Lanes to Langport:

While the King camped out at Raglan Castle at the beginning of July, to the north of the main ongoing conflict, Royalist troops under Lord Byron were attempting to hold their own at Chester, and in the south-west Lord Goring, continuing to command the King’s army there, was attempting to fight his way into Taunton. Fairfax lost no time in ensuring that royalist hopes of a military recovery were dashed. His first priorities were to relieve Taunton and defeat Goring. If, however, Charles could combine with Goring he would have an army of a superior size, though not of the same quality, as the army he had lost in the field at Naseby on 14th June. Taunton was held for Parliament by Colonel Robert Blake and Fairfax was ordered to march to his relief. But as Royalist garrisons at Bristol, Bath and Devizes blocked Fairfax’s most direct route from the Midlands, he advanced southwards using the south coast ports for re-provisioning. He drove his men hard; between Marlborough and Dorchester, they marched an average of seventeen miles per day over five consecutive days. By 3 July, the New Model was quartered at Dorchester, where it was met by leaders of the Clubmen of Dorset and Wiltshire, local people who had taken to arms to protect their homes. They asked for passes to carry petitions to both King and Parliament, calling for a cessation of hostilities and the handing over all the places in Dorset that were garrisoned by either side to the Clubmen themselves. Fairfax naturally refused their request, though with courtesy and reasoned argument. Their numbers made them formidable as a third force, but their attitude softened as they came to appreciate his genuine consideration for local interests and the growing contrast between his army’s respect for law and property and the habitual marauding of the western royalists.

By 4 July the New Model were nearing Crewkerne, prompting Goring to raise his siege of Taunton, falling back to the River Yeo between Yeovil and Langport. He then took up a forward position to the east of Bridgwater at Langport to await the advancing parliamentarian army. Goring garrisoned his position there, giving it a strategic position, controlling a bridge across the River Parrett. The royalist garrison at Langport was in an important strategic position, controlling the bridge across the River Parrett. On 6 July, Fairfax sent Colonel Montague, with two thousand musketeers to the aid of Major General Massey at Ilchester. Massey was in command of several regiments of horse and dragoons with which he followed a large part of Goring’s army, marching on Taunton once more. However, before Montague could reach them, Massey’s forces had already engaged and damaged Goring’s army. Fairfax then turned Goring’s line by capturing Yeovil. After that, Fairfax had no difficulty in making Goring give up the siege of Taunton, but experienced rather more in bringing him to battle on advantageous terms. The ranks of the of the New Model were thinned after Naseby, where many more had been wounded than killed, by the escort that he had had to provide that for the 4,500 royalist prisoners, and by the chronic drain of desertions. Massey and his Western Association forces, garrisoned in Gloucester, had brought his strength up to fourteen thousand.

Goring with about half that number was also expecting reinforcements, in his case from south Wales, and was avoiding battle until they arrived. On 10 July, The Royalists regrouped at Langport and Goring dispatched three brigades of cavalry south-westwards in the hope of convincing Fairfax that Taunton was under threat again so that he would split his forces, thereby reducing the numerical disparity between the armies. Fairfax dispatched 5,500 Horse in pursuit of George Porter, who was intercepted and defeated near Ilminster. Goring then began to withdraw in the direction of Bridgwater. To allow his baggage and artillery trains to cover the twelve miles to Bridgwater, he then prepared to fight a delaying action from high ground to the east of Langport. He had been able to select a strong defensive position there, and was much less heavily outnumbered than he had been a few days earlier. That morning the troops sent to assist Massey at Ilchester were recalled by Fairfax, but they didn’t join the main part of the New Model until the battle was over. Goring could only oppose roughly seven thousand men to Fairfax’s ten thousand. However, because it was a landscape of hedged and ditched fields, this was primarily a battle for musketeers and cavalry, with the New Model’s pikemen unable to play a significant role in the action.

Goring’s position was fronted by a brook known as the Wagg Rhyne and by a good deal of marshy ground. The Langport-Somerton road crossed the brook at a ford before ascending the hill in the centre of the Royalist line. The road and the surrounding fields were bordered by hedges which Goring lined with musketeers, and sited two guns to cover the ford, with cavalry in support. It was a seemingly strong position and the nature of the ground offered Fairfax little alternative but to make a frontal attack along the road. But Fairfax attacked with boldness and skill, making good use of his artillery and co-ordinating the deployment of his cavalry and infantry with precision. After a Parliamentarian battery had silenced the Royalist guns, fifteen hundred musketeers were sent forward to clear the hedges surrounding the ford. Then, a detachment of parliamentarian cavalry advanced along the hedged lane on the Royalist position, defended by two cannon and by musketeers lining the hedgerows. As the Royalist infantry fell back, three troops of Cromwell’s Horse commanded by Major Bethell charged across the ford and up the slopes beyond. Success hung upon a cavalry charge which had to negotiate a line wide enough for only four troopers to ride abreast before they engaged the waiting royalist horse, and it was executed with proud courage by units which had ridden with Cromwell since before the New Model’s creation.

The first two ranks of Royalist horse broke before this charge but Goring’s remaining cavalry massed against Bethell and began to push him back. At this crucial moment three troops from Fairfax’s regiment struck Goring’s cavalry in its flank, supported by musketeers as the Parliamentarian foot began to arrive on the hill. By this time, Goring’s men could not match the spirit of Cromwell’s troopers. Goring’s cavalry broke and fled, pursued and attacked as they fled through the streets of Langport. His infantry regrouped for action but, without cavalry support, they had no option other than to surrender. Although only three hundred Royalists were killed, many more were captured or deserted. Cromwell reckoned that they lost two thousand killed or captured. Many others, scenting an unmitigated defeat, simply melted away. The New Model had destroyed the royalists’ last substantial field army. After garrisoning Bridgwater, Goring retreated into Devon with the remnants of the Western Army. The battlefield lies between Taunton and Somerton, approximately a thousand yards from the town of Langport on the road to Somerton.

Bridgwater to Sherborne:

By contrast with what had happened with the Earl of Manchester’s army following Marston Moor the previous year, Fairfax took every opportunity to capitalise upon his successes at Naseby and Langport. A pattern was established that was followed throughout the remainder of the year. Detachments of varying compositions were sent out to reduce lesser garrisons while the main body faced the major Royalist strongholds. The next target was the small but strongly fortified garrison at Bridgwater. The town was divided in two by the River Parrett, the lowest crossing of which gave it its strategic importance. The most heavily fortified part was on the west side of the river, which contained the Medieval castle with massive stone walls and a thirty-foot wide moat. The whole town was encompassed by a Medieval tidal ditch, which had been recut by the royalists. There were also stretches of surviving Medieval town wall, supplemented by new defences of earth and timber. There were said to have been forty guns mounted on these walls, but there are no traces of these defences remaining today. All that survives is a simple arch of the Water Gate to the castle in the West Quay.

Bridgwater was well-supplied and manned, with eighteen hundred troops under the command of Colonel Edmund Windham. The King had been led to believe that Bridgwater was “a place impregnable”. Twelve days after their victory at Langport, Fairfax decided that he had to storm the town in order to consolidate his victory since he did not have the time for a protracted siege. Part of the New Model was on the west side of the river, while on the eastern side were, as at Naseby, Fairfax’s, Skippon’s, Pickering’s, Montague’s, Hardress Waller’s, Pride’s, Rainsborough’s and Hammond’s regiments. The attackers described what happened on 21 July:

… About two of the clock in the morning, the storm began accordingly on this side of the town (the Forces on the other side only alarming the enemy…). Our Forlorn hope was manfully led on by Lt. Colonel Hewson: and as valiantly; and as valiantly seconded by the General’s Regiment … and the Major-General’s …

The ditch was crossed on portable bridges and the works scaled against strong resistance. Once inside, Pickering’s regiment opened the drawbridge for the other regiments to enter and soon that part of the town on the eastern side of the river was taken:

There was not one officer of note slain, though many in person led on their men, and did gallantly, as Lt. Col. Jackson, Lt. Colonel to the General, and Col. Hewson of Col. Pickering’s regiment.

Six hundred royalists still maintained the defences on the west side of the river. Having cut the bridge, the governor set fire to the eastern part of the town with a bomardment of red hot shot, leaving no more than three or four houses standing. This desperate defensive action was followed on the 22nd by the storming of the western part of the town, prepared by intensive cannon fire. In the face of this bomardment the governor soon surrendered, rather than allow the rest of the town to be devastated by fire as he himself had ordered the eastern half to be. The parliamentarian troops were promised five shillings per man as a reward for the storming of the town, to be taken out of the sale of goods captured. However, when the troops had still not heard anything by the middle of August, it was reported that, ‘for want of pay’, the men of various regiments took ‘free quarter’ and ‘plunder’ at will.

Meanwhile, Cromwell was dispatched to deal with the Clubmen, who were now supporting the royalists and causing the parliamentarian army considerable trouble. They were numerous enough to hamper Fairfax’s operations. There were two distinct associations of them in the region. One of them, based on the chalk downs of Dorset and neighbouring Wiltshire had a markedly royalist bias. At the same time other parliamentarian forces were sent to besiege Bath, while Colonel Pickering was given the task of besieging another key royalist garrison, at Sherborne. On 27 July, Fairfax …

… sent a Brigade of horse and foot unto Sherborn under the command of that pious and deserving Commander, Colonel Pickering, to face the garrison, and to view the same; and if there were hopes to reduce it, to sit down before it, in order to a seige.

The garrison at Sherborne, under the command of Sir Lewis Dyve, was in the Medieval Castle. It was proving particularly troublesome as it was encouraging the activities of the Clubmen against the parliamentarian forces. Colonel Pickering’s brigade consisted of two thousand foot, supported by Colonel Whalley’s Regiment of horse. On 1 August, Fairfax arrived outside Sherborne to view the siege works and the castle. On the 2nd, he ordered a “close siege”, believing that it might be possible to quickly reduce the garrison. Most of the army was brought up to Sherborne and they proceeded to construct siegeworks around the castle. Dyve refused a second summons to surrender on 6th August, and preparation was made for an assault. Mines were dug and gun batteries were constructed. The twelve foot thick castle walls were unaffected by the army’s artillery until demi-cannon arrived, by which time the siegeworks were within ten yards of the walls. On the 10th, the besiegers reported:

… our great Guns began to batter the strong wall of the castle, between the two lesser Towers thereof, and had soone beaten down one of them, and before six of the clock that night, had made a breach in the wall, so as twelve abreast might enter.

The castle, which the Enemy had vaunted would continue and hold out a half yeares seige at least, was most valiantly stormed. Ingoldsby’s men had gained the corner tower of castle. Dyve then refused quarter and so the final assault was prepared. Under continued musket fire the defenders had to withdraw from the Great Court. Their position was becoming increasingly difficult and they were now running short of ammunition. By the 15th Dyve had no alternative but to surrender. In total, two hundred of the besieging force had been lost over the sixteen days. The castle was plundered and later slighted, although large parts of it still stand today, and it is possible to pick out the traces of the triangular bastions and banks of the Civil War period, set immediately outside the Medieval ditch.

While Fairfax was besieging Sherborne, the ‘cavalier’ Clubmen had been in touch with its defenders and had agreed to try to help force Fairfax to raise the siege. He frustrated their plan by surprising a meeting of their leaders at Shaftesbury and sending them to London as prisoners, whereupon two thousand or more of their associates assembled in arms upon Hambledon Hill nearby, demanding their release. Three times Cromwell sent a party of horse to command them to disperse, and each time his men were fired upon; some were taken prisoner and according to Cromwell ‘used most barbarously’. Two of their most pugnacious leaders were Anglican clergymen. In the end it took a minor cavalry action to break them up, and though fewer than a dozen were killed, many more were wounded and about three hundred captured. Cromwell held them in a church overnight, took their names, warned them that they would be hanged if they were caught again opposing the Parliament’s forces, and then let them go.

Shaftesbury to Bristol:

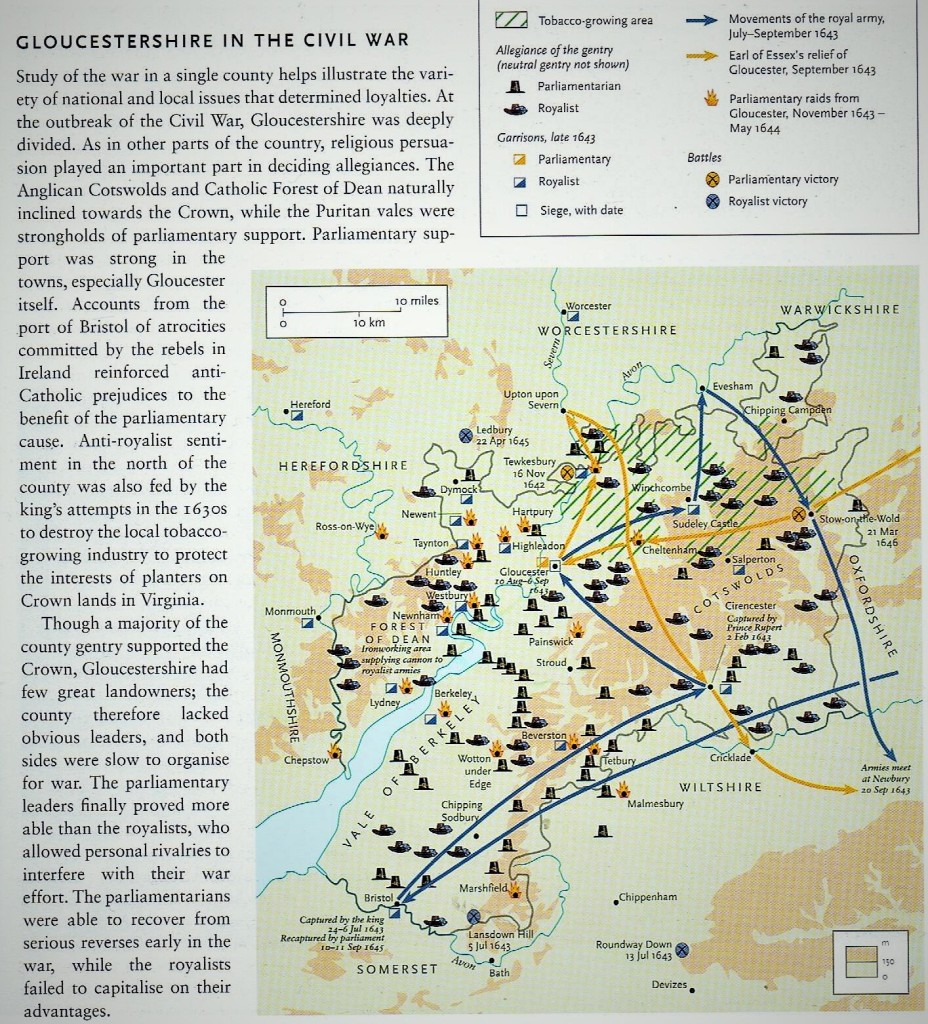

The other Clubmen association with which Fairfax dealt was drawn from the woodland and pastoral areas of Somerset and Gloucestershire. Research into the individual counties in the Civil War, especially by Underdown, has illustrated the importance of local issues in determining loyalties (see above). Gloucestershire was deeply divided during the Civil War, between royalists, parliamentarians and ‘clubmen’, local people who simply wanted nothing to do with the conflict and wanted to keep the fighting out of their towns and villages, if necessary by using a variety of ‘homemade’ arms themselves. Lacking great landed magnates to give leadership and with Gloucester firmly in parliamentary hands, the royalists proved ineffective. Gradually the better organised parliamentarians had been gaining control of the county, until in July 1643, when the King had seized Bristol and Gloucestershire had become the key theatre of the war.

Urged by his generals to exploit parliament’s disarray and advance on London, Charles instead turned aside to eliminate the last parliamentary garrison in the county, at Gloucester itself. Enthusiastically supported by the townsfolk, the garrison held out for six weeks until relieved by the Earl of Essex, possibly costing Charles the chance to end the war quickly. For the next two years, Gloucester remained a parliamentary enclave in royalist territory, a veritable ‘thorn in the side’ for Charles. The royalists failed to prevent the Gloucester garrison from raiding far and wide under its energetic commander Edward Massey; he slowly expanded the enclave until, after Naseby, royalist support in the county collapsed. In the clothing industries of the rural valleys of Gloucestershire and North Somerset, there was strong support for parliament and workers from these areas had quietly co-operated with Fairfax in the storming of Bridgwater.

Bath had been taken soon after Bridgwater. These defeats made Charles and Rupert abandon their tentative plans for a new campaign in the West Country, with Bristol as their base. Their position in south Wales was endangered by a combined operation by Vice-Admiral Batten and Major-General Laugharne, who routed the local royalist forces at Colby Moor near Haverfordwest on 1 August. By the time of the successful assault on Sherborne Castle on the 14th, Charles, who had been in Cardiff, was already heading north, feeling the trap closing upon him. Leaving Rupert with what he thought was a sufficient force to defend Bristol, he set off with the idea of making a junction with Montrose. After his triumph at Auldern, Montrose had won another brilliant and bloody victory over Baillie and the Covenanters at Alford on 2 July, and was advancing upon Glasgow. When the two faced each other again , eleven miles from Glasgow at Kilsyth on 15 August, the committee of estates overruled Baillie’s plan of battle, and his army of six thousand was utterly routed; only a few hundred escaped with their lives. Montrose, with his own forces now grown to at least 4,400 foot and five hundred horse, entered Glasgow soon afterwards, and for a brief while he was master of Scotland.

By then, Charles had got as far as Doncaster on his way to meet Montrose when he learnt that Leven and his army were on his tracks and only ten miles away. Leven had been besieging Hereford, but had broken off the operation to hunt larger prey. The Northern Association forces were also threatening Charles’ liitle army, so in search of safety he took it on a long and exhausting march by way of Newark and Huntingdon to Oxford and Worcester. By then his main concern, following the loss of the west country garrisons, was to save Bristol. Rupert had assured him that it could hold out for at least four months, which proved to be a serious error of judgement, one for which he was later made to pay dearly.

Although other minor garrisons in the West Country were being cleared, Fairfax’s main objective was now Bristol, which he had had in his sights ever since Naseby. He overruled the more cautious spirits in his council of war who advised him first to clear out the far south-west, where Grenville, Goring and Hopton among others were still under arms, but he did think it important to reduce the nearest royalist garrisons in Dorset and Somerset, as we have seen. One reason for this was the need to deal with the local Clubmen, both the ‘hostile’ ones from Dorset and Wiltshire and the more ‘sympathetic’ ones from Gloucestershire and Somerset. When operations began against Bristol the Somerset Clubmen allowed Fairfax to recruit two thousand auxiliaries from their ranks. Gloucestershire contributed a further fifteen hundred and both counties readily raised more volunteers as the the siege progressed.

The vanguard of the Parliamentary Army assembled around Bristol on the 22nd and 23rd August, when Fairax completed his investment of the City. Despite its formidable fortifications Fairfax did not intend to conduct a long siege. Yet the alternative of storming the city was a daunting one, and Rupert’s assurance to the king that he could hold out for four months shows that he expected no such exploit. Success depended on the newly developed courage of the infantry, having taken the outlying royalist garrison towns. Until a breach was made or a gate forced open, cavalry would be of little help. Sallies were made by the garrison over the following days against various regiments around the city. For foot soldiers, a pitched battle at push of pike was a severe enough test of morale, but to scale high walls under fire from cannon and muskets, and with defenders waiting to club or run through the assailants as they came over the top, must have been quite terrifying.

On the 29th the defenders attacked the parliamentarian quarters near Lawford’s Gate. It was then decided that the city should be stormed, because Fairfax was not confident that his army could maintain a long siege. By the time of the assault on Bristol the command of the General’s Brigade, comprising Fairfax’s, Montague’s, Pickering’s and Sir Hardress Waller’s regiments, had fallen to Colonel Montague. They were to attack on both sides of Lawford’s Gate, while other brigades attacked on the north and the west sides of the city. Montague’s and Rainsborough’s Brigades crossed the Avon at Keynsham to Stapleton where they quartered that night. Montague’s Brigade then secured the area between the rivers Frome and Avon, coming up to within musket-shot of Lawford’s Gate.

On the morning of the 10th, a concerted attack was mounted. A new earthwork defence, with forts set along it, had been constructed outside the Medieval town walls. Fairfax sent his men in across these fortifications, even though the previous six days of bombardment had failed to make a breach in the walls. The soldiers carried faggots to fill in the ditch while some brought up ladders to scale the ramparts. The New Model foot that had fallen back before inferior numbers at Naseby fought heroically. Their task was made harder because at most points of attack their scaling ladders were too short to reach the tops of the walls. Priors’ Hill Fort, on the north side of the Frome, was captured but to the south of the Avon the attack faltered against much more substatial defences.

The decisive assault took place on the eastern side of the city. It was here that Montague’s Brigade stormed the defences on both sides of Lawford’s Gate, bothe to the river Avon, and the lesser river Froome. They forced their way in , and their numbers told in the end. Pickering himself entered gallantly, and with others gave the royal party that wound, which will hardly ever be healed. Fairfax had not far short of ten thousand men, including cavalry, backed by nearly five thousand Clubman auxiliaries. There was plague in the city, and sickness and desertion had left Rupert with at most two thousand regular troops and a thousand trained bands an auxiliaries to man a perimeter three to four miles long (although the Mayor of Bristol told Cromwell that Rupert had about a thousand horse and 2,500 foot, besides 1,200 or more trained bands and auxiliaries, but Rupert’s own narrative states that though his garrison was nominally 2,300 strong, he could never man the line with more than 1,500 regular soldiers, and that the trained band and auxiliaries were down to eight hundred).

In his dispatch to the Speaker, Cromwell paid generous tribute to the gallantry of the soldiers which had secured this great victory. He described how:

Col. Montague and Col. Pickering, who stormed at Lawford’s Gate, where was a double work, well filled with men and cannons, presently entered; and with great resolution beat the Enemy from their works, and possessed their cannon. Their expedition was such that they forced the Enemy from their advantages, without any considerable loss to themselves. They laid down the bridges for the horse to enter; … Then our foot advanced to the Castle Street: whereunto were put a Hundred men; who made it good.

He also testified that men of different religious professions had fought together as comrades, fired by the same spirit of faith and prayer, and he ended with an eloquent plea for that they and ‘the people of God all England over’ should enjoy liberty of conscience. With obvious reference to the sterile pursuit of religious uniformity thenin progress, he urged that the real unity was inward and spiritual, and from brethren, in things of the mind, we look for no compulsion but that of light and reason.

The Commons deleted the whole paragraph when they published his letter, as they had done with a similar plea in his Naseby dispatch, but his independent supporters had it printed separately and scattered in the streets. It probably received more public attention in the end because of the shabby attempt to suppress it.

Prince Rupert now requested a parley and Col. Pickering, with Montague and Rainsborough, was responsible for the negotiations with the royalists. The garrison surrendered on the following day. In all during the action Pickering’s and Montague’s captured twenty-two great guns and took many prisoners. For such a hazardous assault on one of the the major towns in the kingdom the losses were remarkably light. It was reported that in Col. Rainsborough’s and Col. Montague’s Brigade, not fortie men are lost, while in total the parliamentarian army suffered no more than two hundred killed. Apart from the earthwork remains on the fort on Brandon Hill, which now lie within a public park, nothing survives of the defences of Bristol. Of Lawford’s Gate, only the street name remains to show where the decisive breach was made.

No previous defeat so shocked and grieved the king as the surrender of Bristol. He saw it as a betrayal and immediately dismissed his nephew from the command of his army, rebuking him in a letter for ‘so mean an action’ and directing him to seek his subsistence overseas. This appears grossly unjust, even by contemporary absolutist standards. Rupert could fairly be faulted for misleading Charles about his power to hold on to Bristol for four months, but not for seeking terms when an immensely superior enemy had forced its way into a city beset with plague and had its defenders and citizens at its mercy. If he had cared nothing for civilian casualties or for the lives of his own men he might conceivably have withdrawn into the fort for a do-or-die stand, but his own officers judged this untenable in any case, and the only possible justification would have been that the King or Goring or both could have brought him swift and powerful relief. Bur Charles himself was in Raglan and in no position to assist him, and Goring was still in Exeter; Fairfax had intercepted from him saying that it would take him three weeks to get to Bristol.

Devizes to Winchester:

Montague was called to London and command of the brigade, which had fought together since Naseby, changed once more, passing to Col. John Pickering. Following the fall of Bristol the army was again divided and the clearance of the lesser royalist garrisons continued. Rainsborough was sent with a brigade to take Berkeley Castle, while Cromwell took Pickering’s brigade to take Devizes and Lacock House. Devizes town and castle had been fortified to command the county of Wiltshire and control traffic from London to the West. The governor, Sir Charles Lloyd, had a garrison of three to four hundred men. On 17 September, the town was quckly overrun forcing the garrison to retreat to the castle. Though much of the site was in ruins, the gatehouse was intact. Cromwell summoned the castle to surrender but was denied. Artillery was therefore brought up from Trowbridge and a battery of ten guns was set up in the market place, within pistol shot of the castle. The bombardment of both cannon and mortars began the next day and played on the castle all that day and night. One mortar shell even fell within the roofless keep, which was being used as a magazine, though it did not explode. This bombardment quickly persuaded the governor to discuss terms, and on the 23rd September the garrison surrendered.

Cromwell then left the brigade under Pickering’s command, and it was dispatched to Lacock House in Wiltshire. The garrison lay about twelve miles north of Devizes on the Chippenham road. It had been held at various times by either side, though the owners, the Talbots, were royalists and in the summer of 1645 Lacock was held for the King. The governor, Colonel Bovile, …

… considering that neither Bristol nor the Devizes were able to hold out against our force, did easily resolve that a Poore house was much less able; …. accordingly therefore upon the first Summons, he came to conditions to surrender …

The garrison duly marched out on 26 September. Two days later, the New Model brigade rejoined Cromwell, who was advancing on Winchester. The city, which still retained its Medieval defences, was well fortified. The garrison was based in the castle, which had been acquired as a home before the war by Sir William Waller, the early parliamentarian commaner. According to Hugh Peters, who walked around the the site after the surrender, the castle was heavily defended with six distinct works and a drawbridge … it was doubtless a very strong piece, very well victualled … as strong a place as any in England. Estimates of the strength of the garrison varied between five and seven hundred. On the 29th, in the face of unexpected resistance, the city was entered after the firing of a bridge or gate. The governor, Willam Ogle, the retreated with his troops into the castle. Cromwell wrote of these events:

I am come to Winchester on the Lord’s Day … with Colonel Pickering … After some dispute with the Governor, we entered the Town. I summoned the Castle, was denied, whereupon we fell to prepare our Batteries. …

Within four days the gun batteries were ready, but soon after the barrage began a second sunmmons was refused. The next day there was a continual bombardment, with some two hundred shots being fired. This created a stormable breach, wide enough for the entry of thirty men abreast. However, during the night the royalist soldiers began to desert and the officers demanded a parley. As a result, on 5 October, Ogle surrendered. Only two or three of the parliamentarian forces were reported as lost during the siege. In fact, Cromwell probably gained more soldiers than he lost, as some of the royalist troops enlisted with the New Model Army. With Winchester taken, the whole of the ‘West’, or ‘Wessex’, was in parliamentary hands, though not yet the far south-west of Devon and Cornwall.

Further Royalist disasters followed fast. In Scotland, three days after Bristol fell, Montrose suffered a crushing and decisive defeat at Philiphaugh. David Leslie had a significant supremacy against him in cavalry and was reinforced by seasoned troops from Leven’s army in England. Their treatment of the Irish as sub-human was common to the English and the Scots, and in this case had the full blessing of the Scottish parliament. Montrose himself made his escape, but his hopes of doing the King further service were vitiated by the mutual emnity between the Huntly and the Gordons and himself. Not knowing of his Scottish champion’s defeat, Charles set off for Chester from Raglan on 18 September, hoping once more to join forces with Montrose. The city was under siege but open from the south, and he still had Langdale’s northern horse to screen him. But on 24 September, the day after the King’s arrival in Chester, the Northern Association Horse defeated Langdale and the garrison forces.

Charles was forced to go on his travels again, with little more than a bodyguard, and he found refuge in Newark on 4 October. By then garrison after garrison had fallen to detachments of the New Model in the west; Devizes, Lacock and Berkeley Castle. Meanwhile, Rupert was so desperate to clear himself that he and Maurice skirmished their way to Newark, defying the King’s orders not to enter the city. Charles refused to see Rupert, but he obtained a hearing before members of the royal council of war, sitting as a court martial. They cleared him of any lack of courage or fidelity, but found him guilty of ‘indiscretion’ in surrendering Bristol prematurely.

The order for him to leave the country was not enforced, and eventually a sort of reconciliation was effected, so that Rupert ended the war in Oxford, though without a commission. The contrast between Charles’ severity towards his nephew and best commander and his indulgence towards Goring, whom he never reproached for failing to come to his aid when ordered to do so, makes sad reading.

(to be continued…)

Sources:

Glenn Foard (1994), Colonel John Pickering’s Regiment of Foot, 1644-1645. Whitstable: Pryor Publications.

John Haywood et.al. (eds)(2001), The Penguin Atlas of British and Irish History. London: Penguin Books.

Austin Woolrych (2004), Britain in Revolution, 1625-1660. Oxford: Oxford University Press.