Part Two: 1965-2024.

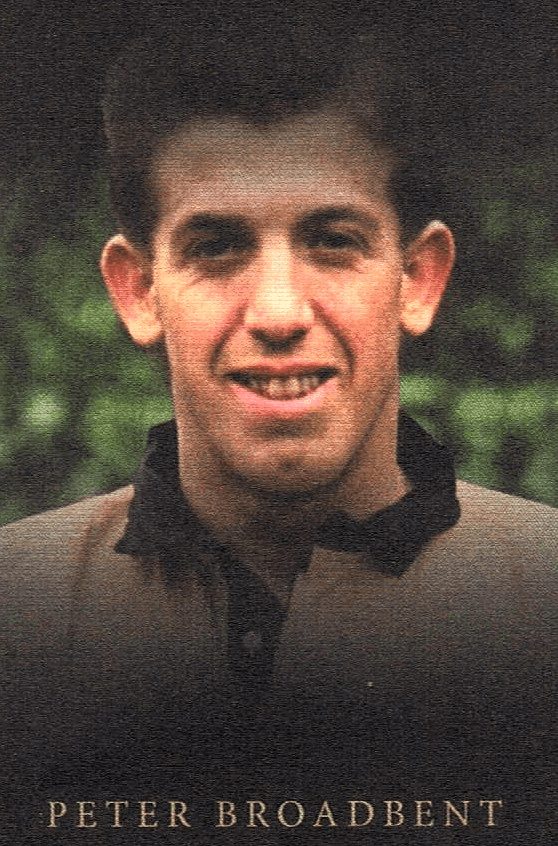

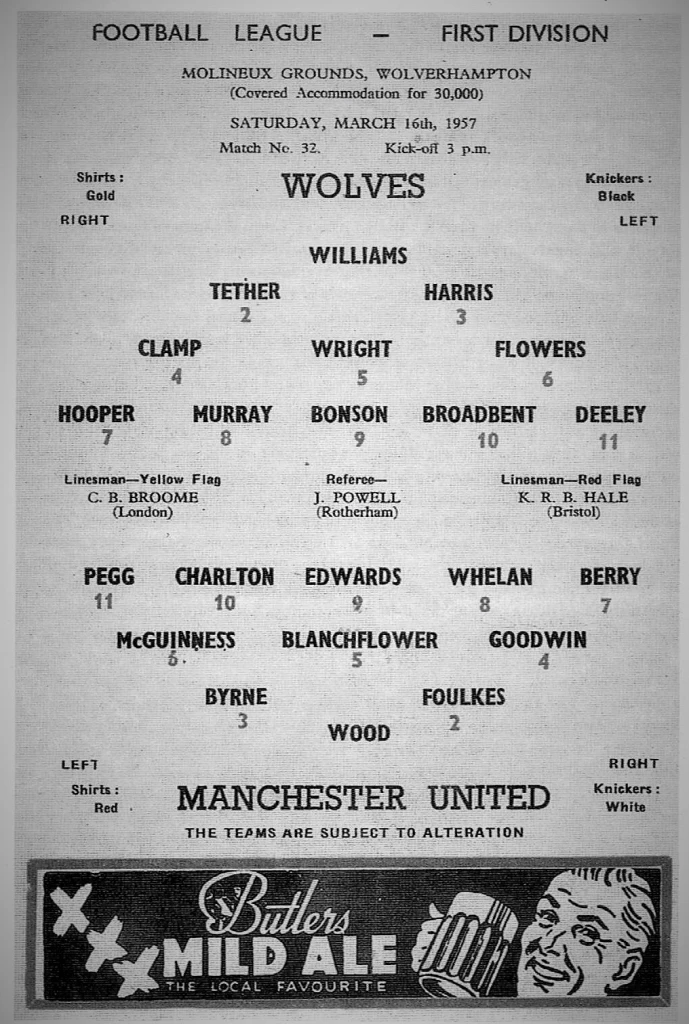

Sadly, in the season they lost the guidance of the great Stan Cullis and were relegated, 1964-65, Wolves also lost the silky skills of inside forward Peter Broadbent after fourteen years when he joined Shrewsbury Town in January 1965. Stan Cullis had signed him from Brentford in 1951, calling it one of his finest-ever signings. A magical playmaker and prolific goalscorer (scoring 145 goals in 497 appearances for Wolves), his delicate touch and crafty body swerve rivalled anything seen in continental football then. Broadbent’s style of play attracted many admirers, including the young George Best, as already mentioned. In his biography, Bestie, Joe Lovejoy said that Best told him that, while he didn’t have an individual hero growing up, he supposed that Peter Broadbent was the closest. Having watched both players from the pitch side as a boy from the mid-sixties to the early seventies, I can recall the similarities in style. However, Broadbent left Wolves just as Best was arriving on the scene for Manchester United. Broadbent won three First Division titles and an FA Cup medal with Wolves, and gained seven caps with England, including at the 1958 World Cup. After leaving Wolves in 1965, he wasn’t selected for the 1966 World Cup.

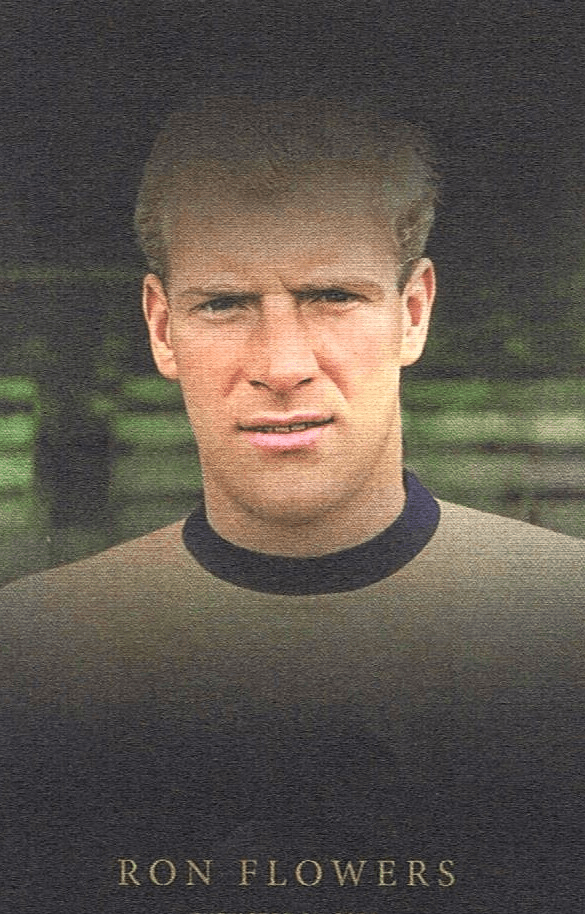

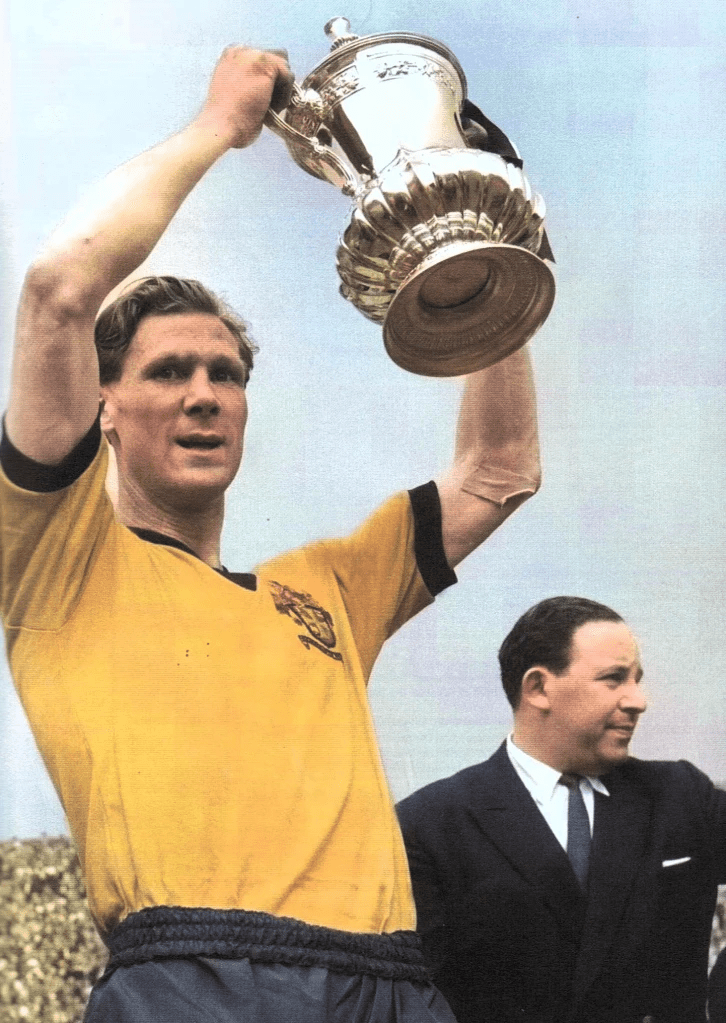

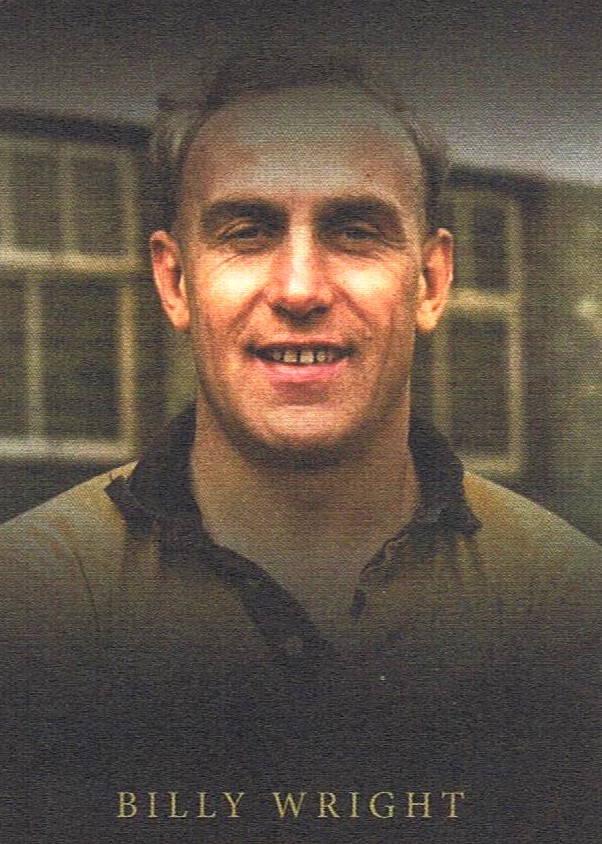

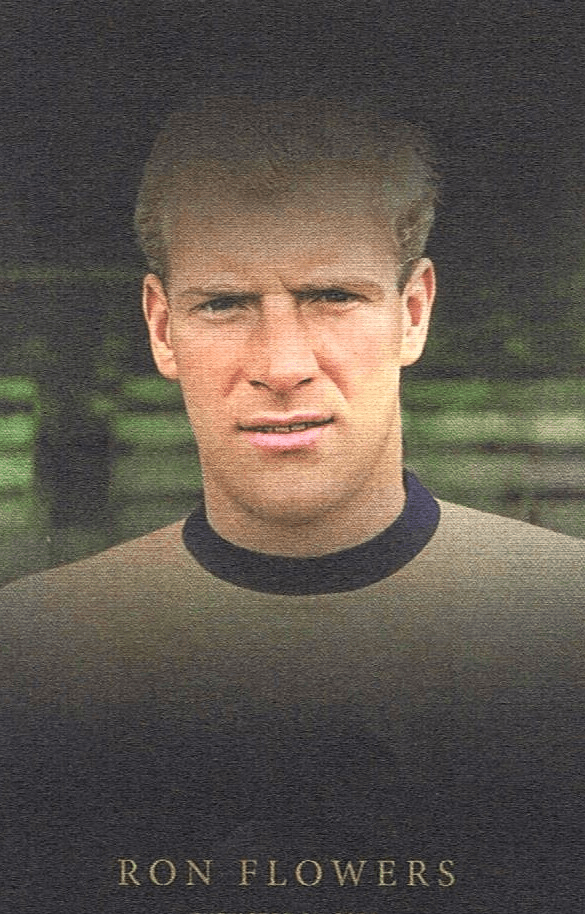

Ron Flowers (below) was selected for the England squad, but didn’t play in any of the matches in the finals, his 49th and final cap being won on 29 June 1966 against Norway in Oslo. Flowers narrowly missed playing in the final itself, as Jack Charlton caught a cold on the eve of the great game against West Germany and Alf Ramsey put him on stand-by. But Charlton had recovered in the morning and ultimately he never kicked a ball in the tournament nor received a medal. His first cap had been awarded in 1955 so the fact that his last came eleven years later is testimony to the longevity of the wonderful wing-half. Flowers was the last of the great players of the Wolves’ golden era, captaining the club to victory in the 1960 FA Cup Final, but he also left the club towards the end of the decade.

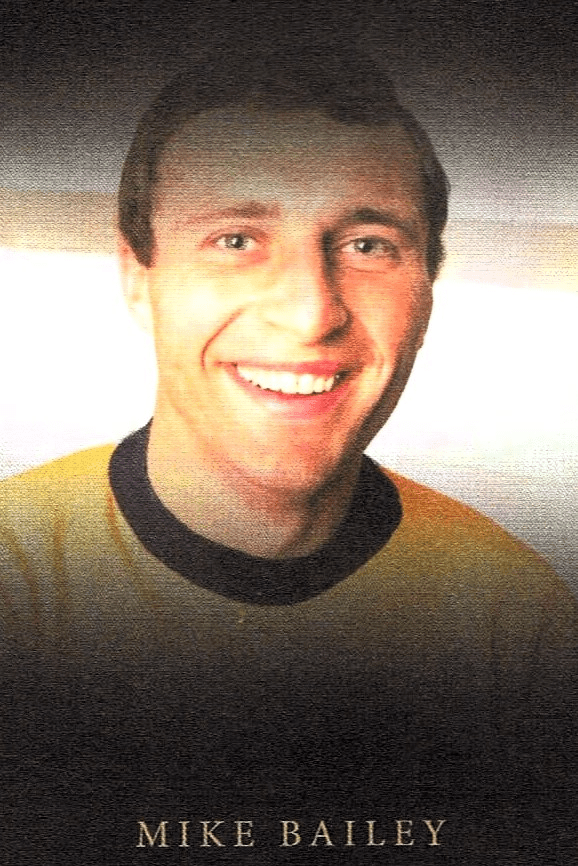

In the meantime, in August 1965, Ronnie Allen, a recently retired star player for local rivals West Bromwich Albion, joined Wolves as a coach. When Beattie resigned following a disastrous start to the team’s campaign in Division Two, Allen was appointed caretaker-manager, a decision not initially popular with the Wolves fans, given his long-term association with the Albion. However, after the turmoil of Cullis’ sacking and relegation from the top flight, the team’s confidence was at ‘rock bottom’, and the West Brom man somehow managed to revive it. In March 1966, Allen bought Mike Bailey from Charlton to stiffen the resolve of the midfield. Bailey was to have a major influence over the coming years, both as a player and captain.

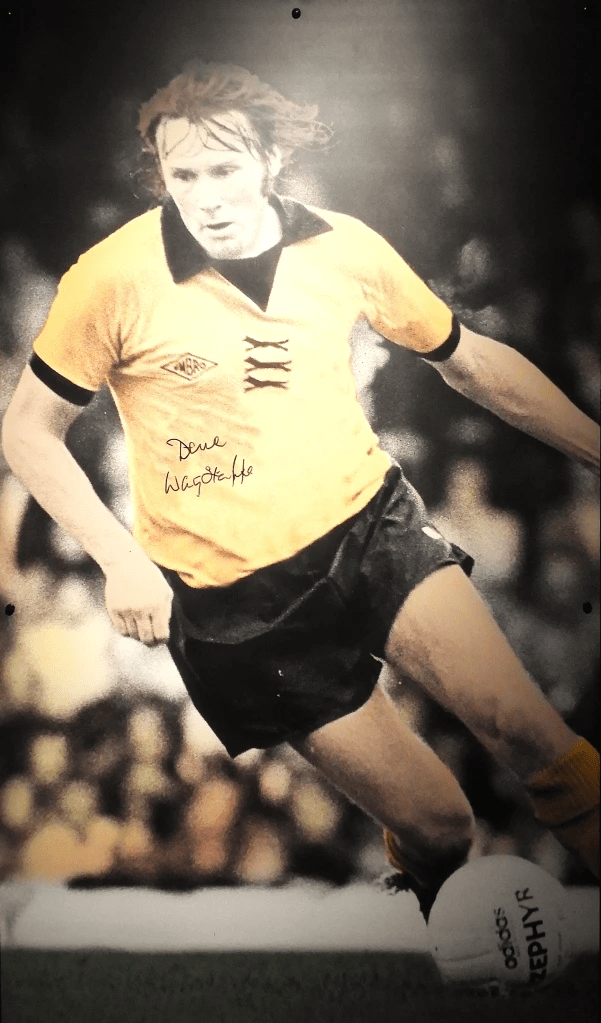

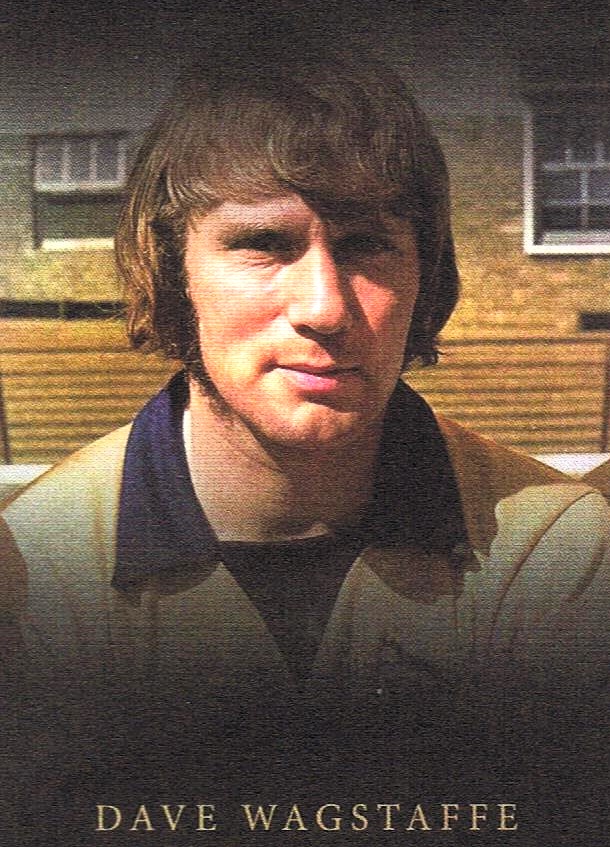

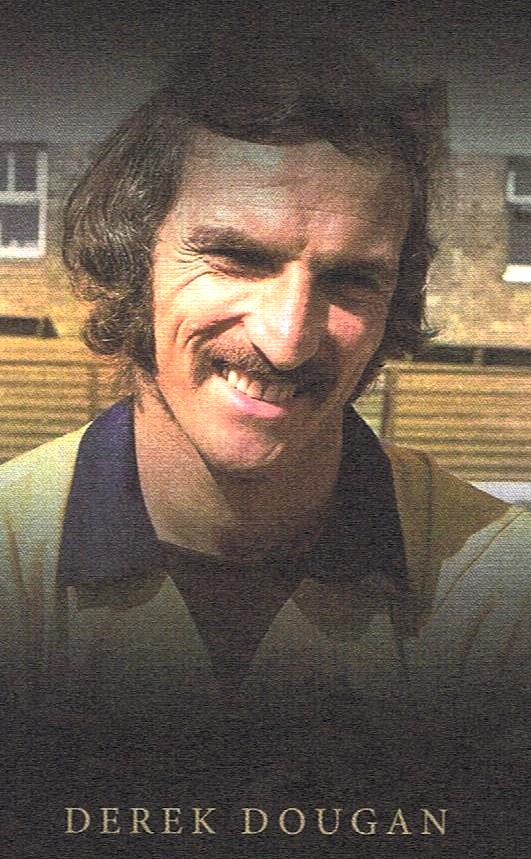

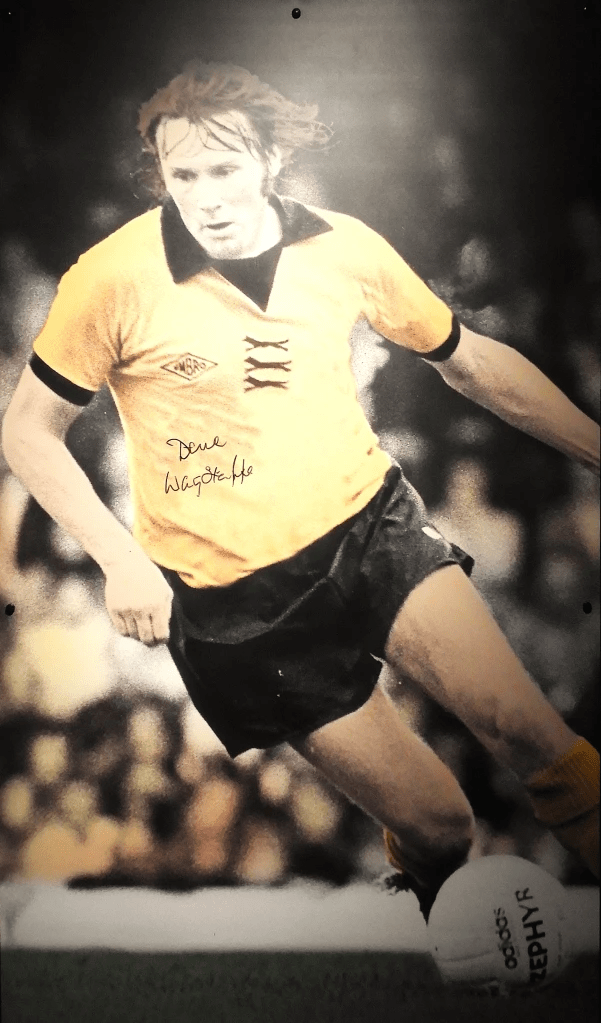

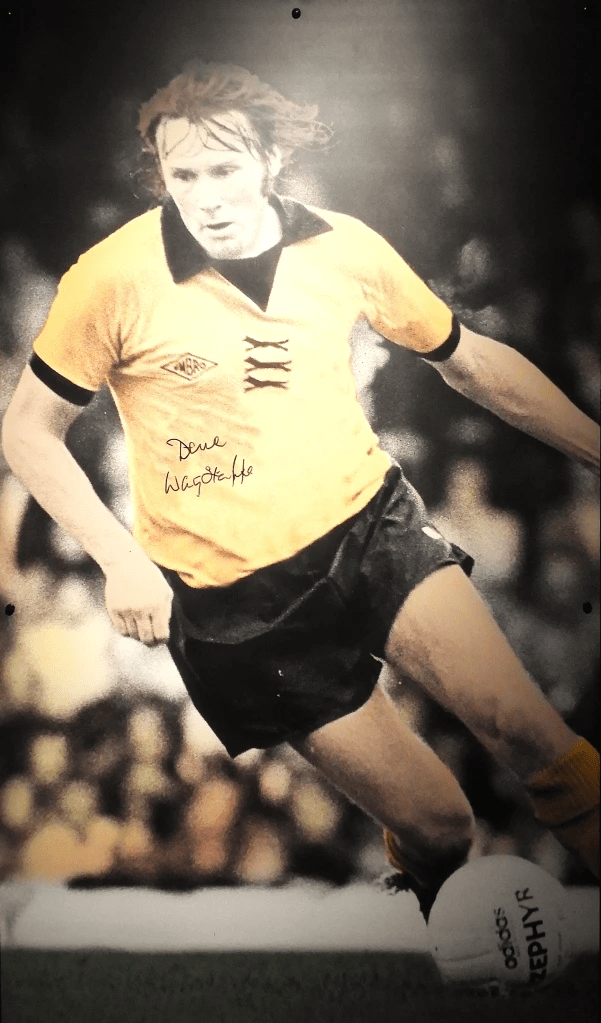

As his reward for halting the slide in his first season, in July 1966, just before the World Cup Finals, and ahead of the new season, Allen was confirmed as the full-time manager. In March 1967, he produced a stroke of genius by signing Derek Dougan from Leicester City. ‘The Doog’ knocked in nine goals in eleven games, leading a great attacking line-up of Terry Wharton, Ernie Hunt, Peter Knowles and Dave Wagstaffe (below), whom Beattie had signed. Their goals brought to an end Wolves’ two-season stay in Division Two. Wolves finished as runners-up to Coventry City, winning promotion back to the First Division.

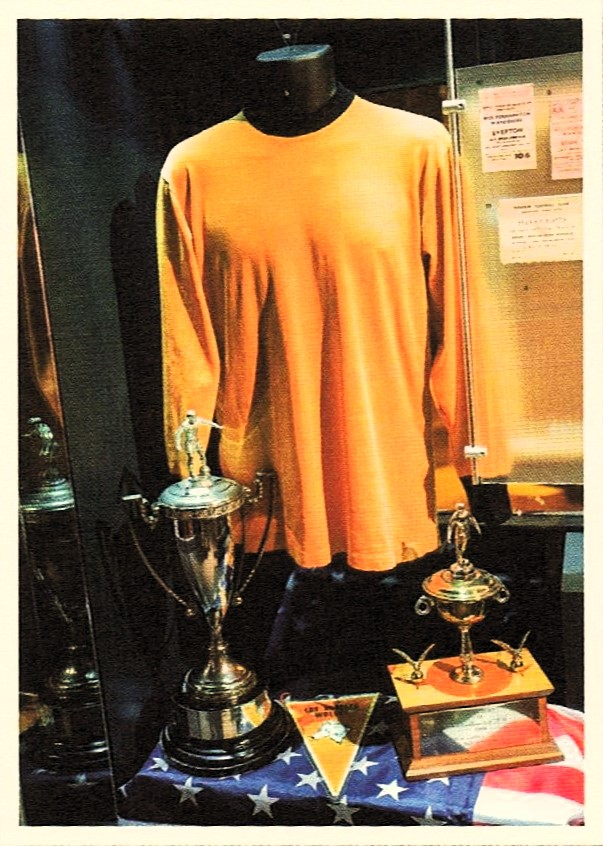

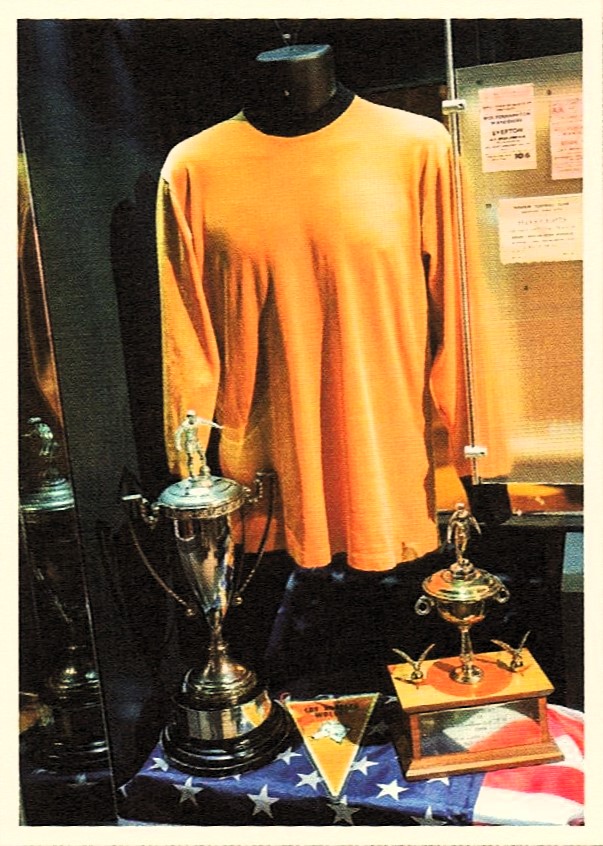

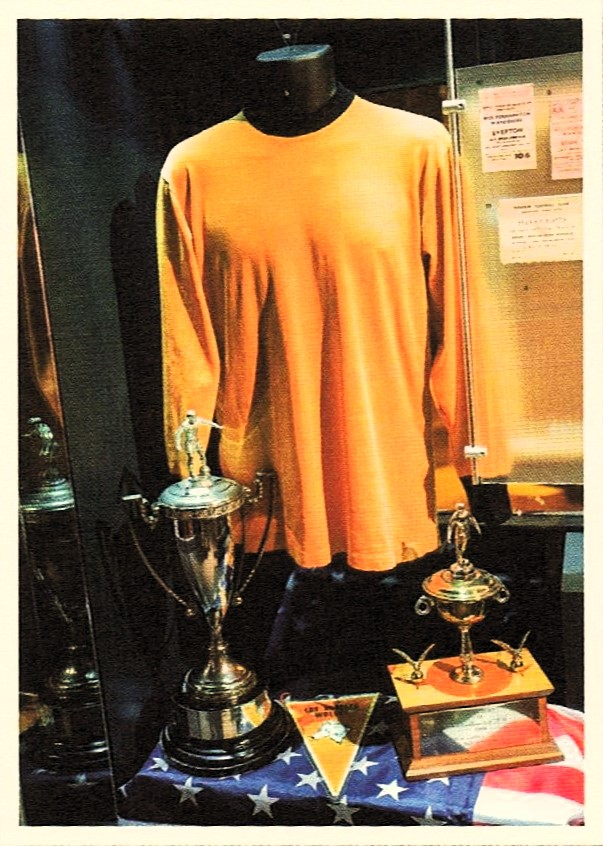

That summer they accepted an invitation to cross the Atlantic to play in the inaugural United Soccer Association League which began with twelve teams recruited from around the world. For six weeks Wolves were based in Los Angeles and from 27 May to 14 July, the Los Angeles Wolves played fourteen matches, clocking up thousands of air miles and taking in Cleveland, Washington DC and San Francisco. It was an itinerary closer to that of a rock band rather than a football team. In the final, they scored a ‘golden goal’ through Bobby Thomson to win 6-5, with the first five scored by Dougan, Knowles and a hat-trick from Burnside.

During their time in LA, Dave Wagstaffe (above) renewed a Manchester boyhood friendship with Davy Jones of The Monkees, a chart-topping pop group with their own TV series. They watched several of the team’s matches and arranged a visit to the Columbia studios in Hollywood to see the group recording an episode of their series. The story of ‘Waggy and the Monkees’ is well told in the Wolves Museum.

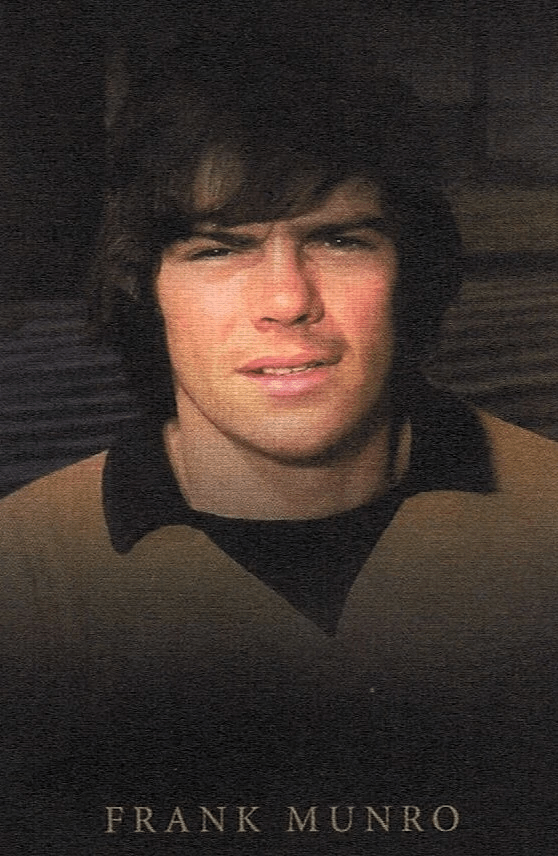

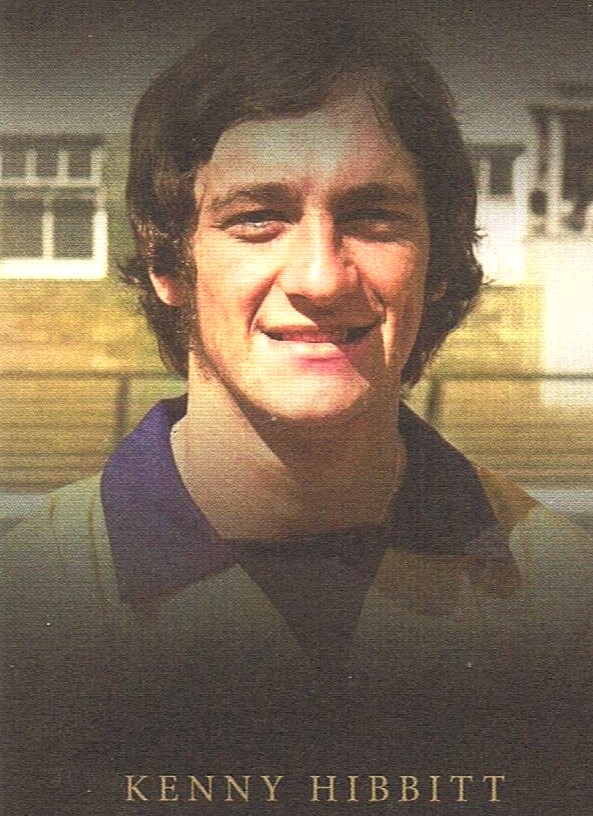

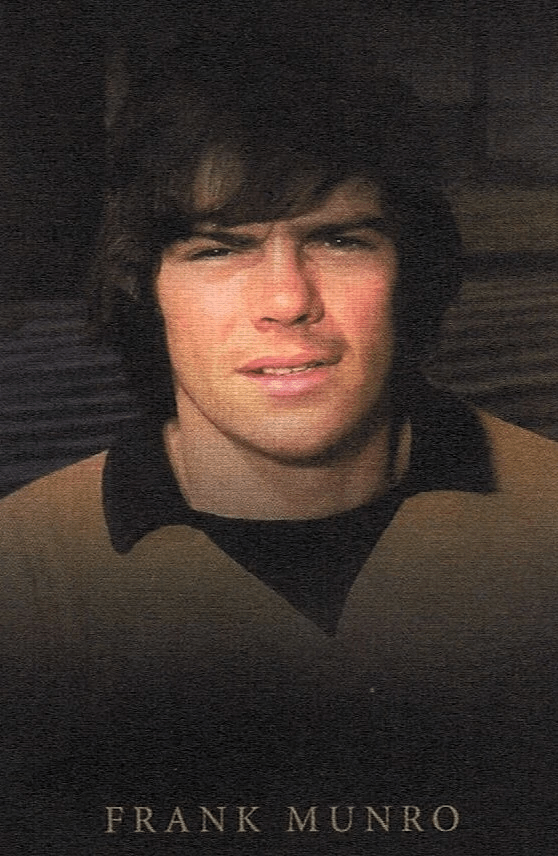

Wolves were ‘Champions of the USA’ and Ronnie Allen won the coach of the tournament award, but in the following 1967-68 season, the Wolves finished a lowly seventeenth in the First Division and Allen decided to move on. But before doing so, he made further astute signings, including those of Frank Munro (from Aberdeen) and Kenny Hibbitt.

Allen was replaced by Bill McGarry in November 1968, who added more quality signings, including Jim McCalliog from Cup-winning Sheffield Wednesday. In May 1969 Wolves returned to America to play in the the North American Soccer League International League in the guise of ‘Kansas City Spurs’. Their home ground was the Kansas City Municipal Stadium, also a Baseball stadium where The Beatles had played five years earlier when they ‘conquered the USA’. In reality, they were simply the warm-up act for the Wolves whose own ‘Beatle’, Peter Knowles, was again in the squad which topped the League and was crowned champions for a second time.

By then, the wonderful floodlit friendlies had become a thing of the past. On Wednesday 27 August 1969, Wolves unveiled their new floodlights in a League match with Brian Clough’s Derby County. Apparently, the new lights were so powerful that they caused many of the press photographers to over-expose their films. On 3 September, the floodlights lit up the first-ever floodlit game to be broadcast in colour. This was the second-round League Cup clash with Tottenham Hotspur, which Wolves won 1-0. The 1969-70 season started magnificently with Wolves winning their first four games, but then came another bombshell.

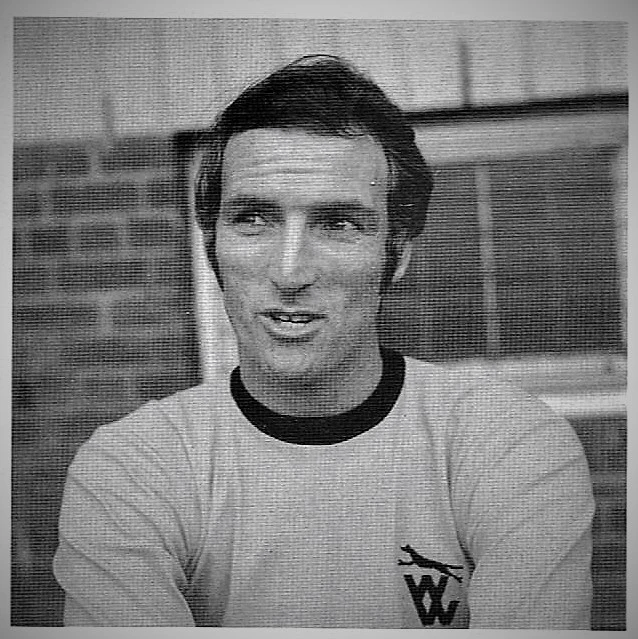

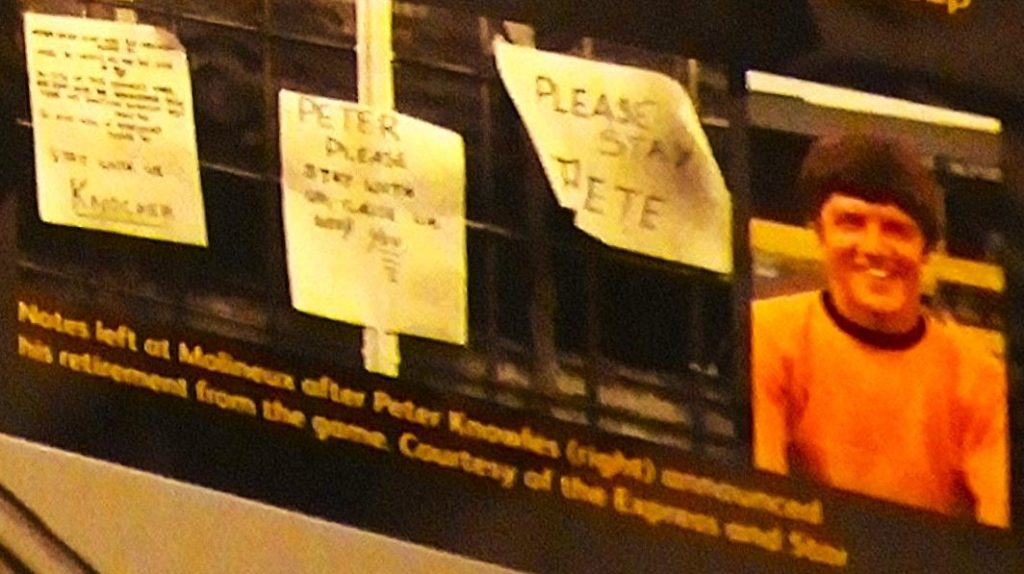

The fans’ favourite (and mine), Peter Knowles announced that he was giving up football at the age of twenty-four, to devote the rest of his life to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. In his programme notes for Knowles’ last game against Nottingham Forest, McGarry wrote that he was still hoping that Peter would return for training the next Monday to find his kit laid out for him. The Club held onto his registration for several seasons, but Peter never returned, except once, for a final testimonial at the end of that hiatus. Fortunately, in 1967 Wolves had been joined by another future talented goalscorer in John Richards, although a very different player to Knowles.

Peter ‘knocker’ Knowles had seemed destined to become a great footballer, perhaps rivalling Peter Broadbent or even George Best. A Yorkshireman, he signed from Wolves’ nursery team, Wath Wanderers in 1962, as a seventeen-year-old, making his first-team debut in October 1963, a year after becoming professional, scoring four times in fourteen outings. By the end of the following season, he had established himself as a regular first-team member and although injuries restricted his appearances, he still managed to score eighty-four goals in 188 games. Not only was he wonderfully skilled, but he also revealed a special temperament in how he played the game. Perhaps it was this that also gave him the moral fortitude to turn his back forever on the sport he loved.

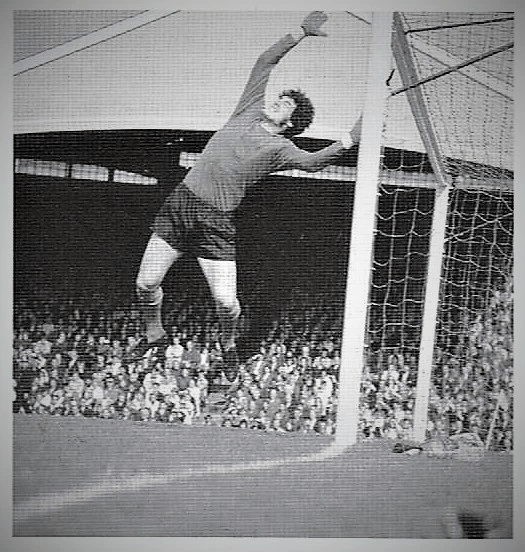

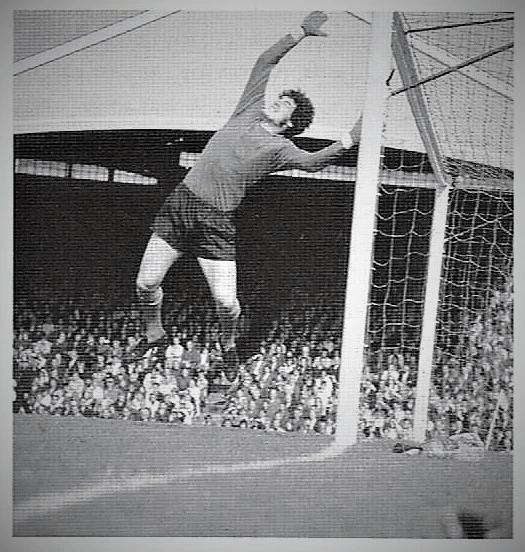

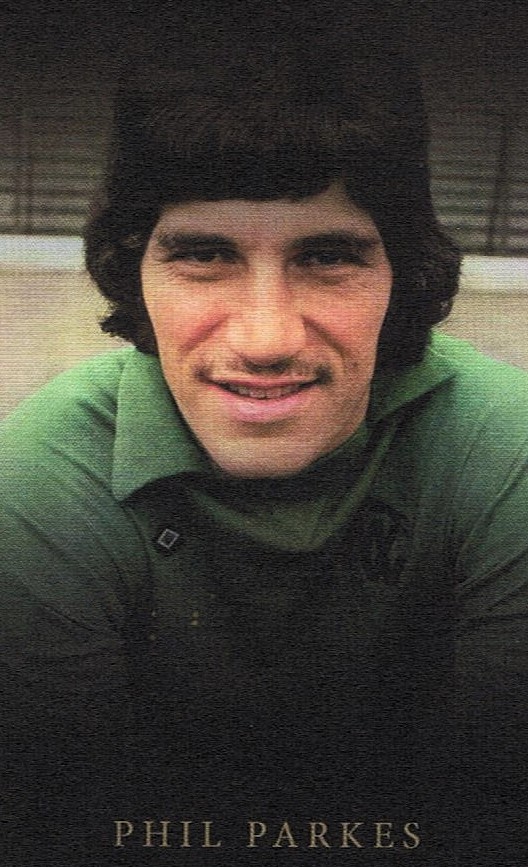

Knowles was capped four times for England’s under-23 team, and would surely have become a full international in the following decade. The disappointment of the fans at his sudden departure is therefore understandable, but they also showed respect for his decision. The season as a whole finished disappointingly with Wolves losing eight of their final thirteen games and drawing the other five, taking only five points from a possible twenty-six. The 1969-70 season ended with a thirteenth place finish. Another emerging star of the 1960s was goalkeeper Phil ‘Lofty’ Parkes, who made his debut in November 1966 and would go in the next decade to make 127 consecutive league appearances, 170 in all competitions, a Wolves record.

The Seventies’ Icons:

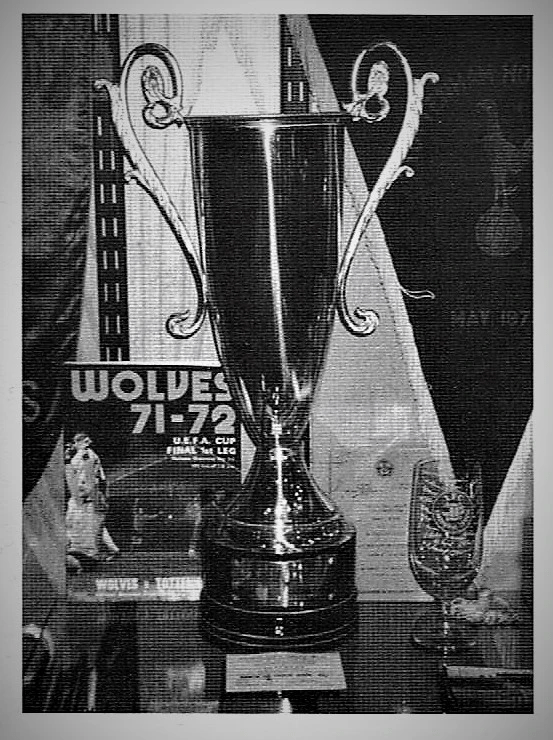

The Seventies began with two impressive seasons, including the next ‘chapter’ in Wolves’ European narrative which came in 1971-72 when they qualified, as fourth-best league finishers, for the UEFA Cup, renamed from the Inter-City Fairs Cup. After their mixed experience in the Anglo-Italian Cup in 1969-70 and the Texaco Cup in 1970-71 (against Scottish and Irish League teams, which they won, beating Heart of Midlothian over two legs), the Wolves fans looked forward to being back in European Competition proper.

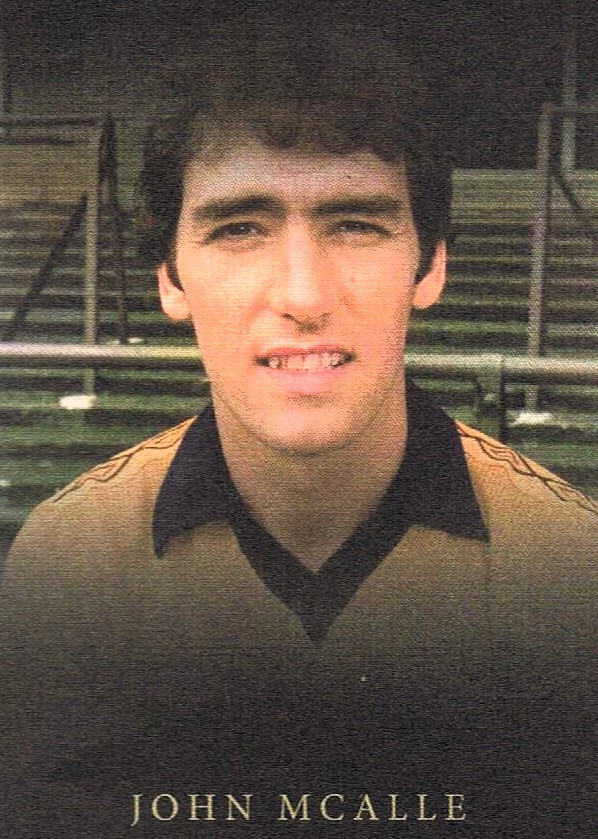

The 1971-72 season was iconic, as Wolves competed in Europe for the first time since 1960-61. In the UEFA competition Wolves took on and beat some of Europe’s most illustrious clubs, beginning with a Portuguese team from the university city of Coimbra. They had qualified by finishing fifth in Portugal’s First Division and had earned a reputation for being hard to beat in knock-out competition; no team had managed to score more than one goal against them over two legs in a European tie. However, in the first leg at Molineux in mid-September, the Wolves managed to smash their visitors’ proud record by beating them 3-0 with goals from John McAlle (pictured below), John Richards and Derek Dougan. In the away leg, Wolves again won by three goals, 4-1, including a hat-trick from Dougan and another rare goal from McAlle. In the next round, Wolves won by the same aggregate of 7-1 against FC Den Haag of the Netherlands, with a 4-0 victory at Molineux on 3 November, with the Dutch scoring three of them – own goals!

Wolves went behind the iron curtain to beat East German team Carl Zeiss Jena in the third round, in a match played in the snow, before meeting Juventus in the Quarter Final. They then went to Italy, travelling with Juventus, Leeds United and Wales legend John Charles as an ambassador who sat on the bench with Bill McGarry and his assistant, Sammy Chung. This turned out to be a tactical masterstroke by McGarry, as Wolves drew in Italy and went on to beat the Italian giants 3-2 on aggregate, 2-1 at Molineux, with goals from Derek Dougan and Danny Hegan.

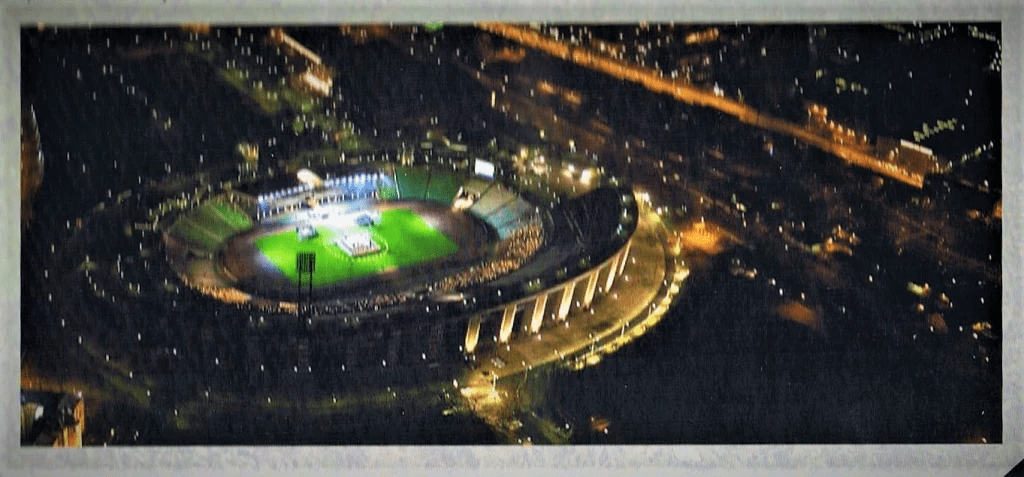

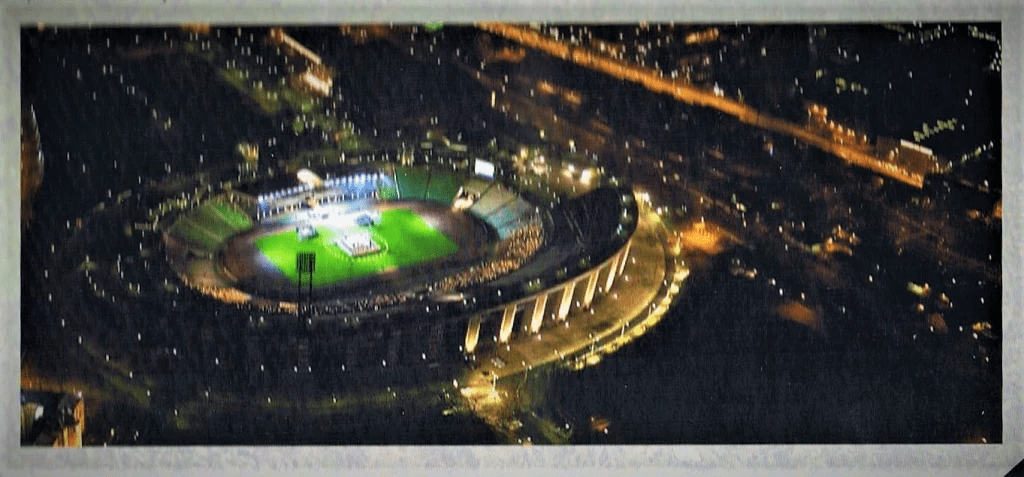

In the Semi-final they faced even tougher opponents in the Hungarian aces Ferencváros and their great centre-forward Flórián Albert, winner of the Ballon d’Or Player of the Year Award in 1967. The first leg was played on a beautiful Budapest Spring afternoon in April 1972, in the Népstadion where they had last met Honvéd. The attendance was 44,763 and kick-off was at 5.30 p.m. Wolves managed to maintain their excellent away form in the competition, drawing a hard-fought game, 2-2. They showed a determined effort after their brilliant young striker John Richards had put them ahead after nineteen minutes. Derek Dougan cleverly drew the defenders away before back-healing the ball back to Richards, who didn’t miss.

Ferencváros came back strongly, however, scoring two in eight minutes. István Szőke got the first on the half-hour from the penalty spot, and then the Magyars took a two-goal lead. Flórián Albert netted from open play, shooting past Phil Parkes following Szőke’s tempting cross, making it 2-1 to ‘Fradi’ at half-time. At seventy-four minutes, the home team was awarded another penalty, but this time Parkes magnificently saved Szőke’s shot with his left foot. The Budapest team went close again when Kű headed just over. The Wolves then rallied and won a corner. Dave Wagstaffe swung the ball in and Frank Munro was perfectly placed to nod home the equaliser. After that, Kenny Hibbitt and Jimmy McCalliog smacked in powerful shots, but they didn’t result in a winning goal. The Wolves had almost three times the number of efforts on goal as the home team but the two sides went into the return leg on equal terms. The two teams in Budapest were as follows:

Ferencváros: Vörös; Novák, Pancsícs; Megyesi, Vépi, Bálint; Sőke, Bránkovics, Albert (pictured below), Kű, Múcha (Rákósi). Subs: Rákósi, Fusi, Hórváth, Géczi.

Wolves: Parkes; Shaw, Taylor; Hegan, Munro, McAlle; McCalliog, Hibbitt, Richards, Dougan, Wagstaffe. Subs: Arnold, Parkin, Daley, Sunderland, Eastoe.

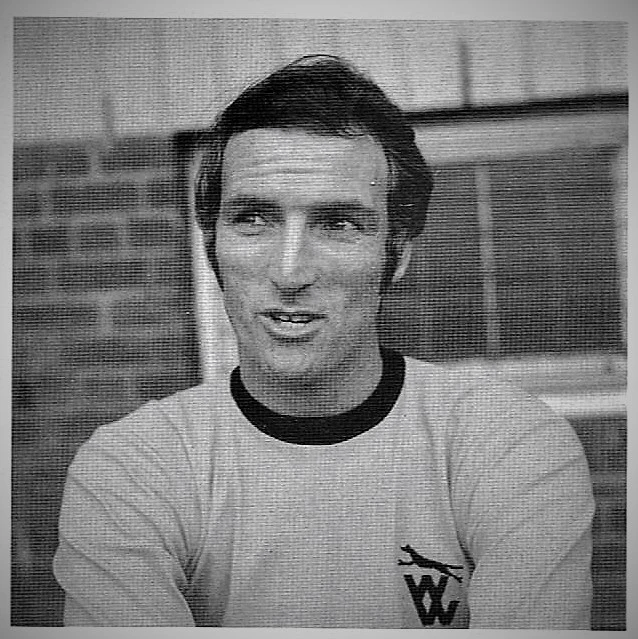

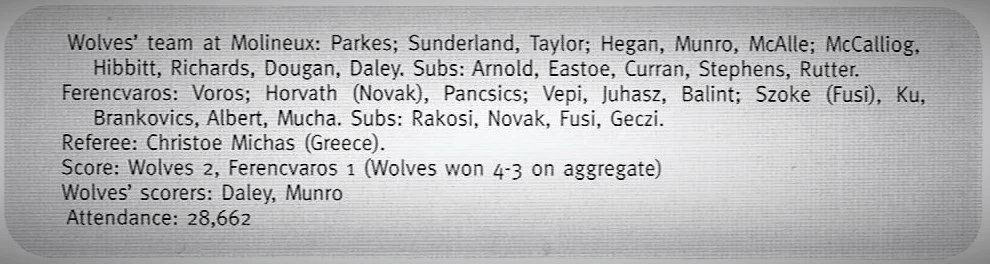

The second leg was held at Molineux a fortnight later on 19th April 1972 in front of a disappointingly small crowd (for a European semi-final) of just over twenty-eight thousand. The Wolves were determined not to lose this semi-final as they had their last in Europe, against Glasgow Rangers in 1961. Phil Parkes was once again outstanding, Alan Sunderland came in at right back for the suspended Shaw, and Steve Daley, aged eighteen, made his European debut in place of the also-suspended Dave Wagstaffe. New boy Daley’s dream came true when he put Wolverhampton ahead in the first minute. Goalkeeper Vörös missed Sunderland’s high floating cross, the ball falling to Daley. Just before half-time, up jumped Frank Munro (above) as he had in the away leg to put the home team 2-0 up. Lájos Kű pulled a goal back for ‘Fradi’ two minutes after the interval and then Phil Parkes saved another penalty from Szőke with his leg. It was a very entertaining game, worthy of a final, in which Daley and Hibbitt went close, Dougan hit the bar and Sunderland sent in a thirty-yard screamer before Taylor cleared a József Múcha effort off the line. Wolves won a close match 2-1, and the tie 4-3 on aggregate.

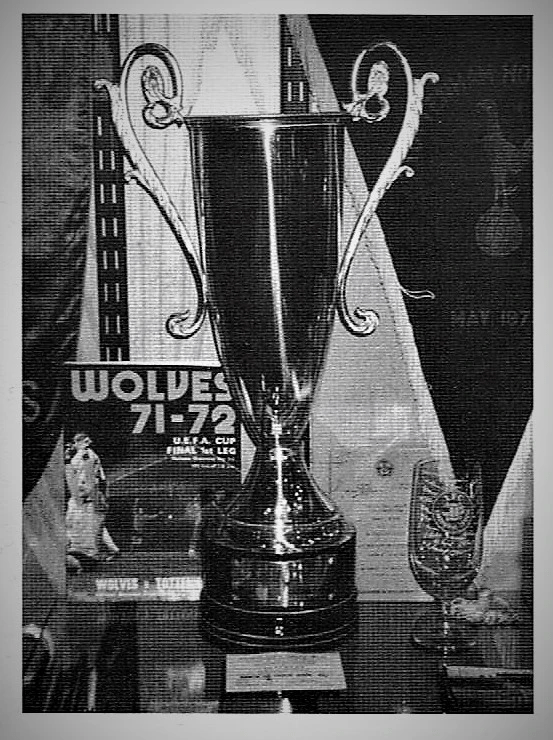

Sixty-four clubs had initially set out to contest the competition, so it was testimony to the strength of English football that two First Division clubs reached the final. Unfortunately for Wolves, the other team was Tottenham Hotspur, one of their cup bogey teams. Wolves lost their home leg 2-1, Martin Chivers scoring both goals for the visitors, and the second leg was drawn 1-1, so the cup went to Spurs. Wolves should have won their first European trophy, and the 3-2 aggregate score over the two legs was not a fair reflection of the games, according to many media reports the day after the match at White Hart Lane, where Wolves gave a brilliant performance. Dave Wagstaffe’s equalising goal in the forty-first minute was one of the greatest goals ever scored by a man in the golden shirt. It was said by those present to be better than the one he scored in the 5-1 thrashing of Arsenal in a snowstorm at Molineux the previous November which had won the BBC’s Goal of the Month competition.

Although the Wanderers’ 1971-72 European campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, it seems curious that it is not remembered at least as favourably as the floodlit friendly matches of 1953-54 against Honved in the club’s annals. In many ways, the Wolves’ victory against Ferencváros in the semi-final of the UEFA Cup, an official competition, can be seen as the pinnacle of the Old Golds’ distinguished European history. Their team that season was perhaps as great as the one that faced Honvéd in 1954, especially in its forward line, though Billy Wright’s half-back line will always be remembered as the finest ever to take the field both for his club and for England. I am too young to have seen the class of ’54, except on video, and the gap between the two periods is too great to make a reasonable comparison. In what was their first European Cup final, the fact that their opponents were Tottenham, though a star-studded team themselves, made it seem less of a European final. The semi-final was a far more fitting final, especially given the star-studded nature of the Ferencváros team which included the ‘Ballon d’Or’ winning Florián Albert (below).

The class of 1971-72 are still the only Wolves side ever to get to a European Final, and, together with Spurs, the first-ever English team in the UEFA Cup. This was also achieved without their inspirational skipper and lynchpin Mike Bailey, who was injured for the last three ties and only played in the second leg of the final, though Jim McCalliog ably replaced him as skipper.

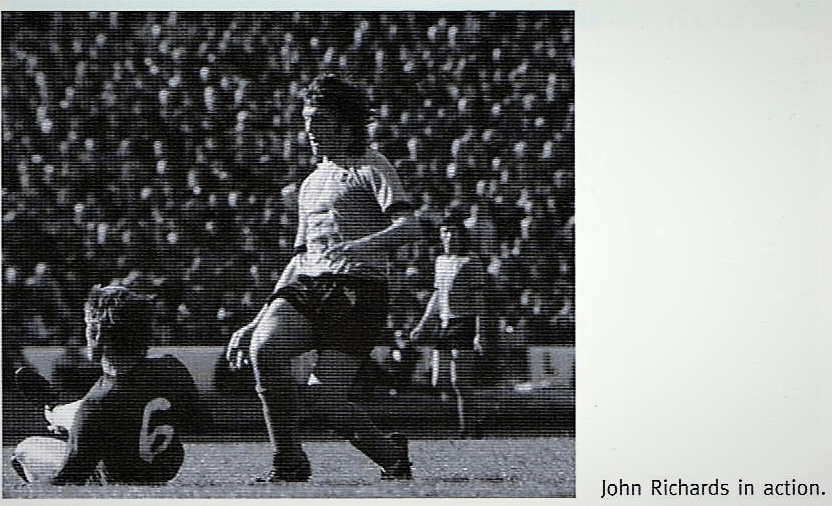

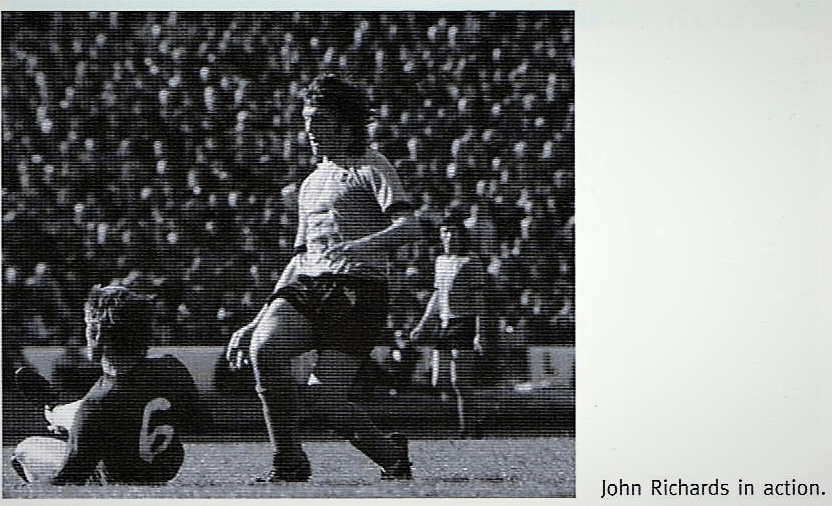

In their first season together, 1971-72, the Dougan-Richards combination scored forty goals in the League and UEFA Cup. I remember watching them in action at the Hawthorns, against West Bromwich Albion, and at Molineux. The duo scored a total of 125 goals in 127 games together in two-and-a-half seasons.

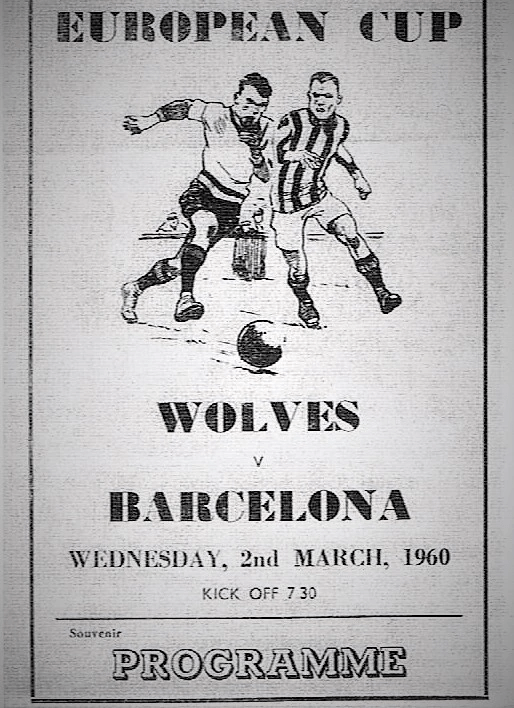

In 1972-73, Wolves finished fifth in the League and were semi-finalists in both domestic cups. Their league position earned them another place in the UEFA Cup, at the expense of Arsenal, who despite finishing as runners-up in the League, were not allowed to compete because of a rule which only permitted one team per city to enter what had been the Inter-city Fairs Cup. Tottenham finished eighth, but their League Cup win meant that they took precedence over their North London rivals. So Wolves found themselves back in Europe, but they made a departure in the second round of the UEFA Cup when they met the East Germans, Lokomotiv Leipzig, in October 1973. In the first leg, in Leipzig, the Wolves were without their midfield king-pin Mike Bailey and strikers John Richards and Dave Wagstaffe. But no one in the Wolves camp could quite believe the result, a 3-0 defeat, their first away defeat on their UEFA Cup travels. Not since they met Barcelona in the Quarter-final of the European Champions Cup in 1960 had a side put three past Wolves in a competitive European game.

The Old Gold tried to rally and rescue the tie in the second leg at Molineux, in a match that the fans who went to see it felt privileged to witness. They had scored the four goals they needed by the 83rd minute, but Lokomotiv scored the all-important away goal in the 72nd minute. So the tie finished 4-4 on aggregate, but the Wolves went out on the away goals rule, which stipulated that, in the event of scores finishing level after both legs, away goals would count double.

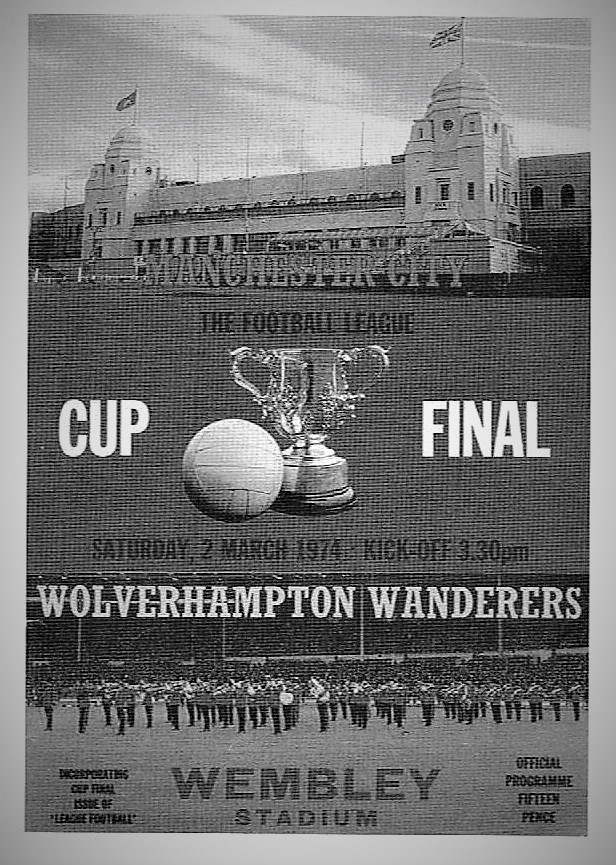

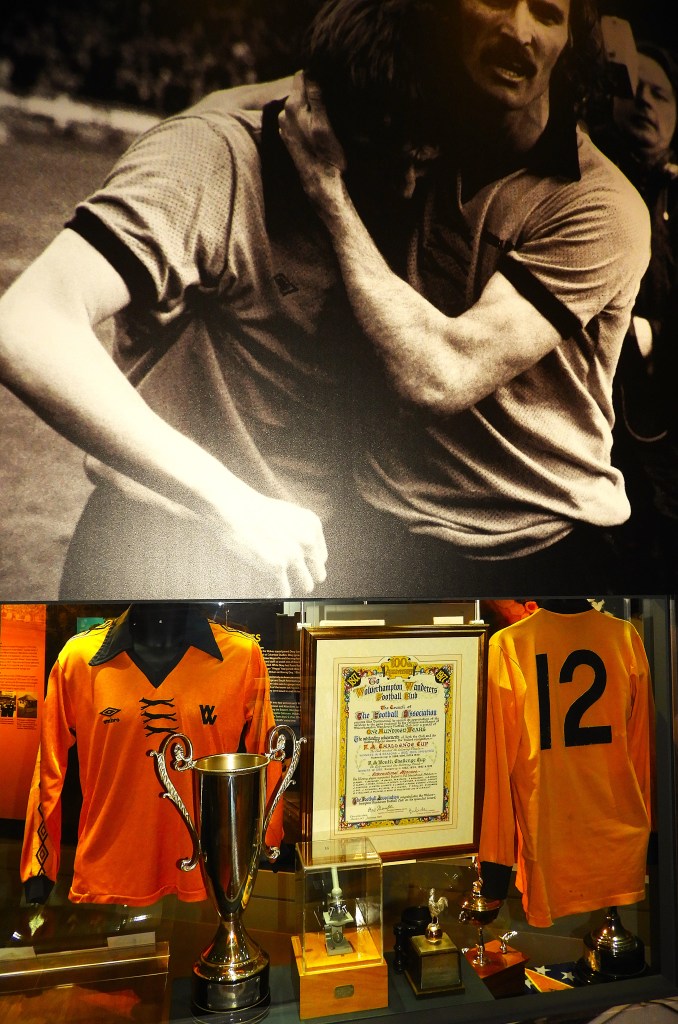

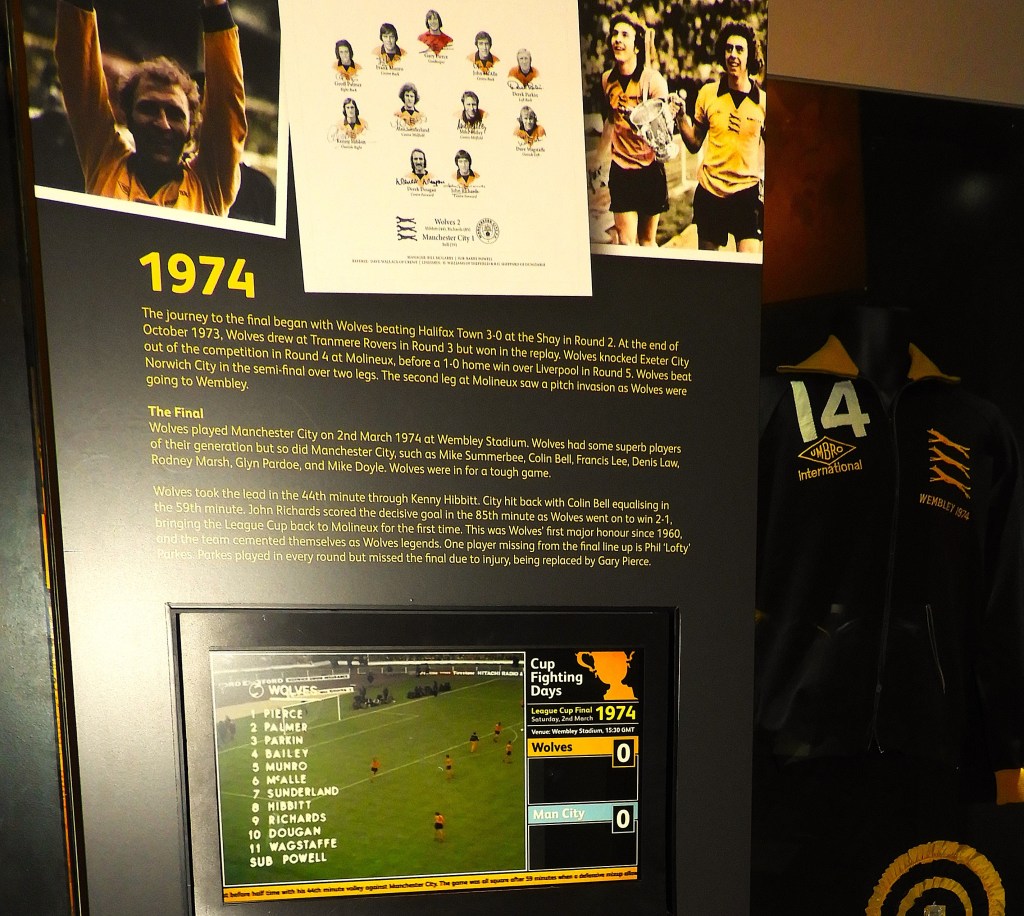

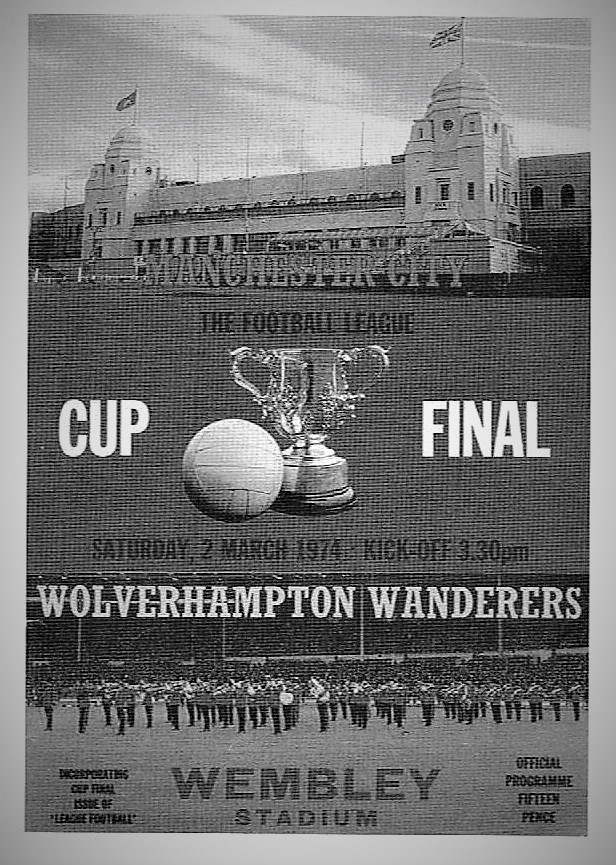

It was some compensation that in March 1974 Wolves won the League Cup. They had beaten Liverpool in the fifth round when the 1973 Oil Crisis had threatened kick-off times in the League Cup from October when the oil-producing countries began an embargo on exports to countries perceived to be supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War, including the UK. This threatened the use of floodlights as there was a concern that the power stations would simply not be able to operate. In the event, Wolves were able to beat Norwich City in the semi-final over two legs and faced Manchester City in the final at Wembley in front of 97,886 fans. Both finalists were in mid-table positions at this time, but Man City had one of the best forward lines in the business from Mike Summerbee on the right, through Colin Bell, Francis Lee, Denis Law and Rodney Marsh. Besides, City had been there before, and recently, beating West Brom a few seasons previously, a match for which I was fortunate to get a ticket.

The Wolves also had an impressive forward line with its striking partnership of Derek Dougan and John Richards, flanked by Kenny Hibbitt on the right and Dave Wagstaffe on the left, with Steve Daley assisting from midfield. But the players were nervous before the game as only Derek Dougan had been to a Wembley final before. Nevertheless, Wolves took the lead through Hibbitt just before half-time. Then Colin Bell equalised for City on the hour. ‘King’ John Richards sealed the win five minutes from time to bring the trophy to Molineux for the first time since the competition began in 1966. Most importantly, Wolves qualified for another season in the UEFA Cup. In 2024 Wolves celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of that victory by inviting surviving players to Molineux, where they were introduced to the crowd at a Premier League game.

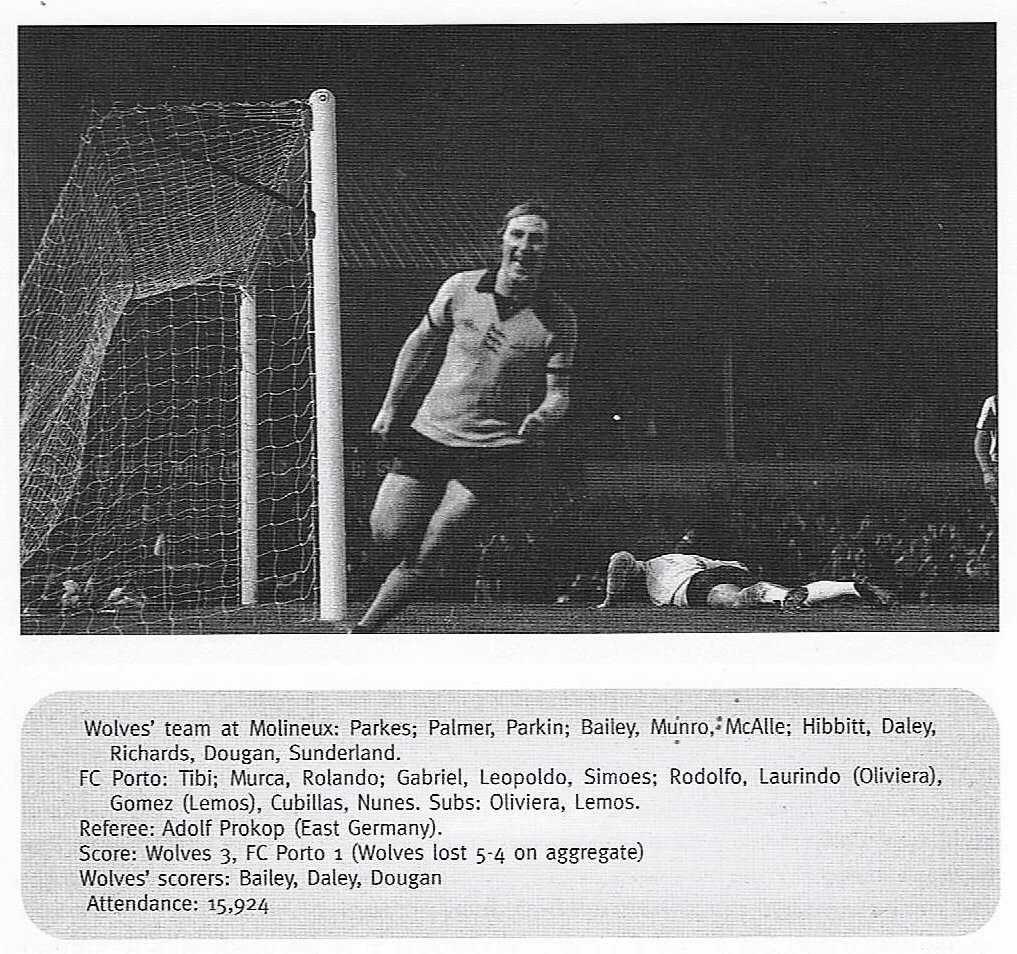

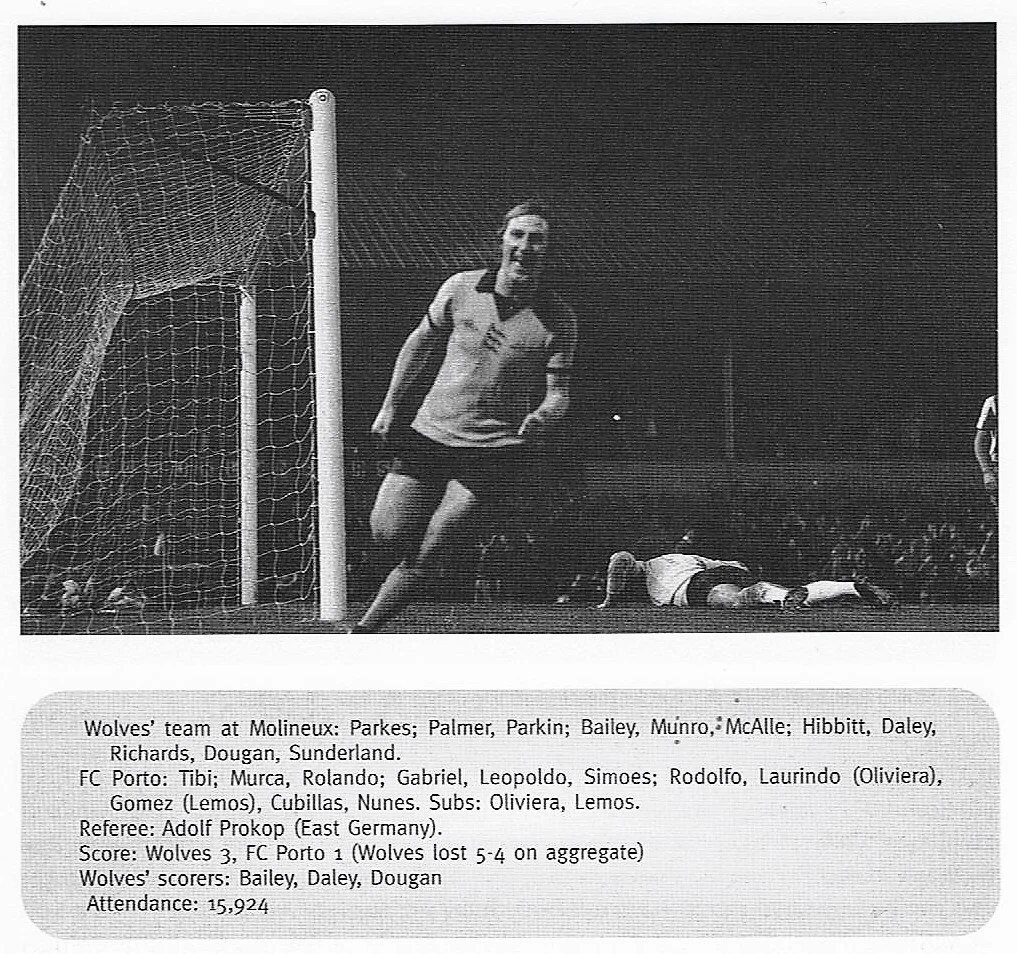

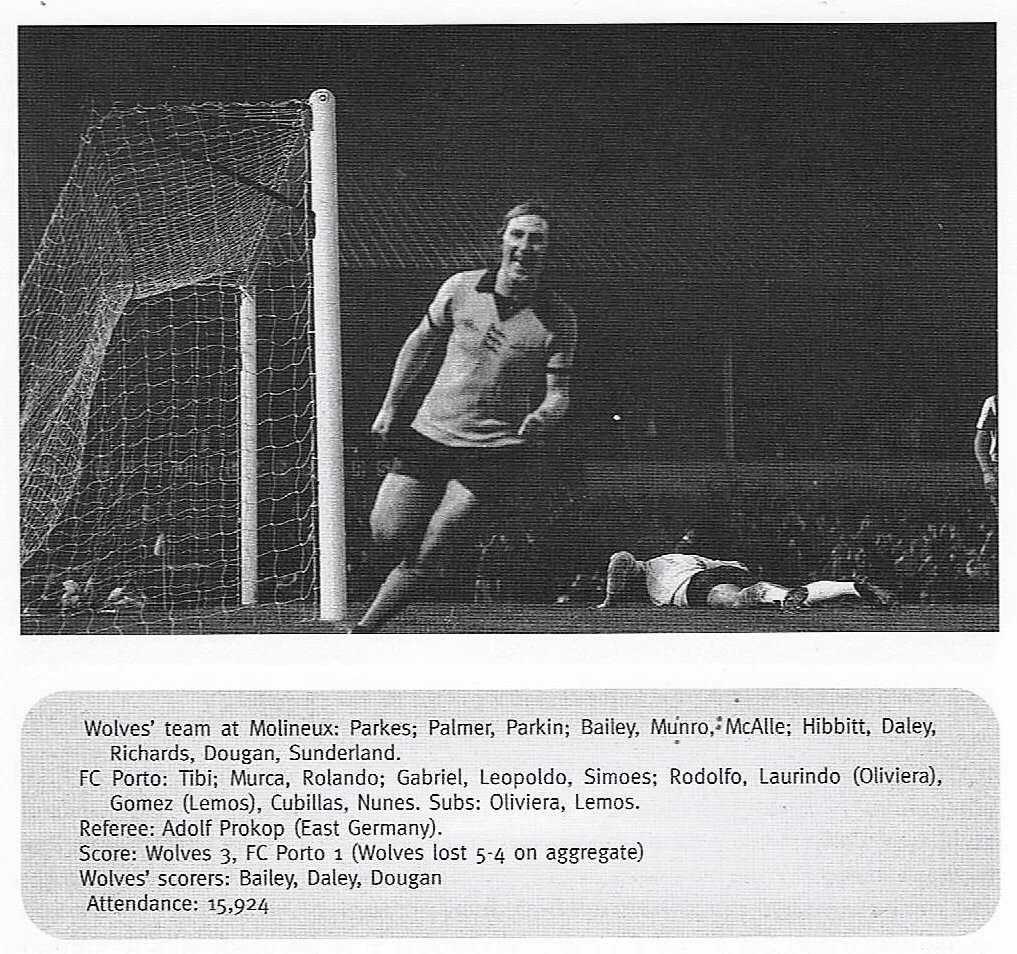

But the hobbling Richards didn’t play again that season, while the ageing ‘Doog’ was mostly restricted to the substitutes’ bench. Dougan played his last six full games in 1974-75, two of them in the UEFA Cup when Wolves went ‘one worse’ than their performances in previous seasons by losing in the first round to FC Porto, to a team packed with world stars, including the Brazilian World Cup star, Flavio. The first leg was played in Oporto on Wednesday 18 September. John Richards’ hamstring injury kept him out of the tie and Dave Wagstaffe was also missing. Wolves lost by a humiliating scoreline of 4-1 and trying to turn around a three-goal deficit seemed impossible given Wolves’ recent performances in the competition.

But on the 2nd of October, the true Molineux faithful were treated to another night of fully committed football. The atmosphere was once again electric and the floodlights seemed brighter than ever. The score was 1-1 at the interval following a goal from Bailey, and on the resumption, it only took the snarling Wolves only a minute to score a second when Alan Sunderland crossed the ball, Dougan rose high to head it on and Steve Daley nodded it home. In the photograph below, he is shown celebrating after scoring. In the 79th minute, Wolves won a free-kick which Derek Parkin floated into the danger area. Dougan rose high to meet the ball cleanly, and it was 3-1 on the night. What followed was a display of all-out attacking football from Wolves, but they couldn’t quite get the fourth goal. The season ended in a mid-table finish for the Wolves who were knocked out in their first-round matches in both domestic cups. Derek Dougan hung up his boots after a career spanning twenty years.

The following season the club was surprisingly relegated to the second division after Dave Wagstaffe was sold to Blackburn Rovers early in 1976. In May, Bill McGarry lost his job, with his assistant trainer Sammy Chung succeeding him. Chung turned things around by winning promotion back to the top flight at their first attempt in 1977 and winning the second division title for the first time since Major Buckley.

Eighties & Nineties – The Fall & Rise of the ‘Mighty Wolves’:

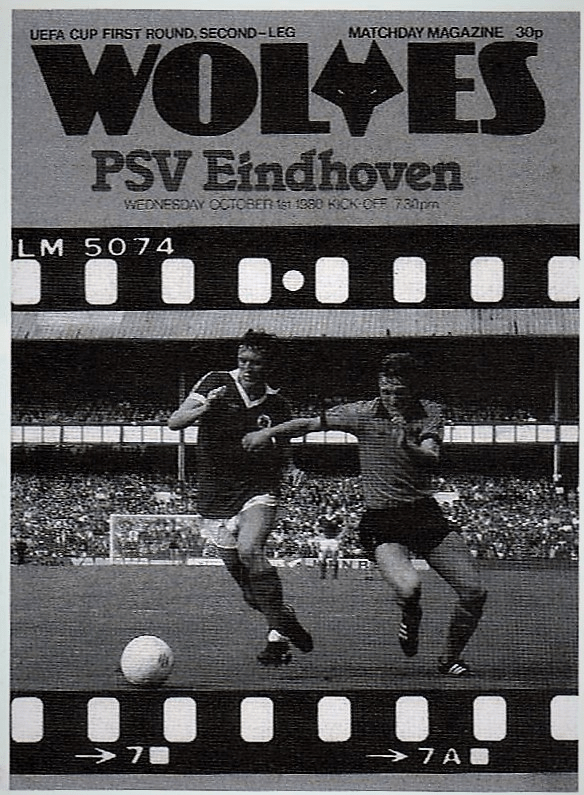

Fortunes revived somewhat In the 1979/80 season when Wolves beat Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest in the League Cup Final at Wembley with Andy Gray scoring the decisive single goal. Forest had won the European Cup in 1979 and went on to retain it in 1980. Emlyn Hughes (below) proudly lifted the only trophy that had hitherto eluded him in his long and distinguished career at Liverpool. Wolves also finished the season in a creditable sixth place, the last time they finished in the top six of Division One. So it was that, at the beginning of the 1980/81 season, the Wolves found themselves on another, fourth UEFA Cup adventure.

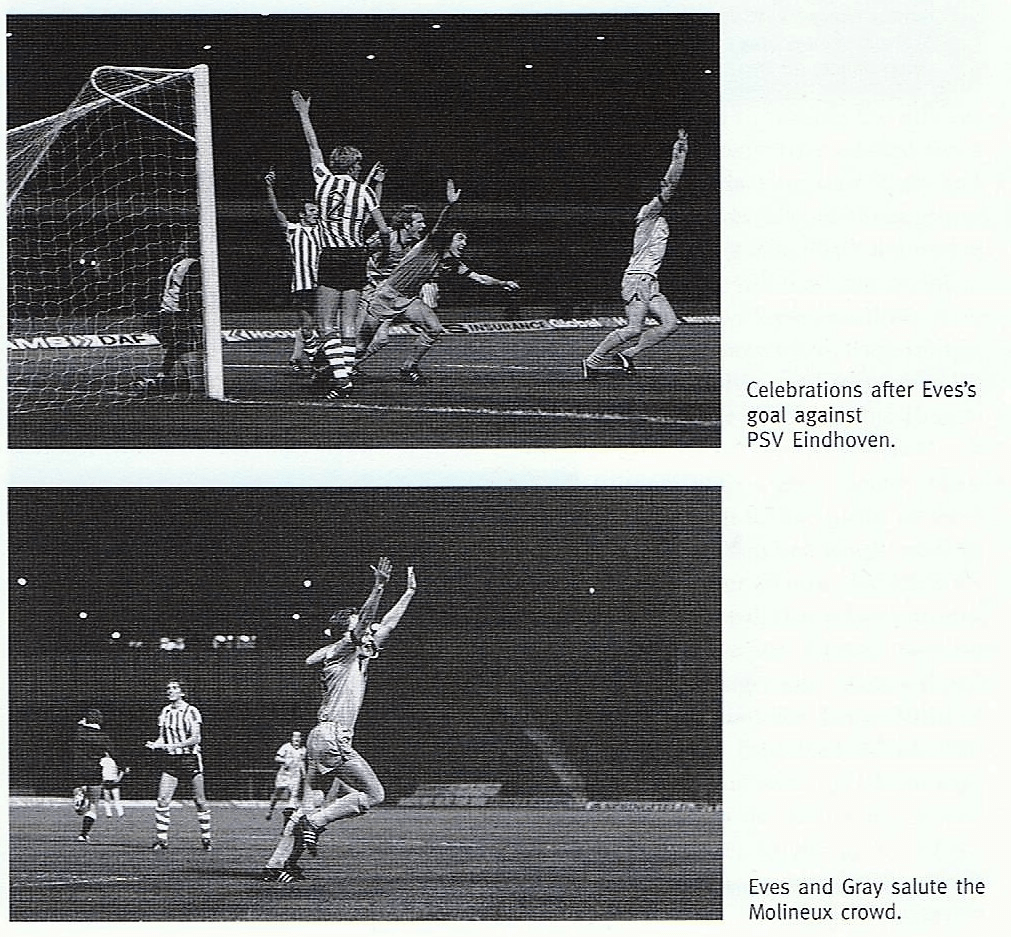

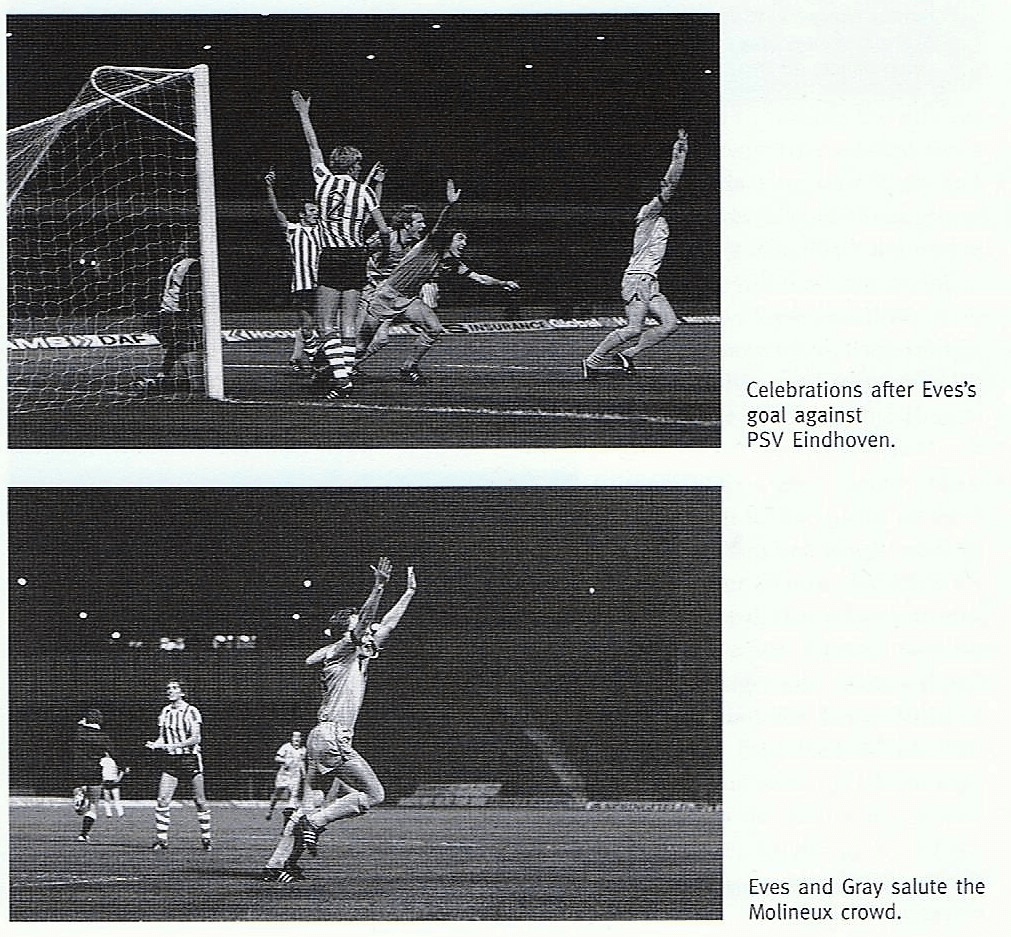

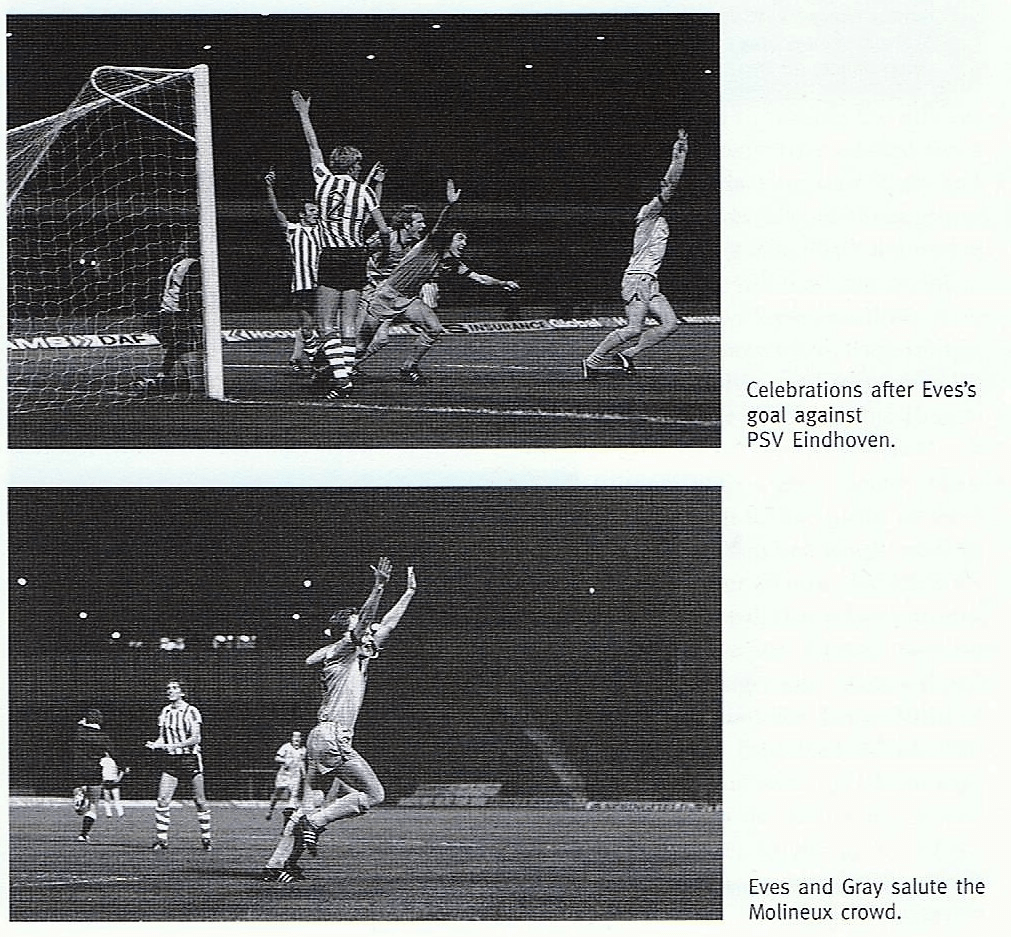

But Dutch masters PSV Eindhoven all but put an end to the Wolves’ high hopes in mid-September by beating them 3-1 in Holland. That deficit was always going to be difficult to reverse, even at Molineux, where such things had happened before in European matches. Richards and Gray did everything they could to get the ball in the net, despite the fouls perpetrated against them. The Dutch ‘keeper stopped everything that came his way, but it looked as if the Wolves might just come out on top. Then, in the 38th minute, the lights suddenly went out, as the stadium and much of Wolverhampton town centre were thrown into darkness by a power cut. The players and spectators stood around for twenty-five minutes until the game could be restarted, but it was not until the second half that a Wolves goal came, following a fiftieth-minute goalmouth melée, with Darlaston-born Mel Eves (below) the scorer of what was destined to be the last Wolves’ goal to be scored in a European competition until 2019. Ominously, the lights went out again as Eves scored. Wolves were denied two penalties and, urged on by Emlyn Hughes (above), they threw everything into attack but failed to get another breakthrough.

Once again, the dream was over. As Mel Eves later wrote, neither the players nor the fans envisaged the catastrophes that were looming on the horizon, nor that this would turn out to be their last European adventure for a very long time:

“I often get asked what it was like to be the last Wolves player to score a goal in a European competition; the answer is simple: at the time, neither I, nor anyone else that I know of, could have imagined that this would be Wolves’ last European goal; I’d never have believed it if someone had told me that. I suppose my best answer is that it was great to score any goal for Wolves. Now I can’t wait to lose the tag because for someone to score a European goal would mean we’d have regained our rightful place in the top echelon of English football, back where Wolves belong.”

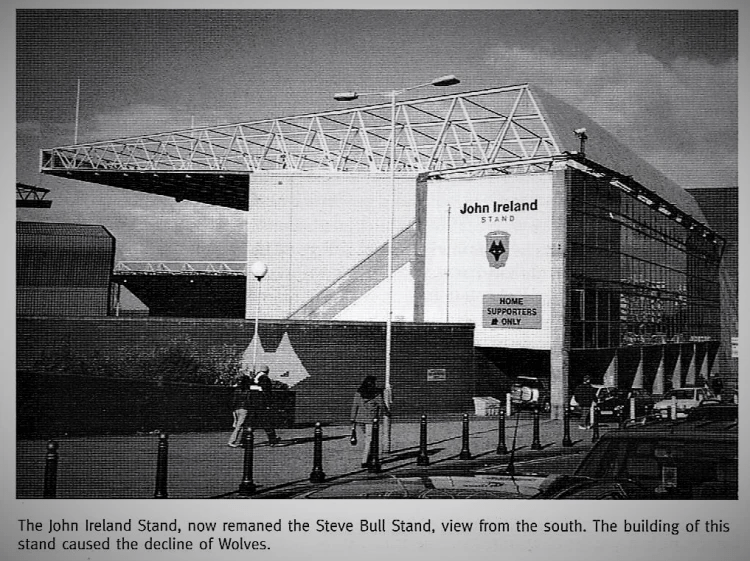

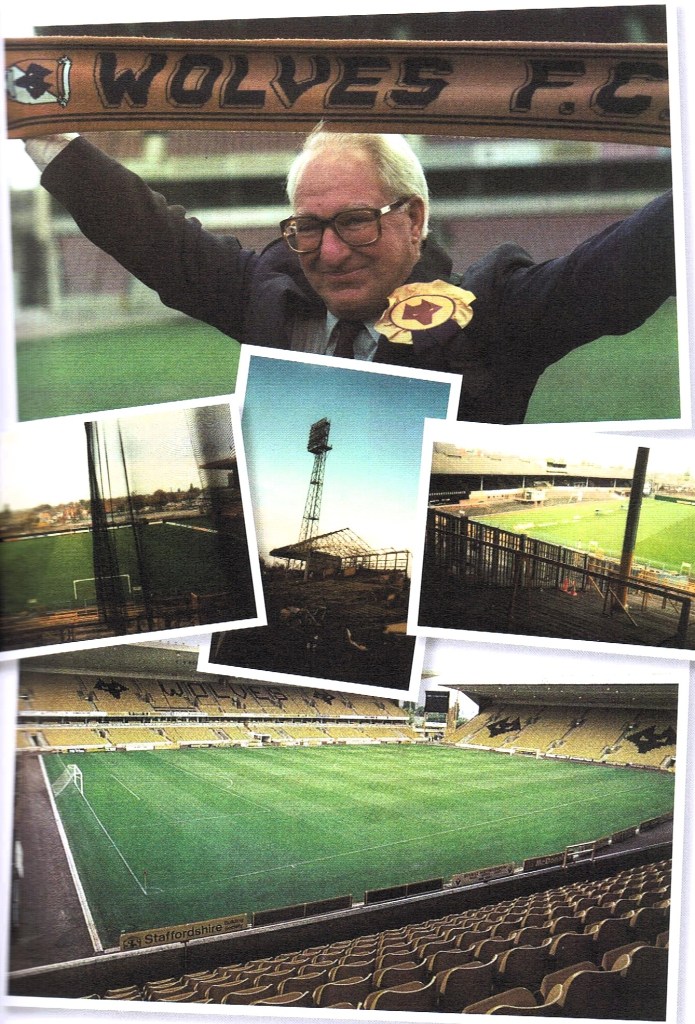

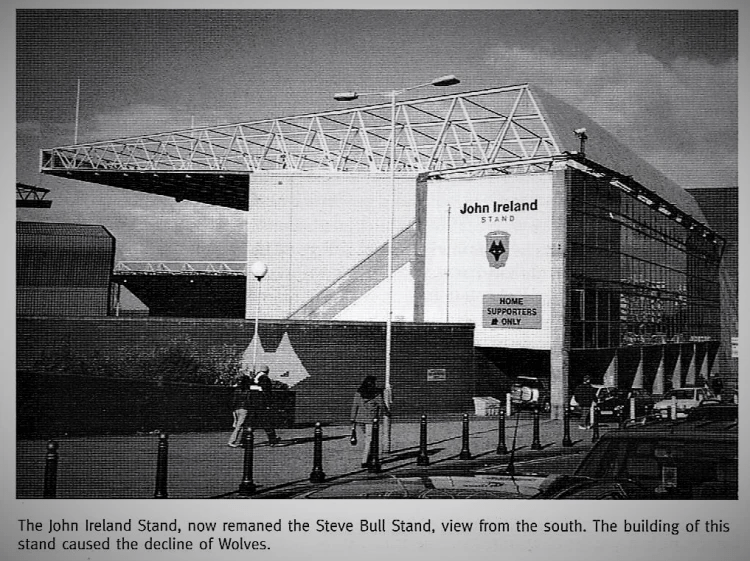

The 1980s were one of the most difficult decades in the history of British football, and Wolves found themselves at the forefront of the financial struggle. The construction and associated cost of the ‘New Stand’ (below) had really put pressure on finances at Wolves just at the time when the team declined to eighteenth place and was relegated at the end of the 1981-82 season. In the summer of 1982, the club faced bankruptcy, with the local newspaper, The Express and Star, headlining “Wolves Have Gone Bust”. Derek Dougan led a consortium to save the club. It made sweeping changes immediately, replacing its management team with a team led by Graham Hawkins, a former Wolves player and supporter. He guided Wolves to an immediate promotion in 1982-83, when Wolves were runners-up.

However, the promotion was a false dawn, and in 1983-84 Wolves were again relegated after a miserable season in Division One. In the 1984-85 season, Wolves won only eight games in another miserable season. From mid-November 1984 to mid-April 1985 Wolves failed to score a single goal at Molineux. On Saturday 11th May 1985 Wolves played their final Division Two fixture at Ewood Park, Blackburn. Meanwhile, just over the Pennines, fifty-six supporters were tragically killed in a fire at Bradford City’s Valley Parade Stadium. This horrendous event led to the Popplewell Enquiry, which directly affected Molineux.

The North Bank and the Waterloo Road Stand were closed due to their wooden content. When they were declared unsafe at the beginning of the 1985-86 season, the Wolves were close to being unable to play at their ground. But Wolves did take their place in Division Three, the first time they had been in the third tier since 1923-24. The season ended in their third successive relegation. These three disastrous seasons saw the Old Gold plummet from Division One to Division Four in consecutive seasons. Meanwhile, Molineux continued to crumble. The club was saved from being wound up by a three-way consortium led by Asda Supermarkets, which marked a turning point in the club’s fortunes. The Club was then joined as manager by Graham Turner, formerly of Watford and England fame, a boyhood Wolves fan.

Under Turner’s leadership, in 1987-1988, the Wolves stormed to the Fourth Division title and the following season, to the Third Division title. A lot of their success was down to Steve Bull scoring more than fifty goals in two consecutive seasons. As a third-tier player, this earned him a surprise call-up to the England team in 1989. He went on to represent his country in the World Cup in Italy in 1990. He scored four goals in thirteen internationals, but despite scoring 309 goals for Wolves, a club record, he never had the chance to play in European club competition before injury ended his career in 1999.

By the nineties, the Wolves were back in Division Two, so in the 1980s, they had played on almost every league ground in England and Wales. But the Hillsborough Enquiry put more pressure on all these grounds, including Molineux, which added to the costs and issues already faced as a result of the Popplewell Report of 1985.

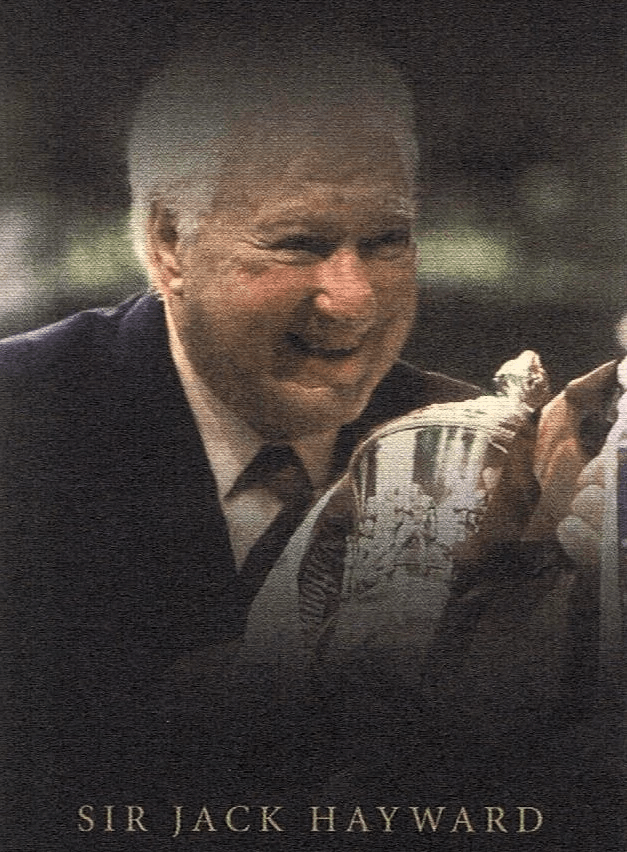

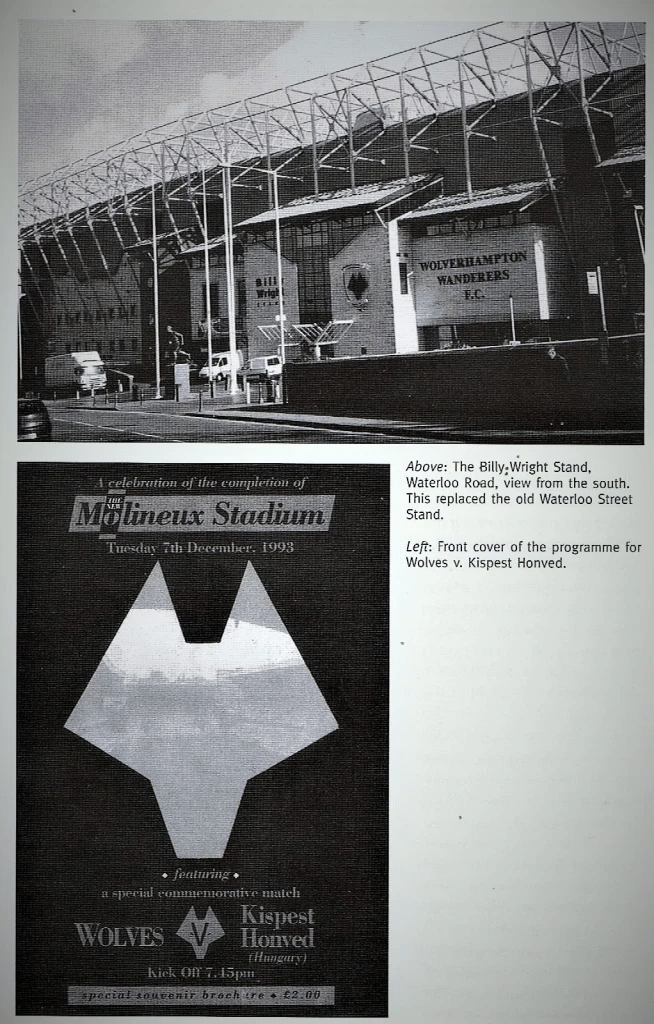

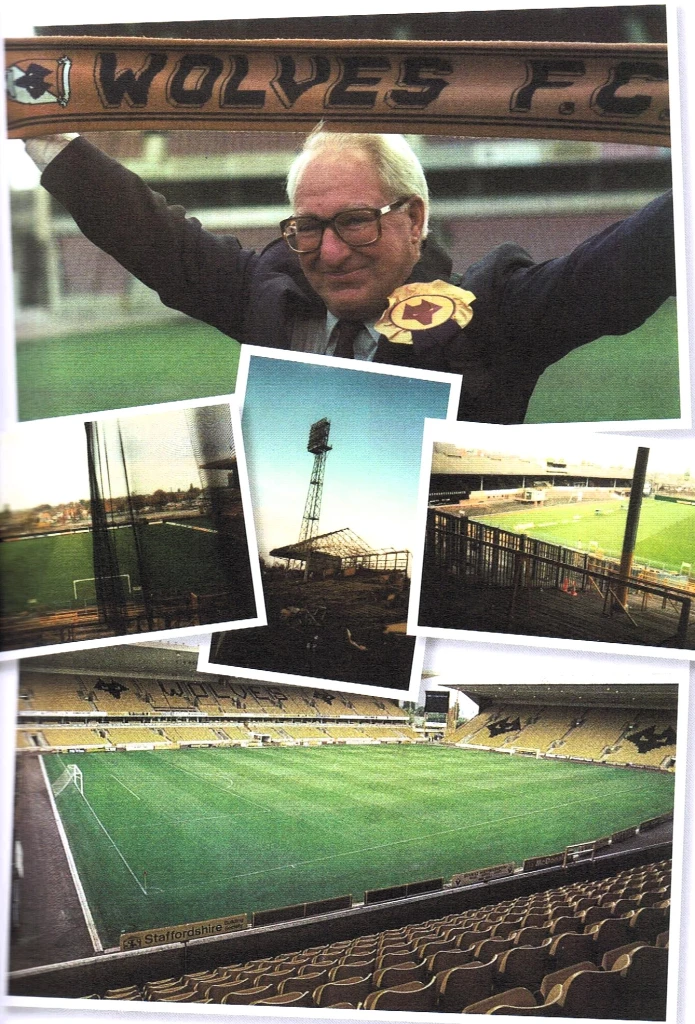

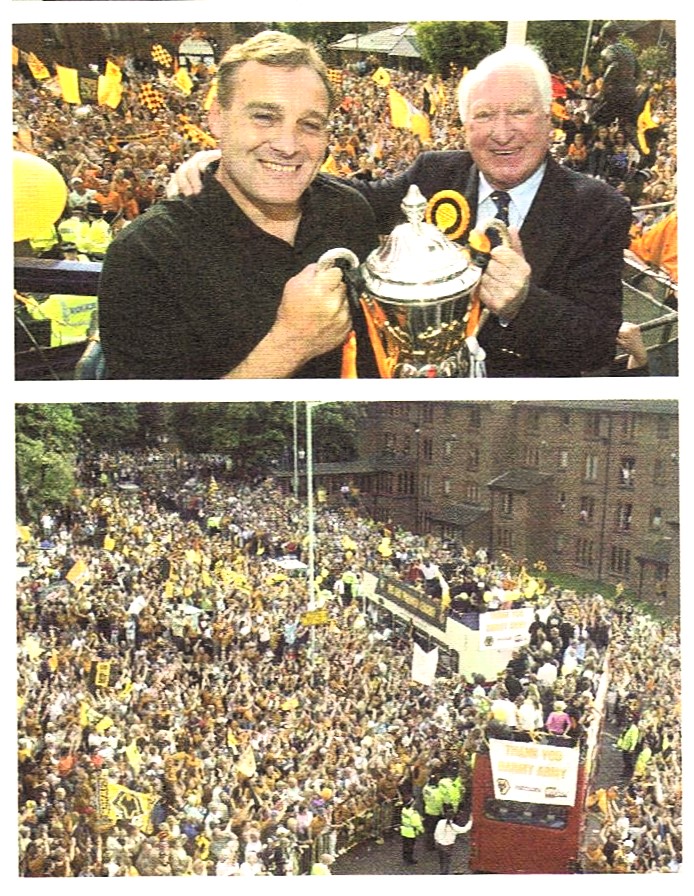

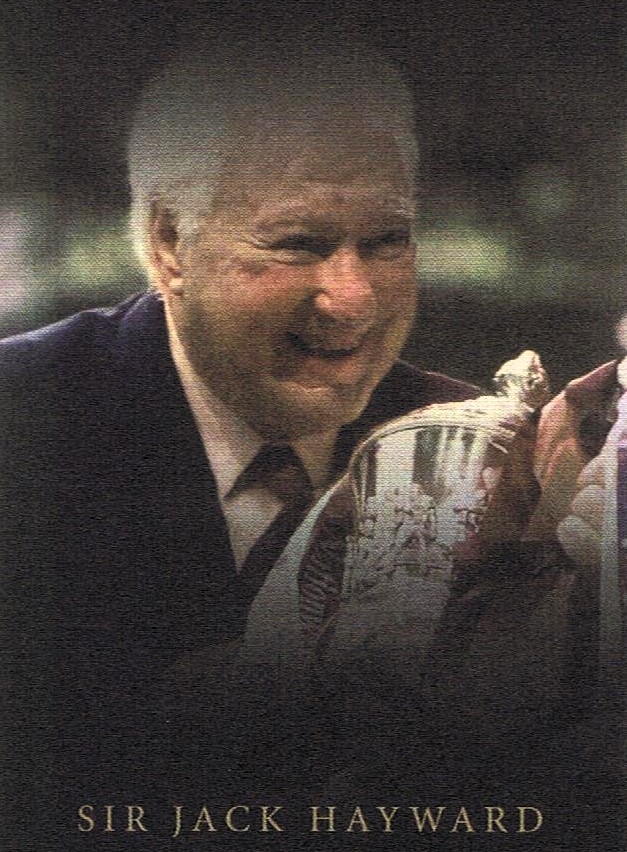

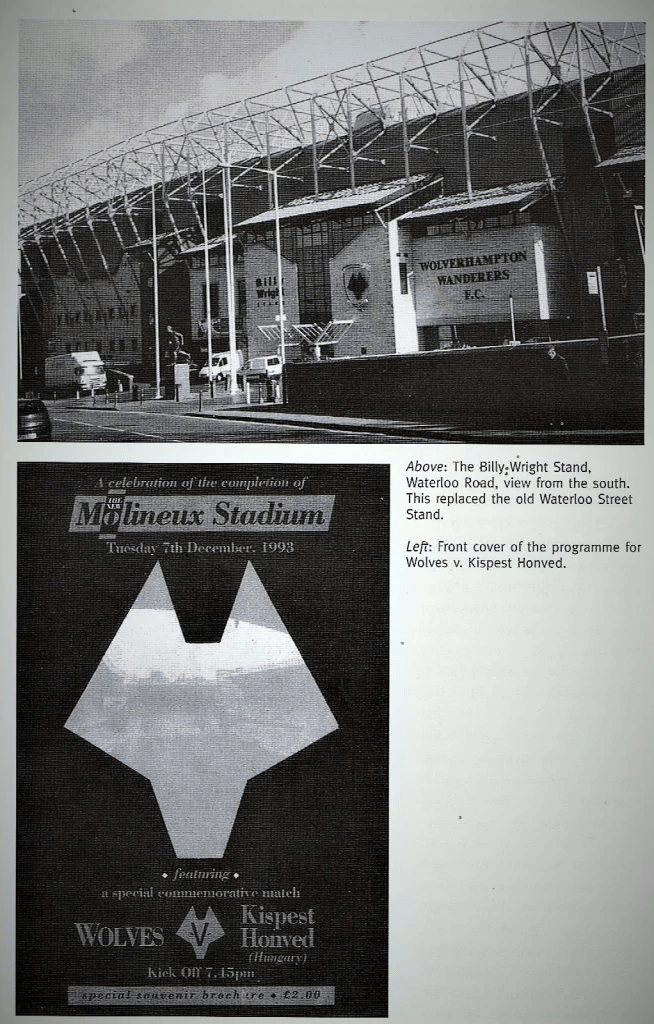

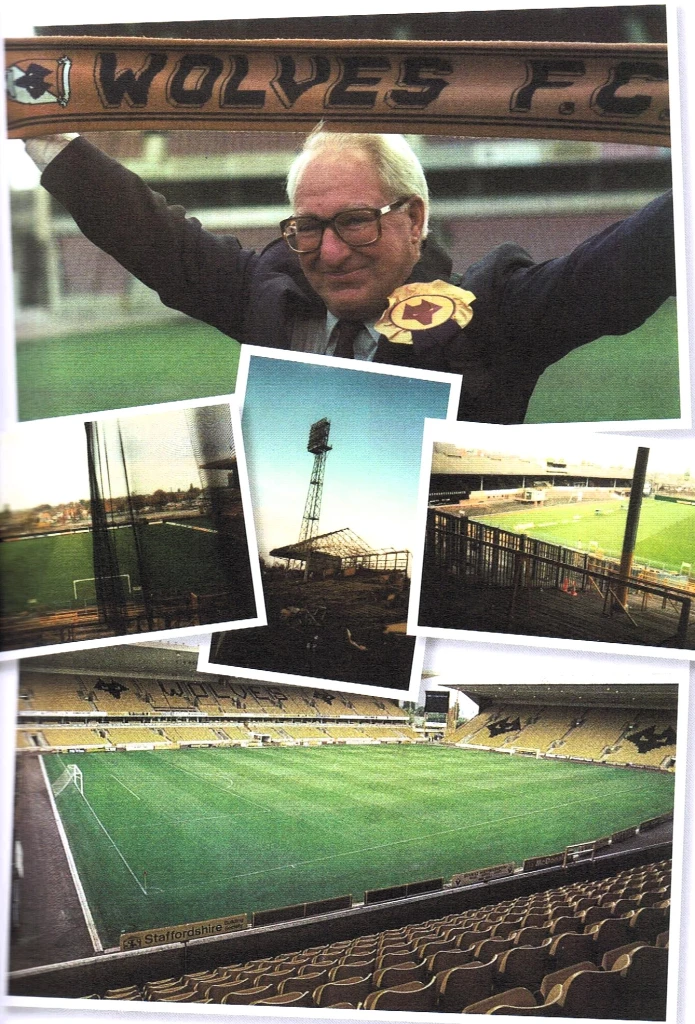

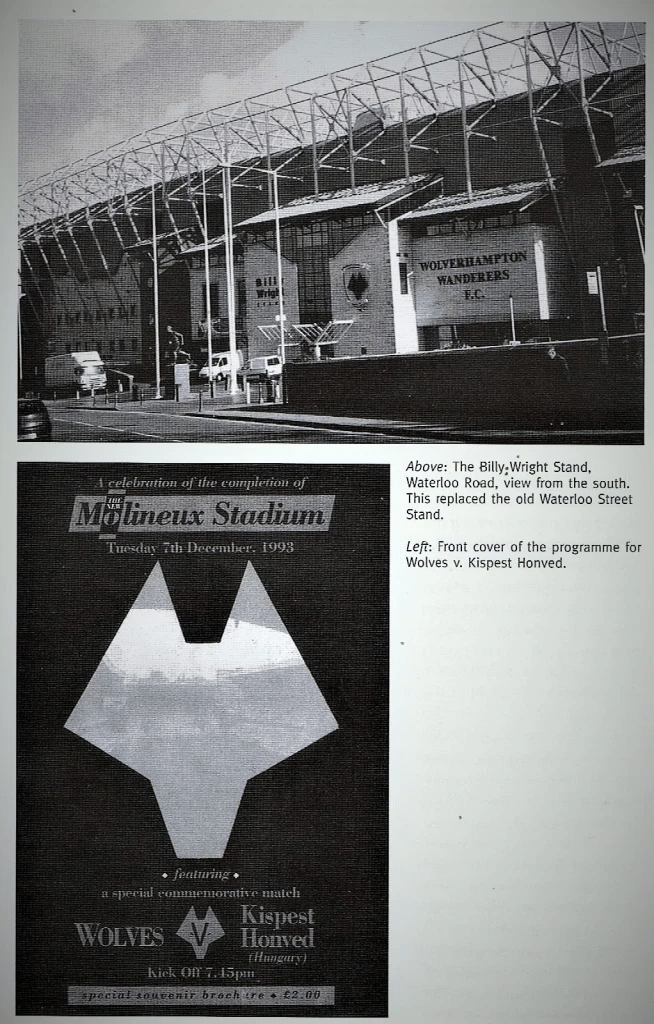

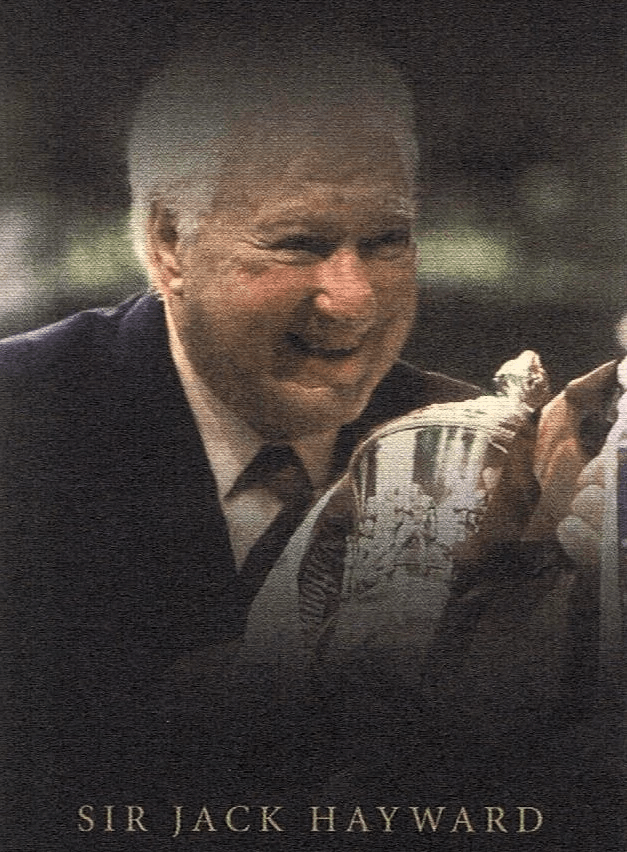

The Taylor Report meant the clock was ticking and the redevelopment of Molineux needed to happen with a sense of urgency. Lifelong fan Jack Hayward (pictured above) stepped in to purchase the club in 1990 and immediately funded the extensive redevelopment of a by-then-dilapidated Molineux into a modern all-seater stadium, one of the best in the country. The rebuild began in 1991 and was completed in 1993, after which Hayward redirected his investment onto the playing side in an attempt to win promotion to the newly formed Premier League, which took another ten years, into the twenty-first century.

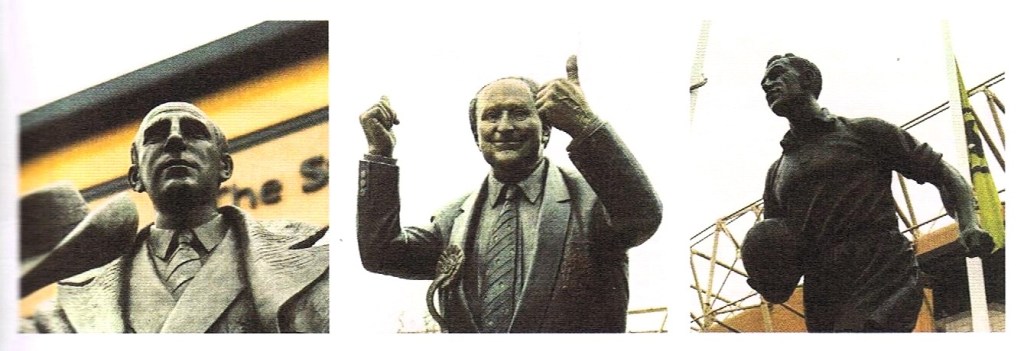

To mark the opening of the new stands, named after Stan Cullis, Billy Wright and Jack Harris, and celebrate the new-look stadium, there was a special fixture against Kispest Honved scheduled for 7 December 1993. This was the first time Wolves supporters had seen a four-sided Molineux since 1985. Interestingly, this was the third friendly floodlit match against Honved at Molineux, thirty-nine years after the first. A lasting memory of that night was Billy Wright and Ferenc Puskás standing in the players’ tunnel before kick-off. Puskás had recently returned from Australia, where he managed South Melbourne between 1989 and 1992. In their playing days, Puskás had twice led Wright a ‘merry dance’ when Hungary met England and now Wright was reduced to laughter when a wag shouted in broad Black Country: “Billy, that’s the closest yo’ve ever got to ‘im.” There was a short delay because of another failure in the floodlighting. But compared with some of the darker days of the previous fifteen years, this was not a major issue since, as Wolves fans knew, Out of Darkness Cometh Light. The capacity all-seated crowd of 28,245 watched the visitors hold Wolves to a 2-2 draw.

In August 1998, Wolves again met Barcelona in a pre-season friendly match to celebrate the club’s 125th anniversary. Then, after the tragedy of seeing West Brom ‘steal’ promotion by finishing second in Division Two in 2001-02 and losing to Norwich in the play-off semi-final, Wolves finally returned to the top flight after winning against Sheffield United at the Millennium Stadium, Cardiff in the 2003 play-off final. Wolves were back in the top division in time to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of their first-ever friendly under floodlights at Molineux. As John Shipley put it in 2003:

‘Yes, there have been other more recent floodlit friendlies, but none that have recaptured or have gone any way towards evoking the wonderful atmosphere of those games in the 1950s, or those in the various European competitions in which Wolves competed. …’

Shipley (2003), p.191.

Below: crowds join them in the centre of Wolverhampton.

In 2003-04, I returned to Molineux with my cousin and twelve-year-old son to watch the Wolves beat Manchester United and Fulham in their first season back in the First Division. These were memorable moments, but unfortunately, their return to the top flight under Dave Jones only lasted one season. They finished bottom and returned to what had become ‘the Championship’. After a slow start in the 2004-05 campaign, Jones was dismissed in November 2004 and replaced by former England manager Glenn Hoddle. He managed to steer Wolves to ninth in the 2004-05 campaign and seventh in 2005-06, but then suddenly resigned in July 2006. Sir Jack made his final managerial appointment with Mick McCarthy who set about rebuilding the team when there was hardly any of the squad left. This led to another play-off finish, in which Wolves lost narrowly to West Brom. Nevertheless, the campaign was way above even the most positive Wolves supporter’s expectations, restoring confidence in the Molineux fan base. In the 2007-08 season, Sir Jack’s last, McCarthy led the Wanderers to a strong seventh place, slightly lower than the play-off places. In his time at the club, Sir Jack Hayward had rebuilt the infrastructure of the club, leaving a Molineux to be proud of and a new training ground of a very high standard.

More Ups & Downs, 2008-2017:

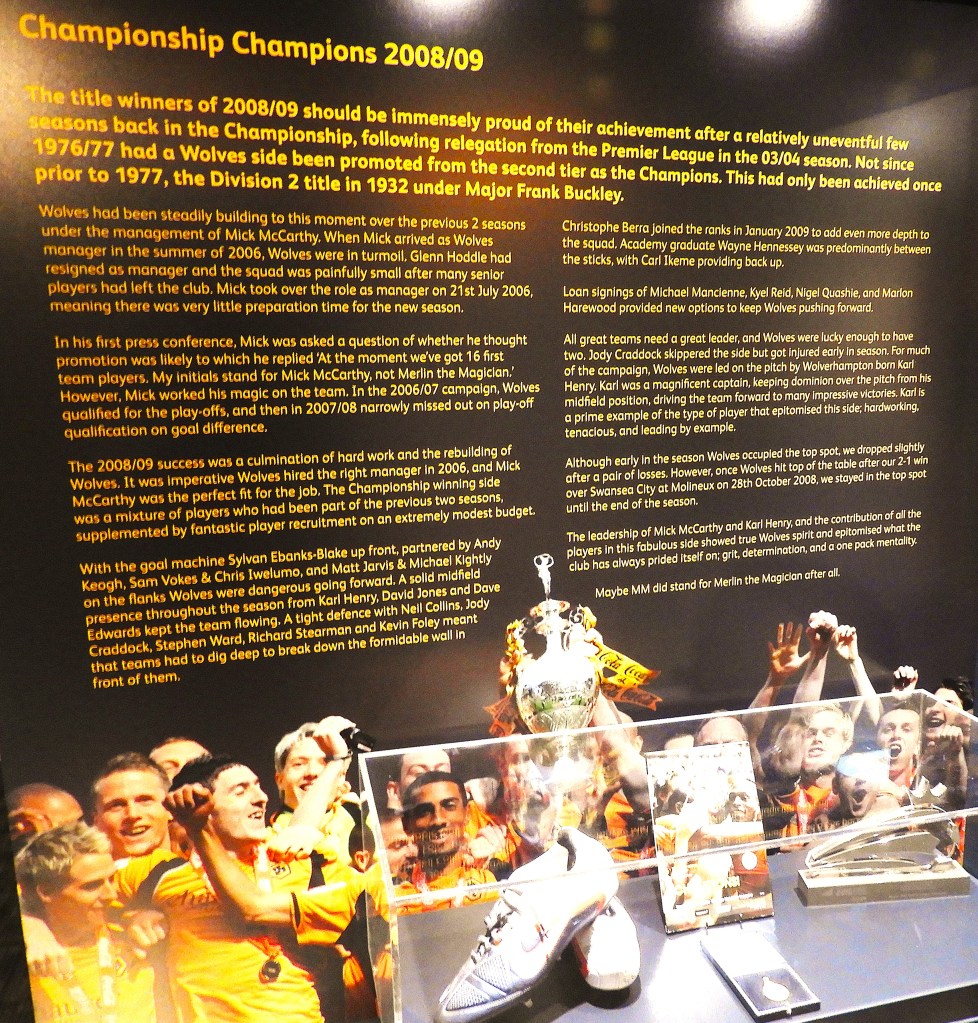

In 2008, Jack sold the club to Steve Morgan for a nominal fee of ten pounds on the condition that Morgan would invest up to thirty million in the club. Mick McCarthy won the Championship in 2008-09, only the third Wolves manager to win the second-tier title after Major Buckley and Sammy Chung. His team also won it in fine style in a superb season. They finished seven points clear of runners-up Birmingham City and ten clear of Sheffield United in third. There were also impressively consistent individual performances throughout the team. Wolves were back in the Premier League after five years away and there were many more memorable moments, like the last day of the 2010-11 season that saw the Wanderers narrowly avoid relegation on goal difference. Again, there were some fine victories against Manchester United, Manchester City and Arsenal. The new owner, Steve Morgan, believed that Molineux needed to be bigger to host Premier League football, to take its capacity to forty thousand. The Stan Cullis stand came down at the end of the season and was replaced with a two-tier stand which also houses the club megastore and museum.

However, the 2011-12 season, with Molineux’s reduced capacity, sadly saw the club relegated. McCarthy was sacked in February 2012, following a dismal display against West Brom. He was replaced by Terry Connor, who could not stop the Wolves from being relegated. Connor’s successor, Norwegian Stale Solbakken, was also dismissed in January 2013 after a run of poor performances, to be replaced by Dean Saunders. He could not prevent a further relegation to League One, the third tier, but the astute appointment of Kenny Jackett ensured that Wolves romped to the League One title in 2014 with a record 103 points. The subsequent promotion back to the Championship felt like another turning point for the club and its fans. Jackett was very unlucky not to get the team into the play-offs at the end of the 2014-15 season, and when the team slipped back to a mid-table place in 2015-16, he left the club.

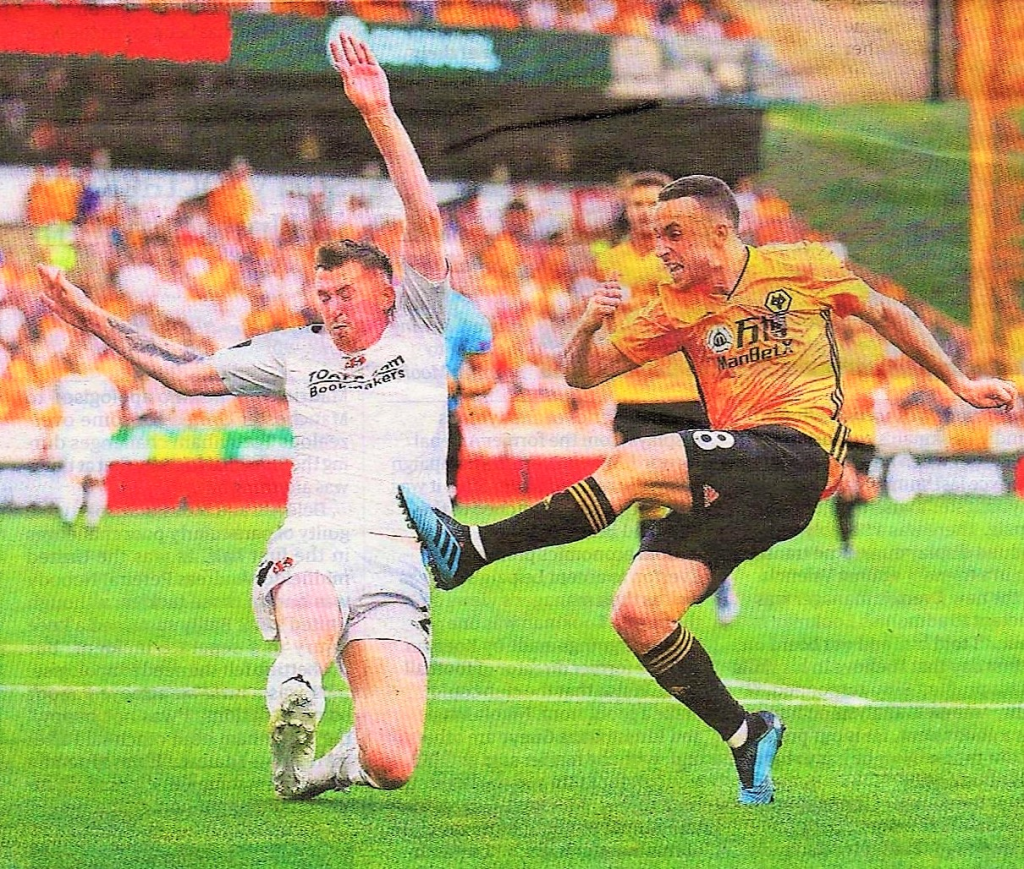

The 2016-17 season was not the best of seasons, but in the summer of 2017, the ‘Fosun revolution’ (named after the new owners, Fosun International) began to take shape. The appointment of Nuno Espirito Santo signalled the real beginning of the new era, along with the arrival of various Portuguese players. Evertonian Conor Coady, who had arrived at the club in the summer of 2015, took on a new role as a sweeper and was made club captain. Wolves took the Championship apart and won it at a canter with the entire squad impressing and Head Coach Nuno quickly becoming a club hero. The 2017-2018 season for all involved was incredible. Wolves were Champions and back in the Premier League after a five-year gap. This time it felt somewhat different, however. Ruben Neves and Diogo Jota had arrived in 2017, along with Wily Boly.

The Wanderers’ Return To Europe, 2018-20:

In the Summer of 2018, Wolves were joined by further exciting arrivals from Portugal in the guise of internationals, goalkeeper Rui Patricio and Joao Mutinho, sending a clear message of intent to the other Premier League clubs: Wolves were not back in the top flight simply to make up the numbers. They were determined to compete and they succeeded in this by finishing seventh at the end of their first season back, securing a place in the Europa League. Wolves also got to the FA Cup semi-final and their supporters had a wonderful Wembley day out. But despite the heroics from Mexican star Raul Jimenez, the match finished in defeat to Watford.

Picture: Matthew Childs/ Reuters

On the hottest July day on record in 2019, Wolves played the Belfast club Crusaders, who finished fourth in the Irish Premiership in the 2018/19 season, also winning the Irish Cup. Wolves won 2-0 and went through to the next round, after winning by a similar margin in the return leg in Belfast the following week. Before the opening game, highlights of the Molineux team’s historic 1950s triumphs over Spartak Moscow and Budapest Honvéd were beamed on the big screens. After their victory over Crusaders in the Europa League, Wolves then went on to beat the Arminian club Pyunik, 8-0 on aggregate, and on 29 August, they booked their place in the Europa League group stage after beating Torino in front of a jubilant Molineux. The Black Country side were in the main stage of a European competition for the first time since 1980 after coming through three rounds of qualifiers. Their popular Portuguese manager, who had turned the club around since his 2017 appointment when they were in the Championship, named a strong team. They started the game on the back foot, however, with Torino dominating possession and Wolves playing a counter-attacking game. But wing-back Traore was lively down the right and forced a save from Salvatore Sirigu after a sensational surging run, before setting up Jimenez for the opener.

Torino needed three goals at that stage and for about sixty seconds they seemed back in the tie when Italian international Belotti headed in Daniele Baselli’s free-kick. That made it 4-3 on aggregate, but Leander Dendoncker put the game out of reach. Wolves had restored their two-goal aggregate advantage when Diogo Jota’s shot was saved and Dendoncker’s first-time shot from sixteen yards went in via the post. That goal meant Torino needed to score twice to force extra time, and, despite some late chances, a comeback never seemed likely. Wolves’ European run ended up causing problems for their twenty-one-man first-team squad – this was their ninth game in thirty-six days – but that was a problem boss Nuno Espirito Santo wanted:

“Work started two years ago and this is the next step. This is massive for us.

“It has been tough so far. The way the fans push us, they are the twelfth man.”

In reaching the Europa League group stage, Wolves had returned to the European competition they played a significant role in inspiring sixty-five years before. Just reaching the Europa League group stage had not been an insignificant task for Wolves. Home and away victories in the play-off round against Torino represented only the eleventh time an English club had beaten the same Italian opposition in back-to-back games in the entire history of European competition. It was a notable achievement for a side whose history was well-known around Europe. In the main stage of the competition, Wolves were drawn against Braga, Besiktas and Slovan Bratislava. They qualified out of the group in second place, only losing one game. Success continued when they then defeated Espanyol in the Round of thirty-two and Olympiacos in the last sixteen. Despite beating the top Greek team in Athens, due to the Covid-19 pandemic supporters were unable to attend. The second leg of the tie took place almost five months later. Wolves progressed to the quarter-final where they played Sevilla at a neutral venue in Germany, behind closed doors and in a one-legged tie. Unfortunately, the Wolves ‘bowed out’ of the competition in a narrow 1-0 defeat. In 1919-20, Wolves replicated their previous season’s seventh-place finish in the Premier League, but with two more points, and only missed out on a return to continental competition on goal difference.

The Post-Pandemic Seasons – The End of the Legend?

Despite the difficult circumstances of the pandemic that had taken control of the world at this point, and the number of games Wolves had to play at home and away, including in European competition, Wolves had not managed to finish this high in the top League since the consecutive seasons of 1959-60 and 1960-61. Nuno’s final season was 2020-21, the majority of it played behind closed doors, and even when crowds did return it was in very minimal numbers. There were also serious injuries to Jimenez, Pedro Neto and Jonny which resulted in the team slipping to thirteenth in the League. Nuno left in 2021 after achieving a measure of greatness to compare with former glories, leaving the supporters with great memories of some extraordinary excursions around Europe before the pandemic hit. In the eyes of the fans, he had become its latest legend.

On 9th August 2023 Wolves appointed Gary O’Neil as their new manager, following short spells in charge from Bruno Lage and Julen Lopetegui. O’neil had steered Bournemouth to safety the season before. He had only five days to work with the players before the opening day’s visit to Old Trafford where, despite an impressive performance, they lost. The first home games also saw defeats, but then they climbed back to seventh before dropping to fourteenth by the end of the season. Along the way, they recorded great wins against champions Manchester City, Tottenham and Chelsea. They also beat West Brom at the Hawthorns for the first time since 1996, in the FA Cup. However, in the current season, they remain as far away as ever from qualifying for European competition.

The Light Shines on…

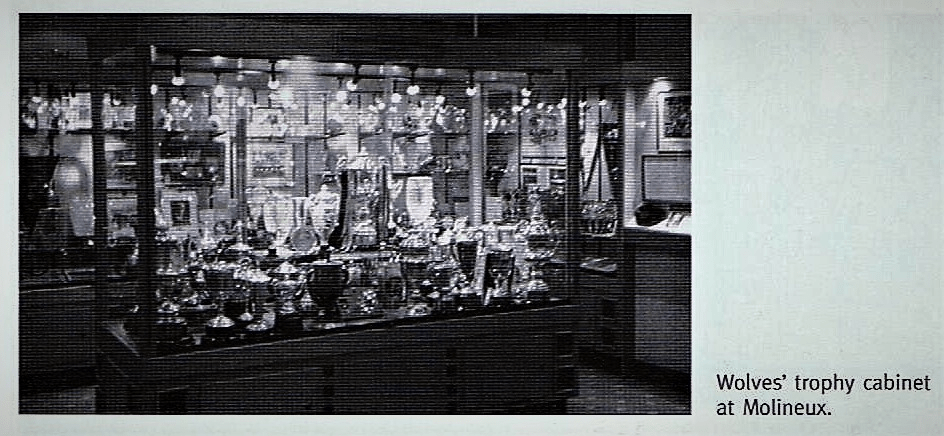

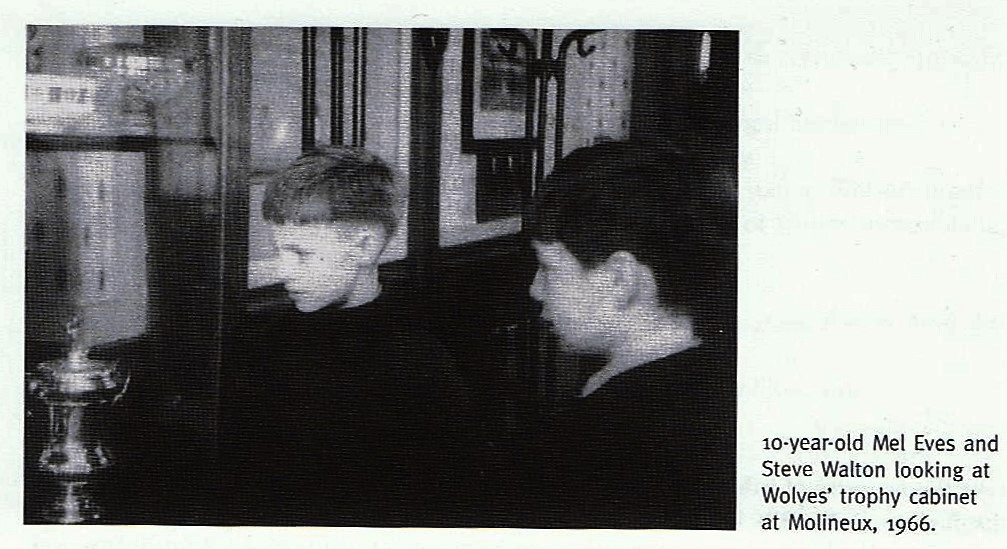

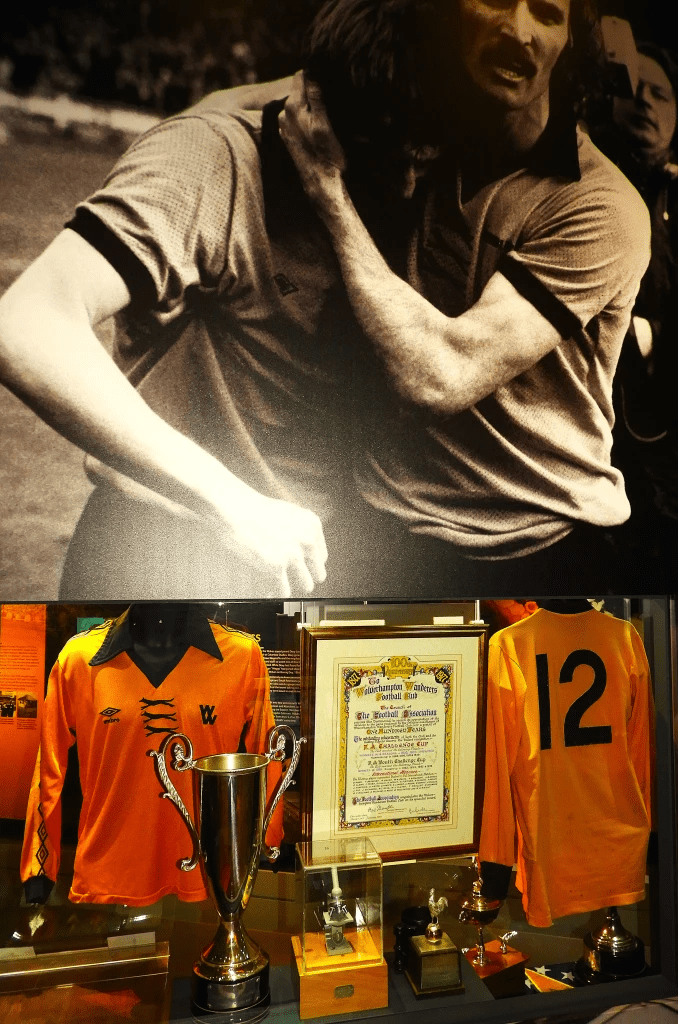

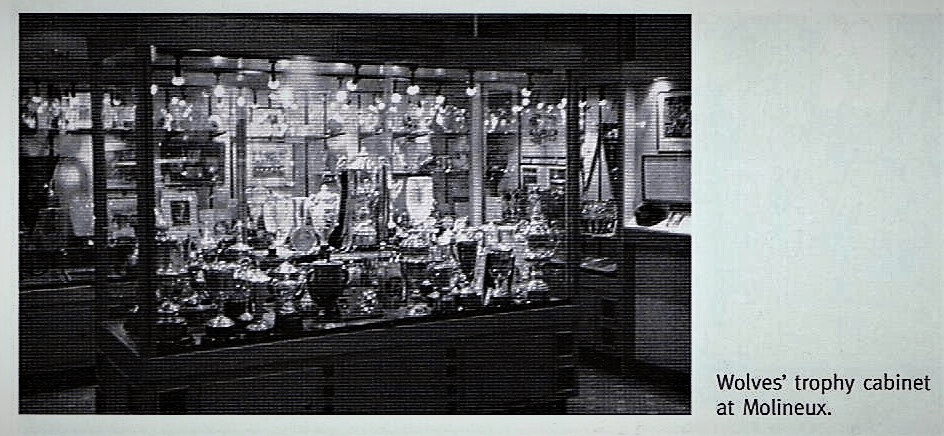

In his foreword to the Wolves Museum Guide, Mel Eves recalls his junior school trip to Molineux when he looked ‘in awe at the trophy-filled cabinets’ in the main entrance to the stadium in Waterloo Road. In 1974, like me, he was in the sixth form of Grammar School when he made his first trip to Wembley to see his team, the Wolves, beat a star-studded Manchester City 2-1, to lift the Football League Cup for the first time. His second visit was in 1980 when he was playing in the Wolves team which beat the Nottingham Forest team that went on to retain the European Cup at the end of the season. He commented:

“I was very blessed to be able to play football professionally. It was even more special to fulfil my boyhood ambition with the team I had always supported. Before my nine years at Wolves ended… in May 1984 aged twenty-seven, I had played in 214 games and scored fifty-three goals. … The rich history of the club, from being a founder member of the Football League, all the way through competing with the best in Europe and the Premier League, is brought to life in the Museum experience.”

Mel Eves, quoted in Wolves Museum Guide, 2024, loc. cit.

As a Wolves fan of a very similar age, who as a young lad wanted to play for the Wolves and who visited the Museum earlier this year, I share his opinion, and the city and club motto, Out of darkness cometh light. After all, Chandlers make candles, which shed light into the darkest of corners!

Sources:

György Szöllősi (2015), Ferenc Puskás: The Most Famous Hungarian. Budapest: Rézbong Kiadó.

György Szöllősi, Zalán Bodnár (2015), Az Aranycsapat Kinceskönyve (‘The Golden Team Treasure Book’). Budapest: Twister Media.

Bán Tibor & Harmos Zotán (2011), Puskás Ferenc. Budapest: Arena 2000.

Czégány Pál (2021), Albert 80: The Legacy of the One and Only Hungarian Ballon d’Or Winner. Budapest: Ferencvárosi Torna Club: Albert Flórián Labdarúgó Utánpótlás és Sportalapitvány (www.albertalapitvany.hu).

John Shipley (2003), Wolves Against the World: European Nights, 1953-1980. Stroud (Glos.): Tempus Publishing.

Molineux Stadium (2024), Wolves Museum Guide, Third Edition.: Wolverhampton: Synaxis Design Consultancy.

Gallery: