‘Forget not to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.’

‘Peidiwch ag anghofio llety-garwch, oherwydd trwyddo y mae rhai, heb wybod hynny, wedi rhoi llety i angylion.’

Y Llythyr at yr Hebreaid/ Letter to the Hebrews, chapter 13: 2.

Introduction – Providing Sanctuary:

In recent weeks and months, there has been much discussion in British newspapers and other media about ‘asylum seekers’, concepts of ‘sanctuary’ and processes of immigration and integration, including ‘family reunification’, a policy recently revoked by the Danish centre-left government. The new British Home Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, is reported to have sent a ‘task force’ to Denmark to assess the success of such policies, including restrictions on residency rights for asylum seekers, with a view to introducing them in the UK. In Britain, the daily arrival of hundreds of ‘asylum seekers’ or ‘illegal immigrants’ (depending on individual political perspectives) is causing serious social and political controversy both nationally and locally. This reminded me of events I was involved in almost fifty years ago as a student leader in South Wales, which I was recently invited to recall and record as oral evidence for a book written and published a few months ago (2025) by a research colleague, Alun Burge, providing…

… an impressionistic account of the Chileans who came to Wales, their long decade from 1973 to 1986, at the end of which most had returned, and relates something of the support provided by local people.

Alun has given me permission to share the personal accounts of those I knew best in their transcribed form, together with our mutual recollections and reflections on the events of the year 1979-80 in Swansea, when I was Cadeirydd (Chair) of the National Union of Students, Wales – Undeb Cenedlaethol Myfyrwyr Cymru. Therefore, what follows here is a series of extracts from Alun’s book (full details of which are given in the bibliography below), with further recollections of my own of that year when, as he remarks, a deep bond was formed between the Welsh hosts and their Chilean guests, the latter contributing to making Wales a more outward-looking and cosmopolitan place. The links between the two countries, especially those of Swansea, went back to the nineteenth century when the seaport town was a major centre of the global copper industry.

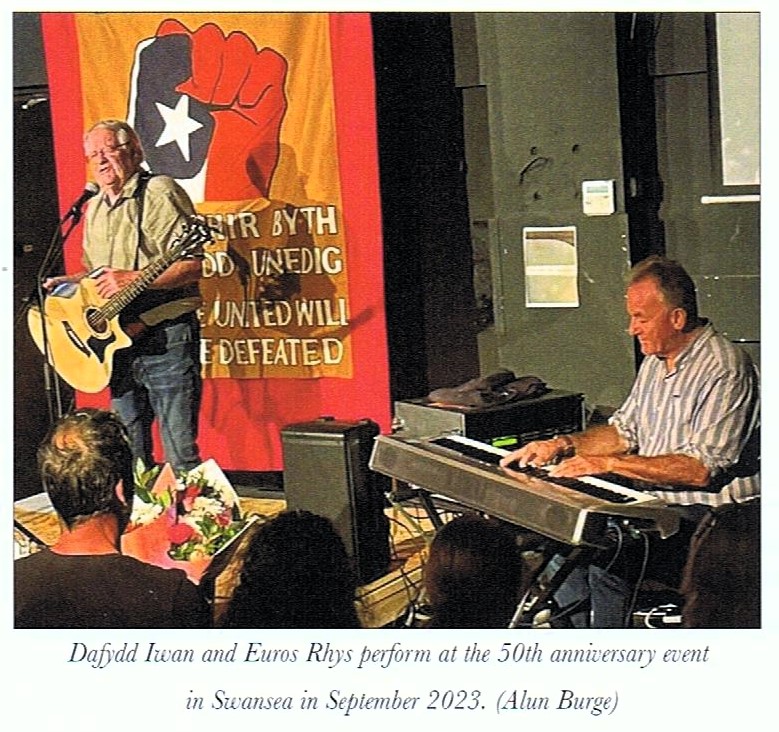

At the time the Chilean refugees were arriving in Wales, international causes, including Chile, were seen by the labour movement in Wales and Britain as a whole, were seen as a single fight against imperialism and for national liberation. Many of the people who were at the heart of the debate about the Welsh national movement and devolution were also centrally involved in organising solidarity with Chile and providing direct support to its political refugees. Chile was only one of the international issues supported by the people of Wales, especially its students, in the 1970s and 1980s (I was a student there from 1975 to 1983, with sojourns in Bangor, Cardiff, Swansea and Carmarthen, and obtained my PhD in History in 1989, before moving to Hungary). During my year as a sabbatical officer, UCMC was mockingly referred to by opponents as ‘NUS Chile and South Africa’. Although this labelling was generally unjustified and unjustifiable, I do remember one particular evening when, together with a Welsh MP, Dafydd Elis-Thomas, we divided our time between an Anti-Apartheid campaign meeting in Llanelli and a concert in aid of the Chile Solidarity Campaign in Swansea featuring a well-known Welsh language folk singer, Dafydd Iwan.

Santiago, 1973 (9/11):

On 11 September 1973, a military coup overthrew President Salvador Allende’s democratically elected Marxist government, bringing in the brutal dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. Left-wing political parties were banned, as was the Chilean Trades Union Congress; other political parties were declared to be ‘in recess’. Arrests of Popular Unity supporters and trade union leaders began immediately. The barbaric nature of the coup traumatised Chile and sent shockwaves around the world as news quickly emerged of activists being gaoled, tortured or killed. The National Football Stadium in Santiago was turned into a brutal concentration camp where the ‘New Song’ folk-singer Victor Jara was killed some days later, one of thousands to meet the same fate. It was estimated that over forty thousand people were illegally detained and tortured, and three thousand were murdered or simply disappeared.

The National Union of Students (NUSUK) condemned the coup and pledged its support for the Chilean people at its national conference in November 1973. It undertook to take action to secure the release of political prisoners and called for an end to the transfer of arms from Britain to Chile. It also pledged to work closely with the Chile Solidarity Campaign to expose the crimes of the junta. In April 1974, a three-person clandestine delegation went to Chile under the auspices of the International Union of Students, including Chris Proctor, who was President of the Swansea Union of Students in the summer of 1973 and a member of the NUSUK Executive. Alun Burge has recorded in some detail Proctor’s ‘desperate revelation’ of his experience of the week he spent undercover in Chile, which he reported to a NUS Conference.

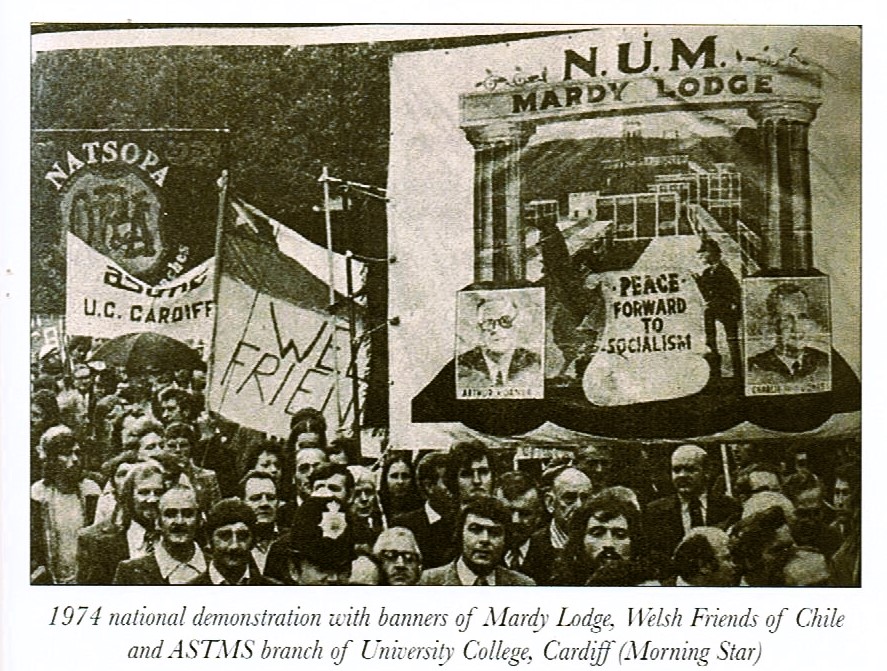

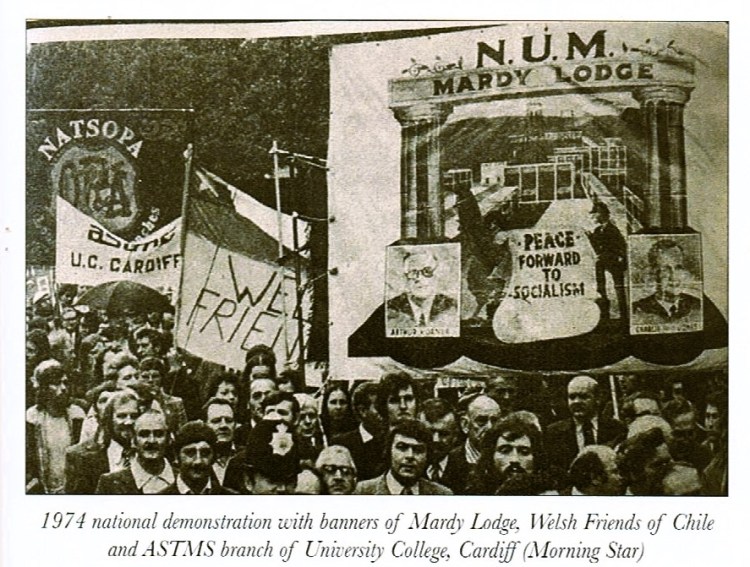

The National Union of Seamen in Cardiff, following a vote in the national (UK) union, instructed its members not to sail to or from Chile, an instruction its members upheld throughout the duration of the Pinochet régime. A protest march and open-air meeting in the capital was addressed by a young Welsh miner who had just returned from working in the Chilean copper mines. He spoke of the struggle the Allende government had faced and of his friends who were being murdered. A new group, The Welsh Friends of Chile, was launched to develop a broad political front with trade union sponsorship. In November 1973, the newly established Chile Solidarity Campaign (CSC) organised a national demonstration in London, and it soon became the key body in generating broad-based support for the Chilean ‘resistance’. Labour activists from across the Monmouthshire mining valleys established the South Wales Campaign for Democracy in Chile, joining together the Bedwellty, Caerffilli and Ebbw Vale constituency parties. Local South Wales MPs, led by Neil Kinnock, became involved, including Caerwyn Roderick, Leo Abse and George Thomas. The campaign also gained the support of the South Wales NUM and the TGWU Regional Committee. Will Paynter, the ex-General Secretary of the NUM, who had been a political commissar in the International Brigades in Spain in the 1930s, spoke at a rally in Ebbw Vale, when he said that the situation in Chile was the same struggle as his generation had faced in Spain and described the Heath government’s approach as the equivalent of the non-intervention policy of the National Government in 1936-39. The experience of the Basque refugee children who sailed from Bilbao and found a safe haven in Welsh families remained fresh in the collective memory of Wales in the 1970s.

Chilean Families Seeking Refuge in Swansea:

The refugees in Wales were part of an estimated two hundred thousand who were forced into exile by the Pinochet Junta, around two per cent of the country’s population. About three thousand went to Britain, with over half settling in London, and approximately 175 in Wales. The overwhelming majority of those who went to Wales were supported by WUS grants. There were 155 associated with University College, Swansea, comprising eighty-five WUS-sponsored Chilean scholars and almost as many spouses and children.

Chilean academic staff and postgraduate students began arriving in Britain in July 1974 through a voluntary initiative organised by Academics for Chile in collaboration with the World University Service (WUS), which expanded considerably when WUS received funding from the Labour government. WUS staff sought to place the student refugees in UK universities, and, once they were offered a place, WUS provided a grant. They were able to obtain a visa for them to study in the UK, and to settle with their immediate families (if necessary) in time for them to learn sufficient English to begin their courses at the beginning of the 1974-75 academic year in September. In addition to cajoling the Home Office to issue visas promptly, the local solidarity groups arranged for the reception of the refugees. WUS applied the language requirement loosely, so that most students arrived with very limited spoken English. In these early stages, funding was not available to pay for language classes, so the local groups had to arrange initial provision locally in addition to finding housing and helping to place the children in local schools. Ahead of the new academic year, the children were the priority for local supporters. In Swansea, many of those over eleven went to Bishop Gore Comprehensive School. Jane Elliot, one of the leading members of the, as yet informal, local support group, convinced the school to introduce Spanish into the school curriculum. Although there was some minor bullying, it was insignificant compared with what they had experienced in Chilean schools after the coup.

With the prospect of large numbers of Chilean refugees arriving in Britain, the Welsh Friends of Chile (affiliated to the CSC) convened a meeting in Swansea in March 1975 to consider both the immediate problem and to plan wider solidarity activity. A further meeting in Cardiff heard from the national secretary of the CSC, Mike Gatehouse, along with Gordon Hutchinson, who explained the role of the Joint Working Group for the Reception of Refugees from Chile (JWG). Those attending learned that although the Wilson Government’s policy was to provide asylum to thousands of refugees seeking sanctuary in Britain, the responsibility for helping them find accommodation and education fell to local solidarity groups. The following month, the situation changed dramatically, however, when the Junta introduced Decree 504, enabling political prisoners to have their sentences commuted to expulsion from the country without the possibility of return. This provided a much broader spectrum of people with the opportunity to leave Chile, offering a route for working-class activists to obtain a visa and ticket out. Nevertheless, arrangements for their release could take months, if not years, to come into fruition, especially for those who had been gaoled for longer terms or had been involved in internal resistance to the Junta following the coup. This was due in part to the practice of each prisoner’s security status having to be reviewed by the CIA in the USA before they were released.

At forty and thirty-nine, the Germán and Gladys Miric were the oldest members of the community of exiles in Swansea, and they already had five children. Germán Miric had been a well-known figure in Chile who had met Fidel Castro and Pablo Neruda. A member of the Communist Party, he had been elected Mayor of Antofagasta, a city in northern Chile. After being imprisoned during the coup and then sent into internal exile, he left Chile in 1977 for London and moved to Swansea in 1978. Miric’s arrival in Swansea changed the dynamic of the local campaign, mainly because he was older, very experienced and highly respected. Although not a leading activist in the town, he was very influential, mediating and moderating between the different political parties and groups among the Chileans. Over time, in Swansea and more broadly in Britain, differences dissipated, reflecting what was also happening in Chile. Yet Miric was strongly ideological. Together with other Communist parents, Miric wanted his teenage children to understand why the family had had to go into exile in Wales. They sent them to the Young Communists to learn about this, and the Miric sisters attended youth congresses. They had little or no choice in this. At the age of fourteen, Gisella was sent with two or three other young people from Britain to a camp for young people in East Germany (DDR), and at the age of thirteen, Geri travelled to Hungary with two friends from London to attend a Communist Party school, where she met many other young Chilean exiles from around Europe.

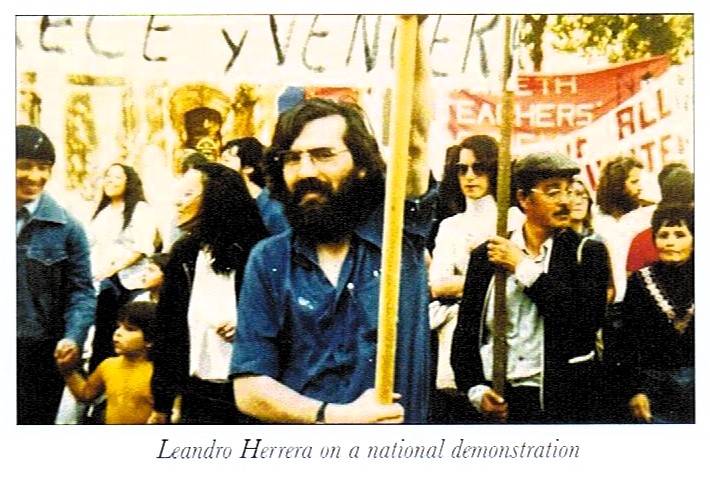

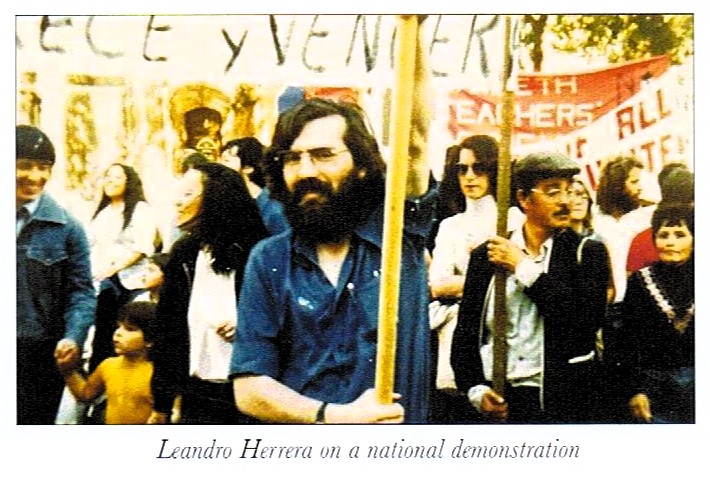

Leandro Herrera arrived in Swansea early in 1976, together with his wife, Victoria Leighton de los Ángeles Mendez, simply known as Toya and their young daughter. Both Leandro and Toya had had their studies cut short by the coup. Toya had been in her first year at university, and Leandro was a postgraduate. Both were scientists, and both were members of the Communist Party. Leandro was quite hard-line in his support of the Soviet Union, as I remember from a conversation with him in 1980 about the situation in Czechoslovakia. They had married in September 1974, at a time when Leandro was involved in poverty alleviation and housing projects in Chile. As a charismatic leader, Leandro was on a list of students accused of illegal activities, and when the security services arrived at their house asking for them by name, their neighbour informed them of the visit, and they were able to evade capture and detention by hiding in friends’ houses. They left for France in 1975 and stayed there for a short period before their friends and fellow Communists already living in Swansea suggested they join them. On arrival in Swansea in 1976, they quickly encountered the group of Chileans who provided a warm welcome. Toya, in particular, immediately felt full of life and hope again. Leandro had good English on arrival and received a WUS grant for a PhD in Biochemical Engineering. Toya completed her degree while also raising her young family before returning to Chile with the children in the early 1980s.

Adaptation, Trauma and Security:

Many of the predominantly middle-class Chileans found it difficult to adapt to a lower standard of living in exile than they had been used to in Chile before the coup. They found themselves living on council housing estates and experiencing some racism and petty discrimination in reaction to their skin colour and accents, despite Swansea’s earlier industrial and trading links. Nevertheless, the combination of WUS grants and their own common purpose, to survive and study, allowed a vibrant group to develop. The income from their grants enabled them to maintain a sufficient level of financial independence, so that most of them had a solid base from which to integrate into their neighbourhoods. Considering their comparatively small number, the Swansea Chilean exiles made a disproportionate impact on their host society, both culturally and politically.

However, when the refugees first began to arrive in Wales, they carried the trauma of their enforced exodus and were initially suspicious of everyone, not knowing who might be agents of the Pinochet Junta. Individuals continued to use the noms de guerre they had acquired in Chile, rather than revealing their real identities and family backgrounds to fellow Chileans. They did not know who their compatriots in exile were, or where they came from. In these circumstances, it was very natural for them to remain hermetically sealed after living through years of clandestinity under the dictatorship. Decades later, there was still a consciousness of the need for security, not just to hide their personal identities, but also to protect their families in Chile from persecution by the régime. Some were only prepared to speak about their Chilean families fifty years later, in their interviews with Alun Burge. But despite their initial varying states of distress at what and who they had left behind, they also brought with them their experiences of working to build a better and more just society. Clive Haswell, who was involved in the Swansea support group, felt that having been part of a passionate crusade for a better future under Allende, and then having lived through a political cyclone at the time of the coup, they found an echo in Wales and were able to build a movement around themselves.

Student Solidarity & Resistance from Exile:

Neil Caldwell, an Aberystwyth graduate who was Chair of NUS Wales (UCMC) from 1975 to 1977, based at its Swansea Office, saw the Chilean exiles as an active, vibrant and colourful community, sufficiently large to have its own critical mass. That community itself decided on what form the solidarity campaign would take and how it would be organised. Their activism had much in common with that of both local and other overseas students, so that they fitted in well. Most were of the same age, from similar backgrounds and educational levels as many of their local supporters, and they shared the same ‘broad left’ political outlook. Paul Elliott, a local trades union official who had been involved with Chile Solidarity in Bangor in 1975, moved to Swansea the following year, the same year that Jane Elliott arrived from London. The couple also married that year and their wedding was attended by some of the Chileans, as was that of Neil Caldwell.

In November 1975, Caldwell participated in a five-day international event attended by about two hundred students, including some who were smuggled out of Chile at very high risk, and spoke incognito. Concerts were held in Cardiff and Swansea by the ‘Victor Jara Group’. When Caldwell left the London Conference, he took a dossier of evidence and a statement on the situation in Chile to the International Conference on Solidarity with Chile in Athens. There, international working groups from different sectors – engineers, medics, architects, as well as students – who had escaped from the country, and were in touch with people still there, assessed the situation since the coup. Their work was subsequently referred to at the UN General Assembly.

Meanwhile, the Swansea Chileans continued to oppose the Pinochet dictatorship from exile in Wales. By 1978, there was a strong concentration of them settled in the city, with a spirited camaraderie that also drew on Chilean traditions of La Pena, ‘the party’, a social event including music, food and conversation. These parties were relatively unstructured cultural occasions which provided informal opportunities to talk politics and communicate information about what was happening in Chile, rather than using platform speakers at public meetings. The opposite of dogmatic discourse, it was an effective way to engage people with political messages. For many supporters among the hosts, used to the more formal methods of discussion and debate in the British labour movement, this was a refreshingly different way of doing politics.

The Chileans were only one of the refugee groups in South Wales. Ali Anwar was from Iraq and met the Chileans in Swansea in the late 1970s. At the time, the refugees from Saddam Hussein’s murderous Ba’athist régime had formed the Iraqi Student Society, opposed to the state-sponsored National Union of Iraqi Students, the members of which operated as Saddam’s thuggish agents on campuses across Wales and Britain, beating up the dissidents. They also shared houses and flats. Photos of Chilean social gatherings included Iraqis, Iranians and Sudanese. In return, the Iraqis welcomed the Chileans to Persian food parties at their homes in Sketty and Uplands. As a result of these associations among the various exiled groups, Ali became an elected member of the NUS Wales Executive in the autumn of 1979, with responsibility for Overseas Students’ Affairs.

I was a regular visitor to the home of Leandro Herrera and Toya Leighton in the Uplands, and they often came to see me in the house I rented from Aled Eurig’s parents, who lived in Aberystwyth during term-time and needed a ‘trustworthy tenant’ to take care of the property while they were away. It was a large Edwardian house with its original wiring and servants’ bells in every room, connected to a panel in the kitchen, although they were no longer in regular use. All the bells had the same tone, including the front door bell, and Leandro delighted in ringing the bell in the downstairs toilet, which made me go to the front door, where, of course, no one was waiting to come in. On turning around, I would meet Leandro emerging into the hallway, laughing, from the toilet! He was also a frequent visitor to my office in Walter Road, mostly to help co-ordinate the solidarity campaign with NUS Wales, but on one occasion, he needed help in recovering his vehicle, a Russian Lada, from near the hospital at Singleton Park. He had just been present at the birth of his son, their second child, and he had been in such a euphoric state that he had an accident on his way home. His car was never properly repaired, and he once had to drive at night to a meeting in Aberystwyth. As the front offside headlamp illuminated the hillside rather than the twisting Black Mountain road ahead, the front passenger had to sit holding a torch pointing in the right direction, enabling the company to make the return journey ‘safely’. After that, Leandro’s antics and slapstick sense of humour became legendary and endeared him to his friends, both British and Latin American, and provided some much-needed relief from campaigning and trauma!

From Santiago to Swansea – Hunger Strikes, 1978-79:

In 1978, momentum had built in response to a hunger strike in Santiago involving twenty to thirty relatives of the disappeared at the Central Hall of the United Nations building there, which was quickly surrounded by armed police. Five young Chilean exiles, together with Dr Sheila Cassidy, began a solidarity strike at St Aloysius Church in Euston, London. The hunger strikers called for the UN Ad Hoc Working Group on Chile to visit the country to carry out an exhaustive investigation into the disappeared. Hunger strikes were regularly deployed to draw attention to human rights abuses in Chile. In May 1978, seven Chilean refugees in Swansea undertook a seven-day hunger strike at The Friend’s Meeting House, with the support of the Quakers, to protest at the plight of the 2,500 missing prisoners in Chile. As part of an international campaign, the action was one of those undertaken in eighteen countries across Western Europe, Latin America, North America and Australia. These were undertaken in support of the 150 relatives of the disappeared who were on hunger strike in Chile. By the time the Swansea action ended, the hunger strikers had succeeded in drawing local attention to the cause. Six other Chileans then began a follow-up strike at the Catholic Chaplaincy in Cardiff, part of a wave of nineteen actions across Britain.

As momentum built, the hunger strikes brought together Welsh supporters of the Chilean refugees across Wales in a common cause for the first time. Campaign advertisements in the Western Mail and South Wales Echo involved an impressive array of individuals and organisations from different sectors of Welsh society. Among the churches and their leaders were the Annibynwyr (Congregationalists), Baptists, Catholic Justice and Peace groups, the Bishop and Dean of Llandaf. Academics, actors, artists and performers were also listed, including Dafydd Iwan, whose Welsh language song Cán Victor Jara was released in 1979, about the Chilean folk-singer who was tortured and murdered in the Chile Stadium in the days after the coup ‘in Santiago in ’73’. Other signatories included local authority leaders, Labour and Plaid Cymru MPs, Cymdeithas yr Iaith (the Welsh Language Society), together with other international solidarity campaigns, trades unions (including the NUM) and councils, the Wales TUC, and local human rights campaigners. The hunger strikes were suspended when David Owen, then Foreign Secretary, told the campaigners that the régime was allowing the UNHRC to visit Chile and the Junta promised the Chilean Church leaders an investigation into the Missing, provided their relatives and supporters called off their action. Copies of pamphlets in Welsh were distributed at the National Eisteddfod in Cardiff.

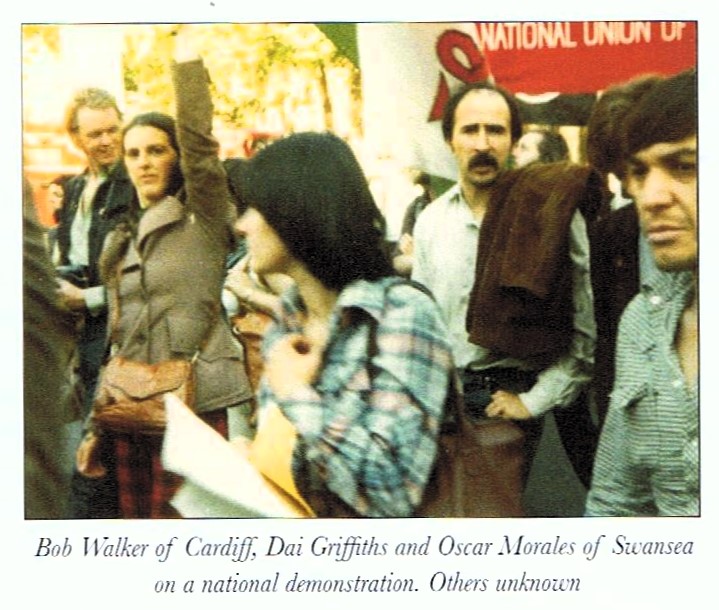

The pressure brought on the Pinochet régime by the worldwide hunger strikes meant that they were seen as an effective tool. In the late summer of 1979, when I took up the role as the full-time officer of NUS Wales (UCMC), based in Swansea, another hunger strike was organised in the city, together with the Chile Solidarity Campaign. This was held in support of one taking place in the Danish Embassy in Santiago, demanding the return of bodies found in the abandoned Lonquen mine. Although outside of term-time, fifty overseas students marched from the University College campus to the Henrietta Street Congregationalist Chapel, where they undertook the strike in forty-eight-hour shifts. Half of the strikers were Chilean, and the rest were ‘local’ supporters, including Iraqi and other overseas and British students, including myself.

The venue was the idea of Aled Eurig and his father, Rev. Dewi Eurig Davies, who was a minister in the church and a professor at its training college. He contacted the chapel, whose minister met with us, and the deaconate agreed to host the hunger strike free of charge. Trilingual coverage was heard on the local radio station, Swansea Sound, when Leandro Herrera was interviewed in Spanish, with translation directly into Welsh, and I was interviewed in Welsh. After five days, the hunger strike was called off when Chile’s High Court ruled that bodies found in the abandoned mine should be returned to their families. However, the Junta ignored their ruling, so the hunger strike strategy seemed to have run its course and had come to a somewhat abrupt ending. Leandro and others among the hunger strikers travelled to London the following weekend to take part in a national demonstration.

Cán Victor Jara – The Song of the Exiles:

Some months later, UCMC sponsored a concert in Swansea given by Dafydd Iwan, who performed Cán Victor Jara three times, including once in English, a rare ‘compromise’, for a mainly international audience. Dafydd Elis Thomas, then Plaid Cymru MP for Meirionydd, also attended with me, after speaking at an Anti-Apartheid rally in Llanelli. This was a recognition of the importance of maintaining the rhythm of solidarity work alongside a broader commitment to other international campaigns, such as the protests against the South African Barbarians’ Rugby team’s tour of Wales. When Brian Davies moved from Swansea to Cardiff in the Spring of 1979, he encountered very little activity on Chile. Alun Burge thinks this was due to disillusionment after the wave of hunger strikes had died down, but, on reflection, it was more likely to have been due to the comparative size of the Swansea exiles in relation to the neighbourhoods where they settled. Bringing with him his experiences from the Swansea CSC, Davies helped to organise a series of events at the Sherman Theatre featuring a Latin American folk group, a Welsh folk group, a male voice choir and guest speakers. This mixture of regular cultural events with political education maintained the momentum of the Chile campaign. By 1979, the Chileans were still refugees, but they were organised in resistance and no longer saw themselves as desperate victims.

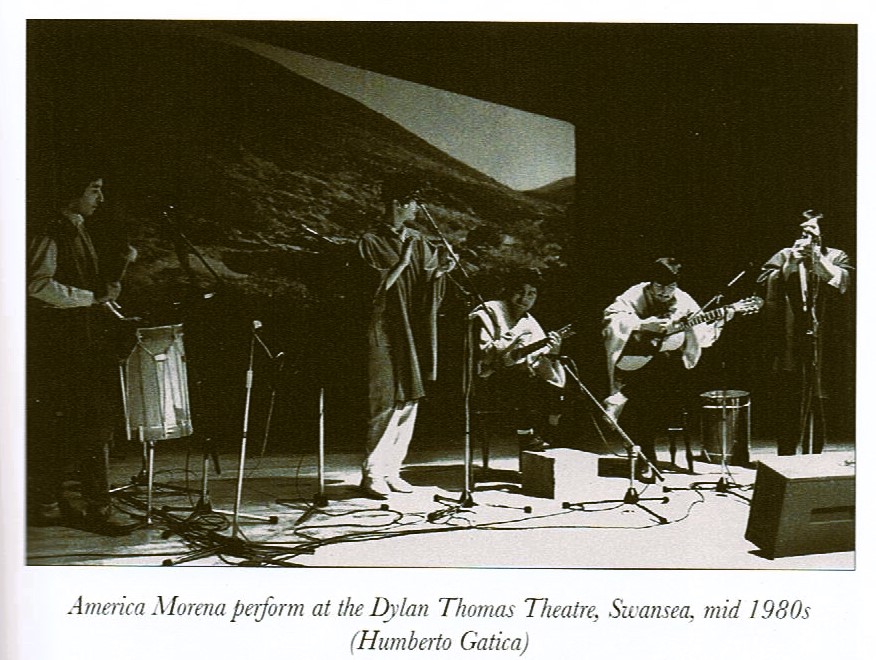

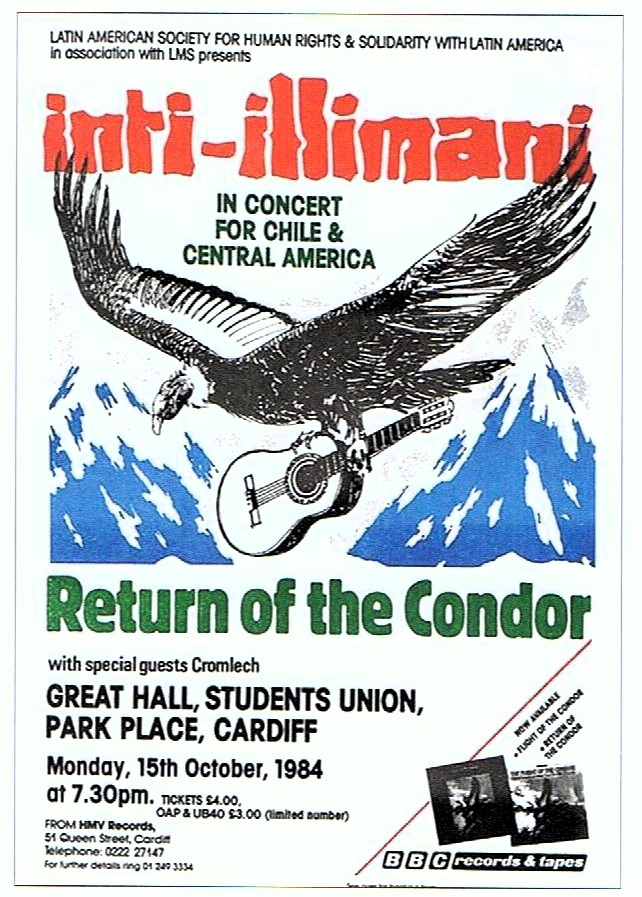

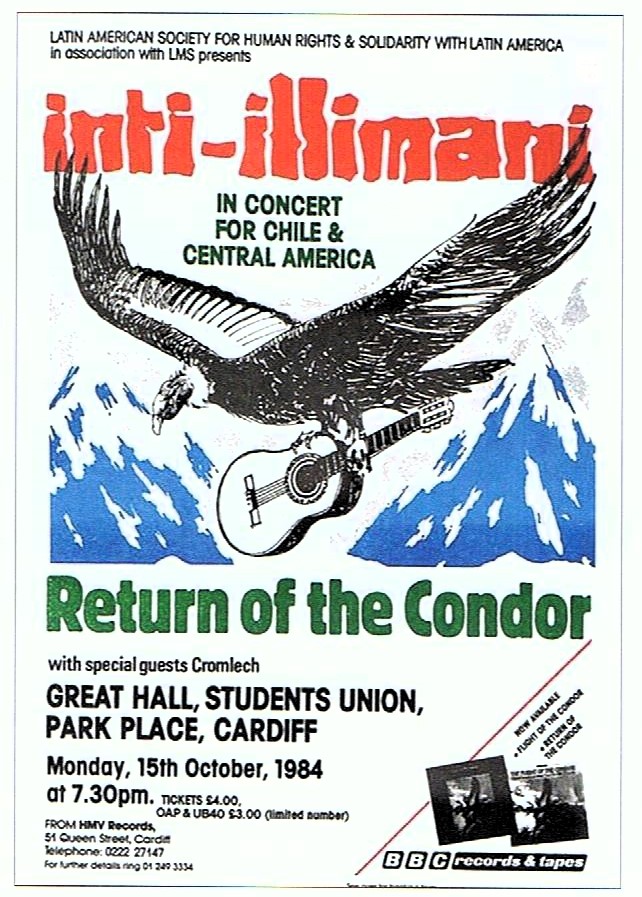

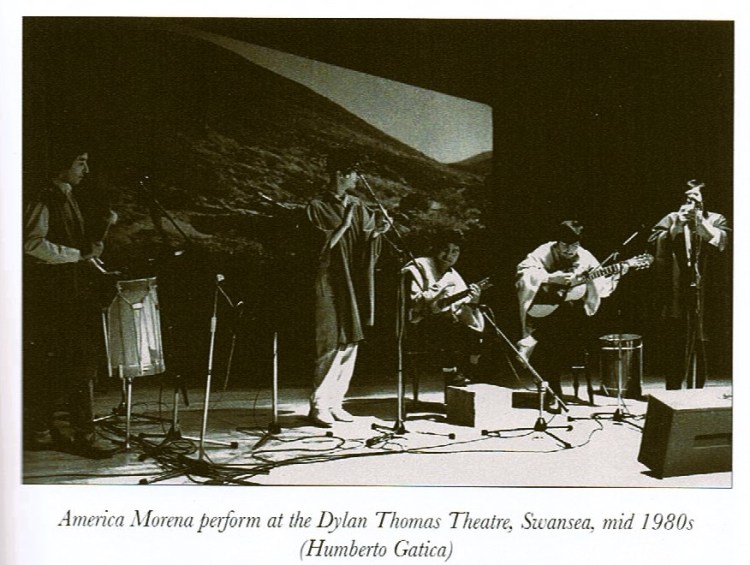

Music was an important part of this achievement. The group founded in Swansea used their performances to explain life both before and during the dictatorship as well as to raise funds for the CSC and for political prisoners in Chile. Their music drew on indigenous Andean culture and musical instruments, in itself a form of resistance since, after the coup, the folk music movement was crushed and banned in Chile, along with its instruments. Reflecting first the hopes of Allende’s Popular Unity government and, from 1973, the resistance against the Pinochet régime, the Swansea music group helped to galvanise solidarity in Wales by playing the music of Victor Jara and other Chilean groups. The Chilean new song movement was part of a process of social and cultural change, and the nueva canción represented a musical revolution which gained political power. Connected to Popular Unity, committed to the poor and excluded, it demanded their rights and challenged the status quo, prevailing economic and political institutions and the ‘Western’ domination of music. In September 1976, a ‘Chile Week’ was held in Swansea to mark the third anniversary of the coup. In April 1978, the Chilean group performed for 350 people attending the Llafur (Welsh labour history) Conference in Swansea. In these informal ways and settings, the Chilean refugees soon became part of the cultural fabric of South Wales in general and of the regional labour movement in particular. In their exchanges with local people, they gave as much as they received, and were still playing in the valleys communities in the mid-1980s.

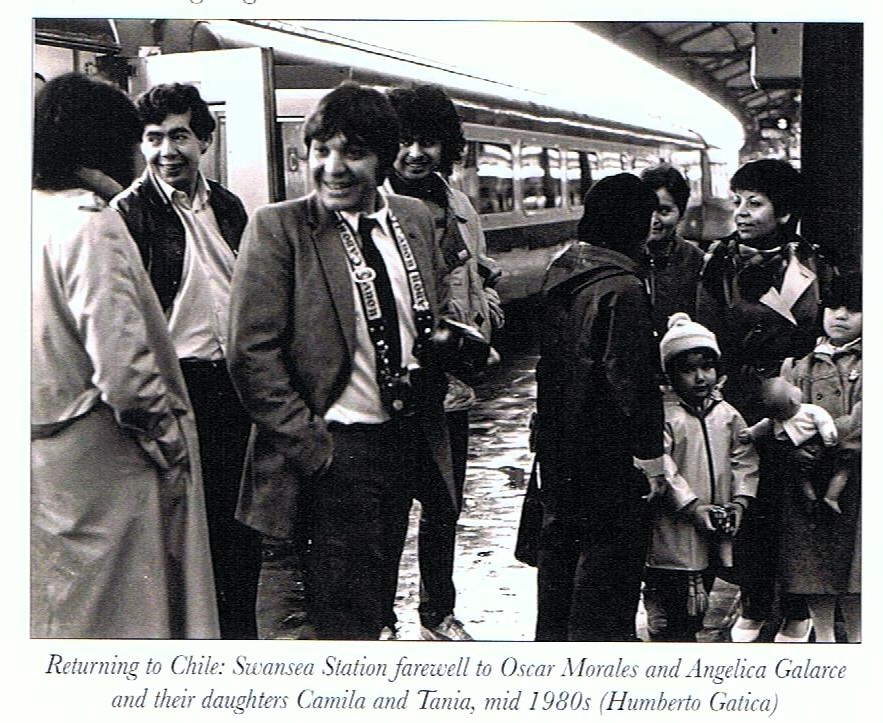

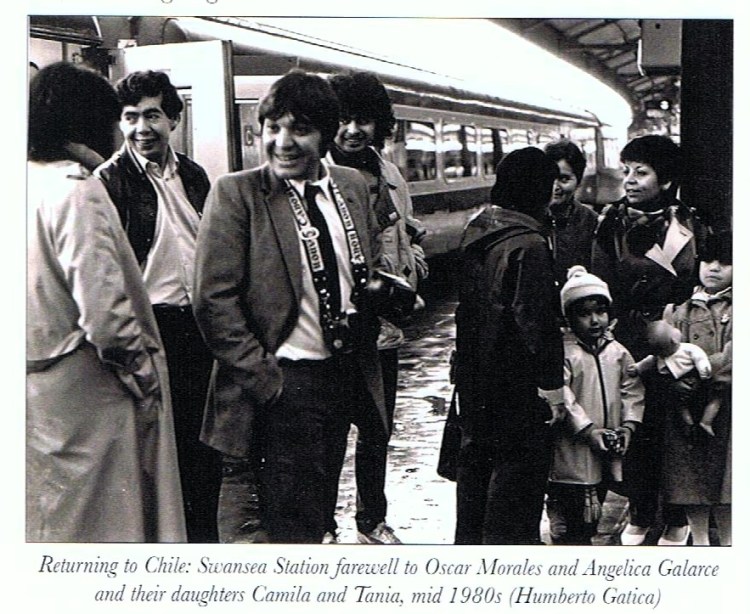

Seeking the Right of Return:

As early as the summer of 1979, calls were made for Chileans to have the right of return to their country. They had always intended this. However, the situation in Chile remained too difficult, as evidenced by the disappearance of some returnees. WUS established an office in Santiago by 1981, overseeing a programme, sponsored by the British government, to aid the return of the WUS-supported exiles. By mid-1981, significant numbers of Swansea Chileans were reported as returning, including Toya Leighton. Burge reports that by 1986, twenty had returned, with fifty remaining, of whom half were children. He estimates that by then, approximately two-thirds of Chileans had left the city. However, most of those who had been sentenced by military tribunals, although formally amnestied in 1978, were refused authorisation to return when they applied to the Chilean Embassy in London. Burge summarises the attitude of the Welsh Chileans in the mid-1980s:

Many Chileans regarded exile as temporary. They had no sense that their future was in Wales and their bags were metaphorically packed, ready to return. Some did not expect to be in exile for a prolonged period and had not prioritised learning the English language. … unwilling to accept their circumstances, after a decade, where only a return to Chile would provide a solution. For those in the political élite, whose ideals were ‘almost the sole reason for existence’, they continued living the tragedy which, in turn, limited their adaptation to Britain and led to anxiety, depression, or even suicide. For those caught between going or staying, life was constantly having to be renegotiated because, although never feeling settled, they were obliged to adjust.

(Burge, pp. 69-70)

Many of the Swansea Chilean community had children of the same age, and their families did a lot together and with host families, including beach parties. With a new generation born in Wales, or with children who were so young when they left Chile that they had little or no memory of it, Swansea’s Chilean parents ran Saturday schools to teach Chilean history, geography, language and culture to their children throughout the first half of the 1980s. Individuals’ experiences of exile varied greatly, not least between men and women. Some women discovered a new dimension to themselves in exile, living in a less patriarchal society that exposed them to feminist attitudes that challenged previous assumptions. Lila Haines had been in Swansea since October 1974, and her daughter, Miren, was born to her and Meic Haines as the first Chileans arrived. Lila got to know the Chilean women well, especially the Miric family, who were always hosting parties. Meic and Lila spoke Spanish, and Paul and Jane Elliot were their neighbours. The Miric grandmother, Dona Elba Vega, looked after Lila’s other daughter, Rhiannon, when Lila returned to her studies, and also took care of the Elliotts’ young children until she returned to Chile. The Swansea Chilean children retained their sense of extended family and have maintained a strong bond even after returning to Chile. Lila also remains in contact with Toya Leighton in Chile.

Although the situation in Chile remained difficult in the eighties, the process of return started in 1981. It could be highly dangerous, however, and friends of the Swansea exiles were known to have disappeared after returning. Nevertheless, a significant number of Swansea Chileans had returned by the mid-1980s. In 1986, twenty returned from Swansea, with fifty-three remaining, including twenty-four children. These figures suggest that, by then, two-thirds of Chileans had left the town.

In the early 1980s, America Morena was formed, the culmination of the evolution of the Chilean music groups of the 1970s in Swansea and Cardiff. Comprising younger musicians from both cities, they sometimes played with the Welsh rock singer, Geraint Jarman, and so entered the world of the Welsh cultural scene, with some of them appearing in the 1983 Welsh-language film Gaucho. By then, I had left Wales after eight years as a student and was an ‘exile’ in Lancashire, before returning to my parents’ home in Coventry in 1986. Nevertheless, through Llafur (the Welsh Labour History Society), I maintained irregular contact with former colleagues from home and abroad. After finishing my PhD thesis on Welsh exiles in the English Midlands and graduating from the University of Wales, I then moved to central Europe shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, and the collapse of communism in Hungary and Poland. Meanwhile, a plebiscite in Chile voted to end the rule of the Junta in October 1988, and after democratic elections in December 1989, a Christian Democrat government took power in March 1990.

A Chile Without Pinochet:

In December 1980, at the age of forty-three, Germán Miric went to teach in Nicaragua. He went alone as his children were attending Swansea schools, some at secondary level. Although he had originally hoped that they would join him as a step in remigration to Chile, within eighteen months, he returned to Wales. Geri, his daughter, didn’t finish school until 1986, and even then did not want to leave. Germán eventually returned to Chile in 1991, followed by Gladys and Giordan a few years later. Geri split her time between Britain and Chile while Gisella, who remembered little of her early childhood in Chile, settled in Britain. In 1994-95, when Geri Miric finished her university studies, she decided to return to Chile. She immersed herself in Chilean life, speaking Spanish fluently, though people often asked her if she was Chilean, as she spoke very differently. From 1996, she worked for an international corporation, speaking English with Americans, Canadians, Australians and British business people. She was treated with great respect by her Chilean colleagues because, although of equal status with them, she had been educated to a much higher level in Britain, and was linguistically the equal of the company’s directors, with whom she could discuss anything. She commented that it was a different Chile from the one she had left to go into exile:

… “a Chile without Pinochet, a Chile of hope, yet a very, very, very divided Chile because, although things had changed, the division was even more prominent than before.” (Burge, p. 80).

In October 1998, Pinochet was arrested in London for his crimes during the dictatorship. When Geri arrived at work that morning, the office where she worked was in uproar, and the whole staff was called into the meeting room to view the unfolding event on the big screen. Most of her Chilean colleagues were Pinochetistas, but Geri was not expected to attend, as there was ‘a silent understanding’ that she was ‘one of the exiadas… and no supporter of Pinochet.’ The Managing Director of the Company decided to hold a collection among the staff towards the campaign to bring Pinochet back to Chile, but as the bucket was passed around, it did not come to her. Other members of staff had been told that if they did not contribute, they would be fired, but no one came to her to ask. By the time Pinochet was released from house arrest and allowed to return to Chile, Geri had returned to Britain. Then, in 2004, the Chilean government announced that the 28,000 survivors of torture under the Pinochet régime, including some still living in Swansea, would receive life pensions as compensation. In the same year, the Chilean Supreme Court ruled that the dictator did not have immunity for the crimes carried out under Operation Condor, the official name of the coup. The indictments against him continued to increase until he died in 2006.

The Legacy of the Chile Solidarity in Britain:

Another reason why the decade of Welsh solidarity with Chile has had little permanent effect may lie, in part, in the organisational weakness of the British Labour Party and movement at that time in Wales. The solidarity movement in Wales reflected what was organisationally possible at that time. Only once, around the 1978-9 hunger strikes, did cross-Wales co-ordination take place through the collaboration of the solidarity groups in Cardiff and Swansea. Although primarily a movement across South Wales, major sections of the population – trade unions, church and cultural organisations – came together in a single cohesive expression of support for the call for accountability over the disappearances.

The development of a strong, independent voice for Welsh students in UCMC (NUS Wales), established in May 1974, was hampered by the defeat in the devolution debácle of 1st March 1979, and the rise in support for Young Conservatives after the Thatcher landslide in three out of the six university colleges. Support for refugees continued with the granting of a bursary to a Bolivian copper miner for studies organised through the NUM. However, his lack of English and course preparation led to his return home after a few months. UCMC was preoccupied with fighting the cuts in education in Wales, first introduced by the Callaghan government and carried out by Labour-controlled local education authorities, and the imposition of full-cost fees for overseas students by the Thatcher government. These issues affected refugee students as much as they did international students in general. A meeting with the University’s Chancellor, HRH Prince Charles, at which we presented him with a document prepared by UKCOSA (The UK Council for Overseas Student Affairs), led to an exchange of letters with both the Foreign Office and the Home Office. His main concerns were the impact of the policy on Commonwealth countries and the potential of its detrimental effect on scientific and technical courses within the University.

The labour movement failed to advance international causes, such as anti-apartheid, largely due to the continued weakness of the Wales TUC, which had only been inaugurated in April 1974. Moreover, its terms of reference had explicitly excluded its campaigning on such matters. International solidarity was no longer the ‘order of the day’ or even a secondary priority. When the journalist Donald Woods came to Swansea following his ‘escape’ from South Africa in 1980, it was the NUS which organised, together with Swansea Students’ Union, his meeting at which his Penguin book on Steve Bíkó was launched. Certainly, the Wales TUC was in no state to take on the Welsh Rugby Union over its hosting of the South African Barbarians in 1979, even if it had wanted to, and even though the campaign was consciously given the name South Wales Campaign Against Racism in Sport. It arranged for Peter Hain to come to Cardiff, where he met with local groups and the Wales TUC, an association which led to him becoming MP for Neath and a leading member of the Blair-Brown governments. For many, the perspective of the South Wales industrial valleys and their institutional legacy, of Nye Bevan and Jim Griffiths, was the determining factor in their political consciousness and remained so until the 1997 General Election, when ‘New Labour’ took charge at Westminster, and a Welsh Assembly was established the following year.

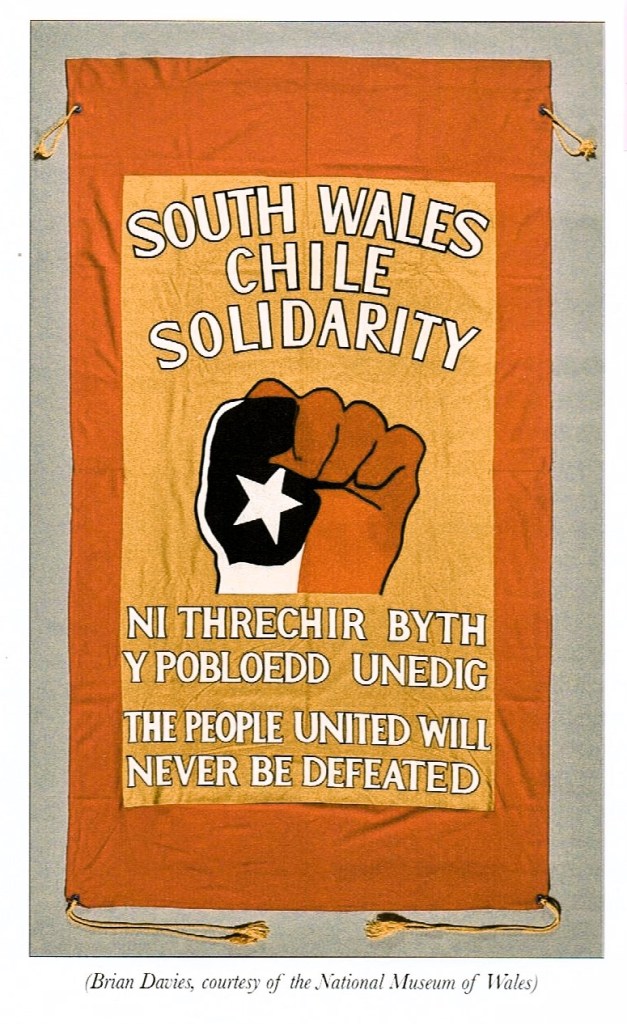

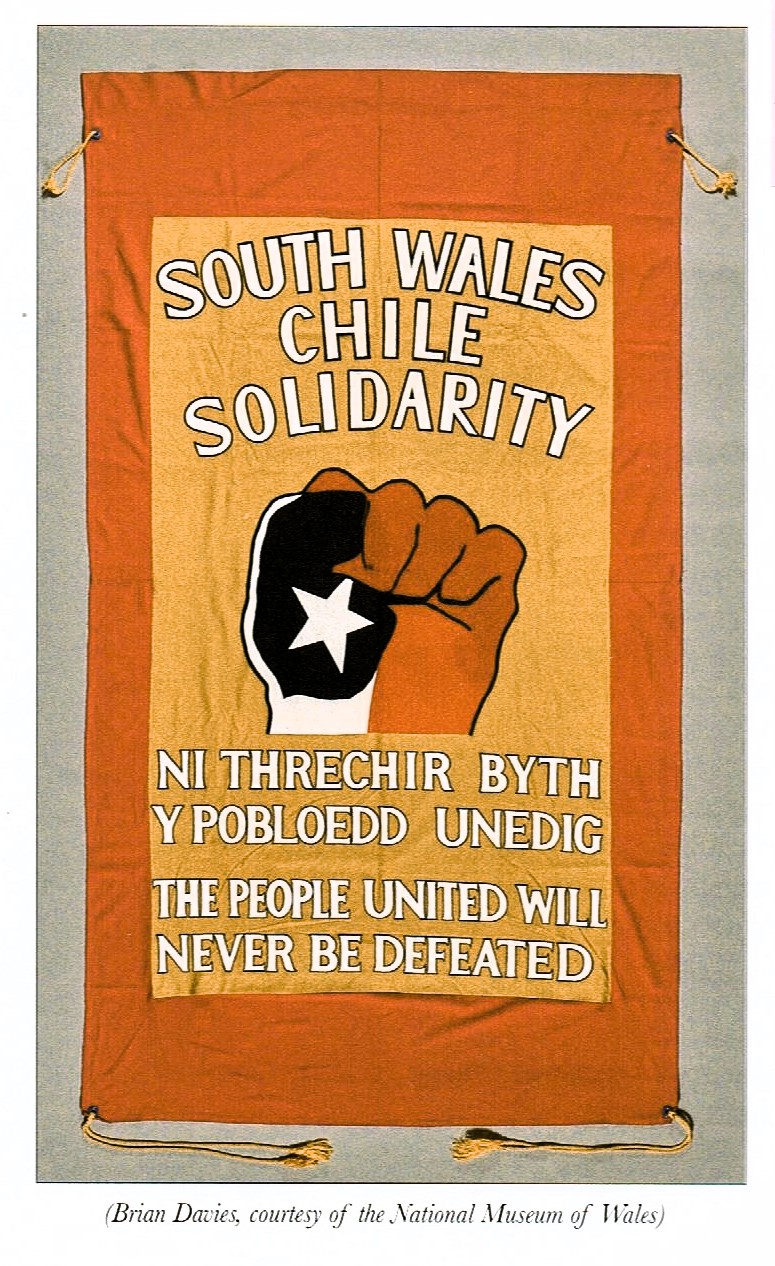

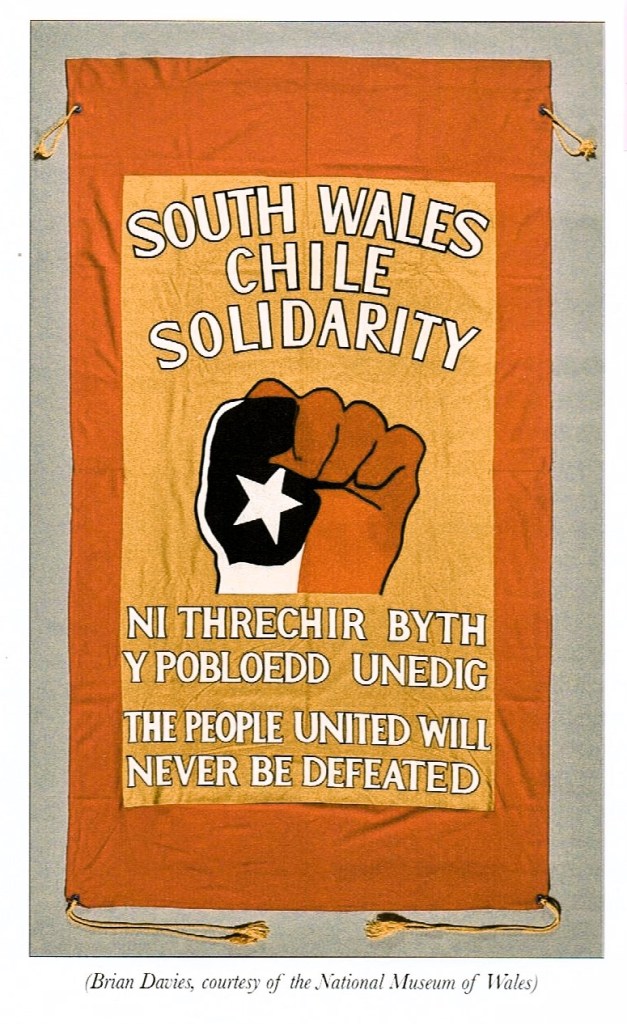

‘Old Labour’ had been wedded to taking power at Westminster and using it from the top down and from the centre to the ‘peripheries’. It was therefore a British state ‘socialist’ party, centred on London, without, as yet, an all-Wales organisational level. The Chile Solidarity Campaign and the Wales Anti-Apartheid Movement (WAAM) were indefinitely and uneasily located within the Nationalist-Labourist debate. Brian Davies, a founding member of the Niclas Society, identified the limitations of the industrial unionist tradition within the labour movement in South Wales, which he argued should define Wales as a country, not a coalfield. He saw the crux of the issue as being an internationalism that denied or dismissed its own national identity. Ironically, however, when he had designed the Chile Solidarity banner, translated into Welsh by Cymru Goch founder Meic Haines, it bore the name South Wales Chile Solidarity. Of course, at that time, this simply reflected a geographical and economic reality. Davies recognised that, apart from the NUM, the trade unions in Wales were primarily economistic. However, eleven years of ‘Thatcherism’ and the 1984/5 miners’ strike transformed the context within which international solidarity operated. The Labour movement in Wales was effectively broken and remained weak for the next decade. Support for Chile was not unified at a Wales, or even a South Wales, level, but rather took different forms in different times, and with different motivations.

In 1982/3, Margaret Thatcher made an alliance with Pinochet and prevented his extradition to France, one of the many countries that had indicted him for crimes against humanity. Those tortured by the tyrant had included the British nurse, Sheila Cassidy, and many US citizens working in Chile at the time of the coup. The role of the CIA in supporting the coup has been well documented and portrayed in the film, ‘Missing’ starring Jack Lemmon, based on the true story of a US Republican’s search for his son.

Recent Refugees & Reflections:

In 2022, people across Wales opened their homes to Ukrainian refugees, offering them accommodation after the full-scale Russian invasion in February of that year. Around 7,500 came to Wales, including over three thousand who arrived under the Welsh government scheme and over four thousand sponsored by Welsh families or relatives. In recent decades, by contrast, support for causes other than Syria and Palestine has been muted. The ‘hole in the iron curtain’ and the ‘fall of the wall’ in 1989 led to shifts in popular historical consciousness and the demise of the Communist Party of Great Britain and other extra-parliamentary socialist activism. This demise caused a vacuum in working-class education and publications in Wales, which had played a significant role since the interwar period. Within Wales, the return of the great majority of Chileans to their homeland meant that their cultural and ideological influence on their countries of exile receded. However, the impact on them of their extended sojourn in Wales remained strong, confirmed in 2019 when many who had returned from Swansea and London gathered at the home of Germán Miric in Larmahue, in central Chile, to celebrate his 82nd birthday and to recall their shared experiences of their adopted land.

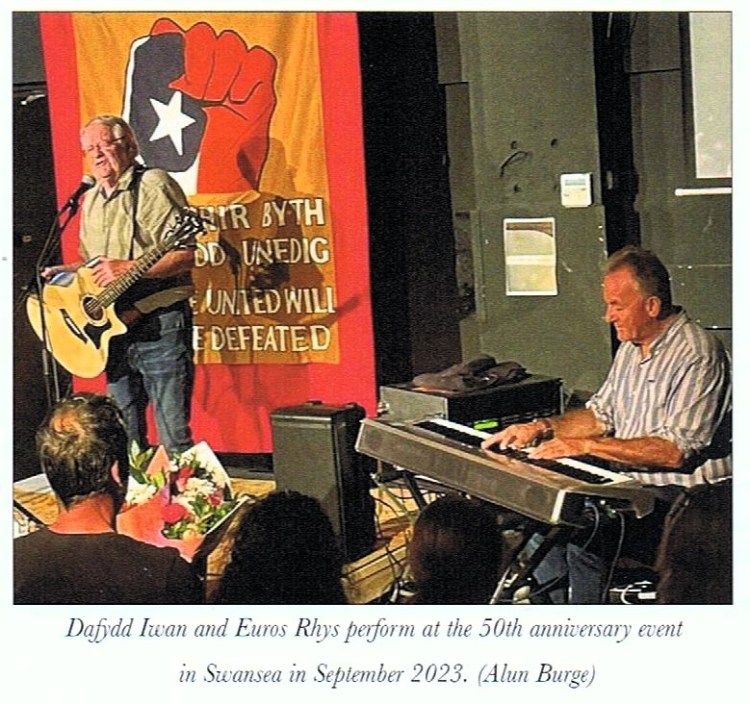

In 2023, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the coup, a sell-out event at the Volcano Theatre in Swansea provided a remarkable blend of politics and culture once again. Organised by José Cifuentes, it revived the pena tradition of music, poetry, food and political conversation. Dafydd Iwan once more sang Cán Victor Jara, and Jane Hutt, Minister for Social Justice in the Welsh Government, gave a speech on refugees and asylum seekers that illustrated the then sharp divide on the subject between the devolved governments of Wales and Scotland and the UK government at Westminster. Rocio Cifuentes, who had arrived in Swansea at the age of one, was now the Children’s Commissioner for Wales, and reflected on her experiences as a Swansea Chilean. All the Chileans still in Swansea, by then only a handful of the original hundred and fifty, attended. The South Wales Chile Solidarity Campaign banner hung over the stage, together with a small Chilean flag which had been brought into exile by Germán Miric. Both can now be seen on display at the National Museum of Wales.

The solidarity campaigns in Wales from the 1970s to the 1990s, especially the CSC and WAAM, the latter organised by Hanif Bhamjee (who died in 2024). These movements brought together people from a range of backgrounds and political cultures in models of all-Wales working that would later become common, not least in the 1997 devolution campaign and made them important harbingers of a broader, more cohesive Welsh society in the way Wales now sees itself. The recent by-election in Caerfilli has shown how, in supporting Ukrainian refugees, it has become a dedicated Nation of Sanctuary within the UK, as informal cross-party working saw off the challenge of an anti-asylum candidate. During the time of Pinochet’s house arrest, some of the remaining Swansea Chileans combined with refugees from other countries and local supporters to set up a support group for the new wave of asylum seekers who had arrived in Britain and were being dispersed by the Home Office to towns and cities around the country. Twenty-five years later, Swansea Asylum Seeker Support continues to function and meet new challenges. Alun Burge concludes:

In the evolution of a national consciousness, … Wales continues to reimagine itself and its relationship with the rest of the world; its historic role in providing international solidarity is one means by which Wales should frame itself.

Burge, p. 101

A Personal Appendix – ‘When the Sun Shines Again’:

A Poem by a Visiting Chilean Student Leader, Alma Sol; January 1980.

When the sun shines

Again in my land

I will remember your winter

Your fight, due to the words,

is strange and beyond me,

today, in them, I do not understand it

but through your eyes and your wheat hair

I listen to your song which is mine also,

in the song of my country

which slowly in its silence

lives as well in your hands

Continue, unknown brother

Continue in your footsteps that I am

able to foresee

Continue in your fight, which is

the same as ours.

Alma Sol, Swansea, 13 January 1980.

Sources:

Alun Burge (2025), The Tenderness of a People: Welsh Solidarity with Chile and the Evolution of International Consciousness. Swansea: Hafan Books (The book’s title is based on the Spanish phrase, Solidarity is the tenderness of peoples: ‘Undod yw tynerwch rhwng pobl’ in Welsh.)

Related articles

- Springsteen honors Chilean folk-hero tortured and murdered by Pinochet (rawstory.com)

- A Chile to remember: exclusive video report on 1973 coup (voiceofrussia.com)

- 40 Years After US-Backed Coup, Chileans Search For Justice (mintpressnews.com)

- Agony of Chile’s dark days continues as murdered poet’s wife fights for justice (theguardian.com)

- Former AP editor recalls covering 1973 Chile coup (sfgate.com)

- PHOTOS: Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup in Chile, 40th anniversary (photos.mercurynews.com)

- Chile marks 40th anniversary of Pinochet’s coup (sfgate.com)

- Springsteen gives tribute to Jara in Chile (voiceofrussia.com)

- Clashes in Chile as 1973 coup marked (bbc.co.uk)

Gallery: