Chapter Four: What was/ is Appeasement? – Hungary in The Era of the Two World Wars.

Preface: Present Day ‘appeasers’?

On 8th July 2024, Hungary’s Prime Minister and current President of the European Council paid another visit, on his own initiative, to Vladimir Putin in Moscow. Later the same day, the Kremlin launched yet another missile attack on Eastern Ukraine, killing more than thirty civilians and destroying one of central-eastern Europe’s most renowned specialist children’s hospitals. The following morning, experienced BBC journalists described Orbán’s visit as an act of ‘appeasement’ in the context of these events. How accurate is their application of this term, drawing on its original context of the inter-war period?

Introduction – ‘Horrible Historiography’:

In 1988, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Munich Crisis of 1938, my Professor from Bangor University, my own ‘alma mater’ of a decade earlier, Keith Robbins, published a useful little book on ‘Appeasement’ for the Historical Association. Until then, the fifty-year rule governing access to official papers prevented historians from accessing the British documents of the period, though in 1944 it had been agreed that volumes of selected documents covering the entire inter-war period would appear. Such was the obvious interest in the years immediately leading up to the outbreak of the second war in Europe. These documents were among the first to be published roughly a decade after the events they referred to.

However, it took decades for the series of documents from 1929 onwards to reach the mid-1930s. Indeed, the volume on European affairs from July 1937 to August 1938 did not appear until 1982. Until then, ‘Western’ historians had little documentary knowledge of the problems and issues facing pre-war administrations, forming an essential preliminary to understanding the events of 1938. A particular consequence of publication policy was that it perpetuated an approach to appeasement that was thoroughly Eurocentric and Occidentalist. It could appear that ministers had nothing better to do than to worry about ‘Europe’. As the Cold War became colder in the divided Europe of their day, with Czechoslovakia and Hungary again suffering melancholy fates, Eurocentricity seemed an appropriate response.

However, by the 1950s, decolonisation seemed to be gathering pace, as highlighted by the Suez Crisis of 1956, revealing that if Britain was still a Great Power, it was in eclipse. The crisis had also occasioned an elaborate display of ‘anti-appeasement’ rhetoric which had an appeal across the British party political divide. It was argued that Egypt’s President Nasser was an ambitious, unstable, aggressive dictator. Unless stopped, he would, ‘like Hitler’, develop even more ambitious plans. British politicians claimed to be applying the ‘lessons’ of the 1930s and negatively labelled their opponents as ‘appeasers’.

Against this background, a new generation of British historians, including Keith Robbins, began to wonder whether their world of the 1960s had fresh questions to ask of the policy-makers of the 1930s. The Second World War, which this generation only experienced as infants, did not seem to have settled as much as their parents and teachers appeared to believe. These were also the years when Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State, remarked that Britain had lost its Empire and not yet found a new role. Maybe the 1930s was a crucial decade in Britain’s Foreign Policy, in a sense never hitherto understood, standing halfway between the signing of agreements with Japan, France, and Russia in 1902-07 and the final dissolution of the Empire in the late 1960s. It might be possible to understand appeasement better if it was seen as a crucial episode in a protracted retreat from an untenable ‘world power’ status. Based on such longer-term contextualisation, Appeasement, as a policy, was a necessary instrument. Robbins continued in the first person:

“Since no historian writes in a vacuum, … I was quite convinced, as an undergraduate, that the policy had been morally wrong and politically disastrous. However, I was taught by A. J. P. Taylor, who published his ‘The Origins of the Second World War’ (1961) in the year I graduated. … I was attracted to the topic partly because I had not even been alive during the appeasement years and wanted to approach the entire topic afresh without the emotions which still so clearly troubled an older generation.”

Keith Robbins (1991, 1997) Appeasement. Oxford: Blackwell.

Certainly, many of that generation continued to apply the term ‘Little Hitler’ to any official who seemed ‘too big for their boots’ well into the sixties. In the mid-1960s, Martin Gilbert wrote:

” ‘Munich’ and ‘Appeasement’ have both become words of disapproval and abuse. For nearly thirty years they have been linked together as the twin symbols of British folly. Together they have been defended as if they were inseperable. Yet ‘Munich’ was a policy, dictated by fear and weakness, which Neville Chamberlain devised as a means not of postponing war but, as he personally believed, of making Anglo-German war unnecessary in the future. Appeasement was quite different; it was a policy of constant concessions based on common sense and strength.”

M. Gilbert (1966), The Roots of Appeasement. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

According to Gilbert, appeasement was the guiding philosophy of British foreign policy for ten years. From 1919 to 1929, he wrote, successive British governments sought to influence European affairs toward ameliorating tempers and accepting discussions and negotiations as the best means of ensuring peaceful change. France tended to deny that any change was necessary. Still, British official opinion doubted whether a secure Europe could be based on the Treaties of 1919-20, and had strong hopes of obtaining a serious revision of those aspects that seemed to contain the seeds of future conflict. For ten years those hopes propelled policy forward and important progress was made each year. Appeasement seemed not only morally justifiable, as being clearly preferable to rearmament, conflict and war, but also politically acceptable and diplomatically feasible.

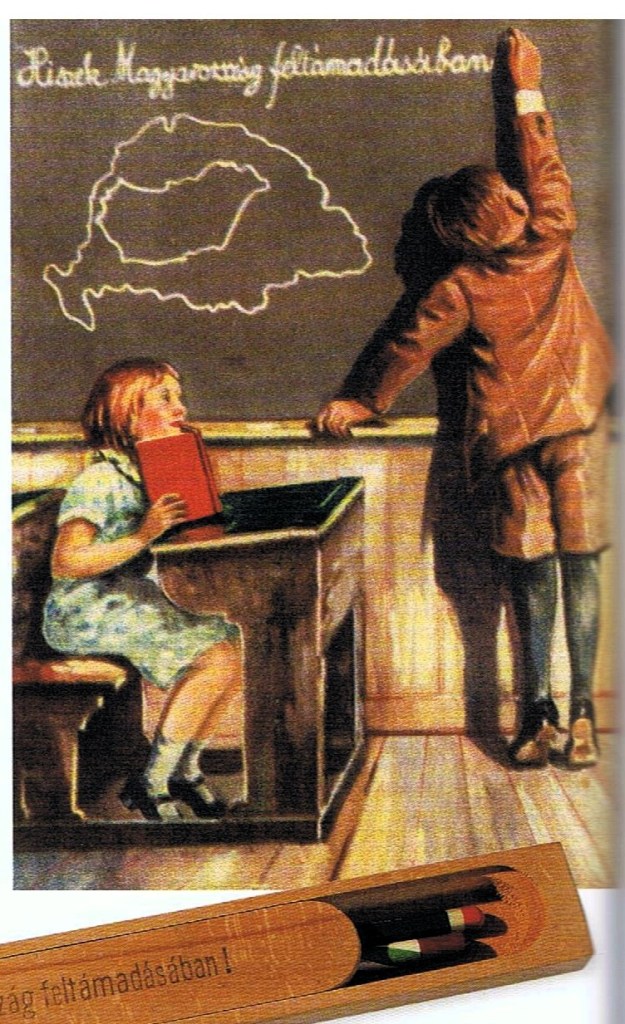

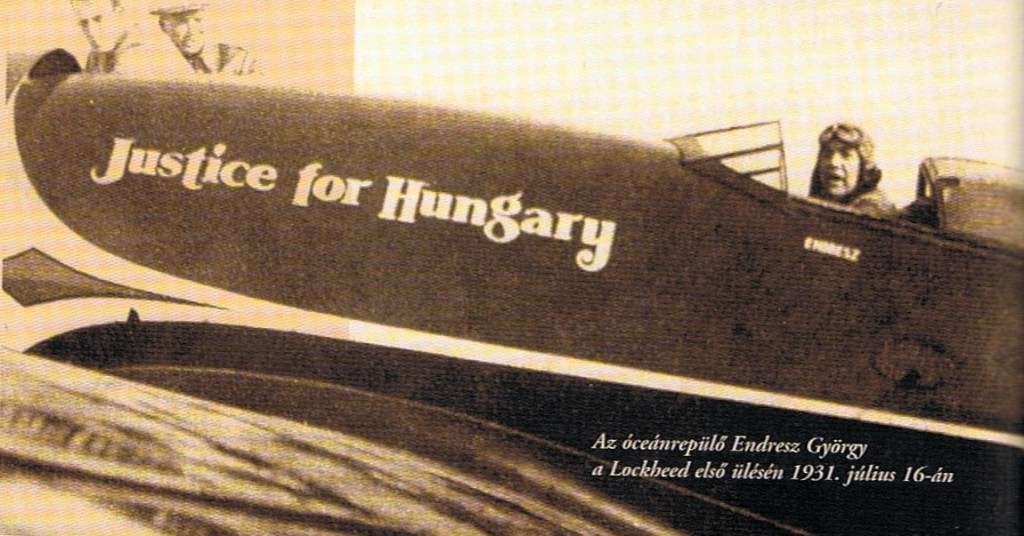

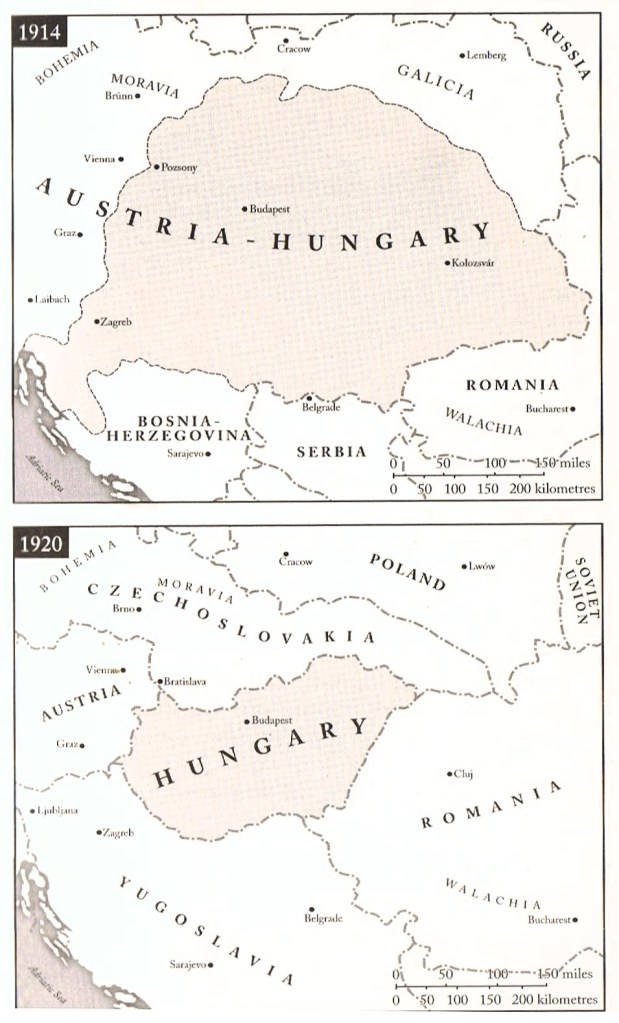

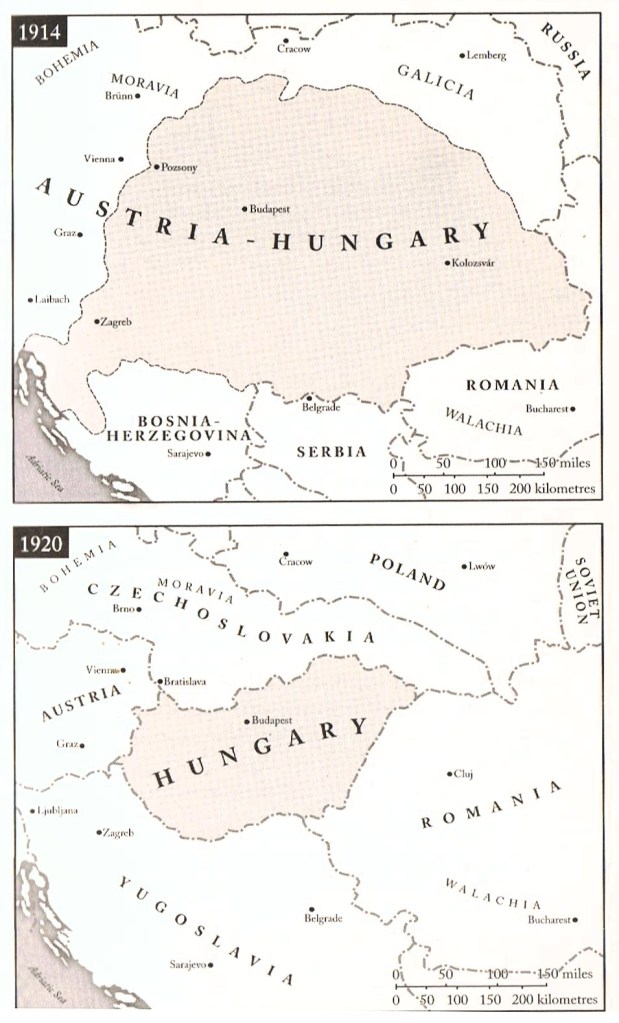

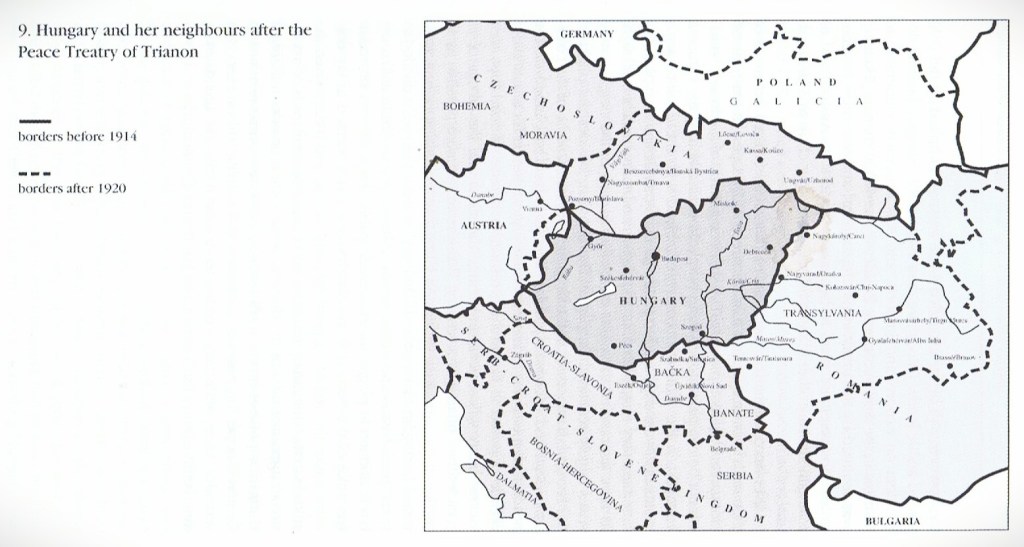

As a guiding policy, appeasement was based on the acceptance of independent nation-states, each in turn based as nearly as possible on Wilson’s principle of self-determination. With the disintegration in 1917-18 of the Russian, Turkish, German and Austro-Hungarian Empires, the final stage had been reached in a process that had begun in Europe during the Napoleonic era – the evolution of a strictly national as opposed to a dynastic or imperial system with defined, strategic frontiers. Post-1918 diplomacy was geared toward securing the final rectification of those frontiers still not conforming to the national principle. Such frontiers were few, most of them the result of Versailles boundaries which had been drawn to the disadvantage of the defeated ‘nations’, Germany, Austria and Hungary. Thus there were German-speaking people outside Germany and Austria, and Magyar-speakers outside Hungary, but contiguous to their frontiers. In addition, Austrians were forbidden union with Germany under Article 80 of the Treaty of Versailles, though this could be altered with the consent of the Council of the League of Nations. Although France was unlikely to make such consent possible, the principle of making territorial adjustments was officially acknowledged.

National inequities other than those of frontiers were also part of the Paris ‘Peace Settlement’, and were equally prone to the egalitarian touch of appeasement. The disarmament of Germany, while France remained, was a German grievance which could be met either by disarming France or allowing Germany to rearm. Both alternatives were considered by British policy-makers, and when the first proved impossible to secure, the second became logically difficult to resist. In pursuing an appeasement policy, the British Government sought to mediate between France and Germany, as an ‘honest broker’. Its aim was to allay mutual suspicions and it depended for its success upon both France and Germany realising that it was a ‘neutral’ policy, designed to provide both with adequate security, under British patronage, and thereby to make rearmament, military alliances, and war-plans unnecessary. The weakness of the policy was that France often felt that it was intended only to weaken it, and Germany that its aim was to keep it weak.

The policy of appeasement, as ‘invented’ in Britain and practised between 1919 and 1929, was, of course, wholly in Britain’s self-interest. It was in no sense intended as an altruistic policy. British policymakers reasoned that the basis of European peace was a flourishing economic situation, unhampered by political bickering, which, would, in turn, promote mutual trade, prosperity and understanding. As Gilbert concluded;

“Only by success in this policy could Britain avoid becoming involved once again in a war rising out of European national ambitions and frustrations: a war which might well prove even more destructive of human life and social order than the 1914-18 war had been. …

“But appeasement was never a coward’s creed. It never signified retreat or surrender from formal pledges. … Appeasement was not only an approach to foreign policy, it was a way of life, a method of human contact and progress.”

Gilbert, loc. cit. pp. 96-97, 177.

But by the mid-1970s, when I was first studying the topic under the tutelage of Professor Robbins, the flood of evidence available after the Public Record Act of 1967 led Gilbert to rethink his earlier views:

“I had not realised the extent to which Neville Chamberlain’s Cabinet were prepared to deceive Parliament. I had not realised the extent to which they chose to ignore the evidence of Hitler’s intention put before them. … And finally, no one had then realised the extent to which, after Munich, far from using the so-called ‘year gained’ to re-arm, Chamberlain had adopted quite a different policy and a quite different attitude, that now the time had come for a real agreement with Hitler which would make massive rearmament unnecessary, and disarmament a possibility. And I document them both from the Cabinet and the Cabinet Committee meetings … and also in Chamberlain’s letters to his sister. …

Keith Robbins was struck by Gilbert’s sudden change of perspective as he wrote his own analysis of the Munich Agreement:

“In retrospect, however, the early 1960s appears as a twilight period. Old preconceptions were still vigorous, though the speed with which Martin Gilbert … altered his emphasis in ‘The Roots of Appeasement’ (1966) from that adopted a few years earlier in ‘The Appeasers’… indicates a changing climate. Even so, it was ‘Munich 1938’ that the publishers supposed that my readers would want… not a general exposition of appeasement.”

Keith Robbins (1991, 1997) Appeasement. Oxford: Blackwell.

On the eve of the publication of Munich 1938, in 1968, the fifty-year rule on access to official documents was changed to a thirty-year one. Many scholars immersed themselves in the official documents this change made available, in addition to newly accessible private papers. This research became truly international, involving British, American, and German scholars. The outcome of these ‘new’ studies was that it became impossible to speak about ‘appeasement’ in simple terms anymore. Instead, historians increasingly referred to a series of policies that were described as forms of appeasement such as ‘economic appeasement’, ‘military appeasement’, ‘political appeasement’, and ‘social appeasement’. It was not easy, however, to determine how they related to each other and which were ‘primary’ and which ‘secondary’. Some argued that appeasement was no longer a term any historian should use since its meaning had become so general. But since it had already become common to speak of appeasement as a policy, it proved impossible to embark on an exhaustive definition. Also, it was evident from the range of sources then available, that the contemporary politicians, diplomats, and military leaders who thought of themselves or others as ‘appeasers’ had referred to the advocacy of a range of policies.

‘Appeasement’ may appear to be a particularly British phenomenon of the twentieth century; a fusion of moral values, political constraints, economic necessities, and military exigencies. Nevertheless, it remains sensible to think of it as a phenomenon of the 1930s and to describe as ‘appeasers’ those who were then responsible for both the formulation and execution of policy. Even if what was being attempted was, in a longer perspective, an elaboration of earlier insights and attitudes, its articulation was novel. After the 1930s, appeasement did not disappear from the lexicon of British foreign policy, as already noted, but eventually, it was called something different. Even in the 1990s, attitudes towards appeasement were affected, in part, by the reconsideration of the significance, for Britain, of the Second World War itself. However, there is a danger in seeing appeasement as something the British invented and controlled. Foreign Policy is always about the complex and constantly changing relations between states. Appeasement, therefore, was both a domestically and an externally generated initiative and response.

Overturning Versailles & Trianon – The Appeasement Debate in the Twenties & Thirties:

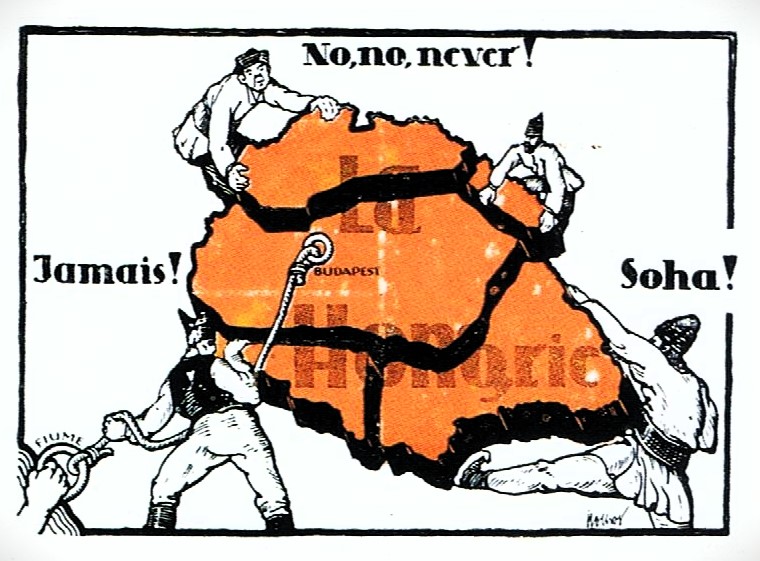

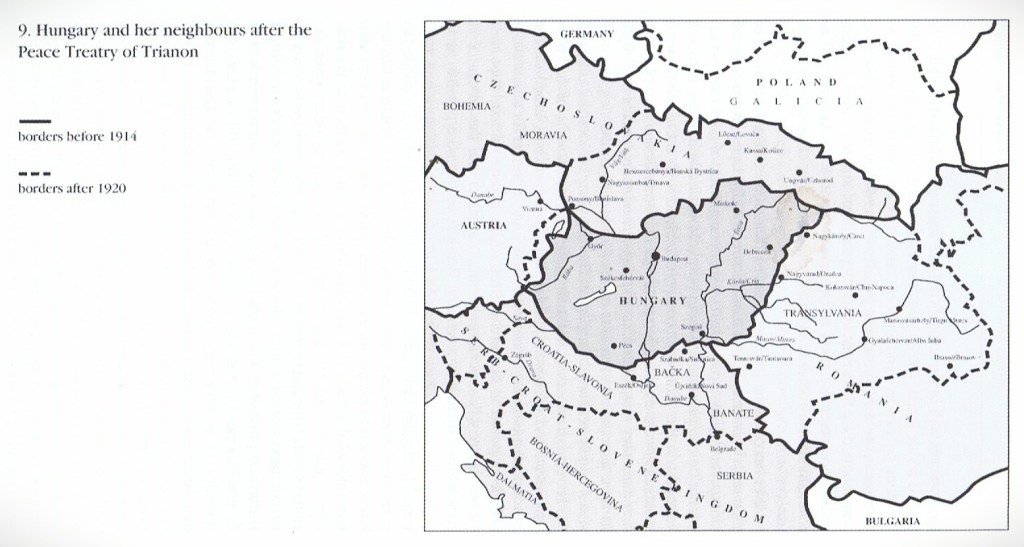

The shadow of the First World War and the Versailles Settlement, including the 1920 Trianon Treaty, concerned with Hungary, hung heavily over inter-war Europe, from east to west. The contemporary economist, John Maynard Keynes’ apparently damning indictments of the ‘Peace Settlement’ helped to develop the policy of appeasement, often misunderstood, as Martin Gilbert suggested later, as the policy of fear of 1937-39. In his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1924 edition), Keynes was scathing in his criticisms of those who aimed to bring about Central Europe’s impoverishment through vengeance. He claimed that the peace treaties included no provisions for economic solidarity among the allies themselves since no arrangement was reached at Paris for restoring the disordered finances of France and Italy, or to adjust the systems, or to adjust the systems of the old order for the new. The Council of Four (Britain, France, Italy and the USA) paid little attention to these issues. Keynes wrote:

‘It is an extraordinary fact that the fundamental economic problem of a Europe starving and disentegrating before their eyes was a question in which it was impossible to arouse the interest of the four. Reparation was their main excursion into the economic field, and they settled it from every point of view except that of the economic future of the states whose destiny they were handling.’

Edited Extract from The Economic Consequences of the Peace, loc. cit.

Instead, Keynes argued for what was later referred to as economic appeasement. He went on:

‘Europe consists of the densest aggregation of population in the world. In relation to other continents, it is not self-sufficient; in particular, it cannot feed itself. The danger confronting us, therefore, is the rapid depression of the standard of life of the European populations to a point that will mean actual starvation for some… Men will not always die quietly. For starvation, which brings to some lethargy and a helpless despair, drives other temperaments to the nervous instability of hysteria and to a mad despair. And these in their distress may overturn the remnants of organisation.’

John Maynard Keynes (1924), The Economic Consequences of the Peace, loc. cit.

For his part, on coming to power, Hitler repeatedly made clear his profound hatred of the Peace Settlement and his deep resentment of Germany’s military inferiority and economic subservience. In 1935, he commented:

“A treaty has been ratified which promised peace but which brought in its wake endless bitterness and oppression.”

Adolph Hitler, 1935.

This view he shared with most of his compatriots, so that, during his first three years in power, he was able to defy and overturn many of the central features of the treaty. That Hitler was able to do so owed a good deal to the changing international circumstances after the economic slump. Other states were absorbed with their own domestic difficulties. The economic crisis reduced the willingness of the Western powers to collaborate and discouraged any risks in foreign policy. Reparations had already been suspended in June 1932, well before Hitler came to power, and by agreement between the powers involved rather than through unilateral action on Germany’s part.

The occupation forces in the Rhineland were withdrawn in 1930, five years ahead of schedule. The willingness and ability of the victor powers to continue to enforce the Treaty were already in question. Hitler made it clear no further reparations would be paid, and in doing so asserted Germany’s economic independence.

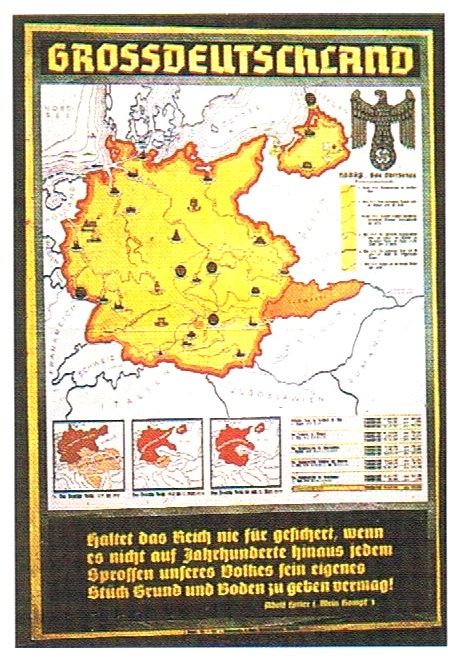

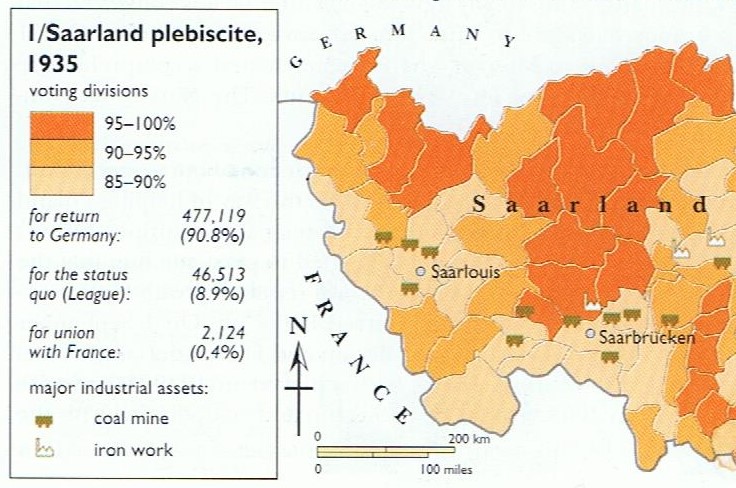

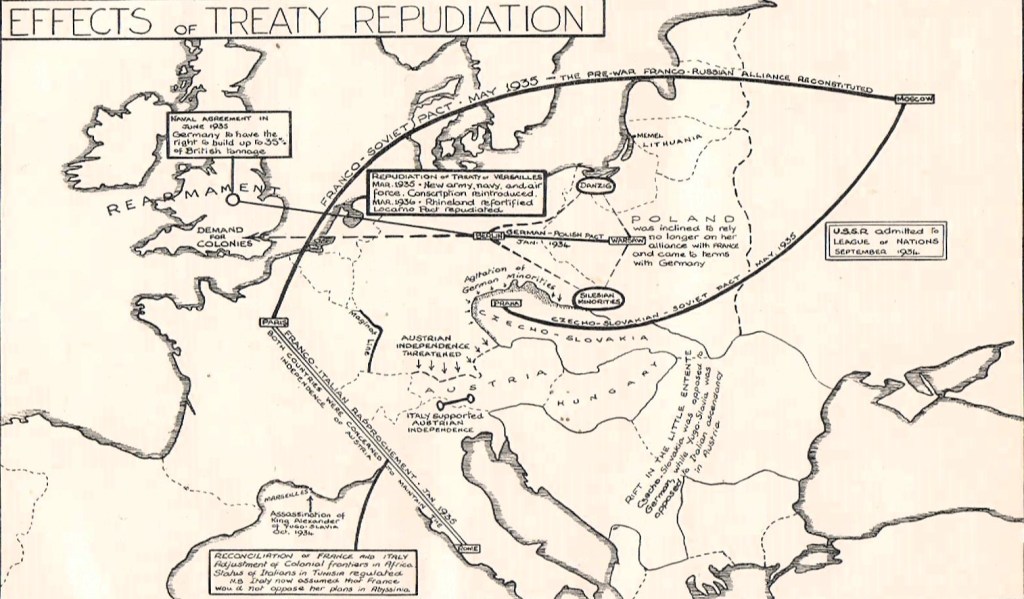

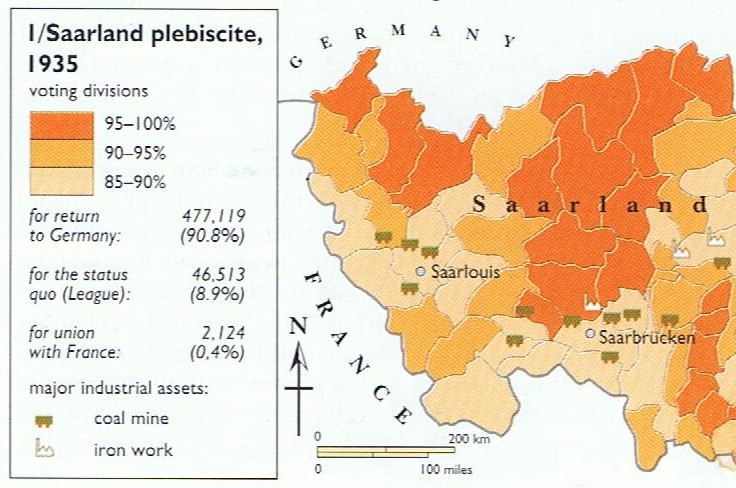

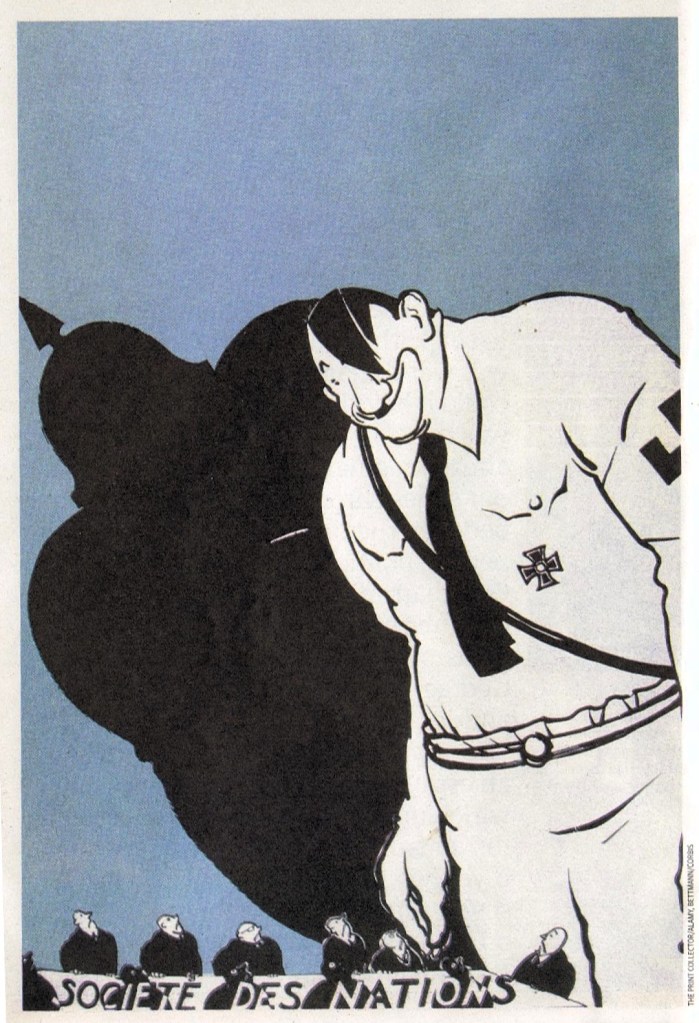

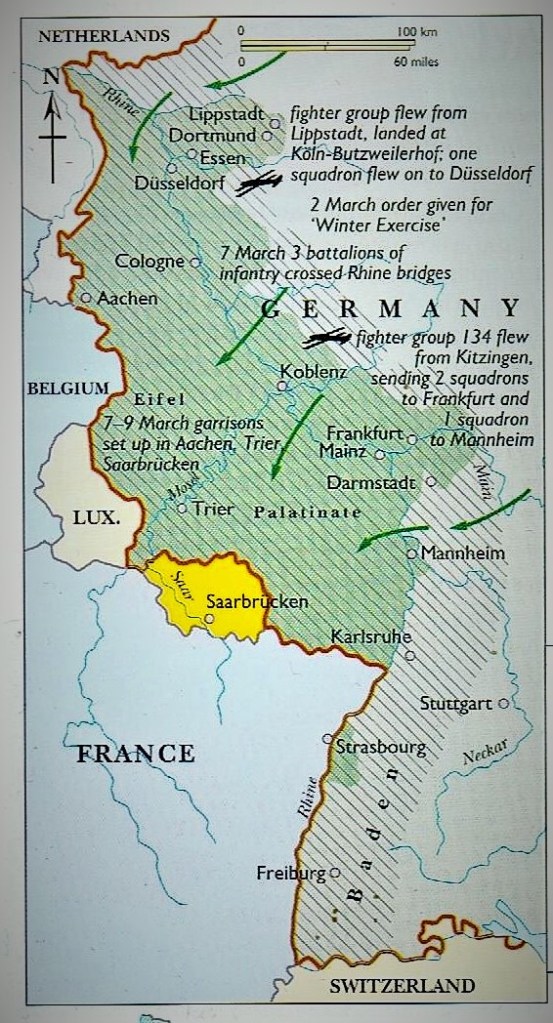

Hitler’s next priority was military independence. Here, too, the process of undermining the disarmament clauses in the Versailles Treaty had begun before Hitler came to power. The armed forces developed aircraft, submarines and tanks in veiled collaborative projects in the Soviet Union, Sweden and the Netherlands. From 1928, three four-year programmes had formed the basis of Hitler’s rearmament from 1933. In addition, in July 1933 the first plans were laid down for a new German airforce. Rearmament in the first two years of the Nazi régime was relatively modest in scope, though it violated the disarmament clauses of Versailles. Hitler and the armed forces proceeded cautiously, partly from fear of foreign intervention, partly from fear of economic consequences of rapid remilitarisation, but mostly because they wanted a planned, step-by-step development of a military infrastructure that had been largely dismantled in 1919-20. By 1935 Hitler was prepared to go further. On 16 March, he formally announced the re-establishment of Germany’s armed forces and German rearmament. Plans were finalised for an army of 700,000 men in thirty-six divisions, and an air force of more than two hundred squadrons. There was little international protest, and three months later Britain signed a Naval Agreement with Germany, limiting total German tonnage to 35% of the Royal Navy, but endorsing Germany’s right to rearm at sea. The same year the territorial settlement of 1919 was altered in Germany’s favour. As agreed in the treaty, a plebiscite was held in the Saar region to determine its future status. Ninety per cent voted for union with Germany (see the map above). A year later, Hitler gambled that he could re-occupy the demilitarised Rhineland with German forces, and on 7 March 1936 troops crossed the Rhine bridges and Germany fully regained her military independence.

The contemporary map above, showing The Effects of Treaty Repudiation, drawn in 1935 (published in 1938), confirms that, by that time, contemporary historians believed that the Peace Settlement had failed completely to satisfy the needs of Europe as a whole. Not only had the defeated state of Germany openly repudiated the restrictive clauses of the Treaty, but the victor states, recognising that the collective security of the League Covenant was uncertain, reverted to pre-war methods of forming alliances, piling up armaments and, in the case of Italy, undertaking military conquests. The main causes of treaty repudiation were, of course, the rise of Nazi Germany and the growth of militant Fascism in Italy, but these, in turn, were fuelled by the widespread sense of injustice which endured in those countries at the Versailles ‘Settlement’.

Not only had the defeated state of Germany openly repudiated the restrictive clauses of the Treaty, but the victor states, recognising that the collective security of the League Covenant was uncertain, reverted to pre-war methods of forming alliances and piling up armaments. Two countries, Italy and Japan, had already undertaken military conquests in defiance of solemn treaty promises. But the rapprochement of France and Russia also had a role to play and forty years after Imperial Russia and France came together in their Entente, Soviet Russia and the French Republic, despite their polar opposite constitutions, came together in a new alliance in 1934. Once more, Germany found itself ‘encircled’ by the Western Powers and Russia. France, ever vigilant to guard its security and protect its borders, constructed a strong line of fortifications along its eastern frontier (the Maginot Line).

Britain announced plans in 1937 for rearmament on a scale to make it the strongest Power in Europe, if not, through its empire, the world. The USSR postponed the completion of its second Five Year Plan to concentrate on the manufacture of munitions. The Fascist leaders of Italy and Germany not only increased their armaments but also began to encourage in the minds of their people the idea that war was necessary, inevitable and splendid. One of the most disturbing features of pre-World War One Europe was the Anglo-German rivalry in naval power, and over colonial territory had reappeared. This, fundamentally, was what led to the development of the policy of appeasement by the Baldwin-Chamberlain Cabinet from 1936 to 1939. Writing in 1961, renowned historian A L Rowse condemned both Baldwin and Chamberlain for their development of the policy:

“But where Baldwin’s were sins of omission, Chamberlain’s were sins of deliberate commission. He really meant to come to terms with Hitler, to make concession after concession to the man to buy an agreement. Apart from the immorality of coming to terms with a criminal, it was always sheer nonsense; for no agreement was possible except through submission to Nazi Germany’s domination of Europe and, with her allies and their joint conquests, of the world … “

“Here (in Czechoslovakia) was an intense strain in the centre of Europe which, if it was not to lead from bad to worse, could only be relieved by a concession. There, in a sentence, is the whole psychological misconception. It is no use making concessions to a blackmailer or an aggressor; he will only ask for more. They were all taken back by Hitler’s march on Prague in March 1939, after the swag he had got, with their aid, at Munich. … And anyhow, what are political leaders for? Do we employ them to fall for the enemies of their country, to put across to us the lies they are such fools as to believe?… the proper function of political leaders is precisely not to be taken in, but to warn us.”

Chamberlain knew no history … had no conception of the elementary necessity of keeping the balance of power on one side; no conception of the Grand Alliance, or of its being the only way to contain Hitler and keep Europe safe. …

A. L. Rowse (1961), All Souls and Appeasement, London: Macmillan.

Rowse argued that the total upshot of the appeasers’ efforts was to aid Nazi Germany to achieve a position of brutal ascendancy. This became a threat to everyone else’s security, and only a war could end. This had the very result of letting the Russians into the centre of Europe which the appeasers… wished to prevent. The primary responsibility was all along that of the Germans, the people in the strongest position in Europe, the keystone of the whole European system, but who never knew how to behave, whether up or down, in the ascendant arrogant and brutal, in defeat base and grovelling. The appeasers had no real conception of Germany’s character or ‘malign record’ in modern history. Trevelyan argued that dictatorship and democracy must live side by side in peace, and the English would do well to remember that the Nazi form of government is in large measure the outcome of Allied injustice at Versailles in 1919-20, and the egregious folly of the ‘war guilt’ clause, which acted, as might have been foreseen, as a challenge to the Germans to prove that their Government was not to blame at all.

Throughout the interwar period, the appeasement policy had a coherent intellectual foundation with a high moral tone. Still, the aggressive expansionist policies of Mussolini in Abyssinia and Hitler in Central Europe exposed the absence of force to substantiate its principles. By 1937 there was a bitter ideological debate on appeasement, reflected in the historian G. M. Trevelyan’s letter to The Times (12 August ’37). The following year the policy soured, but not before substantial British and Dominion support for the ‘resolution’ of the Czechoslovak crisis at Munich. The bitterness of comments from France and Czechoslovakia also reflects the continental feeling that Britain’s geography enabled her to see Europe from too detached and moralistic a viewpoint; given France’s internal weaknesses, and the emergence of the Czechoslovak state in 1918 when Germany was weak, these arguments may have less weight in retrospect.

Rearmament, Remilitarisation & Bloodless Conquests 1935-40:

Keith Robbins believed that Hitler was singularly fortunate that the Disarmament Conference was taking place when he came to power. No British government, given public sentiments, could have been seen to scupper it. The German Chancellor could continue the less and less clandestine expansion of the Wehrmacht, which had begun much more modestly before he came to power. Had there been no conference, there might have been a different response from Western powers. Although Hitler did not announce German rearmament until March 1935, it was no secret in the years before. In the first two years of his régime, he had achieved by unilateral action what his predecessors had failed to achieve by negotiation. Some British Foreign Office officials still advised ministers that Germany might be willing to pay a diplomatic price for the international legalisation of this action, but that proved optimistic.

Hitler, on the other hand, could now threaten the use of force as an ingredient in a wider campaign to release Germany from other enduring aspects of the Versailles Treaty. The outlook, according to the British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, was deplorable. Before Hitler acceded to power, the Germans had known that Britain no longer favoured trying to enforce the armaments limitations of Versailles. Their behaviour had revived anxieties about ‘German militarism’. Few members of his government had close relations with their French counterparts at the beginning of the decade but in the new climate of the mid-thirties, greater Franco-British intimacy was desirable. Security remained the major French concern and British ministers were left in no doubt that Britain too would have to commit itself to some specific steps if France was to formally acquiesce to German rearmament. What was under discussion was a British Scheme for Germany to return to the League of Nations with an agreed limitation of German armed forces alongside an eastern pact, a Danubian pact and an air pact, all designed to reassure the French.

Ten days before Sir John Simon’s visit to Berlin came Hitler’s announcement of the reintroduction of conscription and the creation of an army of half a million men. There was a British note of protest, and MacDonald and Simon met their French and Italian counterparts at Stresa. A ‘front’ seemed to be consolidating, motivated by a common anxiety about German intentions. The subsequent British action, however, seemed hardly helpful to such a development, and the inclusion of Mussolini, who was worried about Austria and Hungary, meant that the front could hardly be classified as a grouping of democratic states confronting fascism. That substantial section of British opinion which wanted foreign associations to be limited to the ideologically acceptable wasn’t best pleased with the company MacDonald was keeping.

Moreover, in the meantime, Simon and Eden went ahead with their visit to Berlin, though to no immediate result. Three months later, however, the Anglo-German naval agreement was signed, displeasing the French greatly, both because they were not consulted in advance and because it sanctioned a much larger German navy than was permitted by Versailles. On the other hand, there was disquiet about even a loose association which might convey the impression that Germany was about to be ‘encircled’. Although the sentiment had begun on the left, it was now fairly generally argued that even the semblance of a return to the alliance divisions of pre-1914 Europe would be likely to increase tension rather than promote stability.

French ministers, however, were less apprehensive on this score. Attaching great importance to the Italian connection, they were willing to accept the possibility of Italian expansion into Ethiopia, provided that French interests were safeguarded. Mussolini may have thought that the British would be similarly understanding if he offered them something concerning the Italian fleet in the Mediterranean, but that was unlikely. When the Ethiopian crisis erupted, Britain had a new Prime Minister and a new Foreign Secretary: Stanley Baldwin and Samuel Hoare (pictured below). MacDonald had always had a keen interest in Foreign affairs. Baldwin, however, did not share this interest and was not tempted to intervene if it could be avoided. Added to this, Sir Robert Vansittart, Permanent Under Secretary at the Foreign Office, did not favour sanctions against Italy and drew up plans for the partition of Ethiopia. When the final scheme was being discussed with Laval, the French Foreign minister, details leaked out, and there was a political storm. Hoare had to resign; Vansittart did not, though some were critical of his role. Following Mussolini’s ‘triumph’ in Ethiopia, there arose a great danger that an ideological axis between Rome and Berlin would be formed, where none had previously existed.

As a regular visitor to Abyssinia from 1930 to 1935, the journalist and author Evelyn Waugh wrote a piece for the Daily Mail reporting on how the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, had attempted to win the support of the League of Nations and…

… transmitted to his simpler subjects the assertion that England and France were coming to fight against Italy so that even those who had least love of Abyssinian rule feared to declare themselves against what seemed be the stronger side. … The Italians, in the face of sanctions… felt their national honour to be challenged and their entire national resources committed to what, in its inception, was a minor colonial operation of the kind constantly performed in the recent past by every great power in the world. No one can doubt that an immense amount of avoidable suffering had been caused and that the ultimate consequences may be of worldwide effect.’

Edited extract from Waugh’s Abyssinia. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

On the evening of 9th May, from the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia, the duce spoke to a huge crowd in the square below: “Italy at last has her empire,” he declared,

“… an empire of peace, because Italy wants peace for herself and for all, and goes to war only when forced. It is an empire of civilisation and humanity for the Abyssinian population.”

The shift to large-scale armaments and a strategy of opportunistic expansion altered Germany’s position in Europe. The other driving force behind that change was the Nazi Party’s self-proclaimed foreign policy expert, Joachim von Ribbentrop. He had helped secure the Anglo-German Naval Agreement in 1935 and was sent as Hitler’s special representative to London to try to secure a wider British alliance. His aims, first as special commissioner and from August 1936 as German ambassador were frustrated by his own diplomatic ineptitude, however. A more serious obstacle was the unwillingness of the British government to make any substantial concession to the German position. Ribbentrop, who succeeded in turning Hitler against a British alliance, was also keen to support Japan rather than China and was instrumental in setting up the Anti-Comintern Pact of November 1936. Together with Göring, he wooed Mussolini into the Pact following the Abyssinian War and tension with Britain and France over the Spanish Civil War. No clear political agreement existed between Germany, Italy and Japan. Still, they became identified in the mid-1930s as ‘revisionist’ powers who hoped to alter the existing distribution of territory and international power in their favour.

After this, the Rhineland Affair of 1936 has frequently been seen as ‘the last chance’ to stop Hitler without going to war. Subsequently, the crisis has been seen as the first conspicuous failure of appeasement. But the contemporary reaction was characterised by annoyance rather than failure. By 1936, the concept of a demilitarised zone was an anachronism and perpetuated among Germans the sense of inferiority that precluded a deeper and more permanent settlement. In any event, it is important to remember that by the autumn of 1936, there were many other matters preoccupying the British Cabinet, not least the future of Edward VIII. Once the abdication had been achieved, Baldwin’s career was nearly at an end. At the opening of the new parliamentary session in November 1936, he listened to expressions of concern about the country’s defences. Then he stated that in 1933-34 he had felt that he ‘could not have persuaded a pacific democracy in an election to support rearmament.’ It was this remark that led Churchill, years later, to claim that Baldwin had put party before country. In the summer of 1936, he told a parliamentary delegation which included both Winston Churchill and Austen Chamberlain, that he was not going to get Britain into a war with anybody for the League of Nations or for anything else. ‘If there is any fighting in Europe’, he added, ‘I should like to see the Bolshies and the Nazis doing it.’ (Jenkins, 1987, p. 159).

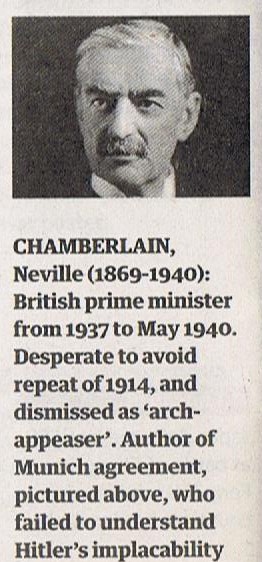

The ‘Baldwin era’ came to an end in May 1937 when Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister, a post he held for the last three years of a career which spanned more than two decades and included several senior government posts. The Cabinet was reshuffled from the existing pack. Having replaced Hoare, Eden remained as Foreign Secretary, initially seeming unalarmed by Chamberlain’s obvious intention to take more of an active interest in foreign affairs than Baldwin did. The Spanish Civil War, which began the previous year, prevented any easy accommodation with Rome. The Republican struggle against Franco’s Fascists attracted some enthusiastic support from Britain and France, but the British Cabinet had no enthusiasm for joining the war. A ‘Non-Intervention Agreement’ was in operation, but it didn’t serve as a barrier to German, Italian and Soviet activities. Nevertheless, Chamberlain deprecated the tendency among some of his colleagues to lump Germany and Italy together as ‘fascist powers’ (see the map below). For him, it was Germany that constituted the problem, and by the end of 1937, he had begun to address it directly and personally.

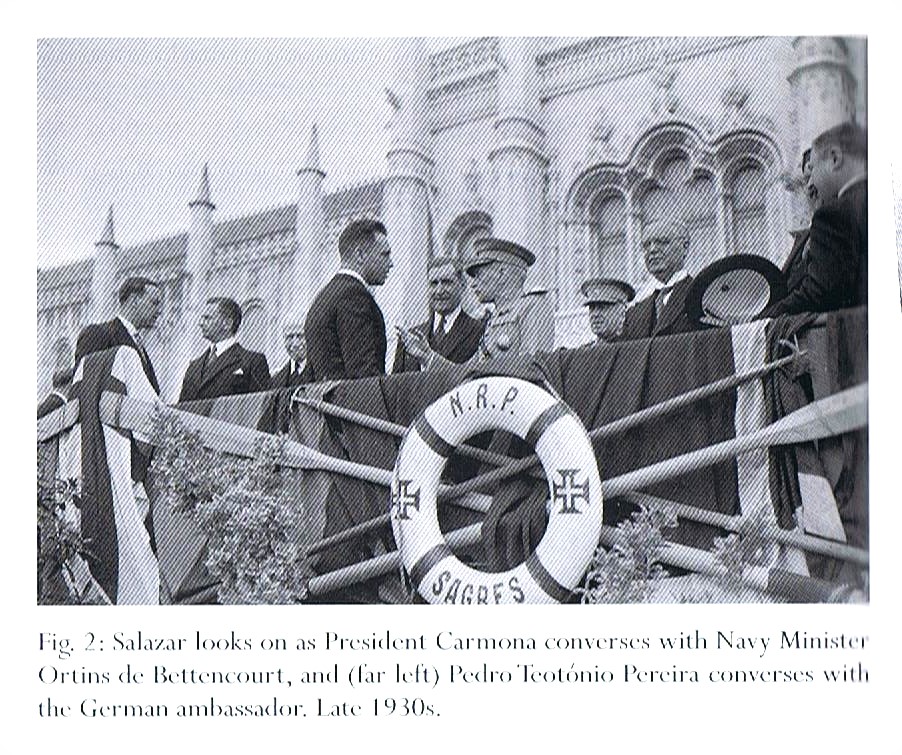

Nevertheless, it was impossible to deny that there was a common ideological thread linking the various far-right movements and repressive régimes that were emerging across Europe. But this thread did not produce identical movements. For example, when Salazar became Prime Minister of Portugal in 1932, at the age of forty-three, and was on the verge of creating an Estado Nova to tear Portugal away from its liberal moorings, he declined to follow the examples of Hitler and Mussolini by establishing a totalitarian party or an intrusive state to indoctrinate the masses. Salazar’s aim was the depolitisation of society, not the mobilisation of the populace.

Salazar was also a supporter of the church and a monarchist, like his neighbour General Franco, but he never considered restoring either to its former position and power, as happened in Spain. Instead, his formula was to create a ruling alliance of conservatives, some moderate liberals and a few nationalist ideologues, guaranteed ultimately by the armed forces. His ability to tap into nationalist feelings helps to explain his durability through to his death in 1970. He earned respect at home and abroad for showing a high degree of skill in foiling various international designs on Portugal which, though small, was strategically located but ill-placed to defend itself from the murderous conflicts of the 1930s and ’40s. Upon the eruption of civil war in Spain in 1936, Salazar backed the nationalists but then worked to keep Franco from throwing in his lot with Hitler after the ‘führer’ unleashed his wave of military conquests in 1939-40.

In mid-November 1937, Lord Halifax was sent to Berlin and Berchtesgaden. Although not altogether happy about this, Eden advised him to ‘leave the Germans guessing’ about British intentions. Halifax and Hitler got down to discussing specific questions concerning Danzig, Austria and Czechoslovakia. Halifax intimated that the ‘status quo’ in Central Europe was not sacrosanct, but that any change could only occur through ‘peaceful evolution’. Chamberlain’s view on these questions was that while Britain could not countenance Europe slipping under German domination, it was evident that, in some shape or form, German influence over central Europe was going to be extended. A dozen years earlier, his half-brother Austen, in negotiating the terms of the Locarno Treaty, had been adamant that Britain could not guarantee Germany’s eastern frontiers (and therefore those of its neighbours) in the same way as it did its western frontiers. The covert message was that these frontiers could be revised – by agreement. There was nothing that Britain could or should do directly to resolve disputes over boundaries or the problems of national minorities. Unlike France, Britain had declined to enter into specific treaty relations with Poland or Czechoslovakia that had been created after the First World War. Central-eastern Europe had never been a major British concern and it would be unwise to be too closely tied to the fortunes of new states with economic, social and political problems of considerable magnitude.

Differences mounted between Chamberlain and Eden, particularly on how to handle approaches to Italy. In the following month, Eden resigned. His resignation cannot be interpreted, however, as a dramatic dissociation from the policy of appeasement. Eden did not seek to make life difficult for his PM by maintaining a running critique of his policy in public. But the initiative in Europe seemed to be held by Germany, perhaps in association with Italy, and by contrast, France seemed bewildered and inert.

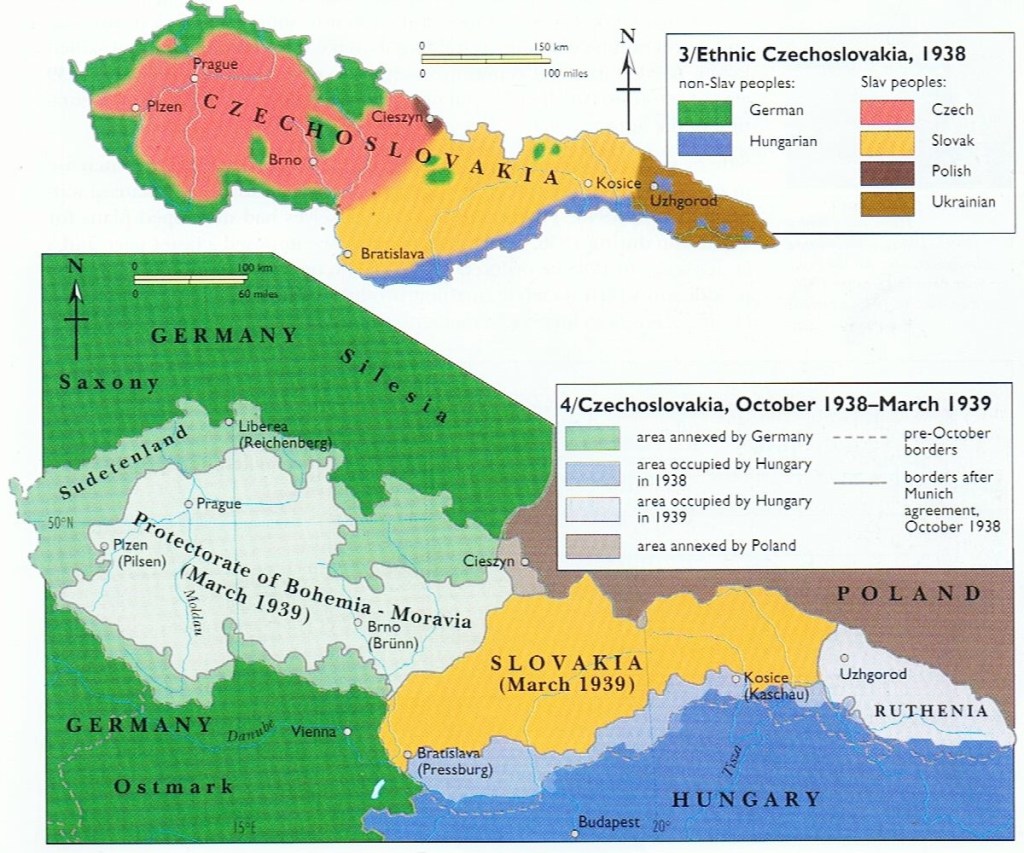

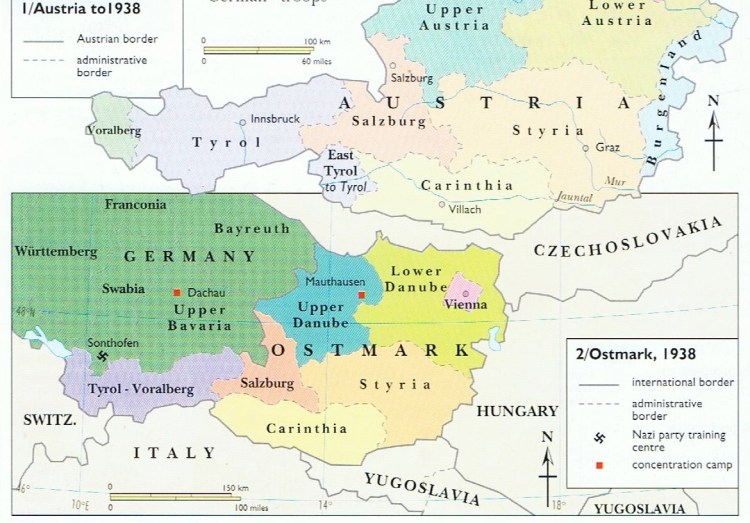

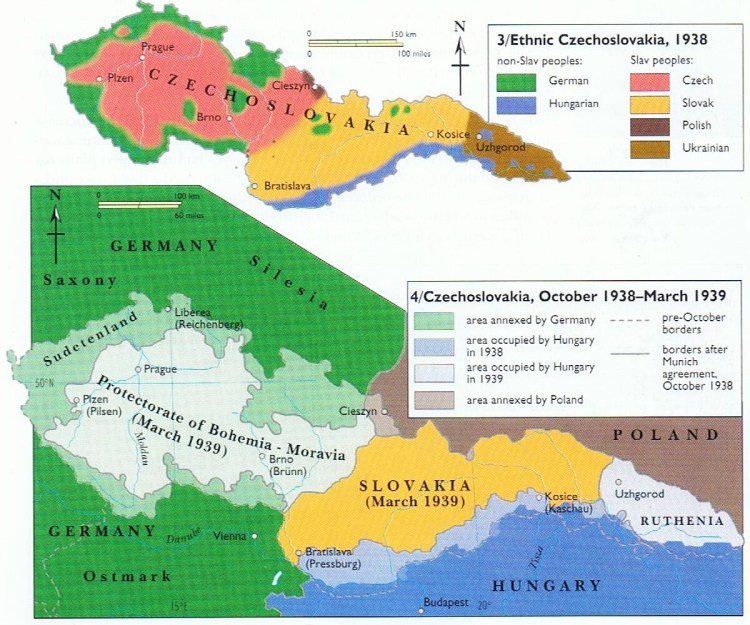

In the wake of the Austrian Anschluss, attention now switched to Czechoslovakia. As a result of the events of 12th March 1938, the Czech frontiers had become more vulnerable, as did the Hungarian borders. However, it was likely that the security of the Czechoslovak state would be as much threatened by the disaffection of minorities as by external aggression. The large German minority could be expected to become excited and press for full autonomy within Czechoslovakia or for outright incorporation into the German Reich. There was some sympathy for Czechoslovakia, which was considered to have preserved a liberal constitution more successfully than other central-eastern European states had done. On the other hand, there was doubt about the attitude of Czechs towards the country’s substantial ethnic minorities.

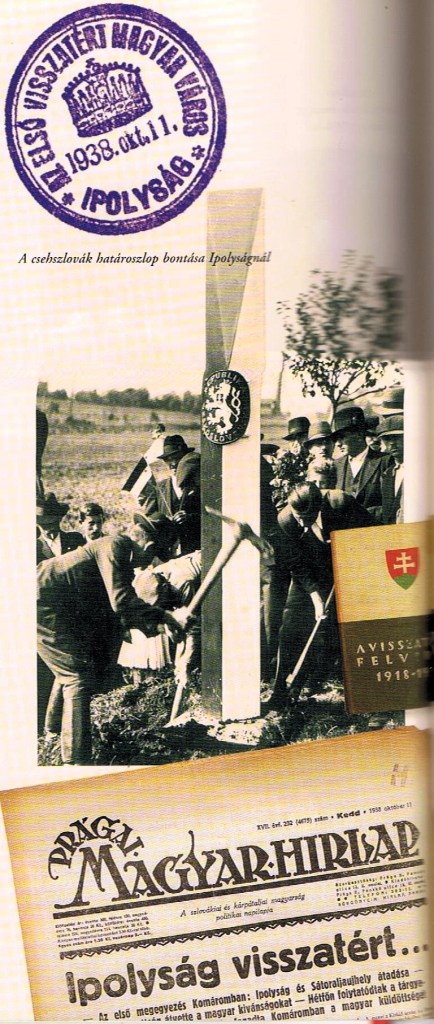

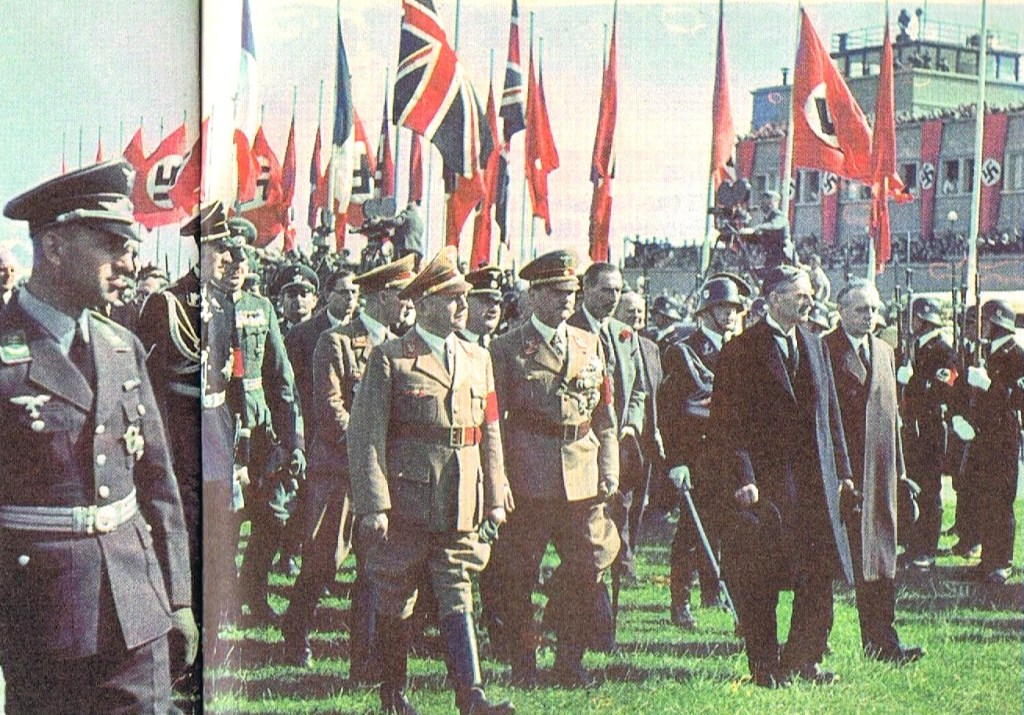

Twenty years after its ‘creation’ at Versailles, was the Czechoslovak state really viable? There was a certain irony in the fact that it appeared to resemble the Habsburg Empire in its population mix, though Czechoslovakia had supposedly been established based on national self-determination. Britain had never gone so far as France in cultivating special relations with Czechoslovakia. The consensus of Cabinet opinion was that no guarantee should be offered. At the Munich conference at the end of September, there was no place for Czechoslovakia itself at the table. Agreement was swiftly reached on the German occupation of the Sudetenland and on an international commission which would supervise the Czech evacuation. In principle, too, there would be a guarantee of the rump state. Chamberlain had allowed himself to be outplayed by Hitler on almost every point. That has been the predominant verdict of posterity; at the time, whether or not the policy could be justified depended on what happened next. While the Conference ‘settled’ the issue of the Sudentenland, it stipulated the need for further negotiations between Hungary and Czechoslovakia on Hungarian claims to Slovak territories. These having proved fruitless, and with the Western powers refraining from ‘interfering’ in the issue, Germany and Italy decided to act as arbiters in the decision on what should happen to Slovakia.

On 24th March, Chamberlain told the Commons that Britain’s vital interests were not involved in the region, though he added that it should not be assumed that the absence of legal obligations meant that Britain had no interest in its future. What followed – the Munich Crisis – has been the subject of many books, pamphlets and articles since. Here, I am more concerned with the Slovak ‘end’ of its consequences and relations with Hungary. It was not Munich itself, but the Czechoslovak Crisis as a whole that began the long descent into war. The British and French were not prepared to allow Hitler a free hand in east-central Europe to build a new German Empire. They were prepared to make what they regarded as reasonable concessions arrived at through negotiation. Hitler agreed and the Sudetenland was granted to him by the Czechs. But six months after Munich on 15 March 1939, German troops occupied Bohemia and Moravia, making it a ‘Protectorate’ of the Reich and leaving Slovakia a fragile independence as a puppet state of the Nazis.

Hitler drew a series of lessons from the crisis. First, he was determined not to give way again to what he saw as largely hollow threats from the West. Second, he believed that the concessions made by Chamberlain amounted to a virtual green light to further expansion in the East, showing that the Western powers lacked the willpower to obstruct him further. He developed an obsession with building the political and economic foundation in Central Europe of a German superpower whose military strength would produce a revolution in the European balance of power. The next target of German expansionism was Poland, which would become a protectorate of the Reich voluntarily, like Slovakia or more gradually like Hungary, or involuntarily, by war and occupation.

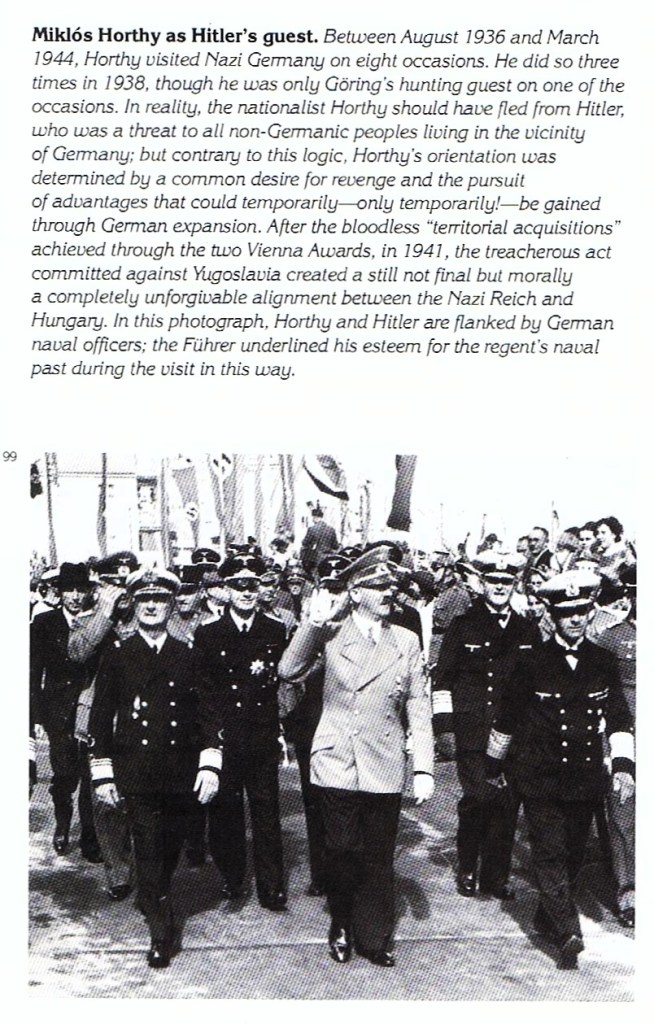

Horthy & Hungary’s Appeasement of Hitler, 1938-42:

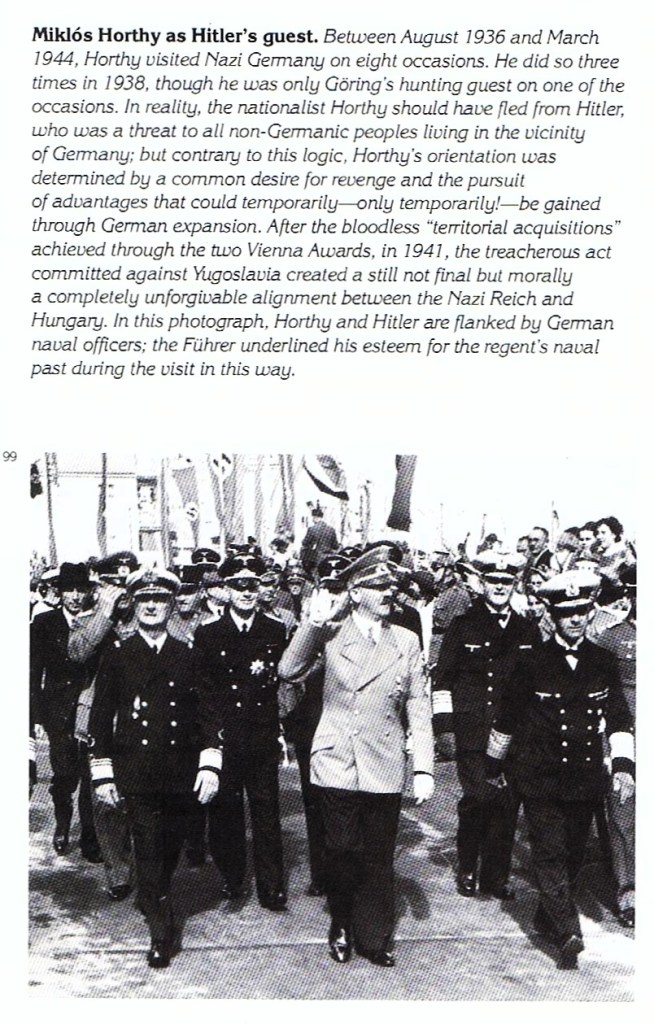

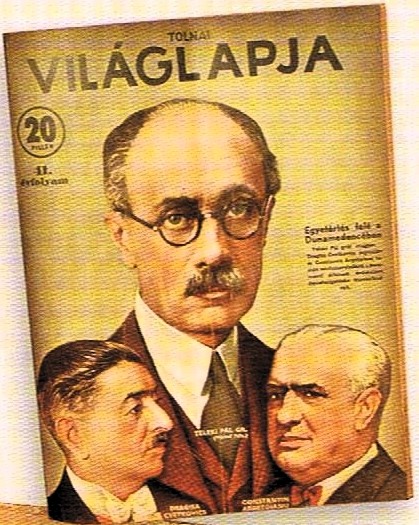

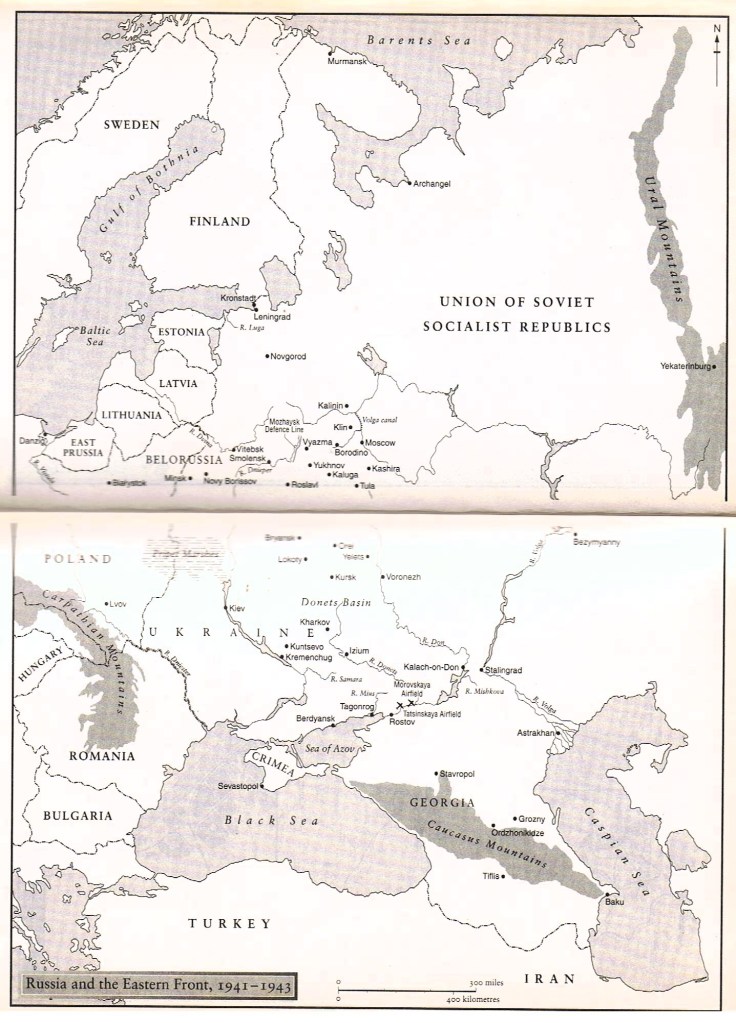

In his foreign policy, the Hungarian premier in 1938, Béla Imrédy hoped to capitalise on his good personal contacts in Britain, while Kányá, continuing as foreign minister, embarked on another round of negotiations with the Little Entente to secure some of Hungary’s revisionist aims by peaceful means. In return for Hungary’s commitment to non-violence, the Conference of the Little Entente in Bled in August 1938, Hungary’s military parity was recognised, and promises were made to improve the conditions of the Hungarian minorities in neighbouring states. However, the agreement was never ratified. Yet it was against this background that the Regent held his meeting with Hitler at Kiel, at which the Führer offered him the whole of one-time Upper Hungary if his guest was willing to launch an attack on Slovakia. However, Horthy and Imrédy were unwilling to act as agent provocateurs. Instead, they suggested a settlement based on ethnic principles in Slovakia as well as in the German-populated western fringe of Bohemia, the Sudetenland. Having been summoned by Hitler again on 20 September, they were relieved to learn that the Czechoslovak crisis would be resolved at the Munich Conference of the Great Powers.

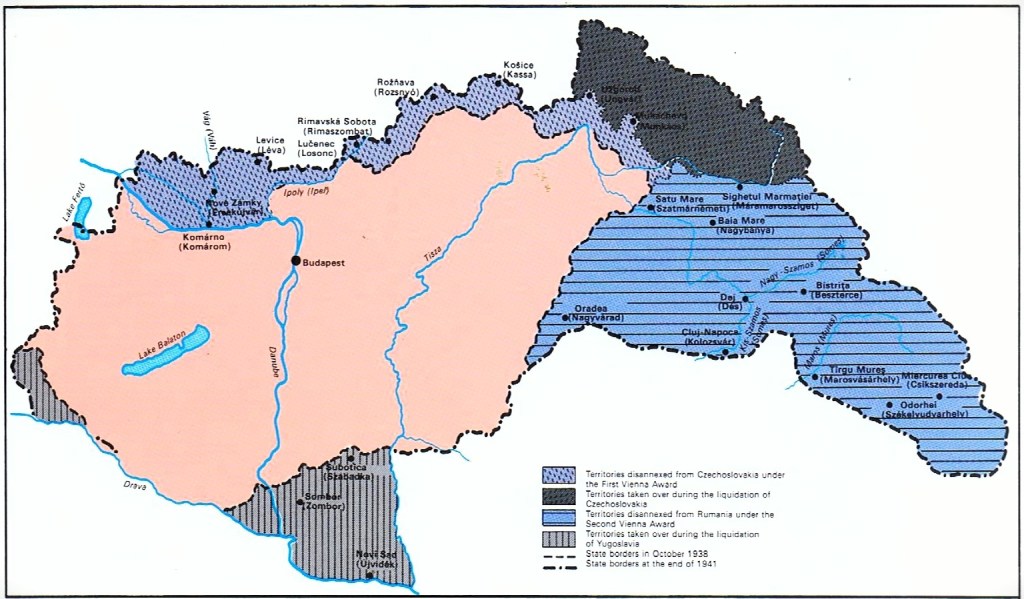

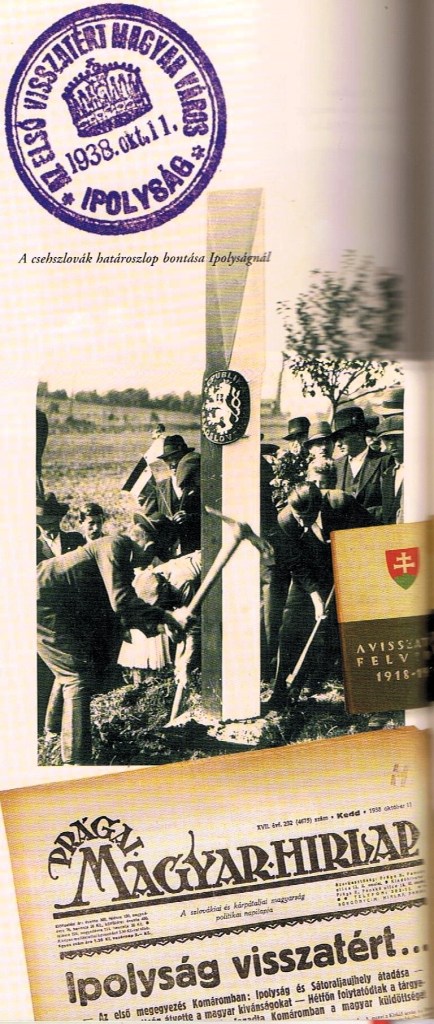

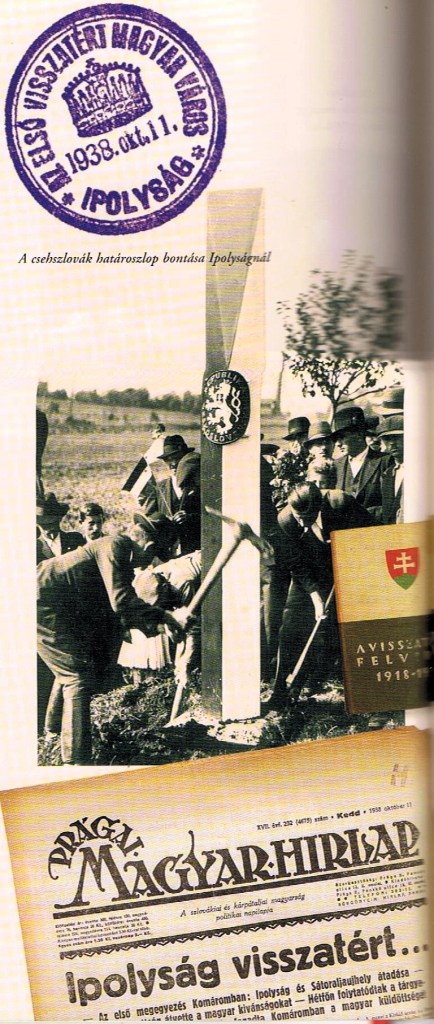

A month after Munich, on 2nd November 1938, Hitler and Mussolini, acting through their respective foreign ministers, Ribbentrop and Ciano, functioning as a ‘court of arbitration’, supported Hungary’s annexation of southern Slovakia, which took place suddenly and without consultation with Britain and France. Twelve thousand square kilometres with over a million inhabitants (between 57 and 84 per cent of whom were Hungarian, (depending on whether the Hungarian or Czechslovak censuses were used) were awarded to Hungary. This reduced Chamberlain to stating in the House of Commons that, “We never guaranteed the frontiers as they existed. What we did was to guarantee against unprovoked aggression – quite a different thing.” (Cited in Roberts, 2010, p. 9). This first success of revisionism was welcomed in Hungary, even by the Left-Liberal opposition, although there was still some resentment in the establishment and right-wing circles of the award’s failure to recover other parts of Slovakia, and in Ruthenia. A planned operation to occupy Ruthenia at the end of November 1938 was called off due to Hitler’s objections. This First Vienna Award made it clear that any further success in the revision of Trianon would depend on German support. The decision was based chiefly on ethnic considerations, which meant that the boundary line twisted and turned in such a way that for the next few years, every train heading for Kassa (‘Kosice’) had to pass through Slovakian territory before reaching its destination.

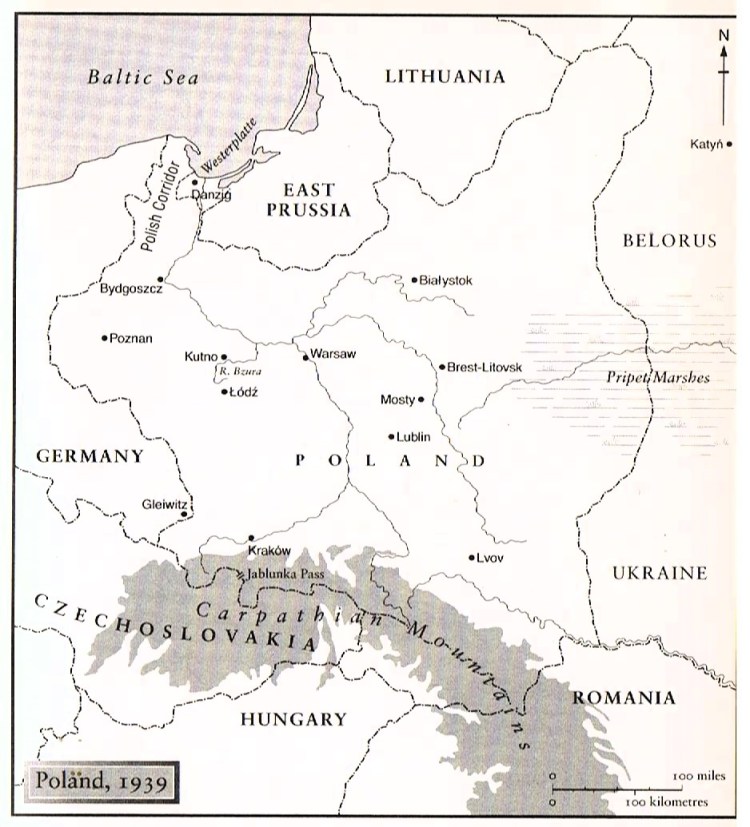

Europe showed no signs of settling down in the early months of 1939. Justified or not, rumours of further German expansion abounded. However, just six months after the Munich conference and a year after the Anschluss, it was Czechoslovakia that once more held the headlines. German troops entered Prague and established a Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Slovakia became a nominally independent ‘puppet state’ under German ‘protection’. Alerted at last by Hitler’s occupation of non-German-speaking territory to the real dangers of German expansion, Britain and France pledged to defend Poland, Greece and Romania from similar Nazi aggression and embarked on a crash programme of military spending. Hitler’s aims could no longer be restricted to the inclusion of all Germans in one German state. Both Hungary and Poland found the prospect of grabbing parts of the dying Czechoslovak state lands irresistible. Poland seized Cieszyn (Teschen), while Hungary finally obtained parts of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia, which had substantial Hungarian minorities, previously belonging to the Crown lands of St Stephen.

However, Premier Imrédy’s attempts to demonstrate Hungary’s pro-German commitments by governing the recovered territories by decree led to a vote of no confidence in the National Parliament, unprecedented in the Horthy era. But as his opponents refused to take office in his place, he was allowed to continue and to form a new government, which he thought it essential to pack with pro-German politicians. Kánya was replaced by István Csáky as foreign minister, a firm believer in the need to tie Hungary’s resurrection to the success of German arms, which according to him was beyond reasonable doubt. It was during the subsequent months that the Nazi-style Volksbund became legalised and that Hungary announced its decision to leave the League of Nations and to join the Anti-Commintern Pact. To a considerable extent against his own wishes and because Britain remained apathetic towards Hungary, Imrédy became over-anxious to please the Germans, which led to his dismissal in February 1939, in circumstances quite similar to that of his predecessor, Gömbös.

Hungary’s annexation of Sub-Carpathia demonstrated that the central-eastern frontiers were no longer simply being adjusted, but were being redrawn by force, in the direct interests of Germany and its allies. This helps to explain the decision, after Prague in March 1939, for Britain to give a unilateral guarantee to the Polish government. Britain singled out Poland for this remarkable reversal of the attitude toward central Europe held by all the previous British governments since Versailles. It made it clear that war would result if Germany violated Poland’s sovereignty. France backed up the British declaration, albeit reluctantly, From the point of view of European stability, Poland was therefore the most explosive choice Hitler could have made for the next stage of Nazi expansion. But he simply refused to believe that Britain and France would declare war, asserting to his generals that the allies were bluffing, a view from which he wavered little until 1 September.

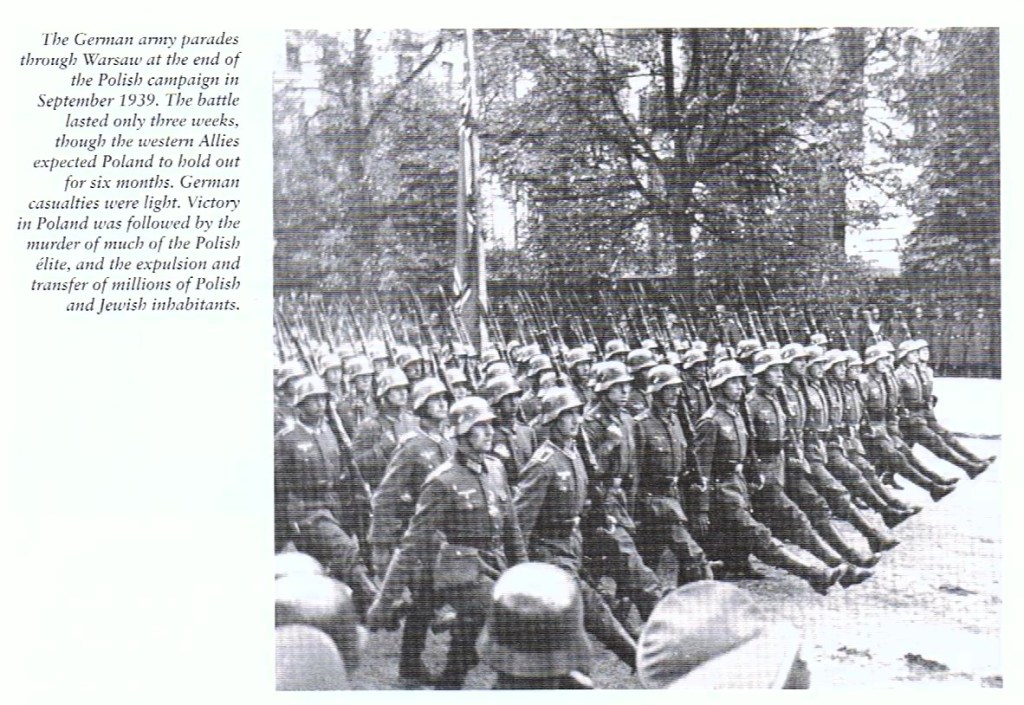

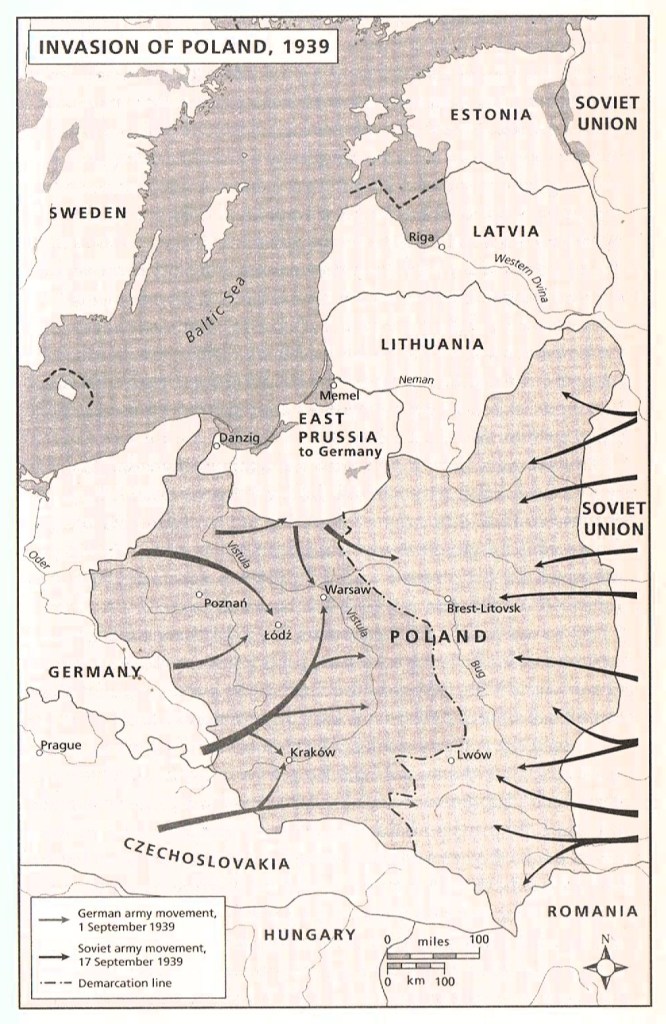

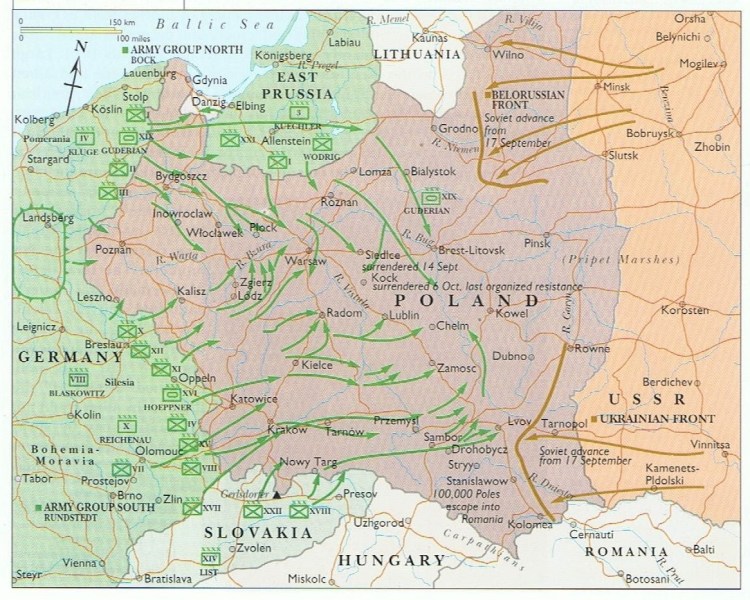

In reality, Germany was indeed free to attack Poland, especially after the Nazi-Soviet Pact was signed in August. Stalin finally took the bait after he became convinced that Britain and France had little to offer him in exchange for Russian cooperation. This meant that it was not just Germany that invaded Poland on 1 September, but also the Red Army from the east sixteen days later. Franco-British support for Poland was therefore likely to be of little assistance. Stalin simultaneously annexed the three Baltic States; he would also have taken Finland if he could. After the declaration of war with Germany, there was no enthusiasm for protracted conflict. There might still be a place for negotiations but, if so, they could now only be in the context of war. All the steps leading up to the partition of Czechoslovakia had already violated the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Still, neither France nor Britain did anything to stop Hitler when they could. They had caved in over the Sudetenland, which had never belonged to Germany, and it was only with the invasion of Bohemia and Moravia that Western resolve finally stiffened in 1939.

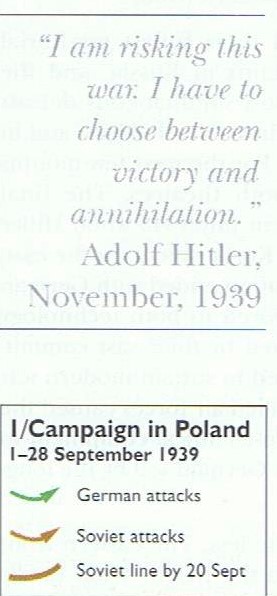

Hitler had gambled again and won. But he was not a complete gamber, since he had used the pact with Stalin to bolster his conviction about Western bluff. With no prospect of a Soviet alliance and no effective way of helping Poland militarily, Hitler could see no reason for Western intervention. Although Goebbels and Göring tried to convince him that the risk was too great, Ribbentrop, whose own reputation with the Führer depended on his reading of British strategy, spurred Hitler on. Two days after the Blitzkrieg on Poland began, Britain and France declared war to his surprise and consternation. More importantly, he had achieved the exact reverse of his goals in 1933: a treaty of friendship and cooperation with Soviet Russia and a war with Britain and France.

The Western allies had been in no position to offer Stalin inducements to cooperate with them and the Poles had no desire to allow Soviet troops into their country, even to fight the Nazis. Hitler, in contrast, had no compunction about offering Stalin incentives to adopt a benevolent neutrality in the event of a German-Polish war. In fact, the secret protocols to the Non-aggression Pact envisaged the division of the Baltic States and Eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres. Unlike the German conquerors, the Soviet forces went through the motions of organising plebiscites to demonstrate the popular will of the conquered peoples to join the Soviet Union. The following June, as Hitler’s army entered Paris, all three Baltic states ‘voted’ to join the Soviet Union.

Yet historians still remain puzzled as to how this could have led to the carnage involving the deaths of around sixty million people worldwide. In his (2009) essay for The Guardian‘s commemorative supplement on the Origins of the Second World War, Niall Ferguson updated the familiar ‘countdown’ to war from a truly global perspective (guardian.co.uk/readers offers/second world war.) Ferguson pointed out that, far more than the first world war, which was genuinely a European war, fought mainly in Europe by Europeans, the second world war was truly global. Therefore, we can only make sense of its true character by taking a world-historical view of its events. To do that immediately calls into question its ‘advertised’ starting point of 1 September 1939, marked by the invasion of Poland. Ferguson argues that, in reality, it began two years earlier with the full-scale Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Even if we focus on Europe from a global perspective, there was no sense of anything approaching twenty years of peace on the continent before 1939.

Hungary & the Road to War in the East, 1939-41:

For the Hapsburg, Ottoman and Romanov empires, the true losers of the First World War, there was scarcely any peace after 1918.

The so-called “successor states” of Austria-Hungary experienced a series of internal and cross-border conflicts in the early 1920s. Then, by September 1939, there had already been three years of civil war in Spain. Many historians have taken this further in representing the period from 1914 to 1945 as a second Thirty Years’ War or a prolonged ‘European civil war’. Some have even suggested that the entire period, or ‘era’ from 1904 to 1953 represents a ‘Fifty Years’ War’, playing out what was essentially the same conflict across several ‘theatres’ including the European empires in North Africa and the Middle East. The key to understanding these fifty years was the sustainability of Western imperial power over the rest of the world, most importantly over Asia.

For all these reasons, Ferguson argues, the events of September 1939 look less like the beginning of a world war and more like the escalation of an ongoing global conflict. It was a war, above all, for domination over ‘Eurasia’, and it was not really over until 1953, by which time its most hotly contested zones in central and eastern Europe had been divided in two, with deadly, impassible borders dividing them. Ferguson concludes:

‘That we describe this cataclysmic world war as having begun in Poland on 1 September 1939 is thus merely a trick of the historical light – an illusion caused by our own parochialism.’

Other relevant but awkward questions that Ferguson poses are: Why should the Treaty of Versailles be blamed for so much, when the other post-1918 treaties imposed on Austria-Hungary (St Germain and Trianon) and the Ottoman Empire (Sévres) were, in terms of territory, much harsher? Why, if the arguments for appeasement were so strong in September 1938, did they cease to be so just a year later when the strategic position of the Franco-British alliance had significantly worsened?

Hungary’s annexation of southern Slovakia took place suddenly and without consultation with Britain and France. This reduced Chamberlain to stating in the House of Commons that “we never guaranteed the frontiers as they existed. What we did was to guarantee against unprovoked aggression – quite a different thing.” Then, in the early hours of 24 August 1939 a comprehensive Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact was signed in Moscow. Up until that point, Hitler’s treatment of the Austrian President Kurt von Schusnigg, the Czech President Emil Hácha and the British and French leaders had been characterised by trickery, bullying and constant piling on of pressure, to which they had responded with a mixture of gullibility, appeasement and weary resignation. Yet with his lifelong enemies the Bolsheviks, Hitler was attentive and respectful, though no less duplicitous.

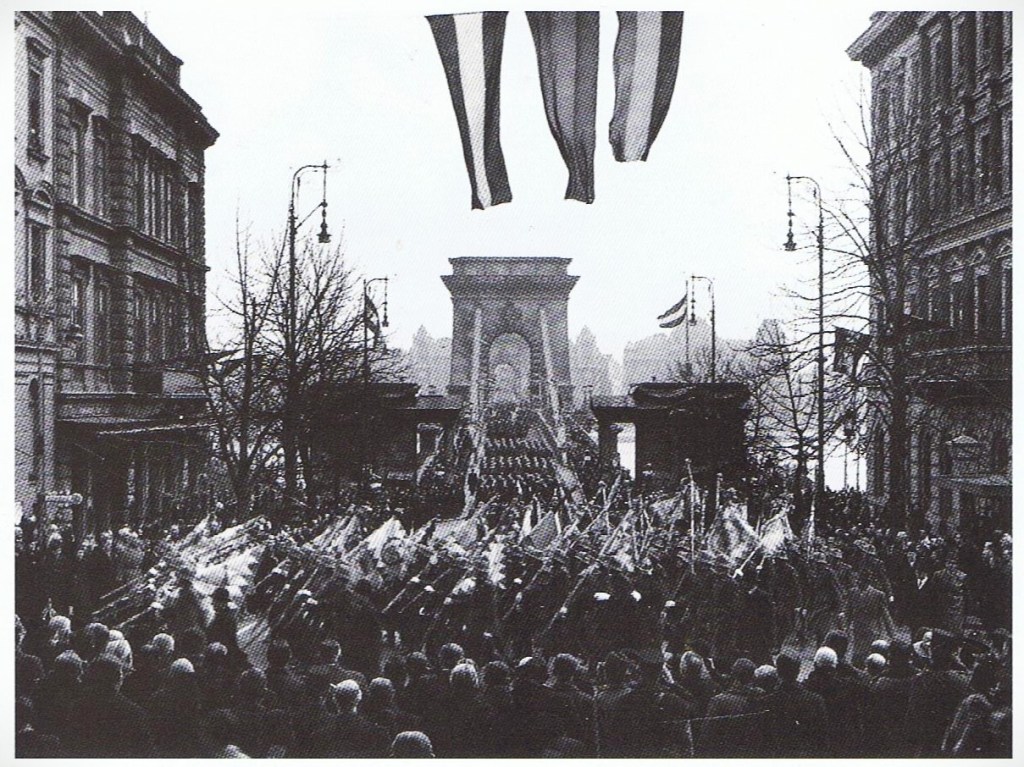

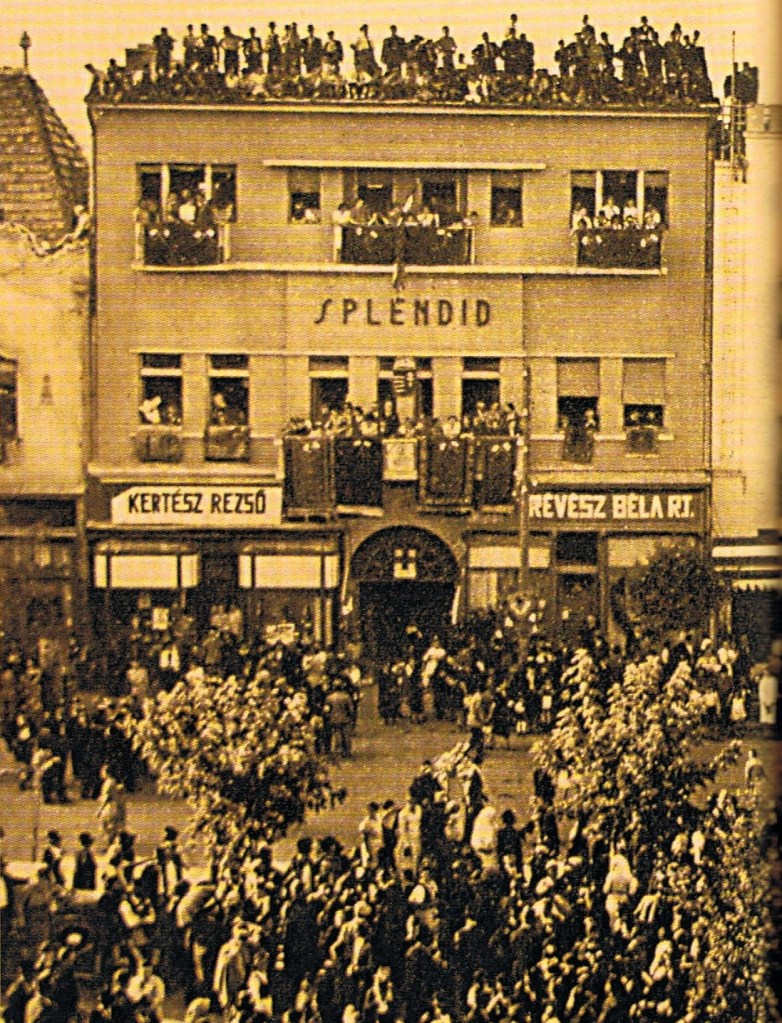

At the beginning of 1939, when Hungary joined Japan, Germany and Italy in the Anti-Comintern Pact, the USSR broke off the tenous formal relations which had existed since 1934. But when Stalin decided on his non-aggression pact with Hitler, the Soviets were apprehensive and signalled their preparedness to make additional conciliatory gestures to guarantee their border with Hungary in the Carpathians. At the suggestion of the Soviets, diplomatic relations were restored in the autumn of 1939, and a year later the two countries signed a trade agreement. Then Hungary handed over two Communist leaders sentenced to life imprisonment (the Communist Party was illegal in Hungary in the interwar years), Mátyás Rákosi and Zoltán Vas. As a reciprocal gesture, the Soviets sent a special train with a guard of honour to Budapest, carrying fifty-six flags of the Hungarian Army captured by the Tsar’s forces during the suppression of the 1848-49 War of Independence (the celebration on the Danube is pictured above). However, this turned out to be a fleeting interlude of fraternity in the relations between Hungary and the USSR.

Through his Pact with Stalin, Hitler simply wrong-footed the Western Allies again. Despite his previously unwavering hostility to communism, he neatly sidelined the one country he took to be his most serious enemy. For his part, although Stalin had loudly condemned the Western appeasement of Germany before Munich, Stalin showed less enthusiasm for confronting Hitler once the Anglo-French capitalists had announced their guarantees of Polish, Romanian and Greek sovereignty following the Nazi occupation of Prague. However. such had been the rhetorical animosity between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia that few diplomats or politicians were prepared for the sudden reversal of policy involved in the Non-aggression Pact.

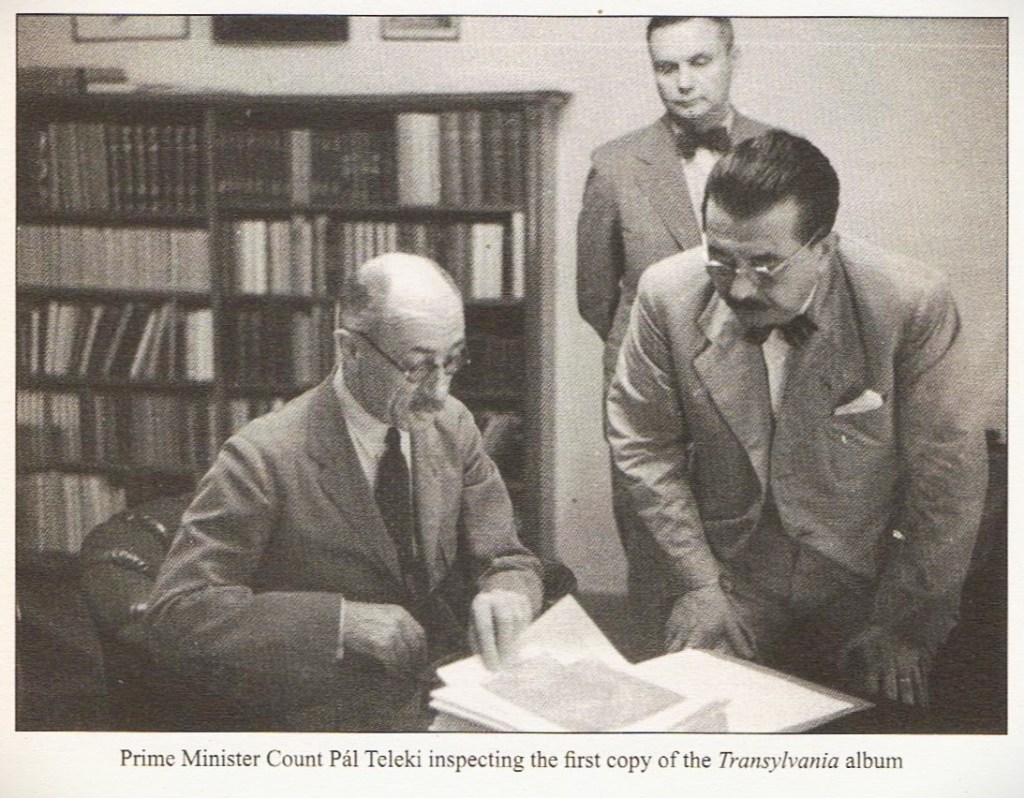

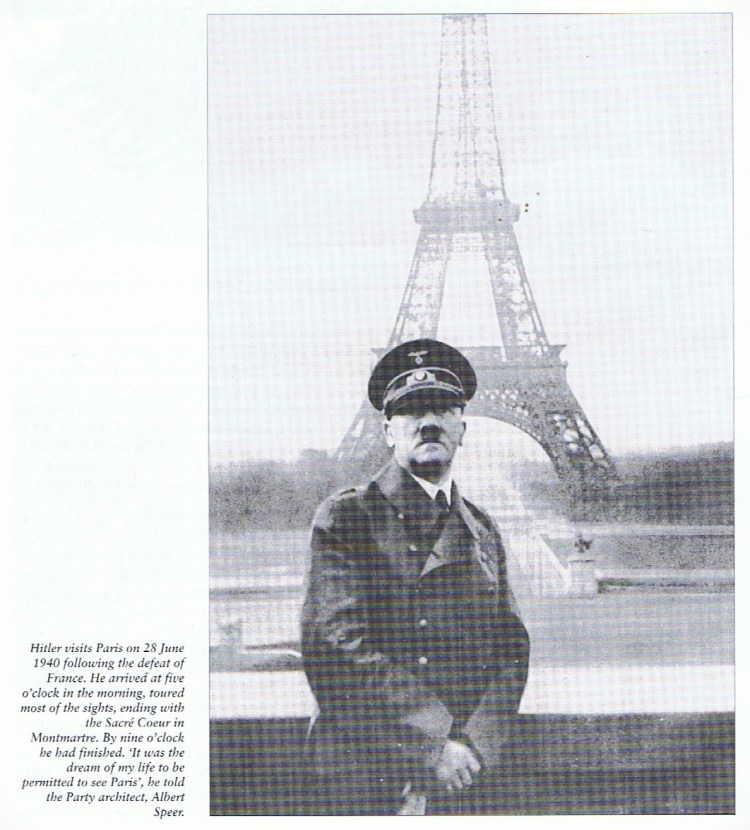

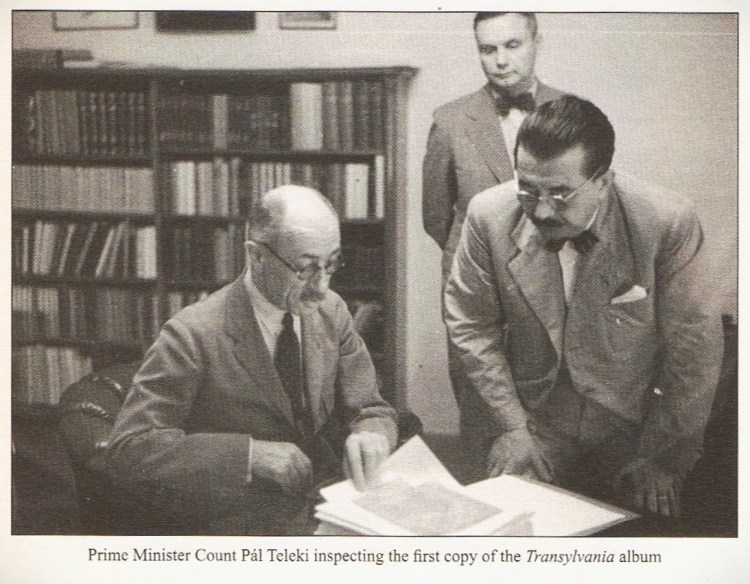

At this point, Hitler seemed invincible. In June 1940 France collapsed and he was master of the continent, though Britain fought on alone. Hungary had to court the Nazis’ favour, though they often did so with misgivings. Hitler might offer a further revision of Trianon, the most coveted of which was regaining Transylvania. Hitler was concerned that Hungary might attack Romania, because he depended on it for oil, and it was already under threat from the Soviet Union now that it had lost French protection. In June 1940, after the fall of France, the Soviet Union moved, demanding the retrocession of north-eastern Romania and offering cooperation to Hungary. Pál Teleki and Horthy both hated the Soviets and ignored the approach, but they did mobilise the army, and public opinion was in an uproar about the possibility of regaining Transylvania. Hitler called Teleki and Csáky to Munich and told them he would find a solution. Again there was arbitration leading to the Second Vienna Award, on 30th August 1940. Transylvania was partitioned, with the northern part returned to Hungary. Admiral Horthy got on his white horse again and rode triumphantly through Kolozsvár and Márosvásárhely, to widespread celebration. This time Hungary obtained 43,000 square kilometres and 2.5 million souls, two-fifths of whom were Romanian, while the Romanians in the south retained 400,000 Hungarians. The ‘bill’ for this was tall; adhesion to the Axis Powers; allowance of German military transports through Hungary; and privileges for the German Hungarians. There would also be further measures against the Jews as well as allowance of extreme right ‘activities’.

The Second Vienna Award was put together in the summer of 1940. This agreement, again arbitrated by Ciano and Ribbentrop, gave a part of Transylvania back to Hungary in such a way that the ethnic ratio of the transferred population was more unfavourable because of the more complex location of the settlements: Hungarians comprised not quite 52%, while Romanians reached 42%.

The Soviet Union made use of Hitler’s Western offensive to occupy Finland and the Baltic states. However, the difficulties experienced by the Soviet army in attaining these objectives suggested that it posed no threat to Germany. Stalin’s anxieties about this, occasioned by the swift German conquest of France, showed in the alacrity with which he accepted their invitation in October 1940 for Molotov to visit Berlin for discussion on the way forward for the Pact. Since the summer of that year, Stalin had dared to think that the Germans may be planning to attack the Soviet Union. The coincidence of interests that had permeated the two meetings over the Non-Aggression Pact the previous year had all but evaporated. It had been replaced by suspicion. For the Soviets, anxiety rested on German intentions regarding the ‘buffer states’ – Hungary, Romania and especially Bulgaria. Hitler’s longstanding rhetoric about acquiring Lebensraum for German colonisation seemed to be becoming a reality. Added to this, the Soviets were almost as obsessed with ensuring that their ships had passage through the Dardanelles, the narrow straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, controlled by Turkey.

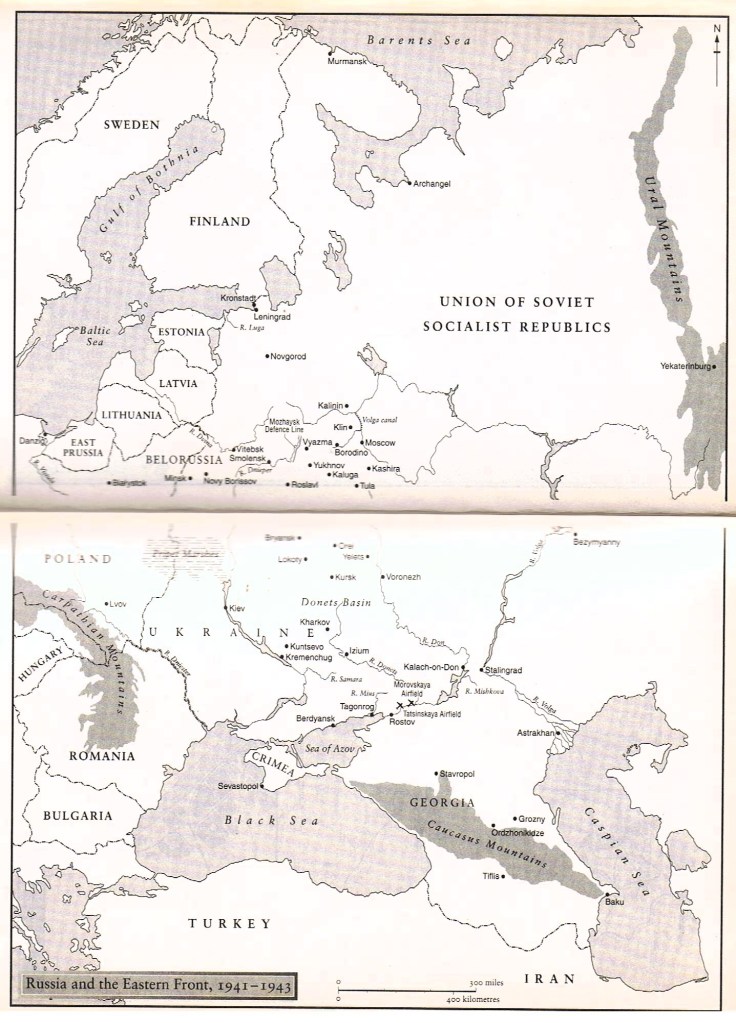

From 1939 to 1941, Hitler seemed to favour Hungary’s neighbours, i.e. Slovakia, Romania and Croatia, which meant that Germany would no longer support Revisionist claims directed against these states. In the summer of 1939, when Hitler was about to engage in his final aggressive step on Poland’s borders, Hungary faced a conundrum. If it supported him, it would be ratting on an old ally, and a friendly associate. Moreover, Hungary’s annexation of Carpatho-Ruthenia gave the two countries a common border, a change that was celebrated on both sides of it. On the other hand, if Hungary stayed out she might lose the chance of a further revision of the Trianon frontiers; Hitler ranted to this effect on 8th August 1939, and Mussolini pressed the Hungarian government to follow Nazi instructions. Again, Teleki prevaricated, and a letter of his was disavowed by his own foreign minister. A decisive and surprising leap on the road to war in the east occurred on the 23rd of August when Hitler concluded his pact with Stalin. The two decided to partition Poland and by implication divide central-eastern Europe between them into zones of influence or occupation. When Germany attacked Poland on 1st September and Britain and France declared war two days later, Horthy knew that sea power would eventually prevail, and the British would win. However, the immediate German pressure was overwhelming, and Hungary allowed the Wehrmacht to use railways east of Kassa at least for goods. When Poland collapsed, 150,000 Poles took refuge in Hungary, from where most went on to fight in the West.

So, when Molotov left Moscow for Berlin in November 1940, he was tasked by Stalin with asking a series of questions about German intentions towards central-eastern Europe and the Balkans. Hitler, on the other hand, had very different aspirations for the Molotov meeting. Although he had called internally, in July, for an invasion of the USSR, this remained only one possible course of action, even if it was the one he most favoured. He also wanted to see if the Soviet leadership could be persuaded to leave the central-eastern states under German control, instead diverting their attention to the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, snatching territory and influence from the British Empire. In later discussions with Ribbentrop on the same visit, however, Molotov continued to ask about German intentions on the partition of Poland as well as its policy towards Hungary and Yugoslavia. Like the Führer, Ribbentrop wanted to return to the ‘decisive’ question as to whether the Soviet Union was prepared to participate in the ‘great liquidation of the British Empire’ compared to which all other issues were considered by the Nazis to be insignificant, to be settled as soon as an overall understanding was reached. However, the Soviets were unwilling simply to leave the whole of central Europe, including the Balkans, to Germany. As a result, the relationship between Germany and the Soviet Union was clearly splitting apart. Hitler became convinced he was right to push forward with plans to conquer the USSR and take what he needed by force. Thus, the final formal directive for the invasion of the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa, was given on 18 December.

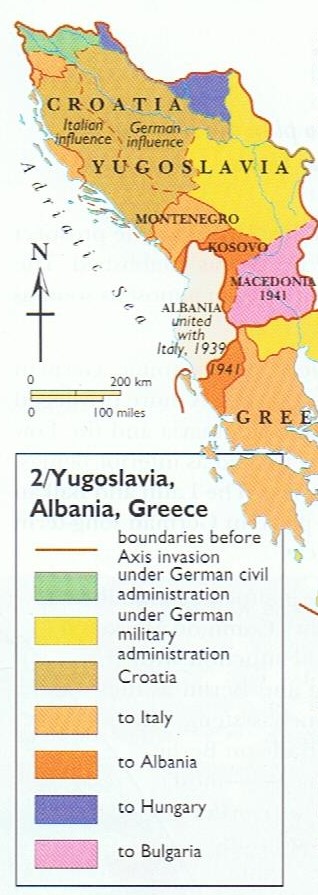

There remained one item on the revisionist agenda; the partly Hungarian ‘Vojvodina’, where there was also a German minority. It was now in Yugoslavia, which was a complication both Horthy and Hitler wanted to do without. Hitler wanted a Yugoslavia that would be aligned with the Axis and was also preoccupied with Britain. The Hungarians cultivated good relations with Belgrade, and a treaty was signed in December 1940, to the effect that there will be permanent peace and eternal friendship between the two parties. However, Hitler was drawn into the Balkans after all due to Italian blundering. Mussolini had attempted an invasion of Greece which was a disaster: he had to be rescued. Although Yugoslavia had joined the Tripartite Pact on 25th March 1941, there was a pro-British coup, followed by a German invasion. Teleki was informed that by joining this Hungary could have a further revision, and a German army delegation arrived in Budapest to arrange this.

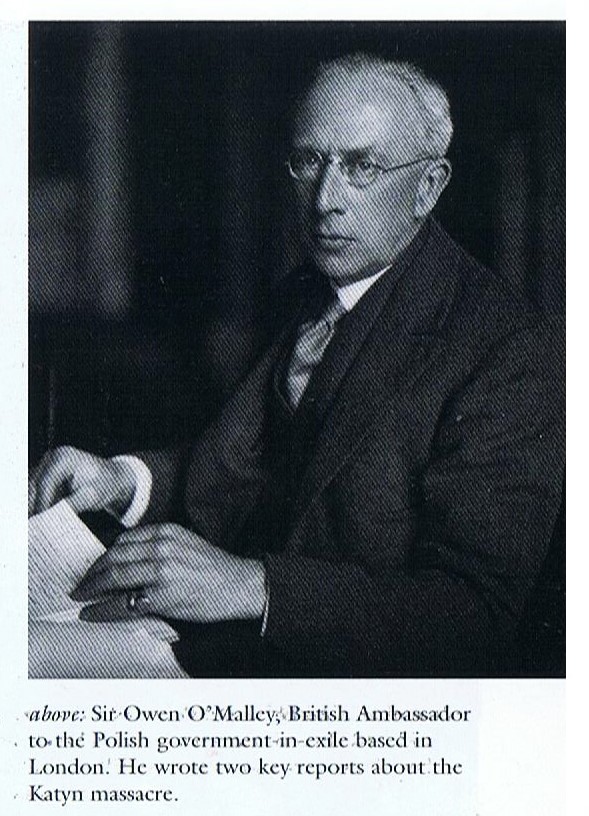

Teleki had promised the British that he would not comply with German demands that were ‘irreconcilable with honour’, but on 1st April he voted for the reannexation of Vojvodina. The minister in London, György Barcza, sent a telegram to the effect that if Hungary went ahead, it would mean war. The British minister in Budapest, Owen O’Malley (pictured above), vigorously accused Horthy of underhand conduct, and Teleki came under tremendous strain. On 3rd April, he shot himself, having scribbled the following note to Horthy:

‘We have become breakers of our word… taken the side of scoundrels… the most rotten of nations.’

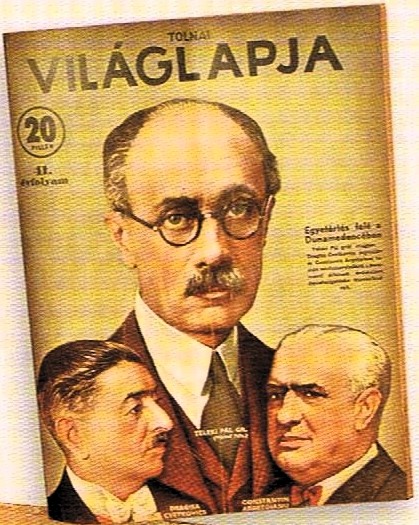

The gesture was late politically and ineffective, but absolutely genuine as a personal act. On hearing the news of his death, Winston Churchill said that an empty chair would be kept at the future peace conference for him. This pronouncement belongs among Churchill’s most noble moments, but at the 1946-47 Paris Peace Conference, not a word was spoken about the empty chair that Pál Teleki’s phantom was to occupy.

At the time of Teleki’s suicide, Horthy was unmoved, appointing the pro-German Bárdossy as his new premier. Hungary joined the invasion of Yugoslavia, which broke up. Horthy was warned that he could expect no favours from ‘a victorious Britain and the United States of America’ by breaking a newly signed treaty of eternal friendship. Out of this, Hungary did get another 11,500 square kilometres with another million inhabitants, just over a third of them Hungarians. By the Spring of 1941, Hungary had taken back about half of its lost territories, some eighty thousand square kilometres with 5.3 million people, of whom forty per cent were Magyar. But there was a considerable price to pay, as the country had now, in effect, surrendered its independence to Germany, long before it declared war in its support.

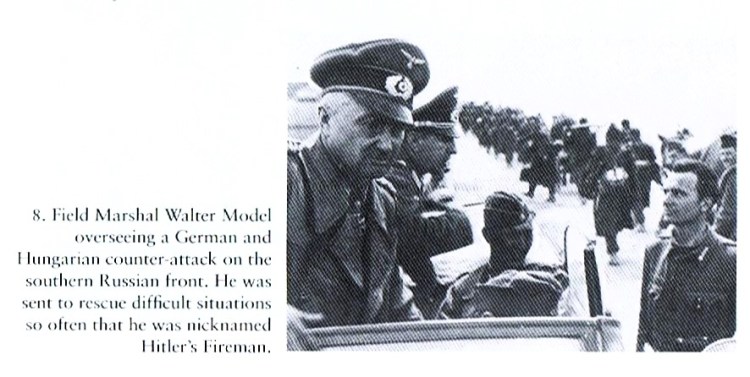

That same spring of 1941, British policy was suffering one disastrous setback after another. In March, the long-anticipated pro-allied Balkan front crumbled when Bulgaria, Hungary, and Romania joined the Axis powers; Turkey, withstanding all pressure, remained neutral. On 6th April, German troops poured into Yugoslavia and Greece, sweeping up the allied armies as they advanced and trapping ten thousand British troops. Three weeks later, the swastika flew over the Acropolis. By the end of May, German paratroops had overrun Crete. This was not a repetition of the ‘Norway fiasco’ that Churchill feared; it was a disaster of even greater magnitude, and it was compounded by the failure to exploit British military successes in North Africa, for on 3rd April Rommel began to drive the British army out of Libya. Churchill’s responsibility for the action was considerable. Later that year, he conceded that Greece had been an ‘error of judgment’. The humiliation of the rout cut deep and criticism was harsh.

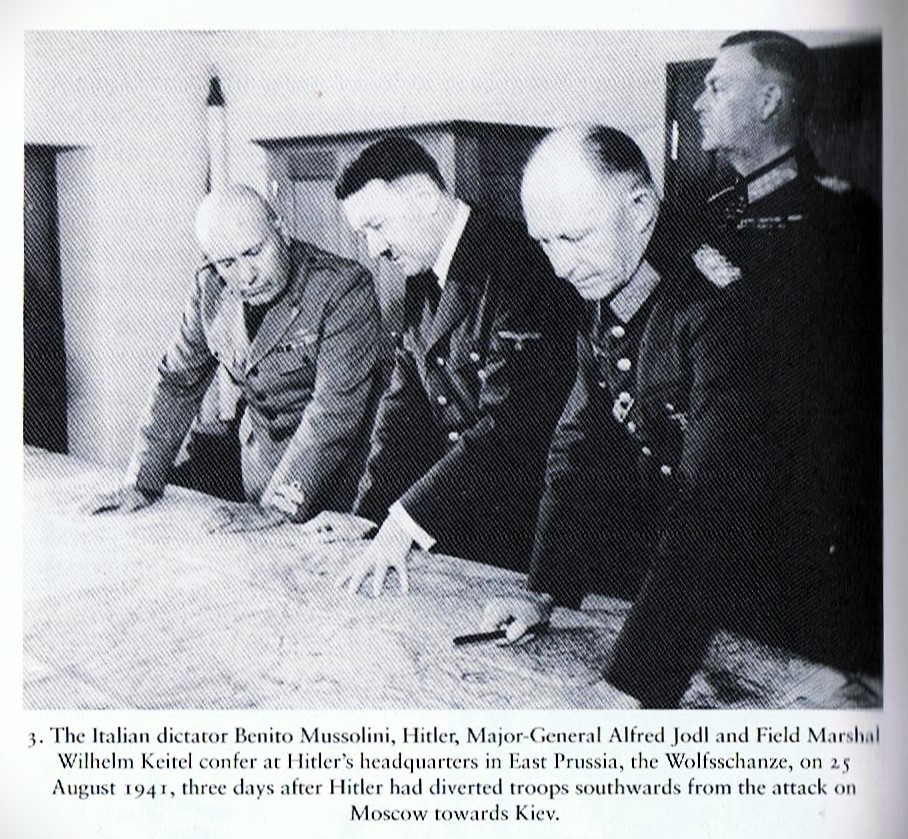

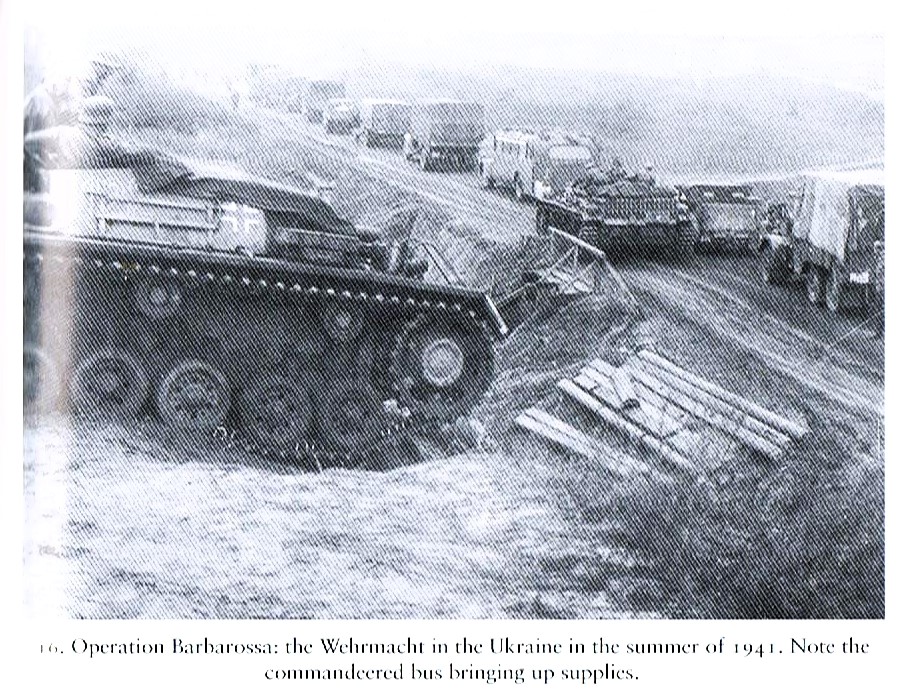

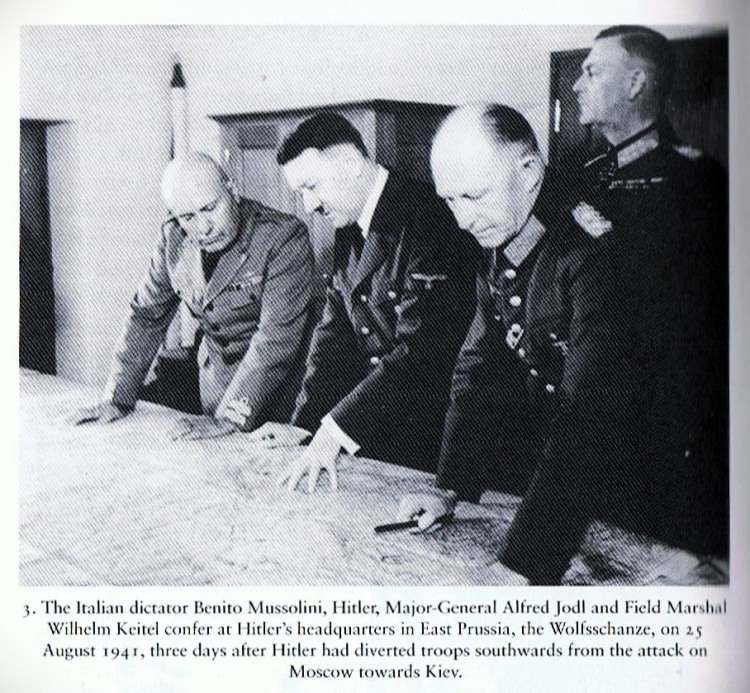

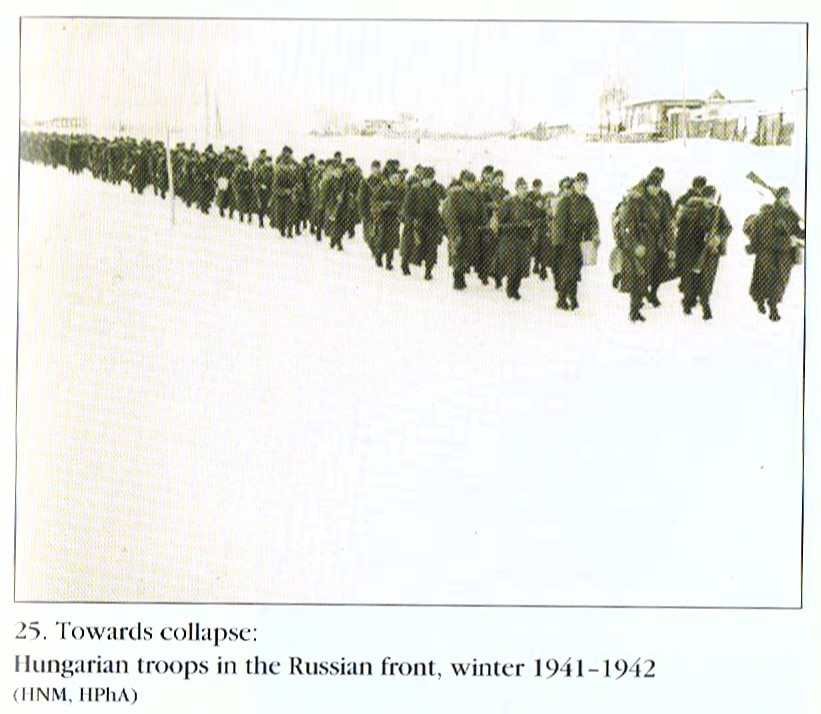

In June 1941, the whole orientation of the war changed when the Germans attacked the USSR in ‘Operation Barbarossa’. Hungary was involved, though it had had surprisingly good relations with Moscow during the months of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. On 23 June, József Kristóffy, the envoy to Moscow, announced that Molotov was willing to recognise Hungary’s territorial demands on Romania; but Bárdossy suppressed the report, and took advantage of an unexplained episode when unidentified foreign aircraft dropped bombs on the town of Kassa. Thought by many historians to have been a plot between Hungarian and German staff officers to blame Moscow and declare war, it led to forty thousand men crossing into Galicia to join in the invasion of Soviet Ukraine. Initially, the offensive went well. Hungary also supplied Germany with grain and bauxite, for which it was not paid. By December 1941, however, the Germans were held at Moscow, and in the same week came the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Quite absurdly, Bárdossy declared war on the USA without consulting either Horthy or the cabinet.

On 23 July 1941, the day between the beginning of the treacherous German attack and the severance of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and Hungary, Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov, conversing in a tone uncommon in diplomacy, intimated to the Hungarian ambassador in Moscow and through him to Horthy and his supporters that the Soviet Union had no demands or requests – other than neutrality – to make of Hungary, and stood ready to support its claims to Transylvania. But Hungary was deceived by provocation into entering Hitler’s war with the Soviet Union and, consequently, with the Allied Powers, soon to be joined by the USA.

(to be continued… )

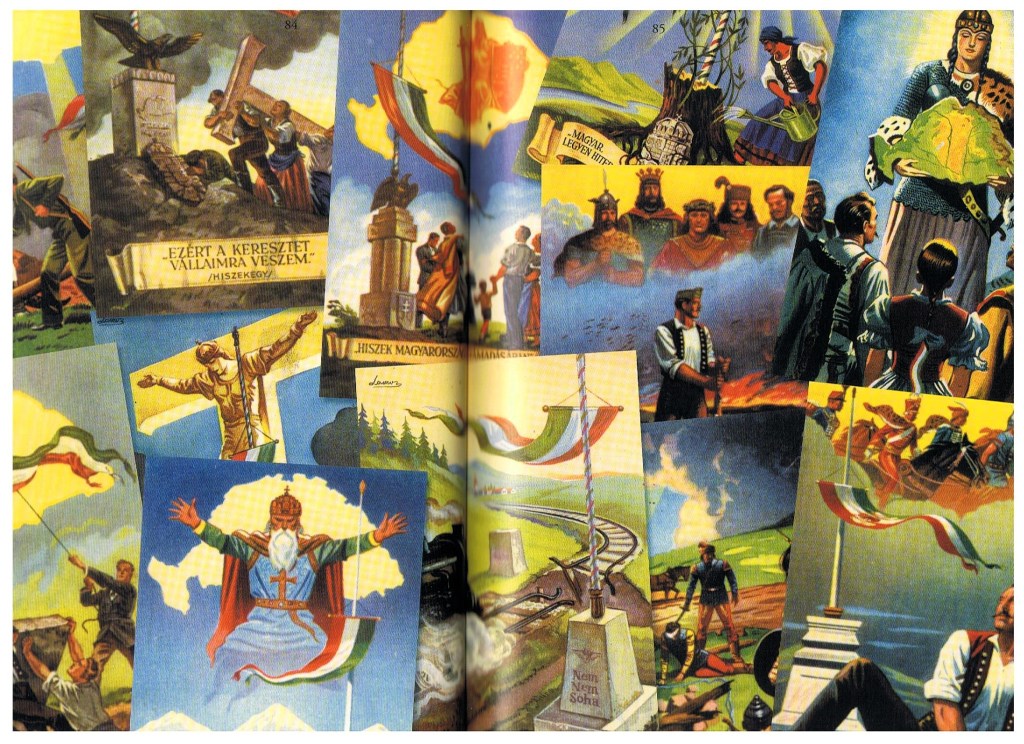

Gallery: