Introduction:

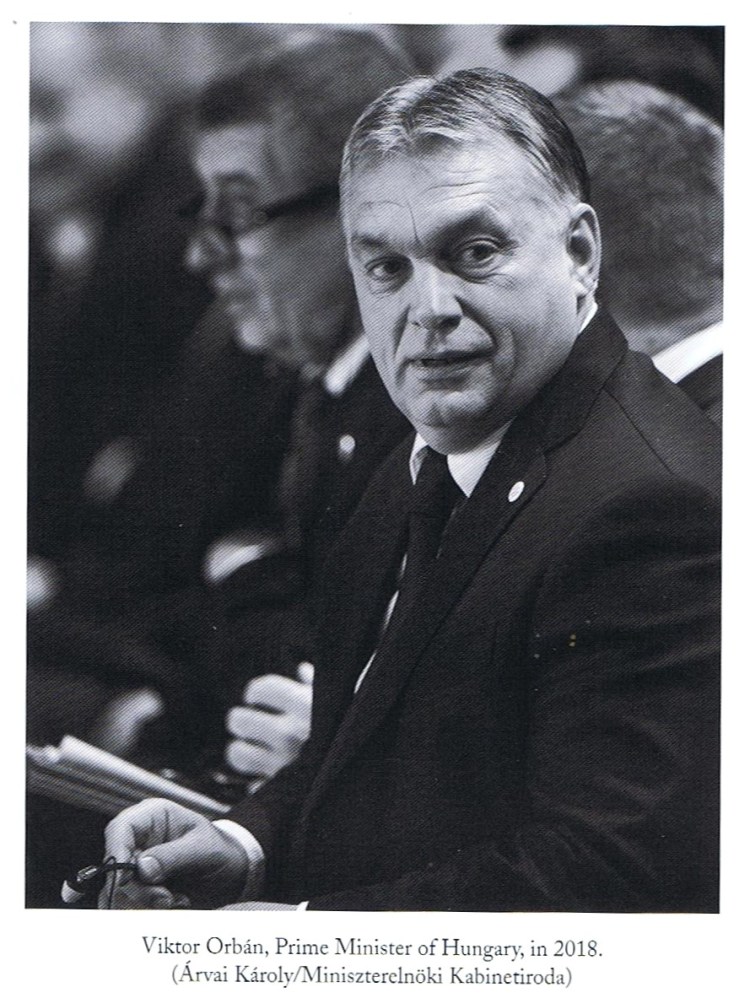

The recent attempted assassination of the Slovak Prime Minister, Robert Fico, reminded many Hungarians, along with other Central Europeans, of the events leading to the outbreak of the First World War which ended with the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Hungary’s loss of two-thirds of its 1914 territories (as part of the ‘Dual Monarchy’ of Austria-Hungary) by the terms of the Treaty of Trianon (1920). Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, wasted little time in blaming this assassination attempt on what he has called ‘the EU’s war strategy’ of supporting Ukraine in its defensive war against Putin’s aggressive invasion of the country. Both Fico and Orbán have consistently opposed NATO sending weapons and armaments to Ukraine, and have prevented those from member countries from transiting through Hungary and Slovakia. Orbán has also consistently resisted the EU’s imposition of economic sanctions on Russia. He has referred to those within Hungary and the rest of Europe who support the EU and NATO in these policies as ‘warmongers’: He has accused European leaders like Macron, Schulz, and Ursula von der Leyen of forming a ‘European War Party’ ahead of the EU elections in June and failing to learn the lessons of ‘the drift to war’ before the two world wars of the last century. My father was born in 1914 and my maternal grandfather in 1900; he was one of only a handful of recruits who survived the 1917 influenza epidemic in camp at Catterick and never made it to Flanders before the war ended. His uncle and elder brother, both named Alfred, joined the Navy. Uncle Alfred died on HMS Vanguard at Scapa Flow in 1916 and Brother Alfred survived, returning to service in the second war, training naval gunners. My wife’s family members survived the Second World War, the Nazi occupation of Hungary and the Holocaust. I was therefore keen to discover more about Hungary’s role in the origins and outbreak of these wars and to make an informed judgment as to whether these events can be described as a ‘drift’ to war and whether the leaders can be accurately described as ‘Sleepwalkers’.

Chapter One: The Dual Monarchy & the Origins of World War I

The Habsburg Empire before & after The Compromise of 1867:

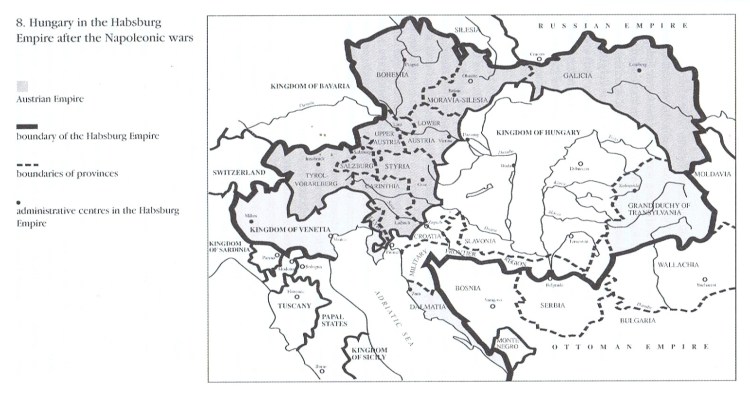

Two military disasters defined the trajectory of the Habsburg Empire in the half-century to its demise. At Solferino in 1859, French and Piedmontese forces prevailed over a hundred thousand imperial troops. Then, at Köningratz on 3rd July 1866, the Prussians destroyed an Austrian army of 240,000 soldiers, ejecting the empire from the ambit of the emergent German nation-state. As a result, Austria became excluded from the German Confederation, which it had hoped to dominate. To the Hungarian premier, Ferenc Deák and his followers this, at first, seemed an undesirable outcome: they had calculated that if Austria had become preoccupied with its ‘Western mission’ again, Hungary would have acquired a better chance to recover its full autonomy within the Monarchy. However, on the other hand, they did not intend to weaken Habsburg power, from which they expected protection against German and Russian expansionism. Without the Austro-Germans, they would find themselves in a rump of the empire in which they were the most numerous ethnic group, but constituting less than half of the whole population. They therefore came to accept the idea that they would be better off in a two-state empire in which the western half would be transformed into a state, like Hungary, under one nation’s leadership. Then the positions of both leading nations in both halves of the empire would be consolidated by lending each other mutual support.

Gradually, Franz Josef himself started to prefer constitutional dualism to the alternatives of retaining the centralised structure and the federal reorganisation of the empire, as suggested by Slav national leaders and Prime Minister Count Richard Belcredi. In addition to Queen Elisabeth, whose pro-Hungarian sentiments have been subject to romantic exaggerations in Hungarian national legends, but were real enough, it was Baron Ferdinand Buest, Imperial Foreign Minister in 1866 and then Prime Minister (February 1867) who finally convinced the Emperor that the domestic precondition of revanche in Germany was compromise with the Hungarians. Thus, the cumulative effect of the military disasters transformed the inner life of the Austro-Hungarian lands as the absolutist Austrian Empire transformed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under the Compromise hammered out in 1867, power was shared between the two dominant nationalities. As Clark has described it,

‘What emerged was a unique polity, like an egg with two yolks, in which the Kingdom of Hungary and a territory centred on the Austrian lands and often called Cisleithania (meaning ‘the lands on this side of the River Leithe’) lived side by side within the translucent envelope of the Habsburg dual monarchy.’

Clark (2012), p. 65.

But first, Buest needed a Hungarian partner to negotiate with. Deák paved the way to the Compromise and had a party in the Hungarian Parliament to push it through, but was determined to remain an eminence grise at most in the new era. The Hungarian delegation that negotiated the Compromise in January and February 1867 was headed by Count Gyula Andrássy, who enjoyed the complete confidence of Deák and the Hungarian liberals, as well as the royal couple, even though he was on the list of émigrés hanged in effigy in 1849. Having returned to Hungary in 1857, he was an experienced politician with an instinctive skill for brilliant improvisations. Andrássy was appointed Prime Minister on 17th February. Besides him, the most important member of the delegation was Eötvös, who represented continuity with 1848 and became Minister of Education and Ecclesiastical Affairs. Liberal commoners as well as aristocratic magnates were represented in Hungary’s third responsible ministry.

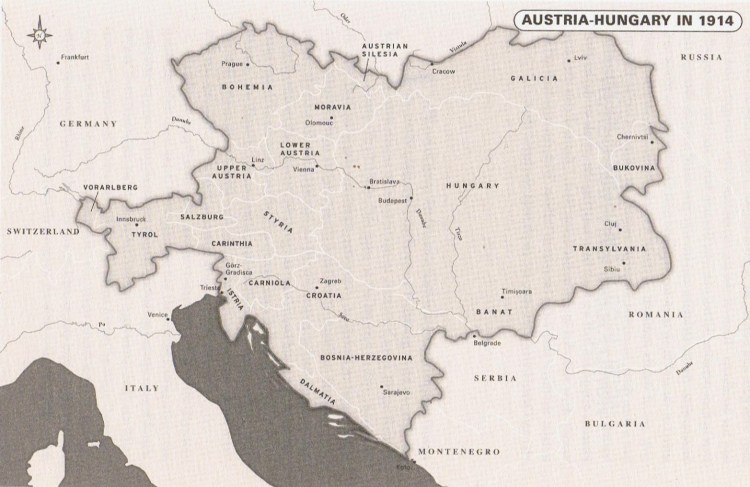

Devised by Ferenc Deák, the Compromise gave Hungary independence while keeping it in the Habsburg Empire; it also gave the kingdom its own government and parliament, with an upper house of dignatories and an elected Lower House, but the emperor as the king of Hungary appointed the government. To satisfy Hungarian demands, Transylvania was also fully absorbed into Hungary, and Hungarian law replaced the Austrian civil code. In June 1867, Franz Josef and Elisabeth were crowned king and queen of Hungary, and she too was invested with the royal sceptre and orb, an honour never before given to a queen of Hungary. That same year, Franz Josef published constitutions for both halves of the empire. From this point onwards, the Habsburg empire comprised two equal parts – a Hungarian part and a part for all the rest, which included the Austrian lands, Bohemia, Polish Galicia, the Adriatic coastline, and so on. The second had no obvious name and was officially known as the Lands and Kingdoms represented in the Imperial Council, and unofficially as ‘this side of Leitha’ (Cisleitha: the River marked Hungary’s western border).

Predictably, Lajos Kossúth, the former Protector of Hungary, in exile since 1849, wrote an open letter, known as the Cassandra letter, to Ferenc Deák, his old associate, in which he claimed that the Dual Monarchy represented a sham independence. Kossúth was one of a minority who were unimpressed by the Compromise. In a series of open letters addressed by ‘the hermit of Turin’ to his countrymen, published on 26th May in a Pest journal, he argued that Deák’s policy culminated in abandoning Hungary’s claim to be an independent state, at a time when the 1866 crisis created the most auspicious circumstances to obtain independence. Köningrátz demonstrated that Austria was a dilapidated structure bound together merely by the Habsburg dynasty and doomed to collapse in the age of the nation-state. The Compromise involved a trap. Hungarian self-determination suffered irreparably from involvement in foreign policies that might be contrary to the nation’s interests, and might also throw it into conflict with the two Great Powers against which Deák sought protection and her neighbouring peoples whose friendship was essential for Hungary’s own wellbeing. Hungary lost the ‘mastery over her future’ and it would never be able to take advantage of the ever more frequently arising occasions to gain complete independence.

Kossuth was right in a very profound and prophetic sense, namely that Hungary’s twentieth-century history rather fatefully verified some of his predictions. At the same time, Deák was undoubtedly also right in pointing out that the ‘expected event’ (that is, the ultimate collapse of Austria) might not occur before it was too late ‘for our harrowed nation’ to take advantage of it. Deák never pretended that the Compromise was the best of all solutions, but he was convinced that it was the best of all possible ones. It corresponded to the social and national relations of power in 1867 and laid the foundations of a political establishment that was to last for half a century. On 8th June, Franz Josef I took the coronation oath on a mound constructed at the Pest side of the Chain Bridge from pieces of earth from all over the country, before being crowned on the Buda side in the Mátyás Cathedral, which had once been a Mosque under Ottoman occupation. It had been restored, and Franz Liszt (see the picture below) composed a Mass for the Coronation; the great aristocracy was present, in ornate national costume, and the master of ceremonies was Count Andrássy, trusted both by the Court and and the Habsburg politicians. Together with the Cardinal Archbishop, he was responsible for placing King István’s Crown on Franz Josef’s head. The Emperor sanctioned the sixty-nine Articles of Compromise four days later. A rebellious nation and an autocratic ruler seemed to have been reconciled and its status had been restored.

In one sense, and in retrospect, the coronation might seem like an act of decolonisation, the first of modern times, with all the pageantry of flags and anthems. At the time it was not thought likely to last. Without an army of its own, Kossuth argued, Hungary would be caught up in the interests of Germany. This was true, but if the new Monarchy could be made to work, it would protect Hungary. The existence of a united imperial army, under dynastic insignia and with German as the language of command, evoked resentment, and was only suffered because a separate Honvéd (along with the Austrian Landwehr) was also set up. The other delicate issue between Vienna and Budapest was the ‘economic compromise’: the customs union, commercial agreement, common currency, postal service, transport system, and the share of the two halves of the empire in the expenditure for common affairs, known as ‘the quota’ (30% in 1867; revised to 36.4% in 1907). To be renegotiated every ten years, the economic compromise was the only flexible element in what was otherwise a politically rigid settlement, one which held out the promise of redressing the supposedly unfavourable aspects of 1867 for both partners. The language of command in the armed forces and the quota system were constant causes for grumbling about the ‘constitutional issue’ (the relationship between the emperor and Hungary), which supplied the terms in which the rather shallow patriotism of the parliamentary opposition to the shape, though not the essence of the Compromise, was expressed through most of the fifty-one years of the Dual Monarchy.

Hungary was now the fourth European country, after Romania, Italy, and Germany, to get a form of national unification between 1859 and 1871. This development ended French hegemony as the new countries became, implicitly at first, part of a German one. In the two generations that followed, Hungary flourished. Where the Compromise went wrong was in Austria, which had been saddled with a centralising parliament with a rigged German majority, and all local grievances could be raised there. Bureaucratic rules were drawn up in such detail that only lawyers could handle them. There were seven thousand of them in the Austrian Empire, compared with 162 in late Victorian Britain. Hungary also developed a workable parliament and a programme of national modernisation.

Nevertheless, the two halves of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, the new official name of the new state in 1868, remained, ‘inseparable and indivisible’. Foreign policy and the army were regarded as ‘common matters’ and were overseen by ‘common ministries’ of foreign affairs and war, to which was added a third ministry of finance, with responsibility for funding the other two. In all other respects, the two governments were separate, with the prime minister of Hungary regarding his counterpart as a ‘distinguished foreigner’. Since Hungary now had its own government, the name of the empire changed from the Austrian Empire to the Austro-Hungarian Empire (or Austria-Hungary for short). This came about, with symbolic significance, because in trade treaties the term ‘Austro-Hungarian Monarchy’ had to be used. The ‘Austro’ referred to all the Habsburg lands, including Hungary, and all imperial officials bore the title kaiserlich-königlich (‘imperial-royal’), referring to all the ‘kingdoms’, including Bohemia and Croatia, later changed to Kaiserlich und königlich, which recognised the special status of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Above the ministries sat the Crown Council, made up of three common ministers, the prime ministers of Hungary and Cisleithania, and whomever Franz Josef chose to invite. The Crown Council was the emperor’s instrument for keeping control of foreign policy and the army. The new ‘dual monarchy’ had parliaments and Cisleithia also had elected diets, but its governance was not parliamentary. The emperor conducted his own foreign policy and military deployments, with minimal parliamentary oversight. Franz Josef also retained the right to legislate by decree, again with few constraints, which meant that he could bypass or substitute for the parliamentary process. He also had the power to dissolve the Vienna parliament, though not the one in Budapest, and to impose ministries without parliamentary approval. To that extent, absolutism survived.

More importantly, the empire survived, but it was not just a matter of finding a constitutional formula to satisfy Hungarian aspirations. Franz Josef was unloved in Hungary, not least for killing the kingdom’s generals, but ‘Sisi’ had the glamour and passion for Hungary that reconciled Hungarians to Habsburg rule. She was their queen, who spoke their language, wore their national dress, and went to hunt in their fields. Back in 1866, she had asked Franz Josef to buy her Gödöllő Palace, to the east of the capital. He had grumpily refused, explaining that ‘in these hard times, we must save mightily.’ The following year, the newly installed Hungarian government led by Count Andrássy bought it for her, as the nation’s gift on her coronation. Andrássy had no doubt of Sisi’s contribution to the 1867 settlement between the monarch and Hungary. However, for the other nationalities of the new Austro-Hungarian Empire, Sisi showed little empathy, being particularly disdainful of Czechs and Italians. However, her inconsistencies and eccentricities should not conceal how her intervention in Hungarian affairs fitted into a larger pattern of queenly conduct. Despite recollections of Maria Theresa and the example of Queen Victoria (1837-1901), there were fewer regnant queens than in previous centuries, and females had been expressly barred from succession in France, Spain, Sweden, and Prussia. Instead, it was as consorts that queens became influential, particularly in rebuilding the monarchy’s image. The closest parallel to Sisi was Queen Alexandra, the consort of Britain’s Edward VII (1901-1910), who was elegant, striking in appearance, and a meddler in politics.

The dualist compromise had many detractors at the time and has had many critics since. In the eyes of ‘hardline’ Magyar nationalists, it was a sell-out that denied Hungarians the full independence they had fought for. At the time, some claimed that Austria was still exploiting Hungary as an agricultural colony. Moreover, Vienna’s refusal to relinquish control over the armed forces and permit the creation of a separate and equal Hungarian army was particularly contentious, with a constitutional crisis over this in 1905 leading to the political paralysis of the Empire. On the other hand, Austrians argued that the Hungarians were freeloading on the more advanced economy of the Austrian lands, and ought to pay a higher share of the empire’s running costs. This conflict was now built into the dual monarchy because the Compromise required the two halves of the imperial system to renegotiate the customs union by which revenues and taxation were shared between them. The Hungarians’ demands increased with every review of the union until there was little left in it to continue to recommend it to the political élites of the other national minorities, who had in effect been placed under the domination of the two ‘master races’. The first post-Compromise prime minister, Gyula Andrássy, captured this aspect of settlement when he commented to his Austrian counterpart, “You look after your Slavs and we’ll look after ours.” (Cited in Alan Sked, The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire, 1815-1914. New York, 1991: p. 190.)

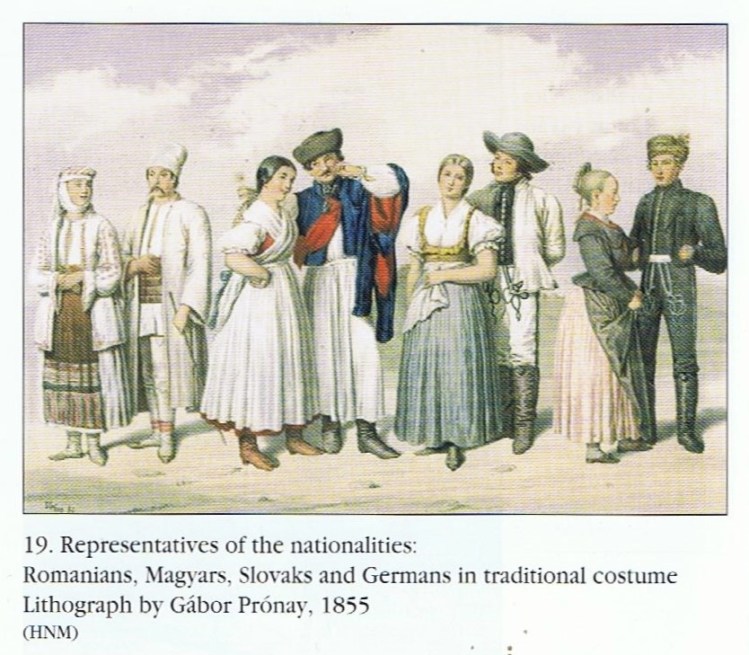

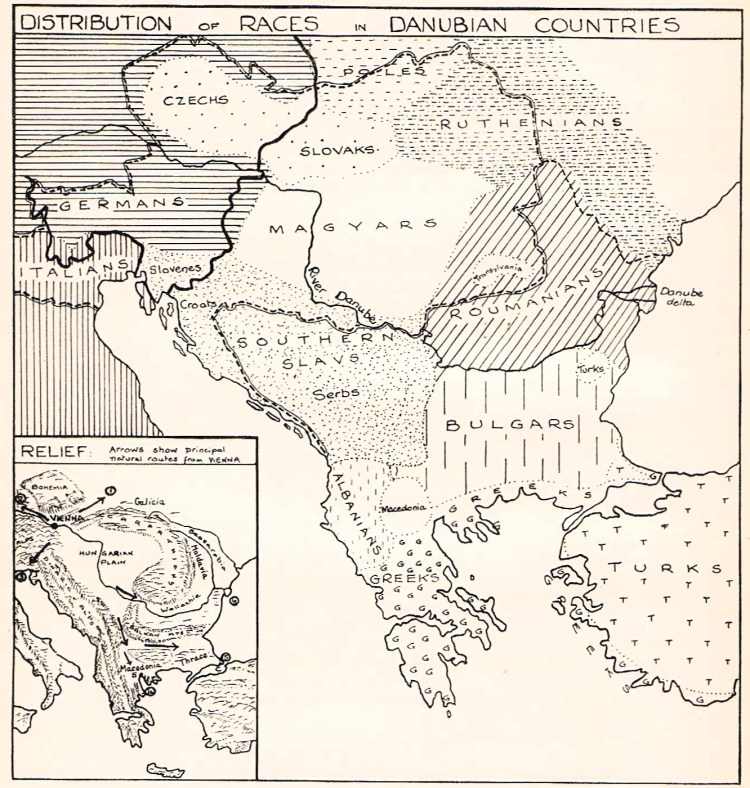

Ethnic Minorities within the Austro-Hungarian Empire of 1868:

The Court wanted revenge against Prussia and looked for alliance with the south German states; a former Prime Minister of Saxony, Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust, who detested Bismarck, was now in charge of foreign affairs. He had pushed for the Compromise because his programme needed taxes and recruits and wanted the Hungarian problem out of the way. The German liberals, thanks to the electoral system, could now dominate a purely Austrian parliament that would not include Hungarian deputies. They were now free to realise their programme, to ignore the Bohemian grandees with their ‘claptrap’ about Bohemian state rights, to put Czech nationalists back in their box, and to cut back the powers of the Church. They meant to create a progressive state, as their counterparts were doing elsewhere, together with the centralising bureaucracy, schools, inheritance taxes, laws, law degrees, and lawyers. The Hungarians, on their side, also wanted wide autonomy so that they could remake the nation in their way, without reference to Austrian centralisers, who were always encouraging the non-Magyar peoples of Hungary to demand rights. Laws were passed from 1867 to 1869 in both parliaments to further establish the new arrangements.

It was well understood in Austria that the Compromise was arguably the only way to preserve the great power status of the Habsburg Monarchy and that in Hungary it not only increased the chances of national survival but also offered a means to partake of that great power status. Though none of the defence ministers, and few in the high command of the armed forces of the Dual Monarchy were Hungarian, thirty percent of the diplomatic corps and four out of ten foreign ministers were subjects of the Hungarian Crown. It is therefore not surprising that, in an age when nationalism was dominant in the attitudes and ambitions of powers great and small, Hungarian nationalists became dazzled by the prospect of governing a demi-empire, whose economic and demographic dynamism might soon shift the intra-imperial balance of power in their favour and even compel the Habsburg dynasty to remove its residence from Vienna to Budapest. On the domestic front, there was certainly a convincing argument in favour of the Compromise that for the two leading nations of the Habsburg monarchy, it did represent a shift from absolutist to liberal representative government, albeit with shortcomings, and for the bulk of the Hungarian liberals some of these made it more attractive than potential alternatives. The strong personal power of the ruler was not one of these, however, and the discretionary powers reserved for Franz Josef maintained his influence in the domestic affairs of both states, whereas his Cabinet and Military bureaus played roles equal to that of the joint ministries in common affairs. Relying on a broad network of unofficial advisors, whose loyalty he could rely on, he exerted a personal influence across a wide range of policy matters.

At the time, Hungary had a population of some thirteen million, mostly either illiterate or literate in a language other than Magyar. There was a country to build, and there was a formula at hand as to how this should be done: it was the ‘Age of Progress’ and classical liberalism, and an accompanying optimism dominated thinking in the 1860s. The British example was plain for travelers to see; Gladstonian liberalism, emphasising the rule of law through parliament was in its heyday and so was the Gold Standard, controlled by an independent central bank. Mass education was important, and the schools of that era were built along Greek and Roman lines. Town planning and public health and hygiene were developing, and doctors were being fully consulted. The ‘limited company’ was becoming increasingly important for commerce, encouraging competition and free trade. Classical liberalism could develop more easily in the framework of nation-states in a decade that started with national unification in Italy and ended with Bismarck’s ceremony at Versailles setting up the German Empire.

At its inception, liberalism in Hungary was the creation of noblemen, largely directed to offset, moderate, or exploit the effects of capitalist development in a predominantly rural society. After the waning of the enthusiasm of the Age of Reform and the Revolution of 1848, the dismantling of feudalism took place. Relations of dependence and hierarchy and the traditional respect for authority were preserved in attitudes. Liberal equality remained a fiction even within the political élite. The Compromise was, after all, a conservative step, checking whatever emancipationalist momentum Hungarian liberalism could still muster. Instead, it became increasingly confined to the espousal of free enterprise, the introduction of modern infrastructure, and, with considerable delay, the secularisation of the public sphere and the regulation of state-church relations. Political remained in the hands of the traditional élite, with which newcomers were assimilated, with roughly eighty percent of MPs permanently drawn from the landowning classes. The franchise, extending to about six percent of the population throughout the period, was acceptable at its beginning, but grossly anachronistic by its end in comparison with much of the rest of Europe. Since most rural districts fell under the patrimony of local magnates and their groups, elections were, as a rule, ‘managed’ and there was large-scale patronage at all levels of administration. Hungary’s political liberalism during the time of Kalman Tisza’s premiership from 1875 to 1890 resembled that of England during Walpole’s ‘whig oligarchy’ of a century and a half earlier. Yet, since the Hungarian parliament was largely independent of the crown, it was ‘more free’ than any other east of the Rhine.

The development of European nation-states required strong national armies, and the example for building these was Prussian. Instead of taking recruits on an indenture of twenty-five years, Prussia had instituted a system of conscription, giving peasant boys three or more years’ training, after which they went into a reserve that could be called up in wartime. This had the great advantage of making the conscripts feel part of the nation. Austria-Hungary introduced conscription in 1868, and Russia in 1874. The Habsburg Empire still counted as a great power with a large and newly reformed army, which also enabled it to cooperate to keep the peace.

It was in these circumstances that the Hungarians took their place within the Habsburg state; Gyula Andrássy became Minister for Foreign Affairs in 1871, and Hungarians had more than their due share of ambassadors and ministers. In 1867 there was an air of euphoria in Budapest as a cabinet of magnates took office. At this time many of the great aristocrats took their national role very seriously, following the example of the British House of Lords, which produced many experts in economics and social reform. In Hungary, Count Lónyay turned out to be an excellent Finance Minister. The English journalist Henry Wickham Steed, who wrote a classic on the Habsburg Monarchy, had reservations about Hungary, but he did notice the rise in intelligence that occurred as the Danube steamer moved from Vienna, with its smug aristocracy, to Budapest.

Gyula Andrássy was the first Prime Minister, and among his first tasks was to make a new capital. The Chain Bridge had linked Buda and Pest, and these two, with Óbuda, were conjoined in 1873 as Budapest, with a powerful mayor, strongly supported by commercial interests. The new Hungary was self-consciously liberal and adopted various arrangements accordingly. Now that there was a proper Hungarian finance ministry, and now that laws and courts guaranteed investment, Austrian capital flowed in. The city’s situation, with the hills of Buda on one side of the Danube, and the plain of Pest on the other, was magnificent, and the roads were laid out sensibly with two concentric rings of boulevards, Andrássy and Rákóczi, cutting across them. The intersection of the great boulevard (Teréz) and Andrássy Avenue was an eight-sided square, the Oktogon, with fashionable cafés, and beyond it the avenue was studded with enormous villas, often occupied by embassies. The opera house was added in 1884, and there were endless theatres, as the city’s cultural life showed much vigour. In the earlier period, the architecture tended to copy the Austrian styles, but after 1890a distinctly Hungarian note was struck as both Budapest and several provincial cities were given ‘Secessionist’ (Art Nouveau) makeovers. By 1900, Budapest was heading to become a million-strong city, and much of it was a building site. As the country’s showcase capital, it was a dramatic triumph.

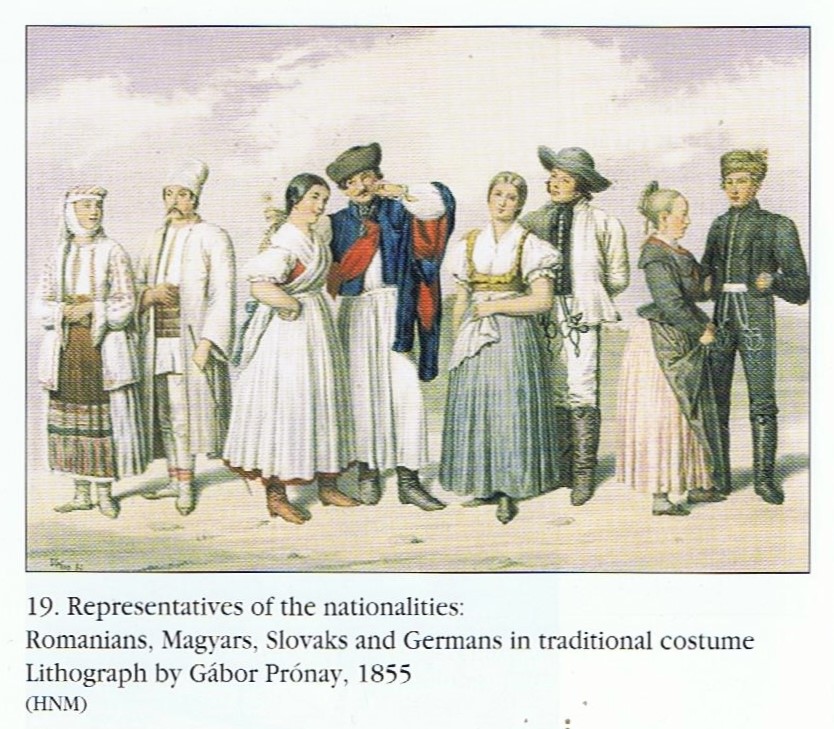

Ethnic Minorities in Imperial Hungary in the Nineteenth Century:

The particular engine of growth was the railway, which eventually made the fortunes of the estate holders. If they had a station near their lands, they could load agricultural produce, mainly grain, and sell it to the ‘captive’ Austrian markets. Proto-industrialisation meant food processing, particularly flour production, and distilling; then came true industrialisation with the growth of textiles and machinery. Austrian Germans and Czechs made up a quarter of the skilled artisans and railwaymen, while the overwhelming majority of Magyars were peasants. In 1900, five million of them were without land, seven million had some land, a third of whom had less than the seven acres needed for subsistence. The new Hungary was therefore dominated by estate owners, magnates of the Eszterházy-Károlyi class in the Upper House, or gentry with middling-sized estates who occupied most parliamentary seats. This was a gentlemen’s parliament, with clubs where men could meet informally. In the first years, under Andrássy, enlightened laws were passed like those of 1868 concerning the non-Magyar minorities, providing them with schools and law courts, which were rewards for the way they had accepted the Compromise. József Eötvös did much for education, especially teacher training. An attempt was made to curb the power of the counties: now that Austrian interference was no longer to be expected, that autonomy, so often associated with pig-headed provincialism, would just be a nuisance for governments.

Besides the many-sided tensions involved in the settlement of Austro-Hungarian relations, others arose from the limited blessings of constitutionalism and did not satisfy those citizens of Austria and Hungary who did not belong to either of the two leading nations. In the Austrian sphere, ‘dualism’ was unacceptable to the Czechs, who either demanded the federal reorganisation of the empire, or hoped for ‘trialism’, and could not be placated by the mere transfer of the Czech coronation insignia from Vienna to Prague. The less ambitious claim of autonomy voiced by the Poles of Galicia was refused, lest it should provoke Russian resentment. Austro-German hegemony was thus preserved in Austria, just as Hungarian supremacy survived in Hungary.

The case of the Croats was unique, similar to that of the Czechs beyond the Leitha on account of the ‘historical legitimacy’ of their claims of self-government. After the Compromise, their status was put on a new footing in the Hungarian-Croat constitutional agreement (Nagodha) of 1868. Like the Austro-Hungarian Compromise, it was a treaty of union, but unlike its counterpart, this was a union of unequal partners. Croatia was acknowledged as a ‘political nation with a separate territory, and an independent legislature and government in its domestic affairs.’ However, the latter were confined to internal administration, the judiciary, and educational and ecclesiastical affairs. As regards the common affairs of the empire as a whole, Croats were represented by six members of the Hungarian delegation. In the common affairs of Hungary and Croatia, the forty-two deputies of the Croatian Sabor in the Hungarian parliament constituted a minority that could be easily outvoted. Also, while the Ban of Croatia was responsible for the state sabor, his appointment by the monarch required the Hungarian government’s approval, thus restricting Croatian autonomy. Although the agreement secured important elements of statehood and a broad range of opportunities to develop national cultural and political institutions, it is little wonder that the Croatian Sabor had to be dissolved repeatedly before a pro-Hungarian majority could be secured to get the Nagodba voted through.

This was still far more than the other nationalities felt they received in what was at that time, ironically, the only comprehensive piece of legislation in Europe apart from Switzerland that addressed the respective status of ethnic groups within the polity, and a remarkably liberal one. Although the endeavour to satisfy the ‘reasonable’ demands of the nationalities was a frequent theme in public discourse on the eve of the Compromise. Law XLIV of 1868 became established on the principle that ‘all Hungarian citizens constitute a nation in the political sense, the one and indivisible Hungarian nation’, that is, on the fiction of a Magyar nation-state on the Western European model. It denied the political existence, and thus the claims to collective rights and political institutions, of the national minorities, for whom the assertion that ‘every citizen of the fatherland … enjoys equal rights, regardless of the national group to which he belongs’ was meager compensation. At the same time, in granting individual rights the law was thoroughly liberal, even surpassing in some respects the demands of the nationalities themselves. It gave extensive opportunities for the use of their native tongues in the administration, at courts, in education, and in religious life; the right of association made it possible to establish cultural, educational, artistic, or economic societies and schools using any language; and the law even required the state to promote primary and secondary schooling in the mother tongue and the participation of the ethnic minorities in public service.

The Repolarisation of Europe, 1887-1907:

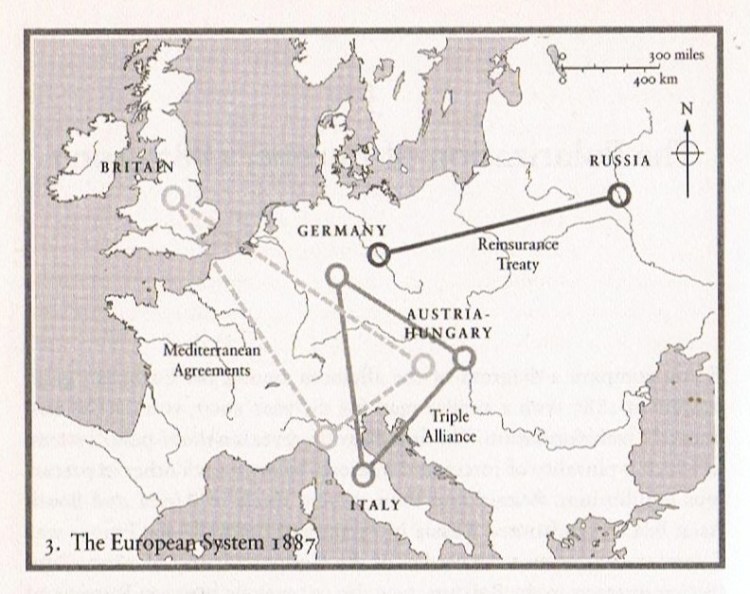

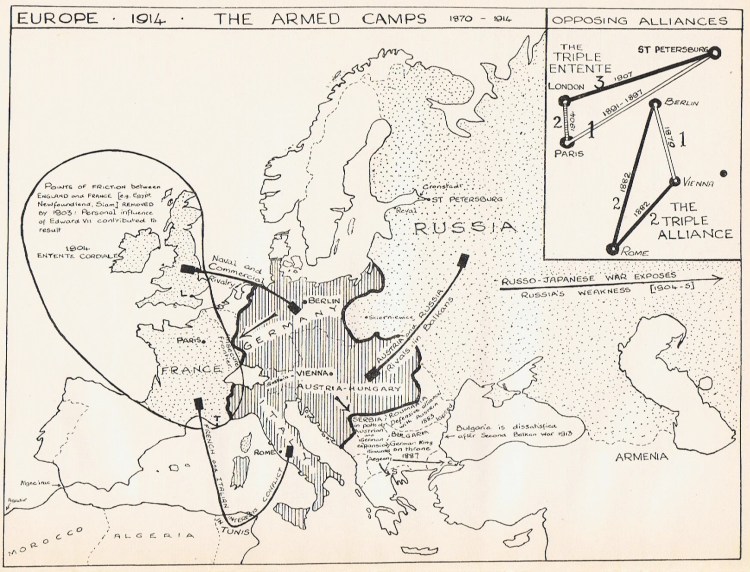

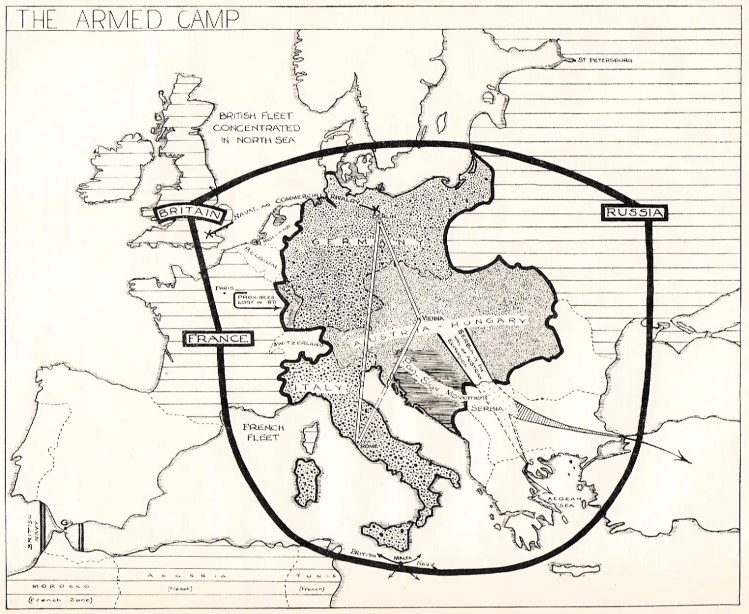

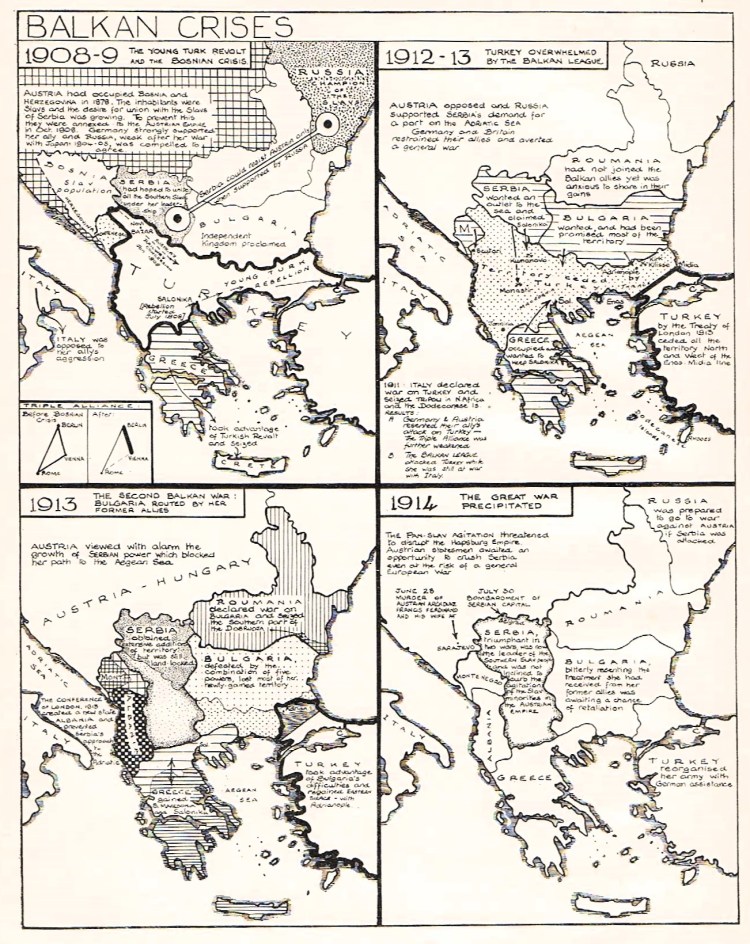

By comparing the diagrammatic maps above and below for 1887 and 1907, the outlines of a transformation can be discerned. The first map shows a multi-polar system, in which a plurality of forces and interests balance each other in a precarious equilibrium. The conflicting interests in the Balkans gave rise to tensions between Russia and Austria-Hungary, Italy and Austria were rivals in the Adriatic and quarreled intermittently over the status of Italophone communities within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There were also rivalries and tensions between Britain, France, Italy, and Germany over northern Africa. These pressures were held in check by the patchwork of the 1887 System. The Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (20th May 1882) prevented the tensions between Rome and Vienna from breaking into open conflict. The (defensive) Reinsurance Treaty between Germany and Russia (18th June 1887) contained articles deterring either power from seeking its fortunes in war with another continental state and insulated the Russo-German relationship against the fallout from Austro-Russian tensions. However, both also agreed that neutrality would not apply if Germany attacked France or Russia attacked Austria-Hungary. The Russo-German link also ensured that France would be unable to build an anti-German coalition with Russia. Britain was loosely tied into the continental system by the Mediterranean Agreement of 1887 with Italy and Austria – an exchange of notes rather than a treaty, whose purpose was to thwart French challenges in the Mediterranean and Russian ones in the Balkans or Turkish Straits.

By 1907, the picture had changed utterly into one of a bipolar Europe organised around two alliance systems. The Triple Alliance was still in place, though Italy’s commitment to it had weakened considerably. France and Russia were conjoined in the Franco-Russian Alliance (drafted in 1892 and ratified in 1894), which stipulated that if any member of the Triple Alliance should mobilise, the two signatories would ‘at the first news of this event and without any previous agreement being necessary,’ mobilise immediately the whole of their forces and deploy them ‘with such speed that Germany shall be forced to fight simultaneously on the East and on the West’. It would be some years before these loose alignments tauten into the coalitions that would fight the First World War in Europe, but the profiles of two armed camps were already visible by 1908.

The polarisation of Europe’s geopolitical system was a crucial pre-condition for the war that broke out in 1914. At the same time, though, it is almost impossible to see how a crisis in Austro-Serbian relations, however grave, could have dragged all the major powers into a continental war. The bifurcation into two alliance blocs did not cause the war; indeed, it did as much to mute as to escalate the conflict in the pre-war years. Yet without the two blocs, the war could not have broken out in the way it did. The bipolar system structured the environment in which crucial decisions were made. To understand how that polarisation took place, it is necessary to answer four interlinked questions: Why did Russia and France form an alliance against Germany in the 1890s? Why did Britain decide to throw in its lot with that alliance? What role did Germany play in bringing about its own encirclement by a hostile condition? To what extent can the structural transformation of the alliance system account for the events that brought war to Europe and the world in 1914?

Looking after the Slavs:

At first, the opponents of the Nationalities’ Law (XLIV) of 1868 criticised its shortcomings, but later they mainly complained because it was increasingly neglected by the Hungarian authorities. Its major drawback was that it contained no guarantees. Contrary to the spirit of Eötvös and Deák, their successors interpreted the concept of the equality of all Hungarian citizens meant that all non-Magyars who assimilated with Magyars would be considered as equal. From the 1880s on, Magyarisation was no longer merely ‘encouraged with all legally permissible means’, but also enforced with some means that evaded or violated the law of 1868. The relationship between the two halves of the empire, the archaisms of the political system, and the nationalities’ question were ‘time bombs’ that the Compromise had placed in the structure of dualist Hungary. Nevertheless, it took a long time, and the effect of international events, for these bombs to explode. Dualism in Hungary is generally reckoned to have been in a crisis during the whole of the second half of the period of the Monarchy, yet the stirrings on the ‘constitutional issue’ were not sufficient to shake it, and the dynamism of economic and cultural progress did much to blunt the edge of the social and the nationality issues from the 1890s through to the 1910s. As a result, the inertia of the peculiarly- modernised Magyar old régime lasted only until its military defeat in the First World War. For these reasons, the tension-ridden era also had an atmosphere of ‘perma-crisis’.

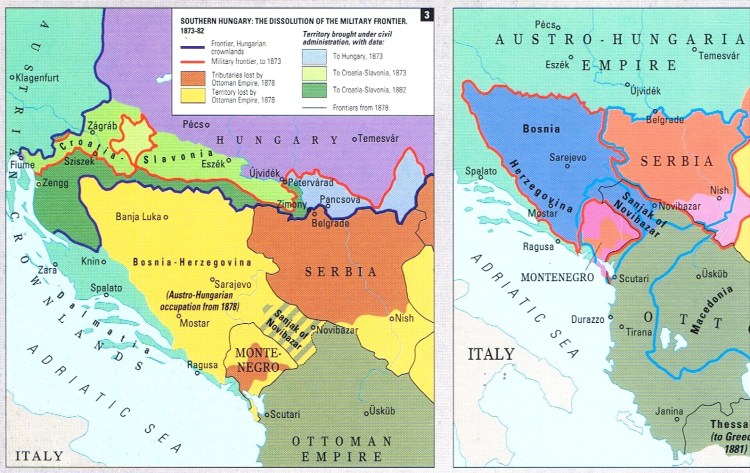

The most significant international events of the period revolved around the independent Balkan states, especially Serbia, and their impact on the Slav nationalities in the southern and eastern parts of the dual monarchy. Debates on internal economic issues in Austria-Hungary took place against a background of seemingly permanent unrest in the Balkans. In 1873, urged by Bismarck who wanted to surmount the diplomatic isolation of Germany resulting from its previous wars, and contrary to the personal intentions of Andrássy who had hoped to use the Habsburg Monarchy to prevent the expansion of Russia, the Three Emperors League was concluded. Not even after the outbreak of an anti-Ottoman uprising in Hercegovina and Bulgaria in 1875 brought the conflicting interests of Russia and Austria-Hungary to the surface. After the defeats of the revolts and the intervention of Serbia and Montenegro in their favour by the Turks, the two powers defined and separated their interests in protracted negotiations, as a result of which Russia could also count on the neutrality of Austria-Hungary in the war it declared on the Ottoman Empire in 1877. However, Russian arms proved too successful, and the Russians were deterred from marching on Constantinople by the appearance of the British fleet. In March 1878 they concluded the Peace of San Stefano, practically ending Ottoman rule in the Balkans and creating Greater Bulgaria, which was unacceptable to any of the Great Powers.

It was on the insistence of Andrássy that the Berlin Congress convened in July 1878 to revise the settlement in the Balkans. Russia was forced to make concessions: Bulgaria’s growth was checked, while the full independence of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro was acknowledged, and Austria-Hungary was entrusted with the occupation and administration of Bosnia-Hercegovina. The diplomatic gain could only be made real on the ground by a three-month campaign with several thousand casualties. This gave rise to intense debate in Austria-Hungary, with some politicians demanding annexation rather than mere occupation and others being concerned about a further increase in the Slav element in the population of the Dual Monarchy. Although in 1881, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia signed a secret agreement guaranteeing the status quo in the Balkans, Russia no longer figured in the diplomatic imperial schemes. The cornerstone of its foreign policy was the Dual Alliance with Germany in 1879, expanded to the Triple Alliance with the inclusion of Italy in 1882. There was also a network of Russian agreements with the Balkan states (Serbia in 1881 and Romania in 1883) that ensured the Monarchy’s hegemony in the peninsula. As for Bosnia-Hercegovina, it was relegated to the status as the province of the Common finance minister and was pacified in the early 1880s when that post was occupied by the Hungarian Béni Kállay, an expert in southern Slav relations. However, through its expansion in the Balkans, the empire got entangled in a web from which it was never to escape. The occupation was immediately and immensely unpopular in Hungary and, in the face of uproar in parliament, PM Kalman Tisza’s cabinet resigned, though Tisza himself was retained in office by the monarch until 1890.

As Christopher Clark has written in his recent book Sleepwalkers (2012), Serbia’s commitment to the redemption of its lands, coupled with the predicaments of its exposed location between two land empires, endowed the foreign policy of the Serbian state with… distinctive features (Sleepwalkers: 24). The first of these was the indeterminacy of geographical focus, by which Cook meant that the principle of commitment to a Greater Serbia did not indicate where exactly the process of redemption should begin. There were various alternatives: Vojvodina, in the Kingdom of Hungary; Ottoman-controlled Kosovo; Bosnia and Hercegovina, never part of Serbia’s empire but containing a large Serbian minority (43 percent of the 1878 population), or Macedonia in the south, also still under Ottoman rule. The mismatch between the vision of ‘unification’ and the meager resources available to the Serbian state meant that Belgrade policy-makers could only respond opportunistically to rapidly changing conditions on the Balkan peninsula. As a result, Serbian foreign policy swung like a compass needle between 1844 and 1914, from one point on the state’s periphery to another.

The logic of these opportunistic oscillations was, as often as not, reactive. In 1848, when the Serbs of Vojvodina rose up against the Magyarising policies of the Hungarian revolutionary government, the Serbian government chose to assist them with volunteer forces. In 1875, all eyes were on Hercegovina, where Serbs had risen against the Ottomans under their military commander and future king Petar Karadjordjevic. After 1903, following an abortive local uprising against the Turks, there began intensified interest in ‘liberating’ the Serbs of Macedonia. In 1908, when the Austrians formally annexed Bosnia and Hercegovina, having occupied them since 1878, these annexed territories became the main priority for Serbian nationalists. Still, by 1912-13, Macedonia once more topped their agenda.

Serbian foreign policy had to struggle with the gap between the visionary nationalism that dominated the country’s political culture and the complex ethnopolitical realities of the Balkans. Kosovo was, and still is, at the centre of Serbian mythology, but it was not, in ethnic terms, a purely or even mainly Serb territory. Muslim Albanian speakers have been in the majority there since at least the eighteenth century, although the exact population of ‘Old Serbia’ (comprising Kosovo, Metohija, Sandzak, and Bujanovac) is unknown. Many of the Serbs whom Vuk Karadzic counted in Dalmatia and Istria were, in fact, Croats, who had no wish to join a greater Serbia. Bosnia and Hercegovina, two provinces under Hungarian occupation, contained a combined majority of Catholic Croats (20%) and Bosnian Muslims (33%). The mismatch between national visions and ethnic realities made it highly likely that realising Serbian objectives would be a violent process. Some statesmen met this challenge by trying to package these within a more generous ‘Serbo-Croat’ political vision encompassing the idea of multi-ethnic collaboration.

The last decades before the outbreak of the Great War were increasingly dominated by the struggle for national rights among the empire’s eleven official nationalities. Besides the Germans, Hungarians, and indigenous Slav minorities, these also included Poles and Italians. How these challenges were met varied between the two halves of the empire. The Hungarians dealt with nationalities’ problems as if they didn’t exist. The result was that the Magyar deputies, although representing just over 48 per cent of the population, controlled over 90 percent of the parliamentary seats. The three million Romanians in Transylvania, the largest of the kingdom’s national minorities, comprising fifteen percent of its population, held only five of its four hundred seats. Furthermore, as already noted, from the late 1870s, the Hungarian government pursued a campaign of aggressive Magyarisation through which education laws imposed the use of the Magyar language on all state and church schools and even kindergartens. Teachers were required to be fluent in Magyar and could be dismissed if they were found to be ‘hostile to the state’. This degradation of language rights was underwritten by harsh measures against ethnic minority activists. As also already noted, Serbs from Vojvodina in the south, Slovaks from the northern counties, and Romanians from Transylvania did occasionally collaborate in pursuit of minority objectives, but with little effect, since they could muster only a few mandates.

In the Austrian lands, by contrast, successive administrations tampered endlessly with the political system to accommodate minority demands. Franchise reforms in 1882 and 1907 (when virtually universal male suffrage was introduced) went some way towards leveling the political playing field. At the same time, however, these democratising measures merely heightened the potential for national conflict, especially over the sensitive question of language use in public institutions such as schools, courts, and administrative bodies. So intense did the nationalities’ conflict become that in 1912-14 multiple parliamentary crises crippled the legislative life of the monarchy. The Bohemian Diet had become so difficult for the Austrians that in 1913 their prime minister, Count Karl Stürgkh, dissolved it, installing an imperial commission to run the province. Czech protests against this brought the imperial (Cisleithanian) diet to its knees in March 1914, so Stürgkh dismissed this too, and it was still suspended when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia in July so that Cisleithania’s was in effect being run by an absolutist administration when war broke out. Meanwhile, in Hungary in 1912, following protests in Zagreb and other southern Slav cities against an unpopular governor, the Croatian Diet and constitution were suspended; in Budapest itself, the last pre-war years witnessed the advent of a kind of parliamentary absolutism focused on protecting Magyar hegemony against the challenge posed by minority national opposition and the demand for franchise reform.

Clark has argued, however, that while the apparent chaos in the Austro-Hungarian Empire might appear to support the view that it was a moribund polity, whose disappearance from the political map was merely a matter of time, in reality, the roots of Austro-Hungary’s political turbulence (Clark, 2012: p. 68) were less deep than those appearances suggested. Certainly, there was intermittent inter-ethnic conflict – riots in Ljubliana in 1908 and Czech-German brawls in Prague – but it never came to the levels of violence experienced in the contemporary Russian Empire. And, despite the obvious political turmoil, the Habsburg lands also passed through a last pre-war decade of strong economic growth with a corresponding rise in general prosperity, an important point of contrast with the contemporary Ottoman Empire. Free markets and competition across the empire’s vast customs union stimulated technical progress and the introduction of new products. The scale and diversity of the dual monarchy meant that new industrial plants benefited from sophisticated networks of cooperating industries underpinned by an effective transport infrastructure and a high-quality service and support sector. These economic effects were particularly evident in Hungary. In the 1840s, Hungary had been the ‘larder’ of the empire – 90 percent of its exports to Austria were agricultural products. But by the years 1909-13, Hungarian industrial exports had risen to 44 percent, while the constantly growing demand for cheap foodstuffs from the Austro-Bohemian industrial region ensured that the Hungarian agricultural sector survived in the best of health, protected by the ‘Habsburg common market’ from Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian and American competition.

For the Monarchy as a whole, most economic historians agree that the period 1887-1913 saw an ‘industrial revolution’, or at least a ‘take-off’ into self-sustaining growth, with the usual indices of expansion. In the last years before the world war, Austria-Hungary in general, and Hungary in particular, with an average growth rate of 4.8 percent, was one of the fastest-growing economies in Europe. Even a critical observer like the Times correspondent in Vienna, Henry Wickham Steed, recognised in 1913 that the “race struggle” in Austria was, in essence, a competition for shares within the existing system:

“The essence of the language struggle is that it is a struggle for bureaucratic influence. Similarly, the demands for new Universities or High Schools put forward by Czechs, Ruthenes, Slovenes, and Italians but resisted by the Germans, Poles or other races, … are the demands for the creation of new machines to turn out potential officials whom the political influence of Parliamentary parties may then be trusted to hoist into bureaucratic appointments.”

Henry Wickham Steed, The Hapsburg Monarchy (London, 1919), p. 77.

Each of the two territories had its own parliament, but there was no common prime minister or cabinet. Only foreign affairs and defence were handled by ‘joint ministers’ who were answerable directly to the Emperor. Matters of common interest could not be discussed in a common parliamentary session because that would have implied the inferiority of the Kingdom of Hungary within the ‘dual monarchy’. Instead, an exchange of views took place between ‘delegations’ of thirty deputies from each parliament meeting alternately in Vienna and Budapest.

There was, moreover, slow but discernable progress towards a more equitable policy on nationality rights. The equality of all the subject nationalities and languages in Austria was formally recognised in the Basic Law of 1867. Throughout the last peacetime years of the empire’s existence, the Cisleithian authorities continued to adjust the system in response to national minority demands. The Galician Compromise agreed in the Galician Diet in Lemburg (now Lviv in western Ukraine) in January 1914, for example, ensured a fixed proportion of mandates in an enlarged regional legislature to the under-represented Ruthenes (Ukrainians) and promised the imminent establishment of a Ukrainian university. After that, even the Hungarian administration was showing signs of a change in attitude towards minorities as the international climate worsened. The southern Slavs of Croatia-Slavonia were promised the abolition of extraordinary powers by the Hungarian state and a guarantee of freedom of the press, while a message went out to Transylvania that the government in Budapest intended to grant many of the demands of the Romanian majority in the province.

These case-by-case adjustments to specific demands suggested that the system might eventually produce a comprehensive framework of guaranteed nationality rights. There were signs that the administrations of the dual monarchy were getting better at responding to the material demands of their minorities. Of course, it was the Habsburg state that performed this role, not the beleaguered parliaments. The proliferation of school boards, town councils, county commissions, and mayoral elections ensured that the state intersected with the life of ‘ordinary’ citizens more intimately and consistently than political parties and legislative assemblies. It slowly metamorphosed from a constant instrument of repression into a broker among manifold social, economic, and cultural interests. But most of the empire’s subjects still associated the state primarily as the provider of good government: public education, welfare, sanitation, the rule of law, and the maintenance of a sophisticated infrastructure. This meant that the Habsburg bureaucracy was costly to maintain – expenditure for domestic administration rose by 336 percent during the years 1890-1911. Nevertheless, the memories of this period of civic pride and apparent prosperity lingered long after the empire’s demise and well into the 1920s, when the writer and engineer looked back on the empire in the last peaceful year of its existence as one of …

… white, broad, prosperous streets … that stretched like rivers of order, like ribbons of bright military serge, embracing the lands with the paper-white arm of administration.

Robert Musil, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften. Hamburg, 1978, pp. 32-3.

Finally, Clark points out that most minority activists acknowledged the value of their Habsburg commonwealth as a system of collective security. The bitterness of inter-ethnic conflicts between minority nationalities – Croats and Serbs in Croatia-Slavonia, for example, or Poles and Ruthenians in Galicia, suggested that the creation of separate national entities might cause more problems than it resolved. Moreover, it was difficult to envisage how a patchwork of nation-states would survive without the empire’s protection. In 1848, Czech nationalist historian Palacky had warned that dismantling the Habsburg Empire, far from liberating the Czechs, might provide the basis for ‘Russian universal monarchy’. This argument was echoed in 1891 by Prince Charles Schwarzenberg when he asked a young Czech nationalist:

“If you and yours hate this state, … what will you do with your country, which is too small to stand alone? Will you give it to Germany, or to Russia, for you have no other choice if you abandon the Austrian union.”

Cited in May, Hapsburg Monarchy, loc.cit., p. 199.

Radical Nationalists & Habsburg Patriots:

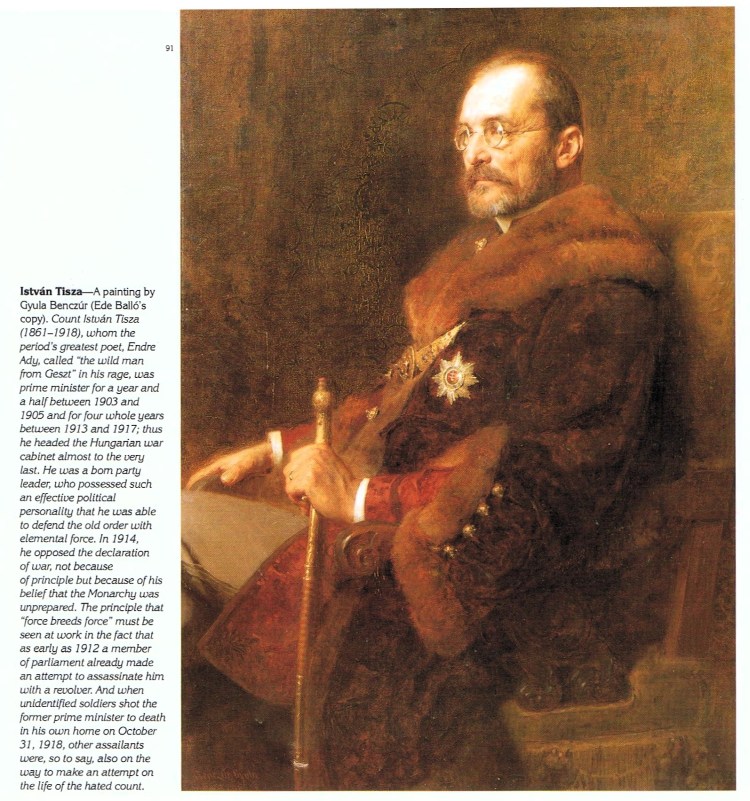

Until 1914, radical nationalists seeking full separation from the empire were few and far between. In many areas, nationalist political groups were counterbalanced by networks of associations – veterans’ clubs, religious and charitable groups, associations of bersaglieri (sharp-shooters) – nurturing various forms of ‘Habsburg patriotism’. The sense of the monarchy’s permanence was personified in the imperturbable, bewhiskered figure of Emperor Franz Josef. But his family had suffered many private tragedies. The Emperor’s son Rudolf had killed himself in a double suicide with his mistress at the family hunting lodge at Mayerling in the Vienna Woods. His wife, Elisabeth (‘Sisi’), much beloved of Hungarians, had been stabbed to death by an Italian anarchist on the shores of Lake Geneva, his brother Maximilian had been executed by Mexican insurgents and his favourite niece had burned to death when her dress caught fire. Throughout all of these, the Emperor remained stoical. He also demonstrated great skill in managing the complex machinery of state, balancing opposing families to maintain an equilibrium of well-tempered dissatisfaction. He involved himself in every phase of constitutional reform, yet by 1914 he had become a force for inertia, backing the Magyar premier, István Tisza, against minority demands for franchise reform. As long as the Kingdom of Hungary continued to deliver the funds and votes Vienna needed, Franz Josef was prepared to accept the hegemony of the Magyar élite in all the lands of its kingdom.

Whatever the concerns about his age (eighty-three) and increasing detachment from the contemporary life of his subjects, the Emperor remained the focus of powerful political and emotional attachments. By 1914, he had been on the throne for longer than most of his subjects had been alive, but it was widely acknowledged that his popularity was anchored outside of his constitutional role in widely shared popular emotions. He even made regular appearances in the dreams of those subjects, especially because his portrait was hung in hundreds of thousands of public buildings, offices, taverns, and railway stations. Prosperous and well-administered, the empire, like its elderly sovereign, exhibited a curious stability amid growing turmoil. Crises had come and gone without threatening the existence of the system as such.

The treatment of the national minorities within Hungary before the First World War could be described as ‘relatively tolerable’, especially compared with contemporary Eastern and South-eastern Europe as a whole. The security of the law was provided to all who were prepared to observe the principle of the ‘unitary Hungarian political nation’. Nevertheless, in the pursuit of grandeur, the impatience of Hungarian nationalism led to the imposition of an even greater number of Hungarian lessons in schools and the vigorous promotion of Magyar in all areas of public life. While about ninety percent of civil servants spoke the language as their first language, only a quarter of the country’s non-Magyar inhabitants could use it. There was also legislation Magyarising the names of localities, and individuals were encouraged to do the same with their own family names. Administrative and juridical action was taken against those leaders of the nationalities who not only protested against the breaches of the 1868 law, but also criticised it for its failure to recognise the rights of non-Magyar peoples, and who campaigned for national recognition and territorial autonomy.

From 1881, a united Hungarian and Transylvanian Romanian National Party demanded a separation of Transylvania from Hungary and a reinstatement of its former autonomous status. In 1892, with the support of the Romanian King Charles I, the Party addressed a Memorandum to Franz Josef listing its grievances and claims. The ruler forwarded the letter, unread, to the Hungarian government, and it was also made public by its authors, providing a pretext for the authorities to raise a lawsuit against them on the basis that they were spreading subversive propaganda, resulting in harsh sentences. Libel suits and police harassment afflicted many activists from the national minorities after the Congress of Nationalities in Budapest in 1895, which also rejected the concept of the Hungarian nation-state and demanded territorial autonomy.

The dimensions of ‘forced Magyarisation’ have often been exaggerated, even though the ratio of Magyars within the population of Hungary (excluding Croatia) climbed from 41% to 54% between 1848 and 1910; and nationalism was as intense among the the non-Magyars as among Hungarians. The difference was that the latter had the state machinery at their disposal to promote the realisation of the Hungarian nation-state. The school law of 1907 known as the ‘Lex Apponyi’ obliged non-Hungarian schools to ensure that by the end of the fourth form (at age ten), their pupils could use Hungarian. In the same year, gendarmes killed twelve Slovak protesters in the village of Csernova in northern Hungary who wanted to prevent their new church from being consecrated by a priest other than their own Slovak speaker. News of the ‘massacre’ spread across the West, doing great damage to Hungary’s reputation. There was also agitation among the Serbian minority: The Serbian PM, Novikovic, claimed in February 1909 that the Serbian nation included the seven million Serbs who lived ‘against their will’ in the Habsburg Monarchy. This was an angry response, shared by Russia, to the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia-Hercegovina.

The Anomalous Case of Bosnia-Hercegovina:

The Western Balkans, 1878-1908.

Bosnia-Hercegovina posed a special and anomalous case. Still under Ottoman suzerainty in 1878, the Austrians had occupied it on the authorisation of the Treaty of Berlin and had formally annexed it thirty years later. It was a land of harsh terrain and virtually non-existent infrastructure. The condition of these two Balkan provinces under Habsburg rule had long been the subject of controversy. There the population was made up of ten percent Catholic Croats, fifty percent Orthodox Serbs, and the rest Muslim, a legacy from Ottoman times, though speaking Serbo-Croat. The Bosnian Muslims still looked to Ottoman Turkey but were otherwise content with the status quo. The Austro-Hungarians looked to the Balkans and the ports of the former Ottoman Empire, with railway projects already in mind. These involved Bosnia, but in any case, existing Habsburg rule over the South Slavs also implied expansion into the territory. In 1878 Austria-Hungary occupied it, making it a colony with a military governor.

Thirty years later, Habsburg Foreign Minister Alois Aerenthal, who wanted to rival the power policy of Germany, the Monarchy’s ally, in the only region suited for Austria-Hungary’s purpose, the Balkans, cheated Russia. He had concluded a deal with his Russian counterpart Alexander Ivolsky regarding the annexation in return for supporting Russia’s claim for free access to the Turkish Straits. He had announced the annexation without waiting for Russia to prepare the ground with the other great powers. Despite some Hungarian hopes that, due to medieval precedents of overlordship, Bosnia-Hercegovina would be placed under Hungarian jurisdiction, it became an imperial province.

Serb nationalists still regarded it as Serbia, however, and wanted it to be taken into union with Serbia. In 1908 Franz Josef formally annexed the territory in defiance of the nationalists. Croats also continued to dream of a Greater Croatia or ‘Yugoslavia’ with its capital at Zagreb, and Franz Ferdinand was inclined to agree with this solution. However, he never had the chance to put these plans into action. The young Serb terrorists who traveled to Sarajevo to kill the heir to the Imperial throne in the summer of 1914 defended their actions by referring to the oppression of their brothers in Bosnia and Hercegovina. Historians have sometimes suggested that the Austro-Hungarians themselves were to blame for driving the Bosnian Serbs into the arms of Belgrade by a combination of oppression and maladministration. The Habsburg administration bore down hard on anything that smelled like nationalist mobilisation against the empire, sometimes with a heavy and discriminating hand. In 1913, Oskar Potoriek, military governor of the two provinces, suspended most of the Bosnian constitution of 1910, tightened government controls of the school system, banned the circulation of newspapers from Serbia, and closed down many Bosnian Serb cultural organisations, in response to an escalation in Serbian ultra-nationalist militancy. Another vexing factor was the political frustrations of both Serbs and Croats just across the borders to the west and north in Croatia-Slavonia, and to the east in Vojvodina, both ruled from Budapest under the restrictive Hungarian franchise.

One great question mark remains over why Hungary blocked the creation of a Habsburg Yugoslavia and continued to do so until the end of the Monarchy in 1918. Croats and Serbs had enough in common for it to work and Bosnia was already providing evidence for a Triune Kingdom. However, the Hungarian government did not want a co-partner, and its PM, István Tisza angrily reiterated his opposition to this solution in September 1918 when, in Sarajevo, a South Slav delegation asked for unification. His response was:

“… impertinent … Do they think Hungary will collapse? We might but before that we will still be strong enough to crush her enemies.”

Cited by Gábor Vermes, István Tisza (New York, 1985), pp.436-7.

Finally, at the very end of the Monarchy, when most Croats were still adhering to the idea of Yugoslavia, Catholic loyalists managed to get the Hungarian government to agree to the Triune Kingdom, but by then it was too late to save the empire.

However, this was, all in all, a relatively fair and efficient administration informed by a pragmatic respect for the diverse traditions of the ethnic groups in the provinces. With hindsight, though there were many severe critics of the Habsburg state, these included contemporaries like Steed, who had defended it on the eve of the July Crisis leading to the Great War. He wrote in 1913 that he had been unable in ten years of constant observation and experience to perceive any sufficient reason why the Habsburg monarchy should not retain its rightful place in the European Community. He concluded that its internal crises are often crises of growth rather than crises of decay. It was only during the War that Steed became a propagandist for the dismemberment of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and then an ardent defender of the post-war settlement in Central Europe. In 1927 he wrote that …

“… the name ‘Austria’ (was synonymous with) every device that could kill the soul of a people, corrupt it with a modicum of material wellbeing, deprive it of freedom of conscience and of thought, undermine its sturdiness, sap its steadfastness and turn it from the pursuit of its ideal.”

Tomás G. Masaryk, The Making of a State, Memories and Observations, 1914-18. London, 1927 (Czech and German editions appeared in 1925). Preface.

By contrast, the Hungarian scholar Oszkár Jászi, one of the foremost experts on the Habsburg Empire, was originally highly critical of the dual monarchy. In 1929, he wrote that the World War was not the cause, but only the final liquidation of the deep hatred and distrust of the various nations. Yet twenty years later, after a further world war and a calamitous period of dictatorship and genocide in his home country, and having been in exile in the US since 1919, Jászi struck a different note. He wrote that in the old Habsburg monarchy, …

… the rule of law was tolerably secure; individual liberties were more and more recognised; political rights continuously extended; the principle of national autonomy growingly respected. The free flow of persons and goods extended its benefits to the remotest parts of the monarchy.

Oskár Jászi, Danubia: Old and New; Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 93/1. 1949, pp. 1-31.

While the euphoria of national independence encouraged some who had once been loyal Habsburg citizens to impugn the old dual monarchy, others who were vigorous dissenters before 1914 later fell prey to nostalgia. In 1939, reflecting on the collapse of the monarchy, the Hungarian poet Mihály Babits wrote:

“We now regret the loss and weep for the return of what we once hated. We are independent, but instead of feeling joy, we can only tremble.”

Mihály Babits, Kerész életemen. Budapest, 1939.