Preface: Prejudiced Politics & Peace Education:

Recent political events in the United Kingdom have included those surrounding the Conservative ‘shadow’ justice minister, Robert Jenrick, who has been ‘on manoeuvres’ since losing the party’s leadership contest a year ago. As part of his campaign, he has taken to ‘social media’ with a series of issue-based amateur video campaigns. In March of this year, he paid a fleeting, ninety-minute visit to the streets of Handsworth in Birmingham to film a ‘home movie’ on the issue of ‘litter’. His conclusion was that the area was a ‘slum’, which was controversial enough, but his succeeding speech to a local Conservative Association in the West Midlands, an area which received the ‘white flight’ emigrants from the ‘inner cities’ in the 1970s and 1980s, has only recently come to public attention. In this, he told the Tory faithful of his unease at not seeing ‘another white face’ and said that he would ‘not want to live’ in an area where this was the case. This negative labelling and stereotyping of mixed cultural areas in Britain by public figures and others is something I have had to confront periodically over the past fifty years, a form of racism that has plagued modern times both in my own country and others where I have made my home. My original home of Birmingham was also the place where I began my work as an advisory teacher in the field, when I took up an invitation to develop an intercultural project, jointly sponsored by West Midland Quakers and the Christian Education Movement, which also linked that project with a community-level one among inter-faith teachers in Northern Ireland, funded by the UK government’s Education for Mutual Education programme.

Beyond Multiculturalism – Intercultural Relations in Birmingham in the 1980s:

We had already hosted the Northern Irish teachers in Birmingham, where the Inter-cultural Conflict and Reconciliation Project was launched under the auspices of the CEM in 1986-7. They had visited Handsworth and met a black community worker as well as a community policeman. Walking with them along the long main road through the district, I recognised their obvious unease as being similar to the way I had felt driving a minibus full of students through the middle of Belfast and around the ‘peace line’ two years earlier. I remember asking the teachers about integrated education as a solution to overcoming the sectarian divide in education. The reply came that removing churches from secondary schools did not help bridge the divide, since before young people could reach out across that divide, they had first to feel confident in their own faith traditions. In Handsworth, they visited a Church of England primary school where three-quarters of the children were from Punjabi Sikh families. The parents told us that they had chosen to send their children to that oversubscribed school due to its religious foundation, and because they knew that their children would receive religious education and grow up understanding Christian values.

This provided me with a valuable insight which, in 1990-91, I was able to apply to my work in Hungary, where the role of religion in schools had been suppressed for so long and where RE was still outlawed from the curriculum. By 1991, I returned to Birmingham after setting up an exchange programme in East/West relations. I help train RE teachers in Birmingham, leading workshops for them to try out some of the cooperative activities we had previously developed in West Midlands schools. By that time, our case study of Handsworth, based on the press coverage of the 1981 and 1985 ‘riots’, was already out of date, so it was replaced with a case study on the stereotyping of the Muslim community in Derby. Religious traditions, be they Catholic, Presbyterian, Quaker, Baptist, Pentecostal, Sikh, or Muslim, are there for us to reach out from, in faith, not for us to retreat into, in fear. It is worth remembering a comment from a poet from Derry: the most divisive borders are those we draw within ourselves.

Windrush Pioneers & Population ‘Inflow’:

In Britain, postwar reconstruction, declining birth rates and labour shortages resulted in the introduction of government schemes to encourage Commonwealth workers, especially from the West Indies, to seek employment in Britain. Jamaicans and Trinidadians were recruited directly by agents to fill vacancies in the British transport network and the newly created National Health Service. Private companies also recruited labour in India and Pakistan for factories and foundries in Britain. As more and more Caribbean and South Asian people settled in Britain, patterns of chain migration developed, in which pioneer migrants aided friends and relatives to settle. Despite the influx of immigrants after the war, however, internal migration within the British Isles continued to outpace overseas immigration.

During the 1950s, the number of West Indians entering Britain reached annual rates of thirty thousand. Immigration from the Indian subcontinent began to escalate from the 1960s onwards. The census of 1951 recorded seventy-four thousand New Commonwealth immigrants; ten years later the figure had increased to 336,000, climbing to 2.2 million in 1981. Immigration from the New Commonwealth was driven by a combination of push and pull factors. Partition of the Indian subcontinent and the construction of the Mangla Dam in Pakistan had displaced large numbers of people, many of whom had close links with Britain through the colonial connection.

Although the 1962 Commonwealth and Immigration Act was intended to reduce the inflow of Caribbeans and Asians into Britain, in the short term, it had the opposite effect: fearful of losing the right of free entry, immigrants came to Britain in greater numbers. In the eighteen months before the restrictions were introduced in 1963, the volume of newcomers, 183,000, equalled the total for the previous five years. Harold Wilson was always a sincere anti-racist, but he did not try to repeal the 1962 Act with its controversial quota system. One of the new migrations that arrived to beat the 1963 quota system just before Wilson came to power came from a rural area of Pakistan threatened with flooding by the huge dam project. The poor farming villages from the Muslim north, particularly around Kashmir, were not an entrepreneurial environment. They began sending their men to earn money in the labour-starved textile mills of Bradford and the surrounding towns in Yorkshire.

Unlike the West Indians, the Pakistanis and Indians were more likely to send for their families soon after arrival in Britain. Soon there would be large, distinct Muslim communities clustered in areas of Bradford, Leicester and other manufacturing towns. Unlike the Caribbean communities, which were largely Christian, these new streams of migration were bringing people who were religiously separated from the white ‘Christians’ around them and cut off from the main forms of working-class entertainment, many of which involved the consumption of alcohol, from which they abstained. Muslim women were expected to remain in the domestic environment, and ancient traditions of arranged marriages carried over from the subcontinent meant that there was almost no intermarriage with the native population. To many of the ‘natives’, the ‘Pakis’ were less threatening than young Caribbean men, but they were also more alien.

In 1964, Harold Wilson felt strongly enough about the racist behaviour of the Tory campaign at Smethwick, to the west of Birmingham, to publicly denounce its victor, Peter Griffiths, as a ‘parliamentary leper’. Smethwick had attracted a significant number of immigrants from Commonwealth countries, the largest ethnic group being Sikhs from the Punjab in India, and there were also many Windrush Caribbeans settled in the area. There was also a background of factory closures and a growing waiting list for local council housing. Griffiths ran a campaign critical of both the opposition and the government’s immigration policies. The Conservatives were widely reported as using the slogan “if you want a nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour” but the neo-Nazi British Movement claimed that its members had produced the initial slogan as well as spread the poster and sticker campaign. However, Griffiths did not condemn the phrase and was quoted as saying, “I should think that is a manifestation of popular feeling. I would not condemn anyone who said that.” The 1964 general election had involved a nationwide swing from the Conservatives to the Labour Party, which had resulted in the party gaining a narrow five seat majority. However, in Smethwick, as Conservative candidate, Peter Griffiths gained the seat and unseated the sitting Labour MP, Patrick Gordon Walker, an Oxford graduate who had served as Shadow Foreign Secretary for the eighteen months prior to the election. In these circumstances, the Smethwick campaign, already attracting national media coverage, and the result itself, stood out as clearly the result of racism.

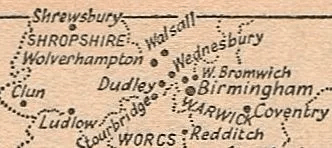

– Before the West Midlands Order 1965 reorganisation

Strictly speaking, Birmingham has never part of the Black Country, which lies just over the south-eastern boundary of the region at West Bromwich, Smethwick and Bearwood, where the old counties of Warwickshire and Worcestershire met. The boundary was literally at the end of the long back garden of our ‘manse’ in Edgbaston, the Baptist Church being in Bearwood. Yet in an economic rather than a geographical sense, Birmingham is at one end of the Black Country, with Wolverhampton is at the other.

Birmingham was never as wholly bleak as the area to the north, though. Its southern suburbs became a dormitory for the middle and upper classes, almost devoid of factories, except for the Austin motor works at Longbridge and the Cadbury factory at Bournville which, like his predecessor J B Priestley, Geoffrey Moorhouse writes about at some length in his chapter on the Black Country. I don’t intend to focus on it in this article. These suburbs were spacious and tree-lined, running eventually out into the ‘Shakespeare country’ of the former Forest of Arden, along the Stratford Road. Birmingham was one of the very few places in England which lived up to its motto – in this case, ‘Forward’. It was certainly going forward in the mid-sixties. Nowhere else was there more excitement in the air, and no other major British city had identified its problems, tackled them and made more progress towards solving them than ‘the second city’. Not even in London was there so much adventure in what was being done.

The danger, however, was that all this central enterprise would distract the city from looking too closely at its unfulfilled needs. Life in Sparkbrook or Balsall Heath didn’t look nearly as prosperous as it did from St Martin’s. Birmingham could have done itself more good by concentrating more on its tatty central fringes, what became known in the seventies and eighties as its inner-city areas. Something like seventy thousand families were in need of new homes and since the war it had been building houses at a rate of no more than two to three thousand a year. This compared poorly with Manchester, otherwise a poor relation, which had been building four thousand a year over the same period. However, more than any other municipality in the country, Birmingham had pressed successive ministers of Housing and Local Government to force lodging-house landlords to register with their local authorities. In 1944, it was the only place in England to take advantage of an ephemeral Act of Parliament to acquire the five housing areas it then developed twenty years later. At Ladywood, Lee Bank, Highgate, Newton and Nechells Green, 103,000 people lived in 32,000 slum houses; a mess sprawling over a thousand acres, only twenty-two acres of which were open land. More than ten thousand of these houses had been cleared by 1964, and it was estimated that by 1970 the total number of people living in these areas was expected to dwindle to fifty thousand, with their homes set in 220 acres of open ground.

The other tens of thousands of people who lived there were expected to have moved out to Worcester, Redditch and other places. The prospect of Birmingham’s excess population being deposited in large numbers on the surrounding countryside was not an attractive one for those who were on the receiving end of this migration. At the public enquiry into the proposals to establish a new town at Redditch, the National Farmers’ Union (NFU) declared, with the imagery that pressure groups often resort to when their interests are threatened, that the farmers were being sacrificed on the altar of Birmingham’s ‘overspill’, which was the latest password among the planners. Birmingham needed to clear its slums before it could start talking about itself with justification as the most go-ahead city in Europe. Yet it already, in the mid-sixties, felt much more affluent than the patchwork affair among more northern towns and cities. It had more in common with the Golden Circle of London and the Home Counties than any other part of England. In 1964, forty-seven per cent of its industrial firms reported increased production compared with the national average of twenty-five per cent. Above all, Birmingham felt as if everything it set itself to was geared to an overall plan and purpose, with no piecemeal efforts going to waste at a tangent. The people living in Birmingham in the mid-sixties had a feeling, rare in English life at that time, of being part of an exciting enterprise destined to succeed. As for the city itself, it was not prepared to yield pride of place to anyone on any matter, as a quick glance at the civic guide revealed.

Immigration: The Case of Smethwick in 1964.

The Black Country outside Birmingham may have appeared to have been standing still for a century or more, but by looking at its population it was possible to see that an enormous change had come over it in the late fifties and early sixties. The pallid, indigenous people had been joined by more colourful folk from the West Indies, India and Pakistan. In some cases, the women from the subcontinent could not speak English at all, but they had already made their mark on Black Country society, queuing for chickens on Wolverhampton market on Saturday mornings. The public transport system across Birmingham and the Black Country would certainly have ground to a halt had the immigrant labour which supplied it been withdrawn. Several cinemas had been saved from closing by showing Indian and Pakistani movies, and a Nonconformist Chapel had been transformed into a Sikh Gurdwara. The whole area was ‘peppered’ with Indian and Pakistani restaurants.

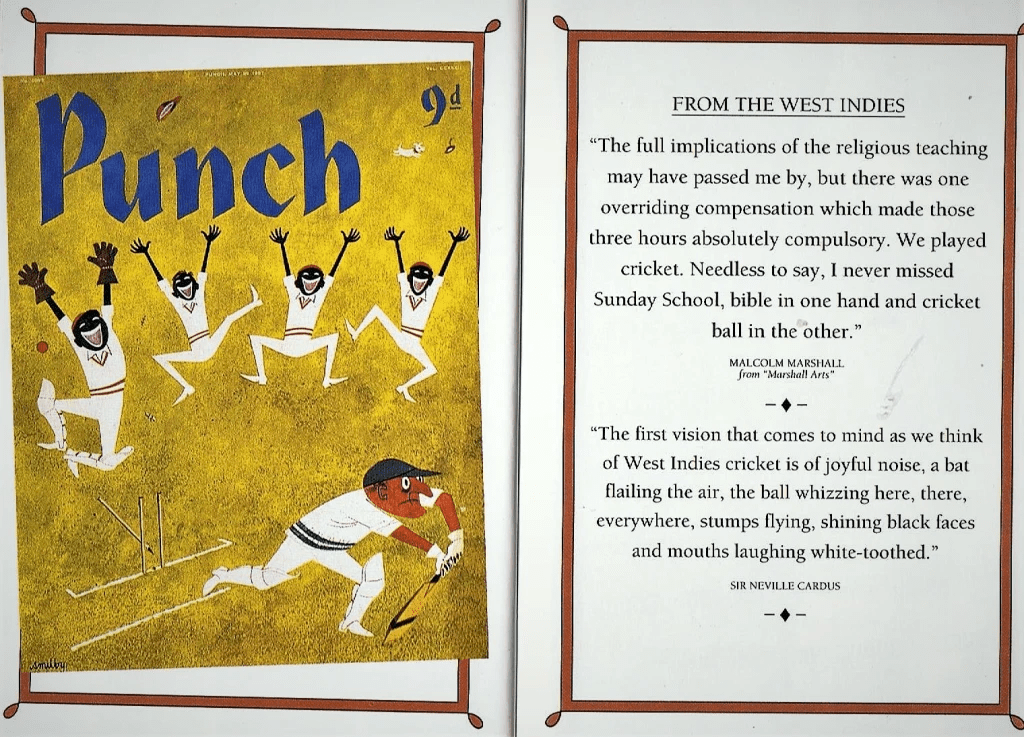

The newcomers also made an immediate impact on sporting life in Birmingham. Several years before the national press discovered the West Indian cricket supporters at Lord’s in 1963, they were already plainly visible and vocal at Edgbaston Cricket Ground. The cover of ‘Punch’ from May 1957 mirrors the stereotypical image described by Sir Neville Cardus (below right). I watched many of their top-class cricketers playing for Warwickshire and Worcestershire from the late 1960s, and those of lesser abilities playing in local leagues.

The overseas immigrants had been coming into Birmingham and the Black Country in a steady trickle since the end of the war for the same reason that the region attracted migrants from all over the British Isles since the mid-twenties: comparatively high wages and full, stable, employment. The trickle became a torrent in the months before the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill was enacted in 1962. By 1964, the region had one of the biggest concentrations of immigrants in the country. Their integration into the communities of Birmingham and the Black Country had proceeded without the violent reaction which led to the race riots in Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958. But tensions had been building up in the region as they had in every mixed community in Britain. One of the first open antagonisms took place in Birmingham in 1954 over the employment of coloured migrants as drivers and conductors on the local buses. After that, little was heard of racial pressures until the end of 1963, when events in Smethwick began to make national headlines. The situation there became typical in its effects on traditional allegiances, and in its ripeness for exploitation, of that in every town in England with a mixed community.

With a population of seventy thousand, Smethwick contained an immigrant community variously estimated at between five and seven thousand. It was claimed that this was proportionately greater than in any other county borough in England. The settlement of these people in Smethwick had not been the slow process over a long period that Liverpool, Cardiff and other seaports had experienced and which had allowed time for adjustments to be made gradually. It had happened at a rush, mainly at the end of the fifties and the beginning of the sixties. In such circumstances, the host communities learnt to behave better, but it was always likely that a deeply rooted white population would regard with suspicion the arrival of an itinerant coloured people on its home ground, and that friction would result. In Smethwick, the friction followed a familiar pattern. Most pubs in the town barred coloured people from their lounge bars. Some barbers refused to cut their hair. When a Pakistani family were allocated a new council flat after slum clearance in 1961, sixty-four of their white neighbours staged a rent strike and eventually succeeded in driving them out of, ironically enough, ‘Christ Street’.

Peter Griffiths MP, in his maiden speech to the Commons, pointed out what he believed were the real problems his constituency faced, including factory closures and over 4,000 families awaiting council accommodation. But in 1965, Wilson’s new Home Secretary, Frank Soskice, tightened the quota system, cutting down on the number of dependents allowed in, and giving the Government the power to deport illegal immigrants. At the same time, it offered the first Race Relations Act as a ‘sweetener’. This outlawed the use of the ‘colour bar’ in public places and by potential landlords, and discrimination in public services, also banning incitement to racial hatred like that seen in the Smethwick campaign. At the time, it was largely seen as toothless, yet the combination of restrictions on immigration and the measures to better integrate the migrants already in Britain did form the basis for all subsequent policy.

When I went to live in Edgbaston with my family from Nottingham in 1965, Birmingham’s booming postwar economy had not only attracted its ‘West Indian’ settlers from 1948 onwards, but had also ‘welcomed’ South Asians from Gujarat and Punjab in India, and East Pakistan (Bangladesh) both after the war and partition, and in increasing numbers from the early 1960s. The South Asian and West Indian populations were equal in size and concentrated in the inner city wards of the city and in West Birmingham, particularly Sparkbrook and Handsworth, as well as in Sandwell (see map below; then known as Smethwick and Warley). Labour shortages had developed in Birmingham as a result of an overall movement towards skilled and white-collar employment among the native population, which created vacancies in less attractive, poorly paid, unskilled and semi-skilled jobs in manufacturing, particularly in metal foundries and factories, and in the transport and healthcare sectors of the public services. These jobs were filled by newcomers from the Commonwealth.

But if there were clear rules about how to migrate quietly to Britain, they would have stated first, ‘be white’, and second, ‘if you can’t be white, be small in number’, and third, ‘if all else fails, feed the brutes’. The West Indian migration, at least until the mid-eighties, failed each rule. It was mainly male, young and coming not to open restaurants but to work for wages which could, in part, be sent back home. Some official organisations, including the National Health Service and London Transport, went on specific recruiting drives for drivers, conductors, nurses and cleaners, with advertisements in Jamaica. Most of the population shift, however, was driven by the migrants themselves, desperate for a better life, particularly once the popular alternative migration to the USA was closed down in 1952. The Caribbean islands, dependent on sugar or tobacco for most employment, were going through hard times. As word was passed back about job opportunities, albeit in difficult surroundings, immigration grew fast to about 36,000 people a year by the late fifties. The scale of the change was equivalent to the total non-white population of 1951 arriving in Britain every two years. The black and Asian population rose to 117,000 by 1961. Although these were still comparatively small numbers, from the first, they were concentrated in particular localities, rather than being dispersed.

The means and ways by which these people migrated to Britain had a huge impact on the later condition of post-war society and deserves special, detailed analysis. The fact that so many of the first migrants were young men who found themselves living without wives, mothers and children inevitably created a wilder atmosphere than they were accustomed to in their island homes. They were short of entertainment as well as short of the social control of ordinary family living. The chain of generational influence was broken at the same time as the male strut was liberated. Drinking dens and gambling, the use of marijuana, and ska and blues clubs were the results. Early black communities in Britain tended to cluster where the first arrivals had settled, which meant in the blighted inner cities. There, street prostitution was more open and rampant in the fifties than it was later, so that it is hardly surprising that young men away from home for the first time often formed relationships with prostitutes, and that some became pimps themselves. This was what fed the popular press’s hunger for stories to confirm their prejudices about black men stealing ‘our women’. The upbeat, unfamiliar music, illegal drinking and drugs and the sexual appetites of the young immigrants all combined to paint a lurid picture of a new underclass.

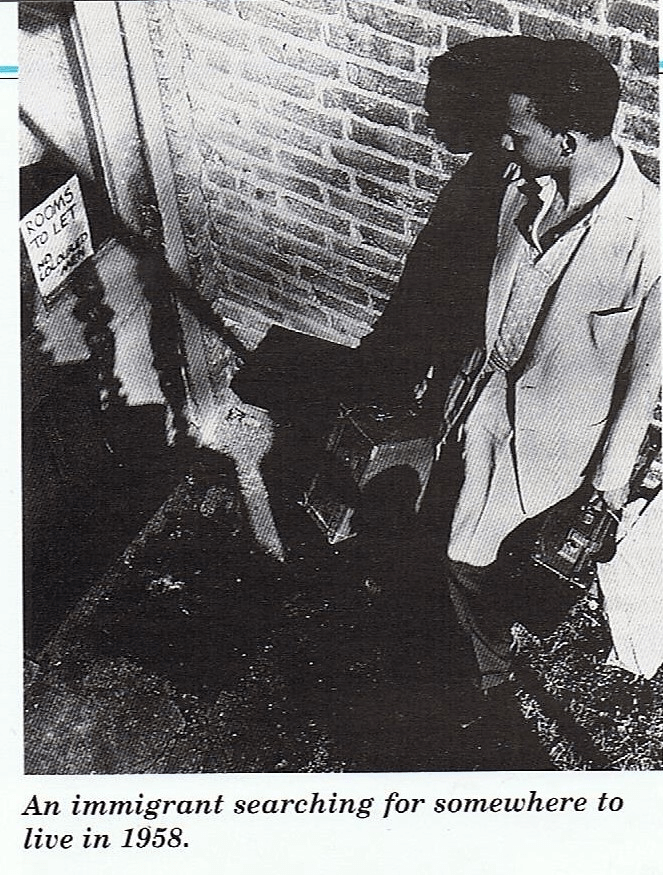

As a consequence, landlords and landladies became more reluctant to rent to ‘blacks’. Once a few houses had immigrants in them, a domino effect would clear streets as white residents sold up and shipped out. The 1957 Rent Act, initiated by Enoch Powell, in his free-market crusade, perversely made the situation worse by allowing rents to rise sharply, but only when tenants of unfurnished rooms were removed to allow for furnished lettings. Powell had intended to instigate a period during which rent rises could be cushioned, but its unintended consequence was that unscrupulous landlords such as the notorious Peter Rachman, himself an immigrant, bought up low-value properties for letting, ejecting the existing tenants and replacing them with new tenants, packed in at far higher rents. Thuggery and threats generally got rid of the old, often elderly, white tenants, to be replaced by the new black tenants who were desperate for somewhere to live and therefore prepared to pay the higher rents they were charged. The result was the creation of instant ghettos in which three generations of black British would soon be crowded together. Ironically, it was the effects of Enoch Powell’s housing policies of the fifties which led directly to the Brixton, Tottenham, Toxteth and Handsworth riots of the eighties.

Henry Gunter & the colour bar; Charles Parker & The Colony:

The archive collections at the Library of Birmingham hold material which sheds light on the experiences of those newly arrived in the UK between the 1940s and 1970s.

(ref MS 2165/1/3)

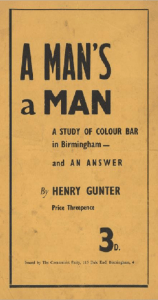

Henry Gunter was born in Jamaica but moved to the UK in 1950, which was only two years after the Empire Windrush arrived. Gunter, as a campaigner against racism and injustice, was at the forefront of issues that black people making a new life in Birmingham were facing. He wrote about the colour bar in housing, whereby local people refused to give housing to black people. His campaigning activities involved writing articles to educate the white residents, as he believed that the problems with local people were mostly due to fear based on ignorance of the minority population. Gunter became President of a group called the Afro-Caribbean Organisation.

He aimed to win influence with the Labour movement and other bodies to break down the colour bar. Although hospitals in Birmingham had welcomed workers from Commonwealth countries, the City Transport department refused to employ black workers. Gunter organised a march through Birmingham City Centre with banners with slogans including ‘No Colour Bar to housing and jobs.’ His campaigning eventually led to the employment of black people as conductors and ultimately to their full integration into the transport system. At least one of these conductors became well-known and well-loved for his singing of hymns and songs while serving his customers on the buses.

The Charles Parker Archive is another collection where the experiences of Commonwealth citizens living in Birmingham are documented. The archive holds material relating to Philip Donnellan’s documentary film The Colony. First broadcast in June 1964, the film consists of interviews with working-class black people living in Birmingham. It is notable that there is no commentary or narration. This allowed the interviewees’ experiences (in their own words) to be the focus of the programme. Charles Parker was responsible for the voice montages, one of which is quoted here:

“… a land which we felt in coming, we were proud to come and we felt that coming here we would be at home.”

He also spoke about his contrasting experiences in dealing with English people in daily interactions and when trying to procure services:

“I must say, the people in the street that you meet, the bus conductors and the working men that you meet in the street are quite friendly, they would do anything for you. The snag is when it comes to the people around where you live.”

He then went on to explain a specific encounter in Rotten Park when he was trying to find accommodation:

“There was one house in City Road that advertised accommodation for three or four working men. So I rung them up, and at the end of the line was a woman’s voice. She said “Yes, we have beds for three or four working men”, so to make sure I told her I was a West Indian, she said “Just a minute” and she came back to the ‘phone and she said “Sorry we are filled up”, and it went on like that, … all the while.”

These documentary collections show that, alongside the challenge of leaving their island homes, making a long journey and building a new life in Birmingham, Caribbean migrants had far greater challenges to face when they arrived. Many of them persevered and some, like Henry Gunter, campaigned to improve conditions. They all contributed to enriching the communities in which they came to live.

Yet ‘nativist’ prejudice and resistance were only direct causes of the racial tensions and explosions which were to follow. The others lay in the reactions of the white British, or rather the white English middle classes. Benjamin Zephaniah (see below) later argued that Welsh should be taught in English schools to show that there was more than one indigenous ‘white’ culture in Britain besides the Anglo-Saxon one. Another Caribbean writer claimed, with not a touch of tongue-in-cheek irony, that he had never met a single English person with colour prejudice. Once he had walked the entire length of a street,…

… and everyone told me that he or she ‘ad no prejudice against coloured people. It was the neighbour who was stupid. If only we could find the “neighbour”, we could solve the whole problem. But to find ‘im is the trouble. Neighbours are the worst people to live beside in this country.

Numerous testimonies by immigrants and in surveys of the time show how hostile people were to the idea of having black or Asian neighbours. This forced the newcomers to settle further away from the ‘white’ inner-city suburbs like Edgbaston and Rotten Park to the north and west, to the more working-class districts of Handsworth and Smethwick, where there were already significant numbers of ‘Windrush’ migrants, mixing with more settled ‘white’ migrants from previous generations. It was not just in finding accommodation that the ‘newcomers’ faced discrimination, but also in finding employment. The trade unions bristled against blacks coming in to take jobs, potentially at lower rates of pay, just as they had complained about Irish or Welsh migrants a generation earlier. Union leaders who were otherwise regarded as impeccably left-wing lobbied governments to keep out black workers. For a while, it seemed that they would be successful enough by creating employment ghettos as well as housing ones, until black workers gained a foothold in the car-making and other manufacturing industries, where previous generations of immigrants had already fought battles for acceptance against the old craft unionists and won.

Only a handful of MPs campaigned openly against immigration. Even Enoch Powell would, at this stage, only raise the issue in private meetings, though he had been keen enough, as health minister, to make use of migrant labour for the National Health Service. The anti-immigrant feeling was regarded as not being respectable, not something that a decent politician was prepared to talk about. The Westminster élite talked in well-meaning but stereotypical generalities of the immigrants as being fellow subjects of the Crown. Most of the hostility was at the level of the street and popular culture, usually in the form of the thinly disguised discrimination of shunning, through to the constant humiliation of door-slamming and on to more overtly violent street attacks.

The natural rebelliousness among young, male Caribbean migrants would be partly tamed only when children and spouses began to arrive in large numbers in the sixties, and the Pentecostal churches reclaimed at least some of their own, sending out their gospel groups to entertain as well as evangelise among the previously lily-white but Welsh immigrant-led nonconformist chapels in the early seventies. Housing was another crucial part of the story. For the immigrants of the fifties, accommodation was necessarily privately rented, since access to council homes was based on a long list of existing residents. So the early black immigrants, like the earlier immigrant groups before them, were cooped up in crowded, often condemned Victorian terrace properties in Handsworth and west Birmingham.

By 1964, the West Birmingham region had one of the biggest concentrations of immigrants in the country. Their integration into the communities of Birmingham and the Black Country had proceeded without the violent reaction which led to the race riots in Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958. But tensions had been building up in the region as they had in every mixed community in Britain. One of the first open antagonisms occurred in Birmingham in 1954 over the employment of black migrants as drivers and conductors on the local buses. After that, little was heard of racial pressures until the end of 1963, when events in Smethwick began to make national headlines. The situation there became typical in its effects on traditional allegiances and in its ripeness for exploitation, as in every town in England with a mixed community.

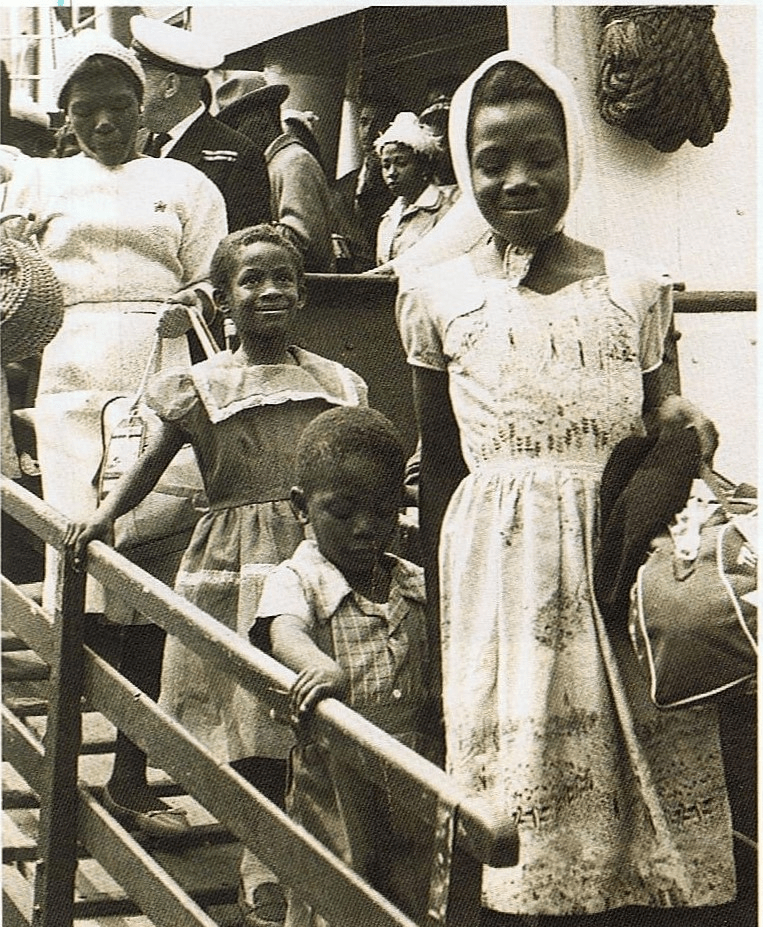

The Singing Stewarts– Britain’s First Gospel Group:

Attempting to counter this petty prejudice, the first black Gospel group to make an impact in Britain were ‘The Singing Stewarts’. They were originally from Trinidad and Aruba, where the five brothers and three sisters of the Stewart family were born. They migrated to Handsworth in Birmingham in 1961, part of the second major wave of Windrush migrants who came to Britain just before the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1962 ended the ‘open door’ policy for British overseas nationals. This was the period when many families were settling in Britain, many rejoining ‘menfolk’ who had come on their own some years earlier (see picture below). Many people moved to Britain before the Act was passed because they thought it would be difficult to get in afterwards. Immigration doubled from fifty-eight thousand in 1960 to over 115,000 in 1961, and to nearly 120,000 in 1962. The Stewarts were all members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and under the training of their strict and devoted mother, began to sing in an a cappella style songs that mixed traditional Southern gospel songs written by composers like Vep Ellis and Albert Brumley. To this material, they added a distinctly Trinidadian calypso flavour and by the mid-sixties were performing all around the Midlands. In later years, they were joined by a double bass affectionately referred to as ‘Betty’. From childhood growing up in the church, they would refuse all offers to sing ‘secular’ music.

Settling in Handsworth, they quickly made a name for themselves in West Birmingham and what is known as Sandwell today (then as Smethwick and Warley), especially among the nonconformist churches where most of the Caribbean immigrant families were to be found. They also appeared at a variety of cross-cultural events and at institutions such as hospitals, schools and prisons, as well as in other churches. They performed on local radio and TV, which brought them to the attention of a local radio producer and folk-music enthusiast Charles Parker, who heard in the group’s unlikely musical fusion of jubilee harmonies, Southern gospel songs and a Trinidadian flavour something unique. In 1964, they were the subject of a TV documentary produced by him, which brought them to national attention. Parker helped them to cultivate their talent and to become more ‘professional’, opening them up to wider audiences. They took his advice and guidance on board and reaped dividends on the back of their TV appearances and national and European tours that increased their exposure and widened their fan base. The most significant TV project was a documentary entitled ‘The Colony’, broadcast in June 1964. It was the first British television programme to give a voice to the new working-class Caribbean settlers.

For a while, in the early sixties, they were the only black Gospel group in the UK media spotlight. It was difficult to place them in a single category at the time, as they sang both ‘negro spirituals’ and traditional Gospel songs, which made them a novelty to British and European audiences. The Singing Stewarts were able to undertake a European tour where they played to crowds of white non-churchgoers. Thousands warmed to them, captivated by their natural and effortless harmonies. They possessed a remarkable ability to permeate cultural barriers that was unprecedented at the time, due to the racial tensions which existed in West Birmingham, Warley and Smethwick in the sixties and seventies, stirred up by the local and national election campaigns in Smethwick run by the National Front.

The dark experience of mid-sixties Smethwick:

With a population of seventy thousand, Smethwick contained an immigrant community variously estimated at between five and seven thousand. It was claimed that this is proportionately greater than in any other county borough in England. The settlement of these people in Smethwick had not been the slow process over a long period that Liverpool, Cardiff and other seaports had experienced and which had allowed time for adjustments to be made gradually, though Cardiff in particular had seen some of the earliest race riots in Britain. In West Birmingham, large-scale immigration had happened at a rush, mainly at the end of the fifties and the beginning of the sixties. In such circumstances, the host communities learnt to behave better, but it was always likely that a deeply rooted white population would regard with suspicion the arrival of an itinerant coloured people on its home ground, and that friction would result. In Smethwick, the friction followed a familiar pattern. Most pubs in the town barred coloured people from their lounge bars. Some barbers refused to cut their hair. When a Pakistani family were allocated a new council flat after slum clearance in 1961, sixty-four of their white neighbours staged a rent strike and eventually succeeded in driving them out of, ironically enough, ‘Christ Street’.

Most of the usual white prejudices were keenly displayed in Smethwick, the reasons offered for hostility to the migrants being that they made too much noise, that they did not tend to their gardens with the customary English care, that they left their children unattended too long, and that their children were delaying the progress of white pupils in the schools. The correspondence columns of the local weekly newspaper, the Smethwick Telephone, provided a platform for the airing of these prejudices, as a letter quoted by a correspondent of The Times on 9 March 1964 shows:

With the advent of the pseudo-socialists’ ‘coloured friends’, the incidence of T.B. in the area has risen to become one of the highest in the country. Can it be denied that the foul practice of spitting in public is a contributory factor? Why waste the ratepayers’ money printing notices in five different languages? People who behave worse than animals will not in the least be deterred by them.

No one seems to know who originated the slogan: If you want a Nigger for a neighbour, vote Labour, which was circulating in Smethwick before the 1963 municipal elections. The Conservatives were widely reported as using the slogan but Colin Jordan, leader of the neo-Nazi British Movement, claimed that his members had produced the initial slogan as well as spread the poster and sticker campaign; Jordan’s group in the past had also campaigned before on similar but less ‘catchy’ slogans, such as: Don’t vote – a vote for Tory, Labour or Liberal is a vote for more Blacks! Griffiths denied that the slogan was racist, saying that:

I should think that is a manifestation of the popular feeling. I would not condemn anyone who said that. I would say that is how people see the situation in Smethwick. I fully understand the feelings of the people who say it. I would say it is exasperation, not fascism.

— quoted in The Times (9 March 1964).

The specific issue which the Labour and Conservatives debated across the Smethwick council chamber was how best to integrate immigrant children in the borough’s schools. Many of them had very little English when they arrived in Smethwick. The Conservatives wanted to segregate them from normal lessons; Labour took the view that they should be taught in separate groups for English only and that the level of integration otherwise should be left to the discretion of the individual schools. But the party division soon got far deeper as the housing shortage in Smethwick, as great as anywhere in the Black Country, exacerbated race relations. The Conservatives said that if they controlled the council, they would not necessarily re-house a householder on taking over his property for slum clearance unless he had lived in the town for ten years or more. While the local Labour party deprecated attempts to make immigration a political issue, the Conservatives actively encouraged them. Councillor Peter Griffiths, the local Tory leader, had actively supported the Christ Street Rent Strike.

At the municipal elections in 1963, the Conservatives fared disastrously over the country in general, gaining no more than five seats. Three of these were in Smethwick. In the elections for aldermen of 1964, the Conservatives gained control of the council, the ‘prize’ for having been consistently critical of the immigrant community in the area. The Smethwick constituency had been held by Labour since 1945, for most of that time by Patrick Gordon-Walker, Labour’s Shadow Foreign Secretary. His majorities at successive general elections had dwindled from 9,727 in 1951 to 6,495 in 1955 to 3,544 in 1959. This declining majority could not, obviously, be solely attributed to Labour’s policy on immigration, either nationally or locally. It reflected a national trend since 1951, a preference for Tory economic management. But the drop in 1959 seemed to be in part, at least, a reaction to local issues. Moorhouse, writing in mid-1964, just before the general election, found few people who would bet on Gordon-Walker being returned to Westminster, however successful Labour might be in the country as a whole. His opponent in the election was Councillor Griffiths, who was so convinced of the outcome by the end of 1963 that he had already fixed himself up with a flat in London. Moorhouse wrote:

If he does become Smethwick’s next MP it will not simply be because he has attracted the floating voter to his cause. It will also be because many people who have regarded themselves as socialist through thick and thin have decided that when socialism demands the application of its principles for the benefit of a coloured migrant population as well as for themselves it is high time to look for another political creed which is personally more convenient.

There had been resignations from the party, and a former Labour councillor was already running a club which catered only for ‘Europeans’. The Labour Club itself (not directly connected to the constituency party) had not, by the end of 1963, admitted a single coloured member. Smethwick in 1964 was not, as Moorhouse commented, a place of which many of its inhabitants could be proud, regardless of how they voted. That could be extended to ‘any of us’, he wrote:

We who live in areas where coloured people have not yet settled dare not say that what is happening in Smethwick today could not happen in our slice of England, too. For the issue is not a simple and straightforward one. There must be many men of tender social conscience who complain bitterly about the noise being imposed on them by road and air traffic while sweeping aside as intolerant the claims others about the noise imposed on them by West Indian neighbours, without ever seeing that there is an inconsistency in their attitude.

It is not much different from the inconsistency of the English parent who demands the segregation of coloured pupils whose incapacities may indeed be retarding his child’s school progress but who fails to acknowledge the fact that in the same class there are probably a number of white children having a similar effect. One issue put up by Smethwick (and the other places where social problems have already arisen) does, however, seem to be clear. The fact is that these people are here and, to put it at the lowest level of self-interest, we have got to live amicably with them if we do not want a repetition of Notting Hill and Nottingham, if we do not want a coloured ghetto steadily growing in both size and resentment. …

Smethwick is our window on the world from which we can look out and see the street sleepers of Calcutta, the shanty towns of Trinidad, the empty bellies of Bombay. And what do we make of it? Somebody at once comes up and sticks a notice in it. ‘If you want a Nigger neighbour, vote Labour.’

The 1964 general election result involved a nationwide swing from the Conservatives to the Labour Party, which had also resulted in the party gaining a narrow five-seat majority. However, in Smethwick, the Conservative candidate, Griffiths, gained the seat and unseated the sitting Labour MP, Patrick Gordon-Walker. Griffiths did, however, poll 436 votes less in 1964 than when he had stood unsuccessfully for the Smethwick constituency in 1959. He was declared “a parliamentary leper” by Harold Wilson, the new Labour Prime Minister (pictured below).

Griffiths, in his maiden speech to the Commons, pointed out what he believed were the real problems his constituency faced, including factory closures and over 4,000 families awaiting council accommodation. The election result led to a visit by Malcolm X to Smethwick to show solidarity with the black and Asian communities. Malcolm’s visit to Smethwick was “no accident”; the Conservative-run council attempted to put in place an official policy of racial segregation in Smethwick’s housing allocation, with houses on Marshall Street in Smethwick being let only to white British residents.

The militant Black American Civil Rights leader claimed that the Black minorities were being treated like the Jews under Hitler. Later in 1964, a delegation of white residents successfully petitioned the Conservative council to compulsorily purchase vacant houses in order to prevent non-whites from buying the houses. This, however, was prevented by Labour housing minister Richard Crossman, who refused to allow the council to borrow the money in order to enact their policy. Nine days after he visited Marshall Street, Malcolm X was shot dead in New York. The Labour Party regained the seat at the 1966 general election when Andrew Faulds, a local candidate, became the new Member of Parliament.

The actions taken in Smethwick in 1964 have been characterised as ugly Tory racism, which killed rational debate about immigration. However, colour bars were then common, preventing non-whites from using facilities. The Labour movement itself also had much to learn. The Labour Club in Smethwick effectively operated its own bar, as, more overtly, did the local Sandwell Youth Club, which was run by one of the town’s Labour councillors. Moorhouse pointed out that had the community been on the economic rocks, it might have been possible to make out a case for controls on immigration. Had there been a high rate of unemployment, where the standard of living was already impoverished, there might have been a case for keeping migrants at bay so as to prevent competition for insufficient jobs becoming greater and the general sense of depression from deepening.

But that was not the case in West Birmingham and the Black Country in 1964, or for at least another decade. It may have been as ugly as sin to look at, at least in parts, but outside the Golden Circle around London, there was no wealthier area in England and no place more economically stable. When the Birmingham busmen had objected to coloured colleagues a decade earlier, it was not because these would be taking jobs which might otherwise have gone to ‘Brummies’ but because it was feared they might have an effect on wages which a shortage of labour had maintained at an artificial level. These were real fears that had led to prejudice against previous immigrants to the region, most notably from Wales in the thirties and Ireland in the forties. At root, this was not a problem about colour per se, though, in the early sixties. It was essentially about wages, but racist sentiments were never far from the surface. This is how Anthony Richmond summarised it in his book The Colour Problem:

The main objections to the employment of coloured colonials appeared to come from the trade unions, but less on the grounds of colour than because, if the number of drivers and conductors was brought up to full establishment by employing colonials, their opportunities for earning considerable sums as overtime would be reduced.

Restrictive practices kept out the new Commonwealth immigrants, who lacked access to channels of information and influence, especially as they were usually barred from pubs and clubs in any case. These practices were common throughout the industrial West Midlands. The engineering workers of the West Midlands had their hierarchies, and while many were changing districts, occupations, and factories all the time, the newly arrived immigrants were at the bottom of the tree and unlikely to topple it or undermine the benefits it provided for those near the top.

Therefore, the case of Smethwick in 1964 cannot easily be explained by reference to economic factors, though we know that the social and cultural factors surrounding the issues of housing and education did play significant roles. The main factor underpinning the 1964 Election result would appear to be political, that it was still acceptable, at that time and among local politicians of both main parties, together with public and trade union officials, for racial discrimination and segregation to be seen as instruments of public policy in response to mass immigration. In this, Smethwick was not that different from other towns and cities throughout the West Midlands, if not from those elsewhere in England. And it would take a long time for such social and industrial hierarchies to be worn down through local and national government intervention which went ahead of, and sometimes cut across the ‘privileged’ grain of indigenous populations. Smethwick represented a turning point in this process; four years later Wolverhampton and Birmingham would become the fulcrum in the fight against organised racialism.

Rivers of Babylon to Rivers of Blood – Happy Days & Darkest Nights:

By the mid-sixties, British record companies had become more alert to the commercial potential of US gospel music, and began to look around for a British-based version of that music and in 1968, the Singing Stewarts were signed to PYE Records. The following year, they were the first British gospel group to be recorded by a major record company when PYE Records released their album Oh Happy Day. Cyril Stapleton, PYE Records’ leading A&R executive and a legendary big band conductor, had invited the family to his London studio, where he produced the new classic and extremely rare album. Hardly surprisingly, the Singing Stewarts’ single of “Oh Happy Day” didn’t sell, since pop fans were already familiar with the version by the Edwin Hawkins’ Singers from the US. Nor did the album sell well, partly because it was given the clumsy, long-winded title of Oh Happy Day And Other West Indian Spirituals Sung By The Singing Stewarts. It was released on the budget line Marble Arch Records. However, in 1969, they appeared at the Edinburgh Festival, where they were exposed to a wider and more musically diverse public. Their folksy Trinidadian flavour delighted the arts festival-goers. The family went on to make more albums, which sold better, but they never wavered from their original Christian message and mission. They continued to sing at a variety of venues, including many churches, performing well into retirement age. Neither did they compromise their style of music, helping to raise awareness of spirituals and gospel songs. They were pioneers of the British Black Gospel Scene and toured all over the world, helping to put Caribbean black gospel music on the map.

My own experience of ‘The Singing Stewarts’ came in 1971 as a fourteen-year-old at the Baptist Church in Bearwood, Warley, where my father, Rev. Arthur J. Chandler, was the first minister of the newly-built church, an offshoot of Smethwick Baptist Church (below). We had moved to Birmingham in 1965 for its opening and my father’s induction, and by that time, West Birmingham and Sandwell, as Smethwick and Warley were now known, were becoming multi-cultural areas with large numbers of Irish, Welsh, Polish, Yugoslav, Indian, Pakistani and Caribbean communities.

My grammar school, from 1968, on City Road in Edgbaston, was a two-mile walk away, and was like a microcosm of the United Nations. In the early seventies, it appointed one of the first black head boys in Birmingham, and was also a community of many faiths, including Anglicans, Nonconformists, Catholics, Greek Orthodox Cypriots, Sikhs, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, as well as many followers of ‘Mammon’! Our neighbourhood, which ran along the city boundary between Birmingham and the Black Country in Edgbaston (the ‘border’ was literally at the end of the Manse garden), was similarly mixed, though still mostly white. Birmingham possessed a relatively wealthy working class, due to the car industry, so the distinctions between the working class and middle-class members of our church were already blurred. There were no more than a handful of ‘West Indian’ members of the congregation at that time, from the mid-sixties to mid-seventies, though after my father retired in 1979, it shared its premises with one of the new black-led congregations. During the sixties and seventies, there were also more black children in the Sunday School, Boys’ and Girls’ Brigades and the Youth Club. These children and youths were especially popular when we played sports against other Baptist congregations in the West Birmingham area.

The Stewart Family came to our church, at my father’s invitation, in 1970. Previously, my experience of Gospel music had been limited to singing a small number of well-known spirituals, calypso and gospel songs in the school choir. I guess I must also have heard some of the renditions by Pete Seeger and popular English folk groups on the radio and TV. Most of the ‘pop’ songs performed by ‘northern soul’ singers seemed, however, massively over-produced, and even the ‘folk songs’ sung by white folk seemed to lack authenticity. I hadn’t heard a group sing a cappella before, and I felt inspired and moved by the whole experience, transformed by the deep ‘well-spring’ of joy that, as I learned later, the Welsh call ‘hwyl’ (there isn’t a single English word that does this emotion justice). At the end of the ‘service’, a ‘call’ to commitment was made, and I found myself, together with several others, standing and moving forward to receive God’s grace.

This was unlike any other experience in my Christian upbringing to that date. The following Whitsun, in 1971, I was baptised and received into church membership. In 1974, a group of us from Bearwood and south Birmingham, who had formed our own Christian folk-rock group, attended the first Greenbelt Christian Music Festival, where Andrae Crouch and the Disciples were among the ‘headline acts’. Thus began a love affair with Gospel music of various forms, which has endured ever since. We were inspired by this event to write and perform our own musical based on the Book of James, which we toured around the Baptist churches in West and South Birmingham.

The service led by the Stewart Singers in Bearwood also began, more importantly, my own ministry of reconciliation. I have heard and read many stories about the coldness displayed by many ‘white Anglo-Saxon’ churches towards the Windrush migrants, and they make me feel shame even now that we did not do more to challenge prejudiced behaviour, at least in our own congregations, and among our fellows. However, I also feel that it is all too easy for current generations to judge the previous ones. You only have to look at what was happening in the southern United States and in ‘apartheid’ South Africa to see that this was a totally different time in the life of the Church in many parts of the world. It was not that many Christians were prejudiced against people of colour, though some were, or that they were ‘forgetful to entertain strangers’. Many still believed sincerely, though wrongly (as we now know from Science), that God had created separate races to live separately. In its extreme forms, this led to the policies of ‘separate development’ of the South African state, underpinned by the strict Calvinist theology of the Dutch Reformed Church, and the belief in, and practice of, ‘segregation’, supported by Southern Baptists and others in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement was at its height in the US, in Birmingham, Alabama, but it was still far removed in its influence on the ‘white’ churches in Birmingham, England.

To defend themselves against prejudice, immigrants to Birmingham continued to congregate in poorer inner city areas or in the western suburbs along the boundary with Smethwick, Warley, West Bromwich (now Sandwell), and Dudley, where many of them also settled. There was a small South Asian presence of about a hundred in Birmingham before the war, and this had risen to about a few thousand by the end of the war. But these were mainly workers recruited by the Ministry of Labour to work in the munitions factories, like Tangyes in Smethwick. Birmingham’s booming postwar economy had first attracted West Indian settlers from Jamaica, Barbados and St Kitts in the 1950s, and was only followed by South Asians from Gujarat and the Punjab in India, and then from Bangladesh from the mid-1960s onwards.

Many of these newcomers were refugees from post-colonial conflicts in East Africa. The 1968 Immigration Act was specifically targeted at restricting Kenyan Asians with British passports. As conditions grew worse for them in Kenya, many of them decided to seek refuge in the ‘mother country’ of the Empire, which had colonised them in the first place. Through 1967, they were coming in by plane at the rate of about a thousand per month. The newspapers began to depict the influx on their front pages, and the television news, by now watched in most homes, showed great queues waiting for British passports and flights. It was at this point that Enoch Powell, Conservative MP for Wolverhampton, in an early warning shot, said that half a million East African Asians could eventually enter, which was ‘quite monstrous’.

He called for an end to work permits and a complete ban on dependants coming to Britain. Other prominent Tories, like Ian Macleod, argued that the Kenyan Asians could not be left stateless and that the British Government had to keep its promise to them. The Labour government was also split on the issue, with the ‘liberals’, led by Roy Jenkins, believing that only Kenyatta could halt the migration by being persuaded to offer better treatment. However, the new Home Secretary, Jim Callaghan, was determined to respond to the concerns of Labour voters about the unchecked migration.

By the end of 1967, the numbers arriving per month had doubled to two thousand. In February, Callaghan decided to act. The Commonwealth Immigrants Act effectively slammed the door while leaving a ‘cat flap’ open for a very small annual quota, leaving some twenty thousand people ‘stranded’ and stateless in a country, Kenya, which no longer wanted them. The bill was rushed through in the spring of 1968 and has been described as among the most divisive and controversial decisions ever taken by any British government. Some MPs viewed it as the most shameful piece of legislation ever enacted by Parliament, the ultimate appeasement of racist hysteria. The government responded with a tougher anti-discrimination bill in the same year. For many others, however, the passing of the act was the moment when the political élite, in the shape of Jim Callaghan, finally woke up and listened to their working-class voters.

Polls of the public showed that 72% supported the act. Never again would the idea of free access to Britain be seriously entertained by mainstream politicians. This was the backdrop to the notorious ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech made in Birmingham by Enoch Powell, in which he prophesied violent racial war if immigration continued. Powell had argued that the passport guarantee was never valid in the first place. Despite his unorthodox views, Powell was still a member of Edward Heath’s shadow cabinet which had just agreed to back Labour’s Race Relations Bill. But Powell had gone uncharacteristically quiet, apparently telling a local friend,

I’m going to make a speech at the weekend and it’s going to go up “fizz” like a rocket, but whereas all rockets fall to earth, this one is going to stay up.

The ‘friend’, Clem Jones, the editor of Powell’s local newspaper, The Wolverhampton Express and Star, had advised him to time the speech for the early evening television bulletins, and not to distribute it generally beforehand. He came to regret the advice. In a small room at the Midland Hotel on 20th April 1968, three weeks after the act had been passed and the planes carrying would-be Kenyan Asian immigrants had been turned around, Powell quoted a Wolverhampton constituent, a middle-aged working man, who told him that if he had the money, he would leave the country because, in fifteen or twenty years time, the black man will have the whip hand over the white man. Powell continued by asking rhetorically how he dared say such a horrible thing, stirring up trouble and inflaming feelings:

The answer is I do not have the right not to do so. Here is a decent, ordinary fellow-Englishman, who in broad daylight in my own town says to me, his Member of Parliament, that this country will not be worth living in for his children. I simply do not have the right to shrug my shoulders and think about something else. What he is saying, thousands and hundreds of thousands are saying and thinking … ‘Those whom the Gods wish to destroy, they first make mad.’ We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual flow of some fifty thousand dependants, who are for the most part the material growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping its own funeral pyre. …

… As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see “the river Tiber foaming with much blood”

Besides his classical allusion to Virgil, he also made various accusations, made by others among his Wolverhampton constituents, that they had been pestered and persecuted by ‘Negroes’, having excrement posted through their letter-boxes and being followed to the shops by children, charming wide-grinning pickaninnies chanting “Racialist.” If Britain did not begin a policy of voluntary repatriation, it would soon face the kind of race riots that were disfiguring America at that time. Powell claimed that he was merely restating Tory policy. But the rhetoric he used and his own careful preparation suggest it was a call to arms by a politician who believed he was fighting for white English nationhood, as well as a deliberate provocation aimed at Powell’s enemy, Heath.

After horrified consultations when he and other leading Tories had seen extracts of the speech on the television news, Heath promptly ordered Powell to phone him, and summarily sacked him. Heath announced that he found the speech racialist in tone and liable to exacerbate racial tensions. As Parliament returned three days after the speech, a thousand London dockers marched to Westminster in Powell’s support, carrying ‘Enoch is right’ placards; by the following day, Heath had received twenty thousand letters, almost all in support of Powell’s speech, with tens of thousands still to come. Smithfield meat porters and Heathrow airport workers also demonstrated in his support. In addition, Powell also received death threats and needed full-time police protection for a while; numerous marches were held against him, and he found it difficult to make speeches at or near university campuses. Asked whether he was a racialist by the Daily Mail, he replied:

We are all racialists. Do I object to one coloured person in this country? No. To a hundred? No. To a million? A query. To five million? Definitely.

Did most people in 1968 agree with him, as Andrew Marr has suggested? Certainly, many people believed in a theory of racial ‘difference’ and even a policy of ‘separate development’ at that time. It’s also important to point out that, until he made this speech, Powell had been a Tory ‘insider’, though seen as something of a maverick, and a trusted member of Edward Heath’s shadow cabinet. He had rejected the consumer society growing around him in favour of what he saw as a ‘higher vision’. This was a romantic dream of an older, tougher, swashbuckling Britain, freed of continental and imperial (now ‘commonwealth’) entanglements, populated by ingenious, hard-working white people rather like himself. For this to become a reality, Britain would need to become a self-sufficient island, which ran entirely against the great economic forces of the time. His view was fundamentally nostalgic, harking back to the energetic Victorian and Edwardian protectionists. He drew sustenance from the people around him, who seemed to be excluded from mainstream politics. He argued that his Wolverhampton constituents had had immigration imposed on them without being asked and against their will.

But viewed from Fleet Street or the pulpits of broadcasting, he was seen as an irrelevance, marching off into the wilderness. In reality, although immigration was changing patches of the country, mostly in west London, west Birmingham and the Black Country, it had, by 1968, barely impinged as an issue in people’s lives. That was why, at that time, it was relatively easy for the press and media to marginalise Powell and his acolytes in the Tory Party. He was expelled from the shadow cabinet for his anti-immigration speech, not so much for its racialist content, which was mainly given in reported speech, but for suggesting that the race relations legislation, which his leader and colleagues had publicly supported, was merely throwing a match on gunpowder. This statement was a clear breach of shadow cabinet collective responsibility. Besides, the legislation controlling immigration and regulating race relations had already been passed, so it is difficult to see what Powell had hoped to gain from the speech, apart from embarrassing his nemesis, Ted Heath.

Those who knew Powell best claimed that he was not a racialist. The local newspaper editor, Clem Jones, thought that Enoch’s anti-immigration stance was not ideologically-motivated, but had simply been influenced by the anger of white Wolverhampton people who felt they were being crowded out; even in Powell’s own street of good, solid, Victorian houses, next door went sort of coloured and then another and then another house, and he saw the value of his own house go down. But, Jones added, Powell always worked hard as an MP for all his constituents, mixing with and helping them regardless of colour. Unlike his Edwardian conservative contemporary, J R R Tolkein, for example, he had no visceral antipathy to coloured skins:

We quite often used to go out for a meal, as a family, to a couple of Indian restaurants, and he was on extremely amiable terms with everybody there, ‘cos having been in India and his wife brought up in India, they liked that kind of food.

On the numbers migrating to Britain, however, Powell’s predicted figures were not totally inaccurate. Just before his 1968 speech, he had suggested that by the end of the century, the number of black and Asian immigrants and their descendants would number between five and seven million, about a tenth of the population. According to the 2001 census, 4.7 million people identified as black or Asian, equivalent to 7.9 per cent of the total population. Immigrants were and still are, of course, far more strongly represented in percentage terms in the English cities. Powell may have helped British society by speaking out on an issue which, until then, had remained taboo. However, the language of his discourse still seems quite inflammatory and provocative, even fifty years later, so much so that even historians hesitate to quote them. His words also helped to make the extreme right Nazis of the National Front more acceptable. Furthermore, his core prediction of major civil unrest was not fulfilled, despite riots and street crime linked to disaffected youths from Caribbean immigrant communities in the 1980s. So, in the end, Enoch was not right, though he may have had a point.

By 1971, the South Asian and West Indian populations were equal in size and concentrated in the inner city wards and in north-west Birmingham, especially in Handsworth, Sandwell and Sparkbrook. Labour shortages had developed in Birmingham as a result of an overall movement towards more skilled and white-collar employment among the native population, which created vacancies in the poorly paid, less attractive, unskilled and semi-skilled jobs in manufacturing, particularly in metal foundries and factories, and in the transport and health care sectors of the public services. These jobs were filled by newcomers from the new Commonwealth. In the 1970s, poor pay and working conditions forced some of these workers to resort to strike action. Hostility to Commonwealth immigrants was pronounced in some sections of the local white population. One manifestation of this was the establishment of the Birmingham Immigration Control Association, founded in the early 1960s by a group of Tory MPs.

I remember discussing all these issues with my father, who was by no means a white supremacist, but who had fears about the ability of Birmingham and the Black Country, the area he had grown up in and where he had become a Jazz pianist and bandleader in the thirties before training for the Ministry, to integrate so many newcomers, even though they were fellow Christians. However, rather than closing down discussion on the issue, as so many did in the churches at that time, mainly to avoid embarrassment, he sought to open it up among the generations in the congregation, asking me to do a ‘Q&A’ session in the Sunday evening service in 1975. There were some very direct questions and comments fired at me, but I found common ground in believing that, whether or not God had intended the races to develop separately, first slavery and then famine and poverty, resulting from human sinfulness, had caused migration, and it was wrong to blame the migrants for the processes they had undergone.

Moreover, in the case of the Windrush migrants (we simply referred to them as ‘West Indians’ then), they had been invited to come and take jobs that were vital to the welfare and prosperity of our shared community. In the mid-seventies to eighties, I became involved in the Anti-Nazi League in Birmingham. The Singing Stewarts continued to perform to black and white audiences and even performed on the same stage as Cliff Richard.

In 1977, the group were signed to Christian label Word Records, then in the process of dropping their Sacred Records name. Their Word label album ‘Here Is A Song’ was produced by Alan Nin and was another mix of old spirituals (“Every time I Feel The Spirit”), country gospel favourites (Albert Brumley’s “I’ll Fly Away”) and hymns (“Amazing Grace”). With accompaniment consisting of little more than a double bass and an acoustic guitar, it was, in truth, a long, long way from the funkier gospel sounds that acts like Andrae Crouch were beginning to pioneer. The Singing Stewarts soldiered on for a few more years but clearly their popularity, even with the middle-of-the-road white audience, gradually receded. In his book British Black Gospel, author Steve Alexander Smith paid tribute to The Singing Stewarts as one of the first black gospel groups to make an impact in Britain and the first gospel group to be recorded by a major record company. They clearly played their part in the UK gospel music’s continuing development.

As New Commonwealth immigrants began to become established in postwar Birmingham, community infrastructures, including places of worship, ethnic groceries, halal butchers and, most significantly, restaurants, began to develop. Birmingham in general became synonymous with the phenomenal rise of the ubiquitous curry house, and Sparkbrook in particular developed unrivalled Balti restaurants. These materially changed patterns of social life in the city among the native population. In addition to these obvious cultural contributions, the multilingual setting in which English exists today became more diverse in the sixties and seventies, especially due to immigration from the Indian subcontinent and the Caribbean. The largest of the community languages is Punjabi, with over half a million speakers, but there are also substantial communities of Gujarati speakers, as many as a third of a million, and up to a hundred thousand Bengali speakers.

By the end of the seventies, Caribbean and Rastafarian Reggae music, together with ‘dub poetry’ was beginning to have a broad impact on British pop culture. In Birmingham, a group of out-of-work young white men formed the band UB40, named after their benefit claim forms. The multicultural band Steel Pulse also became popular. On the other side of rock ‘politics’, there was an eruption of racist, skinhead rock, and a ‘casual’ but influential interest in the far right from among more established artists. At a concert I attended at the Birmingham Odeon in 1976, Eric Clapton, arriving on stage an hour late, either drunk or ‘stoned’ (or both), enquired as to whether there were any immigrants in the audience. He then said, to the shock and disgust of almost everyone there, that Powell is the only bloke who’s telling the truth, for the good of the country. In his recent autobiography, Clapton apologised for this comment, but it had been made at a time of Rock Against Racism, and many of us had been trying to drive the National Front out of Birmingham through nonviolent marches. Forming a broad alliance in the Anti-Nazi League, we eventually succeeded.

In the mid-1980s, while working for the Quakers in the West Midlands, I ‘facilitated’ a joint Christian Education Movement schools’ publication involving teachers from the West Midlands and Northern Ireland. Conflict and Reconciliation (1990) was partly based on examples of community cohesion in Handsworth. The ‘riots’ there in the early 1980s, partly stage-managed by the national tabloid press, had threatened to unpick all the work done by the ‘Windrush generation’. David Forbes, a black community worker living in Handsworth at that time and when interviewed by me, visited ‘white flight’ schools in south Birmingham and Walsall with me to talk about his work and that of others in Handsworth, contrasted with the negative stereotyping which his neighbourhood had received.

Frank Stewart (one of the founding Singing Stewart brothers, pictured above) was also one of the first black people to play gospel music on a BBC radio station. Although in his later years it was Frank’s radio work, where for more than a decade, he presented The Frank Stewart Gospel Hour, for which he was best known, it was the many years he spent running The Singing Stewarts which was arguably his most significant contribution to UK Christian music history, black British music and community relations in the West Midlands.

Benjamin Zephaniah, Citizen of Handsworth – a biopic:

A more recent and better-known citizen of Handsworth, born there in 1958 and ‘raised’ there, was Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah was a British writer, dub poet, actor, musician and latterly professor of poetry and creative writing, pictured below. Our paths crossed very briefly when he gave a poetry workshop to students at the Quaker School where I was teaching from 1998 to 2004.

He referred to Handsworth as the “Jamaican capital of Europe”. The son of parents who had migrated from the Caribbean – Oswald Springer, a Barbadian postman, and Leneve (née Honeyghan), a Jamaican nurse who came to Britain in 1956 and worked for the National Health Service – he had a total of seven younger siblings, including his twin sister, Velda. Zephaniah later wrote that he was strongly influenced by the music and poetry of Jamaica and what he called “street politics”, and he said in a 2005 interview:

Well, for most of the early part of my life I thought poetry was an oral thing. We used to listen to tapes from Jamaica of Louise Bennett, who we think of as the queen of all dub poets. For me, it was two things: it was words wanting to say something and words creating rhythm. Written poetry was a very strange thing that white people did.

His first performance was in church when he was eleven years old, resulting in him adopting the name Zephaniah (after the biblical prophet), and by the age of fifteen, his poetry was already known among Handsworth’s Afro-Caribbean and Asian communities. He was educated at Broadway School, Birmingham, from which he was expelled aged 13, unable to read or write due to dyslexia. He was sent to Boreatton Park approved school in Baschurch, Shropshire. Zephaniah’s family was Christian, but he became a Rastafarian at a young age.

The gift, during his childhood, of an old, manual typewriter inspired him to become a writer. It is now in the collection of Birmingham Museums Trust. As a youth, he spent time in borstal and in his late teens, received a criminal record and served a prison sentence for burglary. Tired of the limitations of being a black poet communicating with black people only, he decided to expand his audience, and in 1979, at the age of 22, he headed to London, where his first book would be published the next year. While living in London, Zephaniah was assaulted during the 1981 Brixton riots and chronicled his experiences on his 1982 album Rasta. He experienced racism on a regular basis:

They happened around me. Back then, racism was very in your face. There was the National Front against black and foreign people, and the police were also very racist. I got stopped four times after I bought a BMW when I became successful with poetry. I kept getting stopped by the police, so I sold it.

In a session with John Peel on 1 February 1983 – one of two Peel sessions he recorded that year – Zephaniah’s responses were recorded in such poems as “Dis Policeman”, “The Boat”, “Riot in Progress” and “Uprising Downtown”. In 1982, Zephaniah released the album Rasta, which featured the Wailers’ first recording since the death of Bob Marley as well as a tribute to the then political prisoner (later to become South African president) Nelson Mandela. The album gained Zephaniah international prestige and topped the Yugoslavian pop charts. It was because of this recording that he was introduced to Mandela, and in 1996, Mandela requested that Zephaniah host the president’s Two Nations Concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London.

But he never forgot his Handsworth roots, and returned to Birmingham frequently, where The Birmingham Mail dubbed him “The people’s laureate”. His cousin, Michael Powell, died in police custody, at Thornhill Road police station in Birmingham, in September 2003, and Zephaniah regularly raised the matter, continuously campaigning with his brother Tippa Naphtali, who set up a national memorial fund in Powell’s name to help families affected by deaths in similar circumstances. In November 2003, Zephaniah was offered an appointment in the 2004 New Year Honours as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), for which he said he had been recommended by Tony Blair. But he publicly rejected the honour and, in a subsequent article for The Guardian, elaborated on learning about being considered for the award and his reasons for rejecting it: