The Very Root and Origin of All Creation:

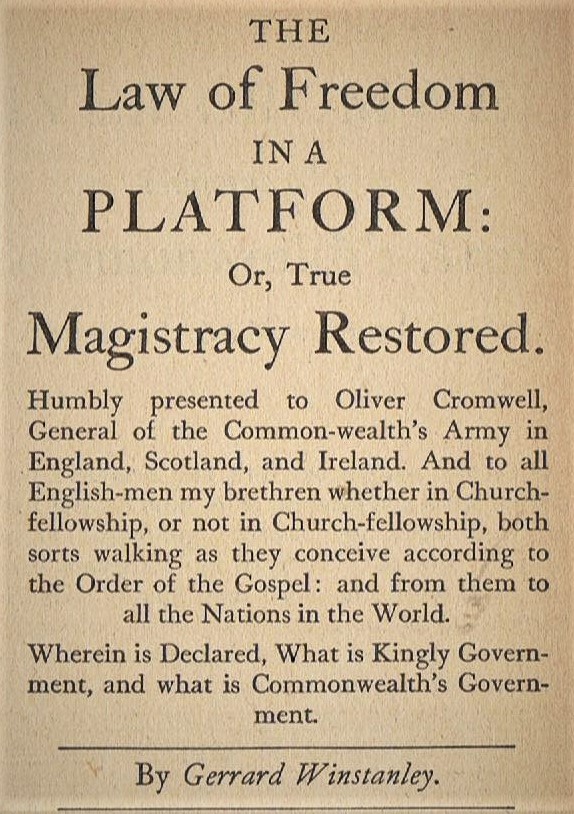

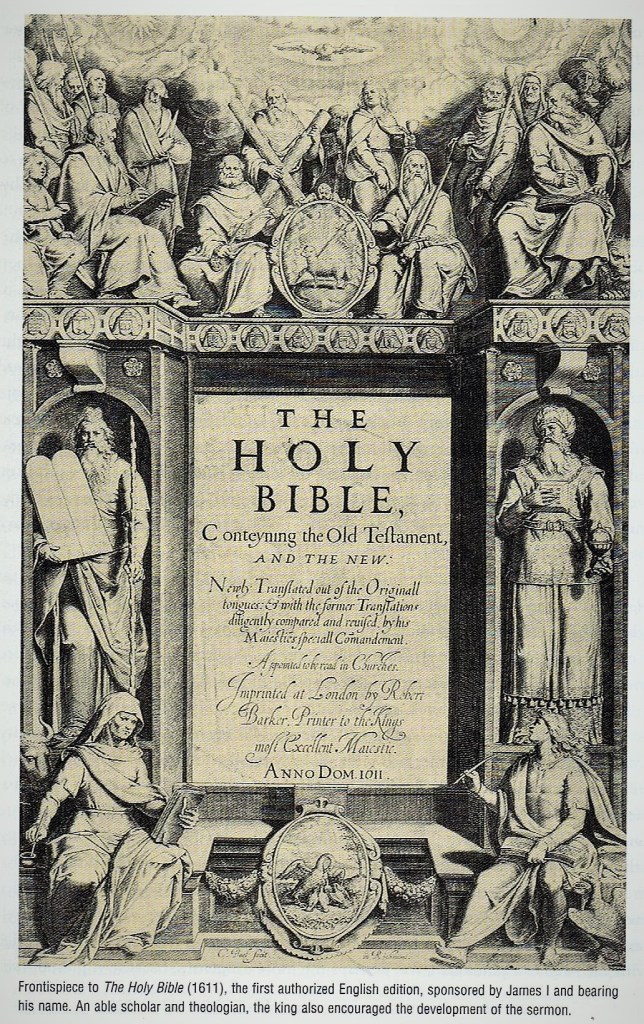

According to dictionary definitions of ‘radical’, from the Latin radicalis, for ‘having roots’ or ‘proceeding from the root’ and meaning ‘fundamental; reaching to the centre or ultimate source’. The twentieth-century philosopher Raymond Williams wrote, in his 1976 publication Keywords, that ‘radical’ had been used as an adjective in English from the fourteenth century, its early uses being mostly physical, to express an inherent and fundamental quality, and this was extended to more general descriptions from the sixteenth century and radical religious ideas became popular among ‘Independent’ puritans in seventeenth-century England and Wales. It did not acquire its modern-day political associations until the late eighteenth century, with the formation of radical groups and parties across Europe and in America in a ‘revolutionary’ period which lasted throughout most of the hundred years into the 1870s on the ‘old’ continent. The Bible, translated into many languages during the Protestant Reformation and providing the impetus for social and intellectual change, qualifies as radical from several different perspectives. The ‘Word of God’ deals with the very root and origin of all creation. It contains a fundamental message about life, life’s centre and its ultimate source. Christians believe that this collection of writings from the ancient world still have a powerful message for the world of the twenty-first century. The continued confrontation of God’s Word with the expressions of the problems and aspirations of peoples in the last half-century have been provocative, and indeed God’s Word should jolt us, for the voice of the Lord breaks down cedars and flashes forth frames of fire (Psalm 29). The God of Abraham, Moses and Jesus Christ is a God of radical transformation and reconciliation, a God who puts down the mighty from their thrones and exalts those of low degree (Luke 1).

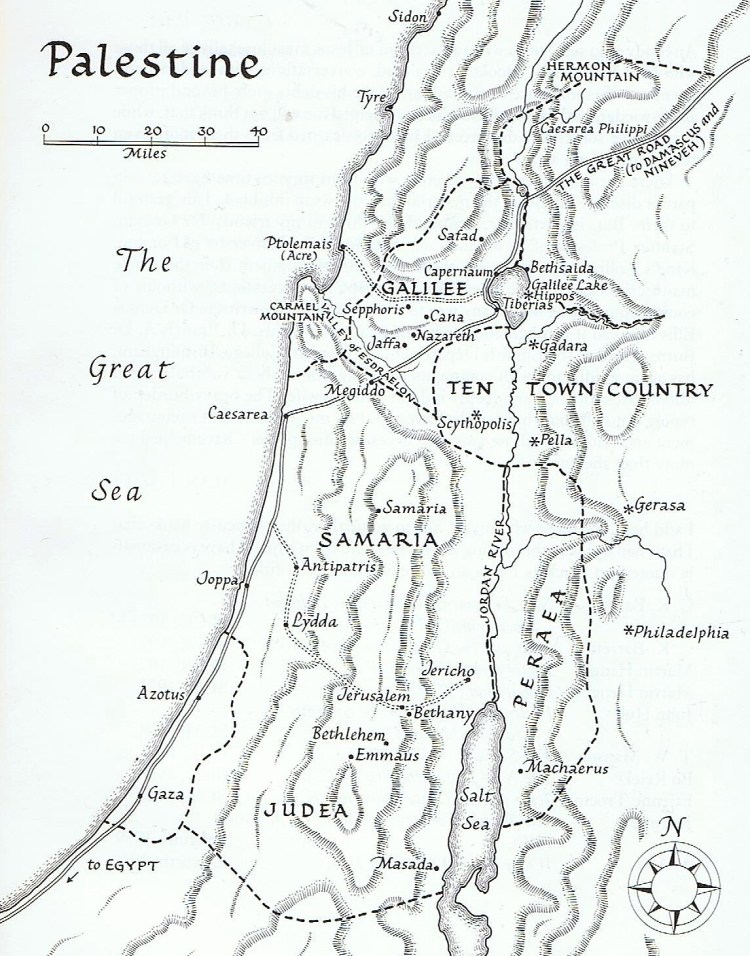

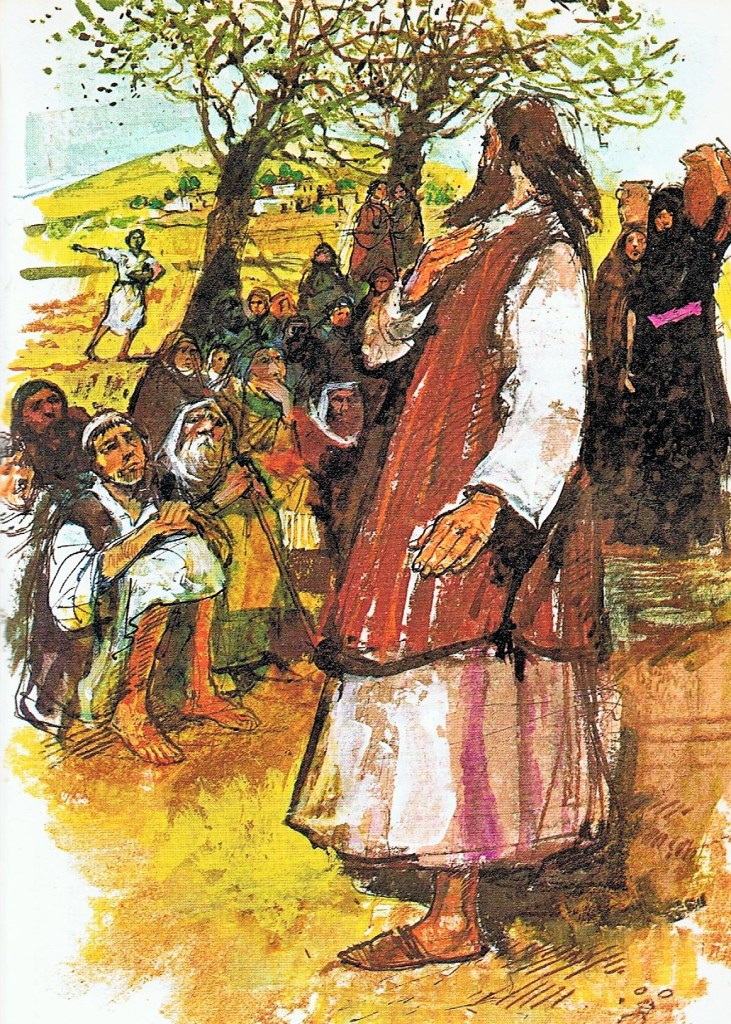

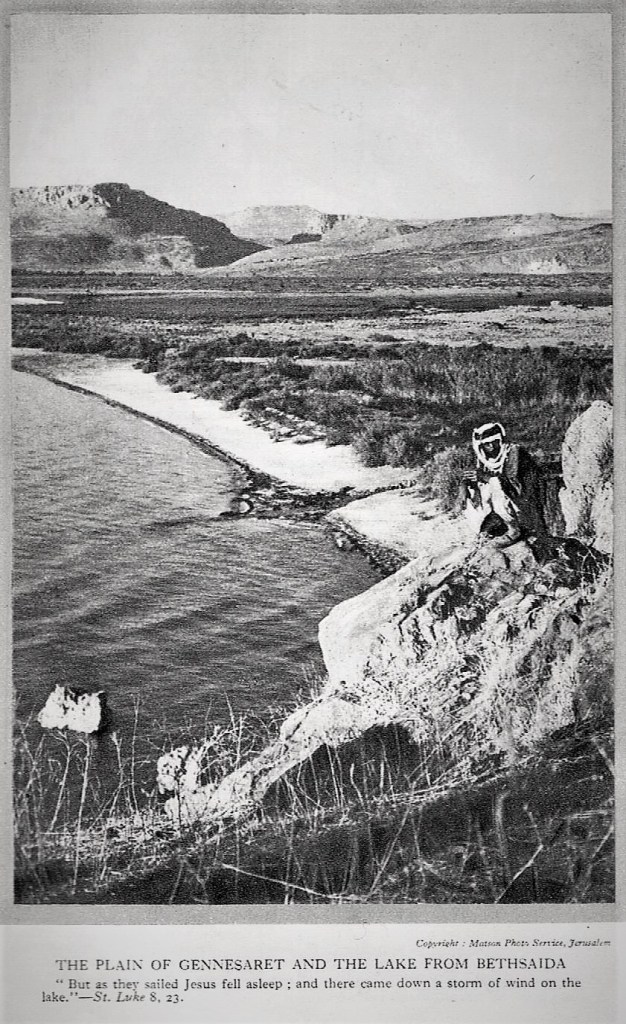

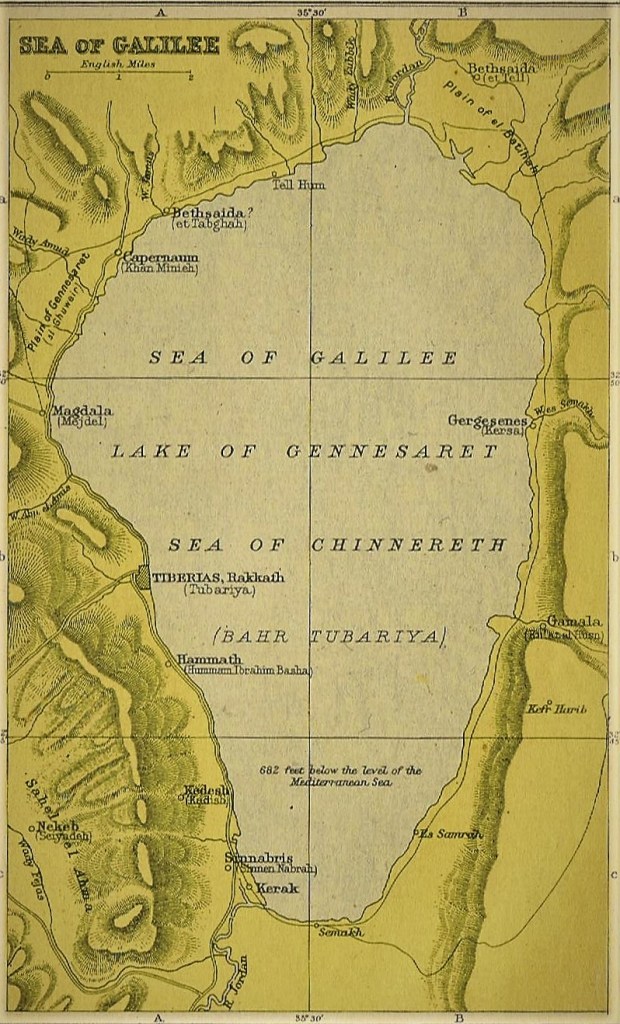

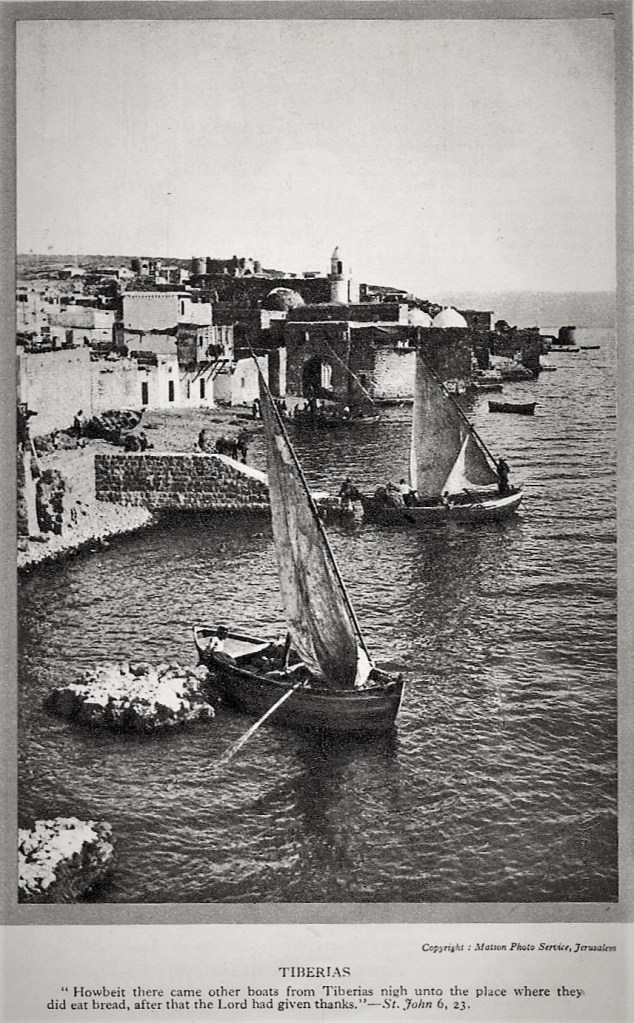

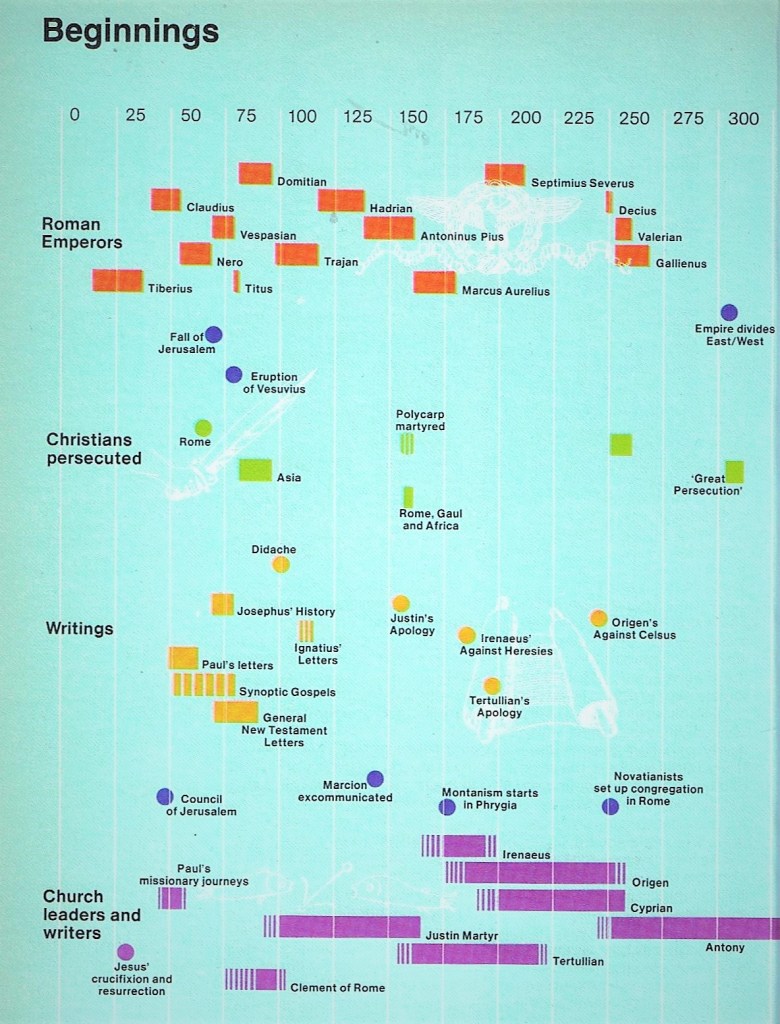

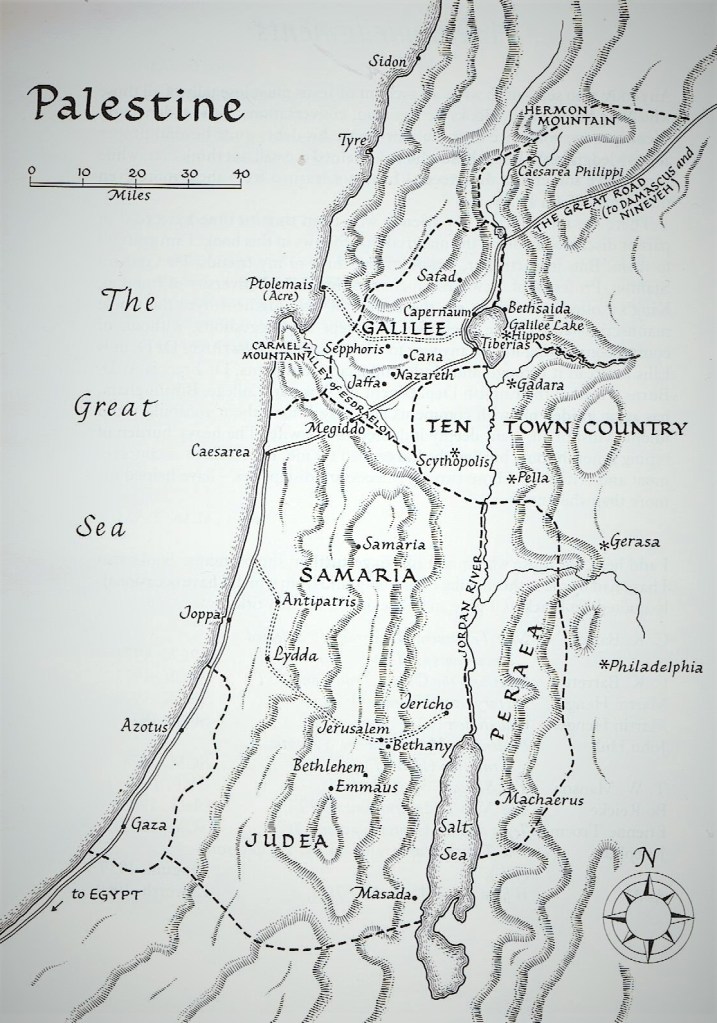

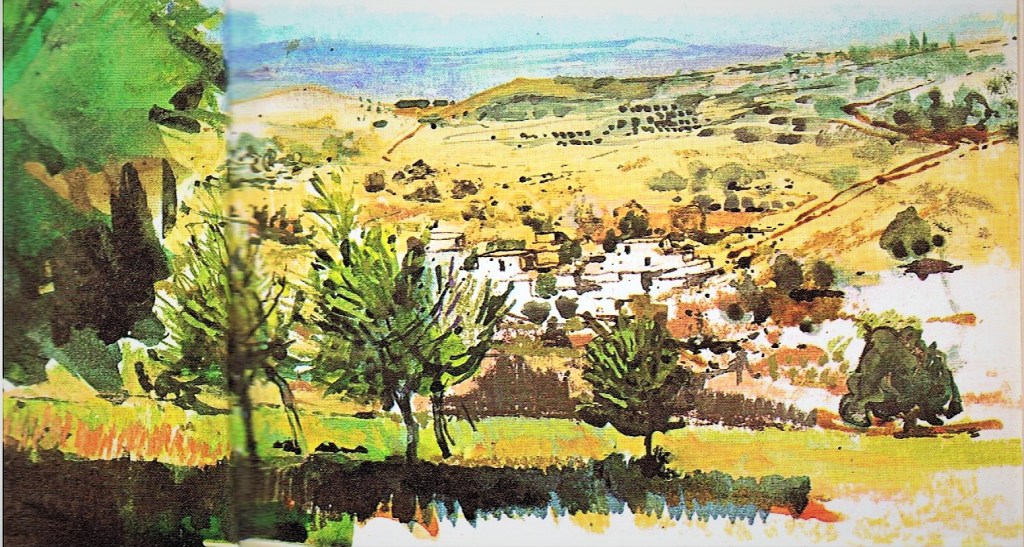

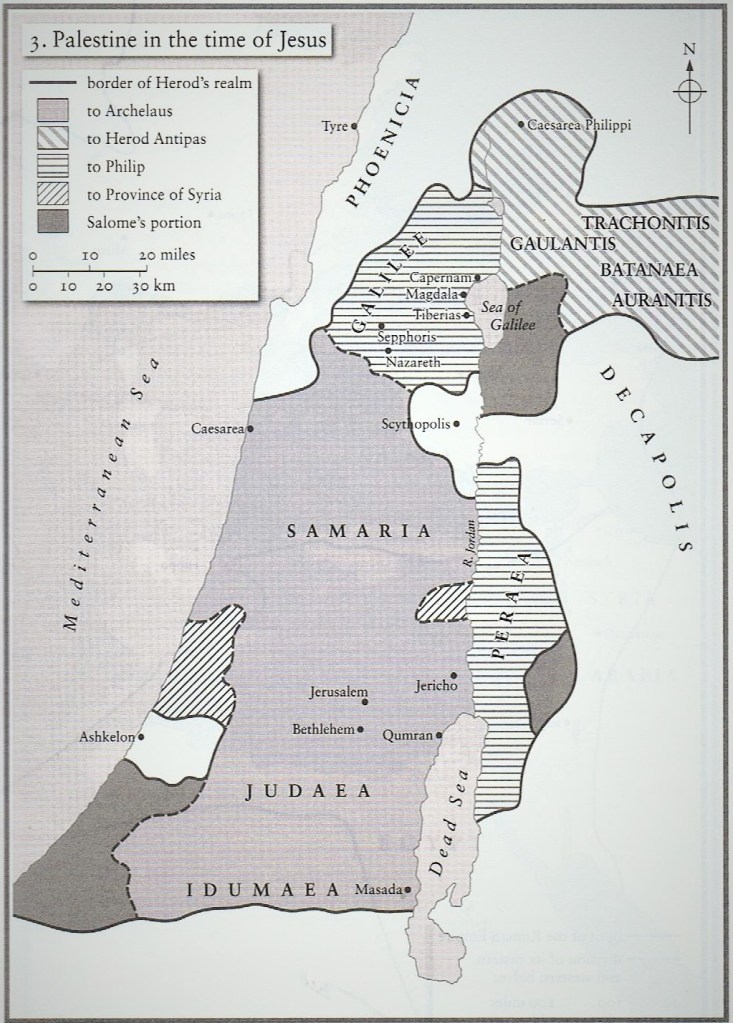

It was out in the world beyond first-century Palestine that what Jesus represented – why he lived as he did, how he died and how he was raised to life – became clearer. It meant nothing less than the vision of a new world, God’s world, and a call to be God’s ‘fellow-workers in its making. Nothing could have made this vision sharper than the sight of men and women, from different ‘races’, classes and nations, becoming Christians. Their old fears vanished; a new joy marked their lives. When Paul tried to explain what a difference Jesus had made to his life, he went back to the book of Genesis and the story of the making of the world as the only kind of language he could use:

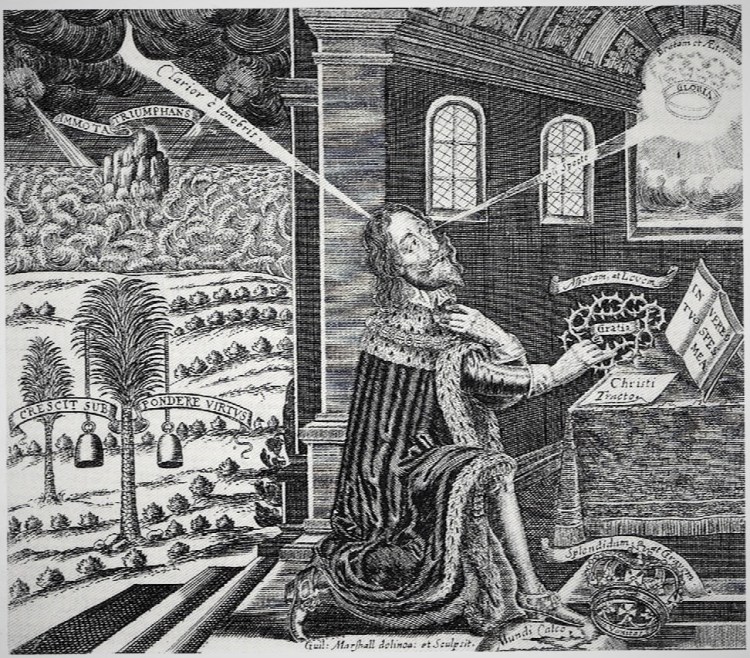

God, who made this bright world, filled my heart with light, the light which shines when we know him as he is, the light shining from the face of Jesus.

II Corinthians 4: 6

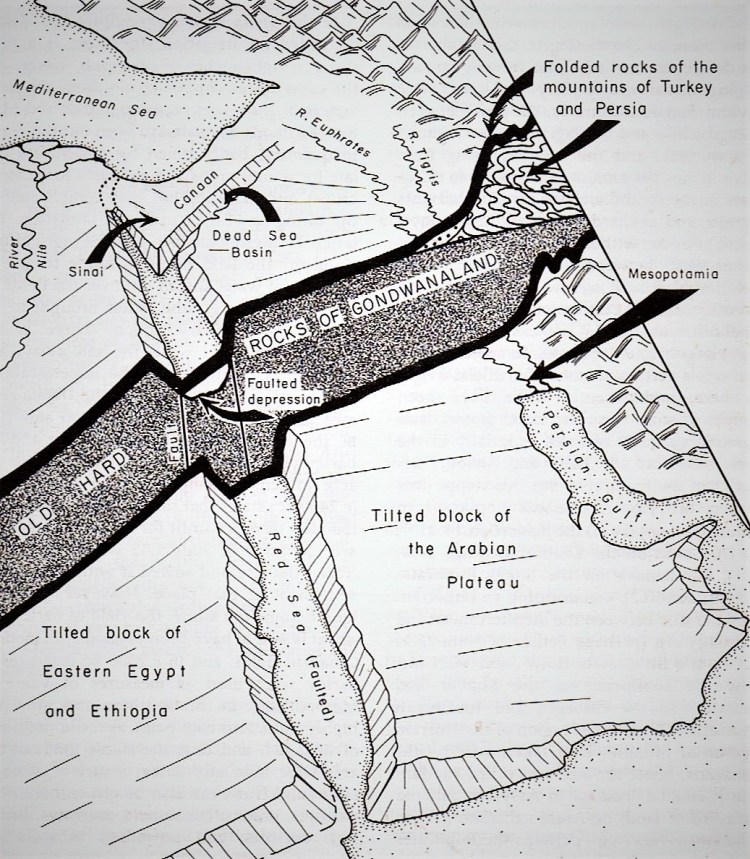

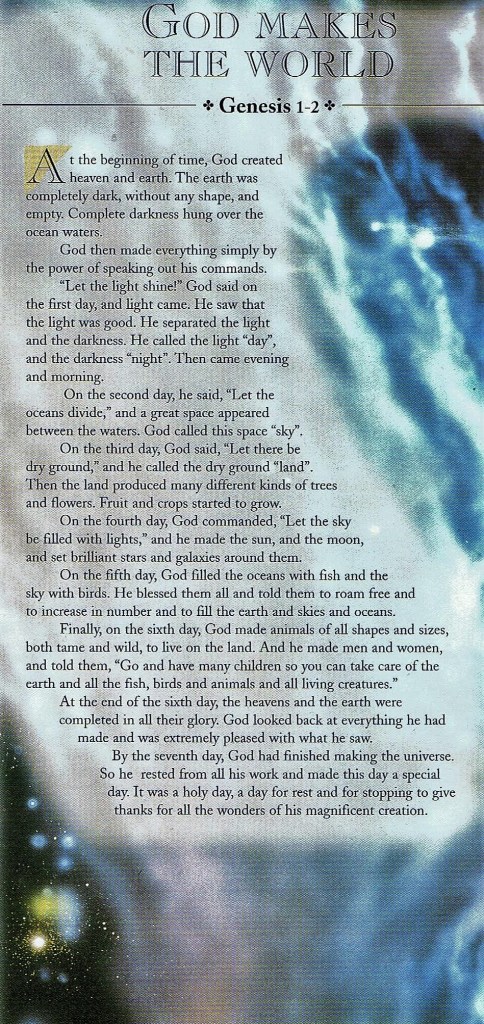

The Hymn of Creation (Genesis 1-2.4a) is ‘priestly’ teaching in Israel at its finest. It is hymn-like, carefully structured, making effective use of recurring words and phrases, e.g. ‘God said … and it was so’, ‘So evening and morning came …’ Its purpose is neither historical nor scientific. It is written by faith, for faith. A good deal of myth and ritual is concerned with the natural forces that shape man’s life. In myth, however, such forces are never regarded as objects; they are always personalised as gods and goddesses. In Canaanite mythology, the interplay of fertility and drought is the conflict between Baal, the god of the fertilising rain and his enemy Mot (Death). In the Babylonian Enuma Elish, the struggle is between Tiamat, primaeval chaos, and Marduk, the champion of the gods. Just as there are many different and conflicting phenomena surrounding man, so there is an inevitable polytheism in such myths. By contrast, Gen. 1 is uncompromisingly monotheistic. The Hebrew word for ‘the deep’ (tehöm) in 1: 2 is sometimes claimed to be a reflection of Babylonian Tiamat. At best it is a literary echo. The entire theme of creation coming by way of conflict between rival gods has been excised. Here there is but one God who speaks, and his word is effective to create. The same point is made in 1: 14-19. Instead of speaking about the sun and the moon, the hymn refers to ‘the greater light’ and ‘the lesser light’. Sun and moon were common objects of worship in the ancient Near East. It is as if the hymn is deliberately demythologising them. It refuses to name them directly and insists that they share in the finitude of all created things.

The word ‘create’ used throughout this chapter is only used in the Old Testament of God and his activity. Nothing in the world may be equated with the divine. But neither is the world in any sense the enemy of God. All are part of his good creation, including man, the apex of the pyramid of creation. When the hymn comes to the making of mankind (1: 26), the form of expression changes. It becomes more personal: ‘Let us’ instead of ‘Let there be’. The plural ‘us’ here probably derives from the mythology of the divine council which the supreme god consults when important decisions are to be taken. But that, in the hymn, is no more than a literary allusion; the plural ‘Let us’ switches immediately to the singular in 1: 27. The prose is slightly mesmerising as it takes its slow and stately course, and it altogether lacks the freshness of the ‘saga’ style of much of the Hebrew narrative of the Pentateuch. The priestly writers seldom tell a story with varied characters and interesting incidents, but rather rehearse set pieces of ritualised events. The dignity and the power of the writing are undeniable, as is the departure in style both from that of ‘saga’ and from the work of the Deuteronomist school. The priestly style derives from those who controlled the Second Temple, or perhaps from their predecessors who, during the exile, worked to classify and elaborate the rules for Temple worship. The book of Ezekiel, who was a priest as well as a prophet and who worked among the exiles, has passages in a similar style, particularly in the regulations about life in the restored Promised Land in Ezekiel 40-48. We might expect to find whole books written in one or another of these styles, but this is not what we encounter in the Hebrew Bible. Here is the climax of the priestly Hymn of Creation:

Then God said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them, and God said to them,

“Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it, and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.”

And God said, “Behold, I have given you every plant yielding seed which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food. …”

First chapter of Genesis, verses 26-29: Revised Standard Version.

The keyword in verse 26 is ‘image’, ‘likeness’ being a more general term that merely emphasises the concept of ‘the image of God’. But what does that phrase mean? Every age has attempted to read into this phrase its own highest ideal of man, whether that is thought of in terms of the immortality of the soul or the possession of reason. In the context of Genesis 1, the phrase seems to be defined by the words that follow. Just as God is Lord over all creation, so man exercises under God a secondary lordship over the rest of creation (cf. Ps 8). Inherent in such delegated lordship, however, is the thought that man is responsible to God for how he exercises his lordship. John Barton (2019) concludes this passage in a more modern version which is repetitive of the previous stanza: And to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food. This basic right of the whole of mankind to an adequate supply of food is something which was re-emphasised in the Vatican Council II cyclical, The Church in the Modern World, no. 69:

God intended that the earth and all that it contains for the use of every human being and people. Thus, as all men follow justice and unite in charity, created goods should abound for them on a reasonable basis. … A man should regard his lawful possessions not merely as his own but also as common property in the sense that they should accrue to the benefit not only himself but of others. … The right to have a share of earthly goods sufficient for oneself and one’s family belongs to everyone. … If a person is in extreme necessity, he has the right to take from the riches of others what he himself needs.

The styles, themes and ‘sagas’ of the Creation narratives:

The modern church statement above echoes the language of the first chapter of Genesis which, together with the early verses of chapter two, is a classic example of the priestly style which we encounter most in the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament. Much material in this style consists of legal prescriptions, often about the details of Israel’s worship: in fact, the central section of the Pentateuch, from the middle of Exodus, through the whole of Leviticus and into the middle of Numbers, seems to have a priestly origin. In addition, there is priestly writing interwoven with older stories in a ‘saga’ style throughout Genesis and the first half of Exodus, where some of the well-known stories about the patriarchs and Moses exist in two versions, one in saga style and one in priestly.

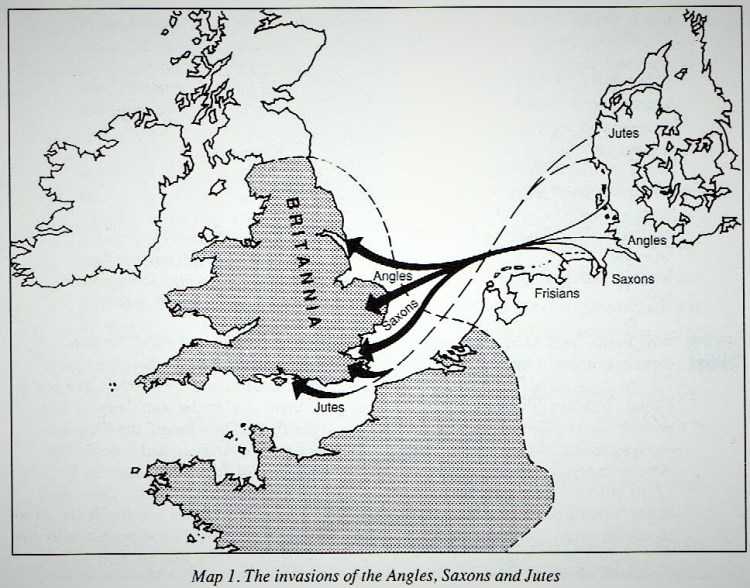

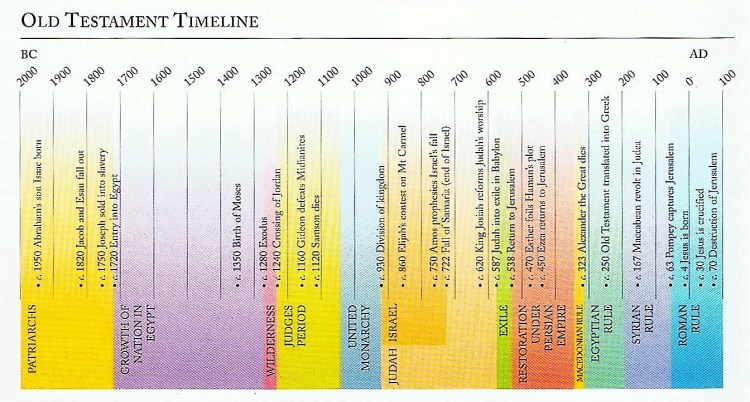

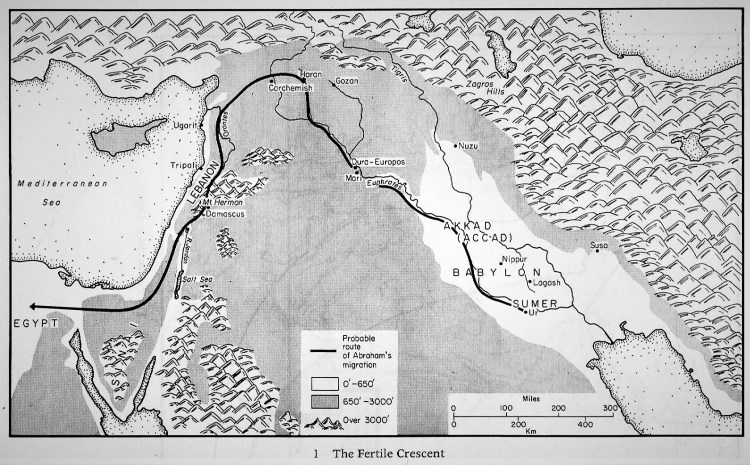

Increasing knowledge of the religions and literature of the ancient Near East makes it clear that the authors of Gen. 1-11 are handling the themes and myths of ‘the Creation’ in a common currency, particularly in Mesopotamia. The earliest literary strand in the Pentateuch is known by scholars as the ‘J’ document, written during the period of the kings David and Solomon. It reflects a spirit of confidence and fulfilment which can be fully understood against a background of national ascendancy achieved under the two kings, rather than against the background of the period after the disruption of the state in 922 BC. This would date the composition of the ‘J’ document to about 950 BC. In composing his work, the author of ‘J’ was dependent on an earlier Israelite national epic (‘G’) which already contained the main themes of the salvation-history from the call of the patriarchs to the entry to the land of Canaan, together with much old material which had been assembled during the period of the judges and fitted into the framework of that epic. The ‘Yahwist’ author of ‘J’ expanded this framework by including the primaeval history and at the same time employed the material which it and other sources placed at his disposal in such a manner as to set forth his own theological interpretation of the salvation-history. The Yahwist’s narrative of the primaeval history begins with creation (Gen. 2: 4b-25) and the fall of man (Gen. 3). Here the ‘J’ source takes us into the world of story myth. When such stories provide explanations of curious phenomena in the world, they are called aetiological myths (from the Greek, aition, for ‘explanation’ or ’cause’). Many explanations of different depth and interest may be offered within the one story.

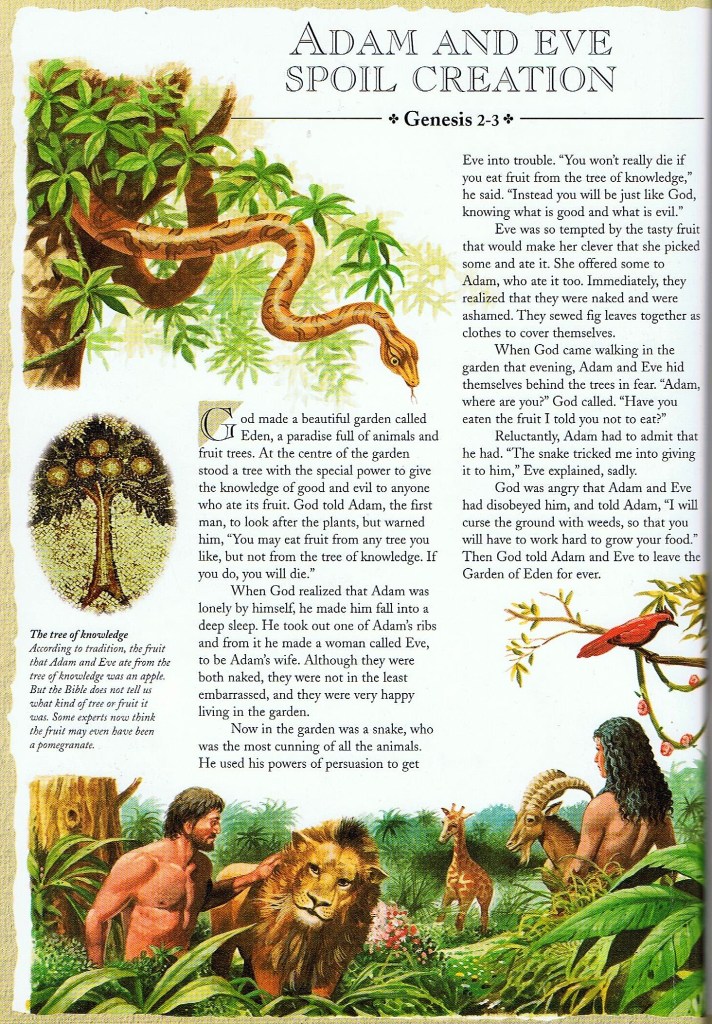

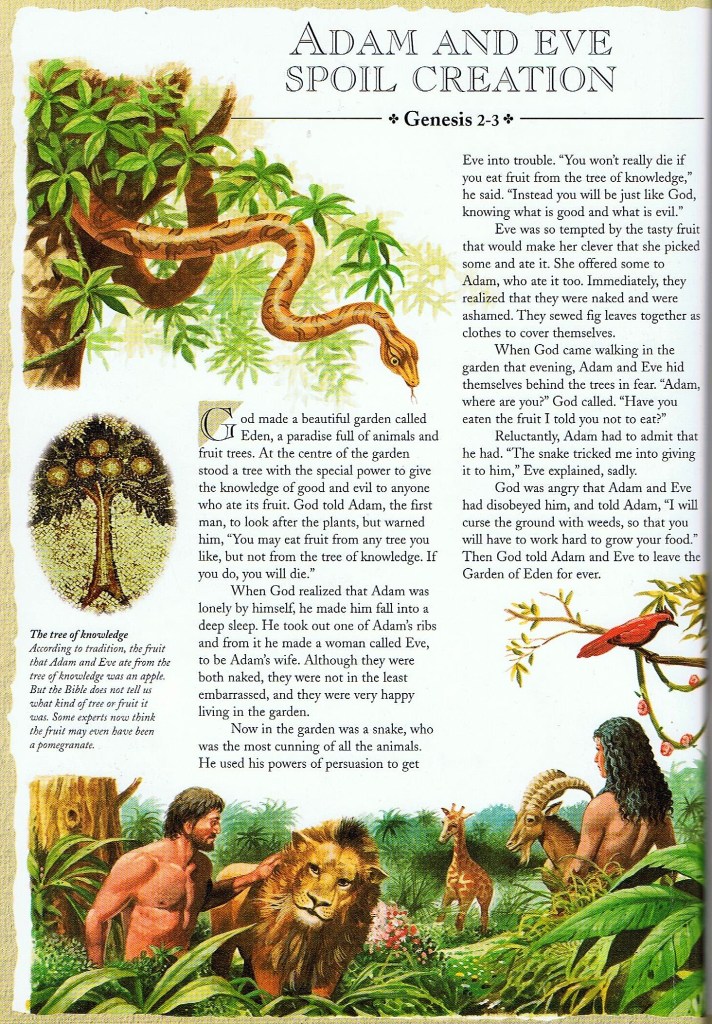

This section of Genesis has some curiously rough edges, which may reflect once independent stories – two accounts of a man placed in the garden (2: 8, 15), two accounts of the clothing of man (3: 7, 21), and two trees. However, the passage must be read as a whole. Genesis 2: 4-25 preserves a saga-style version of the creation of the human race, which is different from Genesis 1 not only in details (man is created before woman, not at the same time, with the creation of the animals occurring between the two) but also in style: it is much more obviously a story than the priestly version. God talks to the man and gives him his orders to avoid eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and then experiments with creating the animals to be his companions; and when that fails to work, he creates the woman. God is much more of a character in the story than the all-powerful figure in the priestly version of the creation. There are no repetitions or formulaic language in this second account. There are, however, attempted answers to many questions – why the serpent is such an odd creature and why there exists an instinctive antipathy between it and mankind (3: 14-15); why there is so much pain in childbirth (3: 16); why the farmer’s work is so hard (3: 17-19); why marriage exists as an institution and why there are different sexes (2: 20-25). All these ‘whys’, however, are peripheral to the central thrust of the story.

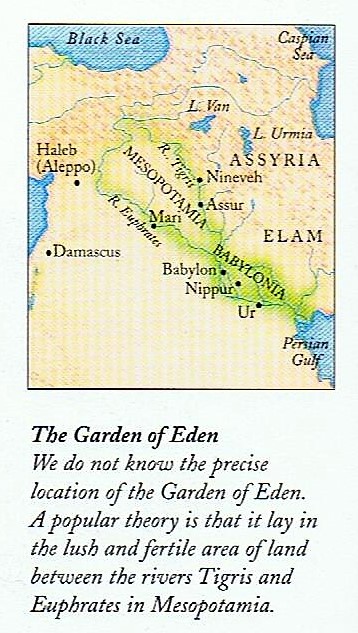

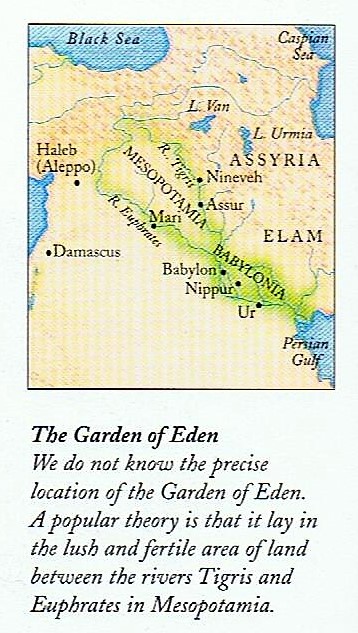

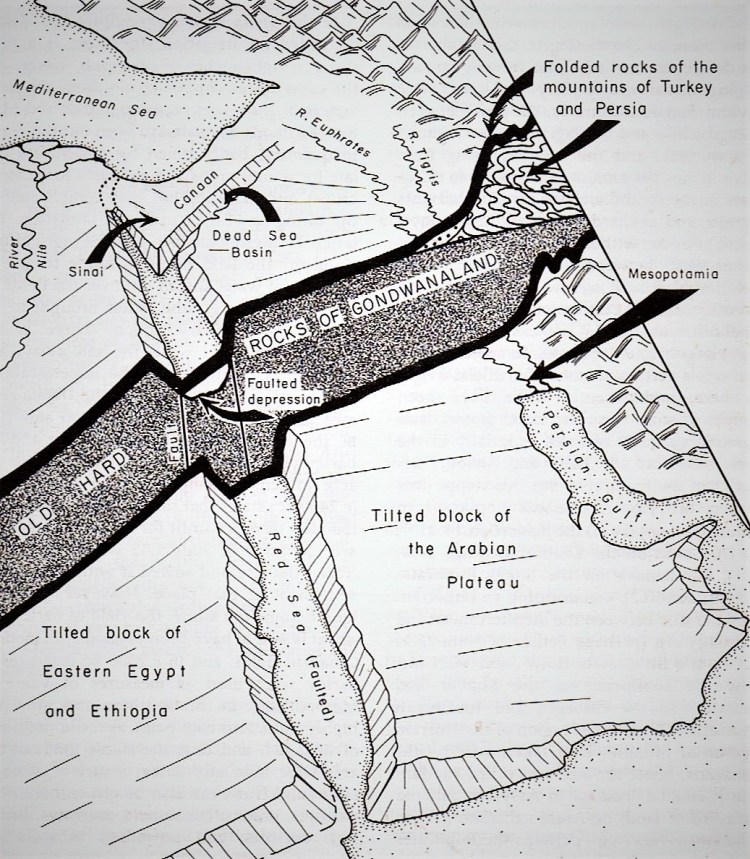

The barren desert (2: 4b-7), fertilised by supernatural water (the ‘mist’, 2: 6), is a very different picture from the primaeval watery chaos of Gen. 1. It is merely the setting for man, the ‘earthling’ formed from ‘the earth’ (Hebrew: adämäh). Shaped by a divine potter, this man became a living being or creature (not ‘soul’), when God breathes into him the breath of life (2: 7). This man is placed in a position of responsibility in the garden of Eden, almost certainly a mythical garden paradise, since all attempts to locate it from the geographical clues in 2: 10-14 have come to ‘a dead end’. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil in this garden has provoked endless discussion. ‘Good and evil’ are perhaps best interpreted in this context to mean ‘everything’, just as ‘hot and cold’ are used to describe a range of temperatures. The temptation which dangles before man is that of grasping at a totality of knowledge which is the prerogative of God. Once possessing all knowledge, he would know the whereabouts of the tree of life and thus be in danger of trespassing upon another divine prerogative, immortality. When temptation conquers, all goes wrong. The garden of delight becomes the garden of disenchantment. Childlike trust is replaced by a guilty conscience. Harmony turns to friction. The life of rewarding endeavour becomes an irksome struggle for existence. Death enters the scene.

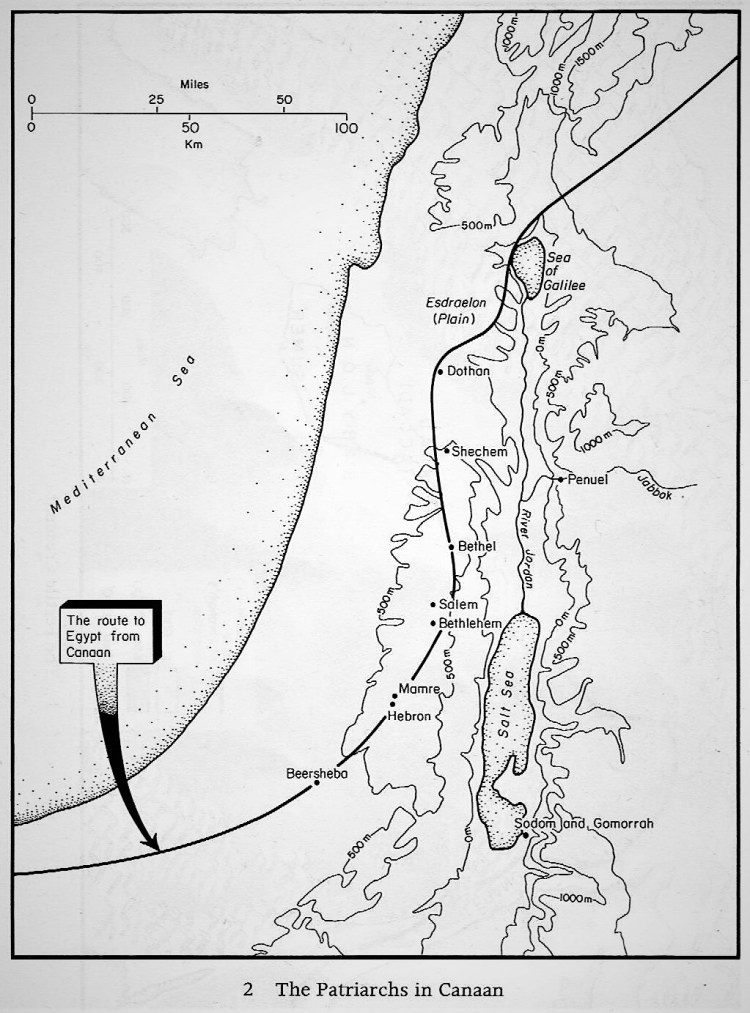

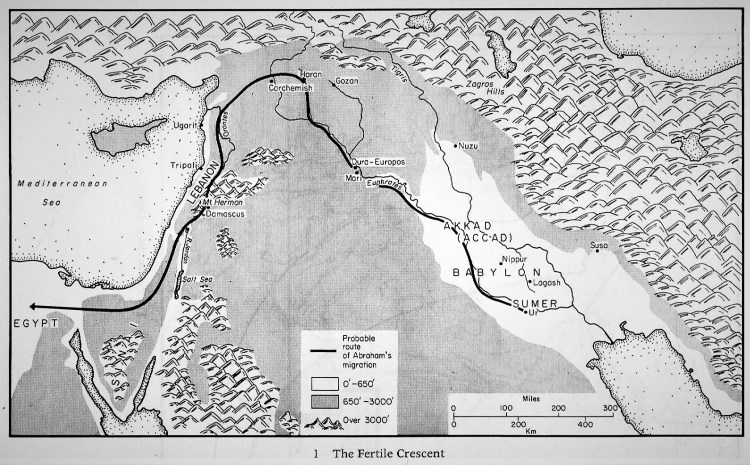

In these ways, the psychological insights in the story are profound. There is the subtlety of the temptation (3: 1-6), the ‘passing of the buck’ mentality (3: 12-14). But the heart of the story is theological, that the elemental sin in man’s nature mars his world. He is a creature in rebellion against his Creator. He refuses to accept that he himself is not omniscient or the centre of the universe. Like Gen. 1, this section in chapters 2-3 speaks of the potential greatness in human nature. Man’s ‘lordship’ is indicated by the way in which Adam gives names to the other creatures (2: 19f.). But this lordship, as Israel had every reason to know, is a flawed and marred hegemony. In prefacing his epic of Israel’s salvation-history with the primaeval history the Yahwist sought to achieve several theological objectives. In the first place, he affirmed that Yahweh was not only the God of Israel but the Creator of the world and Lord of all the peoples of the earth. He also placed the history of his own people within the context of world history in general from the beginning and, more important still, asserted that Israel’s election and redemption by God were not merely of national significance but of universal significance since it was through Abraham and his descendants that God wished to bring salvation ‘to all the families of the earth’ (cf. Gen. 12: 3).

Throughout his narrative of the primaeval history, the Yahwist describes in bold colours man’s sinfulness and persistent and increasing rebellion against God. At the same time, while at every stage God’s judgement upon man is fully narrated, the Yahwist stresses throughout God’s tender care for his creature and his will to save: Yahweh perceives man’s loneliness and creates woman as a helper fit for him (Gen. 2: 18); then, having pronounced judgement upon Adam and Eve for their rebellion against him, he makes them garments to conceal their nakedness (Gen. 3: 21). The stories of Genesis as a whole provide adequate testimony to the breadth of vision and dimension of the Yahwist’s theology. Two aspects of the history of salvation which he wrote are particularly worthy of emphasis. In the first place, he transcended the older and narrower presentation of the salvation-history by seeing it and describing it as having been orientated not merely towards Israel but as being part of God’s universal plan to bring salvation to all the peoples of the world. Israel was indeed Yahweh’s peculiar people, but as such the agent through which he purposed to gather all men to himself. By composing the primaeval history, the Yahwist succeeded in adding this dimension to the salvation-history and, from the beginning to the end, the Yahwist’s epic asserts that no matter what obstacles human weakness and sinfulness may create, God’s will to save emerges triumphantly. Despite the persistent attempts of men and nations to frustrate his purposes, Yahweh’s word is established.

The Yahwist’s achievement is further illuminated when the period in which he composed his epic is recalled. He wrote at a time when the old tribal system of early Israel had all but disappeared and Israel was being established as a nation-state under David and Solomon to play a role in the international affairs of the known world. Israel was being exposed to ideas and cultural influences from far beyond the borders of the little land in which it had settled, and the international sphere in which Israel now found itself, especially during the reign of Solomon, must have threatened to render the old faith inadequate if not altogether irrelevant. It was the noblest achievement of the Yahwist that he presented an interpretation of Israel’s history and its divine election so as to make them relevant to the new situation in which it found itself. There was now a larger world around Israel, and that, as the Yahwist saw it, was itself all part of the unfolding drama of salvation. This meant that the Yahwist was not just narrating what was long past; he was not merely looking backwards. Rather, his work was pointing forward. God had called the fathers and given them the land, and there was fulfilment in that. But the process of salvation continued so that the element of promise and expectation was still there. The Yahwist’s epic, therefore, pointed forward to the full realisation of God’s blessing upon the world.

How, then, can narrative books be religiously important, and how were they important for religious thought in ancient Israel? Certainly not, according to John Barton, as ‘teaching’, though possibly as providing fables to illustrate how (and how not) to live. But for this purpose, the OT narratives are often too complex to be of much direct use. They may well have served as means to draw people in and engage them in a narrative world that leads to no definite conclusions but illuminates the human condition obliquely. If so, this is very far from how they have been read in some strands of later Judaism and Christianity, where they have often been reduced to sources for ethical guidance and instruction. Modern biblical scholarship has rediscovered the ‘story’ element in the ‘history books, as they are traditionally known. It has recognised that we cannot simply produce a simple chronicle from them, but that we need to establish from them the identity of the people of Israel. Rather than being archival material, they are national literature, contributing to our understanding of the history of the nation through the insights they give us into how events and social movements were understood in the time in which they were written, rather than by providing reliable information about the history of the time they purport to describe.

This realisation arrived early in the case of Chronicles, which scholars have, for a long time, considered mainly as evidence for religious attitudes in the Persian age, rather than as telling us much that is reliable about the sweep of history that it surveys. The idea that primary source evidence about Israelite thought from the eighth to the sixth or fifth century B.C. could be derived from books purporting to provide an account of the ancestors of Israel and their kings from the second millennium onwards, arrived much later, but it now one which is widely shared. It is still sometimes shocking to devout Jews and Christians, who see it as reductive to the status and authority of the Bible. But most believers long ago accepted that Genesis 1, for example, is not true in the sense of being an accurate, scientific account of the creation of the world, so that scepticism about the details of the narrative books can also now coexist with continuing to respect the texts as religiously inspiring and informative. We can follow a critical path while at the same time retaining our connection with the traditional use of the Bible by understanding the value of its profound narratives.

Radical Truth, ‘Fundamentalism’ and Rational Reality:

We must, however, take note of one of the issues encountered by students of the Bible since the nineteenth century: its apparent conflict with science. On the surface of the texts, the Hebrew Bible implies that the world was created in the fifth millennium BC: Archbishop James Ussher (1581-1656) calculated, using the figures in various books of the Bible, that the creation occurred on 23 October 4004 BC. This is still believed by so-called young-earth creationists, but in the nineteenth century, a scientific evaluation of the age of the universe became entirely obvious in the light of scientific discoveries. The same century saw the assertion that in Genesis 1 God is shown to have created each species of plant and animal separately challenged by evolutionary science, through the work of Charles Darwin (1809-82). As Owen Chadwick put it:

The Christian church taught what was not true. It taught the world to be six thousand years old, a universal flood, and stories in the Old Testament like the speaking ass or the swallowing of Jonah by a whale which ordinary men (once they were asked to consider the question of truth or falsehood) instantly put into the category of legends.

Owen Chadwick (1972), The Victorian Church, Part Two: 1860-1901. London: SCM Press, p. 2.

More recently, Philip Kennedy has commented:

The consequences of Darwin’s work are very far from being appropriated by officially sanctioned Christian doctrines. For example, the current ‘Catechism of the Catholic Church’ solemnly teaches that the biblical story of Adam and Eve, or rather the third chapter of the Book of Genesis, ‘affirms a primaeval event, a deed that took place at the beginning of the history.’ This teaching is solemnly declared. It is also false. Chapter 3 of Genesis is a myth. It does not provide any reliable information about the historical genesis of a human species. What it does say about human origins is false. To regard it as factually true is to violate its literary form as a myth.

Philip Kennedy (2006), A Modern Introduction to Theology: New Questions for Old Beliefs. London & New York: I. B. Tauris, p. 235.

The last sentence in this quote points to the practical effect of scientific knowledge on Biblical Studies: it made scholars and readers alike see that the Bible contained myths and legends, which might be full of wisdom and insight of many kinds but which did not provide any scientific information or historical account of human origins. The effect was not limited to claims made in the Old Testament. When Paul affirms that death entered the world because of sin (the sin of Adam: Romans 5: 12), this too is rendered clearly untrue through the observation that human beings, and their hominid predecessors, have always been mortal, as are all other organisms. This is important because it challenges a major element in the Christian story of the fall of man and his redemption, which Barton calls ‘God’s rescue mission’, in which Adam’s sin plays a central role. This too, and not just Genesis, has to be understood in a non-literal way or relinquished as a complete fabrication, or ‘fairy tale’. On the whole, by the end of the nineteenth century, biblical scholars had made this transition, with varying degrees of enthusiasm; but ecclesiastical authorities, and Christians of a conservative disposition, have in many cases still not made it today. Biblical literalists continue to defend the historicity of Adam and Eve, Jonah’s big fish and Balaam’s talking donkey, to the delight of atheist critics of Christianity.

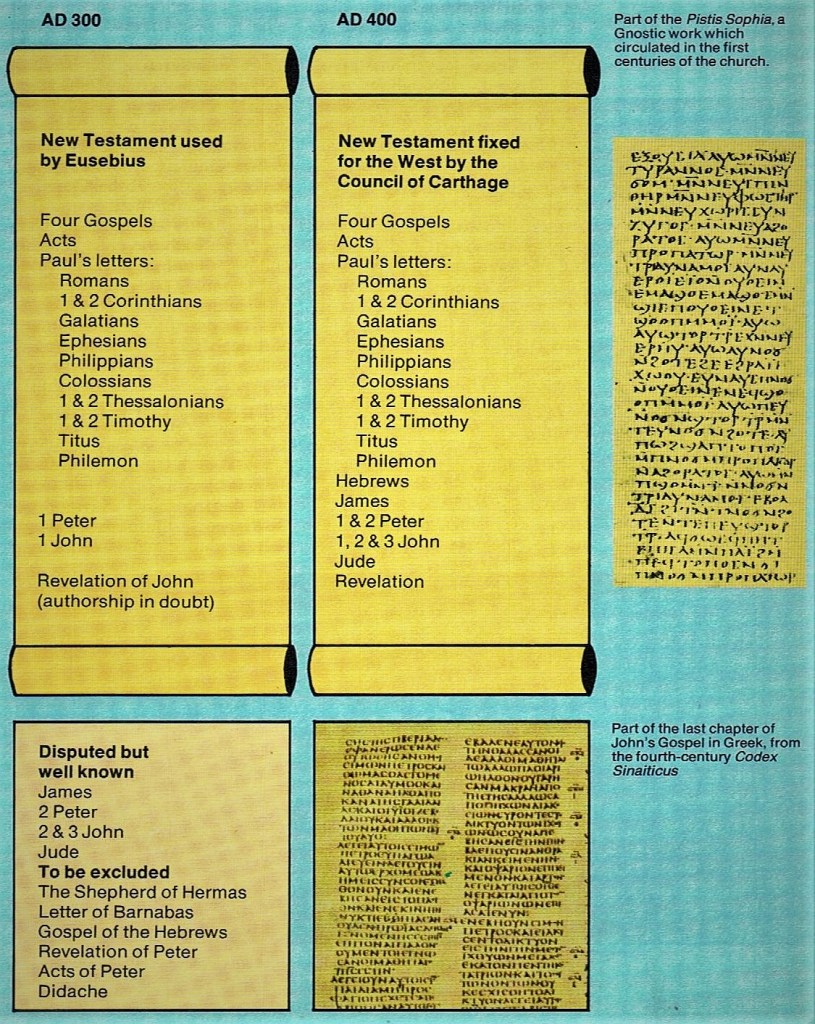

Neither the Old Testament nor the New Testament books themselves contain any claim by their authors to have been dictated or even directly inspired, by God. The chief passage relevant to the inspiration of texts (as opposed to people) is II Timothy 3: 16-17:

All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that everyone who belongs to God may be proficient, equipped for every good work.

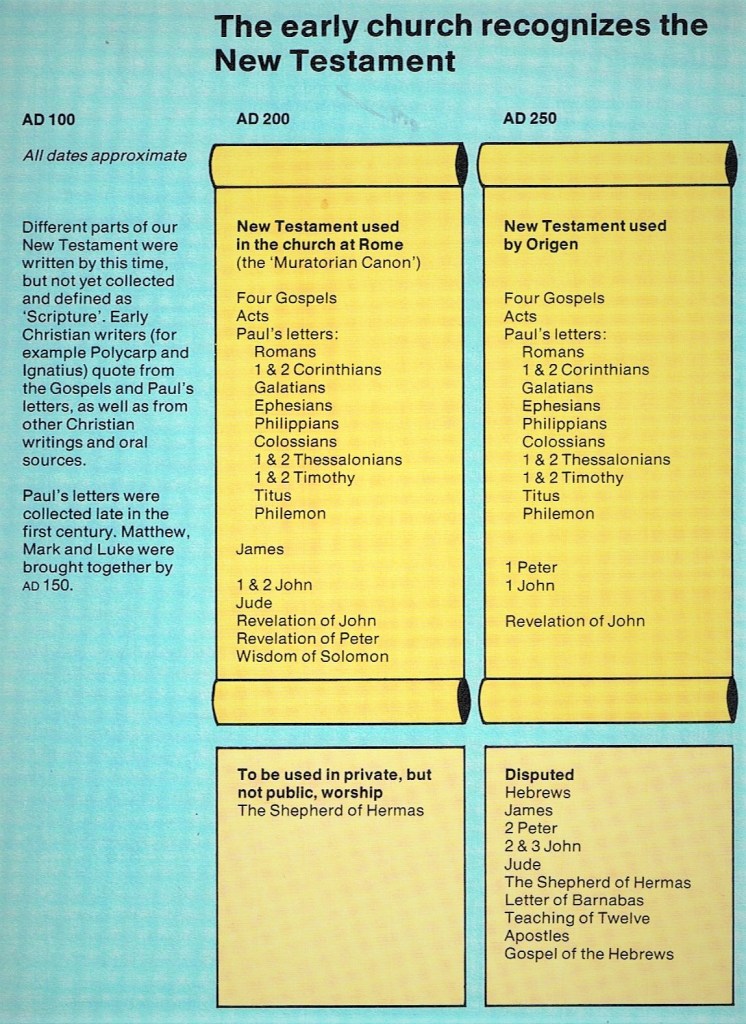

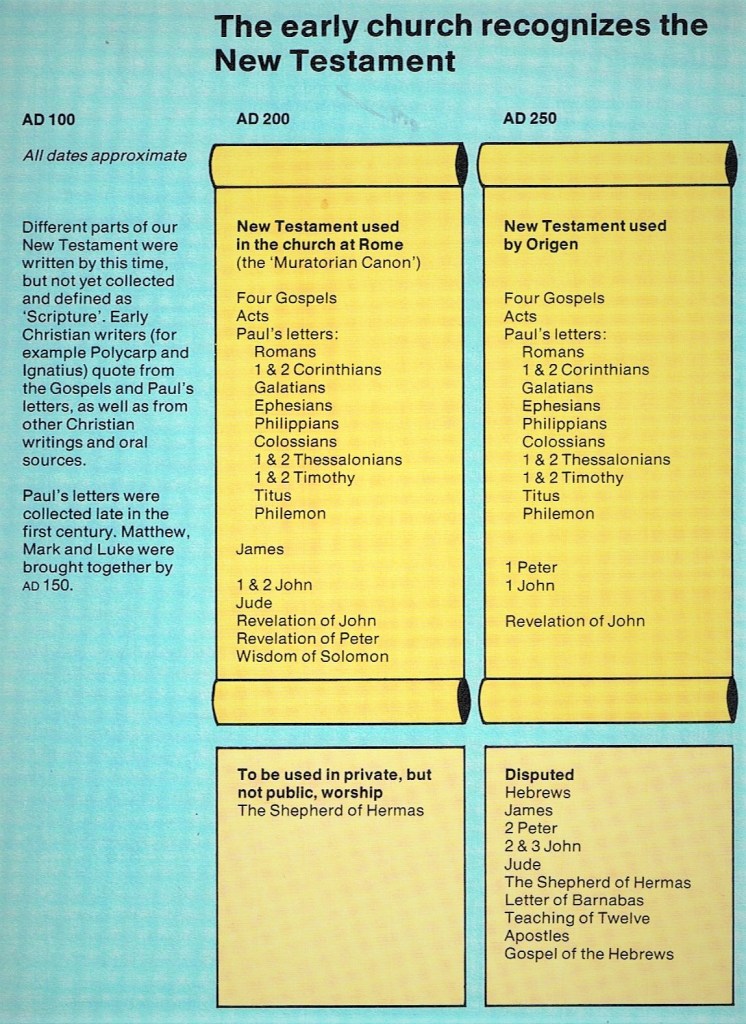

In this passage, ‘Scripture’ must surely refer to the OT, though by the time II Timothy was written some of Paul’s letters seem already to have been regarded as such, as in II Peter 3: 16. Both these letters, however, were unlikely to have been written by Paul, and both seem to be among the last-written books of the Bible (see below). It also seems unlikely, had Paul had a hand in these letters, that he would have claimed that ‘hand’ to have been directly ‘inspired’ or dictated to by God. ‘Inspired’ literally meant ‘God-breathed’ in the Greek of that time, which would imply that God was the author of the biblical books in a way not otherwise asserted within the books themselves. In Judaism, it has been customary to see the books of the Hebrew Bible as given by the spirit of God, though the exact mechanism is not much discussed. Despite the paucity of references within the Bible itself, Christians have often quoted II Timothy and described the Bible as the product of divine inspiration. Dictation theories are unusual today: even very conservative Christians allow that the biblical authors contributed much from their own minds. But accepting this makes it difficult to exclude the possibility of human error, inaccuracy or interpretation in the writing of the biblical texts, which conservatives are concerned at all costs to avoid admitting.

Some ‘conservative’ Christians do indeed hold that since Genesis 1-2 says that the world was created in six days, it must have been so created – a literal interpretation. Others are more concerned with the Bible’s infallibility than with reading all of it literally, and will sometimes accept metaphorical readings if that will preserve the fundamental truth of the texts. Some will maintain that ‘day’ does not literally mean a period of twenty-four hours, but a vastly longer ‘period’. Since God inspired the writers, they cannot have been in error; and since we know that the world formed and life evolved over billions of years, that must be what Genesis really means. Along with John Barton, I have often heard Christians insist that there must have been six periods in the creation of the earth, and even that this is supported by science in an effort to avoid accepting that – scientifically and historically – Genesis is simply wrong. On the other hand, a purely historical-critical style of reading the Bible would see the stories as reports of alleged actual events, but then go on simply to deny that such events actually happened. Arguably, the same is true of the assertion that the story of creation in Genesis was never meant to be taken literally, a commonplace in modern discussions of religion and science, and is picked up by the Catholic Pontifical Biblical Commission in their short book entitled The Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture: The Word that Comes from God and Speaks of God for the Salvation of the World:

The first creation account (Gen. 1: 1 – 2: 4a), through its well-organised structure, describes not how the world came into being but why and for what purpose it is as it is. In poetic style, using the imagery of his era, the author of Gen. 1 … shows that God is the origin of the cosmos and of humankind.

Inspiration and Truth, p.74.

It seems to John Barton (and to me) highly likely, however, that the original author was trying to describe how the world came into being, in other words, that the text is, or was, meant to be taken literally. The problem with this way of understanding it is that, unless you are a ‘fundamentalist’, you have to go on to admit that the author was mistaken, and this comes very hard to many conservative Christians, especially when they are dealing with what became ecclesiastical documents. The metaphorical reading of the creation story is a ‘forced’ or ‘strained’ reading, designed to ensure that the narrative can continue to be seen as true in some sense. And perhaps it is true in that sense – but it foists on the authors what some readers believe is the best way we have of extracting benefit from the passages. Such readings are not a modern undertaking, but reveal a dependence on the view that, because the text is ‘inspired’ it must be ‘true’ according to our understanding of how the world is and how it came to be. Nonetheless, there is an alternative, which is to read it at face value, and then recognise that it is not true. If we do that, then the idea that the text is inspired becomes harder to hold on to. Perhaps, as John Barton suggests, it is better not to make the high claim that it is inspired or, at least, to understand ‘inspiration’ differently. Perhaps, also, the use of the word ‘fundamentalist’ to describe ‘conservative Christians’ who read the Bible literally, is not an appropriate usage. A Christian must be able to hold to the ‘radical truth’ of the Creation myths and sagas without accepting them as historically or scientifically factual.

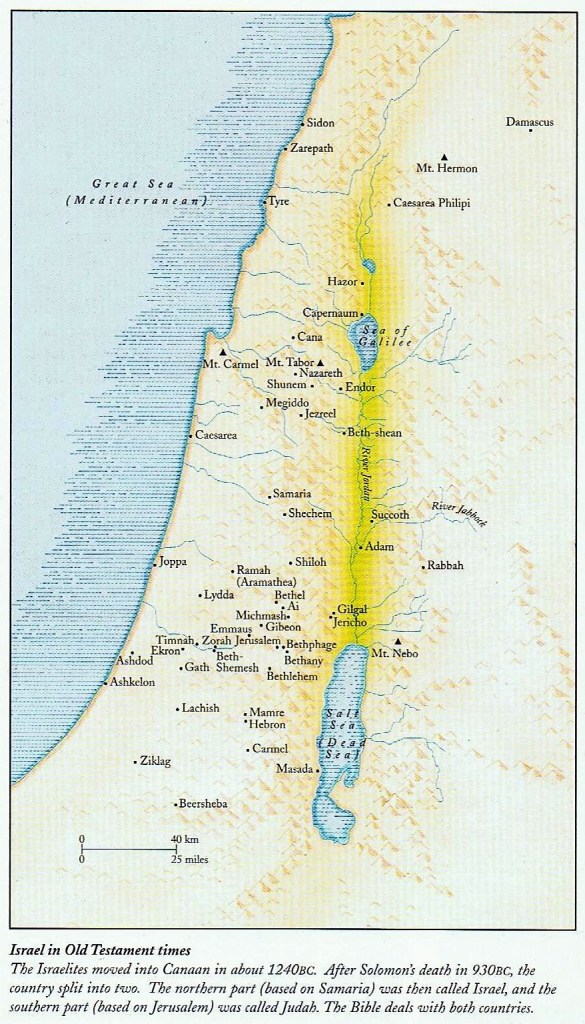

The Story of Israel, God’s ‘Chosen People’:

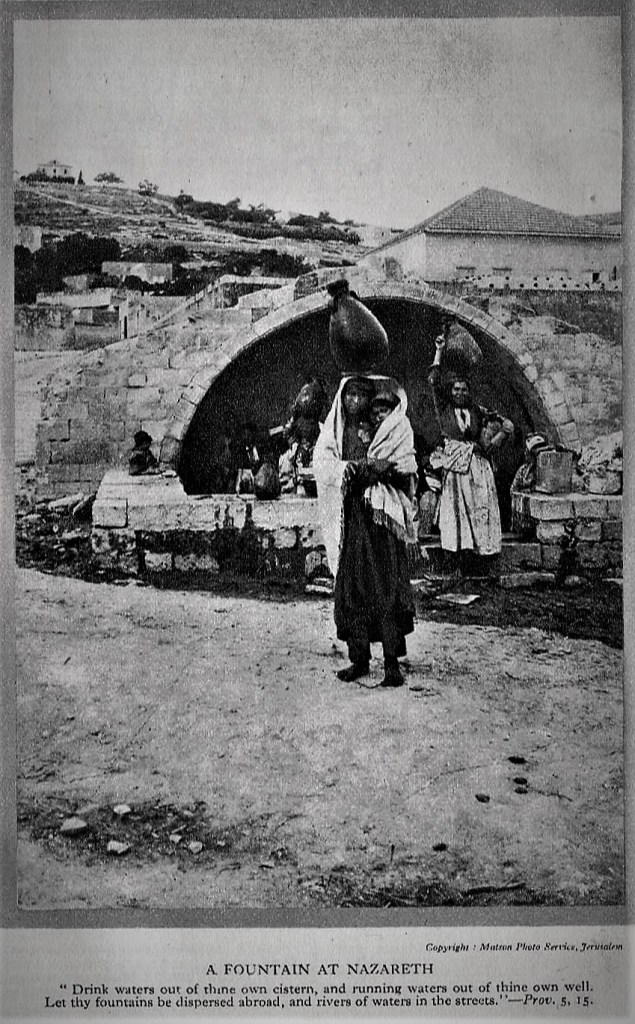

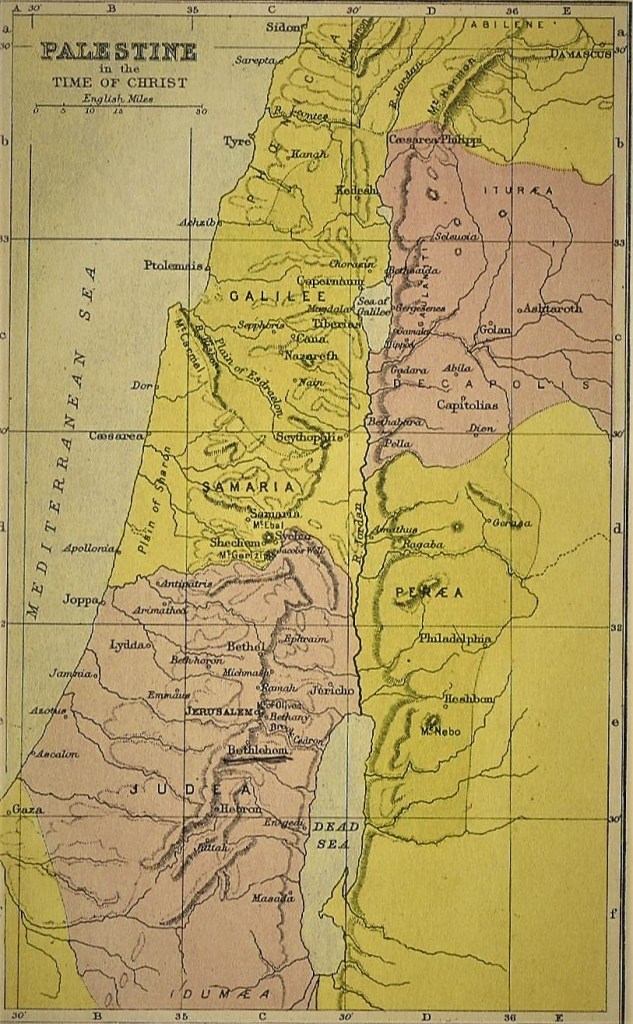

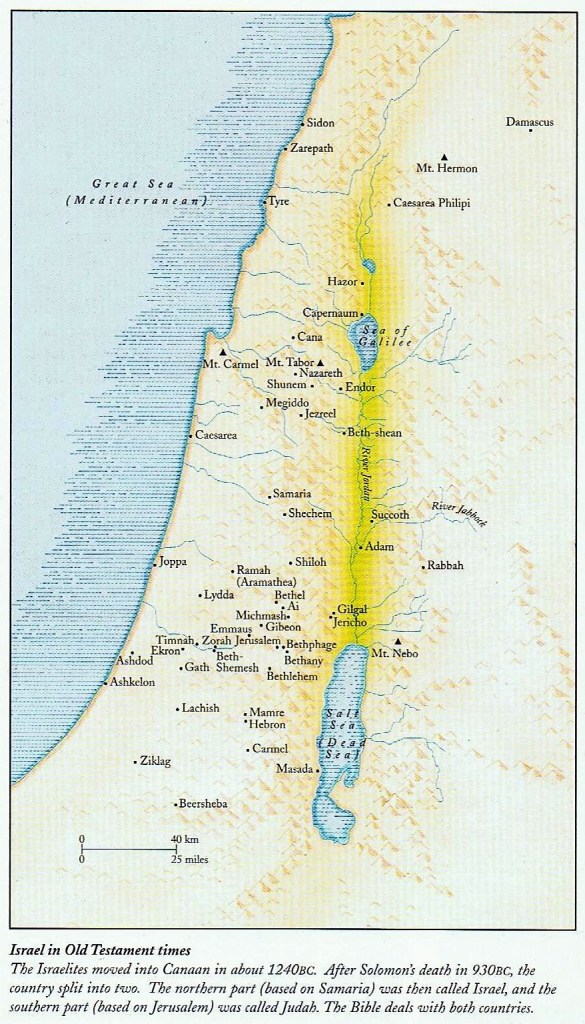

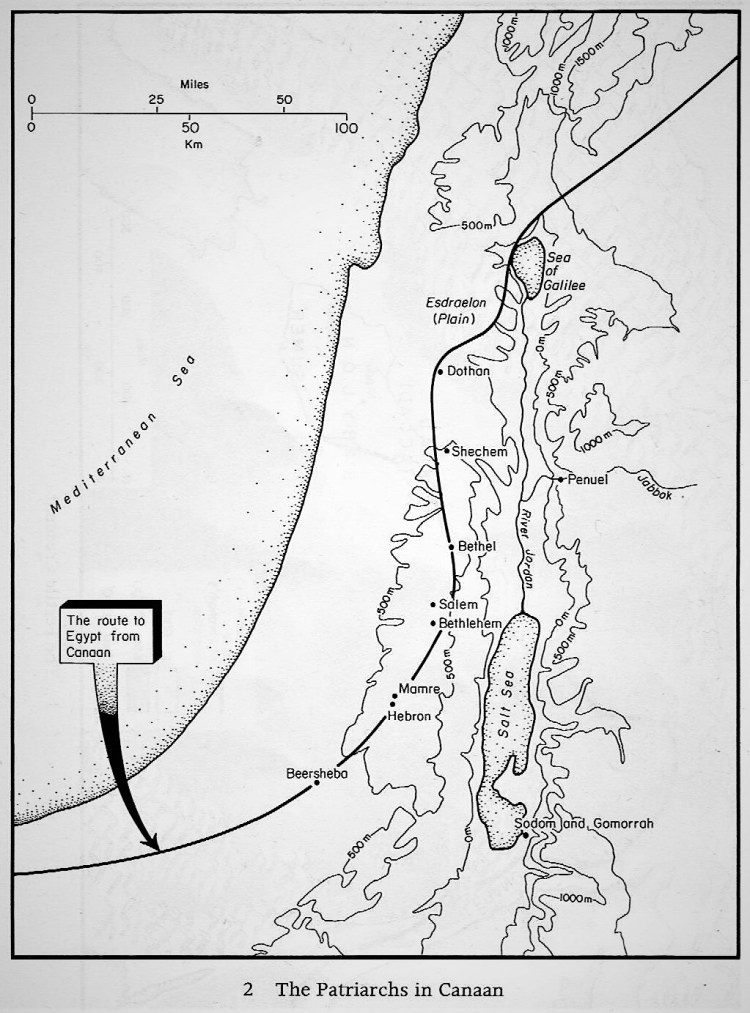

The story that Christians are still living today began as the story of Israel as the children of Abraham, Israel as God’s chosen people, chosen from the world: Israel as the light to the Gentiles, the people through whom all nations would be blessed; Israel as the Passover people, the rescued-from-slavery people, the people with whom the One God had entered into a covenant, a unique bond. There are signs all over the Jewish writings of the last two centuries before the days of Jesus and Paul and the first two centuries afterwards, that a great many Jews from widely different backgrounds saw their Bible not primarily as a compendium of rules and dogmas, but as a single great story rooted in Genesis and Exodus, in Abraham and Moses. Paul’s Bible, especially as the young Saul of Tarsus and student of Gamaliel in Jerusalem, was not primarily a set of fragments or a catalogue of books of wisdom, but a narrative rooted in creation and covenant, stretching forward into the dark unknown. Whether people read Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel, whether they followed the line of thought through the books of Kings and Chronicles, or whether they simply read the five books of Moses, the ‘Torah’, from Genesis to Deuteronomy, the message was the same: Israel was called to be different, summoned to worship the One God, but Israel had failed fundamentally and had been exiled to Babylon as a result. A covenantal separation had therefore taken place. Prophet after prophet had said so. The One God had abandoned the Jerusalem Temple to its fate at the hands of foreigners.

Wherever you look in Israel’s scriptures, the story is the same. Any Jew from the Babylonian exile onward who read the first three chapters of Genesis would see at a glance the essential Jewish story: humans were placed in a garden; they disobeyed instructions and were thrown out. And any Jew who read the last ten chapters of Deuteronomy would see it spelt out graphically: worship the One God and do what he says, and the promised garden is yours; worship other Gods and you face exile.

A great many Jews around the time of Paul read the texts that way too; they believed that the exile was not yet over. Deuteronomy spoke to them of the coming of a great restoration (Deut. 30). The third chapter of Paul’s letter to the Galatians outflanked the eager Torah loyalism of the Jerusalem zealots and their cousins in the diaspora. At the end of Deuteronomy, Moses himself leaves Israel with the warning of a curse, culminating in exile, just as it had for Adam and Eve in Genesis 3. Moses’s Torah was, according to Paul, given by God for a vital purpose, but that purpose was temporary, to cover the period before the fulfilment of the promise to Abraham. Since this had already happened, the Torah had no more to say on the subject. All those who belong to the Messiah, Paul now claimed, are the true ‘seed’ of Abraham, guaranteed to inherit the promise of the kingdom, of new creation. Abraham believed God and, as Genesis records, it was counted to him for righteousness (15: 6, as quoted in Galatians 3: 6). God had fulfilled his promises to Abraham, but this did not drive a wedge between ‘holy Jews’ and ‘wicked Gentiles’, as far as Paul was concerned. Instead, God was establishing a family of faith of both Jews and Gentiles, as he had always intended.

Abraham’s faith, trust and loyalty was his ‘covenant badge’. A covenant, Paul attested, to which the One God had been faithful in the events of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, in which all who believed in “the one who raised from the dead Jesus our Lord” were now full members. Now, therefore, the loyal faith by which a Jew or Gentile reaches out to grasp the promise, believing “in the God who raises the dead,” would be the one and only badge of membership in Abraham’s family. Membership could not be bestowed by circumcision or by following the law, both of which post-dated the Abrahamic covenant by centuries anyway, but only by a fresh act of God’s grace, received by faith. The early chapters of Romans were written to highlight the grace and faithfulness of God, not to explain how sinful humans might be saved, and the Lutheran doctrine of ‘justification by faith alone’ needs to be understood in the context of the challenges facing the people of the new covenant in general and the first-century Roman church in particular. As Paul expounded to both Jews and Greeks across Greece and Asia Minor, the point of being part of Abraham’s family was that the call of Abraham was the divine response to the sin of Adam. The covenant with Abraham is God’s promise that he will deal once and for all with that sin and the death that it brings in its wake. That is what Paul sets out in the first four chapters of Romans, enabling a natural transition in the next four chapters to his teaching about the challenges facing the church at the time of writing to it, with chapter 8 providing the response to the problem of human sin, which could not be mitigated simply by adherence to the Law.

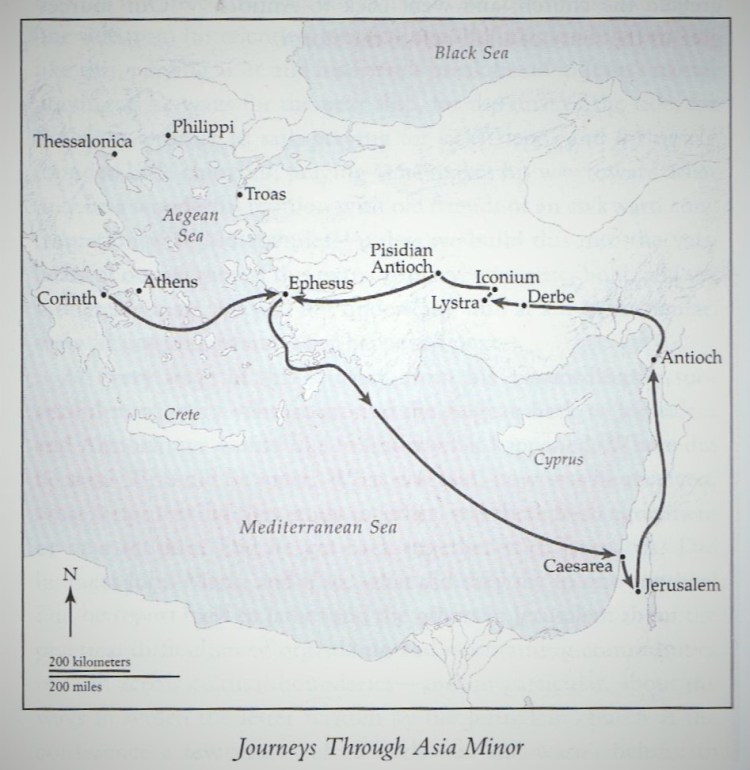

But if the Messiah had been crucified and raised, then the question of what being a ‘loyal Jew’ actually meant had been radically redrawn. It now meant following the pattern of crucifixion and resurrection, reflecting the pattern of Israel’s scriptures. It meant discovering the deep truth of baptism “in the Messiah”, as a member of his extended and multicultural family, and that what was true of the Messiah, crucifixion and resurrection, was true of oneself: calculate yourselves as being dead to sin, he says to those in the churches, and alive to God in the Messiah, Jesus (Rom. 6:11). What was true of them, was now true of them, and they must live accordingly. They have already been raised to life “in him”; they will one day be raised bodily by his spirit; therefore, their entire life must be lived in this light. This takes faith, in all its usual senses, and when that faith is present, it is, in fact, indistinguishable from loyalty to the Messiah, loyalty to the One God through him. By the end of the second century, these Jesus-followers were doing things that really did transform the wider society. Paul had planted these seeds, and though he died long before most of them began to sprout, but when they did, a community came into being that that challenged the ancient world with a fresh vision and possibility. The vision was of a society in which each worked for all and all worked for each. The possibility was that of escaping the crushing entrail of the older paganism and its social, cultural and political practises and finding instead a new kind of community, a koinőnia, a “fellowship” or ‘family’. According to the definition of ‘radical’ we looked at the top of this article, the word ‘fundamentalist’ should be a synonym of the word ‘radical’, since those who take a radical view of the Bible surely believe in its fundamental truth, once its layers of mythology have been understood, penetrated and peeled away. The light of the Creator God of Genesis is the same light as Paul experiences as ‘shining from the face of Jesus’.

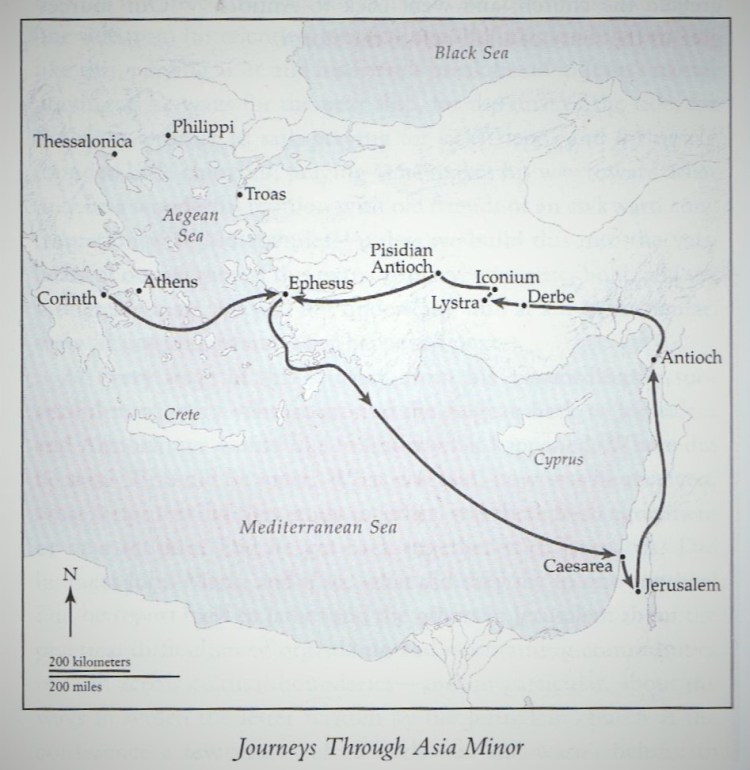

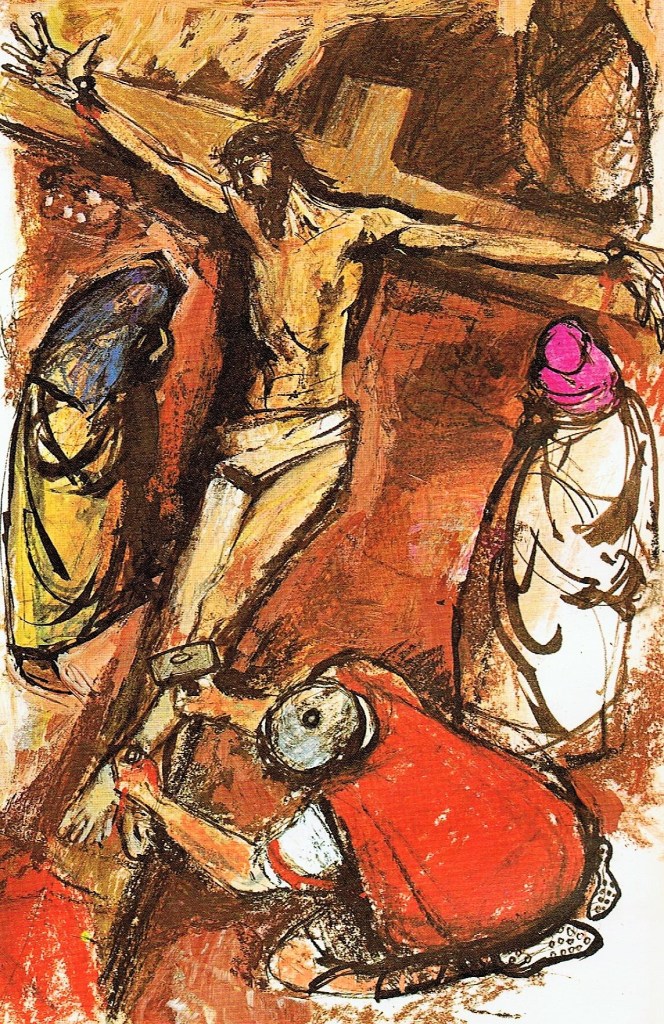

As he constantly wrote in his letters, for the ‘apostle’ this was an experience in which everybody everywhere could share, from the highlands of Anatolia (Galatia) across Asia Minor to the Aegean ports (like Ephesus) and on to Greece. When he was describing this new experience, he always went back to the stories of Jesus, remembering how he lived and how he died. For Paul, it was the way Jesus died which made real what God’s love was like, a love which, in his own words, was ‘broad and long and high and deep’; it was the way God had raised him from the dead that shows us how great the power of God’s love is. The very word ‘cross’ sounded differently. To any Roman citizen, it could only sound a savage word – like our ‘gallows’ or ‘firing-squad’. It was the way Romans executed foreign criminals or rebels or slaves. But now it was the symbol of God’s ‘amazing love’ and he even wrote that he would ‘boast’ about it. It was also the means by which Jesus ends our hostility:

Remember that you were at that time separated from Christ, alienated from the commonwealth of Israel, and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world. But now in Jesus Christ, you who were once far off have been brought near in the blood of Christ.

For he is our peace, who has made us both one, and has broken down the dividing wall of hostility, by abolishing in his flesh the law of commandments and ordinances, that he might create in himself one new man in place of the two, so making peace, and might reconcile us both to God in one body through the cross, thereby bringing the hostility to an end.

And he came and preached peace to you who were far off and peace to those who were near, for through him we both have access in one Spirit to the Father.

Ephesians 2: 12-18.

A New Covenant – Redemption, Reconciliation and Resurrection:

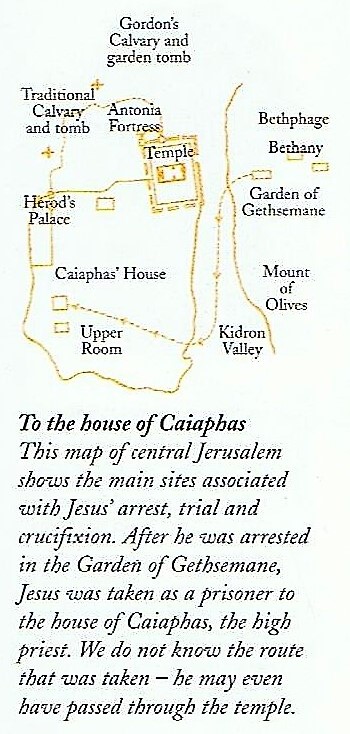

In chapter 27 (v 51) of Matthew’s Gospel, we are told that, when Jesus had ‘breathed his last’, the curtain hanging in the Temple was torn in two from top to bottom, meaning that there was no longer to be any division in the salvation narrative between the priesthood and the people of God and, as Paul tells us, between Jews and Gentiles, slaves and free men, men and women. The old Covenant had been replaced by a new one. Paul told the Galatians that if you all belong to Christ, then you are the descendants of Abraham and will receive what God has promised. In today’s language, that should also have a radical impact on Christians. Living in God’s way means that we can’t talk about one another as being ‘white’, ‘black’ or ‘coloured’, ‘working-class’ or ‘upper-class’, or of men being superior to women, as though these labels are all that matters. What really matters is that we are all grown-up members of God’s Family, as God promised to make us. And, as sons and daughters inherit their father’s wealth, so all the wealth of God, our Father, is ours to share.

What Jesus had made plain for Paul was that God was someone we could trust and to whom we could pray as ‘Father’. Here Paul used the very word that Jesus used in his own prayers – ‘Abba’. There is nothing we need to fear, not even death itself, for death ‘has been totally defeated’. The whole world and whatever may lie beyond it is the world of God our Father. Therefore, because we are made in His image, we should not act from our own selfish interests, but in humility and in the interests of others. In his letter to the Philippians, Paul points to the need for Christians to follow the example of Jesus in this respect:

Have this mind among yourselves, which you have in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient to unto death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name which is above every name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth, and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

Philippians 2: 3-11 (RSV)

Paul was familiar with the elaborate ritual of sacrifice laid down in the Law of Moses, and in his time still practised in the Temple in Jerusalem, as well as in the pagan rituals of the Greek states. This is the background of what he says about the work of Christ: God designed him to be the means of expiating sin by his sacrificial death (Rom. 3: 25). When Paul speaks of the blood of Christ, he is using it as a metaphor for the idea of sacrifice, but he makes no suggestion, either here or elsewhere, that Christ offered himself as a sacrifice to ‘propitiate’ an offended deity. In using the metaphor Paul is declaring that the self-sacrifice of Christ meant the release of moral power which penetrates the deepest recesses of the human spirit, purifying our souls. In the following passage which is perhaps the clearest and most succinct statement of his teaching on justification, redemption and sacrifice, Paul writes:

From first to last this is the work of God. He has reconciled mankind to himself through Christ … What I mean is that God was in Christ reconciling the world to himself, no longer holding their misdeeds against them.

II Corinthians 5: 18f.

In the concept of ‘reconciliation’, Paul’s thought has passed out of the realm of mere metaphor and adopted the language of actual human relations. All people know something of what it means to be ‘alienated’ or ‘estranged’ – from their environment, from their fellows from the mores and values of their societies, and sometimes, from themselves. The deepest form of alienation is from our Creator, out of which comes the distortion of all our relationships. Paul tells us that God has acted in Jesus to reconcile us to himself. We need no longer be strangers to him since his attitude towards all his creatures remains, as it always has been, one of unqualified goodwill, out of which he has provided the means to reconciliation. Of outstanding significance in all this are the facts of Jesus’ death and resurrection; that he gave his life willingly for the sake of others, and that he died under the ‘curse’ of the Law on a Roman gibbet (Gal. 3: 13). All that meant a clean break with the old order, both religious and secular. Everything that followed was to be something new and largely unexpected. Christ died, but rose again and inaugurated a new order of life, a new way of living for his followers. They were surprised by his resurrection, but it was entirely in harmony with the prophetic valuation of history as the field of the ‘mighty acts’ of God that Paul should see this as one more of those acts, the ‘fulfilment’ of all that God had purposed and promised in the entire history of Israel. That had come in the person of Jesus the Messiah, but what Paul now meant by ‘Messiah’ was something very different from any of the varied ideas extant among the Jewish messianic expectations.

One invariable trait of the Messiah in Jewish tradition was that he would be the agent of God’s final victory over his enemies, usually understood to be the pagan empires that had oppressed his chosen people. The resurrection of Jesus was the pledge of victory over all enemies of the human spirit, a victory over death which Paul personifies as ‘the last enemy.’ (1 Cor. 15: 26). We now live in a world where victory has been won in one single, decisive engagement. As Paul exclaims, ‘He gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.’ (1 Cor. 15: 27). It was, and is, a victory won on the battlefield of human history, but that does not mean that Jesus was just one more ‘great man’ thrown up by historical processes. On the contrary, his coming into the world to live a truly human life, ‘born of a woman, born under the Law’, was at the same time a fresh incursion of the Creator into his creation. God, who at the beginning said, ‘Let there be Light’, has now given the light of the revelation of the glory of God in the face of Jesus (II Cor. 4: 6). Paul says that the ‘Wisdom of God’, active and visible in creation, is also manifest among men as the flawless mirror of the active power of God and the image of his goodness (Wisdom of Solomon 7: 26). So Christ himself, says Paul, is ‘the image of the invisible God.’ (Col. 1: 15).

Yet, for many people today the word ‘resurrection’ is meaningless. They find the very idea of resurrection not only difficult but incredible. We need to remember that it was never easy or credible; that’s why Jesus’s friends were taken by surprise. For Jewish people the whole story of an executed criminal who was raised by God to life was a ‘stumbling block’, an obstacle that prevented them from taking the story of Jesus seriously. For educated people in the world outside Palestine and the eastern Mediterranean, it was just ‘rubbish’. Even there, some Christians couldn’t fully understand what it meant, so those in Corinth and Rome found it even more difficult to fathom the concept. In his letters (1 Cor. 15: 32; II Cor. 1: 8), Paul reveals that he was driven almost to distraction by disorders in the Corinthian church. He sent members of his staff to deal with them (II Cor. 12: 17f.), but he found it necessary to interrupt his work and cross the Aegean himself (II Cor. 12: 14). His two letters to the Corinthians contain clear indications that the correspondence they represent was more extensive. They indicate vividly the problems that arose when people of widely differing national origin, religious background, education, and social position were being welded into a community by the power of a common faith, while at the same time they to come to terms with the secular society to which they also owed allegiance. These problems were threatening to split the new church into fragments, and not just in Corinth and Rome. It may also have been about the same time that the very serious trouble broke out which prompted Paul to write his fiercely controversial and eloquent letter to the Galatians. That is why the final theological chapter (15) of his first letter to Corinthians comes where it does. It is not a detached discussion tacked onto the end of the letter dealing with a difficult, distinct topic unrelated to what had gone before. It is the centre of everything. “If the Messiah wasn’t raised” he declares, “your faith is pointless, and you are still in your sins.” Unless this is at the heart of who they are, he says, their faith is in vain, “for nothing.” He goes on to explain it to them like this:

The heart of the Good News is that Jesus is not dead but alive. How then, can some people say, ‘There’s no such thing as being raised from death’? If that is so, Jesus never conquered death, there is no Good News to tell, and we’ve been living in a fool’s paradise. We’ve been telling lies about God when we said he raised Jesus from death; for he didn’t – if there’s ‘no such thing as being raised from death.’ … Jesus is just -dead. If Jesus is dead and has not been raised to life again, all we’ve lived for as friends of Jesus is just an empty dream, and we’re just where we were, helpless to do anything about the evil in our hearts and in the world. And those who have died as friends of Jesus have now found out the bitter truth. If all we’ve got is a story about Jesus inspiring us just to live this life better, we of all men are most to be pitied. …

I Corinthians 15: 12-56 (Dale’s paraphrase).

But the resurrection of Jesus means that a new world has opened up, so that “in the Lord … the work you’re doing will not be worthless.” The resurrection is the ultimate answer to the nagging question of whether one’s life and work have been ‘in vain’. He goes on to explain how resurrection is not a strange, supernatural event, but part of God’s plan for his entire creation:

Take the seed the farmers sows – it must die before it can grow. The seed he sows is only bare grain; it is nothing like the plant he’ll see at harvest-time. This is the way God has created the world of nature; every kind of seed grows grows up into its own kind of plant – its new body. This is true of the world of animals, too, where there is a great variety of life; humans, animals, birds, fish – all different from one another.

This shows us how to think about this matter of ‘being raised from death’. There’s the life humans live on earth – that has its own splendour; and there’s the life humans live when they are ‘raised from death’ and live (as we say) ‘in heaven’ – and this world beyond our earthly world has its own different splendour. The splendour of the sun and the splendour of the moon and the splendour of the stars differ from one another -even the stars differ in splendour.

So it is when humans are ‘raised from death.’ Here the body is a ‘physical’ body; there it is raised a ‘spiritual’ body. Here everything grows old and decays; there it is raised in a form which neither grows old nor decays. Here the human body can suffer shame and shock; there it is raised in splendour. Here it is weak; there it is full of vigour. This is the meaning of the words in the Bible, ‘Death has been totally defeated.’ For the fact is Jesus was raised to life. God be thanked, we can now live victoriously because of what he has done.

I Corinthians 15: 12-56 (Dale’s paraphrase).

Paul & The New Creation:

So, for Paul and for the early Christian fellowships, this is God the Father’s world in spite of all that could happen in it, which Paul listed as suffering, hardship, cruelty, hunger, homelessness, danger, war. In a real sense, it was a new world in the making, and what Jesus had made clear is that they were called to be God’s fellow workers in its making. With this teaching, we uncover the ‘roots’ of Paul’s entire public career. The chapter on the resurrection is not simply the underlying reasoning behind the whole letter. It is fundamental to everything that Paul believed. It is the reason that he became an apostle in the first place. The Messiah’s resurrection has constituted him as the world’s true Lord, its rightful ruler, and he has to go on ruling until ‘he has put all his enemies under his feet.’ Victory has already been won over the dark powers of sin and death that have crippled the world and, with it, the humans who were supposed to be God’s image-bearers in the world. This victory will, at last, be completed when death itself is destroyed. For Paul, learning to be a follower of Jesus the Messiah, to live within the great biblical story now culminating in Jesus and the spirit, was all about having the mind and heart, the imagination and understanding transformed, so that it made sense to live in this ‘already but not yet’ world: The Messiah has already been raised; all the Messiah’s people will be raised at his “royal arrival”. Christian living, loving, praying, celebrating, suffering, and not least ministry, all make sense within this eschatological framework. That was the main message Paul wished to impart to the Corinthians. He sent much the same message to the church at Colossae:

Realise who you really are. The Messiah died and was raised; you are in him therefore, you have died and have been raised, and you must learn to live accordingly. The day is coming when the new creation, at present hidden, will be unveiled, and the king, the Messiah, will be revealed in glory. When that happens, the person you are in him will be revealed as well. Believe it, and live accordingly.

Colossians 3: 1-4 (Tom Wright, The New Testament for Everyone, 2011)

The pastoral guidance that follows, emphasising sexual purity; wise, kind and truthful speech; unity across cultural boundaries, is similar to that given to the Romans. In his Epistle to them, Paul emphasised how their baptism symbolised their own bodies being buried and raised from death:

Do you not know that all of us who have been baptised into Christ Jesus were baptised into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life. …

Let not sin therefore reign in your mortal bodies, to make you obey their passions. … yield yourselves to God as men who have been brought from death to life, …

Romans 6: 3-4, 12-13 (RSV).

When he wrote his first letter to Corinth, Paul still expected the return of Jesus within his lifetime, and with it the resurrection of the dead. But by the time of his second letter to the Corinthians, he is now facing the prospect that he may die before all this happens. This was anticipated in his letter to the Philippians, and it is now built into his thinking, no doubt because he had “received the death sentence” in Ephesus. But his view of the future for the Christian communities had not changed; what had shifted was his view of where he might fit into that future. The coming resurrection, however, with all that it would entail, is the platform on which Paul places one of his most characteristic statements his ministry:

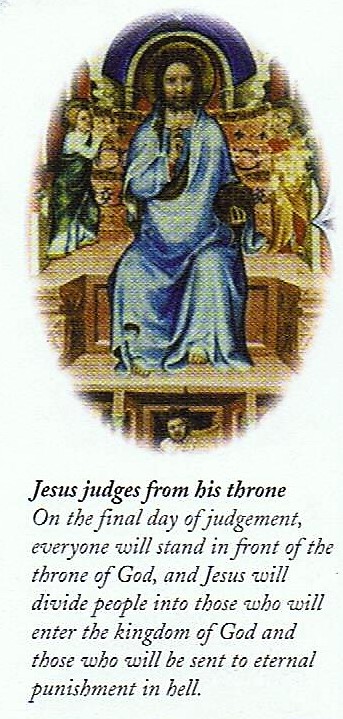

We must all appear before the judgement seat of the Messiah, so that each may receive what has been done through the body, whether good or bad. So we know the fear of the Lord and that’s why we are persuading people … For the Messiah’s love makes us press on. We have come to the conviction that one died for all, and therefore all died. And he died for all in order that those who live should no longer live for themselves, but for him who died and was raised on their behalf. … thus, if anyone is in the Messiah, there is a new creation! Old things have gone, and look – everything is has become new! It all comes from God. He reconciled us to himself through the Messiah, and he gave us the ministry of reconciliation.

2 Corinthians 5: 11-18 (Wright).

If we accept the story of Jesus, we suddenly become aware of what our job is as believers. We are ministers of reconciliation. We take our place in the world’s work with everybody else – as engineers, teachers, shopkeepers, shorthand typists, farmers, nurses, doctors, managers, shop-stewards. But we are also members of God’s Family and God’s fellow workers. We look with new eyes at the world around us – the village or town or city where we live and our place in it – and at the world, we read or hear about in the media. And it is not just what happens in this world that matters, since it is, for Christians, just an exciting beginning. But it is not enough for them to simply wait for new heavens and a new earth in which righteousness dwells (II Peter 3: 13). Paul’s letters give clear pastoral guidance to individual Christians, largely quoting from or echoing Jesus’ teaching as to how to behave towards others, both fellow-believers and non-believers, paraphrased as follows: be sincere and straightforward; give your heart to everything that is good; look forward to God’s new world with gladness; never forget to pray; bless those who treat you badly, don’t curse them; share other people’s happiness and their sadness; respect everyone; mix with ordinary people; don’t talk as if you know all the answers; don’t injure anybody just because they have injured you; as far as you can, be friends with everybody; never try to get your own back, leave that in God’s hands; if your enemy is hungry, give him food, if he is thirsty, give him drink (by doing this, you will make him ashamed of himself); don’t be beaten by evil, beat evil by doing good (Romans 12: 9-21). In Colossians, Paul gives more guidance as to how the fellowship as a whole should follow God’s Way:

Care for people. Be kind and gentle and never think about yourself. Stand up to everything. Put up with people’s wounding ways; when you have real cause to complain, don’t – forgive them. … God’s forgiveness of you is the measure of the forgiveness you must show to others.

It is love like the love of Jesus that makes all these things possible, holding everything in the grip and never stopping halfway. Master every situation with the quietness of heart that Jesus gives us. This is how you were meant to live; not each by himself, but together in company with all the friends of Jesus. … Here is real wisdom, in the light of which you can help one another, deepening one another’s understanding and warning one another, if need be.

How full of songs your hearts will be, full of songs of joy and praise and love, songs to God himself! In this spirit you can take everything in your stride, matching word and deed, as the friends of the Lord Jesus. Make him the centre of your life, and with his help let your hearts be filled with thankfulness to God – your Father.

Colossians 3: 12-17 (RSV).

Here, Paul emphasises that we can only achieve his kingdom on earth if we act together, in company with all the friends of Jesus, the local and worldwide Church. Above all we must match our words with deeds, putting individual faith into the collective action of the Church. As the letter of James reminds us, ‘faith without works is dead.’ Paul had first encountered the risen Christ in the community of his followers. The voice he heard on the road to Damascus had announced the identity of Jesus in the context of the persecuted church (Acts 9: 5; 22: 8; 26: 14). It is not surprising, therefore, that he was led to understand the work of Christ and his own mission to the Gentiles, in terms of ‘church planting and nurturing the communities that had arisen out of that work. This was a new historical phenomenon that needed to be brought into a relationship with the history of Israel as the field in which the purpose of God was working itself out. This meant that, from its origins, life ‘in Christ’ could not simply be an inward and personal experience.

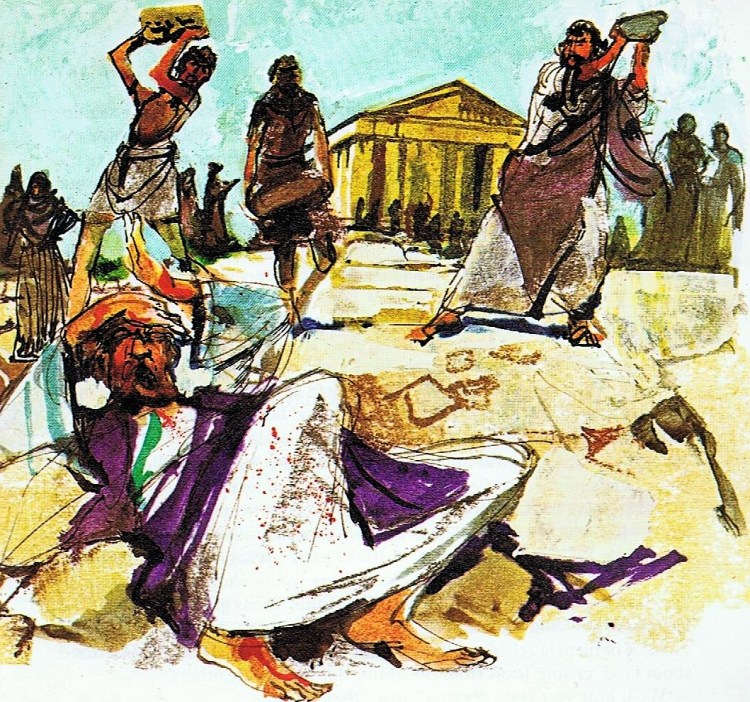

Paul also drew from it principles of fruitful application to the church as a society living in the world. The period during which he wrote his letters saw an immense ‘coral growth’ of the Christian communities. Largely through his own enterprise and that of the ‘team’ of missionaries who accompanied him on his journeys, or under his ‘direction’, the ‘network’ spread over a huge geographical area and at a surprisingly rapid pace. Almost inevitably, so rapid an expansion brought with it many problems. Apart from the tendency to factiousness endemic in Greek society, there were two distinct problems within the church itself. The first resulted from the enduring legacies of beliefs and attitudes which both Jews and pagans brought with them from their recently disavowed religious traditions. The other was that the community as a whole, spread over half a continent, naturally took time to develop an agreed body of beliefs and doctrines beyond a few very simple, fundamental convictions. In itself, it was healthy enough, especially in a Greek context, for a Christian philosophy to be hammered out through discussion and debate over the years. Paul’s intellect was as adventurous as anybody’s. But for less mature Christians, extravagance and eccentricity were not always constructive to faith-building.

Some of the practical divergences Paul attacked forcefully and in detail in his letters. These were often concerned with the continued observance of Jewish holy days and food regulations (Rom. 14) and about the extent to which they might join in the social life and festivities of their pagan neighbours without compromising the principles of their new faith (1 Cor. 8: 1-13; 10: 18-33). There was a sharp point in Paul’s cri de cour in his second letter to the Corinthians: There is the responsibility that weighs on me every day, my anxious concern for all our congregations. The difficulties at Corinth were eventually resolved and Paul, having wound up his work at Ephesus, was able to re-visit a church now fully reconciled. In the church more broadly, Paul saw people actually being drawn into unity across the barriers erected by differences of ethnicity or national tradition, language, culture, or social status. He was most powerfully impressed by the reconciliation of Jew and Gentile in the fellowship of the church (Eph. 2: 11-22). In this, as his horizons widened, he saw the promise of a larger unity, embracing all mankind (Rom. 11: 25-32). In this unity of mankind, moreover, he finds the sign and pledge of God’s purpose for his whole creation.

The Hymns of Creation of John & Paul:

The most significant attempt to describe all that Jesus means are the words in a poem that prefaces the fourth Gospel (of John). A well-known Greek word for ‘word’ or ‘reason’ or ‘wisdom’ is used to describe Jesus; he is God’s ‘Word’ to the world, God’s ‘reason’, God’s ‘wisdom’. The poem begins with words that, significantly, echo the opening of the book of Genesis, the same words that Paul used to describe his new experience of ‘God in Christ’:

At the beginning of all things – the Word.

God and the Word, God himself.

At the beginning of all things,

the Word and God.

All things became what they are

through the Word;

without the Word

nothing ever became anything.

It was the word that made everything alive;

and it was this ‘being alive’

that has been the Light by which

men have found their way.

The Light is still shining in the Darkness;

The Darkness has never put it out.

The real Light

shining on every man alive was dawning.

It was dawning on the world of men,

it was what made the world a real world,

but nobody recognised it.

The whole world was its true home,

yet men, the crown of creation, turned their backs on it.

But to those who walked by this Light,

to those who trusted it,

it gave the right to become

members of God’s Family.

These became what they were –

not because ‘they were born like that,’

not because ‘it’s human nature to live like that,’

not because men ‘chose to live like that’ –

but because God himself gave them their new life.

The Word became human

and lived a human life like ours.

We saw his splendour,

love’s splendour, real splendour.

From the richness of his life,

all of us have received endless kindness:

God showed us what his service meant through Moses;

he made his love real to us through Jesus.

Nobody has ever seen God himself;

the beloved Son,

who knows his Father’s secret thoughts,

has made him plain.

John 1: 1-18 (Dale’s paraphrase).

Genesis begins with the words ‘In the beginning’, in Hebrew a single word, bereshith. The prefix be, as a preposition, can mean ‘in’ or ‘through’ or ‘for’; the noun reshith can also mean ‘head’, ‘totality’ or ‘first fruits’. The Hymn of Creation in Genesis 1 reaches its climax with the creation of humans in the image of God. Creation as a whole is a Temple, the ‘heaven-and-earth reality’ in which God wants to dwell, and the mode of his presence in that Temple (as anyone in the ancient world would have known perfectly well) was the ‘image’, the cult object that would represent the creator to the world and vice versa, a complex concept, like creation itself or like a human being. In his epistle from Ephesus to the church in Colossae, Paul finds fresh insight from his missions into the way in which, as the focal point of creation, of wisdom and mystery, and of what it means to be human, Jesus is enthroned as Lord over all possible powers. In a moment of crisis or despair, Paul composes his own ‘Hymn of Creation’ about what it might mean to trust the God who raises the dead:

He is the image of God, the invisible one,

The firstborn of all creation.

For in him all things were created,

In the heavens and here on the earth.

Things we can see and things we cannot –

Thrones and lordships and rulers and powers –

All things were created both through him and for him.

And he is ahead, prior to all else

And in him all things hold together;

And he is supreme, the head

Over the body, the church.

He is the start of it all,

Firstborn from the realms of the dead;

So in all things he might be the chief,

For in him all the Fullness was glad to dwell,

And through him to reconcile all to himself,

Making peace through the blood of his cross,

Through him – yes, things on the earth,

And also things in the heavens.

Colossians 1: 15-20.

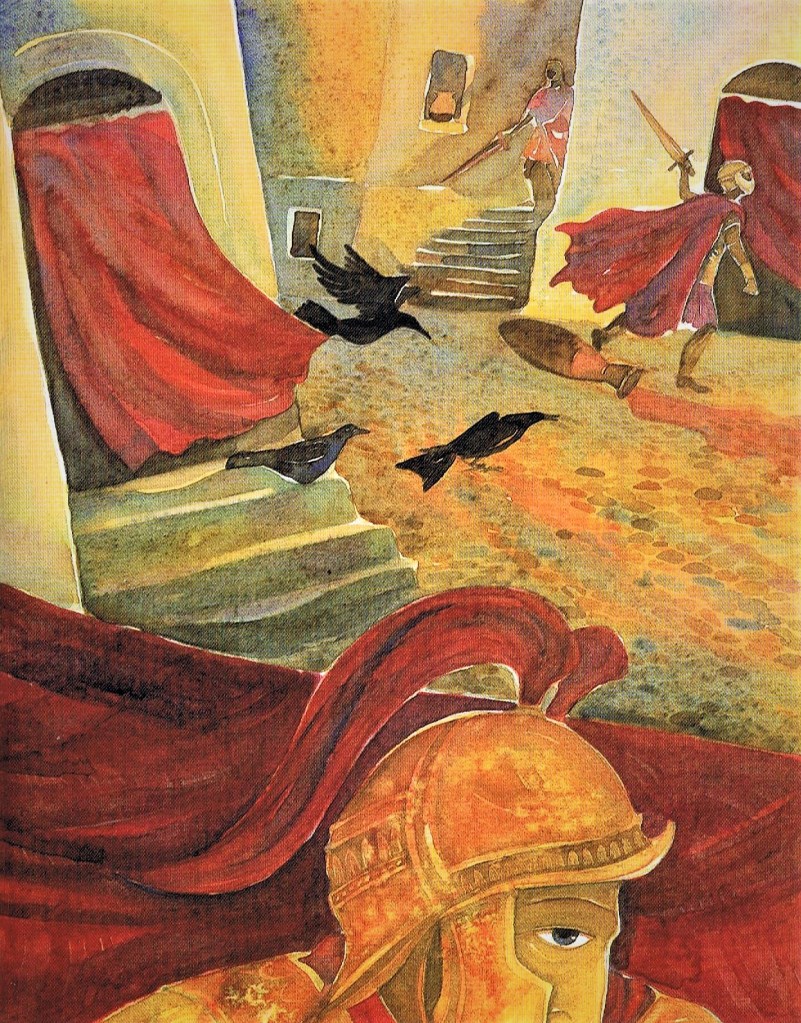

In this elegant poem, Paul is invoking and celebrating a world in which Jesus, the one through whom all things were made, is now the one through whom, by means of his crucifixion, all things are reconciled. This is not, of course, the world that he and his friends can see with the naked eye. They see local officials giving allegiance to Caesar. They see bullying magistrates, threatening officers. They see stonings and persecutions, prison and torture. But they also see the world, and the world beyond, with the eye of faith. Through that eye, they also see Jesus, the Messiah, the true son of David, the true Temple in which the full divinity of the One God was ‘glad to dwell’. The poem offers the highest view of Jesus one could have, up there with John’s simple but profound statement, quoted above: The Word became flesh, and lived among us. He is the one whose shameful death on the cross has reconciled the whole created order to its Creator. In a passage that has much of the visionary quality of poetry or prophecy, Paul pictures the whole universe waiting in eager expectation for the day when it shall ‘enter upon the liberty and splendour of the children of God.’ (Rom. 8: 19-21). In the church, therefore, should be discerned God’s ultimate design ‘to reconcile the all things, whether on earth or in heaven, through Christ alone.’ (Col. 1: 20, cf. Eph. 1: 10). Such is the vision that Paul bequeathed to the church for its inspiration.

A Call to Global Action for the Community of Christ:

But what has happened to Paul’s vision and inspiration in the modern world? Fifty years ago, the German theologian Jűrgen Moltmann wrote of the implications of Paul’s teaching for the modern-day Church:

It is, in fact, the goal of the Church to represent that “new people of God” of whom one can say “There is …, if we may proceed with modern relevance, neither black nor white, neither Communist nor anti-Communist … for all are one in Christ Jesus.” The barriers which men erect between each other to assert themselves and humiliate others are demolished in the community of Christ since men are there affirmed in a new way: they are ‘children of freedom’. By undermining and abolishing all barriers – whether, in religion, race, education, or class – the community of Christians proves that it is the community of Christ. This could indeed become the new identifying mark of the Church in our world, that is composed, not of equal and like-minded men, but of dissimilar men, indeed even of former enemies. This would mean, on the other hand, that national churches, class churches and race churches are false churches of Christ and already heretical…

Jűrgen Moltmann (1969), Religion, Revolution, and the Future. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

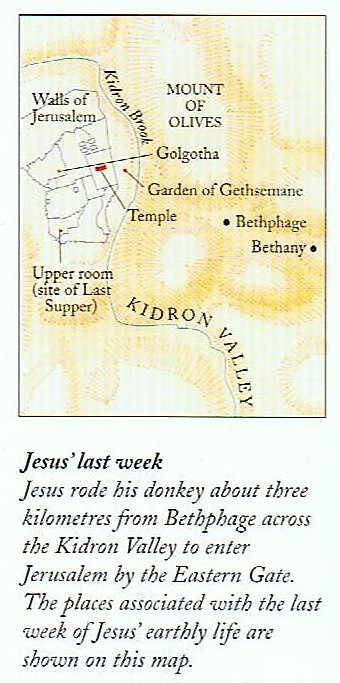

If we attempt to live according to the Scriptures, we must realise that we are being called into action. As the above extract from the Radical Bible indicates, half a century since its publication, the perspective and application of that action needs, more than ever, to be global. Most of us can do little by ourselves so that our first step of any modern-day ‘evangelist’ should be to make contact with others, people of all faiths and traditions, who are already involved in the worldwide struggle for justice and peace. The simple and beautiful stories of Jesus’s birth, ministry, death and resurrection, using the myths, legends, sagas and poems from the OT hymn-writers and prophets celebrate the conviction that Jesus fulfilled the hopes of both Jews and Gentiles, and that God, through Jesus, was speaking to the whole world.

Sources:

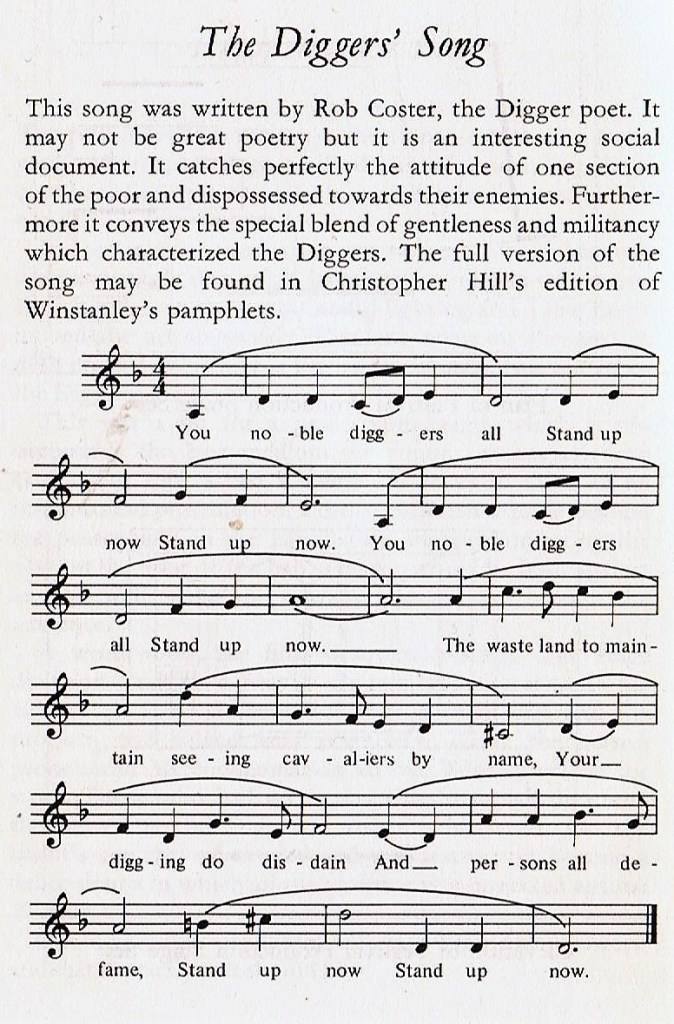

John Eagleton & Philip Scarper (ed.) (1972), The Radical Bible. New York: Spectrum Publications.

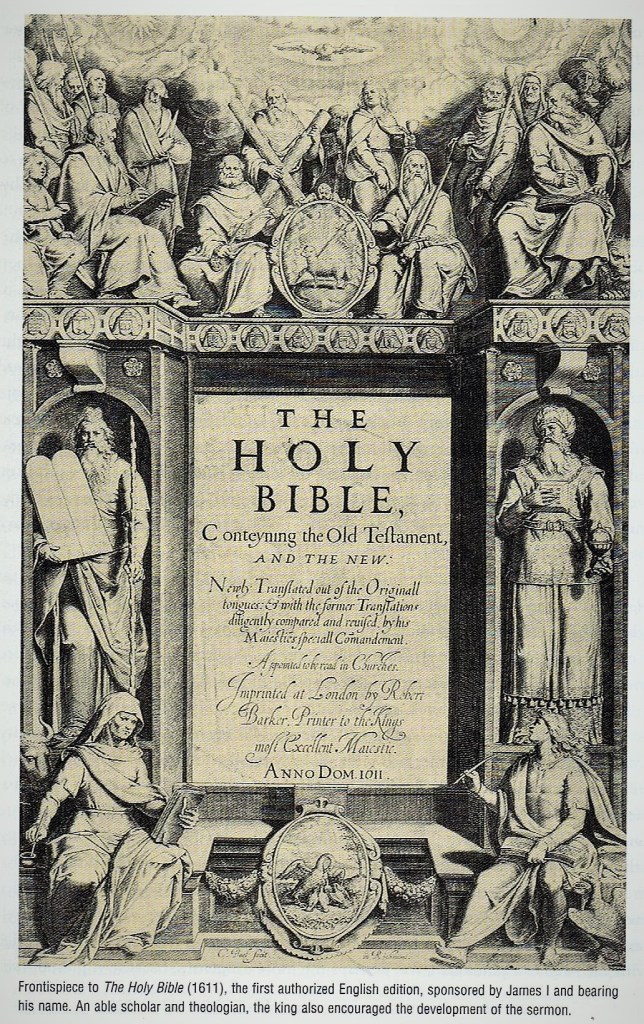

Robert C Walton (ed.) (1970, ’82), A Source Book of the Bible for Teachers. London: SCM Press.

Alan T Dale (1979), Portrait of Jesus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tom Wright (2018), Paul: A Biography. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

John Barton (2019), A History of the Bible: The Book and Its Faiths. London: Allen Lane (Penguin Books)

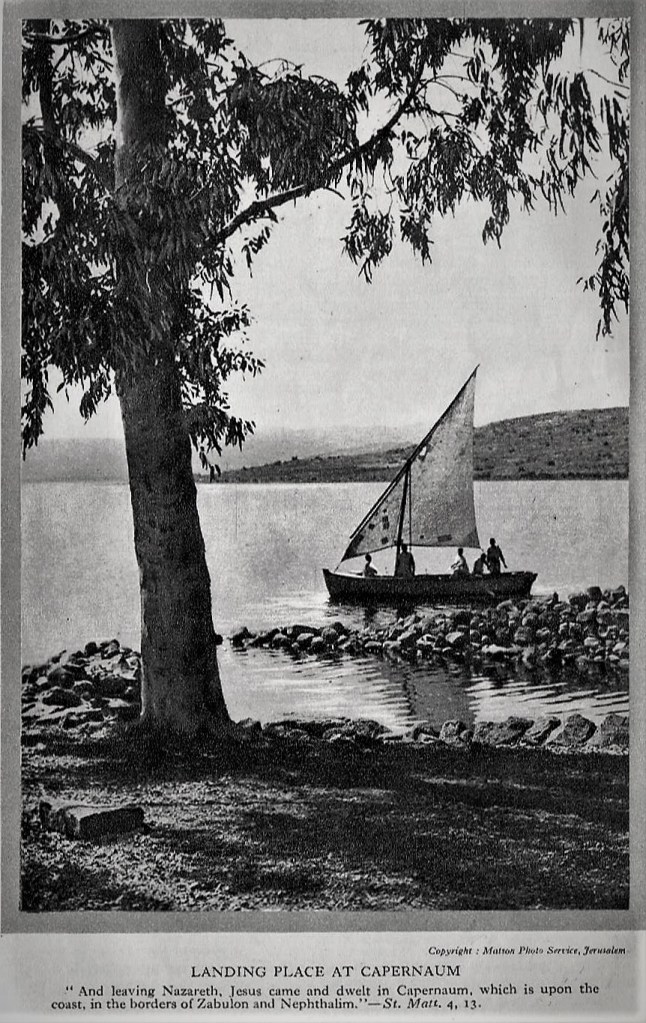

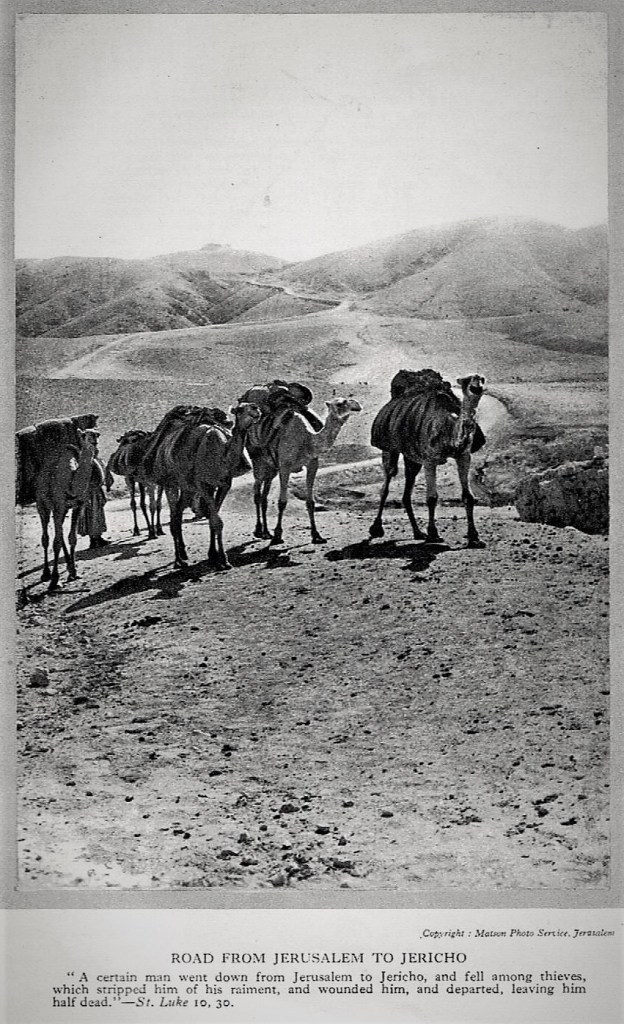

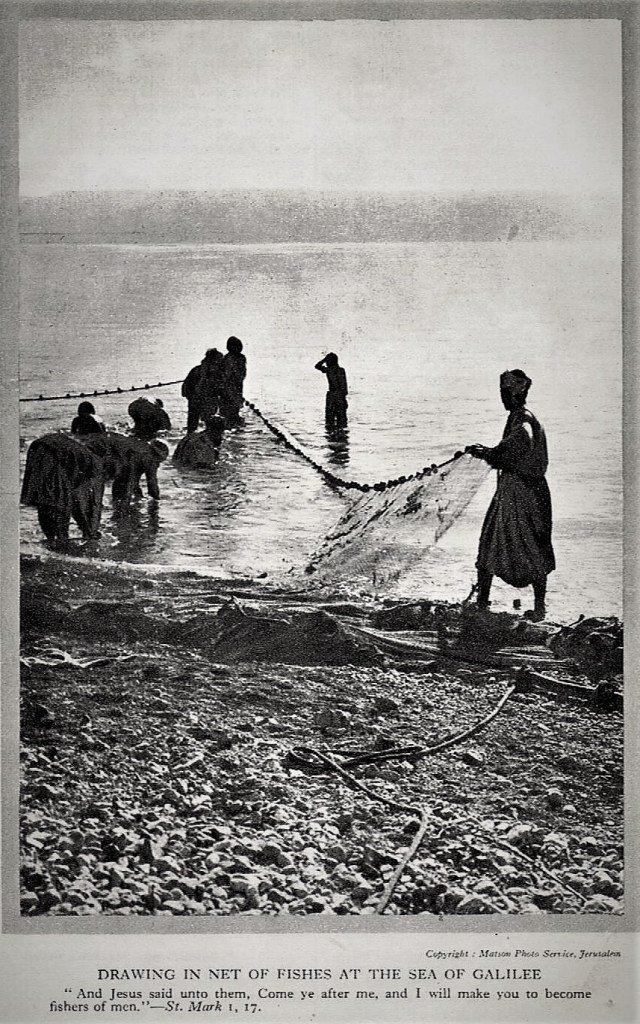

Gallery: