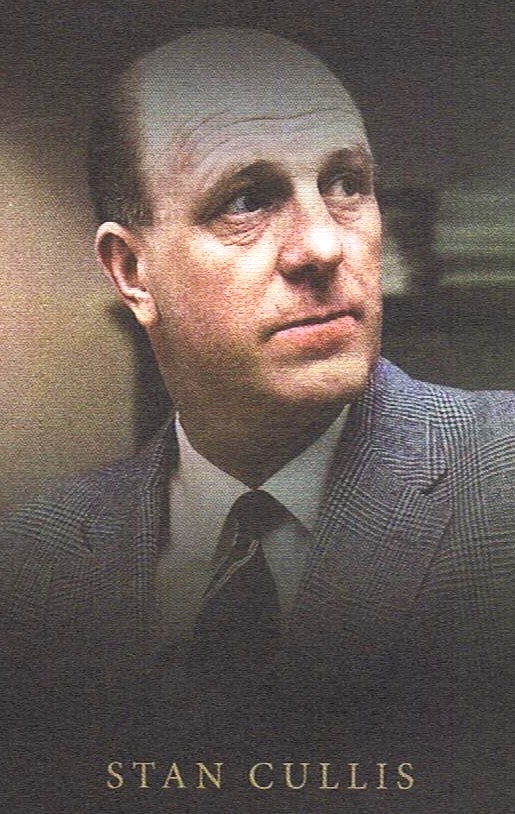

Part One: 1949-1964 – The Cullis Years

‘They Wore the Shirt’:

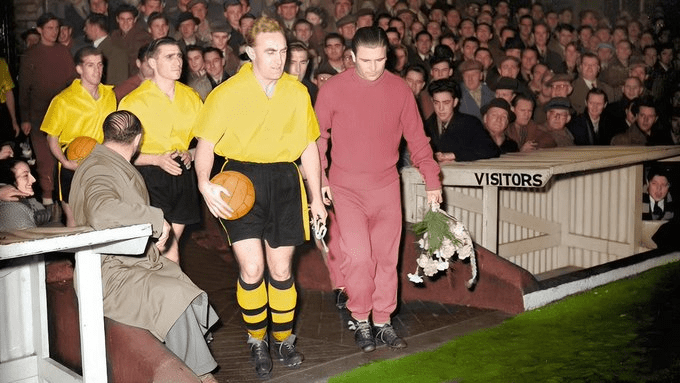

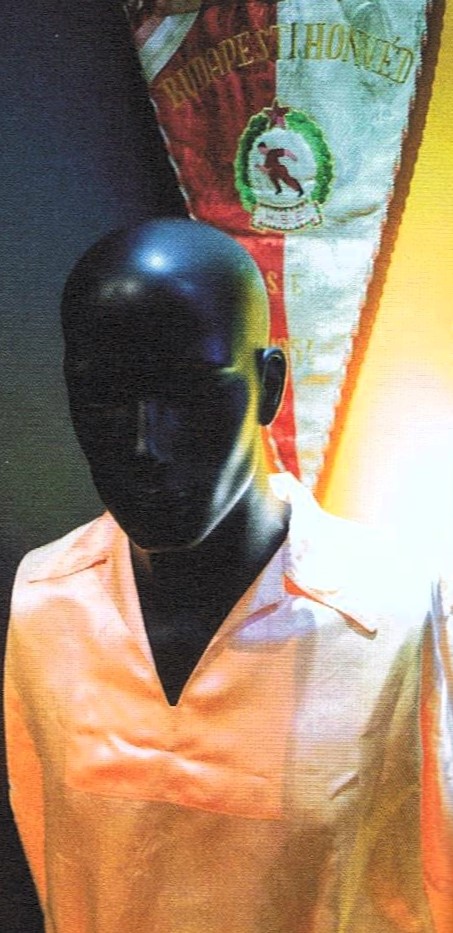

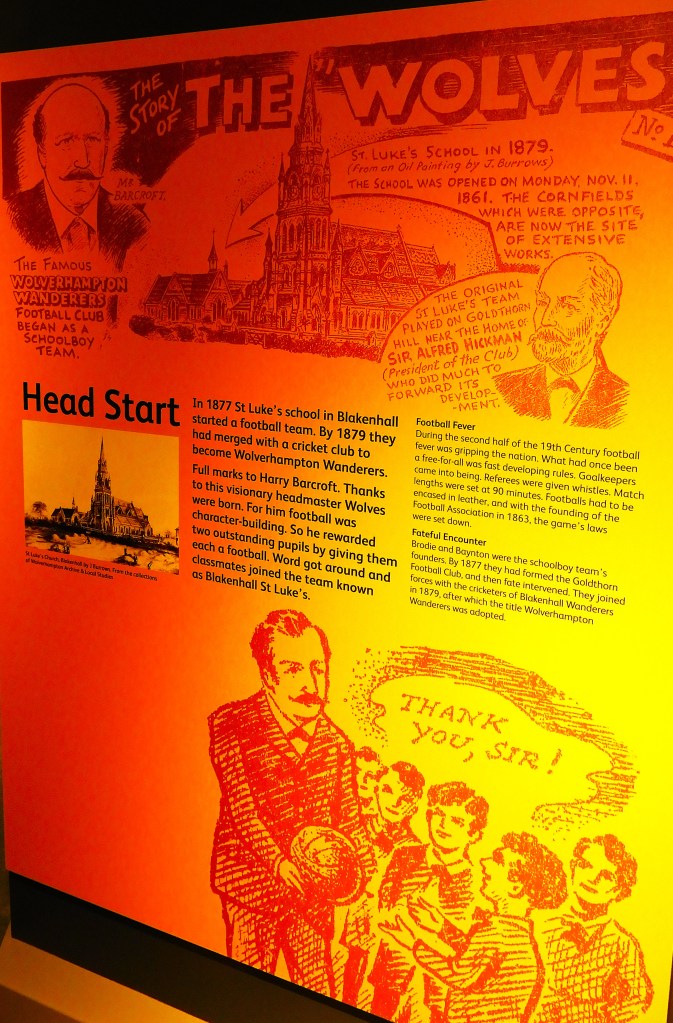

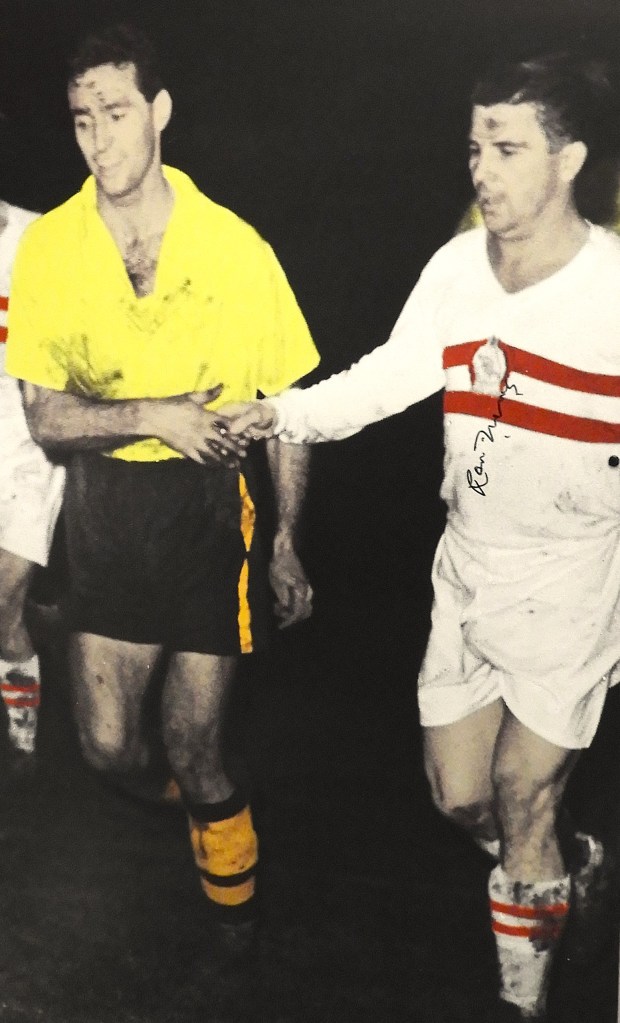

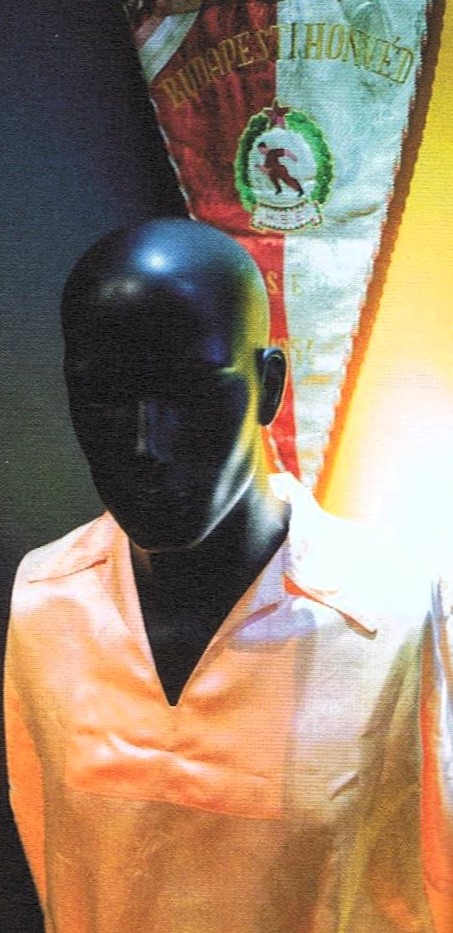

At the end of July 2024, my son and I, both fans of Wolverhampton Wanderers (the ‘Wolves’) visited their stadium, Molineux, and their new Museum chronicling the history of the club and the stadium dating back to 1877. The museum itself dates from the 2011-12 season when the Stan Cullis Stand, itself built where the ‘Cow Shed’ end once stood (where I used to stand as a boy) was replaced by a magnificent two-tier stand which also houses the club ‘megastore’ and the museum. One of the most iconic exhibits in the museum is the Rayon Silk shirt (now somewhat faded from its original fluorescent old gold, as seen in two of the photographs below), which the Wolves team wore on a few occasions, firstly in the second half of two league games in 1951.

The shirt in the Museum is thought to have been worn by Brian Punter at a Youth team game against Birmingham County FA as described in Steve Plant’s book, They Wore the Shirt. This occurred at Dudley’s Revo Electric Ground in 1953 when floodlit games began at Molineux. The shirt has no number on the back and is therefore believed to be a prototype. Revo Electric’s ground had floodlights before Molineux itself, and it’s thought that Stan Cullis, the Wolves manager, was in attendance and wanted to see what the shirt looked like under the lights as, of course, It was designed to reflect the floodlights. It’s also believed that Punter wore this shirt with the rest of the Wolves Youth side wearing the standard Wolves shirt of the time.

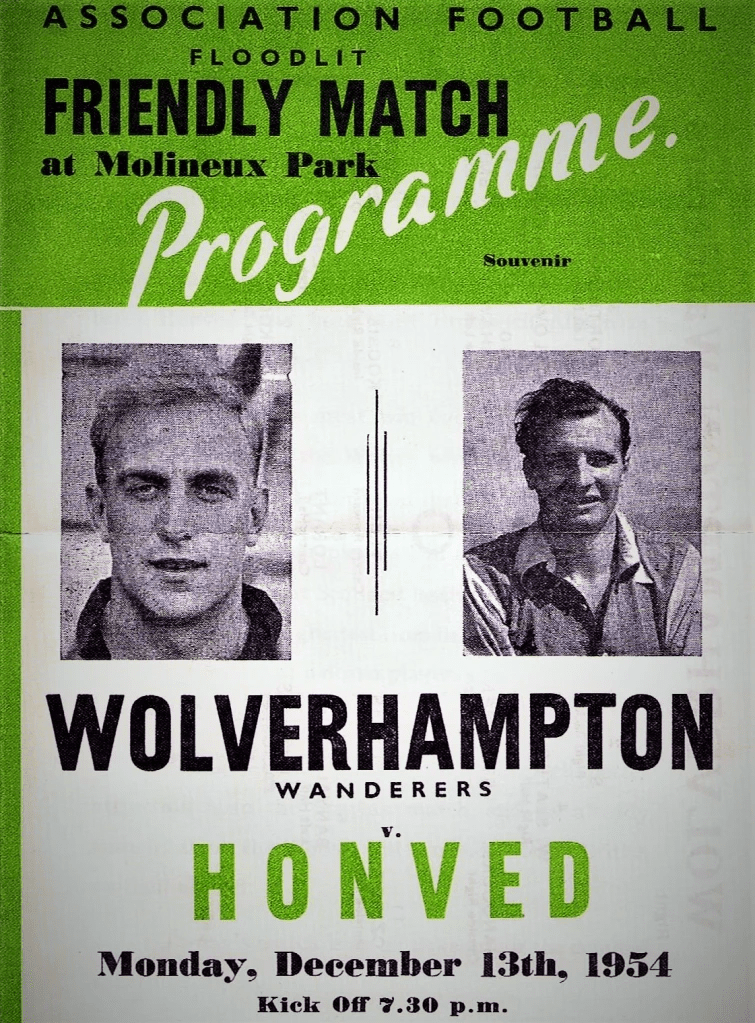

The floodlit friendly games were all ‘iconic’ but especially the match played on 13th December 1954 against Honved of Budapest, so the golden shirt of ‘poor man’s silk’ represents that famous occasion. It was discovered during a ‘Champions of the World’ project, funded by the national lottery to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of the iconic Wolves v Honved match. Peter Crump, whose brother found the shirt, writes:

“I love this shirt as it allows us to tell the amazing story of how Wolverhampton Wanderers and the great footballers of that period changed football forever. …

“The Wolves players of this period are not just Wolves Legends, they are footballing legends. Football under the lights gradually become a normal part of the calendar and (they) are still magical to this day.

“I am far too young to remember this era. This period is so special and this wonderful shirt allows us to make sure that we keep this alive. We have a duty to tell this story over and over again and make sure that Stan Cullis’ Gold and Black Army always lives on.”

Quoted in Wolves Museum Guide (2024), p. 48.

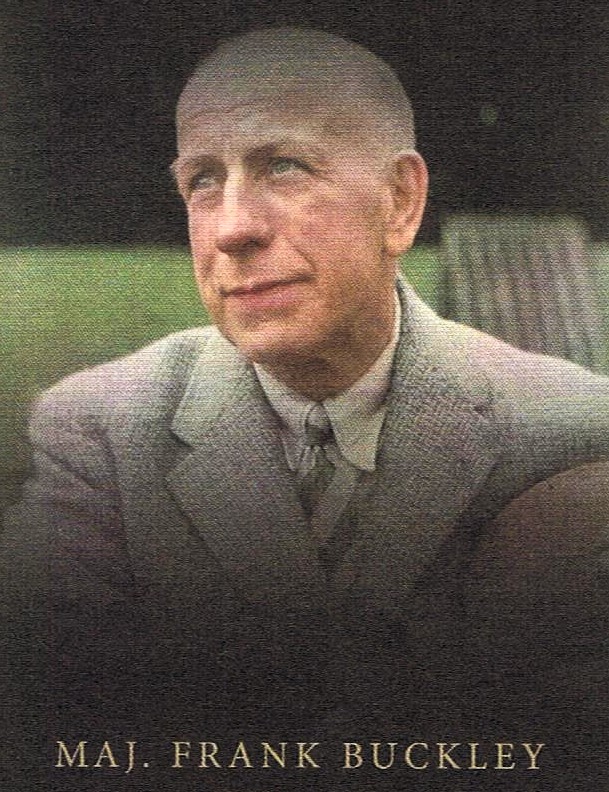

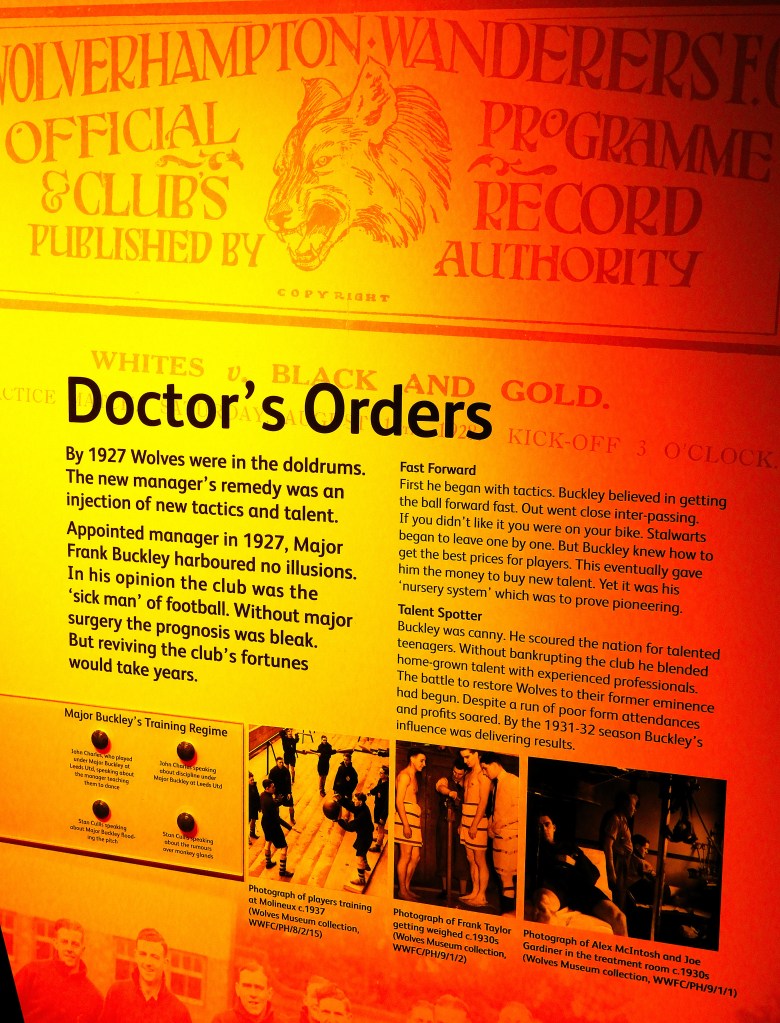

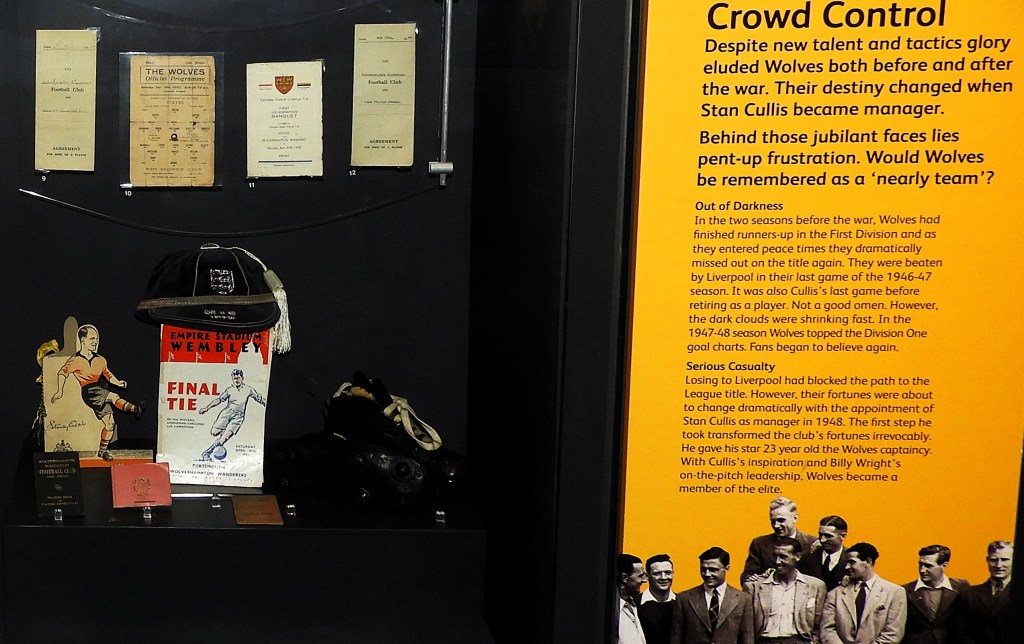

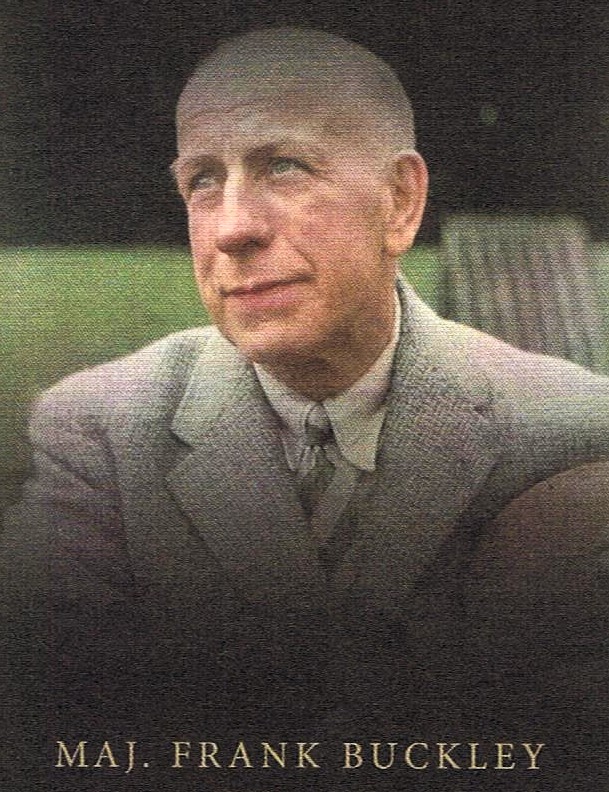

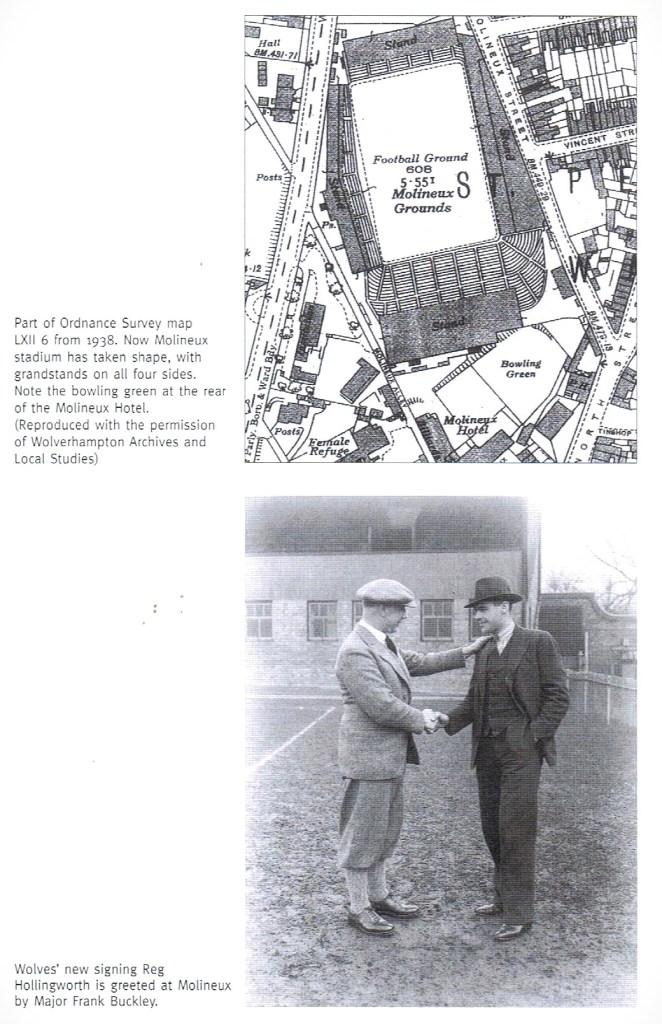

Prelude – The Buckley Era, 1927-47:

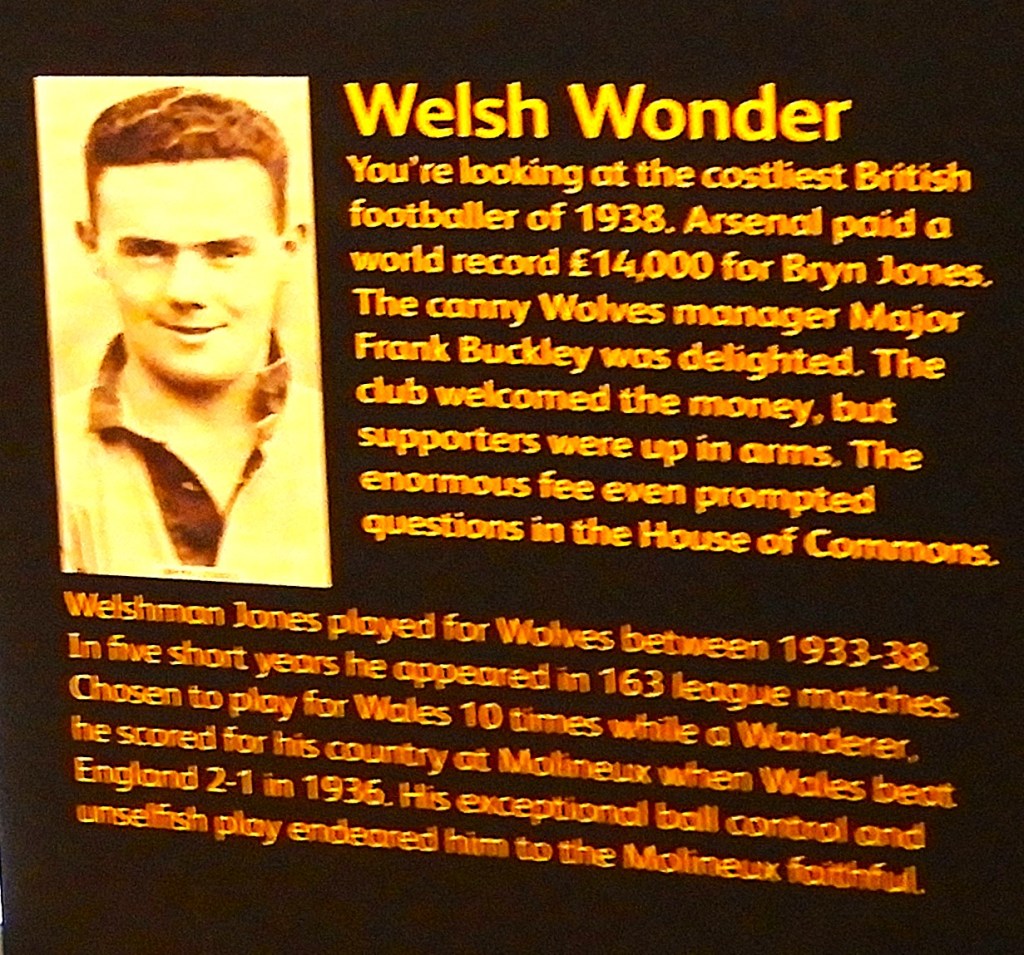

The story of Wolves’ Golden Era has its roots in Major Frank Buckley’s period as their manager beginning in 1927. During his time at Wolves, Major Buckley showed that he was not frightened of taking decisions that would make him an unpopular figure with supporters. One of these was the sale of Bryn Jones in 1938:

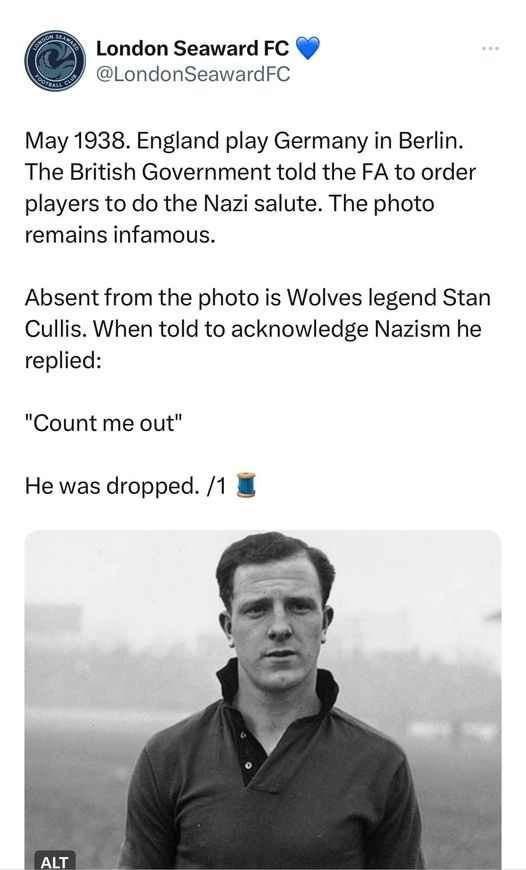

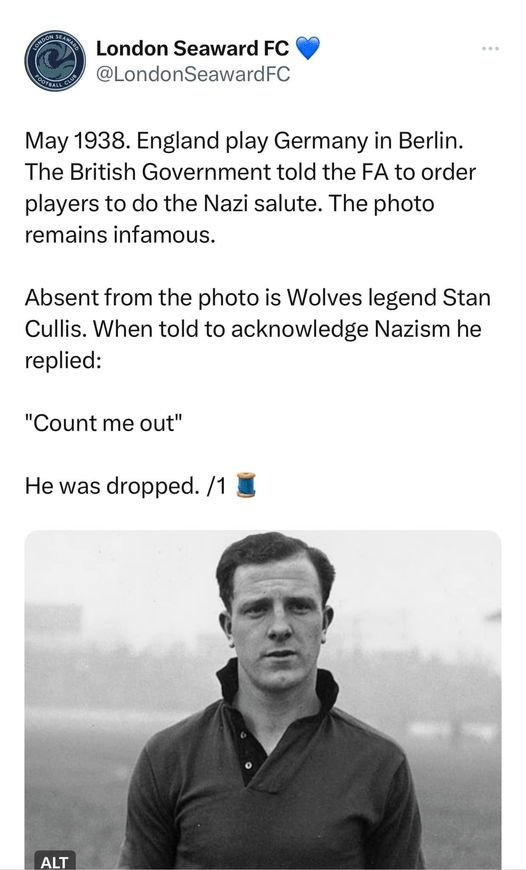

1938 is also notorious in the history of the England football team, as it is in British history, as the year in which the team played in Berlin and gave the Nazi salute in tribute to Adolf Hitler and the fascist régime triumphant in the country and other German-speaking areas of Europe at that time. This was at the peak of the British government’s appeasement policy towards the ascendancy of fascism throughout Europe, especially in Italy and Spain in addition to Germany. The team photo before the game, showing all the players making the salute, was widely published in the national and international press at the time:

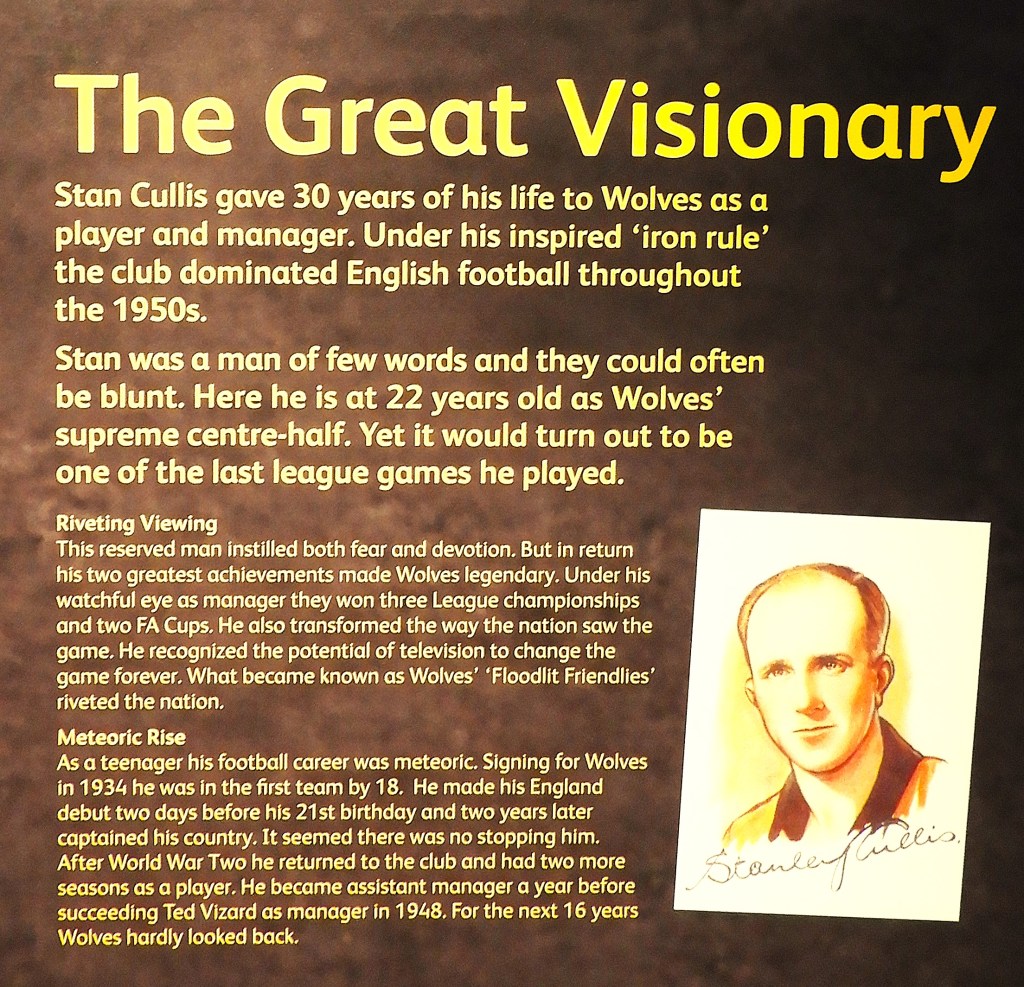

In 1934 Buckley signed a young Stan Cullis, who captained Wolves at 19 and England when two days short of his 23rd birthday. He won his first cap in the 5-1 win against Ireland in 1937, the first of twelve (Hitler’s European War prevented him from winning more). England won the match in Berlin 6-3, and despite his refusal to ‘obey orders’, he became one of only six Wolves players to have captained England. Buckley almost won Wolves’ first-ever First Division title for the 1937-38 season, but they were overtaken by Arsenal at the final hurdle.

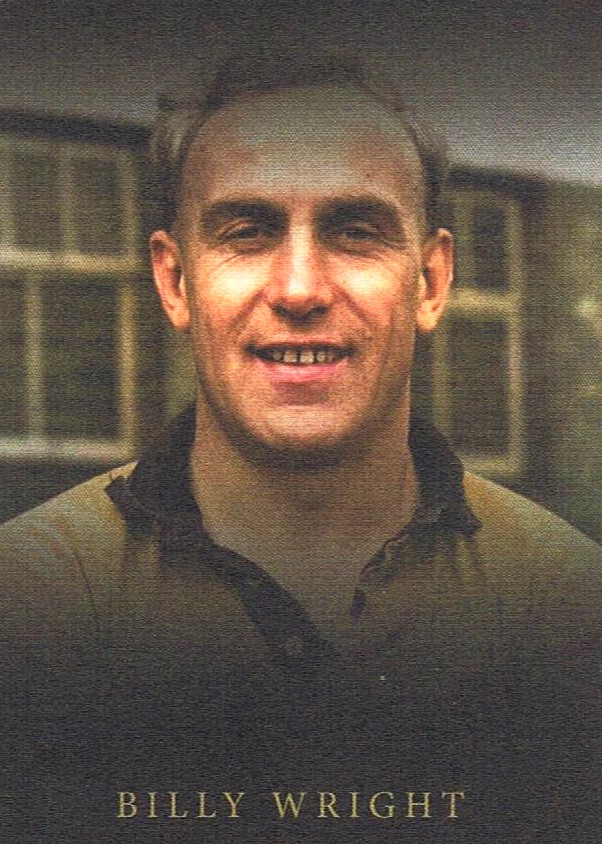

In 1938, William Ambrose Wright was invited for a trial. Buckley, a tough defender as a player, thought the youngster was too small and was about to release the player when his trainer, Jack Davies (pictured above), persuaded him to retain Wright.

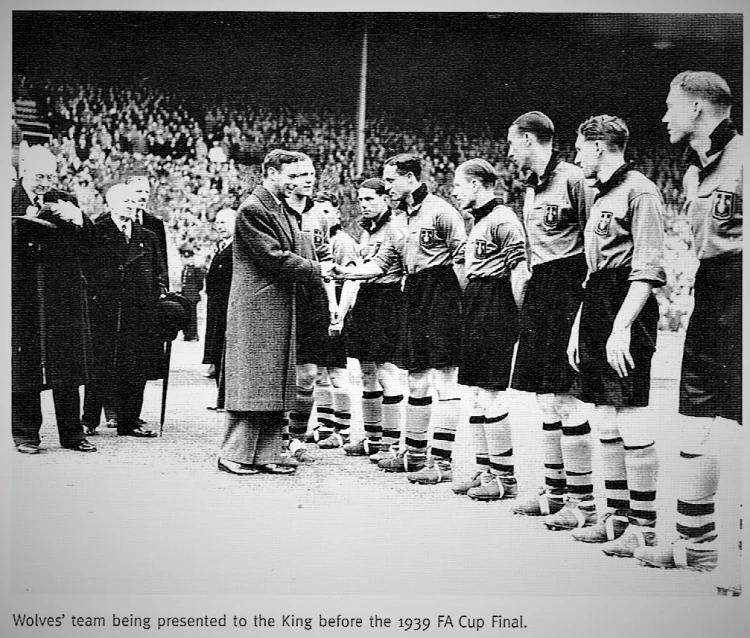

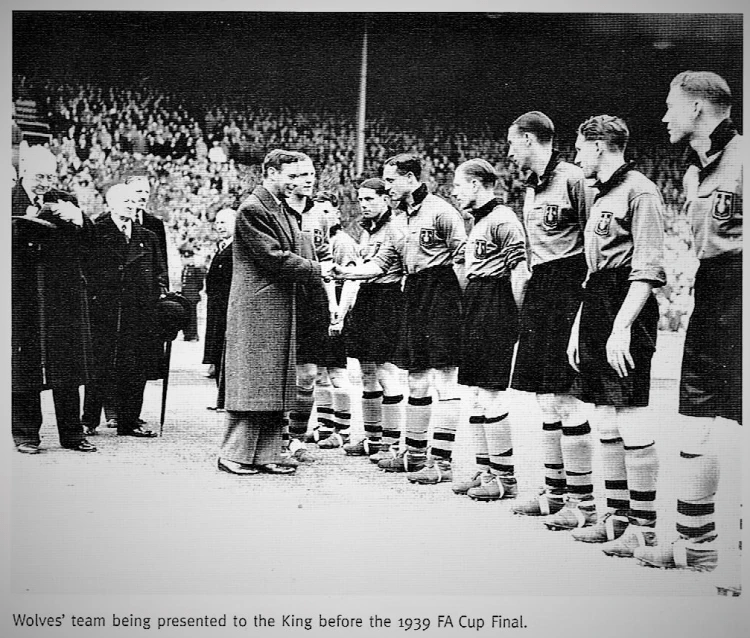

The following year, the team made their first visit to Wembley Stadium but lost unexpectedly to Portsmouth. They did, however, win the ‘wartime cup’ in 1942 under Buckley before his resignation in 1944. He was a strict military disciplinarian in training but transformed the team, paving the way to future post-war success.

The first competitive season after the war was the 1946-47 campaign, led by ex-Bolton Wanderers player, Ted Vizard as manager. Again, it ended in heartbreak when Wolves ‘simply’ needed to beat Liverpool in the season’s final game to win their first top-flight title. Unfortunately for the Wolves, Liverpool won 2-1 and took the title. The match was also the last for Stan Cullis as a player. He retired (aged 31) to become the club’s Assistant Manager in 1947, beginning the ‘Golden Era’ for the team. In the following season, the Wolves finished fifth and in 1948 Cullis became manager.

The Cullis Era Begins, 1948-53 – Cup-Winners & Champions:

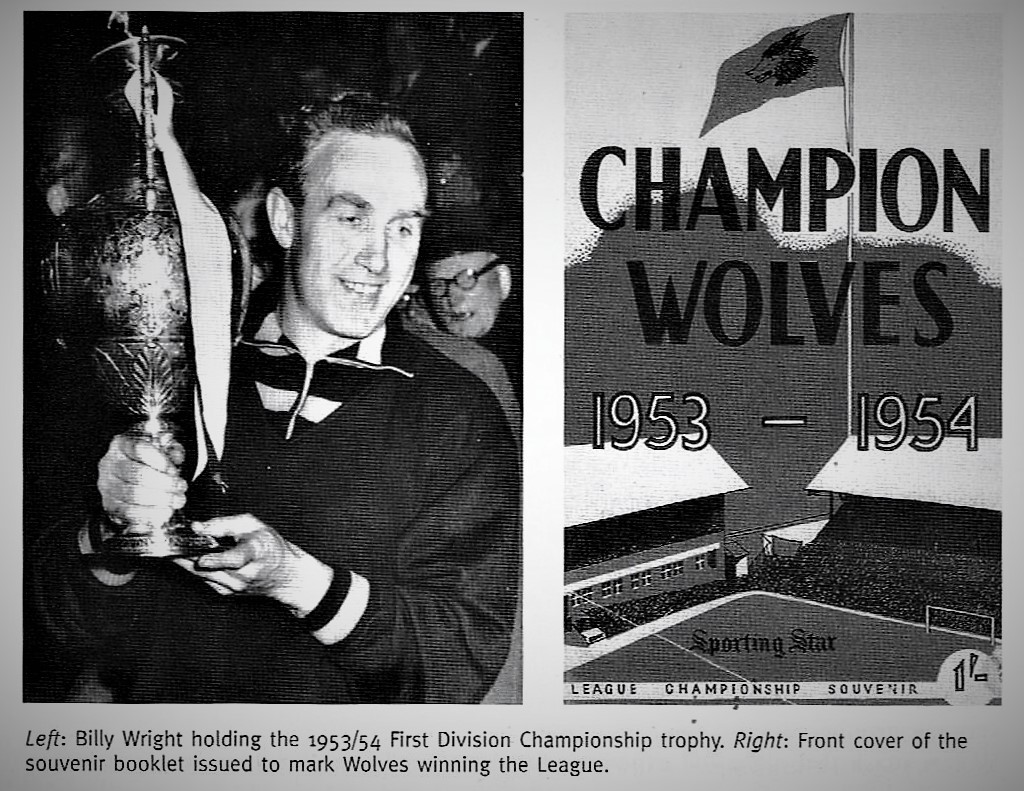

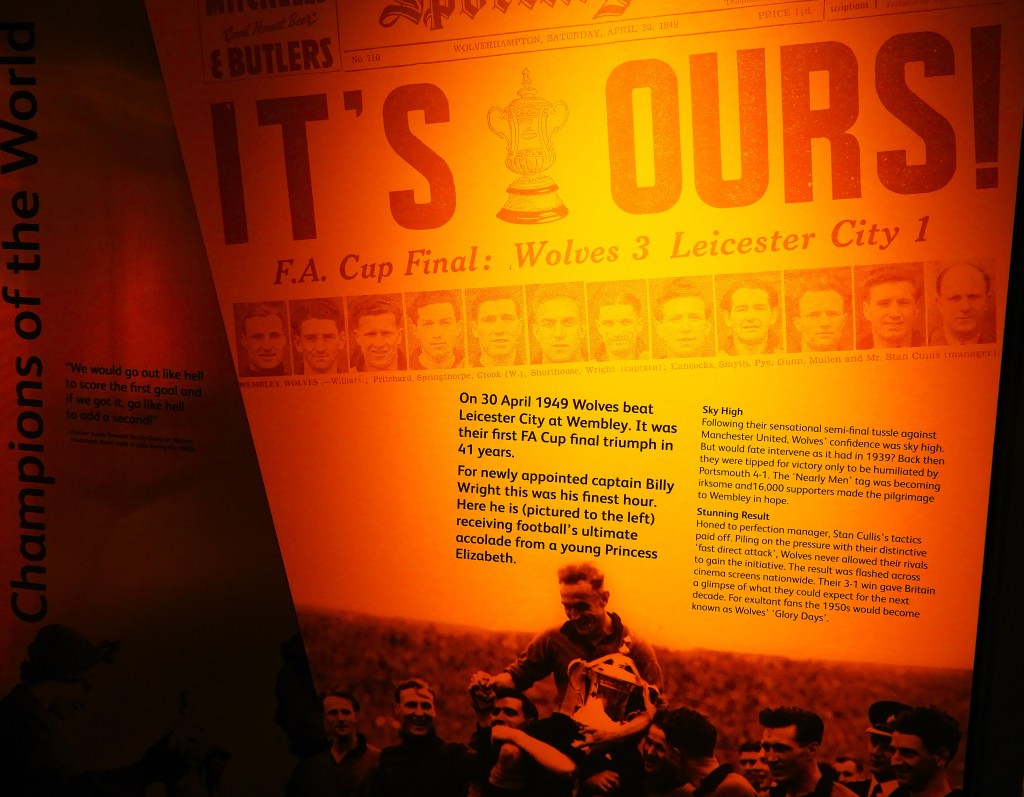

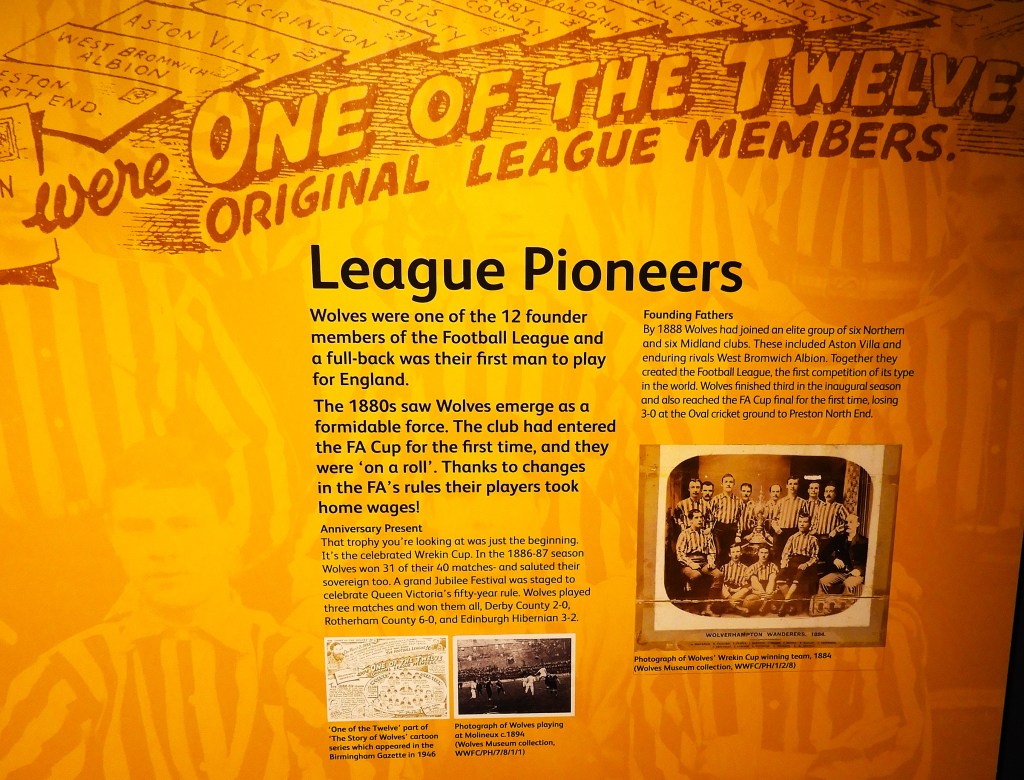

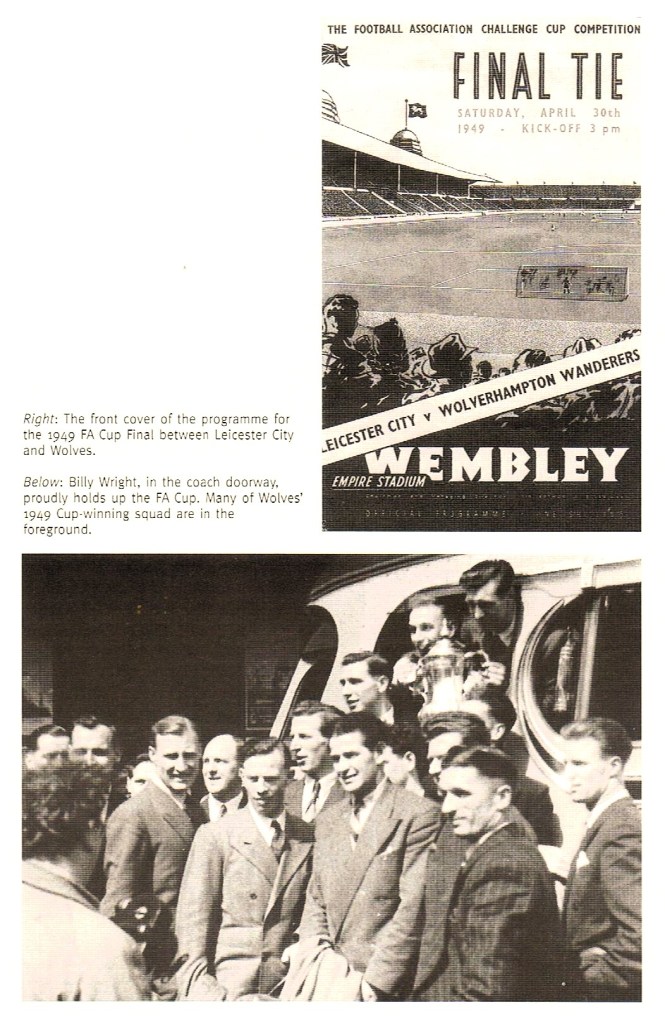

The following season, 1948-49, Cullis delivered Wolves’ first major trophy since 1908, when, a full decade after losing to Portsmouth, they finally won the FA Cup, beating Leicester City at Wembley. In the following two seasons, however, there was a significant slip in Wolves’ form. But Wolves were much improved in that season, as they returned to the top three. Over the previous ten seasons (excluding the war break), Wolves had finished second three times, third twice, fifth twice and sixth once. The 1952-53 season saw a revival in the club’s fortunes as they finished third in the League, and they continued to secure their place among the top clubs in the country, though they had to wait until 1953-54 to become First Division Champions.

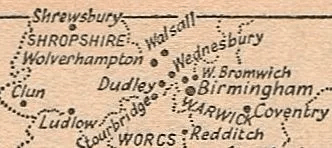

In the season following the late Queen’s Coronation, Wolves became Britain’s best and most celebrated football team. They won their inaugural First Division title, finishing four points ahead of local Black Country rivals West Bromwich Albion. They completed the double over West Brom, which proved vital at the end of the season as only two points were awarded for a win at that time. In the following nine seasons, Wolves finished outside the top three only once.

The Floodlit Friendly Fifties – ‘Champions of the World’, 1953-58:

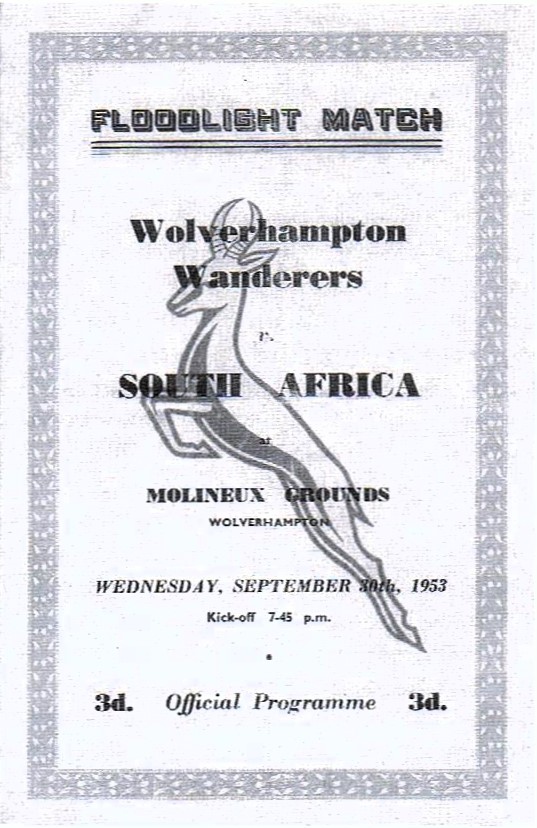

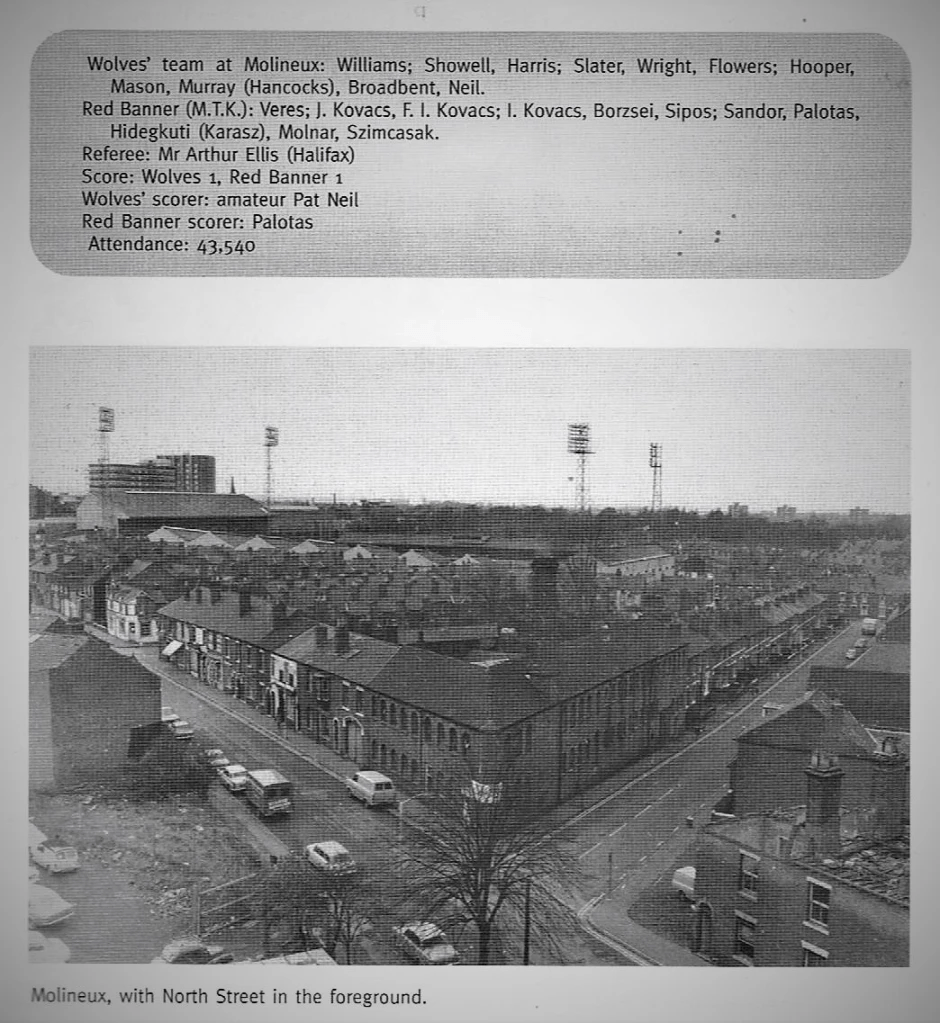

Towards the end of this initial successful period, the forward-looking board took the monumental decision to be among the first football league clubs to install floodlights, thus heralding a series of memorable night games. The Wolves programme had proudly proclaimed that the Molineux Grounds boasted covered accommodation for thirty thousand plus uncovered space for more than an additional thirty thousand. A system of floodlights would be a great addition to the stadium; however, both the Football League and the FA pronounced that floodlights would not be allowed for League and Cup games, though they could be used for friendly and charity games. In 1953 the construction of the floodlights proceeded apace and the lights were ready for the new season. But they were not allowed to be used for League and Cup games until February 1956. As a result, Wolves had to be innovative, and they invited a series of opponents to Molineux. From September 1953 to December 1962 Wolves played twenty-three iconic games under the lights. These were a mixture of friendlies, Charity Shield, European Cup and Cup Winners’ Cup games. Besides being English League Champions, they had also beaten Glasgow Celtic 2-0 in the second floodlit friendly match at Molineux in October 1953.

The first floodlit match took place a fortnight earlier, on 30 September, against the touring South African team, a game originally scheduled for the afternoon of that day. The honour of playing the very first floodlit game had originally been promised to Celtic, but the system, designed by W. G. France’s Electric Ltd. of Darlaston on the dining table of the Managing Director’s Bilston home, using a scaled model, was ready for use in advance of the prestigious match against the South African tourists. The Wolves board were keen to make the inaugural floodlit match as grand an affair as possible and therefore had the idea to switch the match against South Africa from what might have been, given the inclement late summer weather, a dull Wednesday afternoon fixture, into something that would live in the memory of all who witnessed it.

Probably no more than five or six thousand would have been at the afternoon match, as most people would be working. The Celtic directors readily gave way when the situation was explained to them. The inaugural match under the brand new lights proved to be a ‘magical’ occasion, dubbed variously in the press as ‘Football in Wonderland’, ‘Football in Fairyland’, ‘Football in Technicolor’ and a ‘Footballing Spectacular’. It kicked off at 7.45 p.m. in front of 33,000 curious supporters, the biggest crowd to watch the tourists, despite the ‘dodgy’ weather. The gate was probably a little disappointing for the directors, however, considering how momentous the occasion was. Wolves ran out in their new luminous gold strip contrasting with the bright green shirts of the ‘Springboks’: They ran in 3-1 winners. There weren’t many Wolverhampton people who saw this first match that wouldn’t want to see the Celtic match.

Sure enough, Wolves’ first floodlit friendly against a club side at Molineux resulted in a 2-0 victory over Glasgow Celtic on 14 October 1953, but their first match under lights against continental opposition was against the crack Austrian team, First Vienna FC on 13 October 1954. Wolves had already travelled to Austria to play a friendly against them on a wet Sunday afternoon in August, beating them to win a gold-plated trophy. Returning to Wolverhampton, they then played the FA Charity Shield clash with West Bromwich Albion, their Cup-winning neighbours. The match played on 29 September 1954 was a floodlit epic 4-4 draw, watched by over forty thousand. Wolves raced into a 4-1 lead before being pegged back by the Albion with a future Wolves manager, Ronnie Allen snatching a hat-trick.

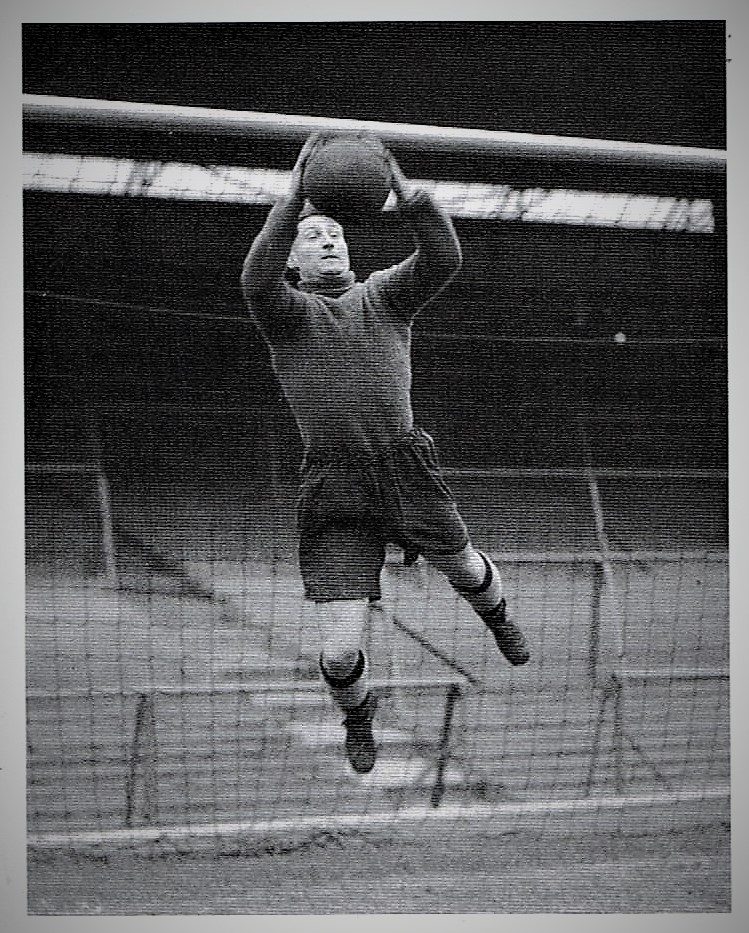

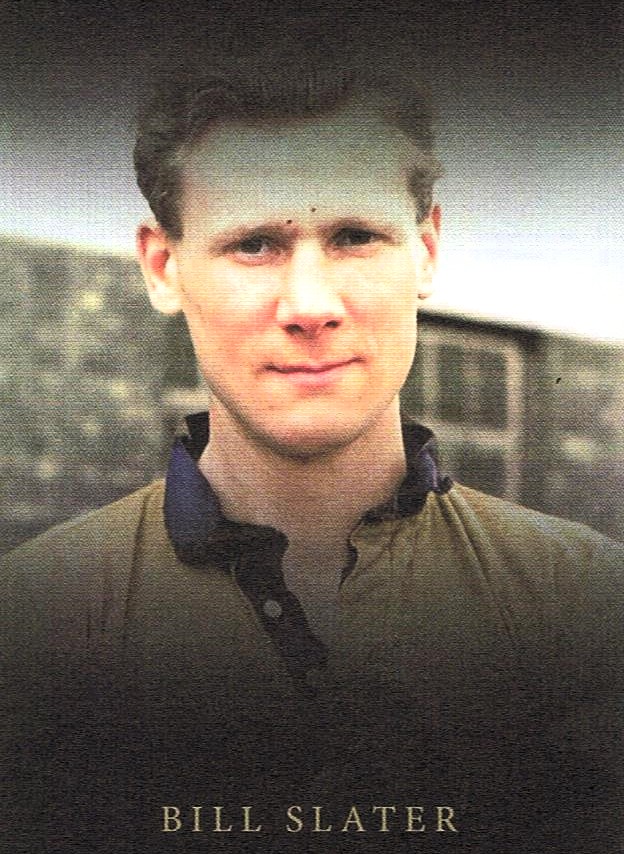

The return match with FC First Vienna was played on a Wednesday night at Molineux in mid-October and ended in a 0-0 draw. Wolves had to make several changes, the most noticeable of which was Bill Slater moving to centre forward. He failed to score, but on any other day, he might have scored a hat trick in what was an excellent performance. Vienna’s goalkeeper, Kurt Smied, gave a heroic display worthy of Bert Williams in keeping the hungry Wolves at bay.

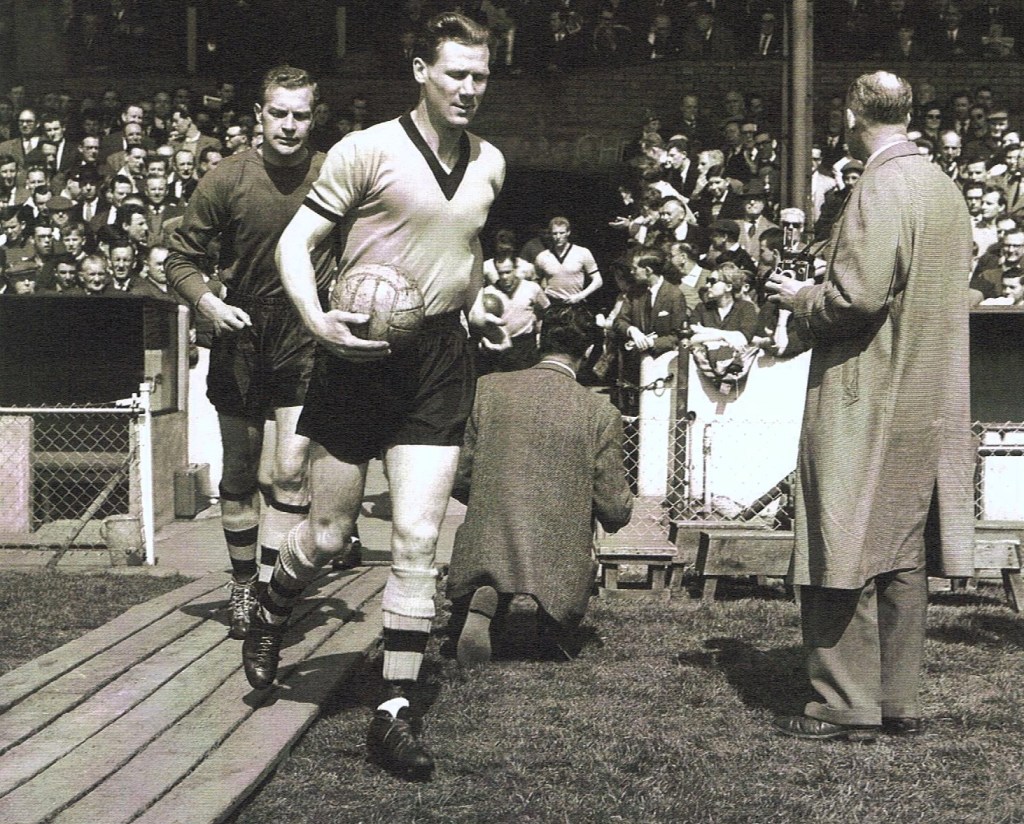

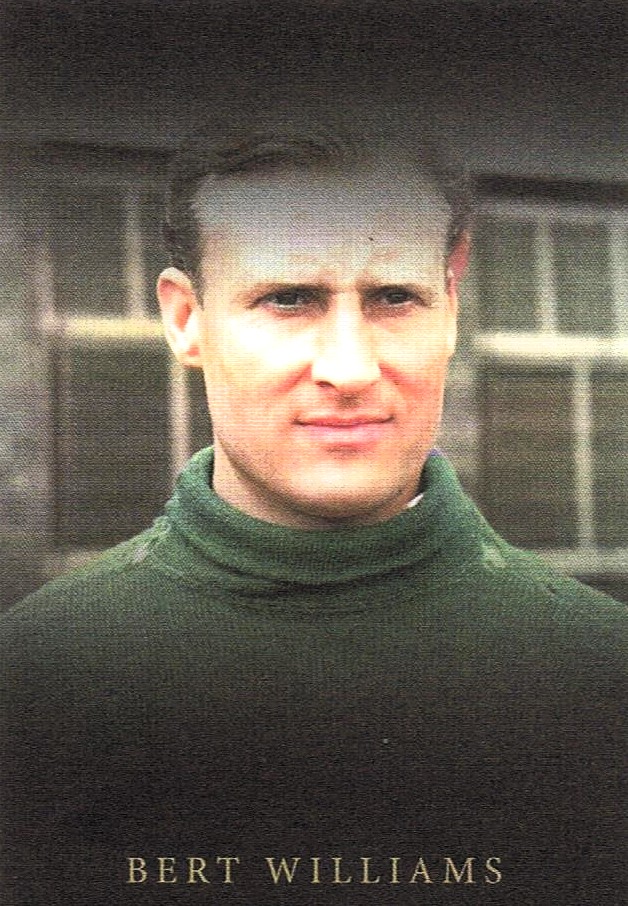

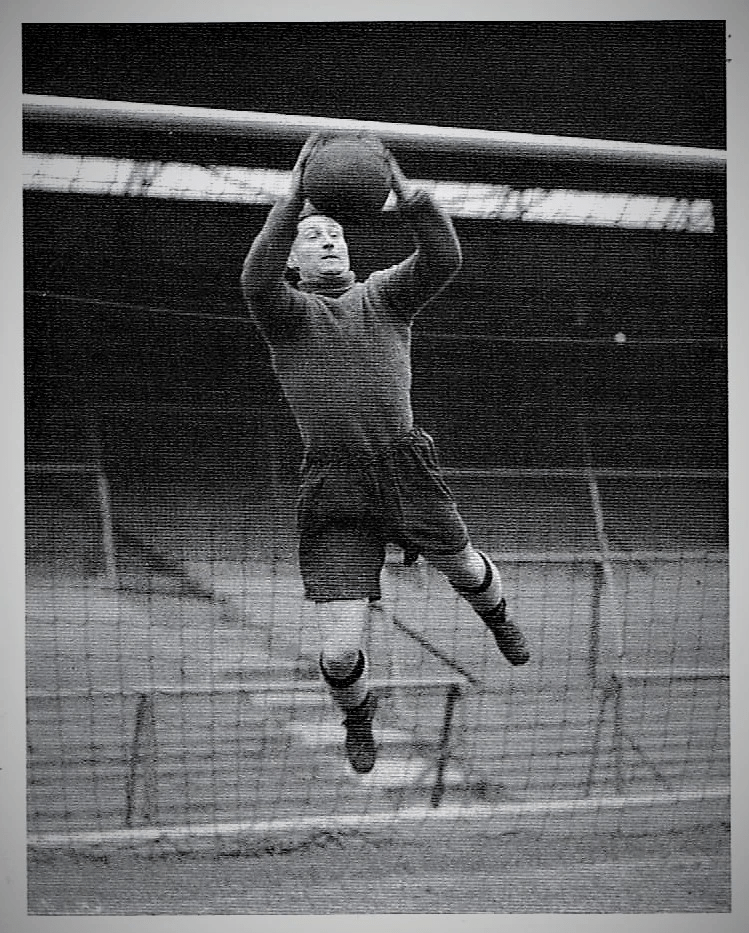

This was followed by a match against Spartak Moscow on a foggy Wolverhampton evening of 16 November and was broadcast live by the BBC. Spartak had recently crushed two of Belgium’s finest sides, Liége and Anderlecht, and a week earlier had beaten Arsenal 2-1 at Highbury, so Wolves knew that they were in for a tough night. The Wolves captain, Billy Wright led his side out clad in their new fluorescent rayon strip of gold shirts and black shorts. But the visitors began playing enthusiastically and panache, moving the ball around with great skill. Twice it had to be cleared from the goal line with Bert Williams beaten, but the Wolves goalkeeper (pictured above) saved several more good attempts on his goal.

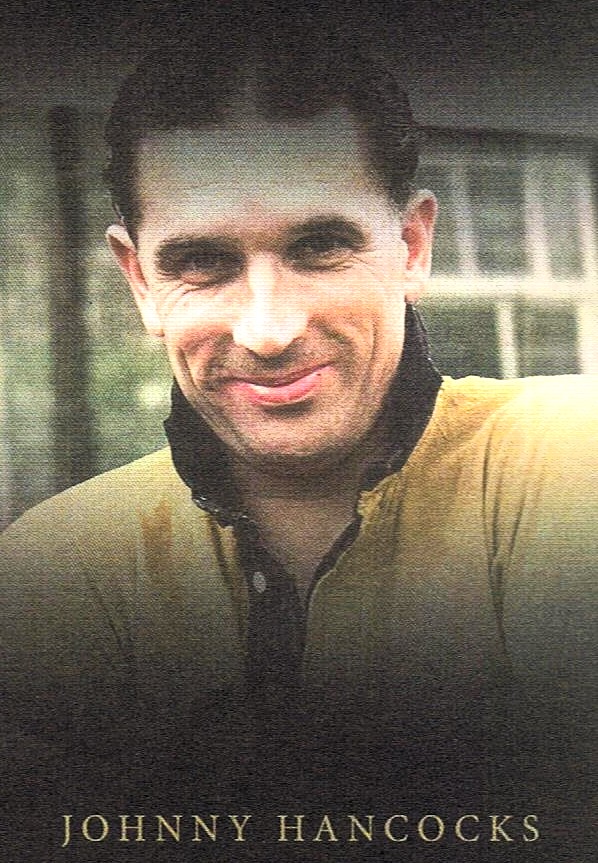

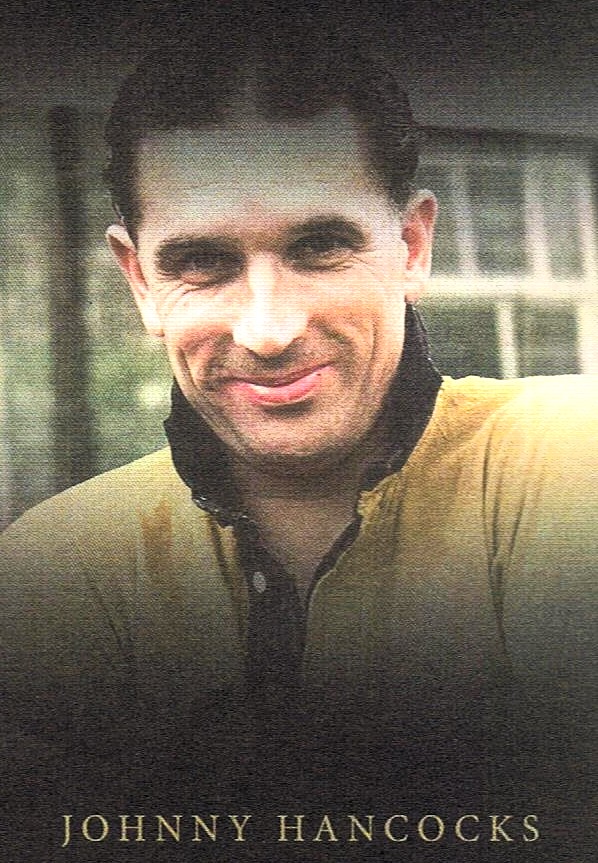

Wolves then began to counter with their own display of fierce but fair tackling that led to them moving the ball around with purpose, and they finally went ahead in the sixty-second minute through their outstanding centre-forward, Dennis Wilshaw. Then, seven minutes from time, with the Russians noticeably tiring, Johnny Hancocks got a second. It began to look good for the home team, and the Wolves’ superior stamina now began to tell. In the eighty-eighth minute, Roy Swinbourne added a third, followed a minute later by Hancocks making it four. Wolves had scored three in a little over five minutes against one of the tightest defences in Europe. The 4-0 scoreline may have looked a little flattering, but it might not have looked so emphatic had Bill Shorthouse and Billy Wright not broken up a series of threatening Russian attacks earlier in the game.

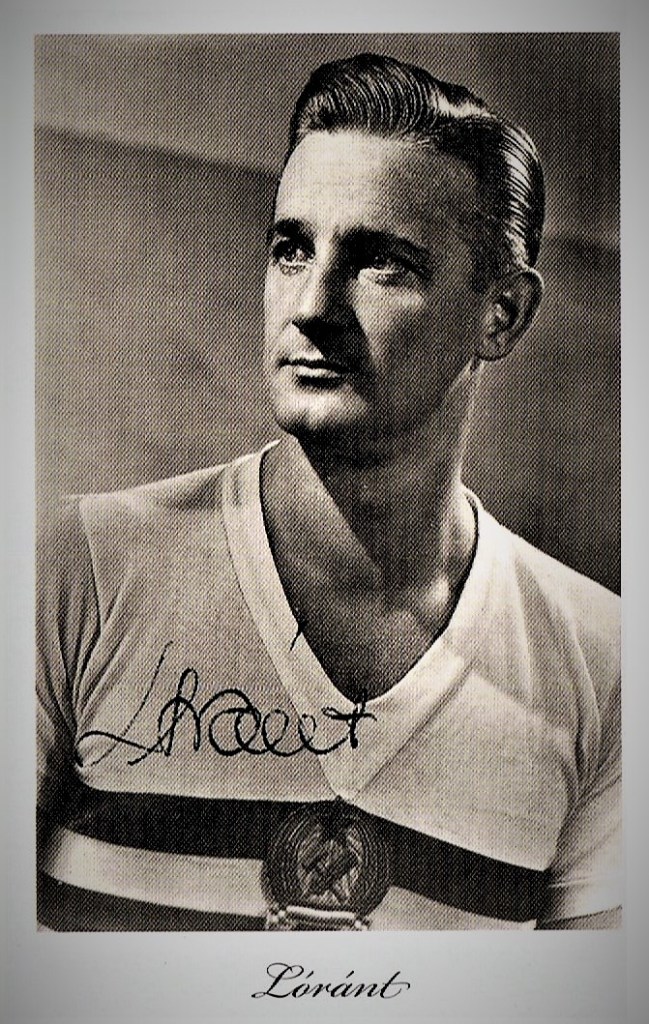

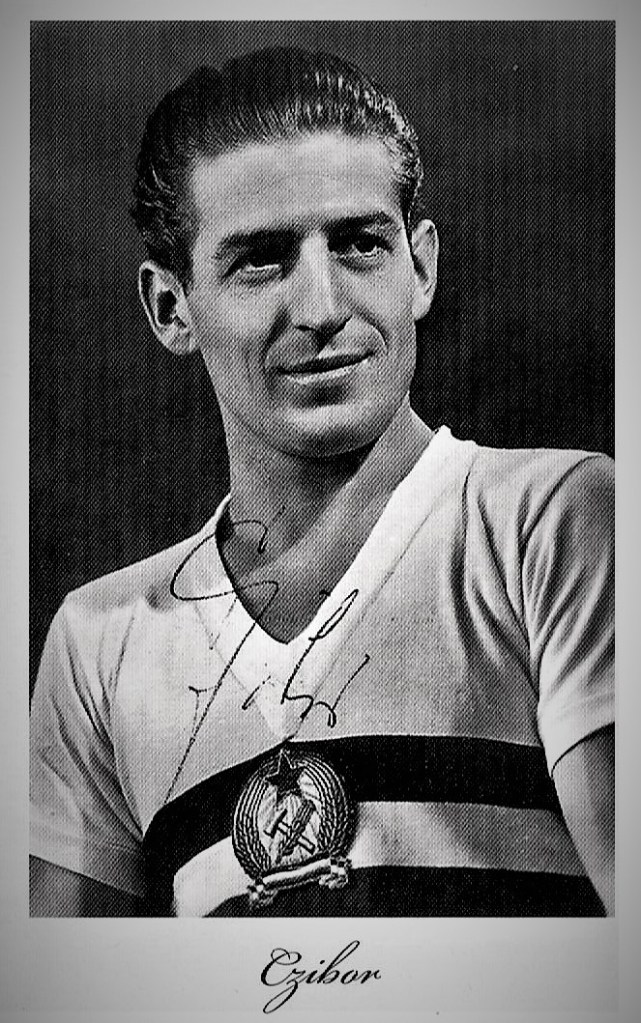

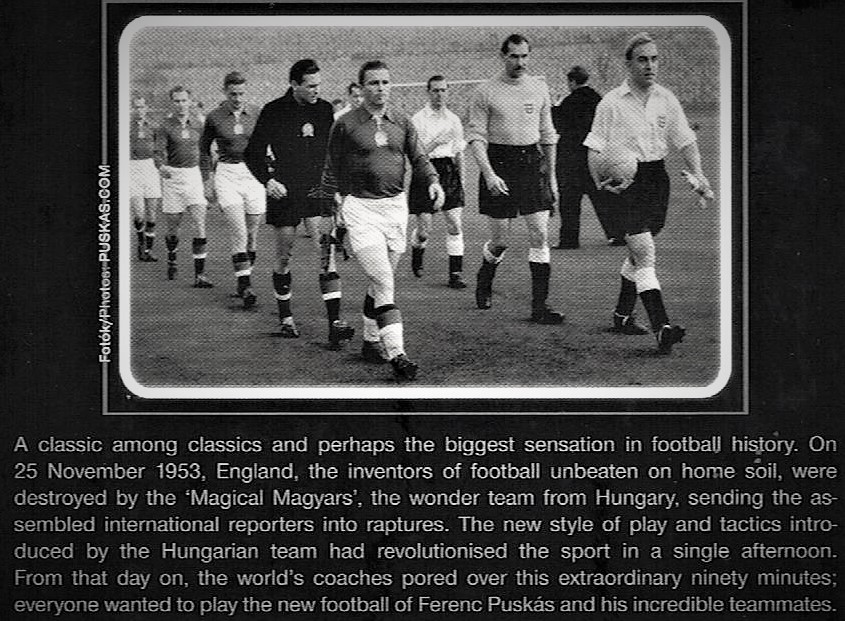

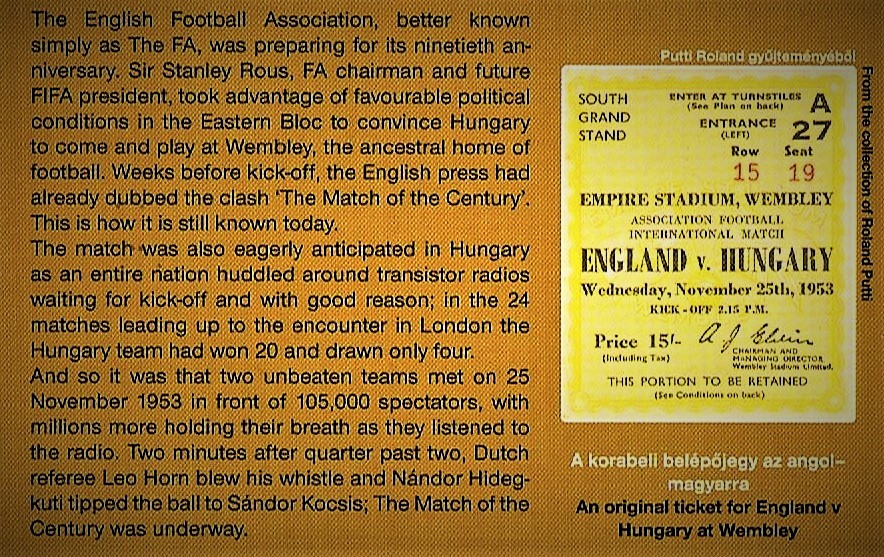

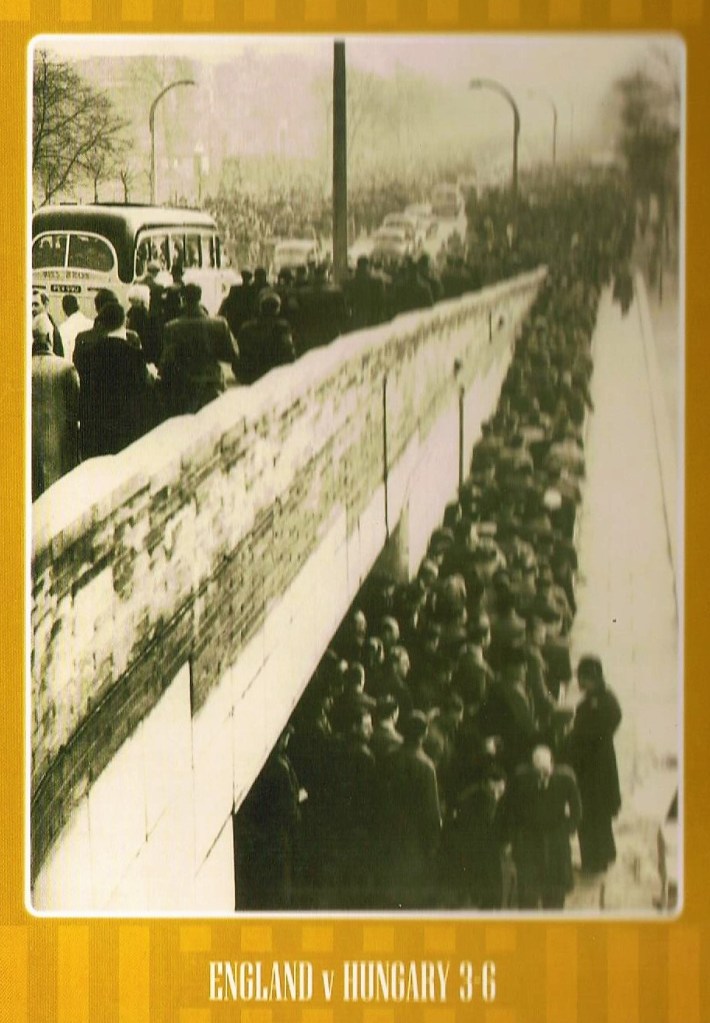

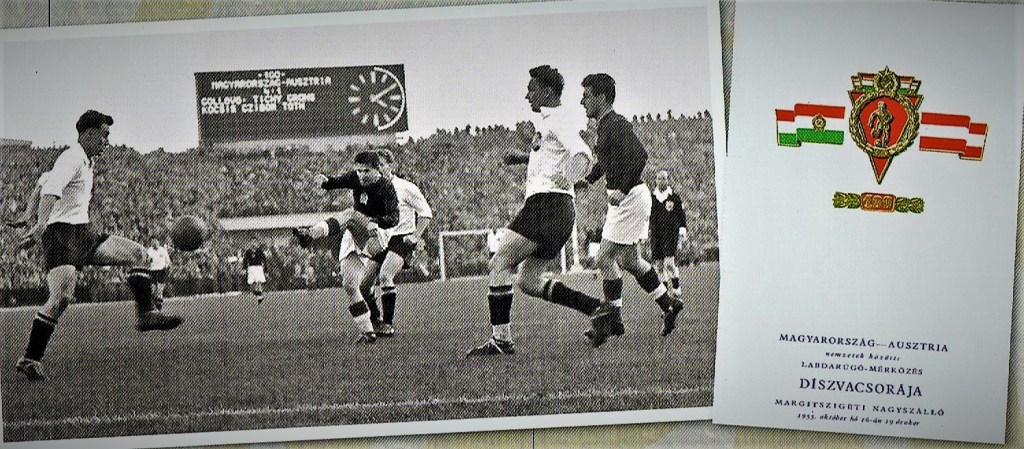

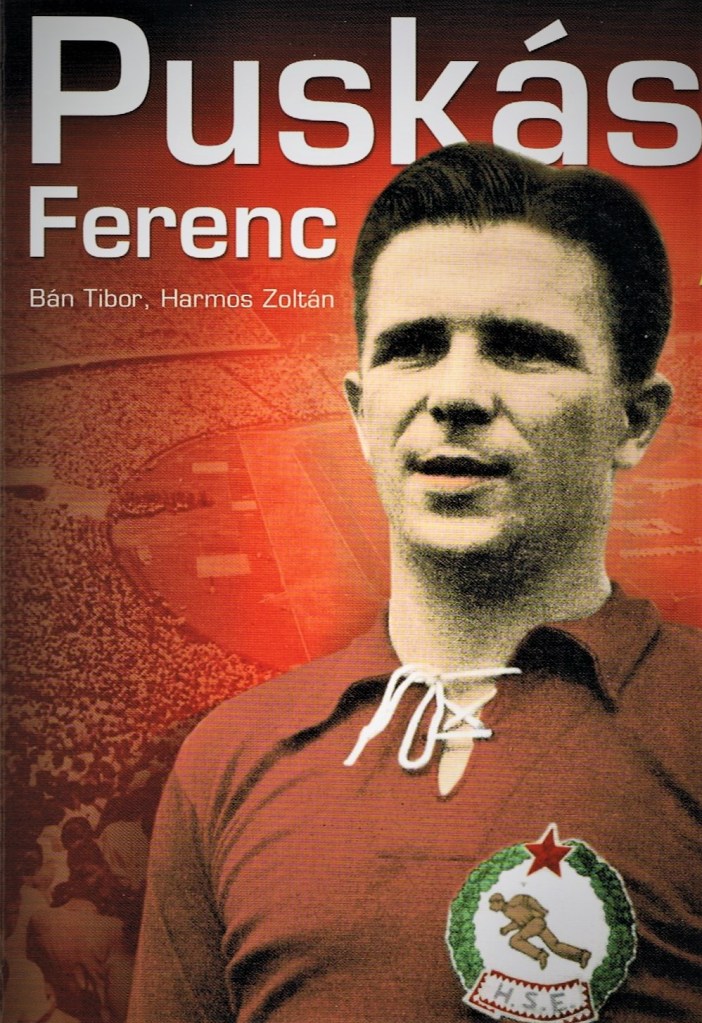

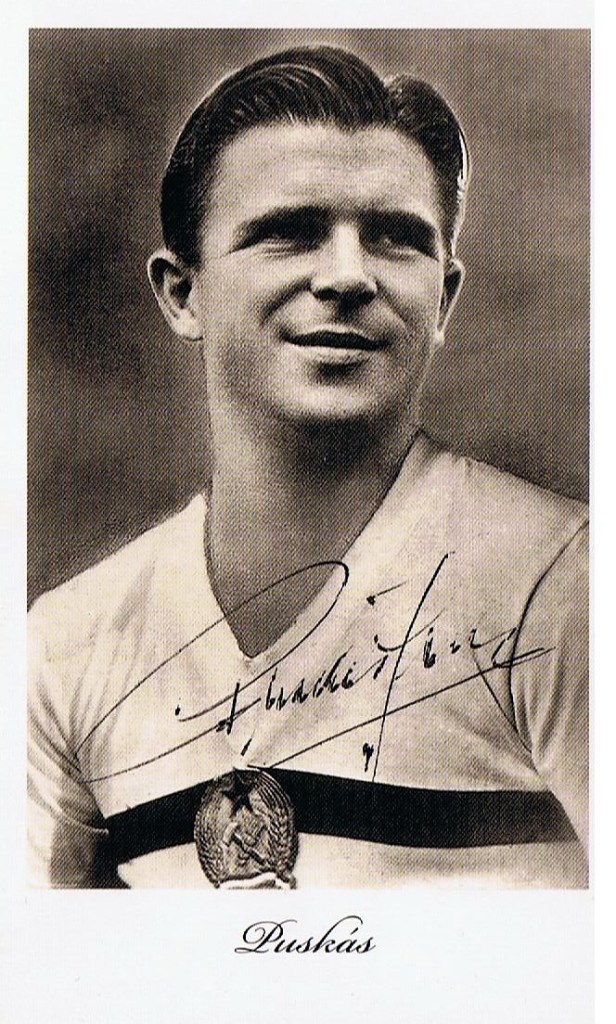

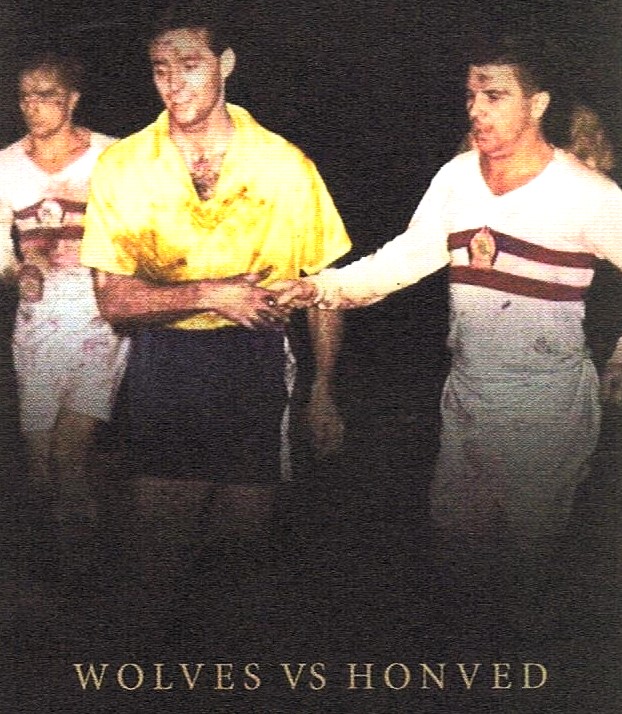

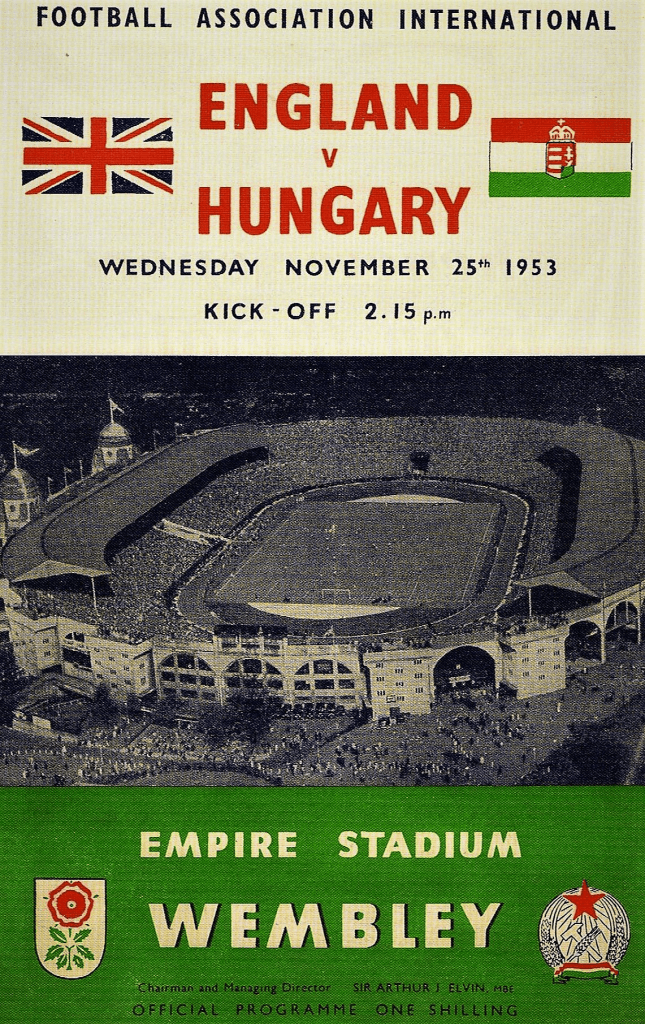

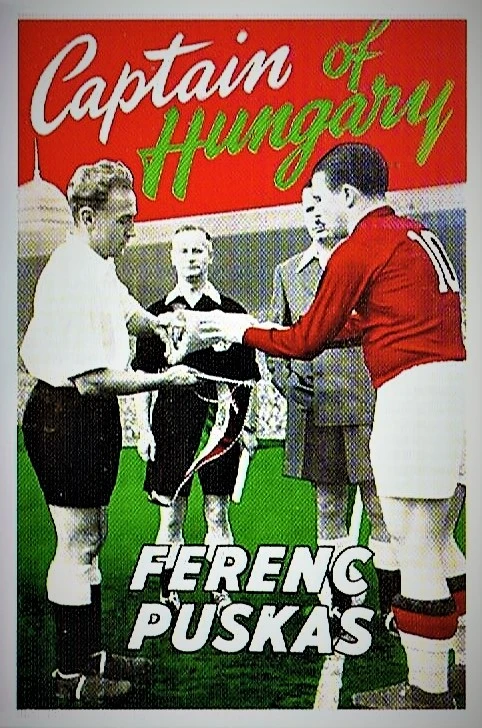

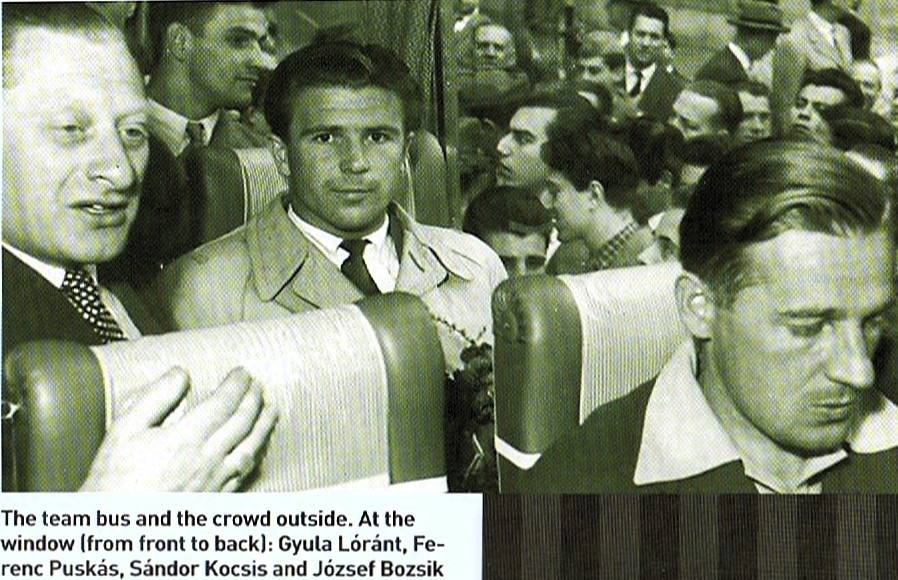

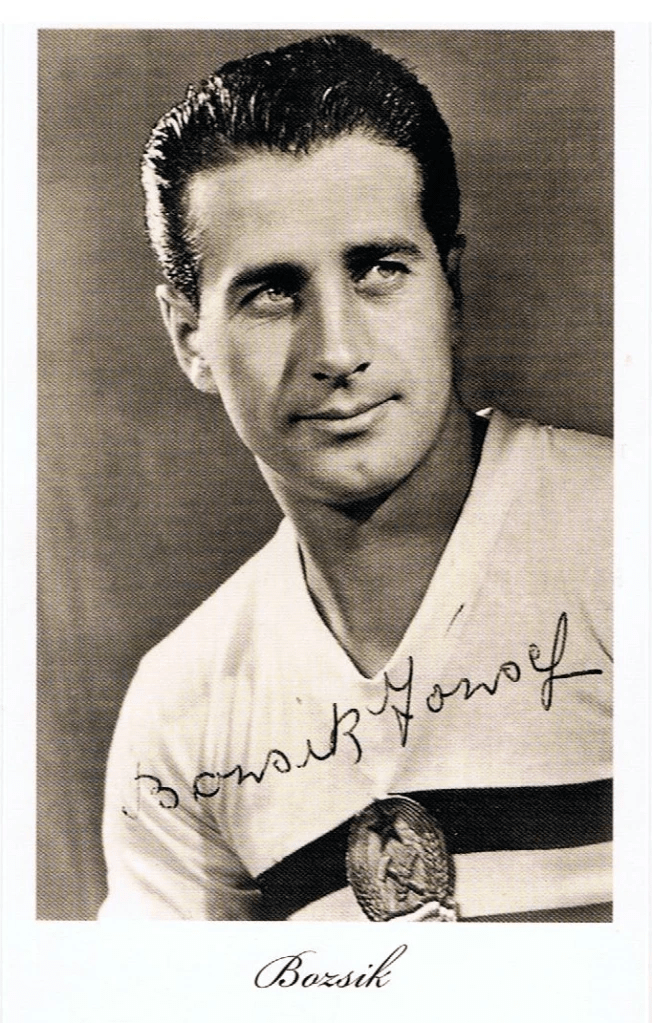

During and following their title-winning season in 1953-54, Wolves played hosts to a succession of European club sides, along with teams from as widely spread as Argentina (Racing Club of Buenos Aires) and Israel (Maccabi Tel Aviv), under the new floodlights at Molineux. The most famous of these matches was the game against Honved of Budapest, the crack team of the Hungarian army, eight of whom, including captain Ferenc Puskás, had been in the national team that had beaten England 6-3 at Wembley (the first time England had lost to a continental side on home soil), and 7-1 in Budapest, the previous season. Both these defeats were still fresh in the minds of English fans when, in December 1954, Honved arrived in Wolverhampton. Their team contained many stars from the national ‘Golden Team’ (Arany Csapat) which, besides Puskás, included his well-drilled comrade-soldiers, Bozsik, Kocsis, Lorant, Czibor and Budai.

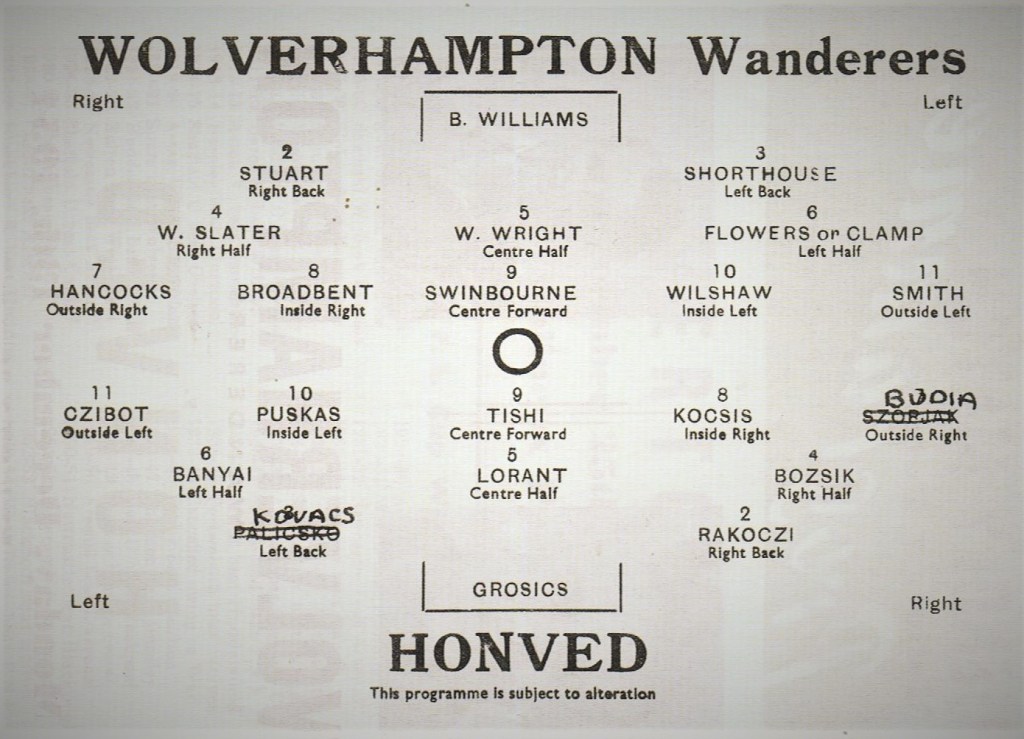

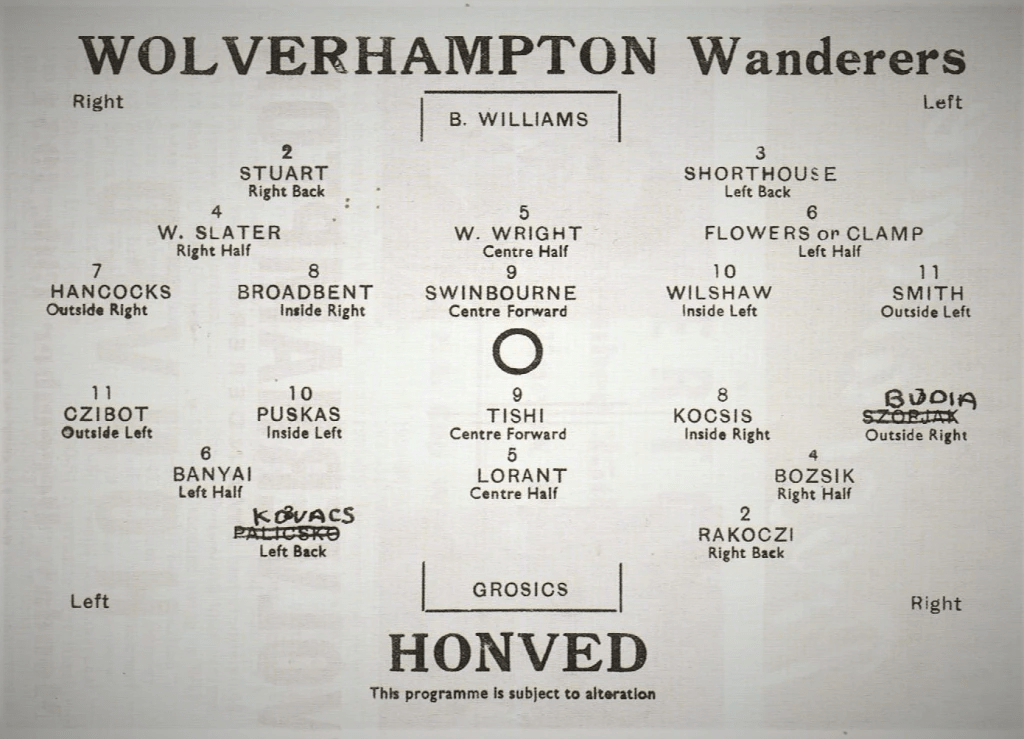

The full teams who ran out at Molineux behind the captains, Wright and Puskás, were:

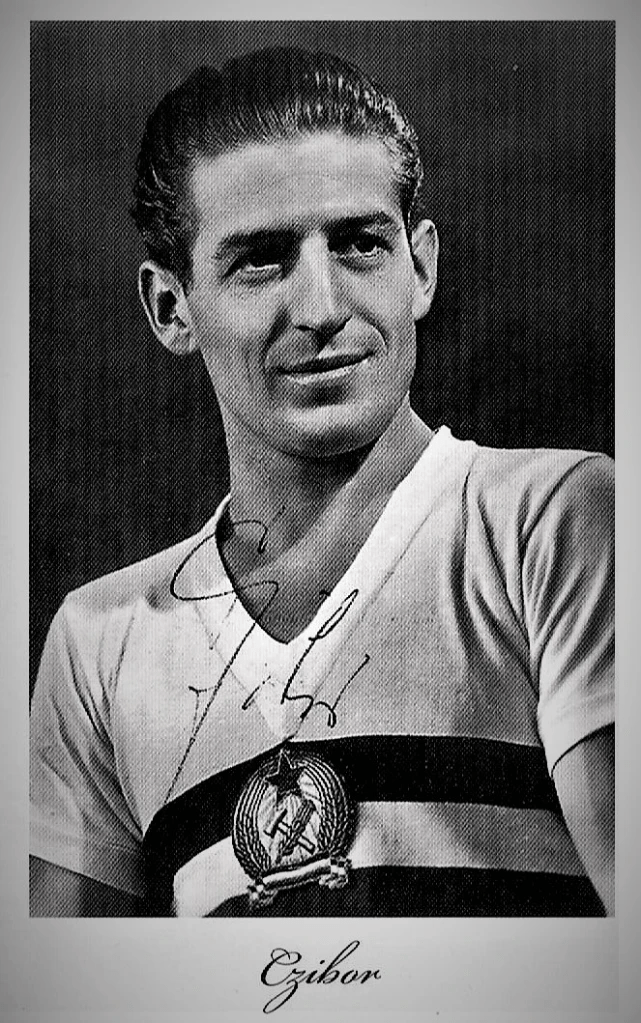

Honved: Farago; Rákóczi, Kovács; Bozsik, Lorant, Banyai; Budai, Kocsis, Machos (Tichy), Puskás, Czibor.

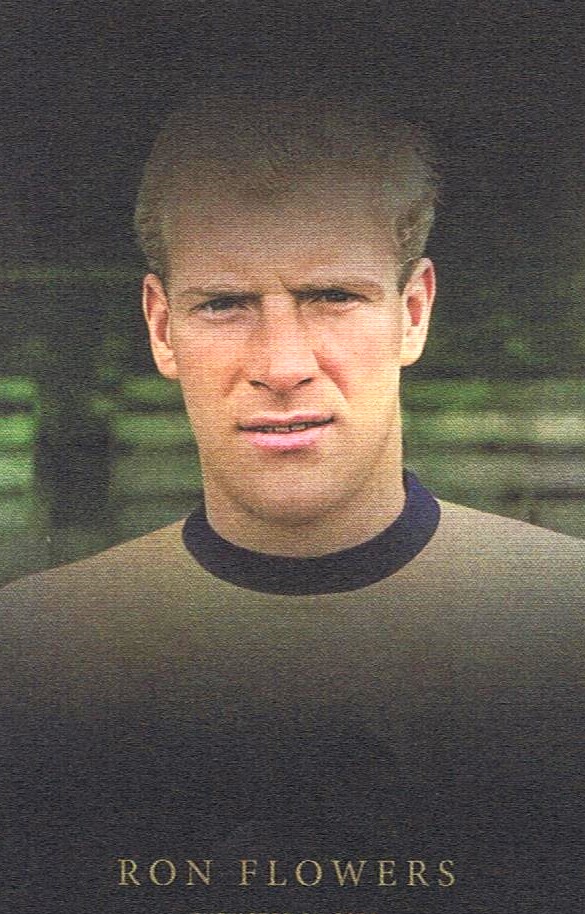

Wolves: Williams; Stuart, Shorthouse; Slater, Wright, Flowers; Hancocks, Broadbent, Swinbourne, Wilshaw, Smith.

Scorers for Wolves: Johnny Hancocks (penalty), Roy Swinburne (2)

Scorers for Honved: Kocsis, Machos.

Attendance: 54,998.

To understand the significance of the early floodlit matches, it is important to understand the peculiar social and political context and circumstances of this period of the Cold War, specifically 1953-58. The Hungarian national side, already Olympic Champions in 1952, should also have won the World Cup in the Summer of 1954, held in Switzerland, but were beaten in the final by a West German side which came from 2-0 down to win 3-2. Kocsis was the leading scorer in the World Cup and so, following their own sensational win over Spartak Moscow a month earlier, Wolves were keen to welcome the tormentors of England to Molineux. Since the England team did not meet the ‘Mighty Magyars’ in the finals (they were knocked out by Uruguay in the quarter-finals), this club match at Molineux the following December was billed as the ‘chance for revenge’ by Billy Wright and his boys.

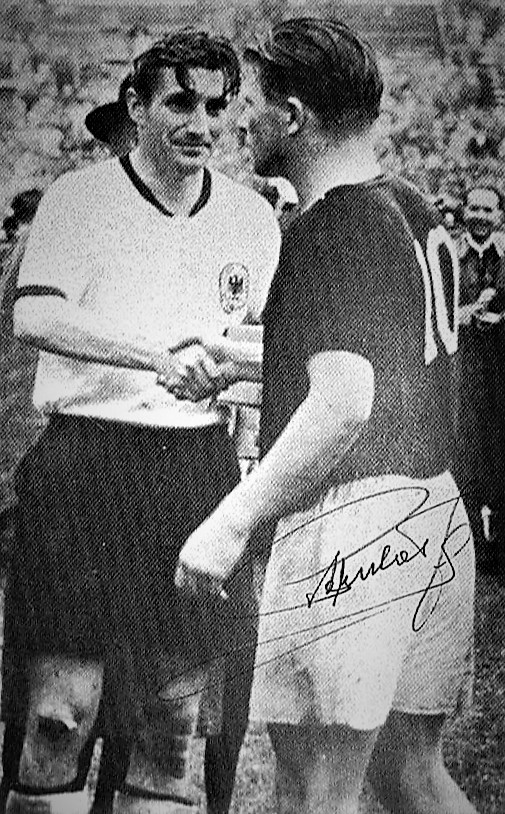

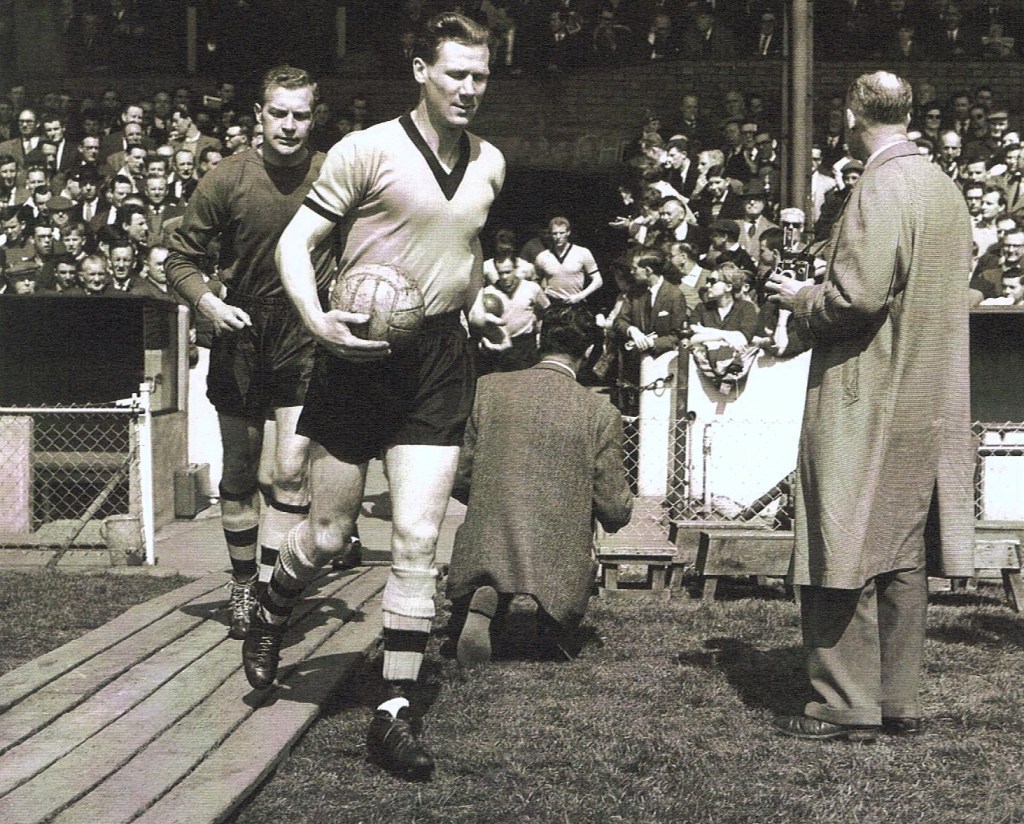

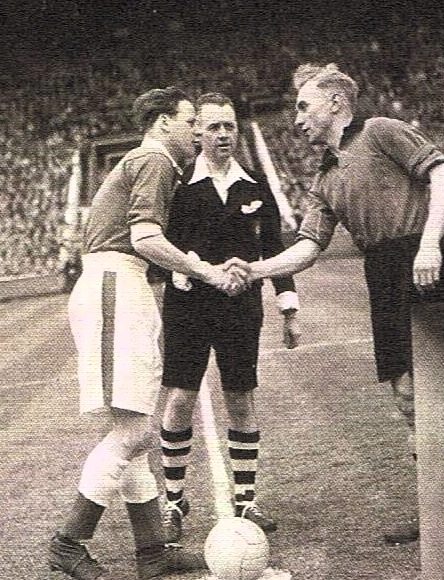

The game was played under the new floodlights on a Monday night, 13th December, with 55,000 cheering fans watching at the ground and many more on the new phenomenon of TV. The BBC broadcast the second half live on TV, and the whole match live on the radio. Just as they had led out their national teams in the games the previous season, Billy Wright and Ferenc Puskás were again side-by-side as the two teams ran out onto the pitch, Wolves wearing their golden rayon shirts to reflect the floodlights (pictured below). Billy Wright would have been fully aware of the threat Honvéd posed, having captained England games in the two heavy defeats to Hungary.

The visitors immediately began to play with fantastic ball control and speed of passing. As in the World Cup final, the Hungarian club team went 2-0 up in the first half, and were in full control, their precision passing and speed of attack drawing gasps of appreciation from the crowd. The first goal came from a pin-point free kick which found the head of Kocsis and the ball flew past Bert Williams in the Wolves’ goal like a bullet. This was followed up by a second from the speedy winger, Machos, who was put through the defence by Kocsis. That all happened in the first quarter-hour, but after that Williams pulled off a string of saves to keep the score down to 2-0 at the interval. As the teams left the field at half-time, the crowd rose to salute the Hungarian artistry, but the Wolves fans were worried that their team might be humiliated in the second half, just as the England team had been the year before.

In the second half, however, the Wolves called upon all their fighting spirit and energy reserves. During the interval, the Wolves manager, Stan Cullis, ordered the pitch to be watered again (it had been watered, as usual in winter, before the match). This prevented the pitch from freezing and becoming dangerous to the players. However, the softer surface conditions suited the Wolves’ long-ball playing style more than the short-passing style of the visitors. Johnny Hancocks (above) scored from a penalty soon after the re-start, and, with fifteen minutes left, and the Hungarians tiring on what had become a very muddy pitch, Roy Swinbourne (below) scored twice to win the match 3-2 in a second half televised live throughout Britain, with many national servicemen watching it in their barracks (including my cousin, John Hartshorne). Graham Hughes explained how the morale of one group of National Servicemen was boosted by the victory:

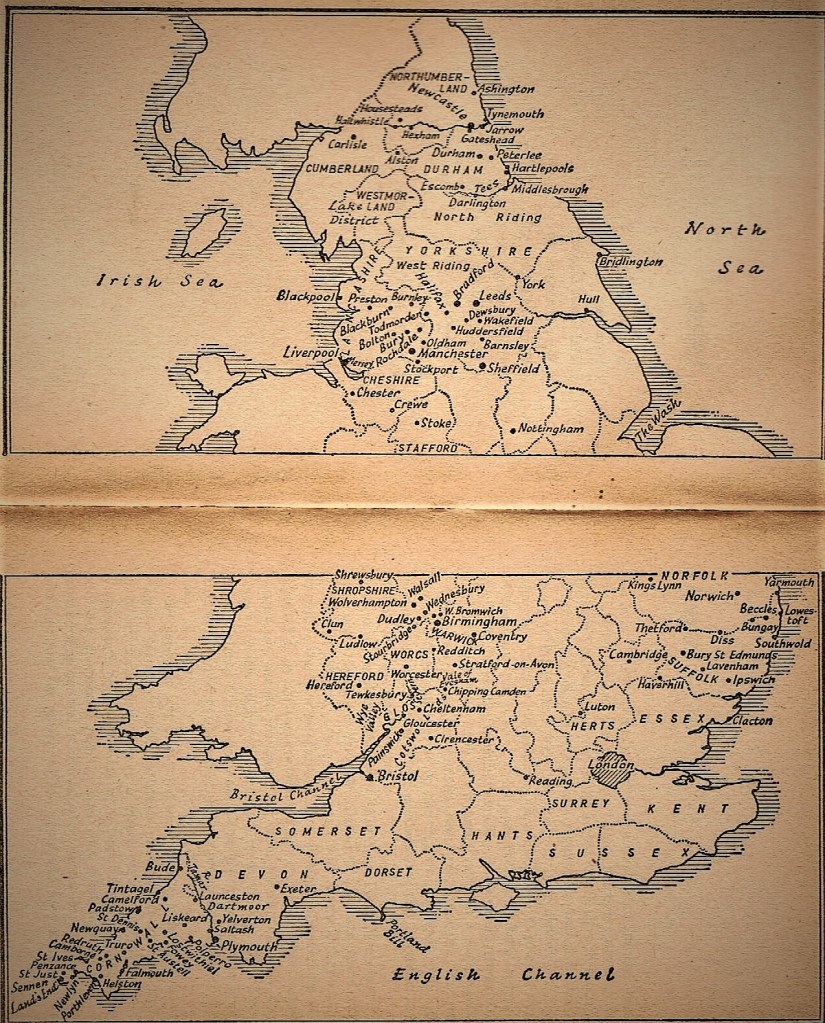

“In 1954 I was serving with the Royal Corps of Signals, stationed at at Sherford Camp near Taunton. On the day of the Wolves’ game with Honved our orders were to move chairs into the NAAFI so the servicemen could watch the BBC broadcast of the game. Myself and my two mates, Taffy Townsend and Les Cockin, being from Wolverhampton, were guests of honour and given front row seats; it was great. When Wolves scored the winner everybody jumped up, shouting and cheering: Scousers, Cockneys, Geordies, the lot; even the officers. In fact, the officers were so pleased, they ordered the NAAFI to stay open so we could celebrate Wolves’ win properly. Fantastic!”

Quoted in Shipley (2003), p.47.

The next day, Wolves were acclaimed as ‘Champions of the World’ in the English press, especially by The Daily Mail. Gabriel Hanot, a sports journalist for ‘L’Équipe’ responded by suggesting that this could only be proved by establishing a continental cup competition. He had long been campaigning for a European tournament, and he stated:

“Before we declare that Wolverhampton Wanderers are invincible, let them go to Moscow and Budapest. And there are other internationally renowned clubs: A. C. Milan and Real Madrid to name but two. A club world championship, or at least a European one – larger, more meaningful and more prestigious than the Mitropa Cup and more original than a competition for national teams – should be launched.”

Quoted in Wolves Museum Guide (2024), p. 17.

A variety of events led to the creation of the European Cup in the following season, 1955/56. However, the short-sighted Football League Management Committee refused to support Chelsea, the 1954/55 champions (they had four more points than Wolves, who finished as runners-up) in their application to take part. The Chelsea Chairman was very enthusiastic about the new competition. He sent a delegate to the April 1955 organising committee in Paris, but the Football League were suspicious of European club football and concerned about potential fixture congestion. They strongly advised Chelsea to withdraw, and the Blues reluctantly gave way to be replaced by Gwardia Warsaw. The only British club to enter this first-ever European Cup was therefore the Edinburgh club Hibernian, then considered to be Scotland’s top team, though they only finished fifth in the Scottish League (to begin with, it wasn’t necessary to be domestic League champions to enter). ‘Hibs’ justified their entry by reaching the semi-finals, losing 3-0 to French club Reims.

Meanwhile, in Hungary, there had been a strong public reaction to the ‘Golden Team’ losing in the World Cup Final the previous year. As Tibór Fischer, the historian with Hungarian roots put it in his best-seller, Under the Frog:

‘Hungarians don’t mind dictatorship, but they really hate losing a football match.’

Quoted by György Szöllősi, loc.cit., p. 28.

Following the defeat to West Germany in 1954, Hungarians turned against the national team’s management and against the wider political régime. Its leaders had for years basked in the successes of the country’s footballers, but now the coaches and players also felt the loss of confidence. The World Cup final constituted a turning point in Hungarian football, but its devastating effect was more palpable over a long period rather than in the short term. In the capital, shop windows were smashed and streetcars overturned before finally, the angry masses reached the Magyar Rádió building, where they handed in a petition stating that Gusztav Sebes should not return home after his ignominious failure. The spontaneous demonstration was soon put down, the ringleaders arrested and the press kept silent about the whole event. However, the disturbances were later seen as a precursor to the 1956 Uprising because this was the first time people could experience when they could and should raise their heads above the parapet.

But after the Berne final the national team went on another unbeaten run lasting a year and a half. Apart from a 2-1 defeat in a Moscow ‘friendly’ and the World Cup final, Sebes’ national team were undefeated in six years. The Hungarian Uprising and Soviet invasion in 1956 ended the run of Puskás’s magnificent men in the national team. By February 1956, the more and more anti-football dictatorship began a series of humiliations against the ‘spoilt’ footballers, as it portrayed them. On the 19th they suffered a 3-1 defeat by Turkey in Istanbul. This was followed by other defeats and unacceptable performances, which led to Sebes losing political influence and being ousted in the summer of 1956.

Sebes’s successor was Márton Bukovi, the MTK coach, who produced a five-match winning streak, reactivating Grosics (from scapegoating and house arrest under the previous régime) as goalkeeper while giving Puskás an ultimatum to get fit or lose his place. After victories over Poland, Yugoslavia, the USSR, France and Austria, the national team was preparing for a match against Sweden when the anti-government demonstration began, followed by an armed uprising. Zoltán Czibor (below) was a well-known anti-Communist and he helped Puskás get passports for the squad from the new government of Imre Nagy. On 1st November, Honvéd set off for their European Cup match with Athletico Bilbao, due to take place in Spain three weeks later. Vörös Lobogó (‘Red Banner’) (MTK) had competed for Hungary in the inaugural competition the year before.

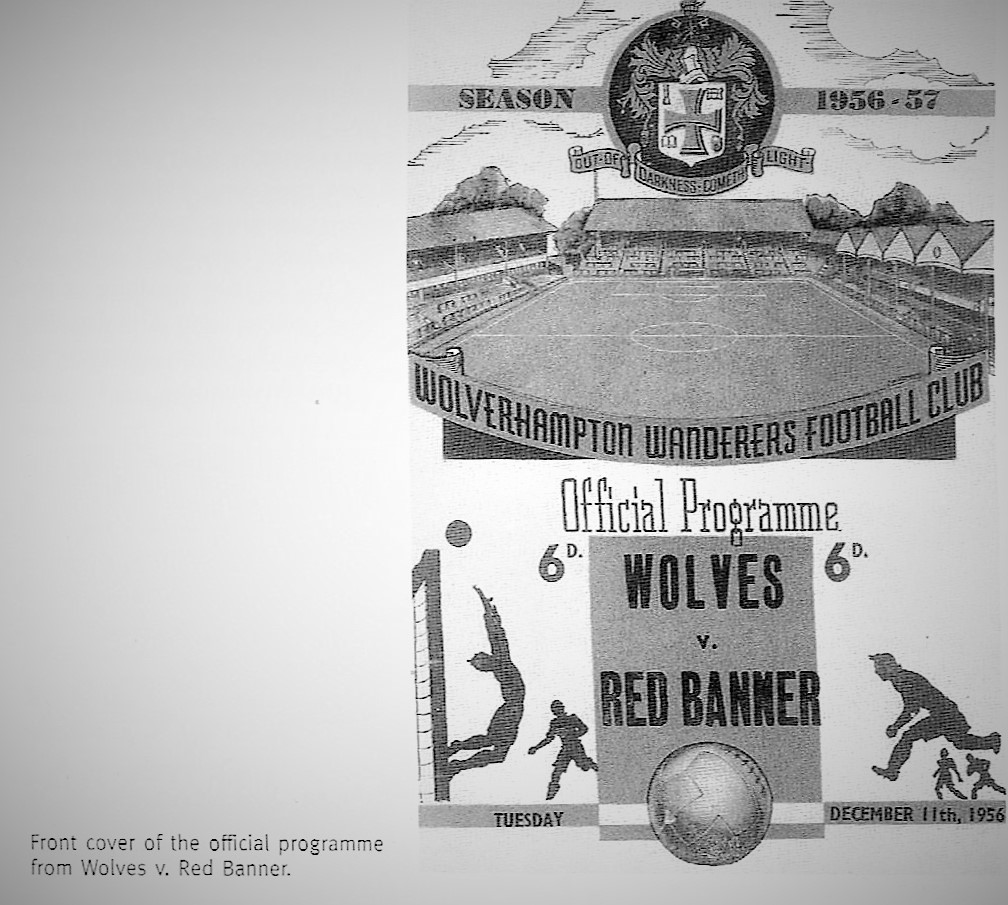

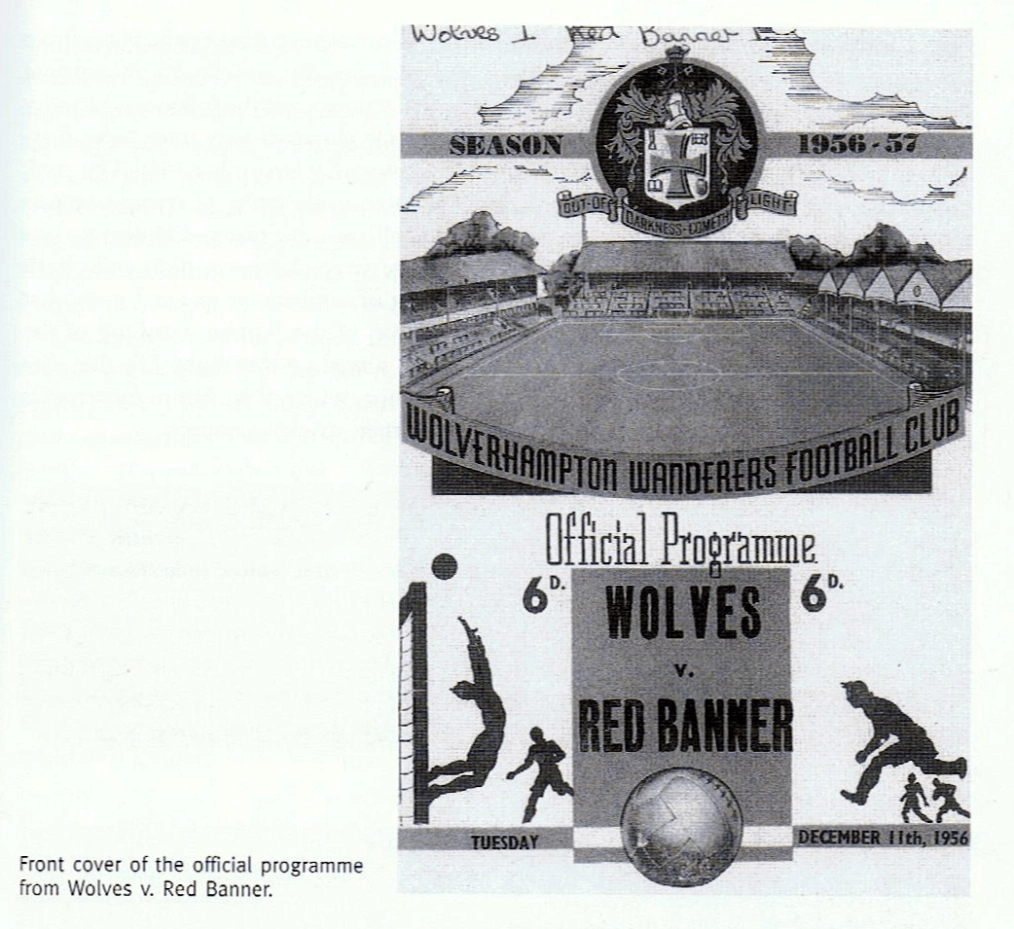

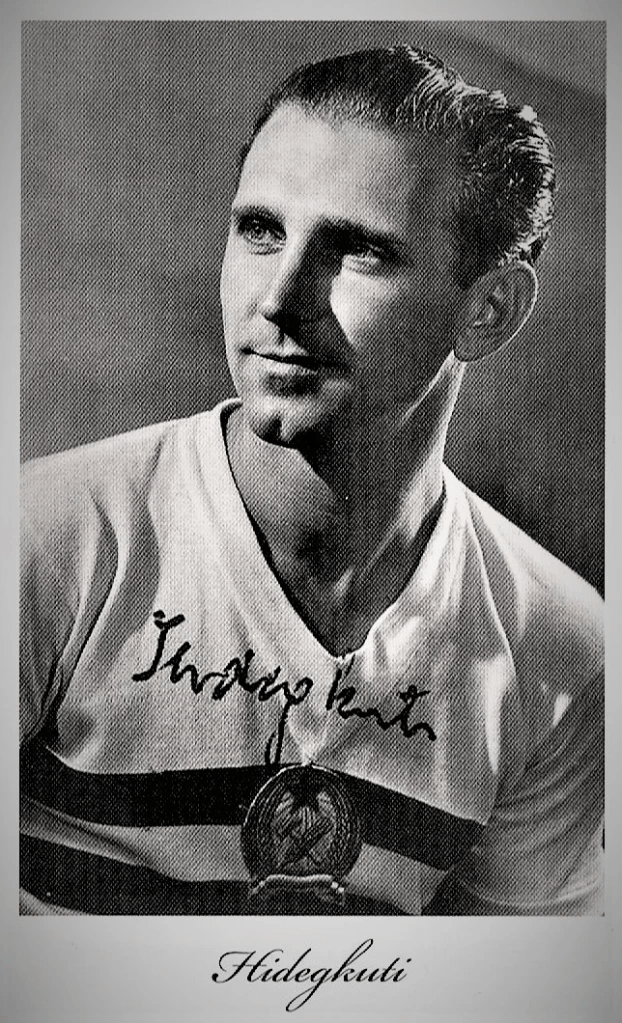

However, three days after the team left Hungary, the Soviet tanks streamed across the eastern border to put down the uprising. The Honvéd players did everything they could to get their families out of the country. Puskas’s wife and their four-year-old daughter managed to cross into Austria on 1st December. The first leg of the Athletico Bilbao match had finished 3-2 to the Basques, and the return leg took place on 20th December in Brussels due to the volatile situation in Budapest. It finished 3-3, so Honvéd were out. Understandably, many of the players, including Kocsis and Puskás himself, decided against returning home to Budapest, preferring to ply their trade in the ‘free world’. In December, two years to the day of the Honved match, a benefit match for Hungarian refugees was played at Molineux, again under floodlights, with ‘Red Banner’ (MTK) Budapest as opponents. The team included four internationals, with Hidegkúti at centre-forward, who combined brilliantly with Palotás.

The home team was not exactly ‘howling’ at the Hungarians’ gates, however, and ‘the Molineux murmur’ of dissatisfaction soon began as the crowd sensed that their team was holding something back. To be fair, they found it difficult to break down the visitors’ defensive system, one of the coolest under pressure ever seen at Molineux to that date. The Magyars took the lead when Palotás whipped the ball past the diving Bert Williams after some world-class footwork by Hidegkúti.

Wolves drew level from a Hooper corner, which was palmed away by Veres, but only as far as Neil who had drifted outside the goal area and was unmarked. His smartly hit shot passed through the ruck of players and beat Veres on the line. The cool, calculated football of MTK sometimes became over-complicated. They were all too frequently guilty of playing one pass too many. At half-time, the talented Hidegkúti was replaced by Karasz, but the game was far from dull, however, with both goalkeepers acquitting themselves well by making strings of acrobatic saves.

MTK became only the second team to escape floodlit defeat at Wolves’ Molineux ‘lair’. But the 1-1 scoreline was largely irrelevant since the match did not live up to the reputation of Hungarian football, no matter how hard MTK tried. The solemnity of the occasion, set against the Soviet crushing of the Hungarian Uprising, meant that the football served up on the night was not as slick as that of the Honved match of two years earlier. The day after the match, the Hungarian players and officials made their way back to Vienna, unsure of their onward movements, given the course of events in their stricken country. What mattered most to them was that the attendance receipts had raised 2,300 pounds for the Hungarian Relief Fund, and the memorable speech of the Wolves Chairman, James Baker, at the pre-match banquet. He referred to the Wolves’ motto, ‘out of darkness cometh light’ (which is also the motto on the Wolverhampton civic crest, below), and expressed the hope that would soon be proved true in their native land.

The day after the match, the Hungarians were on their way to Vienna, where their onward movements would be dictated by the course of political events in the shape of the continued Soviets’ crushing of the Hungarian Uprising. Meanwhile, the Honvéd team and their relatives were spending Christmas in Milan after being knocked out of the European Cup. By taking their fate into their own hands, the team could now take up the offer of a fairytale tour of South America, starting in Brazil. The offer was lucrative enough for them to be able to ignore the pleading of Guszstáv Sebes, who was sent by the once-again firmly entrenched Hungarian Communist Party to persuade the players, with threats and pleading, to return to Hungary. After their successful tour, which went ahead despite international sanctions, the team returned to Europe and most of the players eventually found their way back to Hungary, knowing that punishments awaited them. The most serious of these would apply to Puskás as team captain, a one-year ban. He was also infuriated by Hungarian newspaper articles obtained in Vienna, which slandered him, and he and his wife were emboldened to remain abroad, together with their daughter, Czibor, Kocsis and most of the touring Hungarian youth team.

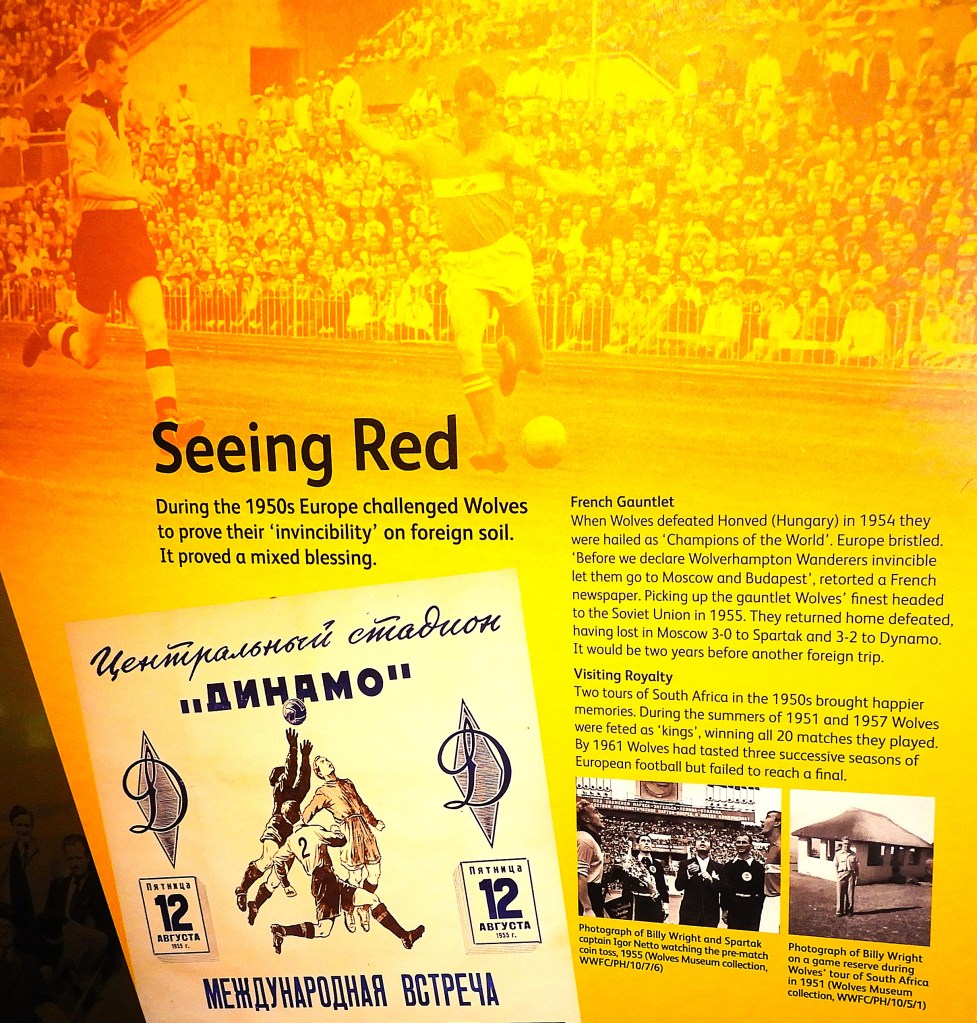

Official European Competitors, 1957-60:

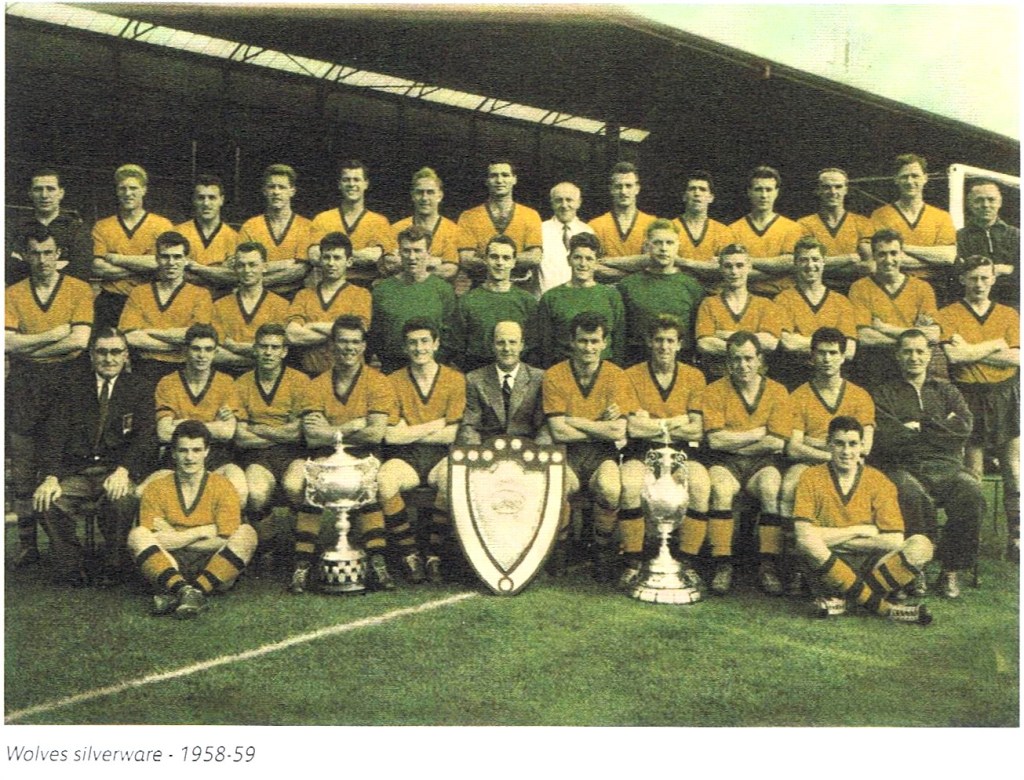

Meanwhile, Wolves had not been distracted by their friendly European matches from domestic competition, remaining strong in the League, finishing second in 1954-55, third in 1955-56 and sixth in 1956-57. They took the First Division title for a second time in 1957-58.

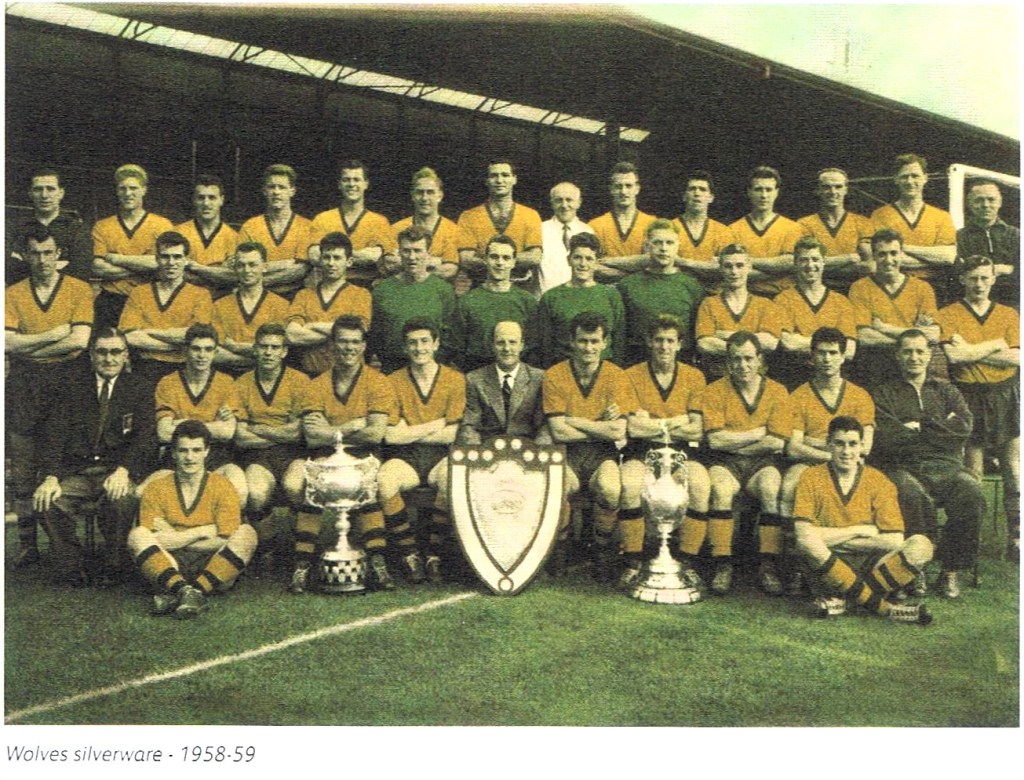

Victory also came in the Charity Shield at the end of the 1958-59 season, the only time Wolves have won it outright.

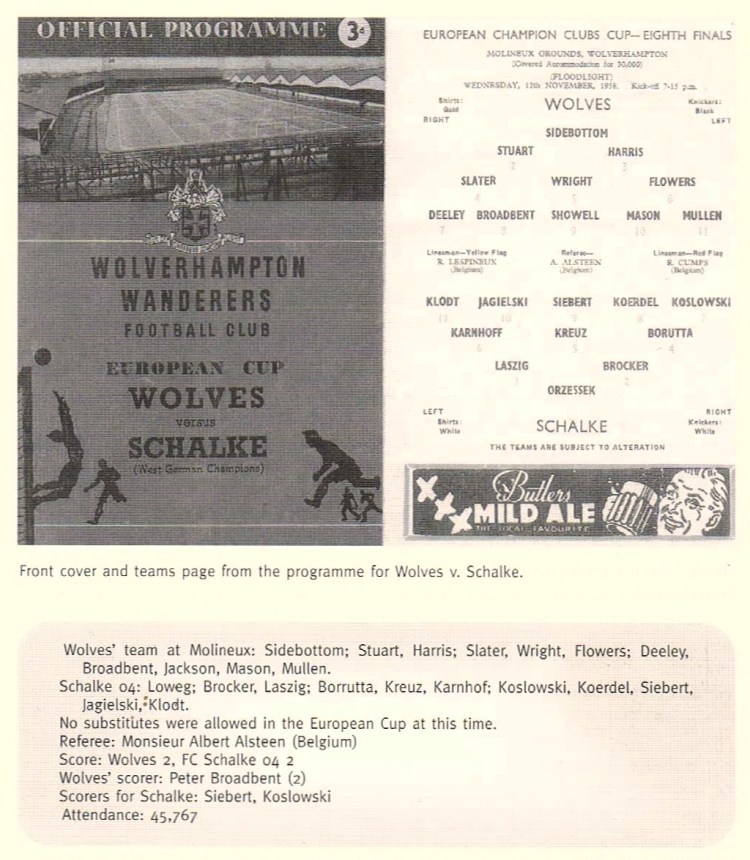

At the end of the 1957-58 season, they were finally able to accept an invitation to play in the European Cup, the Football League having overcome their previous aversion to the competition. Wolves can therefore lay claim to being the pioneers of the European Champions Cup, following their famous floodlit friendlies, though they were not the first English team to play in the competition. That honour fell to the ill-fated Manchester United team, League Champions in the previous season. Tragic scenes accompanied the Munich air crash on 6 February 1958, bringing tears to many football fans’ eyes, not just in Manchester or England. To lose so many young, gifted stars in a single disaster was devastating. Wolves became only the second English team to play in the European Cup in 1958-59, but their debut against FC Schalke at home resulted in a disappointing 2-2 draw; they lost the tie to the West Germans 4-3 on aggregate.

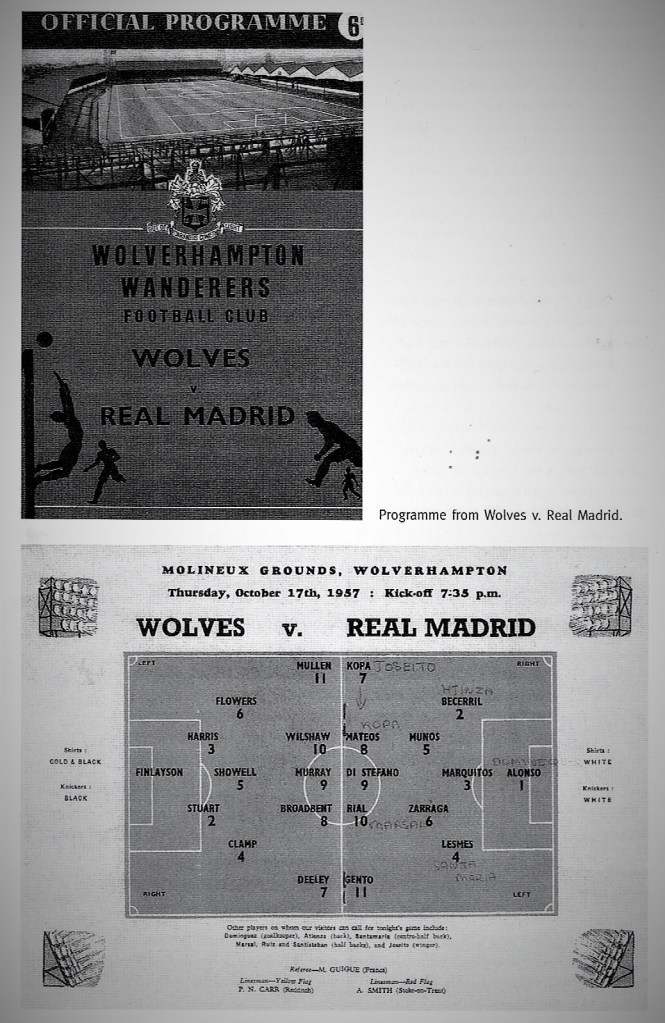

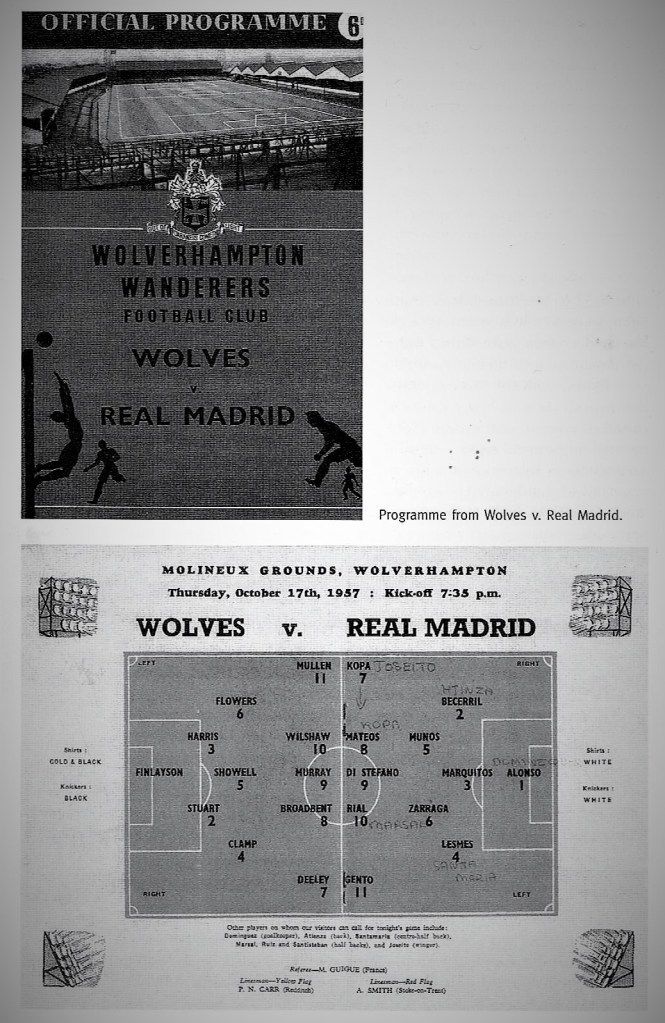

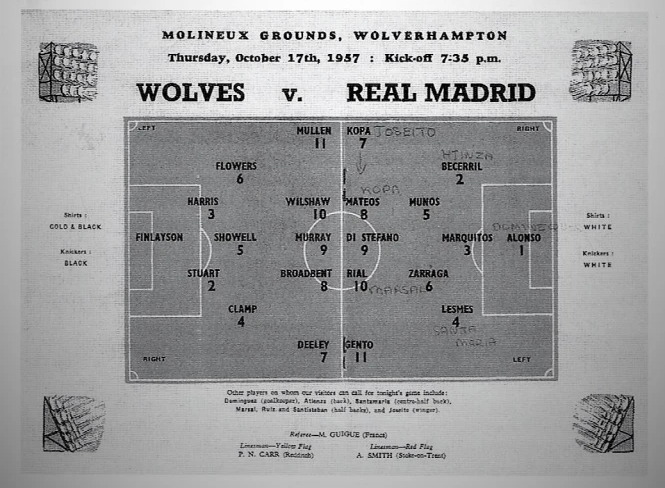

The first five European Championships were won by Real Madrid, with Puskás playing for them from 1958. Fortunately for Wolves, he hadn’t yet started playing for them In 1957, when they beat the Spanish champions 3-2 in a floodlit friendly at Molineux. Wolves were again crowned League champions in 1958-1959, and FA Cup winners in 1960. They suffered a further loss in the European Cup (Quarter-final) to Barcelona by a staggering 9-2 on aggregate with Sándor Kocsis, the fabulous Hungarian striker, now exiled in Spain, scoring four in the return leg at Molineux in March 1960. The match marked the end of an era as Wolves lost their hard-won and much-coveted record of ‘unbeaten under Molineux lights’.

The Cup Final win over Blackburn meant that, though pipped to post by Burnley in the final round of League games, they qualified for the inaugural European Cup Winners Cup. Besides the defeats to Schalke and Barcelona, Wolves also went behind the ‘iron curtain’ to beat Vorwaerts of East Berlin (3-2 agg.) and Red Star Belgrade (4-2). There were also more famous friendly nights under the lights against Dynamo Moscow, CCA Rumania, Borussia Dortmund and Valencia. These European experiences form a significant part of the impressive and recently revamped displays in the Wolves Museum at Molineux.

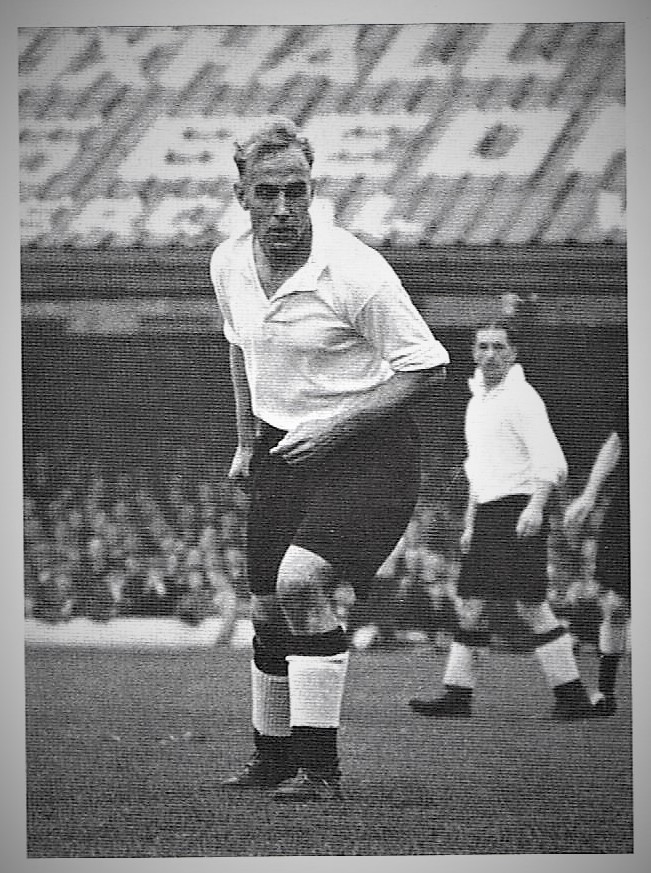

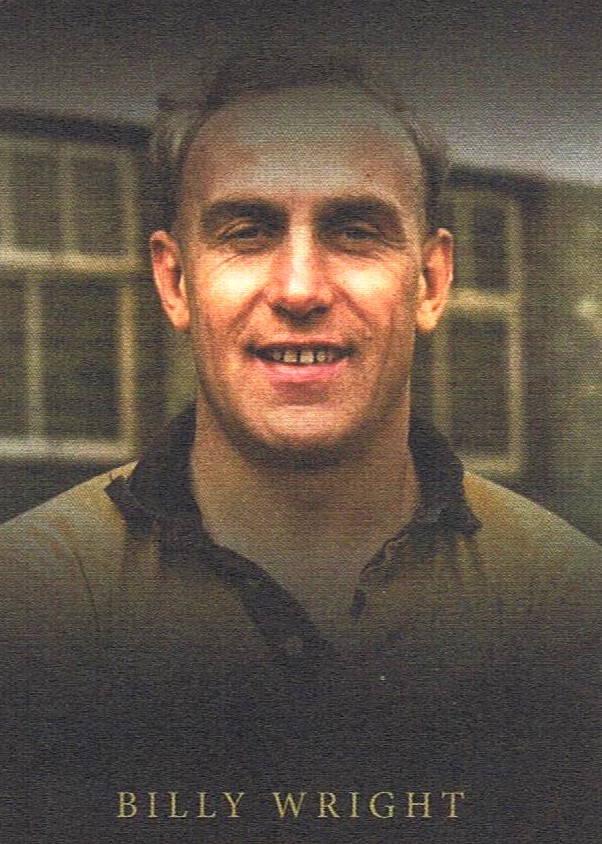

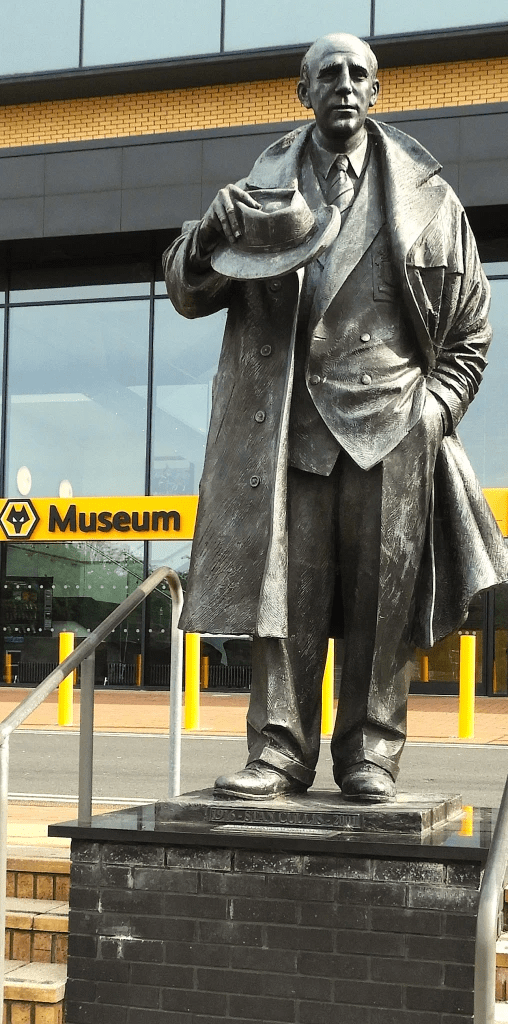

The two men who led the Wolves’ ‘Golden team’ of the fifties were Stan Cullis as the Manager and Billy Wright as skipper. The success both had with Wolves is known and recognised by the statues outside Molineux and the two Stands named after them. Cullis, a fine player in his day, managed Wolves in all five-trophy successes. He was, like his manager when playing, Major Buckley, a strong disciplinarian and a coach who insisted on fitness first and foremost. Cullis was undoubtedly the best Wolves manager ever, and most recent and current fans would say that he remains so. But the start of the 1959-60 season was marred for him when the Wolves legend Billy Wright dropped a bombshell by announcing his retirement, aged thirty-five. He reportedly told a reporter;

“Yes, this is it. I have had a wonderful run with a wonderful club and I wanted to finish while I am still at the top.”

Stan Cullis was reported to have said that, under no circumstances, would he ask Billy to play in the reserves, but would want him to finish as a first-team player. So Billy played his farewell match at Molineux in Wolves colours in the pre-season charity match on Saturday 8 August 1959. Although Billy’s news was bad for the Wolves it was good for the charity, as a larger-than-usual crowd was expected to turn out in honour of their captain. In fact, twenty thousand fans turned out, twice the usual number for the charity match. In a later interview, Wright acknowledged that he had told reporters the previous April that he was ‘good for another season at least’, but added that since he had got his hundredth England cap, and had been awarded a CBE, he had thought it over and decided that it was time to quit. Cullis wanted Wright to take over as his chief coach, with specific responsibility for the club’s youngsters. Billy hadn’t decided on this but confirmed that he would not move to play for another club. ‘How can I play for anyone else after Wolves?’ he said. He did, however, become Arsenal’s manager in the summer of 1963.

Wright was captain in all Wolves’ trophy triumphs except the second Cup Final success, which came in 1960, eleven years after he had lifted the trophy for the Wolves’ first Wembley triumph. Born in Ironbridge, Shropshire, Billy had joined the groundstaff at Molineux in 1938 and, after initially being turned down by Buckley for being too short, made his debut as a player in 1939 before turning professional in 1941. Wright made a total of 541 appearances for Wolves, scoring sixteen goals. He was the first person in the world to play for his country one hundred times and gained 105 caps in all, the first in 1946, only surpassed by Bobby Charlton (106). On ninety of those occasions, he captained the team, playing in three World Cup finals. In his exemplary twenty-year career, he was never sent off, nor even booked. He was regarded not just as a great player and captain, but as a true gentleman. Voted ‘Footballer of the Year’ for 1951-52 and ‘European Footballer of the Year’ runner-up in 1956-57, Billy won everything and achieved everything in his illustrious career which ended with presenting matches on independent TV in the seventies. As a captain, he was the ‘rock’ around which Stan Cullis built his team.

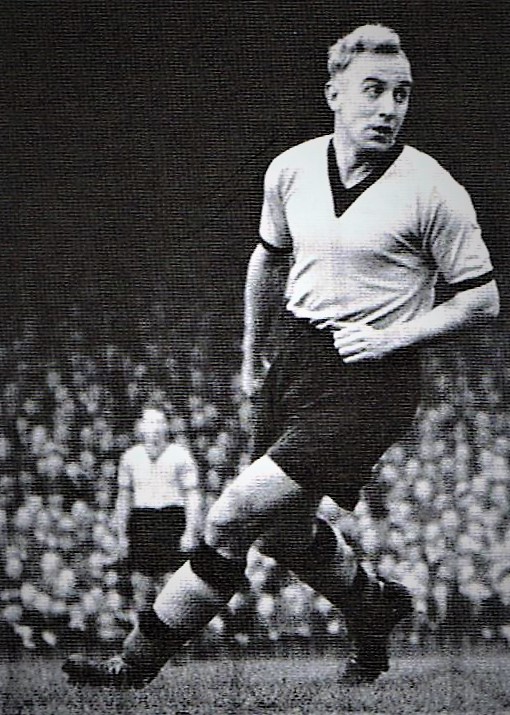

Some of the other iconic players from this era whose names I heard repeatedly from my father, uncle and cousin were those of the wingers, Hancocks, Deeley and Mullen; forwards Swinbourne, Wilshaw and Murray; defenders Slater and Flowers, and goalkeepers Williams and Finlayson. The only player from the fifties team I personally saw play was Peter Broadbent when I was taken to Molineux by my Dad in the mid-1960s, from the age of eight. He was arguably the best of them all according to those who saw the other great players, and was the reason George Best was a Wolves supporter as a boy. Best had seen him play in the second halves of the floodlit games which were shown on BBC television and tried to copy his style. Broadbent had scored Wolves’ first goal in the 3-2 win against Real Madrid in October 1957, a victory which marked the pinnacle of Wolves’ floodlit fest.

Glory Days, Floodlit Nights:

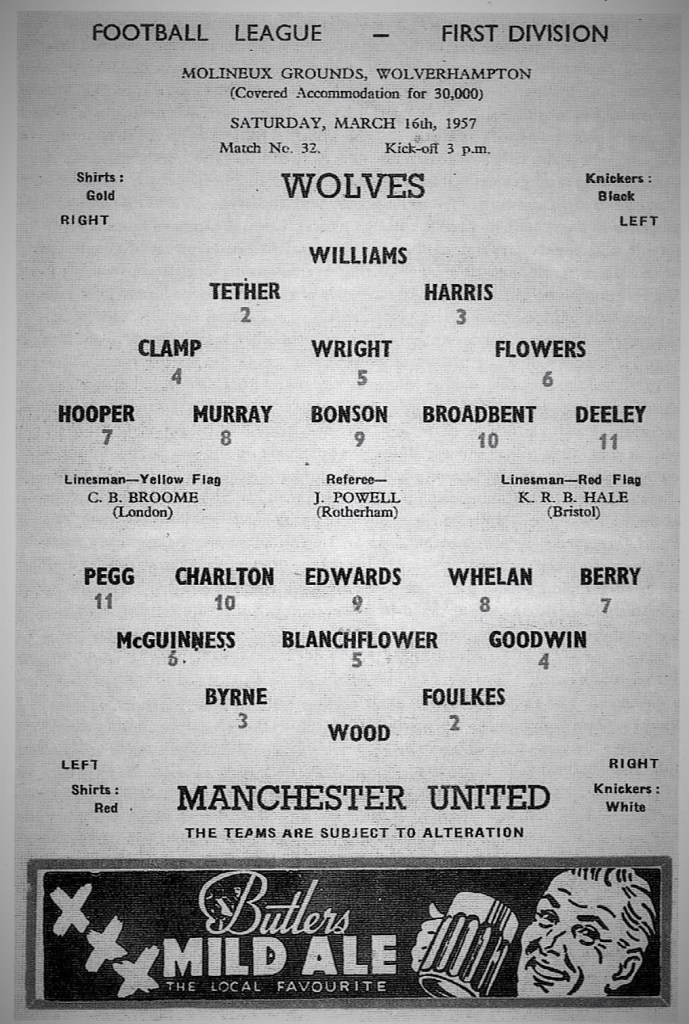

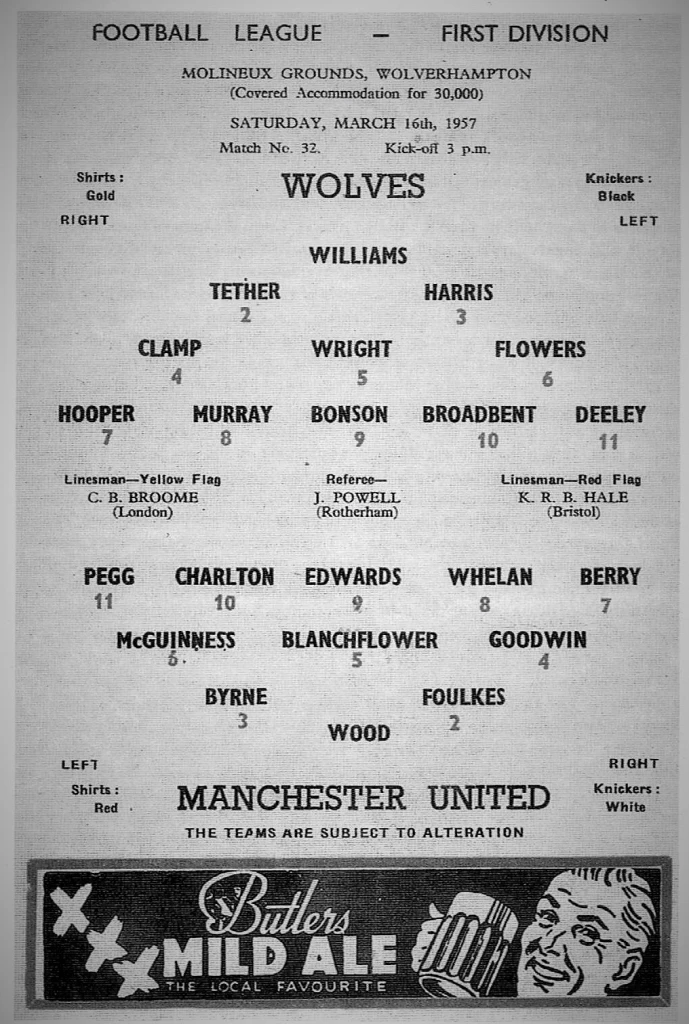

John Shipley, a lifelong Wolves fan from Bridgnorth, first entered Molineux ‘through the front gate’ as a fourteen-year-old schoolboy for the 1957 match between Wolves and Manchester United at Molineux, three years after Wolves had triumphed over Moscow Spartak and Honved of Budapest in the series of floodlit matches.

John reflected on those experiences in his 2003 book:

‘I adored those magical night games… the lights, satin shirts, the excitement, the fantastic attacking football, the ball swinging wing to wing from the boots of Johnny Hancocks and Jimmy Murray… I reckoned that all my Albion mates were pig-sick with jealousy. They had good reason in spite of their own, not insignificant, success because throughout the 1950s Wolverhampton Wanderers went from strength to strength, competing against, and beating, the best teams in Europe, plus giants from other parts of the world; pioneering in every sense. Wolves spearheaded English football’s European onslaught in those heady days. The team in the distinctive old gold and black won a fearsome reputation, and in the process salvaged the English pride that had been so badly dented by the great Hungarian team of the 1950s.’

John Shipley watched the majority of the floodlit games from a strategic vantage point in the South Bank, not far from where I found during my own viewpoint, in the years 1965 to 1975 when, after settling with my family on the boundary between Birmingham and Smethwick, I regularly went to Wolves matches with my father and his Black Country relatives. Fifty years later, I’m looking forward to revisiting Molineux, this time to see a floodlit match, once the Wolves return to European football. It’s worth remembering that these games were born out of a spirit of friendly rivalry and transcontinental cooperation after decades of violent conflict between European nations. Football, and Sport more generally, is not separate from the rest of human activity; it is an expression of its most creative impulses. This was certainly the case in this early post-war era when nationalism was replaced by idealism and before it in turn was supplanted by materialism.

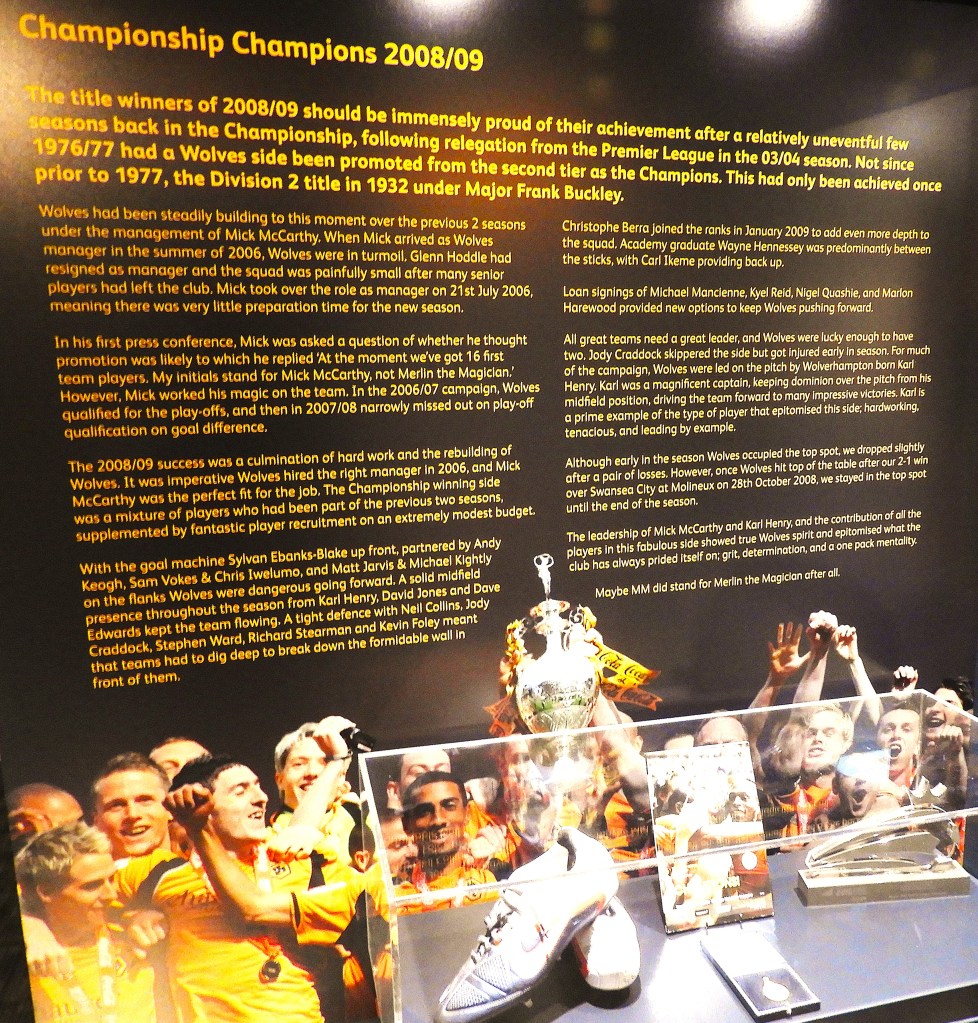

Into the Sixties – Swings & Roundabouts:

It may have seemed to many fans that the Wolves ‘golden era’ was drawing to a close at the end of the decade, but, of course, the great team of the fifties did not suddenly ‘give up the golden ghost’ when the clock struck twelve on 31st December 1959. The new decade began brightly with a fantastic FA Cup win, with Wolves defeating Blackburn Rovers at Wembley in 1960, which meant that they qualified for the inaugural Cup Winners Cup. They were also close to winning the League in 1960, which would have given them three titles in a row, besides winning the double, the first team to do so that century.

From 1949 to 1960 Wolves had won three First Division League Titles and two FA Cups. In 1960-61, the Wolves played in Cup Winners Cup ties against Austria Vienna and Glasgow Rangers. They also finished third in the League but dropped to eighteenth in 1961-62, not far from relegation. However, this turned out to be a temporary dip as in the following season they were back up to fifth. The Old Gold had great victories in the League in 1962-63, thrashing Manchester City 8-1 and West Bromwich Albion 7-0 at Molineux. Although not in official European competition, they once again entertained Honvéd at their home in December 1962. However, this time there was no clamour for tickets like there had been eight years earlier, since Hungarian football had suffered a decline since the Soviet invasion. Gone (to Spain) were the legendary Puskás, Kocsis and many others of the talented Hungarian ‘Golden Team’ of the fifties. The Honvéd team were no longer the pride of Hungary and Europe, but they were currently second in Hungary’s top division, and would still prove excellent opponents for the Wolves.

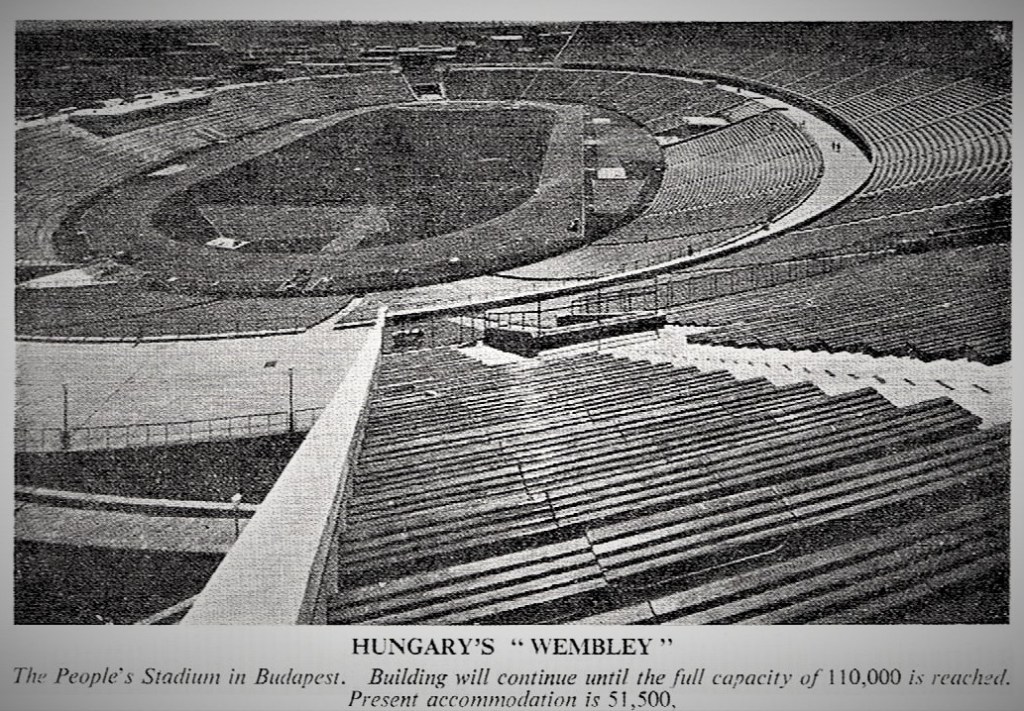

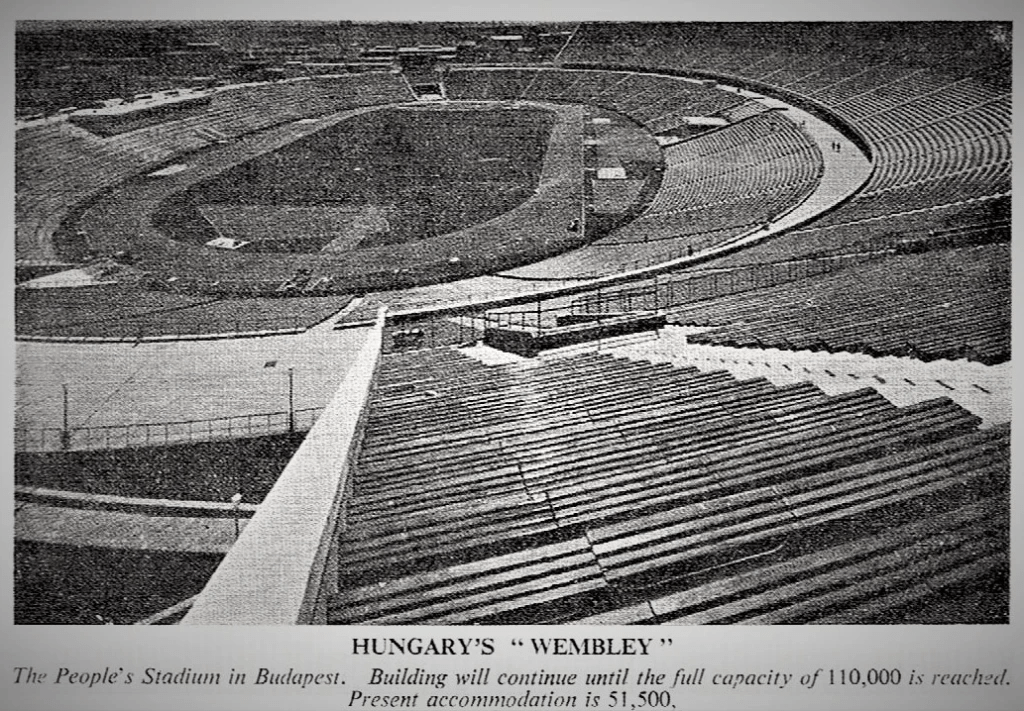

Flowers, Slater and Broadbent from the class of ’54 were happy to renew old friendships and rivalries with two ‘Mighty Magyars’: József Bozsik was, by then, club president and Gyula Lóránt club coach. The one player they recognised from previous ‘outings’ who lined up against them was goalkeeper, Lajos Farago, who had been understudy to the great Grosics in 1954. He had been almost invincible in his previous Molineux appearance and was now between the sticks again. Farago’s brilliance apart, however, the match bore scant resemblance to the 1954 classic. Then, ten minutes from time, Honvéd’s speedy winger, Vági, broke free but fluffed his chance. With five minutes left, Komara clipped the ball over to Nagy to score what everyone thought was the winner, but Wednesbury’s Alan Hinton crashed home a terrific equaliser past Farago, saving the Wanderers’ blushes. Bozsik announced that he wanted to make the match an annual event, and a year later the teams met again in Budapest. Wolves travelled to Budapest to play a friendly against Honvéd on 6 October 1963, losing 2-1 in the Népstadion (‘People’s Stadium’).

By the end of the 1962-63 season, Wolves had completed ten years of floodlit friendlies. Between September 1953 and December 1962, they played seventeen games, winning thirteen and drawing four, all against continental opposition, except for Glasgow Celtic. In addition, there were six home European ties at Molineux, with the Wolves winning three, drawing four and losing only once, to Barcelona. The following summer, Wolves embarked on a new venture, a tour of North America, playing against Mexican, Canadian, American and Brazilian teams. Also that summer, a new international era began when Alf Ramsay, who was in the England team beaten by the Hungarians in 1953, replaced Walter Winterbottom as England manager. In 1963-64, the fortunes of the Wolves team took a distinct turn for the worse as European qualification became no more than a distant dream. The team’s performance worsened, culminating in relegation at the end of the season. The Chairman, James Marshall, handed over the reins to John Ireland and two months later, Ireland sacked Stan Cullis who had been suffering from a long illness. This was on 15 September 1964, following defeat in the first three league matches, a draw in the fourth and further defeats in the next three. Attendances had dropped significantly. In their eighth match, Wolves managed a 4-3 victory over West Ham at Molineux, but this came too late to rescue Cullis from ‘the axe’ a day later.

For a decade and a half, Stan Cullis was Wolverhampton Wanderers. A proud and dedicated man, he was one of a small breed of footballing ‘giants’ who achieved greatness both as a player and a manager after joining Wolves as the former in February 1934. As a player, he was a tough-tackling centre-half, good in the air and shrewd in passing the ball. A ‘born’ leader, he captained Wolves before his nineteenth birthday and England a few months later. He was a member of Wolves’ 1939 Cup Final team, but hung up his boots in 1947, becoming manager the following year, the youngest to manage any club at this level. His full managerial record over sixteen years included two FA Cups, three First Division Championships, and nine other top-six finishes, three times as runners-up.

In the last of these, he almost won ‘the double’ in 1960, finishing one point behind Burnley. After leaving his belovéd Wolves four years later, he was appointed manager of Birmingham City. Meanwhile, caretaker-manager Andy Beattie, appointed in November 1964, failed to keep Wolves up and they were relegated to the (then) Division Two. Thus ended an unbroken top-flight record of twenty-two seasons, from 1936-37 to 1964-65 (excluding the war break), during which Wolves were Champions three times and runners-up five times, with nine other top-six finishes. They finished lower than this in only five seasons.

Sources:

György Szöllősi (2015), Ferenc Puskás: The Most Famous Hungarian. Budapest: Rézbong Kiadó.

György Szöllősi, Zalán Bodnár (2015), Az Aranycsapat Kinceskönyve (‘The Golden Team Treasure Book’). Budapest: Twister Media.

Bán Tibor & Harmos Zotán (2011), Puskás Ferenc. Budapest: Arena 2000.

John Shipley (2003), Wolves Against the World: European Nights, 1953-1980. Stroud (Glos.): Tempus Publishing.

Molineux Stadium (2024), Wolves Museum Guide, Third Edition.: Wolverhampton: Synaxis Design Consultancy.

Gallery: