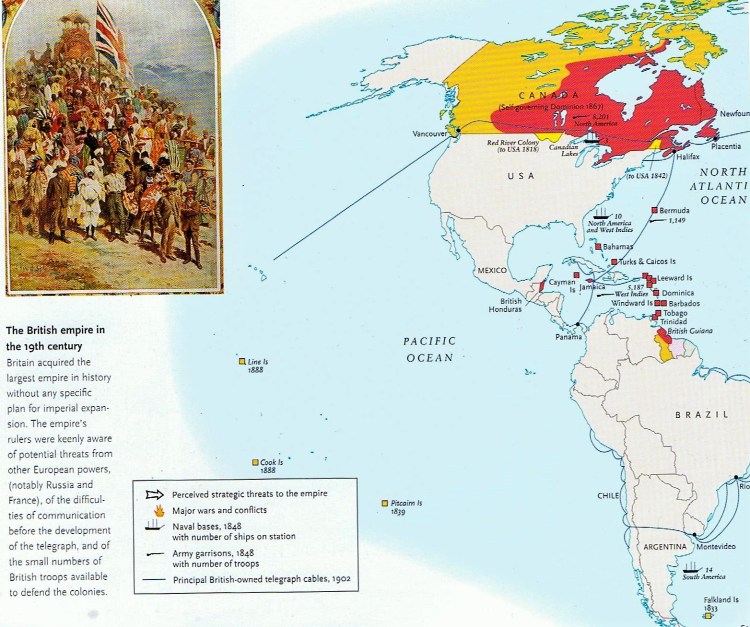

An ‘Outbreak of Democracy’?:

In his 1961 work on The Levellers and the English Revolution, H N Brailsford wrote that:

… there has been nothing like this spontaneous outbreak of democracy in any English or continental army before this year of 1647, nor was there anything like it thereafter till the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils met in 1917 in Russia.

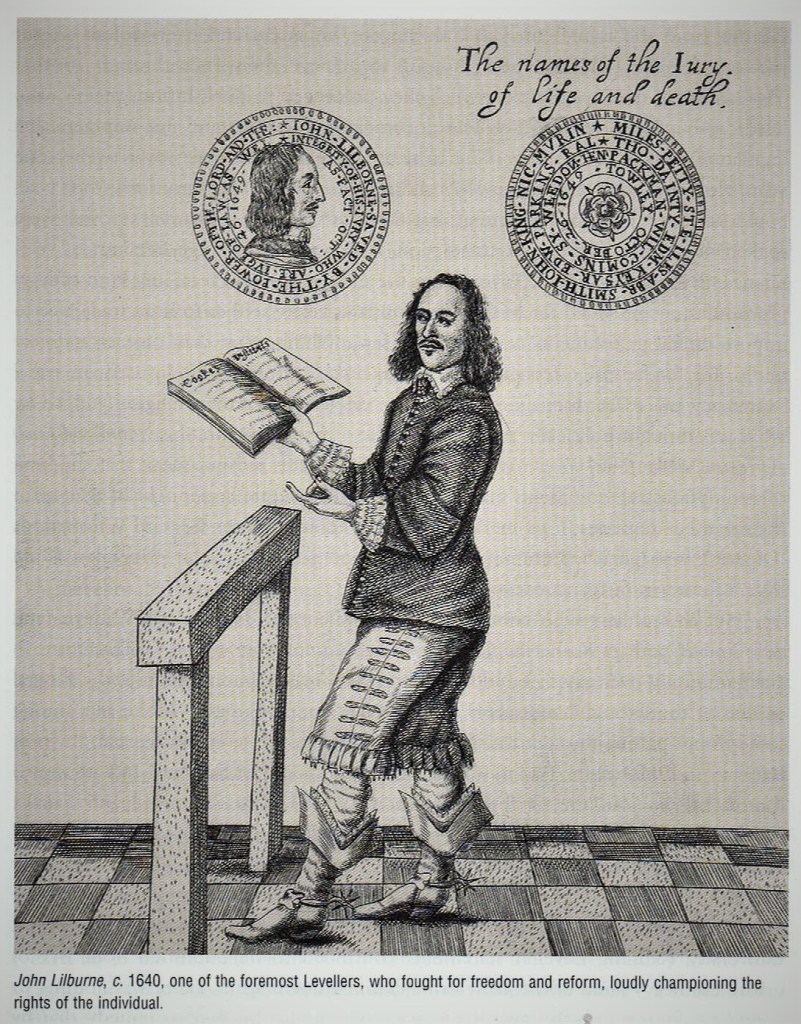

The rank and file organised themselves from below, led by the yeoman cavalry regiments. Petitions were drafted, like the one from Colonel Hewson’s regiment, some of them dealing with political matters as well as military grievances. In the summer of 1647 the ‘Agitators’ had their own printer, a Leveller, John Harris; at the height of their influence his became an official army press. The army radicals also linked up with with their civilian counterparts. Petitions calling on the army to give a radical political lead also came in from London tradesmen as well as from the counties. The army had therefore advanced on London and entered upon a course of decisive political action, as already described in my previous ‘chapter’ in this series, and though it was now united under the command of Fairfax and Cromwell, the initiative for this action had come from the ‘rank and file’, including newly promoted or recruited officers who were in close contact with the London Levellers. The apprentices of London, under the influence of John Lilburne, who was still under arrest in the Tower, had also appointed ‘agitators’.

In the early autumn, the army commanders clearly signalled the limits to this radical ‘tide’ when Major Francis White, Agitator of Fairfax’s own regiment, had been expelled from the Army Council on 9 September for maintaining that there was now no visible authority in the kingdom but the power and force of the sword. This view was shared by others among the agitators and Colonel Rainborough, whom Gardiner described as the principal spokesman for this ‘third party’ among the officers, had also publicly expressed his anxiety about White being ‘kicked out’. White did not conclude, unlike the chaplain Hugh Peter, that any act of force was therefore justified. White set out his views at great length before Fairfax in 1647, repeated just over a year later. He held that all laws made since the Norman Conquest which were contrary to ‘equity’ should be abolished, and told Fairfax that his authority derived less from Parliament than from the ‘Solemn Engagements’ of the Army. The Levellers thought that the state had broken down in the course of the civil war; until it was legitimately refounded a state of nature existed in which the sword was the only remaining authority. But military force could justly only be used only to hand power back to the people.

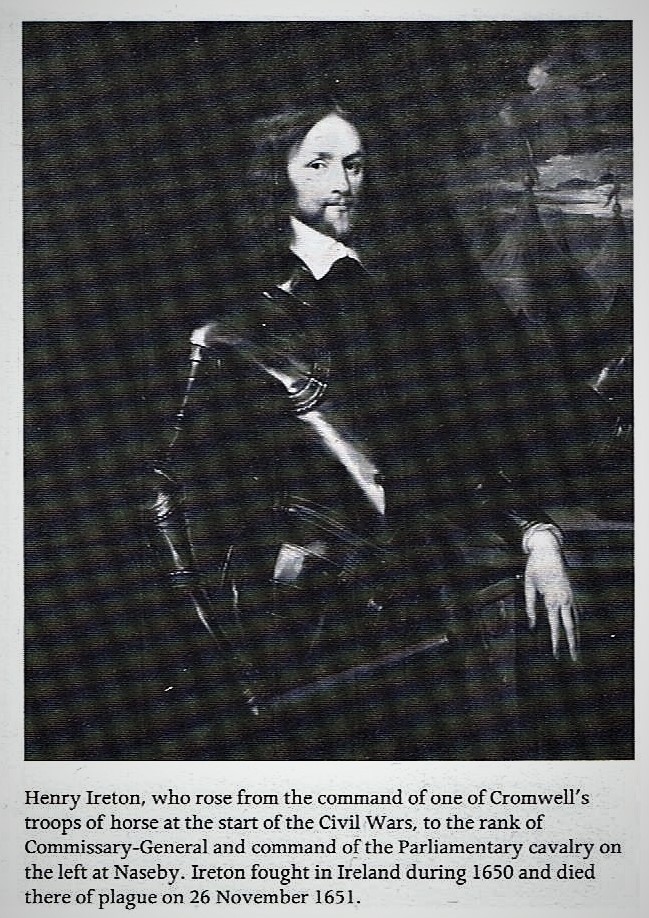

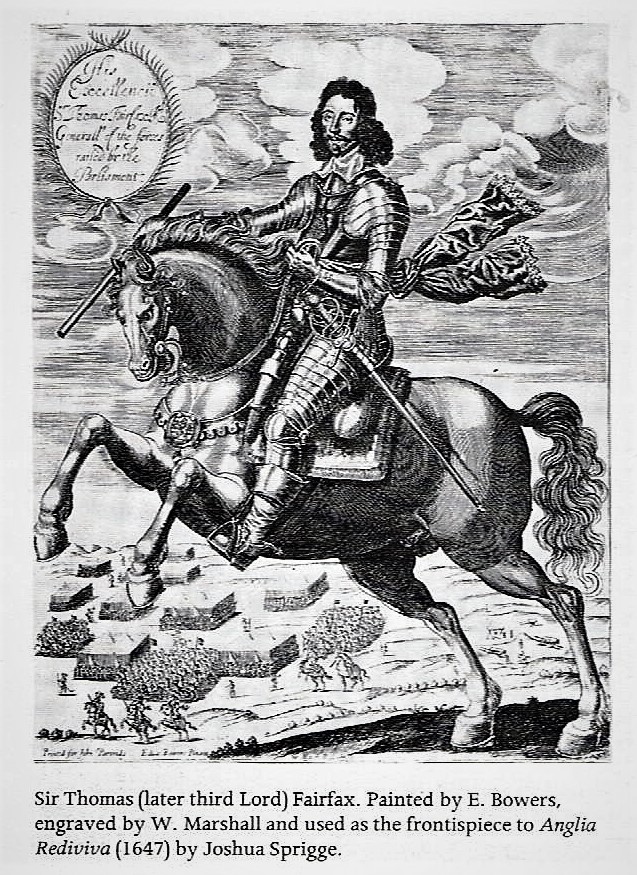

This was the purpose of the Agreement of the People, the Levellers’ new ‘social contract’ refounding the state, which was submitted to the Army Council in October 1647. It was discussed by officers and men at Putney in the days after 28 October. But even as the debates got underway, the agitators had lost the initiative they had gained from March to August. Agitators of five cavalry regiments had been recalled by their constituents, under suspicion of being corrupted by their officers; they had been replaced by new representatives, and it was these new agitators who presented their new document to the Army Council. What we do not know from the available documents is what the expectations of the agitators were. At one time agreement seemed to have been reached on a general rendezvous at which they intended to have the Agreement accepted by the whole army. It had been amended to include a substantial extension of the franchise to all soldiers and to all others except servants and beggars. The current ‘state of nature’ was to be ended and the English commonwealth was to be restored as a democracy. For the senior officers, the debates in the army held at Putney in late October into early November took a very different course from that expected. Fairfax, Cromwell and Ireton had hoped that the General Council would reject the the accusations in The Case of the Army, reaffirm the basic unity of the army’s purpose, and get on with business of agreeing a set of terms that could be put to the king in its name.

In the event, what trooper Robert Everard, a new agent in Cromwell’s own regiment, brought to headquarters on the day before the General Council’s next meeting, however, was an entirely new document, approved that same day by by a meeting of the five regiments, together with other soldiers and some civilian Levellers, including Wildman, who was deputed to speak for it before the General Council. It seems to have been put together in order to steal the initiative for the Leveller’s broader aims before the army’s representative body. It seems to have been written by Wildman and William Walwyn. When Cromwell read it, he concluded that there were ‘new designs a-driving’ and that the General Council would have to thrash them out. Whereas The Case of the Army had set out a programme for action in the specific circumstances of early October, the Agreement of the People dealt in first principles, further widening the gap between its authors and the leaders of the army. The ‘Grandees’ – Fairfax, Cromwell and Ireton – were still seeking a settlement based on the ancient constitution and fundamental laws of England, albeit in radically modified form. These would have the binding consent of King, Lords and Commons.

The Levellers, by contrast, had come to regard the existing laws as very largely a legacy of ‘the Norman Yoke’, and now that the ‘freeborn’ English had defeated the last remnants of the Conquerors successors, they claimed that it was only the free people of England who could legitimate a new, valid constitution. The Agreement was their means to this end, offered as something altogether as something higher than a statute, which future parliaments could modify or repeal. It was intended to be a declaration of the principles on which future parliaments would be bound to operate. The people’s representatives in parliament would have full power without the consent of or concurrence of any other person or persons, to make laws, appoint offices of state and magistrates ‘of every degree’, declare war, make peace and to do everything that a sovereign people did not reserve to themselves. Their power was inferior only to theirs that choose them, but some rights were so ineradicably planted by ‘natural law’ that even their chosen representatives would be prevented from infringing them. Those affirmed in the Agreement included freedom of religion, immunity from conscription, and total equality before the law, regardless of birth, rank or tenure. Parliament itself should be reformed by reapportioning constituencies according to the number of inhabitants, not their contribution to taxation, as Ireton had suggested in the Heads of Proposals. However, the Agreement itself did not deal specifically with the Crown or the Lords. Woolrych has commented that It is a document as remarkable for its silences, which were doubtless deliberate, as for its prescriptions.

The fact that Cromwell, presiding (Fairfax being unwell again), caused the debates engendered by the Agreement to be recorded almost verbatim shows that he and Ireton were well aware of how much hung on their outcome. They were taken down by the aptly-named William Clarke, a Londoner of humble origin in his mid-twenties who had risen in the army secretariat and was now secretary to its General Council. He had mastered an early form of shorthand from which he later transcribed. At the General Council on 28 October, Sexby introduced the delegates from the new agents’ organisation: two soldiers, Robert Everard being one, and the civilian Levellers John Wildman and Maximilian Petty. He then told Cromwell and Ireton to to their faces that their credits and reputation hath been much blasted by their striving to please the king and their support of a parliament of rotten members. Very soon the fundamental difference of purpose between the army commanders and the Leveller group became apparent. The ‘grandees’ held themselves bound by their pledges to respect the authority of parliament and to seek a settlement with it or with a new parliament following the dissolution of the current one. On the other hand, the Levellers wanted the army to reoccupy London, dissolve parliament and inaugurate a new and revolutionary constitution, which could only be done by force. The prospect of the Agreement gaining enough subscriptions to give it democratic legitimacy if it was to be imposed by military dictatorship upon a nation yearning for peace and still devoted to its monarchy, were non-existent. It is little wonder then that the General Council was so divided. Many of those present, officers and soldiers alike, must have felt torn between the powerful attraction of high ideals on the one hand and a deep reluctance to divide the army on the other, in defiance of its senior commanders. Strong ties bound those who had fought together and who knew that they might have to do so again soon.

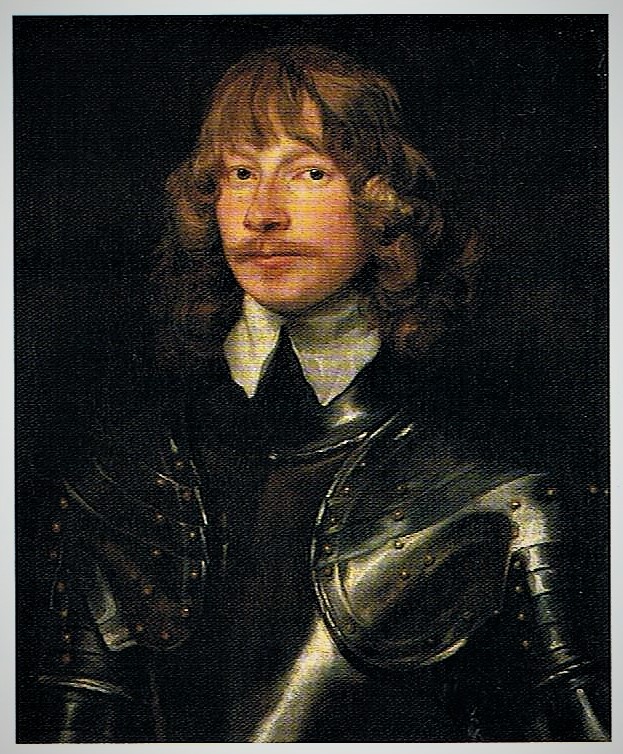

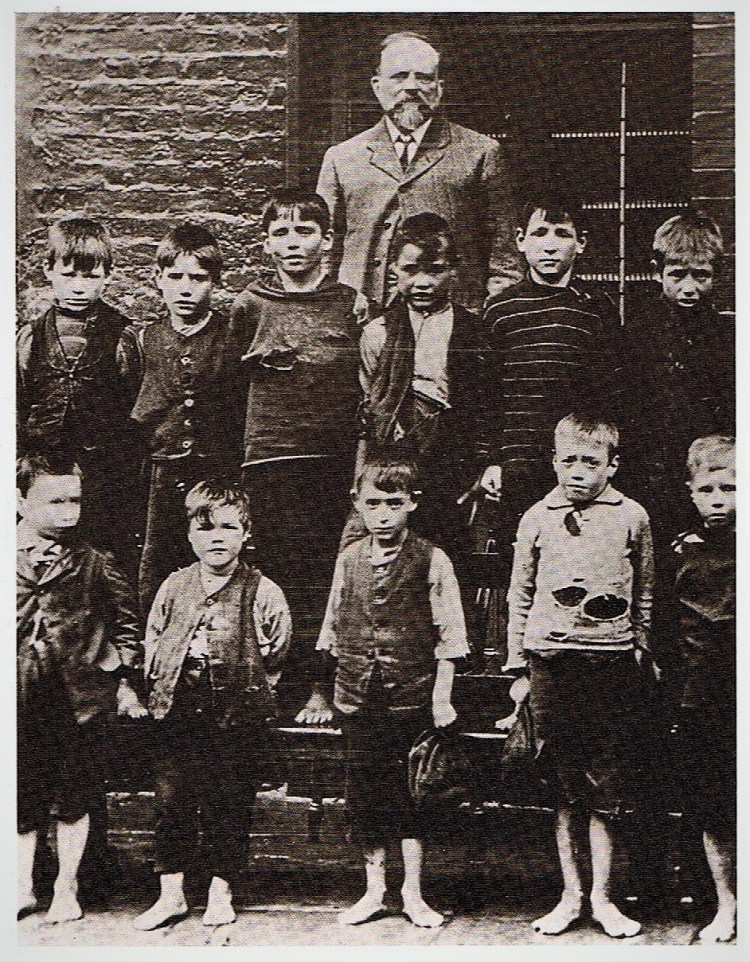

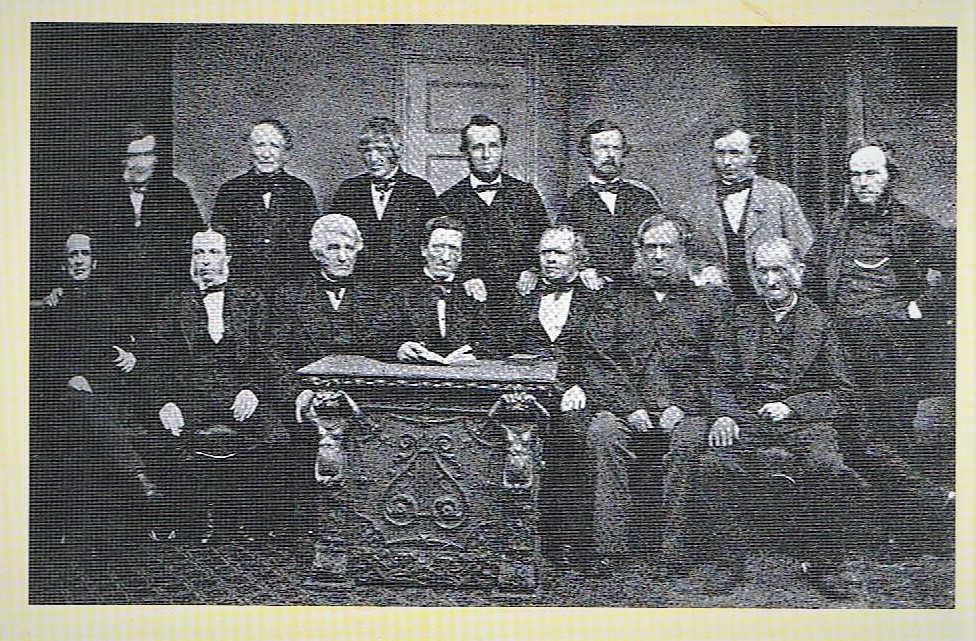

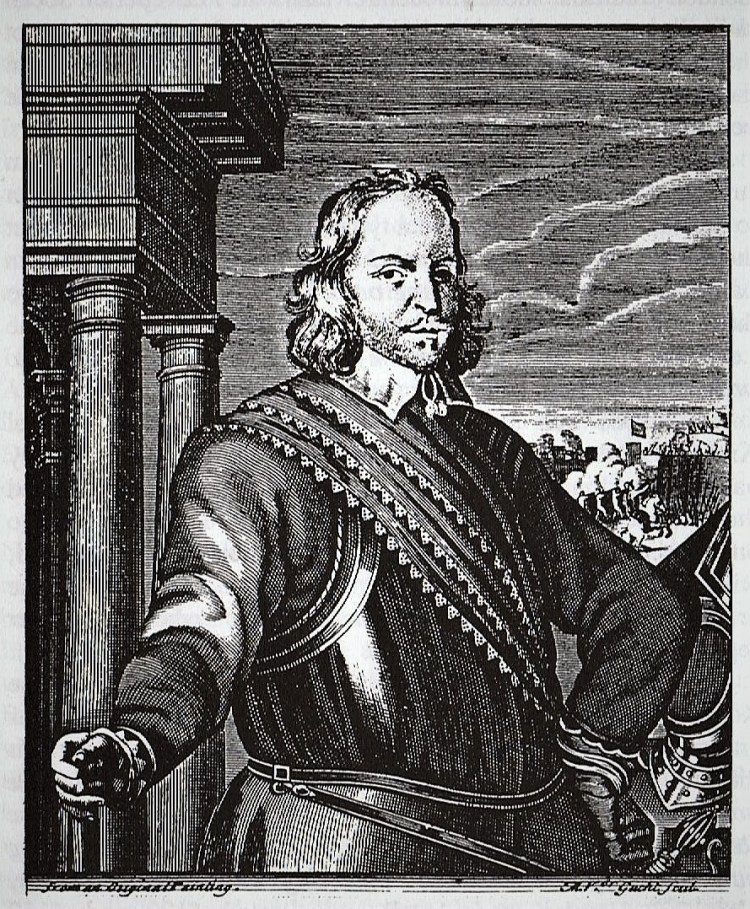

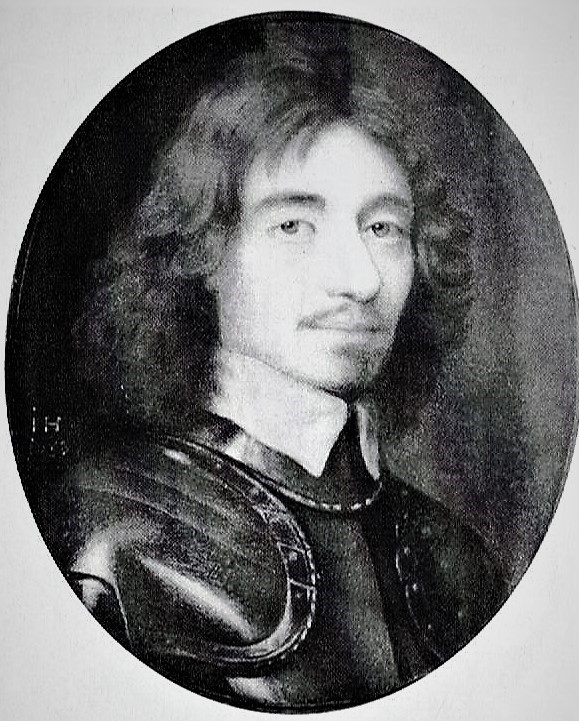

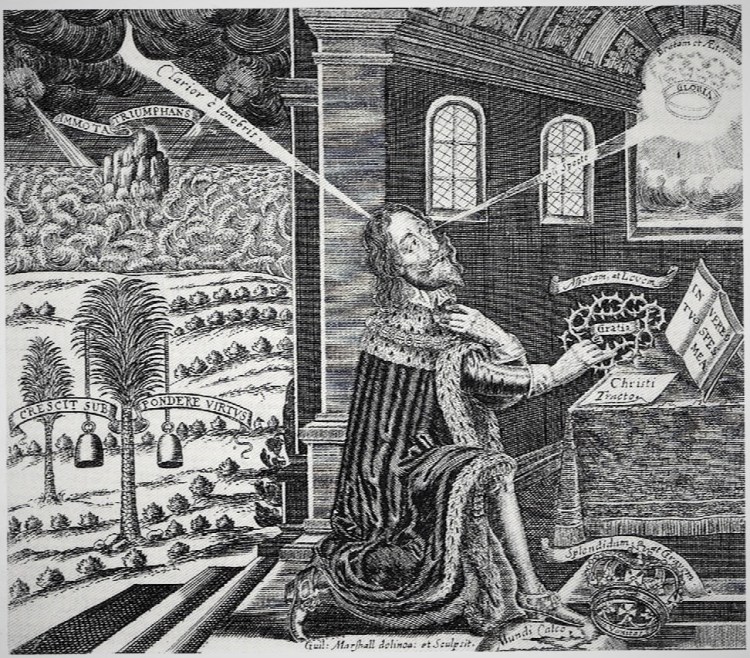

We lack evidence, however, about the sentiments of the rank and file, for the only soldiers recorded as having spoken during the three days of debate at Putney were Sexby, Allen, Lockyer, Everard and Jubbes. The last of these, recently promoted from Major to Lieutenant-Colonel in Hewson’s regiment on the death of its previous commander, Colonel John Pickering, was certainly committed to the Leveller’s political agenda along with at least three of the regiment’s captains. Earlier in the year, as political debate had intensified in the army throughout the summer and autumn, some in Hewson’s (formerly Pickering’s) regiment were clearly committed to the political agenda of the Levellers. In addition, there were at least two ordinary soldiers from the regiment, radical by reputation since its foundation in 1645, who were among the seventeen from nine regiments who had signed a letter on 21st June which went far beyond mere army grievances. But Jubbes was also interested in reconciling the Levellers with moderate Independents and even presbyterians, as he made clear in his brief contribution to the debates at Putney. His attitudes may have been tempered by his new commander, Colonel John Hewson (pictured below) who, though from a humble background himself, was soon to support Cromwell in moving against the Levellers in the army. Nevertheless, Jubbes remained critical of Cromwell and, disillusined with the course of the ‘revolution’ and its failure to bring ‘liberation’, he resigned his commission and left the army in April 1648, becoming a Fifth Monarchist. By that time, it was obvious that both he and the Levellers had lost the debate in the regiments and in the army as a whole. No doubt also disillusioned with the Leveller leader’s support for military dictatorship, Jubbes had also become a pacifist, like many others who were to form the early Quaker sect.

The Putney Debates & the Battle for the Army:

Although the Agreement was read to the General Council on the 28th, there was no debate on its contents on the first day. Cromwell and Ireton were doubtful as to whether the army should be considering such radical proposals at all. They argued that it was duty bound by its declarations made from June onwards, in which it had subjugated itself to the authority of parliament in exchange for the redress of its grievances, and that it also had a moral duty to to pursue the path of negotiation with both king and parliament on which it had already embarked. The Heads of the Proposals remained the basis for these, and they had not yet been fully and formerly considered by either party. For their part, the Leveller spokesmen contended that Parliament’s rotteness was manifest, that the king had forfeited any right to be further treated with, and that no engagements were binding if they stood in the way of the rights of the people; if the matters propounded in the Agreement were the people’s due, they stood self-justified. The outcome of the day’s debate was the appointment of a committee to sift the army’s declaration and itemise the commitments contained in them, so as to help help the General Council, in a special meeting in a few days’ time, to assess how far the Agreement‘s proposals were compatible with them. Cromwell’s attitude was conciliatory rather than confrontational; he assured the spokesmen for the Agreement that they would not find him and his fellow-officers wedded and glued to forms of government and readily acknowledged for his part that the foundation and supremacy is in the people, radically in them.

The famous debate on the 29th, in which the Leveller spokesmen joined issue with Cromwell and Ireton over the very foundations of a free commonwealth, came about almost by accident. On the previous day, Lieutenant-Colonel Goffe made an urgent plea that they should meet first for prayer. He probably spoke for many when he said that God had not been with them in their debates so far. This did not please some of the less religious Leveller leaders like Wildman, who spoke extensively at Putney, almost as much as Ireton. But there was wide support for the proposal, and it was agreed that the next morning should be given to prayer, with the committee convening in the afternoon. There was a big attendance at the prayer meeting, and testimonies were heard. When the Levellers arrived in the early afternoon to confer with the committee, they found a large and potentially sympathetic audience and wanted to launch a general debate on the Agreement there and then. Cromwell understandably opposed this proposal, stating that he and the others present had already spent several hours together in seeking the Lord. But several other officers supported it, including Colonel Thomas Rainborough, whom Cromwell and Fairfax had already incensed over his appointment as vice-admiral in the Navy and their consequent reassignment of his New Model regiment to another officer. Although brave, sincere and a genuine radical, his motives at Putney were somewhat clouded by personal antagonisms. Nonetheless, the support he garnered at that moment meant that Cromwell and Ireton had to bow to pressure; the Agreement was duly read out in its entirety once more, and then debated clause by clause.

If Cromwell and Ireton had had time to think and reflect, they might have furthered their most immediate object, which was to preserve the army’s unity and discipline, by focusing on those parts of the Agreement which commanded general consensus in it, such as liberty of conscience, equality before the law and the superior authority of the people’s representatives. Instead, Ireton seized upon the proposal to equalise constituencies on the basis of population meant that every male inhabitant had a right to vote. This was what prompted Rainborough’s memorable affirmation that…

… the poorest he that is in England hath a life to live, as the greatest he; and therefore… that every man who is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government.

Against him, Ireton (above) took his stand on the constitution of parliament from time immemorial and on the principle that only they who had a permanent fixed interest in this kingdom, whether as freeholders or as freemen of corporations, the latter being mostly substantial traders. Liberty cannot be provided for in a general sense if property be preserved he asserted, and added I would have an eye to property. This led to a gladatorial contest with Rainborough; for at least half an hour no one else got a word in, and both made long speeches after that. Sexby and Wildman also contributed substantially, and there is no doubt that the Leveller case commanded more sympathy than Ireton’s. Sexby was passionately eloquent on behalf of his fellow-soldiers in challenging the claim that only those with a fixed estate should enjoy full political rights. Alluding to the already famous declaration of June that this was no mercenary army, he declared that if we had not a right to the kingdom, we were mere mercenary soldiers. He was echoing Rainborough, who had said he would fain know what the soldier hath fought for all this while. Rainborough went further than most of the Leveller leaders up to this point, by contending for unqualified manhood suffrage. The Levellers represented the interests of people of some modest economic independence, small traders and craftsmen, rather than those of the great mass of the poor. When some of the officers present, in dismay at the heat being generated by the long wrangle between Ireton and Rainborough, tried to steer discussion towards a compromise, such as denying the vote only to foreigners and to those too dependent to make a free choice, Petty responded positively; he was quite ready to consider excluding servants and apprentices who lived in their masters’ households, and men who subsisted by alms.

But just as the debate seemed set on a more constructive course, Rainborough tried to move that the army should be called to a rendezvous, and its line of action settled there. He doubtless had in mind the June rendezvous near Newmarket and the mass adoption of the Solemn Engagement, but whereas that event had served to unite the greater mass of the army, what he proposed would have further divided it. The record of the day’s debate breaks off before the end, but it seems that a straw poll was taken as to whether all but beggars and servants should have the vote, and (reportedly), only three were against. This did not, of course, amount to a general conversion to the Leveller programme as a whole, as if the vote had been on whether to march on London and impose the Agreement on parliament it would doubtless have gone very differently. To prepare for the next day, a new committee was established to seek compromises between the Heads of the Proposals and the Agreement. It comprised Cromwell, Ireton, both the Rainborough brothers, Chillenden, Sexby and Allen.

The Levellers, however, were rarely all of one mind, and Wildman was much less interested in compromise than in power, unlike John Lilburne, who was not ill-disposed towards the king. Wildman was already a republican by this time, and almost certainly wrote A Call to all the Soldiers of the Army by the People of England, which was in print and circulating among the regiments on 29 October, just as the great debate on the Agreement was happening. It denounced Cromwell and Ireton in virulent terms, accusing them of ‘leading the agitators by the nose’ in the General Council while they drove on the king’s design in parliament, and of claiming as they did so that they spoke for the whole army. It called upon the soldiery to withdraw their obedience from all officers who would not go with them along the path blazed by the Agreement, declaring …

… Ye have men amongst you as fit to govern as others to be removed: And with a word ye can create new officers. … truest lovers of the people ye can find to help you. … Establish a free parliament by expulsion of the usurpers.

This was an open incitement to mutiny, and it was not the only one in print and circulation. New agents were already appearing in other regiments beside the original five, and the men of Colonel Robert Lilburne’s regiment of foot, which Fairfax had ordered to Newcastle, was already defying their officers and holding unauthorised rendezvous.

On Sunday 31st, Colonel Rainborough took advantage of a break in proceedings in the debates to visit John Lilburne in the Tower. Rainborough professed great friendship towards the Leveller leader, though there is little evidence that he had met him previously. Nevertheless, he deplored the ‘foolish zeal’ which was driving some of the spokesmen at Putney to express evil intentions towards the king’s person, which he well knew the greatest part of the army abhorred to think of. Our information about this visit comes from The Tower of London Letter-Book of Sir Lewis Dyve. Earlier in the month Dyve had delivered Lilburne’s advice to the king that he should call a meeting with the Levellers in the army council and reassure them about his intentions. If he did so, Lilburne promised, he would have the army at his devotion within six weeks. But in that the Leveller leader was out of touch with the tide of ill-feeling towards the king that was rising in the army which made itself known in the special session of the General Council on Monday 1st. It probably owed something to Wildman’s influence over the new agents and his speeches at Putney, but it was also partly religious in origin. Lieutenant Colonel John Jubbes made a statement at the Putney debates on 1st November 1647, in which he called for political reforms extending well beyond the regiment’s grievances he had set down in a statement on 13th May. However, Jubbes’ position was a conciliatory one between the army independents and the Levellers, seeking even to bring ‘liberal presbyterians’ into an agreement.

Cromwell was presiding at Putney again as November began, and he began by inviting those present to speak of any divine prompting that they had received in answer to their prayers, and this was an unintended invitation to those, not just the Levellers, to express their beliefs that God had abandoned their cause because their leaders in parliament continued to sin against him by trafficking with the king. In particular, Captain Bishop gave powerful testimony that God’s answer to his prayers had been that they were all guilty of…

… compliance to preserve that man of blood, and those principles, which God from heaven by his many successes given hath manifestly declared against.

The King’s ‘Escape’ to Carisbrooke Castle:

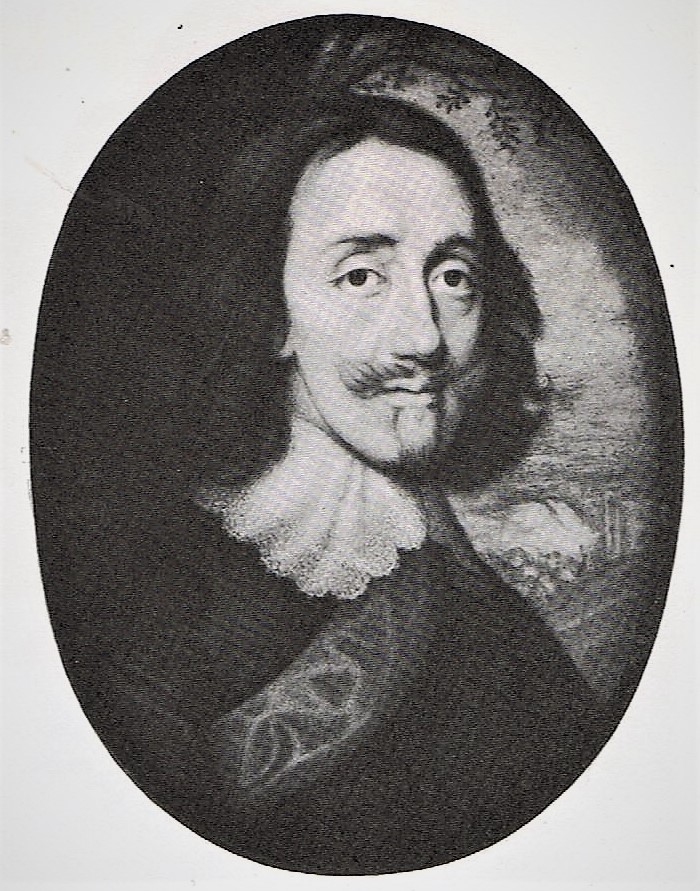

This scriptural image of Charles as a ‘man of blood’ was to gain even more potency with the outbreak of the second Civil War leading to a justification of his trial before parliament and subsequent execution. But, at this point, such responses were just the opposite of what Cromwell wanted to hear, and he let himself get drawn into a long altercation with Goffe in particular as to how far they could expect God to pronounce on detailed political matters. He also allowed a long and increasingly ill-tempered three-sided exchange of views to develop between Ireton, Wildman and Rainborough, who differed so much in their principles that there was little chance of reconciling these views. Yet the General Council agreed to go on meeting daily until the proposals in front of it had been fully considered. But these sittings only generated more division, and the commanders became increasingly concerned about this. Charles had also given them fresh cause to be concerned about his intentions since he had given his word that he would not try to ‘escape’ from Hampton Court and, in return, he had been free to see whomever he pleased. However, on 30 October he withdrew his ‘parole’, resulting in a doubling of his guards. But it was impossible to foil a determined escape plan from the palace without making him a close prisoner within it, and that was politically unacceptable while he was still formally king and accorded royal honours.

What was more worrying, however, was the growing restlessness in the army. Leveller propaganda was making convertsand the new agents were claiming to have the support of sixteen regiments, including seven of foot. But not all the discontent was of their making since four hundred of Colonel Robert Lilburne’s mutinous foot soldiers were reported early in November to have declared for the king, and his was not the only regiment in which royalist sympathies rose to the surface. Probably more typical was a rising resentment against the agitators in perfectly loyal regiments due to the divisions they were causing and, in some cases, their overbearing attitude towards the ordinary soldiery. Whether such tensions were aroused by the original agitators or the new agents is not clear, but men who were not in direct touch with the proceedings at Putney may not have made the distinction. Fairfax was reliably reported to have received a petition from the majority of regiments, asking him to send their agitators back to them until he felt a need to summon them again, and undertaking to submit to him and his council of war according to the old and accustomed discipline of the army.

Within the General Council the generals’ hold on proceedings remained somewhat precarious. On 5 November, when Fairfax was well enough to preside again, and Cromwell had gone to the Commons, Rainborough secured the assent of the meeting to send a damaging letter to the Speaker alleging that the House had been induced to make further propositions to the king because it was told that the army wished it. The General Council declared that any such representation of the army’s desires was absolutely groundless. This was as good as to accuse Cromwell and Ireton of misrepresenting the army’s views to the House, so Ireton opposed the letter vehemently. When it was approved, he stormed out of the meeting, vowing not to return until it was recalled. The Levellers also went on pushing for another general rendezvous, and on the 6th, they pressed hard for a free debate on whether the king should be allowed to retain any powers. At the General Council’s next meeting two days later they seemed bent on confrontation over the franchise, and there was another protracted clash, but Fairfax and Cromwell had already decided that the General Council was being made a platform for those who sought to divide the army and take control of it, so that the long debate on the Agreement must be wound up.

The ‘grandees’ may also have had intelligence that the king was about to ‘bolt’, for it was during this weekend that Charles finally made up his mind to leave Hampton Court. So when the talks seemed to have run their course, Cromwell moved that since Fairfax intended to call the army to a rendezvous shortly, and because many distempers are reported to to be in the several regiments, the General Council should advise him to send the officer-representatives and the the agitators back to their regiments until he should see cause to summon them again. There is no record of any dissent, and Fairfax reported to the Speaker that the regimental representatives had unanimously offered to return the regiments and do all they could to restore discipline in them. To underline his support for his soldiers’ real interests, he accompanied their letter with a request to the Commons for the immediate disbursement of six weeks’ pay. When the full General Council met next day, it approved a letter to the Speaker, explaining that its previous one on the 5th was not intended to mean that the army was opposed to parliament’s sending any more propositions to the king. The generals were in control again, and it was announced on the same day that the promised rendezvous of the army was to be spread over three separate dates and places between 15th and 18th November.

The Leveller agents publicly denounced this as a base device to prevent the army from adopting their Agreement by general acclamation, and this was doubtless a consideration. But there were more compelling reasons for appointing three rendezvous, not least that Fairfax wanted to address each regiment in person, which could not be done in the course of one day. Moreover the regiments were now dispersed over a wide area, and to suddenly concentrated them in one place close to London would have not only set the political alarm bells ringing but caused much hardship to civilians. The Leveller agents, however, urged them in print to gather in a single rendezvous in defiance of orders. Nevertheless, the Agreement had been amended to include a substantial extension of the franchise, as proposed, to all soldiers and all others except servants and beggars. But Cromwell and Ireton made a perfectly-timed counter-attack. The old agitators repudiated the new programme; the generals reasserted their authority. On 8 November the agitators were sent back to their regiments, and the Army Council was adjourned for over a fortnight. The pattern established in June had now been dramatically reversed. Then the rank and file had held the initiative: the agitators had seized the king and the commanding officers had had to accept the situation at the general rendezvous at Newmarket as the only means of preserving the unity of the army. Now the rank and file were already divided and had lost the initiative, when the shattering news came that King Charles had escaped from army captivity.

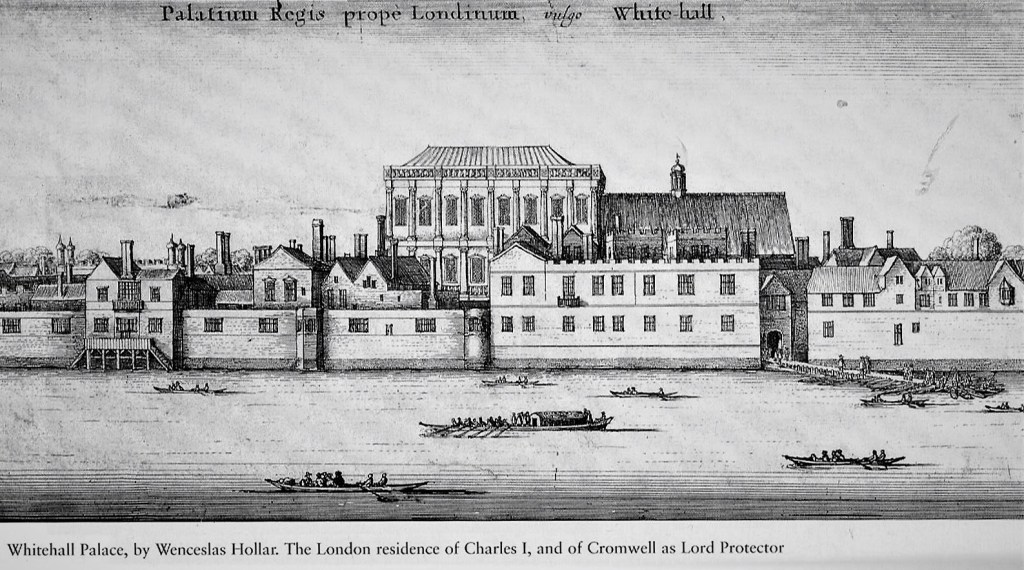

On 11 November 1647 Charles had indeed escaped the custody of the New Model Army at Hampton Court. He had finally decided upon flight more than a week earlier, and he probably fixed the date on the 7th, before he had anything to fear from the army. Yet on the 9th he told Sir John Berkeley that he was in fear for his life, for he had received a letter that day warning him that eight or nine agitators had met the previous night and resolved to kill him. The writer, who signed himself ‘E.R.’, was almost certainly Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Lilburne, brother and second-in-command to Colonel Robert, but of a very different temper from either him or even his other brother John. Henry was shortly to declare for the king. There is some evidence of a shadowy plot among some of the Leveller agents to abduct the king, though not to assassinate him. Cromwell himself heard rumours of an attempt on the king’s person, and wrote at once to his cousin Colonel Whalley, who commanded the guards at Hampton Court to take special measures against this, for it would be accounted a most horrid act. But while it suited Charles to declare publicly that he fled because he feared for his life, he left a letter for Whalley, assuring him that this was not the case. His main reason, which he kept to himself, was to be free to negotiate with the Scottish commissioners without the surveillance of the army or parliament. When he set out from Hampton Court, he had no idea where he would head for, and neither did Cromwell, who had not yet given up hope of coming to terms with him, for only the day before his escape the Commons had put the finishing touches to a new set of peace propositions, based on the initiative of Cromwell’s independent allies.

The King had told the Scottish commissioners on the 9th that he was ready to make for Berwick, but he evidently changed his mind, and his companions Ashburnham and Berkeley gave him conflicting advice. In the end, he decided to decided to place his trust in Colonel Robert Hammond, another of Cromwell’s cousins, who had become increasingly unhappy about the army’s increasingly political role over the second half of 1647, and with Fairfax’s concurrence he had given up his regimental command in favour of what he hoped would be a quieter life as governor of the Isle of Wight. Hammond was utterly dumbfounded, therefore, when Berkeley and Ashburnham arrived at Carisbrooke Castle, his headquarters, and delivered the king into his hands. He immediately sent word to Cromwell, and despite his conflict of loyalties, he set a guard on his uninvited guest to prevent either kidnap or escape. Two days after his arrival he sent a request to parliament for a personal negotiation in London, on the basis of a three-year trial period for Presbyterianism, liberty of worship thereafter for all papists, and parliamentary control of the armed forces during his lifetime but not under his successors. That might have been a basis for a settlement eighteen months earlier, but he was now far less credible as a negotiator than he had been then.

Rendezvous & ‘Remonstrance’:

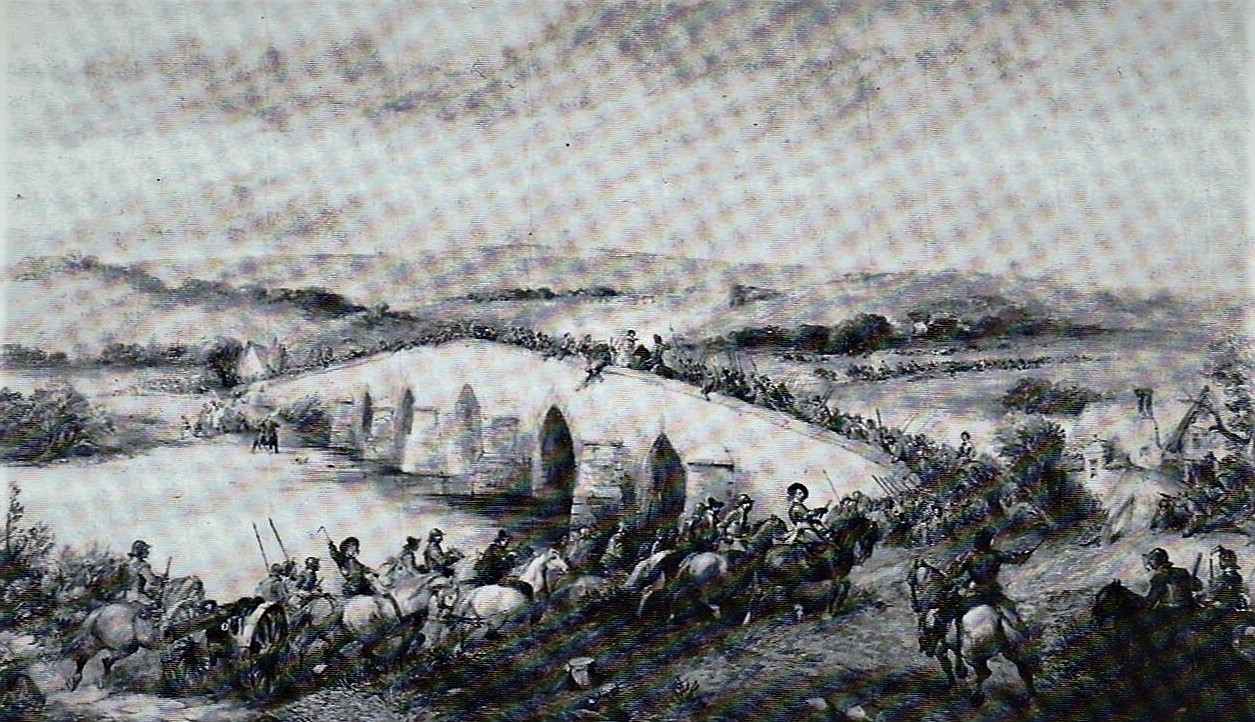

Meanwhile, on 15th, Fairfax held the first of the three scheduled rendezvous at Corkbush Field near Ware. He brought with him a new Remonstrance, issued in his name and that of his council of war, and prepared with the advice of a committee headed by Cromwell and Ireton but included several radical officers and agitators. It redefined the common objectives of the army, and it was hoped that by having it read to eat regiment, personally commended by Fairfax, and then subscribed by officers and men, unity and and discipline would be restored. But the Levellers had been busy preparing to use the occasion for their own purposes, and the generals must have feared that they would try to turn it into a general rendezvous and get the Agreement acclaimed instead of Fairfax’s Remonstrance. They soon found people distributing the former among the the troops and two former officers, Colonel William Eyre and Major Thomas Scott, haranguing them in support of it. The generals promptly had them arrested, but as soon as Fairfax appeared on the field he was confronted by a delegation headed by Rainborough, who presented him with the Agreement and a petition. Rainborough, no longer in the army, had no right to be there, and as a member of the House of Commons, he was also choosing openly to disregard its condemnation of the Agreement as destructive to the being of Parliaments, and to the fundamental government of the kingdom.

Seven regiments attended the first rendezvous at Corkbush Field near Ware by Fairfax’s commands; all greeted him with enthusiasm and readily subscribed his Remonstrance. Two others, Harrison’s and Lilburne’s, appeared on the field without orders and without their officers, except for Captain-Lieutenant Bray of Lilburne’s, the highest-ranked officer. He claimed that there was no visible authority in the Kingdom but the general … and the general was not infallible. Many of the men wore copies of the Agreement stuck in their hats, overwritten with the Leveller slogan, England’s freedom: soldiers’ rights! This was mutiny, but it swiftly collapsed. The defiant soldiers found themselves isolated, and they were met with uncompromising firmness. Officers of Fairfax’s staff rode in among them, snatching the papers and sea-green ribbons from their hats. Earlier in 1647 the Levellers had begun to mobilise mass petitions, often delivered by noisy crowds wearing the Leveller token of a sea-green ribbon in their hats. Cromwell was in no doubt at all that the Leveller agitations were undermining military discipline.

Robert Lilburne’s men, having marched twenty miles that day, arrived long after Harrison’s had been dealt with, and when a major tried to remonstrate with them they stoned and wounded him. Fairfax left them until he had reviewed the seven regiments present by his orders, but they must have heard the cheers that greeted his speeches throughout the day. Promises of arrears of pay were given, together with vague declarations about political reforms. Fairfax threatened to resign if these assurances were not accepted and if he did not receive a promise from each and every officer and soldier to obey his superiors in accordance with military discipline, and to abide by what the General Council determined with respect to public engagements. In return he pledged not only to fulfill all his duties as general, but also to further join with them in pressing for an early dissolution of parliament and the succession of future parliaments, elected by ‘equal representation’.

In the prevailing political circumstances nothing but surrender and submission was possible for the rebels. Encouraged by Bray and other agitators, there was a brief skirmish when Fairfax’s staff approached the two rebellious regiments, but when Cromwell and other officers drew their swords and charged at them, they soon fell into line and general discipline was swiftly asserted. Fairfax’s wisdom of holding separate rendezvous at which he could exploit his personal charisma to the full was now apparent after Ware. He had further successes at Ruislip Heath and Kingston in the following days, at which the regiments, two of which had been in a state of of incipient mutiny read the signs, toed the line and expressed a ready compliance and subjection. The Remonstrance was well calculated to restore the soldiers’ solidarity. It accused the new agents of acting, without any mandate from their regiments, as a ‘divided party’ from the General Council, under the direction of non-members of the army. This represented a resetting and a reafirmation of what the army had stood for in its pre-Agreement manifestoes of the previous June. All the regiments, including the lately mutinous ones, gave Fairfax the promises he demanded. This also marked a rejection, not of the basic principles of the Leveller movement, but of its recent tactics.

Considering how serious the threat of mutiny had been in the New Model at this point, its perpetrators were dealt with remarkably leniently, especially by the standards of early modern armies. On Corkbush Field, eight or nine ringleaders in Lilburne’s regiment were court-martialled on the spot and sentenced to death by firing squad, but Fairfax pardoned all but three, who were then allowed to draw lots for their lives. Only the one loser was shot, so that instead of the Agreement being read at the head of each regiment, Private Richard Arnold was shot at the head of his. The Levellers made made much of him as their first martyr. and when the eight others, including Bray, were taken into custody for future trial, the London Levellers campaigned and demonstrated vociferously for their release, leading to further arrests. In addition to those mentioned above, those arrested included William Everard, William Thompson, eleven in all. Their trials by court-martial were delayed, the last being held on 23 December, and when they proceeded, there was an unwillingness to judge harshly men who, however mistaken in their actions, had acted out of conviction. Only two were condemned to death, and both were reprieved. Both Colonel Rainborough and Major White made contrition before the General Council, the former eventually being allowed to resume his commission in the Navy, and the latter being retored to the Council. Even Bray was allowed to resume his regimental duties after making due submission.

So ended the Leveller attempt to capture control of the army, but not the movement’s wider role in the future of the kingdom. In retrospect, it is clear that the recall and replacement of the agitators of the five cavalry regiments, apparently done on John Lilburne’s advice, was going much faster than the majority of the rank and file were prepared to follow. They were principally concerned with wages and indemnity, and royalist sentiments were also widespread among them, even within regiments otherwise known for their radicalism. The declarations of the new agitators show them to be consistently on the defensive, for as Wildman himself wrote later: Did not many regiments at Ware cry out for the King and Sir Thomas? Consternation over the current wave of Leveller demonstrations and the anxiety about the king’s activities made parliament look more kindly on the army. Cromwell received the thanks of the Commons for restoring order on 19 November, though Fairfax was ordered to withdraw his headquarters to Windsor. The General Council met intermittently for the next six weeks, but it had lost its purpose, was dominated by the grandees and faded out at the beginning of the New Year.

Getting the pay the army needed took a little longer than the expressions of goodwill from parliament, but the City began to open its purse-strings when Colonel Hewson pointedly drew up his regiment in Hyde Park, and a firmly worded representation from Fairfax and the General Council, on 7 December, concerning the army’s financial and other material needs, got parliament moving towards meeting them. Under the threat of having troops billeted on citizens who were defaulting on their assessment payments, measures were taken to put an end to free quarter and enough money was found to pay off the men who had enlisted since 6 August. Most of those still in service were fully paid during the next six months; provision was made for maimed soldiers, widows and orphans, and apprentices were assured that their time in the army would count as part of their term of service. Parliament was not under the same pressure to attend the king’s latest overtures, for it was plain to the clear-sighted that if he had been seriously intent on negotiating he would have stayed at Hampton Court to hear parliament’s new proposals. The Independent-dominated House of Lords responded first, and they wanted some binding pledges from him before parliament wouéd treat further. They therefore framed four propositions, for the Commons to convert into bills, intending that he should first give them statutory force by his assent before being brought to London for a personal treaty.

The Four Bills & Presbyterian Parleys with the King:

The first of these propositions gave parliament full control over all land and sea forces for the next twenty years, and made the king’s disposal of them thereafter subject to parliamentary consent. The second annulled all oaths, declarations, proclamations, and judicial proceedings against parliament and its members and supporters since the start of the war. The third cancelled all peerages granted since May 1642, and ruled that no peers made from that time on should sit in parliament without the consent of both Houses. The fourth empowered the present parliament to adjourn to any place in England that it chose, for as long as it saw fit. Annexed to the Four Bills, as they came to be called, were a set of propositions, intended as parliament’s further terms for a treaty, which included the abolition of episcopacy, the banning of the Book of Common Prayer, and the penalisation of the king’s supporters in the war on the lines of the Propositions of Newcastle. The Commons approved the Lord’s proposals by a mere nine votes, but then stalled on converting them into bills. The Independents, who were still prepared to restore the king on strict conditions, were almost balanced by a combination of Presbyterians who would have him back on easier terms and the ‘commonwealthmen’ who did not want him back on any terms. Charles sent Berkeley to Windsor to ask the army to intervene on his behalf, but his envoy was given a cool reception. Fairfax told him that they were the parliament’s army, and would have to refer his proposals there. The Four Bills, when eventually enacted, were presented to Charles on Christmas Eve, and he was given four days in which to reply.

Somewhat ironically, being shut up in Carisbrooke Castle provided Charles with a kind of political liberty, since he was still allowed to entertain offers for his endorsement from the lowest bidders. They included the Scots, not the zealous Covenanters, but a critical element of the Scottish nobles who feared that the formidable New Model Army which had neutered the English Parliament would target them next, and thereby subject Scotland to a bedlam of sects which was already being unloosed, in their eyes, in England. The Scots also knew that, in his troubles, Charles was already becoming more popular than ever been during the eleven years of personal rule and the first Civil War. Lauderdale, Loudoun and Lanark arrived at Carisbrooke soon after the votes in the Commons, somewhat suspicious of Charles because he had not gone to Berwick, as promised. But they were anxious that he should not make peace with the English Parliament in which Scotland had no say. So they came to the Isle of Wight and made him the best offer he had yet received: In return for a trial period of three years of Presbyterianism in England and his voluntary acceptance of the Covenant, the Scots agreed to help Charles regain control of his kingdoms. He certainly wrung easier terms from them by pretending that he was about to assent to the Four Bills.

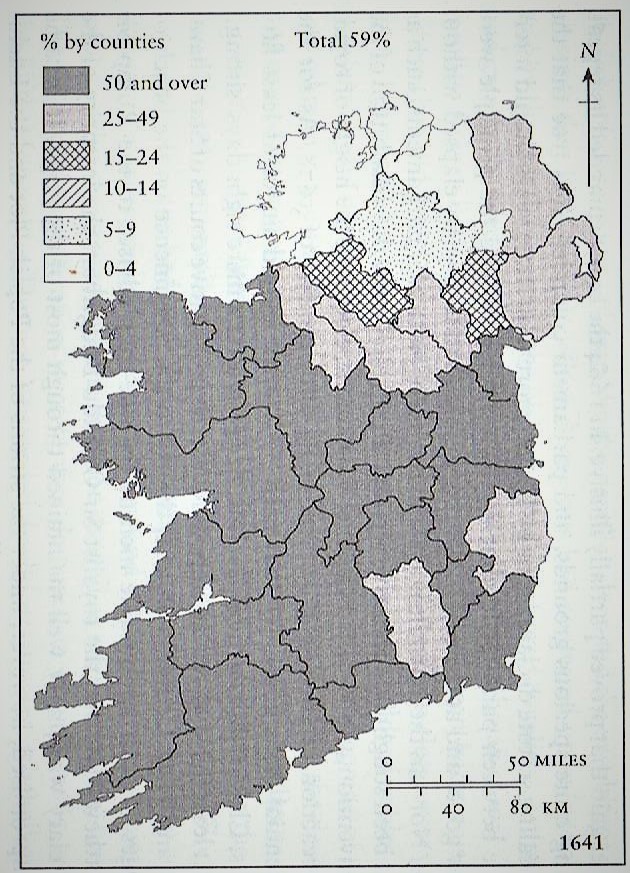

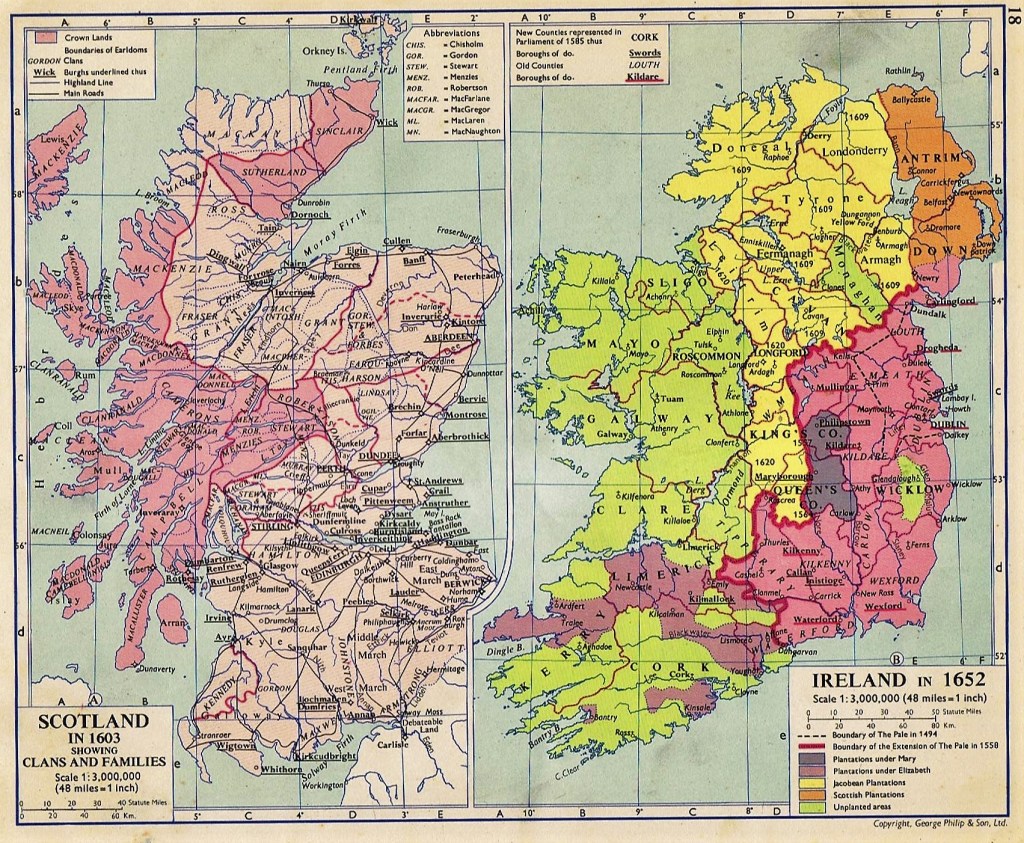

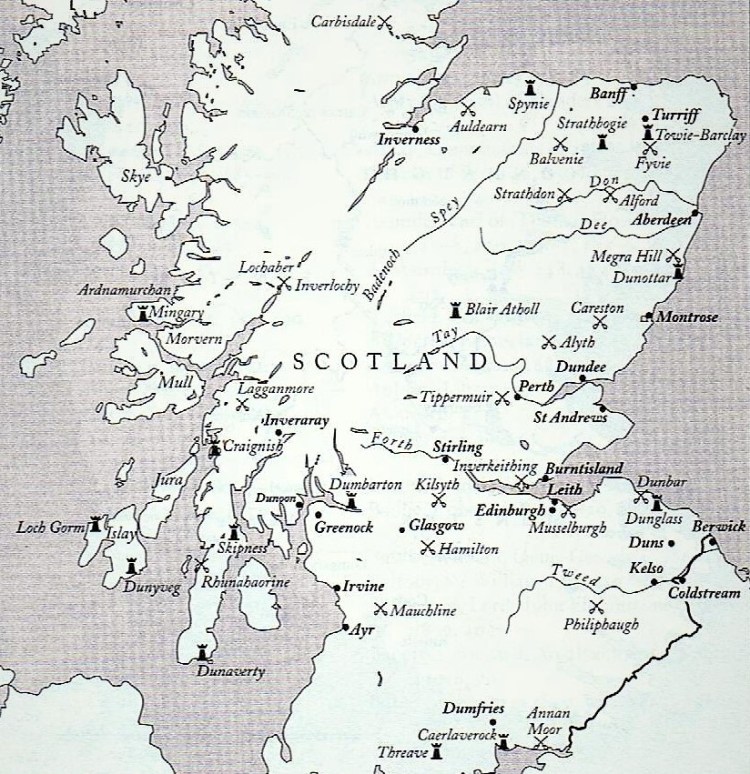

The political front with and in Scotland had been relatively quiet throughout most of 1647, when much of the country had been in the grip of a prolonged and deadly visitation of the plague. But the last of the Irish and the MacDonalds who had fought with Montrose had been savagely crushed, and there was no further resistance from the royalist party under Huntly. No enemies of the Covenant remained undrer arms, therefore, so the political arena was dominated by the rival Covenanting factions headed by Argyll and Hamilton. Both wanted to see the king restored in all his kingdoms, but until the summer Argyll’s and the Kirk’s party had successfully maintained that he must take and impose the Covenant. From August onwards, however, the prospect that the king might come to terms with an independent-dominated English parliament backed by the hated New Model Army swung the balance towards Hamilton’s party, and so still more did the personal danger which Charles was perceived to be in from the dissenters in the army. For the Scots, he was their king as much as he was England’s, and the view prevailed that that it was better he should owe his restoration to Scotland, even if his commitment to Presbyterianism fell far short of what the Scots’ leaders wanted than that he should regain his thrones on the ungodly basis of religious liberty, or to be prevented from regaining them at all. That, at least, was how Lauderdale and Lanark felt, though Loudon was full of misgivings.

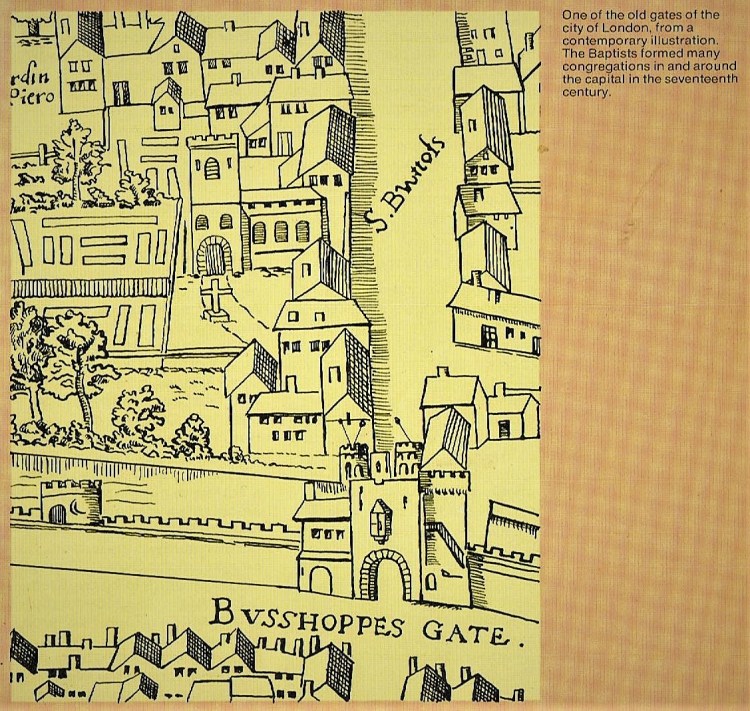

In the end, all three signed a secret agreement with Charles, known as the ‘Engagement’, on 26th December, under which (also seen as a means to end the civil war in Scotland), the Scots’ army, together with a newly-raised royalist army from the North of England, would, if necessary, impose the settlement by force. Despite the distrust he inspired, the three Scots’ visits were not controlled by their leaders at home. Charles was still their king, and Scotland was still England’s ally as long as he was also its king. At this point, there was no real indication that this was about to change. Charles did not give much away in the Engagement, however, and although he agreed to confirm the ‘Solemn League and Covenant’ by act of parliament in both kingdoms, he only agreed to confirm a Presbyterian establishment in the Church of England for an experimental three years. After that, there would be a debate among the ‘divines’ of the Westminster Assembly, reinforced by twenty additional members named by himself and any others sent by the Kirk. In the light of these deliberations, the permanent form of government of the Church of England would then be settled by King and Parliament. He also promised his assent to acts of parliament for the suppression of all Independents, Baptists and seperatists of every kind, and for the punishment of blasphemy, heresy and schism.

Charles condemned the actions of Fairfax’s army since its refusal to disband, and all the propositions that had been sent to him thereafter without the Scots’ consent. He promised to endeavour a complete union of the kingdoms, and in return the Scots promised to secure a personal treaty in London, upon propositions mutually agreed between England and Scotland. If this was refused by the English parliament, Scotland would declare his right to control the armed forces and the Great Seal, and to bestow offices and honours and to veto acts of parliament; and ultimately, in order to restore him to his just rights would send an army into England. But the Scots had no chance of raising an army that could engage that of Fairfax and Cromwell with any hope of success; they would have to count on powerful risings in their support, but they were hardly likely to win the hearts and minds of ‘freeborn’ Englishmen by dictating in advance the solutions to such problems as the control of the armed forces, the appointment of ministers and the royal veto, and by closing the door to liberty of conscience. As for Charles, his calling in of a Scottish army before he had explored fully the possibility of negotiating a peaceful restoration with the English parliament and army, was the most disastrous decision of his life. If he had been in Berwick, with a reasonable chance of escaping abroad if his champions were defeated, the gamble would have been less reckless, though he would still have lost his temporary popularity by plunging the two kingdoms into bloodshed again.

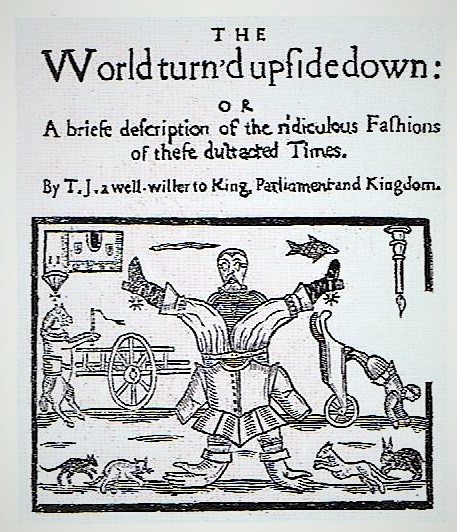

Over Christmas there were riotous demonstrations for king and church, for the old Anglican religion, almost amounting to insurrections, in Canterbury, Ipswich, and other towns, while in London Christmas decorations appeared defiantly in churches and other public places. Ejected clergymen resumed their pulpits and used the Prayer Book services, and royalist newspapers and pamphlets appeared freely on the bookstalls. But these were mostly symptoms of a widespread nostalgia for the old days of peace rather than of any general willingness to go to war again, and Charles failed to exploit this discontent by not displaying a more straightforward disposition towards a peace settlement. Next Charles attempted to escape by sea from his island ‘open prison’ but the wind was aginst him. As a result, his guards were redoubled and Vice-Admiral Rainborough, taking up his Naval commission on 1st January, was posted to guard the Solent. Charles lost the company of his friends Berkeley, Ashburton and Legge. In the Commons there was a move to impeach him on 3rd January, and to settle the kingdom without him. For most MPs that was a step too far, but it did pass a ‘Vote of No Address’, declaring that it would send no more overtures to the king and would receive none from the king. Anyone else caught attempting to treat with him would be charged with high treason. But in passing this, the ‘party of royal independents’ was seriously split, as was its alliance with the army high command, which had produced the most statesmanlike proposals for a lasting peace settlement.

The Outbreak of the Second Civil War:

The threat of the King once more in arms reunited the factious elements in the Parliamentarian camp and the New Model returned to duty. The hard-won peace was lost and the stage was now set for the second Civil War, but once again there were serious disagreements ongoing within the two Houses as to what parliament’s war aims would now be, and still wider differences between them and the army. With the Scots’ intentions uncertain, and the Irish rebels still undefeated, the army needed to close ranks. Moreover, the Levellers articulated only one strain of radical idealism in the English Revolution of the 1640s, whether in London, the counties or the army. Independent and sectarian congregations were growing rapidly in all three, and it was widely believed among them that the victory God had granted to his ‘saints’ in the recent war heralded the prophesied overthrow of the Antichrist, and that to seek its ‘fruits’ in the secular ideas of the Agreement was at the best to be distracted from Divine Truth and at the worst to succumb to blasphemy. To such believers, Leveller democracy was a dubious basis for a holy commonwealth. Just after Fairfax finished reviewing the army in November, the gathered churches of London had published a declaration which bore the names of some of the best known Independent and Baptist ministers, including Rainborough’s own pastor. A key passage in it alluded to the Levellers’ policies and their propogation in the army:

Since there is also much darkness remaining in the minds of men, as to make them call evil good, and good evil; and so much pride in their hearts as to make their own wills a law, not unto themselves only but unto others also; it cannot but be very prejudicial to to human society, and the promotion of the good of commonwealths, cities, armies or families, to admit of a party, or all to be equal in power. … the ranging of men into several and subordinate ranks and degrees is a thing necessary for the common good of men.

This may also have been the position of Hewson’s regimental chaplain, Henry Pinnell, who in December 1647 defended the Agitators to Cromwell’s face and in 1648 wrote A Word of Prophecy concerning The Parliament, Generall and the Army. Under Hewson’s command, the formally radical regiment remained loyal to the senior commanders, while others supported the Levellers. Unpopular though the military presence was due to its cost, neither parliament nor the army could be justly accused of keeping up larger forces than the circumstances warranted. During the early months of 1648 no fewer than twenty thousand soldiers had been disbanded with two months’ pay. The axe fell mainly on the provincial forces, especially those in Wales and the borders, many of whose officers had had been in sympathy with the attempted presbyterian counter-revolution of the previous summer. It looked as though they might join in a general mutiny against their disbandment, but firm measures by Fairfax stifled it. There were further mutinies in February, led by former agitators, but they were easily dealt with. On 22nd February 1648, following a soldier petition to Fairfax, Hewson expressed a view about the Levellers which was typical of the ‘grandees’:

We have had tryal enough of the Civil Courts; we can hang twenty before they will hang one.

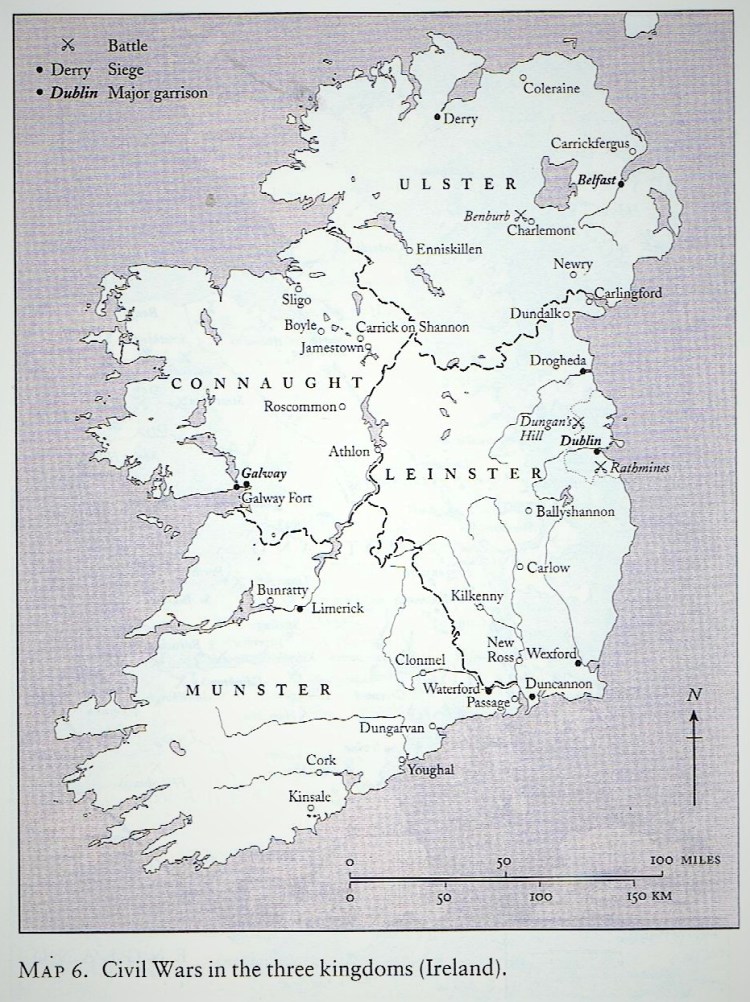

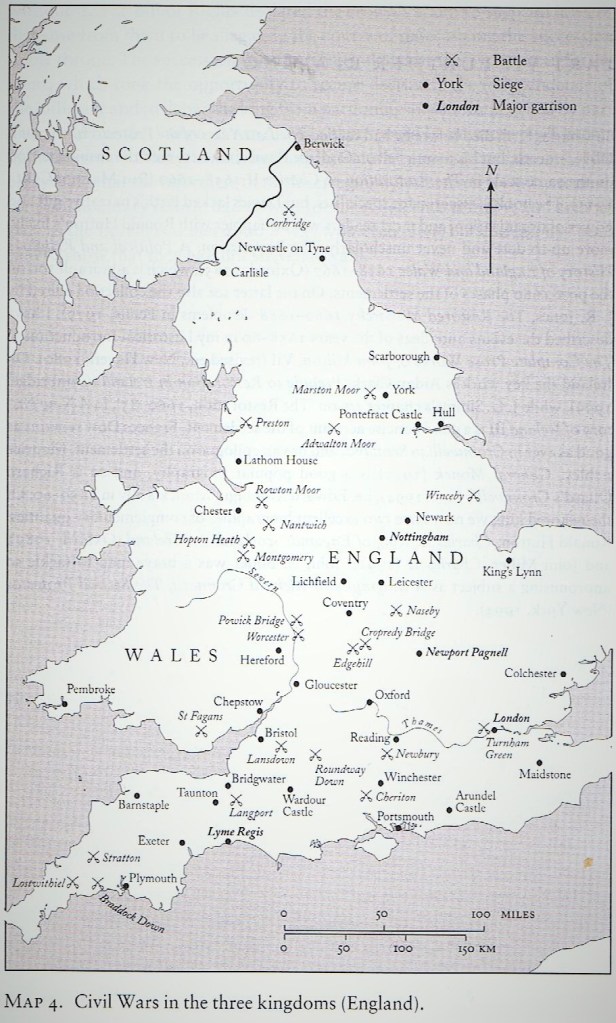

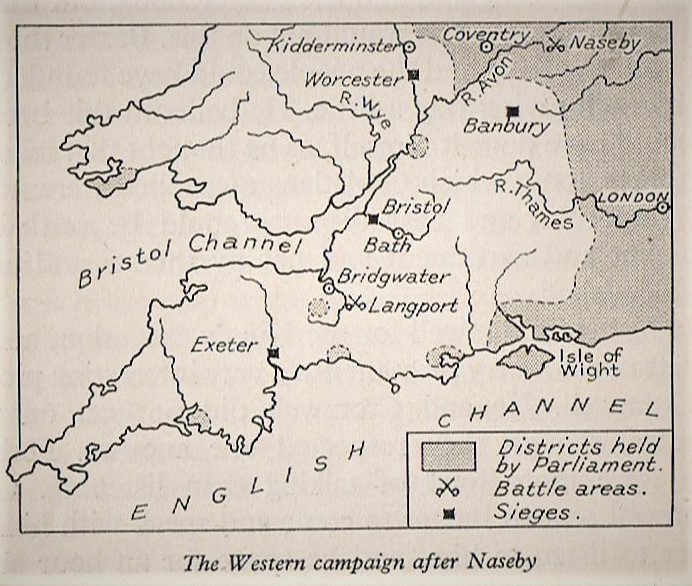

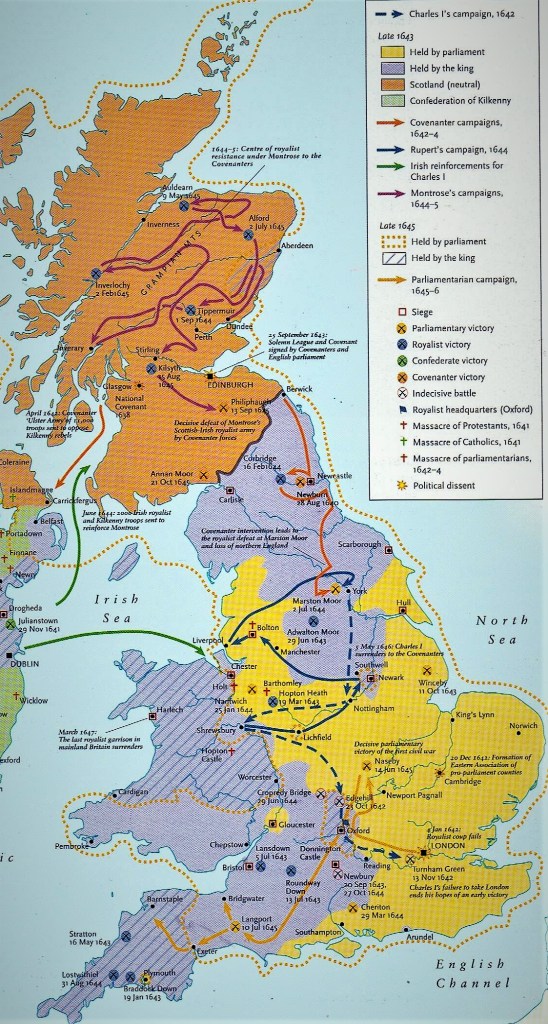

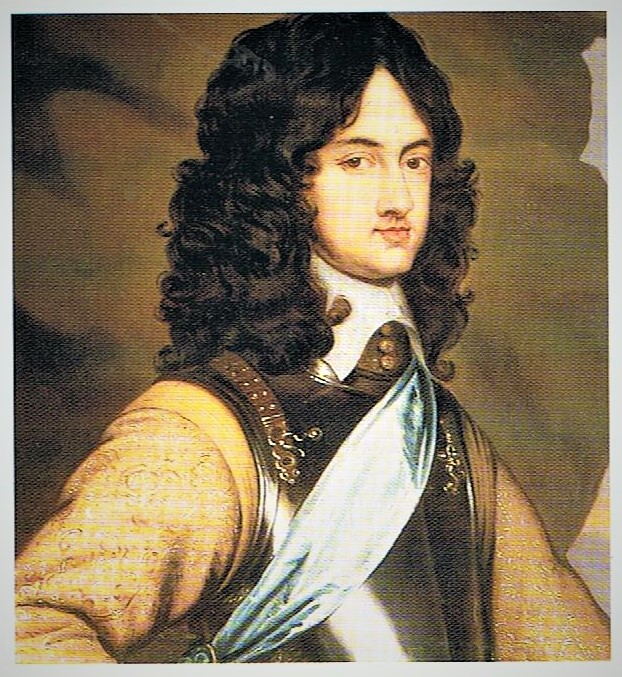

The war itself was an incoherent affair. Charles and the Scots had hoped that his English and Welsh supporters would rise in arms simultaneously with a Scottish incursion, for they knew that their only real chance against the New Model ‘veterans’ lay in diverting and dividing it by co-ordinated insurrections in several parts of southern Britain. But the king was still a captive on the Isle of Wight, and had no real means of marshalling his followers nationwide. The Scots did not have an army in the field until July, long after the series of separate royalist risings in southern England and Wales had already been defeated. The garrisons of most defended towns and castles in England and Wales were discharged, and Colonel Lambert (pictured below) was now in charge of the remaining forces in northern England, following the disbandment of the Northern Association. The New Model itself was slimmed down to about twenty-four thousand men, losing nearly four thousand, less than parliament itself had recently legislated for. Divisions among the king’s erstwhile supporters in the Celtic kingdoms held up the construction of a significant force for his cause in the north.

In April 1648, having lost the debate within the regiment, as the Levellers had within the army as a whole, and as the Second Civil War approached, Major Jubbes laid down his sword and took up the pen. He was disillusioned with the course the revolution was taking, believing that Cromwell was diverting the cause of liberation, but he seems to have been equally saddened by Leveller support for mutinies in the army and violent revolution involving military dictatorship. The war had encouraged Major Jubbes’ pacifist views, and he came to see a real conflict between, in his words, the slavery of the sword and a Christian peace. Opposed to the war in Ireland and saddened by the suppression of the Levellers, Jubbes pressed for political change from outside the army. He became associated with a group of London radicals who were more moderate than the Levellers. His social radicalism was linked to millennarian ideas which he shared with the Fifth Monarchists. The first two political documents of the millennarian cause originated in Norwich, Jubbes’ home town, and addressed issues on which he had expressed his views within the army. Jubbes was replaced as Lieutenant Colonel by Daniel Axtell, with John Carter becoming Major.

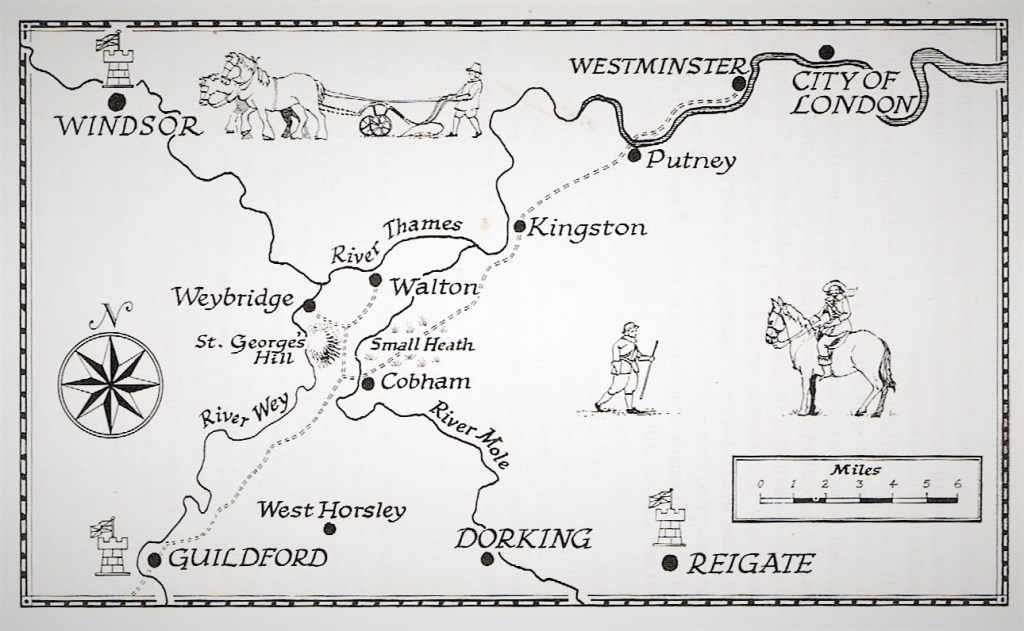

During April and May 1648, the military situation facing Parliament gave considerable cause for concern. Revolts on behalf of the King had occurred in South Wales, Kent and Essex, and there had also been a mutiny in the Navy. From Essex, two thousand men had marched on Westminster on 4 May with a petition bearing ten times their number in names, calling for the king to be treated with and the army to be disbanded. In Kent, the spark which lit the powder keg was the sitting of a special commission at Canterbury on 10th and 11th May to try the Christmas rioters. More seriously, on the 16th, three thousand armed men from Surrey brought another petition to Westminster Hall. Fairfax still had two regiments in the capital to guard the parliament, and they were called in. The result was a violent encounter in which half a dozen petitioners were killed and many more were wounded. Fairfax was able to deal with these threats in turn and he was supported by a strong framework of Parliamentarian garrisons in north Wales, the north of England and the Midlands. Kent, Surrey and Essex were still in an explosive condition as Cromwell headed for south Wales.

Whilst Fairfax had had to delay his march northwards against the expected Scottish invasion in order to successfully drive the rebels back into their homes, the bolder spirits among them held a large gathering at Rochester on the 22nd, supported by many of the local gentry. They appointed a general rendezvous at Blackheath on the 30th, hoping to be joined there by equal numbers from Essex. They were encouraged when many of the warships around the eastern coasts declared for the king, many of the Kentish sailors also being disgusted by Rainborough’s appointment as Vice-Admiral. The crew of his flagship mutinied while he was ashore, preventing him and his family from coming aboard. Nine ships were defying parliament within days of the outbreak of the rebellion, and they were soon joined by others, enabling the Kentishmen to secure all the maritime castles with the exception of Dover. The insurgents lacked as yet an authorised military leader, and since the king was a captive it fell to the exiled court of the queen and the Prince of Wales to commission one. Their choice as commander of all the king’s forces in England was the Earl of Holland, a courtier who had changed sides twice but was still a favourite of Henrietta Maria. He appointed the veteran Earl of Norwich, Goring’s father, to command the Kentish forces. He was hardly the ideal man to reconcile the divergent aspirations of the seasoned cavaliers and of the majority who had risen primarily to reassert the rights and interests of their county community, but his leadership was accepted and he exercised it vigorously.

By the end of May, Norwich had about eleven thousand men under arms, and there was a great fear in London of a concerted atack from both north and south of the Thames. But Norwich’s troops were widely scattered, and Fairfax frustrated their planned rendezvous by occupying Blackheath himself. From there, he advanced with about four thousand men against Maidstone, where Norwich found himself dangerously outnumbered. While Cromwell supervised the campaign in Wales, Fairfax fought his way into Maidstone on 31st May in a tough fight before he dislodged the royalists, and then crossed to Essex to besiege Colchester, leaving Hewson’s regiment to ‘mop up’ the rest of Kent. Norwich tried to maintain his advance to Blackheath, but finding his road to London blocked, he ferried his remaining three thousand men across the Thames into Essex and set about raising that county. Colonel Hewson himself was commended for his valour and resolution when the regiment bore the brunt of the fighting at the storming of Maidstone. Fairfax wrote of the valour and resolution of Col. Hewson, whose Regiment had the hardest task, Major Carter being injured and Captain Price slain. Hewson and Axtell were voted a hundred and a hundred and fifty pounds respectively by parliament in recognition of this service. With Rich’s regiment, they suppressed the rising in Kent and recaptured the castles of Deal, Walmer and Sandown. But Rich’s regiment had reappointed its agitators, who petitioned for the Agreement once more: they were forcibly dispersed by their officers. By judicious manoeuvring the generals retained control before the Second Civil War broke out in earnest.

As the Engagement became better publicised during the Spring, hundreds of English royalists and reformadoes arrived in Scotland to offer their services. With their help, Berwick and Carlisle were occupied for the king on 28-29 April by Sir Marmaduke Langdale and Sir Philip Musgrave respectively. But it was not until 4 May, when the war had already begun in Wales, that the Scottish Parliament ordered the raising of an army of 27,750 foot and 2,760 horse. The Covenanting army was to be absorbed into it, but its commander David Leslie refused to serve for an uncovenanted king. Hamilton was then named as general. Meanwhile, Fairfax sent Colonel Horton with a small mixed force to Wales, to ensure that Laugharne’s troops disbanded according to orders, but Horton found most of them defiant; many wore papers in their hats reading ‘We long to see our king’. He engaged them at St Fagans near Llandaff on 8 May, the first clash of arms of the second war, beating them soundly; but it took larger forces to retake Pembroke Castle and subdue south Wales. Cromwell was already on the way to join him with three regiments of foot and two of horse. By this time there were clear signs that the Scots were raising an amy, and the northern royalists’ seizure of Berwick and Carlisle confirmed that an invasion was not far away. English counties petitioned parliament to readmit the king to a personal treaty, and although this was unrealistic, given the king’s obvious determination to regain what he had lost by force, the Commons did vote by 165 to 99 that they would not alter the fundamental government of the kingdom, by King, Lords and Commons, though they were already thinking of replacing Charles with his youngest son, the Duke of Gloucester. ‘That man of blood’, as Charles had first been named at Putney, had, in many eyes, foreited his right to rule by renewing warfare against his people, but they had not yet concluded that the monarchy should be abolished.

We also need to be wary of believing that the grandees and officers embarked on the second Civil War with the aim of putting the king on trial for his life. We do not know when Cromwell made up his mind that Charles was no longer fit to be king, but it was almost certainly not in the Spring of 1648. The republican soldier and MP, Edmund Ludlow, wrote an account of a conference that Cromwell held at his London residence between those called the grandees of the the House and Army, just before his Welsh campaign, in which Cromwell and his fellow-officers…

… kept themselves in the clouds, and would not declare their judgements either for a monarchical, aristocratical or democratical government; maintaining that any of them might be good in themselves, or for us, according as providence should direct us.

It would have been unlike Cromwell to presume to judge the intentions of providence until after the outcome of the war that lay ahead. One continuing difference was as to whether it was the army’s business to promote a just secular settlement of the kingdom and leave the matters of religion to the individual conscience, or whether its primary mission was to advance the interests of the people of God. The Levellers were among those who sought to prescribe a political role for it, and though Fairfax’s triumph at the three rendezvous in November had checked their influence, it had not erased it, as the events of Spring 1648 had revealed.

Theatres of War – Essex, Wales, Lancashire & Scotland:

Essex was the main theatre of war in June, but rebellion was threatened from so many quarters from mid-May that the generals’ forces were fully stretched, and it was well for parliament that, by the beginning of June, their loyalty was unassailable. In Bury St Edmunds there was a riot when some revellers tried to set up a maypole, after which some six hundred armed men took ver the town on 13th, shouting ‘For God and King Charles’. The trained bands dispersed them next day, but Colonel Whalley was sent in the next day to keep East Anglia quiet. Royalist meetings at nearby Rushbrooke Hall and Newmarket continued to arose anxiety, and there was another scare over a royalist plot to seize King’s Lynn. In June, there were reports of widespread disaffection in the Fens, the old parliamentarian heartlands, where the gentry had been dismayed by the rapid rise of radical independency, leading to them feeling equivocal if not outright hostile towards parliament. Royalism of an older kind was raising its head in Devon and Cornwall; Fairfax had sent Hardress Waller there, and he had to suppress rebellions there during June. The king’s supporters in Herefordshire were preparing to rise in support of the expected Scottish invasion, and some northern royalists under Langdale’s oders seized Pontefract Castle on 1st June. Cromwell sent some small detachments to to deal with disaffection in Shropshire, Cheshire and north Wales. However, lacking siege guns, Pembroke Castle held out against him until 11 July.

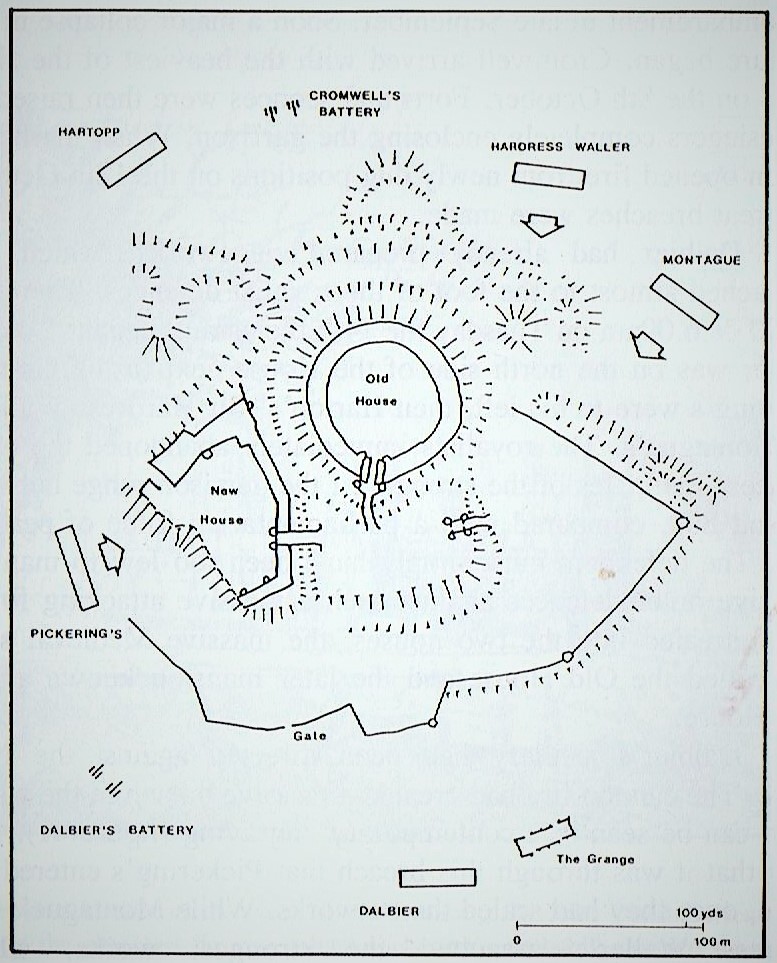

So when Fairfax set about reducing the County of Essex in June he had units of his army operating in six widely separated parts of England and Wales, and there was a serious danger of the conflagration spreading across East Anglia if he did not deal with it swiftly. The Essex rising got under way when some of the county militia were joined by Sir Charles Lucas commanding the royal forces in the county and Norwich, at Chelmsford with the Kentishmen. Together, they made for Colchester, the county town, where they set about organising its defences. Fairfax arrived before it on 12th June and summoned it to surrender the next day. When the defenders refused, he tried to storm it; but they withstood his assault through a fierce fight that lasted until midnight, with considerable losses on both sides. Fairfax’s troops were not overwhelming, so he faced a long siege; he had about nine thousand against four thousand defenders, but his troops also included local troops from Essex and Suffolk. The siege was conducted in unusual hardship and with harshness and mutual bitterness unlike any of the sieges in the first civil war. The experience of it on the parliamentarian side heightened the feeling that the king had wilfully renewed the bloodshed in the teeth of God’s judgement.

Colchester was only fifty miles from London, and while Skippon could be counted on to hold the trained bands firm, the City government was downright unfriendly, the Lords were equivocal and the Commons were wavering. Early in June the the latter revoked their votes expelling the eleven impeached members, some of whom resumed their seats. The Tower and its garrison were back under presbyterian command, and on 19 June a train of wagons carrying munitions for the army through London was attacked and overturned by gangs of apprentices. Holland and the Duke of Buckingham were mustering the royalists of Surrey close to the capital, as part of an ambitious plan in which the warships which had gone over to the king were to sail up the Thames with the Prince of Wales and troops and munitions from France on board. But they were put to rout at Kingston on 5 July by a mixed force of Kentish levies and regulars, Buckingham’s son being killed and Holland taken prisoner. Holland was held captive at Warwick Castle, pending trial, but the Lords ordered, through their Speaker, Manchester, that he be handed over to their custody. Fairfax refused this command, which so incensed the peers that they actually entertained a motion to revoke his commission, though they did not pass it. In the span of the next week, three key events in the war occured in quick succession: the Scottish army crossed into England, the leaders of the insurrection in south Wales and the remaining royalists of the south-east were bottled up in Colchester.

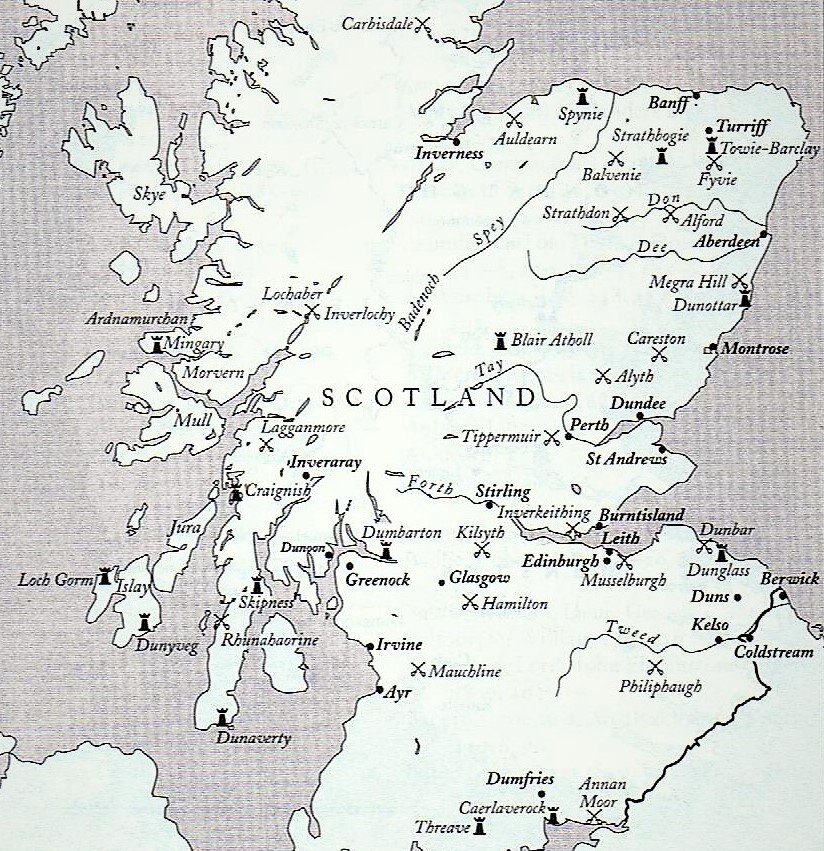

On 8 July a Scottish army of six thousand infantry and three thousand cavalry, under the command of the Duke of Hamilton, crossed the border. Three days later Cromwell was able to switch his army from Wales to the north to support the 3,500 under John Lambert who had been charged with delaying the Scottish advance. This was a timely move, for although Lambert had been joined by 2,700 Lancashire troops under Ralph Assheton. Hamilton had also been joined by seven thousand more Scots and 3,500 men under Sir Marmaduke Langdale. Lambert evacuated Penrith on 14 July, falling back into Yorkshire in the expectation that the Scots would advance down the eastern side of the Pennine Hill chain. Hamilton, however, chose to advance down its western side through Cumbria and Lancashire, and Lambert lost touch with the enemy. Cromwell finally met up with him at Wetherby on 12 August before marching on to Preston, in the hope of cutting across the Scottish line of advance or of taking it in flank. Due to the heavy rain and the daily need to forage for supplies, Hamilton’s column of march became over-extended as the Scots pushed southwards. When Cromwell’s troops made contact with Langdale’s rearguard on 16 August, the Scottish infantry had barely reached Preston, while their horse were sixteen miles (26k) further south at Wigan, and their artillery was still far to the north.

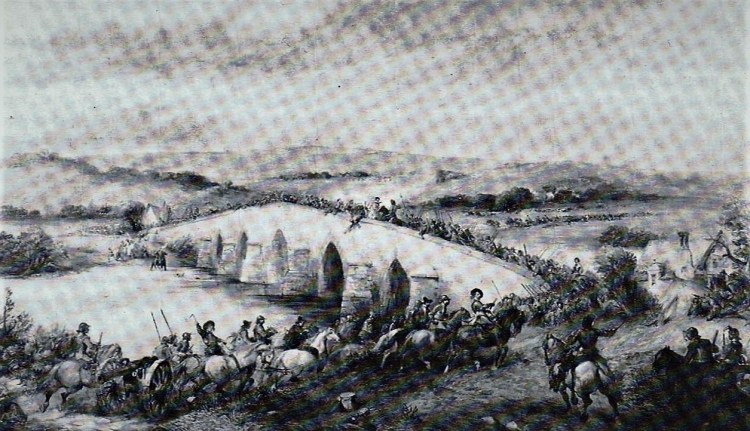

Langdale warned Hamilton of the danger threatening the army’s eastern flank, but the Duke dismissed the Parliamentarian presence as a mere reconnaissance in force. On 17 August, Langdale’s Regiments stood to arms at dawn and fell back to within two miles of Preston. Sir Marmaduke posted his musketeers and pikemen in the enclosures on the west of Ribbleton Moor where the hedges and soft boggy ground made it difficult for the opposition to manoeuvre. It was not until 4 pm that the Parliamentarian regiments were finally deployed. When attacked the Royalists stood their ground well, and a fierce struggle ensued from hedge to hedge. As Langdale’s troops were gradually pushed clear of the enclosures, Cromwell’s Horse cut into the flanks and the withdrawal developed into a rout. While Langdale’s men fell or were captured, the Scottish foot continued southwards over Preston bridge, putting the Ribble between themselves and the persuing parliamentarians. Once Cromwell had cleared Preston of royalists his men stormed the bridge, driving in the defending Scottish brigades. The next bridge to fall was that crossing the Darwen, but by then it was entirely dark and fighting petered out.

Hamilton’s army had escaped, though five thousand royalists had been killed or captured in the process. During the night the Scottish infantry attempted to link up with their cavalry which was now returning to Preston, but as the two bodies were moving towards each other on different roads, the first troops encountered by the cavaliers were Cromwell’s. After a running fight along the Standish road, the Scottish cavalry were at last reunited with their infantry on Wigan Moor. With his army disintegrating around him, Hamilton rode off with the horse leaving the foot to surrender at Warrington. The news of their victory hastened the surrender of Colchester, whose defenders were already preparing themselves for the inevitable. Fairfax had not tried to storm the town, though its decaying walls offered no such challenge as Bristol’s fortifications had done. Only three of his regiments were from the New Model; the others were recently recruited in Essex and Suffolk. He neither wanted nor needed to incur further casualties. Once all the other royalist movements south of the Trent had been suppressed, the Colchester garrison was isolated, and it posed no threat unless a Scottish army came to its relief. Fairfax’s persistence with the siege shows that he had strong confidence in Cromwell’s capacity to deal with Hamilton.

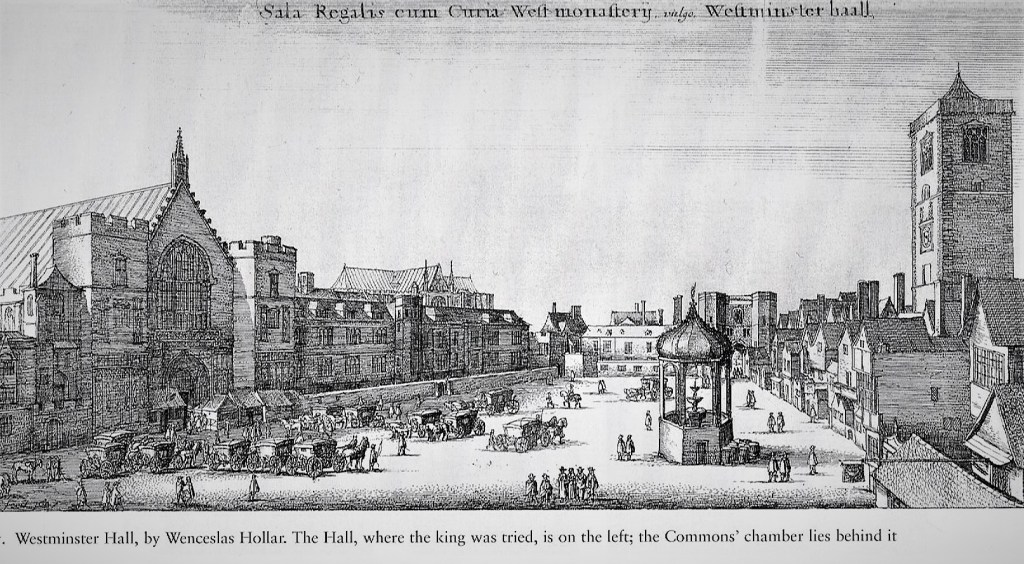

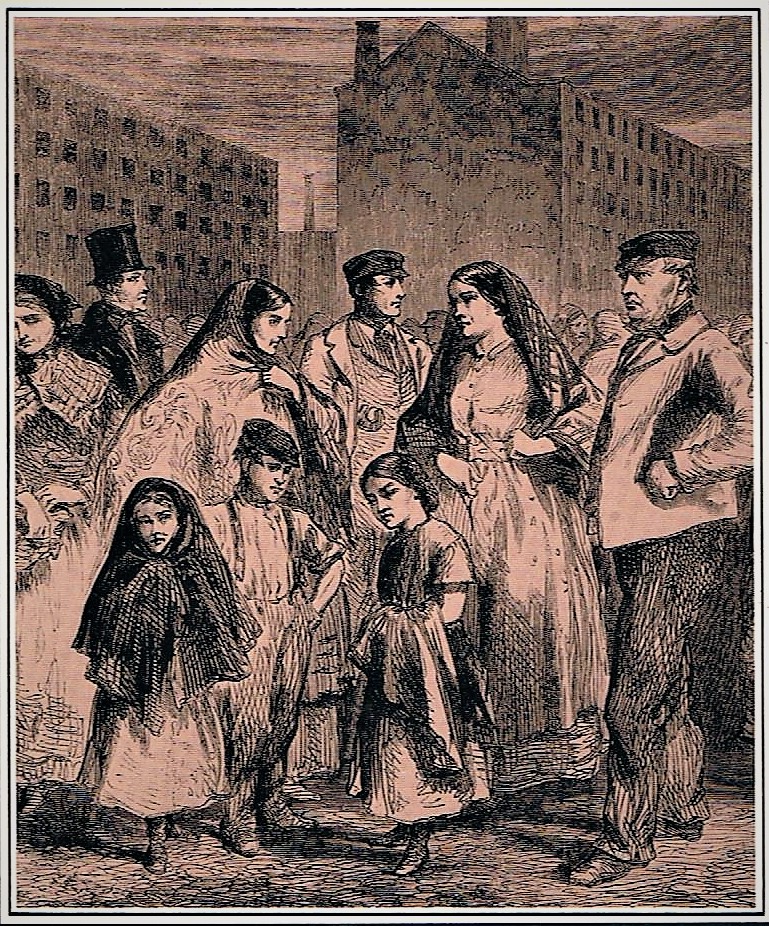

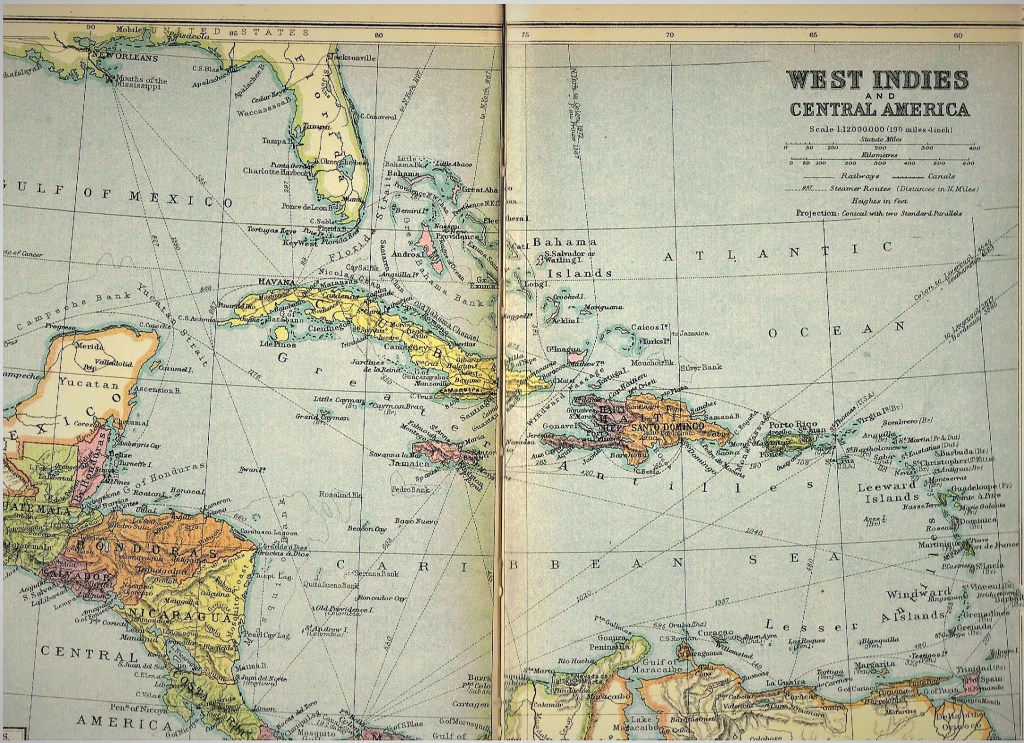

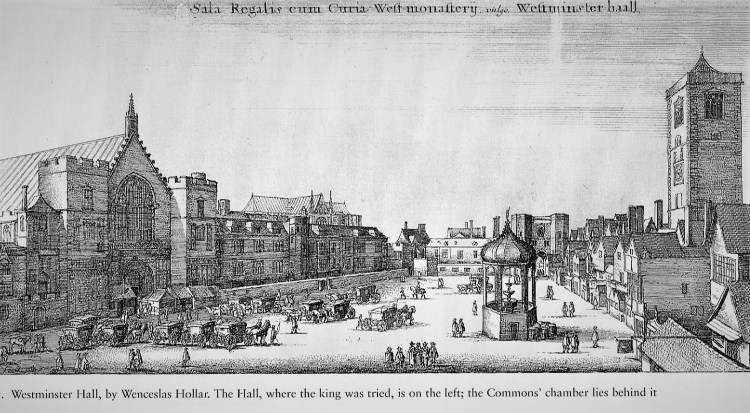

The terms of surrender demanded by Fairfax at Colchester were hard, and reflect the change in the army’s attitude towards the royalist insurgents compared with the besieged garrisons of 1645-46. Both senior and junior regimental officers were granted quarter for their lives, but many of the men were sent to the West Indies as indentured servants. The townsfolk were made to pay a fine of eleven thousand pounds to prevent their city from being sacked. The fate of the commanders was decided by Fairfax’s council of war. As peers, Norwich, Capel and Hastings were sent to London to be judged by parliament, but Lucas, Lisle and Gascoigne were sentenced to military execution, though the latter was reprieved as a foreigner. Lucas and Lisle were shot the same evening. This was entirely within the rules of war as they stood, since not only had they refused the earlier summons, but both men had been made prisoners in the first war and had been released on their parole not to fight again, and Lucas was reported to the council of war as having himself ordered the slaughter of between twenty and forty men of a surrendered garrison. Hamilton, Holland and Capel were executed in front of Westminster Hall six months later, sentenced by an unconstitutional ‘High Court of Justice’ set up by the Rump Parliament. Norwich was also sentenced to death, but was reprieved by the Commons on the casting vote of the Speaker.

The immediate reaction at Westminster to the news of Cromwell’s victory at Preston was to repeal the ‘Vote of No Addresses’. Both Houses did this on 24 August, even before Colchester had surrendered and while men were still in arms for the king in Carlisle, Berwick, Pontefract and other northern fortresses, and while the Prince of Wales was still preparing to sail up the Thames. Cromwell may well have wondered why Charles was thought to be fitter to be treated with after all he had done to renew the warfare than he had been before it restarted, but for the time being he put his responsibilities as a soldier before those of a politician. In spite of his cavalry being so exceedingly battered as I never saw in my life and his infantry shattered… all to pieces, he sent Lambert off with 3,400 men in pursuit of Hamilton and led the rest of his forces in a vain attempt to cut off the retreat of Monro’s brigade into Scotland. The fragments of the Scottish army still at large in England were hunted down by Lambert and the local parliamentarian commanders, and Hamilton was captured at Uttoxeter on the 25th. Cromwell had to deal with nearly ten thousand prisoners as he carried the pursuit into Scotland. He also had to reduce Carlisle and Berwick, which were still being held in the name of the Scottish committee of estates. He had lost fewer than a hundred men killed, though many more were wounded, and together with Lambert, he had waged a brilliant campaign. On arriving in the borders, he judged the situation in Scotland to be so unsettled as to call for military intervention.

On hearing of Hamilton’s defeat, those regions who had been most hostile to the ‘Engagement’, especially Ayrshire and Clydesdale, rose in open revolt, and Galloway soon joined in. Loudoun and the other noblemen of Argyll’s party led the insurgents, in company with Leven and David Leslie, and Argyll himself was not long in joining them. Several thousand men were soon on the march towards Edinburgh, as what became known as the ‘Whiggamore Raid’ threatened to develop into a full-scale Scottish civil war. But the ‘Engagers’ had Monro’s brigade and some other straggling forces with which to shield themselves, and on 12 September they defeated the westerners at Linlithgow and then established themselves at Stirling. In mid-September, Argyll begged Cromwell not to cross the border until they invited him, promising that Berwick and Carlisle would promptly be surrendered. But in Cromwell’s view there were still too many Engagers still under arms for it to be safe to hold back, and he may have known that the pro-Stuart nobility in the north were arming to support them. The committee of estates was now badly split; Argyll’s ‘party’ sat in Edinburgh and on 4 October it renewed an act debarring all Engagers from from public office. That same day, Cromwell entered Edinburgh and eventually convinced Argyll’s committee that it needed English support, leaving some troops behind to help defend the capital. This task was entrusted to Lambert who, with two cavalry regiments and two companies of dragoons, remained there as unwelcome guests for a month.

The Treaty of Newport:

In England, meanwhile, the two major events of September were the opening of the promised negotiation between the king and fifteen commissioners of parliament in the town hall of Newport on the Isle of Wight, and the return of the Levellers to political activity after they had observed while the war lasted. In the summer of 1648 Henry Marten and Lt.-Col. William Eyres had raised a regiment of cavalry volunteers for the people’s freedom against all tyrants whatsoever. The rustics of Berkshire… the basest and vilest of men rushed to enlist, according to Brailsford. They hoped to level all sorts of people, even from the highest to the lowest. But once the second war was won, this private force was incorporated within the army and neutralised. More significant, beginning on 18th September, was the treaty of Newport, as it came to be known. It was scheduled to run for no more than forty days, but in its anxiety to come to terms parliament let it run well beyond its appointed limit. During his annihilation of the Stuart loyalist insurgents, Cromwell seems to have developed his own infuriated conviction that Charles had defied the judgement of Providence by his household’s call to arms in a second civil war, and that the monarchy may have to go. Whether he thought that Charles had to die, even at this point, was quite another matter. After all, there was little point with the Prince of Wales still at large and a whole collection of healthy Stuarts exiled in France and Holland as potential successors.

It was when the the parliamentary Presbyterians realised that the trial of the king was now a distinct possibity that they hastened to pre-empt it by sending their deputation to Newport. But Charles continued to believe that he could continue to exploit the deep differences between between parliament and the army, that one or the other would need him to prevail. Periodically, he also lost himself in a reverie, meditating on his coming martyrdom, confident that his son would succeed him. So Charles was increasingly prepared, even eager, to deliver himself to his fate, convinced that his death would wipe clean his transgressions and follies, excite popular revulsion and guarantee the throne for his son. The English people are a sober people, however at present under some infatuation, he wrote to the Prince of Wales.

He was sure that they would soon recover from this dangerous delirium. On the other side of the extensive negotiations, the presbyterians were relatively easy on the political terms, but pressed Charles I hard to accept the recently completed parliamentary religious settlement, while the independents Saye and Vane were stricter on the constitutional restraints but strove for the relative religious liberty envisaged in the ‘Heads of the Proposals’. But although Charles continued to play his old game of exploiting their divisions, he was weary of being a prisoner and aware of the danger to his life. As time went on he made larger concessions than he had before, as he admitted in a letter to a confidant on 9 October: