Berlin, 1941 – Genesis of a Genocide:

Over these past three weeks, there have been many attempts by jihadi propagandists, followed sheepishly by their international apologists and extremists, to excuse or ‘explain’ the pogrom of 7th October by reference to the events of the past seventy-five years of the Arab-Israeli conflict. However, in checking through the documents on both ‘sides’, I can find no justification for any direct link to be drawn.

We may be thoroughly familiar with the litany of wars, massacres and ‘intifada’ that have occurred since the establishment of the state of Israel, but there has been no equivalence, to my historian’s mind, since the actions planned and carried out by the Nazis and their fascist allies against the central European Jews and Gipsies in the Holocaust and ‘Final Solution’ of 1938-1944. Haj Amin al Husaini, the most influential leader of the Palestinian Arabs at that time, lived in Germany during the Second World War. According to the official documents on German Foreign Policy, he met Adolf Hitler, Ribbentrop and other Nazi leaders on various occasions and attempted to coordinate Nazi and Arab policies in the Middle East. In the record of one of these meetings, on 28th November 1941, Husaini – then Grand Mufti of Jerusalem – stated that:

‘The Arab countries were firmly convinced that Germany would win the war and that the Arab cause would then prosper. The Arabs were Germany’s natural friends because they had the same enemies as had Germany, namely the English, the Jews and the Communists. They were therefore prepared to cooperate with Germany with all their hearts and stood ready to participate in the war, not only negatively by the commission of acts of sabotage but and the instigation of revolutions, but also positively by the formation of an Arab Legion. The Arabs could be more useful to Germany as allies than might be apparent atfirst glance, both for geographical reasons and because of the suffering inflicted upon them by the English and the Jews.

Furthermore, they had had close relations with the Moslem nations, of which they could make use in behalf of the common cause. … An appeal by the Mufti to the Arab countries and the prisoners of Arab, Algerian, Tunisian and Moroccan nationality in Germany would produce a great number of volunteers eager to fight. Of Germany’s victory the Arab world was firmly convinced, not only because the Reich possessed a large army, brave soldiers and military leaders of genius, but also because the Almighty could never award victory to an unjust cause. …

‘The Führer replied that Germany’s fundamental attitude on these questions, … was clear. Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews. That naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine, which was nothing but a centre, in the form of a state, for the exercise of destructive influence by Jewish interests. Germany was also aware that the assertion that the Jews were carrying out the function of economic pioneers in Palestine was a lie. … Germany was resolved, step by step, to ask one European nation after the other to solve its Jewish problem, and at the proper time direct a similar appeal to non-European nations as well.

‘Germany was at the present time engaged in a life and death struggle with two citadels of Jewish power: Great Britain and Soviet Russia. Theoretically there was a difference between England’s capitalism and Soviet Russia’s communism; actually, however, the Jews in both countries were pursuing a common goal. This was the decisive struggle; on the political plane, it presented itself in the main as a conflict between Germany and England, but ideologically it was a battle between National Socialism and the Jews. It went without saying that Germany would furnish positive and practical aid to the Arabs involved in the same struggle, because platonic promises were useless in a war for survival or destruction in which the Jews were able to mobilise all of England’s power for their ends.

‘Germany was now engaged in very severe battles to force the gateway to the northern Caucasus region. … The Führer then made the following statement to the Mufti, enjoining him to lock it in the uttermost depths of his heart:

1. He (the Führer) would carry on the battle to the total destruction of the Judeo-Communist empire in Europe.

2. At some moment… not distant, the German armies would would would in the course of this struggle reach the southern exit from Caucasia.

3. As soon as this happened, the Führer would… give the Arab world the assurance that its hour of liberation had arrived. Germany’s objective would then be solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in in the Arab sphere under the protection of British power. In that hour, the Mufti would be the most authoritative spokesman for the Arab world. It would then be his task to set off the Arab operations which he had secretly prepared. …

‘Once Germany had forced open the road to Iran and Iraq through Rostov, it would also be the beginning of the end of the British world empire. He… hoped that the coming year would make it possible for Germany to thrust open the Caucasian gate to the Middle East. ‘

Walter Laqueur (1976): The Israel-Arab Reader, pp. 80-81: Berlin, November 30, 1941. Record of the Conversation Between the Führer and the Grand Muft of of Jerusalem on November 28, 1941, in the Presence of Reich Foreign Minister and Minister Grobba in Berlin.

Following the thwarting of Hitler’s plans at Stalingrad and the defeat of Nazi Germany across Europe, an Anglo-American Inquiry was appointed in 1945 to examine the status of the Jews in former Axis-occupied countries and to find out how many were impelled by their conditions to migrate to Palestine. Britain, weakened by the war, found itself under growing pressure from both Jews and Arabs alike. The new Labour Government decided, therefore, to invite the United States to participate in finding a solution. The Report of the Committee on Inquiry was published on 1st May 1946. President Truman welcomed its recommendation that the immigration and land laws of the 1939 White Paper be rescinded. Prime Minister Attlee, on the other hand, declared that the report would have to be “considered as a whole in all its implications”. Arab reaction was hostile; the Arab League announced that Arabs would not stand by with their arms folded. The Ihud (‘Association’) group led by Professor Martin Buber favoured a bi-national solution, equal political rights for Arabs and Jews, and a Federative Union of Palestine and the neighbouring countries. But Ihud found little support among the Jewish community, though it had a few Arab sympathisers. However, after some of them were assassinated by supporters of the Mufti, the others withdrew their support for a bi-national solution.

The Partition of Palestine & The 1948 War:

A war-exhausted British Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, announced on 14th February 1947 that HM’s Government had decided to refer the Palestine problem to the newly-created United Nations. Tensions inside Palestine had risen, illegal Jewish immigration continued, and there was growing restiveness in the Arab countries: Palestine, Bevin said, could not be so divided as to create two viable states, since the Arabs would never agree to it, the Mandate could not be administered in its present form, and Britain was going to ask the United Nations how it could be amended. The UN set up a Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) composed of representatives from eleven member states. Its report and recommendations were published on 31st August 1947. The Jewish Agency accepted the partition plan as the ‘indispensible minimum’, but the Arab governments and the Arab Higher Executive rejected it. On 29th November 1947, the UN General Assembly endorsed the partition plan by a vote of thirty-three to thirteen. The two-thirds majority included the US and USSR, but not the UK.

The United Nations resolution about the partition of Palestine was bitterly resented by the Palestinian Arabs and their supporters in the neighbouring countries who were determined to prevent, with force of arms if necessary, the establishment of a ‘Zionist’ state by the “Jewish usurpers”. The terminology used clearly indicated both an anti-Zionist and an anti-Semitic attitude to the foundation of this state. In reality, the two terms now became almost synonymous. On 14 May 1948, The State of Israel Proclamation of Independence was published by the Provisional State Council, the forerunner of the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. The British Mandate, given by the League of Nations thirty years previously, through which successive British governments had controlled Palestine over the previous thirty years, was terminated the following day and regular armed forces of Transjordan, Egypt, Syria and other Arab countries entered the territory of the former mandate. This attempt failed and Israel, as a result, seized areas beyond those defined in the UN resolution.

Erskine Childers, an Irish journalist had published articles bitterly critical of Israeli policies. The extracts that follow are from an article published in the London weekly, The Spectator (12 May 1961). It provoked a great deal of controversy. Childers, the grandson of a well-known Irish nationalist writer, also worked for the BBC at the time:

‘The Palestine Arab refugees wait, and multiply, and are debated at the United Nations. In thirteen years, their numbers have increased from 650,000 to 1,145,000. Most of them survive only on rations from the UN agency, UNRWA. Their subsistence has already cost ($)110,000,000. Each year, UNRWA has to plead at New York for the funds to carry on, against widespread and especially Western lack of sympathy. …

‘These Arabs, in short, are displaced persons in the fullest, most tragic meaning of the term – an economic truth cruelly different from the myth. But there is also the political myth and it too has been soothing our highly pragmatic Western conscience for thirteen years. This is the Israeli charge, solemny made every year and then reproduced around the world, that these refugees are – to quote a character in Leon Uris’s ‘Exodus’ – “kept caged like animals in suffering as a deliberate political weapon.” …

‘Israel claims that the Arabs left left because they were ordered to, and deliberately incited into panic, by their own leaders who wanted the field cleared for the 1948 war. It is also argued that there would today be no refugees if the Arab States had not attacked the new Jewish State on May 15 1948 (though 800,000 had already fled before that date). The Arabs charge that their people were evicted at bayonet-point and by panic deliberately incited by the Zionists. …

‘I decided to turn up the relevant… (October 2) 1948 issue of the ‘Economist’. The passage that has literally gone round the world was certainly there, but I had already noticed one curious word in it. This was a description of the massacre at Deir Yassin as an “incident”. No impartial observer of Palestine in 1948 calls what happened at this avowedly non-belligerant, unarmed Arab village in April 1948, an “incident” – any more than Lidice is called an “incident”. Over 250 old men, women and children were deliberately butchered, stripped and mutilated or thrown into a well, by men of the Zionist ‘Irgun Zvai Leumi’.

Laqueur, p. 143.

Here, it is important to emphasise that this was a massacre undertaken by a Zionist terrorist group, not Israeli government troops. ‘Irgun’ was an organisation like the Stern Gang, and was officially disowned by Ben Gurion and the Haganah, who had carried out the earlier bombing at the King David Hotel. Irgun then called a press conference to announce their deed and paraded other captured Arabs through the Jewish quarters of Jerusalem to be spat upon. They were then released to tell their kin of the experience. Arthur Koestler called the “bloodbath” of Deir Yassin, “the psychologically decisive factor in this spectacular exodus”. Nevertheless, the government continued to spread propaganda, long after the event, that the evictions and evacuations were carried out by the Arab states with the help of Arab radio. In fact, both Arabic and Hebrew official broadcasts were reporting appeals for everyone to stay in their homes and at their jobs. Abba Eban, the Chief Israeli representative to the United Nations, who later became Foreign Minister of Israel, in a speech to the General Assembly on 17 November 1958, made the Israeli position clear:

“The Arab refugee problem was caused by a war of aggression, launched by the Arab States against Israel in 1947 and 1948. Let their be no mistake. If there had been no war against Israel, with its consequent harvest of bloodshed, misery, panic and flight, there would be no problem of Arab refugees today.”

Laqueur, p. 151.

An Israeli Government pamphlet of 1958 stated that the Jews tried, by every means open to them to stop the Arab evacuation. But while Haifa’s Mayor, Shabeitai Levi, with tears streaming down his face, implored the city’s Arabs to stay. But elsewhere in the city, as Arthur Koestler wrote, Haganah loudspeaker vans promised the city’s Arabs would be escorted to “Arab territory”. In Jerusalem, the Arabic warning from the vans was, “The road to Jericho is open! Fly to Jerusalem before you are all killed!” The ‘road to Jericho’ brought the refugees from Jerusalem into the Jordan Valley. Childers, writing in 1961, pointed out that some 85,000 were still there, at that time, in a UN camp under the Mount of Temptation. However, although he claims that official Zionist forces were directly responsible for the expulsion of ‘thousands upon thousands’ of Arabs from their villages, the evidence he presented does not appear conclusive.

The Suez Crisis, 1956:

The armistice of 1949 did not restore peace and a Palestinian Arab refugee problem came into being, along with continuing guerilla attacks and retaliations by Israel. Arab guerillas carried even after the armistice agreements had been signed and Israel retaliated in raids beyond its borders. The neighbouring Arab states refused to recognise even the ‘de facto’ existence of the Jewish state which was, in their view, illegitimate. They boycotted Israeli goods and blocked the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqabah. Egypt’s blockage of the Suez Canal led to its war with Britain, France and Israel in 1956. Although this was not directly concerned with Israel’s existence, it temporarily posed a threat to its southern border and worsened its relations with neighbouring states. General Abdel Nasser used this opportunity to make a series of speeches between 1960 and 1963. He had served as an army officer in the 1948 War and saw the ‘liberation’ of Palestine as one of the chief planks in his political programme, though historians have argued about whether there was ever, in this period, a definitive plan for ‘the liberation’. On several occasions, he announced that his army would soon be ready to enter Palestine on “a carpet of blood”. He wrote later that:

‘… when the Palestine crisis loomed on the horizon, I was firmly convinced that the fighting in Palestine was not fighting on foreign territory. Nor was it inspired by sentiment. It was a duty imposed by self-defence.’

Laqueur, loc. cit., pp. 137-38.

In 1963, Nasser helped write a ‘manifesto’ concerning the principles of the new Federal State of the United Arab Republic was published in April 1963. It was prepared in connection with an abortive attempt to establish a federal union in the Arab world and was signed by Gamel Abdel Nasser and the presidents of Iraq and Syria. As a document, it is of interest mainly in view of the reference to Palestine:

‘Unity is a revolution – a revolution because it is popular, a revolution because it is progressive, and a revolution because it is a powerful tide in the current of civilisation… It is profoundly connected with the Palestine cause and with the natural duty to liberate that country. It was the disaster of Palestine that showed the weakness of and backwardness of the economic and social systems that prevailed in the country, released the revolutionary energies of our people and awakened the spirit of revolt against imperialism, injustice, poverty and underdevelopment.’

Walter Laqueur (ed.) (1976), The Israel-Arab Reader, p. 130.

The Six Days’ War, 1967:

After a decade of uneasy truce, there was a new escalation of violence culminating in the Six Days’ War in 1967. On 5th June, Egyptian forces moved against Israel’s western coast and southern territory by air and land. After five days of determined resistance, Israel emerged victorious, according to Nasser himself. When the war ended, Abba Eban made a speech at the Special Assembly of the United Nations on 19th June. He claimed that…

“… in recent weeks, the Middle East has passed through a crisis whose shadows darken the world. … Israel’s right to peace, security, sovereignty, economic development and maritime freedom – indeed its very right to exist – has been forcibly denied and aggressively attacked. This is the true origin of the tension which torments the Middle East. All other elements of the conflict are the consequences of this single cause. … Israel’s existence, sovereignty and vital interests have been and are violently assailed.”

Laqueur, p. 207

The Special GA was principally concerned with the situation against which Israel defended itself on the morning of 5th June. But Eban claimed that these events were not born in a single instant of time. Between the 14th of May and the 5th of June, Arab governments led and directed by President Nasser methodically prepared an assault designed to bring about Israel’s immediate and total destruction. In the following twenty years, there was little if any progress towards a solution to the Arab-Israeli conflict. No substantial efforts were made to mediate between the two sides, and there was a developing danger of ‘superpower’ involvement (i.e. the USSR), resulting in the transformation of a regional conflict into a potential global crisis. Many members of the UN at the GA in March 1957 had hoped and believed that a period of stability would ensue from the arrangements discussed there for non-belligerency, maritime freedom and immunity from terrorist attacks. These assurances were received from the US, France, the UK and Canada among other states from around the world. They induced Israel to give up positions in Gaza, the Straits of Tiran and Sinai. Looking back from 1967, it was obvious to Eban that, all along, the Arab governments had regarded the 1957 arrangements merely as a breathing space enabling them to renew their strength for a later assault.

In August 1967, the Washington correspondent of twenty-five years, I. F. Stone, published an essay in the New York Review of Books, surveying a special issue of Jean Paul-Satre’s Les Temps Modernes on the ‘Arab-Israeli Conflict’ which went to print just as the Six Day War broke out. It was entitled ‘Holy War’, tracing both the ethnic and religious rivalries of both the Jews and Arabs going back to ancient times. In it, he concluded, somewhat prophetically, that:

‘The path to safety and the path to greatness lies in reconciliation. The other route, now that the West Bank and Gaza are under Israeli jurisdiction, leads to two new perils. The Arab population now in the conquered territories make guerilla war possible within Israel’s own boundaries. And externally, if emnity deepens and tension rises between Israel and the Arab states, both sides will by one means or another obtain nuclear weapons for the next round.’

Laqueur, p. 326.

Stone explained that “as a Jew, closely bound emotionally with the birth of Israel,” he felt “honour bound to report the Arab side, especially since the U.S. press was so overwhelmingly pro-Zionist. He concluded his review with a telling, ironic observation:

‘If God as some now say is dead, He no doubt died of trying to find an equitable solution to the Arab-Jewish problem. … no voice on the Arab side preaches a Holy War in which all Israel would be massacred, while no voice on the Israeli side expresses the cheerful cynical view one may hear in private that Israel has no realistic alternative but to hand the Arabs a bloody nose every five or ten years until they accept the loss of Palestine as irreversible.’

Laqueur, p. 327.

Between Two Wars, 1967-73:

Any discussion of the current prospects for a ceasefire in Gaza, and a longer-term peace between Israel and the Arab countries has to begin by revisiting the history of the Middle East between the Six-Day War of June 1967 and the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Efforts to reach a peace settlement in those seven years were protracted, highly complicated and ultimately futile. All the many plans that were proposed – the Rogers plan, the Jarring plan and nameless others – seem now merely of interest to academic historians. The story of these negotiations is a melancholy one, not least for the question it raises of possible opportunities missed by the various parties to the conflict, especially Israel. Not that Israel ignored any genuine peace overture from the Arabs; there was none. But, as documented here, an interim accommodation might have been reached with Egypt alone, based on a demilitarisation of the Sinai, which might have lessened the likelihood of a new round of fighting.

In the period between the two wars, the role of the Palestinian organisations also became more significant as a means of galvanising Arab unity in support of the Palestinians. The Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) had effectively come into being with the drawing up of the National Covenant or manifesto in May 1964, superseding the earlier Draft Constitution. The PLO was the biggest of the Palestinian refugee organisations; its manifesto was modified in several ways and at various times since 1964. The Al Fatah ‘Seven Points’ and the interview with Yaser Arafat, quoted below, were both published in 1969. These offer more recent interpretations of the organisation’s aims. The second of the Seven Points emphasised that:

“Al Fatah, the Palestine National Liberation Movement is not struggling against the Jews as an ethnic and religious community. It is struggling against against Israel as the expression of colonisation based on a theocratic, racist and expansionist system and of Zionism and colonialism.”

Laqueur, p. 372.

In his interview, published in Free Palestine, Yasir Arafat was asked about his movement’s call for the creation of a progressive, democratic state for all, and whether this aim was compatible with the slogan, “Long live Palestine, Arab and Free”. Arafat responded that there was no contradiction between the overall aim for a ‘state for all’ and ‘that state being Arab’. He added that:

“Anyone who has tried to look at the Palestinian problem in its historic perspective would realise that the Zionist State has failed to make itself acceptable because it is an artificially created alien state in the midst of an Arab world.”

Laqueur, p. 373.

He claimed the word ‘Arab’ simply implied a common culture, a common language and a common background, and that therefore the majority of the inhabitants of any future State of Palestine would be Arab since there were 2.5 million Palestinian Arabs of the Muslim and Christian faiths and another and another 1.25 million Arabs of the Jewish faith who lived in what was then the state of Israel. Only a democratic state of Palestine, he said, would guarantee equal rights to all its citizens, regardless of race or religion. To achieve this, the Palestinian organisations wished to ‘liberate the Jews from Zionism’ and to make them realise that the purpose behind the creation of the State of Israel, namely to provide a safe haven for the persecuted Jews, had instead thrown them into a ghetto of their own making.

General Dayan’s speech presented Israeli viewpoints on both the short-term issues involved in the continuing conflict and the longer-term perspectives on it. Moshe Dayan’s address, which he gave to a graduating class at the Israel Army Staff and Command College (reported in the Jerusalem Post on 27 September 1968) focused on what he called ‘the problematics of peace’. After a long survey of the history of Zionism in the 1920s and ’30s, based on the writings of Arthur Ruppin, one of the architects of the Zionist venture, known more generally as “the father of Zionist settlement” in the period 1920-42, Dayan concluded:

“… a year after the war, and despite the fact that we are standing on the Suez Canal and on the River Jordan, in Gaza and in Nablus; despite all our efforts – including a willingness for far-reaching concessions – to bring the Arabs to the peace table – the things which Ruppin said thirty-two years ago still seem sound. It was during the 1936 riots that he wrote:

‘The Arabs do not agree to our venture. If we want to continue our work in Eretz Israel against their desires, there is no alternative but to be in a state of continual warfare with the Arabs. This situation may well be undesirable, but such is the reality.’ ”

Laqueur, pp. 444-445.

The Six-Day War and its aftermath also raised questions for the Arabs and stimulated them to reassess their progress in the conflict. They began to grapple with the question of their objective in the conflict. But there was, as yet, no significant support for a recognition of the state of Israel. This line of thinking was dismissed in the late 1960s as a dangerous delusion by those who claimed to understand Arab political psychology. Such wrestling as took place was primarily concerned with the slogan “Democratic Palestinian State”. Later, it appeared that the terrorist organisations were actually afraid of a more flexible approach, lest it put them out of business. Yasir Arafat, writing in retrospect, commented:

“After the 1967 defeat, Arab opinion, broken and dispirited, was ready to conclude peace at any price. If Israel, after its lightning victory, had proclaimed that it had no expansionist aims and withdrawn its troops from the conquered territories, while continuing to occupy certain strategic points necessary to its security, the affair would have been easily settled.”

Yasir Arafat, quoted in John K. Cooley (1973), Black September (New York), p. 99.

Arafat was, as usual, exaggerating for effect: The affair would not have been easily settled. Still, there was a chance that de-escalation might have worked, and the truth is that those opportunities which did exist were not explored. The reasons for this were manifold. Deep down the Israelis had always inclined toward a ‘worst-case’ analysis of their situation, arising perhaps from an understandable determination (given then-recent Jewish history) not to take any risks with their citizens’ lives. Arab leaders, as already noted, had threatened Israel with extinction for many years, and following two major existential wars in twenty years, these threats could not easily be dismissed as idle. When, in the wake of the Six Days’ War, the Arabs officially opted for a policy of immobility at the Khartoum Conference (“No peace, no recognition, no negotiation”) it was only natural for Israel to react accordingly. Any other course would have been interpreted as evidence of weakness, and it was well-known that Arabs respected strength alone.

From a military and security point of view, the 1967 armistice lines seemed ideal. Before the war, Jordanian territory had extended to within 30km of Tel Aviv, Egyptian territory to within 80km; now the Egyptians were many hundreds of km away, and the Jordanians were beyond the Jordan River. Israeli planes could reach Cairo within a few minutes, so a good case could be made for not withdrawing from these lines. However, no one in Israel expected all the territories taken in the Six Days’ War to be retained, at least not at first. Immediately after the war, Moshe Dayan came out against an Israeli presence on the Suez Canal, Abba Eban warned against “intoxication with victory,” and David Ben-Gurion reiterated that a strong army, although vital, was no substitute for a political solution which in his view should include the return of the West Bank under agreed terms and a mutually satisfactory settlement of the Sinai issue. As time went on, Moshe Dayan, Golda Meir, Israel Galili and other Israeli leaders became increasingly pessimistic about the prospects for a comprehensive peace settlement.

Meanwhile, among the self-appointed leadership of the Palestinians, there was also some reflection and re-thinking. In the weekly supplement of the Beirut newspaper al-Anwar (8 March 1970), a long symposium was published concerning the meaning of the slogan, “The Democratic State,” in which the views of most of the prominent fedayeen organisations were represented. A translation of extracts from this symposium is quoted below:

“Co-existence with this entity (Israel) is impossible, not because of a national aim or… aspiration of the Arabs, but because the presence of this entity will determine this region’s development in connection with world imperialism, which follows from the objective link between it and Zionism. Thus, eradicating imperialist influence in the Middle East means eradicating the Israeli entity. This is something indispensible, not only from the aspect of the Palestinian people’s right of self-determination, and in its homeland, but also from the aspect of protecting the Arab national liberation movement, and this objective can only be achieved by means of armed struggle. …

“The liberation of Palestine will be the way for the Arabs to realise unity, … The unified State will be the alternative to the Zionist entity, and it will be of necessity democratic, as long as we understand beforehand the dialectical connection between unity and Socialism. In the united Arab State all the minorities – denominational and others – will have equal rights…”

Laqueur, pp. 535-6.

The intention, therefore, was not to set up a Palestinian State as an independent unit, but to incorporate it within a united Arab State which would be democratic because it was progressive, and would grant the Israeli Jews minority rights. Others, however, like Shafiq al-Hut, a leader of the PLO and head of its Beirut office, were not at all interested in guaranteeing Jewish minority rights:

“… there is no benefit in expatiating upon the slogan “Democratic Palestinian State.” … As far as it concerns the human situation of the Jews, … we should expose the Zionist movement which brought you to Palestine did not supply a solution to your problem as a Jew; therefore you must return whence you came to seek another way of striving for a solution for what is called “the problem of the persecuted Jew in the world.” As Marx has said, he (the Jew) has no alternative but to be assimilated into his society. …

“Let us face matters honestly. When we speak simply of a Democratic Palestinian State, this means that we discard its Arab identity. I say that on this subject we cannot negotiate, even if we possess the political power to authorise this kind of decision, because we thereby disregard an historical truth, namely, that this land and those who dwell upon it belong to a certain environment and a certain region, to which we are linked as one nation, one heritage and one hope . Unity, Freedom and Socialism. …”

Laqueur, pp. 536-7.

The implication that the Israeli Jews would be allowed to stay in the Democratic State raised distinct difficulties concerning its Arab character. For al-Huq, this was simply a strategy to gain international recognition for the PLO and the Palestinian cause:

“If the slogan of the Democratic State was intended only to counter the claim that we wish to throw the Jews into the sea, this is indeed an apt slogan an effective political and propaganda blow. But if we wish to regard it as the ultimate strategy for the of the Palestinian and the Arab liberation movement, then I believe it requires a long pause for reflection, for it bears on our history, just as (on) our present and certainly our future.

Laqueur, p. 537

A representative of the Syrian fedayeen organisation, as-Sa’iqa, was among those who had thought five years earlier that we must slaughter the Jews. But he now thought it impossible to slaughter even one-tenth of them. That being so, he asked, what shall we do with these Jews? He did not have a ready answer:

“It is a problem which every Arab and Palestinian citizen has an obligation to express his opinion about, because it is yet early for a ripe formulation to offer the world and those living in Palestine.

Laqueur, p. 537.

The slogan of the “Democratic State” was offered to the PLO as an escape from the odium that Article 6 of the 1968 Covenant had brought upon it. It seemed that the difficulties in which the idea of the Democratic State was enmeshed, as expressed in the internal controversies of this symposium, explains why the Covenant was not amended, despite the damage to the Palestinian cause. Nevertheless, the slogan was hailed by Arab statesmen as an all-important innovation demonstrating the liberal-humanitarian nature of the Palestinian movement. Yasir Arafat, seeking to strengthen this impression, even said that the President of the new state could be Jewish. However, scrutiny showed that it was not envisaged as a liberal-democratic state sharing Western values.

The objective of setting up a ‘Democratic Palestine’ was, however, enshrined in the resolution of the Eighth Palestinian National Assembly of early March 1971. The resolution was carefully worded to avoid promising that all Israelis would be allowed to stay, but that the state would be based on equality of rights and obligations for all its citizens. This was quite compatible with the quantitative limitations of Article 6 in the 1968 Covenant. Neither was this a new nomenclature, since autocratic régimes had, since 1945, described themselves as ‘democratic’ or ‘people’s republics’. The Congress that set up the “All-Palestine Government” in Gaza and which unanimously elected the former genocidally anti-Jewish Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husaini, as its president, had proclaimed on 1st October 1948 ‘the establishment of a free and democratic sovereign state’ in which ‘the citizens will enjoy their liberties and their rights.’ But although the slogan was not widely used among Arabs in the later seventies, it was not discarded, as the alternative would have been to fall back on the previous genocidal position. Nevertheless, there were those, especially among the Lebanese Palestinians, who continued to advocate “the complete eradication of the State of Israel.”

Even if the slogan of the “Democratic State” had been free of inconsistency and insincerity, the Israelis believed that they had no less a right to national self-determination than the Palestinian Arabs. They had no wish to become Palestinians of Jewish faith; they wished to remain Israelis. As long as the Arabs were unwilling to talk, Israel had to stand fast. A growing reluctance was felt even to discuss the possible terms of a settlement. The general attitude became that the Arab-Israeli conflict, like every other conflict in history, had to run its full course. At some time in the future, when the Arabs would be psychologically ready to accept the existence of Israel, it would be possible to find mutually accepted solutions to all the outstanding questions, but for the time being Israel had to stand firm. This policy had much to commend it, but it also had several major flaws. It ignored the fact that the Arab-Israeli conflict was not purely regional in character and that with regard to the two superpowers involved, an asymmetry existed between US support for Israel and Soviet support for the Arabs: America had to consider other interests in the Middle East whereas the Soviet Union could give all-out assistance to its clients. The USA underrated the effective force of the Arab armies built up by the Russians since 1967.

The Yom Kippur War, October 1973:

The early seventies was a period of both rivalry and ‘détente’ in USA-USSR relations, both of which influenced the next ‘chapter’ in the conflict. The Americans also overrated détente and, above all, it did not take into consideration the growing importance of oil as an economic weapon as a means of isolating Israel on the international scene: as far as Western Europe and Japan were concerned, Israel Israel was expendable but Arab oil was not. The international constellation, in brief, was changing, and not in Israel’s favour. A major power might have stood by and watched these changes with some degree of equanimity; a small country did so at its peril. But Bernard Lewis argued in an essay originally written for Foreign Affairs, that the two main axes of the East-West rivalry and the Arab-Israel conflict, while likely to persist, were not necessarily connected. Towards the end of the “fourth round” of the conflict, on 16th October 1973, the Egyptian President, Anwar Sadat made a speech to the People’s Assembly in Cairo in which he dealt with the prehistory of the war and Egypt’s relations with the Soviet Union and the United States and provided the official Egyptian version of the last phase of the war after Israeli troops crossed the Suez Canal:

“I shall not be exaggerating to say that military history will make a long pause to study and examine the operation carried out on 6th October 1973 when the Egyptian armed forces were able to storm the difficult barrier of the Suez Canal which was armed with the fortified Bar Lev Line to establish bridgeheads on the east bank of the Canal after they had… thrown the enemy off balance in six hours.

“The risk was great and the sacrifices were big. However, the results were achieved in the first six hours of battle in our war were huge. The arrogant enemy lost its equilibrium at this moment. The wounded nation restored its honour.”

Sadat’s speech, 16 October, 1973, Laqueur. p. 464.

The Yom Kippur War began with a concerted attack on two fronts. However, the aggressive initiative by Egypt was broken by the strength of Israel’s Defence Force. Both Egypt and Syria were thrown back, portions of their forces were destroyed and the IDF broke through their front lines and went on the offensive. After the Arab attack, it was noted in Israel that the strategic depth offered by the Sinai was in fact a lifesaver; had the attack been launched from the pre-June 1967 lines it would have threatened Israel’s very existence. But this emphasis was based on the assumption that the 1967 borders were the only feasible alternatives to the Bar Lev Line, when in fact a demilitarized Sinai might have functioned as a more effective warning zone than did the Suez Canal. Nor can it be taken for granted that Egypt’s attack in itself was inevitable, since the country was facing a great many problems at home and abroad, and had some sort of interim agreement been reached on the Sinai, the Egyptians might not have felt such an overriding urgency to recover all the lost territories.

Similarly, a settlement might have been reached with Jordan, though not with Syria, but the latter, acting in isolation could not have caused a great deal of damage. The same applies to Al-Fatah and its rival groups, who would have kept up their sporadic attacks from across the border and the hijacking of planes in any case. In due course, however, the Palestinians might have come to see that they could no longer rely on the Arab governments in their struggle and they too might have to come to accept the existence of the state of Israel.

For Sadat, however, the great mistake Israel continued to make was that its leaders thought that ‘the force of terror could guarantee security’. He claimed that the futility of this theory had been proven on the battlefield and the current Israeli command was acting in opposition to history. Peace could not be imposed; the peace of a fait accomplit could not last and could not be established through terror:

“Our enemy has persisted in this arrogance for the past twenty-five years – that is since the Zionist state usurped Palestine.

“We might ask the Israeli leaders today: Where has the theory of Israeli security gone? They have tried to establish this theory once by violence and once by force in twenty-five years. It has been broken and destroyed. Our military power today challenges their military power. They are now in a long protected war. Their hinterland is exposed if they think they can frighten us by threatening the the Arab hinterland. I add, so they may hear in Israel: We are not advocators of annihilation, as they claim. …

“The world has realised that we were not the first to attack, but that we immediately responded to the duty of self-defence. We are not against but are for the values and laws of the international community. We are not warmongers but seekers of peace. ”

Idem., Laqueur, pp. 466-469.

In his speech, Sadat set out a five-point peace plan which he addressed specifically to President Nixon:

“(1) We have fought and will fight to liberate our territories which the Israeli occupation seized in 1967 and to find a means to retrieve and secure respect for the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people. …

(2) We are prepared to accept a cease-fire on the basis of the immediate withdrawal of the Israeli forces from all the occupied territories, under international supervision, to the pre-5th June 1967 lines.

(3) We are prepared, as soon as the withdrawal from all these territories has been completed, to attend an international peace conference at the United Nations, … laying down rules and regulations for peace in the area based on the respect of the legitimate rights of all the peoples of the area.

(4) We are ready at this hour … to begin clearing the Suez Canal and to open it for world navigation…

(5) … we are not prepared to accept any ambiguous promises or loose words… What we want now is… clarity of aims… and of means.

Laqueur, p. 470.

On 22 October, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 338 which called upon all parties in the conflict to cease firing and terminate all military activity immediately, no later than twelve hours after the moment of the adoption of this decision, in the positions they now occupy. It also called upon the parties concerned to implement the 1967 cease-fire Resolution 242, which meant a return to Israel’s borders prior to the Six Days’ War, and the giving up by Israel of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. Finally, it called for immediate negotiations to start under appropriate auspices aimed at establishing a just and durable peace in the Middle East.

The next day, Golda Meir made a statement to the Knesset announcing that the Government of Israel had unanimously decided to announce its readiness to agree to a cease-fire according to the UN Security Council’s resolution following the joint USA-USSR proposal. The military forces would therefore hold to their positions at the time that the ceasefire came into effect. This allowed Israel to hold onto lines on the Syrian front which were better than those held on 6th October, giving it a strong northern flank along the Hermon ridge. The Syrian government did not immediately accept the cease-fire resolution, continuing to fight on. Also, although the Egyptians had gained a military achievement in crossing the Suez Canal, the Israel Defence Forces had succeeded in regaining control of part of the Eastern Canal line, as well as a large area west of the Canal, depriving the Egyptian army of its capacity to constitute an offensive threat in the direction of the Sinai and Israel, preventing it from attacking essential installations or areas of Israeli territory.

According to Meir, only a few days had passed after what she called his ‘boastful address’ on the 16th before Sadat agreed to a cease-fire, but not one of the conditions raised by him in his speech (above) was included in the SC resolution. However, his first point was directly referred to, if not as a condition of the cease-fire, in the resolution. Firing on the Egyptian front did not immediately cease, and it wasn’t until 31 October that Egypt’s President gave a press conference in Cairo at which he justified his decision to accept a cease-fire. He said that he had not decided to fight America, but had fought Israel for eleven days. On the Israeli side, following the end of the war, a commission was appointed by the Knesset, to investigate why Israel was taken by surprise on 6th October 1973 and the setbacks suffered during the first days of the war. This commission prepared a detailed report of which only a small portion was published.

Meir also pointed out that since the outbreak of the war on Yom Kippur, the ‘terrorists’ had also resumed activities from Lebanese territory. Up to the morning of her speech, during the period of seventeen days, 116 acts of aggression had been perpetrated, forty-four civilian settlements on the northern border had been attacked and shelled, and some twenty civilians and six soldiers had been killed or wounded by these actions. She commented:

“Our people living in the border settlements may be confident that Israel’s Defence Forces are are fully alert to this situation. Despite the defensive disposition operative on this front, it has been proved once again that defensive action alone is not sufficient to put an ends to acts of terror.”

Laqueur, p. 486.

On both main military fronts, the Israeli forces were holding strong positions beyond the cease-fire lines. However, Meir insisted that Israel wanted a cease-fire and that it would observe the cease-fire on a reciprocal basis, and only on that basis. Israel wanted peace negotiations to start immediately and concurrently with the cease-fire and was willing to support and promote an honourable peace within secure borders. With the end of the 1973 war came a new willingness in Israel to rethink the Arab-Israeli conflict, and to consider new ways of resolving it. A spate of articles and speeches, symptomatic of the confusion caused by war, suggested all kinds of panaceas: a National Security Council, a mutual defence pact with the US, a “charismatic minister of information.”

Searching for Peace in Algiers & Geneva, 1973-75:

Only after an interval of several weeks were serious attempts undertaken to analyse the lessons of the October War in a broader perspective and greater depth. This soul-searching coincided with the electoral campaign in which both parties clarified their policies looking forward. The right-wing Herut claimed that the people of Israel had won a magnificent victory on the battlefield and should not have to pay for the defeat of the Western world in the oilfields of Arabia; but Herut also denied that it was a ‘war party’, asserting that it was much better equipped than the Labor coalition to lead Israel towards peace. The Liberals, Herut’s partners in the Likud coalition, advocated a more moderate line, suggesting Israeli concessions in return for peace; they debated among themselves whether these concessions should be spelt out or not. The Labor alignment had to accommodate conflicting trends in its declared policy, set out in its fourteen points. The preamble to these stated: “Our platform must reflect the lessons of the Yom Kippur War.” Their platform insisted on defensible borders based on a territorial compromise, but they did not support a return to the June 1967 boundaries. A peace agreement with Jordan would be based on the existence of two independent states: Israel, with Jerusalem as its capital, and an Arab state to the east; efforts would be made to continue settling Israelis in the occupied territories, ‘in keeping with cabinet decisions giving priority to national security provisions.’ This represented a concession to the “hawks” in the Labor alignment, but the ‘platform’ as a whole constituted a decisive victory for the “doves.”

Almost simultaneously, the Arabs were making their demands known at the Algiers meeting of the Arab heads of state. They stated that the struggle against the “Zionist invasion” was a long-term, ongoing responsibility which would call for many more trials and sacrifices. A cease-fire was not peace, which would come only when a number of conditions had been met, two among them paramount and unequivocal: first, the evacuation by Israel of all occupied Arab territories and above all Jerusalem; second, the re-establishment of full national rights for the Palestinian people. Yet inasmuch as no objections were voiced to negotiations with Israel, something that the 1967 Khartoum Conference had expressly rejected, it appeared to many observers that the ‘moderate’ line of President Sadat had won out in Algiers. The final communiqué stated that the meeting had been a great success, but since Iraq and Libya boycotted the conference, and Syria subsequently decided not to participate in the Geneva Conference at all, Arab unity could by no means be said to be complete.

Yasir Arafat’s speech at the UN General Assembly on 13 November 1974 restated the PLO’s case for a future State of Palestine. In his speech, Arafat stated: “We include all Jews now living in Palestine who choose to live with us there in peace and without discrimination.” But as the weeks passed, the Algiers resolution was shrilly rejected by Arab extremists. A broadcast emanating from Baghdad on 21st December 1973, the day the Geneva talks opened, announced:

“The masses will not be bound by the régimes of treason and defeatism at the Geneva Conference. “

Radio Tripoli asked:

“Has our Arab nation become so servile in the eyes of those leaders (i.e. Sadat) that they belittle its dignity and injure its pride without fearing its wrath?”

Israel’s ‘khaki election’ took place on the last day of the old year. If public opinion polls published in September 1973 were to be trusted, the results would have been similar even had the war not taken place. The Labor alignment, deeply split and under fire from within not only because of the military handling of the war but for the lack of flexibility shown by Golda Meir’s inner circle in recent years, lost ground. Were it not for the obvious necessity to preserve the unity of the alignment in view of the international situation, it is quite possible that both Mrs Meir and General Dayan would have had to resign under pressure from large sections of their party. But Likud had no reason to be overjoyed by the results of the elections either; if the party of Menahem Begin could not overtake its rivals in such nearly ideal conditions, it never would – unless, of course, the Labor alignment should disintegrate entirely. The campaign was confused and in the absence of a clear choice between the potential leaders, the outcome of the elections was bound to be inconclusive. Therefore, no clear mandate emerged for any one course of action. The absence of a consensus and the sharp polarisation of public opinion made the task of the Israeli negotiators beyond the first stage of the talks extremely difficult. The effect of the vote, the London Economist wrote, was to block any government from making the vital decisions that the Geneva talks demanded.

The Algiers summit conference proclaimed that the war aim of the Arab states was the restoration of the national rights of the Palestinian Arabs, that the PLO was the only legal representative of the Palestinians, and that its interpretation of the ‘national rights’ was binding. That interpretation was, in turn, laid down by the Palestinian National Covenant of July 1968, which claimed that the establishment of Israel was ‘null and void’. The Algiers resolution, in other words, as much as stated that the purpose of any peace conference would be to discuss the liquidation of Israel. In the eyes of some, this meant that it was pointless for Israel to attend the Geneva Conference. However, it opened on 21st December in an atmosphere of cautious optimism. Dr Kissinger, in his opening speech, spoke of a “historic chance for peace”; there were also promising noises from Jerusalem, Moscow and Cairo. All this was based, no doubt, on the undisputed fact that immediately after a war, the prospects almost always seem acceptable after all.

In its first phase, the Conference concentrated on achieving a lasting peace between Egypt and Israel. Troop disengagement was achieved in an agreement on 17th January. The Israel-Egypt ‘problem’ did not, at first, seem insurmountable. If Egyptian sovereignty over Sinai were recognised and Egypt was to accept an effective system of demilitarisation, there would then only be the remaining territorial issues. Neither side was particularly eager to accept responsibility for Gaza, though neither would admit it. Israel, however, would not agree to withdraw from Sinai in return for a mere armistice. Egypt has assured its Arab allies that it would under no circumstances make peace with Israel unless it withdrew from all occupied Arab territories and the national rights of the Palestinians were restored. The official interpretation of this formula would however mean the liquidation of the state of Israel. Nevertheless, there were several other interpretations possible.

For twenty-five years Egypt had borne the brunt of the struggle against Israel, yet pan-Arab feeling was less deeply rooted in Cairo than elsewhere in the Arab world. In its struggle against Israel, Egypt had received a great deal of verbal aid and unsolicited advice, but when it came to making war, as in October 1973, it received little practical support from its Arab ‘friends’. Syria and Iraq harboured strong feelings of resentment against Egypt, seeing themselves as the rightful leaders of the Arab world. Colonel Qaddafi of Libya had also, on many occasions, decried Egypt’s “decadence” and “corruption”. For their part, the Egyptians regarded Syria and Iraq as semi-barbaric lands and had always held a contemptuous view of the Palestinians.

There was thus a strong inclination inside Egypt, after the Yom Kippur War, to put Egyptian interests first. The Six Days’ War had come as a great shock to the country as a whole, and there was universal agreement that the shame of 1967 had to be expiated on the field of battle. But with these aims achieved, Egypt no longer needed to feel an overriding obligation to champion the further struggle against Israel. Hundreds of articles and dozens of books had been published in Egypt all proclaiming the inadmissibility of a Jewish state in the Middle East, but these declarations could not necessarily be taken at face value. The prospect of many more years of hard fighting and severe damage to the country had little appeal. It should have been Israeli policy after 1967, and especially after Nasser’s death in 1970, to concentrate on a separate deal with Egypt, but the country was desperately poor and financially dependent on Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf states. These countries had a vested interest in prolonging the struggle with Israel, which was tantamount for them to an insurance policy against the radical forces in the Arab world that threatened their own existence.

Sadat’s position was stronger after the Yom Kippur War, certainly, but an Egyptian-Israeli deal was unlikely to mark even the beginning of the end of the Arab-Israeli conflict, and in the event of a new flare-up, the danger would always exist that Egypt might be drawn into the campaign. Finally, an opening to Egypt on Israel’s part would involve a basic psychological reorientation: since 1948 Egypt had been the enemy of Israel. But in the wake of the October 1973 war, the interests of the two countries were not necessarily incompatible, and normal, if not friendly, relations between them were not to be ruled out as a possible future at that time. It was by no means unthinkable that one day Israel would break out of its isolation and align itself with one or more of the Arab countries against one or more of the others. If a settlement with Egypt entailed grave risks, the other alternatives were even more dangerous. One was to give up nothing, the other was to tackle the problem at its core and strive for a settlement which would satisfy the Palestinian Arabs.

The hard-line Israelis argued that a renewed war would involve a protracted and strenuous struggle, but Israel would eventually win and this time its victory would be decisive. A more sophisticated version of this argument was one that maintained that it would be fatal for Israel to act “reasonably” and “responsibly” in the then-current situation, as it was being urged to do on all sides. On the contrary, Israel should be tough, unpredictable and, to a certain extent, irresponsible. This reasoning could not then be dismissed out of hand, but the chances of such a policy being successful in the real world could not, then or now, be rated very high. It underestimated the extent of Israel’s reliance on the United States and exaggerated the American readiness to help Israel in the future. But even more decisively, it was not a policy that the government of a democratic policy could easily pursue.

Others also argued that any Israel withdrawal would be just the first step in the gradual dismemberment of the country as a whole by its Arab neighbours, it would of course be preferable in every respect to make a stand now, rather than later when the boundaries would be harder to defend. Israel was already isolated, according to this view, and there was no further point in trying to appease world opinion by capitulation. The US, in the last resort, could be counted on to remain steadfast, for its prestige was deeply involved and Israel was already, by then, a cornerstone of its foreign policy. This line of thought, if put into action, would almost certainly bring about a new war in the Middle East, perhaps within a few months, for Sadat remained under considerable domestic pressure either to show results or to renew the fighting.

The alternative of reaching an accommodation with the Palestinians was in every way the most ideal solution. If an agreement could be reached on the basis of the establishment of a Palestinian state on the West Bank, Israeli willingness to take back some refugees and the resettlement elsewhere of those for whom a home could not be found, an end would be put to the conflict once and for all. The fate of the Palestinian Arabs was the heart of the matter; without a solution to this issue, there would be no resolution of the wider conflict. Unfortunately, however, the Palestinian issue was the most intractable of all the issues of contention between Israel and the Arab world. A Palestinian state would be economically unviable and the policy of such a state would be dictated not by the forces for peaceful co-existence, but by radical elements who would use the West Bank as a base for the continuation of the armed struggle against Israel. The main Palestinian organisations, Fatah and the PLO denied the Israelis’ right to national self-determination, and their aim remained the destruction of the “Zionist state.” When they spoke of the democratic secular Palestinian State that would replace Israel, they meant, according to Laqueur, an Arab state in which Jews would have the right to be buried in their own cemeteries.

So the slogan of a ‘democratic Palestine’ could still not be easily reconciled with the demand to preserve the Arab character of the State, especially for the Israelis. In his (1970) article, The Meaning of a Democratic Palestinian State, which he republished in 1974, Y. Harkabi analysed this contradiction on the basis of discussions between leading members of the ‘Palestinian Resistance.’ He claimed that the ‘democratic solution’ was presented as a compromise between two chauvinistic alternatives – ‘a Jewish State, and driving the Jews into the Sea – as if these were two comparable propositions‘. Thus, the Geneva Conference could not bring a comprehensive peace settlement to the Middle East. But if the prospects for an overall peace were still remote, there did exist in 1974 – as in 1967 – an opportunity for defusing the conflict and rendering unlikely the renewal of fighting on a large scale. This was done by Israel, principally and eventually, meeting the basic demands of the Egyptians by withdrawing Israeli settlements from Sinai and recognising Egyptian sovereignty there, in exchange for demilitarisation.

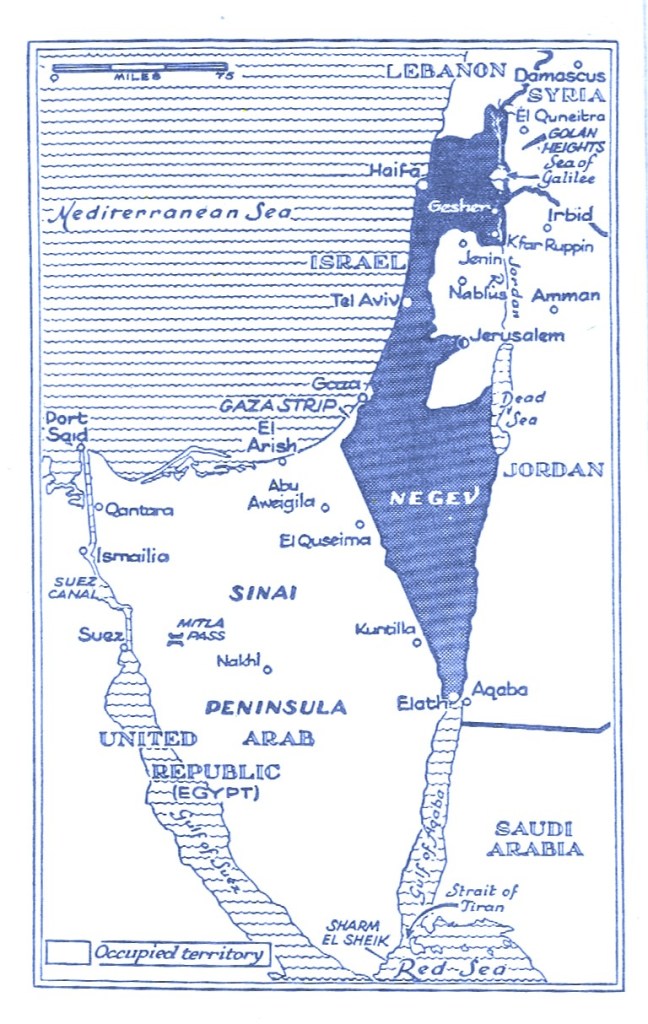

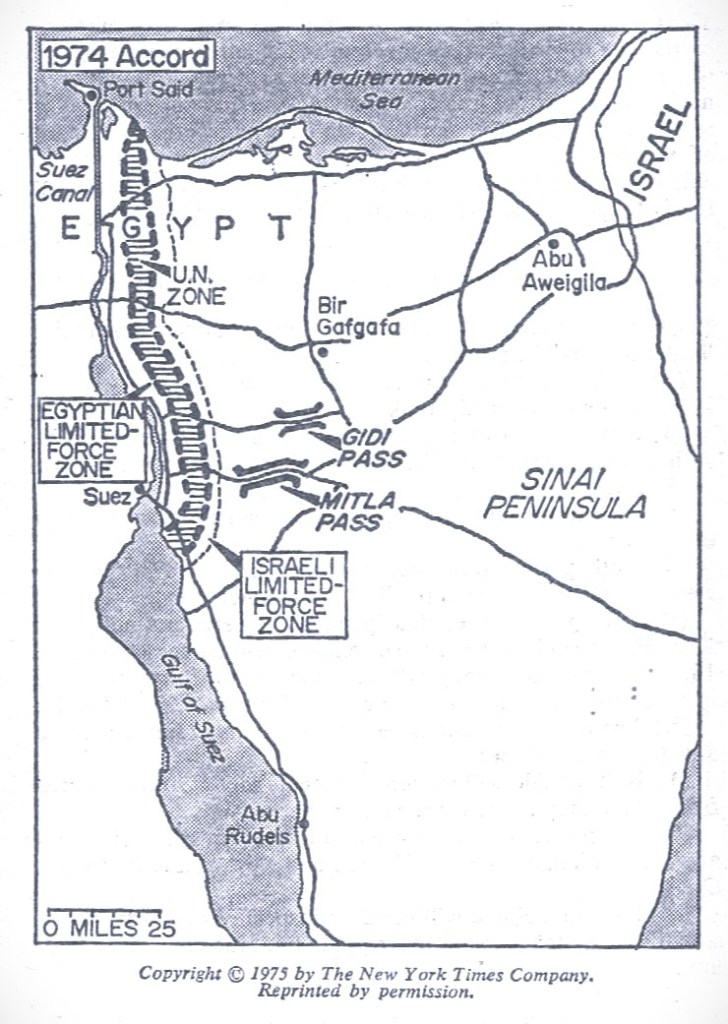

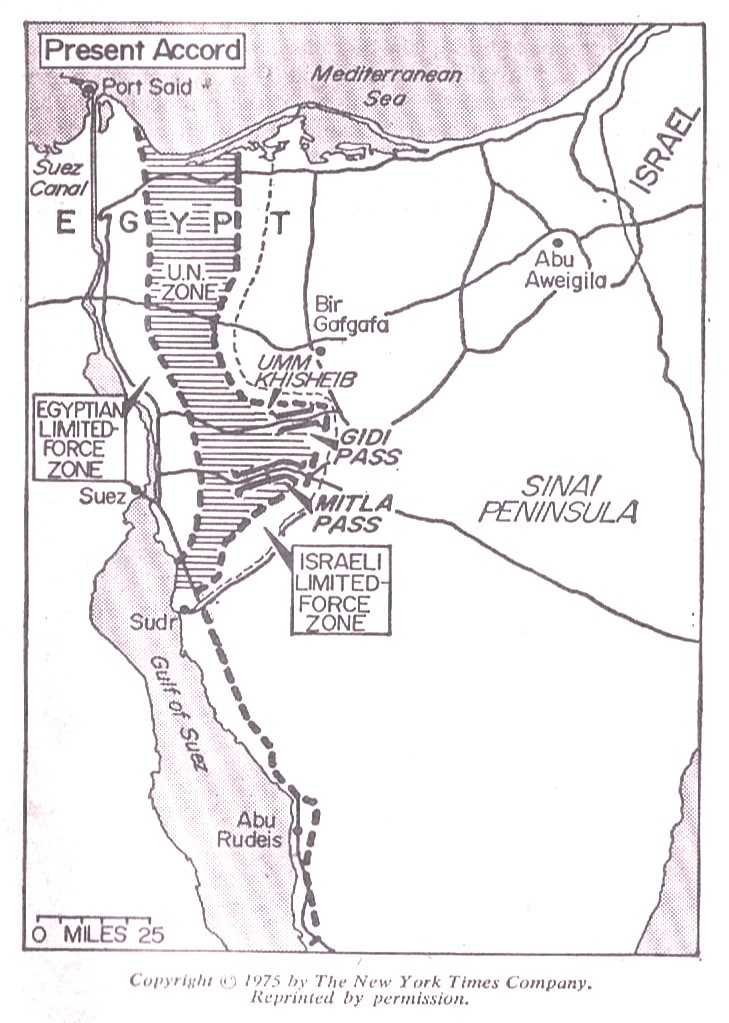

The agreement was concluded by the parties on 18 January 1974 within the provisions of Security Council Resolution 338 of 22 October 1973 and the framework of the Geneva Peace Conference. The maps below show the lines which would mark a buffer zone in which the United Nations Emergency Force would continue to perform its peacekeeping duties, and a demilitarized zone further south.

The Next Half Century:

This made less likely a new outbreak of hostilities and the imposition of a ‘peace’ dictated by the superpowers that would have been even more detrimental to Israel’s interests. In the subsequent years, fraught as they were with danger and requiring constant military preparedness and a high degree of diplomatic flexibility, the general outlook was not all that unpromising. As long as the “Zionist menace” overshadowed all other factors in the Arab political consciousness, a certain degree of unity prevailed in the Arab world. But as Israel assumed a lower profile, all the suppressed dissensions among the poorer Arab nations reasserted themselves.

The fact that some Arab countries were able to earn fabulous riches during these decades while others were not, exacerbated existing divisions. In addition, the oil-producing countries were becoming increasingly unpopular all over the world because of their extortionate oil policies. Given that some sort of détente managed to survive through the Second Cold War, the risk of an all-out Arab attack on Israel remained reduced. But in the final analysis, Israel’s fate continued to depend on its own policies and on its own inner character. It required unity, strong nerves and a readiness to compromise, combined with a firm resolve to repel any new threat to its existence. Somehow, this combination of strengths has helped to ensure its survival over the past fifty years.

Postscript – The Non-Arab Involvement:

Both ‘sides’ have now obtained nuclear weapons, though the situation has become complicated by Iran, not an Arab state, having replaced Egypt as the chief protagonist of the anti-Zionist and anti-Western coalition in the Middle East. So far, the ‘Western alliance’ has proved unable to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weaponry and the state of readiness of its programme is unknown. Iran’s clerical rulers have warned Israel of an escalation if it does not end its ‘offensive’ against the Palestinians. The country has traditionally backed Hamas and supports other militant groups including Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Main Source:

Walter Laqueur (ed.) (1976), The Israel-Arab Reader: A Documentary History of The Middle-East Conflict. New York: Bantam Books.