The sacred site and settlement.

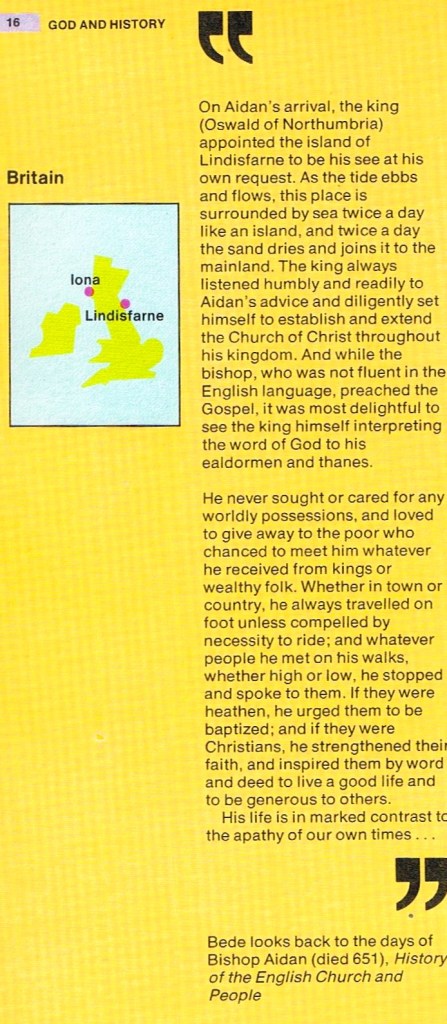

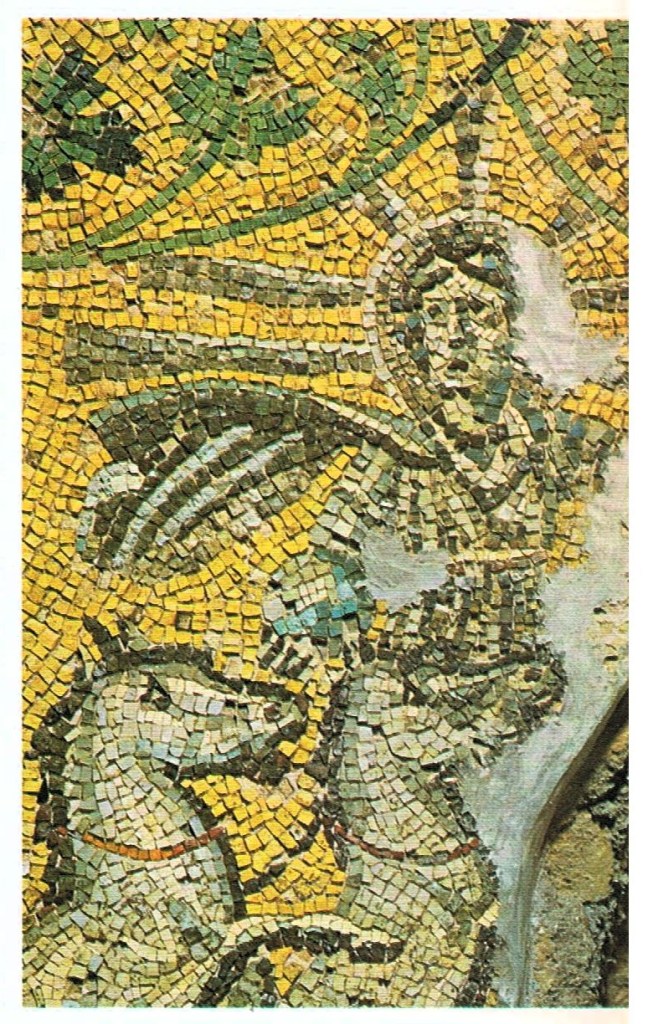

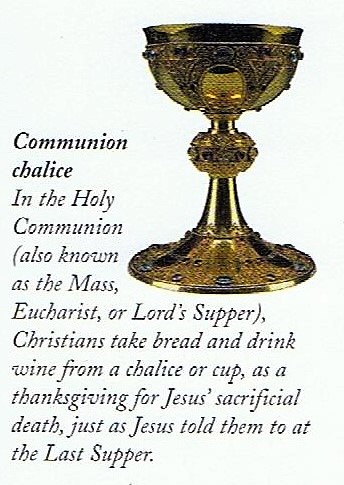

Long before its relatively recent appropriation as the site of a major music festival, Glastonbury in Somerset was intimately connected with the two linked legends of Joseph of Arimathea and King Arthur. Both were fully recorded in written form for the first time in the twelfth century, but they drew on oral traditions of much greater antiquity. According to the first of these, Joseph of Arimathea was sent by the Apostle Philip with a band of missionaries to Britain in AD 36. Joseph’s band was said to have brought the Christian faith with them, together with the communal cup used by Christ during the Last Supper.

Landing in Cornwall (reportedly at St Just-in-Roseland), they travelled towards Glastonbury and first sojourned at a hill called Wearyall. There, as the legend states, Joseph, weary from his travel, stopped to rest, thrusting his hawthorn staff into the ground where it immediately took root and, in a short time, blossomed. It is known as the ‘Holy Thorn’. From ancient times, it has been referred to as a phenomenon of nature, being the only thorn tree in the world to bloom at Christmas time as well as in Spring. It endured through the centuries as a perpetual, living monument to the landing of the saintly, ‘lost disciples’ of Christ.

The sacred phenomenon did not die. Its scion, already planted, lived to thrive and bloom as had the mother thorn tree, its snow-white blossoms spreading outwards like a beacon amid the winter gloom. Joseph settled on the present site of the abbey ruins of Glastonbury and built there the first Christian church in Britain, made of wattle and daub. This vetusta ecclesia, or ‘Ancient Church’, was said to have existed up to the great fire of 1184, when it was destroyed. In another version of the legend preserved amongst West Country miners, Joseph had been to Glastonbury before, with the young Jesus as his apprentice, who had built a simple shrine in honour of his mother. William Blake drew on the legend for his preface to his last poem, Milton, written in 1804, and which, a century later, became a popular national hymn, if not a second national anthem, set to Hubert Parry’s tune, Jerusalem:

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green?

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen?

And did the countenance divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here

Among those dark satanic mills?

Underneath the four verses which make up the hymn, Blake wrote ‘Would to God that all the Lord’s people were prophets’, and gave the biblical source from which the quotation comes: Numbers 11.29. But the imagery of the four verses is complex. Some of it is borrowed from the Bible, for instance, the chariots of fire, taken from 2 Kings 2: v. 11, but much is of Blake’s own invention. In suggesting that Jesus may have set foot in England, Blake was resurrecting the old legend which told of Christ’s visit as a young man with Joseph of Arimathea.

William Blake was born in London in 1757, but was familiar with the stories associated with Glastonbury and steeped in its ancient history. The story that found its way into his hymn told of Joseph as a metals merchant who took Jesus with him to Cornwall and the West Country in a time before England even existed, historically. There is also a verse from Blake’s long poem Jerusalem, which dates back to 1804, echoing the theme of the Lamb of God walking upon our meadows green. He expressed his heartfelt prayers for this, the Holiest Ground on Earth. In the poem, Jerusalem represents the ideal life of freedom and is a call to the values of social justice, which were to build a new Jerusalem in Britain following the First World War. In 1916, the Poet Laureate Robert Bridges included And did those feet in a patriotic anthology entitled The Spirit of Man.

In the traditions of Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire and Wales, there were longstanding claims that the teenage boy Jesus accompanied Joseph of Arimathea on a visit to Britain. According to the Talmud, Joseph was the younger brother of Mary’s father and therefore a great maternal uncle to Jesus. It is obvious from the synoptic gospels that Mary’s husband, also Joseph, the Carpenter of Nazareth, died when Jesus was young, possibly still a teenager, soon after his last appearance in the gospels on the family’s visit to the Temple in Jerusalem, when Jesus was about twelve. Under Jewish Law, such a circumstance automatically called for the next male kin of the husband to be appointed legal guardian to the family.

Ancient Historical tradition reports Jesus as a boy, frequently in the company of his great-uncle at the time of subsequent religious festivals in Judea, and that he made voyages to Britain in Joseph’s ships. Cornish traditions, in particular, abound with this testimony, and numerous ancient landmarks bear Hebrew names thought to record such visits. Although it is commonly taught that Jesus’s family was from humble origins, Joseph of Arimathea was both a property owner and a wealthy merchant at the time of Jesus’ ministry. However, when he later took up his own mission, he would have likely forsaken his material wealth.

The record shows that Joseph frequently journeyed to Gaul (known as ‘Galatia’ in Paul’s letters) to confer with the disciples there, particularly with the apostle Philip, who had arrived at Marseilles ahead of Joseph, together with ‘others’ among the early followers of ‘the Way’, men and women escaping persecution in Judea and Rome. There is a wealth of testimony asserting his commission in Gaul, all of which state that he received and consecrated Joseph, prior to his appointment as Apostle to Britain and his embarkation at Marseilles. Joseph himself is thought to have had a long association with the British through his tin mining interests in Cornwall and the West. The ancient port on the Mediterranean was the chief port of call for those transporting lead and tin from Britain. It is reputed to be the oldest city in France and its oldest seaport. Consequently, the comings and goings of Joseph’s ships would have kept them up to date with happenings throughout the Mediterranean world, including Gaul. Long before Joseph arrived on his mission to Britain, the scandal of the cross was well known to them and had caused grave concerns to the Druidic faith. That faith prepared the way for the spread of primitive Christianity in both Gaul and Britain.

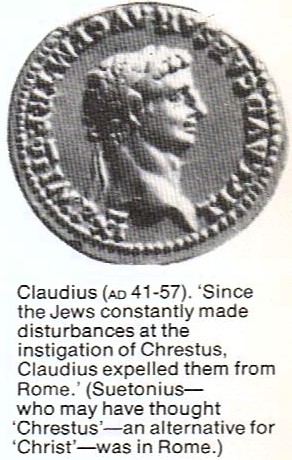

The emperors Augustus, Tiberius, Claudius and Diocletian made acceptance of both Druidism and Christianity a capital offence, punishable by death. The ancient ‘Cymry’ (Welsh) were bonded in the patriarchal faith even before they arrived in ‘Prydain’. Organised by Huw Gadarn, the faith took on the name of ‘Druid’, derived from the Celtic word for the oak tree. The prelates of the religion recognised the death of Jesus Christ as the fulfilment of their prophecy of vicarious atonement. The Roman persecutions bonded the older monotheistic faith to the new Judaistic religion of ‘the Way’.

‘The Way’, as the primitive Christian religion was known in its early centuries, found a natural haven in Gaul and its early apostolic missionaries, including Philip and Paul, found an even safer refuge in ‘the furthest reaches of the West’ of the known world, i.e. Prydain, from the Greek ‘Pretani’, or Britannia, in Latin, as it became following the Roman invasions. Up until the Claudian conquest (AD 43), the ‘British Isles’ were the only free territories in ‘southern’ Europe. Gaul had been subjected to the Roman Reich‘s persecution long before its Caesars turned their attention to the western offshore islands. It was the constant aid given to their Gaulish brethren by the Druidic warriors which eventually led to the successful conquest.

Julius Caesar’s expeditionary force of 55 BC, designed to punish Britons for thwarting his arms in Gaul, failed to establish a foothold in Britain beyond a trading post on the south coast, and it was not until the reign of Hadrian in AD 120 that Britannia was fully incorporated as a Roman dominion by a treaty through which the British ‘kings’ retained their ancestral lands, laws and rights, while accepting the nucleus of a Roman occupying legion for the defence of the ‘province’. Gaul, by contrast, was destined to become the continental crossroads of the empire.

Philip was referred to in the early Gallic church as the Apostle of Gaul, though it might be more correct to state that while he was in Gaul, he was accepted as the head of the Gallic Christian Church. The biblical and secular records show that he did not remain constantly in Gaul. Many of the early writers report that he was in Gaul in AD 65, the year in which he consecrated Joseph for the third time (the first was claimed to be in AD 36). The Epistle to the Galatians was addressed, as the ancient writers claimed, to the inhabitants of Gaul, and not to the small colony of Gauls in Asia Minor known at the time, at least to the early apostles, as ‘Galatia’. Rev. Lionel Smithett Lewis, an early twentieth-century Vicar of Glastonbury, considered the foremost church historian of his times, wrote of how Edouard de Bazelaire traced the movements of St. Paul in about AD 63 along the Aurelian Way from Rome to Arles in southern Gaul. Lewis also stated:

All this goes to prove that Gaul was known as Galatia, and their chronicling St. Paul’s and his companions’ journey does not in the least mean that they deny St Philip’s. … the Churches of Vienne and Mayence in Gaul claim Crescens as their founder. … Galatia in II Timothy iv: 10, means Gaul and not its colony in Galatia in Asia… St. Philip preached to the Gauls, and not to the Galatians in Asia.

Lewis, St. Joseph of Arimathea at Glastonbury, pp. 75-76.

The Judean Mission to Glastonbury:

Biblical tradition, supported by secular records, brought Philip to Gaul, from where he sent Joseph to Britain. The Norman chronicler, William of Malmesbury, quoting Freculphus, called Joseph Philip’s “dearest friend”, suggesting that they must have been in close association. However, Philip did not die in Gaul, but in Hierapolis, a city of Phrygia, where he was crucified at the advanced age of eighty-seven. Meanwhile, for Joseph, the way from Marseilles to Britannia lay up the Rhone Valley to Morlaix in Brittany and from there across the Channel to Cornwall. The route must have been well known to Joseph as one regularly taken by fellow traders, seeking ore. From Cornwall, an ancient road led to the lead mines of the Mendips, remains of which still exist, passing close to Glastonbury.

To most people, Joseph of Arimathea is passingly remembered as the rich man who kindly offered his private sepulchre for the burial of Christ. Beyond that, we find references in the gospels to him as ‘Decurio’, a common term employed by the Romans to designate an official in charge of metal mines. It indicated that he held a prominent position in the Roman administration as a minister of mines. Tin was the chief metal for the making of alloys and was in great demand by the empire-building Romans. Many historians have claimed that Joseph’s wealth and influence were the result of his vast holdings in the ancient tin mines of Britain.

The bulk of the first century’s supplies of tin and lead were mined in Cornwall and Somerset. The tin was smelted into ingots and exported throughout the known ‘civilised’ world. Joseph was reported as owning one of the largest merchant shipping fleets of the time, traversing the world’s sea lanes in the transportation of the precious metal. In particular, the trade between Cornwall and Phoenicia was frequently referred to by classical writers and described at considerable length by Diodorus Siculus as well as by Julius Caesar.

The art of enamelling was identified with the Ancient Britons, just as was the production of tin. They were so skilled in this craft that relics in the British Museum and the Glastonbury Museum, such as the famous Glastonbury bowl, over two thousand years old, and the Desborough mirror, are as admirable as the day they were made. They are magnificent examples of “La Téne” art, as the Celtic design is named, their geometric beauty and excellence being beyond the ability of modern craftsmen to duplicate. The same can be said of the finds from the Sutton Hoo ship burial, emphasising the continuity of Celtic design into the enamelling of the post-Roman and early medieval periods, also on display at the British Museum. Roman testimony states that captive Britons taught the Romans the craft of enamelling. The Anglo-Saxon enamellers also learnt the craft from the Romano-British, among whom they settled in the sixth century. Modern ethnographers and historical linguists have charted the earlier Celtic migrations from their ancient homelands in eastern Europe to their final destinations in Gaul and Britain.

Proof of British superiority in the tin industry and its affluent worldwide trade was referred to by Herodotus as early as BC 450, when the islands were known as the Cassiterides, meaning The Tin Islands. This reference was followed by several others, each of which explained the paths of transportation from Britain overland and by sea to the various Mediterranean ports. The tin that garnished the Palace of Solomon in BC 1005 was mined and smelted into ingots in Cornwall and thence shipped by the Phoenicians to Palestine, where it supplied the adornment to his temple. The association of Joseph of Arimathea with the tin industry in Cornwall has been echoed down the centuries in fragments of poems and miners’ songs making reference to Joseph, such as ‘Joseph was a tin man’ and ‘Joseph was in the tin trade.’

Nevertheless, for a Jew to have held such a high rank of Nobilis Decurio in the Roman Empire was somewhat rare. We also know that he was a prominent member of the Sanhedrin, the Jewish Council in Judea that ruled over Roman Jewry. Everything known of him suggests that he was an affluent person of importance and influence within both the Jewish and Roman hierarchies. But his story is also an important chapter in the story of Britain, since he became known as the Apostle of Britain, establishing its first church at Glastonbury. From this base, Joseph is said to have frequently journeyed to Gaul, to Marseilles and Arles, to confer with the exiled disciples there, led by Philip. As George B. Jowett wrote in his 1961 book, The Drama of the Lost Disciples, from this apostolic connection grew the seeds of organised Christianity in ‘the West’:

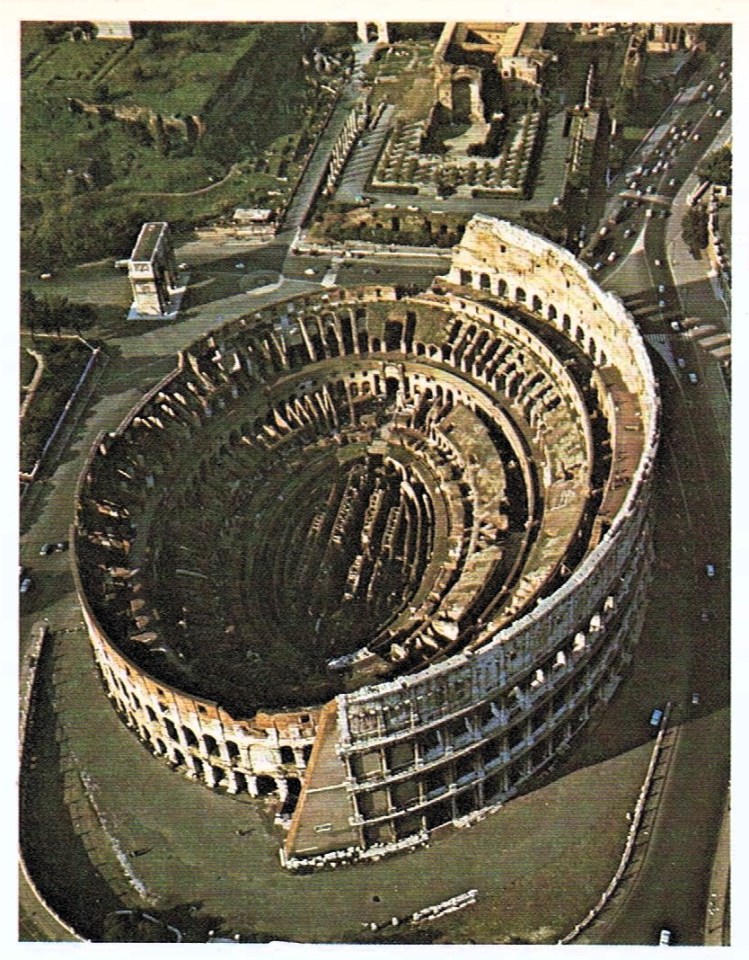

Thus began the epochal drama that was to change imperial destiny and lead the peoples of the world to a better way of life. Yet, before this was to be fully achieved, millions were to wade their way through unbelievable tragedy, defying tyranny in its basest and most terrifying form, wholesale massacre and fiendish torture, suffering the brutalities of the Colisseum, the horrors of the fetid prison… and the dreadful scourging wars in which the British were to make the most colossal sacrifice in blood and life known to history.

Jowett (1961), p. 62.

Arviragus appears in the first-century legends of early British kings as a British opponent of the Romans. Geoffrey of Monmouth described him as the king of the Silures of Britain, son of King Cymbeline (Cunobel), the brother of Guiderius and cousin of the legendary warrior-patriot, Caradoc (Caractacus). According to Geoffrey, Cymbeline gave up the helm of state to Guiderius, but when he refused to keep paying the tribute demanded by the Romans, Claudius, who had been raised to the empire, invaded the island. His commander-in-chief, named Levis Hamo in the Cymric tongue, which he had learnt, tricked Guiderius and the Britons into an attack on the Roman army, which was a pyrrhic victory, because Hamo then assassinated Guiderius.

Arviragus, pretending to be his brother, cheered on the British army and defeated the Romans in a further open battle. Hamo slipped away into the forest, and Claudius fled to his ships on the south coast. Arviragus was too quick for Hamo, who was unable to board the ships and was killed. Claudius attacked Caerperis (Porchester), casting down its walls and pursuing Arviragus to Winton, besieging the royal town. Arviragus sallied out to fight, but Claudius offered a truce, which the British king was persuaded to accept by his own courtiers. By this, Claudius gave his daughter in marriage to Arviragus, and the British king agreed that Britain would become a fiefdom of the empire, a province with Gloucester as its capital.

Several centuries after Joseph’s time, St Augustine confirmed the tradition of the wattle and daub altar in a letter to Gregory, Epistolae ad Gregoriam Papam, stating that the shrine still existed on the site. Consequently, we may believe that it was also there when Joseph and his twelve companions arrived in Glastonbury to establish their mission. With the chartered gift of land to the Josephian Mission, Arviragus promised his protection. In return, the cross, as the Christian symbol of Royal heraldry, was given to Arviragus by Joseph and the cross on the shield became the special symbol of the sovereigns of Britain centuries before its associations with the Crusades, England and St. George. Arviragus carried the banner of the Cross through the most bitterly fought battles between the Britons and the Romans. However, his fame was overshadowed by Caractacus, or Caradoc. Despite this, Arviragus was the most powerful representative of the royal house of the Silures and the most famous Christian warrior in Romano-British history.

Arviragus’s reception of St. Joseph suggests a previous acquaintance, and testimony from the Early Fathers from various branches of the Church shows that Glastonbury was an early Christian site. The Magna Glastonensis Tabula was a manuscript quoted by John of Glastonbury and William of Malmesbury. It records that Philip sent Joseph, his son, and ten other disciples, and ultimately that one hundred and sixty were sent to Britain in groups at various intervals by Philip to serve Joseph in his evangelistic mission. Arviragus’s grandson, King Lucius, succeeded him and was buried at Gloucester in AD 156. He renewed and enlarged the charter with the Glastonbury Christian mission, and early in his reign, he was baptised at Winchester by his uncle, Timotheus, who also proclaimed him ‘Defender of the Faith’. Geoffrey informs us that, even before King Lucius formally accepted Christianity, a ‘Papal’ legation had returned to Britain, …

… with a passing great company of others, by the teaching of whom the nation of the British was in a brief space established in the Christian faith.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Histories of the Kings of Britain, 1912 edn., Book IV, Chapter XX, p. 74.

The royal territories of the Silures were divided into two. Arviragus ruled over the southern part of what later became England, including Somerset, and Caradoc ruled over Cambria, the region which became (south) Wales. Each was king in his royal domain, but in time of war, they combined forces under a ‘Pendragon’ or Commander-in-Chief. When Caradoc was taken captive to Rome, Arviragus took over from him as Pendragon, conducting a war of resistance against the Empire for decades in Britain, as recorded by Tacitus, the Roman historian, in his Annals of the Conquest. (bk. 5, ch. 28). Another Roman writer, Juvenal, indicated how greatly the Romans feared Arviragus, and that no better news could be received at Rome than the fall of the Royal Christian Silurian. Such was the invincible spirit of the Silures that they formed a living wall around the sacred boundaries of Avalon in Arviragus’s domain. No Roman army ever pierced its perimeter, and Roman writers referred to it as ‘territory inaccessible to the Roman where Christ is taught’. Behind the living wall of warriors, Joseph and his companions were safe from persecution, free to teach and preach the Christian faith from its first planting on the Sacred Isle.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s primary source for this official dating of the conversion of Britain to ‘Roman’ Christianity was the British monk, Gildas’s sixth-century book concerning the victories over the invading Saxons of Ambrosius Aurelianus (his name for Arthur), which Geoffrey chooses not to quote extensively. Nevertheless, a “Life” of Gildas was written by Caradoc of Llancarfan, a friend of Geoffrey of Monmouth and his Anglo-Norman patrons. This is an entirely fictional account intended to associate Gildas with Glastonbury Abbey and with King Arthur. Arthur kills Gildas’s brother Hueil, which causes enmity between them for a time. Hueil’s enmity with Arthur is also mentioned in the later Welsh prose tale Culhwch and Olwen, written around 1100. Gildas is best known for his polemic De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, written in c. 490, which recounts the sub-Roman history of Britain, and which is the only substantial source for the history of this period written by a near-contemporary Briton, although it is not intended to be an objective chronicle. At the beginning of Book V of his Histories, Geoffrey tells us more about the process of conversion:

Meanwhile, King Lucius the Glorious, when he saw how the worship of the true faith had been magnified in his kingdom, did rejoice with exceeding great joy, and converted the lands and revenues which formerly did belong unto the temples and idols unto a better use, did by grant allow them to be still held by the churches of the faithful. And for that it seemed to him he ought to show them yet greater honour, he did increase them with broader fields and fair dwelling-houses, and confirmed their liberties by privileges of all kinds.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Histories (1912), p. 75.

From a historical perspective, the suggestion that the teenage Jesus visited Glastonbury with Joseph seems no more than a myth. Still, it seems entirely possible that Glastonbury received the first Christian Mission in Britain. William of Malmesbury, a twelfth-century monk from Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire and author of various authoritative chronicles, wrote, from his research in the library of Glastonbury Abbey, De Antiquitate Glastoniensis Ecclesiae, the primary Christian source about Glastonbury. He records a second-century foundation of Christianity in Britain, but cautiously entertains the possibility that when the Bishop of Rome’s emissaries arrived at Glastonbury, they discovered an already established church, a wattle-and-daub structure, set amongst a dozen huts or cells, later a great draw for pilgrims and known as the Old Church. At about the same time, other chroniclers began to build on Glastonbury’s earlier reputation as a sacred burial ground or kingdom of the Underworld.

The Arthurian Mythology:

Geoffrey of Monmouth first mentioned Avalon as King Arthur’s burial site in his Historia Regum Britanniae:

Arthur himself, our renowned King, was mortally wounded and was carried off to the Isle of Avalon, so that his wounds might be attended to.

By the time Geoffrey was writing, the Cambro-Norman chronicler, Giraldus Cambriensis, had already identified ‘insula Avallonia’ with Glastonbury as Arthur’s resting place. With their wholly compatible codes, Christian and Arthurian mythologies were inseparable to begin with, but when the Arthurian stories obtained greater and more widespread popularity by the end of the twelfth century and became more important than the ethics they were supposed to represent, tensions arose. Robert de Boron’s thirteenth century romance, Joseph d’Aramathie cast Joseph, the rich disciple who obtained permission from Pilate to remove Christ’s body to his own tomb, as the earliest founder of Christianity in Britain. In the context of William of Malmesbury’s work, this was an acceptable idea to the monks at Glastonbury, but de Boron also had Joseph bring with him the Cup of the Last Supper in which he had caught the blood of the crucified Christ. This identified the Glastonbury Chalice as the Holy Grail and raised the standing of the great totem of Arthurian myth to the most exalted heights. When the word spread that the Grail had been found in a stony nook beneath the waters of the Chalice Well, the stream of pilgrims became a flood. It was then, in 1190-91, that, rather than tempering the rumours, the monks declared they had turned up the bodies of Arthur and Guenevere from sixteen foot underground.

Malory’s more romantic account in Le Morte D’Arthur came more than two centuries later, but he brilliantly formalised the relationship of the myth to the landscape:

Then Sir Bedevere took the king upon his back, and so went with him to that waterside, even fast by the bank, hoved a little barge with many fair ladies in it, and among them all was a queen, and they all had black hoods, and they all had black hoods, and they all wept and shrieked when they saw King Arthur.

‘Now put me into the barge,’ said the king.

And so he did softly; and there rerceived him three queens with great mourning; and so they set them down, and in one of their laps King Arthur laid his head. …

… And so then they rowed from the land and St Bedevere beheld all those ladies go from him.

Then Sir Bedevere cried, ‘Ah my lord Arthur, what shall become of me, now ye go from me and leave me here alone among mine enemies?’

‘Comfort thyself,’ said the king, ‘and do as well as thou mayest, for in me is no trust for to trust in; for I will into the vale of Avilon to heal me of my grevious wound: and if thou never hear more of me, pray for my soul… ‘

Malory leaves Sir Bedevere with the hermit ‘in a chapel beside Glastonbury’ with Arthur’s tomb ‘new graven … and so they lived in their prayers, and fastings, and great abstinence.’

In the 1580s, the intrepid Queen Elizabeth Tudor, direct descendant of Arviragus and Lucius, made the Reformation declaration, when challenging the authority of the combined forces of France, Spain and Rome, that Britain’s priority in the Christian Church stemmed not from Papal authority, but from the ancient oath of the British King Lucius. As her ancestors had done, she declared that only Christ was the Head of the Church, and ever since, on their coronation, the sovereigns of Great Britain (and sometimes Ireland) had taken this oath. In 1953, the Roman Church petitioned for this oath to be omitted from the coronation of Elizabeth II, but this was refused by ‘the establishment’ with the statement that the United Kingdom was the one true defender of the Christian cause in Britain, with Christ as its Head.

Joseph was said to have brought the Holy Grail with him to Glastonbury and to have buried it in an unknown place near his first settlement there, thus connecting it with the legend of King Arthur and his knights searching for it. It is thought to be marked by the site of the Chalice Well at the foot of the Tor. Glastonbury was therefore identified as the ancient Isle of Avalon, the island of apples (‘apple’ being ‘afal’ or ‘aval’ in Cymric) to which Arthur was borne in the legend following his last battle with Mordred. This association of Glastonbury with Arthur received a boost in 1191 when a monk at the abbey, inspired by a vision, claimed to have discovered the tomb of Arthur and Guenevere. The coffin bore on it the inscription:

‘Here lies the famous King Arthur buried in the Island of Avalon.’

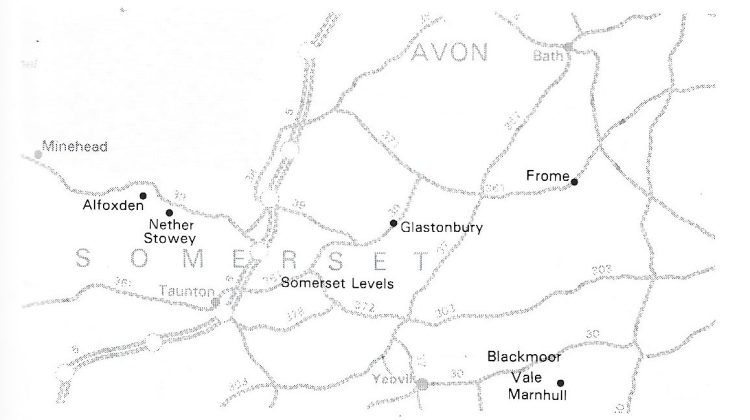

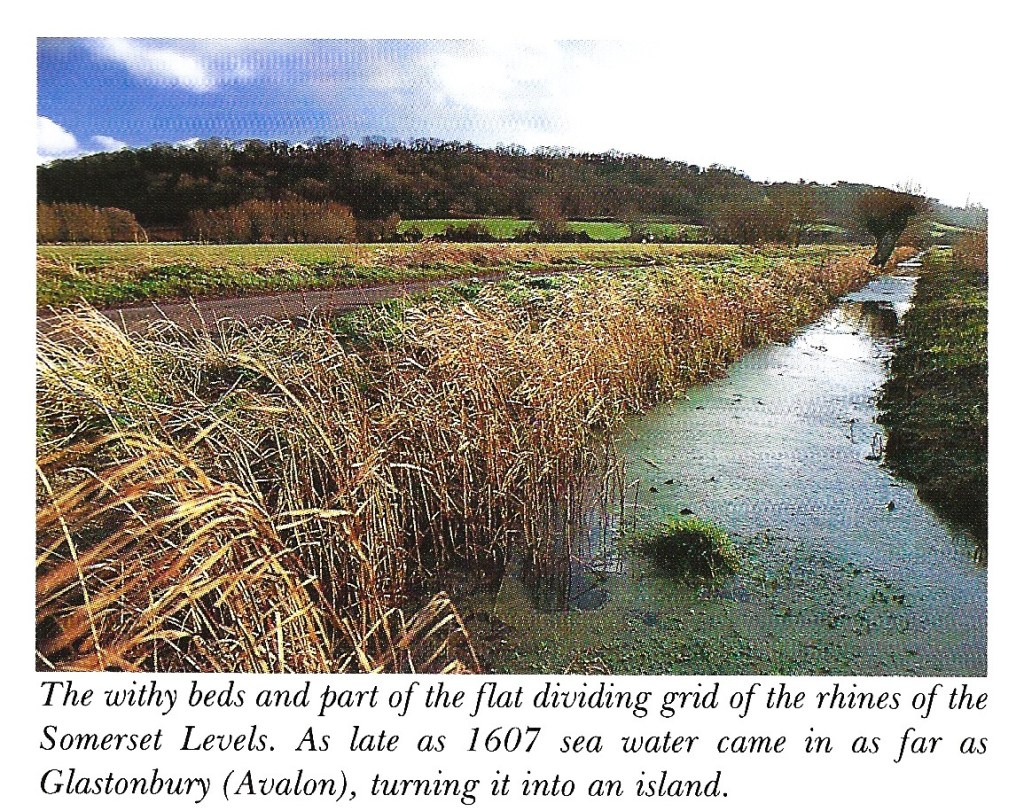

When it was opened, it was found to contain the skeletons of the king and his consort. The still blonde tresses of Guenevere’s hair apparently crumbled in the hand of the monk. It is not surprising that Glastonbury should be associated with such powerful legends, located as it is on the Somerset Levels, much of which was under the Severn estuary until drained by Dutch engineers in the later seventeenth century. Dr John Dee, the Welsh mathematician and astrologer to Elizabeth I, developed the theory that the landscape was part of the immense depiction of the twelve signs of the zodiac formed by rising ground, streams, ancient roads and field boundaries. Long before the eighteenth century, when ditches, or rhynes, were dug, enclosing fields and organising better drainage. The area developed its own culture, the willows along the flowery edges of the rhynes supporting a thriving basket-making industry.

The extraordariness of Glastonbury Tor begins with its physical characteristics, its visibility for miles around, the smooth greeness and shape of the mound, which makes it suspiciously man-made, like a Norman ‘motte’, the narrow terraces that circle the summit which appear to form a convoluted maze with the ruin of St Michael’s Church at its core, and the quality of the spring that flows fom its flank down to the Chalice Well, crystal clear water trailing red as blood due to the iron ore in its course. In fact, the hill is composed of clays and limestones in horizontal strata that have gradually eroded. The phenomenon of red water is the oxidation of the naturally high iron content that occurs upon contact with air. But this does not challenge the mystical spirit of the place that has been impressive for thousands of years in a variety of cultures.

Originally surrounded by marsh and water, the four-hundred-foot Tor with Chalice Hill and the site of the abbey and town all formed a single island, Avalon, on the low, flat Somerset plain. Seen across ‘the Levels’ on a misty day or evening, they still give the appearance of insularity. The Levels stretch westwards towards Bridgwater Bay, being liable to flooding in winter from the Axe, Brue and Parrett rivers. It has been suggested that the Celtic Christian monks, known as Culdees, who first founded a settlement here were inspired to make this ancient holy place a hallowed site of the new faith. It has also suggested that the Tor itself, a strange cone now crowned by the tower of the medieval church of St Michael, was, from the Bronze Age or even earlier, a site of initiation, a three-dimensional maze traced by a spiral path around its mound.

Within a mile of the Sacred Isle of Avalon was another smaller island known as Ynys Wytren, or Glass Island, a name with a claim to be derived from the still, pure waters that once surrounded it when much of the ‘Somerset Levels’ were almost permanently under water. In Saxon times, the water receded in the Summer to reveal a ‘summer pasture’, giving the name ‘somer saete’ to the whole county. Excavations have also revealed that it was once a busy site for the glass industry, for which the ancient Britons were famous, alongside their enamelling and metalworking. Later, the Saxons named it Glastonbury, though the word ‘Glas’ in Welsh means ‘blue’, which may have been a reference to the incoming seawater from the Severn estuary. Today, the western boundary of the lowland area is known as ‘the Levels’ and the eastern flood plains as the Moors. Behind the clay banks of the Levels, tides rise many feet higher than the Moors, and even as late as 1607, after considerable engineering works first by the Romans and then throughout the Middle Ages, sea water could still come in as far as Glastonbury itself.

During Anglo-Saxon times, some of the ‘isles’ ceased to exist as the monks at Glastonbury Abbey drained much of the land around them, creating a muddy salt plain, though it is still, today, below sea level, and swampy in wet weather. Yet today, as pilgrims realise that they are standing in the centre of the twelve hallowed hides of land which the Silurian prince deeded to St. Joseph and his twelve companions, it is impossible for them not to feel moved by the beauty of the scene in what is still, for most of the year at least, the quiet little English town, encircled by verdant meadows, all part of the 1,920 acres of early Christendom. At the same time, it is difficult for them to fully comprehend that they are treading on the same holy ground where the early saints trod and communed together. There is good evidence to suggest that they may have included Aristobulus, a successor to Joseph as apostle to the Britons.

The magnificent ruins of Glastonbury Abbey are the remains of the beautiful church that was erected over the altar of the wattle-and-daub shrine, thatched with reeds from the wetlands below, as was the custom of the time. Wattle was the common building material of the ancient Britons, as well as the Saxons who followed them to the area, and they used it in the construction of their homes, halls, and churches. Therefore, Joseph and his fellow disciples did not employ unusual materials, but only those which were then of common order. A former Bishop of Bristol commented on excavations at nearby Godney Marsh, discovered by Arthur Bulleid in 1892 and excavated over the following fifteen years. Another was unearthed at Mere. Settlers were first drawn there in pre-Celtic times, and not just by the abundant stocks of fish and fowl. Ever since the discoveries, there has been speculation about the name ‘Glass Island’. Nature’s glass, quartz stone, was being used in Bronze Age tombs and as ceremonially significant pillars in stone circles, such as at Boscawen (Penrith) in Cornwall and places of ritual sacrifice.

The ‘Lake Village’ has been described as “the best preserved prehistoric village ever found in the United Kingdom”. The site covered an area of 400 feet (122 m) north to south by 300 feet (91 m) east to west. It was first constructed 250 B.C. by laying down timber and clay. Wooden houses and barns were then built on the clay base and occupied by up to two hundred people at any time until the village was abandoned around 50 B.C. Artefacts uncovered include wooden and metal objects, many of which are now on display at The Tribunal in Glastonbury High Street and in the Museum of Somerset in Taunton. Bishop Brown observed that:

Wattle work is a very perishable material, and of all things of the kind, the least likely is that we in the nineteenth century … discover at Glastonbury an almost endless amount of British wattle work. Yet this is exactly what happened. In the low ground, now occupying the place of the impenetrable marshes which gave the name of the Isle of Avalon to the higher ground, the eye of the local antiquary had long marked a mass of dome-shaped hillocks, some of them of a very considerable diameter, and about seventy in number, clustered together in what is now a large field, a mile and a quarter from Glastonbury. …

The hillocks proved to be the ramains of British houses burned by fire. They were set on ground made solid in the midst of waters, with causeways revetted with wattle work … all over. … The wattle when first uncovered is as good to all appearances as the day it was made. The houses of the Britons at Glastonbury … and their church were made of wattles.

Rev. G. F. Brown, The Church in These Islands before Augustine.

Soon after Joseph and his company had settled in Avalon, they began, painstakingly, to construct their wattle church. It was reported as being sixty feet in length and twenty-six feet wide, following the pattern of the Tabernacle in Jerusalem, still standing at the time of the Roman destruction of it in AD 70. St. Paulinus had the wattle church encased in local lead from the Mendips in AD 630 and, thus protected from dissolution, it remained intact until 1184, when the whole abbey was destroyed by fire. By then, the cross-shaped pattern of the wattle church at Glastonbury had become the model employed in the construction of all the early British churches built in Roman, Anglo-Saxon and early medieval times. But its first function was to provide sanctuary for the refugees from the persecution of the Sanhedrin and pagan Rome. Protected by the armed might of the Silures, the companions of the Apostle of Britain began to teach Christ crucified in the sunlit combes and vales of the Western islands of Britain.

Speculation that Glastonbury was a seat of the Old Religion (Druidism) or a sacred burial site was fuelled by legend. St Collen was an early Celtic Christian settler who built his cell at Glastonbury and upset the settled people there by denying that the Tor was the entrance to the Underworld, the domain of Gwyn ap Nudd. When the hermit was introduced to it, as the folk story went, a fine castle within the hill, he sprinkled holy water on it so that it disappeared. John Cowper Powys explained:

In the ethnic atmosphere about these two, as they stood there, quivered the immemorial Mystery of Glastonbury. Christians had one name for this Power, the ancient heathen inhabitants of this place had another, and a quite different one. Everyone who came to this spot seemed to draw something from it, attracted by a magnetism too powerful for anyone to resist, but as different people approached it changed its chemistry, though not its essence, by their own identity, so that upon none of them it had the same psychic effect. … Older than Christianity, older than the Druids, older than the gods of Norsemen or Romans, older than the gods of the neolithic men, this many-named Mystery had been handed down to subsequent generations…

John Cowper Powys, A Glastobury Romance.

Behind the church rose the great Tor, a Druidic centre for a Gorsedd, a High Circle of Worship, a hand-piled mound of earth with terraces that wind around the hill to its summit. On these eminences, the Druids had their astronomical observatories from which, like the sages of Persia, they studied the heavens and the movements of the stars and their relationships to ancient prophecies. The merging of the Celtic Druidic traditions with early Christianity had already become an accepted process, peacefully performed. Archaeological evidence has also demonstrated that there was no bitter opposition between the Druidic priests and the Christian apostles. Nowhere in the Celtic and Cymric records is there any mention of antagonism between the two faiths. The Archdruids recognised that the old order was fulfilled according to prophecy, and that with the advent of the Messiah, Christ, and his atonement, the new dispensation had arrived. In the light of the understanding reached between them and the Judean refugees, their common resistance to pagan Roman persecution bound the two religions together.

The Augustinian mission of AD 596, sent by the Roman prelate Gregory, later erroneously referred to as a ‘Pope’, was actually part of the first attempt to introduce Roman Christianity to Britain. Even the earliest Vatican historians referred to St. Joseph as the first Apostle of Britain and the first to introduce Christian teachings to the Islands. Subsequent popes have also substantiated this statement. St Paul was actually the first to deliver the Roman Christian message to Britain, at first through his appointed apostle, Aristobulus. St Joseph was not sent from Rome, but went directly from Palestine, via Marseilles, preceding both Aristobulus and possibly Paul himself by two decades. Theodore Martin, of Lovan, wrote at the beginning of the Reformation in continental Europe, that:

Three times the antiquity of the British Church was affirmed in ecclesiastical councils: 1. The Council of Pisa, AD 1417; 2. Council of Constance, AD 1419; 3. Council of Siena, AD 1423. It was said that the British Church took precedence over all other Churches, being founded by Joseph of Arimathea, immediately after the passion of Christ.

Disputoilis super Dignitatem Anglis it Gallioe in Councilio Constantino, AD 1517.

Alfred the Great’s erudite chief minister and chronicler, Bishop Ussher, also stated, without equivocation, in his Britannicarum Ecclesiarum Antiquitates that the British National Church was founded in AD 36, a hundred and sixty years before heathen Rome confessed Christianity. The founding of a British national church by the Josephan Mission led to rapid conversion throughout the Isles. In AD 48, Conor Macnessa, King of Ulster, sent his priests to Avalon to commit Christian precepts and teachings into law, naming them ‘the Celestial Judgments’.

The Roman Pauline Mission:

About twenty years after Joseph’s arrival, there was a second Christian mission, also established under the protection and sponsorship of the Royal Silurian House, and under the commission of St. Paul. By this time, the Romans in Britain had become the implacable foe of the British Christians and sought by every means at their command to exterminate the new movement at its source. At the same time, they held the British warriors in high esteem and believed their religion was the reason for their fearlessness in battle and disdain of death. Lucanus, writing in Pharsalia in A.D. 38, argued that this indifference of the Britons to death was due to their religious beliefs, and Pomponius Mela, writing three years later, described, with astonishment, the British warriors as extraordinarily brave, which he ascribed to their religious doctrine, based on the immortality of the soul.

After his contact with the royal family of the Silures in Rome, Paul declared in his statement, I turn henceforth to the Gentiles. The family were destined to become the first martyrs to suffer for the Gentile Church, and millions more were soon to follow their example. The underground cemeteries of Rome, the Catacombs, were packed with the tortured, murdered bodies of Christian men, women and children from this period, just as British soil was saturated with the blood of martyrs, eternal testimony to their steadfast faith. Believing that Christ had died for them, they were fearless in dying for Christ.

The Romans had not previously held any special animosity towards the British, though they always despised the Jews. This hatred was now intensified by the Claudian Edict, which accused them of being responsible for the rise of the new faith, finding its converts among the people of Judea. Seeking further to inflame the citizens against both through the slander that Christians and Jews alike practised human sacrifice in their religions. However, they knew better that the burnt offerings of both Judeans and Druids were animals, chiefly sheep, goats and doves. The Romans also spread the age-old blood libel that the Jews devoured Gentile babies.

Throughout the nine-year Claudian campaign, the Irish and Pictish records tell of an ever-flowing stream of delegates from the various kingdoms, journeying to Avalon to receive at first-hand instruction from the Arimathean Culdees. Had it not been for this movement, Paul would almost certainly have been seriously handicapped in carrying out his mission to the Gentiles. The long-established, inter-generational familial associations between the Britons and the Romans in commerce, culture and social affairs had made both peoples conversant with each other on common grounds. Latin was not adopted in British ecclesiastical liturgies until the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Yet, from the first to the fourth century, it was as familiar to the Cymry as was Greek or Hebrew. Through the Arimathean and Pauline missions, the Silureans eventually conquered Rome for Christ.

Among the earliest British hostages in Rome was Llyr Llediaith, grandfather of Caradoc. He died shortly after he arrived in Rome, and his son, Brán, became the Archdruid Silurian monarch who abdicated in favour of his son, Caractacus, who had offered himself as a hostage to replace his father, Llyr, the King Lear of Shakespeare’s play. These characters, gathering at the ‘House of Apostles’ in Rome, were to play a major role in the continuing drama of the ‘lost’ disciples under the direction of the Apostle Paul. Even though the apostle had his residence in Rome provided for him by the Christian following, the Scriptures state that he only resided there for two years during his ten years in the city. The common inference is that St Paul arrived in the city in A.D. 58, though his arrival could have been two years earlier. St Jerome wrote that Paul arrived in Rome in the second year of Nero, who succeeded Claudius as emperor.

In the year AD 58, the Pauline mission was ready to leave Rome to begin their work in Britain in the territorial section then known as Cambria, later Wales. Aristobulus was installed as the first Bishop of Llanulltid, with Brán remaining as Archdruid and High Priest of Siluria at Llandaff. In the Cymric language, Aristobulus was known as Arwistli-Hén and Arwystli-Senex in Roman-Latin. Unfortunately, the aged or ‘hén’ Aristobulus met a tragic end within a year of his return to Britain. The Pauline Mission had come directly from Rome, and the inveterate hatred of the British for all things Roman was unrelating. Brán wrote in his journals that they were hard pressed to induce the British to accept anyone or anything that came from the imperial city. It was only their love for the devout Brán and Eurgain of Old Sarum (Caer Salog; Salisbury), the Patroness of the Pauline mission among the Silures, that made them willing to receive the Roman Christian missionaries. Aristobulus was well respected among the Silures. He was a Greek Christian who had come to Britain from Jerusalem via Galicia, on the Atlantic coast in Northern Spain. He was also previously known to Joseph and the Avalon Mission.

On his missionary journeys in Britain, Aristobulus journeyed far beyond the territory of the Silures into the lands of the Ordovices, whose hatred for the Romans was even more bitter and certainly blacker than that of the Silures. The Roman missionary was also unknown to them, and they were justifiably suspicious that his appearance was yet another Roman trick and that he was really an imperial spy. According to Cardinal Alford’s Regia Fides, the Ordovices rose up and slew him in the year AD 58 or 59. He was martyred at what later became St Albans, following the Diocletian martyrdom of the saint of that name. Aristobulus, therefore, became the first Romano-British martyr and the only one to be martyred by the Celtic tribes. When the Ordovices were informed of the misunderstanding, they were remorseful. They erected a beautiful church on the site of his martyrdom.

Following the death of Aristobulus, the Princess Eurgain became the leader of the Pauline Mission. She was the first female convert in Britain and the first female Christian saint. She founded twelve colleges for Culdee initiates at Cor Eurgain. Ilid, ‘a man of Israel’, a Judean convert who had accompanied Bran and Aristobulus to Cambria, took charge of the mission until Paul arrived. He was a Judean convert from Rome and was shown to be a very capable, energetic leader. Financed by the royal Silurian family, a magnificent church and university were built, and many new schools were built throughout Cambria. The Iolo manuscript says of Ilid:

He afterwards went to Glastonbury, where he died and was buried, and Ina, King of that country, raised a large church over his grave.

King Ina’s church at Glastonbury Abbey, built in AD 700, was excavated in the 1950s. The loss of his aged friend, Aristobulus, was a great blow to Paul, who sent his salutations to his friends at Rome. The last epistle Paul sent out from prison was to his fellow apostle, Timothy, requesting him to deliver his (last) greetings or benedictions to the ones he loved dearest on earth, to his sister-in-law, Claudia, and her husband; his half-brother, Pudens; to their children and to his nieces and nephews, whom he had taught; the beloved Linus, whom he had consecrated and appointed First Bishop of Rome, Linus; to Eubulus, cousin of Claudia, and them which are of the household of Aristobulus. In only ten years, Paul had faithfully carried out his commission to go to the Gentiles. He had established the First Christian Church in Rome and undertaken a mission to Britain in collaboration with the Josephan Mission at Avalon and the members of the British royal Silurian family.

It is claimed that Paul landed at what is now a suburb of the great naval port of Portsmouth, from where ferries still arrive from Brittany and Northern Spain. It has been known over the centuries as ‘Paul’s Grove’. From there, he made his way into Cambria, to Bangor-on-Dee, where (it is claimed) he founded the famous abbey, destroyed in 613 by Aethelfrith of Northumbria after he defeated the Welsh armies at the Battle of Chester and slaughtered the monks. The doctrine and administration of the Abbey was known as Pauli Regula, ‘The Rule of Paul’. According to R. W. Morgan, author of St. Paul in Britain, the abbots all considered themselves as direct successors of Paul, although other records show it to have been founded by Dunod in the mid-sixth century. It’s doubtful that Paul stayed long enough in Britain to see the abbey completed, even as a simple construction. Certainly, it could not have been the monastery described by St Hilary and St Benedict as the ‘Mother of Monasteries’, and by Bede as having over two thousand resident monks.

A casual study of the life and works of St Paul, after his arrival in Rome, shows a ‘blank period’ of six years. Many scholars now believe that those years were spent in Gaul, and principally in Cambria. We know (from his letters) that he returned to Rome from there in AD 61, and that he was reinterned there, and that he also returned to Arles, in southern Gaul, where he was obliged to leave one of his sick companions from Rome. In Cambria, as in Gaul, the memory of Paul’s sojourn was almost entirely lost or became fabricated parts of later legend. The only enduring ‘traces’ of his visit are found in ‘Llundain’ or Londinum, where he is said to have preached from the summit of Ludgate Hill, the original site of the old St. Paul’s Cathedral. Arising from this legend, London has been referred to as the ‘Aereopagus’ of Britain, and the exact spot of his preaching may well be marked by the ancient St. Paul’s Cross. The emblem associated with him, the sword of martyrdom, was incorporated in the coat of arms of the City of London.

A common question often arises concerning the apostles’ ability to preach to the people in the various languages of Britain. Since it is unlikely that Paul could use a Cymric tongue for this, we may assume that he spoke in Latin, which was well-known among the educated Romano-British. However, we know that he wrote fluently, in Greek, the most widely comprehensible language of the first-century Mediterranean world. It was not until the time of Charlemagne that Latin became the language of church services. It was imposed by Pope Gregory I on much of Europe in AD 600, but the Celtic Church in Britain opposed this until the end of the seventh century. Bishop Ussher, chief advisor to Alfred the Great, writing in his Historia Dogmatica, claimed that:

No two causes contributed so much to the declension of Christianity… as the suppression by the Church of Rome of the vernacular scriptures, and her adoption of image worship.

Had it not been for the vigorous support of the Pauline Mission in Cambria by the Princess Eurgain and her relatives, his efforts might have failed completely. The success of his mission was undoubtedly due to its sponsorship. Following the martyrdom of Aristobulus, the Cambrian church renewed its close ties with Avalon. The common people their allegiance never deviated from Joseph or the Mother Church there, while they could not and did not accept leadership from Rome. However, Paul fulfilled his own mission, to go far hence unto the Gentiles, and the magnitude of his achievements is summed up by St. Clement, who followed Linus as Bishop of Rome at the end of the first century:

Paul,… having seven times worn chains, and being hunted and stoned, received the prize of such endurance. For he was the herald of the Gospel in the West as well as in the East, and enjoyed the illustrious reputation of the faith in teaching the whole world to be righteous. And after he had been in the extremity of the West, he suffered martyrdom before the sovereigns of mankind…

1 Clement 5: 6-7.

‘Extremity of the West’ was the term used by Romans to indicate Britain, though it was also used by Paul himself to refer to western Gaul, especially Galicia in northern Spain. In his History of the Apostles, Capellus wrote:

I know scarcely of one author from the time of the Fathers downward who does not maintain that St Paul, after his liberation, preached in every country of the West, in Europe, Britain included.

Theodoret, writing in the fourth century, claimed that St. Paul brought salvation to the Isles in the ocean, and Ventanius, the sixth-century Patriarch of Jerusalem, wrote very definitely and in detail of Paul’s visit to Britain, as did many other chroniclers of early church history.

In his recent, influential ‘biography’ of Paul, the New Testament scholar Tom Wright explained why he is now inclined to give more weight than he once did to the testimony of Clement, Bishop of Rome, quoted above. In referring to the farthest limits of the west, Clement could have been simply extrapolating from Romans 15, and Wright suggests that it would have suited his purpose to give the impression of Paul’s reach across the empire. But he also points out that Clement was a central figure in the Roman Church within a generation of Paul’s day, writing at most thirty years after the apostle’s death. It is far more likely that he had more solid and reliable traditions about Paul than we can invent without first-hand sources other than those in the New Testament. “The farthest reaches of the west” could, of course, have meant Spain, but it could also have meant Britain, especially after the Claudian Conquest of AD 43 and especially by AD 63, when Paul was reported to be visiting the ‘Galatian’ churches along the Aurelian Way.

Even if Paul were killed in AD 64, there were nearly two years, time enough for a visit to Spain, and even to Britain, especially if he followed the route from Marseilles to Brittany and then to Portsmouth. There was also regular traffic between Rome and Tarraco, the Catalan town of Tarragona, the capital of Hispania Tarraconensis, which since the time of Augustus had stretched right across the Iberian Peninsula to the Atlantic coast. Paul may have had an additional motivation for choosing this latter route, as the temple to Augustus had been replaced in Paul’s day with a dramatic complex for the imperial cult. This was clearly visible from several miles out to sea, and Paul may have been eager to announce Jesus as Lord and King in places where Caesar was claiming those titles. If Tarraco was still considered to be in the province at the end of the known world in AD 63, it would have been a natural target by the missionaries.

As Tom Wright has pointed out, all of Paul’s plans carried the word ‘perhaps’ about with them, so perhaps if he did make it to Spain, he could also have gone north-west to the oceanic islands. Wright asks, might we not have had the chance of a Pauline version of Blake’s famous poem, ‘Jerusalem’? It would, of course, have had to refer to ‘Cambria’s mountains green’! It may be that the comparatively easy convergence between Paul’s letters and the narrative of Acts has lulled scholars into thinking that we know more than we do about his last years. The second letter to Timothy implies some additional activity back in the East after an initial hearing in Rome. In his letter, Paul really does believe he is facing death at last:

I am already being poured out as a drink-offering; my departure time has arrived. I have fought the good fight; I have completed the course; I have kept the faith. What do I still have to look for? The crown of righteousness! The Lord, the righteous judge, will give it to me as my reward on that day – and not only to me, but to all who have loved his appearing.

2 Timothy 4: 6-8.

If Paul was back in Rome by the time of Nero’s persecution, facing additional hearings in difficult circumstances, two years would hardly have been enough for journeys both to the west and the east. But by AD 62, the persecution would have negated the need for any hearings or legal trappings. Paul could no longer shelter in house arrest from the terror behind his Roman citizenship. The emperor had laid the blame for the fire on the Christians as a group, and that was enough for Paul to be rounded up with all his fellow believers. Paul may have been away from the city in either the west or east, but returned to Rome in AD 64, to find that the public mood had changed so much that, citizen or not, appealing to Caesar or not, he was now straightforwardly on trial as a dangerous troublemaker. However, rather than the slow, agonising deaths, often following appalling tortures that Nero inflicted on the Jewish-Christian immigrants from the southern ghetto, he was summarily convicted and swiftly executed by beheading, as a citizen, with a sword.

Paul’s world view and theology was strongly motivated by his eschatology, which, as his letter to the Romans (chapter eight) shows, was shared by many of his readers and listeners. This was undoubtedly what added an urgency to his last missions. But the main point about the end of the world was that it could occur at any time, not that it had to occur within a specific time frame. The event that was to occur within a generation was not the end of the world itself, but, according to the Gospel writers, the fall of Jerusalem. By the time of Paul’s death, this was woven into the fabric of the early Christian faith. Jerusalem itself, and the Temple specifically, had always been seen as the place where heaven and earth met. Its destruction in AD70 was therefore a pivotal point in the development of Judeo-Christian thinking and theology.

If Paul had heard of this by living just a few years longer, he might have reflected, theologically, that the One God had already built his new Temple, his new microcosmos; the Jew-plus-Gentile church was the place where the divine spirit was already living in the midst of mankind, revealing his glory as a sign of what would happen one day throughout the whole world. Sooner or later, Paul must have thought, the new movement was bound to thrive. Of course, Paul would not expect all this to happen smoothly, without suffering and struggle. He would not have expected that the small and muddled communities would be transformed into a much larger body, covering the entire known world, without further terrible persecution. The new movement in which he led was not just the accidental by-product of energetic work, a historical opportunity, but the chief product of divine will and purpose. But just as Paul would not want to give a purely naturalistic, demythologised explanation, neither would he wish instead to ascribe the whole series of events to divine or angelic power without human agency.

Probably because the diasporic Jews after the Jewish War of AD 70 were unorganised and not militant, like the British guerrilla warriors, the Roman campaign of extermination against them was not so widespread or determined. They also had a longstanding imperial exemption from making tribute to the emperor, whereas Gentiles had no such exemption. Instead, as in Rome, they were forced into ghettoes throughout the imperial cities where they settled, where their defiance could not easily be observed. The Gauls and the British, however, were warrior nations skilled in the arts of warfare on land and at sea.

The Gauls had been largely subdued, but the British were still led by independent rulers and military commanders, all of whom were steeped in invincibility of spirit, which stemmed from their Christian faith, which decreed that all men should be free. The overwhelming rise of Christianity in the densely populated cities of Gaul and Britain was therefore viewed with consternation by the authorities in Rome. Britain had become the seedbed of missions like the one at Glastonbury, where an ever-flowing stream of preachers was tutored, trained, and ordained by the apostles and disciples, and then sent out as missionaries to distant territories and foreign lands.

The Persecutions of the Early Church:

The Romans declared that this mushrooming of missionary activity had to be stopped. To them, might alone was right, but from their past experience of British military resistance, they had good reason to respect and even fear it, inspired as it was by the zeal of Christ. Yet Rome had conquered the world, or so it claimed. That unity was a top-down uniformity in which diversity was welcomed as long as it didn’t threaten the absolute sovereignty of Caesar. That diversity was always seen in strictly hierarchical terms: men over women, free over slaves, Romans over everybody else. Rebels were to be ruthlessly suppressed, as were the Druids and Cambrian Christians in the Menai bloodbath staged by Suetonius Paulinus, and the Trinovantes in the Boadicean atrocities conducted under the malignant direction of Catus Decianus in AD 60 to 62.

The Pax Britannica, ‘the great peace’ which had descended over the Island, beginning with the Treaty of Agricola in AD 86, continued for a period of two hundred years. During that time, no mention of British-Roman conflict was recorded. Yet, as the Briton Calgacus remarked, they make a wilderness, and call it peace. The Claudian Edict to crush British resistance was founded on the mistaken belief that only violent persecution would terrorise the Britons into ultimate submission. Roman chroniclers were silent, leaping the two-hundred year gap as though nothing of significance had occured in the ‘pacified’ island of Britannia. They took up the record again in the year AD 287, to recite the usurpage of the Emperor’s crown by Carausius, the Admiral of the Roman fleet, who landed in northern Britain, marching to York, where he had himself proclaimed Emperor. Since the fall of London to Queen Boudicca (Boadicea) of the Iceni, the City of York had become a popular resort for the Romans. From the ancient British city, the age-old citadel of the Brigantes, first known as Caer Evroc, several Roman emperors had chosen to rule, deeming it a safer haven for that purpose than Rome. For centuries before them and Christ, it had been the centre of the enamelling craftsmen of the La Téne art.

But we should always listen to the silences in the official records, and by doing so, we discover from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s British sources that it was in AD 156 that, by the royal edict of King Lucius, proclaimed at Winchester, southern Britain became officially Christian for the first time. Carausius reigned as Emperor from York for seven years before his assassination and usurpation by his own minister, Allectus, in AD 294. The usurper reigned for two years before falling in battle against the forces of Constantius Chlorus, who then succeeded him and also ruled the Empire from York for the next ten years. With him began one of the most momentous chapters in early Christian history, beginning first in the city of Colchester, or Camulodunum, once capital of the Iceni under Boudicca, and the royal seat of King Coel, whose castle was at Lexdon, now a suburb of the modern city.

In AD 265, Coel had a daughter named Elén, who later became known as Empress Helen of the Cross. Raised in a Christian household, her natural talents were developed to a higher degree by the best scholars and administrators in the land. While her regal husband and son stood out eminently in the art of diplomacy, her capacity for political administration played a prominent part in their imperial destiny. The Christianising of the Roman Empire would undoubtedly have been delayed centuries but for her energy and devotional support. Roman history merely describes her in her role as Empress. No mention is made of her British ancestry and heritage, including her royal Romano-British predecessors, Princess Eurgain and Claudia Pudens. She was made to appear simply as a native of Rome, wife of a Roman and mother of an illustrious Roman son. Later, however, the Protestant reformer, Philip Melanchthon, sought to set the Roman record straight when he wrote in his Epistola that Helen was unquestionably a British Princess.

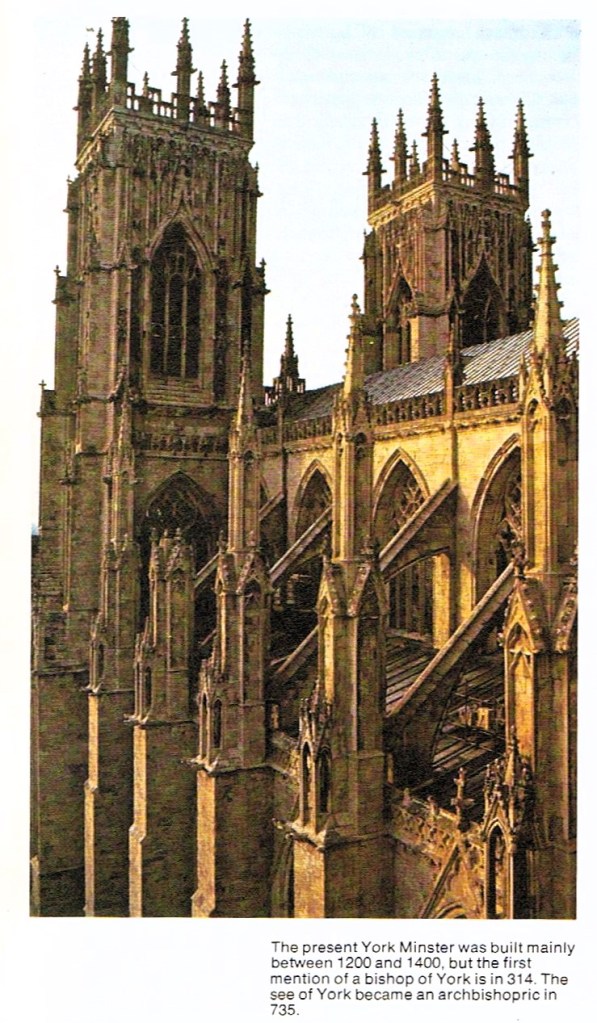

Even before Constantius defeated Allectus at York, he was recognised as Emperor of Britain, Spain and Gaul, the boundaries of which extended far across western and southern Europe, including Germany. He was proclaimed as Emperor of Rome at York and was the first to be recognised as monarch by the people of the four domains. Only he and his extraordinary son, Constantine the Great, were ever to attain imperial rule over the whole of the vast empire at its height. In the pre-Christian era, as Caer Evroc, York was one of the Druidic centres, continuing so at the time of the Josephan Mission until King Lucius established London, York and Caerleon on Usk as the three great Archbishoprics of Britain. Six years before he became Roman Emperor, in AD 290, Constantius renewed and enlarged the Archbishopric of York, making it the most outstanding royal and religious city in Britain. Later, Caerleon was replaced by Canterbury as the third archbishopric, with the latter then replacing London as the chief ecclesiastical seat ahead of York.

Before the ascent of Constantius to the throne of the Roman Empire, revolution and assassination had been disposing of one emperor after another. There was a confusing array of predatory Roman nobles who raised their armies, laying claim to the throne of the Caesars. The notorious Diocletian held the reins in Rome, and on his orders began what is often described as the worst persecution of Christians in the year AD 290. Besides the attacks on people, churches and scriptures, libraries, schools of learning and private homes were destroyed. The lions roared again in the Colosseum, the prisons were filled, and the streets ran with the blood of many martyrs. No Christian was spared, nor were their families, even babes-in-arms. This persecution was described as the tenth since the Claudian Edict of AD 42. Like previous emperors, Diocletian scapegoated the Christians for the series of disasters over the years that had decimated the Roman armies to such an extent that they were no longer able to defend their frontiers successfully, let alone conquer as before. Rome was on the decline, and her glory was fast fading. Diocletian sought to evade national disaster by ordering the extermination of the Christians, their churches, and other possessions.

This bestial cruelty lasted for eighteen years, and it flamed across Europe for several years before it struck Britain. Again, the Romans were frustrated by the incredible zeal of the martyrs who died with prayer on their lips, watching the common people being destroyed, showing the same disdain for death as had their Christian forbears. This infuriated Diocletian, so that he adopted ever more fiendish practices, in which he was later aided by Maximian, who became co-ruler with him over the continental empire. His ferocity and atrocities were claimed to be beyond description; he was blind with maniacal hatred of Christians.

The Diocletan savagery, which began in Britain in about 300 AD, showed how barbaric the imperial extermination of British independence and all that was Christian had become. On the orders of Maximian, co-ruler with Diocletian, the Christian Gaulish veterans, the finest warrior battalions in the Roman army, were slaughtered to a man in cold blood, such was his absolute hatred of Christianity. Meanwhile, the Emperor poured a huge army into Britain. But Constantius Chlorus had already been proclaimed Emperor at York, and the British kingdoms were more united. Previously, they had fought for years in deciding each conflict with the Romans, with victory swinging from one side to the other. Yet, within a year, Constantius had terminated the Diocletian persecution in Britain, driving the Romans back to the continent in AD 302. However, the Romans had succeeded in inflicting huge losses on the British armies, and had levelled churches, universities and libraries, besides sacking towns. The slaughter was terrific, and included a list of British martyrs that far exceeded the total by all the former persecutions combined. This was not so much the total from the field of battle, but in the slaughter of the priesthood and their defenceless flocks.

Following King Lucius’s death and the raising of Asclepiodotus, Duke of Cornwall, to be king, the persecution of the Emperor Diocletian resulted in the near blotting out of official Christianity across the whole island. Maximianus Herculius, chief of the Roman armies in Britain, reconquered the whole country, tore down the churches and burnt all copies of the sacred scriptures that could be found in the marketplaces. Priests were put to death, along with the faithful committed to their charge, …

… and the thronging fellowship of Christians did hasten to vie with one another which should first reach the kingdom of Heaven and delight thereof, as though it had been their abiding place.

Geoffrey’s Histories, p. 79.

Among those men and women martyred was Alban of Verulamium, his confessor and protector, Amphibalus, and Julius and Aaron of the City of Legions, Chester, who were torn limb from limb. The prelates killed included Socrates of York, Stephen of London and his successor, Nicholas of Penrhyn (Glasgow), and Melior of Carlisle. Gildas also estimated that the number of communicants killed was as many as ten thousand.

After Constantius had married Elén, she bore him a son whom she called Constantine. The Emperor and his Queen Empress began to restore the churches destroyed under Diocletian’s Edict. It was a titanic task into which the royal family poured their fortune. During these eleven years of restoration, Constantius died at York in AD 306 and was succeeded as King of Britain by his son, Constantine, with his mother acting as protector. For the next six years, the young Emperor remained in Britain, building many new churches and institutions of learning.

The Constantinian Conquest of Rome:

Having restored peace to his British kingdom, expelling the armies of Diocletian, Constantine prepared to cross the seas to the continent. During this time of the protectorate, Diocletian and Maximianian continued their destruction of Christian lives there. Meanwhile, many Roman refugees, fleeing Maxentius’s tyranny in Rome and other imperial cities across Gaul, began to arrive in York, where Constantine received them with honour. As their numbers grew, they stirred him up into hatred of the tyrant who had deprived them of their homes, estates, and families. They made speeches imploring him to act on their behalf:

“How long, O Constantine, wilt thou endure this our calamity and exile? Wherefore delayest thou to restore us to our native land? Thou art the only one of our blood strong enough to give us back that which we have lost and to drive Maxentius forth. For what prince is there who may be compared unto the King of Britain, whether it be in the valour of his hardy soldiers or the plenty of his gold and silver? We do adjure thee, give us back our possessions, our wives and children, by emprising an expedition to Rome with thine army and ourselves.”

Geoffrey of Monmouth, Histories, V, Chapter VII (1912 edn.)

Geoffrey wrote that, provoked by these words and others, Constantine massed a powerful army in Britain and went via Gaul (southern Germany today) to Rome, taking with him the three uncles of Helena. The two armies clashed on the banks of the Tiber, where the Romano-Britons won an overwhelming victory under his generalship. Maximian was completely routed, and the persecution was brought to an immediate end. After deposing Maximian and becoming emperor, he raised his uncles to the rank of Senators.

Officially acclaimed by the Senate and the citizens of Rome, he also became Emperor of Gaul and Spain by hereditary right. Including Britain, this was the greatest territorial dominion ruled over by one emperor. His first act as Emperor of Rome was to declare it Christian in religion, ending persecution within the Empire (c. 312).

So, just when it seemed as though Christianity on the Continent had been crushed by the Diocletian persecution, it was a Romano-British consul, Constantine, who, with an army of Christian British warriors, crossed the seas and smashed the imperial armies with a defeat so catastrophic that they never rose again. That Western victory ended the persecution of Christianity within the empire. The Roman Empire became nominally tolerant of Christianity under Constantine in c. 350 AD, but it was not until the later seventh century that Papal supremacy was recognised across Western Europe.

On the continent, the Empress Helen is also given credit for the founding of the first cathedral at Tréves (Trier), then the capital of Belgic Gaul. Due to this association, the city had closer contact with the early British monarchs than any other on the continent before the Norman Conquest. The practice of making church dedications to women, other than to Mary, the mother of Jesus, did not begin until the twelfth century. But the church of St Helen was erected to her glory several hundred years before that practice, when she was also proclaimed as a saint. After the death of her husband at York in AD 306, Helen continued to reign as Empress together with her son before she died in AD 336, aged seventy-one, in Constantinople.

Later in the fourth century, the Emperor Maximus Magnus (the legendary ‘Macsen Wledig’ of the Mabinogion, the eleven Old Welsh stories written down in circa 1300-25) overran the continental empire in AD 387 from Galicia with his British army before withdrawing into Gaul, where they settled in Brittany. According to Hewin’s Royal Saints of Britain…

…The Emperor Maximus Magnus or ‘Maxen Wledig’ was a Roman-Spaniard related to the Emperor Theodosius, and of the family of Constantine the Great, and British royal descent on his mother’s side. …

Although Macsen was Spanish-born (in Celtic-speaking Galicia), he served with Theodosius in the British wars and rose to high military command in Britain. In 383, he invaded Gaul to oust Gratian, the Roman emperor of that time, and after Gratian’s assassination and the flight of Valentinian, became master of Italy, but was himself put to death in 388 by Theodosius. The excursion of Elén’s brothers to Rome is historically inaccurate, but the story shows a strong, nostalgic interest in the old Roman grandeur, and the (exaggerated) contribution to it of British fighting men.

The Age of Christian Expansion:

It was not until the beginning of the fifth century that native Christianity in the British Isles, having recovered sufficiently from the Roman persecutions, re-established itself to the extent that the Patriarch of Constantinople was able to remark:

The British Isles have received the virtue of the Word. Churches are there found and altars erected. … Though thou shouldst go to the ocean, to the British Isles, there thou shouldst hear all men everywhere discoursing matters out of Scriptures, with another voice indeed, but not another faith, with a different tongue, but the same judgment.

Chrysostom, Sermo De Utilitate, AD 402.

The renowned Cymric bard, Taliesin, writing in AD 500-540, one of post-Roman Britain’s greatest scholars and an archdruid, declared that though the gospel teaching was new to India and Asia, it had always, from the beginning, been known in Celtic Britain. He wrote:

Christ, the Word from the beginning, was from the first our teacher, and we never lost His teachings. Christianity was a new thing in Asia, but there never was a time when the Druids of Britain did not hold its Doctrines.

As we have seen, Christianity in Britain, in its first three centuries at least, was a flower planted and flourishing in the soil laid by the Druids. This could be seen in both the practice and the basic principles of the new religion. The Druidic economic law of the law of righteousness and distributive justice, based on the practice of tithing. The Druidic natural law was exactly the same as the Judao-Christian law of righteousness, enabling the merging of Druidic and Christian principles of faith. For its first millennium, this practice was so embedded in the minds of the faithful that it was normally carried on throughout the Golden Era of the church in Britain. The magnificent gifts of the British kings to the church were simply an enlargement of the tithe on their part. The Queen Empress Helen and her son, Constantine the Great, were probably the greatest contributors to the Roman-British church. For their subjects, the Harvest Festival or Thanksgiving was the time when they brought their gifts from the field to the church. Following the Golden Era, circa AD 600, the time of the conversions of the Anglo-Saxons, the tithe began to lose some of its original substance, a development which was intensified by the effect of the Viking raids and incursions of the eighth and ninth centuries. In 854, King Aethelwulf issued a Royal Charter which recognised the tithe as a national institution, representing:

“The tenth part of the land of the Kingdom to God’s praise and His eternal welfare.”

The deed was written at Winchester, and the Charter was placed on the Cathedral altar in the presence of Archbishop Swithun and the Witangamot (The Council of Aeldermen), where it was consecrated to the service of Christ. This effectively established the church as the national church of England. The apostolic claim of the Church of Rome is unsupported in historical terms. Peter was never addressed as Bishop of Rome by St Paul, any of the Apostles or the early Bishops of the Church. Neither did he make any claim to the title, that of Archbishop or Pope. Clement was the first to be named as Bishop of Rome. In the British succession, Gregory the Great, who sent Augustine to England, rejected the title of Pope, and it was only ascribed to him posthumously by various church chroniclers. Gregory simply claimed to be ‘first among equals’.

The earthly leader of the Roman Church in the fourth and fifth centuries was known as the Bishop of Rome. It was only in the year AD 610 that the title of Pope, meaning universal pontiff, was created by the Emperor Phocas because the Bishop of Constantinople had excommunicated him for having plotted the execution of his predecessor. Even then, the title was not universally recognised until the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire, under the leadership of the Emperor of Germany, Otto I. Although the bishops of the Kingdom of Northumbria accepted the Roman rites and calendar at the Synod of Whitby in 664, the Kingdom of England did not come into being until the reign of Eadgar in the second half of the tenth century, and the English Church was not fully subject to Rome until the Norman Conquest, a century later.

The Return to Glastonbury: