he was received by many as king, and hurried on to Winchester to secure the reins of government and the royal treasury. The result was a prolonged civil war in England, from 1139 to 1153, which extended into Scotland and Wales. Although many of the barons immediately declared for Stephen, there was opposition from the start in England, Wales and Scotland.

Forty-four – Durham, 1135-39; King in the North – The Anarchy.

At first, Stephen reigned securely throughout the entire Anglo-Norman realm, but then the Welsh, subdued under Henry I, revolted, while David seized Northumbria.

David had continued to support the claim of his niece to the English throne, bringing him into conflict with Stephen of Blois, and when Stephen was crowned on 22 December 1135, David declared war on him. Though some contemporary chroniclers claimed that he acted opportunistically, to protect his lands in northern England, dynastic hostility towards Stephen was also part of his effort to uphold the legacy of Henry I and the inheritance of House of Wessex. David carried out his wars in Matilda’s name, sometimes risking his own throne in the process.

Before December 1136 was over, David had marched into northern England, and by the end of January, he had occupied the castles of Carlisle, Wark, Alnwick, Northam and Newcastle. Stephen was forced to march north, arriving there with a large army at the beginning of February, which halted the Scottish advance. David was at Durham, where he was met by Stephen’s army. Rather than fight a pitched battle, a treaty was agreed by which David would retain Carlisle while his son, Henry, was re-granted half the lands of the earldom of Huntingdon, territory which had been confiscated.

Stephen would regain the other captured castles; and while David would do no homage for the re-granted lands, Stephen would receive his son, Henry’s homage both for Carlisle and the other English territories regained. These over-generous concessions in subsequent negotiations encouraged David to doubt the new English king’s resolution in pursuing affairs of state. The issue of Matilda’s succession was not mentioned; however, this first Durham treaty quickly broke down after David took insult at the treatment of Henry at Stephen’s court.

When the winter of 1136-37 was over, David prepared to invade England again. The King of the Scots massed an army on the Northumberland border, to which the English responded by gathering their forces at Newcastle. Once more, they avoided a pitched battle, and a truce was agreed upon until December when David demanded that Stephen hand over the whole of the old earldom of Northumbria. Stephen’s refusal led to a third Scottish invasion, this time in January 1138, when Stephen was forced to march north again.

Stephen’s army disintegrated through maladministration and betrayal in a brief campaign during which the Lowlands were due to be ravaged as an object lesson to the rest of Scotland. The ferocity with which the Scots army then invaded that January and February shocked the English ‘chroniclers’. Richard of Hexham called the Scottish force:

… an execrable army, savager than any race of heathen yielding honour to neither God nor man, (that) harried the whole province and slaughtered everywhere folk of either sex, of every age and condition, destroying, pillaging and burning the villes, churches and houses.

The same chroniclers (‘propagandists’ might be a more appropriate epithet) painted a lurid picture of routine enslavements, killings of churchmen, women and infants, and even cannibalism. In February, King Stephen marched north, but the two armies avoided each other and he was soon on the road south again. In the summer, David decided to split his army, sending a column into Lancashire, under his nephew William, while he harried Furness and Craven in advancing to Newcastle. On 10 June, William Fitz Duncan met a force of knights and men-at-arms near Clitheroe, and a pitched battle took place in which the English army was routed.

Later that summer, the influential English baron Eustace Fitz John went over to David, taking with him his castles at Alnwick and Malton. This encouraged the Scots to launch yet another and even greater offensive, with their army bolstered by reinforcements from the north and west. Stephen’s attention was fully occupied with rebellions in the south, and the defence of the north was left to Archbishop Thurstan of York. But in allowing his Galloway troops to plunder the countryside, David had overplayed his hand and the northern English barons united against him to put an end to the repeated Scottish forays.

Responding to Bishop Thurstan’s appeal for a crusade against the Scots to gather at Thirsk, the armed strength of the North mustered at York, preceded by the banners of St Peter of York, St John of Beverley and St Wilfred of Ripon, flying from a mast mounted on a carriage. The English army then moved north on the road through Northallerton to Darlington.

By late July 1138, two Scottish armies had reunited in St Cuthbert’s land, in the lands controlled by the Bishop of Durham, on the north side of the River Tyne. Another English army had mustered to meet the Scots, led by William, Earl of Aumerle. The Scots refused an offer of negotiations and the northern English army advanced to intercept them at Northallerton. Inspired by his victory at Clitheroe, David decided to risk battle. David’s force, apparently 26,000 strong, was far larger than the English army when the two forces met on Cowdon Moor near Northallerton (North Yorks).

Despite their strength in numbers, The Battle of the Standard, as it came to be known, was a defeat for the Scots. Early in the morning of 22 August, the Anglo-Normans occupied the southernmost of the two hillocks standing six hundred yards (550 metres) apart, to the east of the Darlington road. The carriage supporting the sacred standards was positioned on the southern summit and the English troops deployed in their defence. They formed in three groups with a front rank comprising dismounted men-at-arms and archers, a solid body of knights around the standards, and shire levies deployed at the rear and on each flank. At some distance to the south of the hill, a small number of mounted troops stood guard over the army’s horses.

The Scots drew up on the northern hillock with men-at-arms and archers to the fore and the poorly-equipped Gallwegians and Highlanders in the rear. The men of Galloway were incensed by their deployment and demanded to be repositioned in their customary place at the front of the battle line. Unwisely, for once, David gave his assent to their demand and the unarmoured Gallwegians formed the highly vulnerable spearhead of the attack. The troops from Strathclyde and the eastern lowlands formed on the right under David’s son Prince Henry, who also commanded a body of mounted knights. The left was predominantly West Highlanders and to the rear stood a small reserve under the Scots’ King with men from Moray and the East Highlands.

The men of Galloway opened the attack, charging through a hail of defensive fire from the Norman archers with such impetuosity that they temporarily broke the Norman front rank. The depth of the Anglo-Norman formation, however, made further penetration impossible and the Gallwegians were gradually pushed back. Despite repeated assaults, they were unable to make a decisive lodgement in the English ranks and Prince Henry attempted to break the stalemate with a mounted charge. Despite heavy losses of knights, his thrust was so successful that his cavalry crashed straight through the English lines and carried their charge in the direction of the tethered horses and Northallerton.

Before the Scottish infantry could take advantage of the passage created by their cavalry, the English had closed ranks and the Scots met a solid shield war. Prince Henry was marooned to the rear of the English army and unable to break away to the north. The Scottish left and the King’s reserve were unwilling to renew the offensive and many of their infantry began to leave the field.

Admitting defeat, David and his bodyguard joined the retreat leaving only a small company of knights to cover his army’s retreat. The Anglo-Norman deployment did not lend itself to the rapid exploitation of the Scots’ retreat and there seems to have been no attempt to harry or pursue them.

David retired to Carlisle, with his surviving notables, and having retained the bulk of his army, and therefore the power to go on the offensive again. He marched north to join the Scottish troops who had been attempting to reduce the castle at Wark. The siege, which had begun in January, continued until it was captured in November, and David continued to occupy Cumberland as well as much of Northumberland.

Satisfied that the Scottish threat had been successfully parried, Stephen’s army had temporarily dispersed, leaving only a baronial contingent in the field to besiege Eustace Fitz John’s castle at Malton. The ease with which the Scots were able to roam the northern counties demonstrated that the border country needed further fortification. Therefore, despite the defeat at Northallerton, David I was able to hold the frontier of his domain at the rivers Tees and Eden.

On 26th September 1138, David called together his kingdom’s notables, bishops and abbots. Cardinal Alberic, Bishop of Ostia, was also there and played the role of peace broker, and David agreed to a six-week truce which excluded the siege of Wark. A settlement was agreed in April, in Durham. David’s son Henry was restored to all his northern English lands and the earldom of Huntingdon, while David kept Carlisle and Cumberland. Stephen was to keep control of the castles of Bamburgh and Newcastle. This effectively delivered all of David’s official war aims and he attained dominion over all of England’s north-west along the River Ribble and the Pennines, and the north-east as far as the Tyne.

Forty-five – May 1139; Westminster & Winchester – Matilda’s Return:

By 1139, Robert of Gloucester, Henry I’s illegitimate son, had joined his half-sister, providing Matilda with a base in the west of England to accompany the lands held on her behalf in the North, Midlands and Wales. He then stood by her when she landed in England in 1139. The arrival in England of Empress Matilda allowed David to renew the conflict with Stephen. In May or June, David travelled to the south of England and entered Matilda’s company, and he was present for her expected coronation at Westminster Abbey. However, this never took place due to the hostility of the Norman élite in the capital. David therefore remained at Winchester until September when the Empress found herself surrounded there.

Now there were two rival courts in England, and a stalemate ensued. However, David’s control of northern England was confirmed. The castles at Bamburgh and Newcastle were again brought under his control, while his son brought all the senior barons of Northumberland into his entourage. David took over and rebuilt the English fortress at Carlisle, which quickly replaced Roxburgh as his favourite residence. His acquisition of the mines at Alston on the south Tyne enabled him to begin minting the Kingdom of Scotland’s first silver coinage.

Stephen became the hated usurper, especially in the North of England, where the conflict reopened many of the unhealed sores of the Conquest and the hatred between Norman and Anglo-Danish noble families. Stephen spent the rest of his reign in England struggling with Matilda’s supporters. For the best part of two decades, most of England and parts of Wales were embroiled in a deeply divisive civil war, a period when, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Men said openly that Christ and his saints slept. There, and in other chronicles, the record told of war and waste, pestilence and famine, castle-building, oppression and torture. After the long peace of Henry I’s reign, the vocabulary of the Conquest had returned.

In 1140, Stephen granted Herefordshire and its earldom, to Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, but excluded the lands and obligations of Hugh Mortimer and two other barons from Robert’s jurisdiction. The Wigmore Chronicler tells of Hugh’s continual feuds with Miles, Matilda’s nominee as Earl of Hereford. Whether or not the account of a private war is accurate, it vividly portrays the anarchic state of the Marcher lordships during the 1140s.

In addition, the Marcher lords became disillusioned with Stephen’s weak policy towards Wales and his inability to sustain his barons there. Many of them went over to Matilda as prospective queen in the civil war, but Hugh Mortimer appears to have been an exception, since the problem for many Norman magnates was that Matilda had married Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou. The counts had for generations been rivals of the dukes of Normandy and many Norman barons in England with lands in Normandy now feared that, as by Norman law Matilda’s rights and property would pass to her husband, the Duchy would fall under the control of Geoffrey of Anjou. They therefore supported Stephen’s claim to Normandy and by extension to the Kingdom of England.

Nonetheless, Hugh Mortimer seems to have played little or no part in supporting Stephen on the national stage; his priorities were rather his interests in the March and the Anglo-Welsh border counties where he succeeded in reconquering Maelienydd in 1144 and was able to rebuild his castle of Cymaron. The Welsh chroniclers relate that in 1145-8 he captured the Welsh prince Rhys ap Hywel and later had him blinded.

Forty-six; The Siege of Lincoln, February 1141:

Stephen’s treaty concessions to the Scots, particularly the ceding of Northumbria, drove Ranulf Earl of Chester to rebellion as he considered the lordship of Carlisle and Cumberland to be part of his inheritance. Ranulf seized the castle of Lincoln and the town’s citizens appealed to the King for aid. Stephen and his army arrived at Lincoln on 6 January 1141 and although the speed with which the King had acted took the defenders by surprise, he was not able to prevent the Earl slipping away to Cheshire to raise troops. Ranulf also appealed to his father-in-law, Robert Earl of Gloucester, and promised loyalty to the Empress. Eager to exploit both the opportunity and the resources of his new ally, Robert quickly mustered his forces for a march on Lincoln. Earl Ranulf, with an army of his Cheshire tenants and Welsh mercenaries, joined Robert in Leicestershire and despite the restrictions on mobility imposed by the winter season, they were before Lincoln by 1 February.

Their immediate problem, as ever, was the crossing of the waterways, the Fossdyke and the River Witham, which lay between the rebel army and the castle. It appears most likely that the rebels marched some way to the west of the city walls and stormed across a ford on the Fossdyke which was inadequately guarded by Stephen’s troops. Once over on the Lincoln side of the dyke, the Earl’s army deployed for battle.

The Council of War summoned by Stephen to discuss the rebel threat was divided, the older nobles advising the king to garrison the city and withdraw to raise a larger army, the younger barons urging immediate battle. Stephen chose the latter course and deployed his army from the West Gate on the slope down to the Fossdyke. He formed his army in three divisions, with cavalry on both flanks and infantry in the centre. On the right-hand side were the followers, among others, of William de Warenne and Hugh Bigod, Earl of Norfolk. On the left, Stephen’s mercenary captain, William of Ypres deployed a contingent of Flemish and Breton troops alongside the troops of William of Aumerle. In the centre were elements of the shire-levy of the citizens of Lincoln.

The rebel army also deployed in three divisions, with disinherited nobles on the left, infantry levies and dismounted knights in the centre under Earl Ranulf, and cavalry under Earl Robert on the right. The lightly-armed Welsh were deployed in front of Robert’s cavalry. The rebels were the first to advance, moving forward with swords drawn, intent on close-quarter combat. On Stephen’s right, the Earls’ men fled the field rather than face butchery or capture, while on his left, Ypres and Aumerle rode down the Welsh and crashed into Earl Robert’s cavalry. At this crucial moment, the infantry of the rebel centre was able to intervene and the remaining cavalry under Stephen recoiled in panic which gave way to rout.

Though surrounded, the King and his guard fought their way out of their isolation, with Stephen himself prominent in the savage hand-to-hand combat that followed. Wielding his sword, and then a battle-axe, Stephen became the focus of resistance until struck down by a stone and captured by William de Cahaignes. The latter’s cry of Here, everyone, here! I’ve got the King! brought the fighting to an end. It was a total defeat for Stephen followed by the burning and pillage of Lincoln, whose citizens were slaughtered indiscriminately by the victorious rebels.

Stephen was conveyed to Bristol as a prisoner but although Matilda’s coronation as Queen now appeared only a matter of time, her assumption of the prerogatives of state alienated the citizens of London, causing many of them to confirm their allegiance to Stephen by joining an army raised by Stephen’s queen which routed Matilda’s forces at Winchester. By November 1141, Stephen had been freed.

David’s many successes in battle were in many ways balanced by his failures off the battlefield. His greatest disappointment was his failure to gain control of the Bishopric of Durham and the Archbishopric of York. He had attempted to appoint his chancellor, William Comyn to Durham, which had been empty since the death of Geoffrey Rufus. However, he was unlikely to secure the support of the Papal legate, Henry of Blois, Bishop of Winchester and brother of King Stephen. Despite obtaining the support of Matilda, David was unsuccessful in securing Comyn’s election to the see.

David also failed in his attempt to secure the succession to the Archbishopric of York. William Fitzherbert, King Stephen’s nephew, found his position undermined by the collapsing political fortunes of Stephen in the north of England and was deposed by the Pope. David used his Cistercian connections to build a bond with Henry Murdac, the new archbishop. Despite the support of Pope Eugene III, advocates for King Stephen and Fitz Herbert prevented Murdac from taking up the post at York.

Forty-seven – 1143; The Advent of the Angevins:

By 1143, Geoffrey of Anjou had won control of Normandy south of the Seine and the next year he subdued the remainder of the Duchy. Geoffrey Plantagenet’s victory in Normandy and his assumption of the title of duke placed the Anglo-Norman barons in a dilemma. Lords with interests in both England and Normandy who continued to support Stephen could hardly expect to retain their honours in Normandy. Those lords whose interests in Normandy were more important than those in England, and whoever therefore did homage to Geoffrey and by inference to Matilda, jeopardised their English interests in the parts of the kingdom where Stephen’s writ ran. Some withdrew from the quandary by joining the Second Crusade, but others like Hugh Mortimer reconciled their divided loyalties and preserved their family’s status in both dominions.

Meanwhile, Matilda’s husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, having overrun Normandy, was proclaimed its duke in 1144, winning papal and French support for the Duchy to pass to their son Henry in 1151. It looked as if the Anglo-Norman realms would be split permanently between the two camps, even after Henry invaded England in 1152.

It took the death of Eustace, Stephen’s heir, to break the stalemate: by the Treaty of Winchester (December 1153), Stephen acknowledged Henry Plantagenet as his heir and died within a year, bringing the protracted civil war to an agreed end, and securing for Henry the first undisputed succession to the English throne for more than a century.

In 1149, Henry Murdac had again sought the support of David, who seized on the opportunity to bring the City and Archdiocese of York under his control, and duly marched on the city. However, Stephen’s supporters became aware of David’s intentions and informed Stephen, who himself marched to the city and installed a new garrison. David decided not to risk such an engagement and withdrew. If his intention, as some have suggested, was to bring the whole of ancient Northumbria into his dominions, this event turned the tide against him, and…

… the chance to radically redraw the political map of the British Isles was lost forever.

Nevertheless, David had expanded his control across Northern England, despite defeat at the Battle of the Standard in 1138. He was an independence-loving king trying to build a Scot-Northumbrian realm by seizing the most northerly parts of the English Kingdom. David’s support for Matilda can therefore be seen not so much as a pretext for land-grabbing but as the result of his own descent from the House of Wessex. His son’s descent from the Earls of Northumberland encouraged him in this project which came to an end when his successor was ordered by Henry II of England to hand back the most important of his northern English gains.

Forty-eight – Spring, 1153, Rievaulx & Carlisle; the Scottish Church, David’s Death and the Black Cross:

The Scottish church historians usually acknowledge David’s role as the defender of its independence from claims of overlordship by the Archbishops of York and Canterbury. Aelred of Rievaulx wrote in David’s eulogy that when he became king, …

… he found three or four bishoprics in the whole Scottish kingdom (north of the Firth of Forth), and the others wavering without a pastor due to the loss of both morals and property; when he died, he left nine, both of ancient bishoprics which he himself restored and new ones which he erected.

However, although he moved the bishopric of Mortlach east to Old Aberdeen and arranged for the creation of the Diocese of Caithness, no other bishopric can truly be called David’s creation. The bishopric of Glasgow was restored, with David appointing his reform-minded French chaplain to it, and assigning all the lands of his principality except those in the east already governed by the Bishop of St Andrews. David was also partly responsible for forcing semi-monastic bishoprics like Mortlach (Aberdeen), Brechin, Dunkeld and Dunblane to become fully episcopal and firmly integrated into a national diocesan system.

In addition, some of these changes to ancient monastic foundations were sometimes made at the expense of the original Celtic settlements. Bishop Robert of St Andrews, with the agreement of David, dispossessed the Celtic monks or Culdees in order to place the most sacred relics of Scotland in the care of Augustinian canons. Robert built a church dedicated to the Syrian monk St Regulus, who had reputedly brought the bones of St Andrew to the site in the fourth century. In northern England, the abbeys of Rievaulx, Fountains and Byland in North Yorkshire were all built at this time, and among the daughter houses of Rivaulx was Melrose, established by David I on the place where Aidan had founded his first monastery in Scotland, on the Tweed.

David was one of medieval Scotland’s greatest monastic patrons. He founded more than a dozen new monasteries during his reign as King of Scotland, patronising various new monastic orders. Not only were such monasteries an expression of David’s undoubted piety, they also helped to transform Scottish society. Monasteries became centres of foreign influence and provided sources of literate men, able to serve the crown’s growing administrative needs. The Cistercian monasteries in particular helped to introduce new agricultural practices. They transformed southern Scotland into one of northern Europe’s most important sources of sheep wool.

As for the development of the parochial system, Scotland already had an ancient system of parish churches dating from the early Middle Ages. The kind of system introduced by David’s Normanising reforms was concerned with making the Scottish church as a whole more like that of France and Norman England in a piecemeal fashion, rather than carrying out more radical restructuring.

From the beginning of his reign, David had to deal with the problem of the archepiscopal status of St Andrews, which since the eleventh century had acted as a de facto archbishopric, but never made de jure by the Pope. This opened the way for the aggressively assertive Archbishop of York, Thurstan, to claim overlordship over the entire Scottish church. Added to this, the bishopric of Glasgow was south of the river Firth and neither regarded as part of the Kingdom of Scotland nor in the jurisdiction of St Andrews.

In 1125, the Pope had written to the Bishop of Glasgow urging him to submit to York. David ordered Bishop John to travel to Rome to secure a pallium which would elevate St Andrews to an archbishopric with jurisdiction over Glasgow. In the end, David gained the support of Henry I, and York’s claim over the bishops north of the Firth was quietly dropped for the rest of David’s reign, although York maintained its claims over Glasgow.

The greatest blow to David’s ecclesiastical and secular plans came on 12 July 1152 when Henry, Earl of Northumberland, his heir, died, after suffering from a long-term illness. David must have known that he had not long to live, as he arranged for his grandson, Malcolm IV, to be made his successor, and for his younger grandson, William, to be made Earl of Northumberland. While the eleven-year-old Malcolm was taken on a tour of the kingdom by the senior magnate and future rector (regent) Donnchad I, David’s health deteriorated rapidly in the spring of 1153, and he died at Carlisle Castle on 24th May.

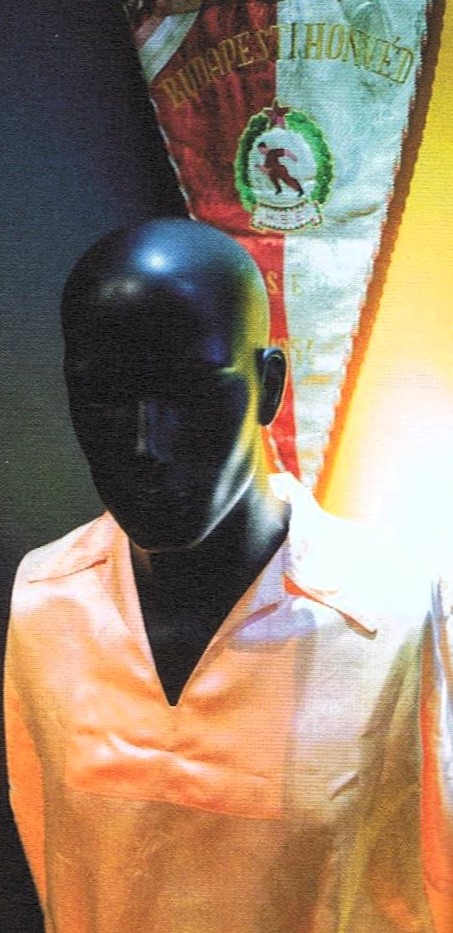

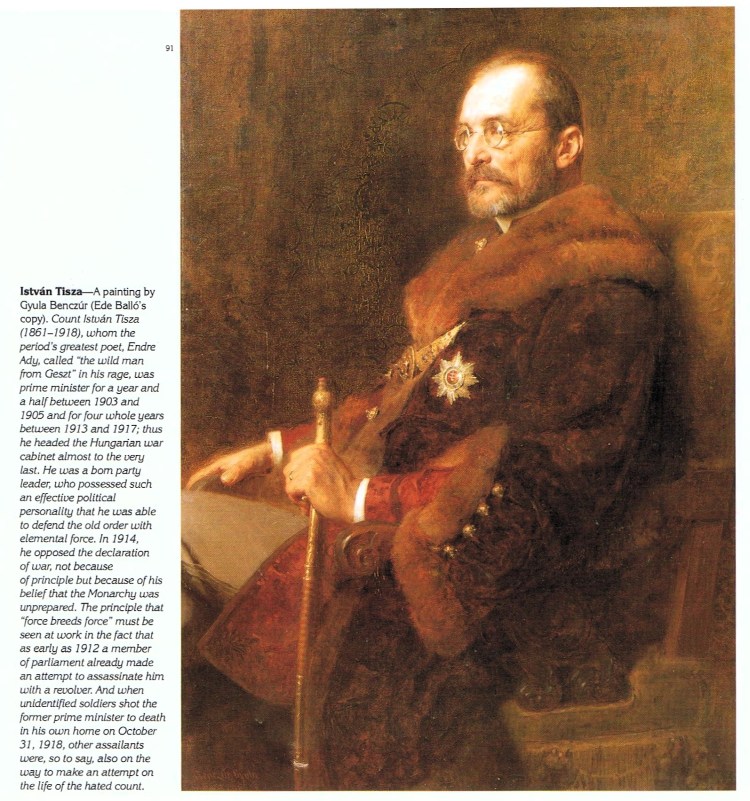

On his deathbed, David asked for his mother’s black cross, which had originally belonged to Gizela, István’s Queen in Hungary, showing once again the importance of the Árpád dynasty heritage. In his obituary, he is called Dabid mac Mail Colaim rí Alban, Saxan (David, son of Malcolm, King of Scotland and England). The title not only acknowledged his English lands, but also his ancient Wessex heritage. He is recognised as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church but was never formally canonised, unlike his mother, Saint Margaret of Scotland, who was canonised in 1249. Aelred of Rivaulx, his courtier, praised David for his justice and piety, urging Henry Plantagenet, his Anglo-Angevin nephew to follow his example in kingship.

(to be continued…)