The attack on the Hannukkah Party on Bondi Beach near Sydney, Australia, has stunned the world and once again led to an outcry against anti-Semitism. However, the heartfelt sentiments expressed have so far failed to confront the deeply rooted causes of the disease, including the lack of understanding of Judaism as a worldwide religion and its adherents as the ‘biggest family on earth’, as Rabbi Ephraim Mervis, Chief Rabbi to the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth, has put it. Few people outside the faith have any knowledge of the nature or significance of the event beyond its place in the pantheon of religious Festivals of Light, which take place at this time in the inter-faith calendar. Those who express a desire to ‘do something’ in response to the tragedy which occurred on the first day of the event, 14th December, could do no better than educate themselves and their families about the meaning of the observance which was so cruelly interrupted on that day.

As a retired teacher of Religious Education, I am writing this post partly to refresh my own knowledge, which has faded over the forty years since I taught it as part of the RE curriculum in the first four years of my career in a Church school in Lancashire and in a more multi-cultural comprehensive school in Coventry. There, as in Birmingham, where I went to school, there was always a ‘sprinkling’ of Jewish students, though they were so well integrated that, unlike the Muslim, Sikh and Hindu students, we hardly recognised them as being of a different faith or ethnicity. The Greek Orthodox students, mainly Cypriot ‘refugees’, though Christian, were more visible, as they were generally keener to participate in activities celebrating Christmas and Easter. Endemic ‘racialism’ and anti-Semitism prevalent in Birmingham in the late sixties and early seventies meant that religious diversity was not celebrated as something to be encouraged in schools until I began teaching in the early eighties. School assemblies in the seventies were monolithically Anglican or Catholic in character or composition, often to the liturgical exclusion of nonconformist students like myself, a “blond Baptist waddling down the aisle” as the school choirmaster labelled me.

In recent decades, Religious Education seems to have been further marginalised, or absorbed by/ merged with ‘Citizenship’. Perhaps part of the current lack of mutual misunderstanding between ethnicities lies in the abandonment of interfaith and intercultural ‘training’ in schools and training colleges over the last three decades. Without this, true integration in society is made a far more difficult task. Many ‘millennials’ and ‘generation z’ students have left school with clear, if misguided, views of their human and civil rights, including ‘freedom of speech’, but without a deeper understanding of the deeper values of the Judaeo-Christian traditions which underpin society, even though it is now largely secular and post-Christian. ‘Toleration’, for example, a principle hard-fought for over eight generations or more by my ancestors in Britain, has faded into a vague idea of an attitude of ‘tolerance’, and concepts of societal ‘liberty’, balancing rights and privileges with responsibilities and obligations, have been replaced by purely personal, sometimes selfish, ‘freedoms’.

The colourful Jewish festival of Hanukkah (Chanukah), also known as the Feast of Lights, lasts for eight days from mid-December. The observance commemorates the re-dedication of the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 165 BCE. The hero of the story is Judas, one of the sons of Mattathias, head of a priestly family who lived near Jerusalem. At the time, there was a war between Egypt and Syria, with the Jews caught in between, a not unfamiliar situation for twentieth-century occupants of Israel-Palestine. The Syrian king, Antiochus IV, proclaiming himself Epiphanes, meaning ‘God made manifest’, a highly objectionable claim for the followers of Yahweh, wanted to extend the kingdom to include Judaea, the Jewish homeland. Although the importation of Hellenistic culture had led to the translation of the Jewish Bible into Greek, opening up Judaism to the Greek world, a fusion between Hebrew culture and Hellenism was impossible because of the Jewish commitment to the Word of God and the Laws set down in the Torah. It was this loyalty to the Word that prevented Jewish identity from being subsumed within Hellenism.

The forces of Antiochus raided the city of Jerusalem, plundering the houses and desecrating the Holy of Holies in the Temple. He set up his own citadel overlooking the Temple, which he rededicated to Zeus, the heathen God of the Greeks. The tyrant then began a campaign to unify his empire and rid the region of all semblances of Judaism, banning the practice of circumcision. But the Jews resisted stubbornly and looked for a hero to restore their Temple and the observance of their religion. Help came from Mattathias and his five sons, in particular from Judas, who was later given the title of Maccabeus, meaning ‘The Hammer’ or ‘Extinguisher’ because of his exploits.

One of the first signs of revolt against Antiochus was an incident in the Temple, when Mattathias saw one of his own people, a Jew, preparing to take part in a service of sacrifice to Zeus. Mattathias struck him down and, turning on the Syrian guard, killed him. Mattathias and his sons fled to the hills, where they gathered around them a strong resistance movement. From there, Judas led raid after raid against the Syrians, making their occupation of Judaea more and more untenable and hazardous. In the midst of the fighting, Judas gathered his followers to observe the Jewish religious ceremonies, to watch and pray, and to read the Torah, the sacred Law.

In December 164 BCE, Judas and his followers recaptured the Temple and the priests reconsecrated the Holy Place, erecting new altars to the true God. The story goes that when the perpetual lamp of the Temple had to be re-lit, only one day’s supply of non-consecrated oil could be found, but miraculously, this oil lasted for eight days until a fresh supply could be brought. Resistance turned into open rebellion, and the Jews, led by the Maccabees, rose in revolt which established an independent Jewish state, ruled by a priestly order that lasted for almost a century, until the Romans took over from the Greeks and ruled the region as a province of the Roman Empire, with Herod the Great as their ‘puppet’ king. He rebuilt the Temple, extending its massive walls, until it became the ultimate expression of Jewish identity at the end of the first century BCE. Some, however, still clung to the Torah scrolls as the centre of their faith and left Jerusalem to continue their devotion to the Word in the rocky hills on the shores of the Dead Sea.

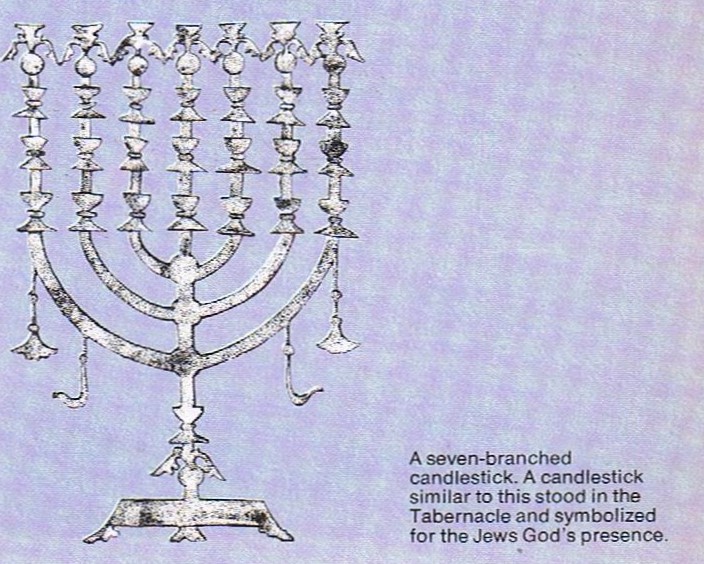

The story of the miraculous oil burning for eight days is why the festival now lasts for eight days and is commonly called The Feast of Lights. The day which sees the start of the festival is the twenty-fifth of Kislev (the ninth month), which can fall on any day in December and therefore falls while Christians are preparing for Christmas, sometimes coinciding with it. It is a family festival, largely observed within homes, in common with other Jewish festivals. Originally, presents of sweets or money, Hannukkah gelt, were given to children, but influenced by Christmas, there is more of an exchange of gifts, colourfully wrapped with surprises inside. The central part of the ceremony, as held at Bondi Beach, is the lighting of a candle on the eight-branched candelabra on the first day, with an additional candle lit on each of the seven successive days, recalling the eight days of light provided by the miraculous oil when the Temple was re-dedicated.

I pray that, as the Jews of Sydney and around the world light the remaining candles on their menorahs, they will feel the light of God’s countenance upon them. But those who murder in the name of the One God, the God of Abraham and Isaac, are apostates, and those who cry ‘from the river to the sea…’ and ‘death to Israel’ are anti-Semites, and must be stopped. The message of Hannukkah is one of eternal hope, that ‘out of darkness cometh light’. The Hannukkah story is emblematic of the whole, long story of the Jews, which, as Simon Schama has shown, is one of resistance, resilience and survival. Unfortunately, too many people allow the Light to pass them by, and some are too prejudiced to see it, preferring instead to stay in the darkness of intolerance and hatred of Jews and Judaism.

Sources:

Victor J Green (1983), Festivals and Saints’ Days: A Calendar of Festivals for the School and Home. Poole (Dorset): Blandford Press.

Simon Schama (2013), The Story of the Jews. BBC Video.