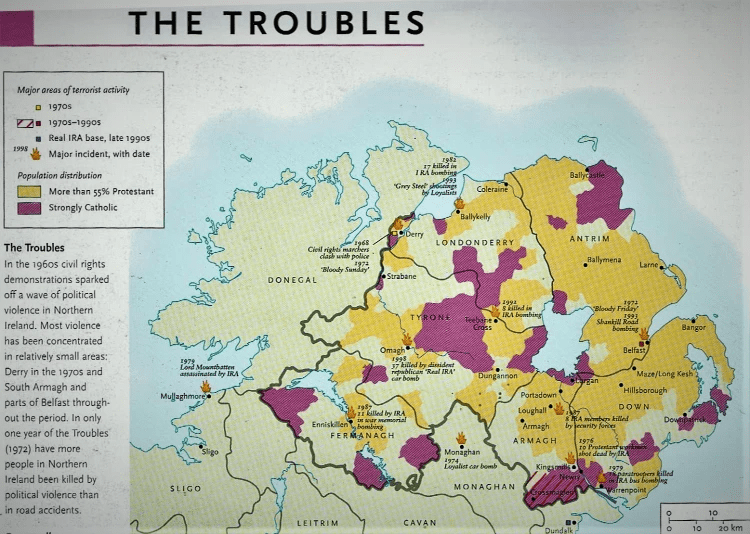

The Sectarian Divide in Belfast & the Peace Process, 1980-98:

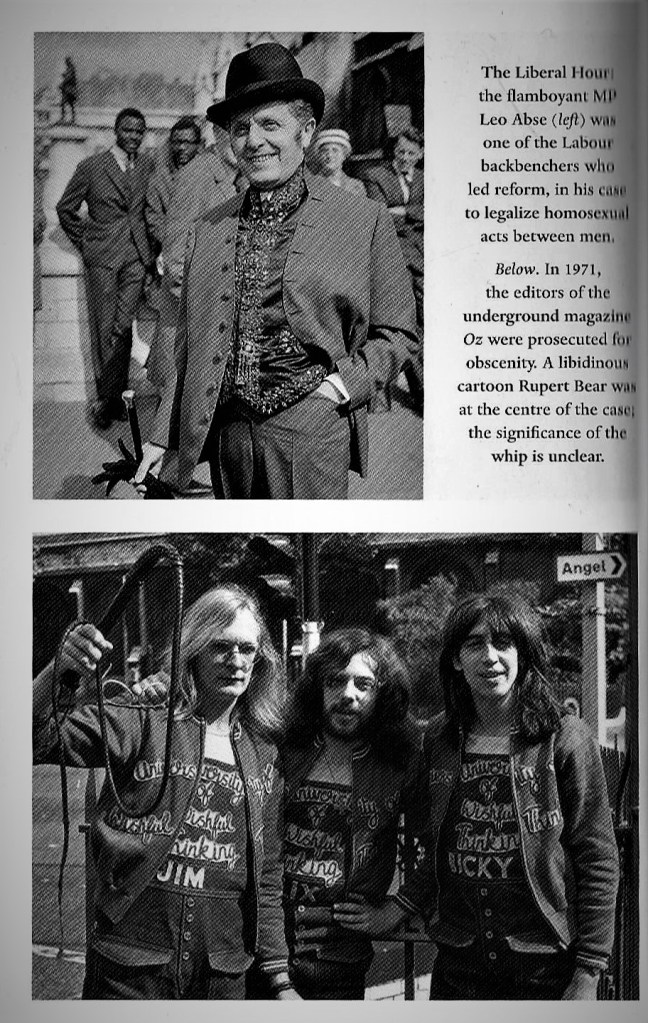

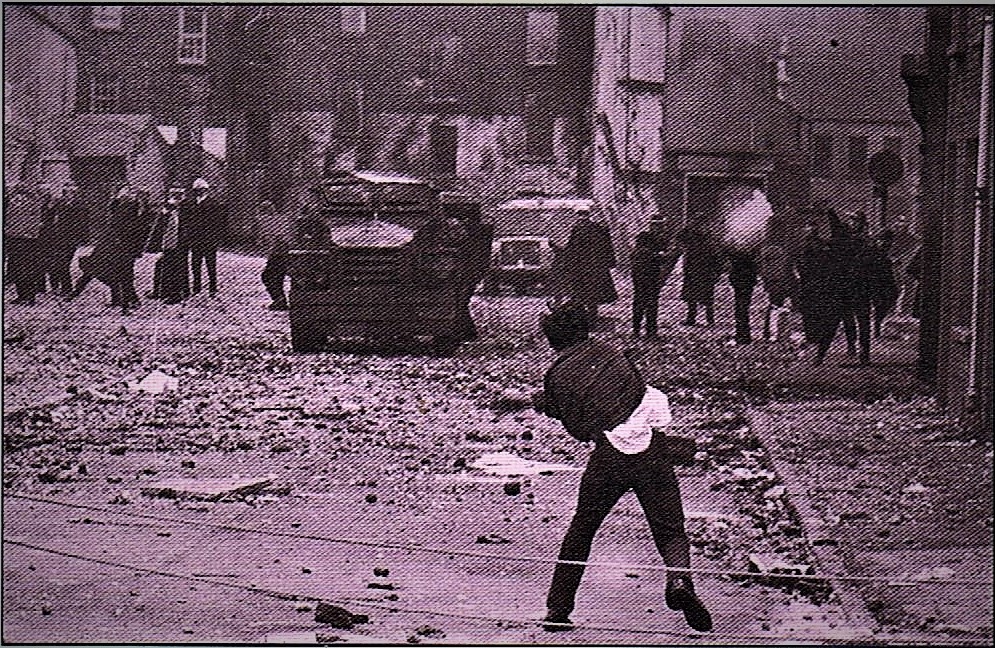

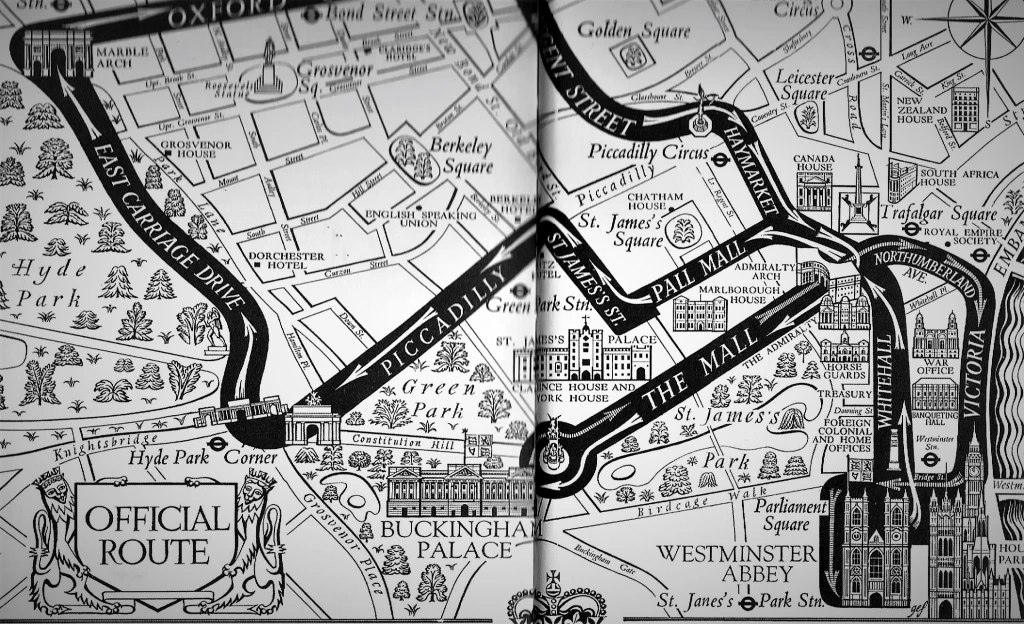

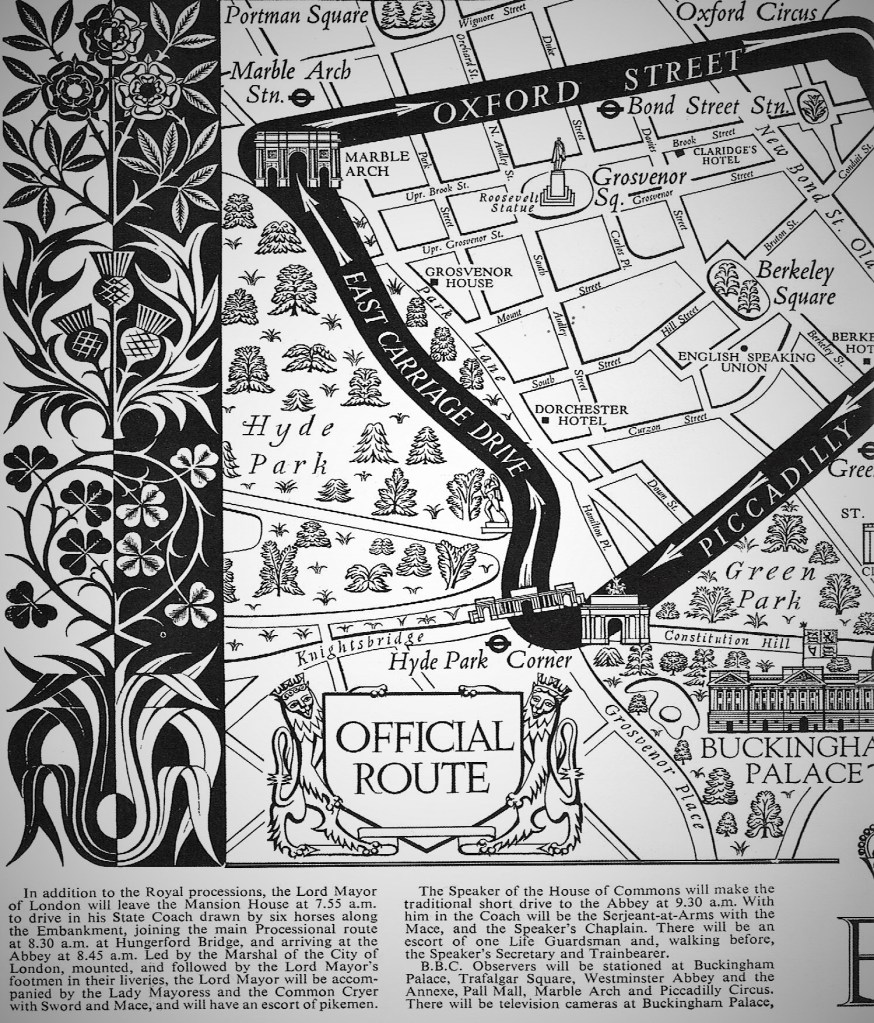

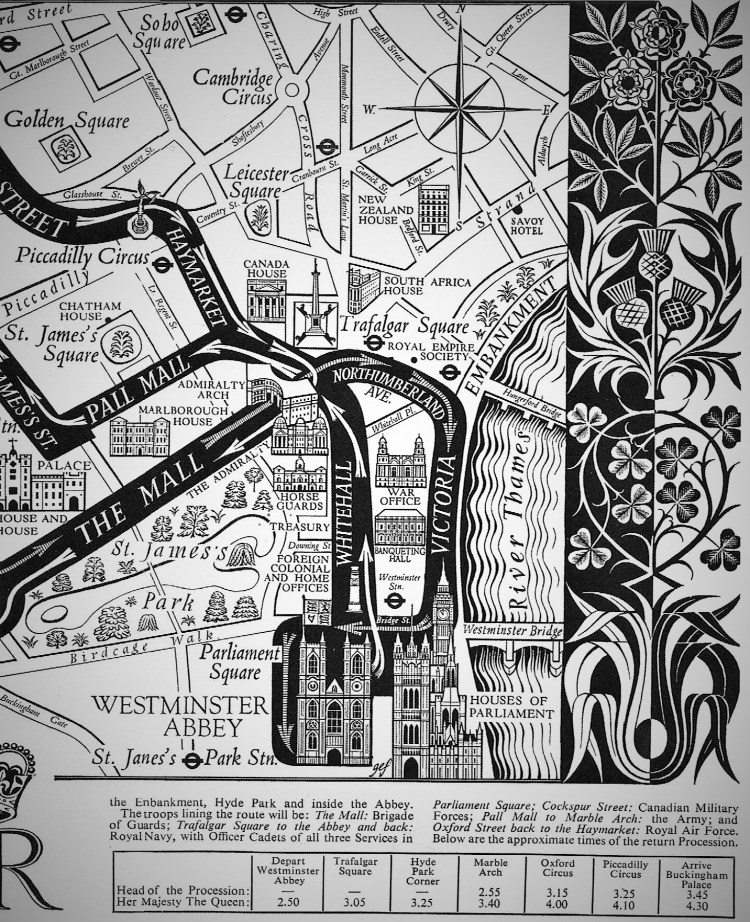

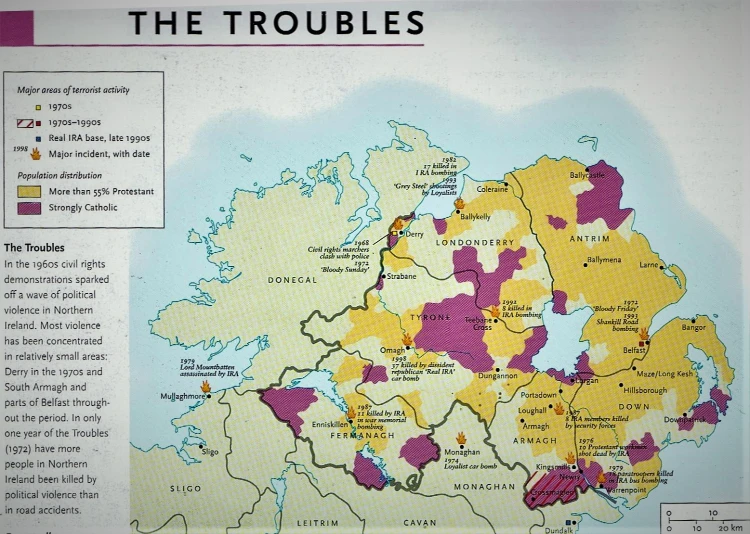

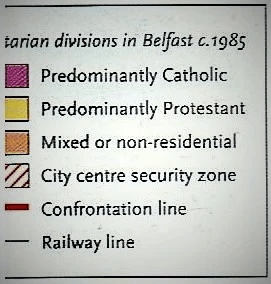

After the Provisional IRA assassinated Lord Mountbatten on his boat off the Western coast of Ireland in 1979, the mainland bombing campaign went on with attacks on the Chelsea barracks, then Hyde Park bombings, when eight people were killed and fifty-three injured. With hindsight, the emergence of Sinn Féin, the political wing of the Provisional IRA, as a political party in the early 1980s can be seen as one element in the rethinking of British policies. Yet throughout the 1980s and 1990s, there were still periodic major incidents in various places across the province. After the Provisional IRA’s cease-fire in 1994, these were initiated by dissident republican splinter groups. However, much of the continuing street violence throughout these decades was concentrated in the areas of Belfast where the population was mainly either predominantly republican or unionist, as shown on the map below.

Another preliminary element in the Peace Process was the belated interest successive Irish governments began to take in Northern Ireland during the same period. The fear that the disturbances in the North might spread south and destabilise their state lay behind the Dublin government’s decision to start talking directly to Downing Street from 1980 onwards. This led to the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985, which essentially represented a reiteration of British policy aims in the province, but now with an added all-Ireland dimension, which the Unionists continued to find difficult to accept.

The political violence in Belfast was largely confined to the confrontation lines where working-class unionist districts, such as the Shankhill, and working-class nationalist areas, such as the Falls, Ardoyne and New Lodge, border directly on the city centre and/or on one another. The mixed middle-class areas did not experience any significant political violence.

It was in the wake of this agreement that an entirely new approach emerged. Sinn Féinn’s dual strategy of ‘ballot box and bullet’, and its realisation that the war could not be won militarily, led to secret negotiations with both Dublin and London in the late 1980s in pursuit of a way into active participation in the political process. Britain’s recognition that if the extremists could be brought into the search for a political solution then the mainstream parties in Northern Ireland politics would follow suit was a complete reversal of its previous approach. Once the IRA had accepted the need for a ceasefire, the remaining difficulty was to persuade unionists that the reformed ex-paramilitaries could be trusted.

The willingness of some unionists to give up previous policies – which had consisted of trying to recover the power they had lost in 1972 – sprang from their pragmatic realisation that only sharing power with nationalists would guarantee unionists some say in the future government of Northern Ireland. It was not until the late 1990s that the Irish constitution was amended, recognising British sovereignty over Northern Ireland. US President Bill Clinton acted as a peace broker, contributing to an uneasy cease-fire in the North from 1994.

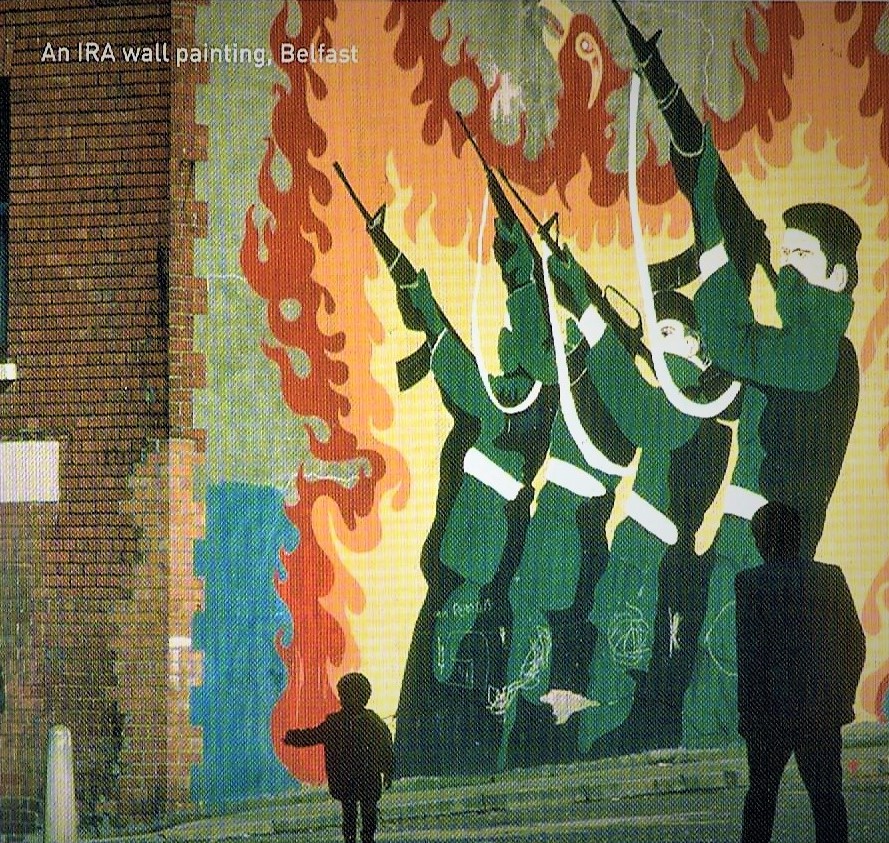

Still, the street violence persisted and intensified during the marching season in July, when the protestant Orange Order held its traditional but often offensive or provocative parades near or through Catholic areas around Belfast.

The Good Friday Agreement & the Omagh Bombing of 1998:

After long negotiations, and with the help of former US senator George Mitchell, the Good Friday Agreement was signed between all the parties to the conflict in 1998. This sought to establish a power-sharing government at Stormont, as well as acknowledging both British and Irish interests in the future of the province. The impressive Parliament Buildings in Stormont, shown below, were built in 1921 to house the new Government of Northern Ireland after Partition, and since the Belfast Agreement, they have been the home to the Northern Ireland Assembly and its power-sharing executive. Despite recurrent crises and accusations of bad faith, the peace survived more or less intact.

Picture & graphic from BBC History Magazine.

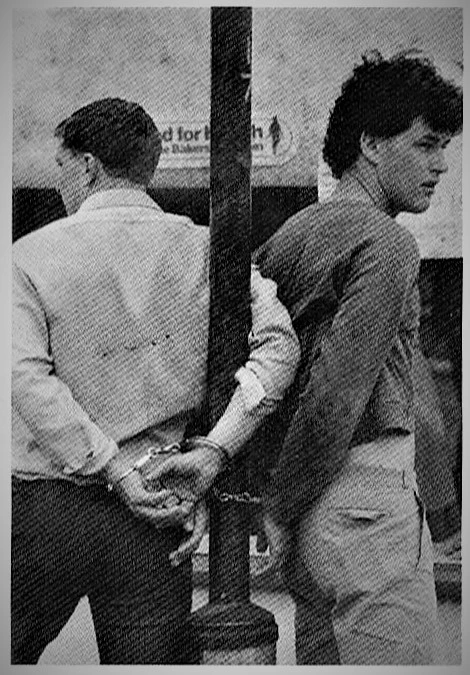

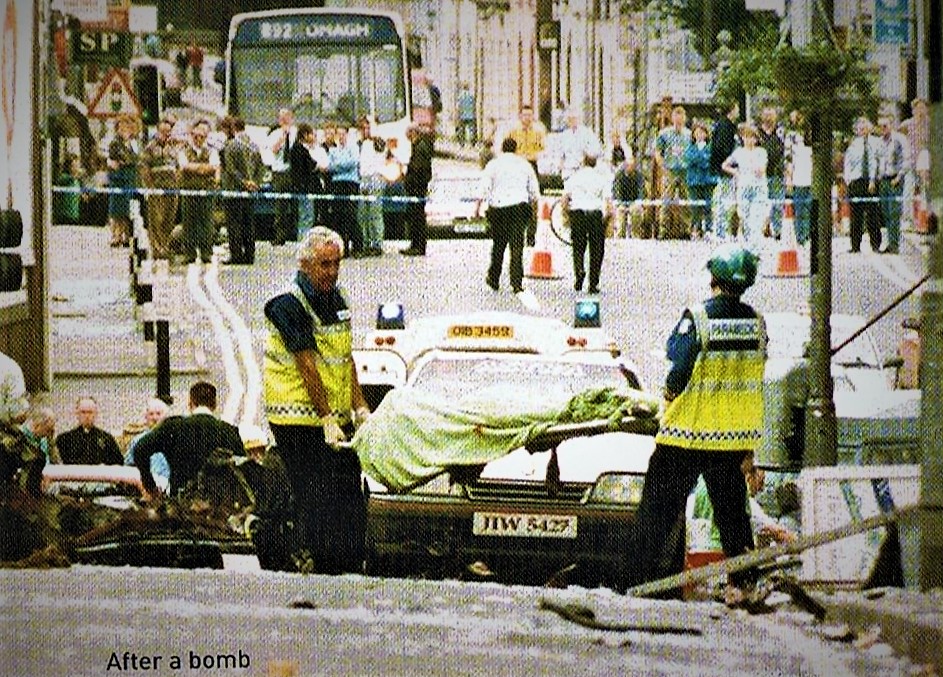

Sadly, however, it did not immediately bring an end to the bombing. The Omagh bombing was a car bombing on 15 August 1998 in the town of Omagh in County Tyrone carried out by the Real Irish Republican Army (Real IRA), a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) splinter group that opposed the IRA’s ceasefire and the Good Friday Agreement, signed earlier in the year. The bombing killed twenty-nine people and injured about 220 others, making it the deadliest single incident of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. There was a strong regional and international outcry against ‘dissident’ republicans and in favour of the Northern Ireland peace process. Prime Minister Tony Blair called the bombing an “appalling act of savagery and evil.” Queen Elizabeth expressed her sympathies to the victims’ families, while the Prince of Wales paid a visit to the town and spoke with the families of some of the victims. Pope John Paul II and President Bill Clinton also expressed their sympathies. Churches across Northern Ireland called for a national day of mourning. Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh Robin Eames said on BBC Radio that,

“From the Church’s point of view, all I am concerned about are not political arguments, not political niceties. I am concerned about the torment of ordinary people who don’t deserve this.”

The Return & Results of Widespread Mass Unemployment in Britain:

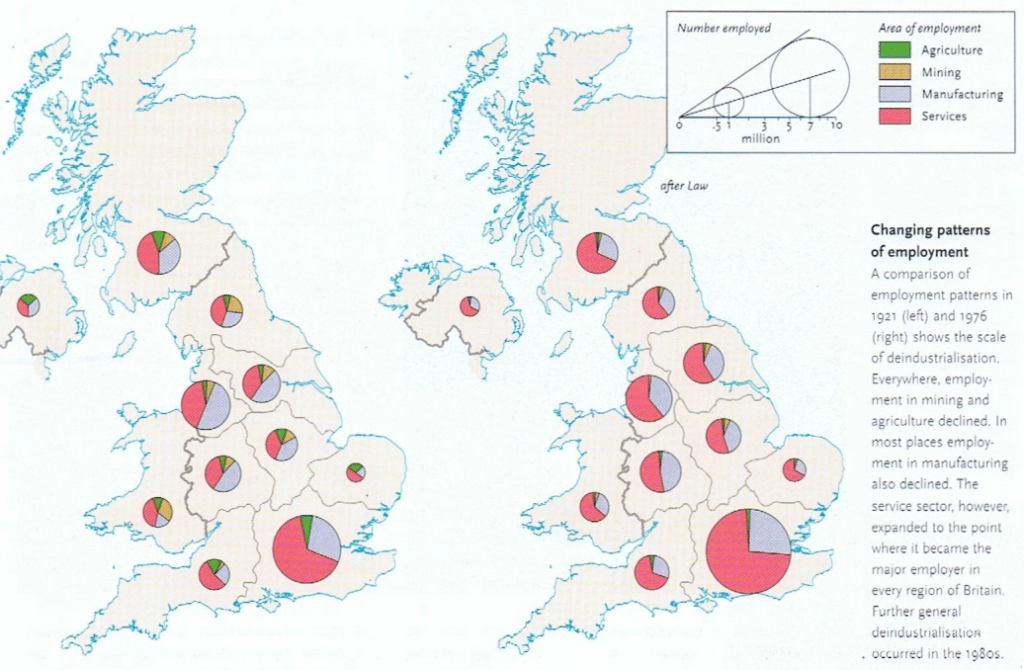

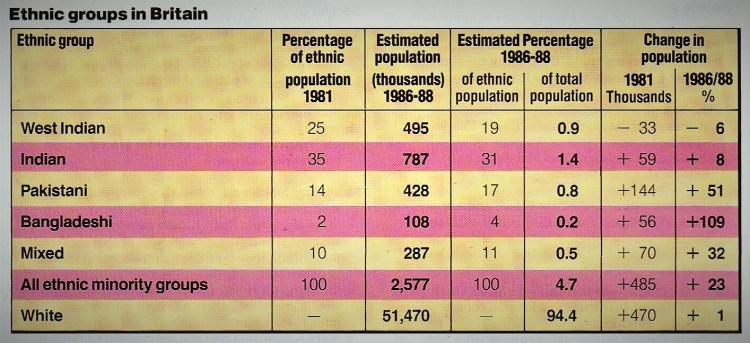

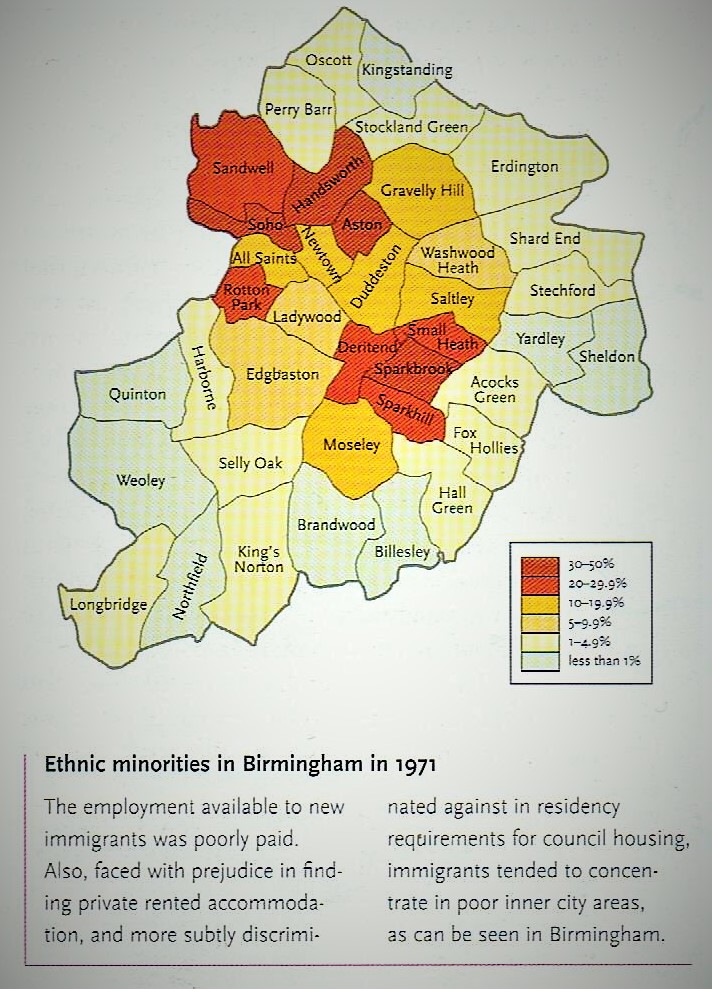

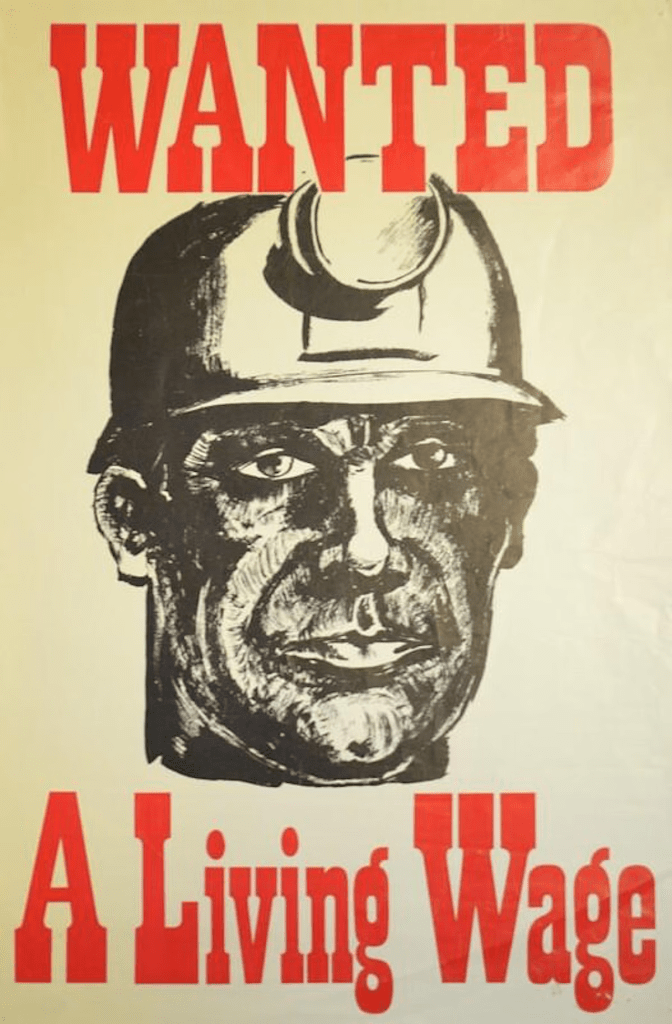

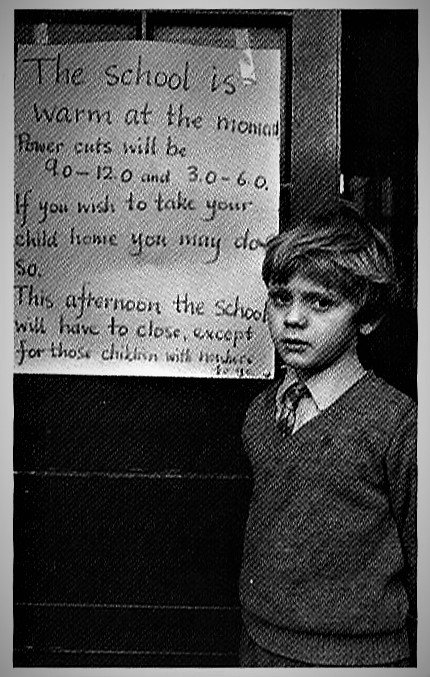

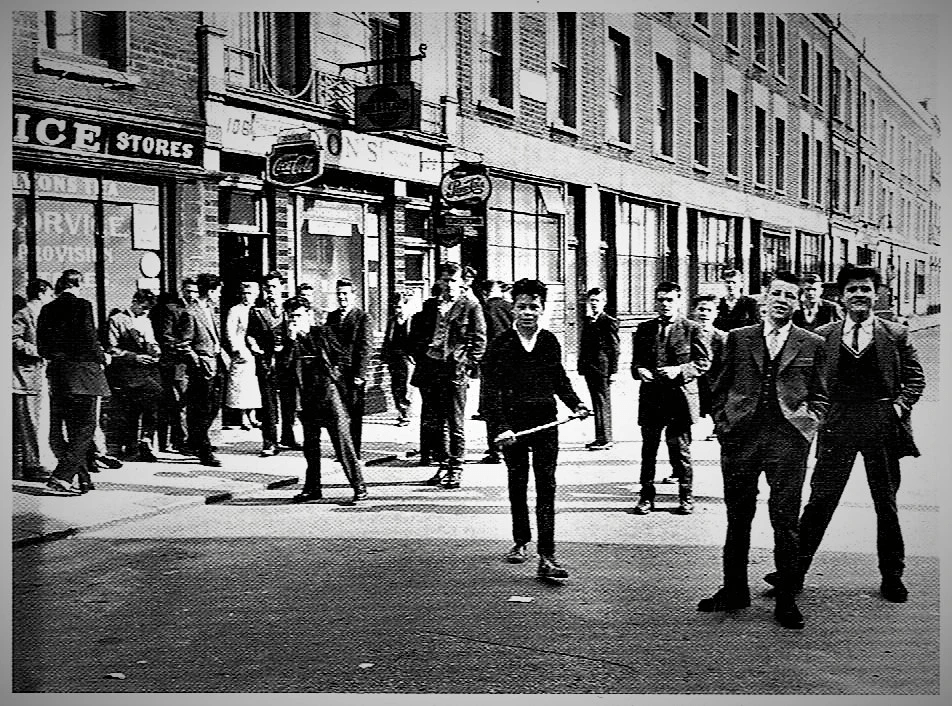

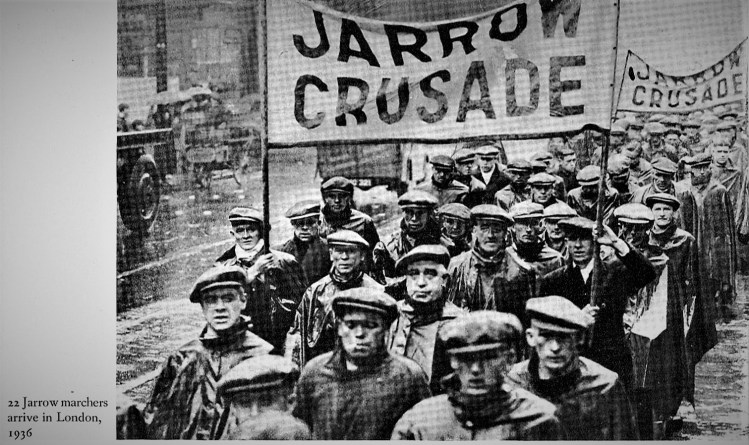

In February 1986, across the UK as a whole, there were over 3.4 million unemployed, although statistics were manipulated for political reasons and the real figure is therefore a matter of speculation. The socially corrosive effects of the return of widespread mass unemployment, not seen since the early thirties, were felt throughout the country, manifesting themselves in the further bouts of inner-city rioting that broke out in 1985. This was more serious for the government than the rioting against the Means Test of half a century before because it occurred in cities throughout the country, rather than in depressed mining areas. London was just as vulnerable as Liverpool, and a crucial contributory factor was the number of young men of south Asian and Caribbean heritage who saw no hope of ever entering employment: opportunities were minimal and they felt particularly discriminated against. The term underclass was increasingly used to describe those who felt themselves to be completely excluded from the return of prosperity to many areas in the late eighties.

By 1987, service industries were offering an alternative means of employment in Britain. Between 1983 and 1987 about one and a half million new jobs were created. Most of these were for women, many of whom were entering employment for the first time, and many of the jobs available were part-time and, of course, lower paid than the jobs lost in primary and secondary industries. By contrast, the total number of men in full-time employment fell still further. Many who had left mining or manufacturing for the service sector also earned far less. By the end of the century there were more people employed in Indian restaurants than in the coal and steel industries combined, but for much lower pay. The economic recovery that led to the growth of this new employment was based mainly on finance, banking and credit. Little was invested in home-grown manufacturing, however, but far more was invested overseas, with British foreign investments rising from 2.7 billion pounds in 1975 to 90 billion in 1985.

At the same time, there was also a degree of re-industrialisation, especially in the Southeast, where new industries employing the most advanced technology were growing. In fact, many industries shed a large proportion of their workforce but, using new technology, maintained or improved their output. These new industries were certainly not confined to the M4 Corridor by the late eighties. By then, Nissan’s car plant in Sunderland had become the most productive in Europe, while Siemens established a microchip plant at Wallsend. However, such companies did not employ large numbers of local workers. Siemens invested more than a billion pounds, but only employed a workforce of about eighteen hundred.

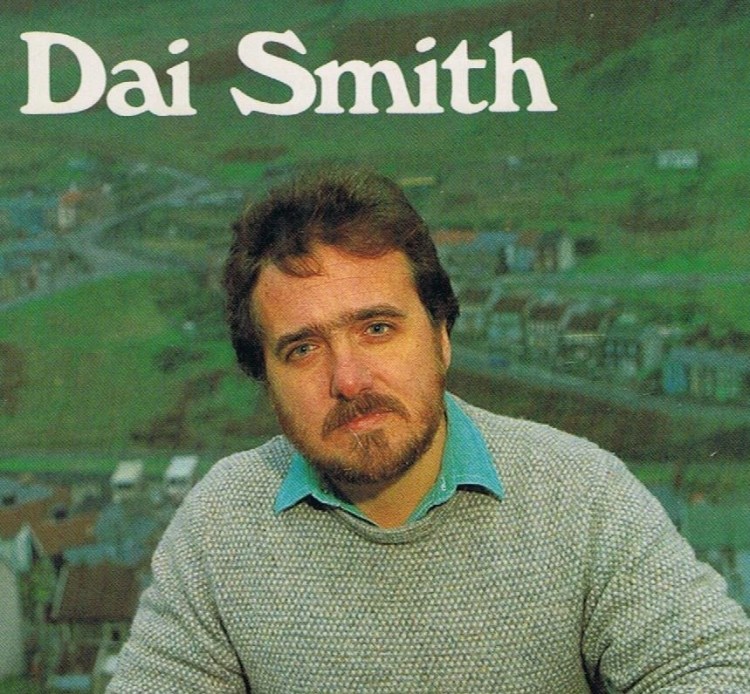

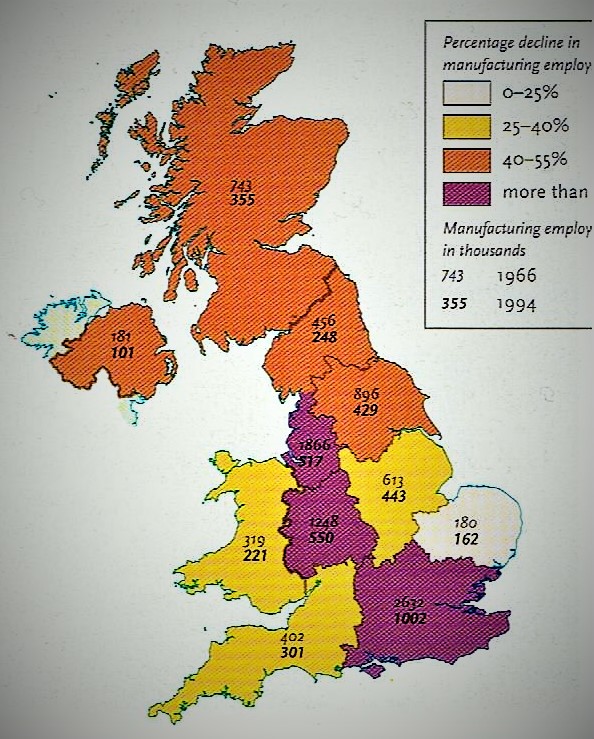

Regionally based industries suffered a dramatic decline during this period. Coal mining, for example, was decimated in the decade following the 1984-85 miners’ strike, not least because of the shift of the electricity-generating industry to other alternative energy sources, especially gas. During the period 1984-87 the coal industry shed a hundred and seventy thousand miners, and there was a further net loss of employment in the coalfields, with the exception of north Warwickshire and south Derbyshire, in the early 1990s. The economic effect upon local communities could be devastating, as the 1996 film Brassed Off accurately shows, with its memorable depiction of the social impact on the Yorkshire pit village of Grimethorpe of the 1992 closure programme. The trouble with the economic strategy followed by the Thatcher government was that South Wales, Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, Tyneside and Clydesdale were precisely those regions that had risen to extraordinary prosperity as part of the British imperial enterprise. Now they were being written off as disposable assets, so what interest did the Scots in particular, but also the Welsh, have in remaining as part of that enterprise, albeit a new corporation in the making?

The Two Britains & the Demise of Thatcher, 1987-1990:

The understandable euphoria over Thatcher and her party winning three successive general elections disguised the fact this last victory was gained at the price of perpetuating a deep rift in Britain’s social geography. Without the Falklands factor to help revive the Union flag, a triumphalist English conservatism was increasingly imposing its rule over the other nations of an increasingly disunited Kingdom. Although originally from Lincolnshire, Thatcher’s constituency was, overwhelmingly, the well-off middle and professional classes in the south of England, where her parliamentary constituency of Finchley lay. Meanwhile, the distressed northern zones of derelict factories, pits, ports and terraced streets were left to rot and rust. People living in these latter areas were expected to lift themselves up by their own bootstraps, retrain for work in the up-and-coming industries of the future and if need be get on Tory Chairman, Norman Tebbitt’s bicycle and move to one of the areas of strong economic growth such as Cambridge, Milton Keynes or Slough, where those opportunities were clustered.

However, little was provided by publicly funded retraining and, if this was available, there was no guarantee of a job at the end of it. The point of the computer revolution was to save labour, not to expand it. In the late 1980s, the north-south divide seemed as intractable as it had any period in the previous six decades, with high unemployment continuing to be concentrated in the declining manufacturing areas of the North and West of the British Isles. That the north-south divide increasingly had a political dimension as well as an economic one was borne out by the 1987 General Election in the UK. Margaret Thatcher’s third majority was largely based on the votes of the South and East of England. North of a line running from the Severn estuary through Coventry and on to the Humber estuary, the long decline of Toryism, especially in Scotland, where it was reduced to only ten seats, was apparent to all observers. At the same time, the national two-party system seemed to be breaking down so that south of that line, the Liberal-SDP Alliance was the main challenger to the Conservatives in many constituencies.

Even though the shift towards service industries was reducing regional economic diversity, the geographical distribution of regions eligible for European structural funds for economic improvement confirmed the continuing north-south divide. The pace of change quickened as a result of the 1987 Single European Act, as it became clear that the UK was becoming increasingly integrated with the European continent. The administrative structure of Britain also underwent major changes by the end of the nineties. The relative indifference of the Conservative ascendancy to the plight of industrial Scotland and Wales had transformed the prospects of the nationalist parties in both countries. In the 1987 election, Scottish and Welsh nationalists, previously confined mainly to middle-class, rural and intellectual constituencies, now made huge inroads into Conservative areas and even into the Labour heartlands of industrial south Wales and Clydeside.

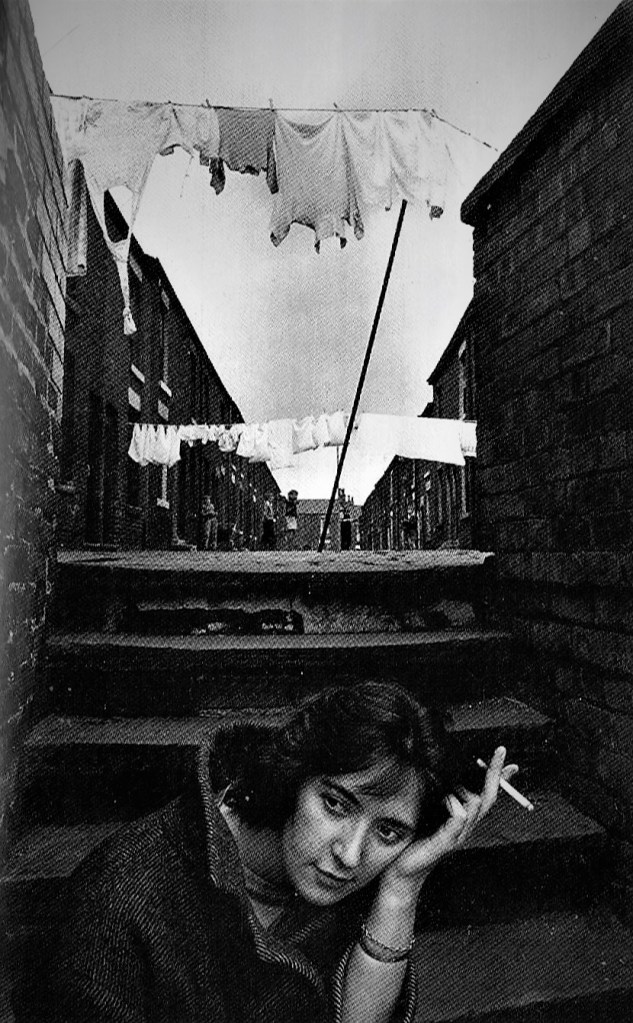

Culturally, the Thatcher counter-revolution ran into something of a cul-de-sac, or rather the cobbled streets of Salford typified in the long-running TV soap opera, Coronation Street. Millions in the old British industrial economy had a deeply ingrained loyalty to the place where they had grown up, gone to school, got married and had their kids; to the pub, their park, and their football team. In that sense at least the Social Revolution of the fifties and sixties had recreated cities and towns that, for all their ups and downs, their poverty and pain, were real communities. Fewer people were willing to give up on Liverpool and Leeds, Nottingham and Derby than the pure laws of the employment marketplace demanded. For many working-class British people, it was their home which determined their quality of life, not the width of their wage packet.

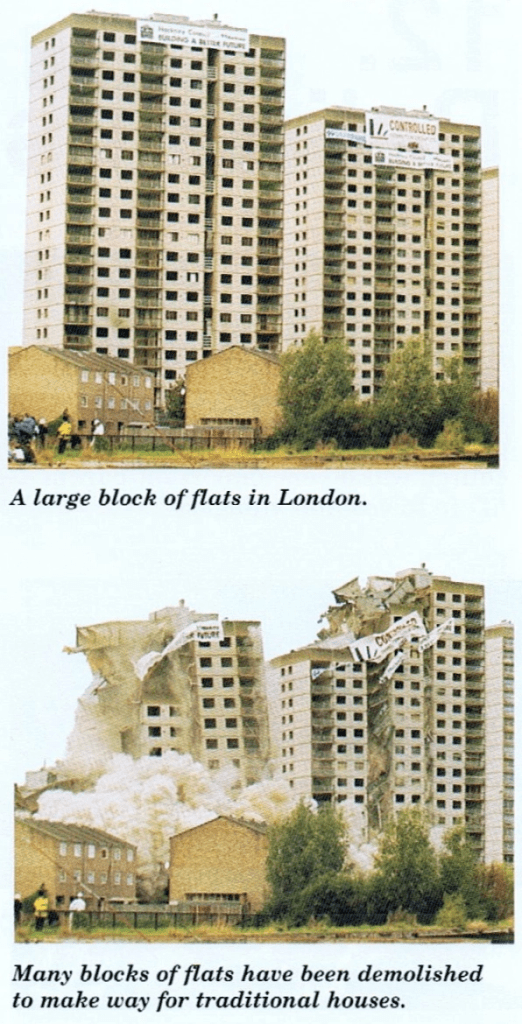

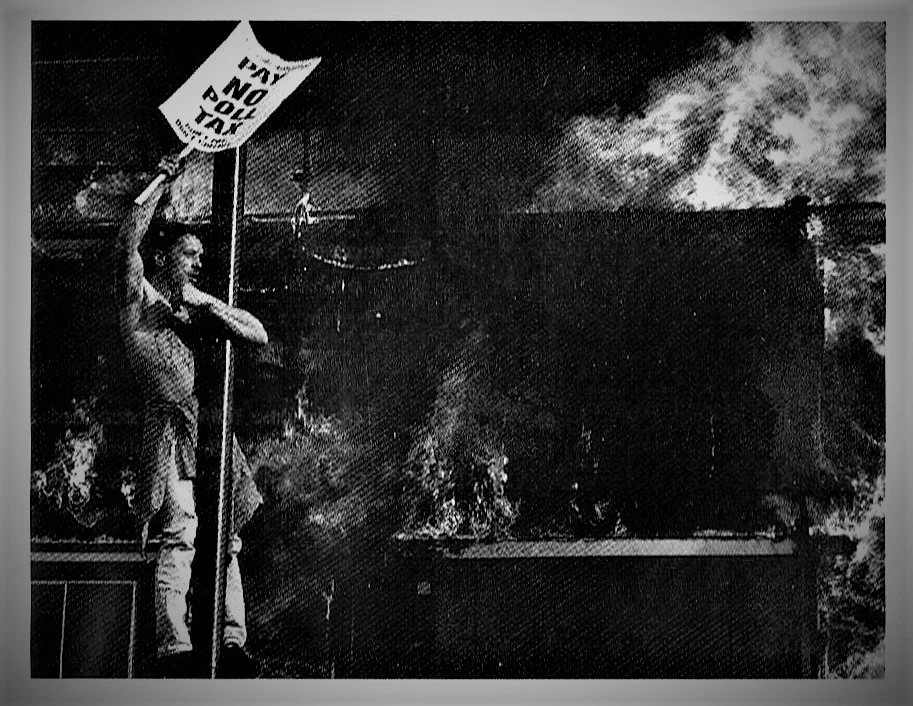

Not everything that the Thatcher government did was out of tune with social reality, however. The sale of council houses created an owner-occupier class which, as Simon Schama has written, corresponded to the long passion of the British to be kings and queens of their own little castles. Sales of remaining state-owned industries, such as the public utility companies, were less successful since the concept of stakeholdership was much less deeply rooted in British traditions, and the mixed fortunes of both these privatised companies and their stocks did nothing to help change customs. Most misguided of all was the decision to call a poll tax imposed on the house and flat owners a community charge, and then to impose it first, as a trial run, in Scotland, where the Tories already had little support. The grocer’s daughter from Grantham thought that it would be a good way of creating a property-owning, tax-paying democracy, where people paid according to the size of their household. This was another mistaken assumption.

Later in 1990, the iron lady was challenged for her leadership of the Party by Michael Heseltine, and although she beat him in the first ballot, the margin was insufficient to prevent a second ballot. With her supporters and cabinet fearing her defeat and humiliation, she felt obliged to step down from the contest. She was then replaced as PM by one of her loyal deputies, John Major, another middle-class anti-patrician, the son of a garden-gnome salesman, apparently committed to family values and a return to basics. In 1990, some EEC leaders thought that Britain was too slow in making decisions. In 1986, President Mitterand had signed an agreement with Margaret Thatcher to build the long-planned Channel Tunnel between France and England. But while the French had pressed ahead with constructing road and high-speed train links to the tunnel, Britain had been slow to act.

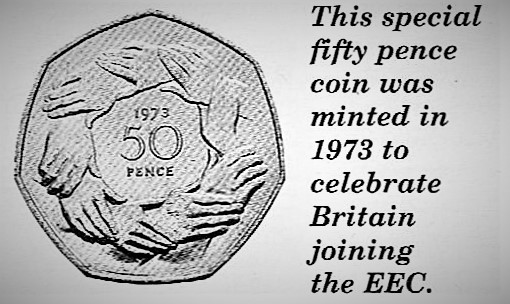

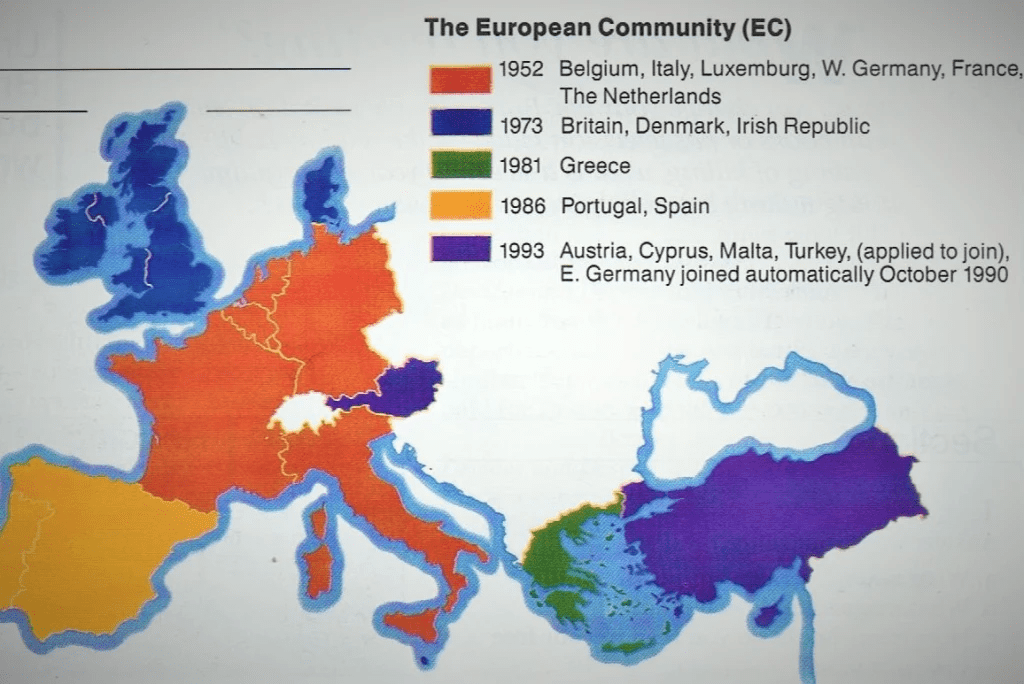

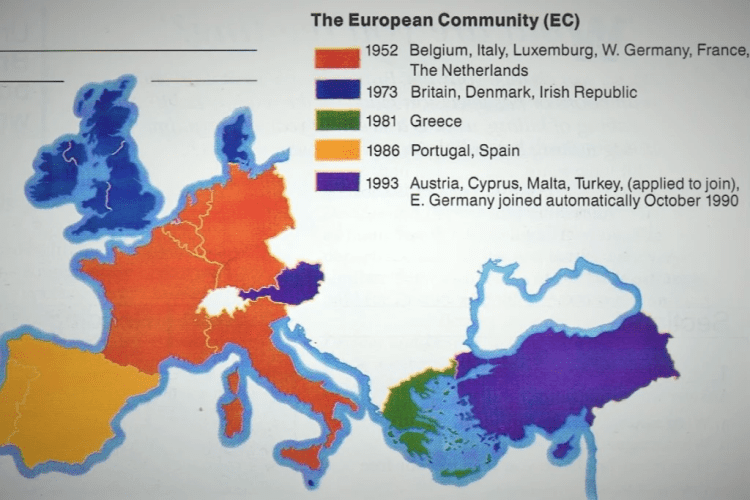

Throughout his time in office, a significant number of Conservative back-bench MPs continued to oppose closer economic and political ties within the EEC, which then became the European Community (EC). Against all the odds, at Maastricht in 1991, he managed to slip Britain out of paying fealty to the EC on most of what was demanded. He and his Chancellor, Norman Lamont, negotiated a special opt-out from the monetary union and managed to have the social chapter excluded from the treaty altogether. For a man with a weak hand, under fire from his own side at home, it was quite an accomplishment. Briefly, he was a hero, hence the cartoons of him wearing his Y-fronts outside his trousers. He described his reception by his own party in the Commons as the modern equivalent of a Roman triumph, quite something for a boy from Brixton.

The Brixton Boy & New Growth, 1992-97:

Soon after his Maastricht triumph, flushed with confidence, Major called the election that most observers thought he must lose. The economy was still in a mess, the poll tax issue so fresh and Neil Kinnock’s Labour Party now so well purged of Militants and well organised that there was a widespread belief that the ‘Thatcher era’ was at an end. But then, Lamont’s pre-election budget came to the rescue of his PM. It proposed cutting the basic rate of income tax by five pence in the pound, which would help people on lower incomes, badly wrong-footing Labour. During the campaign, Major found himself returning to Brixton, complete with a soapbox, which he mounted to address raucous crowds through a megaphone.

On 9th April, Major’s Conservatives won fourteen million votes, more than any party in British political history. It was a great personal achievement for Major, based on voters’ fears of higher Labour taxes. It was also one of the biggest percentage leads since 1945, but the vagaries of the electoral system gave only gave Major a majority of just twenty-one seats.

Never has such a famous victory produced such a rotten result for the winners. Major was back in number ten, but Chris Patten, tipped by many as a future PM, lost his seat in Bath to the Liberal candidate.

Unlike his predecessor and successor as Prime Minister, both of whom won three elections, in a parliamentary system under which greatness is generally related to parliamentary arithmetic, John Major has not gone down as a great leader of his country, though he was far more of a unifying figure than those who went before and came after. Despite its somewhat surprising victory in the 1992 General Election, the Major government ended up being ignominiously overwhelmed by an avalanche of sexual and financial scandals and blunders. Added to this, the ‘Maastricht rebels’ on the Tory back-benches now openly campaigned for Britain to leave the European Community.

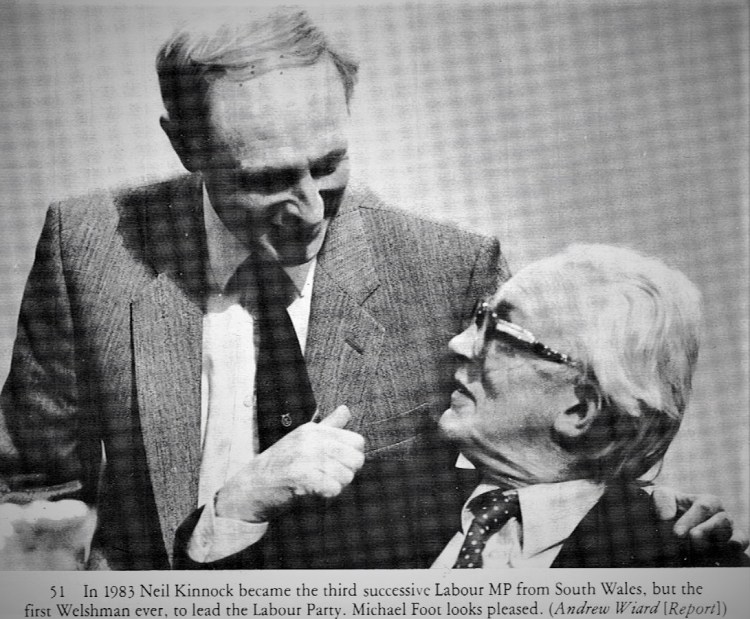

Kinnock was devastated by the 1992 result and quickly left front-line politics, becoming even less of a footnote in parliamentary history than Major, though deserving of an honourable chapter in the history of the Labour Party. Despite his popular mandate, the smallness of his majority meant that Major’s authority in the Commons was steadily chipped away by the Labour Opposition under their less bellicose but more able parliamentary leader, Kinnock’s Scottish Shadow Chancellor, John Smith.

Deindustrialisation & Re-industrialisation into the Nineties:

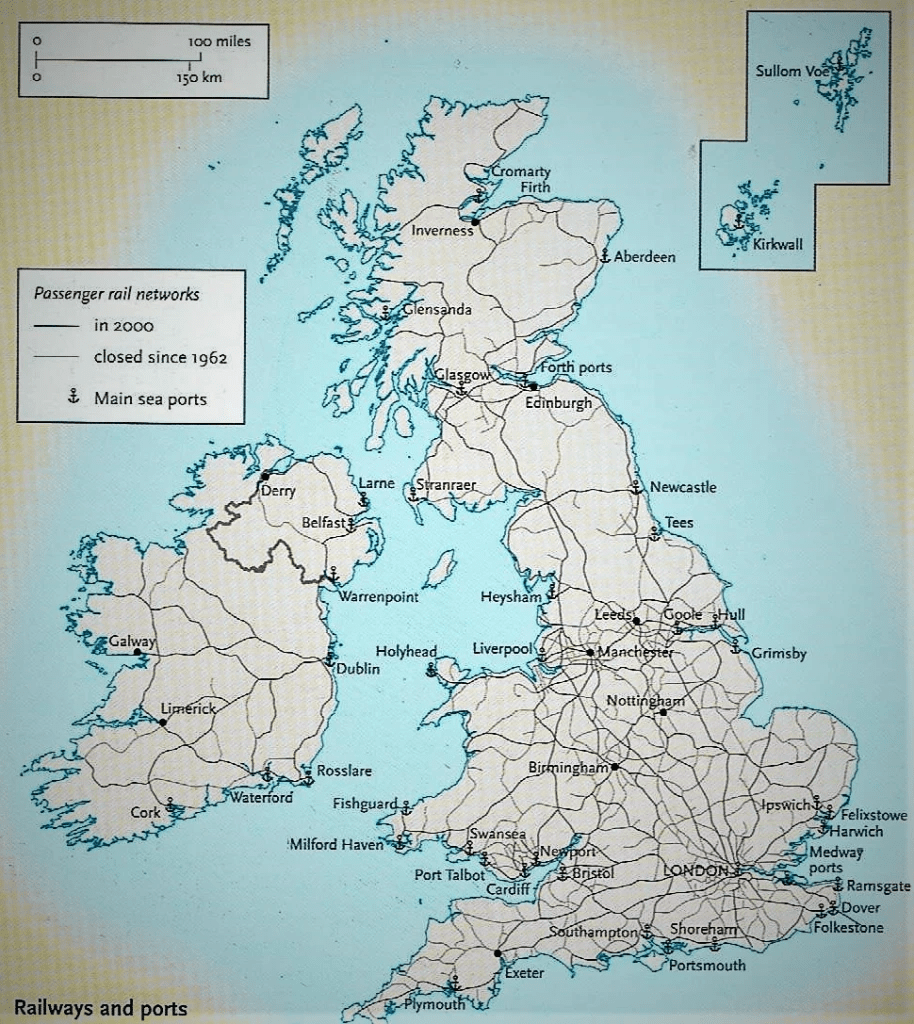

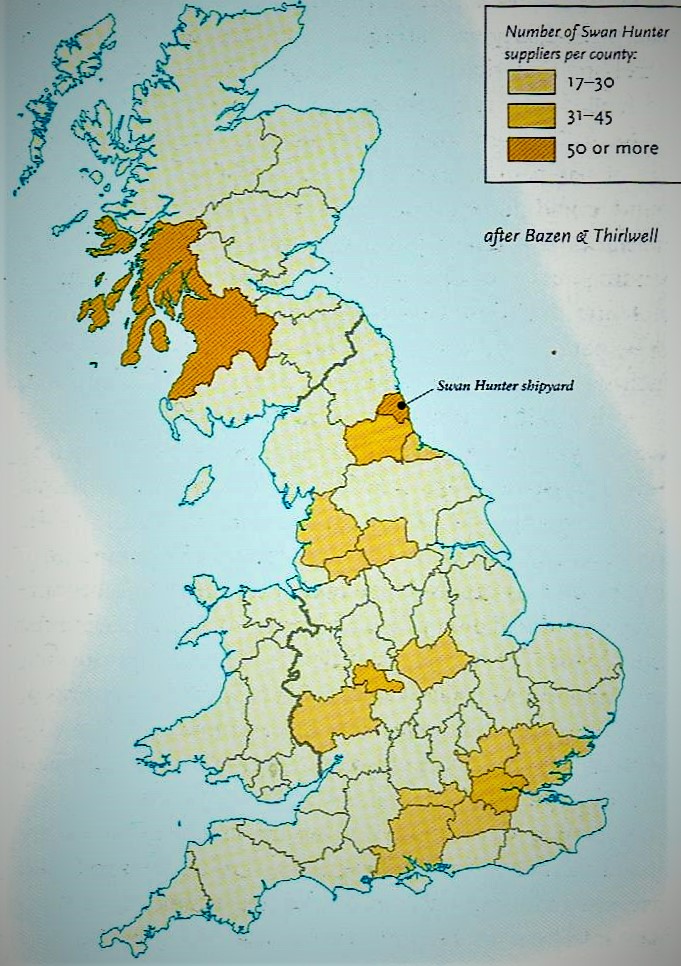

The process of deindustrialisation continued into the nineties with the closure of the Swan Hunter shipyard on the Tyne in May 1993. It was the last working shipyard in the region but failed to secure a vital warship contract. It was suffering the same long-term decline that reduced shipbuilding from an employer of two hundred thousand in 1914 to a mere twenty-six thousand by the end of the century. This devastated the local economy, especially as a bitter legal wrangle over redundancy payments left many former workers without any compensation at all for the loss of what they had believed was employment for life. As the map above shows, the closure’s effects spread far further than Tyneside and the Northeast, which were undoubtedly badly hit by the closure, with two hundred and forty suppliers losing their contracts. The results of rising unemployment were multiplied as the demand for goods and services declined.

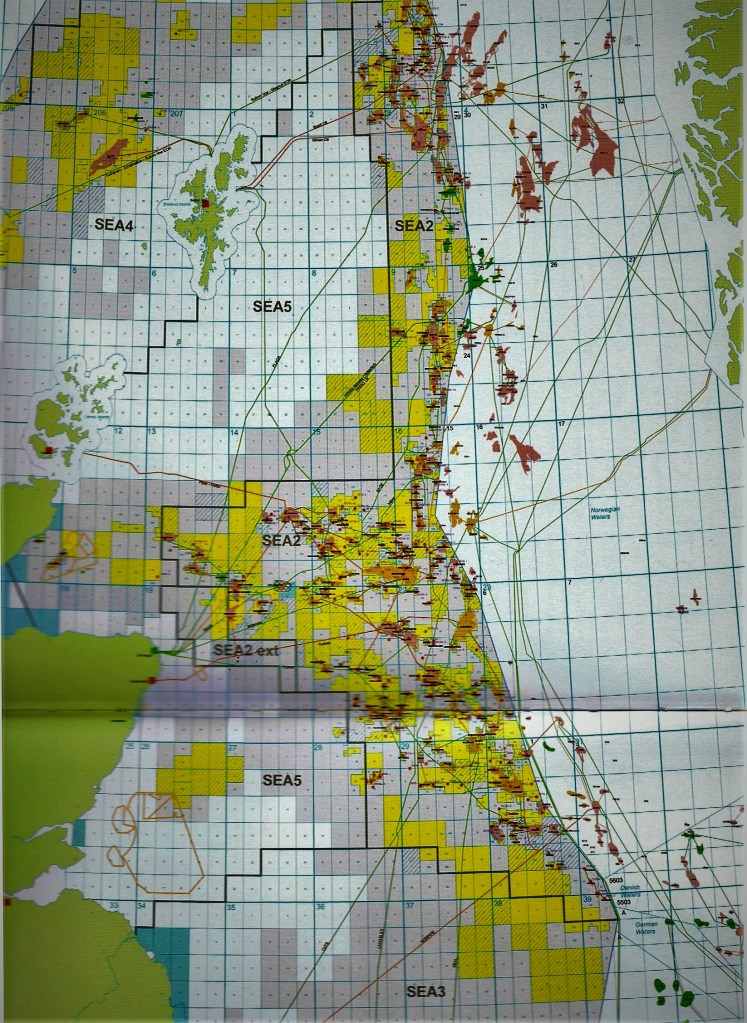

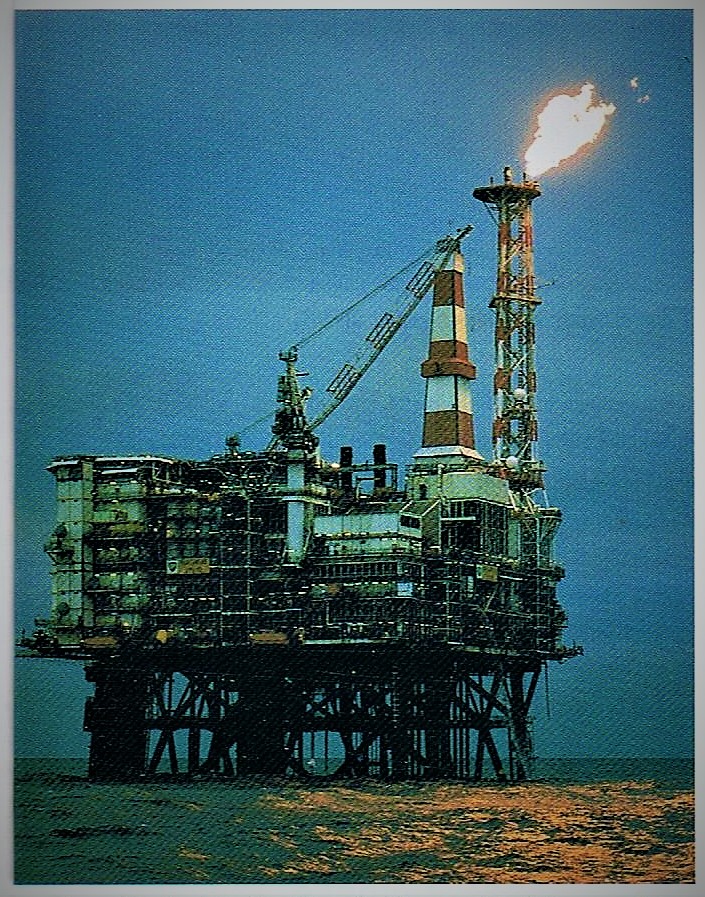

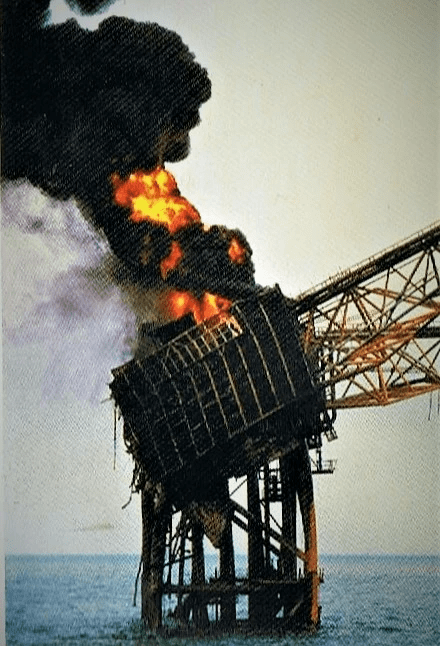

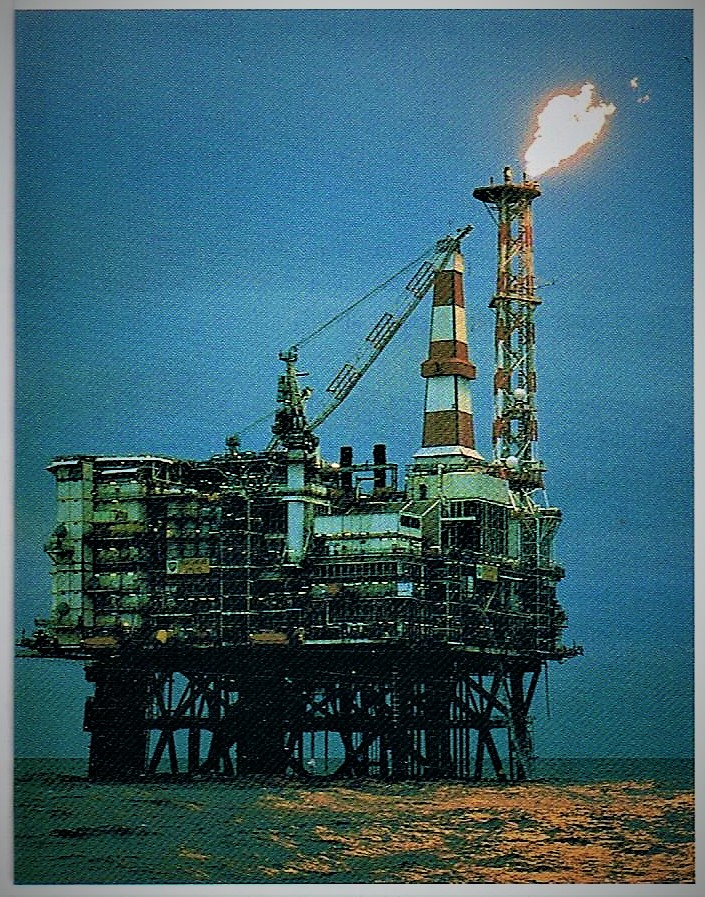

As the map above shows, the closure of Swan Hunter certainly had a widespread impact on Suppliers as far afield as Southampton and Glasgow, as well as in the West Midlands and the Southeast. They lost valuable orders and therefore also had to make redundancies. Forty-five suppliers in Greater London also lost business. Therefore, from the closure of one single, large-scale engineering concern, unemployment resulted even in the most prosperous parts of the country. In the opposite economic direction, the growing North Sea oil industry helped to spread employment more widely throughout the Northeast and the Eastern side of Scotland, with its demands for drilling platforms and support ships, and this benefit was also felt nationally, both within Scotland and more widely, throughout the UK. However, this did little in the short term to soften the blow of the Swan Hunter closure.

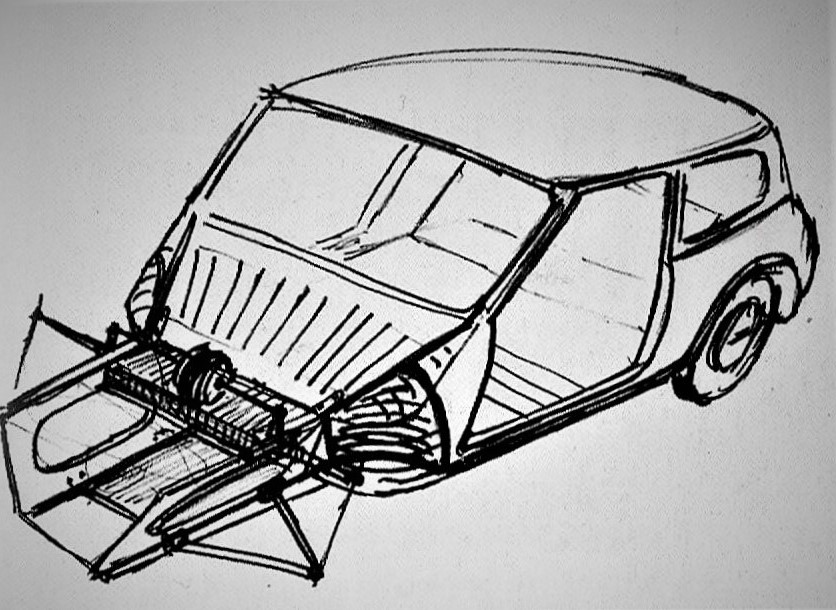

The old north-south divide in Britain seemed to be eroding during the recession of the early 1990s, which hit southeast England relatively hard, but it soon reasserted itself with a vengeance later in the decade as young people moved south in search of jobs and property prices rose. Overall, however, the 1990s were years of general and long-sustained economic expansion. The continued social impact of the decline in coal, steel and shipbuilding was to some extent mitigated by inward investment initiatives. Across most of the British Isles, there was also a continuing decline in the number of manufacturing jobs throughout the nineties. Although there was an overall recovery in the car industry, aided by the high pound in the export market, much of this was due to the new technology of robotics (shown below) which made the industry far less labour-intensive and therefore more productive.

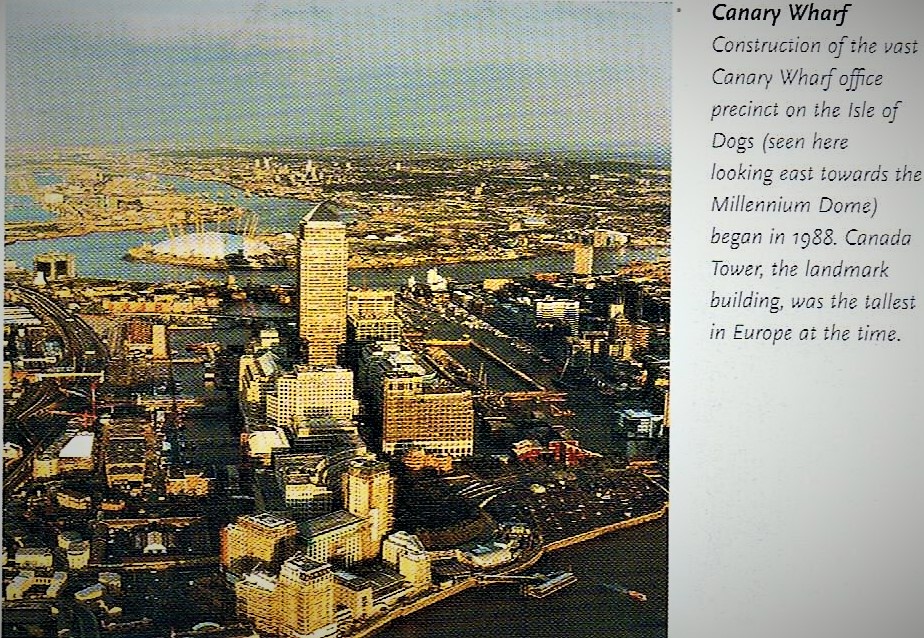

The service sector expanded, however, and general levels of unemployment, especially in Britain, fell dramatically in the 1990s. Financial services saw strong growth, particularly in the London Docklands (pictured below), which saw the transformation of former docks areas into offices and fashionable modern residential developments, with a new focus around the huge Canary Wharf scheme, to the east of the city on the previously isolated Isle of Dogs. On the right is an aerial view of the complex being built in the late 1980s. But although the new development was expected to boost commerce and local businesses.

A decade later, however, many of the buildings were still unoccupied.

In addition, by the end of the decade, the financial industry was the largest employer in northern manufacturing towns like Leeds, which grew rapidly, aided by its ability to offer a range of cultural facilities that helped to attract an array of UK company headquarters. Manchester, similarly, enjoyed a renaissance, particularly in music and football. Manchester United’s commercial success led it to become the world’s largest sports franchise. Edinburgh’s banking and finances sector also expanded. Other areas of the country were helped by their ability to attract high technology industry. Silicon Glen in central Scotland was, by the end of the decade, the largest producer of computer equipment in Europe. Computing and software design was also one of the main engines of growth along the silicon highway of the M4 Corridor west of London. But areas of vigorous expansion were not necessarily dominated by new technologies. The economy of East Anglia, especially Cambridgeshire, had grown rapidly in the 1980s and continued to do so throughout the 1990s. While Cambridge itself, aided by the university-related science parks, fostered high-tech companies, especially in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, expansion in Peterborough, for instance, was largely in low-tech areas of business services and distribution.

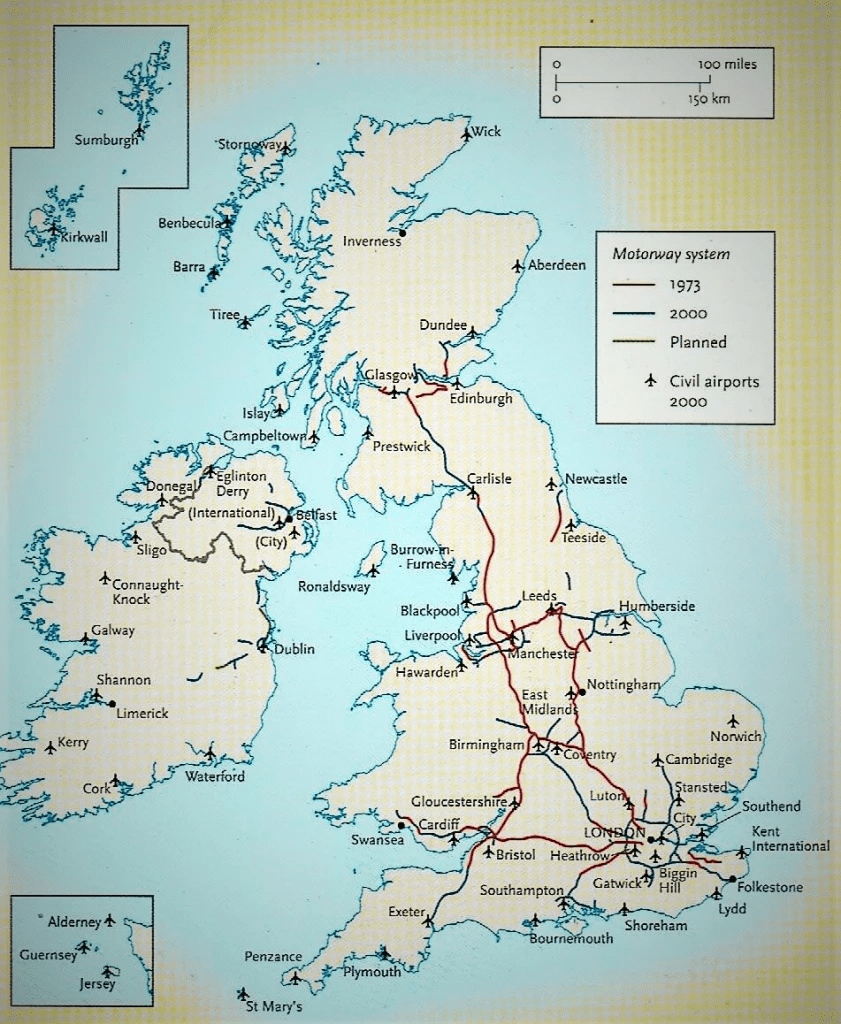

Getting around Britain was, at last, getting easier. By 1980 there were nearly one and a half thousand miles of motorway in Britain. In the last twenty years of the century, the stretching of the congested motorway network to just over two thousand miles mostly involved the linking of existing sections. Motorway building and airport development were delayed by lengthy public enquiries and well-organised public protests. Improving transport links were seen as an important means of stimulating regional development as well as combating local congestion. Major road developments in the 1990s included the completion of the M25 orbital motorway around London, the Skye bridge and the M40 link between London and Birmingham. However, despite this construction programme, congestion remained a problem: the M25 was labelled the largest car park on the planet, while average traffic speeds in central London fell to only ten miles per hour in 2001, a famous poster on the underground pointing out that this was the same average speed as in 1901. Environmental concerns became an important factor in limiting further expansion of both roads and runways and in a renewed focus on improving the rail network both between regions and within them.

Improvements to public transport networks tended to be concentrated in urban centres, such as the light rail networks in Manchester, Sheffield and Croydon. At the same time, the migration of some financial services and much of the Fleet Street national press to major new developments in London’s Docklands prompted the development of the Docklands Light Railway and the Jubilee line extension, as well as some of the most expensive urban motorway in Europe. Undoubtedly, the most important transport development was the Channel Tunnel rail link from Folkestone to Calais, completed in 1994. By the beginning of the new millennium, millions of people had travelled by rail from London to Paris in only three hours.

The development of Ashford in Kent, following the opening of the Channel Tunnel rail link, provides a good example of the relationship between transport links and general economic development. The railway had come to Ashford in 1842 and railway works were established in the town. This was eventually run down and closed between 1981 and 1993, but this did not undermine the local economy. Instead, Ashford benefited from the Channel Tunnel rail link, which made use of the old railway lines running through the town, and its population actually grew by ten per cent in the 1990s. The completion of the Tunnel combined with the M25 London orbital motorway, with its M20 spur, gave the town an international catchment area of some eighty-five million people within a single day’s journey.

This, together with the opening of Ashford International railway station as the main terminal for the rail link to Europe, attracted a range of engineering, financial, distribution and manufacturing companies. Fourteen business parks were opened in and around the town, together with a science park owned by Trinity College, Cambridge, and a popular outlet retail park on the outskirts of the town. By the beginning of the new millennium, the Channel Tunnel had transformed the economy of Kent. Ashford is closer to Paris and Brussels than it is to Manchester and Sheffield, both in time and distance. By the beginning of this century, it was in a position to be part of a truly international economy.

Even the historic market relocated to Orbital Park to the South of the town, reflecting in microcosm a national trend towards siting not only industrial estates but also retail parks on the edge of towns.

New Labour & The Renewal of the United Kingdom, 1997-2002:

In a 1992 poll in Scotland, half of those asked said that they were in favour of independence within the European Union. The enthusiasm the Scottish National Party discovered in the late 1980s for the supposed benefits that would result from independence in Europe may help to explain its subsequent revival. In the General Election of the same year, however, with Mrs Thatcher and her poll tax having departed the political scene, there was a minor Tory recovery north of the border. Five years later this was wiped out by the Labour landslide of 1997 when all the Conservative seats in both Scotland and Wales were lost. Nationalist political sentiment grew in Scotland and to a lesser extent in Wales. In 1999, twenty years after the first devolution referenda, further votes led to the setting up of a devolved Parliament in Edinburgh, Wales got an Assembly in Cardiff, and Northern Ireland had a power-sharing Assembly again at Stormont near Belfast. In 2000, an elected regional assembly was established for Greater London, the area covered by the inner and outer boroughs in the capital, with a directly elected Mayor. This new authority replaced the Greater London Council which had been abolished by the Thatcher Government in 1986 and was given responsibility for local planning and transport.

The devolution promised and instituted by Tony Blair’s new landslide Labour government did seem to take some of the momenta out of the nationalist fervour, but apparently at the price of stoking the fires of English nationalism among Westminster Tories, resentful at the Scots and Welsh having representatives in their own assemblies as well as in the UK Parliament. Only one Scottish seat was regained by the Tories in 2001. In Scotland at least, the Tories became labelled as a centralising, purely English party.

After the 1992 defeat, Blair had made a bleak public judgement about why Labour had lost so badly. The reason was simple: Labour has not been trusted to fulfil the aspirations of the majority of people in the modern world. As shadow home secretary he began to put that right, promising to be tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime. He was determined to return his party to the common-sense values of Christian Socialism, also influenced by the mixture of socially conservative and economically liberal messages used by Bill Clinton and his New Democrats. So too was Gordon Brown but as shadow chancellor, his job was to demolish the cherished spending plans of his colleagues. Also, his support for the ERM (the EU’s Exchange Rate Mechanism) made him ineffective when Major and Lamont suffered their great defeat. By 1994, the Brown-Blair relationship was less strong than it had been, but they visited the States together to learn the new political style of the Democrats which, to the advantage of Blair, relied heavily on charismatic leadership. Back home, Blair pushed John Smith to reform the party rulebook, falling out badly with him in the process. Media commentators began to tip Blair as the next leader, and slowly but surely, the Brown-Blair relationship was turning into a Blair-Brown one.

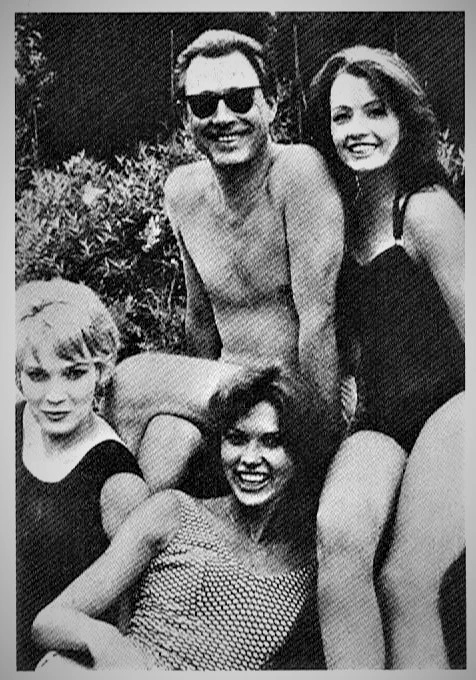

This photo was taken at the Labour Conference in 2005, by which time neither could disguise their personal enmity.

When it arrived, the 1997 General Election demonstrated just what a stunningly efficient and effective election-winning team Tony Blair led, comprising those deadly masters of spin, Alistair Campbell and Peter Mandelson. ‘New Labour’ as it was now officially known, won 419 seats, the largest number ever for the party and comparable only with the seats won by the National Government of 1935. Its Commons majority was also a modern record, with 179 seats, thirty-three more than Attlee’s landslide majority of 1945. The swing of ten per cent from the Conservatives was another post-war record, roughly double that which the 1979 Thatcher victory had produced in the opposite direction. But the turn-out was very low, at seventy-one per cent the lowest since 1935. Labour had won a famous victory but nothing like as many actual votes as John Major had won five years earlier. But Blair’s party also won heavily across the south and in London, and in parts of Britain that it had been unable to reach or represent in recent times.

It had also a far more diverse offer of candidates, especially in terms of gender. A record number of women were elected to Parliament, 119, of whom 101 were Labour MPs, nicknamed Blair’s babes at the time. Despite becoming one of the first countries in the world to have a female prime minister, in 1987 there were just 6.3% of women MPs in government in the UK, compared with ten per cent in Germany and about a third in Norway and Sweden. Only France came below the UK with 5.7%. Before the large group of female MPs joined her in 1997, Margaret Hodge (pictured below, c.1992) had already become MP for Barking in a 1994 by-election. While still a new MP, Hodge had endorsed the candidature of Tony Blair, a former Islington neighbour, for the Labour Party leadership, and was appointed Junior Minister for Disabled People in 1998. Before entering the Commons, she had been Leader of Islington Council and had not been short of invitations from constituencies to stand in the 1992 General Election. She had turned these offers down, citing her family commitments:

“It’s been a hard decision; the next logical step is from local to national politics and I would love to be part of a Labour government influencing change. But it’s simply inconsistent with family life, and I have four children who mean a lot to me.

“It does make me angry that the only way up the political ladder is to work at it twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. That’s not just inappropriate for a woman who has to look after children or relatives, it’s inappropriate for any normal person.

“The way Parliament functions doesn’t attract me very much. MPs can seem terribly self-obsessed, more interested in their latest media appearance than in creating change.”

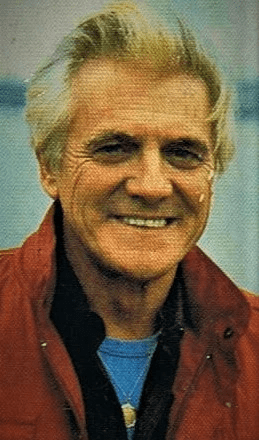

As the sun came up on a jubilant, celebrating Labour Party returning to power after an eighteen-year absence, there was a great deal of Bohemian rhapsodizing about a new dawn for Britain. Alistair Campbell (pictured above, right) had assembled crowds of party workers and supporters to stand along Downing Street waving union flags as the Blairs strode up to claim their victory spoils. Briefly, at least, it appeared that the whole country had turned out to cheer the champions. The victory was due to a small group of self-styled modernisers who had seized the Labour Party and made it a party of the ‘left and centre-left’, at least for the time being, though by the end of the following thirteen years, and after two more elections, they had taken it further to the centre-right than anyone expected on that balmy early summer morning; there was no room for cynicism amid all the euphoria. Labour was rejuvenated, and that was all that mattered.

Blair needed the support and encouragement of admirers and friends who would coax and goad him. There was Mandelson, the brilliant but temperamental former media boss, who had now become an MP. Although adored by Blair, he was so mistrusted by other members of the team that Blair’s inner circle gave him the codename ‘Bobby’ (as in Bobby Kennedy). Alistair Campbell, Blair’s press officer and attack dog was a former journalist and natural propagandist, who had helped orchestrate the campaign of mockery against Major. Then there was Anji Hunter, the contralto charmer who had known Blair as a young rock singer and was his best hotline to middle England. Derry Irvine was a brilliant Highlands lawyer who had first found a place in his chambers for Blair and his wife, Cherie Booth. He advised on constitutional change and became Lord Chancellor in due course. These people, with the Brown team working in parallel, formed the inner core. The young David Miliband, son of a well-known Marxist philosopher, provided research support. Among the MPs who were initially close were Marjorie ‘Mo’ Mowlem and Jack Straw, but the most striking aspect about ‘Tony’s team’ was how few elected politicians it included.

The small group of people who put together the New Labour ‘project’ wanted to find a way of governing which helped the worse off, particularly by giving them better chances in education and to find jobs, while not alienating the mass of middle-class voters. They were extraordinarily worried by the press and media, bruised by what had happened to Kinnock, whom they had all worked with, and ruthlessly focused on winning over anyone who could be won. But they were ignorant of what governing would be like. They were able to take power at a golden moment when it would have been possible to fulfil all the pledges they had made. Blair had the wind at his back as the Conservatives would pose no serious threat to him for many years to come. Far from inheriting a weak or crisis-ridden economy, he was actually taking over at the best possible time when the country was recovering strongly but had not yet quite noticed that this was the case. Blair had won by being ruthless, and never forgot it, but he also seemed not to realise quite what an opportunity ‘providence’ had handed him.

How European were the British in the Nineties?:

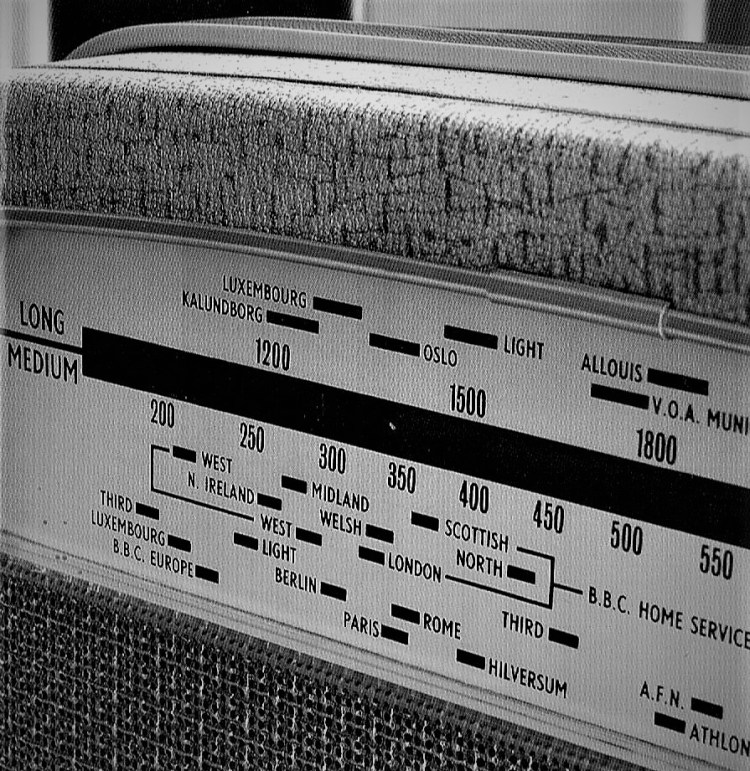

Transport policy was only one of the ways in which the EU increasingly came to shape the geography of the British Isles in the 1990s. In 1992, British people in general were far more positive about membership in the European Community (EC) than they were twenty years later, especially those employed in transport. Roy Clementson, a fifty-nine-year-old long-distance truck driver for more than thirty years was interviewed about his attitude to driving in the EC. He said that he preferred driving in Europe to the UK because the facilities were better:

“It’s easier to get a shower and there are far more decent places to eat, especially in France. I’m not one of those drivers who won’t eat anything except sausage, eggs, beans and chips. I like French food and I like the prices they charge. In France, if you look around, you can get a five-course meal and as much wine as you can drink for Ł5.50. In Italy, the food is very good, but it is more expensive: more like ten pounds per meal.

“I can assure you all the drivers would welcome a single European currency. It would be much better if you didn’t have to change money all the time. I’ve got nothing against the Royal Family, but not having coins with the Queen’s picture on doesn’t make any difference to me.

” I don’t see any disadvantages of going into Europe. I think the French and Germans have a better standard of living than we do. I recently saw a beautiful four-bedroomed house that cost about Ł75,000 in France. Now my house is worth more than that, but it’s only about one-third the size.

“People talk about our being ruled by Brussels; well, I think we could pick up a lot of good ideas. I wouldn’t say I feel European, but I don’t agree with people who have this attitude that we’re somehow better than they are. We have a lot to learn.”

The Independent.

Transport policy became a key factor in the creation of the new EU administrative regions of Britain between 1994 and 1999, as shown on the map below. At the same time, a number of British local authorities opened offices in Brussels for lobbying purposes. The European connection proved less welcome in other quarters, however. Fishermen, particularly in Devon and Cornwall and along the East coast of England and Scotland, felt themselves the victims of the Common Fisheries Policy quota system. A strong sense of Euroscepticism developed in parts of southern England in particular, fuelled by a mixture of concerns about sovereignty and economic policy. Nevertheless, links with Europe had been growing, whether via the Channel Tunnel, the connections between the French and British electricity grids, or airline policy, as were the number of policy decisions shaped by the EU.

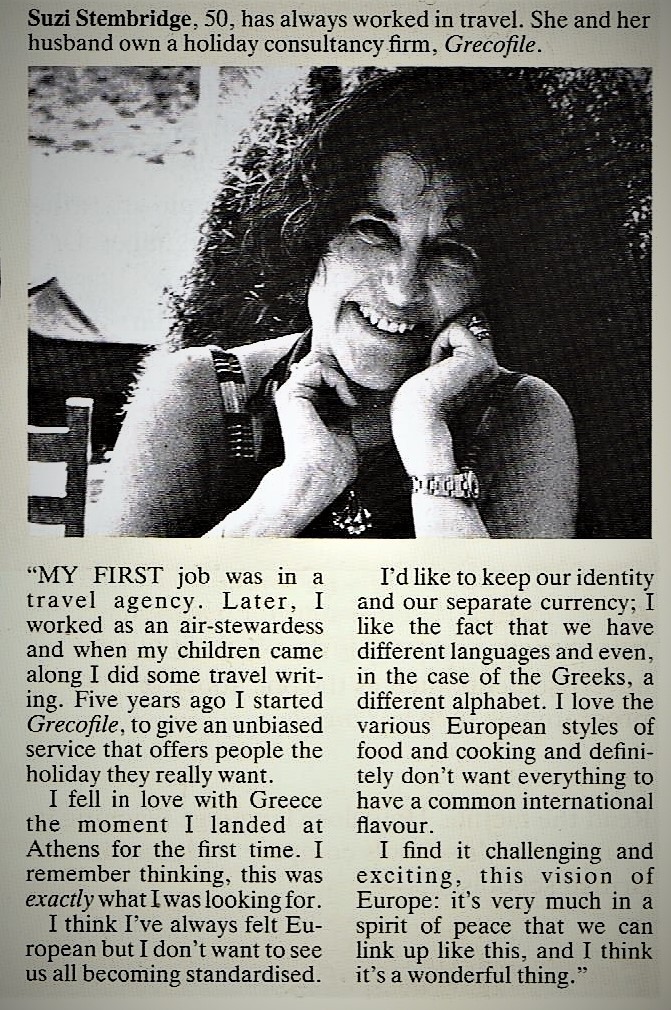

With these better transport links, international travel became easier and cheaper for ordinary Britons. In particular, the cost of air travel began to fall, with the establishment of budget airlines, package holidays were affordable for families, and more independent, longer-term cultural links were forged between individuals, families and organisations. Holiday consultant Suzi Stembridge, also featured in the article from The Independent, exemplified many of these developments and the changing attitudes to a growing European community they brought:

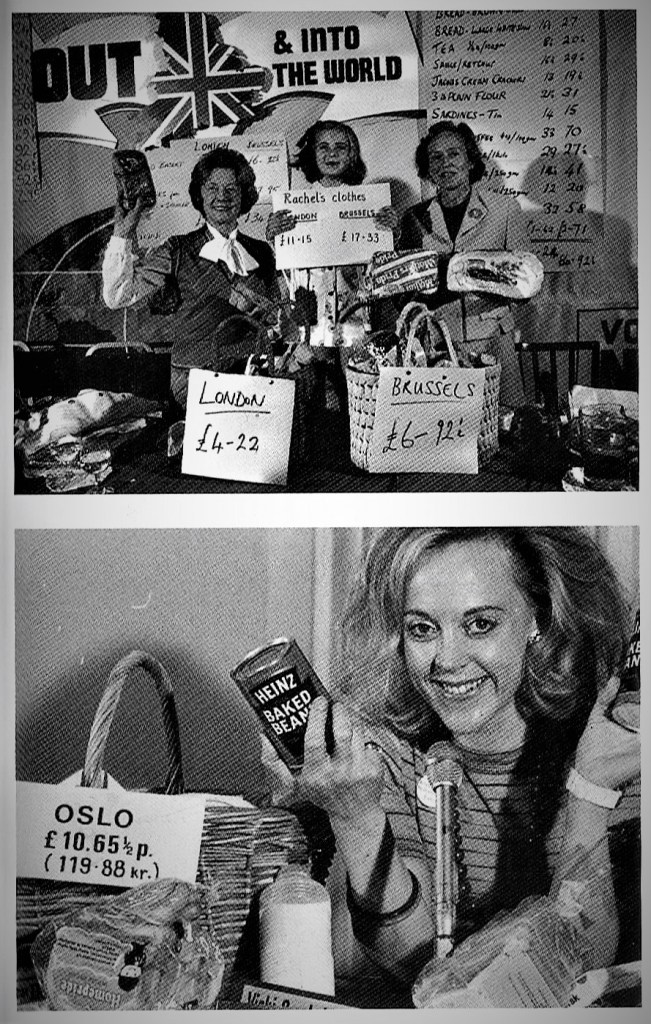

Suzi Stembridge was clearly enthusiastic about the vision of a new Europe that membership of the European Community offered. It seems that, with the exception of fishermen and some Tory Westminster politicians, the majority of British people were becoming more European and more enthusiastic about EC membership, especially those involved in transport and travel, education, entertainment and culture. In addition, they were no longer concerned about its effects on food prices and the cost of living, as many had been at the time of the 1975 Referendum. They could see from their own experience that, if anything, the standard of living on the continent was higher than that in Britain, and that the quality of life was, in many ways, better. On the other hand, they were not so enthusiastic about Britain joining a single currency and wanted each country to be able to keep its own identity. They may not have felt as ‘truly European’ as people on the continent, but neither were they, at that point (the time of the Maastricht Treaty negotiation and implementation), opposed to, or even sceptical of membership of the European institutions.

The Growth of Celebrity Culture:

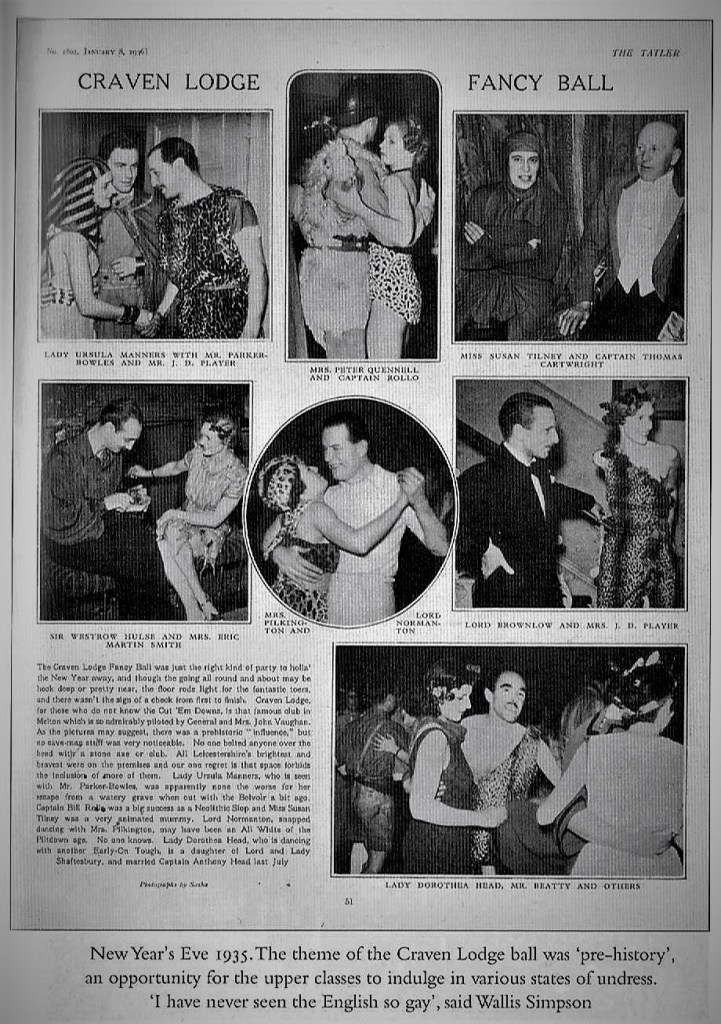

In 1997, Tony Blair arrived in power in a country with a revived fashion for celebrities, offering a few politicians new opportunities, though often at a high cost to their privacy and family lives. It was not until 1988 that the full shape of modern celebrity culture had become apparent. That year had seen the publication of the truly modern glossy glamour magazines when Hello! was launched. Its successful formula was soon copied by OK! from 1993 and many other magazines soon followed suit, to the point where the yards of coloured ‘glossies’ filled the newsagents’ shelves in every town and village in the country. Celebrities were paid handsomely for being interviewed and photographed in return for coverage which was always fawningly respectful and never hostile. The rich and famous, no matter how flawed in real life, were able to shun the mean-minded sniping of the ‘gutter press’, the tabloid newspapers. In the real world, the sunny, airbrushed world of Hello! was inevitably followed by divorces, drunken rows, accidents and ordinary scandals. But people were happy to read good news about these beautiful people even if they knew that there was more to their personalities and relationships than met the eye.

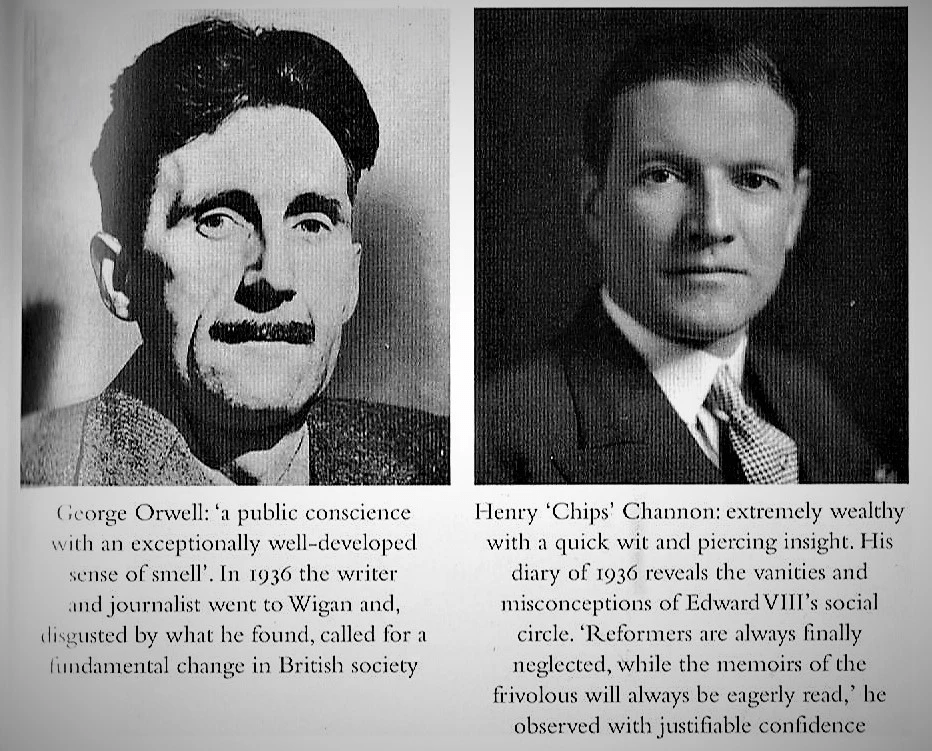

In the same year that Hello! went into publication, ITV also launched its most successful of the daytime television shows, This Morning, hosted from Liverpool by Richard Madeley and Judy Finnigan, providing television’s celebrity breakthrough moment. A new form of television, Reality Television, was created that featured ‘ordinary’ people rather than actors or celebrities. This idea was developed from the fly-on-the-wall documentaries and talent shows of previous decades. The programme Big Brother, taking its title from the phrase in George Orwell’s novel 1984, ‘Big brother is watching you,’ was first aired in 1999. Members of the public were locked in a house and observed on camera. This turned ordinary members of the public into media stars overnight, though mostly only for a short time afterwards. The pop ‘agent’ Simon Cowell (b. 1959) created Pop Idol in 2001. Young singers were auditioned and then coached to become pop stars, eliminated one by one until a winner was chosen and then given a recording contract. This format continued into the X-factor and Britain’s Got Talent which included acts other than pop singers and was open to people of all ages and backgrounds. These programmes were ‘interactive,’ inviting viewers to vote by phone.

Just as in sixties Britain, in the nineties Britain started producing music that became popular all over the world. Boy bands included Take That, including Robbie Williams and Gary Barlow who later had solo singing careers. Unlike The Beatles, however, these ‘bands’ had to rely on backing instrumentalists, however. Girl bands like The Spice Girls promoted a fashion for “girl power” and one of them, Victoria Adams, ‘Posh Spice’, married the footballer David Beckham. Together, they became a notable celebrity couple in Britain and around the world.

There had been a feeling that life under John Major’s government was rather dull, and that its politics was full of men in dark grey suits. Tony Blair’s victory in 1997 brought a change of mood in which it was ‘cool’ to be British again. The Blair government captured this mood, inviting pop stars, sporting heroes and other celebrities to Downing Street for ‘photo opportunities’ and encouraging a ‘rebranding’ of Britain as ‘Cool Britannia’.

Monarchy as the Indispensable Marker of British Identity, 1981-2002:

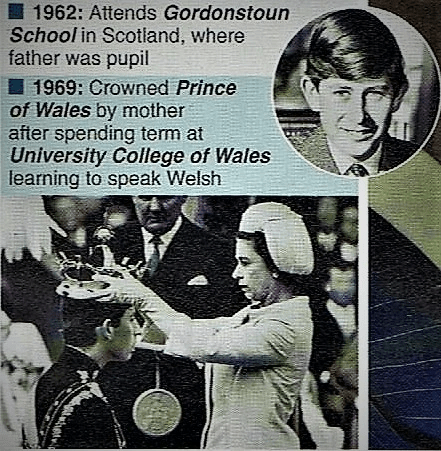

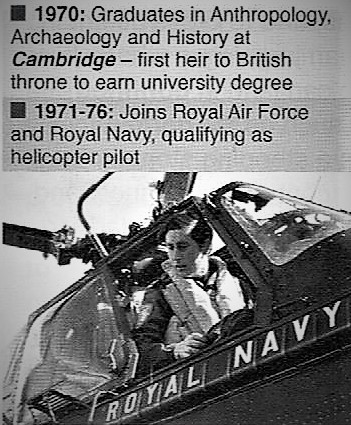

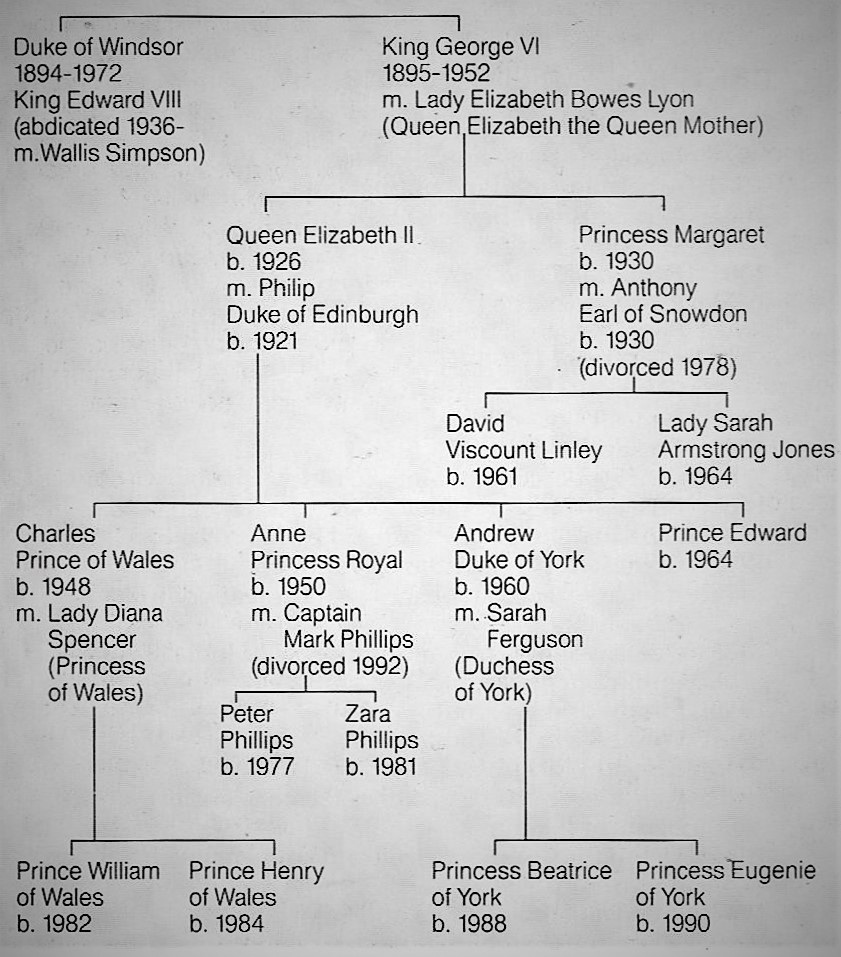

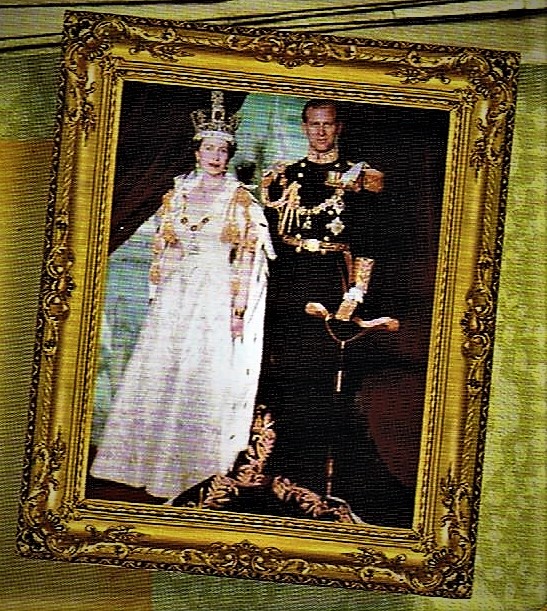

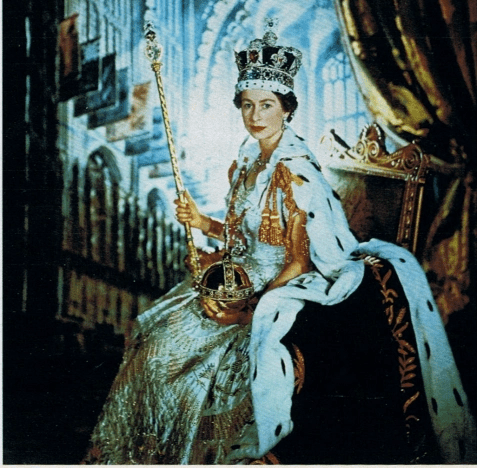

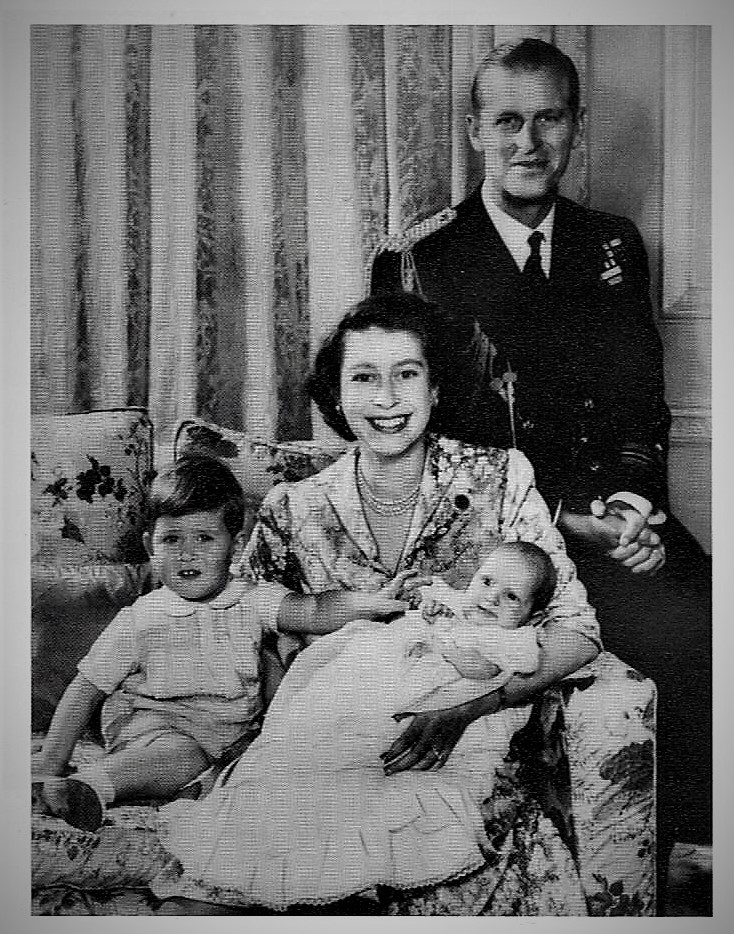

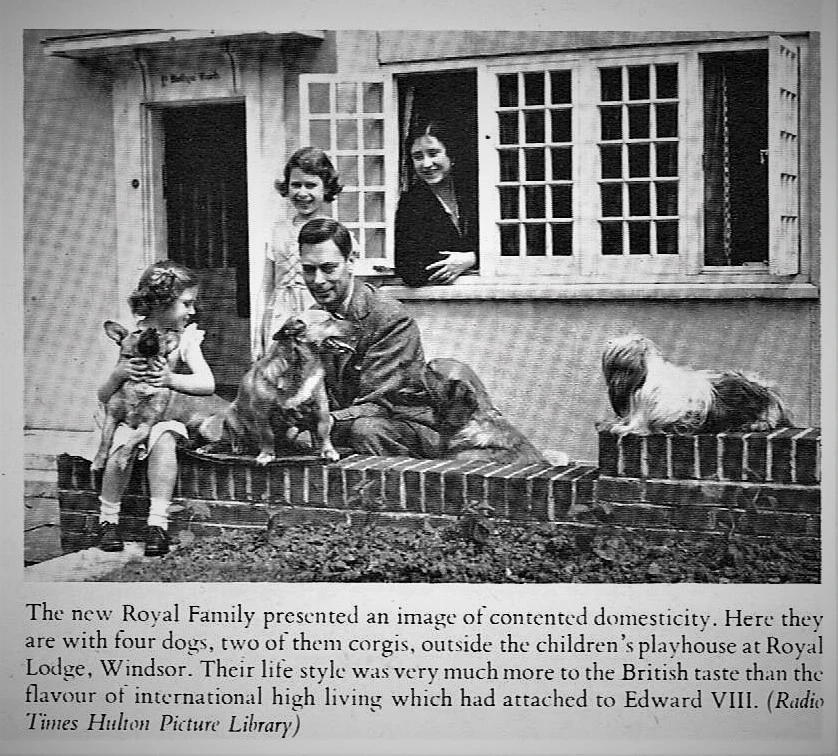

By the early 1990s, another indispensible marker of British identity, the monarchy, began to look tired, under the strain of being simultaneously a ceremonial and familial institution. Behind the continuing hard work and leadership of HM Queen Elizabeth and her Consort, Philip, and the Queen Mother, there were growing signs that the younger generation of the Royal Family, including the heir, Charles, Prince of Wales, was struggling to live up to the high standards set by the older ones. The seeds of these problems were sown at the beginning of the previous decade, if not earlier, with the deliberate development of the monarchy into a ‘family’ institution.

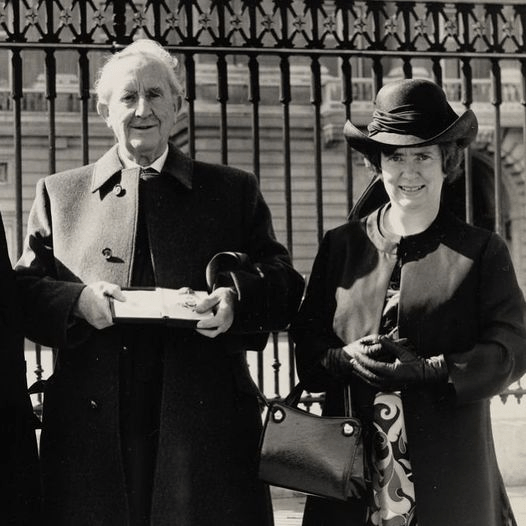

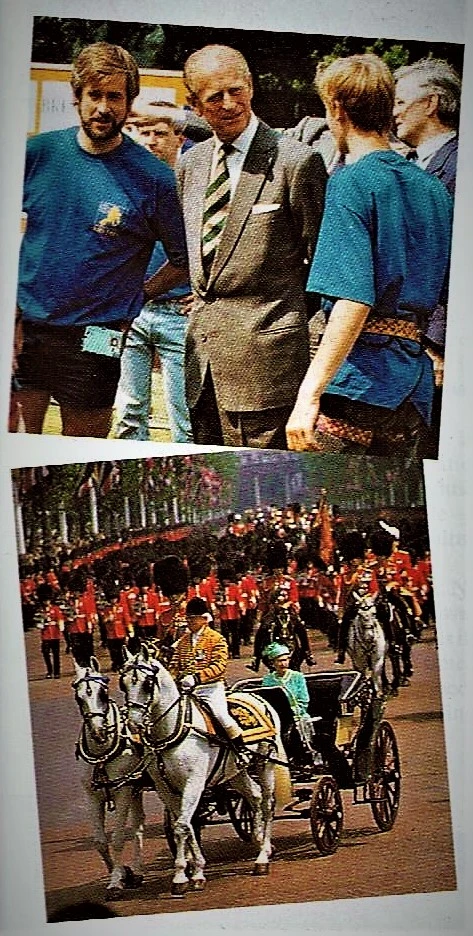

Top: The Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip, was given his title after his marriage to the then Princess Elizabeth in 1947. The Duke took a great deal of interest in the achievements of young people – in 1956 he founded the Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme (through which awards are made to young people aged 14-21 for enterprise, initiative and achievement.

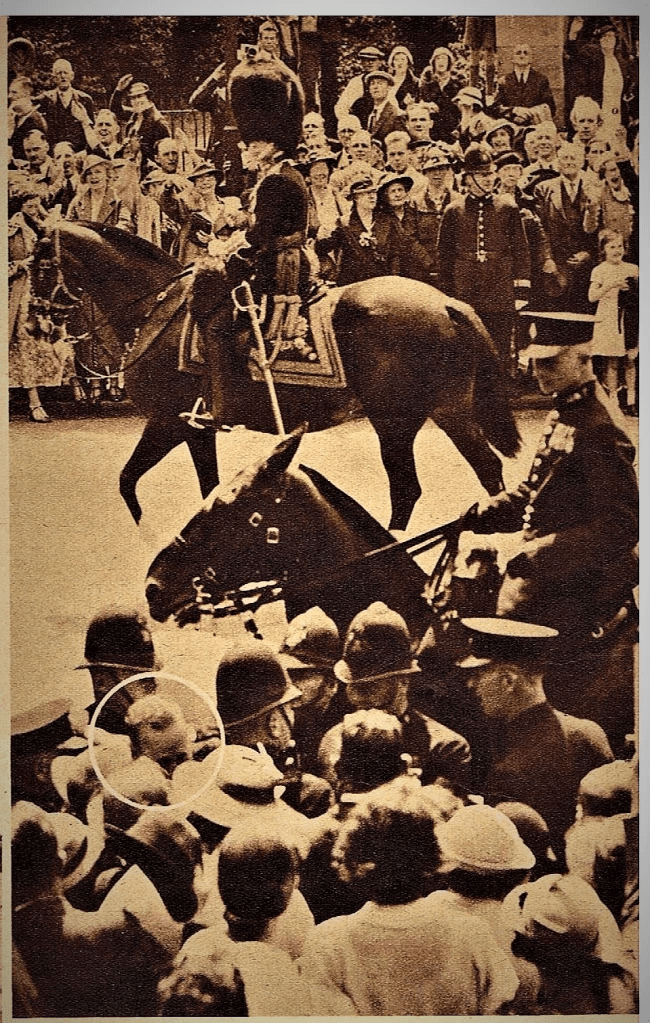

Below: The Queen’s Official Birthday, the second Saturday in June, is marked by the Trooping of the Colour, a ceremony during which the regiments of the Guards Division and the Household Cavalry parade (troop) the regimental flag (colour) before the sovereign.

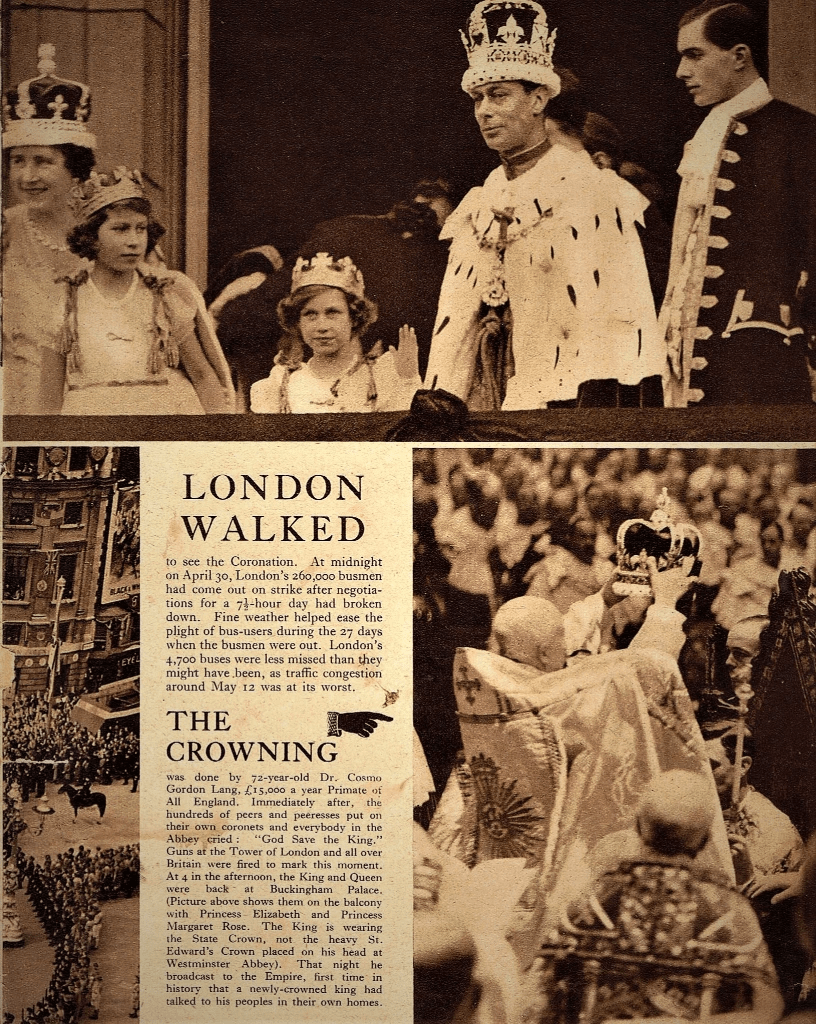

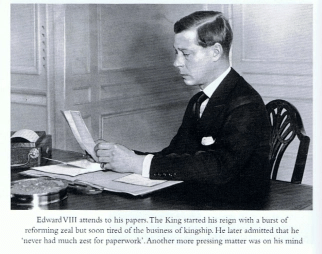

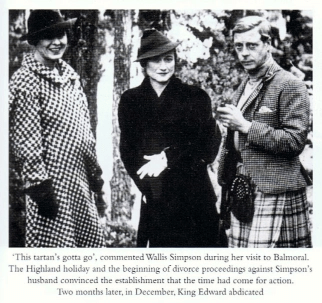

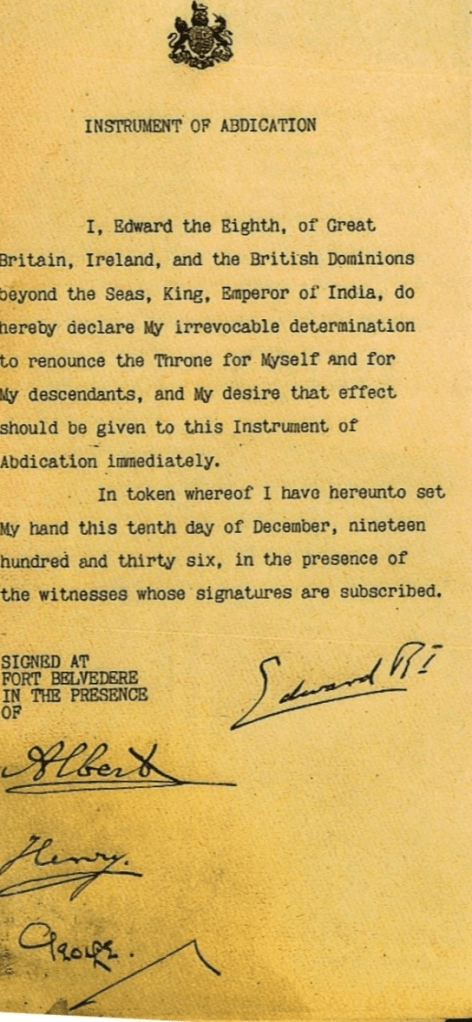

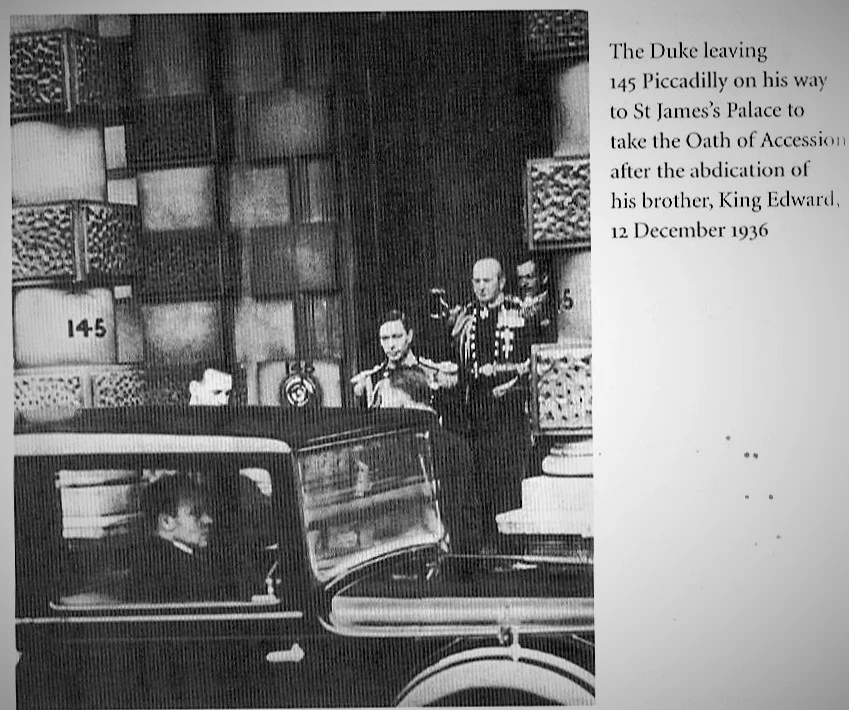

Ever since the abdication of Edward VIII in 1936, which suddenly propelled the ten-year-old Princess Elizabeth into the spotlight as the heir apparent, the membership of this institution was thought to require standards of personal behaviour well above the general norm of late twentieth-century expectations.

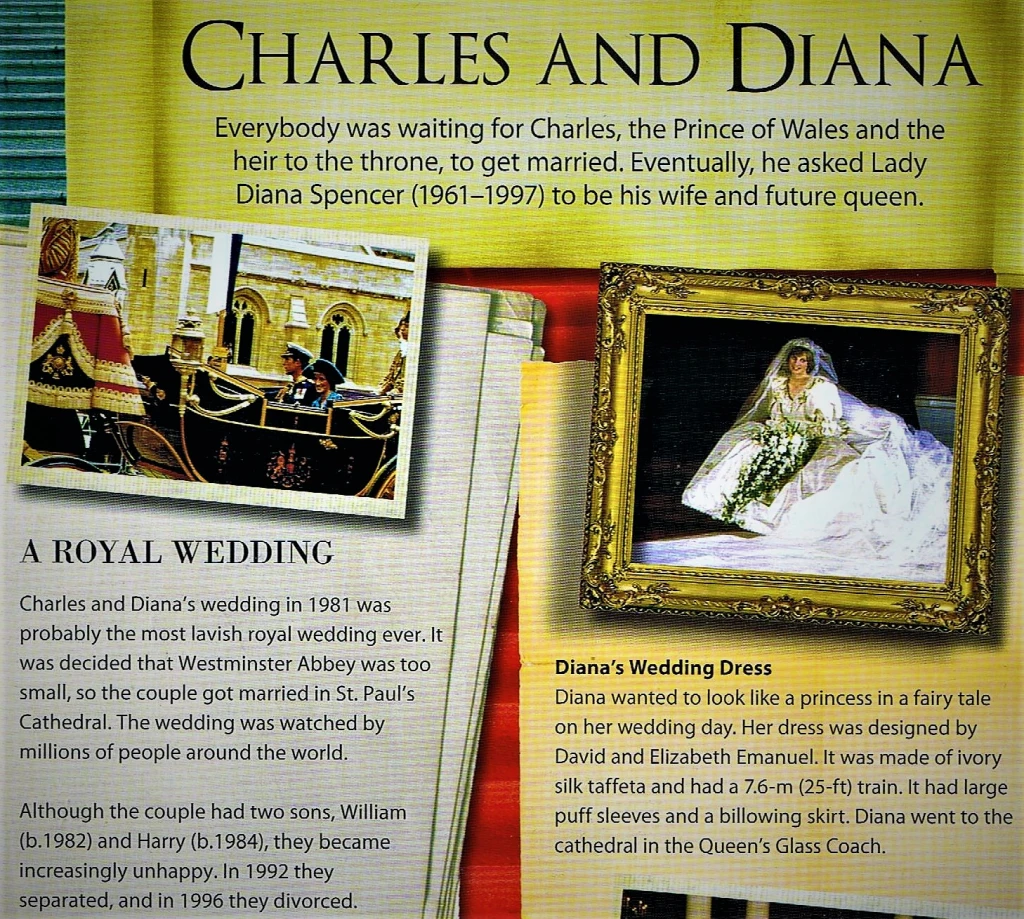

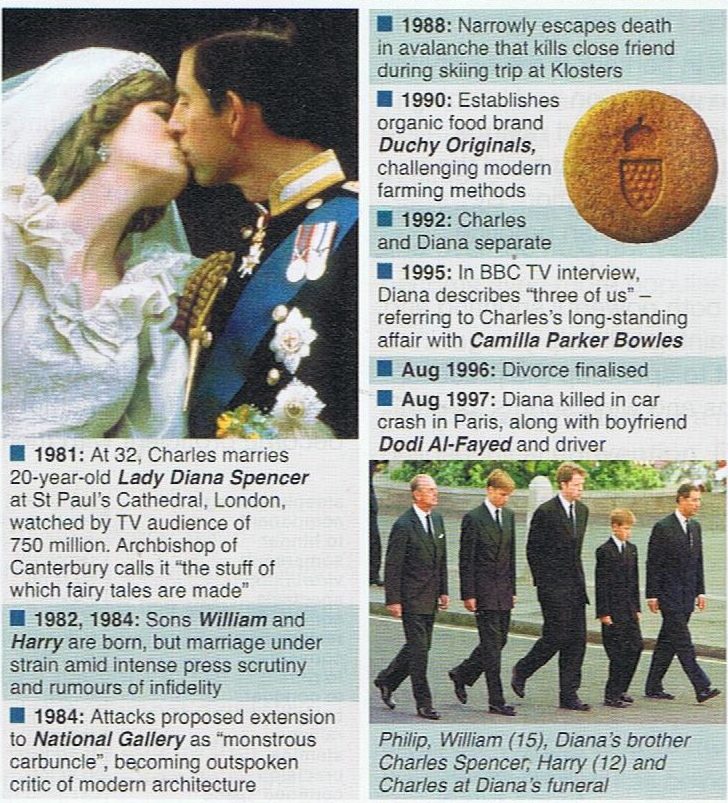

This celebrity fantasy world, which continued to open up in all directions throughout the nineties, served to re-emphasise to alert politicians, broadcasting executives and advertisers to the considerable power of optimism. The mainstream media in the nineties was giving the British an unending stream of bleakness and disaster, so millions tuned in and turned over to celebrities. That they did so in huge numbers did not mean that they thought that celebrities had universally happy lives. And in the eighties and nineties, no star gleamed more brightly in the firmament than the beautiful yet troubled Princess Diana. The fairy-tale wedding of the Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer at St Paul’s in 1981, which had a worldwide audience of at least eight hundred million viewers, meant that for fifteen years she was an ever-present in the media. Yet, as an aristocratic girl whose childhood had been blighted by the divorce of her parents, she found herself pledging her life to a much older man who shared few of her interests and did not even seem to be truly in love with her.

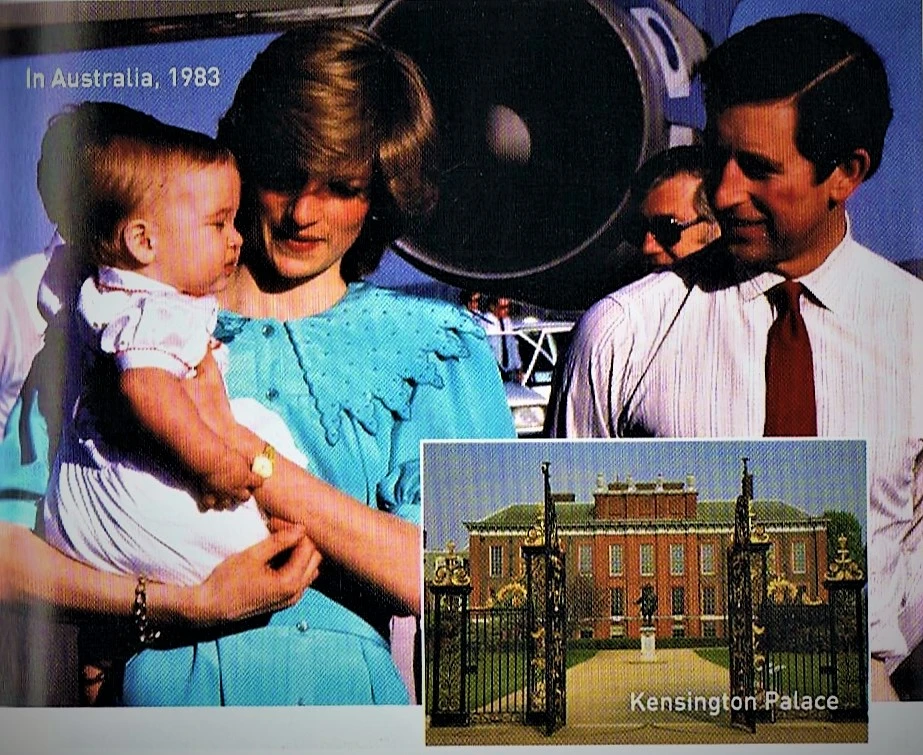

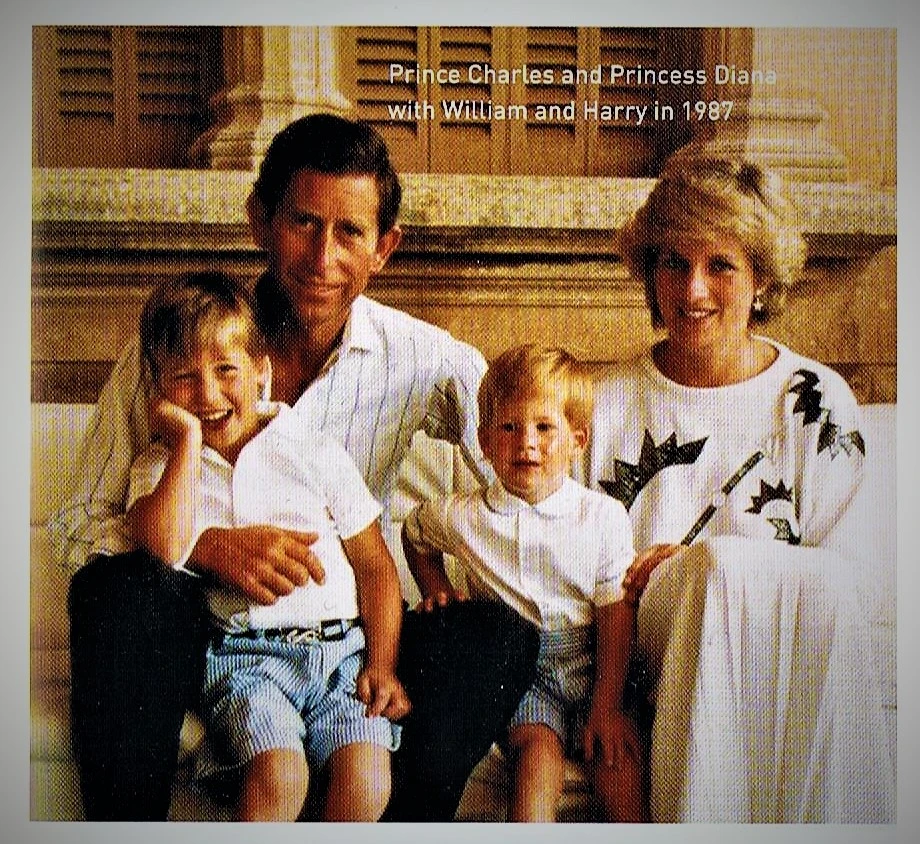

At first, Princess Diana seemed shy, naive and slightly awkward in front of the cameras. She suffered from an eating disorder, Bulimia, and lost weight. But as she became more confident she began to enjoy the attention she was attracting. In 1982, a little over a year after her fairy-tale wedding, Diana had her first son, William Arthur Philip Louis, who was born in London on the 21st of June. He lived at Kensington Palace with Prince Charles and Princess Diana. When he was only nine months old, his parents made an official visit to Australia and New Zealand. His mother did not want to be away from him for six weeks, so the little prince went with his parents.

Becoming ever more popular, she was soon dubbed The People’s Princess by the tabloid press. She also became the world’s most-photographed woman, and she was frequently seen on the covers of magazines and on television. She was even filmed dancing with the star of Saturday Night Fever and Grease, John Travolta.

In 1984, the royal couple had a second son, Prince Harry. William and Harry were always in the public eye as the new additions to the royal family. Photographers, newspaper reporters and TV cameras were part of their everyday life.

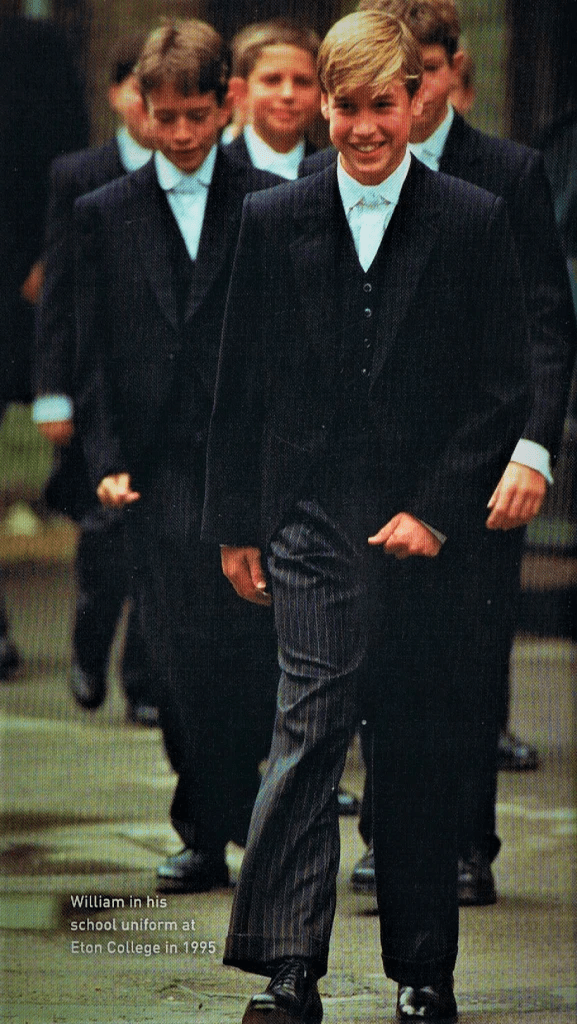

The two little boys enjoyed playing with each other at Kensington Palace. Young children in the royal family usually had nursery lessons at home, but Princess Diana, herself a nursery assistant, changed things. When William was three, he began to go to school in London with other young children. When he was eight, he went to Ludgrove School, about forty miles away from London, so he lived at the school and only went home once a month. At first, he was unhappy, but he soon began to enjoy football and other sports. Two years later, his brother Harry joined him at the school.

Above: The State Opening of Parliament in November 1991, for the last session before the 1992 General Election.

As ever, the opening ceremony, shown above, was a mixture of pageantry and serious political business. Once the Queen took her seat on the throne in the House of Lords, she sent ‘Black Rod’ to the Commons chamber to summon the MPs to join her and the Lords for her reading the speech outlining the new laws the Government was planning to make in the forthcoming parliamentary year. The Speaker of the Commons, Betty Boothroyd, was then followed by the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition into the House of Lords, followed by the rest of the MPs. Of course, it was not really the Queen’s Speech at all, but the Government’s, written by the Prime Minister at the time, in this case, John Major, and his colleagues to be read out by the Queen. In 1991, the Speech contained fewer proposals, or bills, than in previous years because the Government wanted to cut short the parliamentary year and call a General Election in the Spring (as it turned out, for 9th April). The main bills referred to in the Speech were on criminal justice and the environment, a ‘green’ bill. Other anticipated measures to bring in privately financed toll roads and new rules to ease traffic congestion in London.

Just as the monarchy had gained from its ceremonies, especially its royal weddings, so it lost commensurately from the failure of those unions. As a young man, Charles had dated Camilla Shand. But when he was sent abroad with the Royal Navy, Camilla married Andrew Parker-Bowles. Even though he eventually married Diana, it became obvious that Charles was still in love with Camilla. When rumours spread of Diana’s affairs, they no longer had the moral impact that they might have had in previous decades. By the nineties, Britain was now a divorce-prone country, in which what’s best for the kids and I deserve to be happy were phrases which were regularly heard in suburban kitchen diners. Diana was not simply a pretty woman married to a king-in-waiting but someone people felt, largely erroneously, would understand them. There was an obsessive aspect to the admiration of her, something that the Royal Family had not seen before, and its leading members found it very uncomfortable and even, at times, alarming. They were being weighed in the balance as living symbols of Britain’s ‘family values’ and found wanting.

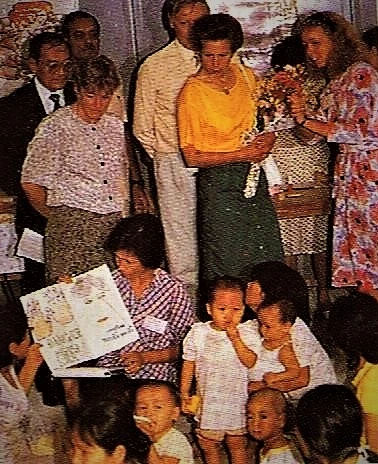

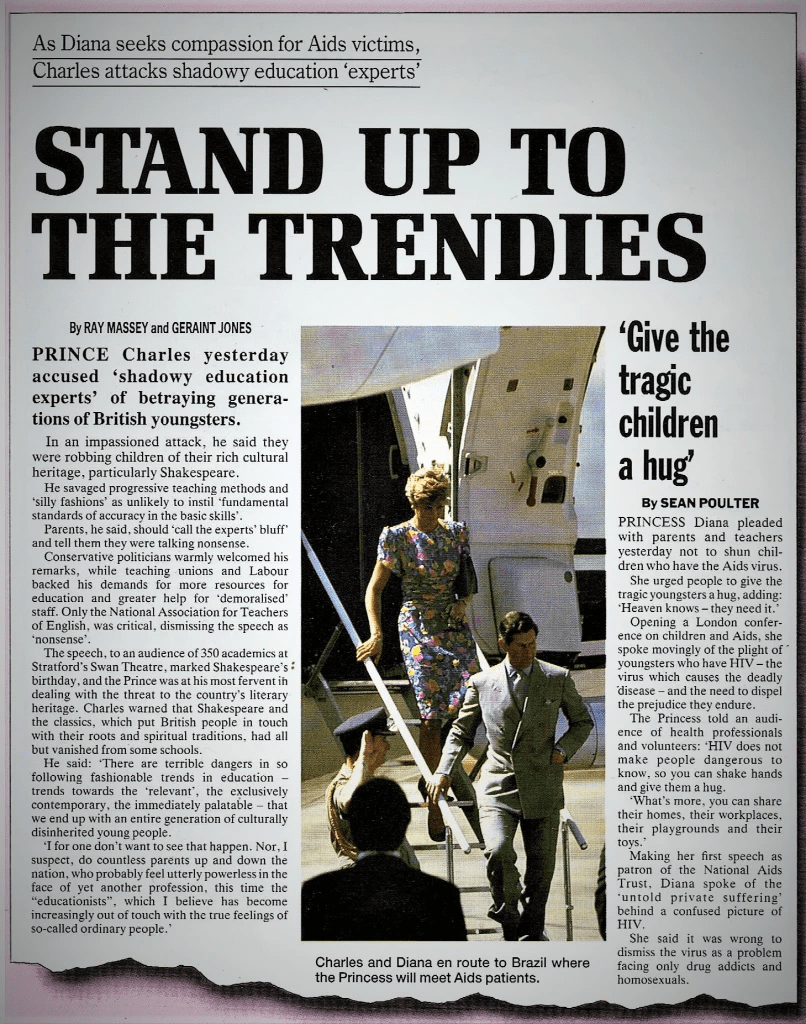

Yet as the two contemporary stories from The Daily Mail (below) show, even as they became increasingly estranged, the couple were able to support each others’ concerns, passions and charitable work. In the article on the left, Prince Charles pointed to the danger of teachers using teaching methods recommended by educational ‘experts’ leading to teaching only fashionable topics, neglecting students’ cultural heritage. Though controversial with some in the profession, his call for more resources for schools was well-received by most. Opening a London conference on children with AIDS, Princess Diana spoke about the confused understanding of HIV that existed and encouraged people through her own actions as well as words, to overcome their fear of touching people, especially children, with the virus. She also outlined the tragic situation of children with HIV and the prejudice they felt.

Nevertheless, by the mid-1990s, the monarchy was looking shaky, perhaps even mortal. The year 1992, referred to by the Queen, in her Christmas Speech, as her annus horriblis, had seen not just the separations of Charles and Diana (of Wales) as well as Andrew and Sarah (the Yorks), but also a major fire at Windsor Castle in November. When it was announced that the Crown would only pay for the replacement and repair of items in the royal private collection and that repairs to the fabric would therefore come from the tax-paying public, a serious debate began about the state of the monarchy’s finances and its tax status. In a poll, eight out of ten people asked thought the Queen should pay taxes on her private income, hitherto exempt. A year later, Buckingham Palace was opened to public tours for the first time and the Crown did agree to pay taxes.

In December 1992, Diana went to see William and Harry at school. She told them that Charles and she were not a couple anymore. Naturally, William and Harry were very upset about this. Later the same month, John Major announced the separation of Charles and Diana to the House of Commons. After their separation, Diana continued her charity work, especially with AIDS victims and in the campaign against the use of land mines in wars, all of which kept her in the public eye and maintained her popularity in Britain and worldwide.

The journalist Andrew Morton claimed to tell Diana’s True Story in a book which described suicide attempts, blazing rows, her bulimia and her growing certainty that Prince Charles had resumed an affair with his old love Camilla Parker-Bowles, something he later confirmed in a television interview with Jonathan Dimbleby. There was a further blow to the Royal Family’s prestige in 1994 when the royal yacht Britannia, the floating emblem of the monarch’s global presence, was decommissioned. Mr and Mrs Parker-Bowles, Andrew and Camilla, divorced in 1995 and then came the revelatory 1995 (now discredited) interview on BBC TV’s Panorama programme between Diana and Martin Bashir. Breaking every taboo left in Royal circles, she freely discussed the breakup of her marriage, claiming that there were three of us in it, attacked the Windsors for their cruelty and promised to be ‘queen of people’s hearts.’ When Charles and Diana finally divorced in 1996, she began a relationship with Dodi al-Fayed, the son of the owner of Harrods, Mohammed al-Fayed.

Meanwhile, William continued his education at Eton College, near Windsor Castle, so that he could go there to visit his grandmother when she was at home. William worked hard at Eton and was also successful at sports. Then, on 31st August 1997, William and Harry were on holiday with his father and grandparents at Balmoral when the terrible news of their mother’s death in a car accident in Paris. On 6th September, the boys walked behind his mother’s coffin through the streets of London to Westminster Abbey for her funeral. Prince Harry, Prince Charles, Prince Philip and Diana’s brother, Earl Spencer, walked alongside them. Everyone felt heartbroken for the two young princes on what was a terrible day for the British royal family. William left Eton three years later, in 2000, and then went on a gap year, including a stint in Chile, where he worked as a resident teaching assistant.

To many in the establishment, Diana was a selfish, unhinged woman who was endangering the monarchy. To many millions more, however, she was more valuable than the formal monarchy, her readiness to share her pain in public making her even more fashionable. She was followed all around the world, her face and name selling many papers and magazines. By the late summer of 1997, Britain had two super-celebrities, Tony Blair and Princess Diana. It was therefore grimly fitting that Tony Blair’s most resonant words as Prime Minister which brought him to the height of his popularity came on the morning, in August 1997, when Princess Diana was killed in a car accident in Paris with Dodi Fayed. Their car was speeding away from paparazzi photographers when it crashed into the pillars of an underpass. Tony Blair was woken at his Sedgefield constituency home, first to be told about the accident, and then to be told that Diana had died. Deeply shocked and worried about what his proper role should be, Blair spoke first to Alistair Campbell and then to the Queen, who told him that neither she nor any other senior member of the Royal Family would be making a statement. He decided, therefore, that he had to say something. Later that Sunday morning, standing in front of his local parish church in Trimdon, he spoke words which were transmitted live around the world:

“I feel, like everyone else in this country today, utterly devastated. Our thoughts and prayers are with Princess Diana’s family, in particular her two sons, her two boys – our hearts go out to them. We are today a nation in a state of shock…

“Her own life was often sadly touched the lives of so many others in Britain and throughout the world with joy and with comfort. How many times shall we remember her in how many different ways, with the sick, the dying, with children, with the needy? With just a look or a gesture that spoke so much more than words, she would reveal to all of us the depth of her compassion and her humanity.

“People everywhere, not just here in Britain, kept faith with Princess Diana. They liked her, they loved her, they regarded her as one of the people. She was – the People’s Princess and that is how she will stay, how she will remain in our hearts and our memories for ever.”

Although these words seem, more than twenty-five years on, to be reminiscent of past tributes paid to religious leaders, at the time they were much welcomed and assented to. They were the sentiments of one natural charismatic public figure for another. Compared with other politicians, Tony Blair seemed very young and in tune with youth culture. Blair regarded himself as the People’s Prime Minister, leading the people’s party, beyond left and right, beyond faction or ideology, with a direct line to the people’s instincts. After his impromptu eulogy, his approval rating rose to over ninety per cent, a figure not normally witnessed in democracies.

Blair and Campbell then paid their greatest service to the ancient institution of the monarchy itself. The Queen, still angry and upset about Diana’s conduct and concerned for the welfare of her grandchildren, wanted a quiet funeral and to remain at Balmoral, away from the scenes of spontaneous public mourning in London. However, this was potentially disastrous for her public image. There was a strange mood in the country deriving from Diana’s charisma, which Blair had referenced in his words at Trimdon. If those words had seemed to suggest that Diana was a saint, a sub-religious hysteria responded to the thought. People queued to sign a book of condolence at St James’ Palace, rather than signing it online on the website of the Prince of Wales. Those queuing even reported supernatural appearances of the dead Princess’ image. By contrast, the lack of any act of public mourning by the Windsors and the suggestion of a quiet funeral seemed to confirm Diana’s television criticisms of the Royal Family as being cold if not cruel towards her.

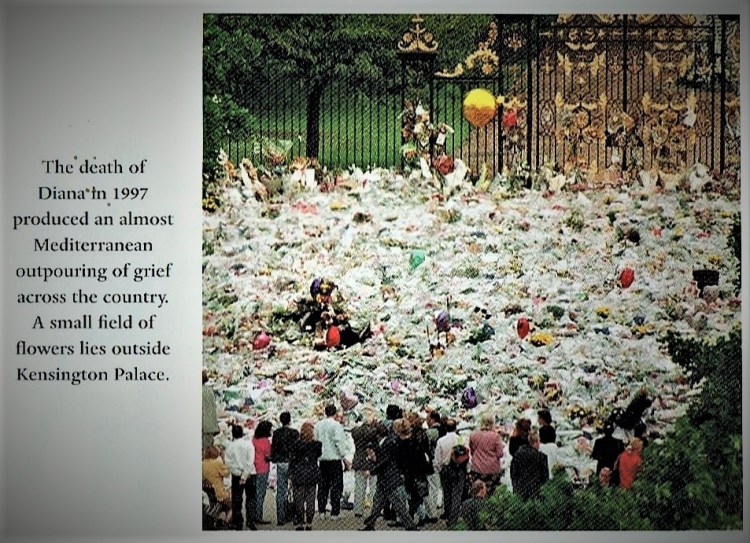

Also, with Prince Charles’ full agreement, Blair and his aides put pressure on the Palace first into accepting that there would have to be a huge public funeral so that the public could express their grief, and second into accepting that the Queen should return to London. She did, just in time to quieten the genuine and growing anger about her perceived attitude towards Diana. This was a generational problem as well as a class one. The Queen had been brought up in a land of buttoned lips, stoicism and private grieving. She now reigned over a country which expected and almost required exhibitionism. For some years, the deaths of children, or the scenes of fatal accidents had been marked by little shrines of cellophane-wrapped flowers, soft toys and cards. In the run-up to Diana’s funeral parts of central London seemed almost Mediterranean in their public grieving. There were vast mounds of flowers, people sleeping out, holding up placards and weeping in the streets, and strangers hugging each other.

The funeral itself was like no other before, bringing the capital to a standstill. In Westminster Abbey, campaigners stood alongside aristocrats, entertainers with politicians and rock musicians with charity workers. Elton John performed a hastily rewritten version of ‘Candle in the Wind’, originally his lament for Marilyn Monroe, now dedicated to ‘England’s Rose’, and Princess Diana’s brother Earl Spencer made a half-coded attack from the pulpit on the Windsors’ treatment of his sister. This was applauded when it was relayed outside and clapping was heard in the Abbey itself. Diana’s body was driven to her last resting place at the Spencers’ ancestral home of Althorp in Northamptonshire. Nearly a decade later, and following many wild theories circulated through cyberspace which reappeared regularly in the press, an inquiry headed by a former Metropolitan Police commissioner concluded that she had died because the driver of her car was drunk and was speeding in order to throw off pursuing ‘paparazzi’ photographers. The immense outpouring of public emotion in the weeks that followed seemed both to overwhelm and distinguish itself from the more traditional devotion to the Queen herself and to her immediate family. As Simon Schama has put it,

The tidal wave of feeling that swept over the country testified to the sustained need of the public to come together in a recognizable community of sentiment, and to do so as the people of a democratic monarchy.

Diana’s funeral was probably watched by as many people as had watched her wedding. For a short time, the Queen became very unpopular, as she did not immediately return from Balmoral to Buckingham Palace when Diana died, or even fly a flag at half-mast. But those who complained about this in the popular media did not seem to understand that Royal protocol dictates that the Royal Standard should only be flown above Buckingham Palace when the Monarch is in residence. Added to this, the Union Flag is only flown above the royal palaces and other government and public buildings on certain special days, such as the Princess Royal’s birthday, 15 August. Since it was holiday time for the Royal family, and they were away from London, there were no flags flying. Nor would the general public have known that flags are only flown at half-mast on the announcement of the death of a monarch until after the funeral, and on the day of the funeral only for the deaths of other members of the royal family.

The Queen, as the only person who could authorise an exception to these age-old customs, received criticism for not flying the union flag at half-mast in order to fulfil the deep need of her grief-stricken subjects. Although Her Majesty meant no disrespect to her estranged and now deceased daughter-in-law, the Crown lives and dies in such symbolic moments, and she duly relented. The crisis was rescued by a live, televised speech she made from the Palace which was striking in its informality and obviously sincere expression of personal sorrow. Her people now understood that their way of grieving was very different from the more conventional but no less heartfelt mourning of the Queen and her immediate family. Her Majesty quickly rose again in public esteem and came to be seen to be one of the most successful monarchs for centuries and the longest-serving ever. A popular film about her, including a sympathetic portrayal of these events, sealed this verdict.

and celebrated her Diamond Jubilee in 2012 and her Platinum (70th) Jubilee in 2022.

Tony Blair never again quite captured the mood of the country as he did in those sad late summer days. It may be that his advice and assistance to the Queen in 1997, vital to her as they were, in the view of Palace officials, were also thoroughly impertinent. His instinct for popular culture when he arrived in power was certainly uncanny. The New Age spiritualism which came out into the open when Diana died was echoed among Blair’s Downing Street circle. What other politicians failed to grasp and what he did grasp, was the power of optimism expressed in the glossy world of celebrity, and the willingness of people to forgive their favourites not just once, but again and again. One of the negative longer-term consequences of all this was that charismatic celebrities discovered that, if they apologised and bared a little of their souls in public, they could get away with most things short of murder. For politicians, even charismatic ones like Tony Blair, life would prove a little tougher, and the electorate would be less forgiving of oft-repeated mistakes. Nevertheless, like Magaret Thatcher, he won three elections and was in office for more than ten years.

The monarchy was fully restored to popularity by the Millennium festivities, at which the Queen watched dancers from the Notting Hill Carnival under the famous Dome, and especially by the Golden Jubilee celebrations of 2002, which continued the newly struck royal mood of greater informality.

One of the highlights of the ‘Party in the Mall’ came when Brian May, the lead guitarist of the rock band Queen began the pop concert at Buckingham Palace by playing his instrumental version of God Save the Queen from the Palace rooftop. Modern Britannia seemed, at last, to be at ease with its identity within a multi-national, multi-ethnic, United Kingdom, in all its mongrel glory.

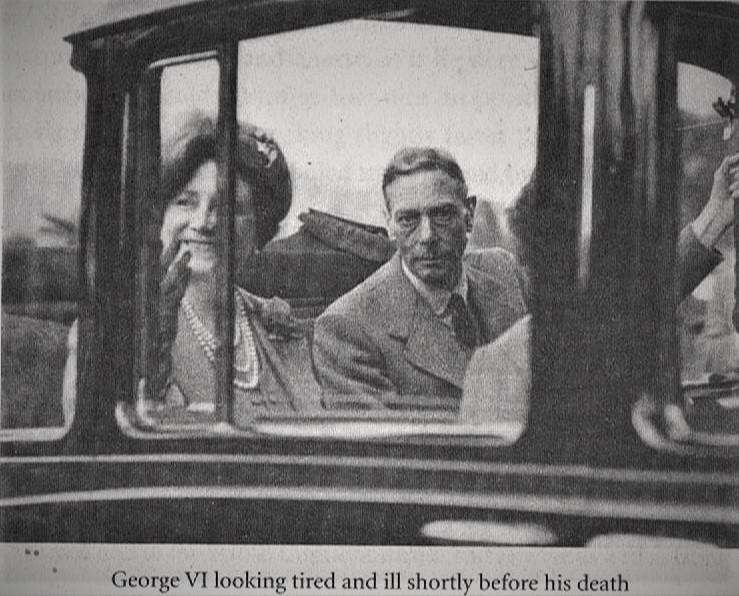

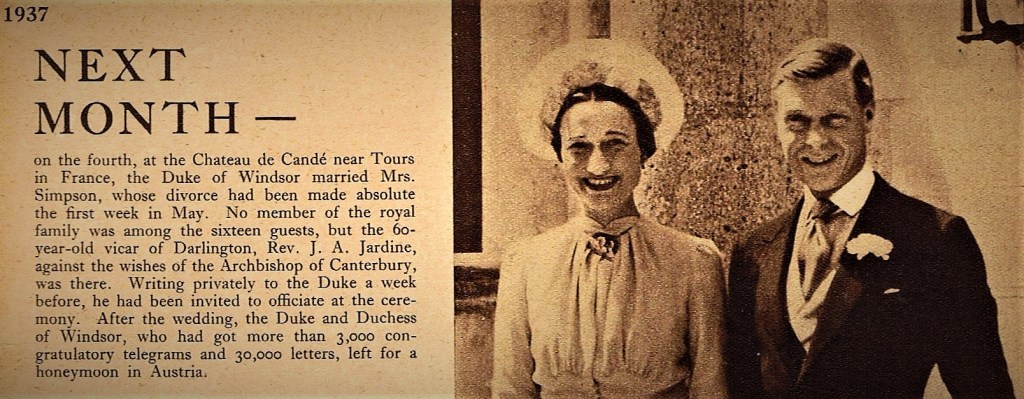

Also in 2002, George VI’s widow, Queen Elizabeth, known as the Queen Mother after her husband’s death and her daughter’s accession in 1952, died at the age of 102. After George VI’s death, she continued to carry out many public duties at home and abroad. Many thought that Charles would not marry the divorced Camilla while his grandmother was still alive. She had become Queen Consort in 1937 because her brother-in-law, Edward VIII had not been allowed to marry a divorcée as king, choosing to abdicate the throne instead.

Charles and Camilla were able to marry in 2005, in a civil wedding at Windsor, but it was decided that Camilla should be known as Duchess of Cornwall, out of respect for Diana, Princess of Wales.

Sources:

Simon Schama (2002), A History of Britain; The Fate of Empire, 1776-2000. London: BBC Worldwide.

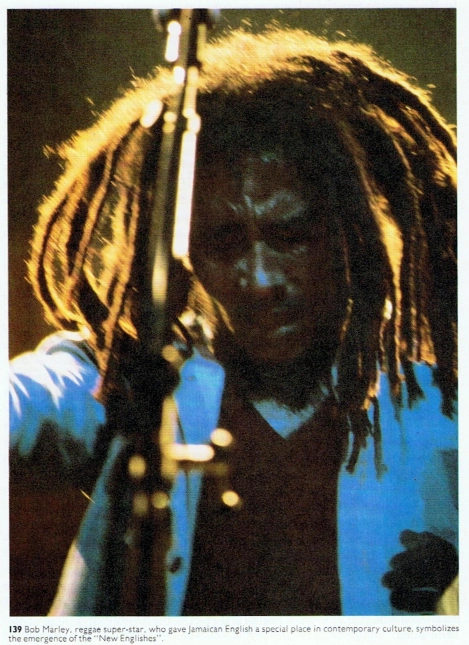

Robert McCrum, William Cran & Robert MacNeil (1987), The Story of English. London: Penguin Books.

John Haywood & Simon Hall, et.al. (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British and Irish History. London: Penguin Books.

Gwyn A. Williams (1985), When Was Wales? Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Bill Lancaster & Tony Mason (eds.)(n.d.), Life and Labour in a Twentieth Century City: The Experience of Coventry. Coventry: University of Warwick Cryfield Press.

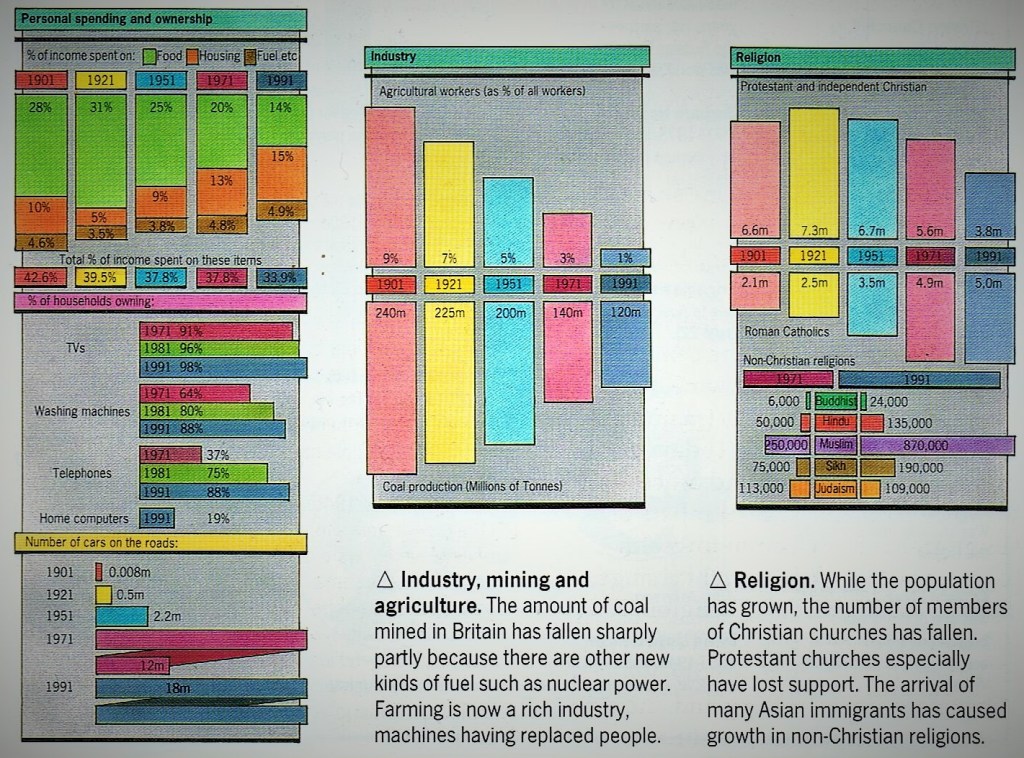

Appendix: A Breakdown of Census Statistics, 1901-1991, in Graphs:

Right:

Population: By the end of the twentieth century, there were twenty million more Britons than there were at its beginning, In the first part of the century, the population grew fast due to high birth rates. Since the 1970s, this growth slowed down. Fewer babies were being born. But people born since 1991 can expect to live much longer than those born in 1901. Women, as always, can expect to live longer than men. At the beginning of the century, only about four per cent of the population was over sixty-five: By its end, this had risen to thirteen per cent. At the same time, fewer babies were being born, so whereas in 1901 the average household included 4.6 people, in 1991, it was only 2.5. It was not just that there were fewer children, but also because there were many more single-parent families.

There was also a dramatic fall in the number of servants. Over the first half of the century, the number of households with live-in servants fell from over ten per cent to only about one per cent.

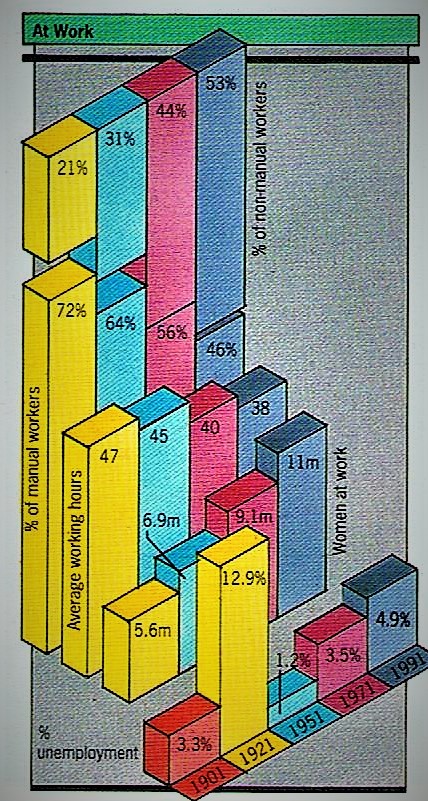

Work: The number of working women doubled over the course of the century. The number of unemployed people rose even faster, especially in the period between the two world wars, and again in the 1970s and ’80s. Those employed in manual labour or ‘manufacturing’ decreased significantly, by more than a quarter, from three-quarters of the workforce to less than half, so that in 1991 most people in work were in non-manual occupations based in shops and offices. On average, working hours were reduced by nine hours per week, more than one whole working day on average, leaving more family and leisure time.

Spending (left, below): Over the twentieth century, people were gradually able to spend an increasing proportion of their income on ‘consumer goods’ and a smaller proportion on food.