Episode Six: End of Dynasty – Exit the Cerdicingas, Enter the Angevins:

Scene Sixty-four; October 1173 – The Battle of Fornham, Bury St Edmunds and the Revolt of 1173-74:

By the early 1170s, the king had already decided that, after his death, his dominions should be partitioned between his three eldest sons. Young Henry was to have Anjou, Normandy and England; Richard was to have Aquitaine, and Geoffrey was to have Brittany. However, in April 1173, a revolt began against King Henry’s efforts to find lands for his youngest legitimate son, Prince John. The Revolt occurred as a result, in part at least, of Henry II’s decision to offer three castles to John as part of an inheritance to secure his son’s marriage to the daughter of the Count of Maurienne. This undermined the claim of Henry the Young, the king’s eldest legitimate son, as the three castles chosen were on land that would have formed part of his inheritance. The fallout of this decision led to Henry’s three elder sons, Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey, withdrawing to the court of the French king and raising a rebellion against their father. Louis was Henry the Young’s father-in-law, and he encouraged the rebellion along with other nobles who would profit from a transfer of power to the would-be usurper. The brothers were also aided by their mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II’s estranged wife, who joined the cause along with many others who had been horrified by the King’s possible complicity in the martyrdom of Archbishop Becket in 1170.

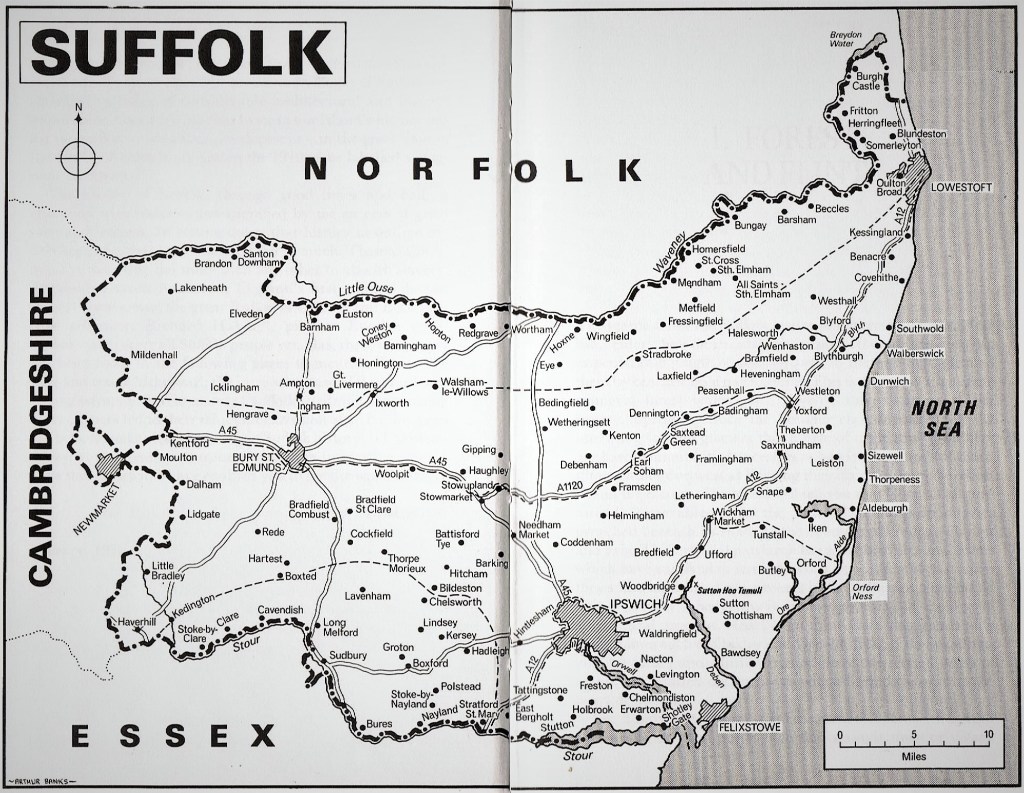

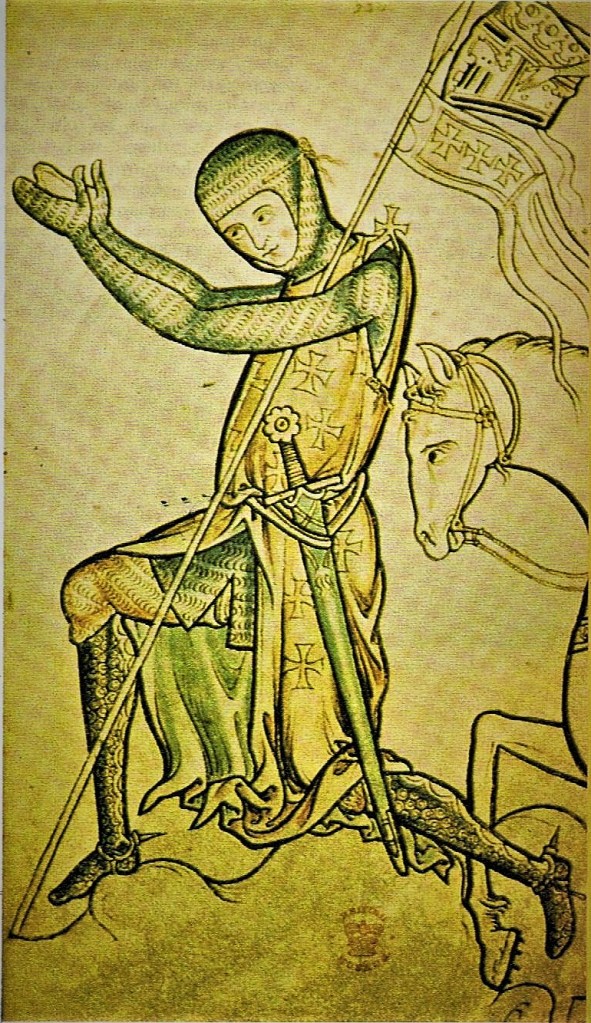

The rebellious sons and King Louis secured several allies and invaded Normandy, and the Scottish king invaded England. The invasions failed, and negotiations between the rebels and King Henry were started, but they did not result in peace until William the Lion agreed to a truce, which enabled Richard de Lucy and Humphrey de Bohun to hurry south to confront the invaders from Flanders. Robert de Beaumont (Blanchmains, ‘Whitehands’), third Earl of Leicester, had raised an army of three thousand Flemings against King Henry in support of his elder sons. After landing at Walton in Suffolk in late September and a failed attack on Dunwich, he marched his troops to Framlingham Castle, where Hugh Bigod welcomed them. After some inconclusive skirmishing, Robert decided to lead his men to his base at Leicester, but was prevented from doing so by royalist forces. His base came under attack from them, and needed reinforcement, but there was also some friction between de Beaumont and Bigod.

Mustering more troops and fortified by the sacking of Haughley Castle, they marched on to Bury. They were met at the village of Fornham All Saints by the King’s forces, soldiers who were bloodied and victorious over the Scots, led by Humphrey de Bohun, Lord High Constable, and Richard de Lucy, the Chief Justiciar. These forces also included three hundred mounted knights led by Roger Bigod, the son of the Earl of Norfolk, who, in opposition to his father, had remained loyal to the king. Along with those knights, the royal forces also had local levies and military retinues of the Earls of Gloucester, Arundel and Cornwall. They were also joined by the knights of the Abbot of Bury St Edmunds.

The battle was fought on 17th October 1173, the rebel forces of three thousand being led by Robert de Beaumont. They were caught fording the River Lark near the three neighbouring villages of Fornham St Genevieve, All Saints and St Martin, four miles north of Bury St Edmunds. The royalist barons intercepted Leicester’s army and brought out their forces in array against his troops. The Abbot’s forces were led by the banner of St Edmund the Martyr, carried by Roger Bigod. The Justiciar’s forces were already outside Bury St Edmunds, preventing Leicester’s further progress into England. The battle was sited in the valley of the River Lark near the church of St Genevieve, on the eastern side of the river. The Rebel Army, leaving Bury St Edmunds behind them, sought a river crossing, a causeway between the Fornham All Saints and Fornham St Genevieve. The King’s troops surprised Whitehands’ mercenaries, forcing them back to Fornham St Genevieve. Leicester, who reported that he could turn neither left nor right,

“saw the armed people approaching them … hauberks and helmets against the sun glinting,”

… and decided to accept battle. Many of the rebel troops were situated on marshy ground near the river, close by the church of St Genevieve. With his forces split, Leicester’s cavalry was captured, and his mercenaries were driven into nearby swamps, where the local peasants killed most of them. The river and the marshy ground accounted for many of the casualties, of whom…

“ …the greater part were killed, a certain number were drowned, a very few were taken away to undergo captivity… The prisoners of distinction were sent to the king in Normandy… but nearly the whole of the foot soldiers were killed, and many of the others were taken prisoner and put to death. … The prisoners of the low valley, King Henry disposed of according to his discretion. Many of the Flemings were killed, and many of the others taken prisoner (were) put to death.”

The battle itself was soon over, resulting in a decisive victory for the royalists. Probably over three thousand rebels were killed either in the battle or in the rout which followed along the banks of the River Lark. Thus, Whitehands’ entire force was either killed or taken prisoner, including Leicester himself and his wife, the Countess Petronilla de Grandmesnil, who had herself put on male armour. She was the great-granddaughter and heiress of Hugh de Grandmesnil, one of the proven companions of William the Conqueror, who fought at the Battle of Hastings. Jordan Fantsome, a chronicler, wrote that she fled the field, only to be found in a ditch. He credited her with dismissive remarks about the English who were fighting for the king:

“The English are great boasters, but poor fighters; they are better at quaffing great tankards and guzzling.”

She accompanied Earl Robert throughout his military campaign against the English troops under the command of the Earl of Arundel and Humphrey III de Bohun. During the final battle, Simon of Odell pulled her out of the ditch, where he claimed she was trying to drown herself, telling her:

“My lady, come away from this place, and abandon your design! War is all a question of losing and winning.”

She was reported as wearing male armour when captured, with a mail hauberk, a sword, and a shield. Earl Robert was also captured, and his holdings were confiscated. Countess Petronilla was released, but Leicester joined the other rebel leaders incarcerated at Falaise in Normandy, where he remained in captivity until 1177, when he was reinstated to his earldom and some of his lands were returned to him. He died in 1190 when returning from the crusades. Petronilla had married him in the mid-1150s and bore at least seven children, one of whom, Amice, was the mother of Simon de Montfort, the fifth Earl of Leicester.

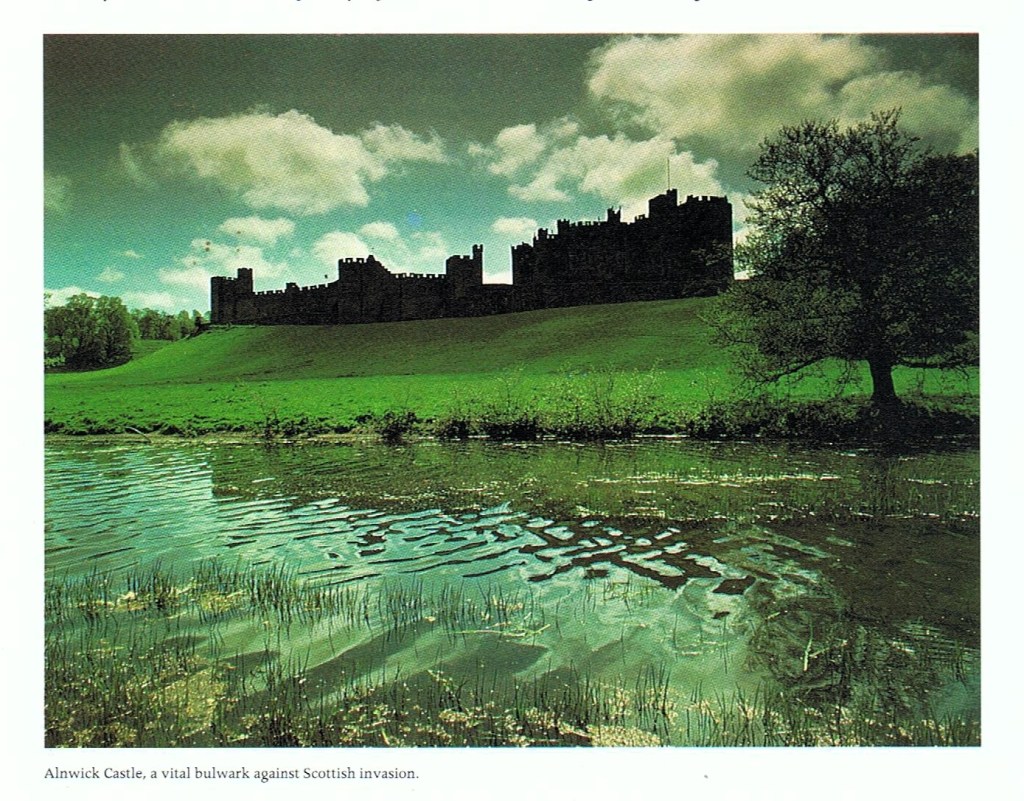

The revolt did not end until 1174 with the capture of the King of Scots, William ‘the Lion’, at Alnwick in Cumbria. Henry II forced William to recognise his overlordship by the Treaty of Falaise (1174), and a century later, Edward I based his claim to interfere in Scottish affairs on this treaty. The Anglo-Scottish treaty was followed by the capitulation of Hugh Bigod and a general surrender at Northampton by the Earl of Derby and the remaining rebels, but the royalist victory at Fornham ended any serious threat to the security and stability of the realm.

Evidence of the Flemings’ brave final stand in St Genevieve’s church was found in the eighteenth century, when the bones of about forty of them were discovered lying head-to-head in a mound near the now ruined church. Its tower is fourteenth century, and so post-dates the battle. Despite many subsequent attempts to drain the land, the northern bank of the river shows extensive ponds and marshy stretches, indicating exactly the difficulties the fleeing Flemings would have faced.

Sixty-five, Canterbury, 1174 – The Advent of Gothic:

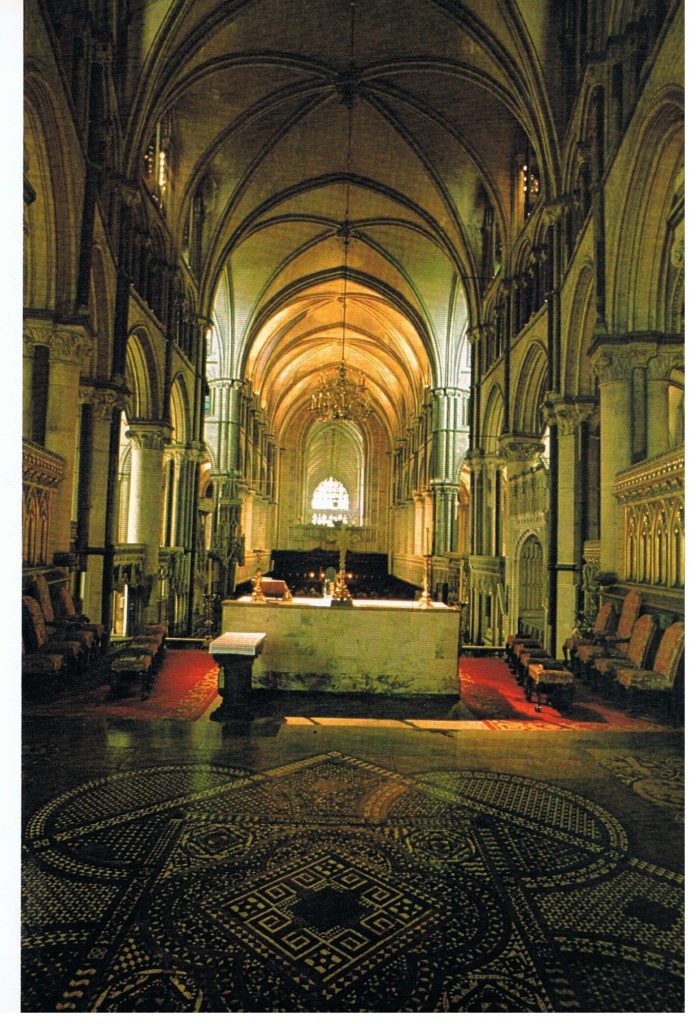

Despite his protestations of innocence concerning Becket’s murder, Henry made public penances. In 1174, he came to Canterbury to show his grief and to be lashed by bishops and monks present at Becket’s tomb. Later the same year, a great fire destroyed the choir of the cathedral, which had been built earlier in the century. The cathedral coffers were full enough from the offerings given to the shrine of St Thomas that the rebuilding of the choir could start almost immediately.

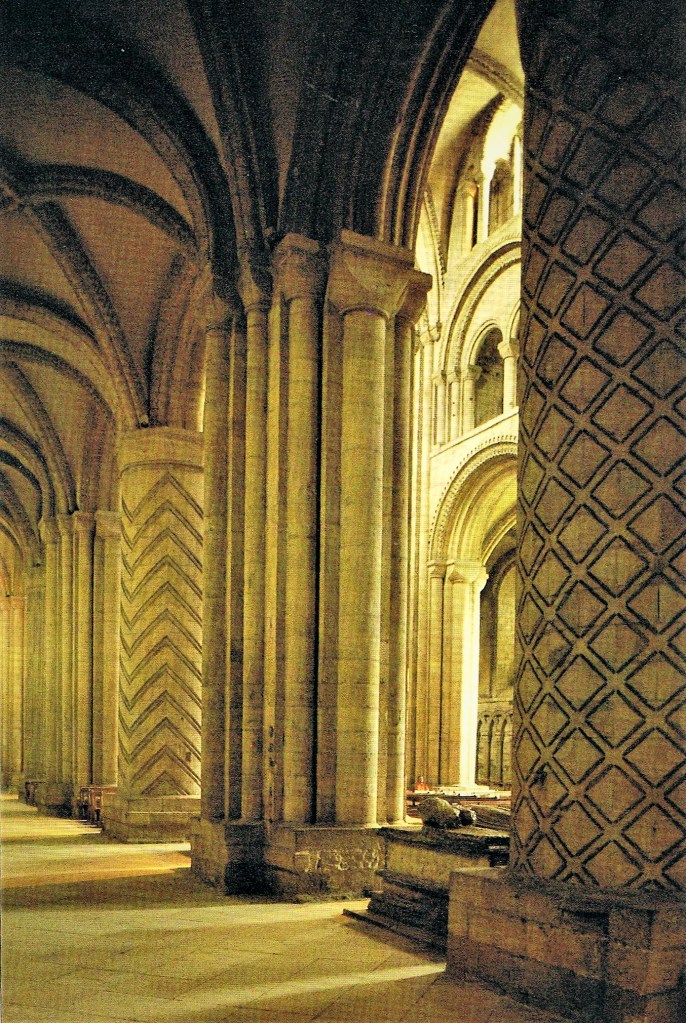

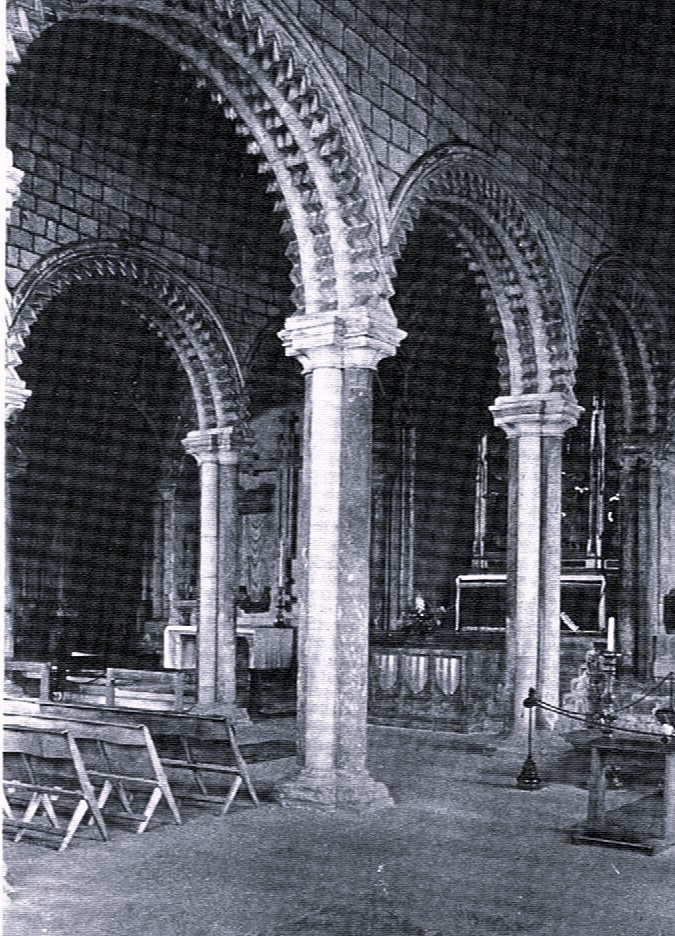

The style of architecture chosen for the new choir at Canterbury, Gothic, was as important for the development of civilisation in Britain as the martyrdom of Becket was in its political and spiritual development. The style had made its first appearance in France at St-Denis, Chartres and Sens, where the first cathedral to be built wholly in the new style was begun in the 1130s. All the constructional elements – the ribbed vault, the pointed arch in the vault and the flying buttress, all of which were necessary for the development of the style, had been brought together in the high vaults in Durham, where the buttresses are nevertheless hidden by the aisle roofs.

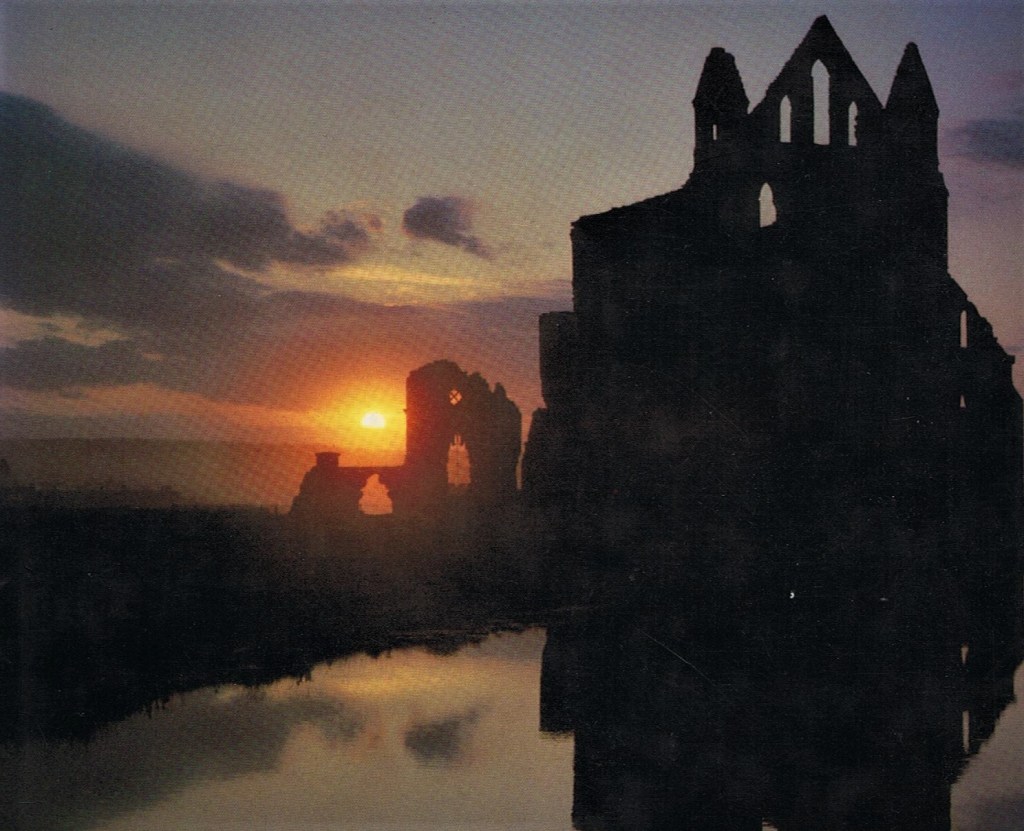

The Cistercians seized on the style for their later churches: For example, Kirkstall outside Leeds, containing many Gothic features from about 1150. The prestige of Canterbury as the primatial see of England and the shrine of a recent martyr ensured that the Gothic would, in the various stages of its development, be the style of church architecture for the next four hundred years in the British Isles, not just for great cathedrals and abbey churches, but also for the humbler parish churches. In the sculpture of the Gothic artists, there seemed to be a new visual presentation of the Christian idea of the worth of the individual soul. Stained-glass windows were made possible by the high vaulting and flying buttresses, employing sunlight and glass to depict Bible stories and the miracles of the saints, including St Thomas in one of the new windows in Canterbury Cathedral.

Scotland’s greatest surviving Gothic building was the cathedral of St Mungo in Glasgow. It was founded by David I in 1136 on the site of a cemetery that two hundred years earlier had been consecrated by St Ninian. The building was destroyed by fire and rebuilt in 1197. At St David’s in Wales, the interior of the nave was built under Bishop Leia between 1180 and 1198, and the building is an anthology of all the styles of all the styles from the Romanesque and Transitional to Tudor. The stone is a violet coloured sandstone quarried locally. Though built after the choir in Canterbury, it is still strongly Romanesque in style, but with pointed arches in the Gothic style. In the Middle Ages, two pilgrimages to St David’s were considered the equal of one to Rome.

Sixty-six: Chinon, July 1189; End of Reign – The Death and Legacy of Henry Plantagenet:

By the time of Becket’s martyrdom, the king had already decided that, after his death, his dominions should be partitioned between his three eldest sons. Young Henry was to have Anjou, Normandy and England; Richard was to have Aquitaine, and Geoffrey was to have Brittany. Later, in 1185, John was granted his father’s other major acquisition, Ireland. The death of young King Henry in 1183 and Geoffrey in 1186 should have eased Henry’s dynastic difficulties, but Richard was alarmed by his father’s obvious favouritism towards John. An alliance between Richard and King Philip II led to Henry’s defeat, and he died at Chinon in July 1189. Although his interest in rational reform has led to him being regarded as the founder of the English common law and a great, creative king, in his own eyes, these were matters of secondary importance. To him, personally, what mattered most were dynastic politics, and he died believing that in this, he had failed despite the successes of the previous thirty years.

But following his act of penance at the cathedral, Henry II ruled England for another fifteen years, long enough to see his embryonic legal system grow into a network of courts. Up and down the land, these new courts were to settle not just the usual disputes of blood and mayhem, but all manner of painful rows over inheritances, estates and property. Most importantly, Henry II revived and reorganised his grandfather’s Curia Regis and developed the justice system by sending itinerant justices around the country. These judges followed the laws which applied to the whole country instead of local customs, and so improved on the old methods of trying a case. They invited witnesses to help settle disputes, and tried criminals presented to them by local groups of men who were responsible for finding offenders. Justice in the King’s Court was better than that of the baron’s court or the shire court; the use of trial by jury was an improvement on the Saxon method of trial by ordeal or the Norman method of trial by battle. By the end of his reign, England was so well organised as a kingdom that even in the absence of Richard I (1189-99) on the Crusades, order was maintained.

The death of young King Henry, officially the next king of England, in 1183, and Geoffrey in 1186, should have eased Henry’s dynastic difficulties, but Richard, Coeur de Lion, the Lionheart, physically brave, chivalrous and brutally ambitious, was alarmed by his father’s obvious favouritism towards John. He was the youngest, vindictive, self-serving, but undoubtedly clever. Henry saw in him the only one capable of governing well. Eleanor pinned her hopes on Richard and encouraged an alliance between Richard and her husband’s bitterest enemy, the French King, Philip II, which led to Henry’s defeat in battle, and he died at Chinon in July 1189. Although Henry’s interest in rational reform has led to him being regarded as the founder of the English common law and a great, creative king, in his own eyes, these were matters of secondary importance. To him, personally, what mattered most were dynastic politics, and he died believing that in this, and through all the quarrels that beset his family, he had ultimately failed despite the successes of the first thirty years of his reign in England.

Henry II was certainly one of the outstanding rulers of the Middle Ages in Europe. He not only possessed vast lands in France, but he also pacified the principalities and marches of Wales, and drove mercenary soldiers from England, as well as pulling down the castles unlawfully built by over-mighty barons in Stephen’s reign. He also became lord of part of Ireland, which, in 1185, he granted to Prince John. He was determined to make the king’s power so strong that the barons could no longer disturb the peace of the land. By his system of scutage, he allowed the barons to give money instead of military service, a plan which enabled the king to hire soldiers on whom he could depend, and at the same time weakened the barons, who no longer trained so many knights. He also reorganised the Saxon fyrds and prevented the barons from becoming sheriffs in the counties in which they held their lands.

Epilogue I – The Green Tree and the Holy Rood:

The Green Tree of Edward the Confessor’s deathbed dream was seen by contemporary chroniclers as a prophetic vision of the kingdom traumatised by the Conquest. Its restoration should have come by the 1170s, but the tree had not been fully restored to its former self and much of it was barely recognisable, for a wholly new stock had been grafted onto the severed trunk. England’s aristocracy, its attitudes and its architecture had all been transformed by the coming of the Normans. The body of the tree, too, had been twisted into new forms. The laws of the kingdom, its language, its customs, and institutions were clearly not the same as they had been before. Even so, anyone looking at these new forms could see in a second that their origins were English. By the 1170s, English had clearly become the language spoken by all classes in England, whatever their ancestry. Intermarriage had blurred the lines of national identity. Yet it was still clear that the unfree peasants were English and that the upper echelons of the aristocracy who still held lands in Normandy were French. But although the English landscape was studded with Norman castles, it was still a land of shires, hundreds, hides, and boroughs. The branches were new, but the roots remained ancient. The tree had survived the trauma by becoming a hybrid. Against all expectations, its sap was once again rising.

When Edward I invaded Scotland in 1297-98, he seized Agatha’s black cross, falsely claiming it as one of the English crown jewels and took it into England. Robert the Bruce so vehemently demanded its restoration that Queen Isabella yielded it up on the pacification during her regency in 1327. The following year, Edward III signed the Treaty of Northampton, recognising Robert Bruce as the King of an independent Scotland. But the symbols of the House of Wessex were to play one further role in the formation of the medieval kingdoms of England and Scotland. David I (1124-53) established Norman barons on both sides of the border and introduced Norman feudal customs to Scotland, besides building abbeys and castles. When the House of Dunkeld died out following the death of Alexander III (1249-86), Edward declared that he had the right to decide on the successor.

Edward ‘Longshanks’ (as he was known to the Scots) chose John Balliol, whom he expected to obey him as if he were an English baron. When Balliol refused this, Edward invaded and defeated him at Dunbar in 1296. He then dethroned Balliol and governed Scotland as if it were a vassal state of England. Under William Wallace, the Scots fought back, taking Stirling Castle in 1297. However, after his victory at Falkirk the following year, Edward seized on Ágota’s black cross, falsely claiming it as one of the English crown jewels, and took it into England. The Scots regained their independence in 1314 following the Battle of Bannockburn, and Robert the Bruce, their new leader, so vehemently demanded the restoration of the Black Cross that Queen Isabella yielded it up on the pacification during her regency in 1327. The following year, Edward III signed the Treaty of Northampton, recognising Robert Bruce as the King of an independent Scotland.

According to Bishop Turgot, drawing on the Bollandists (vol. xxi, p. 335), the seventeenth-century Jesuit order that collected objects and information relating to the lives of the saints, the Black Cross was enclosed in a black case, whence it was called the Black Cross. The cross itself was of gold and set with large diamonds. Aelred of Riveaux described it as about an ell long (= a cubit, the combined length of the forearm from the ‘elbow’ to the middle finger-tip of the extended hand, the Scottish ‘ell’ being 37 ins or 94 cm),

‘… manufactured in pure gold, of most wonderful workmanship, and may be shut and opened like a chest. Inside is seen a portion of our Lord’s Cross (as has often been proved by convincing miracles), having a figure of our Saviour sculptured out of massive ivory, and marvellously adorned with gold. Queen Margaret had brought this with her to Scotland, and handed it down as an heirloom to her sons; and the youngest of them, David, when he became king, built a magnificent church for it near the city, called Holy-Rood.’

All this was the result of David’s continued development of the Norman methods begun by his parents, together with those he had learnt at the court of Henry I of England and Matilda of Scotland. Besides the new monastic foundations, his appointment of Anglo-French bishops further strengthened Scotland’s independent links with the continent. Above all, the Norman military machine of knights and castles, the use of sheriffs and the expansion of trade served as the basis for the expansion of royal power and a strong Scottish economy in the thirteenth century.

In the early modern period, lowland Scots tended to trace the origins of their culture to the marriage of Malcolm II to Margaret of Wessex. David left a Scotland which, though more ethnically diverse than England and Wales, was more united, with a series of able monarchs who continued to improve its administrative and military mechanisms. Following David’s example, they relied on the support of the Church in the formation of states, rather than on ethnic homogeneity. Though the authority of kings over much of their kingdom, especially Galloway, the Highlands and the Isles, was limited, the fertile central belt was under secure control.

Epilogue II: Romancing the British Monarchies – An Empire from the Pennines to the Pyrenees:

The actual empire of Henry I had consisted mainly of England, Normandy, Wales and Brittany. The actual empire of Henry II extended, in a contemporary yet historic phrase, from the Pennines to the Pyrenees. When he came to the throne of England, adding the dominions held by Stephen, Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine, it seemed that the dynastic dream could be accomplished within his reign. The dominant idea of the Plantagenet Henry II’s reign was to gradually extend the frontiers of the Anglo-Cymric-Norman-Breton empire until the descendants of the Conqueror of England would become the emperors of Christendom. It was the lack of cohesion between the various constituent parts of the empire which was the greatest peril to that dream. Lucy Allen Paton wrote in her 1911 introduction to Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Histories of the Kings of Britain,

If only Norman and Englishman, Welshman and Breton, could be induced to work together in the common interest of the Empire, there was no limit to the potentialities of its future greatness. The restoration of an Empire mightier and broader than that of Charlemagne, nay, even that of Augustus, was no impossibility, but a practical aim, towards the attainment of which all the resources known to the statecraft of the time should be directed.

… Geoffrey… was inspired by Henry… Henry, indeed, was no Augustus, and Geoffrey was far enough from being a Virgil, but in this respect the relations between the Roman emperor and the Mantuan poet were strictly analogous to those existing between the Norman king and the Welsh romancer.

To Sebastian Evans, as translator, Geoffrey’s book was an epic that failed, for it was to have been the national epic of an empire that failed. When, in the next generation, King John lost Normandy and most of France in the early years of the thirteenth century, the Angevin empire came to an abrupt end in western Europe. Arthur, the romantic creation of Geoffrey, who was set to have been the traditional hero of the Anglo-Norman-British nucleus of that western empire, became a detached national hero, a purely literary, mythological figure to the early modern British who had forgotten the short-lived empire that had created him.

For Lucy Allen-Paton as well, the Historia is not a chronicle or a history, but a romance based on early British histories, combining his historical, legendary and mythological material with interest and ingenuity. Geoffrey raised a national hero, Arthur of the Britons, already the centre of myth and legend, to the rank of an imperial monarch, substituting for early British stories and customs those of Anglo-Norman England. In doing so, he provided a model of knightly and kingly custom and practice and a dignified place in literature to popular national narrative, determining the form of the romantic chronicle for many centuries to come.

Glastonbury in Somerset had long been associated with the legendary Arthur and Guinevere, and it came to be identified as the Isle of Avalon (Ynys yr Afal in Welsh, ‘the Isle of the Apple’) to which Arthur was borne by three black-robed queens after his last battle with Mordred. This association of Glastonbury with Arthur may have been why Eadmund Ironside was buried there, not at Winchester, in 1016. It later received a great boost in 1191 when a monk of the abbey, inspired by a vision, claimed to have discovered the coffin of the legendary king and queen. The coffin was said to have been inscribed with the words: Here lies the famous King Arthur, buried in the island of Avalon. When it was opened, it was found to contain the skeletons of the royal couple. The blonde tresses of Guinevere’s hair were said to be intact and still shining golden, though they crumbled to dust in the hand of the monk. This was clearly an invented story, not least because Arthur, the Welsh guerilla leader, had not gained widespread fame by the early sixth century, when he was supposed to have lived and died.

Another ‘Arthurian’ site visible from the ‘Tor’ at Glastonbury is the hillfort of South Cadbury, traditionally associated with Arthur’s Camelot. It is an Iron Age fort reoccupied and fortified not only in the Brythonic period but also in later Anglo-Saxon times. The sites associated with the legendary Arthur range from Tintagel in Cornwall, an important Celtic monastery, to Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh. Whatever we may make of such stories and associations, their attractiveness in the late twelfth century is testimony to the continuing popularity of the Arthurian literature and legendarium of the time. They derive from traditions and beliefs going far back into the pre-Christian era, seen through the screen of medieval chivalric society. The Arthur of South Cadbury, who defeated the advancing pagan Saxons at the great battle of Mons Badonicus sometime between 494 and 515, fought somewhere between Bath and Swindon, must, by nature of the topographical and archaeological evidence, have been more parochial and provincial in his outlook. Nevertheless, by the beginning of the Plantagenet period, he would seem to have become a figure symbolising the defence of Christian civilisation and the establishment of kingly rule based on justice and compassion.

Despite these heroic allusions, however, the down-to-earth chronicler William of Newburgh, writing in about 1200, after the king died in 1189, noted of Henry II that he was unpopular with almost all men in his days. This may have had something to do with his infamous early conflict with the Church, but it may also have been because, although he was king for thirty-four years, he was also Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou; he therefore spent only thirteen of them in England. He held more lands in France than its king, while England’s wealth enabled him to outshine the German emperor. Through marriage, inheritance, diplomacy, and occasionally war, Henry II built up a huge domain, and he extended his sovereignty to Scotland and Ireland, as well as to much of Wales.

His marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine brought him control over most of southwest France. Combined with the Norman and Angevin inheritance, this made him the most powerful ruler in France, more so than his suzerain (feudal lord) for these French territories, Louis VII, king of France. In Britain, the Scottish frontier was settled in 1157, making Cumbria and Northumbria definitively part of England. Besides campaigning actively in Wales, making the whole of it a vassal state, Henry intervened in Ireland in 1171. Following a papal bull of 1155 from the English pope, Adrian IV, he established the new lordship of Ireland, based on Dublin, creating a large royal demesne for himself, which became known as ‘the Pale’. From this, he bound the Anglo-Norman barons and most of the native Irish kings to him.

Henry spent twenty-one years on the continent. For both him and Eleanor, England was a social and cultural backwater compared with the French parts of the Angevin dominion. The prosperous communities in the valleys of the Seine, Loire and Garonne river systems were centres of learning, art, architecture, poetry and music. Aquitaine and Anjou produced two essential commodities of medieval commerce: wine and salt. These could be exchanged for English cloth, and this trade must have brought great profit to Henry as the prince who ruled over both producers and consumers of these products. As duke of Normandy, duke of Aquitaine, and count of Anjou, Henry had inherited the claims of his predecessors to lordship over neighbouring territories. These claims led to the occupation of Brittany after 1166 and the installation of his son Geoffrey as duke. However, he failed to give his short-lived empire any institutional unity. It therefore collapsed under his sons, Richard and John. At the time of his death, in 1216, John had lost all of the Angevin lands on the continent except Gascony.

The population of north-western Europe had expanded to a point unsurpassed since the Celtic migrations of the fourth century BCE. The revival and spread of the Arthurian legends in the eleventh century, when legends, myths, and symbols from the Celtic and Romano-British past were revived and transfigured in the Renaissance of the ancient Bear God as Arthur, the Godly Christian prince, led to a growth in the self-confidence of Plantagenet England and Wales. The entire iconography of the House of Wessex, from the story of Offa’s bloodied sword to Agatha’s black cross and Edward’s Green Tree, is a forgotten thread, not just of a romantic royal chronicle, but of the British national narrative.

Appendix – The Gesta Hungarorum and Central Europe in the Twelfth Century:

Across Europe, in the birthplace of the children of the House of Wessex, Hungary, the memory of the English exiles and their influence at court had faded by the mid-twelfth century, in the wake of the Crusades and the movement of the Germans, Rus and other Slavs to the East. The marauding raids of the Hungarians had ended more than a century before. But continual internal instability increased the danger of Pecheneg invasions, and the Hungarians had changed from thieves into gendarmes. Géza I (1074-77) finally reconciled the parties by accepting the Pechenegs into the country, boosting his military power against the ousted but still unsubdued former King Solomon.

The use of written documents spread in governance and administration as slowly as in ordinary legal affairs. Verbal agreements witnessed and administered by the bailiff in common lawsuits or contracts, and political decisions sanctioned by the memory of courtly memory alone, rather than by officially sealed documents, survived well into the twelfth century. A few official documents were irregularly issued by the priests of the court chapel until, in 1181, King Béla III emphasised the indispensable use of writing, leading to the rise of the chancellery. Following this example, from about 1200 private individuals soon began to have their transactions, agreements recorded at the ‘place of authentication’ – hiteleshely – an office with notarial functions, usually at chapter houses or abbeys.

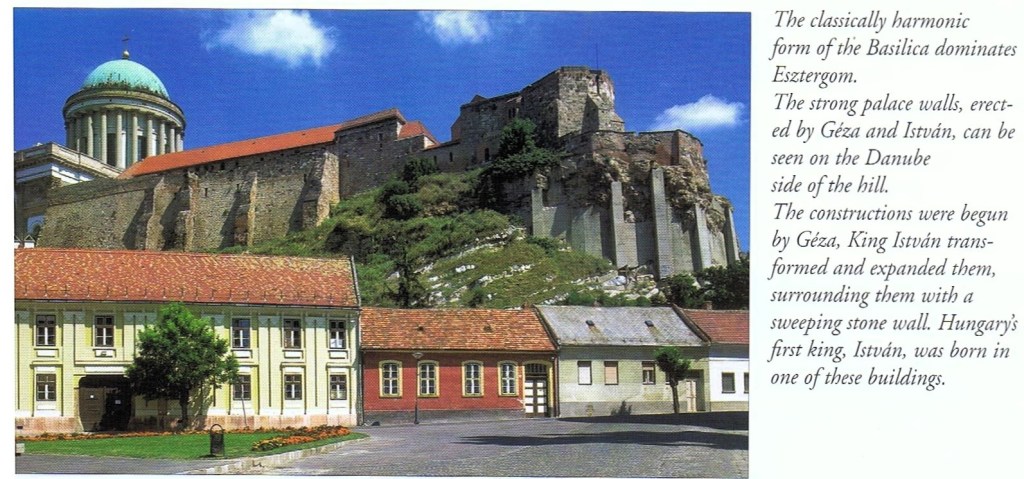

This change in the political and legal culture would have been inconceivable without increasing familiarity with Western learning through diplomatic and commercial ties, in addition to academic links. Luke, Archbishop of Esztergom after 1158, attended the studium generále in Paris as early as 1150. The rediscovery of Roman law in the twelfth century in Europe not only supplied a framework in which the complex realities of vassalage, the manorial system or urban liberties could be lucidly expressed, but also facilitated the modernisation of primitive early medieval monarchies by re-introducing abstract notions of state and subject, and of mutual rights and obligations between them.

Many of these notions appeared in some shape or form in contemporary Hungary, but there were fundamental differences in how they arose in Western Europe and Hungary. In the West, from Germany to Britain, these resulted from successive stages in a more or less organic development that lasted several centuries. In Hungary, these structures resulted to a large degree from an organised response to historical challenges; initially from legislative and political action which, due to the powerful monarchs of the House of Árpád, especially István, Ladislas I and Coloman, compelled a semi-nomadic society to observe property relations and Christian values.

In the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, the fundamental class distinction in Hungarian society was still not that between the titled nobleman and the peasant serf, but between the freeman (‘liber’) and the ‘servant’ (‘szervus’). Neither of these had a legally defined, hereditary status. The ruling class was undoubtedly the aristocracy of ‘the great’ (maiores), the king’s retinue who comprised his council or ‘senate’ and were of very varied origins. Descendants of Stephen’s conforming chieftains, as well as those of foreign courtiers arriving with the rulers’ consorts – Bavarians under István, Kyívans under András, Poles under Béla, Swabians under Ladislas, Sicilian Normans under Coloman – all belonged to this most prestigious, but still non-hereditary caste. Beneath them were the jobbágy warriors of the king’s court and castles, his retinue of ecclesiastical and secular lords, and the civil ministers. However, while these strata were liber in an economic sense, their freedom of movement was restricted; the requirement of loyalty bound them to the estate of their overlord. The peasant cultivators were relegated to a servile status, though their obligations varied greatly between locations and estates of differing types (ecclesiastical, secular and royal).

In 1083, Ladislas began a campaign of canonisation, having several Polish and Hungarian divines elevated to sainthood, including Bishop Gerald (Gellért), who was martyred during the pagan uprising of 1046, and King István (Stephen) I. In this way, he also certified Hungary’s integral presence as a European Christian nation, issuing a warning to the remaining followers of pagan rites. He later gained for himself the glory he obtained for others, though he did little deserving of it. His daughter, Piroska (Irene), also became a saint of the Eastern Church. But the tenacity of pagan traditions remained firm throughout the Middle Ages and even into modern times. Making room for several waves of Pechenegs and Cumans meant that, although the pagan population underwent baptism, it did not become truly Christian for many generations. Ladislas I’s successor was his nephew, Coloman Beauclerc, whose first wife was a Sicilian Norman princess. In the first year of his reign, 1096, the challenges of the Crusaders’ armies reached Hungary one after the other, and were either defeated or sent on their way. The ten-year reign of Béla II (1131-1141) was threatened from Poland by a pretender to the Hungarian throne, Boris, who was thought to be the illegitimate son of Coloman’s second wife, Euphemia, from the new Rus principality of Suzdal.

The eighteen-year reign of Ladislas I began in 1077 after Solomon fled to a group who had taken the place of the Pechenegs, the Cumans, and perished in one of their incursory campaigns. For Ladislas, the Germans formed a more immediate threat than Rome; for this reason, he sided with the pope, although he did not submit to the feudal authority of the papacy in place of that of the Emperor, Henry IV, the brother-in-law of Solomon. The laws of Ladislas attest to both the continuity and change in Hungarian society. The legal system that evolved was very different from that of the Conquest period, based on entirely different views of private property and the value of life. The Conquerors were probably more steadfast in their morality in the ninth and tenth centuries than their eleventh-century descendants, based on the completely different values and customs they had brought with them from the steppes. The relationship between slaves and freemen in the early Middle Ages in Hungary was different among the semi-nomadic peoples of the steppes from that in post-imperial Rome. Similarly, when the feudal system appeared and gathered strength in Hungary, through the laws of Ladislas and his successors, the kind of feudalism that came into being was not the same as that established in Western Europe, nor was it like that which became institutionalised in the east.

Throughout the period as a whole, German peasant settlement expanded eastward, especially in Saxony and Brandenburg, putting pressure on the Slavic peoples. The centre of Rus activity continued to move towards the forest belt. A new principality, Suzdal, developed in this area, while further east, in 1126, Novgorod became a republic and soon extended its territory to the White Sea. In 1169, Kyív was sacked by Suzdal and the title of Grand Prince was transferred to its ruler, the Grand Prince of Vladimir, Suzdal’s capital.

Across Europe and the Near East, the Crusades demonstrated that Christendom could take the initiative: they were as important for relations with Eastern Europe, especially Byzantium, as for those with the Islamic world. Crusading activity played a crucial role at the margins of Europe, and activity against pagan peoples in the Baltic was seen in the context of Crusading. In 1147, the Wends, a Slavic people in north-west Germany, were attacked by the Danes, Saxons and Poles. But these campaigns were as much spurred on by demographic pressures as by religious zeal. In 1144, most of the County of Edessa, captured by the crusaders in 1098, was lost to the Turks. This inspired the Second Crusade, but that led only to an unsuccessful attack on Damascus in 1148. Then, in 1187, Jerusalem and most of the Crusading states were lost by the Christians after Saladin’s crushing victory at Hattin. The Crusades also inspired a novel form of monastic organisation that had political overtones: the Military Orders. The Templars and Hospitallers had troops and castles and were entrusted with defending large tracts of territory across Palestine.

The Gesta Hungarorum (c.1210) was a chivalric romance of the Magyar conquest of the Carpathian Basin in which the adoption of Christianity was an undercurrent comparable to the knightly exploits of the chiefs from whom the contemporary noble houses were supposed to have descended. Of the orders of knighthood, the Hospitallers and the Knights Templar appeared in Hungary before the mid-twelfth century, while the Teutonic Order was invited by Andrew II in 1211 for purposes of defence and to convert the pagan Cumans. Despite the chivalric awakening, the outlook of literature and culture in general was predominantly ecclesiastic. Codices recording legends of saints, rites and monastery annuals of Benedictine abbeys constitute the bulk of this heritage. Besides the Benedictines, the representatives of the reform movement within traditional monasticism, the Cistercians and the Premonstratensians, first arrived in Hungary in the 1140s. Education was a monopoly of the Church. There were no seats of higher learning in the country, and even secondary education was only available in schools maintained by the more important chapter houses and monasteries. It was only at the most prestigious school in Veszprém that law was taught beside the liberal arts.

King Coloman’s son, the restless István II (1116-1131), fought a war in almost every year of his fifteen-year reign. During that time, Dalmatia was lost to Venice, then recovered and lost again; unsuccessful wars against neighbours, including Bohemia, Russia and Byzantium made a group of barons attempt to depose him, which he survived, but leaving no heir, he was succeeded by the blinded son of Prince Álmos, Béla II (1131-1141). The chief events of this reign were the ruthless showdown with those held responsible for his and his father’s suffering, and the defeat of the pretender Boris, who was the son of Coloman’s Russian wife expelled because of adultery, and invited to the country by the remnants of the opposition to Béla’s rule. Géza II (1141-62) was certainly powerful enough to afford, in the early 1150s, the pursuit of an aggressive foreign policy and waging a two-front war against Byzantium and Russia, while also being on hostile terms with the Holy Roman Empire. The reign of Géza’s son, Stephen III (1162-72) was a decade of conflict over the succession between him and his uncles, also crowned as Ladislas II (1162-63) and Stephen IV (1163-65) and, after both of them died, against Manuel, who had supported them. In 1169, however, Manuel’s son was born, and he supported the Hungarian prince in obtaining the throne of the country when it became vacant in 1172.

King Béla III (1172-96) overcame the resistance of the Church, whose head, Archbishop Luke, a Hungarian counterpart of Thomas Becket, took a strongly papalist stance in the renewed debate between secular and spiritual power. The Archbishop was also afraid of an Orthodox influence upon the accession of a prince brought up in Byzantium. Béla ruled over the Kingdom of Hungary at the height of its power during the Árpád period. Nevertheless, the Church jealously preserved a considerable degree of autonomy, to the extent that it became one of the chief vehicles of the development towards a system of estates.

But chroniclers were not only concerned with great powers and principalities, but also with the life history of peoples. It was hardly coincidental, though, that the youngest nation in Europe came into being and survived under Árpád’s descendants. A sweeping economic and social transformation took place in Hungary, resulting in part from the conscious intervention of the rulers and their councillors, and partly from the automatism of accommodation within Europe. With the new circumstances of ownership, rank and social strata following the disintegration of the system based on joint families and clans, the new leading classes, the ispáns and other officials, were soon dissatisfied with the privileges. Instead, because the separate and private possession of land was so important to royal supremacy, they also aimed at acquiring landed estates that would be under their permanent control. At the same time, the Hungarian serfs were still a privileged group compared to the servant class; they inherited much from the position they enjoyed as auxiliary troops in the age of the Conquest. During domestic conflicts, they supported an independent kingship, opposing foreign feudal dependency and the foreign knights on whom the claimants to the throne relied.

For a long time, the larger animals – horses and cattle – served as the most valuable resource and even as a standard of wealth among Hungarians. The minting of the coinage, which began by István I’s reign, transformed the economy and gave new impetus to the extraction of precious metals, and the role of various monopolies became stronger; commerce in salt and horses, mining, the ownership of customs stations, and income from fish ponds. The two major cities, Esztergom and Székesfehérvár, developed significantly, though the royal court itself continued to travel not just between the two capitals, but also from place to place to consume produce gathered in at some of the larger market towns. The export of horses was the sole state monopoly as regards agricultural products. The horse was also an important weapon of war at this time, and the subject of cattle export can also be found in the laws.

By the mid-twelfth century, the development of one basis for the envied wealth of medieval Hungary had begun in Transylvania and Upper Hungary: the extensive and highly profitable panning and mining of gold, silver and copper was continually re-regulated as to ownership and economic rights. At times, the nearly monopolistic position in the production and export of copper brought about enormous economic advantages for the nation, the king and the producers themselves, who were in a privileged position. It was not only the domestic growth that increased the size of the population, but also the settlers of varying ranks and orders streaming into Hungary from every direction to take advantage of its relative safety and even-handed treatment. For example, there was a large Ishmaelite Muslim population, who were able to practice their religion in comparative freedom and were obligated to serve the king only in case of war and only then against a non-Mohammedan enemy. Though often at war over Dalmatia, Venice and Hungary concluded an agreement allowing the free movement of merchants between them, and within Hungary, only the king dared collect taxes, arousing admiration from other European rulers.

The growth of urban communities with self-government in Hungary was largely a matter of the second half of the second half of the thirteenth century. Before 1150, it was only a few French and Walloon communities, and after that date, Flemish and Saxon settlers or hospites (guests) who moved into the cities of Székesfehérvár and Esztergom, or established their own towns that were endowed with privileges, thus becoming liberae villae, constituting the first type of western-style urban development. The Romanians were employed as frontier guards by the Hungarian kings and contributed to the increasingly multi-cultural nature of the kingdom.

Hungarian society at this time, amorphous and ethnically mixed as it was, seems to have lived in relatively prosperous conditions, according to the contemporaneous accounts of foreign authors. Otto, Bishop of Freising, and Abu-Hamid, a Muslim traveller from Grenada, visited the country around 1150, and in roughly the same period, the court geographer of King Roger II of Sicily also reported on it in his well-known description of the world, drawing on the first-hand reports of Italian merchants. Whether sympathetic or hostile towards the land and its people, it is described by all of them as one of plenty and prosperity with cheap corn, rich gold mines, busy fairs and affluent inhabitants.

While it was an exaggerated and stereotypical image, it may not have been entirely separated from reality. Then, as later, the country suffered relatively little from famine, which regularly afflicted the populations of Western Europe. Besides having a comparatively sparse population and abundant natural resources, the Hungarians’ far greater reliance on stockbreeding and fishing meant that they were also far less dependent on the vicissitudes of the weather and the cultivation of crops. In the eleventh and early twelfth centuries, the traditional distinction between freedom and serfdom depended on birth, but by the mid-century, status in the emerging manorial system became the decisive criterion, without the relations that arose within this new framework being consolidated into hereditary terms. In both temporal and spatial contexts, this was a transitory stage, to which the ambivalent nature of political institutions corresponded.

In the six decades following the reign of Béla the Blind, certain motifs returned: disputes around the throne, military campaigns with mixed success, and crusaders marching across the land. But on balance, there was much to be positive about in the reign of Béla III. His first wife was Anne de Chátillon (of Antioch), who, though of French descent, actually arrived at court via Byzantium. His second was Margaret Capet of the Capetian monarchy in France. These two women introduced the French style at the court, where Frederick Barbarossa was received in a manner worthy of his rank. With the king as their example, the barons increasingly followed the fashion trends of Western Europe, which to no small extent contributed to Hungary’s participation in world commerce.

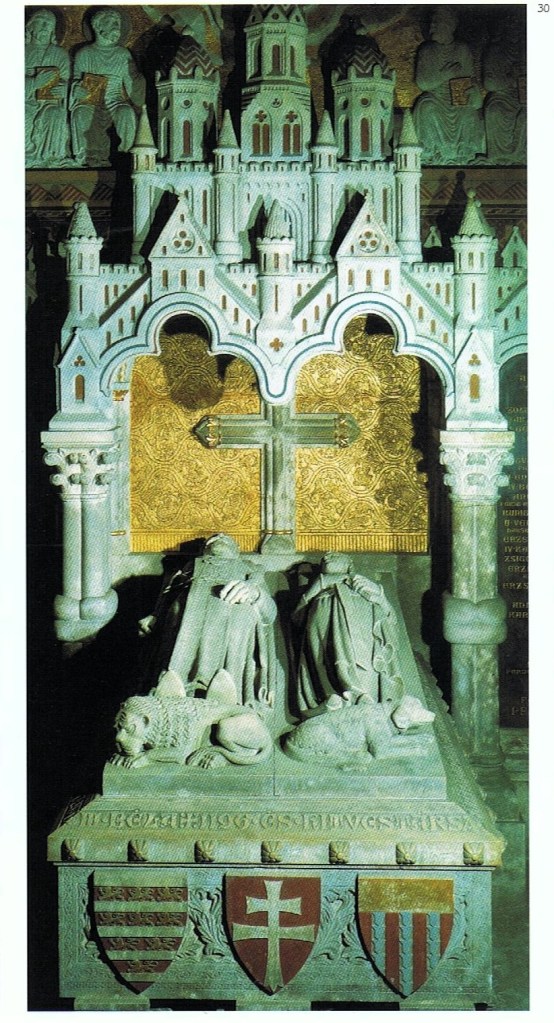

Although of French descent, Béla brought Anne with him from Byzantium. They shared a tomb in Székesfehérvár, but the royal tombs there were ransacked, and most were destroyed beyond recognition. However, the well-preserved remains of Béla and Anne were moved to Buda in 1848.

The majority of landed property in the Kingdom of Hungary throughout the twelfth century remained in the possession of the king, whose authority was still preponderant. According to the testimony of a Paris manuscript of around 1185, the king’s revenues from the monopolies on precious metals, on the minting of coinage and salt, from customs on fairs and river tolls, and taxes from the counties, equalled and perhaps surpassed those in France and England. The patrimonial basis of the Western countries’ economic power was far from that of the King of Hungary. When considered in isolation, the Paris document indicates the efficient functioning of the system of royal counties, the chief units of administration of levying taxes and of raising troops in the country. The military force from the countries alone might have amounted to thirty thousand.

Major decisions were made by the king upon consultation with the royal council, consisting of prelates, court office holders and the ispans of the counties, a body of considerable and indefinite size, which, however, hardly ever convened in full number because of the constant movement of the royal household from manor to manor. Increasing familiarity with Western learning through diplomatic, commercial, and academic ties gradually spread to governance, legal affairs, and administration. Luke, Archbishop of Esztergom after 1158, attended the stadium generale in Paris as early as 1150. In 1177, the Abbot of St Genevieve there reported to Béla III the death of a Hungarian student called Bethlehem, who studied at the university there in the company of three of his countrymen. We also know of a Nicholas of Hungary, a student at Oxford in the early 1190s; together with many other clerics who studied in Paris, Padova and Bologna, which were also popular among Hungarian students into the early modern period. These clerics, as well as the knights arriving in the retinues of queens from western dynasties, were also instrumental in introducing courtly and chivalric culture in Hungary.

The Provencále troubadour Peire Vidal and the German Tannhauser were welcomed at the court of King Imre. The virtues of the knights of the Holy Grail, the valour of the Nibelungs, the blending of gallantry and devotion displayed by troubadours thus became models for young Hungarian nobles, and some of them adopted celebrated the names of Frankish heroes such as Roland and Oliver as well as Alexander or Philip of Macedon who also became idolised in the chivalric ethos.

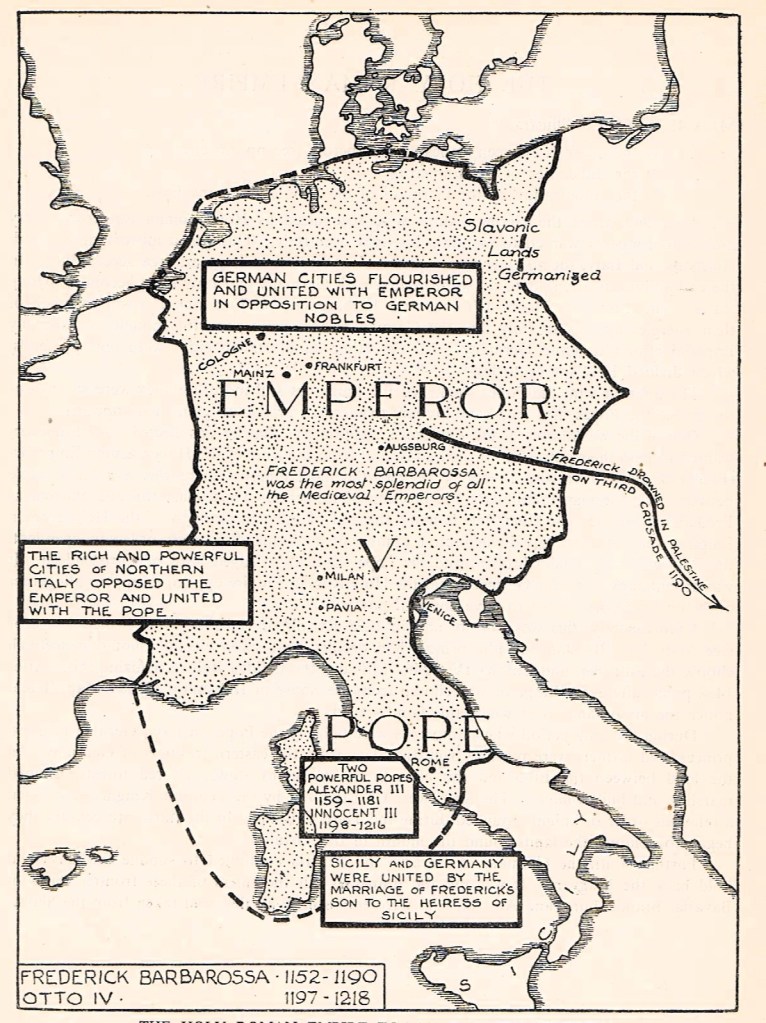

Against this background of the social and cultural conditions of Hungary in the twelfth century, the political situation in the country began to change dramatically by the end of the century. The system created by István I was gradually replaced by an era in which periods of powerful central government alternated with those of unstable royal authority, caused either by continuing dynastic conflict over succession or by internecine aristocratic strife. In the early decades of the twelfth century, the country faced Byzantine or German interference in its affairs because of conflict within the House of Árpád, which supplied the pretext and opportunity for two great emperors, Manuel Komnenos and Frederick Barbarossa, to attempt to bring the nascent country within their spheres of influence.

The growth in the power of Hungary was the most important development to the north of the Byzantine Empire in the twelfth century. After having fended off the attempts of Emperor Manuel I to conquer the Kingdom, Hungary counter-attacked following his death in 1180. The Hungarians gained not only southern Croatia and Bosnia but also seized a frontier zone in the vicinity of Belgrade. This consolidation during Béla’s reign was largely due to the increase of royal revenues and the growth of the chancellery. Also, the rise of the chivalric culture in this time in Hungary certainly owed a great deal to the way that the knightly code of honour was adopted from the West in the court of the innovative Manuel where Béla had been educated, and that his second wife was the French Princess Margaret, daughter of King Louis VII.

Béla’s Hungarian knights recovered Dalmatia and Syrmia from Byzantium and the fact that he assumed the role of mediator in the conflict between the German and Byzantine emperors occasioned by the march of the crusaders of Frederick Barbarossa across the East Roman Empire in 1190, together with the dynastic links established with Byzantium, France, Germany and Aragon during his reign, demonstrate the international importance of Hungary at the end of the twelfth century. The late twelfth century was also a period of fermentation in architectural styles, based on the late eleventh-century high Romanesque of Lombard extraction. The most splendid accomplishments of this in Hungary were the Cathedral of Pécs and the Basilica of Székesfehérvár. In 1190, French master builders arrived in Esztergom and launched the first Gothic workshop in Central Europe.

Conclusion: The Westernisation of Hungary

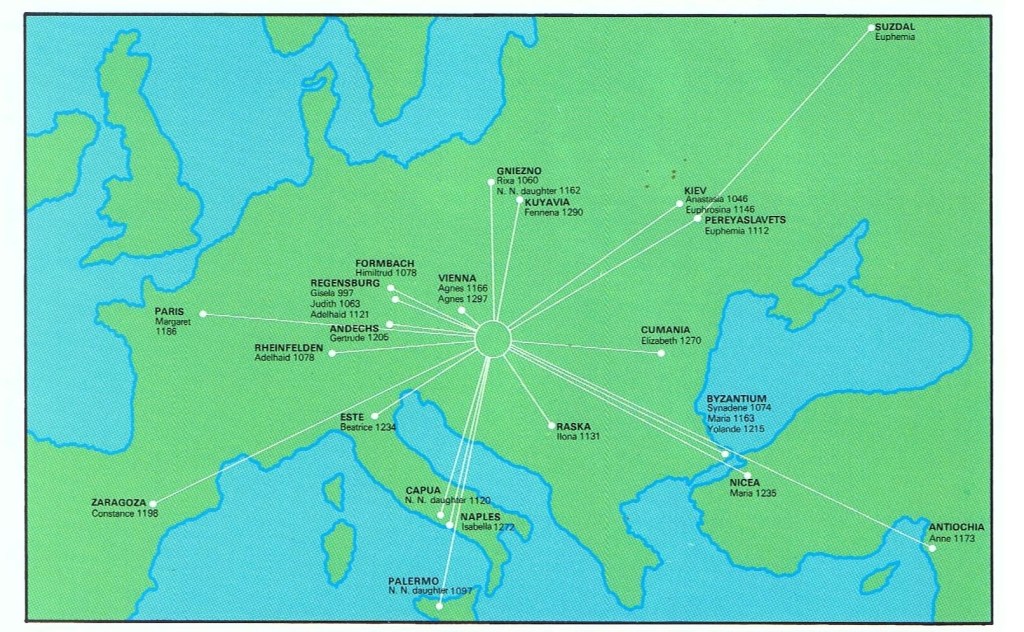

During the time of its earliest kings, the Europeanisation of the House of Árpád, Eastern in its origin, was, in addition to its adoption of occidental Roman Christianity, represented by the invitation extended to illustrious foreigners and their acceptance into the royal court. In the eleventh century, this was best exemplified by the presence of the exiled royal family of the ancient line of Cerdicingas from Wessex. In the twelfth century, the later members of the House of Árpád increasingly mingled their bloodline through inter-dynastic marriages, and also took over many customs and ways of thought prevailing at the courts of the ruling houses of Western Europe.

The map above shows the places of origin of Hungarian queens in the period of the Árpád Dynasty.

(After Alán Kralovánszky).

Thus, the concepts and material accessories of the Age of Chivalry appeared, mirroring Western Europe, at the Hungarian courts. Though posterity called (Saint) Ladislas the chivalric king, that process began earlier and lasted at least until the Angevin period of the fourteenth century. The advent of the House of Anjou to Hungary represented a further stage in the Hungarians’ incorporation into Europe. European influence grew so much stronger in Hungary that the spirit of the chivalric age flowed into it. In exchange, Hungarian influence extended to every point of the compass, including the furthest reaches of the West, in the successive centuries of the High Middle Ages.

Published Primary/ Main Secondary Sources:

Sándor Fest (Czigány & Korompay, eds., 2000), Skóciai Szent Margittól a Walesi Bárdokig: Anglo-Hungarian Historical and Literary Contacts. Budapest: Universitas Kiado.

Christian Raffensperger, Ties of Kinship: Genealogy and Dynastic Marriage in Kyivan Rus. (Harvard Series in Ukrainian Studies.) Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press for the Ukrainian Research Institute, 2016.

Christian Raffensperger, Conflict, Bargaining, and Kinship Networks in Medieval Eastern Europe. (Byzantium: A European Empire and Its Legacy 2.) New York and London: Lexington Books, 2018.

András Bereznay, et. al. (2003), The Times History of Europe: Three Thousand Years of History in Maps. London, Times Books: (Harper Collins).

Simon Keyes, Seán Duffy, and Andrew Jotischky (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British and Irish History. London, Penguin Books.

István Bart (1999), Hungary and the Hungarians: The Keywords. Budapest: Corvina Books.

David Smurthwaite (1984), The Ordnance Survey Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain. Exeter, Webb and Bower.

Peter Rex (2013), Hereward. Stroud, Glos; Amberley Books.

Charles Hopkinson, Martin Speight (2002, 2009), The Mortimers, Lords of the March. Herefordshire: Logaston Press.

István Lázár (1989), An Illustrated History of Hungary. Budapest, Corvina Books.

László Kontler (2009), A History of Hungary. Budapest, Atlantisz Publishing House.

Tom Holland (2009), Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom. London: Abacus Books.

Simon Schama (2003), A History of Britain, Series One. London: BBC.

William Anderson (1983), Holy Places of the British Isles. A guide to the legendary and sacred sites. London: Ebury Press.