Episode One

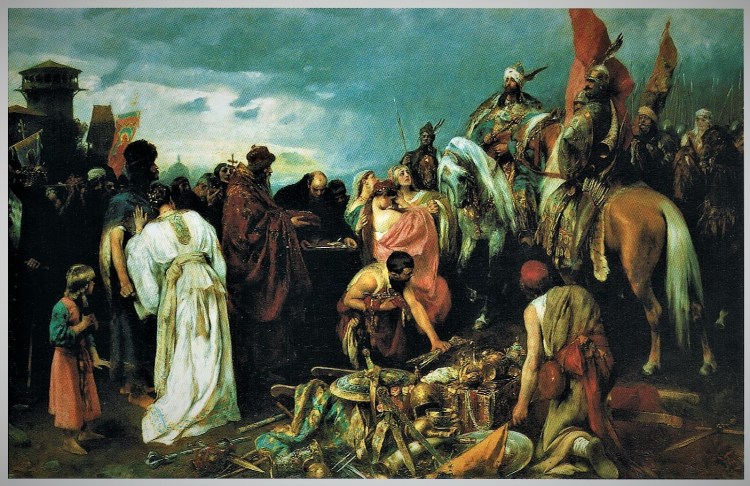

Above: Hungarians at Kyív – a painting by Pál Vágó (1853-1928). It is extremely difficult to maintain, based on archaeological relics that have been unearthed in territories now forming part of Ukraine, that these objects are unmistakably the relics of the ancient Hungarians, or Magyars. It is probable, though, that as a result of research on such finds, that many more artifacts lie hidden in the Etelköz, the region settled by the ancient Hungarians before the final stage of their migration to the Carpathian Basin in the ninth century. The early eleventh-century spires of Kyív can be seen in the background, and in the foreground to the right, a young woman appears to be being traded as a slave with Hungarian traders.

Introduction – The Turn of the First Millennium

Raiders and Traders; Feudal Lords and the Unfree:

For generations on end, large areas of northern and central Europe were devastated by marauding raiders, Northmen and Magyars, and for centuries much larger areas were repeatedly thrown into turmoil by the private wars of feudal barons. At the same time, the bulk of the peasantry lived in a state of irksome dependence on their lords, ecclesiastical or lay. Many of them were serfs, slaves bonded to their landed masters, who carried their bondage in their blood and transmitted it from generation to generation. They belonged at birth to the patrimony of a lord, a uniquely degrading condition. …

During the mid-ninth century, the Magyars began their westward migration alongside other groups. Among them were a few herdsmen, while the majority were nomadic warriors engaged in raiding and trading, often dealing in slaves, gold, and silver acquired through plunder. Through this movement, they came into contact with the Rus, the Vikings, and the Turkic-Bulgar tribes residing along the Lower Danube.

One of these ethnic groups was the On-Ogour, which translates as “Ten Arrows” or “Ten Tribes” from the Turkic. This name refers to the ten Magyar tribes that had settled in the former territory of the Bulgar-Turkic alliance since the seventh century. Most of the future conquerors of the Carpathian Basin originated from the lands between the Dniester and Dnieper rivers, known in Hungarian as Etelköz, situated in the eastern foothills of the Carpathian mountains. They were therefore well-acquainted with the shores of the Black Sea, extending down to Byzantium, the Balkan Peninsula, the Carpathian Basin, and all of Central Europe to the west of the Danube. For many of them, a passion for warfare and wandering became a significant part of their identity. They began to move west, together with other groups, from the mid-ninth century. A few of them were herdsmen and the rest were nomadic warriors, raiding and trading in slaves, gold and silver taken as plunder. This is how they came into contact with the Rus, the Vikings and the Turkic-Bulgar tribes on the Lower Danube.

But most of the future ‘conquerors’ of the Carpathian Basin were found in the lands between the Dniester and Dnieper rivers, known in Hungarian as the Etelköz, in the east-facing foreground of the Carpathian mountains. They were therefore familiar with the shores of the Black Sea down to Byzantium, the Balkan peninsula, the Carpathian Basin and all of Central Europe to the west of the Danube. For the freer among them, warring and wandering also became a passion.

In Eastern Europe, Hungarian trade connections with the Vikings began to develop along the Vistula River in the early tenth century, coinciding with the settlement of the Magyar tribes west of the Carpathians. However, by the end of the tenth century and the beginning of the new millennium, continuous raiding had made it nearly impossible for them to sustain their traditional way of life. This situation began to improve in the middle of the eleventh century, as regions gradually became more peaceful, allowing for population growth and the development of commerce. In Eastern Europe, Hungarian trading connections with Vikings also developed along the Vistula from the beginning of the tenth century, when the Magyar tribes were settling west of the Carpathians. But by the end of the tenth century and the beginning of the new millennium, the continual raiding was making their traditional way of life almost impossible to sustain. This state of affairs only began to change when, from the middle of the eleventh century onwards, first one region and then another became sufficiently peaceful for population to increase and commerce to develop.

Byzantium, Saxonia and the Kyívan Rus:

This was partly the result of the emergence of ruling dynasties in established territories like Byzantium, Saxonia and those of the Kyívan Rus. The reign of Kyívan Prince Askold, c. 860-882, was first mentioned in Byzantine sources at that time. Henry I, ‘The Fowler’, was the first of a Saxon dynasty, and his son, Otto I, grandson and great-grandson forged an empire that stretched from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Otto I came to the throne in 936, made himself King of Italy in 951 and was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope John XVI in 961.

Henry instituted strong systems of government and made clever use of ecclesiastical resources and built bishoprics and monasteries. The royal women, relatives of the reigning king, played a conspicuous role in politics during this period, sometimes acting as regents. Otto II married a Byzantine princess, Theophanu, and asserted his title of Emperor in competition to that of the Byzantines. Their son, Otto III, developed the imperial concept further before his premature death in 1002. It was left to his cousin, Henry II, to consolidate the practical governance of the kingdom, especially in Germany itself, and to forge a strong polity for his successors. Good relations were continued with the Western Frankish kingdom, as well as the newly independent Kingdom of Burgundy.

Dynastic Inter-marriage in the Xth-XIIth Centuries:

It is striking how marriage alliances in the tenth centuries created links of varying strength between the kingdoms of England, Burgundy, Germany, Bohemia, Russia, Bulgaria, and Byzantium. For example, eighteen queens, princesses and princes left Hungary to marry abroad during the reigns of the kings of the Árpád dynasty from the mid-tenth to the mid-twelfth century. A further twelve Hungarian queens were from places of origin outside Hungary, from as far west as Rheinfelden, south as Raska, east as Byzantium and north as Gniezno. This demonstrates how international many of the royal courts of Europe were in the early medieval period.

In addition, the tenth century was marked by the marauding peoples of the previous centuries, the Vikings in the north and the Magyars in the east, forming settled kingdoms themselves. In England, too, the Danelaw became almost a state within a state, as did Normandy, and in Poland the Piast rulers, especially Mieszko (963-992) extended their rule to the east, while in the south Krakow occupied a vital strategic position on the Vistula. By the second half of the tenth century, the significant expansion of the Kyívan Rus and their conversion to Christianity in 987 meant that their interests were increasingly pursued to the south and west. Later that same year, an expedition against the Bulgars on the lower Danube resulted in further, albeit temporary gains. After the Samanids succumbed to the Turks in 998, the Bulgar on the Volga also developed rapidly as trading partners, and the Volga Bulgars were supplied in turn by the Rus, who continued to trade actively with Constantinople and the Islamic regions.

Trade played a significant part in the growing importance of the Rus. The Samanid rulers of Transoxiana, the region and Persian civilization of lower central Asia, had become very rich as a result of the discovery of silver in Afghanistan. They minted vast quantities of coinage and their merchants traded across eastern Europe. There they came into contact with the Rus, who were also active traders along the Volga and as far as Constantinople.

The rapid expansion of the Kyívan Rus had much to do with trade and wealth, but cultural links also formed in the wake of these mercantile connections, which were crucially important in religious and political developments as Rus interests continued to expand westwards.

At the same time, the eastward expansion of the German empire continued apace into the eleventh century. The establishment of church centres at Magdeburg (968) and Bamberg (1007) was a fundamental component of governmental and administrative consolidation. Political relations between the princes of Poland, Bohemia, Moravia and Hungary were played out in the context of the conversion of the rulers and ruling dynasties. This was especially the case with the House of Árpád in Hungary.

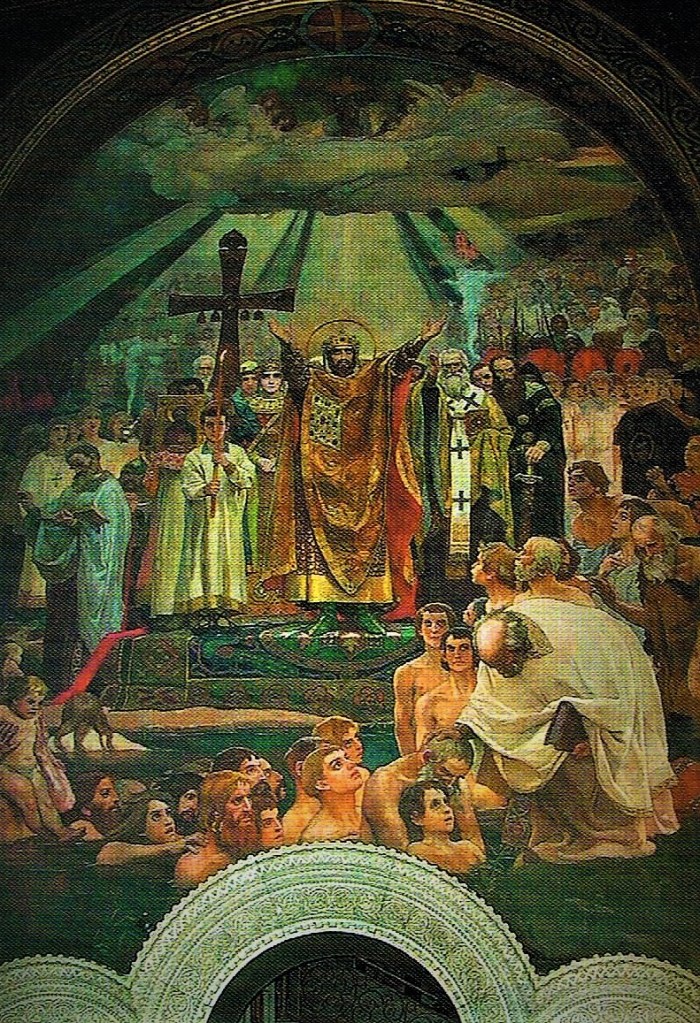

The formal conversion of Volodymyr and the Rus to Greek Orthodoxy after 987, the baptism of his people in 988, and his marriage to the Byzantine princess Anna, provided the essential link for Kyív’s future development. This process came to a formal conclusion with the first legal code, Ruska Pravda, in 1015-16. But the Kyívan state was dissolved after the death of Volodymyr I as he was succeeded by sons who each ruled separate principalities based on Novgorod, Polotsk and Chernihiv, in addition to Kyív.

The Era of István and Yaroslav the Wise:

The main problem for both the Rus and the Magyars at this point was that posed by a Turkic people attacking from the east, the Pechenegs. From 1017-37, the construction of St Sophia Cathedral and the Golden Gate took place in Kyív, at its completion commemorating the victory of Yaroslav the Wise over the pagan, nomadic Pechenegs. Its golden dome could be seen from all the hills surrounding Kyív. A painting by Pál Vágó (1853-1928) depicted “Hungarians in front of Kyív” in the early eleventh century, trading with Kyívan merchants on one of these hills, under a watchtower (see frontispiece). There appears to be buying and selling of military dress and armour, church ornaments, and slaves.

There also appear to be dark-skinned Kabers among the Hungarians, originally from the Khazar Empire, serving in the army as subject auxiliaries. Among them were Muslims and Jews, as well as a small minority of Christians. A few of them were herdsmen, but the rest were unruly nomadic warriors, raiding and trading in slaves, gold and silver taken as plunder. This is probably how they came into contact with the Rus traders and also with small bands of Vikings. Warring and wandering became dual passions for them. They were fond of home in winter, of the splendidly decorated yurt and the women they were accustomed to, who raised their heirs faithfully, while enjoying the embraces of the new slave women they had gained in battle.

The Hungarian state was being formed between disintegrating eastern and reintegrating western empires. Byzantium was experiencing centuries-long decline while the western experience was one of technical developments, growth of feudal societies and new forms of weaponry and ways of waging war. But all these developments were being challenged by avaricious Arabs, both Saracens and Moors, from the south and east while Vikings continued to raid from the north. Europe reacted slowly, with minor successor states continuing to squabble over the collapsed parts of the Roman Empire.

The still half-nomadic Hungarians could no longer content themselves with rich meadows, well-stocked streams and fertile ploughlands. There had to be a clear division of labour if they were to survive in their new homelands. Their agriculturalists could not participate in raiding parties; most of these campaigns began in the spring, the time of greatest agricultural activity, and rarely ended before the harvest. The marauders therefore constituted only one fifth of the population. On both sides of the Carpathians, a leading class was emerging whose power was based on strong military retinues in addition to material wealth. These retinues never knew a time of peace.

The agriculture of hoeing and ploughing and horticulture, together with the still rather nomadic animal husbandry, were more than adequate to meet the needs of the entire population. But the leading classes’ aspirations for power and wealth required money and the large military retinues had to content themselves with their small portions from the surplus yields of their new homelands.

The Taming of the Marauders – Augsburg, 955:

From the middle of the tenth century onwards, the rulers and aspiring rulers of Europe realised that the dynamics of incursions could no longer be supported. In Central Europe, this meant a recognition that by the constant weakening of each other’s populations and economies through raiding, all the marauding Magyars were doing was ruining themselves. Militarily, they recognised that the warfare of the Hungarian light cavalrymen was easy to see through and vulnerable, that this voracious people wedged in Central Europe could be tamed by counter-attacking their dispersed forces separately, not in isolated settlements but with united forces.

Contrary to the contentions of western European chroniclers, it was not primarily the defeat inflicted by Otto I at Augsburg in 955 that staggered the Hungarians. The victors exaggerated this news because of their intoxication with the war fever at home. It was the Hungarians’ defeat at Riade in 933 that had led to Géza, István and Andrew I transforming Hungary into a civilised Western European Catholic country.

Even as the remnants of the army headed homeward from Augsburg, internal relations in the homelands were changing. The wiser leaders of the Hungarian tribal confederations had already woken up, like their adversaries, to the fact that the restless, full-bloodied Hungarians had to be settled among the peoples within the more secure borders of Christian Europe.

By the beginning of the new millennium, the Kyívan Rus had firmer frontiers, further west, with both Poland and Hungary. Also, to the west of Hungary at this time, the upper marshes along the Danube, under Hungarian control, stretched into the Vienna Basin, even beyond Vienna itself. But news about the Hungarians withdrawing to their new borders after Augsburg had filled the raid-affected regions with a strong feeling of relief, if not exactly exultation.

The Christianisation of Central Europe and Hungary:

Across Europe, Christianisation, particularly in its western Catholic form, served to unify states. In the organisation of worldly dominion, the integrating role of ethnic groups grew. For the Hungarians, it was precisely because the House of Árpád, holding the greatest power, recognised and accepted the direction of these changes, that the country was able to put the age of raiding behind it and move into a more peaceful period in the eleventh century.

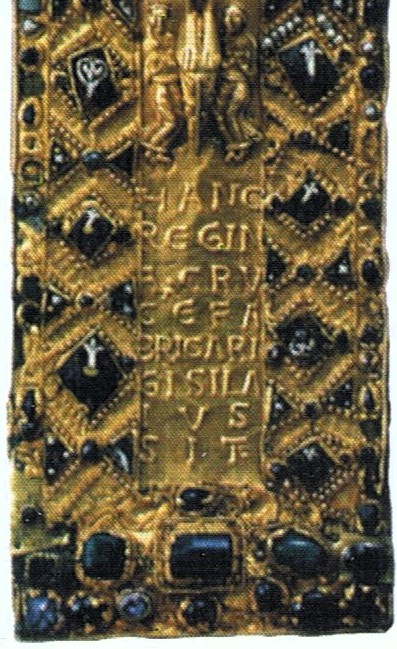

In Constantinople and Kyív, efforts were made to foster good relations with the Hungarians when Géza and István began laying the foundations of the Christian state. Géza became a Christian, but only half-heartedly, keeping many pagan customs. However, he chose Gisela, the sister of the Holy Roman Emperor and a princess of Bavaria, as a bride for his son, which was an obvious political choice, setting a Christian course for the country. She was born in Niedermunster near Regensburg and became Grand Princess of the Hungarians in 997 before being crowned as István’s Queen Consort in 1000, remaining so until he died in 1038. Throughout his reign, she was a strong supporter of his Christianisation of Hungary.

Yet the balance of power in Europe did not always benefit the pacified Hungarians as the century progressed. In the age of the marauding Magyars, those nobles who wanted to increase their power in the neighbouring regions called on the Hungarian auxilliary forces’ assistance; then a balance of power prevailed for a period in the ill-defined East European territories on the rim of the Carpathian Basin; in the middle of the eleventh century efforts to make vassals of the Christianised and settled Hungarians occurred ever more frequently.

Efforts were also made to open the western frontiers of the Hungarian territories. In 1012, St Colman took the Danube road on his pilgrimage to Palestine from Ireland and was killed by Austrian peasants mistaking him for a spy. But his decision to take the route along the Danube in itself testifies that, by the early years of the eleventh century, a new attitude was developing towards Hungary from the western Christian nations, with both pilgrims and traders being able to approach István’s crown lands without fear. Nevertheless, it was not until the time of the First Crusade in 1096 that pilgrims from the British Isles made their way across Hungary in significant numbers. By then, it was the sojourning hordes that posed the threat to regional security.

Despite the growing sense of a more settled life, many Hungarians continued to lead a semi-nomadic life. The leading classes among the Hungarians still kept their dual lodgings, changing dwelling places in winter and summer. In keeping with the custom of the people of the Steppes, they also maintained the marshlands of the Carpathian Basin as uninhabited zones of land. At the same time, the Rus created states in the core areas of the Vikings, including Aldeigjuberg (Staraya Ladoga) and Holmgard (Novgorod) in the north, in addition to Kyív.

Following the death of Volodomyr I in 1015, his sons ruled separate principalities based on Polotsk and Chernigov, including Kyív. The Kyívan principalities were reunited by Yaroslav the Wise (1019-54) who also ruled Chernihiv. According to Adam of Bremen, he had three daughters: Anna, who married Henry I of France; Anastasia (b. c. 1020), who married Andrew I of Hungary (c. 1038), and Agafija, who married the King of Norway.

Danes, Franks and Germans:

From the late ninth century, Francia was also attacked by Magyars from the east and Saracens from the south. In 987, the Capetians established a new dynasty of ‘West Francia’. At the same time, the German Empire began to emerge between the Rhine and the Danube. Emma of Normandy’s daughter by Cnut, Gunhilda, married into the German Emperor’s family.

Because of the way that the formation and survival of European states often depended on the personal authority of a single strong leader, large areas could be joined together in one lifetime. This was especially the case, in the West, with the rise of the Northern European empire of the Danes. In England, even after Alfred the Great’s settlement with the Danes in 878, the Christian faithful could not feel secure for many years, and the East Anglian diocese, for example, was not recreated until 956. Although the Anglo-Saxon and Danish populations slowly cohered into a predominantly Christian community, their troubles were far from over.

In 981, fresh Viking raids began, and a decade later, in 991, ninety-three boat-loads of Norsemen landed in Suffolk. They burned Ipswich to the ground and then marched to Maldon in Essex where they met the English in the most momentous battle of the Anglo-Saxon period, at least before 1016. Their victory at Maldon inspired the Danes to attempt the permanent occupation of England, and the Anglo-Saxons, disheartened by their defeat, made the first payments of tribute that became known as Danegeld.

The Danish king, Sweyn Forkbeard, made his initial raids in 1002-1007 and 1009-1012. Part of his motivation may at first have been revenge for the St. Brice’s Day Massacre of 1002, when the native Danish earls were massacred on the orders of King Aethelred, the ‘Unready’ or more accurately ‘ill-advised’. Another way was to get more Danegeld, since their raiding had become a royal enterprise, directed by Sweyn and his son Cnut.

Sweyn then personally led a major incursion into England in 1013. This time, it was the turn of Thetford to be ruthlessly destroyed. However, before they could ravage further, they were confronted by Earldorman Ulfcytel with the East Anglian fyrd. After a bloody battle, the Danes withdrew but returned later for a final encounter. Thorkell the Tall marched across Suffolk to meet Ulfcytel’s force near Thetford, where the English stood little chance against Thorkell’s disciplined army, though both sides suffered heavy losses in the battle. During the following months, the whole of East Anglia was devastated, so that even the invaders were unable to find food.

Demoralised and ill-led, the Anglo-Saxon armies rapidly succumbed to the invaders and Sweyn was therefore able to conquer southern England almost unopposed as the English royal family sought refuge in Normandy. Aethelred returned to England when Sweyn died at Gainsborough (Lincolnshire) in February 1014, but Sweyn’s son, Cnut was proclaimed king by the people of the Danelaw and he continued the struggle while divisions among the Anglo-Saxons handicapped their resistance. However, Aethelred succeeded in forcing Cnut out of England.

Scenes from the Chronicles – Part One: England and Hungary:

Scene One: 1014 – Offa’s Sword, Tamworth

Eadmund (Ironside) was in his twenty-first year when he met with his elder brother Aethelstan at Tamworth in June 1014. The fortified burgh was the capital of Mercia, founded by King Offa who built a royal palace, a timber and thatch construction, at the end of the eighth century. In 913, Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, made Tamworth her capital and refortified the town against Viking attacks. Aethelfled led a successful military campaign against the Danes, driving them back to their stronghold at Derby, which she then captured before dying at Tamworth in June 918.

Following King Aethelstan’s death in 939, Tamworth was again plundered and devastated by Vikings. It was soon recovered and rebuilt by Aethelstan’s successors, but it never regained its pre-eminence as a Royal centre. In the early tenth century, the new shires of Warwickshire and Staffordshire were created and Tamworth was divided between them, the county boundary running down the town centre streets. In Eadmund’s day, there was a burgh, a Saxon fort there.

Eadmund was born in about 993, the youngest son of Aethelred the Unready and his first wife, Aelgifu of York. Aethelstan, his brother, was mortally wounded in battle against the Danes in June 1014, making Eadmund heir apparent. By 1016, he and his wife Ealdgyth had two children, Eadmund the Aetheling and Edward the Exile.

There were other key contributors to the chaos which had developed under Aethelred’s rule. Eadric Streona, ‘The Grabber’ was Aethelred’s chief ‘bad counsellor’ who had risen to a position of power by 1008 by having his rivals dispossessed, mutilated or murdered. As a result, the English aristocracy was riven by feuds, unable to act as a counter-balance to Eadric in advising the King, so that he remained ‘ill-advised’ and therefore ‘unready’ to resist a full-scale invasion from Denmark.

England was then conquered by Sweyn Forkbeard, the last pagan King of Denmark (986-1014) and King of Norway from 999. Sweyn briefly ruled England after Aethelred was driven into exile. He became King of the English in 1013, but died in February 1014 at his base in Gainsborough (Lincolnshire).

Cnut was then proclaimed King of England by people of the Danelaw, but Aethelred returned from exile. Eadmund, who remained at Tamworth, rebelled against his father, whom he felt was not willing to fight hard enough to drive out Sweyn’s son, Cnut. Eadmund succeeded in this, but Cnut returned to Denmark only to assemble another invasion force with which to reconquer England.

So, Eadmund was not expected to become King, but by June 1014 his two elder brothers had died, making him heir apparent. Aethelstan, Aethelred’s eldest son, and heir, was mortally wounded at Thetford, where the second son had fallen in the battle. Before he died at the beginning of June, Aethelstan gave his brother the ‘bloodied sword’ which had belonged to Offa, King of Mercia, and urged him to continue the struggle against the invading Danes.

Offa had famously fought his way to power in the eighth century with his ‘bloodied sword’. His brother’s implication was obvious: Edward must continue to resist Cnut’s attempted usurpation with every last drop of his blood. Aethelstan and Eadmund had a close relationship; they probably felt threatened by Emma’s ambitions for her two sons by Aethelred, Edward and Alfred, fearing that they might be passed over in their favour as his successors. But there was no immediate danger of this, since both boys were safe in Normandy, and were unlikely to be brought back to England by their parents until at least the fighting was finished.

Still grieving for Aethelstan, Eadmund divided his time between the court at Westminster, Tamworth and Worcester, where he paid clandestine visits to a lady of noble birth, Ealdgyth, who was, however, already married.

Scene Two: 1016, Worcester

Ealdred was Bishop of Worcester until 1060, when he became Archbishop of York. The Chronicles he wrote became the basis for the relation of events by the monk, Florence of Worcester, up to 1117.

Despite their eighteen-month campaign together against the Danes during which Eadmund had managed to keep his father away from London and the influence of Eadric Streona, the distrust between Eadmund and Aethelred grew when, early in 1016, the King failed to appear at the muster of the fyrds at Worcester. Eadmund suspected an act of treachery or, worse still, sabotage by Streona, but he could prove nothing. The army was again leaderless, and dispersed in anger and confusion. Eadmund returned to Tamworth to raise his own army, travelling with care via London to collect levies.

Earl Uhtred of Northumbria, meanwhile, took his independent action against Eadric of Mercia, ravaging his Mercian territories. Clearly, Eadmund thought, Uhtred had his own spies at court who were aware of Streona’s latest trickery. Eadmund was Eadric’s brother-in-law, and therefore had to act circumspectly where the Earl was concerned, but he did nothing to stop Uhtred. When Cnut occupied Northumbria, however, Uhtred submitted to him and Cnut, true to his reputation, promptly had the Earl dispatched by an axe.

The native Danes’ powerbase was among the nobles of the East Midlands, especially in the ‘Five Boroughs’ in the Danelaw. The nobles there were angered by the killing of Uhtred, whom they had viewed as one of their own, given his mixed Saxon and Danish heritage.

So Eadmund took advantage of both this mood among the thegns, and Cnut’s distraction in the North, by appealing to them for support against the invaders in the raising of an Anglo-Danish army which would muster at Tamworth, a short journey from the boroughs. The response was better than Eadmund had expected, with the people of the five boroughs submitting to him. With this change in fortunes and forces, some of Cnut’s Anglo-Danish supporters lost by Aethelred’s weak leadership, including Earl Eadric of Mercia, changed their allegiance to Eadmund.

With Eadric Streona now apparently on his side, people who had sided with the Danes were punished, and some were killed. Two brothers, Morcar and Sigeferth were among them, and Aethelred had Sigeferth’s widow, Ealdgyth, imprisoned at Malmesbury. She had already attracted the close attentions of Eadmund and without his father’s permission, in the late summer of 1015, he took Ealdgyth from the priory at Malmesbury and, with the aid of a local monk, married her: She was a member of one of the strongest families in the Midlands, so Aethelred was unlikely to object. Neither did he. In the early Spring of 1016 she gave birth to twins, Eadmund (the eldest) and Edward. Ironside was energised by these births, which eased his nervousness about the succession, while also adding to his sense of responsibility for his family and the country when his father died.

That event was not long in coming. On 23rd April, Aethelred collapsed suddenly while defending London with Eadmund, and died. He was buried hurriedly, but with the honour befitting a king of England, within the city walls at Old St Paul’s. Suddenly succeeding to the throne, Eadmund wasted no time in setting up his military base and family home nearby.

Eadmund’s first campaign as king was therefore directed at restoring the kingdom’s allegiance to its old Anglo-Saxon dynasty, the House of Wessex. After the failure of his siege of London, Cnut followed Eadmund westwards into Wessex, and indecisive battles were fought at Penselwood in Dorset and Sherston in Wiltshire. Turning to the offensive, Eadmund then relieved London, parried a Danish raid into Mercia and drove Cnut onto the Isle of Sheppey, winning three out of his first five battles, without losing one. These battles, or rather skirmishes, were why he became known by the epithet ‘Ironside’, though it may also have had something to do with the symbolism of Offa’s sword, which was used at his coronation at Westminster. Certainly, he was fighting with renewed self-confidence, inspired by the birth of his two sons.

Scene Three – October 1016, Ashingdon, Essex:

However, though he had won a series of battles, Eadmund ultimately lost the war between himself and Cnut, which ended in victory for Cnut at the Battle of Assandun (Ashingdon) on 18th October.

Embarking on another raid, Cnut sailed from Sheppey and anchored in the River Crouch near Burnham in Essex. Eadmund moved to raise levies who could prevent the Danes, now loaded down with booty, from returning to their ships. In the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,

… he pursued them and overtook them from Essex at the hill which is called Ashingdown, and they stoutly joined battle there.

Eadmund had mustered a large army there with contingents from Wessex, East Anglia and Mercia, and although his ill-trained levies could not match the Danes man for man, his superiority in numbers offered the chance of a decisive victory.

As Eadmund’s army made camp at Ashingdon Hill on the evening of 17th October, the enemy was in full view just over a mile and a half away. Cnut had little choice but to fight. To avoid battle and escape by land he would have had to abandon both the spoils of his latest raid and his fleet. With an undefeated enemy so close at hand, it would have been foolhardy to have attempted embarkation when his army would be hard put to defend itself.

Instead, he assembled his force on a hill at Canewdon which stood between Eadmund and the Danish fleet, where a low ridge connected the hill from which the armies faced each other. At the Danish end of the ridge, a slight rise of about a thousand yards in front of Canewdon offered Cnut the opportunity to advance without losing the advantage of higher ground.

Eadmund deployed his army in three divisions: the Wessex contingent under his command, the Mercians under Eadric Streona, and the East Anglians led by Ulfcytel. Eadric, now in favour once again, was stationed on the right flank, with Eadmund in the centre and Ulfcytel on the left. Eadmund began the battle by charging up the hill at Ashingdon towards the Danes. The English left, due to the nature of the ground, advanced far more quickly than the right and a rapidly increasing gap opened between the flanks.

As Edmund and Ulfcytel clashed with the Danish line, at least a third of the English strength remained uncommitted, for Eadric had halted his division well to the rear, already planning another act of treachery. The Danish left, finding no troops to their front, turned inwards to envelop the unprotected English, who nevertheless continued the unequal struggle until late in the afternoon when Eadmund was eventually able to escape with the survivors of his army.

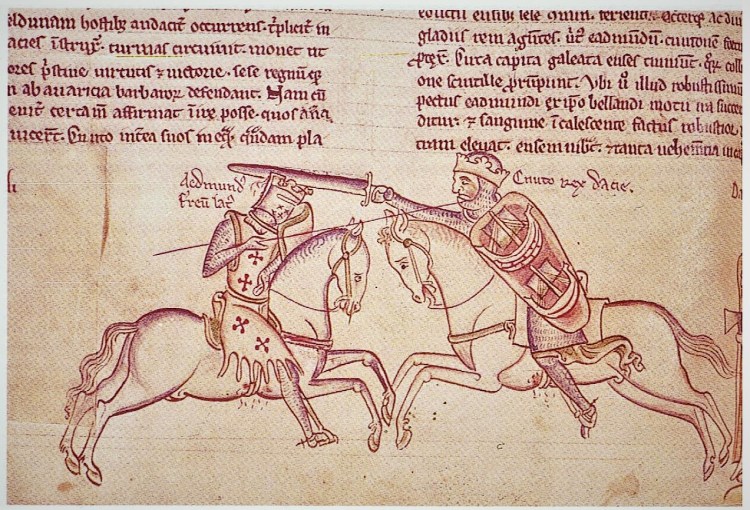

But the English were defeated and Ulfcytel, the majority of Eadmund’s troops and a large proportion of the English nobility were killed. Eadmund retreated to Deerhurst on the Severn where shortly after the battle he and Cnut met to agree on the partition of England along the old boundary of the Danelaw. Despite his victory in battle, Cnut recognised that Eadmund had already earned a reputation as a skilful and courageous military leader, worthy of continuing to rule the Kingdom of Wessex. There is an early thirteenth century depiction of the two men (shown below) in the manuscript Historia Major by Matthew Paris, fighting a duel on horseback at Deerhurst.

So, the kingdom was divided in two between the two men, but Eadmund died ‘of his wounds’ in November, though there were many suspicions and rumours about the ultimate cause of his death. Again, Eadric Streona’s whereabouts and motivations would bear investigation, were there enough surviving evidence. From there, Eadmund retired to Winchester, while Cnut occupied London.

Adam of Bremen, the trusted European chronicler, wrote, shortly after the Norman Conquest, that Eadmund had been poisoned, and some twelfth century folklore writers stated that he was stabbed or shot with a crossbow while sitting in his garderobe. Whether and how Eadric and/or his men gained access to Eadmund’s private quarters is a matter of speculation, but John of Worcester also recorded that Eadric later advised Cnut to send Eadmund’s sons out of the country, to Scandinavia, to be put out of the way, i.e. murdered, so he may well have harboured similar intentions towards Eadmund himself.

In any event, Cnut took over the Kingdom of Wessex, and with it control of the whole Kingdom of England, which he annexed to his Scandinavian empire, though he agreed to rule England as a Christian king.

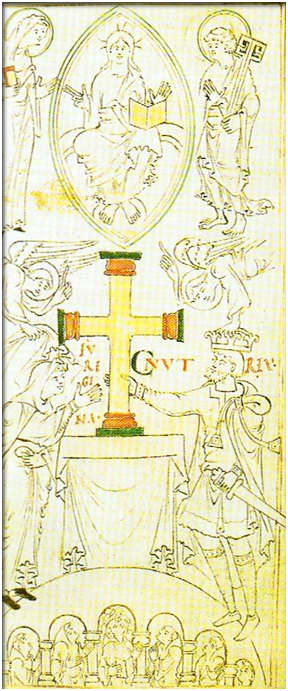

Four – Winchester Minster, 1017:

Aethelred’s death had enabled his queen, Emma, to marry Cnut. However, he also kept his first wife, Aelgifu of Northampton, who was kept in the south with an estate in Exeter, in conflict with Church teaching. He was later (1031) depicted in Christian iconography with Aelgifu presenting a cross to the new Minster at Winchester (pictured above). Cnut became conciliatory towards his conquered subjects, publicly paying tribute to Eadmund Ironside during a visit to his tomb at Glastonbury. He was himself laid to rest at Winchester.

To begin with, Cnut rewarded his Scandinavian supporters with ‘earldoms’, a Danish term, but one which came increasingly to depend on the Saxon noblemen, or thegns, at court. The political inheritance for Cnut and his successors was a kingdom dominated by two earls, Godwin of Wessex and Leofric of Mercia.

Eadmund Ironside’s death had left behind his Queen, Ealdgyth and two sons. At first, Cnut had confirmed Eadric Streona as the entitled Earl of Mercia, and he urged Cnut to have the heirs of Wessex put out of the way. John of Worcester recorded that, more specifically, he told Cnut…

… to kill the little aethelings, Edward and Eadmund, sons of King Eadmund.

But Cnut had ‘no desire’ to sully his name with the blood of children. They were only a few months old. John of Worcester continued…

… but because it would seem as a great disgrace to him if they perished in England, when a short time had passed, he sent them to the King of Sweden to be killed.

So Cnut dispatched the boys to Sweden, to King Olaf Sköttkonung, apparently with a written instruction that the boys should meet their end there. Gaimar blamed Emma for the princes’ exile, claiming that she urged Cnut to send the infants away because they were the true heirs and their presence in England might therefore cause unrest. Emma claimed that they were a threat to Cnut, but in reality she was simply concerned to secure the succession of her children by Aethelred.

According to Gaimar, the two princes were immediately sent abroad on the advice of their widowed mother, Queen Ealdgyth. But this must have been done with the full knowledge of both Cnut and Eadric Streona, who continued in his role as chief counsellor to the king. On Ealdgyth’s instructions, they were taken, instead, to a powerful thane in Denmark called Walgar (Valgarus), a housecarl or warrior, who had known the King of Hungary for some time.

Five – 1017, Gamla Stan to Gardimbre; Escape to Denmark, Sweden and Kyív:

Walgar was charged with protecting the boys, so he escorted the infants to the court of the devout Christian king of Sweden, whose capital was at Gamla Stan (‘The Old Town’ in Swedish), newly founded by Olaf, which was both a secure citadel on an island, situated on an inlet of Lake Malaren, an important trading centre near the Baltic. According to Gaimar’s account, Olaf was revolted by Cnut’s intended infanticide. Besides, the royal grandfather of the boys, Aethelred, had been Olaf’s close friend and ally. John recorded:

He, although there was a treaty between them, would in no wise comply with these entreaties, but sent them to the king of Hungary …to be reared and kept alive.

Fearing that Cnut would send assassins to the Swedish court, especially since he was already seizing neighbouring parts of Sweden in 1017-18, Walgar followed the Swedish king’s advice, taking them to the border lands between the Rus, Poland and the Hungarian crown lands. They then travelled for five days until they reached the city of Gardimbre (Gardariki was the term used for the lands of the Kyívan Rus) where they were met by King István and Queen Gizela. Yaroslav the Wise (Iaroslav Mudri) was the Grand Prince of Kyív from 1016 to 1018 and then again from 1019 to his death in 1054. The two monarchs were obviously on good terms at this time.

A divided succession had, at first, characterised the Kyívan principalities and territories in the east. But, in 1019, they had been reunited under Yaroslav in a period of political expansion and influence for Kyív as well as one of intensive cultural interaction.

Six – 1018; Royal Refuge at Esztergom, Hungary:

István and Gizela took the princes on to their court at Esztergom, where they were raised in relative safety by the royal couple for the next ten years. We know that the Hungarian king and queen received them cordially and educated them with deep affection. Towards the end of this period, Eadmund died, but his brother survived and Gizela made him her protégé, preparing him for the time when he might return to England to claim its crown following Cnut’s death.

In England, meanwhile, Cnut had had Streona executed in his purge of 1017, and Leofric became Earl of Mercia, the second most powerful man in the Kingdom. He was succeeded by his son, Aelfgar, whose son, Eadwine, became the last Earl, after the Norman invasion. By the 1020s, the Godwins had gained almost total control over southern England, south of the Thames. Cnut therefore took over a well-formed and fully operational kingdom of England in 1017 and made it the centre of his North Sea empire by extending his rule first over Denmark itself (following the death of his elder brother in 1018), then over Norway, after the expulsion of Olaf Haraldsson in 1028.

Seven – Gardoriki (lands of the Kyívan Rus) – 1028:

King Olaf fled to Sweden and laterly, to Kyív, as Cnut also seized more parts of Sweden, perhaps partly in revenge for the Swedish King’s decision to send the princes to Hungary. It may be that the Wessex prince or princes (depending on when Eadmund died) were removed to Kyív following Olaf’s flight there in 1028, when the boys reached the age of twelve, an age when they could inherit and marry. István again sent the prince(s) to Gadoriki, the lands of the royal court of the Kyívan ‘Rus’, where they could be protected and continue their education with Yaroslav the Wise, while Cnut was now ruling most of Scandinavia. The Grand Duke’s wife, Ingegard, became their guardian in this period while they were living in Hungarian ‘crown lands’ on the Carpathian frontier, perhaps in Zemplén county.

At that time there was no clear border between the Kyívan Rus and Hungarian sub-Carpathia, and the region where the national territories touched was not so well-defined as to exclude the possibility of both contemporary and more recent chroniclers confusing their physical and political data. The daughter of Yaroslav, born in about 1020, later became Andrew’s wife after he fled to Kyiv in 1038 with his brother, Levente, having been sent there to escape from the reprisals against their father’s supporters. Eadmund had died by this point (we hear nothing of him except that he died young), but Edward married Agatha, a relative of the German Emperor and Gizela’s close companion and confidant.

Eight – c. 1030; Zemplén, Esztergom and Pilismárot:

The Magyars and other raiders were also in the slave trade, especially along the Danube and the Black Sea coast, and up the Dnieper to Kyiv and beyond. Alternatively, the route northwards through Zemplén County may have been the way followed by raiders and traders on horseback. The Principality of Hungary had metamorphosed into a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king, István (Stephen) I at Esztergom around the turn of the millennium.

Zemplén county was founded as a county of the Kingdom of Hungary in the eleventh century. It shared borders with Poland (Krakow), Galicia, and the Hungarian counties; Sáros, Abaúj-Torna, Borsod, Szabolcs and Ung. The rivers Laborc and Bodrog flowed through the county, tributaries of the Tisza. This may well have been the area in which Edward the Aetheling was hidden away from Cnut’s spies and assassins, most likely at the Zemplín Castle (Zempléni vár), the county capital from the eleventh century.

Istvan’s wife, Gizela (b. c. 985, m. 996), a daughter of Henry Duke of Burgundy and a German imperial princess, was a pawn in a complex diplomatic game, but one which played an important role in stabilising Hungary’s position in Europe. István had fought against his pagan brother, Koppány, with Bavarian help in the form of German knights. In return, the Catholic Church received powerful support from Stephen through the creation of a strong Catholic kingdom in central Europe.

Esztergom was the royal capital of the Árpád dynasty, which served not only as the royal residence but also as the centre of the Hungarian state, religion and economy. István himself had been born at Esztergom, which enjoyed a privileged position among the royal residences, and played a central role in military and agricultural affairs, taxation and the minting of coins. The city had primacy among royal cities, with its central role in economic and military affairs. The various tithes and taxes gathered by the county governor had to be handed over there every year.

In the place of the Basilica stood the private chapel of Prince Géza, István’s father. Géza had married Sarolta there; she had already converted to Byzantine Christianity. Géza had also erected a protective castle on the hill. The city remained an important centre for the Árpád dynasty from the founding of the Hungarian state to the thirteenth century.

The Castle was joined to the royal residence at the top of the hill and the archbishop’s palace. The population of the settlement, called Viziváros, protected by its great walls, was ethnically mixed. There were Latin peoples from Italy, German and Jewish traders, craftsmen and minstrels, as well as male and female court servants. It may also have been at this point that Andrew’s pagan marriage to a woman from Pilismárot, a village along the Danube Bend from Esztergom, took place.

It may have been that she had been sold into chattel slavery when he first met her, from which she would have been released on marrying the prince. This form of slavery was still widespread throughout Europe in the early decades of the eleventh century, especially since the Vikings were the foremost slave-traders both in Cnut’s empire and along the Vistula to Krakow and the Kyívan lands. It was still prevalent in the crown lands of István in the early decades of the eleventh century, despite the Christianisation of Hungary. This may help to explain why Andrew was so determined to stamp out paganism during his reign.

Nine – 1032, St Edmundsbury (Bury St Edmund’s); Cnut’s Empire and Anglo–Danish Kingdom:

The years 1028-31 formed the high-tide mark of the Viking achievement and of Danish migrant integration into the British Isles and Scandinavia. Cnut always regarded England as the most important part of his empire. He maintained Anglo-Saxon laws and preserved the power of local Saxon thegns as well as giving it to Danish earls. Since it was necessary for him to leave England for long periods, he divided the kingdom into four ‘earldoms’ based on the old kingdoms of East Anglia, Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria.

Unfortunately, however, this revived the old jealousies and rivalries of the Anglo-Saxon age. Such divisions weakened the country and made it easy prey to enemies once Cnut’s strong arm was withdrawn. It was during the troubled times of the Danish occupation that feudal society developed in England, as it had done in Europe in the wake of the Norse attacks on the Carolingian empire in the previous century.

Towards the end of his reign, Cnut had gained a reputation as a wise king who knew that if he wished the English to settle in peace under his rule, he must respect their feelings. According to one recent historian,

… one of the ways in which he demonstrated a new, loving regard for his subjects was in the lavish generosity he bestowed upon the shrine of St Edmund…

The saint’s remains were restored to the town now known as St Edmund’s Burgh (St Edmundsbury), and the King now contributed liberally to the building of a new church. More than that, he founded a new community of Benedictine monks to guard the shrine. In 1032, the new church was consecrated and Cnut himself came and made demonstrative reparation for the sins of his father. He offered his crown on the altar and received it back in token that his rule had the blessing and support of the saint. He also bestowed money and lands on the abbey, making it the richest in England, and giving it jurisdiction over virtually the whole of western Suffolk. By the time of Domesday, the abbey owned extensive estates in six counties.

When Cnut died in 1035, Harthacnut inherited his kingdoms, but as he ruled from Denmark, his half-brother, Harold ‘Harefoot’ was nominated as Regent in England, despite opposition from both Emma and Godwin, Earl of Wessex. Emma was still exiled with her sons, when Harefoot became Regent. Godwin seized control of Alfred while he was en route to visit Emma at Winchester, then placing him at the mercy of Harold Harefoot in London: the Regent’s followers blinded Alfred with a savagery which caused his death. In the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,

… no more horrible deed was done in this land since the Danes came.

Alfred was abandoned by the Regent’s men at Ely, where he was found by the monks wandering blind in the marshes. He was taken into the abbey where he died shortly afterwards. The betrayal of him by Godwin permanently embittered relations between the Godwinsons and Alfred’s brother, even after he became King Edward the Confessor.

When Harold Harefoot died in 1040 and was briefly succeeded by Harthacnut, Emma returned to England with Edward, and when Harthacnut died standing at his drink in 1042, the Witan invited Edward to become king. The powerful group of Anglo-Danish earls, led by Godwin and Leofric, saw to it that Edward was recalled to England in the closing months of Harthacnut’s reign. This was taken to indicate a desire to return to the Alfredian line of kings, since not only was Edward the son of Aethelred II, of the royal house of Cerdic, but (through his mother Emma) he was descended from Rollo, the founder of Normandy. That made him acceptable to the formidable Anglo-Danish warrior-statesmen at court.

For the quarter century before Edward becoming king, England was no longer at the edge of the world, but part of Cnut’s North Sea Empire. His English kingdom was dominated by the two rival earls, Godwin of Wessex, representing the new nobles of the Anglo-Danish régime, and Leofric of Mercia, representing the entrenched political interests north of the Thames. The Anglo-Saxons sat at the edge of a period of violent confrontation and forced engagement with the rest of Europe.

In the 1030s, Anglo-Danish society was also more divided between ‘freemen’ and bonded peasants or ‘serfs’ than English society had been before Cnut’s conquest. Freemen gave up their land to the powerful thegns, or earls (yarls) as they were now known, in return for protection. The earls restored the land but demanded labour services in exchange.

Ten – c. 1035-1038, Kyív – Exiles at Yaroslav’s Court:

Georgius (György), the ‘illegitimate’ son of Andrew, was probably born sometime in the mid-1030s, to the woman from Pilsmarót. By then, Georgius’s mother may have been a servant in the royal residence who married Andrew and went with him to Kyív, where she became a lady-in-waiting to Anastasia, Yaroslav’s daughter. The marriage was probably made under pagan rites and was subsequently ‘put aside’ when Andrew became a Christian and married Anastasia. Georgius later became a Kyívan Rus noble and protector to Edward and his family, fighting alongside him in Hungary and accompanying the Wessex family on their journeys to England and Scotland.

Andrew and his brothers were the sons of Vazúl, Stephen’s half-brother, whom the King had blinded for treachery, and his concubine from the Tátony clan. According to the historian Gyula Kristó, Andrew was the second among Vazul’s three sons. He also wrote that Andrew was born around 1015. Vazul was blinded during the reign of his cousin. The king ordered Vazul’s mutilation after the death, in 1031, of Emeric (Imre), his only son surviving infancy. The contemporary author of the Annals of Altaich wrote that the king himself ordered the mutilation in an attempt to ensure a peaceful succession to his own sister’s son, Peter Orseolo.

According to the Hungarian chronicles, King Stephen wanted to save the young princes’ lives from their enemies in the royal court and counselled them with all speed to depart from Hungary. After enduring many hardships, Andrew and Levente established themselves in the court of Yaroslav the Wise, Grand Prince of Kyív (1019–1054) in the late 1030s. This must also have been the about time when Eadmund and Edward arrived at court with Georgius and his mother, travelling from Pilismarót via Zemplén. The grand prince gave his daughter Anastasia in marriage to Andrew (probably in c. 1038). Kristó writes that Andrew, who had up to that time remained pagan, was also baptized on this occasion. It was at this time that Andrew, Georgius and Edward, all by this time in their mid-twenties, fought against the pagan Pechenegs with Yaroslav before returning to Hungary in 1046.

Harald Sigurdsson, (also born c. 1015), half-brother of King Olaf II of Norway, spent several years at the court of King Yaroslav, after fleeing from Norway while still in his teens in the 1030s. He would likely, therefore, have also been a fellow exile of Edward the Exile and Andrew of Hungary. He then travelled to Byzantium, rendering service to successive emperors from Constantinople to Sicily and Bulgaria, before returning to Norway in the mid-1040s, where he earned the epithet ‘Hardrada’ (hard ruler), by ruling with a rod of iron.

Eleven – 1038-46, Fehérvár/ Réka:

Andrew (András) had been born about the same year as Edward, 1015-16, and Edward may have fought with him against the Pechenegs. At some point in the 1030s, they were brought together in Kyív by Andrew and Levente’s exile, as sons of Vazúl. István died in 1038, and András and Levente returned to Hungary in 1046 at the invitation of the Hungarian nobles. Edward had probably returned to the royal court and married Agatha before István died in 1038, when the king was considering naming him as his heir, and, according to the Hungarian sources, he settled down with Agatha on the estates granted to them by István before his death, at Mecseknádásd in the southern county of Baranya.

This was in the Mecsek hills close to the cathedral city of Pécs, an area which became known as the terra Britannorum. It was probably considered remote enough within Hungary from Esztergom to provide a safe home for Edward and Agatha to raise a family, out of the reach of Cnut’s Danish successors before the Exile’s uncle, Edward the Confessor, returned the House of Wessex to the throne in 1042. Due to his kinship with the new English king, in 1043, Edward (the Exile) was elevated…

… to a position of sole responsibility where England’s crown or domestic alliances were concerned…

This shows that Edward was likely to have been in contact with the Confessor’s court long before Bishop Ealred’s visit some twelve years later. Margaret is said to have been born at Réka Castle, near the village of Mecseknádásd in 1045/6, and her sister Krisztina was probably also born there, but Eadgar may have been born (c 1051) at the Royal Court in Szekesfehérvár, to which the Royal couple returned in 1046, to aid Andrew I in gaining control of Hungary and in consolidating the Catholic Church. Edward is likely to have accompanied him on his journey from Kyív to Székesfehérvár, together with Georgius. He also fought with Andrew’s army against the pagan rebels.

Szekesfehérvár, or simply Fehérvár, was the white city in central Hungary, which Andrew and Anastasia made their home in 1046, so much so that one of Andrew’s epithets was fehér (‘the white’). It was founded by Grand Prince Géza in 972 as the original royal residence and capital of Hungary under the rule of the Árpád dynasty, and it still held a central role in the Middle Ages, with significant trade routes to the Balkans and Italy, as well as to Buda and Vienna. It was also connected by a military road to the east. In addition, it was an important place of sojourn for pilgrims en route to the Holy Land.

For many people across Central-Eastern Europe, the colour white had a mystical association with both power and purity. Linguists point out that many capital cities contain the word white, without any topographical or geological reason. For instance, the ancient name of Belgrade was Castro Blanca, or Nandorfehérvár in Hungarian. Ethnographers say that migrating peoples from the east identified the colour with cleanliness, holiness, luxury and power. The migrating Magyar tribes were said to have sacrificed a white horse on entering the Carpathian Basin. So the association of white with the Hungarian royal city is obvious in its name, Fehérvár; The White Burgh.

Its location in the Dunántul (west of the Danube), surrounded by marsh land with limestone ruins of Roman buildings, had been chosen as a location for the princely residence they decided to call the Feherű Vár. This name survives from Latin charters of the early eleventh century. It can also be found on the chasuble prepared for the Fehérvár basilica and on the coronation mantle. In addition, it is mentioned in the Deed of Foundation of Tihány Abbey of 1055, the earliest surviving relic in the Hungarian language.

The Latin name of the residence in Latin was Alba Regio, When King Orseolo of Venice put the coronation city at the disposal of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, in 1045, the German garrison named it Stulweissenburg. The royal palace was situated on dry land surrounded and protected by immense marshlands. Water from the Sárvíz and Gaja rivers created a system of lakes which guarded the four hilly islands.

The environment resembled the Etelköz, the legendary land between the Dniester and the Dnieper, inhabited by the Hungarians before they were forced to migrate further westward. The Royal Palace was also at a crossroads of trade and military routes. Prince Géza built a fortified dwelling place at this crossroads, and a quadripartite church. He protected the city with a ring of smaller settlements and settled the fearsome Pechenegs to help protect the territory on the sandier side of the Sárvíz river.

The castle was already standing by the time István and Gizela were crowned at the turn of the millennium. In the first half of the eleventh century, it was surrounded by a stone wall. During the period of the Árpád dynasty, there were five altars (side chapels) in the church. The classification of the dynastic family and state church differed from the other early episcopal churches in that the Bishop of Székesfehérvár was not subordinate to the authority of the Archbishop of Esztergom. Above all, he performed the state ceremonial duties and was the custodian of the crown, the orb, the double cross, István’s cross, the sword and the rest of the royal regalia.

The consecration of the royal basilica did not take place with the death of István, but seven years later at the funeral of his son and heir, Prince Imre. As its founder, István was buried in a stone coffin in the nave. The city’s outer settlements were strengthened in the twelfth century, when settlers from Northern France, perhaps Normans, settled in the virtually uninhabited area.

Twelve, 1045-6 – Gizela’s Black Cross and Abaújvár:

The German Emperor Henry II was King István’s brother-in-law, being brother to Gisela, Princess of Bavaria and István’s Queen Consort. Her retinue of knights and priests had helped István to establish Hungary as a strong, Catholic state and to defend it against his power-hungry pagan relatives, the Pechenegs, before he died in 1038. Gizela had a young Bavarian noblewoman as her trusted companion and confidante, Agatha, possibly her niece, the daughter of Bruno, Bishop of Augsburg. Edward met and married Agatha following his return from Kyív in 1038. After István’s funeral, the couple left the Hungarian Court for the lands in southern Hungary (Baranya) given to them on their marriage by the King. This formed the basis of the statement in English records that the exiled prince exercised power and patronage over his Hungarian tenants.

Gisela’s mother was the wife of Henry of Burgundy and sister of the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II, who was also Agatha’s uncle. She died in 1007 and her daughter donated a black burial cross, called the Giselakreuz, which she had made for her mother’s grave. On the cross, at Jesus’ feet, are two kneeling figures. One is Gisela herself and the other is her mother, who was also named Gisela, dressed in a nun’s habit. The cross bears a strong resemblance to the description of the one that Queen Gizela gave to Agatha when she left Hungary for Passau in 1045. Gisela lived out the rest of her life in the nearby nunnery of Niedernburg, where she died in 1063, aged about seventy.

The crosses were made of gold, but set with dark stones. Such stones were rare in Europe at that time, and reminiscent of the imperial grandeur of the Carolingian Emperors, who popularised their use. So it is probable that Gisella’s cross had its origins in Bavaria. Agatha bore three children with Edward: Margaret (born c. 1045/6), Christina and Eadgar (b. 1051). Their first two children were born at Réka Castle, near Mecseknádásd, and spent their early childhood there before returning to court at Szekesfehérvár, sometime before the birth of her brother there.

Having become an Orthodox Christian in Kyív in c. 1038, to marry Anastasia, András returned from exile in Kyív to Szekesfehérvár and became a devout Catholic, giving him his other epithet, the Catholic. After István’s immediate successor, son of his sister and the Doge of Venice, Peter Orseolo (1038-41 and 1044-46), had traded Hungary’s independence for the German Emperor’s help in restoring him to the throne, the feudal lords of Hungary had turned to András and his brother Levente, in exile in Kyív, to re-establish order.

In 1046, the dukes agreed to send envoys to András and Levente in Kyív to persuade them to return to Hungary. Fearing some treacherous ambush, the two brothers only set out after their agents in Hungary, including Georgius and Edward, confirmed that the Hungarians were ripe for an uprising against Peter. In 1041, the opposition to him had ejected Peter and made Samuel Aba king. By the time the two brothers decided to return, after a further five years, a further revolt had broken out in Hungary, which Aba could only put down by mercilessly murdering fifty lords. Peter returned to reclaim the throne with the help of Henry III, the Holy Roman Emperor, ruling for a further two years. But the territories neighbouring Hungary were dominated by pagans who captured many clergymen and mercilessly slaughtered them. They wanted to make vassals of the Christianised and settled Hungarians.

Andrew met the pagans at Abaújvár, near the current Slovak border in Northeast Hungary. The castle there was the main place of residence for the Aba family, the second most important royal house of Hungary and one of the most important Hungarian families of the time. The first known written record on Abaújvár dates back to the events of 1046, but presumably an earth castle stood there much earlier; the new stone castle was built by Samuel Aba before he became, briefly, King of Hungary. An Illuminated Chronicle narrated, perhaps with some bias, how the pagans urged the dukes…

… to allow the whole people to live according to the rites of the pagans, to kill the bishops and the clergy, to destroy the churches, to throw off the Christian faith and to worship idols.

Samuel Aba fell in one of the battles for the throne, perhaps killed by a treacherous assassin, but András caught Peter attempting to flee the country, deposed him and had him blinded. Aided by Edward and others from his Kyívan retinue, András then put down the pagan rebellion and he and the descendants of Vazúl were restored to the throne, ruling Christian Hungary for a quarter of a millennium.

Thirteen; 1051-1054 – Westminster; the struggle to succeed King Edward:

Meanwhile, in England, the childless Edward the Confessor, educated in Normandy and a Francophone, revealed his wish to be succeeded by his mother’s great-nephew when the latter visited Edward’s court in 1051. Edward had spent most of his boyhood among priests while in exile in Normandy, and was more fitted to being a monk than a monarch.

Nevertheless, Edward did become king and began a largely peaceful reign which lasted for nearly twenty-five years, despite the continual threat of a Scandinavian invasion and the internecine power struggle between the earldoms of England, which had become the power bases of the rival dynasties of the Godwin of Wessex, Siward of Northumbria and Aelfgar of Mercia.

In 1053, Earl Godwin and his sons, Leofwine and Harold, launched an incursion into England, which King Edward was powerless to resist. As a result, royal authority was undermined, the Norman connection was temporarily severed and the House of Godwin was restored in an almost unassailable position. But the other Anglo-Danish earls, jealous of the power of the Godwin family, refused to make a united front with them against the Normans. Nevertheless, according to the pro-Godwin Life of King Edward, written in 1065-70, the Godwins’ return to London was greeted with deep joy both at court and within the whole country.

The Godwins then became so powerful that Edward began to look for alternative heirs as ‘compromise candidates’ to both Harold Godwinson, who was about thirty in 1053, and William of Normandy. In the same year, Earl Godwin died suddenly of a seizure at Court. He had emerged as the most powerful earl and his authority was such that even his exile in 1051-52, and the King’s hostility could do little to diminish it. As king, he paid little attention to affairs of state and devoted himself instead to prayer and worship and the concerns of the Church.

But Edward could not afford to ignore the matter of the succession, especially as he was childless. Educated in Normandy and a Francophile, he preferred to be succeeded by his mother’s great-nephew whom he had got to know well during his time in Normandy. But he also knew that William’s claim to be England’s king was dubious even in contemporary terms. Certainly, William’s great aunt Emma had been the wife of King Aethelred, and Edward himself had given William a more recent claim by naming him as his successor during William’s visit to the English Court in 1051, albeit privately. But, a direct claim through the male line was much stronger for his courtiers and his country.

However, as yet apparently unknown to (most of) the Court, there was a claimant with a direct male bloodline to the throne; Edward Aetheling, son of Ironside and grandson of Aethelred, who was in exile at the court of András I, the King of Hungary. By 1054, opposition to William’s succession was formidable, especially from the anti-Norman faction at court, led by the Earldom of Wessex, which Harold himself now led. At this point, too, rumours began to spread, from the continent, of the survival of the direct line of the Wessex royal family in Hungary. They soon reached Edward’s ears and those of that faction at the English court that wanted neither William nor Harold to succeed to the throne. These courtiers began to show an interest in the exiled Prince Edward of Wessex as an alternative heir to the English throne.

Fourteen; 1053-58 – Köln, Tihany and Tiszavárkony:

Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester was the leader of this faction, the partisans of Wessex, and he was now commissioned by the Confessor to locate the Exile and his family and to invite them to return to England to meet his uncle. Ealdred also had his mission, to become the first English churchman to travel on pilgrimage through Hungary to the Holy Land. He was to deliver a letter to the Hungarian court, requesting the return of the Wessex family, before progressing on his pilgrimage. In the event, four years after leaving England, he finally arrived in Jerusalem in 1058.

But the first part of his mission was to deliver a letter to the imperial court of Henry III at Cologne, requesting his help in locating the prince and requesting that he negotiate with the king of Hungary, András I, for his return. Meanwhile, the German emperor had delayed his response to Edward’s request and kept Ealdred waiting for more than a year. Dealing with widespread unrest in his German empire, Henry III then fell ill and died while suppressing a Slav uprising in northeast Germany in October 1056, aged just forty. He was succeeded by his son, Henry IV, who was only six when he came to the German throne. In these circumstances, it’s perhaps not surprising that the imperial officers could not help the English king in his search for the lost English prince.

At Székesfehérvár, meanwhile, Anastasia of Kyív had given birth to two sons, Salomon (‘Solomon’) (1053) and Dávid (c. 1055). Margaret, then aged ten or eleven, helped to care for the two young boys, especially Dávid, whom she grew so fond of that she later named her youngest son after him. But the Hungarian royal family suffered a disaster when András had a stroke, which paralyzed him; fearful for his mortality, András attempted to make Solomon’s succession more secure, even against the rights of his brother, Béla, who had his strong claim to the succession according to the traditional principle of agnatic seniority.

However, the brothers’ relationship did not deteriorate immediately after Solomon’s birth, partly because he had given Béla his dukedom covering a third of the kingdom. In the deed of the foundation of the Tihány Abbey, a Benedictine monastery established in 1055 by András, Duke Béla was listed among the lords witnessing the consecration. This charter, although primarily written in Latin, contains the earliest extant text written in Hungarian; Feheruaru rea meneh hodu utu rea (“on the military road which leads to Fehérvár”), also demonstrating the strategic importance of Szekesfehérvár as a royal city and citadel at that time.

In an attempt to strengthen his son’s claim to the throne, Andrew pressed on with his plan and had the four-year-old Solomon crowned in the one-year-long period beginning in the autumn of 1057. Certain English forms and ceremonies were observed at the coronation, suggesting that the Wessex family were witnesses, or at least guests of honour. It is also possible that Bishop Ealdred, on mission to find the Wessex family, had arrived at Szekesfehérvár and attended the coronation ceremony, perhaps participating in it before resuming his pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

For the same purpose, András also arranged the betrothal of his son to Judith, a daughter of the late Emperor Henry III, and sister of the new German monarch, Henry IV (r. 1056–1105), in September 1058. Thereafter, according to an episode narrated by most Hungarian chronicles, the king invited Duke Béla to a meeting at Tiszavárkony, a castle on the River Tisza. At their meeting, Andrew seemingly offered his brother to freely choose between a crown and a sword, which were the symbols of the kingdom and the dukedom, respectively.

At what became known, dramatically, as the Várkony Scene, Duke Béla chose the sword, since he had previously been reliably informed by his partisans at Andrew’s court that he would be murdered on the king’s order if he opted for the crown. Béla then rode quickly back into exile in Poland, where he raised an army and returned to Hungary at the head of it. He defeated his brother, who died of his battle wounds (said to be caused by being crushed under wagons) soon afterwards. Andrew was buried at the Abbey at Tihány, which he had recently founded. During the civil war that followed, Queen Anastasia took refuge with her two sons in Austria.

Fifteen; Spring, 1058; Flanders and Westminster – Return of the Exile:

Whether Edward the Exile was still in Hungary and present at the Várkony Scene is impossible to discover. But given the turmoil in Hungary, the Wessex family may not have regretted leaving the country when they did, in 1058, even though this meant ‘returning’ to a country none of them knew, except by report, and the reports were not entirely encouraging, since they too were of dynastic disputes.

Although King Edward the Confessor, then in his late fifties, had been on the throne since 1042, the power behind the English throne in 1058 was Earl Harold Godwinson, of whom the exiled family could have heard very little before they arrived in England. Like the Wessex family, King Edward had spent most of his childhood and early manhood in exile, in his case in Normandy, succeeding to the English crown in what was then considered to be middle age, at forty.

Everything known at the English court about the Wessex exiles in 1057-58 came from the pen of Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester, who had visited four or five years earlier the court of the German Emperor in Köln on King Edward’s ‘business’. By that time, civil war had broken out in Hungary, so the spring of 1058 would have been an opportune time for Edward and his family to leave Hungary for England.

No details of their cross-continental journey or their arrival in England are recorded in the Hungarian or English chronicles. However, from the Scottish annals, we know that the Wessex family were accompanied to London by a retinue of Hungarian nobles, led by Andrew I’s illegitimate son, Georgius, who, together with others among them, later settled in Scotland. They probably travelled overland via Austria and Bavaria to the imperial palace in Cologne, and thence via Aachen to Flanders. This royal Hungarian guard must have provided strong protection, not just from attacks on the journey, but from foul play at the English court.

It was not surprising that Edward the Confessor had sought solace and counsel among the men he had grown up among in Normandy, but he had no great plan to ‘Normanise’ England or prepare the way for an invasion or occupation under his nephew. He had, however, been educated in Normandy and admired the Normans as a people, famed for their religious zeal as well as for their skills in warfare. Their enthusiasm for the Church was shown by the number of churches they built in their homeland, and their military strength by the castles they erected. The Norman abbots and bishops were among the best educated in Europe. Edward therefore desired to keep a significant number of Frenchmen at his court while remaining committed to the Wessex succession.

After almost three years, the Emperor Henry had refused the Confessor’s request for his help in locating the Exile, and Ealdred had continued his quest unaided. This was a time of tension between the German Empire and the Hungarian monarchy, when the latter was seen as being in rebellion against imperial rule. Nevertheless, the Confessor’s letter recalling the Exile and his family to England was finally delivered by Ealdred in 1057, and the Wessex family arrived from Flanders in the Spring of 1058.

The family reached England independently, though there was a suggestion that Harold went to Flanders, ostensibly under King Edward’s orders to meet them and bring them safely to London. But Harold seems to have had other plans when he met them. Six days after arriving in London, on 19th April, Edward of Wessex died mysteriously before his audience with the Confessor could take place. The Worcester (D) version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported that we do not know how he was prevented from seeing his uncle in those six days, but there were suspicions that he had been murdered (perhaps poisoned) on the orders of Harold.

Someone wished to prevent this meeting, and suspicion fell on Harold, either acting in his interest, or as an agent of William of Normandy. Before the family arrived in England, Harold had gone to the continent on a mysterious mission, prompting speculation about the purpose of his journey and whether it was somehow connected to the arrival of the Wessex family. After travelling half way across Europe, Edward was buried in Old St Paul’s churchyard.

Sixteen – Rhuddlan, 1063; Mercia and Wales:

The Danish Conquest had destroyed respect at court for the Wessex inheritance and had created new, powerful Ango-Danish aristocratic dynasties, like the House of Godwin. Harold was determined not to allow either William or the Exile to block his path to power. Aelfgar, Earl of Mercia, had been declared an outlaw in March 1054 and twice exiled in the 1050s, the second time in 1058. On both occasions, he sought and was given the support of Gruffudd ap Llewelyn, who had defeated the levies of Hereford in October 1055.

By then, the four Godwin brothers controlled every part of England. In Northumbria, when Siward died, his son Waltheof was passed over as his successor in favour of Tostig. This threatened the equilibrium of the country. Aelfgar died in 1062, but his sons did not immediately succeed him, thus weakening the resistance to the Godwinsons. Ealdred was appointed Archbishop of York in 1063, the only remaining powerful representative of the Mercian interest. The Godwinsons decided to deal with Gruffudd ap Llewelyn in 1063 in a combined operation by Harold and Tostig, involving an unannounced attack on Rhuddlan. Gruffudd was killed in the attack and Wales was subdued.

Also in 1063, Edward the Confessor recognised Eadgar, aged twelve, as his Aetheling. He was supported by many Saxon bishops and thanes, but opposed by the Godwinsons, who persuaded the Witangamot, the Council of elders, that Eadgar was not old enough and not educated enough to be considered as king as yet. By this time, the Godwinsons controlled three of the four earldoms of England, so they therefore controlled the temporal lords in the Witan.

Seventeen; 1064, Rouen – Harold The Oathbreaker:

In 1064, King Edward sent Harold to Normandy to persuade William to withdraw his claim to the English throne. But Harold and his retinue were shipwrecked off the coast and when he was rescued and brought to Rouen by William’s men, the Duke would not agree to the request. Harold may have replaced his father as the power behind Edward’s throne, but William had been holding one of Harold’s brothers, Wolfnoth, and another relative, Hakon, hostage since Edward had first promised the throne to him in 1051. To gain their release, Harold agreed to support William’s claim.

William went further, however, and made Harold swear an oath on sacred relics to uphold the Duke’s claim. However, this part of the story seems to have been a later embellishment by a pro-Godwin chronicler seeking to justify Harold’s behaviour at this point and then later, in breaking his oath. A better-placed contemporary chronicler, Eadmar of Canterbury, made no mention of Edward’s promise or of the idea that the hostages were kept to keep Edward and Harold to their promise to uphold William’s claim. Whatever the basis of the story of Harold the oath-breaker, at the time Harold must have realized that he was in a dangerous position, in which he had to agree to what William wanted, under duress and in direct contradiction to his interests.

Eighteen, 1054-65; Northern England, Wales and Scotland:

Just as in other parts of Europe, by the mid-eleventh century, the nations and regions (or earldoms) of Britain were becoming increasingly inter-related in a variety of ways, especially in dynastic terms. It’s possible that Malcolm Canmore was already acquainted with the Wessex royal family at the Court of Edward the Confessor, having escaped from his father Duncan’s usurper, Macbeth. It’s also possible that Malcolm was at the court of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney and Macbeth’s nemesis. The usurper had ruled Scotland for seventeen years, from 1040 to 1057, until the House of Dunkeld was restored under Malcolm in 1058.

In 1054 Earl Siward of Northumbria had invaded Scotland with Malcolm, who had been in exile at Edward’s court, deposing Macbeth and installing Malcolm in succession to his father, as rightful king in 1058. Siward died in 1055 and was succeeded as Earl of Northumbria by Gospatrick. In 1061, Malcolm reclaimed Cumbria from Northumberland, resulting in continuing conflict between the two kingdoms over who ruled in these border territories.

Orderic Vitalis, the chronicler, claimed that Malcolm had already become betrothed to Margaret when he visited Edward’s court in 1059, a year after his coronation and after her arrival there. He had previously been married to Ingibjorg, the widow of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, and had his first two sons with her. Ingibjorg died before Malcolm’s marriage to Margaret.

In 1063/4 Tostig had two of Gospatrick’s men murdered, and then the Earl himself. Tostig then became the new earl, but the Northumbrians viewed him as a southern imposter and his arrogant behaviour led to the successful rebellion led by Morcar, who was acclaimed as the new earl.