Chapter Two: All Roads Led to Sarajevo – How Austria-Hungary Went to War in 1914:

The Trigger:

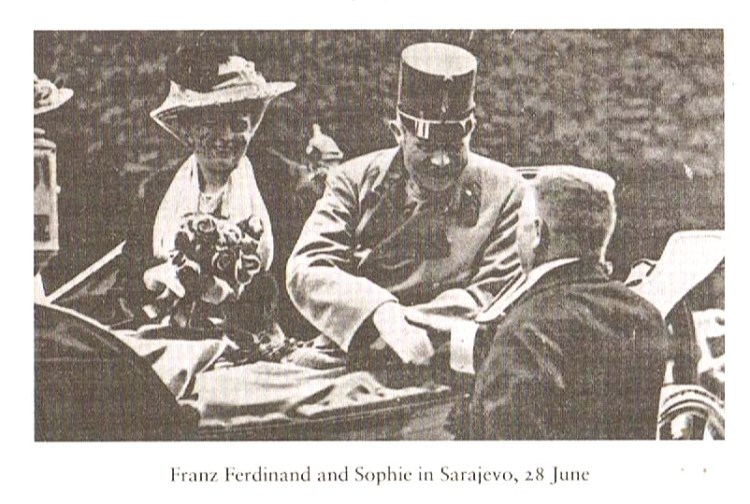

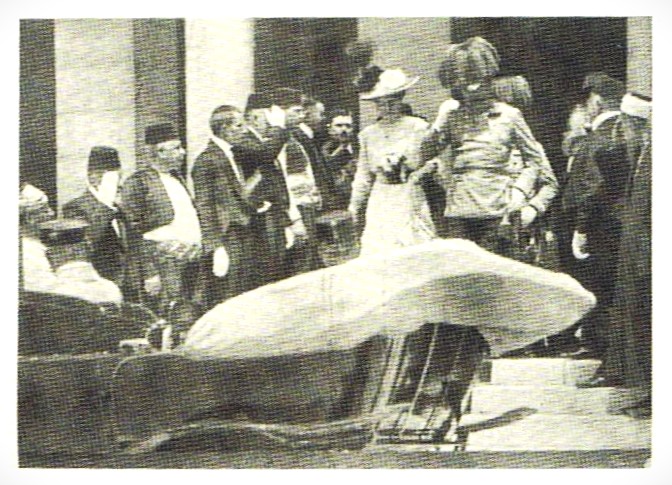

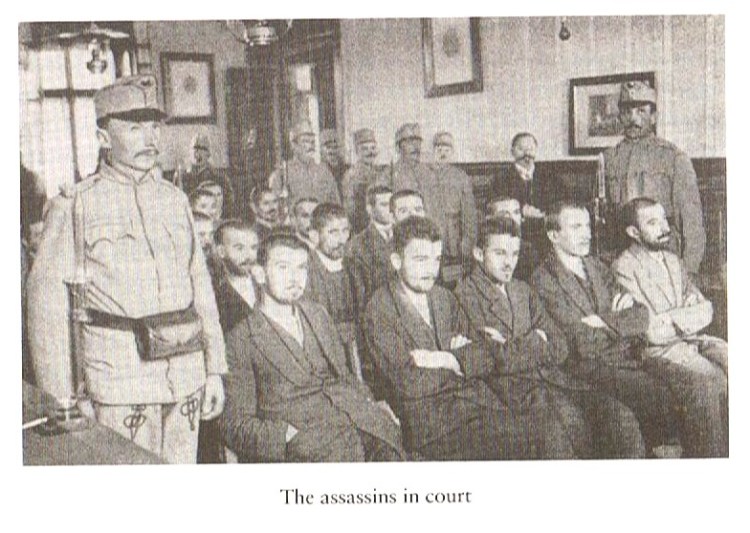

On 28th June 1914, the heir to the Austrian and Hungarian thrones, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, paid a visit to Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, which had been occupied by Austria-Hungary in 1878, and annexed by Emperor Franz Josef in 1908. The visit was intended to display grandeur to the citizenry of the province, but Franz Ferdinand was not on good terms with its Governor, Oskar Potiorek, of Slovene origin, who had been given the job as consolation for not being Chief of the General Staff because the archduke had preferred Conrad von Hötzendorf in that role. Potierok disliked social events and loathed his own chief of staff, Colonel Böltz, and hardly communicated with him. Security for the visit was handed over to a firm of Budapest private detectives. Seven young Serb conspirators picked up training and weapons in Belgrade, and one of them, Gavrilo Princip, succeeded in assassinating the archduke. Although the object and victim of the attack, together with his wife, Franz Ferdinand himself was one of the few men in the empire who foresaw what disasters would come from a Great War and had he survived, he would certainly have refused to take the empire in one. But killed he was, in an extraordinary chapter of accidents which have been pawed over repeatedly ever since.

Princip, too young to be executed, was imprisoned in the fortress of Theresienstadt, where he died before the war ended. The prison psychiatrist asked him if he had any regrets. He answered, ‘If I had not done it, the Germans would have found another excuse.’ He was probably right in this judgment. Looking back through the prism of two world wars, we may judge that both began with ridiculously disproportionate causes, or rather ‘catalysts’. The tensions that had evolved over four or five decades were released by a trigger. Still, by then Franz Josef and his ministers and advisors in Vienna could see no other answer to the South Slav problem than a demonstration of might against the radical nationalists. Only Franz Ferdinand and his staff disagreed, but ironically, the assassin’s bullets at Sarajevo removed that particular objector to war.

Chess-players & Sleep-walkers:

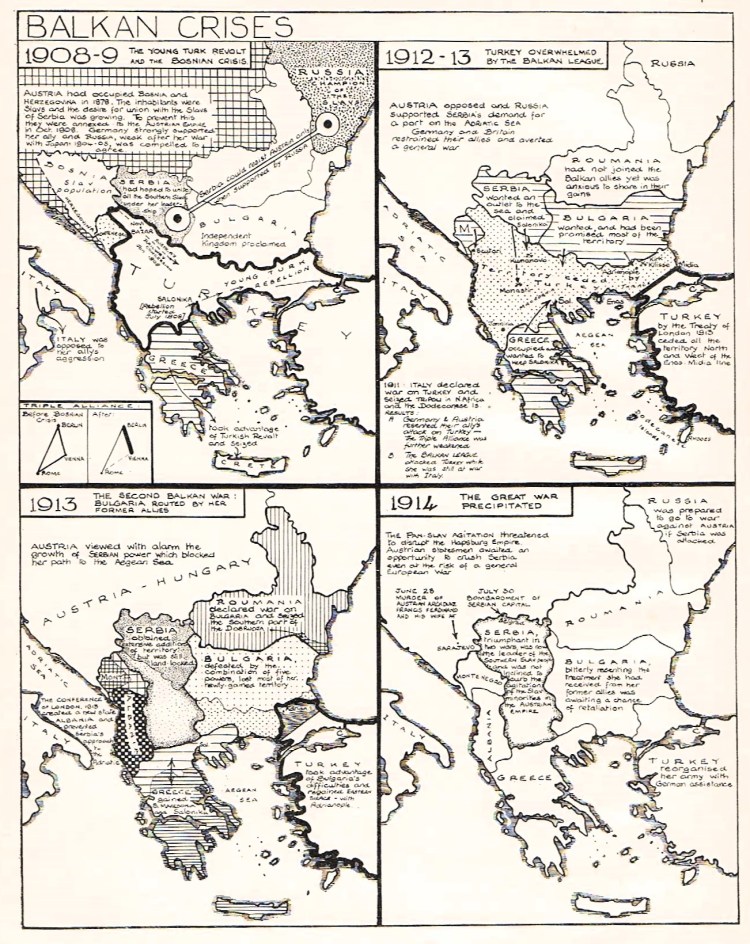

To properly contextualise the causes and catalysts of 1914, it is necessary to retrace the steps of all the participants over half a century or more. After the ejection of the Austrians from Italy in 1859 and Germany in 1866, the Balkan region became by default the pre-eminent focus of Austro-Hungarian foreign policy. This narrowing of focus coincided with an era of growing volatility across the Balkan peninsula. The underlying problem was the waning of Ottoman authority in south-eastern Europe which created and exposed a zone of tension between the two remaining great powers with an interest in the region. Russia and Austria-Hungary felt historically entitled to exercise hegemony in areas where the Ottomans withdrew. The House of Habsburg had traditionally been the guardian of Europe’s eastern gate against the Turks. In Russia, the ideology of pan-Slavism asserted a natural commonality of interest between the emergent Slavic (especially Eastern Orthodox) nations of the Balkan peninsula and the patronage of St Petersburg. The Ottoman retreat also raised questions about the future control of the straits controlling the access to and from the Black Sea, an issue of acute strategic importance to Russian diplomats. At the same time, the emerging Balkan states had conflicting interests and objectives of their own. Christopher Clark (2011) has characterised the Austro-Russian rivalry as like chess players hoping with each move to cancel out or diminish the opponent’s advantage (p. 78).

Until 1908, cooperation, self-restraint, and the demarcation of informal spheres of influence ensured that the dangers implicit in this state of affairs were contained. In the revised Three Emperors’ League treaty of 1881 between Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany, Russia undertook to ‘respect’ the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia-Hercegovina authorised in the 1878 Treaty of Berlin and the three signatories agreed to ‘take account’ of each other’s ‘interests in the Balkan peninsula’. Further Austro-Russian understandings in 1897 and 1903 reaffirmed the joint commitment to the Balkan status quo. The complexity of Balkan politics was such, however, that maintaining good relations with Austria-Hungary was not enough to ensure tranquillity. During the reign of the Austrophile, Milan Obrenovíc, Serbia remained a docile partner in Vienna’s designs, acquiescing in its claims to regional hegemony. Vienna, in return, supported Belgrade’s claim to be recognised as a kingdom in 1882 and promised diplomatic support if Serbia chose to expand south into Ottoman Macedonia. As the Austro-Hungarian foreign minister, Count Gustav Kálnoky von Köröspatak, informed his Russian counterpart in the summer of 1883, that good relations with Serbia were essential to the success of the empire’s Balkan policy.

In 1883, the King of Serbia created a commotion in Vienna by proposing to abdicate and allow the empire to annex his kingdom. At a meeting in the Austrian capital, he was dissuaded from this course of action and sent back to Belgrade. Kálnoky later explained to President Taaffe that a flourishing and independent Serbia suits our intentions… better than the possession of an unruly province. (Memorandum cited in Bridge, From Sadowa to Sarajevo, p. 149.) Only months later, however, King Milan suddenly and unexpectedly invaded neighbouring Bulgaria, Russia’s client state. The resulting conflict was shortlived because the Serbian army was easily beaten back by the Bulgarians, but great power diplomacy was required to prevent this temporary incursion from ruffling the feathers of the Austro-Russian détente. Milan’s son, however, declared intemperately and publicly in 1899 that the enemies of Serbia are the enemies of Austria-Hungary, raising eyebrows in St Petersburg and causing considerable embarrassment in Vienna. But he was also tempted by the advantages of a Russophile policy; by 1902, after the death of his father, King Alexandar was energetically suing for Russian support; he even declared to a journalist in St Petersburg that the Habsburg monarchy was ‘the arch enemy of Serbia’. There was therefore little regret in Vienna at the news of Alexandar’s premature death, although the politicians there were as shocked as everyone else by the brutality with which he and his line were exterminated.

Only gradually did it become clear to the Austrians that the regicide of June 1903 marked a real break. The foreign ministry in Vienna hastened to establish good relations with the usurper, Petar Karadjordjevic, whom they mistakenly viewed as an Austrophile. Austria-Hungary became the first foreign state to formally recognise the new Serbian régime. But it soon became clear that the foundations no longer existed for a harmonious relationship between the two neighbours. The management of political affairs passed into the hands of men openly hostile to the dual monarchy and the policy-makers in Vienna studied with growing concern the nationalist statements of the Belgrade press, now freed from government restraints. In September 1903, the Austrian minister in Belgrade reported that relations between the two countries were ‘as bad as possible’. Vienna rediscovered its moral outrage at the regicide and joined the British in imposing sanctions on the Karadjordjevic court. Hoping to profit from this loosening of the Austro-Serbian bond, the Russians moved in, assuring the Belgrade government that Serbia’s future lay in the west, on the Adriatic coastline, and urging them not to renew their long-standing commercial treaty with Vienna.

At the end of 1905, these tensions broke out into open conflict with the discovery in Vienna that Serbia and Bulgaria had agreed on a ‘secret’ customs union. Austria-Hungary’s demand early in 1906 that Belgrade repudiate the union proved counter-productive; among other things, it transformed the Bulgarian union, which had been a matter of indifference to most Serbs, into a major platform of Serbian national opinion. The general outlines of the 1906 Crisis have been set out above. Still, it is worth noting here that what worried the politicians in Vienna was not so much the commercial significance of the customs union, but the political logic underlying it. What if the Serbo-Bulgarian trade alliance were merely the first step in the direction of a ‘league’ of Balkan states hostile to the empire and receptive to promptings from St Petersburg? It is easy to write this question off as prompted by Austro-Hungarian paranoia, but the policy-makers of the dual monarchy were not far off the mark: the customs union was, in fact, the third of a sequence of secret alliances between Serbia and Bulgaria, of which the first two were already clearly anti-imperial in orientation; a Treaty of Friendship and a Treaty of Alliance, signed in Belgrade in 1904. Vienna’s fear of Russian involvement in these was well-founded, as it turned out. St Petersburg was now clearly working towards a Balkan alliance, notwithstanding the Austro-Russian détente and the disastrous war with Japan. On 15 September 1904, the Russian ambassadors in Belgrade and Sofia were secretly and simultaneously presented with copies of the Treaty of Alliance by the foreign ministers of Serbia and Bulgaria respectively.

One difficult aspect of the Austro-Hungarian Balkan policy was the deepening inter-penetration of domestic and foreign issues. These issues were most likely to become entangled in the case of those minorities for whom there was an independent ‘motherland’ outside the boundaries of the empire. This included the three million Romanians in the Duchy of Transylvania. Due to the nature of the dual monarchy, there was little Vienna could do to prevent the oppressive Hungarian cultural policies from alienating the neighbouring Romanian kingdom, a political partner of great strategic value in the region. Yet it proved possible, at least until 1910, to insulate the empire’s relations with the kingdom from the impact of domestic tensions. The government of the kingdom, an ally of Austria and Germany, made no effort to foment or exploit ethnic discord in Transylvania. However, this could not be said for the Kingdom of Serbia after 1903 and its relations with the disparate Serbs within the empire. Just over forty per cent of the population of Bosnia-Hercegovina were Serbs, and there were large areas of Serbian settlement in Vojvodina in southern Hungary and smaller ones in Croatia-Slavonia. However, no such sovereign external nation-state existed for the Czechs, Slovenes, Poles, Slovaks, and Croats.

After the regicide of 1903, Belgrade stepped up the pace of irredentist activity within the empire, focusing particularly on Bosnia-Hercegovina. In February 1906, the Austrian military attaché in Belgrade, Pomiankowski, summarised the problem in a letter to the chief of the General Staff. He declared that it was certain that Serbia would number among the empire’s enemies in a future military conflict. The problem was less the attitude of the Serbian government and more the ultra-nationalist orientation of the political culture as a whole. even if a ‘sensible’ government were in control, Pomiankowski warned, it would be in no position to prevent the all-powerful radical chauvinists from launching ‘an adventure’. More important than Serbia’s ‘miserable army’ however, was:

“The fifth-column work of the Radicals in peacetime, which systematically poisons the attitude of our South Slav population and could, if the worst came to the worst, create very serious difficulties for our amy”

Pomiankowski to Beck, Belgrade, 17 February 1906, cited in Günther Kronenbitter, Krieg im Frieden, Die Führung der k.u.k. Armee und die Grossmachtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns 1906-14 (Munich, 2003), p.327.

The ‘chauvinist’ irredentism of the Serbian political forces came to occupy a central place in Vienna’s assessments of its relations with Belgrade. By the summer of 1907, the Austrian Foreign Minister, von Aehrenthal conveyed a sense of how relations had deteriorated since the regicide. Under King Milan, the Serbian crown had been strong enough to counteract any ‘public Bosnian agitation’, but since the events of 1903, everything had changed. It was not just that King Petar was too weak to oppose the forces of ultra-nationalism, but rather that he had begun to exploit the national movement to consolidate his own position. For their part, the empire’s diplomats left the king in no doubt that Austria-Hungary regarded its occupation of Bosnia-Hercegovina as ‘definitive’. In the summer of 1907, the Foreign Minister instructed his envoy to Belgrade not to be put off by the usual official denials, such as:

‘The Serbian Government strives to maintain correct and blameless relations, but it is in no position to hold back the sentiment of the nation, which demands action, etc. etc.’

Cited in Solomon Wank (ed.), Aus dem Nachlaus Aehrenthal, 1885-1912, Graz, 1994.

This official instruction captures the salient features of Vienna’s attitude to Belgrade: a belief in the primordial power of Serbian nationalism, a visceral distrust of its leading statesmen, and a deepening anxiety over the future of Bosnia, concealed behind its natural air of imperial superiority.

Thus, the stage was set for the annexation of Bosnia and Hercegovina in 1908. There had never been any doubt, either in Vienna and Budapest or in the capitals of the other great powers, that the occupation of 1878 was intended to be permanent. In one of the secret articles of the renewed Three Emperors’ Alliance of 1881, there had been an explicit statement that Austria-Hungary had the right to annex these provinces at whatever moment she shall deem opportune and this claim was repeated at intervals in the Austro-Russian diplomatic agreements. Nor was it contested in principle by Russia, though St Petersburg reserved the right to impose conditions when the moment for a change of status arrived. The advantages of a formal annexation were obvious enough: It would allow Bosnia and Hercegovina to be integrated more fully into the political fabric of a provincial parliament. It would create a more stable environment for inward investment and, most importantly, would signal to Belgrade and the empire’s minority Serbs the permanence of Austria-Hungary’s possessions.

Yet, in 1905 the empire found itself dogged by bitter infighting between the Austrian and Hungarian political élites over the administration of the armed forces. By 1907, Aehrenthal had begun to favour a tripartite solution to the monarchy’s problems; the two dominant power centres within it would be supplemented by a third entity incorporating the southern Slavs (Croats, Slovenes, and Serbs). This was a proposal that enjoyed a considerable following among the southern Slav élites, especially the Croats, who resented being divided between Cisleithania, the Kingdom of Hungary, and the province of Croatia-Slavonia, also ruled from Budapest. If only Bosnia-Hercegovina were fully incorporated into the structure of a reformed trialist monarchy, Aehrenthal’s hope was that this third entity would provide an internal counterweight to the irredentist activities of Belgrade.

The clinching argument for annexation was the Young Turk Revolution that broke out in Ottoman Macedonia in the summer of 1908. The Young Turks forced the Sultan in Constantinople (Istanbul) to proclaim a constitution and the establishment of a parliament. They planned to subject the Ottoman imperial system to a root-and-branch reform. Rumours circulated to the effect that the new Turkish leadership would shortly call general elections throughout the Ottoman Empire, including the areas occupied by Austria-Hungary, which currently possessed no representative organs of their own. Hoping to capitalise on the uncertainties created by these rumours, an opportunist Serb-Muslim coalition emerged in Bosnia calling for autonomy under Turkish suzerainty. The danger was now that an ethnic alliance within the province might join forces with the Turks to push the Austro-Hungarians out.

To forestall such complications, Aehrenthal moved quickly to prepare the ground for annexation. The Ottomans were bought out of their nominal sovereignty, and the Russians had no objection to the formalisation of Austria-Hungary’s status in Bosnia-Hercegovina provided St Petersburg received something in return. The Russian foreign minister, Alexandr Izvolsky, supported by Tsar Nicholas II, proposed that the annexation should occur in exchange for Austria-Hungary’s support for improved Russian access to the Turkish straits. Izvolsky and Aehrenthal were both after the same thing: gains that would be secured through secret negotiations at the expense of the Ottoman Empire and in contravention of the Treaty of Berlin. Despite these preparations, Aehrenthal’s announcement of the annexation on 5th October 1908 triggered a major European Crisis. Izvolsky denied ever having reached an agreement at Schloss Buchlau in Moravia and subsequently denied that he had been advised in advance of their September meeting. He demanded a formal conference to clarify the status of Bosnia-Hercegovina, but Aehrenthal continued to evade this demand while the crisis dragged on for months and escalated as Serbia, Russia and Austria-Hungary mobilised and counter-mobilised their armies. The situation was only resolved by the ‘St Petersburg Note’ of March 1909, in which the Germans demanded that the Russians at least recognise the annexation and urge Serbia to do likewise. Chancellor Bülow warned that if they did not do this, events would ‘take their course’. This hinted not just at the possibility of an Austrian war on Serbia, but, more importantly, at the possibility that the Germans would release the documents proving Izvolsky’s complicity in the original annexation deal. Izvolsky immediately backed down.

Aehrenthal has traditionally carried much of the blame for the annexation crisis, but this may not be an accurate assessment. Certainly, the foreign minister’s manoeuvres lacked transparency. He used the tools of the old diplomacy; confidential meetings, the exchange of pledges and secret bilateral agreements, rather than attempting to resolve the annexation issue through a round table conference involving all the signatories of the Treaty of Berlin. This made it easier for Izvolsky to claim that he, and by extension Russia, had been hoodwinked by the ‘slippery’ Austro-Hungarian minister. Yet the evidence suggests that the crisis took the course that it did because Izvolsky lied most extravagantly to save his job and reputation.

Russian & Turkish Dimensions:

The Russian foreign minister had made two serious errors of judgement. He had assumed, firstly, that London would support his demand for the opening of the Turkish Straits to Russian warships. He had also greatly underestimated the impact of the annexation on Russian nationalist opinion. According to one account, he was initially perfectly calm about the annexation when the news came through to Paris on 8th October. It was only during his stay in London a few days later, when the British proved uncooperative and he heard of the press response in St Petersburg, that he realised his error, panicked, and began to reconstruct himself as Aehrenthal’s dupe.

In any case, the Bosnian crisis represented a significant turning point in Balkan geopolitics. It devastated what remained of Austro-Russian readiness to collaborate on resolving Balkan questions; from this moment onwards, it would be much more difficult to contain the negative energies generated by the internecine conflicts among the Balkan states. It also alienated its closest neighbour and ally, the Kingdom of Italy. There had long been friction between the kingdoms, especially over minority rights in Dalmatia and Croatia-Slavonia, and political rivalry in the Adriatic was a further bone of contention. The annexation prompted calls for Italy to be compensated, kindling Italian resentments to a heightened pitch of intensity. In the last years before the outbreak of the Great War, it became increasingly difficult to reconcile Austro-Hungarian and Italian objectives along the Adriatic coast. The Germans were initially noncommital on the annexation question, but they soon rallied to Austria-Hungary’s support, which had the desired effect of dissuading the Russian government from attempting to extract further capital out of the annexation crisis. However, in the longer run, it reinforced the sense in both St Petersburg and London that Austria was the satellite of Berlin, a perception that would play a dangerous role in the crisis of 1914.

In Russia, both the government and public opinion interpreted the annexation as a brutal betrayal of the understanding between the two powers, an unforgivable humiliation and an unacceptable provocation in a sphere of vital interest. In the years that followed the crisis, the Russians launched a programme of military investment so substantial that it sparked a European arms race. There were also signs of a deeper Russian political involvement with Serbia. In the autumn of 1909, the Russian foreign ministry appointed Nikolai Hartwig, a fiery fanatic in the old Slavophile tradition, to the Russian embassy in Belgrade. Once in office, Hartwig worked hard to push Belgrade into taking up a more assertive position against Vienna, sometimes exceeding the instructions of his managers in St Petersburg. Therefore, The annexation crisis further worsened the relations between Vienna and Belgrade, exacerbated by political conditions inside the dual monarchy. For several years, the Austro-Hungarian authorities had been observing the activities of the Serbo-Croat coalition, a political faction that had been emerging from within the Croat Diet at Agram (Zagreb), capital of Hungarian-ruled Croatia-Slavonia, in 1905. After the diet elections in 1906, the coalition secured control of the Agram administration, embracing a ‘Yugoslav’ agenda seeking a closer union of the South Slav peoples within the empire, and fought long battles with the Hungarian authorities over issues such as the requirement that all state railway officials should be able to speak Magyar. What really worried the Austro-Hungarians was the suspicion that some or all of the deputies of the Agram administration might be operating as a fifth column for Belgrade.

Escalating Eastern Tensions & Equilibrium:

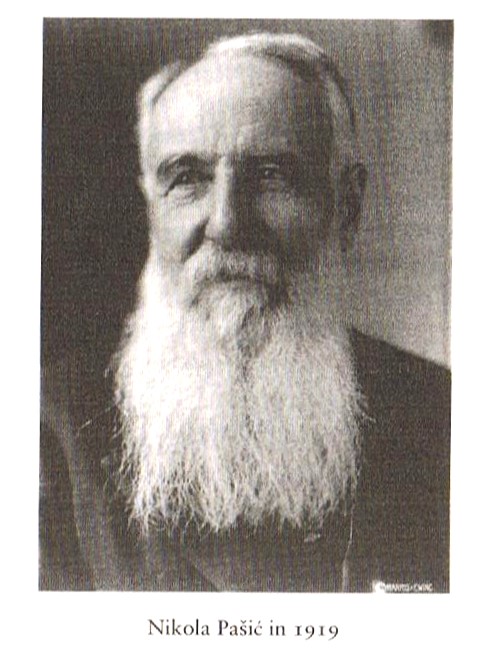

During the crisis of 1908-9, these apprehensions escalated to the point of paranoia. In March 1909, just as Russia was backing down from a potential confrontation over Bosnia, the Habsburg administration launched an astonishingly inept judicial assault on the Serbo-Croat coalition, charging fifty-three mainly Serb activists with treason for plotting to detach the South Slav lands from Austria-Hungary and join them to Serbia. The treason trial at Agram dragged on for eight months, quickly collapsing into an unmitigated public relations disaster for the government. All thirty-one convictions handed down were subsequently crushed on appeal in Vienna. Quite naturally, these events led to a worsening of diplomatic relations between Vienna, Belgrade and St Petersburg during 1910-1912. Aehrenthal died suddenly from leukaemia in 1912, leaving behind a legacy of bitter personal animosity, especially with Izvolsky, which was identified by the quality press in Vienna, in the aftermath of the Bosnian crisis, as an impediment to the improvement of relations between Austria-Hungary and Russia. After Aehrenthal’s death, Forgách left Belgrade a staunch Serbophobe, remaining on the scene as one of a cohort of officials who helped shape the policies of the Austro-Hungarian foreign ministry. Miroslav Spalajkovic served as the Serbian minister in Sofia and was subsequently transferred to the Serbian legation in St Petersburg. Here his task would be to interpret the intentions of the Tsar and his ministers to the government in Belgrade. Nikolai Hartwig, the new Russian minister, had become Spalajkovic’s close personal friend during his time in Belgrade and subsequently developed an intimate relationship with the Serbian Prime Minister, Nikola Pasic. It was a key factor in the July Crisis of 1914 that so many of its individual actors had known each other for so long. Beneath the surface of many of the key rivalries lurked long-term personal antipathies.

Vienna could, in theory, offset Serbian hostility by seeking better relations with Bulgaria. But pursuing this option also involved finding a way around the border dispute between Bulgaria and Romania. Cosying up to Sofia brought the risk of alienating Bucharest, which was undesirable due to the large Romanian minority in Hungarian Transylvania. If Romania were to turn away from Vienna towards St Petersburg, the minority issue might become a question of regional security. Hungarian politicians and diplomats warned that a ‘Greater Romania’ would pose as great a threat to the dual monarchy as a ‘Greater Serbia’. However, in March 1909, Serbia formally pledged that it would desist from further covert operations against Austro-Hungarian territory and maintain good neighbourly relations with the empire. In 1910, Vienna and Belgrade even agreed on a trade treaty ending the Austro-Serbian commercial conflict. A twenty-four per cent rise in Serbian imports during that year bore witness to improving economic conditions. Austro-Hungarian goods began to reappear on the shelves of shops in Belgrade, and by 1912, the dual monarchy was once again the main buyer and supplier of Serbia. But despite assurances of goodwill on both sides, a deep mistrust continued to affect relations which was difficult to dispel. Although there was talk of an official visit by King Petar to Vienna, it never happened. Citing royal ill-health, the Serbian government moved the visit from Vienna to Budapest, then postponed it and then put it off indefinitely in April 1911. Yet later the same year they pulled off a highly successful visit to Paris.

Behind the scenes, the work to redeem Bosnia-Hercegovina continued. Narodna Odbrana, a Serb cultural organisation, proliferated after 1909 and spilt over into the two provinces. The Austrians stepped up their monitoring of Serbian agents crossing the border while Dragomir Djordjevic, a reserve lieutenant in the Serbian army, combined his ‘cultural work’ with the management of a covert network of Serb informants. He was spotted returning to Serbia for weapons training in October 1910. In a report filed on 12 November 1911, Forgách’s successor in Belgrade as Austro-Hungarian minister, Stefan von Ugron zu Abránfalva, notified Vienna of the existence of an association supposedly existing in officer circles that was currently the subject of press comment in Serbia. At this point, ‘nothing positive’ was known about the organisation, except that it called itself the Black Hand and was chiefly concerned with regaining the influence over national policies that the army had previously enjoyed. Press rumours to the effect that the Black Hand had drawn up a hit list of politicians to be assassinated in the event of a coup against the current government. It appeared that the conspirators planned to use legal means to remove the ‘inner enemies of Serbdom’, and ‘turn with unified force against its external foes’. The Austro-Hungarians recognised that Narodna Odbrana aimed at the subversion of Habsburg rule in Bosnia and ran networks of activists in the Habsburg lands. They presumed that the roots of all Serbian irredentist activity within the empire led back to the pan-Serbian propaganda of the Belgrade-based patriotic networks, but their understanding of the precise nature of the links between these networks and the Black Hand was poor. Nevertheless, the key elements that would shape Austro-Hungarian thought and action following the events at Sarajevo were all in place by the spring of 1914.

The Balkan Wars destroyed Austria-Hungary’s security position on the Balkan peninsula and created a bigger and stronger Serbia. The kingdom’s territory expanded by over eighty per cent. During the Second Balkan War, the Serbian armed forces under their supreme commander General Putnik displayed impressive discipline and initiative. The Habsburg government had often adopted a dismissive tone in its discussions of the military threat posed by Belgrade. In a telling metaphor, Aehrenthal had once described Serbia as a ‘rascally boy’ pinching apples from the Austrian orchard. A General Staff report of 9th November 1912 expressed surprise at the dramatic growth in Serbia’s striking power. Improvements to the railway network, the modernisation of weaponry and a massive increase in the number of front-line units, all financed by French loans, had transformed Serbia into a formidable combatant. Moreover, Serbia’s strength could only be strengthened by the 1.6 million who lived in the territories conquered in the two Balkan Wars. In a report of October 1913, the empire’s military attaché in Belgrade, Otto Gellinek observed that while there was no need for immediate alarm, no one should underestimate the kingdom’s military prowess. Henceforth, it would be necessary when calculating the dual monarchy’s defence needs to match all Serbian front-line units man-for-man with Austro-Hungarian troops.

The question of how to respond to the deteriorating security situation in the Balkans divided the key decision-makers in Vienna and Budapest. Should Austria-Hungary seek some sort of accommodation with Serbia, or contain it by diplomatic means? Should Vienna strive to mend the ruined entente with St Petersburg? Or did the solution lie in military conflict? It was difficult to extract unequivocal answers from the multi-layered networks of the Austro-Hungarian state. The dualist constitution required that the Hungarian prime minister be consulted on questions of imperial foreign policy and the intimate connection between domestic and foreign problems ensured that other ministers and senior officials also laid claim to a role in resolving specific issues. So open was the texture of the imperial system that even quite junior figures – diplomats, for example, or section heads within the foreign ministry – might seek to shape imperial policy by submitting unsolicited memoranda that could on occasion play an important role in focusing attitudes within the policy-making élite. Presiding over it all was the Emperor, whose power to approve or block the initiatives of his ministers was still absolute. But this was a largely passive rather than a proactive role – he responded to, and mediated between the loosely assembled power-centres of the political élite. Against the background of this polycratic system, three figures were especially influential: the chief of the Austrian General Staff, Fieldmarshal Lieutenant Franz Baron Conrad von Hötzendorf; the heir to the Habsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and the joint foreign minister from 1912, Count Leopold von Berchtold.

Under the energetic supervision of a gifted head of personal staff, Major Alexander Brosch von Aarenau, the Military Chancellor was reorganised along military lines; its military information channels served as a cover for political data-gathering and a network of friendly journalists pummeled political opponents and attempted to shape public debates. Processing ten thousand pieces of correspondence per year, the Chancellory matured into a political ‘think tank’, a power centre within the system that some saw as a ‘shadow government’. An internal study of the operations of this ‘think tank’, concluded that its chief political objective was to hinder any ‘possible mishaps’ that could accelerate the ‘national federal fragmentation’ of the Habsburg Empire. At the heart of this concern about political fragmentation was a deep-seated hostility to the Hungarian élites who controlled the eastern half of the empire. The Archduke and his advisers were outspoken critics of the dualist political system forged in the aftermath of Austria’s defeat at the hands of Prussia in 1866. This arrangement had, in Franz Ferdinand’s eyes, one fatal flaw: it concentrated power in the hands of an arrogant and politically disloyal Magyar élite, while at the same time marginalizing and alienating the other nine Habsburg nationalities. Once installed with his staff at the Lower Belvedere, Captain Brosch von Aarenau built up a network of disaffected non-Magyar intellectuals and experts, and the Military Chancellery became a clearing house for Slav and Romanian opposition to the oppressive minority policies of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The archduke made no secret that he intended to restructure the imperial system after he acceded to the throne. His key objective was to break or diminish Hungary’s hegemony in the eastern part of the monarchy. For a time, Franz Ferdinand favoured strengthening the Slavic element in the monarchy by creating a Croat-dominated (and Catholic) ‘Yugoslavia’ within the empire. It was his association with this idea that aroused the hatred of his Orthodox Serbian enemies. By 1914, however, it appears he had dropped this plan in favour of a far-reaching transformation by which the empire would become a ‘United States of Great Austria’, comprising fifteen member states, many of which would have Slav majorities. By diminishing the status of the Hungarians, the archduke and his advisers hoped to reinforce the authority of the Habsburg dynasty while at the same time rekindling the loyalties of the lesser nationalities. Whatever one thought of this programme, and obviously Hungarians didn’t think much of it, it did identify the archduke as a man of radical intentions whose accession to the throne would bring an end to the habit of muddling through that seemed to paralyse Austrian policy in the last decades before 1914. It also placed the heir to the throne in direct political opposition to the reigning sovereign. The Emperor refused to countenance any tampering with the dualist Compromise of 1867, which he regarded as the most enduring achievement of his own early years in office.

Franz Ferdinand’s most influential ally was the new Habsburg foreign minister, Leopold Count Berchtold von und Ungarschitz, Fratting und Pullitz. Berchtold was a nobleman of immense wealth, an urbane, patrician representative of the landed class that still held sway in the upper reaches of the Austro-Hungarian administration. By temperament cautious, even fearful, he was not an instinctive politician. His willingness to follow a diplomatic career had more to do with his loyalty to the Emperor and to Foreign Minister Aehrenthal than with an appetite for personal power or renown. His reluctance when invited to accept posts of increasing seniority and responsibility was unquestionably genuine. He believed that harmonious relations with Russia, founded on cooperation in areas of potential conflict such as the Balkans, were crucial to the empire’s security and maintaining peace in Europe. He derived great personal pride from being able to play a crucial role in St Petersburg in the consolidation of good relations between the two powers. When Aehrenthal departed for Vienna, Berchtold gladly accepted the post of ambassador, confident in the knowledge that his own views of the Austro-Russian relationship were entirely in step with those of the new minister in Vienna. It was a shock to his system, therefore, to find himself on the front line when Austro-Russian relations took a drastic turn for the worse in 1908.

The Bosnian Crisis & Balkan Wars, 1908-13:

The first eighteen months of Berchtold’s new posting had been relatively harmonious, but the Bosnian Crisis destroyed any prospect of further collaboration with the Russian foreign minister and undermined the policy of détente. Berchtold deeply regretted Aehrenthal’s willingness to risk Russian goodwill for the sake of Austro-Hungarian prestige. In a letter to the minister of 19th November 1908, Berchtold offered an implicit critique of his former mentor’s policy. In light of the pathological escalation of pan-Slav-influenced Russian national sentiment, he wrote, the continuation of the Austro-Hungarian Balkan policy would inevitably have a further negative impact on our relationship with Russia. Recent events had made his work in St Petersburg ‘extremely difficult’, so he closed his letter with a request to be recalled once the situation returned to normal. He remained in St Petersburg until April 1911, but his spell of recuperation was to last only ten months. On 19th February 1912, the Emperor summoned him to Vienna and appointed him Aehrenthal’s successor as minister for foreign affairs. His policy, announced to the Hungarian delegation on 30th April 1912, would be ‘a policy of stability and peace, the conservation of what exists, and the avoidance of entanglements and shocks.’

The Balkan Wars of 1912-13 would test this commitment to breaking point. In the attempt of the Serbian government to secure a swathe of territory connecting their country’s heartland with the Adriatic coast. Successive Serbian assaults on northern Albania triggered a sequence of international crises. The result was a marked deterioration in Austro-Serbian relations. This hostility was reinforced in the autumn of 1913 by dark tidings from the areas conquered by Serbian forces. The Austrian Consul-General Jehlitschka in Skopje submitted reports of atrocities against the Muslim populations of ten villages. These were not spontaneous acts of brutality, he concluded, but rather a cold-blooded and systematic elimination or annihilation operation that appeared to have been carried out on orders from above. Austria-Hungary’s minister in Belgrade was amused to see leader articles in the Viennese press advising the Serbian government to go easy on the minorities and win them over with a policy of conciliation. Such advice, he observed in a letter to Berchtold, might well be heeded in ‘civilised states’. But Serbia was a state where ‘murder and killing have been raised to a system.’ At the very least, these reports underscored in Vienna’s eyes the political illegitimacy of Serbian territorial expansion.

Nevertheless, even a local war between Austria and Serbia did not appear likely in the spring and summer of 1914. The mood in Belgrade was relatively calm that spring, reflecting the exhaustion following the Balkan Wars. The instability of the newly conquered areas and the civil-military crisis that racked Serbia during May gave grounds to suspect that the Belgrade government would be focusing mainly on tasks of domestic consolidation for the foreseeable future. In a report sent on 24th May 1914, the Austro-Hungarian minister in Belgrade, Baron Giesl, observed that although Serbian troop numbers along the Albanian border remained high, there seemed little reason to fear further incursions. Three weeks later, on 16 June, a dispatch from Gellinek, military attaché in Belgrade, struck a similarly placid note. Although the Serbian army was being kept at a heightened state of readiness, there were no signs of aggressive intentions towards either Austria-Hungary or Albania. All was quiet on the southern front.

Yet, on the diplomatic front, the Matscheko Memorandum, drawn up by a senior Foreign Office section chief in consultation with Forgách and Berchtold and passed to the foreign minister’s desk on 24th June, was not an optimistic document. Matscheko notes only two positive Balkan developments: signs of a rapprochement between Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria, which had finally awoken from the Russian hypnosis, and the creation of an independent Albania. Everything else was negative. Serbia, enlarged and strengthened by the Balkan Wars, represented a greater threat than ever before, Romanian public opinion had shifted in Russia’s favour, raising the question as to whether it would break formally with the Triple Alliance and align itself with Russia, and Austria was confronted at every turn by a pro-Russian policy – in Paris, for example. Now that Turkey was no longer a European power, the only purpose behind a Russian-backed Balkan League could be the ultimate dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire itself, at least in its eastern and southern parts.

The memorandum focused on four key diplomatic objectives. First, the Germans must be brought into line with Austrian Balkan policy – Berlin had consistently failed to understand the gravity of the challenges Vienna faced on the Balkan peninsula and would have to be educated towards a more supportive attitude. Secondly, Romania should be pressed to declare where its allegiances lay. The Russians had been courting Romania, hoping to gain a new ally against Austria-Hungary. If the Romanians intended to ally themselves with the Entente, Austria-Hungary needed to know as soon as possible, so that arrangements could be made for the defence of Transylvania and eastern Hungary. Thirdly, an effort should be made to expedite the conclusion of an alliance with Bulgaria to counter the deepening relationship between St Petersburg and Belgrade. Finally, attempts should be made to woo Serbia away from its confrontation policy using economic concessions. However, Matscheko was sceptical as to whether these would be enough to overcome Belgrade’s antipathy.

There was an edgy note of paranoia in the memorandum, in keeping with the mood and cultural style of the early twentieth-century Habsburg empire. But there was no hint in it that any of the imperial diplomats regarded war as imminent, necessary or desirable. On the contrary, the focus was firmly on diplomacy following Vienna’s self-image as the exponent of a ‘conservative policy of peace’. Only Conrad, who had been recalled to the post of chief of staff in December 1912, remained committed to a war policy. But his authority was on the wane and he soon became implicated in a military spy scandal which threatened to end his career. Franz Ferdinand was still the most formidable obstacle to a war policy. The archduke, Conrad was informed, would countenance ‘under no circumstance a war with Russia’; he wanted ‘not a single plum tree, not a single sheep from Serbia, nothing was further from his mind.’ After further angry exchanges at the Bosnian summer manoeuvres of 1914, Franz Ferdinand resolved to rid himself of his troublesome chief of staff. Had the archduke survived his visit to Sarajevo, Conrad would have been dismissed from his post. The ‘hawks’ would have lost their most resolute and consistent spokesman.

In the meantime, there were signs of an improvement in diplomatic relations with Belgrade. The Austro-Hungarian government owned a 51 per cent share of the Oriental Railway Company, an international concern operating on an initially Turkish concession in Macedonia. Now that most of its track had passed under Serbian control, Vienna and Belgrade needed to agree on who owned the track, and who should be responsible for the cost of repairing war damage. Since Belgrade insisted on full Serbian ownership, negotiations began in the spring of 1914 to agree on a price and conditions of transfer. They were still ongoing when the archduke travelled to Sarajevo.

The Widening Circles of Mistrust:

Meanwhile, a transition of profound significance was taking place in the big picture of the European alliance systems: Britain was gradually withdrawing from its century-long commitment to bottle the Russians back into the Black Sea by sustaining the integrity of the Ottoman Empire. To be sure, British suspicion of Russia was still too intense to permit a complete relaxation of vigilance on the Straits. Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Secretary, refused in 1908 to accede to Izvolsky’s request for a loosening of the restrictions of Russian access to the Straits, notwithstanding the Anglo-Russian Convention signed the previous year. Meanwhile, underlying the disarray of the Triple Alliance was a development of far more fundamental importance. In the 1850s, a concert of powers had emerged to contain Russian designs on the Ottoman Empire – the result had been the Crimean War. This group had reconstituted itself in a different form after the Russo-Turkish War at the Conference of Berlin in 1878 and had regrouped during the Bulgarian crises of the mid-1880s, In the opening phase of the Italian war, the Ottoman Empire had sought a British alliance, but London, reluctant to alienate Italy, did not respond. The two Balkan Wars that followed then broke the concert beyond repair.

Right up until 1914, the Ottoman fleet on the Bosphorus was still commanded by a Briton, Admiral Sir Henry Limpus. But the gradual loosening of the British commitment to the Ottoman Empire created by degrees a geopolitical vacuum, into which Germany equally gradually slipped. In 1887, Bismarck had assured the Russian ambassador in Berlin that Germany had no objection to seeing the Russians as ‘masters of the Straits, possessors of the entrance to the Bosphorus and of Constantinople itself.’ However, after the departure of Bismarck in 1890 and the slackening of the traditional tie to Russia, Germany’s leaders sought closer links with Constantinople. Kaiser Wilhelm II made lavishly publicised journeys to the Ottoman Empire, and from the 1890s German finance was deeply involved in Ottoman railway construction, first in the Anatolian Railway, later in the famous Baghdad Railway, begun in 1903, which was supposed to connect Berlin via Constantinople to Iraq. The gradual replacement of Britain by Germany as the guardian of the Straits at this particular pre-war juncture was of momentous importance because it happened to coincide with the sundering of Europe into two alliance blocs. The question of the Turkish Straits, which had once helped to unify the European concert, was now ever more deeply implicated in the antagonisms of the bipolar system.

By the time the Ottomans sued for peace with the Italians in the autumn of 1912, the preparations for a major Balkan conflict were already well underway. At the time of the second Serbian invasion of northern Albania, with Conrad arguing, as usual, for war, Berchtold again agreed in general terms for a policy of military confrontation as did, unusually, Franz Josef. At this point, Franz Ferdinand and Tisza, for widely differing reasons, remained the only doves among the senior Austro-Hungarian decision-makers. The success of the ultimatum in securing the withdrawal of Serbian troops from Albania was itself seen as vindicating a more military style of diplomacy. This more militant attitude coincided with a growing awareness of the extent to which economic restraints were starting to limit Austro-Hungary’s strategic options. The partial mobilisations of the Balkan Wars had imposed immense financial strains on the monarchy. The extra costs for 1912-13 came to 390 million crowns, as much as the entire yearly budget for the Austro-Hungarian army, a serious amount at a time when the economy was entering a recession. Generally, the empire spent very little on its army; of the great powers, only Italy spent less. Austria-Hungary called up a smaller proportion of its population each year (0.27 per cent) than France (0.63 per cent) or Germany (0.46 per cent).

The years 1906-12 had been boom years for the empire’s economy, but very little of this wealth had been siphoned into the military budgets. The empire fielded fewer infantry battalions in 1912 than it had done in 1866, when its armies had faced the Prussians and Italians, despite a twofold increase in population over the same period. ‘Dualism’ was one reason for this, since the Hungarians consistently blocked military expansion, and the pressure to placate the minority nationalities with expensive infrastructural projects was another. To make matters worse, mobilisations in summer and/or early autumn seriously disrupted the agrarian economy, since they removed a large number of the rural workforce from harvest work. In 1912-13, the critics of the government could argue that peacetime mobilisations had incurred huge costs and disrupted the economy without doing much to enhance the empire’s security. Such tactical mobilisations were no longer an instrument the monarchy could afford to deploy. Hence the government’s flexibility in handling crises on the Balkan periphery was gravely diminished. Without the intermediate option of purely tactical mobilisations, decisions to advance would simply become matters of war or peace along extensive fronts.

A crucial precondition for these calculations was the refusal of the other powers – whether explicit or implicit – to allow Austria-Hungary to exercise its right to defend its close-range interests as a great power. The French and British were vague about the precise conditions under which a quarrel between Austria-Hungary and Serbia might arise. French foreign minister, Poincaré, made no effort to define such criteria in his discussions with Ivzolsky, yet pressed for aggressive action in the winter of 1912-13, despite there as yet being no Austrian assault on Serbia. The British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, was a little more ambivalent and sought to differentiate: in a note to ‘Bertie’ in Paris, written on 4th December 1912, the same day as he issued a warning to Lichnowsky, the Russian foreign minister, Grey suggested that British reaction would depend upon ‘how the war broke out’:

‘If Servia provoked Austria and gave her just cause of resentment, feeling would be different from what it would if Austria were clearly aggressive.’

Grey to Bertie, London, 4th December 1912.

However, in an environment as polarised as central Europe in 1912-14, it was difficult to agree on what degree of provocation justified an armed response. The reluctance to integrate Austro-Hungarian security imperatives into the calculation was further evidence of how indifferent the other powers had become to the future integrity of the Dual Monarchy, possibly because they viewed it as the lapdog of Germany with no autonomous geopolitical identity, or because they suspected it of aggressive designs on the Balkan peninsula, or because they accepted the view that the monarchy had run out of time and must soon make way for younger and better successor states. One irony of this situation was that it made no difference whether the Habsburg foreign minister was a forceful character like Aehrenthal or a more emollient figure like Berchtold. The former was aggressive, the latter seemed subservient to Berlin. There was also a rose-tinted ‘Western’ view of Serbia as a nation of freedom fighters to whom the future had already been vouchsafed. In particular, the long-standing policy of French financial assistance continued. In January 1914, another large French loan, amounting to twice the Serbian state budget in 1912, arrived in Belgrade to cover Belgrade’s immense military expenditures. Pasic, simultaneously, negotiated a substantial military aid package with St. Petersburg, claiming (falsely) that Austria-Hungary was delivering similar goods to Bulgaria.

Grey adopted a latently pro-Serbian policy in the negotiations at the London Conference of 1913, favouring Belgrade’s claims over those of the new Albanian state, not because he supported the cause of a Greater Serbia but because he viewed the appeasement of Serbia as a key to the durability of the Entente. The resulting borders isolated half of the Albanian population outside the newly created Kingdom of Albania. Many of those who fell under Serb rule suffered persecution, deportation, mistreatment and massacres. Yet British ministers with links to the Serbian political élite at first suppressed and then downplayed the news of atrocities in the newly conquered areas. When this evidence mounted up, there were intermittent internal expressions of disgust, but nothing strong enough to modify a policy oriented towards ‘keeping the Russians on board’.

Eve of War – The Balkan ‘Trigger’:

Two further factors heightened the sensitivity of the ‘Balkan trigger’. The first was Austria-Hungary’s growing determination to check Serbian territorial ambitions. As already noted, decision-makers in Vienna gravitated towards more hawkish solutions as the situation in the Balkans deteriorated. The mood continued to fluctuate as crises came and went, but there was a cumulative effect: at each point, more key policy-makers aligned themselves with aggressive positions. The politicians also faced financial issues and the challenge of declining domestic morale. As the money ran out for peacetime mobilisations and anxieties grew about their effects on minority national recruits, Austria-Hungary’s repertoire of options narrowed, and its political outlook became less elastic. The last pre-war strategic review, the Matscheko Memorandum, prepared for Berchtold in June 1914, made no mention of military action as a means of resolving the many problems Austria faced on the peninsula.

The Second factor was Germany’s dependency on, and pursuit of, a ‘policy of strength’. This antagonised its neighbours and alienated potential allies, but as long as the policy continued to generate a deterrent effect to exclude the possibility of a combined assault by the opposing camp, the threat of isolation, though serious, was not overwhelming. By 1912, the massive scaling up of Entente military preparedness undermined the long-term feasibility of this approach. But if we conclude that Russia was looking for a preventative war with Germany, then the arguments for avoiding one in 1912, through politically costly concessions would have appeared much weaker. If there was no question of avoiding war, but only of postponing it, then it made sense to accept the war being offered by the antagonist at this point, rather than wait for a repetition of the same scenario under what would probably be much less advantageous circumstances. These thoughts weighed heavily on the German decision-makers during the ‘July Crisis’ that followed the assassinations at Sarajevo.

In the New Year of 1914, the Russian military journal Razvechik, widely viewed as the organ of the Imperial General Staff, offered a bloodcurdling projection of the coming war with Germany:

‘Not just the troops, but the entire Russian people must get used to the fact that we are arming ourselves for the war of extermination against the Germans and that the German empires must be destroyed, even if it costs us hundreds of thousands of lives.’

Cited in Hermann von Kuhl, Der deutsche Generalstab in Vorbereitung und Durchführung der Weltkrieges (Berlin, 1920), p. 72.

Semi-official verbal belligerence of this kind continued into the summer. What particularly alarmed policy-makers in Berlin was that this rhetoric was inspired by the Russian minister of war, Vladimir Sukhomlinov. A further article, We Are Ready, France Must Be Ready Too, appeared in the daily Birzheviia Vedmosti on 13th June and was widely reprinted in the French and German press. It sketched an impressive scenario of the immense military machine that would fall upon Germany in the event of war: the Russian army, it boasted, would soon number 2.3 million men, whereas Germany and Austria-Hungary would have only 1.8 million between them. In addition, thanks to the rapidly expanding strategic railway network, mobilisation times were plummeting. However, Sukhomlinov’s primary purpose was not to terrify the Germans, but to persuade the French government of the scale of Russia’s military commitment to the alliance and to remind his French counterparts that they too must carry their weight. All the same, its effect on German readers was disconcerting. One of these was the Kaiser, who splattered his translation with the usual spontaneous jottings, including the following:

‘Ha! At last the Russians have placed their cards on the table! Anyone in Germany who still doesn’t believe that Russo-Gaul is working towards an imminent war with us … belongs in the Dalldorf asylum!’

Wilhelm II, marginal notes to the translation of the same article, ibid., doc. 2, p. 3.

The German Foreign Secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow, believed that although Russia was not yet ready for war, it could soon ‘overwhelm’ Germany with its vast armies, Baltic Fleet and strategic railway programme. General Staff reports from 27th November 1913 to 7th July 1914 provided updated analyses of the Russian strategic railway programme, accompanied by a map on which the new arterial lines, most with numerous parallel rails, reaching deep into the Russian interior and converging on the German and Austro-Hungarian frontiers, were marked in stripes with brightly coloured ink. Intertwined with these concerns about Russia were doubts about the strength and reliability of Germany’s alliance with Austria-Hungary.

But then, at the end of June, came news of the events in Sarajevo, which were bound to have serious implications for Serbia. The independent kingdom was protected by Russia, and only Germany could help Austria-Hungary in that case. On the 5th of July, the Germans urged their allies to mobilise. They did so because they saw this as the last moment at which they could deal with Russia, and the diary of the German Chancellor’s secretary spells it out: if war now, we will win; if later, not. These diaries of the diplomat and philosopher, Kurt Riezler, Chancellor Bethmann’s closest advisor and confidant, convey the Chancellor’s thinking on 6th July 1914:

‘Russia’s military power growing swiftly, strategic reinforcement of the Polish salient will make the situation untenable. Austria steadily weaker and less mobile…

‘The Chancellor speaks of weighty decisions. The murder of Franz Ferdinand. Official Serbia involved. Austria wants to pull itself together. Letter from Franz Joseph with enquiry regarding the readiness of the alliance to act.

‘It’s our old dilemma with every Austrian action in the Balkans. If we encourage them, they will say we pushed them into it. If we counsel against it, they will say we left them in the lurch. Then they will approach the western powers, whose arms are open, and we lose our last reasonable ally.’

Karl Dietrich Erdmann (ed), Kurt Riezler; Tagbücher, Aufsatze, Dokumente (Göttingen,1972), diary entry, 7 July 1914, pp. 182-3. See also Clark’s note, p. 643.

During a conversation with Riezler the following day, Bethmann remarked that Austria-Hungary was incapable of ‘entering a war as our ally on behalf of a German cause’. (ibid., p. 182) By contrast, ‘war from the east’, born of a Balkan conflict and driven by, in the first instance, Austro-Hungarian interests, would ensure that Vienna’s interests were fully engaged. ‘If war comes from the east, so that we enter the field for Austria-Hungary and not Austria-Hungary for us, we have some prospect of success’. (ibid., diary for 8 July, p. 184). This argument mirrored exactly that of the French policy-makers, that a war of Balkan origin would engage Russia fully in a joint enterprise against Germany. Neither the French nor the German policy-makers trusted their respective allies to commit fully to a struggle in which their own country’s interests were not principally at stake. Now the Germans felt able to tell the Austrians to provoke a war. The Austrian Crown Council deliberated, and the Hungarian premier, István Tisza, alone, spoke against it. The Romanians, he said, would come in, and, in any case, the Empire did not need any more Slavs, such as would accrue if Serbia were crushed.

To be continued…(sources to be listed at the end of the next chapter/appendix).