Episode Five – The King’s Peace and Justice; 1153-93:

When Henry Plantagenet returned to England again at the start of 1153, bringing only a small army of mercenaries financed with borrowed money, he relied on the forces of Hugh Bigod and Ranulf of Chester. The churchmen who met him on the Hampshire coast also emphasised that while they supported Stephen as king, they sought a negotiated peace.

Henry besieged Stephen’s castle at Malmesbury and successfully evaded his larger army along the River Avon, preventing him from forcing a decisive battle. In the face of the increasingly wintry weather, the two men agreed to a temporary truce, leaving Henry to travel north through the Midlands, where the Earl of Leicester announced his support for his cause. Stephen amassed troops over the following summer to renew the siege of Wallingford Castle, which controlled the important crossing over the upper Thames, in a final attempt to take the stronghold. The two armies confronted each other across the Thames in July. By this point, the barons on both sides were eager to avoid open battle, so members of the clergy brokered a peace, to the annoyance of both Stephen and Henry.

Now there was only Prince Eustace between Stephen and Henry in the succession to the throne. On 18th August 1153, Eustace died, and Stephen was persuaded to adopt Henry as his son and heir to the crown of England. On 7th November, the two leaders ratified the terms of a permanent peace and Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester in the cathedral. Stephen recognised Henry as his adopted son and heir, in return for Henry paying homage to him; Stephen promised to listen to Henry’s advice but retained all his royal powers. Henry and Stephen sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace in the cathedral.

In 1154, Stephen became more proactive, attempting to exert his authority and starting to demolish unauthorised castles. The peace remained precarious, and Stephen’s son William remained a potential future rival to Henry. Rumours of a plot to kill Henry were circulating and, possibly as a consequence, Henry returned to Normandy for a period. But Stephen fell ill with a stomach disorder and died on 25th October 1154, allowing Henry to inherit the throne sooner than had been expected. He was buried by the side of his wife and elder son at the monastery they had founded at Faversham. Stephen must take some responsibility for the troubles of his reign. He was a competent army commander and a brave knight, but perhaps too gallant for his own good. True, he was faced by a disputed succession, but so were all his predecessors going back to Edward the Confessor, if not to Eadmund Ironside; disputed successions in most of Europe were the norm. Stephen of Blois was, arguably, a more attractive character than any of the Norman kings, but he lacked the masterfulness of Henry I. Without it, he was unable to dominate either his court or his kingdom. Moreover, he spent very little time in Normandy; only one visit, in 1137, during his entire reign. This stands in marked contrast to the itineraries of his predecessors, especially William I, and given the cross-Channel structure of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy, it was certainly a mistake. In this sense, the ruler from the house of Blois can be said to have failed because he was too English a king to realise that the Kingdom was only a part of a greater whole. When Henry of Anjou was crowned Henry II on 19th December 1154, the Bishop of Winchester, Stephen’s brother, fled the country. The long nineteen years of anarchy and weary waiting were over.

Englishmen were now free to ponder afresh the question of national identity. But when they did so, some of them felt that a page had been turned. In 1161, Edward the Confessor was recognised as a saint and two years later, the king’s body was translated to a new tomb in Westminster Abbey. A new account of the Confessor’s life was commissioned from Aelred of Rievaulx, who elegantly reworked the earlier version from the 1130s, which had sought to legitimise the pre-Conquest Norman inheritance from Edward. Aelred concluded that when Henry had chosen Eadyth (Matilda) as his Queen, their daughter had produced a new king, Henry II, our Henry, as Aelred called him, joining both peoples. He went on:

Now, without doubt, England has a king of the race of the English.

Despite the fact that, in reality, Henry Plantagenet was only one-eighth English and that he was born and brought up in French-speaking Anjou, there seems little doubt that he was able to heal the breach of the Conquest. It was during this period that England’s ancient laws, distorted by the Norman preoccupation with land tenure, were finally codified and recorded, becoming The Common Law. At the same time, the power of the old English Shire courts was strengthened.

Scene Fifty – Westminster, 1154; ‘Our Henry’… an Arthurian Romance:

When Henry Plantagenet succeeded to the English throne in 1154, he could fairly claim to be the most powerful ruler in Western Europe. His lands stretched from the Pennines to the Pyrenees, their focal point being Anjou. We don’t know whether Henry ever met ‘his great relative’, King David of Scotland, who died in 1153, the year that the Plantagenet returned to England to prepare to become King, but Aelred of Rievaulx Abbey addressed a letter to him which he enclosed in his Genalogia Regum Anglorum, in which the abbot encouraged the young Henry (about fifteen at the time of his succession) to be worthy of King David, whose last hours and death he recounted.

Meanwhile, the real solution to the transnational problems of noble family fortunes lay in the reunification of England and Normandy. This was achieved in 1154 when Henry Plantagenet, who had become Duke of Normandy in 1150, was crowned King of England due to the agreement reached between them.

In England, Henry took over the throne without difficulty; it was the first undisputed succession for over a hundred years. His first task in the Kingdom was to make good the losses suffered during Stephen’s reign. By 1158 he had achieved this. In 1157 he used diplomatic pressure to force the young king of Scotland, Malcolm IV, to restore Cumberland, Westmorland, and Northumberland to the English Crown.

As lord of an empire stretching from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees, he was potentially the most powerful ruler in Europe, richer even than the German emperor and completely overshadowing the king of France, the nominal suzerain of his continental possessions. Although England provided him with great wealth as well as a royal title, the heart of the empire lay elsewhere, in Anjou, the land of his French ancestors. Socially and culturally, England was something of a backwater compared with the French parts of the Angevin dominion. The prosperous communities of the Seine and Loire and Garonne river systems and valleys were centres of learning, art, architecture, poetry and music. Aquitaine and Anjou produced two of the essential commodities of Medieval commerce: wine and salt. These could be exchanged for English cloth, and this trade must have brought great profit to the prince who ruled over both producers and consumers. Henry had also inherited the claims of his predecessors to lordship over neighbouring territories. These claims led to intervention in Nantes (1156), an expedition to Toulouse (1159) and finally, the occupation of Brittany after 1166 and the installation of his son Geoffrey as duke.

In England, Henry’s accession ended years of political anarchy and the breakdown of royal authority during which warlords had…

… filled the country full of castles. They oppressed the wretched people of the country severely with castle-building. When the castles were built, they filled them with devils and wicked men.

Henry was determined that royal castles, which in one way or another had fallen into the hands of various barons, were to be surrendered to the Crown, and unlicensed castles, the adulterine castles which had been built in such profusion, must be dismantled. His order was openly defied by several magnates, among them Hugh Mortimer, who refused to give up the former royal castle of Brug (Bridgnorth). It had been surrendered to Henry I by the earl of Shrewsbury during his rebellion of 1102. Following the confiscation of the third earl’s lands, Ralph Mortimer may have had some responsibility for the royal estates in Shropshire, renewed by Henry I or Stephen. Hugh Mortimer (II)’s stance over Brug was a direct challenge to the authority of the recently crowned Henry II. Accustomed to belligerent independence during many years of civil war, Hugh underestimated Henry’s determination.

William, count of Aumerle, was the first of the rebellious barons to submit to the king when he surrendered Scarborough Castle, and early in 1155 Roger, earl of Hereford, who had earlier declined to relinquish Gloucester and Hereford Castles, made his peace with the king. The King then advanced with an army into the borderlands to recover Brug and discipline Hugh Mortimer who was by then more or less isolated in his defiance. The king’s army wasted Hugh’s estates and besieged his castles at Wigmore, Cleobury and Brug, whilst Hugh’s forces in turn pillaged lands in the region. William of Newburgh described the outcome:

When this man was ordered to rest content with his own lands and to surrender those which he occupied belonging to the Crown, he obstinately refused to do so and prepared to resist with all its might. But subsequent events showed that this arrogance and indignation were greater than his courage … the king obtained Brug’s surrender and granted pardon to the earl … who now became a humble suppliant.

Fifty-one – Bridgnorth, 1154; Restoring the Crown’s authority in Wales and the Marches:

Hugh was forced to submit to the king before a gathering of magnates at Brug. He surrendered the castle, but retained Wigmore, Cleobury, and his other honours, and does not seem to have been otherwise penalised. With his eye on the restoration of the Crown’s authority in Wales, he needed baronial support, particularly from those lords with lands in Wales and the Marches. There was little to be gained in alienating a baron as important in the region as Hugh Mortimer as well as antagonising the baronage in general by over-zealous punishment of one of their number.

Pride, antipathy to the house of Anjou and a possible claim to Brug Castle all played their part in what appears to have been Hugh Mortimer’s reckless opposition to the king. That he participated in his defiance in virtual isolation was perhaps an example of folie de grandeur, stemming from the status that the Mortimers had attained by the middle of the twelfth century.

To William of Newburgh, Hugh was a man of powerful of noble birth; to Geraldus Cambriensis he was an excellent knight; to the chronicler of Wigmore Abbey he was …

… worthy, brave and bold … of fine bearing, courageous in arms, judicious in speech, wise of counsel … renowned and feared above all those who were living in England at that time … the most generous and liberal in his gifts of all those known anywhere in his lifetime.

This last description of this paragon of knightly virtue may safely be disregarded as a hagiography of the Abbey’s founder. Hugh lived on for a further quarter century after these events of 1155, during which his relationship with Henry II seems to have remained an uneasy one; in 1167 he repeated his defiance of twelve years earlier when he refused the king’s command to surrender cattle he had seized from one of the king’s knights. He was fined a hundred pounds, which he refused to pay, and in 1184, after he died, it was charged against his heir, though there is no record of it ever being paid.

Meanwhile, the Welsh exploded into self-expression and self-assertion. Adopting the methods of the intruder and adapting their own, they carved out a distinctive polity, entered European politics and at one stage began to create their own feudal state around Gwynedd. In Wales, Henry found in Owain Gwynedd and Rhys of Deheubarth two well-established princes whom it was impossible to browbeat. The Welsh princes turned their native oral culture, the Bardic tradition, into a brilliant literary one, retaining its Celtic core but glossing and enriching it from the new world which had been opened to them. Through the Norman March, they gave Europe the initial form of what became one of its more brilliant and abundant literary-historical traditions, that of Arthurian romance. They transmitted it through the March, the Cymro-Norman frontier between two different communities, developed into two divergent societies with distinct laws and loyalties, customs, memories and traditions. These societies were as much Welsh as they were Norman; families on both sides of the all but invisible frontier became inextricably intermeshed; the French language inserted itself between Welsh and Latin, making important sectors of society trilingual.

In 1157, and again in 1165, English armies marched into North Wales; and though Owain Gwynedd survived both invasions, he had to pay homage and put a check on his territorial ambitions. Welsh expansionism now had to deal with England’s strength as a limiting factor: the princes, the Lord Rhys of the south and then the two Llywelyns in Gwynedd, could no longer see themselves as autonomous, purely Welsh rulers, but rather feudal underlords of the English Crown. This was a discernible break with the past. Centralisation within Wales was the only way of securing relative independence for the Welsh princes from their sovereign liege, the English king. In 1163, during another major military expedition into south Wales, Henry II had asked an old Welshman of Pencader who had joined his retinue what chances he had of victory. The old man replied:

My Lord King, this nation may now be harassed, weakened and decimated by your soldiery, as it has so often been in former times, but it will never be destroyed by the wrath of man. … Whatever else may come to pass, I do not think that on the Day of Direct Judgement any race other than the Welsh, or any other language, will give answer to the Supreme Judge of all for this small corner of the earth.

It was Gerald the Welshman who reported the old man’s speech as the climax and conclusion to his celebrated Description of Wales (Descriptio Kambriae). He had accompanied the king on his expedition, perhaps translating for Henry, hence his verbatim record. Gerald was a distinguished and archetypal member of the new establishment, descended from a Norman lord and a Welsh princess. As a churchman, he had called for the independence of the Church of Dewi Sant (St David).

Any further ambitions Hugh Mortimer had in Wales were circumscribed by the ascendancy of the formidable prince, Rhys ap Gruffydd, and he appears to have played little part in the politics of either England or Normandy. In the 1160s, with Henry immersed in the Becket struggle and troubles on the continent, Rhys’s sorties from his base in Dinefwr in the south grew into a war when Owain Gwynedd joined in, moving to lead what had become a Welsh national coalition. They regained much territory from the Marcher lords. In response, Henry mobilised a massive expedition in 1165 to destroy all Welshmen, but it collapsed in the face of bad weather, torrential summer rain, and guerrilla resistance on the Berwyn Mountains. After 1165, Henry’s attitude to the Welsh princes was far more accommodating. As early as 1155, he had toyed with the idea of conquering Ireland. But the move into Ireland did not take place until 1169-70; at first by lords from the Welsh march and then (in 1171-2) by Henry himself. As the long delay made plain, in the king’s eyes, there were matters much more important than the conquest of Ireland.

Wales remained self-governing for over a century after 1165, but there was never any real security since English troops were liable to appear anywhere in the country, and, ultimately, there was nothing to stop them from attacking except for the politics of brinkmanship or the chance of seizing independence by force of arms. In addition, the law of gavelkind in Wales meant that when Madog ap Maredydd, lord of Powys, died in 1160, his lands were divided among his sons, and Powys was never again a united country. Ten years later, Owain Gwynedd himself died, and the same thing happened in Gwynedd. Hywel ab Owain, the poet, was killed by his half-brothers, who then split up the principality between them. Hywel, perhaps because of his high birth, has been seen as the poet of feudalism, close to ideals of the princes of Gwynedd. After that, the clouds seemed to gather for princes and poets alike.

However, in the early 1170s, with Owain dead and his sons slipping back into civil war, Rhys agreed to a quasi-feudal relationship with Henry II, who had finally given up hope of a conquest of the principality. Instead, an atmosphere of mutual trust developed between the king and the prince, the latter being seen as the head and the shield of all the South and all Wales and the defence of all of the race of the Britons. Henry, sensing the moment in 1170, went for settlement. Rhys was formally confirmed in his possessions and was made Justiciar of South Wales. At what looks like the first recorded eisteddfod, all the Welsh rulers from north and south took the oath of fealty and homage to the king and by the end of the century, the frontier which had emerged over two generations had been settled.

The old kingdom of Morgannwg-Gwent had vanished, and was replaced by Monmouth and Glamorgan, the strongest bastions of Norman power in Wales. The diminished lordship of Powys faced a struggle to survive, torn three ways between Gwynedd, the English Crown and the rump of the once great kingdom. In the end, this also split in two, the southern Powys Wentwynwyn remaining loyal to the Crown and the northern Powys Fadog to the royal Welsh territory of Aberffraw, eventually becoming part of Gwynedd, whose ‘prince’ controlled most of the north, as far east as Conwy. Under Owain and some of his successors, it grew into a major force, the strongest power in Pura Wallia (Welsh Wales).

A core of the old Deheubarth was re-established, ringed by Norman lordships with a strong base in Pembroke and a royal estate centred on Carmarthen. Everywhere in Wales, kings had disappeared to be replaced by lords owing allegiance to the English king and his Welsh overlord, Yr Arglwydd Rhys, of Dinefwr. To the east and the south, stretched the Marcher lordships in a great arc from the pivot of Chester; the powerful families of Montgomery, Mortimer, Bohun and Clare continued to stamp their imprint from Shrewsbury to Montgomery and from Hereford deep into mid-Wales at Brecon. Under the Clares, Glamorgan became immensely powerful, and, heading west along the fertile coast, the beautiful Princess Nest of Deheubarth could precipitate wars over her person like Helen of Troy.

There was a permanently disputed ‘shadow land’ and endless border raiding, but in this tension, there was also some equilibrium and stability, maintained by intermarriage and changing tactical alliances. In 1188, Archbishop Baldwin preached the Crusade and imposed the Papal authority on the new cathedral churches on his grand tour through both the March and Pura Wallia, a tour chronicled by Gerald the Welshman. He was the grandson of Nest and her Norman husband, Gerald of Windsor, son of Nest’s daughter, Angharad, and the Norman knight William de Barri. Gwyn A. Williams has written of the creative tension between Cymric and Norman cultures, which produced Gerald’s work:

… the most startling and… unexpected consequence of this confrontation was the entry into history of a brilliant new literary culture, simultaneously Welsh and European, and itself without doubt the product of of a new civilisation in Wales.

Gwyn A. Williams (1984), When Was Wales? Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Once again, the Welsh had to define themselves in response to an outside challenge to produce this. The consequence was a literary renaissance in several languages. The new Latin monasteries, especially among the Welsh Cistercians, also helped to marry the traditions of European cloisters and old Welsh monastic traditions to produce the largest single body of medieval Welsh ecclesiastical manuscripts at Llantony Abbey. Along the communication networks of abbeys, Welsh friars filtered into the scholastic houses of western Europe, and European ideas filtered back into Wales. Adam of Wales and Philip Wallensis, who found their way to the University of Paris in the twelfth century, initiated a tradition. Young Welsh scholars made their way there and, in greater numbers, to its offshoot in Oxford, where they established a permanent and highly visible presence. Cambro-Normans like Gerald found a niche in the closely controlled episcopate; no fewer than three bishops were descendants of Nest of Deheubarth.

The native Welsh were admitted to much of the rapidly developing learning of Europe. Most particularly in its Welshness, the secular work of the poets enjoyed a revival, and the bardic order seems to have been reorganised. This was the age of the gogynfeirdd, the court poets, in which every court and many a sub-court had its official master-poet, and its bardd teulu, its household poet. The poets had official functions as ‘remembrancers’ to a dynasty and its people. They evolved a complex, difficult and powerful tradition which was, like the cathedrals, architectural in structure, leaving little room for individual creativity. Mostly it was a poetry of praise, morality, exhortation and legitimation, addressed to a strictly traditional concept of the prince and the lord, not much liked by the church. It is clearly derived from the pagan, druidic traditions of the old Welsh, adjusted to a world of lords and princes. What we hear is what they call the Old Song of Taliesin. It is a mutation of the British Arthurian tradition, the longest tradition in the writing of the Welsh.

It was at its strongest among the lower-order cyfarwyddion, the storytellers. It was with the arrival of the Normans that an unknown scribe wrote down his version of the Four Branches of the Mabinogi; the others followed directly into Europe via the remembrancers and the translators: Bretons, Normans, Flemings, English, and Welsh. The rough Arthur of the British moved in and out of the Celtic mythology into the realm of Arthur of Camelot and his Round Table Knights with their French accents. This renaissance was not stopped by any frontier: Norman lords soon succumbed to the charms of court poets, harpists and singers. With the Bretons strongly represented, the Cambro-Norman lords created whole schools of translators, particularly in Glamorgan and Monmouth. Flemings were among the earliest to transmit stories of Arthur and Myrddin (Merlin) into Europe through clerics. Out of this milieu came the remarkable History of the Kings of Britain written by a Breton based in Gwent, Geoffrey of Monmouth.

But the uneasy peace which then existed for the two decades from 1165 between the marcher lords and the Welsh princes came to an end with Henry’s death, since Rhys considered that his relationship with Henry had been a personal one and did not bind him to the king’s successor, Richard I, who showed none of the ‘subtelty’ of his father’s handling of Welsh affairs.

Fifty-Four; 1162-1170 – The Becket Controversy & The Murder in Canterbury Cathedral:

In 1169, the question of the coronation of the heir to the throne, Prince Henry, led to the interminable negotiations between the king, the Pope and the archbishop being treated as a matter of urgency, preoccupying the king’s attention. In 1170, Becket returned to England, determined to punish those who had taken part in the young king’s coronation. His enemies lost no time in telling Henry of the archbishop’s behaviour, to which Henry spoke the notorious words, Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? These words were taken literally by four of his knights who, anxious to win the king’s favour, rushed off to Canterbury, where on 29th December, they murdered Becket in his own cathedral.

The deed shocked Christendom and secured Becket’s canonization in record time. In popular memory, the archbishop came to personify resistance to the oppressive authority of the State, but in reality, he was championing the privileges and indemnities of the clergy over all other considerations. At the time, everyone was better off with him out of the way. Once the storm of protest had died down, it became apparent that Henry’s hold on his vast empire had in no way been shaken by the Becket controversy. Whatever the legacy of the violent murder, in the early 1170s, Henry II stood at the height of his power.

By this time, the king had already decided that, after his death, his dominions should be partitioned between his three eldest sons. Young Henry was to have Anjou, Normandy and England; Richard was to have Aquitaine, and Geoffrey was to have Brittany. Later, in 1185, John was granted his father’s other major acquisition, Ireland. The death of young King Henry in 1183 and Geoffrey in 1186 should have eased Henry’s dynastic difficulties, but Richard was alarmed by his father’s obvious favouritism towards John. An alliance between Richard and King Philip II led to Henry’s defeat, and he died at Chinon in July 1189. Although his interest in rational reform has led to him being regarded as the founder of the English common law and a great, creative king, in his own eyes these were matters of secondary importance. To him, personally, what mattered most were dynastic politics, and he died believing that in this, he had failed despite the successes of the previous thirty years.

In 1169, the question of the coronation of the heir to the throne, Prince Henry, led to the interminable negotiations between the king, pope and archbishop being treated as a matter of urgency. In 1170, Becket returned to England, determined to punish those who had taken part in the young king’s coronation. His enemies lost no time in telling Henry of the archbishop’s behaviour, to which Henry spoke the notorious words, Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? These words were taken literally by four of his knights who, anxious to win the king’s favour, rushed off to Canterbury, where on 29th December, they murdered Becket in his own cathedral.

The deed shocked Christendom and secured Becket’s canonisation in record time. In popular memory, the archbishop came to personify resistance to the oppressive authority of the State, but in reality, he was championing the privileges and indemnities of the clergy over all other considerations. At the time, everyone was better off with him out of the way. Once the storm of protest had died down, it became apparent that Henry’s hold on his vast empire had in no way been shaken by the Becket controversy. Whatever the legacy of the violent murder, in the early 1170s, Henry II stood at the height of his power.

Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Histories (Everyman’s edn.) are appended by a Translator’s Epilogue. He detailed the background to Geoffrey’s work and the transition from Stephen’s reign to that of Henry Plantagenet. Geoffrey and his world was growing old, and he was therefore offered the see of St Asaph. No alternative was available, and so he was consecrated to St Asaph in 1152, but there was no absolute obligation on him to retire immediately to the wilds of Wales.

Earl Robert had died, but his cause was rapidly rising into the ascendant. The Empress Matilda still lived, and her son Henry was growing up to manhood. His father, Geoffrey of Anjou, had died in 1151, and at his death, Henry became Earl of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. The same eventful year also saw the young Duke marry Eleanor of Aquitaine, the divorced wife of Louis VII of France. Stephen read the omens and proposed that his son, Eustace, should be crowned joint King of England with himself. But Archbishop Theobold and the rest of the prelates refused to crown him.

Writing in about 1200, after King Henry died in 1189, William of Newburgh noted of Henry II that he was unpopular with almost all men in his own days. Henry II’s apparent unpopularity with his subjects may have had something to do, for some, with his infamous early conflict with the Church, but it may also have been because, although he was king for thirty-four years he was also Duke of Normandy and Count of Anjou, he spent only thirteen of them in England. He held more lands in France than its king, while England’s wealth enabled him to outshine the German emperor. Through marriage, inheritance, diplomacy, and occasionally war, Henry II built up a huge domain, and he extended his sovereignty to Scotland and Ireland.However, he failed to give his empire any institutional unity. It therefore collapsed under his sons, Richard and John. By the time he died in 1216, John had lost all of the Angevin lands on the continent except Gascony, and England had once more been invaded by the French. Yet Newburgh also noted Henry’s other domestic achievements:

“In his laws, he displayed great care for orphans, widows and the poor; and in many places, he bestowed noble alms with an open hand… He never imposed any heavy tax on the realms of England, or on his possessions beyond the sea, … ”

But the desire of his sons for a taste of real power produced a family rebellion in 1173 in league with the Capetian king of France, Louis VII, and these events were exacerbated by an opportunistic invasion of England by the King of Scotland, William the Lion. Although Henry II eventually put down the rebellion, imposing humiliating terms on the captured Scots king, his plans continued to be frustrated by his rebellious sons, especially when Philip II Augustus ascended to the French throne in 1180 and started to exploit the differences in the Angevin family. Even after the death of the young Henry, who had been crowned king while his father was still alive, in 1183, problems remained, as Richard knew that ‘old’ Henry favoured John, so he allied with the French against his father. Henry II eventually died in 1189, a defeated man.

However, he left a great legacy in England. Having inherited a kingdom devastated by civil war, he quickly restored the stable government it had known under his grandfather, Henry I, while simultaneously ruling over two-thirds of France. He extended royal power in England by reforming both civil and criminal law. The Assizes of Clarendon (1166) and Northampton (1176) established the grand jury system, whereby royal justices and sheriffs tried those suspected of serious offences, while civil writs obtainable from the royal courts, secured the speedy restoration of those dispossessed without due process. Henry’s reign ranks as a milestone in the development of the English Common Law.

Yet ironically it is not for his successes that Henry is best remembered, but for his dubious role in the murder of Thomas Becket. In June 1162, Becket was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury. In the eyes of respectable churchmen Becket, who had been chancellor since 1155, did not deserve the highest ecclesiastical post in the land. He set out to prove that he was the best of all possible archbishops. Right from the start, he went out of his way to oppose the king who, chiefly out of his friendship, had promoted him. But it was not long before the king began to react like a man betrayed. In the mid-twelfth century, Church-State relations were beset with problems which were normally solved or shelved by men of goodwill, but which could provide a field day for men who were determined to quarrel. Henry resented the way that clerics who committed felonies could escape capital punishment by claiming the right to be tried in an ecclesiastical court.

At a council held at Westminster in October 1163, Henry demanded that criminous clerks should be unfrocked by the Church and handed over to the lay courts for punishment. At a council held at Westminster in October 1163, Henry demanded that these clerics be defrocked by the Church and handed over to the lay courts for punishment. Becket and his bishops opposed this, but when Pope Alexander III asked him to adopt a more conciliatory line, Henry summoned a council to Clarendon in January 1164. He presented the bishops with the Constitutions of Clarendon, a clear statement of the king’s customary rights over the Church, and required them to observe these customs in good faith. Taken by surprise, Becket argued for two days before giving way. But no sooner had the rest of the bishops followed his example, than he repented of his weakness in giving way. Exasperated, Henry decided to destroy Becket, summoning him to appear before a royal court to answer trumped-up charges. Becket was found guilty and sentenced to forfeiture of his estates. Becket fled to the Continent and appealed to the pope, leaving behind an English Church in confusion due to his vacillation.

In 1169, the question of the coronation of the heir to the throne, Prince Henry, led to the interminable negotiations between the king, the pope and the archbishop being treated as a matter of urgency. In 1170, Becket returned to England, determined to punish those who had taken part in the young king’s coronation. His enemies lost no time in telling Henry of the archbishop’s behaviour, to which Henry spoke the notorious words, Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest? These words were taken literally by four of his knights who, anxious to win the king’s favour, rushed off to Canterbury, where on 29th December, they murdered Becket in his own cathedral.

The deed shocked Christendom and secured Becket’s canonization in record time. In popular memory, the archbishop came to personify resistance to the oppressive authority of the State, but in reality, he was championing the privileges and indemnities of the clergy over all other considerations. At the time, everyone was better off with him out of the way. Once the storm of protest had died down, it became apparent that Henry’s hold on his vast empire had in no way been shaken by the Becket controversy. Whatever the legacy of the violent murder, in the early 1170s, Henry II stood at the height of his power.

By this time, the king had already decided that, after his death, his dominions should be partitioned between his three eldest sons. Young Henry was to have Anjou, Normandy and England; Richard was to have Aquitaine, and Geoffrey was to have Brittany. Later, in 1185, John was granted his father’s other major acquisition, Ireland. The death of young king Henry in 1183 and Geoffrey in 1186 should have eased Henry’s dynastic difficulties, but Richard was alarmed by his father’s obvious favouritism towards John. An alliance between Richard and King Philip II led to Henry’s defeat, and he died at Chinon in July 1189. Only in the last weeks of his life had the task of ruling his immense territories been too much for Henry. He rode ceaselessly from one corner of his empire to another, almost giving an impression of being omnipresent, an impression that helped to keep his knights loyal. Although the central government offices, chamber, chancery, and military household, travelled around with him, the sheer size of the empire inevitably stimulated the further development of localised administrations which could deal with routine matters of justice and finance in his absence. Thus, in England, as on the Continent, government became increasingly complex and bureaucratic.

Although his interest in rational reform has led to him being regarded as the founder of the English common law and a great, creative king, in Henry’s own eyes these were matters of secondary importance. To him, personally, what mattered most were dynastic politics, and he died believing that in this, he had failed despite the successes of the previous thirty years.

Llandaff, 1152-4; The Welsh Chronicler and Kingship:

Geoffrey of Monmouth, the Welsh chronicler of the mid-twelfth century, was born in about 1100 and his life was therefore contemporaneous with the reign of Henry I, as he died in 1154. He studied at Oxford and became a Benedictine monk. He was Archdeacon of Llandaff, c. 1140 and was Bishop of St. Asaph from 1152 to 1154, though he remained at Llandaff and never visited his bishopric before he died. His most famous work was Histories of the Kings of Britain, written in Latin, Historia Regum Britanniae. He dedicated this to Robert, Earl of Gloucester. In her 1911 introduction to the work, for The Everyman’s Library edition (577) Lucy Allen Paton wrote (from Massachusetts) of Geoffrey that:

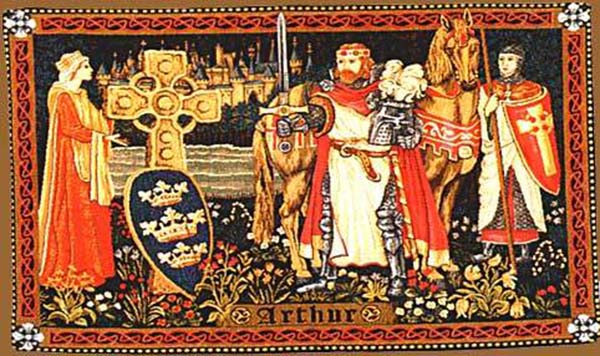

Geoffrey of Monmouth has been called again and again the father of Arthurian romance … before the beginning of the twelfth century to the name of the historic Arthur … there had already become attached much legendary and even mythological material, that his people … wistfully looked for his return to earth. Such was the general attitude of the Britons toward Arthur at the time when his story began to occupy the attention of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

About Geoffrey’s life, however, we have scant information. We know that he was a Welshman from Monmouth, giving himself the title Monumetensis, either because he was born there or because he was educated at the Benedictine monastery there. We also know that his father appears to have been named Arthur. He was probably appointed Archdeacon of Llandaff in 1140, when his uncle Uchtryd, who had been archdeacon, was made Bishop of Llandaff. The rest of his ecclesiastical career appears to have been unremarkable, even for himself, since postponed his own ordination to the priesthood until a few days before he was consecrated as Bishop of St Asaph, which was a small and impecunious see at that time.

He lived at a time when Britain was responding to the intellectual stimulus that had come to the country with the Norman Conquest. Its literary life, which had been lying dormant, began to enjoy a renaissance under the influence of scholars and chroniclers brought by the Normans. Henry I showed his appreciation for men of letters and surrounded himself with minstrels, balladeers and bards at court. After half a century of occupation, the Normans were beginning to take a keen interest in the past history of their newly-acquired domain and to turn to the traditions of early Britain. But, as Paton wrote, …

… the tastes of the Norman noble demanded something less mysterious, less fantastic, and less remote from his own world than Celtic myth afforded him, and also something more polished and entertaining than the bare chronicles at his disposal.

She claimed that it was practically certain that Geoffrey began to write his Historia Regum Britanniae as early as 1139. He dedicated the book to Robert, Earl of Gloucester, one of the most distinguished patrons of literature of the time, who rewarded him by advancing him to the archdeaconry at Llandaff. Geoffrey gathered his material from episodes in the chronicles of his contemporaries, especially William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon, in addition to the material from ancient Celtic records, myths and legends.

In their introduction to their 1948 translation of The Mabinogion, Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones wrote that the eleven stories it contained were among the finest flowerings of the Celtic genius and, taken together, a masterpiece of our medieval European literature. The stories were preserved in two Welsh collections, the White Book of Rhydderch (Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch), written down in about 1300-25, and the Red Book of Hergest (Llyfr Coch Hergest), of the period 1375-1425. But they must have been known long before the time of these earliest manuscripts, the likeliest date being early in the second half of the eleventh century. Much of the subject matter of these stories takes us back, in the oral tradition to early post-Roman, Brythonic times. These Four Branches of the Mabinogi – Pwyll, Branwen, Manawyden and Math – include the earliest Arthurian tale in Welsh, Culhwch and Olwen, and The Dream of Rhonabwy, a romantic and sometimes humorously appreciative recalling of the heroic age of Britain, as well as three later Arthurian romances, The Lady of the Fountain, Peredur, and Gereint Son of Erbin, revealing abundant Norman-French influences.

That Wales had its bards was well known across twelfth-century Europe. These bards were storytellers whose media were both prose and verse. The poetic chronicling of the eighth/ninth-century monk Nennius as well as that of Geoffrey of Monmouth, three centuries later, suggest that, by their times, these various bards had transmitted an amplitude of material in oral form, and that centuries passed before they were committed to writing in the White Book and the Red. When Culhwch first goes to Arthur’s court, the narrator supplies a list of people, which is an index to cycles of a lost story. Arthur’s warriors are a mytho-heroic assembly, set against a vast rolling panorama of lost Celtic mythology. They are the oddest retinue of any court in the world, but they form part of…

… a native saga hardly touched by alien influences, exciting and evocative, opening windows on great vistas of the oldest stuff of folklore and legend.

Without discussing the historical references to Arthur in Nennius’ Historia Brittonum, Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones were at pains to stress that Culhwch and Olwen is a document of first importance for the study of the sources of the Arthurian legendarium. The Arthur it portrays is remarkably unlike the gracious, glorious emperor of later tradition, exemplified in the later tradition of French, German and English literatures, but when we recall that Arthur of these original legends was not of any of these nationalities, but a British king, it is not unreasonable to emphasise the significance of Cymric material material relating him. This original material was uncontaminated by the Cycles of Romance, though affected by a vast complex of Celtic myth and legend, consisting for the most part of Culhwch and Olwen itself, in addition to various poems.

One of these poems, the so-called Preideu Annwfyn from the thirteenth-century Book of Taliesin, tells of Arthur’s raids in his ship Prydwen upon eight caers (fortresses) of the Otherworld. This original Arthur is a folk hero, a beneficent giant, who rids the land of other giants; he undertakes journeys to rescue prisoners and carry off treasures; he is at once savage, heroic and protective. He is therefore at the heart of the British story, both for his fame as dux bellorum (warlord) and protector of Roman Britain against all invaders, and for his increasingly dominating role in Celtic folklore and legend. It is remarkable how much of this British Arthur had survived in the twelfth-century Historia of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

By the twelfth century, Celtic influences in literature were fashionable across Europe, especially those from the Arthurian legendarium. Arthur’s position in the British story; the twofold advantage to the Normans and Angevins of Arthur as a British, not Anglo-Saxon, hero; the skill of the Welsh and Bretons as storytellers, and the excellence of the stories they told: all these were key elements of the supremacy. Furthermore, the professional men of letters of the twelfth century knew their business well. They wrote of courtly love, religion, society and morality, mysticism and poetry. A place for all of these elements was found in the Matter of Britain.

The Arthurian legendarium also became a priceless European inheritance, but in this transmission, the three Welsh prose romances under discussion were a modest matter. Their interest lies in their evidence of Welsh tradition underlying the continental expansion, with Norman-French characteristics imposed on the visceral old Welsh tales, appealing to their more sophisticated audiences. But Geoffrey created the classical form of what was passed down the centuries as the British History, rooting the Britons in a history started by Brutus the Trojan, already outlined by Nennius in the early ninth century, giving them their great hero Arthur, who now bestrides Europe, broadcasting a wealth largely mythical but compulsive history and a prophecy of redemption when an Arthur would once again sit on the throne of Britain.

The Matter of Britain swept through French-speaking Europe and across the continent from Flanders to Scandinavia to the Bosphorus and the Levant. It became a European best-seller, even as other versions of the Arthurian traditions entered the discourse of Christendom to be transmuted at the hands of Chrétien de Troyes and others into something rich and very different. By 1180, Arthur was a hero in the Crusader states of Antioch and Palestine:

The Eastern peoples speak of him as do the Western, though separated by the breadth of the whole earth. Egypt speaks of him, nor is the Bosphorus silent…

Even as ‘history’, Geoffrey’s Arthur lived long, powering a new and highly effective British national mythology. This dramatic creation of a British-European culture mirrored the growth of a hybrid society along the Welsh Marches. In his writing, Geoffrey surrounded Arthur with a court that mirrors the British-Norman life in the early twelfth century. When he is established on the throne, Arthur distributes lands, repairs the damages of war and conducts himself in general after the fashion of a Norman king of England. Geoffrey’s description of Britain at the time of Arthur’s coronation, which he modelled on a Norman festival, is often cited as a striking example of his introduction of chivalric customs into the Arthurian legendarium:

For at that time was Britain exalted unto so high a pitch of dignity as that it did surpass all other kingdoms in plenty of riches, in luxury of adornment, and in the courteous wit of them that dwelt therein. Whatever knight in the land was of renown for his prowess did wear his clothes and his arms all one same colour. And the dames, no less witty, would apparel themselves in the same manner in a single colour, nor would they deign have the love of none save he had thrice approved him in the wars. Wherefore at that time did dames wax chaste and knights the nobler for their love.

Never before had the ideals of courtly life been connected with Arthur. They had blossomed in their richest form in Southern France and did not take firm root in England until the second half of the twelfth century when they were introduced by Eleanor of Aquitaine, queen of Henry II, and by Provencal poets who sojourned in England, but Geoffrey’s descriptions are evidence that they were present in England even before that, in his day.

Geoffrey’s Arthur embodies all the virtues of the chivalric hero: Courtesy, valour, youth, glad energy, and liberality; these were all the graces cultivated in twelfth-century France. After he had established peace in the realm, Arthur is said to have held…

… such courtly fashion in his household as begat rivalry amongst peoples at a distance.

Yet Arthur was not a chivalric hero par excellence. In the Middle Ages, highway robbery provided a means for a knight to enrich his followers if he had been too generous and had impoverished himself. Arthur is described as resorting to the sword to satisfy his thirst for riches:

Wherefore did Arthur, for that in him did keep with largesse, make resolve to harry the Saxons, to the end that with their treasure he might make rich the retainers that were of his own household. And herein was he nourished of his own lawful right, seeing that of right ought he to hold the sovereignty of the whole island in virtue of his claim hereditary.

Geoffrey’s Arthur knows nothing of the virtues of mésure (moderation) and of love, without which, according to the chivalric code, no knight could possibly be of gentle heart, possibly because these qualities are incompatible with some traces of barbarism that survive in him. He is tinged with the chivalric ideals of a Norman court, but he does not perfectly represent the laws of courtly behaviour which were illustrated in later French Arthurian romance.

The contemporary chroniclers, Geraldus Cambrensis (Gerallt Cymro/Gerald the Welshman) and William of Newburgh, were both contemptuous of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Histories of the Kings of Britain. However, for Sebastian Evans, its translator, Geoffrey’s book is:

… not a history, nor even … a historical romance, but a romance of a distinct and peculiar stamp … a romance in the sense of a national epos.

A true national epos, I say, but of what nation? It is not English, not Norman, nor even Breton or Welsh. Yet all have their heroes allotted to them … In simple fact, we can never read Geoffrey aright until we realise what nation it was of which he aspired to be the national writer of the national epic. In a word, it was the national empire of his time …

Conclusion: Romancing Medieval Monarchy – An Empire from the Pennines to the Pyrenees:

In the end, Henry took over his kingdom without difficulty; it was the first undisputed succession to the English throne for over a hundred years. As lord of an empire stretching from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees he was potentially the most powerful ruler in Europe, richer even than the emperor and completely overshadowing the king of France. Out of the thirty-four years of his reign, Henry spent twenty-one on the Continent.

The actual empire of Henry I consisted mainly of England, Normandy, Wales and Brittany. At its height, the actual empire of Henry II extended, in a contemporary yet historic phrase, from the Orkneys to the Pyrenees. The dominant idea of the Plantagenet Henry II’s reign was to gradually extend the frontiers of the Anglo-Cymric-Norman-Breton empire until the descendants of the Conqueror of England would become the emperors of Christendom.

When Henry II came to the throne of England, adding the dominions held by Stephen, Normandy, Anjou and Aquitaine, it seemed that his dynastic dream could be accomplished within his reign. It was the lack of cohesion between the various constituent parts of the empire which was the greatest peril to that dream. As Paton wrote,

If only Norman and Englishman, Welshman and Breton, could be induced to work together in the common interest of the Empire there was no limit to the the potentialities of its future greatness. The restoration of an Empire mightier and broader than that of Charlemagne, nay, even that of Augustus, was no impossibility, but a practical aim, towards the attainment of which all the resources known to the statecraft of the time should be directed.

… Geoffrey… was inspired by Henry… Henry, indeed was no Augustus, and Geoffrey was far enough from being a Virgil, but in this respect the relations between the Roman emperor and the Mantuan poet were strictly analogous to those existing between the Norman king and the Welsh romancer.

To Sebastian Evans, as a translator, Geoffrey’s book was an epic that failed, for it was to have been the national epic of an empire that failed. When, in the next generation, King John lost Normandy and most of France in the early years of the thirteenth century, the Angevin empire came to an abrupt end in Western Europe. Arthur, the romantic creation of Geoffrey, who was set to have been the traditional hero of the Anglo-Norman-British nucleus of that Western empire, became a detached national hero, a purely literary, mythological figure to the early modern British who had forgotten the short-lived empire that had created him.

For Lucy Allen-Paton, too, the Historia is not a chronicle or a history, but a romance based on early British histories, combining historical, legendary and mythological material with interest and ingenuity. Geoffrey raised a national hero, Arthur of the Britons, already the centre of myth and legend, to the rank of an imperial monarch, substituting for early British stories and customs those of Anglo-Norman England. In doing so, he provided a model of knightly and kingly custom and practice and a dignified place in literature and the popular national narrative, determining the form of the romantic chronicle for many centuries to come. By extension, the entire iconography of the House of Wessex, from the story of Offa’s bloodied sword to Agatha’s black cross and the Confessor’s Green Tree, is a forgotten thread, not just of a romantic royal chronicle, but of the British national narrative.

Main Secondary Sources:

András Bereznay, et. al. (2003), The Times History of Europe: Three Thousand Years of History in Maps. London, Times Books: (Harper Collins).

Simon Keyes, Seán Duffy, Andrew Jotischky (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British and Irish History. London, Penguin Books.

Marc Morris (2014), The Norman Conquest: The Battle of Hastings and the Fall of Anglo-Saxon England. London, Pegasus Books.

Marc Morris (2021), The Anglo-Saxons: The Making of England: 410-1066. London, Simon & Schuster.

David Smurthwaite (1984), The Ordnance Survey Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain. Exeter, Webb and Bower.

Peter Rex (2013), Hereward. Stroud, Glos; Amberley Books.

Kenneth O. Morgan (1984), The Oxford Illustrated History of Britain. London: Guild Publishing.

István Lázár (1989), An Illustrated History of Hungary. Budapest, Corvina Books.

László Kontler (2009), A History of Hungary. Budapest, Atlantisz Publishing House.