The Continuing Cries of the terrorists, one year on:

On Monday, October 23rd 2023, John Ware wrote in Jewish News:

“Imagine being the Met Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley today as he gets a dressing down from the Home Secretary about why his officers didn’t arrest a member of the extremist group Hizb ut-Tahrir chanting “Jihad, Jihad, Jihad” during Saturday’s pro-Palestinian demonstration. Next to the man was a banner saying ‘Muslim Armies’.”

The Metropolitan Police has said no offence was identified by the chanting, sparking criticism from government ministers. In his article, Ware commented that Rowley could be forgiven for wanting to tell Suella Braverman to get the hell out of his office… and to curse her predecessor Priti Patel on Braverman’s way out. By then, immigration minister Robert Jenrick had been on TV to complain that what Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT) did needed tackling with the full force of the law. Most decent British people would agree with this. Still, Jenrick’s comment ignored the fact that, two and a half years earlier, in February 2021, at the request of the then Counter Extremism Commissioner’s request, Rowley had co-authored a report which addressed exactly the same point. It was called, Operating with Impunity.

The Social Media giant, Meta has designated Hizb ut-Tahrir a “dangerous organisation”, which means it cannot have a presence or co-ordinate on its platforms, with its Instagram page now removed. The Islamist movement’s TikTok account was also banned for violating community guidelines. An Instagram account for Luqman Muqeem, who spoke at the rally and who featured in a video on the Hizb ut-Tahrir website, has also been removed. Following the Hamas attack in Israel on 7 October, which killed more than 1,400 people, Mr Muqeem hailed Hamas as “heroes”. He said in a video posted on social media:

“This morning the heroes of Raza [Gaza] broke through the enemy lines of the yahood [Jews].”

“They stormed through the stronghold of the enemies and blackened the faces of the cowardly people. The people of Philistine [Palestine], as well as the rest of the entire ummah [Muslim community] woke up to news which made us all very, very happy.”

Downing Street indicated that there were no plans to change the law, despite concern over footage from the demonstration by Hizb ut-Tahrir on Saturday, which was separate from the main, bigger, London rally in support of Palestinian civilians. Footage at the Hizb ut-Tahrir protest showed a speaker addressing the crowd, asking: “What is the solution to liberate people from the concentration camp called Palestine?” to which chants of “jihad, jihad” were heard. Banners calling for “Muslim armies to rescue the people of Palestine” were also seen. However, the Metropolitan Police said they had concluded no offences were committed as the phrase jihad has “a number of meanings”.

The following day, Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick said: “I think a lot of people will find the Metropolitan Police analysis surprising, and that is something we intend to raise with them and discuss this incident with them.

“The legality is ultimately a question for the police, but the bigger question to me is that there should be a consensus that chanting ‘jihad’ is unacceptable.’”

He added:

“In the context that was said yesterday, that is an incitement to terrorist violence.”

“Ultimately it’s a decision for the police and the Crown Prosecution Service, but beyond the legality, there is a question of values, and I would hope there would be a consensus that chanting ‘jihad’ is completely reprehensible.”

In the week after Jenrick made his comment, Rishi Sunak indicated the police were unlikely to be given fresh powers and instead said ministers would work to “clarify the guidance” for officers to tackle people who are “inciting violence and racial hatred”. The Prime Minister told the Commons:

“Calls for jihad on our streets are not only a threat to the Jewish community but to our democratic values and we expect the police to take all necessary action to tackle extremism head on.”

Although, apparently in the opinion of the CPS, acting as advisors to the Met while watching the live feed of the demonstrations, the use of the word ‘Jihad’ was not, in itself, a breach of anti-terror or public order legislation, a cursory review of its use in a public place in the UK would suggest otherwise. It is a term which has entered the international lexicon, in English and other European languages, due to its use by modern Islamist movements in Europe over the past half-century. Ever since the murder of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics of 1972, if not earlier, the word has been associated with Islamist terrorism, hijacking, hostage-taking, bombings and other violent activities.

The Two Meanings of ‘Jihad’:

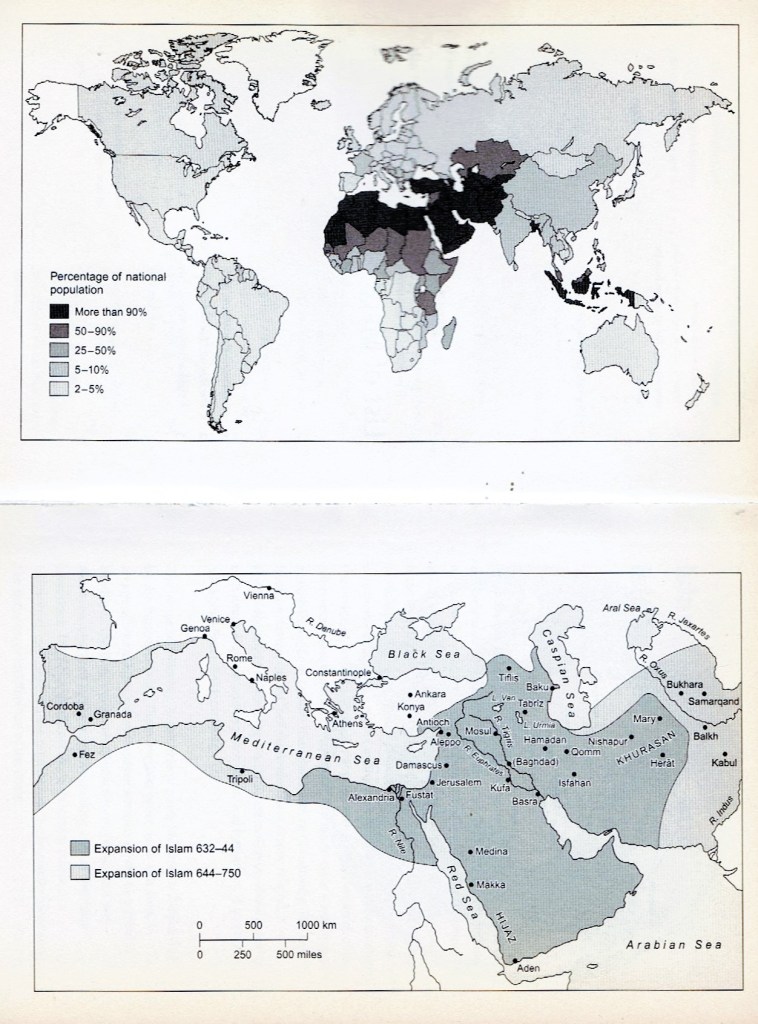

In its primary, theological meaning in Arabic, ‘Jihad’ simply means ‘endeavour’ or ‘struggle’, so its use in traditional Islamic discourse is far from confined to military matters. Its usual translation as ‘Holy War’ may be misleading, since many forms of activity are included under the term. In the classical religious context, the believer may undertake ‘jihad’ by his heart, tongue and hands; and, in the latter case, also by the sword. But the foremost of these is the first. However, it is important to emphasise what the military side of jihad achieved. It offered the tribes around the initial Medina caliphate the choice between free accession to the ummah (‘community’) of Islam and military subjugation. It led to the substantial enlargement of the Dar Al-Islam, the territory under the political control of Islam.

Nevertheless, the classical doctrine of Jihad, as interpreted politically, does imply that Islam will ultimately be triumphant. Following the logic of jihad, the world is divided into two mutually hostile camps: the sphere of Islam (dar-al-Islam) and the sphere of War (dar-al-harb). Enemies will convert, like the polytheists, or submit, like the Christians and Jews. Those who die ‘in the path of Allah’ are instantly translated into paradise, without waiting for the ‘judgement day’ or the ‘day of resurrection’. They are buried where they fall, without the need for purification. But the global triumph of Islam had to be deferred as the conquest was checked and the divinely appointed order came up against the intransigence of historical reality. In due course, the concept of dar-al-Islam was modified. As the divine law was communal rather than territorial in its application, the jurists disputed whether particular lands were dar-al-Islam or dar-al-hab, or in a state of suspended warfare, dar-al-sulh (‘sphere of Truce’).

As a confessional term in Islam, however, ‘Jihad’ is seen as a collective obligation for Muslims, though not one of the five pillars like prayer, fasting and pilgrimage, which are purely personal obligations. As fard kifaya, it can be undertaken by the ruler on behalf of the whole community and thus becomes, over time, an instrument of policy. Thus the classical doctrine of jihad was formulated during the centuries of conquest when the faith sustained an outward momentum unprecedented in human history. The doctrine was both an expression of Islamic triumphalism and an attempt, comparable to the concept of just war in Roman Law, to limit the consequences of war. Adapting the customs of pre-Islamic Bedouin warfare, an element of chivalry was built into the code: women and children, the old and the sick, were to be spared.

Polytheists were given the ‘choice’ of conversion to Islam or execution, rather like the ‘choice’ given to the pagan Germanic tribes by Charlemagne’s armies with the Pope’s blessings and under the terms of his bulls. Similarly, in parts of Africa and Asia, there are still people in animistic cults who were subjected to forcible ‘conversion by the sword’ under Islamic conquest. But Islam did not of itself force those of other monotheistic faiths into the faith, the Christians of Syria and the Near East especially. There were numerous conversions from Christianity to Islam in Syria and Egypt during this period. Still, preaching and persuasion also formed an integral part of the endeavour for Islam, and the Qu’ran opposed the use of violence as a means of conversion.

By contrast with the treatment of some polytheists, the Peoples of the Book – initially Jews and Christians, later extended to Zoroastrians, Hindus and others – were protected from ‘the sword’ by their payment of taxes. In some commentaries, these dhimmis, the protected minorities, were to be deliberately humiliated when paying taxes, though they were also exempt from military duties and the Muslim rules of marriage. The People of the book who accepted Islamic rule were allowed to practise their religion freely, enjoying a limited form of self-government. This was not religious tolerance following the values of post-Enlightenment liberalism, but the Islamic record of tolerance in medieval and early modern times compares very favourably with that of the medieval church and its appointed empires.

The Muslim World – Now and Then:

Nevertheless, in 661, thirty years after the Prophet’s death, the Medina caliphate ended in blood, and the power shifted to the caliphs of Damascus in the following century, a period of the immense enlargement of the dar-al-Islam. The armies of Islam swept in one direction along the North African coast, and across to Sicily and Spain, and were checked from further advances into Europe only by their defeat at Poitiers in 732. The crossing into Europe was explicitly justified as part of the Jihad, but the Muslim rule in Spain was one of tolerance, not of persecution. Jews who had suffered from Christian intolerance, especially from the Church of Rome, found a refreshing contrast in the attitude of the Muslims. Both Jews and Christians who retained their faiths while offering political loyalty to the Muslim régime were known as Mozarabs or ‘near-Arabs’. It was said of the Muslims in Spain that:

‘… it was probably in a great measure their tolerant attitude towards the Christian religion that facilitated their rapid acquisition of the country’.

T. W. Arnold

However, according to a well-known hadith (‘commandment’), the Prophet distinguished between the ‘lesser jihad’ of war against the polytheists (not – we should note in passing – monotheists like Christians and Jews) and the ‘greater jihad’ against evil. Despite the success of the early conquests, once they were halted at Poitiers and in India, it was the ‘greater jihad’ which sustained the expansion of Islam in many parts of the world. The dualism of good versus evil, dar-al-Islam against dar-al-harb thus became less of a collective territorial struggle and more of one conducted through legal observance. Therefore, dar-al-Islam was simply where the law prevailed.

In the same period as the Muslims pushed into Spain, armies under Muhammad ibn Qasim reached northern India and established a bridgehead of power in Sind and the Punjab. Somewhat as the Jews of Spain had welcomed the Muslim armies, so the Buddhists welcomed them to northern India, as a relief from Hindu persecution. Qasim tolerated Hindus and Buddhists alike; both had their sacred scriptures and were, therefore, people of a book, and thereby entitled to protection. He was therefore a characteristic combination of military aggression and religious tolerance. Before the military might of the West came to dominate Muslim consciousness over the last two and a half centuries, that law was synonymous with civilisation itself in that collective consciousness, extending via the trade routes through Africa, the northern subcontinent of India and Southeast Asia.

The ‘Ummah’ – ‘Brotherhood’ of Islam:

In Muslim thought, ‘man’ is always a member of a society, and therefore thought of in relation to the ‘community’. This is especially true of the brotherhood of Islam (ummah) which the Prophet compared to a single hand, like a compact wall whose bricks support each other. But although man is a ‘social animal’, he is not by nature socially righteous. The Qu’ran (20; 121) states that ‘men are the enemies of one another’ and to protect them from each other, society takes the form of the state, with authority vested in the Muslim state in the person of the ‘caliph’ or more locally in the ‘imam’:

‘We uphold that prayer for the welfare of the imams of the Muslims and the confession of the imamate; and we maintain the error of those who approve of uprising against them whenever it appeared that they have abandoned the right; and we believe in the denial of an armed uprising against them and abstinence from fighting in civil war.’

Al-Ash’ari Kitab al-Ibana

So internal violence was strictly forbidden even against tyrannous use of authority. If, in the absence of an imam, someone usurped power, his authority was binding on the community and the duty of all Muslims within it was obedience, no matter how unjust the usurper. The maintenance of Muslim unity was paramount. As already noted, there was some debate about whether the Muslim state was national or universal. Pressures from the actual historical situation compelled Muhammad and his successors to introduce legislation linked to Arab traditions, but there is no real doubt that the essential view of the Qu’ran is of a single worldwide community: one God, one mankind, one law, one ruler.

The Philosophy of Jihad:

The chief instrument for the spreading of Islam and for the establishment of a world state was the Jihad. The word means ‘striving’ and not necessarily war. The Muslim jurists in fact distinguished four different types of jihad, as we also noted above. The first is exercised by the individual in his personal fight against evil; the second and third are largely exercised in support of the right and correction of the wrong. The fourth, that of the sword, means war against unbelievers and enemies of the faith. It is part of the obligation of the faithful to offer their wealth and their lives in this war (Qu’ran 61; 11). Muslim expansion was halted at Tours in the West and at the frontiers of India in the East. The world was not, therefore, established as a single theocratic state, but was divided between the dar-al-Islam, the territory of the Faith, and dar-al-harb, the territory of war. In practice, however, most modern Muslims accept the suspension of the Jihad as ‘normalcy’, and Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) saw it as the passage from militarism to civilisation.

It is an important aspect of the Jihad that it maintained and encouraged the traditional belligerence of the Arabs, which, Ibn Khaldun argued, was responsible for courage, self-reliance and tribal unity, while ending the internecine strife between the the tribes. Within the ‘brotherhood’ of Islam, war was strictly outlawed. Belligerence was diverted against the unbeliever. The doctrine of jihad was in its own way a definition of a just war, directed against polytheists, apostates and enemies of Islam, and positively towards the establishment of the universal theocratic state. From time to time, attempts were made to establish jihad among the pillars of Islam, and some groups of scholars did include it. They insist that since the Prophet spent most of his life at war, the faithful should follow his example, that the Islamic state should be permanently organised for war, and that heretics should be forcibly converted or put to the sword. In general, however, Jihad is not among the five pillars. It is almost universally agreed among Muslim jurists that jihad is a collective obligation of Islam, fard-al-kaya; it is laid on the community, and on the state, not on the individual. It is also explicitly stated in the Qu’ran that not all believers should actively participate in war (9, 123).

Ibn Khaldun made an important analysis of war. For him, war was not an accidental calamity or a disease; its roots were in the nature of man – selfish, jealous, angry, revengeful. Wars are of four kinds: tribal wars, feuds and raids, and jihad, wars against rebels and dissenters. The first two are wars of disobedience and unjustified, and the second two are wars of obedience and therefore justified. In these, military victory is dependent on two factors, military preparedness and spiritual insight; the latter includes the dedication of the commander, the morale of the army, the use of psychological warfare, and informed and inspired decision-making.

There were therefore certain rules about participation in a Jihad. The participants must be believers (though some jurists disagreed, and Muhammad’s practice seems to have varied), adult, male, sound in mind and body, free, economically independent, acting with parental support, and endowed with good intentions. They must follow the injunction, Obey Allah and the Apostle and those in authority among you. (Qu’ran 4, 62). They must behave honourably and keep their word. They must not retreat except as a last resort. The caliph or imam was responsible for the declaration of war.

The jurists also laid down certain rules of war, and though they offered differing judgements, they all agreed that non-combatants should be spared unless they were indirectly helping the enemy cause. Some jurists held that all the participants in the Jihad could not control should be destroyed; others that inanimate objects and crops should be destroyed, but animals should be spared. Destruction and poisoning of of water supply were permitted. Spoils belonged to participants only, with one-fifth going to the state.

The ‘Mujaddids’:

The process of Islamic expansion in the modern era was organic and self-directing. Since there was no overarching global religious institution like the Catholic or Anglican churches, there was no universal, centrally-directed missionary movement. There was, however, the demonstrable effect of Muslims living literate, orderly and sober lives. The high culture originating from Cairo and Baghdad accompanied a common faith in Allah and his Prophet, a common holy book and common practices. In these ways, the struggle against evil, the ‘greater jihad’, might take a purely moralistic form, but at times of traumatic historical crisis, the ‘lesser jihad’ came back to the fore. The two jihads were, to some extent, interchangeable. The most active movements in the resistance to European imperialism during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were led by mujaddids (‘renovators’), most of whom were Sufi Muslims who sought to emulate the Prophet’s example by purifying the religion of their day and waging war on corruption and infidelity. Not all of these movements were directed against resisting Europeans: the Mahdi Mohammad ibn Abdullah in Sudan originally campaigned against the imperial ambitions of the Egyptians or ‘Turks’ he believed had abandoned Islam to foreigners.

Reformists & Modernists:

Once it became clear that Muslim arms were no match for the overwhelming technical and medical superiority of the Europeans or nominally Muslim governments backed by them, the movement for Islamic renewal took an intellectually radical turn. A return to the pristine forms of Islam would not be enough to guarantee its survival as a civilisation and way of life. The renovators were divided very broadly into ‘reformists’ and ‘modernists’. The former group was more concerned with religious renewal from within the tradition, but while using modern techniques of communication, including the printing press, the postal service and the expanding railway network, they tried to have as little as possible to do with the British and the government of the ‘Raj’ in India. Modernists, on the other hand, were from the political élite and intelligentsia which had had the most exposure to European culture. They recognised that to regain political power they would have to adopt Western military techniques, modernise their economies and administrations and introduce modern forms of education. They also argued for a reinterpretation of Islam in the light of modern conditions. Many adopted Western clothes and lifestyles which separated them from the more traditionally-minded classes. It was from these circles that the leaders of early nationalist and feminist movements were drawn.

However, there were no clear dividing lines between the two tendencies, which merged or divided according to external circumstances. Sayyid Ahmed Khan (1817-98), founder of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College of Aligarh in India, and reformers like Muhammad Abduh (d. 1906), the founder of the Salafiyya movement in Egypt, argued that for Islam to be capable of reform it needed an institutional hierarchy comparable to that of the Christian churches through which theological and legal reforms could be achieved. But they had no special authority by which they could impose their views on their colleagues, many of whom remained unreconstructed traditionalists up to the present day.

The End of the Ottoman Caliphate:

On 11 November 1914, the Ottoman Sultan and Caliph Mehmet V declared a Lesser Jihad or ‘Holy War’ against Russia, France and Great Britain, announcing that it was an obligation for all Muslims, whether on foot or mounted, young or old, to support the struggle with their goods and money. The proclamation, which took the form of a fatwa or religious decree, was endorsed by religious leaders throughout the Sultan’s dominions. Outside the Empire, however, its effect was minimal. Even the Emperor’s suzerain, Sharif Hussein of Makka, the Guardian of the Holy Places, refused to endorse the fatwa publicly. He had already been approached by the British with a proposal to launch an Arab revolt against the Turks, the success of which ultimately ended with Feisal and Abdullah being given the British-protected thrones of Iraq and Jordan. The would-be rulers of Syria, Mesopotamia, Palestine and the Hejaz (the western region of the Arabian peninsula, including Saudi Arabia) also preferred freedom to ‘Islamic’ rule, even though for many Arabs that freedom would soon result in a new colonialist domination.

Then, as in more recent times, pan-Islamic solidarity proved an illusion. The collapse of the Ottoman armies in 1917-18 drove that point home and a revitalised Turkish nationalism under Mustafa Kemal led to the removal of Greek and Allied forces from Anatolia, which was seen as a Jihad. On 19 September 1921, Mustafa Kemal (‘Ataturk’) was formally accorded the rank of Ghazi, given only to those who have participated in a jihad. The National Assembly then took the ultimate step of abolishing the caliphate in 1924. This brought the crisis of Islamic legitimacy to a head, provoking a mass agitation by the Muslims of India protesting about the breaking of the final link between an existing Islamic state and the divine polity founded by the Prophet.

Arbitration & Reconciliation:

One important aspect of Muslim law lies in the concept of arbitration, which has its basis in The Qur’an:

‘Oh you who believe! Obey Allah and the Apostle, and those among you invested with authority; if you differ upon any matter, refer it to Allah and the Apostle, if you believe in Allah and in the last day. This is the best and fairest way of settlement.

The Qu’ran, 4: 62.

Arbitration was a method of settling disputes within Islam to avoid the temptation of internecine strife. Still, Muhammad himself had submitted to arbitration a dispute with a Jewish tribe. This precedent led to the principle that arbitration was permitted between Muslim and non-Muslim communities in matters which did not involve the Faith, a good example being agreements to stop fighting. Although pacifism is virtually unknown in Islam, there has always been an inclination to emphasise the spiritual aspect of the teaching of the Jihad. This is especially strong in the Sufi tradition, which claims that its basis is weaning ‘the Self’ from its habitual ways and directing it contrary to its desires. The jihad of ordinary Muslims consists in fulfilling actions like the purifying of ‘the inner Self’. Al-Jilani (d. 1166) cited the Prophet as saying, ‘We have returned from the lesser Jihad to the greater Jihad’: meaning the conquest of the Self is a greater struggle than conquest over external enemies.

So too the Ahmadiyya movement has stressed the the true meaning of ‘the endeavour’. Thus, the spirit of jihad ‘enjoins… every Muslim to sacrifice his all for the protection of the weak and oppressed whether Muslims or not’. The Ahmadiyyas also emphasise the need for active resistance and not just prayer and meditation. The test of jihad lies therefore not in the practice of war but in the willingness to suffer. They totally disown the concept of a lesser jihad directed at the expansion of Islam. While there may be a necessity for armed defence against aggression, the essence of jihad lies in an active concern for the oppressed. One remarkable demonstration of such beliefs took place in 1930 among the Pathans of northern India, a people with traditions of violence. Abdul Ghaffir Khan, known as ‘the Gandhi of the frontier provinces’, a Puritan reformer, persuaded the Pathans of the power of non-violence. Persecution, imprisonment and execution did not shake them: they persisted for years in a courageous commitment to non-violence, demonstrating that the Islamic jihad can turn into an endeavour for peace and reconciliation.

The Quest for a new Caliphate:

From its very beginning, the Khilafat Movement dramatised the fundamental contradiction between pan-Islamic and national aspirations, including those of the Arab peoples. In India, it represented a turning point in the anti-colonialist movement, as Muslims who had previously been appeased by Britain’s Eastern Policy favouring the Ottoman interest, joined Hindu nationalists in opposition to the Raj. But that coalition proved short-lived, and the momentum generated by the Khilafat movement would eventually lead to a separate political destiny for India’s Muslims in the form of Pakistan. The movement, however, evoked no significant response in the Arab world, where it had become identified with Ottoman rule. Nor was it popular at its former centre in Turkey, where it was associated with a discredited political system.

In Egypt, a highly controversial essay published in 1925 claimed that the institution had no basis in Islam. It argued that the fact that the prophet had combined spiritual and political roles was purely coincidental and that the latter-day caliphate did not represent a true consensus of the Muslim world, since it was based on force. Rashid Rishda, Abduh’s more conservative disciple, though once its supporter, accepted its demise as symptomatic of Muslim decline, though he did not support Turkish secularism. The ideal caliph, he said, was an independent interpreter of the Law, a mujtahid, but given the absence of such a figure, the best alternative was for an Islamic state ruled by an enlightened élite in keeping with the Islamic principle of consultation (shura) with the people, able to interpret the Shari’a and legislate as necessary.

The Muslim Brotherhood:

Many of Rashid Rishda’s ideas were taken up by the most influential Sunni reform movement, The Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928 by Hasan al-Banna, an Egyptian schoolteacher. The Brotherhood’s original objectives were as much moral as political: it sought to reform Muslim society by encouraging religious observance and opposing Western cultural influences, rather than by attempting to capture the state by direct political action. However, during the mounting political crisis over Palestine in the mid-late 1930s, and after the Second World War, the Brotherhood became increasingly radicalised. In 1948, Prime Minister Nugrashi Pasha was assassinated by a brotherhood member and Hasan al-Basha paid for this with his life in a retaliatory killing by the security services the following year. The Brotherhood played a leading part in the disturbances leading to the overthrow of the Egyptian monarchy in 1952, but after the revolution, it came into conflict with the nationalist forces under the government of Gamal Abdul Nasser. In 1954, after an attempt on his life, the Brotherhood was suppressed, its members exiled or imprisoned, or driven underground.

It was during this period that the Brotherhood became internationalised, with affiliated movements springing up in Jordan, Syria, Sudan, Pakistan, Indonesia and Malaysia. They also found refuge in Saudi Arabia, together with financial support, providing funds for the Egyptian underground and salaried posts for exiled individuals. One of their popular doctrines had a profound impact on Islamic political movements. This was the theory that the struggle for Islam was not about the restoration of an ideal past, but for a principle relevant to the ‘here and now’: the vice-presidency of man under God’s sovereignty. The Jihad was therefore not just a defensive war for the protection of Islamic territory but for the waging of war against governments which prevented the preaching of faithful Islam, for the condition of jahiliya, or the ignorance before the coming of Islam, was still to be found in that ‘here and now’. Just as the Prophet had fought the old jahiliya, a new élite among the Muslim youth would be needed to fight the new one. These ideas set the agenda for Islamic radicals throughout the Sunni Muslim world, such as Abd al-Salaam Farraj, who was executed for the murder of President Anwar Sadat in 1981.

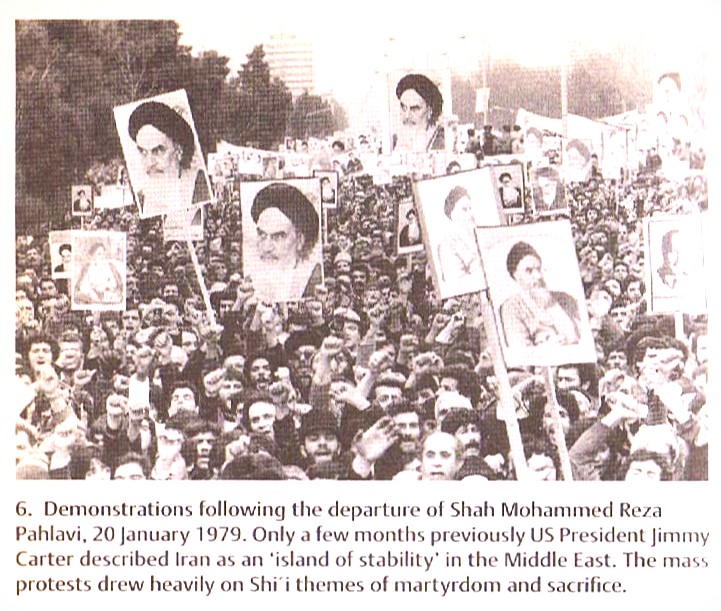

The Impact of the Iranian Revolution:

Although the writings of the Islamic Brotherhood have remained an important influence on radical Islamists from Algeria to Pakistan, in February 1979 a significant boost to the movement came from Iran where Ayatollah Khomeini came to power after the collapse of the Shah’s régime. During the final two decades of the twentieth century, the Iranian Revolution remained the inspiration for Muslim radicals or ‘Islamists’ from Morocco to Indonesia. Despite its universalist appeal, however, the revolution never succeeded in spreading beyond the confines of Shi’ite communities and even among them its capacity to mobilise ordinary Muslims remained limited. During the eight-year war that followed Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran in 1980, the Iraqi Shi’ite communities, forming about half of the country’s population, conspicuously failed to come to the aid of their co-religionists in Iran. The Revolution did spread to communities in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Bahrein, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, but generally proved unable to cross the sectarian divide. The new Shi’a activism in these countries either stirred up sectarian conflicts or stimulated severe repression by Sunni governments, especially in the case of the Marsh Arabs of Iraq.

Within Iran, the success of the revolution rested on three factors, usually absent from the Sunni world: the mixing of Shi’ite and Marxist ideas among the urbanised and radicalised youth in the 1970s, very evident among expatriate students in the West; the autonomy; the autonomy of the Shi’ite religious establishment which, unlike the Sunni ‘ulama, disposed of a considerable amount of social power as an ‘estate’; and the eschatological expectations of popular Shi’ism surrounding the return of the Twelfth Imam. Significantly, the leading exponent of Islamic revolutionary ideology among the Shi’ites was Ali Shari’ati (d. 1977), a historian and sociologist who had been partly educated in Paris and who established an informal academy in Tehran, from where he influenced large numbers of young people from the traditional classes through his popular lectures. These contained a rich blend of ideas from the Muslim mystics with the insights of Marx, Satre, Camus and Fanon. Shari’ati himself translated some of these latter works into Persian. These revolutionary ideas provided a vital link between the student vanguard and the more conservative forces which brought down the Shah’s régime, mobilised by Sayyid Ruhallah Khomeini. In exile in Iraq, Khomeini developed his theory of government, which broke with tradition by insisting that this should be entrusted directly to the religious establishment, i.e. in a theocracy.

The Appeal of Islamism:

Outside Iran, however, the factors that contributed to the Islamic revolution continue to sustain the Islamist movement, accounting for the continuing popularity of their ideologies. The collapse of communism and the failure of Marxism to overcome the stigma of ‘atheism’ has made Islamism seem an attractive ideological weapon against corrupt and dictatorial régimes. In Muslim countries, the recently urbanised underclasses have been radicalised by the messages of populist preachers. At the same time, since the turn of the century, the Islamist movements have earned respect and gratitude by providing a network of services able to plug the gaps caused by government shortfalls and cuts in international aid. The withdrawal of state agencies from some areas has led to their replacement by Islamic welfare organisations and charitable organisations. In turn, these voluntary organisations have found generous sources of funding in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states. As the former nationalist rhetoric, whether nationalist or Ba’athist, became discredited, the Islamist groups stepped into the power vacuum to impose their own authority and view of discipleship. Their organisation was not one of popular participation, however, but was based on activists and militants, who patronised the common people as subjects of ethical reform, to be converted to orthodoxy and mobilised in political support.

Veterans of the Afghan War against the Soviet occupation in the 1980s formed the core of armed and trained Islamist groups in Algeria, Yemen and Egypt. At the height of the war, there were said to have been between ten and twelve thousand mujahadin from Arab countries financed by mosques and private contributions from Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states. Many of them, ironically, were reported to have been trained by the CIA. Saudi influence has also continued to operate at religious and ideological levels. Many of the Islamists active from Egypt to Algeria in the 1990s spent time as teachers and exiles in Saudi, where they became converted to the rigid, puritanical version of Islam practised there and tried to impose the jurisprudence of the Hanbali school on their own countries.

Following the Soviet-Afghan War and the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe, Islamism began to dominate the political discourse in Muslim lands in the 1990s. But before the 9/11 attack of 2001, it seemed unlikely to bring about a ‘clash of civilisations’ or even to effect significant external political change. At that point, the practical effects of Islamisation entailed, not a confrontation with the West, but rather a cultural retreat into the mosque and private family space. Because the Shari’a protects the family, the only institution to which it grants real autonomy, the culture of Muslims seemed more likely to become increasingly passive, privatised, and consumer-oriented. Yet new technologies began to invade the previously sacred space of the Muslim home, and the result, ironically, was increasingly one of global radicalisation of young Muslims via the internet.

On the eve of the new century, existing Muslim estates, even including Iran, seemed to be locked into the international system. Despite the turbulence in Algeria and episodes of violence in Egypt, there were fewer violent changes of government in the Middle East in the last three decades of the twentieth century than in the preceding two decades when different versions of Arab nationalism competed for power. At the same time, the political instability in Pakistan and the continuing war in Afghanistan indicated that ‘Islam’ in its then-current political and ideological forms was unable to transcend its own ethnic and sectarian divisions. The territorial nation-state, though never formally sanctified in the Islamic tradition, was proving highly resilient, not least because of the support the Arab states received through the international system. For all the Islamist protests against Operation Desert Storm, in which the Muslim armies of Egypt, Pakistan, Syria and Saudi Arabia took part in the autumn of 1990, alongside the USA and UK, it remained the case that where major economic and political were at stake, the existing international order remained intact. Malise Ruthven, in his (1997) Very Short Introduction to Islam, optimistically concluded that:

For all the protestations to the contrary, the faith will become internalised, becoming private and voluntary. In an era when individuals are ever less bound by ties of kinship and increasingly exposed tourban anomie, Muslim souls are likely to find the inner Sufi path of inner exploitation and voluntary association more rewarding than revolutionary politics. Sadly, more blood can be expected to be split along the way.

Ruthven, p. 142.

Red October and its Ongoing Aftermath:

(Photo by SAID KHATIB / AFP)

Several Islamic scholars affiliated with Hamas have called for the killing of Israelis and Jews in the aftermath of the terror group’s onslaught in southern Israel on 7th October, in some cases issuing fatwas, or Islamic legal opinions, commanding Muslims to wage armed jihad. Saleh al-Raqab, a professor of religion at Gaza’s Islamic University and a former minister of religious affairs and endowments in the Hamas government, published an article on 8th October, the day after the brutal assault in which 1,400 Israelis were killed, titled Oh Mujahideen in Palestine. Al-Raqab wrote:

O Allah, grant victory to the fighters in Palestine, guide their strikes to the throats of Jews, make their legs steady and let them stab a knife through the hearts [of the Jews], Enable them to kill the soldiers of the Jews, destroy the weapons of the Jews, and capture Jewish soldiers. O Allah, destroy the Jews completely. Paralyze their limbs and freeze the blood in their veins.

The Palestine Scholars Association in the Diaspora published a fatwa on 21st October permitting ‘jihad’ against the Zionists as one of the main obligations of our religion, with the stated goal being to free the al-Aqsa Mosque and repel Zionists from the Islamic country of Palestine. The fatwa quotes a Qu’ranic verse that says:

You will find that the most bitter enemies of Muslims are the Jews and the polytheists.

The Hamas-affiliated association, which defines itself as an independent body that gathers Palestinian scholars who reside abroad to serve the Palestinian cause and establish an Islamic legal framework for it, was founded in Beirut in 2009 and is today based in Istanbul. The fatwa also described the Palestinian mujahideen (jihad fighters) led by Hamas as the best mujahideen on earth and urged followers to refute claims that their jihad amounts to terrorism.

In another fatwa published on 20th October, the association commanded every capable adult Muslim to be ready to fight, while those who can’t are enjoined to support Hamas financially. It lashed out at Muslim countries that have normalized relations with Israel, stipulating that normalization agreements are void and do not entail any obligations. In a legal response published on October 24, a member of the Yemenite branch of the Scholars Association named Aref bin Ahmed al-Sabri wrote that Jews and their property are legitimate targets as long as they fight against Muslims. He further called on Arab countries around Israel to intervene to repel Jews from Palestine, stating that the land belonged exclusively to Muslims, and not an inch of it may be given up.

Meanwhile, the UK’s ‘Levelling Up’ Secretary Michael Gove is understood to have ordered officials to draw up a new official definition of extremism in a move to counter antisemitism. The work is understood to have started before violence flared up again in the Middle East. Ministers are reviewing the definition of extremism in a move that could reportedly allow councils and police forces to cut off funding to charities and religious groups found to have aired hateful views. The 2021 report, referred to in the introduction, urged ministers to do more to eradicate extremism, with the official watchdog, the Commission for Countering Extremism, concluding then that gaps within current legislation had left it harder to tackle “hateful extremism”.

On Saturday 28th October, nine people were arrested in central London during a second, mainly peaceful pro-Palestine demonstration, with at least a hundred thousand protesters calling for a ‘ceasefire’ in the Israel-Hamas war. Seven of the arrests were alleged public order offences, a number of which are being treated as hate crimes, while two are for suspected assaults on officers. The Metropolitan Police on X, formerly Twitter, confirmed it was reviewing a potential “hate crime incident” in Trafalgar Square following chanting that referenced the Medieval Battle of Khaybar, referring to a massacre of Jews in the year 628 by Islamic forces. Officers also followed up on reports that a pamphlet was being sold along the route of the march that praised Hamas, the force confirmed on social media. Hamas is a proscribed terror organisation in the UK, with expressions of support for it therefore banned. Separately, The Sunday Telegraph has reported that the Home Office is examining potential changes to terrorism legislation.

Secondary Sources:

Malise Ruthven (2000), Islam: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

John Ferguson (1997), War and Peace in the World’s Religions. London: Sheldon Press.