Includes a scene from Regent Street Baptist Church, Smethwick, Birmingham, from November 1897, ‘The Church in Meeting Assembled’ by Rev. A. J. Chandler, Minister of Bearwood Baptist Church, Birmingham, 1965-79.

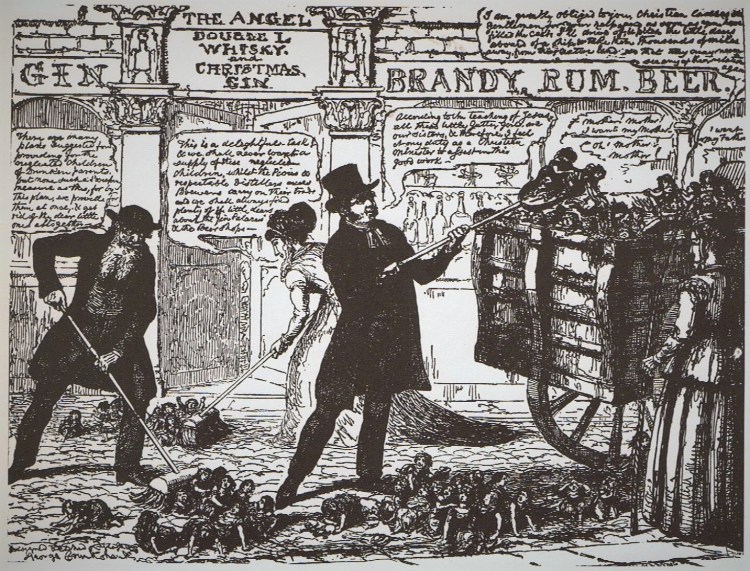

Revival, ‘Respectability’ & Reform in Britain, 1814-1859:

In 1814, there was an evangelistic revival at Redruth in Cornwall which continued for nine days. An eye-witness described what happened:

Hundreds were crying for mercy at once. Some remained in great distress of soul for one hour, some for two, some six, some nine, twelve and fifteen hours before the Lord spoke peace in their souls – then they would rise, extend their arms and proclaim the wonderful works of God with such energy that bystanders would be struck in a moment and fall to the ground and roar for the disquieture of their souls.

By 1826, a complete change had come over the social habits of Britain, or so many contemporary witnesses have told us in their diaries, journals and letters. In that year, one writer wrote of the courtesy of the people of Petticoat Lane in London. He walked there with his wife without hearing or seeing anything objectionable. Fifteen years earlier he had been blackguarded from one end of the lane to the other. But not everything was not a marker of progress and moral improvement. The cult of respectability among the emerging business classes was not the same as real Christianity, and there was also a great deal of hypocrisy among evangelicals. Most of them observed Sunday strictly, but the Victorian evangelicals were strictest of all. The Lord Day’s Observance Society was founded in 1831. Numerous letters and articles in the evangelical magazine, The Record, protested against Sunday opening of parks, museums and zoological gardens. For six years, the evangelical minister at Cheltenham managed to prevent all passenger trains from stopping there on a Sunday.

Evangelical societies made it their business to supply Anglican evangelical ordinands and endow evangelical parishes where they might serve. The most important patronage trust was that begun by John Thornton and taken over by the Rev. Charles Simeon. When he died, the Simeon Trust had the right to nominate the clergy to twenty-one Anglican positions. These were mainly in large towns such as Bradford and Derby. By 1820, one in twenty of the Anglican clergy were evangelical; by 1830, it was one in eight. But Anglican evangelicals gained high office only slowly. Henry Ryder became Bishop of Gloucester in 1815 and Charles Richard Sumner became Bishop of Winchester in 1827, but the commanding heights of the Church were not ‘taken’ until John Bird Sumner became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1848. These three men presented a new kind of bishop. They were much simpler in their lifestyles than their predecessors. They visited all parts of their dioceses and took more care over confirmations and ordinations. Their example was followed in the fifties by the ‘Palmerston bishops’, who were mostly appointed on the advice of the evangelical, Lord Shaftesbury. The English evangelical social reformer, pictured below, supported numerous causes, including improved factory conditions for the working classes, the regulation of child and female labour and slum schools.

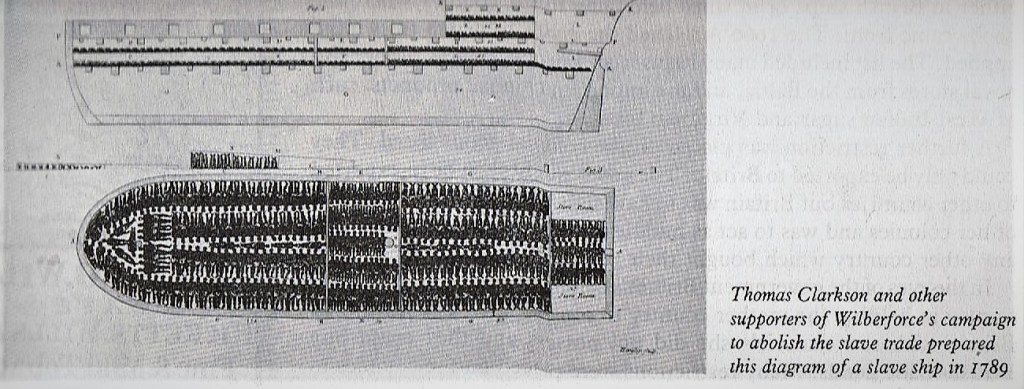

1833 not only saw the Abolition of Slavery within the British Empire, but also the first effective Factory Act passed by Parliament. It had often been suggested that Wilberforce and his associates in the Clapham Sect were only concerned with liberating black slaves overseas and not with the ‘white slaves’ of industrial England. This claim, also made ever since by some historians, ignores the fact that Wilberforce had been one of the first few reformers to complain that the ineffective Factory Acts of 1802 and 1818 did not go far enough. The specialists in the industrial problem were, however, the Yorkshire evangelicals, such as Wilberforce’s friend Thomas Gisburne, Richard Oastler of Huddersfield, Michael Sadler MP, their parliamentary spokesman, and John Wood, a Bradford textile manufacturer. Wood put the issue of ‘white slavery’ to Oastler in 1830 in terms of the ongoing campaign against Afro-Caribbean slavery:

You are very enthusiastic against slavery in the West Indies: and I assure you there are cruelties practised in our mills on little children, which, if you knew, I am sure you would strive to prevent.

A few months later, Oastler wrote a famous letter to the Leeds Mercury entitled ‘Yorkshire Slavery’ in which he represented the disappointment of his fellow northern campaigners with the lack of support received from dissenters and the more pietistic of their fellow evangelical Anglicans, who appeared content to leave the plight of the distressed working classes to the operation of so-called ‘natural laws’. Shaftesbury was also often criticised by more heavenly-minded evangelicals for being too concerned with the earthly conditions of the Victorian working classes. He had his own answer for their criticisms which he presented to a Social Service Congress held at Liverpool in 1859:

When people say we should think more of the soul and less of the body, my answer is that the same God who made the soul made the body also … I maintain that God is worshipped not only by the spiritual but the material creation. Our bodies, the temples of the Holy Ghost, ought not to be corrupted by preventable disease, degraded by avoidable filth, and disabled for his service by unnecessary suffering.

Continental Revival and Reaction, 1815-65:

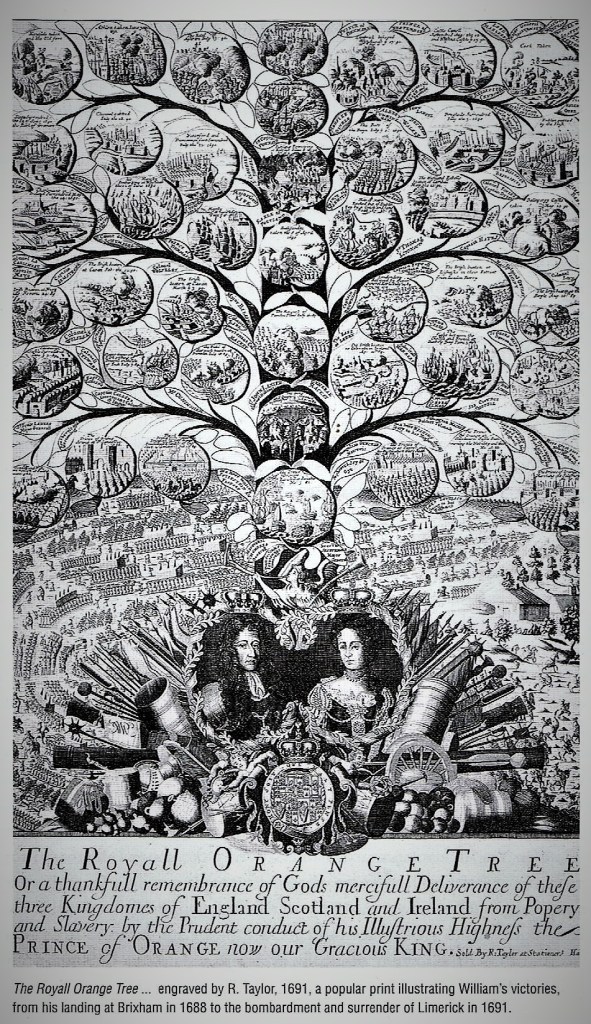

Meanwhile, following the fall of Napoleon and state-sponsored atheism, between 1815 and 1848 a series of popular religious awakenings arose throughout Protestant Europe. The awakening (Réveil) in French-speaking Europe had its origins in Geneva, in the ministry of the Scot, Robert Haldane (1764-1842), who led an early mission to French-speaking Europe in the 1820s and 30s. In 1802, Chateaubriand’s Génie du Christianisme (The Genius of Christianity) was published in France, an immensely popular and powerful argument for Christianity, based on its aesthetic values. In Denmark, Nicolai Grundvig (1783-1872) initiated a pietistic movement by openly opposing liberal theology. The revival in Sweden resulted from the ministry in Stockholm of an English preacher, George Scott. In Norway, the awakening was largely a lay movement, connected with Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771-1824). These revival movements were not closely related to each other and were largely the work of ‘ordinary’ Christians. In 1848, there were outbreaks of revolution in France, Italy, Austria-Hungary and Germany. By December, the five hundred representatives from the German kingdoms, Austria and Bohemia attending an assembly at Frankfurt to create a constitution for Germany, for the whole Empire, produced a Declaration of the Rights of the German People which included a guarantee of religious freedom for dissenters. The ‘Old Lutherans’ who had rejected the Prussian Union of 1817 with the Calvinists, were allowed freedom of conscience. Nonconformists who had appeared in Germany as a result of missionary activity from English-speaking nations also gained toleration. But these gains were, however, short-lived.

Democratic institutions made little further progress in Germany and by 1850 most republican reforms, including those of the Frankfurt Assembly, had lapsed into disuse. In 1862, political reaction and religious autocracy had returned across Europe with Pope Pius IX’s encyclical, Quanta Cura naming political liberalism as one of the chief ‘modern errors’. The Syllabus of Errors also condemned rationalism in all its forms, including liberal theology, freemasonry and religious toleration itself. Even the Bible Societies, which had entered the European continent from Britain after 1815, were ejected. In 1816, Pius VII had rebuked the Societies for distributing the Scriptures without the comments of the church ‘Fathers’. In the 1830s, Pope Gregory XVI further condemned them as daring heralds of infidelity and heresy. So the Syllabus simply consolidated earlier opposition. The pope also issued a strong attack on the separation of church and state, fearing the continued strength of republicanism in France. In response, the French state prohibited the publication of the Syllabus of Errors in 1865.

Evangelical ranks in Britain divided from the 1820s, partly in reaction to developments on the continent. Edward Irving convinced many evangelicals that they were far too optimistic about the conversion of the world; in fact, the day of judgement was at hand. Christ’s second coming would precede the millennium. He believed that the missionary societies were deceiving the elect by talking of the conversion of the world. At the same time the Calvinist, Robert Haldane, won his campaign against Simeon to prevent the Apocrypha from being included in Bibles published by the Bible Society. Haldane’s nephew, Alexander, shared his uncle’s views. When the younger Haldane became the chief owner of the twice-weekly Record in 1828, he propagated these strong ideas. Haldane gave strict Calvinism a foothold again in Anglican Evangelicalism. The Record also adopted Irving’s views on biblical philosophy and the millennium, its policy becoming ultra-conservative in both politics and theology. Its strongest condemnation was for Sabbath-breakers and Roman Catholics, but ‘the Recordites’ also became a strident minority within the Evangelical party. ‘The mainstream party’ continued the tradition of Simeon and the Clapham Sect. Among their leaders were Edward Bickersteth, Henry Venn and J. W. Cunningham. Their journal, which stressed loyalty to the church, was the monthly Christian Observer, which had begun in 1802. In spite of theological differences, however, there was no open rift with ‘the Recordites’.

Missionary Societies, Colonies and Imperial Trade:

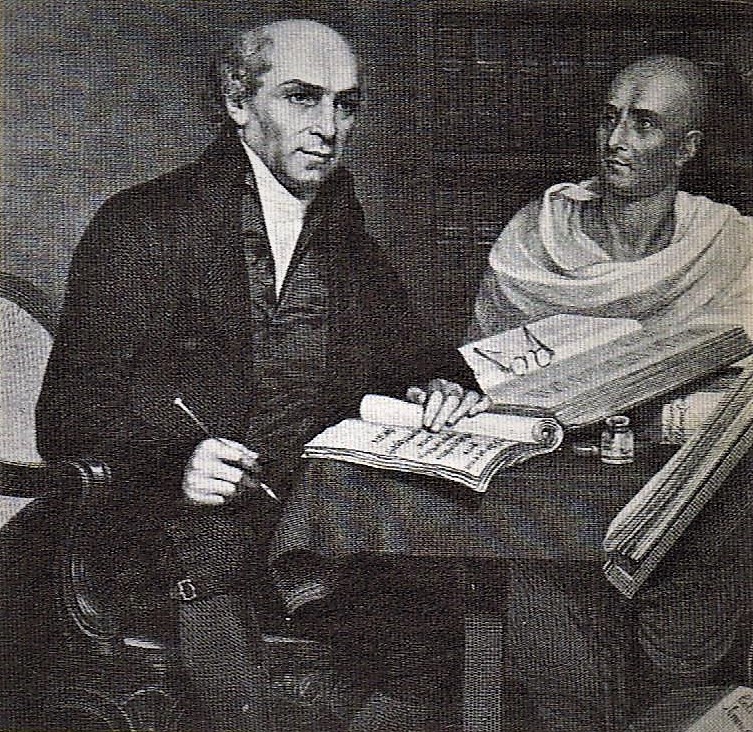

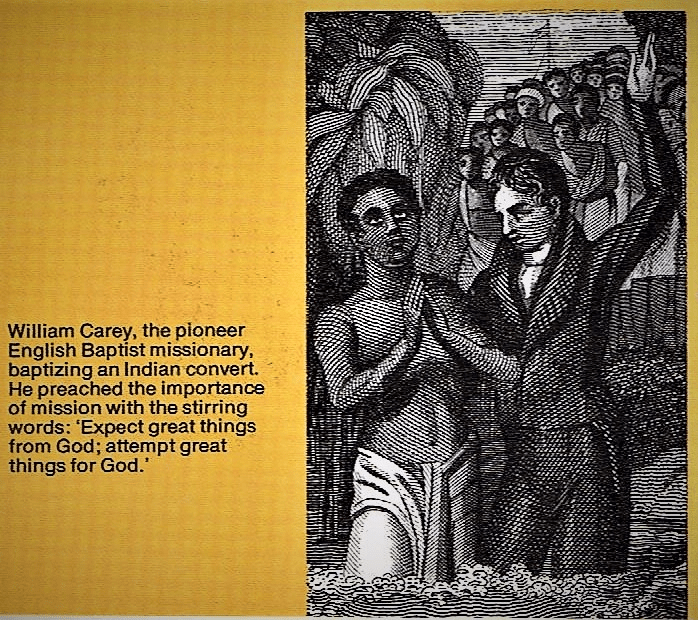

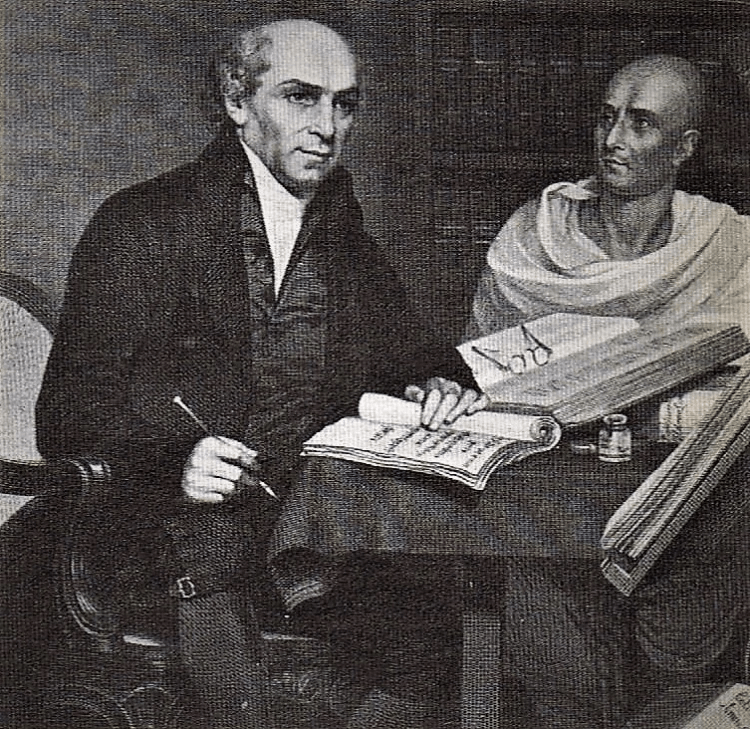

William Carey (1761-1834) achieved much in various areas during his time in India, including Bible translation and production, evangelism, church planting, education and medical relief, as well as social reform and linguistic and horticultural research. More specifically, he initiated mission schools, conceived the idea of Serampore College, founded the Agricultural Society of India (1820) to promote agricultural improvements, studied botany (being awarded a fellowship of the Linnaean Society in 1823), and took a leading part in the campaign for the abolition of widow-burning (sati), which succeeded in 1829.

Carey’s devotion to India, which he never left, and his practical wisdom in his encouraging Indians to spread the gospel themselves. In this respect, he defined his chief object as follows:

“… the forming of our native bethren to usefulness, fostering every kind of genius, and cherishing every gift and grace in them; in this respect we can scarcely be too lavish in our attention to their improvement. It is only by means of native preachers (that) we can hope for the universal spread of the Gospel through this immense continent.”

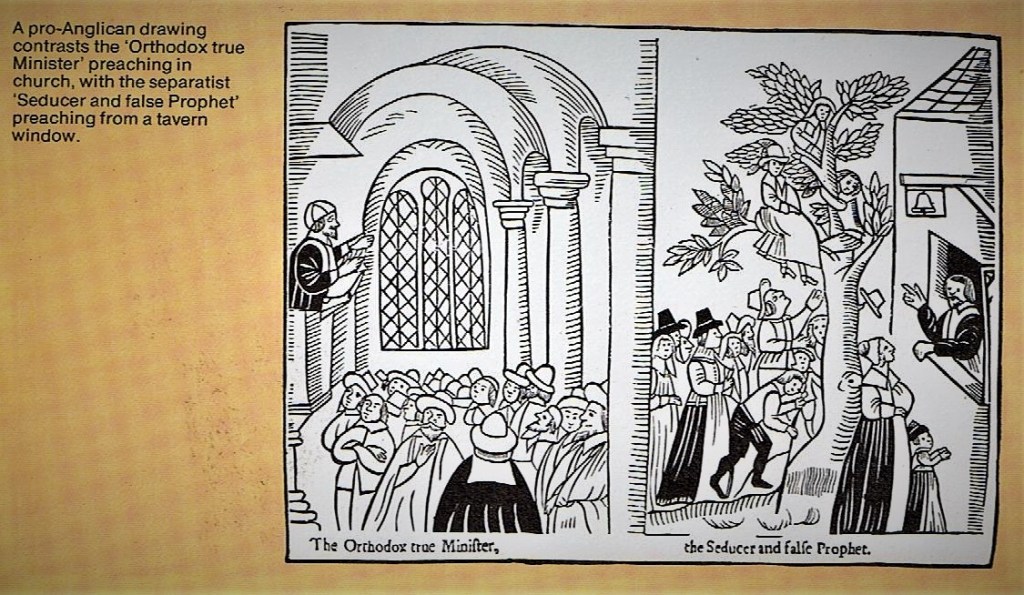

The Evangelical Revival had revolutionised preaching and its objectives. Churchmen regarded the parish priest’s task as nurturing all the baptised members of the parochial church and could not easily adjust to the thought of preaching in tribal and nomadic societies. At the same, Calvinists with a rigid doctrine of predestination and ‘the Elect’ saw no reason to concern themselves with the conversion of the heathens. When God wanted to convert them, Carey was told by a fellow Baptist, he would do it without your help or mine! But the evangelical felt a personal responsibility to do this and saw no difference between the ‘baptised heathen’ in Britain and non-Christians overseas. But it was only in the 1820s and 1830s that interest in overseas missions become a regular feature of British church life generally. This was due partly to the success of the Evangelicals in influencing British life. Many of the values of the evangelicals were adopted outside their own circles. In particular, the idea of Britain as a Christian nation with a global mission took root. Bishoprics were established in India, though none had ever been established in colonial America, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel enlarged its operations to those of a general missionary society. In Scotland, moderate presbyterian churchmen joined with evangelicals to promote missions, strongly educational in character, under the umbrella of The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.

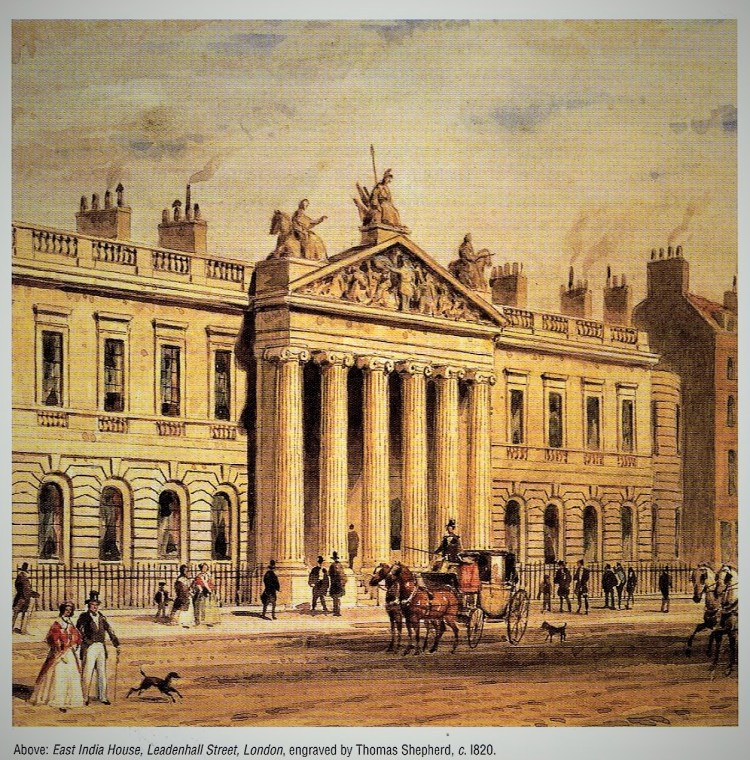

The birth of the missionary societies, however, had nothing to do with the protection of British trading interests abroad. The earliest missions were in fact intricately associated with evangelical Baptists and supported by people with known revolutionary instincts and sympathies, such as Robert Haldane, the Genevan-based Scot. It was also the evangelical groups who led the continuing campaign against slavery in the British Empire. This caused some in the Anglican establishment to fear that they were basically subversive. To this was added the fear that in India, missionary preaching would offend Hindus and Muslims, upsetting a volatile colonial relationship and harming British trade. The semi-official Honourable East India Company, through which British administration and trade were exercised, was not initially favourably disposed towards Carey and his colleagues, so much so that the missionaries had to sail in a Danish ship and work from Danish territory. The antithetical attitude of the East India Company changed when in 1813 the Company’s charter came up for renewal, and the Evangelicals of the Clapham Sect denounced some aspects of its policy. Not only did the Company hinder missionary work, they argued, it positively profited by means of a tax on native temples and similar institutions of idolatry. They won a qualified victory through the abandonment of the tax, the appointment of bishops, and the enlargement of the system of government chaplains. Missions were largely unhindered and often favoured, though nineteenth-century evangelicals soon stopped asking for ‘official’ backing for them.

When planning his first missionary enterprise, Carey had asked: what would a trading company do? From this, he proposed the formation of a company of serious laymen and ministers with a committee to collect and sift information, and to find funds and suitable men. The voluntary society, of which the missionary society was one early form, was to transform the nineteenth-century church. It was invented to meet needs rather than simply to propagate doctrines, but in doing so it undermined all the established forms of church government. In the first place, it made possible ecumenical activity. Churchmen and dissenters or seceders cut off from church business could work together for defined purposes. It also altered the power base in the church, by encouraging lay leadership among ordinary members who came to hold key positions in important societies, the best of which made it possible for many people to participate. The enthusiast who collected a penny a week from members of his local missionary society and distributed the missionary magazine was fully involved in the work of the society. It was through the work of such people that missionary candidates came forward. The American missionary, Rufus Anderson, put their achievements in dramatic context when he wrote in 1834:

It was not until the present century that that the evangelical churches of Christendom were ever really organised with a view to the conversion of the world.

Within Wesleyan Methodism, Thomas Coke was anxious to extend Methodist missions on a worldwide scale and tried several times to get the Methodist Conference to approve his plans for an extension. The objections were mainly financial, so Coke worked towards forming local auxiliaries and by 1814 these were recognised by the Conference. In 1818 it brought together the auxiliaries in a Methodist Missionary Society. Eventually, every member of the Methodist Church was automatically enrolled in the Society. In Scotland, the Kirk took direct responsibility for missions in 1824 and appointed its first missionary, Alexander Duff. By that time evangelicals and moderates agreed on the importance of this work, with its emphasis on education, which became the hallmark of successive Scottish missions. When the Kirk was split by the ‘Disruption’ in 1843, the missionaries all joined the Free Church and the Church of Scotland had to begin again recruiting missionaries. The founding fathers of the early British societies clearly did not expect many missionary recruits from among ministers – or the normal sources of supply of ministers. Carey, a self-educated cobbler turned minister, was an exception. Most of the early recruits were craftsmen or tradesmen, who would be unlikely to seek or obtain ordination for the home ministry.

The first few years’ experiences of the London Missionary Society (LMS) showed the importance of the careful preparation of missionaries. Though many of the candidates had little formal education, their training, superintended by David Bogue, was impressive. Much of the early LMS study material on languages and tribes is strikingly scholarly. There was little appetite in the first half of the nineteenth century for the acquisition of new territories and in the 1840s there were pressures and plans to abandon as many as possible of such expensive luxuries. The missionaries also played an important role in the eventual emancipation of the slaves within the British Empire, which did not come about until 1833, after a long campaign led by Fowell Buxton.

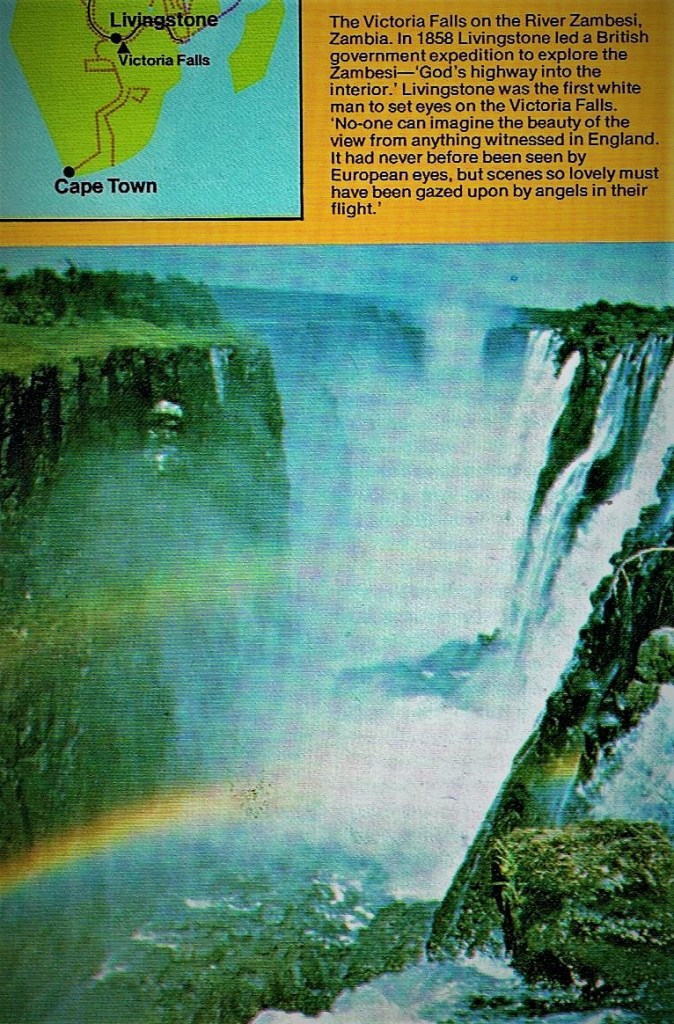

Buxton was aided by direct eye-witness accounts from the missionaries as to how slavery continued to dehumanise the lives of Africans, Afro-Caribbeans and Afro-Americans. Even after Abolition, the missionary societies also argued that Britain owed a debt to Africa for slavery and to India for the wealth derived from it. From 1841 to 1856, the Scottish doctor, independent missionary and explorer, David Livingstone, (1813-73) served with the LMS, exposing the horrid facts of the Arab slave trade in central Africa. His strategy was not to exploit but to liberate and in this he contrasted sharply with Cecil Rhodes. Though a missionary for only half of his thirty years in Africa, Livingstone saw all his work in the context of a providential plan in which gospel preaching, the increase of knowledge and the relief of suffering were all closely connected. The Anglican Universities Mission to Central Africa owed its inspiration to this Scots Independent and after his death, the Church of Scotland and the Free Church of Scotland came together to open Central African missions which reflected his ideals and breadth of vision.

The greatest difficulties in recruiting were met by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) since their principles required the use of ordained men and very few came forward. These were eased by transcontinental collaboration with seminaries in Germany elsewhere. Of the first twenty-four CMS missionaries, seventeen were German and only three were ordained Englishmen. This imbalance was eased when the bishops became more involved with the society’s activities, and also as it became more rooted in the parishes. Following the lead of Carey and the Baptists, Indian missions continued to stimulate the British missionary societies, but by the middle of the century, there was an increasing involvement in Africa.

By mid-century, the importance of training ‘native ministers’ was better and more widely recognised, and an increasing number were serving on the staffs of the societies. The CMS Niger Mission, begun in 1857, was staffed entirely by Africans. In the last third of the century, missionary recruitment expanded enormously. This was largely due to the effects of the 1859 Revival, the Baptist Keswick Convention and other movements. The ‘Cambridge Seven’, ex-Cambridge undergraduates who set out for China in 1885, were only the first of hundreds to follow. These decades – the period of high imperialism – not only produced many more missionaries but a different type of missionary. The same influences were at work in producing new forms of society. These maintained the voluntary society principle and were directed towards particular regions, for example, the China Inland Mission (1865) or the Qua Iboe Mission (1887).

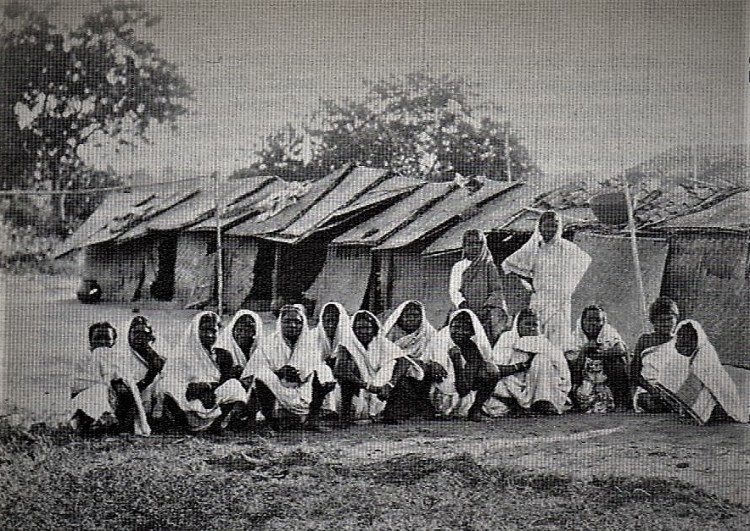

Others met particular needs, like the Mission to Lepers (1874). The photograph below shows women suffering from leprosy in a ‘mission compound’ at Champa, India in 1903.

The nineteenth-century missionaries, and the societies which called and directed them, were a major factor in transforming Christianity into a truly global religion. The number of volunteers, together with the technological and political developments of the age, led to the prospect of the evangelisation of the world in this generation. Those hopes of further Christian advancement were dashed by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and its ongoing effect on faith. But by the time European manpower was reduced, the great African and Indian native mass movements had begun.

Religious Responses to Industrialisation & Urbanisation in Britain:

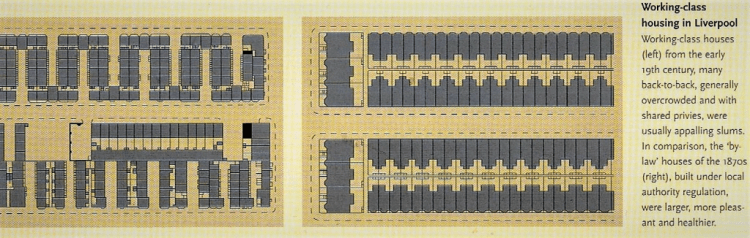

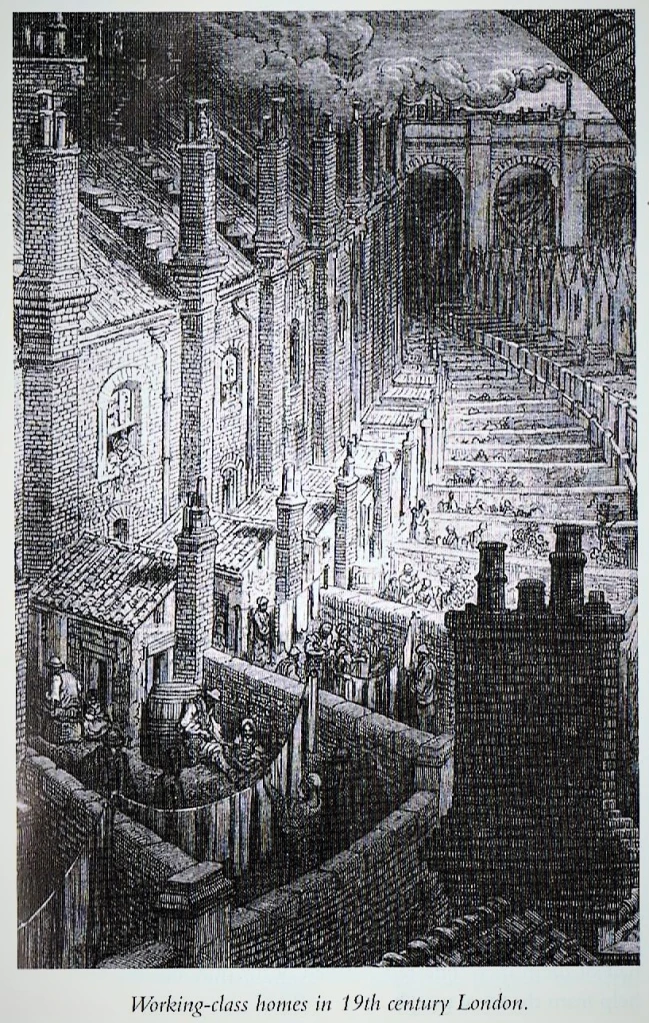

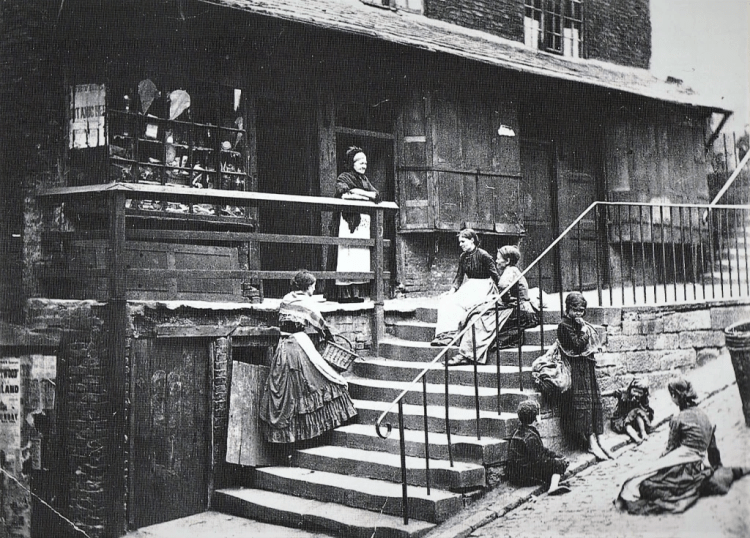

Industrialism and urbanisation strengthened the factory system which had already begun with the ‘mills’ of the north of England. It was not so much the long hours and low wages that workers objected to. They were used to these in the countryside and urban slums were not much worse than rural hovels, and agriculture depended as much on the work of women and children as the new industries. With the invention of the steam engine, the manufacturer, at last, had a source of power independent from climate and season. This was a change of universal significance and with the development of the canal systems and the railways, the limitations of location were removed from major industries. The real tyrant was the substitution of the rhythm of nature by that of the machine, for the hated threshing machines were only irregular ‘interruptions’ in rural labour. In the new urban areas, machines were a constant accompaniment to everyday life. The Church of England was particularly slow to respond to these developments, finding it difficult to do so. As the state church, it needed an act of Parliament for a new parish to be created, a process that was both time-consuming and costly.

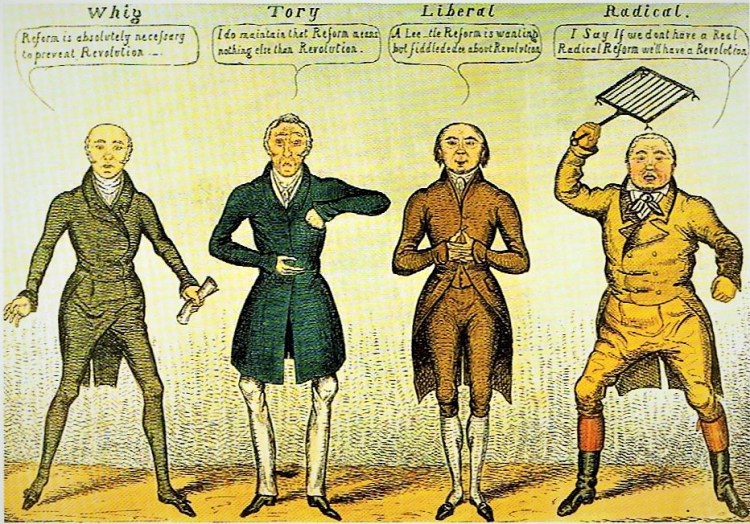

As a consequence, the Church found itself unable, at least until the 1840s, to adapt to the new industrial England and Wales. The new urban masses consequently grew up very often beyond its care: there was often simply no physical room for them in church, and all too often no clergyman to care for their spiritual needs. The parish church, in both rural and urban areas, all too often represented the Tory Party at prayer. In the 1830s, for example, the ‘Chartists’ found little support in the established church. They frequently marched on the parish churches, requesting the vicar to preach on some congenial text, such as: Go to now, ye rich men, weep and howl for your miseries which are coming to you. The rebuff they got from all the churches led them to establish separate Chartist churches in certain areas, and there was even a Chartist hymn book. Many of the Chartist leaders of the thirties and forties were Christians and church members. There is little firm evidence of the extent and class nature of church attenders in Victorian times. England’s one and only census in which church attendance was recorded took place in 1851. The deduction was made that roughly thirty per cent of those who could have attended service on Sunday did not do so. Dissenting churches were found to be approximately as strong as the Anglican churches; in fact, stronger in urban England. Church absenteeism was highest in the new northern towns.

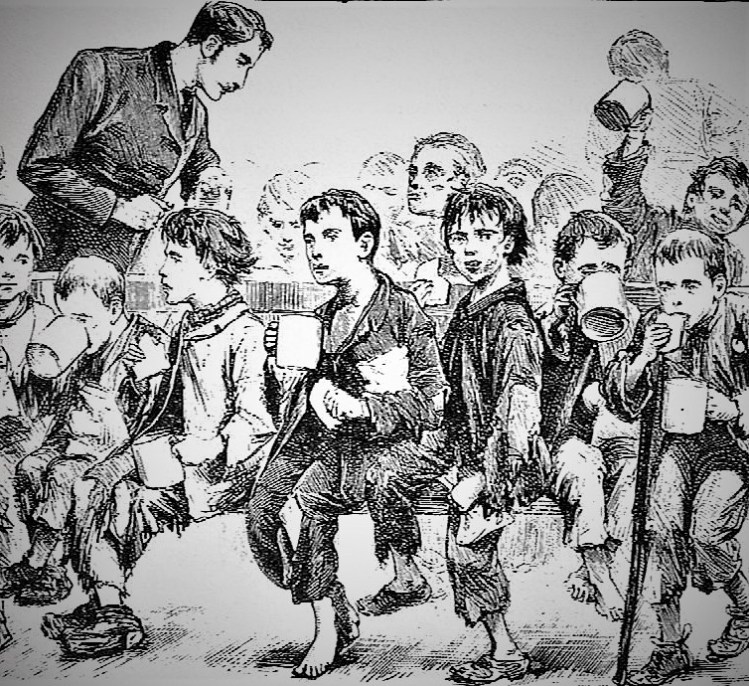

Methodism did not have the same difficulties. With its simple barn-like preaching places, its itinerant ministers, and its local preachers it was admirably designed to go where the established church was unable to go. Other Dissenters, too, expanded into the towns and cities of industrial England and engaged in missionary work there with some success. But there always remained many more people beyond, in the unchurched, unreached, jungle of ‘darkest England’ as General Booth described it. Part of the difficulty was that the churches were dominated by class divisions. Many congregations became middle-class preserves – the Wesleyans and Congregationalists tended to attract a middle-class attendance, while the Baptist ‘Tabernacle’ and the Primitive Methodist ‘Bethel’ were more likely to have a largely working-class congregation. The other small but influential nonconformist group was The Brethren, (or open Brethren). They had a strong emphasis on missionary work, at home and abroad, and their most distinctive characteristic is that the ministry and gifts of the church are distributed to all believers. They had few full-time pastors and their full-time evangelists travelled widely. Local churches governed themselves and were free to apply the teachings of scripture in the light of local and contemporary needs. Their founding fathers were mainly Anglican evangelicals who felt that the Evangelical Movement was not going far enough, but there were also many nonconformists among them who deplored certain features of their original churches. Their best-known social reformer was Thomas Barnado, pictured below helping to feed some of the hungry homeless boys of Victorian London. Barnado (1845-1905) set up a huge institution to care for the homeless children of England.

In the countryside, meanwhile, the Primitive Methodist lay-preacher Joseph Arch of Tysoe (depicted in a contemporary cartoon, right) established the Warwickshire Agricultural Labourers’ Union in the early 1870s. This was the first union of unskilled workers, and their local strike found support from the Nonconformist British Quarterly Review, which in 1872 expressed the view that…

… the movement which commenced a few months since in Warwickshire, and which is spreading gradually over the whole agricultural region of south and mid-England, is not unlike the first of those upheavals which occurred five centuries ago. Like that, it is an attempt to escape from… an intolerable and hopeless bondage, with the difference that… the present is an attempt to exact better terms for manual labour. Just as the poor priests of Wycliffe’s training were the agents… by whom communications were made between the various disaffected regions, so on the present occasion the ministers or preachers of those humbler sects, whose religious impulses are energetic, and perhaps sensational, have been found the national leaders of a struggle after social emancipation.

A religious revival has constantly been accompanied by an attempt to better the material conditions of those who are the objects of the impulse… A generation ago the agricultural labourer strove to arrest the operation of changes which oppressed him… by machine breaking and rick burning. Now the agricultural labourer has adopted the machinery of a trade union and a strike and has conducted his agitation in a strictly peaceful and law-abiding manner.

As legal restraints were lifted in the 1870s, it became easier for trade unions to spread to ‘unskilled’ groups, such as the agricultural workers, led by Arch, whose Warwickshire union spread quickly and grew into the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union. The growth of waterfront and related unions in the great seaports helped to change the geography of the trade union movement, although their strength ebbed and flowed with the trade cycle. In 1891, on the crest of the cycle, officially recorded trade union membership had penetrated deepest in Northumberland, Durham, industrial Lancashire, Yorkshire and Derbyshire, and South Wales. It remained at a very low ebb across the Home Counties, southwest England, the rest of Wales and most of East Anglia, despite the rise in agricultural trade unions. The same geographical pattern applied to the development of consumer cooperatives. ‘Coops’ divided profits among their members and were based on the doctrines of the mill owner Robert Owen, whose great discovery that the key to a better society was unrestrained co-operation on the part of all members for every purpose of social life. They attempted to build virtuous alternative societies based on a fair distribution of the rewards of labour, whose superiority to corrupt competitive capitalism would gradually and ultimately prevail. To raise funds for these Owenite communities, shops were established, with the surpluses going towards the next stages of cooperative manufacturing and agriculture. Wherever traditions of self-help and trade union commitment coexisted with hard-working, thrifty Nonconformity, cooperation took root.

Distant Dissenters, Morality & Social Justice:

How to evangelise among the working classes was an ongoing problem, partly because the children of working-class Christians tended to join the middle classes. There was something ‘bourgeois’ about revivalist ethics in practice; gone was the expenditure on drink; new priorities included the family, self-improvement and Sunday school attendance. So there came to be a distinction between ‘chapel working class’ and the ‘brute working class’ of the back alleys. From the 1840s onwards most city churches boasted a cluster of satellite missions in the poorer areas of the cities. These mission halls were often far more than preaching stations and provided their respective areas with a kind of all-purpose relief station, complete with clothing societies, penny banks, tontine clubs, soup kitchens and other agencies. They paralleled the many-sided activities of the institutional church of the suburbs which apparently provided a total ‘chapel culture’ for its adherents. The old Puritan concept of the covenant community gave way to a Christian presence, represented by a range of Christian societies engaged in various aspects of missionary work. In the late nineteenth century, people’s concerns broadened and many agencies of the church became more concerned to offer a social gospel than the old dogmatic one. The Christian minister was becoming a social organiser more than a pastor of the local body of Christ.

Against this ‘backdrop’, the attitudes towards the poor of the more distant and ‘conservative’ Nonconformist leaders, were well illustrated from the pens of those who patronised them, those who preached to them and from those amongst the poor who discovered in the Nonconformist pulpit a means for calling their colleagues to self-realisation. It was significant that Andrew Mearns, William Booth and Charles Booth were all Nonconformists, but Dissenters were also prone to facing accusations of espousing philanthropy divorced from a sense of social justice, and even of outright hypocrisy in their attitudes towards the poor. Sometimes large congregations gathered together in great solid temples of middle-class respectability, possessed neither the common life of the meeting-house nor the urgent need to rescue the lost. Instead, they seemed to perpetuate themselves by some self-justifying principle. Church-building programmes increased in every decade of the century, and many full churches, both in city centres and in the suburbs, were presided over by princes of the Victorian pulpit. They conveyed an impression of progress and advance was often conveyed. In fact, the churches were failing to keep pace with the expanding population.

By the end of the century, however, the factory system also demanded an emphasis on precision, scrupulous standards, the clock and the bell, and the avoidance of waste. For many of the leaders of nonconformity, especially the many employers among them, the greatest industrial sin was drunkenness, which challenged all the values of the new industrial capitalist system. A new morality was needed and this was provided by the fruits of the evangelical revival. All too easily, as Briggs and Sellers (1973) noted, the phrase ‘the Nonconformist conscience’,

… could lapse into an unlovely onslaught from a determined, Puritanical middle-class sectarianism against the drink, gambling and thriftlessness of the classes below and above it to the ignoring of the deeper social problems which afflicted the nation.

That is not to say that Nonconformity’s sympathies rested upon calculation alone. The growing call for the preaching of a ‘social gospel’ was, at least, the ‘child’ of a more positive definition of individualism, standing as a proper, practical and involved corrective to the implicit pietism of the tradition of conscientious separation. Nonconformists also felt the tensions involved in the relationship between church and evangelism. Victorian nonconformity blended Puritan churchmanship and revival evangelism. The revivalist strand was reinforced by the experience of the 1859 Revival, and later by the visits of American revivalists such as Moody and Sankey, and Torrey and Alexander. In his address published in the Congregational Year Book in 1885, Dr Joseph Parker began by envisaging a speech by one of that suffering community of ignorance, misfortunate, misery and shame who had spent a year observing the Unions, Conferences, Assemblies and Convocations held among Nonconformist ‘leaders’:

“We have had a full year among, and we cannot very well make out what you are driving at. We do not know most of the long words you use … We do not know what you are, or what you want to be at. From what we can make out you seem to know that we poor devils are going straight down to a place you call hell. … We read the inky papers which you call your ‘resolutions’ but in them, there is no word for us that is likely to do us real good. They say nothing about our real misery; nothing about our long hours, our poor pay, our wretched lodgings.”

… our evangelism is in danger of devoting itself almost exclusively to what is known as ‘the masses’. I must protest against this contraction, on the ground that it is as unjust to Christianity, as it is blind to the evidence of facts. If the city missionary … is wanted anywhere, he is specially wanted where … conscience is lulled by charity which knows nothing of sacrifice, and where political economy is made the scapegoat for oppression and robbery. …

There is only one class worse than the class known as ‘outcast London’, and that class is composed of those who ‘have lived in pleasure on the earth and been wanton’. The cry is ‘bitterer’ in many tones at the West End than at the East; … the thousand social falsehoods that mimic the airs of Piety … these seem to be distresses without alleviation, and to constitute heathenism which Christ himself might view with despair.

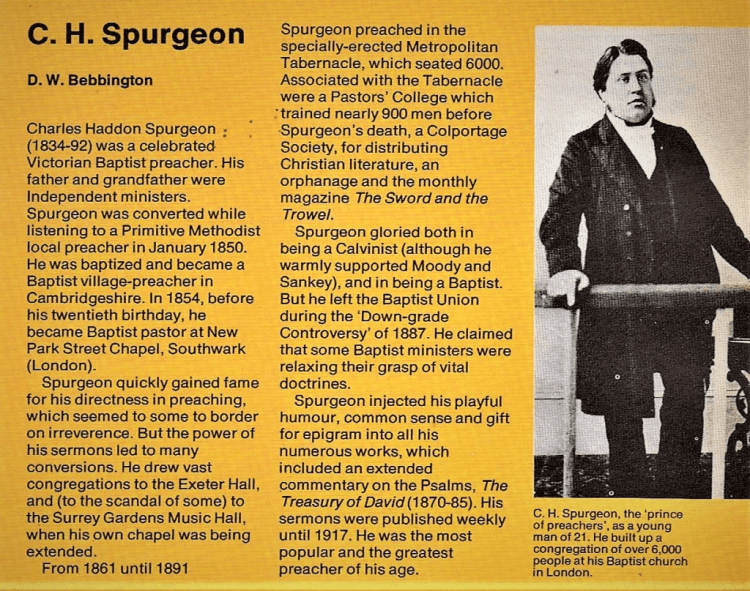

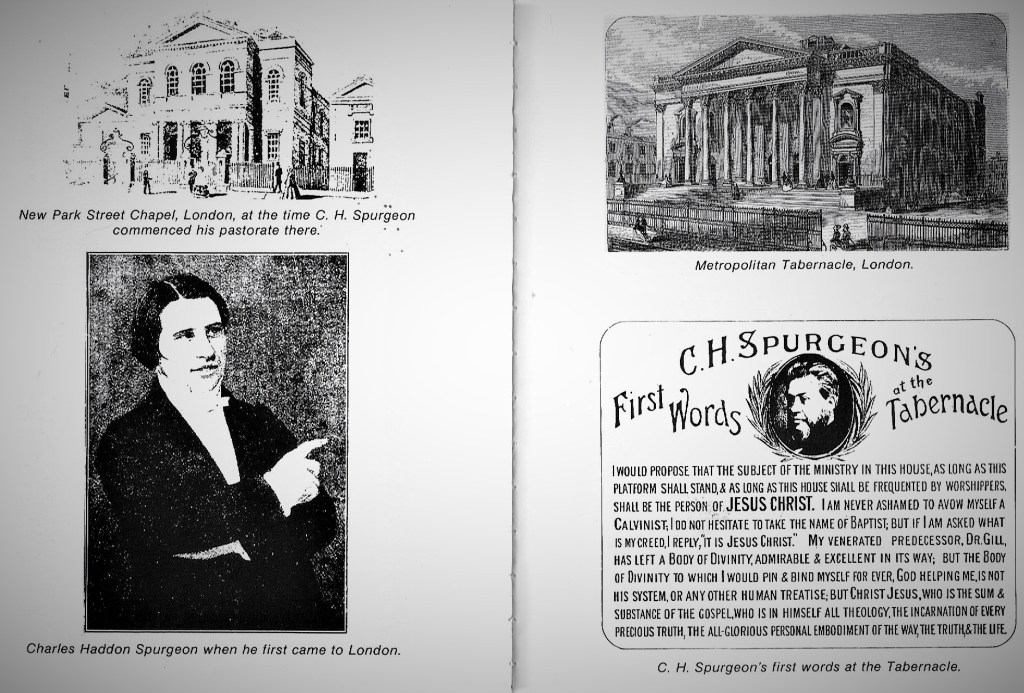

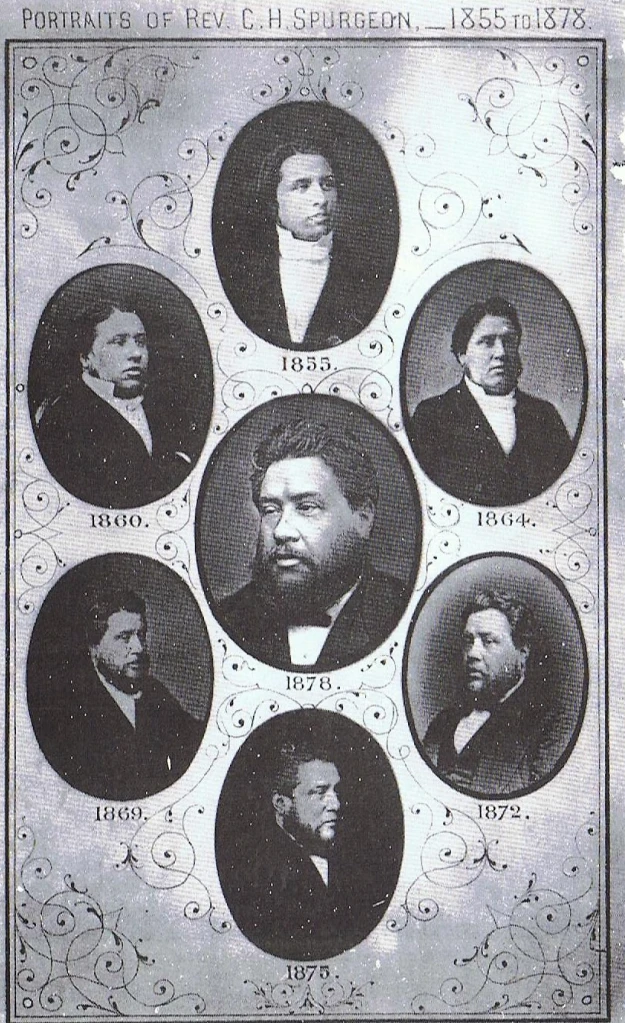

The ‘Prince of Preachers’ and the Paupers:

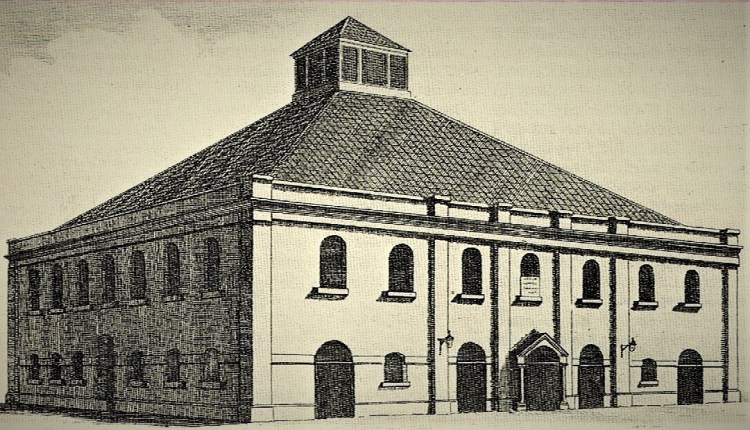

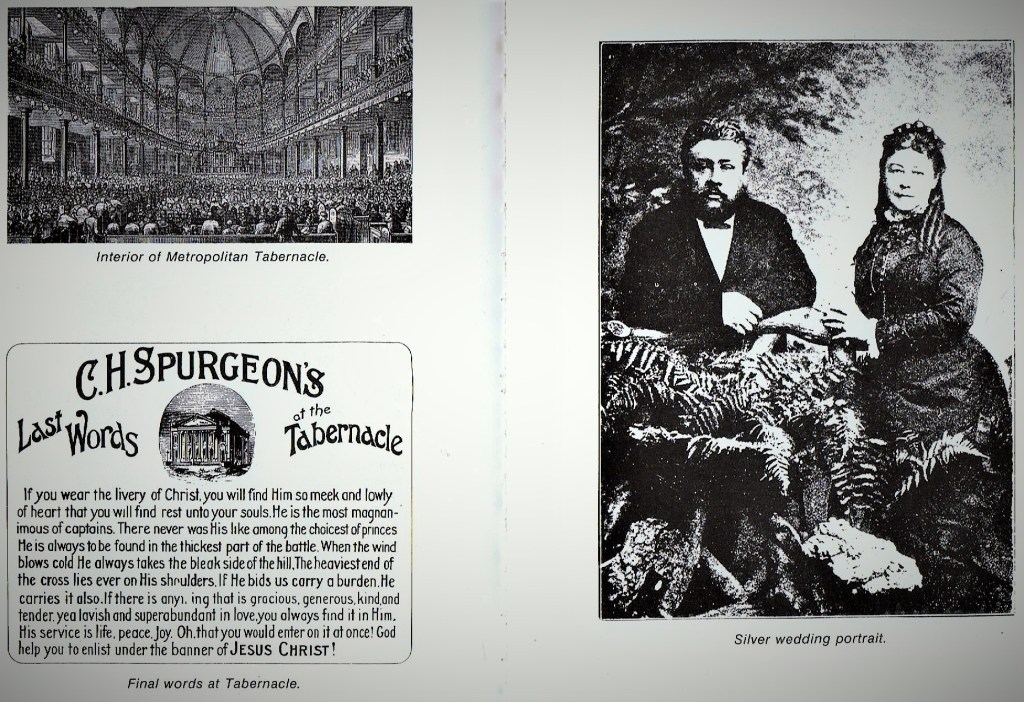

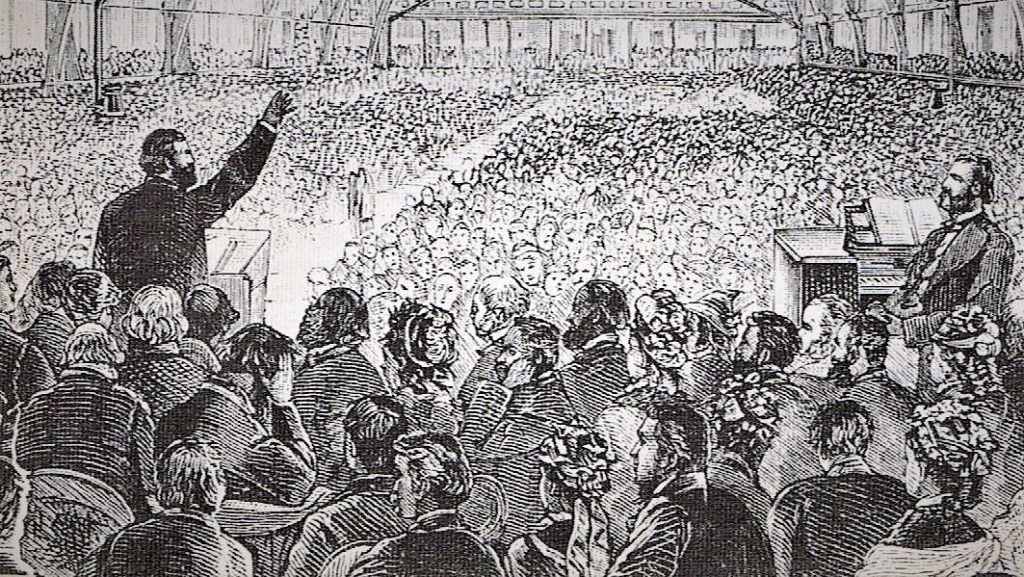

Spurgeon’s sermons drew many thousands to his churches, first at New Park Street Chapel and then at the Metropolitan Tabernacle in London (shown below). When printed, the sermons were also sold in their millions to people in the streets, and have since been distributed in more than two hundred million copies worldwide, giving some indication as to the continuing appeal of his thoroughly Biblical expositions. At the heart of Spurgeon’s desire to preach was a strong desire to develop a pastoral ministry. He did not regard people simply as souls to be saved, but loved them and wanted the best for them. His concern for their welfare extended to those involved in Christian ministry in all its forms, not just to ordained pastors. His book, Lectures to my Students was produced for those training for full-time ministry, but Counsel for Christian Workers was published for other people involved in a variety of Christian work. It contains Spurgeon’s clear-sighted viewpoints, advice and wisdom on the practical issues facing such people in their ministry.

Spurgeon himself had been born into a very modest home at Kelvedon in Essex. As early as 1861, following the opening of the Metropolitan Tabernacle in London, the great Baptist preacher warned against the atmosphere of snobbery which he perceived was increasingly prevalent among his flock:

There is growing up even in our Dissenting churches, an evil which I greatly deplore, a despising of the poor. I frequently hear, in conversation, such remarks as this:

“It is of no use trying in such a place as this: you could never raise a self-supporting cause. There are none but poor living in this neighbourhood.”

… You know that in the city of London itself, there is now scarce a Dissenting place of worship. The reason for giving most of them up and moving them into the suburbs is that all the respectable people live out of town, and of course they are the people to look after. They will not stop in London. They will go out and take villas in the subsurbs where it may be maintained.

“No doubt,” it is said, “the poor ought to be looked after: but we had better leave them to another order, an inferior order. The city missionaries will do for them; send them a few street preachers.”

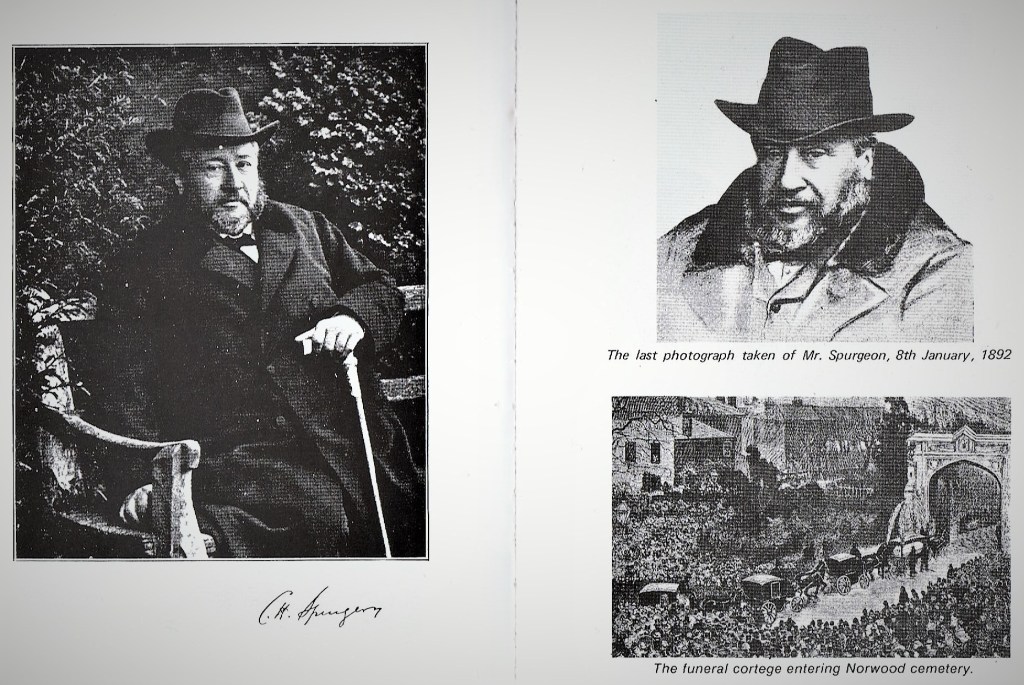

In 1865, in a bid to increase the numbers giving ordained ministry to the poor in the developing towns and cities, Spurgeon inaugurated the Annual Conference of the Pastors’ College. The foundation stone for the College building was laid eight years later. During his lifetime he gave twenty-seven addresses as President at the Conference. Many hundreds of ministers and students would gather each year to hear the ‘Governor’ at his best. He also became directly involved in setting up institutions to combat pauperism. He founded Stockwell Orphanage for Boys in 1867, followed by a Girls’ Orphanage in 1879. In April 1891, he gave his address, The Greatest Fight in the World (taking as his text I Tim. vi: 12 – “Fight the Good Fight of Faith”). While preparing this, he wrote to friends at the Tabernacle, “My soul is on fire with a desire for a special blessing from the Lord…” Little did he know that this would be the last conference he would attend. His address was one of the most powerful he delivered and was rapturously received by the vast assembly. Following the Conference, the transcript was revised and promptly published, later translated into many languages, passing through several editions.

As if he knew that his influence would continue after he had departed, Spurgeon said:

“Those preachers whose voices were clear and mighty for truth during life continue to preach in their graves. Being dead they yet speak; and whether men put their ears to their tombs or not, they cannot but hear them…”

The most noted evangelist of the age, the great American preacher D. L. Moody (1837-99), was inspired by Spurgeon’s preaching. He first heard the Baptist pastor during a visit in 1867, but it was his own tour of Britain in 1873-75, sponsored and encouraged by Spurgeon, that launched his career as a renowned evangelist. It started unpromisingly but by the time he returned to America, he was a preacher of international fame. By then, he had already teamed up with Sankey, and Harry Moorehouse had taught him how to preach. When he left England it was to devote his life to conducting revivalist campaigns. Though never as polished a preacher as Spurgeon, the style and organisation of campaigns were to have an enduring influence on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1892, Moody spoke at Spurgeon’s Jubilee Services, following the great pastor’s death at the end of January in that year:

“Twenty-five years ago, after I was converted, I began to read of a young man preaching in London with great power, and a desire seized me to hear him.

“In 1867 I made my way across the sea. The first place I came to was the Metropolitan Tabernacle. I was told that I could not get in without a ticket, but I made up my mind to get in somehow and succeeded. As Pastor Spurgeon walked down to the platform, … my heart’s desire for years was at last accomplished.

“I have been at the Tabernacle many times since, and when I looked down at those Orphan boys, when I think of the six hundred servants of God who have gone out from the college, of the two thousand sermons from his pulpit that are in print, and of the multitude of books that have come from the Pastor’s pen I would fain enlarge on all these good works…

“I say, ‘Go on brother, and God bless you.’ You are never going to die. John Wesley lives more today than when he was on this earth… Bear in mind, friends, that our dear brother is to live forever. We may never meet again in the flesh, but by the blessing of God I will meet you up yonder.”

D. L. Moody at Spurgeon’s Jubilee Services.

For the burial, Spurgeon’s body was returned to London from the south of France, where he had died. The greatest crowds ever seen in the Tabernacle were on 8 February 1892, when Spurgeon’s body lay ‘in state’. Over sixty thousand people passed before the coffin, and a similar crowd again the next day. On the 10th, the day of the funeral, the building was filled to overflowing. His body was interred at Norwood Cemetery the following day, with thousands lining the streets to pay their respects as the cortege passed by on its route, as pictured below (bottom right).

The Salvation Army and other Home Missions:

One organisation that attempted to keep in touch with the working classes was the Pleasant Sunday Afternoons (PSA) Movement, formed in the 1880s with the motto Brief, Bright and Brotherly. Its meetings were for men only and were held on Sunday afternoons so that men would not feel ashamed to come to the meeting in working clothes. The Sunday afternoon programme was part entertainment, part evangelistic and part political, with some of the early Christian Socialists as frequent guest speakers. The Salvation Army, too, came into being to serve the working classes through urban missions. Catherine Booth claimed We can’t get at the masses in the chapels, so in 1865 she set up a Christian Mission in a tent in Whitechapel, east London, with her husband, William Booth. He had already had a varied career, having preached for the Wesleyans, the Wesleyan Reformers and then the Methodist New Connexion, by whom he was ordained in 1858 after being disciplined in the previous year for his regular itinerant preaching. He stayed with the New Connexion for only three years before again becoming an irregular itinerant. The Salvation Army soon became known for its uniforms and music. The Salvation Army band shown below was from Penzance in Cornwall, photographed in the 1880s. General Booth can be seen in the back row, with his trademark top hat and a long beard.

The Whitechapel Mission grew into the Salvation Army, to the irritation of many churchmen. Even the evangelical reformer, Lord Shaftesbury, in extreme old age, concluded that the Salvation Army was a trick of the devil, who was trying to make Christianity look ridiculous. It also met with violent opposition from a ‘Skeleton Army’ which parodied Booth’s activities and was supported by brewers who were opposed to the Army’s teetotalism as a threat to their trade. Contrary to the popular image of the early Salvationists, they were more concerned about moral and spiritual matters than social conditions among the working classes. In fact, Booth spoke out against attempts to deal with the latter, arguing that they were simply due to a lack of bricks and mortar. The first thing to be done to improve the conditions of the wretched was to get at their hearts. The Salvation Army did not see itself as being engaged in a war against poverty and oppressive political philosophies. Moreover, Booth himself was authoritarian in his attempt to achieve results. He gained control of the Mission in 1877 by what was virtually a military coup. After that, the military emphasis was developed, with uniforms, corps and citadels, and the magazine, The War Cry. But this did not worry the ordinary Salvationist, for, as Booth remarked, the Salvation Army made every soldier in some degree an officer, charged with the responsibility of so many of his townsfolk. It offered them not only a force with which they could identify but also a task to which they were committed. The Salvation Army officers filed regular reports on ‘slum work’ in their towns and districts:

Mrs W. – of Haggerston slum. Heavy drinker, wrecked home, husband a drunkard, place … filthy, terribly poor. Saved now over two years. Home A1, plenty of employment at cane-chair bottoming; husband now saved also.

A. M. in the Dials. Was a great drunkard, did not go to the trouble of seeking work. Was in a slum meeting, heard the Captain speak on ‘Seek ye first the Kingdom of God!’ Called out and said “Do you mean that if I ask God for work, he will give it to me?” Of course she said “yes.” He was converted that night, found work and is now employed in the gas works, Old Kent Road.

Jimmy is a soldier in the Borough slum. Was starving when he got converted through being out of work. Through joining the Army he was turned out of his home. He found work, and now owns a coffee-stall in Billingsgate Market, and is doing well.

The Army was perhaps the only Christian movement to reach the masses on their own terms in Victorian and Edwardian Britain. They understood the need to use modern means of mass communication and, in particular, the techniques of religious advertisement. To begin with, the Salvation Army continued in the tradition of revivalist evangelism, adding its own military dimension, which fed the appetites of an increasingly imperialist and jingoistic nation. But Booth’s friendships with Congregationalist theologian J. B. Paton, and W. T. Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, led him to engage with a wider range of social concerns and problems. When he published In Darkest England and the Way Out in 1890, The Methodist Times exclaimed, Here is General Booth turning Socialist. The book, widely believed to be mainly the work of Stead, was designed to show that the submerged tenth of the British people was as much in slavery as certain African tribes. This produced a rift in the ranks of the Army. On the one hand, Frank Smith wrote a column for The War Cry under the unfamiliar heading ‘sociology’, pressing for further social action. On the other hand, more conservative officers feared that the social scheme was a turning aside from the highest to secondary things.

The Booths had found themselves unable to reach the masses from a position within mainstream Methodism. In the nineteenth century the Wesleyan Methodists, led by Jabez Bunting, became a staid, respectable denomination. It imposed upon itself in the nineteenth century a ‘no politics’ rule, and until the late 1880s, it was suspicious of open political discussion. But Methodism had within itself its own nonconformity where this restraint was missing. For example, the Staffordshire Primitive Methodists produced several Chartist leaders. Involvement in chapel affairs made them into natural community leaders. They learnt organisation based on local church government and public speaking skills based on preaching and participation in church meetings and congregational worship. The local lay-preacher, like Joseph Arch in Barford, Warwickshire, could step readily from the pulpit to the strike platform. As a result, the Primitive Methodists developed a close connection with the growth of the mass Trade Union movement, both in urban and agricultural areas. John Wilson, the leader of the Durham miners, described his conversion at the age of thirty-one at a Primitive Methodist Class Meeting:

I took my seat, and when the class leader came to where I was sitting and me to tell him how I was getting on (meaning in a spiritual sense), I was speechless. The others, in response to his query, had replied readily but my eloquence was in my tears which I am not ashamed to say flowed freely … All was joy, and not not the least joyous was myself, even while the tears were chasing down my cheeks. This change made, I began seriously to consider how I could be useful in life.

This conversion experience led to a search for education, enrolment as a local preacher, an office within the Miners’ Union, and election to Parliament in 1885, as one of the earliest Labour MPs. Many other ‘Lib-Lab’ and independent Labour leaders, especially in the northeast of England and South Wales, had similar stories to tell.

In November 1886, the Revd. Samuel Francis Collier was placed in charge of the new Methodist Central Hall, Manchester, built at the then prodigious cost of forty thousand pounds. Magnificent though the Hall was, the dynamic evangelist, with a social as well as a spiritual conscience, soon launched a programme of practical help for the poor, using the motto ‘Need not creed’ in his daring new ministry. Nobody in need was to be refused help, regardless of belief. In 1891, an old rag factory was established at Ancoats, salvaging the waste of the city, old bottles, jars, empty tins, cotton waste, pails and clothing all being sorted for re-use and sale, destitute men being given a good bed and three square meals a day for their labour. From that venture in social rehabilitation grew the most complete set of social service premises possessed by any church in Britain. By the early 1900s, a Men’s Home, Labour Yard, Women’s Refuge, a Maternity Hospital for unmarried mothers and a Labour Advice Bureau had all been developed together with educational clubs, prison visiting services and holiday funds. The picture below shows the boys in the Labour Yard of the Manchester and Salford Wesleyan Missions. Outcasts of industrial society, they were welcomed by Collier and provided with clothes, food, shelter and hope in exchange for ‘honest toil’.

Church v Chapel – Establishment Schools & Progress for the Poor:

In the early decades of the century, the Home Office had feared leaving education in industrial areas to Methodists, a set of men not only ignorant but of whom I think we have of late too much reason to imagine are inimical to our happy constitution. The 1820s saw the end of the easy eighteenth-century co-existence between church and chapel. The revival of hostility led to a fierce campaign for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, which was successful in 1828. Even after repeal, however, many irritants remained for nonconformists: first, the need for them to secure validity for marriages and funeral rites, then the campaign to repeal church rates, which were finally abolished in 1868. The ancient universities were bastions of Anglican power, and a campaign to open them to nonconformists achieved most of its aims by 1871. Early Victorian nonconformist movements tended to concentrate on the negative campaign of disestablishment. But the free church movement of the 1890s was more missionary-minded. It also reflected certain solid achievements concerning unity among the free churches. In 1856 a number of Methodist groups came together to form the United Methodist Free Church; Presbyterian union was achieved in 1876 and in 1891 the New Connexion of General Baptists was finally united with the Particular Baptists. But at the end of the century, the rift between church and chapel in English and Welsh societies still ran very deep. It was not simply the chapels of the industrial revolution confronting the churches of the rural squirearchy; urban Anglicanism and rural Dissent were equally part of the conflict, and in no area of life more so than the schools.

The chief providers of elementary education for most of the nineteenth century had been the voluntary bodies, especially the churches, from the 1830s receiving Treasury grants. Some among the middle classes supported universal education for philanthropic reasons, to prevent crime and immorality, or as insurance against social unrest. Some Anglicans were alarmed at the growth of Catholicism and Nonconformity and saw an Anglican education system as a defence against this. There was opposition, however, from those, especially farmers, who feared that educating the working classes would lead to higher taxes and labour costs, if not the spread of radical political ideas. National differences in education and literacy were marked. Levels of literacy were comparatively low in many parts of rural Britain, where school attendance was also low, but especially high in Scotland and Ireland, where favourable attitudes to an educated population were supported by a network of parochial schools. They were also higher among girls than boys in some areas where they were educated at voluntary schools, for example in East Anglia. In 1844, William Locke reported on the English ‘Ragged Schools’:

In many cases, because the children are so destitute that they cannot be taught, we give food – generally soup, occassionally meat, and good wholsome bread, sometimes coffee or cocoa, and bread and cheese. In one school they feed about two hundred twice or thrice a week … The children who come to the schools pay nothing; all the Ragged Schools are quite free, being intended only for the destitute.

Kindness, Christian love to the children and teaching them their duty to their duty to their neighbours and to their God, and making the Bible the theme of all our instruction …

Thirteen years before the first Education Act, when countless children toiled ten or twelve hours a day in a mill or a colliery, Jeremiah James Colman opened Carrow School for the children of his employees at his Stoke and Carrow mustard works in Norwich. He was the grandnephew of the founder of the company, a strong Nonconformist, philanthropist and Member of Parliament. The weekly payment for attendance at the school was a penny for one child, three halfpence for two and twopence for a third from the same family. The first school was over a carpenter’s shop and crammed in fifty-three pupils. In an opening statement, Colman announced:

… the school helps you to educate your children and to train up a set of men who will go into the world qualified for any duties they may be called upon to discharge.

With a workforce of three and a half thousand, Colman’s was, in effect, the local community and it was likely that their duties would be discharged in manufacturing mustard. The school began each morning with a hymn, a prayer and a Bible reading, but while a Colman education included diligent and careful teaching of the scriptures, it also included art and craft subjects in addition to ‘the three r’s’. Not only was Colman far-sighted in his attitude to education, but he was also a firm believer in women being given every opportunity for learning, and from the outset drawing and needlework were included in the subjects taught. Caroline Colman, Jeremiah’s wife, was the force in the direction and development of the school. The Colmans were also committed to technical education, and in 1899 they claimed to be the first to introduce cookery, gardening, laundry work, beekeeping and ironwork into the curriculum. As the school grew, it moved and improved, adding a wide range of technical subjects, but never neglected art and culture.

At the time the photograph above was taken in the early 1900s, Caroline Colman was intensely concerned with the physical wellbeing of her pupils, urging mothers to ensure that their daughters wore warm dresses ‘as a caution against measles and other childish ailments’. Although the children have been carefully groomed and prepared for the class photograph, their general condition of wellbeing contrasts sharply with the ‘ragged’ appearance and thin faces of the children in the London photographs. The reminiscences of former pupils were warm and grateful, happy and nostalgic if at times a little pious.

But ‘Church’ meant not only cathedrals, bishops, parishes and the Book of Common Prayer. It also meant continuing control over elementary education, the only form to which working-class nonconformists had access, deference to ‘the Establishment’ in both church and state. ‘Chapel’ stood for two forms of Dissent: the older, more loosely organised, congregational variety, and the newer, more centrally organised evangelical denominationalism of the Wesleyan Methodists and Baptists. Chapel religion had made so much progress that nonconformists were determined to secure equal rights with Anglicans. The campaign for outright disestablishment of the Church of England ceased to concern late Victorian nonconformists, except in Wales, where it was brought about in 1920 (in Ireland in 1869). But the fight for control over primary and elementary schools continued until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. This battle did little credit to either side but deprived two generations of English children of education. All the labours of the Sunday schools hardly compensated for that. In Wales, the Nonconformist churches, and in Ireland, Catholics opposed state funding of education, fearing Anglican propaganda. The Welsh Calvinistic Methodists and Independents also feared that the established Church sought to extinguish the Welsh language through the provision of monolingual English schooling. This strategy would undermine the Sunday schools provided by the Nonconformist chapels, in which Welsh was the medium of instruction.

The Churches and the Co-operatives – the views of Beatrice Webb:

With its satellite towns of Stockport, Salford and Oldham, Manchester was the most impressive example of urban expansion up to the mid-century, and its dependence on factory industry and persistent identification with the ‘gospel’ of the market economy. This also extended among the mill towns of Lancashire and Yorkshire, like Radcliffe (shown above).

Beatrice Webb, née Potter, (1858-1943) was born into a Lancashire family who became integrated into the traditional administrative and professional class, and Beatrice found herself related to a good proportion of the academics, senior civil servants and leading lawyers of the capital. On the other hand, she still kept in contact with her Lancashire forebears who had not made the transition. Stimulated by the great Charles Booth, she embarked in 1884 on her own programme of social research into Co-operation and Nonconformity in Bacup, a town in the South Pennines of Lancashire, close to the border with Yorkshire. In a letter to her father, She wrote of her enquiries into the operations of the co-operative societies in the town, entirely owned and managed by working men:

I have spent the day in the chapels and schools. After dinner, a dissenting minister dropped in and I had a long talk with him: he is coming for a cigarette this evening after chapel. He told me that in all the chapels there was a growing desire among the congregation to have political and social subjects treated in the pulpit and that it was very difficult for a minister, now, to please. He also remarked that in the districts where co-operation amongst the workmen (in industrial enterprise) existed, they were a much more independent and free-thinking set.

There is an immense amount of co-operation in the whole of this district; the stores seem to succeed well, both as regards supplying the people with cheap articles and as savings banks paying good interest. Of course, I am just in the centre of the dissenting organisation; and as our host is the chapel keeper and entertains all the ministers who come here, I hear all about the internal management … each chapel is a self-governing community, regulating not only chapel matters but overlooking the private life of its members.

Forty years after the Rochdale Pioneers founded the first co-operative society, the young social researcher, not yet a socialist, was clear about the ties which existed between the Nonconformist chapels in Bacup and the local co-operatives. Beatrice wrote in her now well-known diary:

One cannot help feeling what an excellent thing these dissenting organisations have been for educating this class for self-government. I can’t help thinking, too, that one of the best preventives against the socialistic tendency of the coming democracy would lie in local government; which would force the respectable working man to consider political questions as they come up in local administration.

… they are keen enough on any local question which comes within their own experiences and would bring plenty of shrewd sound sense to bear on the actual management of things…

There is an immense amount of spare energy in this class, now that it is educated, which is by no means used up in their mechanical occupation. … It can be employed either in the practical solution of social and economic questions or in the purely intellectual exercise of political discussion about problems considered in the abstract. …

In living amongst mill-hands of East Lancashire … I was impressed with the depth and realism of their religious faith. … Even the social intercourse was based on religious sympathy and common religious sympathy and common religious effort. ..

From Individualism to Collectivism – Clifford and Christian Socialism:

As the Victorian period progressed, there emerged a proliferation of philanthropic activity. Alongside the itinerant societies and the great urban Sunday schools, there developed a nondenominational Christian press and a great battery of Bible, tract and missionary societies. These organisations formed a pattern of Christian progress all the way from ‘Basle to New York’, all seeking to capitalise on the evangelistic opportunities which seemed to be afforded by the turmoil in western societies. This movement, much like the societies which created it out of the social tensions of the first half of the nineteenth century, had seemed to be getting out of control by the middle decades of the century. In consequence, the ‘undenominational evangelism’ of the Evangelical Revival was gradually replaced by the assertion of ‘denominationalism’ by the end of these decades. The earlier decades of philanthropic activity had been based on perilously fragile ‘social theology’. Some Christians argued that the campaign for social righteousness was essential to a proper gospel ministry, whilst others still saw social action as little more than a device for securing a working-class audience for the gospel. In the earlier part of the century, the activities of those calling themselves ‘Christian Socialists’ did not add up to very much. The novelist Charles Kingsley had set out their possibilities in Alton Locke (1850). But the Christian Socialist co-operative workshops were poorly organised, unduly idealistic about the contribution of labour, and only lasted a short while. However, Christian Socialists did good work in securing a better legal framework within which workers’ organisations, including trade unions, could develop, and in fostering workers’ education.

Within the Nonconformist tradition, however, the individualistic emphasis upon personal conversion had always had to be held in tension with a corporate understanding of the church and its role in society: as the normative social philosophy of Victorian Britain changed from individualism to collectivism, this correspondingly this second emphasis, which for much of the century was neglected, came into new prominence. Social Science may well have been a middle-class preoccupation of the mid-century, but when linked with the Kingdom of God theology of the Christian Socialists it provided an important link between the Christian Chartism and ‘Political Dissent’ of the 1830s and ’40s with the ‘Nonconformist Conscience’ or ‘Social Gospel’ of the ’80s and ’90s. The Baptist pastor, John Clifford, was actively involved in campaigning against the ‘living in’ system, as the photograph below shows. Dressed like dukes, treated like slaves, as the slogan went, since shop assistants were expected to dress like aristocrats and to spend their lives in total subjection to their employers. Almost half a million were of them were compelled to ‘live in’ their employers’ premises in conditions that were appalling and institutional. The shopowners created a tyranny as harsh as the yearly bond system of the mine owners or the feudal power of the squirearchy. Stores were open from morning to night for six days a week and working hours of eighty to ninety hours per week were common.

The ‘living in’ system bound the shopworker to the shopowner as tightly as the tied cottage bound the labourer to the farm owner. Much of the accommodation was barrack-like with beds alive with fleas and walls crawling with bugs. Baths were rarely provided and hot water was almost as scarce. The rules of one Knightsbridge store forbade lights after 11 p.m., breaching of which resulted in instant dismissal. Sleeping out required permission and failure to comply with this also resulted in dismissal on the second offence. Assistants were also forbidden to marry without permission and communal living denied them the vote. On their one free day, they were expected to attend church, not chapel. The photograph, taken in May 1901, shows thirteen shop assistants advertising a meeting against the system, with Dr Clifford as the chief speaker. The sandwich boards were hired from the Church Army; third in line is P. C. Hoffman, a pioneer of the Shop Assistants’ Union and a trade union official for forty years. In his Fabian Tract of 1897, Socialism and the Teachings of Christ, Clifford encapsulated the transition from individualist to collectivist thinking among many Nonconformists and Church organisations:

Collectivism, although it does not change human nature, yet takes away the occasion for many of the evils which now afflict society. It reduces the temptations of life in number and in strength. It means work for everyone and the elimination of the idle, and if the work should not be so exacting, responsible, and therefore not so educative for a few individuals, yet it will go far to answer Browning’s prayer:

“O God, make no more giants,

Elevate the race.”

… Individualism adds to the number of the indolent year by year; collectivism sets everybody alike to his share of work, and gives to him his share of the reward. … Collectivism affords a better environment for the teachings of Jesus concerning wealth and the ideals of labour and brotherhood. If a man is … only ‘the expression of his environment’ … then it is an unspeakable gain to bring that environment into line with the teaching of Jesus Christ.

In the Gospels, accumulated wealth appears as a grave peril to the spiritual life, a menace to the spiritual life, a menace to the purest aims and noblest ideals. Christ is entirely undazzled by its fascinations and sees in it a threat against the integrity and progress of his kingdom. ‘Lay not up for yourselves treasures on earth’. …

Now, though Collectivism does not profess to extinguish vice and manufacture saints, it will abolish poverty, reduce the hungry to an imperceptible quantity, and systematically care for the aged poor and for the sick. It will carry forward much of the charitable work left to individual initiative … is not all that in harmony with the spirit and teaching of Him who bids us see Himself in the hungry and sick, the poor and the criminal?

… Collectivism fosters a more Christian conception of industry; one in which every man is a worker, and each worker does not toil for himself exclusively, but for the necessities, comforts and privileges he shares equally with all members of the community. … It is a new ideal of life and labour that is most urgently needed. England’s present ideal is a creation of hard individualism; and therefore is partial, hollow, unreal and disastrous. …

Individualism fosters the caste feelings and caste divisions of society, creates the serfdom of one class and the indolence of another; makes a large body of submissive, silent, unmanly slaves undergoing grinding toil and continuous anxiety, and a smaller company suffering from debasing indolence and continual weariness. … No! the ideal we need and must have is in the unity of English life, in the recognition that man is complete in the State, at once a member of society and of the Government…

Dr John Clifford (1836-1923) was a prominent Baptist minister and President of the Christian Socialist League. This was the successor organisation to the Christian Socialist Society which took over the management of the Christian Socialist magazine from the Chartist Land Reform Union. Clifford was also an early member of the Fabian Society. As a liberal evangelical minister in Paddington from 1858, Clifford set this new ideal of life and labour against what he called the hard individualism of late Victorian society. It was this individualism that he saw as partial, hollow, unreal and disastrous, fostering the serfdom of one class and the indolence of another. It had created, on the one hand, a large class of submissive, silent… slaves undergoing grinding toil and continuous anxiety, and on the other a smaller class suffering debasing indolence. It spawned hatred and ill-will on the one hand and scorn and contempt on the other. This was at odds with the common ideal in both the soul of Collectivism and the revelation of the brotherhood of man in Christ Jesus.

The ideas of F. D. Maurice, a principal Christian Socialist thinker, were also to have a tremendous impact on Anglican thought about the secular world in the following century and to bring the movement to its climax in the work of William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury (1942-44). This was partly due to the work of the Christian Social Union, founded in 1889 with Brooke Fosse Weston, the Cambridge New Testament scholar and later Bishop of Durham, as its first president. Evidence for the early role of Christian Socialists in the move towards independent politics can be found in that, as early as March 1895, a ‘Christian Socialist’ candidate fighting alone against the Liberal candidate for East Bristol lost the parliamentary election by only 183 votes in a total poll of over seven thousand. The Welsh Religious Revival of 1904-5 also helped promote the rise of working-class collectivist politics, first in the Liberal Party, but then in the development of a separate Labour Party.

Joseph Chamberlain, Birmingham Nonconformity & Social Reform:

By Elliott & Fry – https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw98681/Joe-Chamberlain, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=84982200

In the Industrial Revolution, Birmingham had played a major role in the technological breakthroughs of the early part of the century with the improved form of the steam engine produced at the Boulton and Watt factory in the city. Birmingham had become known as the ‘city of many trades’ and maintained its position as a centre for smaller manufacturers alongside the expanding larger-scale factory industry. Indeed, its diverse industrial base made it a serious rival to Manchester as Britain’s second city in the second half of the nineteenth century. From the Nonconformist point of view, R. W. Dale (1829-95) delivered a Lecture to the New Electors, addressing the citizens of Birmingham who had acquired the vote as a result of the 1867 Reform Act. This had enfranchised the majority of working-class men, but not the ‘slum-dwellers’ whom Dale saw as a threat to social order in the urban areas:

You have a great practical concern in whatever measures are likely to make the criminal classes disappear, and I trust that such measures will have your hearty support. … There is another class from which we have almost as much to fear … one million persons receiving relief.

… And in this million you have first the permanent paupers, and then a vast mass of people who are on the parish on and off again every few months, but who when they go off are sure to leave successors … We have hereditary paupers, as well as hereditary criminals, and I maintain that this is intolerable.

… You will feel very distinctly the sharp pressure that comes upon the community for the support of the ‘armies of the homeless and unfed’, and will be the more eager to discover how the pauperism of the country can be effectively diminished.

In Birmingham, as Dale knew well, the city’s municipal administration was notably lax with regards to public works, and many urban dwellers lived in conditions of great poverty. As a Congregational minister, Dale chastised his fellow nonconformists over their lack of action:

We are living in a new world and evangelicals do not seem to have discovered it. The immense development of the manufacturing industries, the wider separation of classes in great towns … the new relations that have grown up between the employers and the employed, the spread of popular education, the growth of a vast popular literature, the increased political power of the masses of the people, the gradual decay of the old aristocratic organisation of society, and the advance in many forms of the spirit of democracy, have urgently demanded fresh applications of the eternal ideas of the Christian faith to conduct.

The Unitarian Joseph Chamberlain made his career in Birmingham, first as a manufacturer of screws and then as a notable mayor of the city. He became involved in Liberal politics, influenced by the strong radical and liberal traditions among Birmingham shoemakers and the long tradition of social action in Chamberlain’s Unitarian church. Chamberlain was a radical Liberal Party member and a fierce opponent of subsidising Church of England and Roman Catholic schools with local ratepayers’ money. As a self-made businessman, he had never attended university and had contempt for the aristocratic leadership of the Tory Party, both locally and nationally. In November 1873, the Liberal Party swept the municipal elections and Chamberlain was elected Mayor of Birmingham. The Conservatives had denounced his Radicalism and called him a “monopoliser and a dictator” whilst the Liberals had campaigned against their High Church Tory opponents with the slogan “The People above the Priests”. As Mayor, Chamberlain promoted many civic improvements, promising the city would be “parked, paved, assized, marketed, gas & watered and ‘improved'”. In February 1874, he wrote to Henry Allen, Editor of the Nonconformist Review, reflecting on the election results and the need for a campaign to further a closer union between nonconformists as such and the working classes.

The only chance of the Government lay in a declaration of policy calculated to arouse the hearty enthusiasm of the non-conformists and the working classes. Instead of this Gladstone issued the meanest manifesto that ever proceeded from a great Minister. … At the same time, the returns show that the present political position of the Dissenters is not satisfactory. They are very hazy as to the principles of the Education question, and have, in many cases, been carried over to the enemy by the ‘Bible’ cry.

In the latter assertion, it can be assumed that Chamberlain is referring to the provision of the 1870 act in respect of Religious Education, which placed Biblical knowledge at the centre of the curriculum, alongside numeracy and literacy. By ‘the enemy’, Chamberlain was referring to ‘the Anglican Establishment’, as he went on to explain:

Worse still, they have ceased to combine cordially with the working classes, without whose active assistance further advances in the direction of Religious Equality are impossible. But both in the case of the agricultural labourers, and in reference to the demands of the Trades Unions for the repeal of what I do not hesitate to stigmatize as class legislation of the worst kind, the Dissenters have largely held aloof, and their organs in the Press … have been unsympathetic and even hostile.

In his references to the agricultural workers and the trades unions, Chamberlain was no doubt referring to the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union, which grew out of the local union founded in Warwickshire in the early 1870s, referred to above. Led by the Wesleyan lay-preacher Joseph Arch and supported by thousands of Nonconformist workers, many Baptists and Methodists among them, it had fought wage cuts and evictions imposed by local squires simply for their tenants joining the union. Their children had been excluded from parish schools in some areas. Arch later supported Chamberlain’s ‘Liberal Imperialism’ as a means of aiding and ‘protecting’ Britain’s home industries against the ravages of ‘free trade’ in the 1880s and 90s. He organised emigration schemes for impoverished agricultural workers and their families to the ‘Dominions’, especially New Zealand. The failure of some nonconformist church leaders to support their poorer members led Chamberlain to argue that:

Unless this is altered in the future such questions as Disestablishment and Disendowment will be indefinitely postponed, as the Artisan voter can see little difference between Caesar and Pompey, and looking like the whole affair is a mere squabble between Church and Chapel, will take no interest in the matter.

Chamberlain pointed out that the only districts in which Liberalism had come out of the recent elections were the Midland Counties, where they gained one seat and the Northern Counties, where the balance was still in favour of the Liberals. There, he wrote, the local parties appealed directly to the mass of the working-class population, with the Dissenters aiding very largely with their purses and influence, and cordially recognising the justice of the labourers’ claims. Chamberlain contrasted the enduring support of the local Liberal Press in Birmingham and Newcastle, in particular, with …

… this narrowness on the part of many of the rank and file of Dissent, will be fatal to the success of our special aims unless we can induce and make a more generous recognition of the claims of the masses.

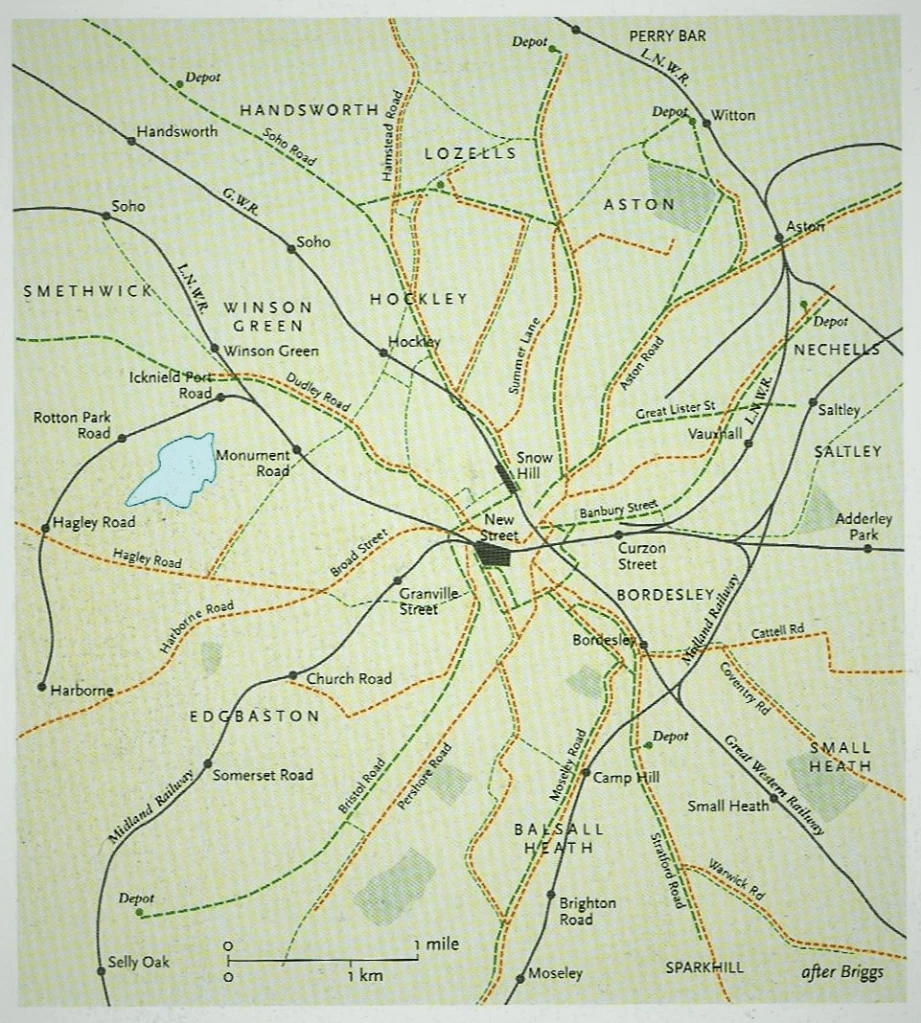

Together with the west Midland industrial towns, which also became strongholds of radical religious Dissent, Birmingham was becoming overtly political with the rise to municipal power of Chamberlain’s Liberal reformers. They set about their reforming projects and programmes with a zeal reminiscent of the evangelical campaigns of the earlier part of the century. The city rapidly gained a reputation for municipal enterprise for its public works, including one of the country’s most extensive urban tramway systems (see the map above). Cheap and efficient public transport systems, based on horse-drawn omnibuses and trams, proved to be an effective way of dispersing the industrial working class from overcrowded and disease-ridden city-centre slums. The now radicalised diarist, Beatrice Webb, commented on her conversations with him on these social themes in her diary, in entries made during their four-year relationship which had begun in 1882 when he had become a minister in Gladstone’s second government:

The same quality of one-idea-ness is present in the Birmingham Radical set, earnestness and simplicity of motive being strikingly present. Political conviction takes the place here of religious faith. … Heine said some fifty years ago, “Talk to an Englishman on religion and he is fanatic; talk to him on politics and he is a man of the world.”