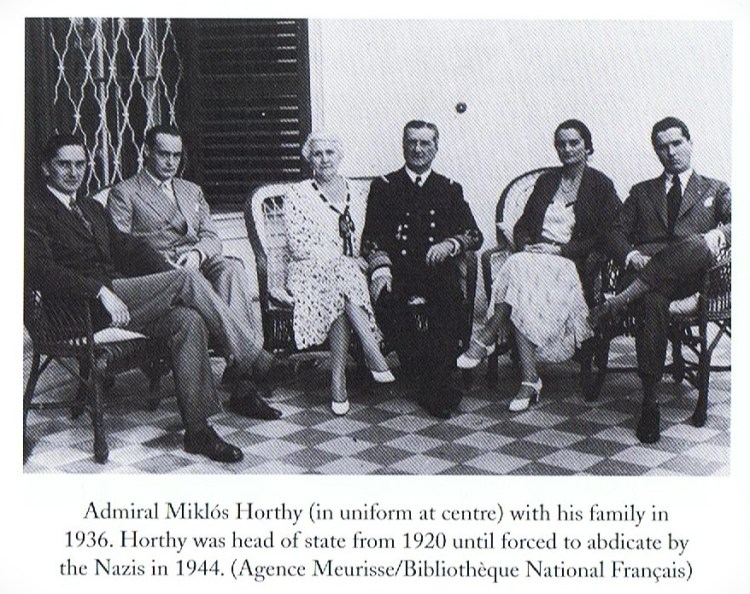

Chapter Five: Hungary under Horthy – In the Eye of the Hurricane:

It was largely the impossibility of reconstructing the order of Europe and the wider world as it was in January 1919 that swept away the ‘pacifist democracy’ that took over Hungary at the end of the First World War. It thwarted the first chance that the country obtained for a transition to democracy in the twentieth century. The democratic experiment was quickly followed by first red, then white terror, and the flaws and shortcomings of the peace treaty system dictated by the Allies lent credibility to the inherent nationalism and revisionism of the conservative régime that came to dominate the following two decades. The war, and to some extent the peace settlement, dealt a mortal blow to the conservative institutions of the multi-national empires of Central-Eastern Europe. Nationalism triumphed in the belief that this was consistent with the cause of liberty and democracy, and very few lamented the fall of the Hohenzollern, Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman emperors. The Western Allies, who won the war and made the peace were motivated not just by the ideal of national self-determination, but also by power policy considerations in their disregard of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy; they believed that its ethnic minorities, once liberated from imperial oppression, would automatically emerge as liberal democracies and be able to play the traditional Hapsburg role of ensuring the central-eastern European balance of power.

Both these assumptions proved to be fundamentally wrong. With the partial exception of Czechoslovakia, the democratic credentials of the new states were rather weak. The Peace settlement failed to solve ethnic tensions in the region’s countries and created new ones. Socio-economic backwardness fuelled nationalist sentiments, creating disunity between the potential partners and making them a poor match for the potentially formidable strength of the losers of the peace settlement. These included, besides Germany, Austria and Hungary, Italy and Soviet Russia, which suffered significant territorial losses and were ignored altogether at the peace conference.

After Trianon – Treaties & Alliances:

Domokos Szent-Iványi wrote in the foreword to his (1977) book, The Hungarian Independence Movement, 1939-46:

‘Over the past centuries, Poland and Hungary, arguably the two strongest political units in East Central Europe have played an important historic role by forming a huge bulwark which has allowed Western and Central Europe to develop in its protection.’

‘With the peace treaties of 1919-20, East Central Europe disintegrated, in effect giving both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia an open invitation to subjugate this huge territory.’…

‘It was not just the authors of the system of the peace treaties of 1919-20 who failed to appreciate what it was they were doing; the blunders were neither fully recognised nor understood during the Second World War. Roosevelt and his advisors were late in grasping the the importance and fatal consequences of Soviet expansion in East Central Europe; Churchill was also late in perceiving the upheaval that was to befall Europe.’

‘But with once historic Europe gone, it was the responsibility of those in power to come up with an effective alternative.’

Szent-Iványi (1977), Budapest: Hungarian Review Books.

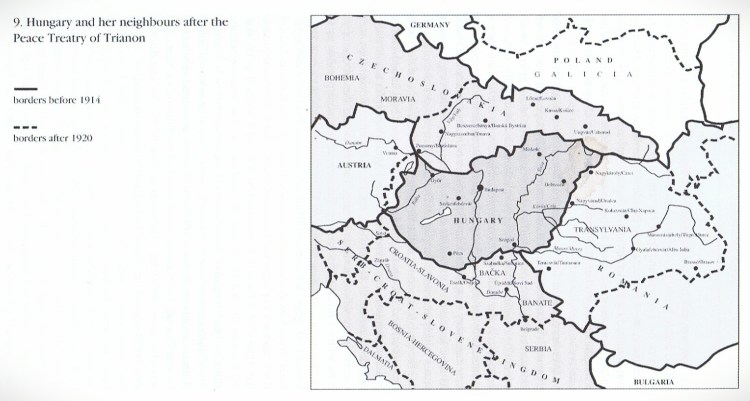

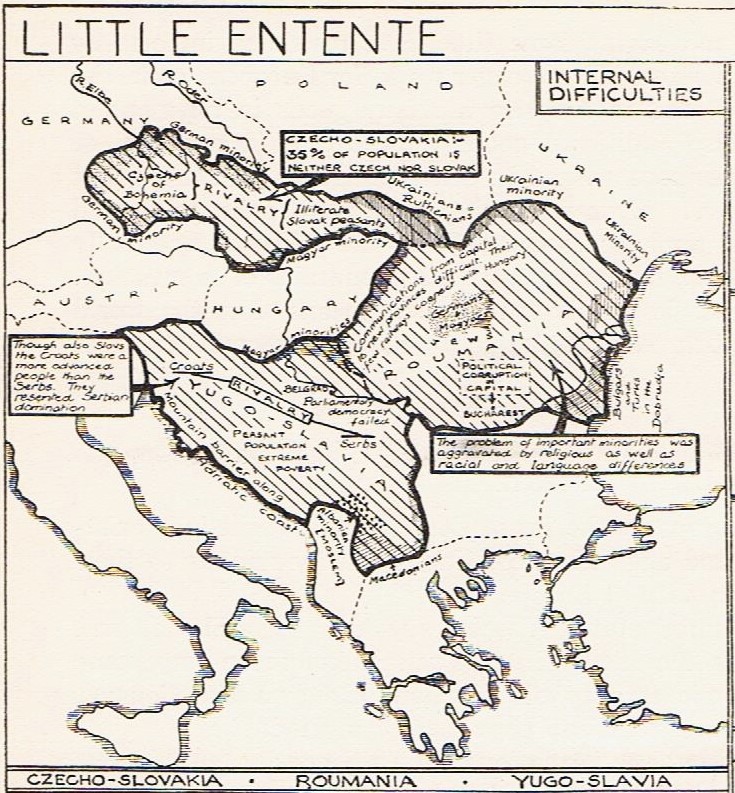

The system of peace treaties (1919-21) shattered the economic and political structure and the unity of the Carpathian-Danubian Basin to its core. After more than a thousand years, Hungary was dismembered: It lost over two-thirds (71.4 percent) of its geographical area, almost two-thirds (63.5 percent) of its population, and more than half its waterworks (55.2 percent). Hungary’s political isolation was complete. The reconstruction of Central Europe at the Peace Conference brought into existence new states, mutually suspicious and aggressive, conditions equally ruinous to their development and dangerous to the stability of Europe. The Little Entente was therefore an important diplomatic development, composed of the ‘artificial’ states of Czecho-Slovakia and Yugo-Slavia, in addition to Romania, was created. The economic activity of the Danubian region was doomed to extinction if these newly formed states remained entirely separate. But for the Hungarians, the alliance seemed to exist for the sole purpose of keeping Hungary in check, guaranteeing almost complete political isolation.

Two important factors brought about the formation of that alliance: The active opposition of Hungary to the Peace Settlement and the fear, common to all three states, that Hungary would resist it. The Magyars felt that they had been unjustly treated. Large groups were under the rule of their former subjects. Hungary’s irredentist aspirations threatened the security of the three Little Entente states. They regarded cooperation to frustrate these dangerous activities as essential, and in 1919 they combined to attack Hungary. Czechoslovakian statesmen were chiefly responsible for building up the alliance, and the initiative came from them because the needs of their new country were great. Like post-Trianon Hungary, Czechoslovakia was a landlocked state, but with longer frontiers not easily defended, and therefore dependent for its security and prosperity on good relations with its neighbours. Their statesmen had no easy task in overcoming the mutual distrust of the three states, let alone their mutual hostility with Hungary. The internal problems were similar in all three states; each government had to deal with groups of minorities, and they were faced with the task of reorganising their agriculture and industries and building up their foreign trade; each government met with difficulties in its attempt to organise an internal administration on democratic lines.

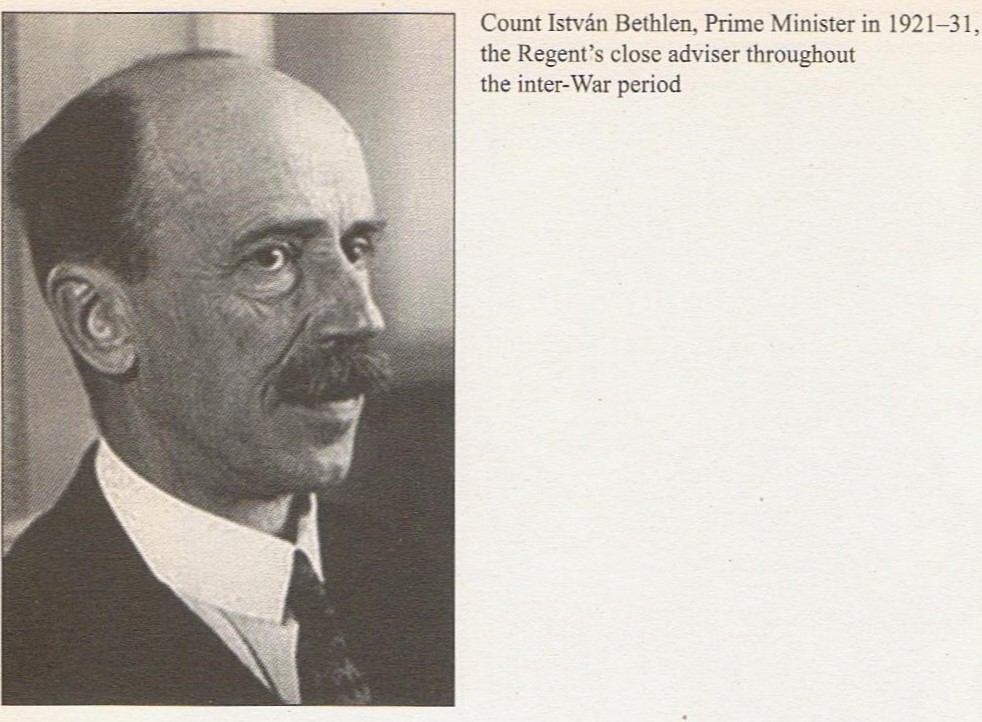

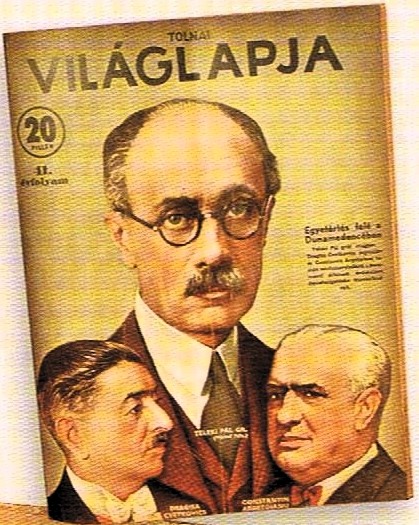

Throughout the twenties, Hungary concentrated its efforts on the peaceful revision of the Treaty of Trianon. At the same time, it made various attempts at breaking the iron ring of the Little Entente, which stifled the country both economically and politically. Its efforts in that direction, however, were constantly frustrated by the stiff resistance of the Little Entente states, fully supported by France. As a first step in the in the course of such attempts, Premier Bethlen and his Foreign Minister, Miklós Banffy attempted to negotiate and even made an approach towards Romania. In August and September 1919, Romanian-Hungarian negotiations were conducted with the participation of Bethlen, Pál Teleki, and Banffy.

The Hungarian negotiators tried to link recognition of Transylvanian secession to the status of the Hungarian state in the Dual Monarchy. The idea of a Romanian-Hungarian personal union under Romanian King Ferdinand was also mooted, as it was several times more in the 1920s. To facilitate the negotiations, the services of the Chief Hunt Master to the King were employed, as he had family ties with Bánffy and Bethlen. Bánffy, in a very Hungarian form of ‘appeasement’ even returned home to Transylvania, now part of the newly enlarged Romania, and became a Romanian citizen. But this was all in vain as the Czechoslovak Premier Benes combined with the French politicians to prevent any improvement in the Trianon terms for Hungary.

Three treaties were concluded as steps in the formation of the Little Entente: in 1920, between Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia; in 1921, between Yugoslavia and Romania, and between Czechoslovakia and Romania. In 1933, the alliance was strengthened, and a permanent council of ministers was established to conduct a common foreign policy which they took to Geneva with them. By cooperating in this way, The Little Entente Powers were able to exert more influence in international affairs. The three countries had been encouraged to come to a mutual understanding by France, who saw the alliance and its adherence to the Peace Treaties as a strong guarantee of support against possible Hungarian or German aggression. The French government supplied them with arms and money. Alliances concluded in 1921, on the one hand between Poland and Romania, providing for mutual assistance if attacked by Russia, and on the other hand between France and Poland, promising mutual support, completed the grouping of the Powers of Central Europe and France.

Revising the Trianon Peace Treaty:

From the signing of the Peace Treaty at Trianon (1920) onwards, Hungarian public opinion, and therefore Hungarian foreign policy, had been dominated by its consequences. Seen as unjust and harmful by the great majority of Hungarians, revising the terms of the treaty became the primary foreign policy issue. In his last plea before the ‘People’s Tribunal’ that condemned him to death in 1946, the former Premier and Foreign Minister Bárdossy (1941-42), confirmed exactly this. In the decade following Trianon, the Hungarian government inaugurated a policy of revision through peaceful means. The government based its hopes on Article 19 of the Covenant of the League of Nations as well as on the declarations contained in the covering letter of President Millerand, both documents admitting the possibility of a peaceful revision of all treaties signed at the Peace Conference of 1919-1920.

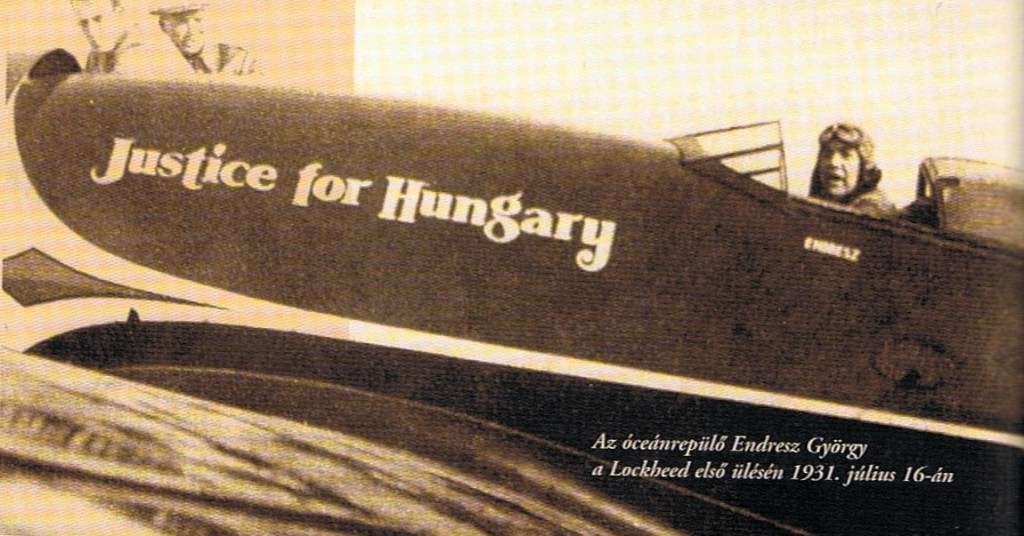

All efforts by Hungary to have the Treaty revised were frustrated by France and Britain and the supporting votes of the Little Entente states which had the majority in the League of Nations. Their vain attempts led many to believe that peaceful attempts at revision were doomed, and by the beginning of the thirties, all hopes of revision had essentially vanished. Yet, at the same time, world events of great economic and political importance gave cause for optimism and a new direction to revisionist hopes and activities. In 1920, war broke out between Poland and Soviet Russia. At the beginning of hostilities, the Red Army made gains and the Polish Army was in retreat. Teleki, the premier at the time, offered Hungarian military help to Poland in return for a French guarantee for the revision of the Treaty. Ammunition, machine guns and other military hardware were on their way to Poland when Czechoslovakia, wanting to ensure a Soviet victory, attempted to block their transit. Yet much of the material had already crossed the territory of Czechoslovakia and arrived in time to be deployed in the Battle of Warsaw. That battle, the ‘Warsaw Miracle’, broke the advance of Tuchatchevsky’s armies and Poland was saved. Many in Poland believed that the Hungarian military hardware had played a decisive role in the outcome of the battle and, by extension, the war. Lenin considered the advance of the Red Army as vital to advancing Bolshevism in Europe. Despite Hungary’s help, France considered all further policies based on cooperation with Hungary as unnecessary. Its pro-Little Entente policy continued as before.

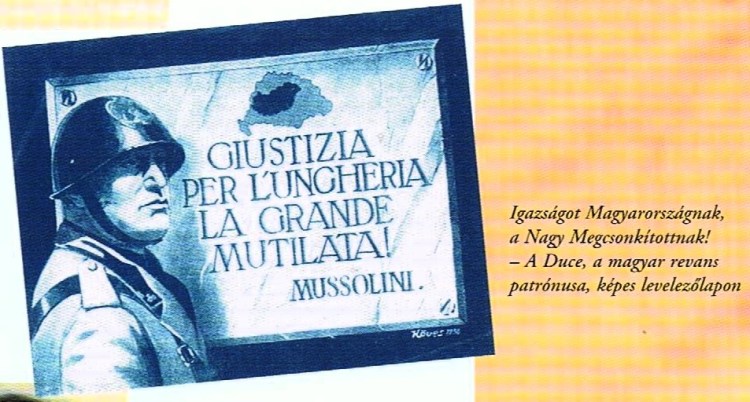

In 1926, commemorating the four hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Mohács in which a joint force of Serbs and Magyars were defeated by a massive Ottoman army, Regent Horthy gave a speech on the battlefield in which he called for a rapprochement between Budapest and Belgrade. The speech was well received in the Serbian press, but the Czechoslovak and Romanian governments rejected rapprochement. The friendly tone of the press was also unlikely to please the Italian government. Mussolini was unhappy with the increasingly warm relations between Hungary and Yugoslavia and took steps to bring Hungary into the Italian orbit. Britain’s attitude to a possible Magyar-Italian rapprochement was quite favourable. The British felt that such a development would help to reduce the influence of France in the League of Nations, where France with the supporting votes of the three Little Entente satellites, and sometimes even with those of Belgium, Greece, and Poland was, most of the time, able to push through decisions. It’s important to remember that at that time the three Great Powers, the USA, the Soviet Union and Germany did not participate in the League’s life and activities. Conversations between the Hungarian Premier, Count István Bethlen and the Italian Foreign Minister, Dino Grandi, as well as with the British Foreign Secretary, Austen Chamberlain, encouraged the Hungarian government to adopt a pro-Italian stance.

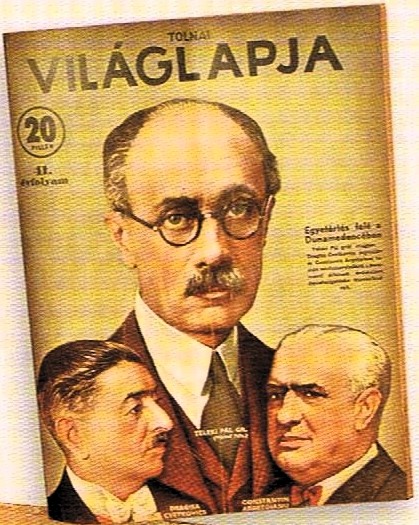

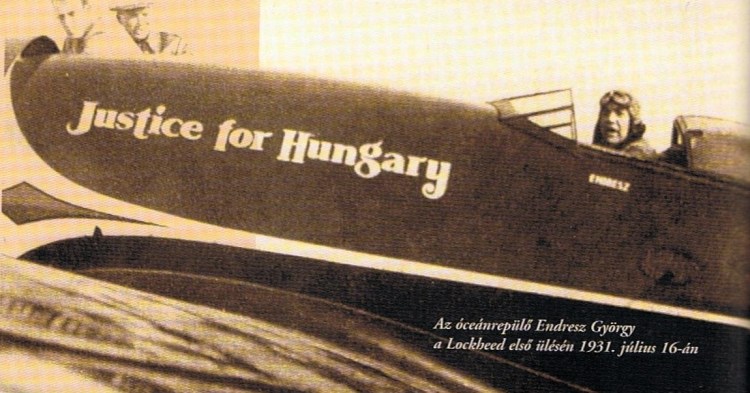

In 1927, one of Britain’s leading newspaper tycoons, Lord Rothermere had a long conversation with Mussolini concerning the political isolation of Hungary after which he published a long article in The Daily News. The article, appearing shortly after the signing of the Treaty of Friendship (5th April 1927) between Italy and Hungary, voiced the opinion that the Treaty of Trianon was unjust and politically unsound and made a call for its revision. Thus, after eight years of almost complete political isolation, Hungary was once more able to play some role on the great international political stage. During the premierships of Pál Teleki and István Bethlen, several problems facing Hungary were resolved. Hungary’s finances were put on a sound basis with the cooperation of the League of Nations (1924-30) and, by cooperating with Britain and Italy, Hungary was able to break out of its political isolation (1926-27).

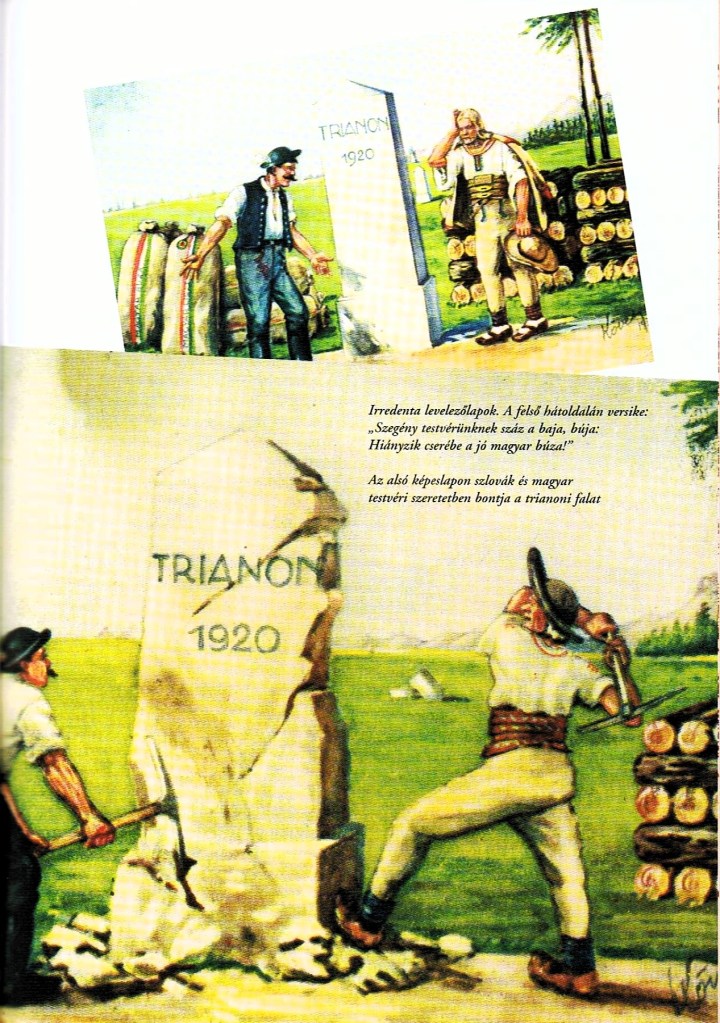

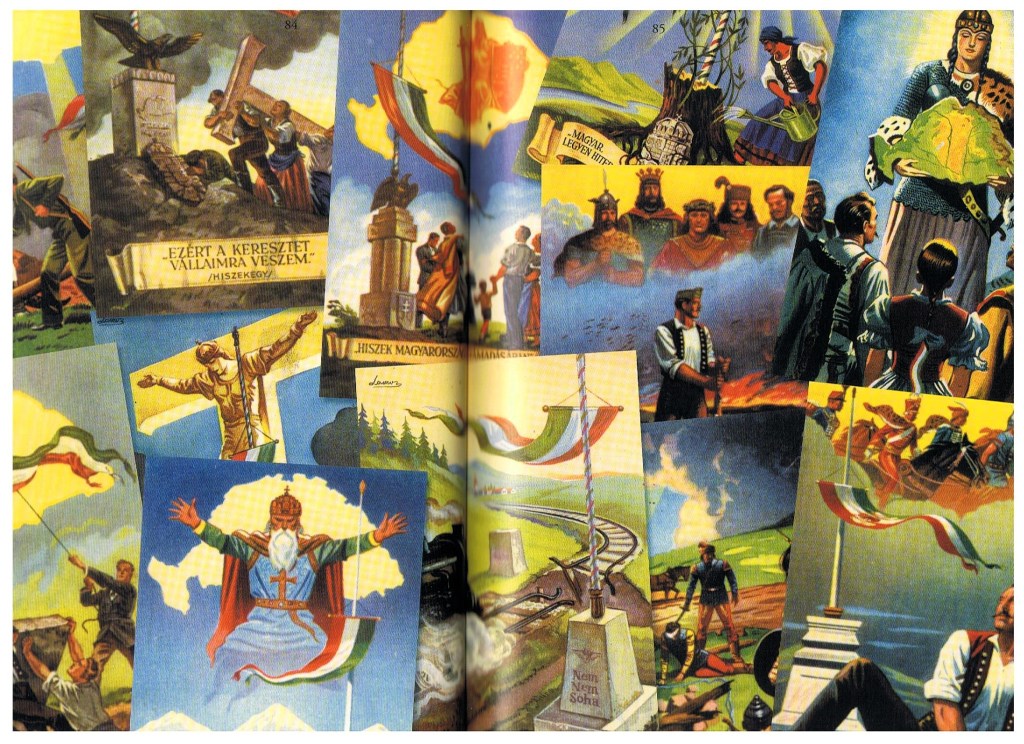

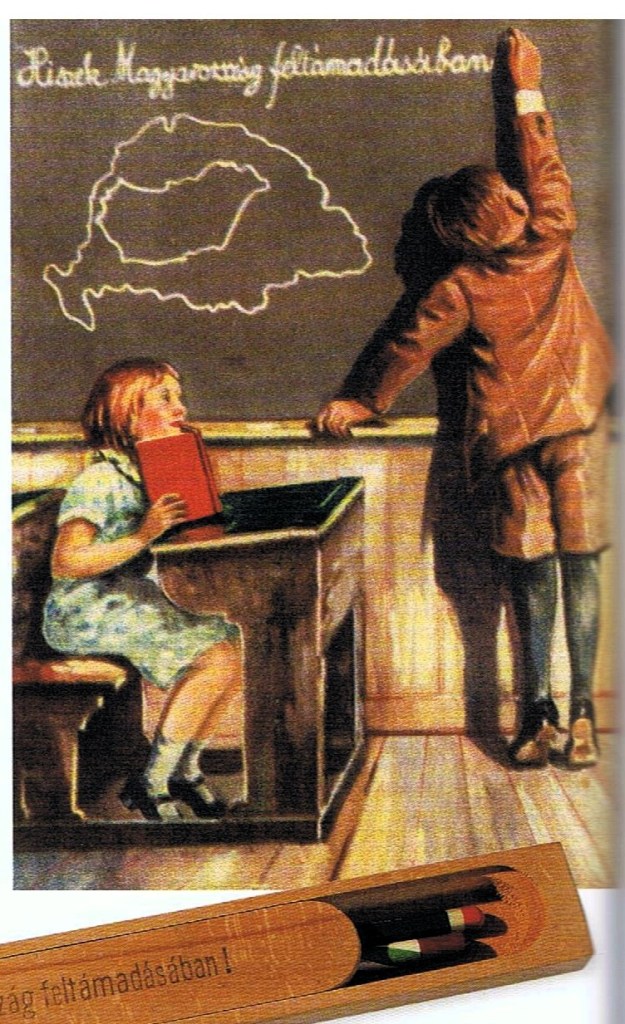

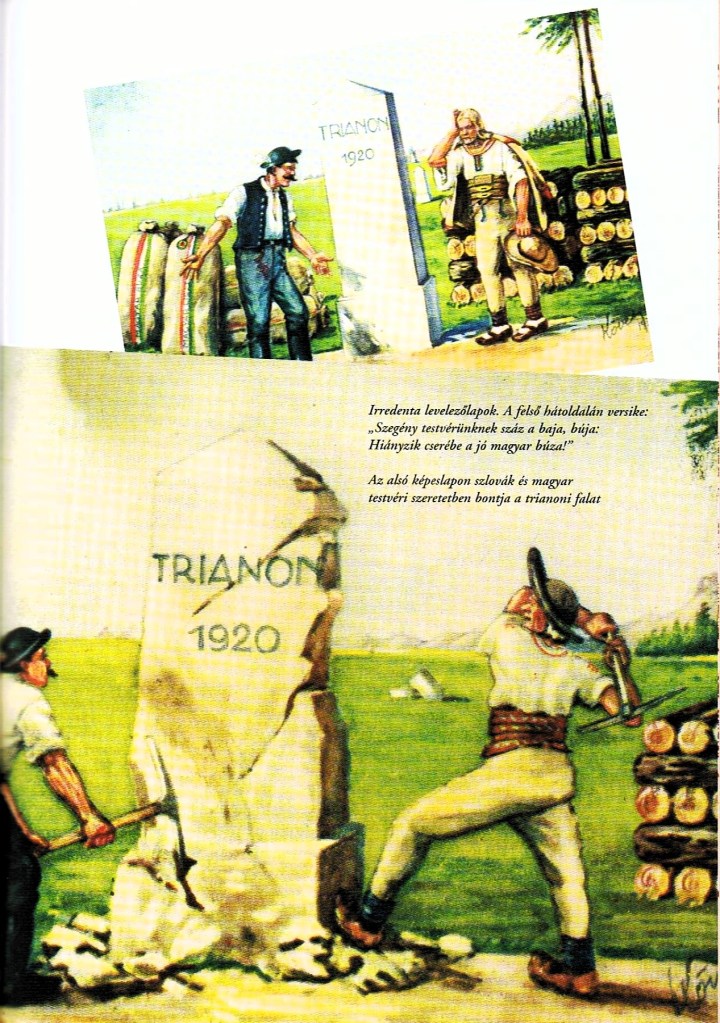

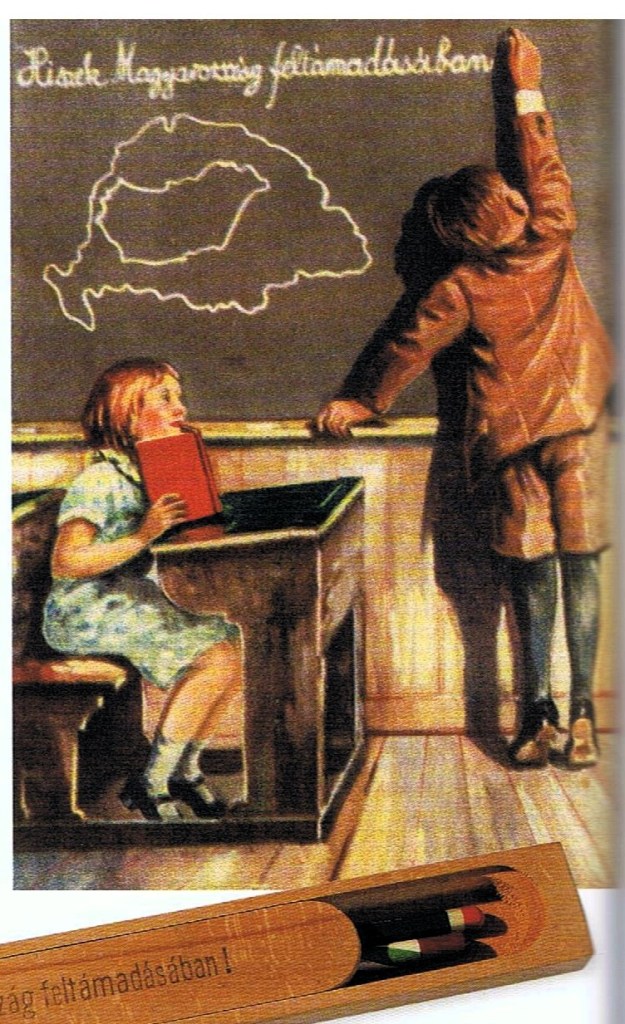

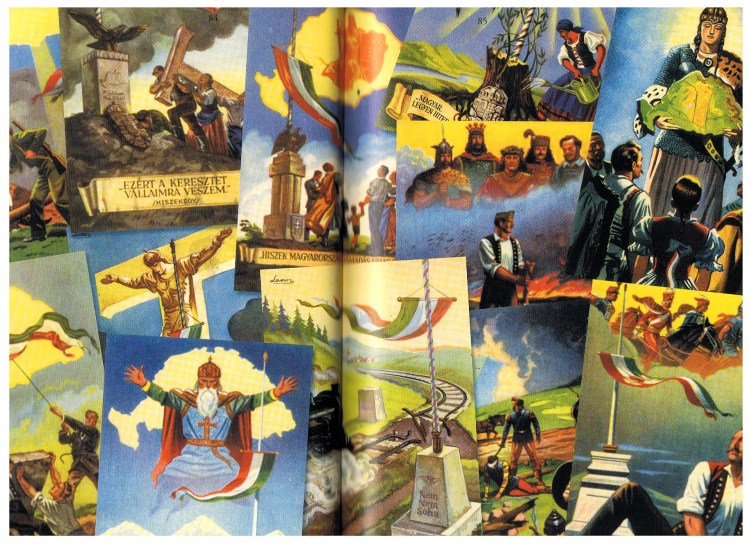

Below, the revisionist dream seems to be realised on the different boxes: Upper Hungary and Subcarpathia, Northern Transylvania, and Bácska depicted as already recaptured. The pencil and pen tip boxes originate from the period following the two Vienna Awards, circa 1940.

By the end of the 1920s, the League of Nations had established itself as a permanent international organisation for the preservation of world peace. Through the Geneva Protocol of 1924, the Powers confirmed their renunciation of war and recognised the compulsory jurisdiction of the Permanent Court of International Justice at the Hague. By the Locarno Pact of 1926, Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, and Italy guaranteed the new frontiers set up in Europe by the Peace Treaties. Britain and Italy undertook to go to the assistance of any state in Western Europe which suffered any violation of this pledge, i.e. to help France or Belgium if it was attacked by Germany. The Kellogg Pact (1928) was a solemn agreement, subscribed to by all the Powers, undertaking to renounce war except in self-defence.

Before the First World War, the Great Powers had exploited the jealousies which existed among the Balkan States to extend their own influence. From about 1929, a movement towards cooperation began between Yugoslavia, Greece, Romania and their former enemy, Turkey. Their object was to settle their own differences so that the Powers would have no excuse for interfering. During the nineteenth century, the Balkan States had shaken off the oppressive rule of the Turks, but it was not until after the war that they began to realise that the ‘new’ Turkey had no desire to threaten their security. In 1930, Greece and Turkey came to an agreement by which they promised to respect their common frontier. This was an important step towards the formation of the Pact of 1934.

The Balkan States had never been united except in their common opposition to Turkey. The territorial changes after the Second Balkan War (1912) left irreconcilable bitterness between Bulgaria and its neighbours, and the new settlement at Neuilly accentuated it. Bulgaria was not prepared to join any pact to guarantee frontiers with which it was completely dissatisfied. There was also continuing rivalry between Italy and Yugoslavia. Italian influence in Albania alienated Yugoslavia and prevented Italy from joining any Balkan alliance. Greek statesmen persisted in advocating for the alliance, which was concluded in Athens in 1934.

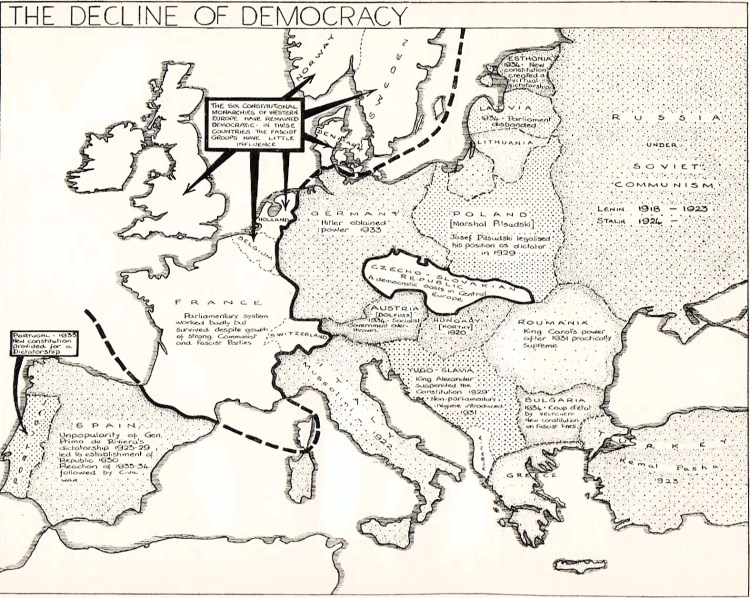

The fall of the two great central European empires, Germany and Austria, and the disruption of Russia by Bolshevism, seemed to augur well for the future of democratic government. After the First World War, democratic governments were established in the new states, whose rulers recognised the wisdom of adopting constitutions modelled on those of the Western Powers. In every European country except Russia, where a new form of government – a Communist dictatorship – was established, the principle of democratic government was accepted. However, the maps below show how soon Fascist parties began to flourish across Europe as they drew strength from the failure of Parliamentary governments to deal with the misery arising from the World Economic Crisis (1929-32).

Dictators came to power in Germany, Austria, Poland, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. Even in France, the Netherlands, and Belgium, Fascism created difficulties for Parliamentary leaders. Only in England, Norway (in the early thirties), Denmark, and Sweden was the influence of the Fascist parties negligible. Czechoslovakia maintained her position with difficulty, surrounded from 1934 by a bloc of Fascist neighbours and countries prepared to ‘appease’ them to maintain a measure of independence. Hungary became one of the latter.

After a critical initial period of great bitterness among the losers, and an apparent consolidation in the more favourable climate of the 1920s, the political and moral foundations of the Paris Peace Settlement proved to be too fragile to survive the effects of the economic crisis beginning in 1929. Economic isolationism bred xenophobia, nationalism and political extremism; the successor states of Austria-Hungary were torn even further apart, creating favourable preconditions in the region for the penetration of Nazi Germany.

Norman Stone (2019) claimed that in the late 1920s, Hungary had been the eye of the hurricane, a period when you could pretend that everything was heading back to 1914. In Budapest, the high aristocracy could show off with grand marriages, and the capital was still putting up interesting buildings, in this period of Art Deco. The recovery period ended in 1931, with the fall of Premier István Bethlen. After ten years he was tired and made misjudgments. Hungary was subject to the international context, and in 1929-30 a great world economic depression started, the second half of the hurricane. American money had financed European recovery. British money had helped as well, but had been lent ‘long’, on the strength of money borrowed ‘short’. The world had gone back to the gold standard, but not to the basics that had made it work in the later nineteenth century; i.e. free trade, including in gold, which the Americans and the French just stored. Germany, Britain, and France clung to gold and subjected their economies to ‘austerity’ to choke back import demand. At the same time, they protected their own industries, so that other countries’ exports suffered. But the banks in central Europe had been lending money on ‘Ponzi Principles’.

In May 1931, some of the largest banks simply failed as foreigners called in loans. International trade fell by two-thirds when the British Cabinet abandoned the Gold Standard in 1931. Every country spent spent less on agricultural imports and this left Hungary vulnerable to economic problems. It lost two-thirds of its wheat exports and half of other agricultural exports. Industrial output fell by a quarter between 1929 and 1933, property auctions were common in the countryside and village shopkeepers went bankrupt. The other was autarky; a self-sufficient economy, with all the tortuous long-way-round attempts to do what was done more successfully elsewhere. Public works, four- and five-year plans, and state boards to buy up surplus produce at guaranteed prices marked the decade (and beyond). This went together with stringent control of foreign exchange: travellers were searched at the borders for Swiss francs and valuables. In Germany, Autarky was the answer, and Hungary depended on it. There were already agreements with Austria and Italy, guaranteeing a quota of agricultural exports at something above the world price, but in 1934 came an agreement with Germany which sent a quarter of Hungary’s exports there. The Germans were stockpiling raw materials and agreed to send industrial goods in return.

The Nazis & Hungarian Revisionism, 1932-1936:

Initially, Nazism did not provoke a hostile reaction in the Hungarian population at large. This was because the dominating idea of public opinion was already one of Revisionism before Hitler came to power in Berlin. Then, from 1933, the Nazis had been seen as successfully breaking the shackles put on Germany by the peace treaties of 1919-1920; many thought that perhaps the restoration of Hungary’s territorial integrity could also be realised with help from a Great Power in its neighbourhood. Later, however, disenchantment with the Nazis grew as a consequence of their expansionist policy in East Central Europe.

Hungary was not supposed to have a large army but re-introduced conscription, and by 1936 the atmosphere was again one of the anticipation of war. To appease Berlin, the half-million Hungarian Germans – Swabians – were allowed collective representation, inevitably of a Nazi tendency. There were warnings: the ever-sensible Bethlen warned against the adoption of Nazi tendencies and pointed out that Hungary was losing its independence. It was also clear that in the trade negotiations, Hungary was being degraded to a mere provider of raw materials; the Germans also refused to pay more in hard currency for agricultural imports, although world prices had now recovered somewhat; and there was nowhere else for Hungarian exports to go. There were also Hungarian imitators of Nazism who emerged when the traditional conservatives lost their predominance. The most sinister of them was Ferenc Szalási, who became a member of the general staff towards the end of the First World War. He believed in uniforms, discipline and the inspirational power of the Nation, a Greater Hungary cleansed of Jews and Communists. He also had a sense of personal destiny matching that of Hitler or Mussolini:

“I have been chosen by a higher Divine authority to redeem the Hungarian people.”

From a speech quoted in Cartledge, The Will to Survive, p.371.

There would be a ‘Hungarist’ state, along Fascist lines, and its badge was the crossed arrows that supposedly represented the original Magyar conquest. This gave the National Socialist party the name ‘Arrow Cross’. It made inroads, not just among the lower middle classes, but also among the working classes, where anti-Semitism could mean combating capitalism. Horthy contemptuously refused office to Szalási at this stage, though he was forced to give way to him when abdicating in 1944. In 1938, he appointed Béla Imrédy, a banker and a man well-known to the British, as premier.

Meanwhile, Hitler’s ever more impudent violations of the Versailles Treaty went unpunished. Not only did Nazi Germany become the most important economic partner of most states in central-eastern Europe, but Hitler was also cheered by the crowds in Vienna as the Anschluss took place, and was accepted as an ally in the revision of the Paris Settlement in Hungarian political circles. In addition, he found forces to work with among the disgruntled minor partners in the Czecho-Slovak and South Slav agglomerates and in Romania; using the pretext of the bulky German minorities in the Czech lands, he exploited the attitude of appeasement among the Western powers at the expense of Czechoslovakia. Central Europe as a whole was both a symbolic and operational base for Hitler’s plan to acquire Lebensraum (‘living space’) for the Germans, as outlined in Mein Kampf; from Berlin, Hungary was viewed as a key partner in this strategy to gain control of the Slav lands to the east and south of the Reich. Most historians of interwar Hungary would agree with the view that the dismantling of ‘historic Hungary’ was the product of ‘centrifugal forces’ rather than the result of a conspiracy between rival nationalities and the Western great powers, though they would agree that the way the process took place was fundamentally influenced by the contingencies of war and the peace that concluded it.

Viewing the successes of Hitler, many Hungarians’ revisionary hopes turned toward Germany. If Germany had been able to shake off the military restrictions imposed on it by the Versailles Treaty, they thought, Hungary could, through close collaboration with Berlin and with the help of the League of Nations, realise her revisionist aspirations. As a result of this shift in public opinion, a closer relationship between Hungary and Germany evolved. There were those in Hungarian political and social circles who were alarmed about the growing collaboration with the Nazi régime in Berlin and what it would mean for Hungarian interests and, in particular, for the independence movement. Hungarian domestic politics also underwent a change. Under the pressure of the growing economic difficulties on the one hand, and of steadily increasing right-wing tendencies on the other, Bethlen resigned in 1931 and was followed as Premier by Count Gyula Károlyi. However, his return did not last long and the following year he yielded his place to General Gömbös, an anti-Semite, proto-fascist and pro-Nazi politician. Unsurprisingly, Gömbös’s premiership, backed by various groups, mainly of Swabian origin, some of them of a clandestine character, saw such ideas and sympathies become more widespread.

Below: Local Hungarians protesting in Temesvár (Timisoara) in Transylvania, March 1919.

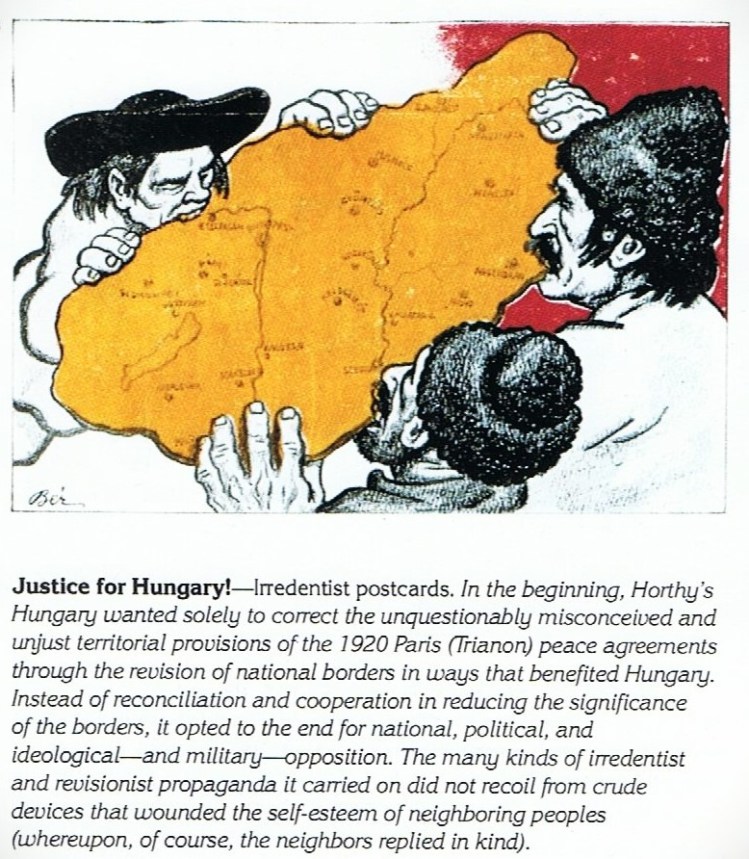

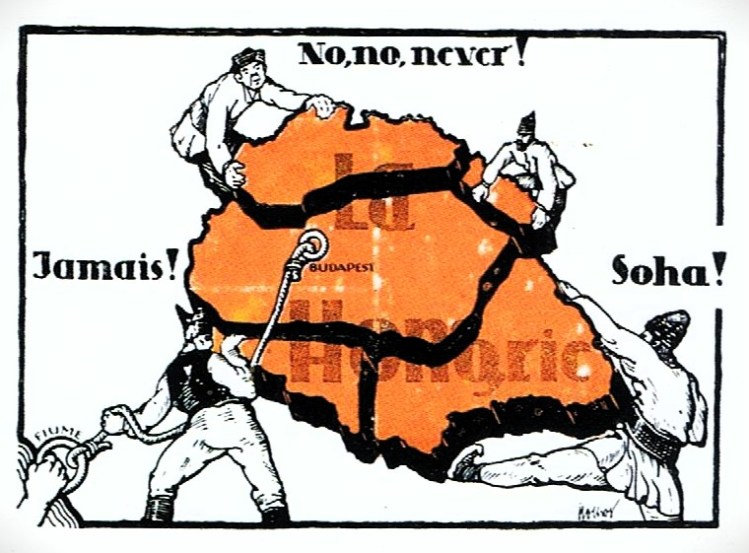

The tragedy of Trianon consists of far more than merely putting the seal on an ‘inevitable’ process, in that Hungarian national consciousness was tailored to the reality that Hungary was a medium-sized nation of twenty million people in which Magyar primacy was not determined by a vulgar, statistical majority or on racial identity, but on historical and political achievement. It was bewildered by being forced within the confines of a small country with a population of eight million. Given that the flaws of the settlement gave some justification to the general spirit of outrage and revenge, as compressed in the slogan ‘No, no, never!’, no political party entertaining any hope of success in Hungary could afford to neglect the issue of revision in its agenda in the 1930s and early 1940s.

Hungarian politics were being overshadowed by Austro-German tendencies. Sympathies with Fascism were coming to the fore, parallel to the rise of Dolfuss in Austria rather than that of Hitler, though by 1932 Hitler was on the rise as well. This was more the ‘spirit of Szeged’ from 1919, however; nationalist, anti-Habsburg, anti-magnate, somewhat anti-Semitic, but not violently so. Horthy made Gömbös promise to leave Bethlen’s supporters alone, as a majority in the lower House, to refrain from attacking Jews and to forget about land reform. Gömbös agreed and famously spoke in parliament to renounce his anti-Semitism. But he was an authoritarian who extended censorship and snooping and stuffed the civil service and the army with his supporters.

Then he approached Mussolini for trade pacts and visited Hitler in 1935. In the same year, he staged elections full of violence and corruption, replacing Bethlen’s men with his own, despite his promises to Horthy, who took alarm at these events. Gömbös made things easier for the Regent by dying of kidney disease in October 1936. By then, with German economic recovery, the great question concerned how to handle Hitler. Germany had vastly more to offer than Italy, whether in trade or territory. Also in 1936, Horthy followed the troop of visitors to Berchtesgaden, saying foolish things and pronouncing that the Führer was “a moderate and wise statesman”. Following Hitler’s remilitarisation of the Rhineland, Horthy announced his approval and also supported Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia.

The most important of the pro-German groups was the General Staff of the Hungarian Honvédség, the Army, which became a state within a state during the tenure of its Chief of Staff, Werth (October 1938-September 1941). Partly in consequence of his Swabian ethnic origins and partly due to his profession as a staff officer, Werth was overtly pro-German in outlook, believing that Revision in Hungary’s favour should be carried out exclusively through cooperation with Germany and that Hungary had to attach her future to German military power. In one of his situation reports of 1939, Werth went so far as to say that Hungary had to stick to Germany durch Dick und Dünn, under all circumstances, even in the inconceivable case of it losing the war. Szent-Iványi later reflected that the appointment of Werth to Chief of Staff was:

‘A great blunder of the Regent and his advisers, … later proved by the activities of Werth and his intimate circle of collaborators, activities which led to Hungary entering the Second World War and putting her last manpower reserves at Hitler’s disposal in 1944 when the outcome of the war could not be considered in doubt. … Werth and his clique formed the the power behind the curtain that caused Hungary to enter the Second World War as well as – indirectly – to Premier Teleki’s tragic death’.

Szent-Iványi (2013 ed.),The Hungarian Independence Movement p 85.

After Werth was relieved from duty, his beliefs and political and military opinions were sustained by a group of staff officers, whose leading spirit became General Dezső László, who had been brought up in Werth’s principles. While Werth himself had claimed “the glory” for forcing Hungary into the War, it was General László who was instrumental in blocking Hungary’s ‘Third Attempt’ at leaving the Axis Camp in October 1944. For this, he was executed in 1947.

Another pro-German ‘group’ consisted of all those Hungarian citizens of German ‘stock’ who, in consequence of the Nazi successes of 1931-1940, believed in the theory of the supremacy of the German race. When the Hungarian Government was forced by Berlin to allow the organisation of an exclusively German federation, the Volksbund, the ultra-pro-German elements were the first to play an important role in the new association and other pro-German activities. Szent-Iványi recalled a conversation on Petöfi Square in July 1940 with Kalmán Breslmayer, the son of the owner of Hungary’s well-known banking enterprises:

‘Breslmayer, buoyed by the German “Blitzkriege” in Poland, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands and France delivered a speech of almost forty minutes. The essence of his speech was that Germany had already conquered Europe; that in a short time England and even Russia would be forced to submit by Hitler; that a great reshaping of the European political map would follow with a new economic-political “order” and finally, that Hungary must attach herself fully to Germany without reservation.‘

Szent-Iványi (2013), p. 86.

The Period of Appeasement, 9 October 1936-11 March 1938:

Alarmed by this increasing Nazi influence, leading moderate circles began exercising pressure on the government to lessen German economic and political power in Hungary. Negotiations followed in Paris and London in the hope of securing financial aid which would reduce Hungary’s reliance on Germany for trade. Among other effects, Hungary tried to have her surplus wheat taken by England and France. These actions proved fruitless since London, on account of the interests of the wheat-producing members of the British Empire, and Paris, in consequence of the protection of her own producers of wheat, took little if any interest in the matter.

A secret Gömbös-Göring agreement was concluded in September 1937 during Gömbös’ visit to Berlin. It included promises by Gömbös that Hungary would introduce a political system along the lines of Nazi Germany. In their discussions, the two men also chose the question of Hungarian revision as their main theme, since Gömbös was willing to make political concessions to Germany to realise the revision of the Peace Treaty of Trianon. In this respect, as Szent-Iványi observed in his note, Gömbős thought and acted no differently from other Hungarian politicians of this era, including even Teleki, in wanting to see the Revision materialise, feeling sure that with Germany’s assistance even full revision might be realised.

Gömbös’s replacement, Kálmán Darányi, gravitated further towards ‘the Axis’, not by slavishly toeing the Nazi line, but through a more coherent policy of ‘all-round appeasement’, approaching the British in vain to gain an understanding. At this point, British ministers also wanted an agreement with Hitler, and would let him remake central-eastern Europe, provided he did so peacefully. Darányi supported the British policy, which gained currency in 1938, following Lord Halifax’s visit to Berlin in November 1937. The Germans indicated that Hungary could recover her lost territories in Czechoslovakia, provided that it helped with Germany’s plans for the destruction of the country. Besides the three million German speakers in western Czechoslovakia, including the Sudetenland, there were another three million Hungarians in Slovakia, who also had many grievances. Austria had already been sucked into Hitler’s orbit and was annexed on 13th March 1938. The Hungarian government was the first to congratulate the Führer. By this time, there was a wave of pro-German sentiment in Hungary, and there were rumours of a right-wing coup in the capital, not least because the officer corps was known to be, in the main, pro-German.

The Period of Appeasement in Hungary covered the period from 9 October 1936, the date of the formation of the first Darányi Cabinet, to 11 March 1938, the date of the formation of both the second Darányi Cabinet and the Austrian Anschluss. The period was the result of the new Hungarian Premier’s overcautious, almost fearful policy which resulted partly from his own timidity and inferiority complex. Darányi was consistently trying to appease, calm, and win over any person with whom he had to thrash out problems of political importance. In such efforts, he was undoubtedly a great success; Darányi was able to create an atmosphere of peace and cooperation, a kind of Pax Romana á la Darányi. He was so rarely attacked in Parliament that some politicians began to worry about his particular brand of peace and cooperation which, in their view, was tending toward a dangerous political dullness and apathy. Darányi had little understanding of foreign policy; his real domain was internal politics and government administration. Yet certain qualities in his personality meant that he became a leading factor in Hungary’s foreign policy, particularly in its relations with the Third Reich. These facets provided a catalyst for the independence and resistance movements. In his widely-known contemporary work, October Fifteenth, The Englishman in Budapest, C. A. Macartney wrote of him:

” Darányi possessed stronger sympathies for the Right Radicals or at any rate less will to oppose them, than either Horthy or Bethlen seems to have suspected in the autumn of 1936. He was nothing approachinmg a Liberal or a Democrat in the western sense of these terms, and so far from being pronounced anti-German that more than once, in after years, he was sent to smooth down Hitler’s plumage when it had been ruffled by other Hungarians. But he was undoubtedly quite innocent of any personal dictatorial ambitions, and there seems to be no reason to doubt that he took office in the knowledge that Horthy expected him to steer Hungary’s course away from the rapids towards which Gömbös had been heading it, and with the sincere intention of doing so. In any case, the impression generally held both inside and outside the country was that it represented an act of resistance, not perhaps defiance, … towards the increasing pressure now being exercised by Germany in both the foreign and domestic fields, …

Macartney, op. cit.

Following the death of General Gömbös and the appointment of Darányi to the premiership, relations between Germany became more strained. But, as Macartney wrote in his October Fifteenth (op.cit.), the new premier could not easily move Hungary away from its close economic and political ties with its longstanding ally and partner, even if he wished to do so:

“Germany’s attitude towards Hungary was of such enormous importance to Hungary’s political life that it is justifiable to give that aspect pride of place in our description of Hungarian history during the period… Furthermore, … the influence of that attitude was, thanks to Hitler’s peculiar method of conducting his foreign relationships, even stronger on Hungary’s internal politics than on her wider foreign policy. … In all these fields, the first year of Darányi’s Minister- presidency forms a distinct chapter of Hungarian history.

“Germany … greeted the news of Darányi’s appointment with an outburst of extreme hostility, which is only comprehensible on the assumption that (it) had attached a … deep importance to the the secret agreement between Gömbös and Göring. It is reported that as soon as he knew that Darányi had been … appointed, the German Minister visited him to ask whather the agreement still hed good. Darányi, who had only just learnt of its existence when going through his predecessor’s most private papers, replied that it did not. From this refusal, … the Germans seem to have drawn conclusions that as to the extent of the change of ‘Richtung’ in Hungary which were far more far-reaching than … its authors warranted. The Germans appear to have believed that a sinister gang of effete aristocrats and rapacious Jews had seized the chance of Gömbös’ illness to intrigue him out of office, for purposes which might even include a Hapsburg restoration.”

Macartney, op. cit.

In May 1937, Regent Horthy’s visit to the King of Italy was reciprocated. While the visit of Miklas had been intended primarily as a courtesy call, which it surpassed, the visit of the King had major political ramifications. First, it was a message of resistance, to demonstrate the strong Magyar-Italian co-operation in the face of Nazi pressure. Furthermore, it was the first time that Hungary, in the course of a military parade, had put on show the military hardware, arms that were prohibited by the Peace Treaties of 1919-20, and arms that were of Italian, not German manufacturing origin. Among these were the small Ansolo tanks delivered by Italy to Hungary in 1937-38. The justifications for this were threefold; Germany had rearmed and was continuing to do so at pace, despite the stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles, so why shouldn’t Hungary, with Italy’s help? Italy had already, unofficially, helped Hungary to modernise its Honvédség (national defence force).

It was important for Darányi to appease the supporters of the late General Gömbös by distributing among them key business and administrative posts. He continued to act very cautiously and did not conduct a great purge, as had been hoped for in conservative circles. Instead, he confined himself to clearing out those pro-Gömbös elements that seemed to be too proactive in certain organisations which were overtly supporting Nazism, for example, the EKSZ (X). The General Staff officers who had been transferred to the Premier’s Office by Gömbös were given the choice of returning to the army or being transferred to the State Civil Administration. In foreign policy, however, there was a continuing stress on improving relations with Italy, both in economic and political terms.

This Italo-Hungarian cooperation had the desired effect in Berlin since the Nazi government felt uneasy at the Hungarian government’s efforts to weaken German influence in the Carpatho-Danubian basin and its neighbouring Balkan states. This concern of the German leaders led to the German Hungarians being invited to Berlin for a meeting in November 1937. Before this took place, Hitler had already achieved a certain freedom of action in central-eastern Europe. In the course of his negotiations with the new Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, Hitler had gained an understanding that Britain would have no objections to modifications in the Paris Peace Settlement of 1919-20, in particular with dispositions concerning the frontiers in the Bohemian Basin, i.e. the frontiers of Czechoslovakia. Many Hungarians began to believe that the break-up of the Trianon system was imminent and that the time had come to start to reclaim lost territories, which could only be achieved with German military support. In the meantime, Hungarian military maneuvers were held along the Tisza River in the vicinity of Szolnok which added further fuel to the fire.

Nevertheless, Hungary grew closer to Germany in the summer of 1938. Horthy, the wartime Admiral, was invited to Kiel, to the launch of a German battle cruiser, where he was asked to participate in the partition of Czechoslovakia. Imrédy had signed a non-aggression pact with the three countries of the Little Entente – Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Poland – who had been the beneficiaries at Trianon, at Bled in Slovenia. Hitler, however, expected Hungary to support his planned attack on Czechoslovakia, but at first, it did not. Instead, he reached an agreement with the British and French at Munich, giving him only a part of what he wanted, but without firing a shot.

At this time, many moderately pro-German Hungarians considered the ‘Bolshevik danger’ to be the greatest menace to Hungary’s independence and integrity; Hungary, they believed, was no match for the Soviet Union. Unlimited cooperation with Germany was seen as the lesser of two evils. Some held that Hungary’s recent troubles had come from powers other than Germany. They argued that the dismemberment of Hungary by the peace treaties of 1919-20 was caused by France and her ‘Little Entente’ states; Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. The dictatorship of Béla Kun, they claimed, was undertaken by men who embraced Communism and its ideas in the Soviet Union and “freemasons of Jewish descent” had played an important role in the dismembering of Austria-Hungary, and that practically all leaders of the Kun’s dictatorship were of Jewish descent. A sizeable minority of anti-Semites became pro-German for no other reason than that they considered the Jews to be ‘enemy number one’. Gentile, religious groups feared Communism, a fear borne of the experiences and lessons drawn from the events of the terror régime of Béla Kun. Goebbels’ propaganda in Hungary utilised this fear to stress the national ‘necessity’ for the country to become a close ‘partner’ of Nazi Germany to escape destruction by Communism, equating this ‘danger’ with the “Jewish-Zionist peril”.

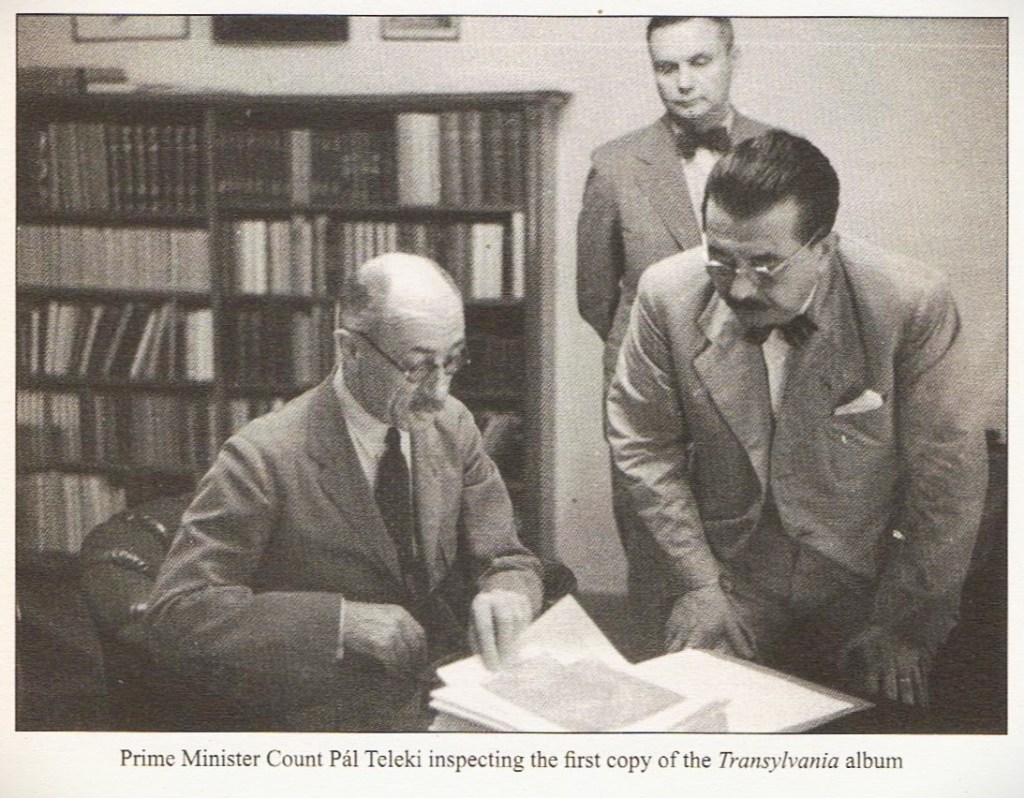

The record and reputation of Horthy’s Hungary was besmirched by its anti-Semitism legislation which enabled the Holocaust of 1944-45, following the German occupation of the country. The first law was passed at the end of 1938, limiting Jewish employment in certain areas. On 4 May 1939 came a second law, to clarify the ‘grey areas’ that the first had created. Also, the quota for Jewish employment was further reduced to six percent. These laws made Imrédy himself look foolish, and he had to resign when journalists dug into his ancestry and found a great-grandmother who had converted. Pál Teleki took office, as he had done in 1920, intending to secure political consolidation by bridling extremism and putting it into the service of conservative nationalist policies. If the auspices had been ambiguous the first time around, now they were distinctly unfavourable. In the last year of increasingly fragile peace in Europe, National Socialism, with its cult of power, the dynamism it radiated, its promise to wipe out ossified social structures, political institutions and cultural habits, and its ideas of racial superiority and Lebensraum, applied to the role of Magyardom in the Danube Basin, exerted an even greater appeal to broad segments of the Hungarian civil servants and the officer corps, the petty bourgeoisie and even the working classes, especially among the younger generation.

Darányi stated several times to Szent-Iványi that he would try to steer a middle course despite the pressure coming from both Left and Right. To understand the Premier’s attitude, we must familiarise ourselves with Hungarian nationalism and adherence to independence as two sides of the same coin. According to Szent-Iványi, true Hungarians had always been nationalistic, irrespective of social or political status. Macartney showed a good understanding of Hungarian national pride when he wrote about the rise of Szálasi’s Hungarism:

“…Szalási – the product of a nation whose ancient State had been dismembered in the name of nationality – always had his eyes fixed on the historic frontiers of his State. As a matter of fact, Szalási’s Hungarism has nothing particularly sensational about it. Any student of Central Europe will recognise in it simply one more of the innumerable Hungarians, from Eötvös and Kossuth, to Jászi, Mihály Károli, Pál Teleki and many others less distinguished, have excogitated for organising the Danube Basin in a way which satisfied their idea of what was due to the past achievements and present virtues of the Magyars.”

Macartney, op.cit.. Vol 1, p.161.

Darányi himself knew that all Hungarians, regardless of their background, held similar views regarding the questions of Revision and independence. While doing his best to uphold the independence of his country, he found nothing objectionable or contradictory to the idea of the revision of the Peace Treaty of Trianon. He was not, as many of his contemporaries believed, anti-German, but simply a Hungarian nationalist; a concept that in his own mind, demanded an independent Hungarian state. But Darányi’s Hungarian character prevented him falling victim to Nazi coaxing and pressure. Despite his rather timid personality, Darányi succeeded in standing firm in difficult situations, like at his meeting with Hitler on 14 October 1938:

“… Hitler, stressing his principle that Aryan peoples should unite against Jewish (and other non-Aryan groups’) aggression, Darányi said that Hungary, not belonging to the Aryan group, could not possibly be interested in such questions. At another point, Hitler made a hint at a possible conflict with Poland in which the case the question of German armies passing through Hungarian territory to reach Poland might arise. Darányi said that in spite of our friendship with Germany, Hungary would never, under any circumstances, turn against Poland or permit a foreign power to attack Poland through Hungarian territory. Hitler’s answer greatly surprised Darányi. The Führer expressed his thanks for having received an open, straightforward answer from the ex-Premier. And smilingly, he added that in no case would the German army need a passage through Hungarian territory: ‘We shall crush Poland in the case of war without any help from any other state or passage given to us by a foreign government.”

Szent-Iványi, op. cit., p. 95, quoting from his own contemporary manuscript.

In Hungary itself, changes in the international scene between 1936 and 1938 also encouraged the growth of fascist organisations. Hitler’s remilitarisation of the Rhineland only evoked consternation and protest, but no action on the part of the Western powers; the German-Italian axis eventually came into existence and rounded off with Japan in the Anti-Comintern Pact; General Franco’s army was gaining the upper hand in the Spanish Civil War. At the same time, Darányi’s foreign minister, Kálmán Kánya, negotiated in vain with his opposite numbers from the Little Entente to secure a non-aggression pact linked to the settlement of the minorities’ problem and the acknowledgment of Hungarian military parity. He also failed to reawaken British interest in Hungary to counter Germany’s growing influence, a move which only served to annoy Hitler who, having decided on action against Austria and Czechoslovakia, assured the Hungarians that he considered their claims against the latter as valid and expected them to cooperate in the execution of his plans.

Darányi had tried to steer a middle course, doing his best to avoid any major changes. He had inherited the pro-Italian policy from Bethlen which mirrored the policy of Anthony Eden, British foreign minister in 1936; with the installation of the Chamberlain government in Britain, non-intervention became the byword for British foreign policy. During his visit to Germany in November 1937, Lord Halifax, replacing Eden, assured Hitler of Britain’s yielding free way to Germany’s position as regarded the revision of the peace treaties in central Europe. From this Hitler concluded that Britain would not put obstacles in the way of the Austrian Anschluss and the incorporation of the Sudetenland into the Reich. Hitler’s meeting with Halifax made the Austrian government very nervous, even though the context for this was already widely known. As the Austrians had already had also been informed about the meeting between Darányi, Kánya and Hitler and other key figures in the Nazi hierarchy, the opening of a Budapest-Vienna dialogue became urgent. Schuschnigg, the Austrian Chancellor and Schmidt drove to Kisbér, a small town close to the Austro-Hungarian frontier on 23rd October 1937 and had talks with their Hungarian hosts, Darányi and Kánya. The Austrians expressed their view that Hitler might shortly start with some action against Austria and the Hungarians promised to clarify everything they could about German plans in connection with Austria.

But Darányi had inherited the government Party from Gömbös in addition to his Cabinet and, in consequence, while putting less emphasis on Germany, he cautiously continued along his chosen ‘independent’ lines. Part of this continuing policy saw Foreign Minister Kánya having talks on the further development of the Rome Protocols with his Austrian and Italian opposite numbers in Vienna. This event was followed by Count Ciano’s visit to Budapest to prepare for the official visit of Regent Horthy to Rome, as well as the official visit of the King of Italy to Budapest. The visit of Regent Horthy took place from 24 to 27 November 1936. Darányi and Kánya accompanied the Regent. The Italian foreign minister was received in Budapest with the ceremony due to a head of state. He was greeted by editorials in the papers, and a central square, the Oktogon, was renamed Mussolini Square, a gesture made in gratitude for Mussolini’s support of Hungarian territorial claims. Ciano, however, never repeated this stand, but in the course of the talks, he emphasised the importance of good relations between Germany and Italy, laying the ground for Italy’s acceptance of the forthcoming annexation of Austria by the Reich, and Italy’s rapprochement with Yugoslavia.

By 1937, Hungary was sending Germany half of its fruit, vegetables, eggs and bacon, and a fifth of exported flour and beef cattle. By 1939, Germany had 53 percent of Hungary’s trade, and on German terms. However, in the short term, this worked. Hungary recovered from the Depression and by 1937 agricultural and industrial production were both above the levels of 1929. Discovery of oil and gas deposits helped. In Veszprém bauxite was also discovered, which gave the metallurgical industries a new edge; already in 1935, the German Air Force needed aluminum, produced on Csepel Island, one of the great industrial centres of Budapest. New industries – electrical, pharmaceutical – developed, and Hungarian industrial goods made a strong showing. Unemployment dwindled. Of course, as a still chiefly agrarian economy, Hungary was a long way behind the Western countries, but it had done better than its neighbours to the east and south as an independent country.

After the Anschluss, 1938-1940 – Diplomatic Roads to Rome & Berlin:

The Anschluss of 12-13 March 1938 took the Hungarian establishment by surprise, the more so because they were expecting Hitler to cede the Burgenland to Hungary, which he was unwilling to do. It was this that alerted Hungary’s political leaders to Hitler’s true plans. He completely absorbed the Burgenland, which (before Trianon) had been a part of Hungary for a century. The Anschluss, more than his earlier declarations and actions, had revised the peace treaty system of 1919-20, but only to the benefit of the German Reich. The Munich Agreement of the 25th September 1938 simply added to the widespread bitterness in Hungary towards Hitler and his régime. That memorable meeting in Munich of the four heads of government did not settle the Revisionist claims of Hungary and the urge to turn away from Nazi Germany only increased. Moreover, although beneficial to Hungary, the First Vienna Award (2 November 1938) did not meet the expectations of Hungarian public opinion as far as their conception of the revision of the Trianon Peace Treaty was concerned. A popular satirical song of the period used the expression, “… becapcsolt a mázsoló…” (“We have been cheated by the Daubster”, i.e. Hitler, the amateur painter).

As a consequence of the Austrian Anschluss, Germany absorbed Austro-Hungarian trade in full and became Hungary’s main trading partner; up to and over ninety percent of Hungarian exports and imports now depended on Germany. Hungarian trade and business were now, in effect, at the mercy of Germany and were closely followed by the expansion of German cultural and political activities. While Italian-fascist influence on Hungary’s economy was not considered a risk to the country’s independence, plans were being made to ensure that Nazi influence on Hungarian political thought and action did not become overly strong. Even the Gömbös régime had sought a solution by which Hungary could utilise German help in its efforts to have the Trianon Treaty revised while keeping the country safe from a Nazi take-over. It was this desire to maintain independence that led to the Rome and Semmering protocols which were considered as the nucleus of cooperation and alliance between Austria, Hungary, Italy and Poland. Hitler’s political methods and schemes were viewed with horror by leading Hungarian circles who began to look to a four-power alliance as a counter-poise to German supremacy in Central Europe.

However, by the following spring, it was too late for Darányi to work out an agreement with the political extremists within Hungary. The German annexation of Austria was hailed as a great success by the followers of Szalási, who were able to exert formidable pressure through propaganda and agitation. This prompted Darányi to appease the Arrow Cross Party and the broader Hungarist Movement. This was too much for the conservatives as well as for the Regent, and Darányi was dismissed from office by Horthy in May 1938. His replacement was Béla Imrédy, who had the reputation of being an outstanding financial expert and a determined Anglophile. Ironically, however, it was under his premiership that Hungary’s commitment to the German side became complete and irreversible. The anti-Jewish legislation prepared under Darányi was pushed into law, establishing a twenty percent quota of the number of ‘persons of the Israelite faith’ allowed to be employed in business and the professions, depriving about fifteen thousand people of jobs for which they were qualified. Liberals and Social Democrats in Parliament protested, together with prominent figures in cultural life including Bártok, Kodály, and Móricz, but the radical Right found the measure too indulgent.

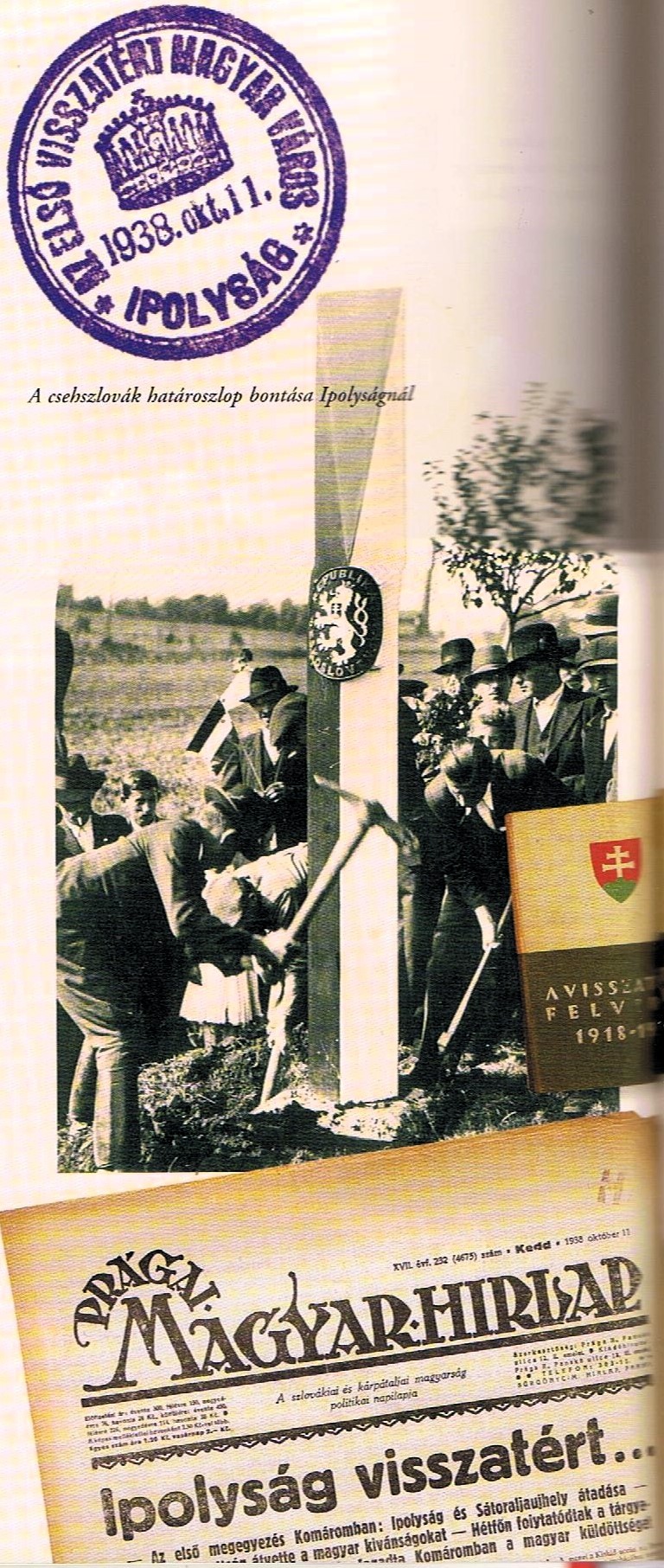

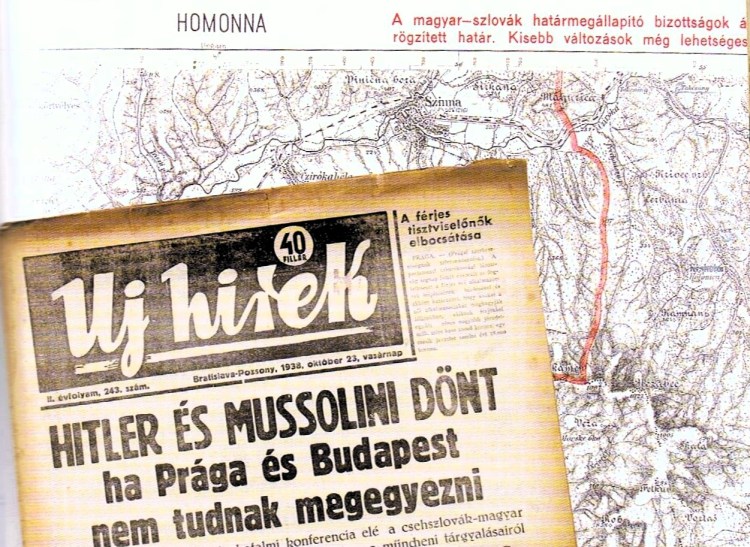

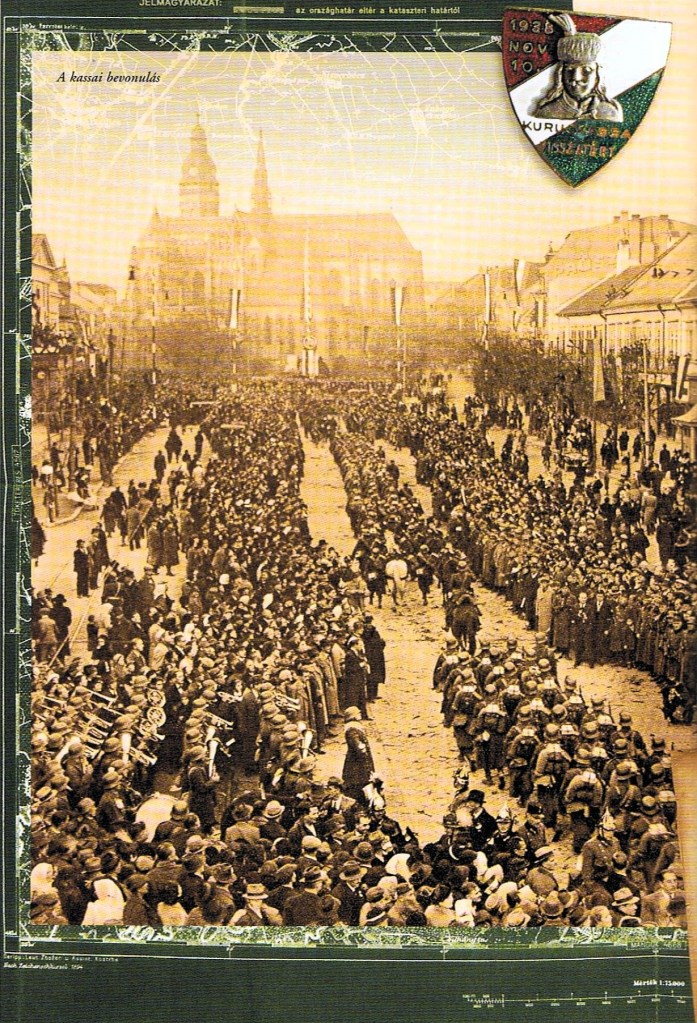

On the 30th of September 1938, there was encouragement for Hungary to deal with her own revisionist claims separately, and a meeting with the Slovaks did occur, fruitlessly, at Komárom. It broke up after four days, and then a Hungarian offer for invasion with German support went to Berlin, for which Hungary offered to join the Anti-Comintern Pact and leave the League of Nations. Hitler and Mussolini agreed to mediate, and in the Belvedere Palace in Vienna on 2nd November the First Vienna Award gave Hungary part of Slovakia, including a strip north of the Danube with a largely Hungarian population and the towns of Kassa, Munkács, and Ungvár in Sub-Carpathia (now part of Ukraine). Horthy rode his white horse again as the territory returned to Hungary, an area of twelve thousand square kilometres, with a million people.

Early in 1939, under a different foreign minister, István Csáky, Hungary joined the Anti-Comintern Pact and left the League. The Germans were then told that Hungary would do something about ‘the Jewish problem’. But by the beginning of 1939, the Hungarian citizenry had realised that it was futile to rely on Hitler’s promises and high-sounding declarations. The consequence of this realisation was a general disillusionment. There were, however, various groups who were pro-German rather than pro-Nazi.

Similarly, fear of Nazi terrorism made Soviet Russia an attractive prospect in the eyes of many. A greater part of Hungarian Jewry considered it to be their only possible saviour from the Nazi peril. So it was fear that opened the doors to both the Nazis and Communists in central-eastern Europe; Nazi domination and terror was followed by Communist rule. Nonetheless, Throughout most of the thirties, unlike elsewhere in Europe where Fascism rose to power, acts of political violence were scarce and insignificant in Hungary. Nazi influence and dominance in Hungary was rejected by practically all social classes. Admiral Horthy, when in intimate circles, liked to label Hitler as “the daubster”. The Hungarian aristocracy, as a rule, hated Nazism almost as much as Hungarians of Jewish ‘stock’. Hungarian intellectuals were also overwhelmingly anti-Nazi.

The ‘moderates’ pointed out that Hungary had experienced time and time again being squeezed between two great powers, both of whom threatened its independence. In addition, the political ideologies of both current Powers were antithetical to those of moderate Hungarians. At the same time, the aims of the Little Entente, backed by France, were to insist on a policy of oppressing Hungary, forcing it to accept its dismemberment by the Trianon Treaty as irrevocable and unalterable. A policy of rapprochement with either Germany or the Soviet Union, therefore, seemed doomed to failure. However, as all signs and events pointed towards a considerable change in European political affairs, such ‘moderates’ put their faith in a ‘wait-and-see’ policy supported by an increase in military strength. In their opinion, any binding declaration in favour of the three international political directions would have been detrimental to true Hungarian interests.

The rejection of collaboration with Germany began with some political leaders, like Bethlen, Teleki and Kereszstes-Fischer as early as 1938, and was continued and developed by those groups which, from 1939, supported the cause of Independence and Revision in tandem; finally, the Hungarian people followed the example of these leaders and rejected Nazi domination. From that moment on it became rather difficult to distinguish between those who were continuing to resist German influence and those who were working for independence.

The growth of fascism naturally worried not only many intellectuals, Jewish professionals, and middle classes, plus the Left, but also the whole of the traditional élite, who feared its social-revolutionary character, and were unhappy about Hitler’s intervention on behalf of the German minority, and had misgivings over the superiority of German arms. For all these reasons, they sought to maintain contacts with the Western democracies. But now they had tasted the first fruits of revisionism, and all Hungarian politicians were willing to subordinate other considerations to the restoration of historic borders, more than ever before. Teleki was no exception to this rule, and while he secretly hoped for the ultimate victory of the Western democracies in the conflict he considered inevitable between them and the fascist dictatorships, in the meantime, he wished to take advantage of the fact that the current domination of the Central European scene by the latter made it possible to redress Hungarian grievances. Historians have rightly blamed this policy as narrow, short-sighted, and ultimately disastrous for the country.

Teleki benefited from the fall of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, when Tiso’s Slovak Fascists, under German pressure, declared independence on 14th March. The next day, Hitler marched into Prague and turned Bohemia and Moravia into a Protectorate of the Reich. That left Sub-Carpathia, the once Hungaro-Ruthene (or Ukrainian) north-eastern corner of Slovakia. Hungarian forces staged a provocation there and occupied twelve thousand square kilometres of thick forest. Many of the local population did not consider themselves Ukrainian, but rather Carpatho-Ruthene, a minority within a minority, and therefore looked to Hungary for protection. This effective revision of the terms of Trianon brought about huge national jubilation across Hungary, which even left-wing poets such as Mihály Babits joined in. Extreme nationalism was now in vogue, and the anti-Jewish laws played into this. By implication, Jewish property could now be ‘confiscated’.

But Teleki’s foreign policy horizons were narrowing. He had scored a distinct success by achieving the long-coveted common border with Poland, thus breaking the encirclement by the Little Entente. But this was just a month after taking office. The occupation of Ruthenia (Carpatho-Ukraine) gave Hungary a territory nearly as large as that acquired under the First Vienna Award, but three-quarters of its population was Ukrainian, so the acquisition had to be justified on strategic and historical grounds, rather than on ethnic ones. The takeover was synchronised with that of Czechoslovakia by Germany on 15th March 1939. Teleki’s initiative to supply Carpatho-Ukraine with broad autonomy came to nothing in the following summer, however, as tensions rose between Hungary and the Slovak satellite state created by Hitler. Revisionist claims by Hungary against Romania were raised at around the same time, which helped Hitler to play his small allies against each other, acting again as an arbiter in central Europe. Nevertheless, this long-hoped-for second step in the ‘augmentation of the country’ earned Teleki and his governing party a great many votes, securing a seventy percent majority for it in parliament, at the elections of 1939. The radical Right also gained twenty percent of the seats and the imprisoned Szalási’s Arrowcross Party was very successful in working-class districts, taking full advantage of the ambiguous policies Teleki pursued regarding ‘augmentation’.

Postscript – Transylvania, 1940-41: ‘The Land of Make-Believe’.

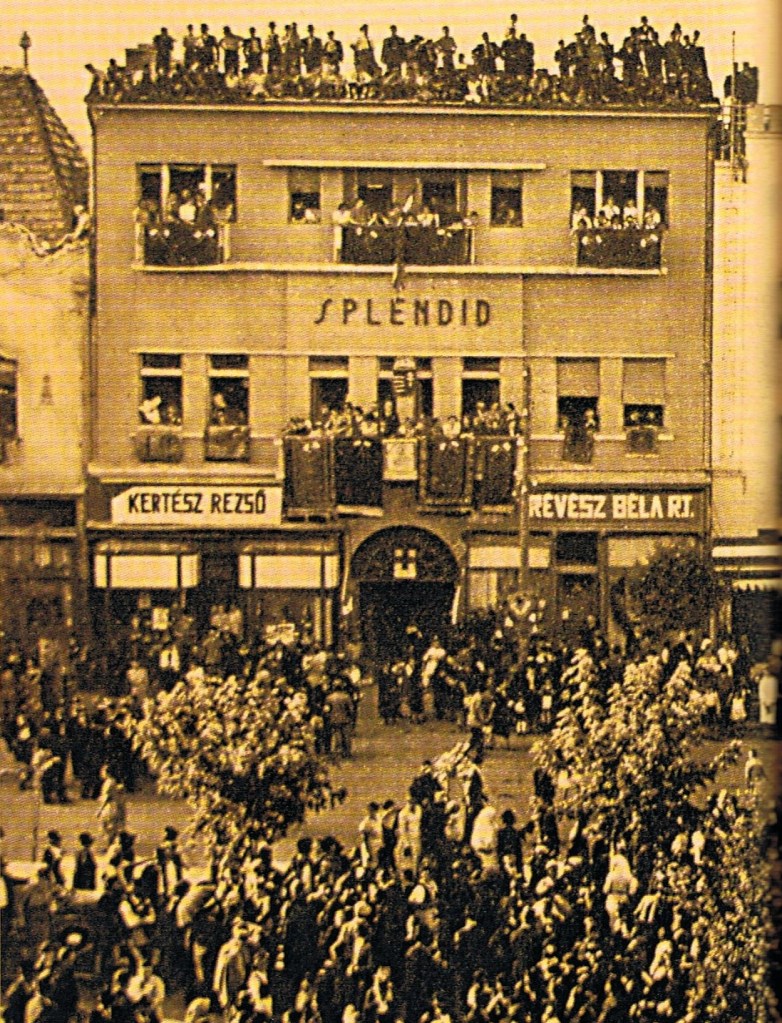

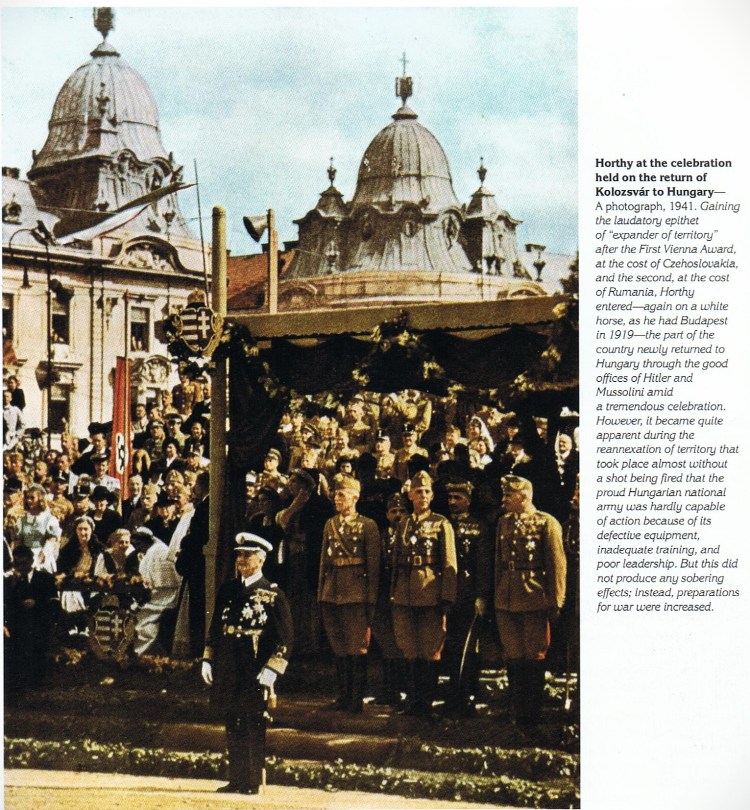

The policy of augmentation led to two further stages of appeasement. The Second Vienna Award (30 August 1940) returned parts of Transylvania, including Kolozsvár (below) to Hungary.

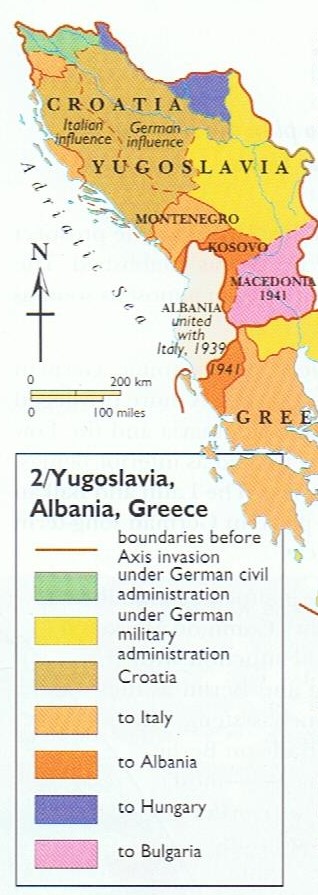

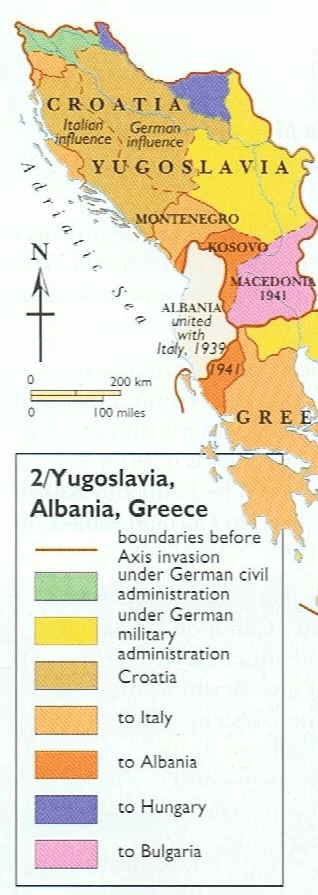

The final expansion of Hungarian territory was the result of the German invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941. On the 2nd, German troops passed through Hungary on their way to Croatia. The following day Teleki shot himself, ashamed of being forced to renege on the recently signed Treaty of Friendship between Yugoslavia and Hungary (I have also referred to this in my previous chapter). Horthy appointed László Bárdossy, the foreign minister, to the premiership. On the 11th of April, Hungary entered the war when its troops followed the Wehrmacht into Yugoslavia and occupied the town of Bácska. Hungarian-speaking Vojvodina returned to Hungary (see the map below), completing its augmentation programme successfully. At the end of June, Hungary declared war on the USSR when the newly returned city of Kassa in Slovakia was bombed by unidentified airplanes. Three years later, Hungary had once more lost these lands, suffering one defeat after another, concluding with occupations first by the Nazis and then by the Soviets.

Given the extent and nature of the cataclysmic events that followed those described here, over at least four years of war (in Hungary’s case), it is easy to ignore the fact that the Nazi movement in Germany was part of a broader European political shift to the extreme right. That is why Germany was able to exploit this development by supporting puppet fascist governments in occupied areas or winning the active collaboration of quasi-fascist or ultra-nationalist régimes. The powerful anti-communism that fuelled the rise of the ‘radical right’ also produced thousands of volunteers from other European states to fight against the ‘Soviet enemy’. At the outset, therefore, there was an ideological commitment to the conflict on their part, as there had been in the Spanish Civil War which immediately preceded it. Germany’s chief ally was Mussolini’s Italy, and in May 1939 the two régimes entered into the so-called Pact of Steel, a military alliance from which Mussolini extracted himself with some difficulty in September 1939. In June 1940 he joined the war on Germany’s side, and the two allies co-operated in the Balkans and North Africa. Although Hitler kept the Barbarossa campaign a secret from his fellow dictator, Mussolini sent forces to help in the east in 1941. So too did Franco and in October 1941 a division of volunteers from the fascist Falange party went to Russia. Other volunteers came from all over Europe, many of them attracted to the élite SS which recruited honourary ‘Aryans’ for combat in their armed divisions.

Under German pressure, much of Europe had fascist or pro-fascist régimes during the war. In Slovakia, the clerical-fascist Slovak People’s Party under Josef Tiso was installed in power in 1939 and was entirely subordinate to Berlin. Some fifty thousand Slovaks served on the eastern front until the nationalists in Slovakia became increasingly disillusioned with Nazism. Other allies in Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria also sent forces to fight on the eastern front, but they too became lukewarm about the German cause as the war went on. Hungary was occupied by the SS in March 1944, and when it tried to leave the Axis to seek an armistice with the Soviets, Horthy was exiled and replaced with an overtly fascist, pro-German government run by Szalási and the Arrow Cross Party. The numbers of non-German volunteers for the eastern front are given on the map above, including significant forces from Hungarian-occupied Yugoslavia and Slovakia, as well as from Hungary itself. These soldiers were not forced to serve in the Waffen SS and the Wehrmacht; their motivations were ideological, or connected to a sense of prestige and power. Hungarians were not pressed into the service of the Reich, whether direct or indirect; their service, and that of the Hungarian State, was a logical conclusion of the populist policies of revisionism and appeasement, both internal and external, developed throughout the interwar years. These were clear choices made by Hungarian politicians, some in reluctant acquiescence, some more willingly.

The populist policies and disastrous choices of the period 1936-44 in Hungarian history have since become shrouded in collective national amnesia which continues to dampen and distort the discourse regarding Hungary’s past. As for the present, it is difficult to see how the policy of ‘appeasement’ of dictators, as defined and redefined by international historians, can be confused as a strategy with genuine peace-making among politicians and diplomats.

Sources for Chapters IV & V:

Irene Richards, et. al (1938): A Sketch-Map History of the Great War and After, London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd.

Száraz Miklós György (2019): Fájó Trianon, Budapest: Scolar Kiadó.

Richard Overy (1996): The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Third Reich, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books Ltd.

István Lázár (1989), An Illustrated History of Hungary, Budapest: Corvina Books.

Mark Almond, András Bereznay, et. al., (1994, 2002), The Times Atlas of European History. London: Harper Collins Publishers.

Andrew Roberts (2009), The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War. Allen Lane/Penguin Books.

Norman Stone (2019), Hungary: A Short History. London: Profile Books.

Laurence Rees (2008), World War Two: Behind Closed Doors; Stalin, The Nazis and The West. London, BBC Books: Ebury/ Random House.

Domokos Szent-Iványi (2013); Gyula Kodolányi & Nóra Szekér, eds. The Hungarian Independence Movement, 1936-46. Budapest: Hungarian Review Books.

Lászlo Kontler (2009), A History of Hungary. Budapest: Atlantisz Publishing House.