The Condition of the People of the Valleys:

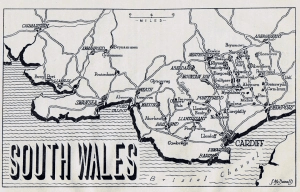

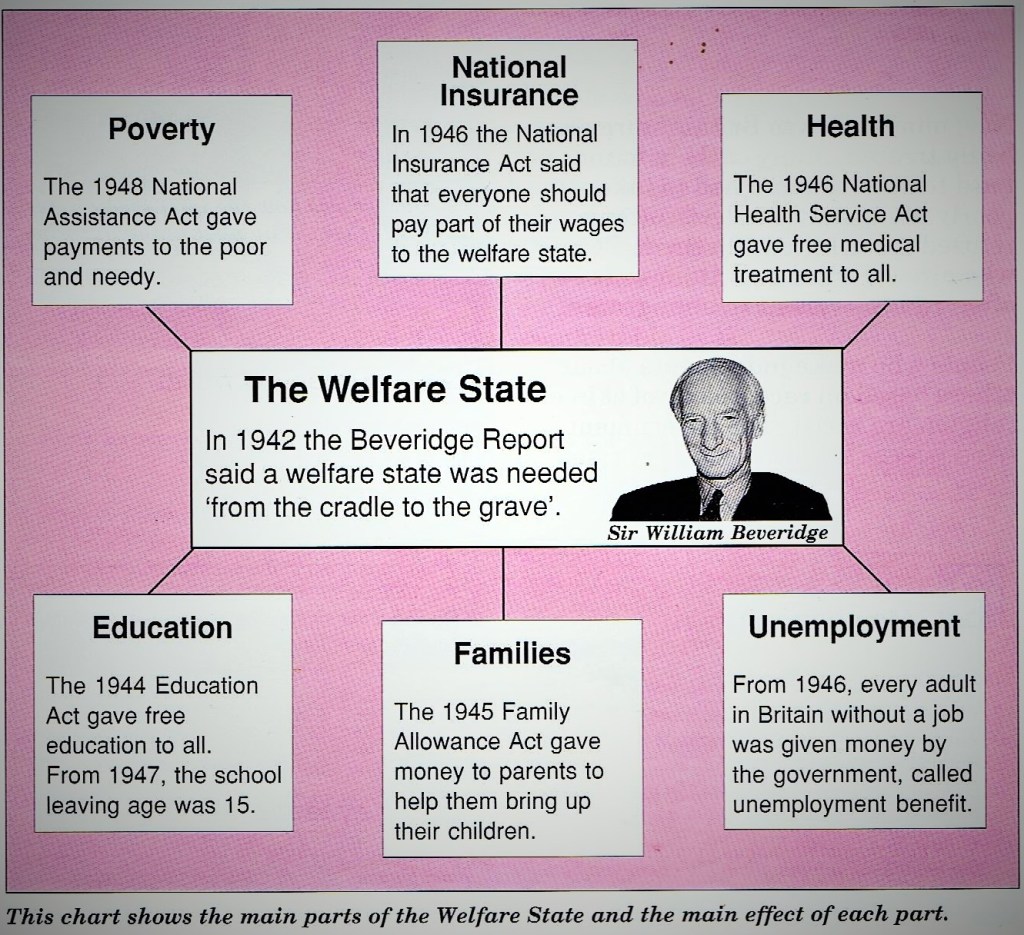

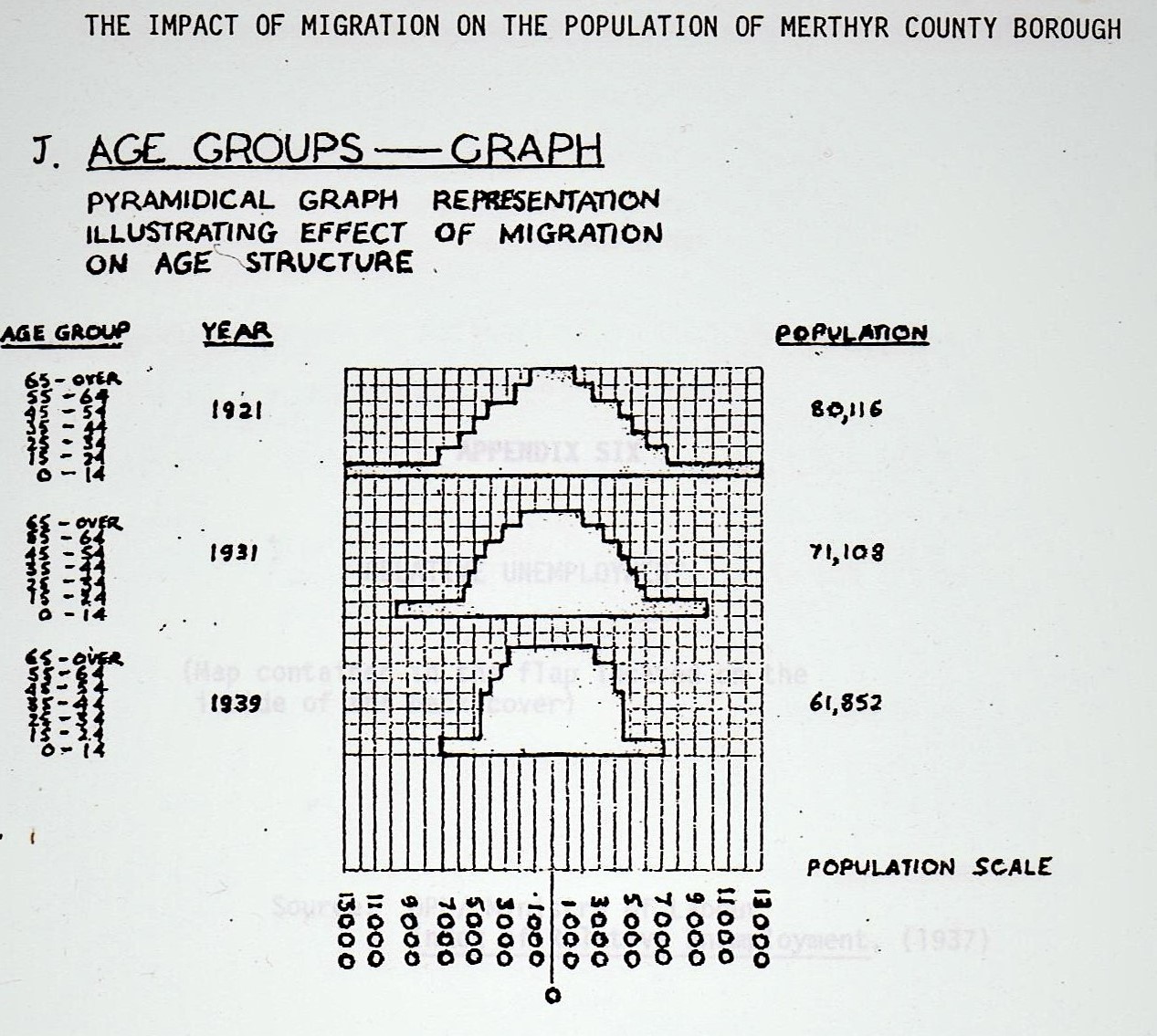

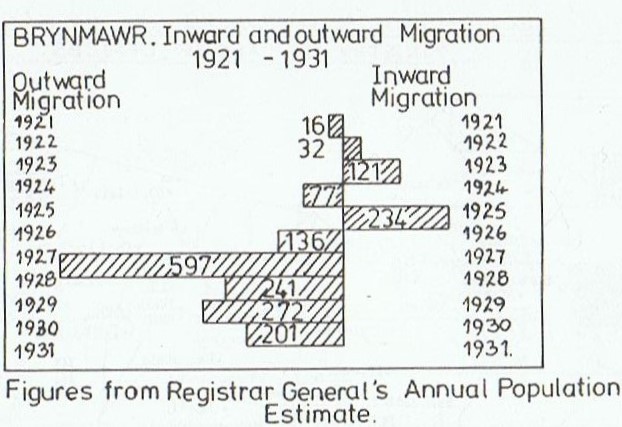

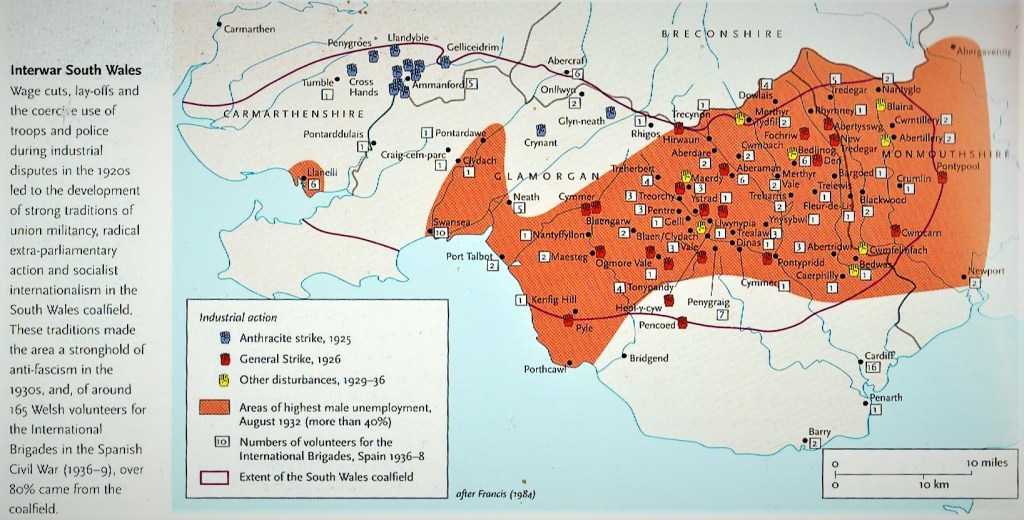

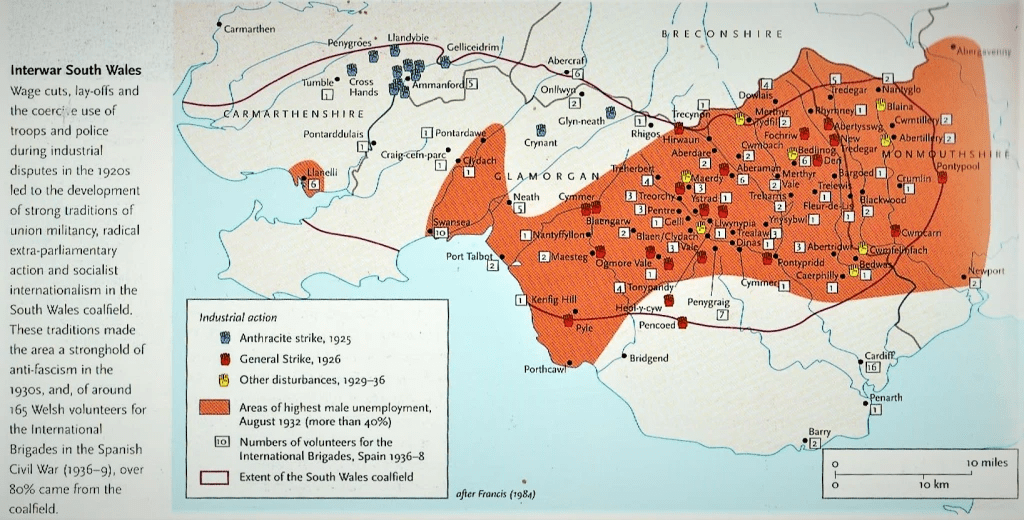

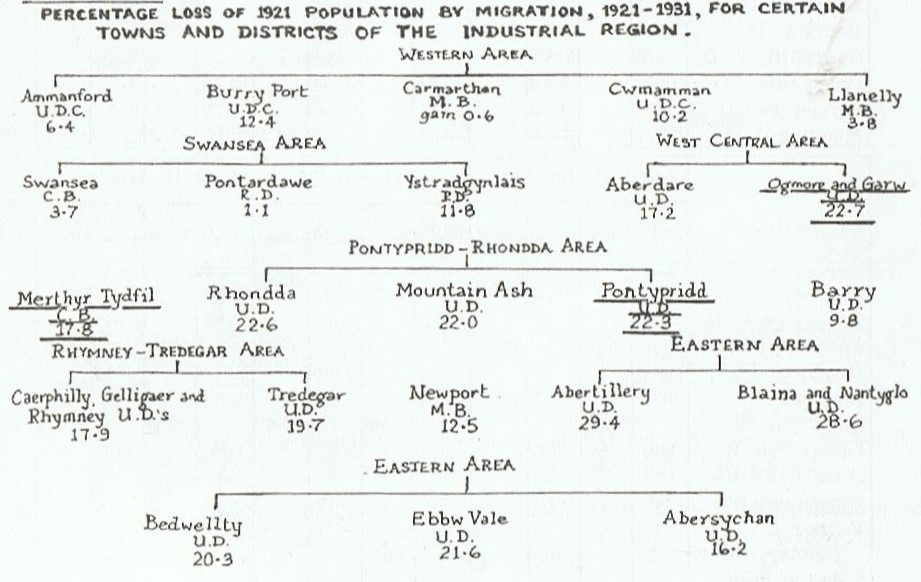

Most reflective articles relating to the National Health Service I have read or heard in this seventy-fifth anniversary year have seemed to concentrate on those years since its foundation, almost as if it suddenly materialised fully formed from Aneurin Bevan’s mind. Apart from limited and brief references to the Tredegar Scheme as the source of inspiration for Bevan’s national scheme in 1948, very little has been written about its long-term motivations in the broader social and demographic changes affecting Great Britain during the inter-war years. Over the decade since the Great War, the population growth accompanying industrialisation had already been slowing significantly. The population of England and Wales had almost doubled, despite relatively high levels of outward migration. The growth rate between the wars was only about a third of that experienced throughout the Victorian era and only half of that about a third of that of the Edwardian period (1901-1914). This deceleration in Britain as a whole increased the drift of the population to the Midlands and South East of England and had it not been for the degree to which South Wales stood out against this trend by maintaining a high rate of natural increase throughout the period, the effect of the scale of out-migration could have been far more catastrophic. Indeed, this was an observation made by those entrusted with planning for the post-war reconstruction of the Welsh economy, the Welsh Reconstruction Advisory Council (WRAC), in their First Interim Report (1944: pp. 13-14).

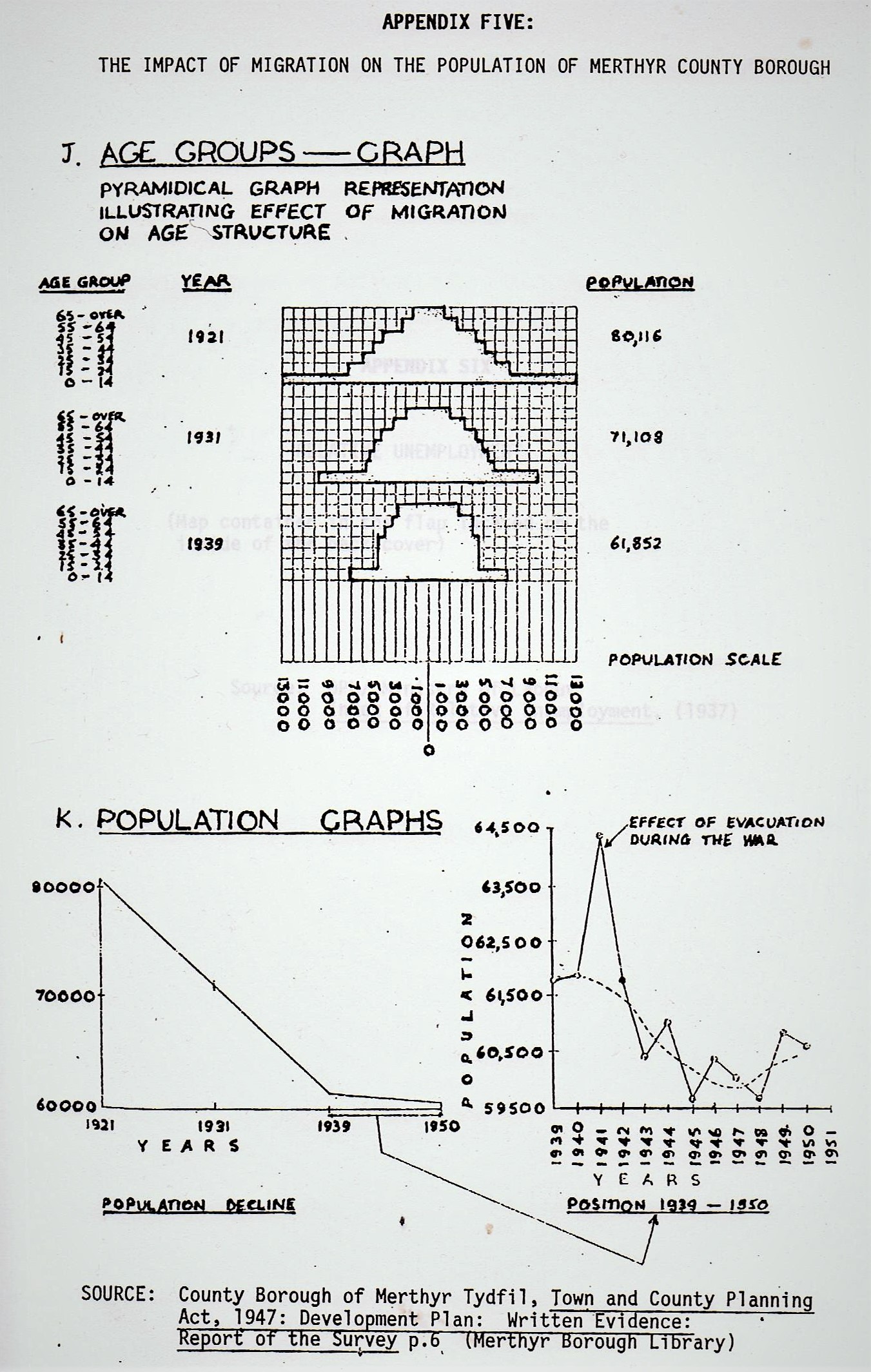

A deeper cause for concern was reflected in the age structure of the population. For the first twenty years of the twentieth century, South Wales possessed the youngest population in Britain. Due to its high birth rate, a third of the 1911 Welsh population was to be found in the 0-14 age range and, largely due to the influx of large numbers of young, economically active people, a further forty-seven per cent was located in the 15-44 age range. By comparison, twenty-eight per cent of the British population was under fifteen in this year, forty-seven per cent was between fifteen and forty-four, and twenty-five per cent was forty-nine and over. The inter-war years saw, throughout the whole of Britain, a steady increase in the older age range and a marked decline in the number of young dependents resulting from the falling birth rate and, as might be expected from the above statistics, continuing proportionate growth of the economically active section of the population. The full extent and impact of this can be judged from that, by the end of the inter-war period there was one additional potentially productive member of the national community for every ten such people in 1871. These population changes meant that, while the country’s capacity for consumption increased by eighteen per cent between 1911 and 1938, its human capacity for production increased by twenty-seven per cent. This led one commentator to the conclusion that…

‘… at least from the point of view of material well being, the composition of Britain’s population in 1938 was more effective than it was a generation earlier.’

Mark Abrams, The Condition of the British People, 1911-1945: A Study Prepared for the Fabian Society. London: 1945, p. 22.

However, this benefit was not evenly distributed throughout Britain. Between 1921 and 1938 the South and Midlands experienced a loss of 12.5% in the 0-14 age range, a gain of 3% in the 15-24 age range, and a gain of 22% in the 25-44 age range. The respective, comparative figures for Wales showed a loss of 27%, a loss of 20% and no change in the latter group. By 1938 South Wales had been relegated from having the youngest population in Britain to a position where it had fallen behind the national average, and well behind the Midlands and South East in terms of the proportion of its population made up of 15 to 34-year-old males. Clearly, the inheritance of the pre-war years had been quickly lost.

There were five factors involved in the changing age structure of the population and the unevenness of these changes between regions. Here I wish to identify and examine four of these – birth and death rates, infant and maternal mortality. These were all directly though not exclusively connected to the general health of the population, as well as more indirectly to the fifth – migration – which I have dealt with in other articles on this site, based on my original research. Firstly, it is worthy of note that even in the trough of the Depression, in 1931, South Wales, along with Scotland, Northumberland and Durham, still had the highest birthrates in Britain. While their birth rates were declining significantly compared to what they had been in 1911, they were able to sustain their overall population throughout the interwar period and beyond through these comparatively high levels of fertility.

This was also an observation made by contemporaries, such as J. D. Evans of University College, Cardiff, when he reported to the Nuffield College Reconstruction Survey in 1942. In particular, he pointed to the way in which the ‘voluminous outflow of youth from the distressed areas of South Wales was offset by the high fertility of the people.’ In 1934, South Wales still possessed a birthrate per thousand of 16.1 compared with 15.4 in the West Midlands and 13.9 in the South East, at a time when both the English regions were emerging prosperous from the Slump, though the Coalfield was still experiencing high levels of mass unemployment. It was not until the years 1937-39 that the rate of births among women in South Wales fell below those among West Midland women.

Quite clearly, this decline in the birth rate, coupled with the continued migration of nearly half a million people between 1920 and 1940 would have inverted the age structure of South Wales from what it had been at the beginning of the interwar period, had the Second World War not intervened. What is remarkable is that the birth rate continued at such a high level throughout the depression years. These regional disparities cannot be explained in terms of relative economic security. Historians have pointed to the involvement of women in the manufacturing industry of the West Midlands and Lancashire as an important element in spreading effective birth control techniques; the highest birth rates continued to be recorded, throughout the period, in those industrial areas where employment was mostly dominated by men.

During the interwar years, the annual death rate for Britain as a whole remained at around twelve per thousand of the population. However, when corrections are made for the changing age composition of the population, it becomes apparent that the rate had fallen by approximately twenty-five per cent between 1911 and 1939. On the surface of it, this represented a substantial improvement in the health of the country as a whole, but once again a national average figure disguised marked regional differences. Mark Abrams summed these up as follows:

‘In the three years before the outbreak of this war, regional differences were so great that a train journey of less than a hundred miles was sufficient to take one of the areas with something like the lowest death rate in Europe, to areas where the returns were little better than those for Britain as a whole in the first decade of this century’.

Mark Abrams (1945), p. 26.

The crude death rates are insufficient to reveal this disparity. A truer picture can be gained by comparing actual deaths with expected deaths. These calculations demonstrate that deaths were well above average in the comparatively youthful populations in the North of England and South Wales, average in the Midlands and below average in the South East of England. In reality, in the period 1937-39, South Wales had a mortality rate seventeen per cent higher than that for England and Wales as a whole, and thirty-one per cent higher than that in the South East. This difference was almost as great as that between Britain in 1911 and in 1939, giving further evidence of there being ‘two Britains’ not far apart in physical distance but nearly three decades apart in terms of the relative physical health of regional populations.

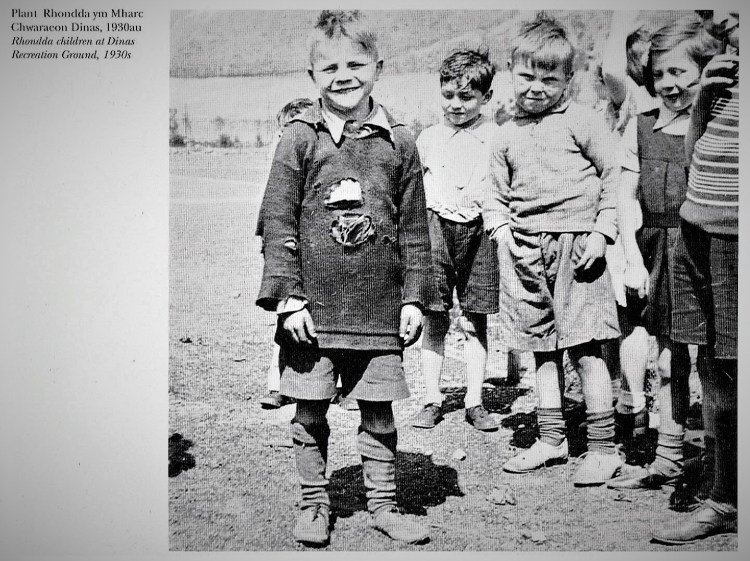

In 1938, Richard Titmuss published his groundbreaking study, Poverty and Population: A Factoral Study of Contemporary Social Waste, in which he attempted to assess the extent, character and causes of social waste and to relate the findings to the problem of an ageing and diminishing population. Titmuss set out to analyse two factors which he considered to be significant in this process. Firstly, those regions suffering from ‘economic under-privilege’ and most exposed to malnutrition contained by far a higher proportion of children and secondly, it was only higher fertility that prevented a calamitous fall in the size of the population. Titmuss produced statistics showing that in 1936 over a tenth of deaths in South Wales were of children under the age of four, compared with 8.5% in the South East, and that more than half the deaths in South Wales occurred before the age of sixty-five, compared with forty-seven per cent in the South East.

Infant mortality was also much higher in South Wales, at sixty-three per thousand, from which he calculated that there were five thousand excess deaths of infants under the age of one in the North of England and South Wales during 1936, or approximately thirty thousand surplus deaths since the depth of the slump of 1931. Deaths from measles were proportionately twice as high in Wales as for England and Wales as a whole, implying a widespread prevalence of rickets, malnutrition and poverty. In the years 1931 and 1935, whilst the South East showed a considerable improvement in the numbers of infant deaths, in South Wales, there was a continuing deterioration.

Similarly, maternal mortality rates in the region were well over twice those in the South East, and Titmuss felt able to state that if the maternal mortality rates in the region had been the same for Greater London, the lives of 586 mothers would have been saved. Female deaths from tuberculosis in the fifteen to thirty-five age group in South Wales were seventy per cent above the average for England and Wales. Titmuss went on to calculate that the number of avoidable, premature deaths in the North of England and Wales in 1936, a year of relative prosperity, was 54,000 and that the cumulative number over the previous ten years was of the order of half a million. The high levels of infant, child and maternal mortality, taken together, can only be fully appreciated when it is realised that forty per cent of the total child population in England and Wales was situated in the two older industrial regions, whereas the proportion of the adult population located there was little more than a third.

Unemployment & Health:

However, though the regional contrasts are striking, it is difficult to isolate relative poverty from other factors such as climate, housing conditions, and quality of medical and social services. H. W. Singer’s (1937) study for the Pilgrim Trust on Unemployment and Health is helpful in this respect by isolating the effects of the general trade depression, or ‘slump’ of 1929-34, and correlating the unemployment statistics during these years with a range of indices of health for seventy-seven boroughs throughout England and Wales. In this way, the differences between these localities in terms of regional variations in other conditions could be eliminated. Through this process, Singer was able to identify a correlation between rising unemployment and a rise of twenty per cent in both infant mortality and maternal mortality.

None of the data examined by Singer failed to exhibit some sort of correlation with unemployment, and it was certainly the view of those who visited South Wales and gave anecdotal evidence that there was a direct correlation between the economic distress of its population and their health. Levels of voluntary Health and welfare provision across South Wales were considered greatly inferior to those in other regions, though varying greatly across the region itself. Philip Massey, in his (1937) Portrait of a Mining Town, argued that the majority of the unemployed in Blaina and Nantyglo could be described as having a diet which was inadequate according to the standard set by Medical Officer of Health, Sir John Orr, published in his Food, Health and Income the previous year. Those whose weekly expenditure on food was five to seven shillings per head had a diet which was adequate only in total proteins and total fat; this category also included many families whose ‘head’ was in work. Those in work could afford expenditure of up to nine shillings per head ön food, but perhaps the majority of ‘wage-earning’ families, would have a diet adequate in energy value, protein and fat, but below standard in minerals and vitamins.

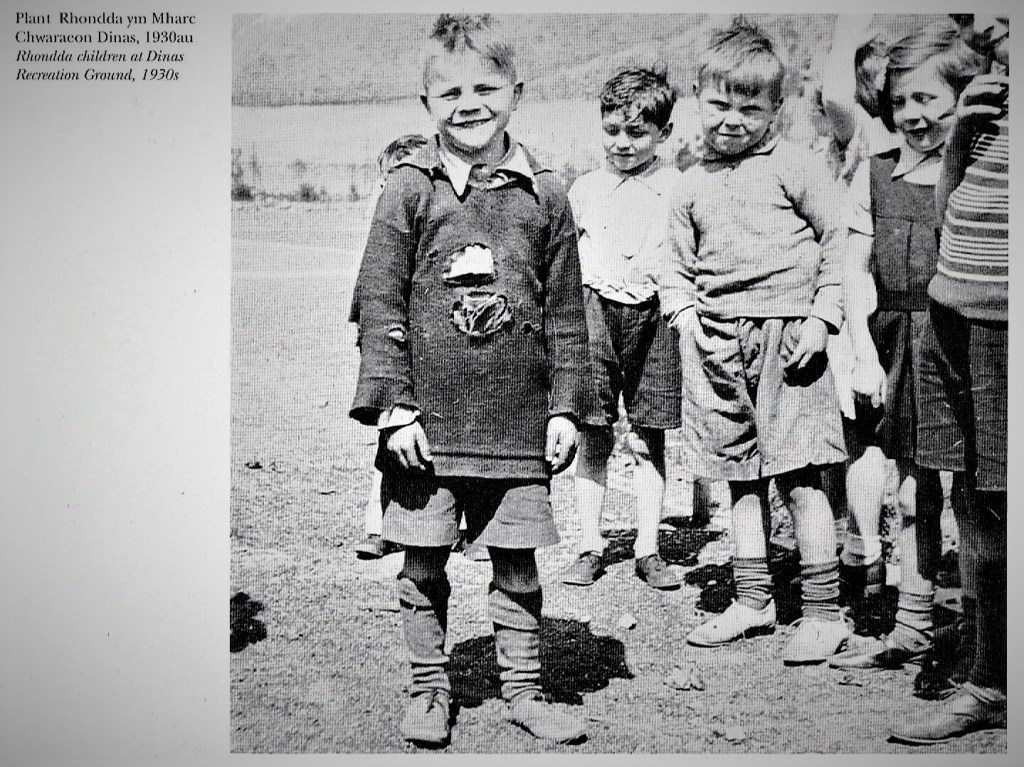

Evidence of the effects of this poverty of diet is found in the information given in the reports of the local Medical Officers and school authorities. In a joint report for the Ministry of Health entitled Distress in Wales, J. Llewellyn Davies, Pethwick-Lawrence and Evans provided stark evidence of the impact of poverty on families in the Monmouthshire valleys. The children of Abertillery in 1928 were said to be suffering from a lack of ‘tone’ and had less ‘grip’ than previously. The average weight of the girls showed a falling off at all ages. Despite the provision of free meals to ‘necessitous children,’ non-attendance had risen from about six per cent in the winter of 1926-7, to about nine per cent in the winter of 1927-8. In nearby Blaina, a medical examination in that same year had found 423 out of 3,245 children to be physically subnormal from lack of nourishment. In the case of 250 of them, or nearly eight per cent, their condition was attributed directly to poor family conditions. It was also reported that 247 school weeks were lost in the last quarter of 1927 due to a lack of boots, stockings, and other clothing, unemployed families having ‘literally no means except private charity’ from which clothing could be obtained. Without this help, the child population of Blaina, Nantyglo and Abertillery would have had no boots and the rest of their clothing would have been ‘worn to shreds.’

Whilst the provision of basic welfare services on a voluntary basis may have mitigated their effects on some children, they were inadequate in assisting impoverished families as a whole. Indeed, such services as did exist were often under great financial pressure themselves. For instance, in 1928 a small deputation led by George Hall M. P. pressed the case of Blaina Hospital to the Ministry of Health. The hospital’s income was dependent upon contributions paid weekly by miners so the effect of the general closure of pits in the district was disastrous. Its account was overdrawn to the extent of Ł2,000, and, whilst income for the year was estimated at Ł2,500, costs were expected to be of the order of Ł4,000. This was not an isolated case, according to reports. Clearly, the many hospitals in the valleys of South Wales and Monmouthshire funded through voluntary schemes would struggle to survive prolonged stoppages in the coal industry.

The combination of long-term unemployment, the resulting poverty, poor housing and overcrowding experienced by the communities at the heads of the valleys took a heavy toll on the health of their population. In Merthyr in the late 1930s, the number of women suffering from tuberculosis was nearly two-and-a-half times the standardised average for England and Wales as a whole; among men, it was one-and-a-half times. One infant in every five died before the age of five, and malnutrition, rickets, diphtheria and pneumonia were widespread among schoolchildren. Already by 1932, the average age of death in the borough was down to forty-six years.

In 1937, a further official survey on the health of boys at the Blaina Boys’ School, quoted by Philip Massey, revealed that, though the condition of many children was better than in the previous report from the town, there were still serious problems in many families. On the wet day when the inspectors made their visit, forty-three per cent of the boys had damp or wet feet. More than a quarter of the two hundred or so at the school had clothing which was ‘poor’ or ‘bad’ whilst only four had clothing which could be described as ‘good’. Those deemed to have nutrition which was ‘slightly subnormal’ or ‘bad’ amounted to 28%, as compared with the national average which showed only 11.5% in these groups for 1935. The Medical Officer also noted that there were a number of undersized boys.

Massey also confirmed the view of Titmuss, Singer and others, that it was the women in these communities who suffered most from ill health, and in a variety of ways. Whilst the men seemed to look their age, with the exception of those suffering from industrial diseases, the women generally looked older than they were due to the hour-by-hour strain and the lack of holidays or any opportunity to leave the home apart from the weekly shopping trip or the occasional visit to the cinema. Women were often reluctant to admit themselves to the hospital, in cases of childbirth or illness, as they thought that the household would get into a muddle in their absence. Massey also noted that there was no birth control clinic in the district and that many women, fearful of having to rear more children on the dole, would undermine their health by using aperients.

The fact that South Wales maintained a relatively high birth rate and a lower-than-average crude death rate throughout the 1930s, enabling it to end the decade with an age structure roughly comparable to that of England and Wales as a whole, should not blind social historians, as it did some contemporaries, to the fact that, according to R. M. Titmuss, as many as sixty-five thousand of its inhabitants may have died ‘avoidable’ deaths in the period 1926-36. There certainly was a good deal of contemporary complacency, as other ‘surveyors’ of the coalfield testified. Hilary A. Marquand of University College, Cardiff, who was to succeed Nye Bevan as Health Minister, warned against this in his (1936) book, South Wales Needs a Plan, and M. P. Fogarty followed this more optimistic, though measured analysis with his post-war report on Prospects of the Industrial Areas of Great Britain.

Contemporary Images of the Coalfield Communities:

But the quantitative evidence only tells part of the story of the decline in health and well-being of the valley communities. Recent historians of inter-war South Wales (over the past half-century) have had to deal with a variety of optimistic and pessimistic definitions and images provided by contemporary social investigators as well as immediate post-war historians. They have written using the familiar tropes of ‘The Distressed Coalfields’, ‘The Depressed Areas’, ‘The Unemployed’, ‘The Black Spots’ and so on. These frequent ‘turns of phrase’ need to be seen alongside the complex realities of life experienced by the coalfield communities and the families and individuals that composed them, which have become blurred into popular images in print and film.

Within a British context, South Wales in the 1930s was viewed as a ‘problem’, a ‘depressed area’ or latterly and more euphemistically, a ‘special area’, following the growing acceptance of the need for ‘Planning’ by leading economists and politicians from the Spring of 1937 onwards with the publication of the journal of the same name by the new forum, Political and Economic Planning. For them, it was a ‘problem’ to be dealt with by national agencies, whether voluntary or state-managed. The ground of the argument was about how to deal with the problem, and most of these agencies arrived in South Wales with a prescription of one type or another, having already made their diagnoses from afar. They then made sure to make that the symptoms fitted these diagnoses. After all, the statistics were now available and formed the bedrock for the formulation of policy.

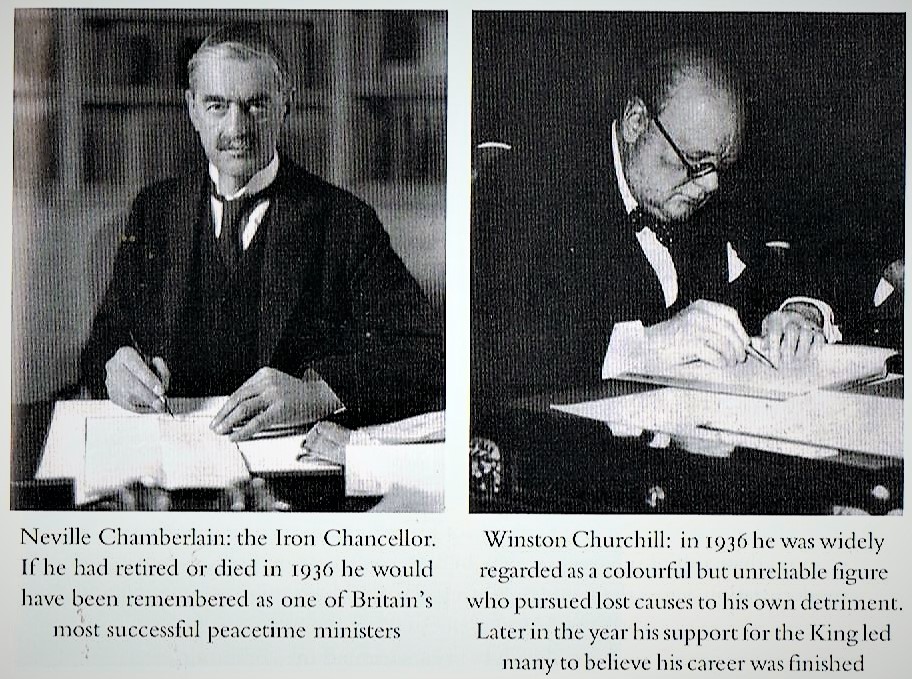

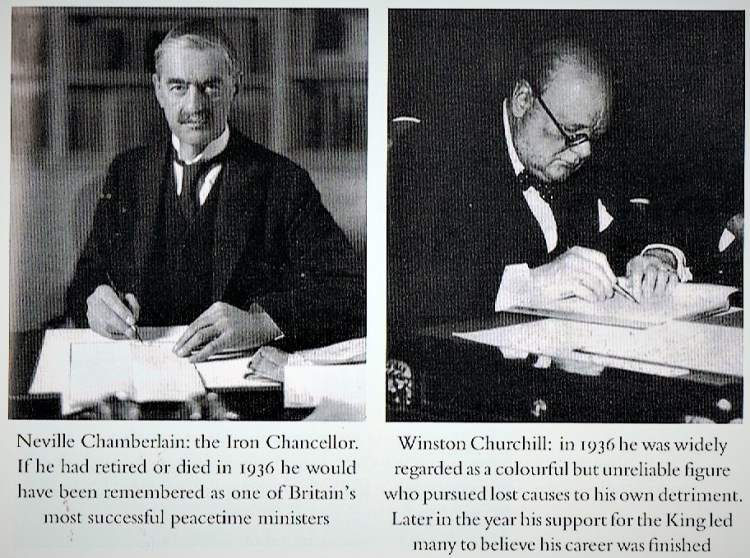

The professional and commercial strata of South Wales society were umbilically attached to a notion of progressive imperialism. The deputation of churchmen who, in July 1937, met Neville Chamberlain, who was steeped in the same Liberal Imperialism that the Birmingham Unitarian dynasty had been for the previous half-century, reflected this:

‘They were there because the community of which they were a part was slowly breaking up… It was a great community and they did not think that the British Empire could afford to see it passing.’

Western Mail, 23 July 1937.

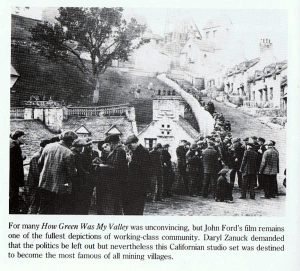

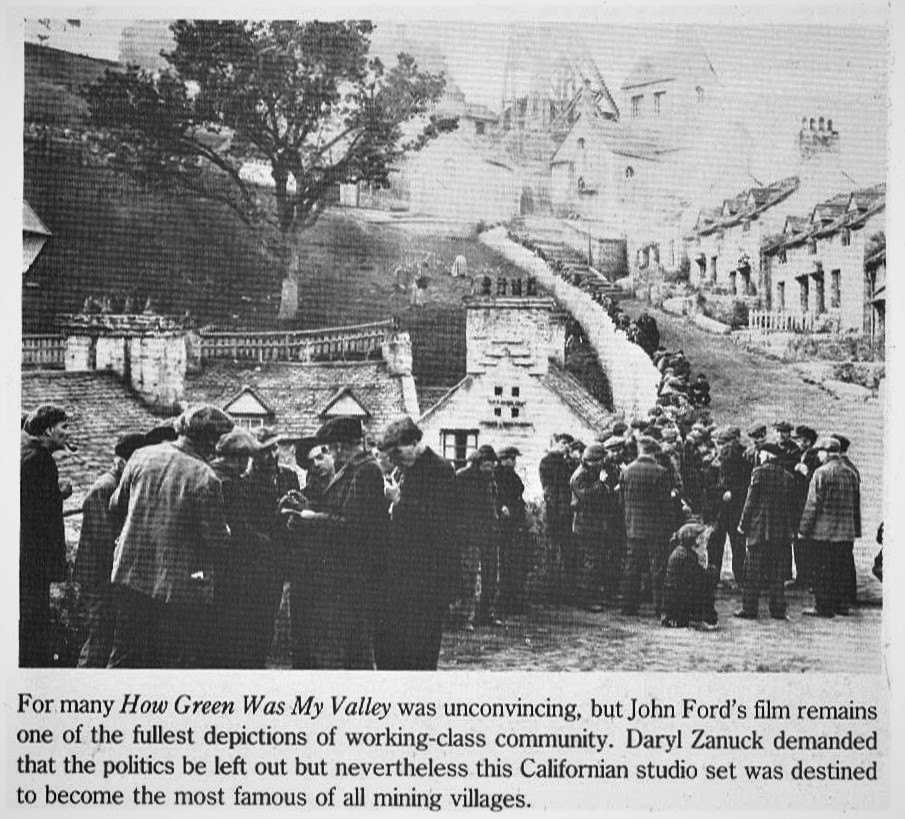

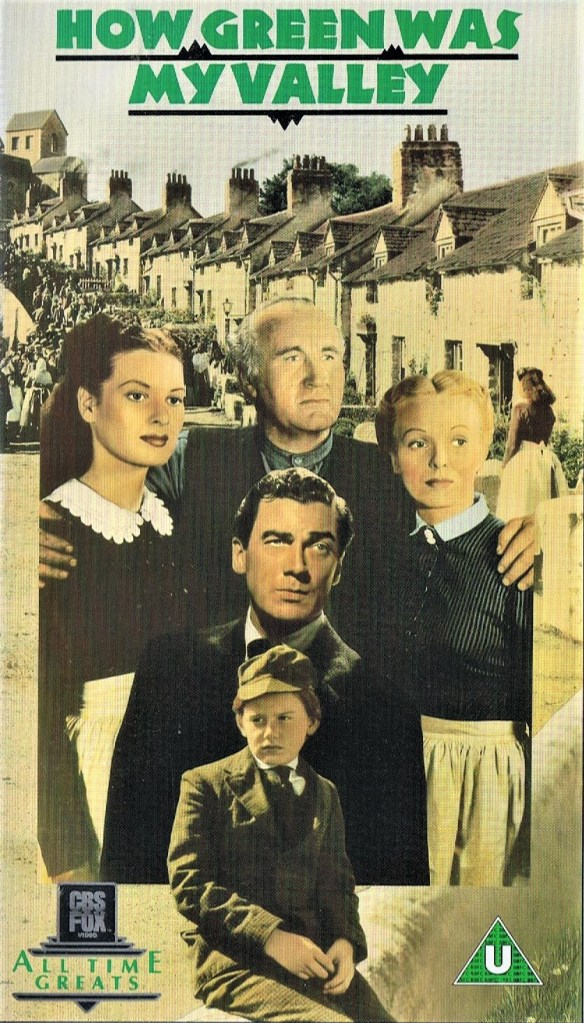

During the 1930s, Hollywood captured the masses in its films, which increasingly appealed to critics and intellectuals. Educated film-goers in Britain were also beginning to appreciate those qualities which the masses had always detected and in particular they were at last spotting that there were forms of ‘social realism’ in American cinema. Peter Stead has written an essay (in Wales, The Imagined Nation: 1986 – see ‘Sources’) about how, together with this realisation, there came a new awareness that it was precisely this quality that was missing in British films. By the late 1930s, there was a crescendo of demand for a fuller sense of Britain in British films. The constant sniping of the critics, the dissatisfaction of directors and the relaxation of censorship all sanctioned the emergence of ‘social cinema’. This was a real turning point in the history of the British film industry, but, hardly surprisingly, it was Hollywood that both inspired and encouraged the change. The dark days of the Great Depression in the United States had taught Hollywood that there were audiences for films that admitted that not all was right with the world.

The British studios duly noted that there were audiences for ‘social problem’ films and that, in any case, the censors were becoming more lenient. Following the 1937 Quota Act, American companies began to establish their own studios around London so that they could make ‘British’ films, and it was under these arrangements that MGM made The Citadel in 1938. Several British critics thought that this was one of the best British films ever made and comments followed about the very apparent American production values, as well as about the emergence of Robert Donat as a Hollywood star. The film also offered an authentic sense of London and South Wales. Hollywood loved middle-brow best-sellers, with libraries and bookshops providing free publicity, and A. J. Cronin was very keen for his story about the ideals of a young doctor to be filmed. He could never have foreseen that the film would be so well made; there were some early location sequences which rooted the film in the South Wales valleys that the documentary directors Ralph Bond, Donald Alexander and John Grierson had already ‘discovered.’ In The Citadel, besides the first-class acting of Donat, Ralph Richardson and Emlyn Williams, who contributed some authentic Welsh dialogue, there was a convincingly detailed denunciation of the evils of private medicine.

Britain was ripe for a socially mature Hollywood film, and the Director, King Vidor, was well known in ‘tinsel town’ for making socially realistic films that reflected his own brand of rural populism: he was very much for the common man and very much against the sharp practices of all corporations and vested interests. The Citadel offered a fuller view of South Wales than any previous feature film, though it made use of the area for the purposes of the narrative, combining Cronin’s melodrama with Vidor’s own philosophy. The film was mainly concerned with the salvation of its hero: the Christian knight, or Anglo-Saxon individualist who had to discover his true self by pointing the masses towards a higher goal. There was, however, no room in the scenario for organised protest or trade unions and so the ‘stupid’ miners are shown to be passive in support of medical progress, held back by the Aberalaw Medical Aid Society, which becomes the metaphor for all the evils associated with any guild or syndicate of workers. At one point, the young doctor’s wife comments, “Did anyone ever try to help the people and the people not object?”

Diagnosing Depression – The ‘Celtic Complex’:

By contrast, the social survey writers frequently set about their task as if they were embarking upon an anthropological expedition. The editor of the journal Fact, prefacing Philip Massey’s Portrait of a Mining Town, asserted the need for ‘an attempt to survey typical corners of Britain as truthfully and painstakingly as if our investigators had been inspecting an African village. ‘ This, apparently, was why a mining ‘town’ was chosen. He stated that, like African villages, mining communities are isolated and relatively easy to study. Clearly, it was this image of geographical isolation which attracted many of these investigators, as it did film directors; it is hardly surprising that their findings, therefore, tended to reflect this image, even though it was not an entirely accurate one in reality. Many of the philanthropists of the 1930s used the image of ‘isolation’ to justify their concept of social service ‘settlements’ in the valleys, as a means by which the outlook of the coalfield communities could be ‘broadened’. They were attempting to infuse a notion of ‘citizenship’ of a wider community extending far beyond the natural boundaries of the valley.

This liberal-nationalist image of the coalfield was essentially that of a society in which industry had distorted nationality and that, to their regret, this had given the South Wales collier a greater affinity to his fellow colliers in Durham and Yorkshire than, for example, to the tin-plate workers of west Wales. This, to them, was to be lamented, and its fundamental cause was seen as the incursion of an alien people bringing with them an alien culture, infecting the very psyche and mentality of the colliers against their better nature. These people, it was claimed, never shared in the inheritance of Welsh culture and Welsh life. They were alien accretions to the population who had gradually stultified the natural development of native culture.

At a time when pseudo-scientific ideas of eugenics dominated political ideas on the continent, the authors of pamphlets and papers on public health and social service in Wales contrasted the Welsh-speaking miners of the anthracite districts of the western coalfield with the recent immigrants in the Eastern Sector who formed a more or less alien population. This, they claimed, accounted for the acceptance by South Wales miners of economic theories and policies which would appear to cut across Welsh tradition. In a similar vein, the ‘old Welsh colliers’ of Welsh-speaking Rhymney were contrasted with those of Blaina by James Evans, General Inspector to the Welsh Board of Health in his paper to the Welsh School of Social Service Conference at Llandrindod Wells in 1928:

‘In this and other districts where the native Welsh culture most strongly persists and the influences of the Methodist revival… are still felt, there is a noticeable difference in the character and outlook of the people as compared with the districts where the industrial revolution submerged the populace and introduced an economic doctrine and a philosophy of life both of which are strange and unsatisfying to the Celtic Complex’.

James Evans, Report on Conditions in South Wales, 24 March, 1928.

The ‘old Welsh collier’ was seen as being ‘independent in spirit’, the last to apply to the Board of Guardians for relief. These ‘liberal-nationalist’ elements within the Ministry of Health were keen to support the work of the Industrial Transference Board, established by the Ministry of Labour in 1928 because they saw in it the means of removing what they viewed as an alien, disruptive element from the coalfield. They, therefore, helped to ensure that the local authorities kept their levels of relief sufficiently low to encourage the acceptance of transference. James Evans, as General Inspector to the Welsh Board of Health, disapproved of the action of the Bedwellty Board of Guardians in Blaina and Nantyglo, in giving out grants of boots, suits of clothes, underclothes, bedclothes and dress material, besides the usual relief in cash and food.

Evans felt that by doing so they were spreading ‘demoralisation’ throughout the district and that there was general agreement among those competent to judge… that the district should, as far as possible, be evacuated. One of the reasons for his support for this proposal was that, in his view, this district was not as Welsh as other areas of the coalfield, where the people were of a ‘better type’. He wrote to H. W. S. Francis, Chamberlain’s Assistant Secretary, urging him to keep to the transference policy and not to give further funds for additional ‘out-relief’. Writing his internal report for the Ministry of Health, Evans was just one among those who believed that the native population of the region had been corrupted by immigrants with an alien culture and ideology. In 1930, The Rev. W. Watkin Davies, the Minister of Edgbaston Congregational Church in Birmingham published his travelogue, A Wayfarer in Wales. In it, he described the coalfield communities as outposts of hell itself with their inhabitants almost to a man, supporters of the left wing of the Labour Party. Nevertheless, he was pleased to find elements of the ‘Celtic Complex’ still finding a ‘congenial home’ in the Rhondda, most notably through the Eisteddfod and in the rendering of Welsh hymn-tunes – and all this despite the ‘admixture of aliens’ in the valleys. He described Merthyr, after a brief visit, as a hideous place, dirty and noisy, and typical of all that is worst about the South Wales Coalfield.

For many of these commentators clinging to the cultural emblems of nonconformist Wales, the coalfield was either a grimy foreign country made up of things which, and people who ‘in no true sense belong to Wales’, as Watkin Davies put it or it was a once noble and pure society which had been desecrated by Mammon and his hosts. Contemporary novelists, especially Richard Llewellyn, saw industrialisation and the resulting immigration into the valleys as a ‘problem’ for the continuity of older Welsh traditions. The central theme of Llewellyn’s (1939) novel, How Green Was My Valley, which was also made into a Hollywood film (1942), is testimony to the widespread acceptance of this explanation of the division between the ‘Coal Complex’ and ‘Celtic Complex’ in the region’s ‘fall from grace’. At the Llanmadoc Conferences held during the war, Welsh ministers were still propagating this image of a coalfield defiled by immigration and industrialisation. Rev. J. Selwyn Roberts of Pontypridd spent only a few lines of his speech dealing with the effect on his community of a decade of large-scale unemployment and emigration, before returning to the theme of the dissolution of the ‘Celtic Complex’ by immigration from the other side of the Severn estuary:

“In addition to those recent losses of its indigenous population by emigration the community life in Wales by emigration, the community life of Wales has also suffered from alien accretions in the past. … The workers who came in from surrounding counties were in the main people who neither brought any definite culture of their own, nor were able to fit into the culture of the Welsh community. This tended to make the bond of community life nothing more than the bond of economic interest, a condition which is fatal to true community life… It is clear that for the last two generations there have been alien factors at work which have almost completely overcome the traditional conscience and spirit of the Welsh people…

Quoted in Pennar Davies et. al., (n. d.), The Welsh Pattern.

Another identifiable set of images was created by a group of ‘propagandists’, and it was these images, in photographs, film and print, which have subsequently been used by historians of the period. Some of them were products of coalfield communities; others were visitors to it. The latter came to the coalfield with a specific purpose in mind, shaped by a belief in a class struggle in which the colliers were in the vanguard. For writers like the avowed Communist Allen Hutt, whose books were intended as propaganda for the times, the South Wales miners were the cream of the working class… the most advanced, most militant, most conscious workers. To add to this neat definition, he gave an equally neat explanation of why they did not rise up against their ‘suffering’:

‘One of the obstacles confronting the revolt of the workers in South Wales is precisely that degradation of which Marx spoke as the accompaniment of the growth of impoverishment under monopoly.’

A. Hutt (1933), The Condition of the Working Class in Britain. London, pp. 44-45.

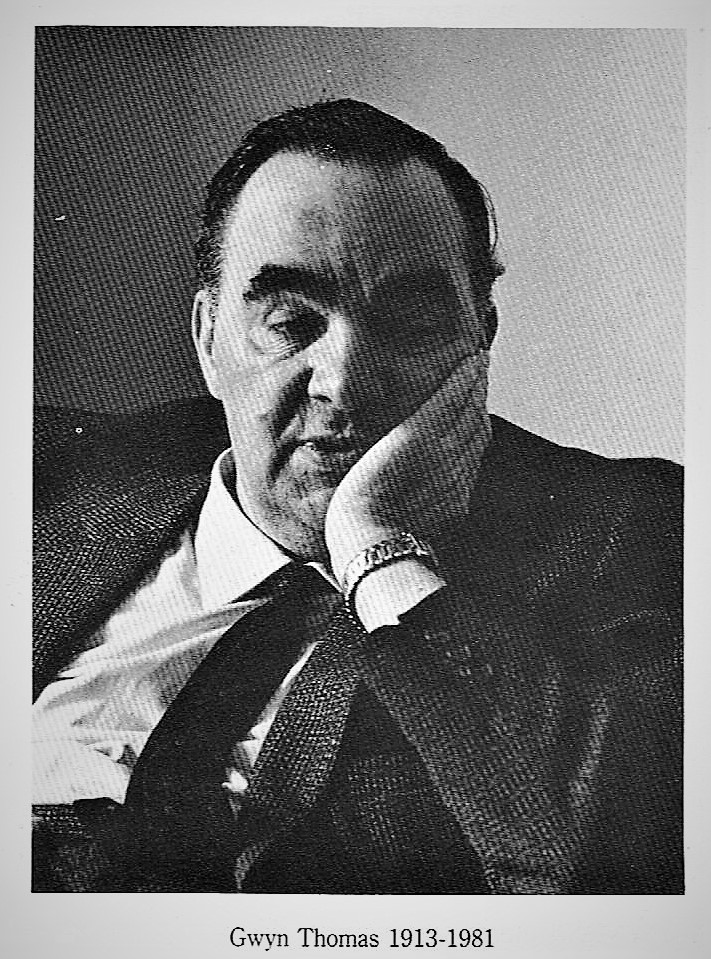

Recent historians have demonstrated how this imagery tended to dominate much of the contemporary discourse, literature, newsreel footage and photography of ‘The Hungry Thirties’ in the coalfield, leaving us to separate the mythology from the real matter of the society itself. The writer Gwyn Thomas, in his (1979) lecture, The Subsidence Factor, described the ‘exodus’ from the Rhondda Valleys, as remembered from his childhood, in a nuanced way, as being like a Black Death on wheels conducted with far less anguish. Historian Dai Smith has written of the socio-economic stereotypes who, black-faced, unemployed or militant, stalk our fictional worlds. In particular, the propagandists’ preconceptions tended to create and perpetuate what may be termed, ‘the myth of the unemployed man’. The stereotyping of ‘the unemployed’ as a uniform group, a ‘standing army’ within British society served the purposes of those who saw the causes of unemployment as correspondingly straightforward. Thus, John Gollan began a chapter on unemployment in his (1937) book, with the following statement:

‘What is unemployment? We would be fools if we thought that unemployment depended merely on the state of trade. Undoubtedly this factor affects the amount of unemployment is absolutely essential for capitalist industry, while under socialism in the USSR it has been abolished completely. Modern capitalist production has established an industrial reserve army – the unemployed; and the existence of this reserve army is essential in order that capital may have a surplus of producers which it can draw upon when needed. Unemployment is the black dog of capitalism …’

J. Gollan (1937), Youth in British Industry: A Survey of Labour Conditions Today. London, p. 155.

Poverty, People and Policy:

By 1929, the number of long-term unemployed was already sizeable in the ‘depressed areas’. In his report to Parliament that February on The Coalfield of South Wales and Monmouth, Neville Chamberlain, then Minister of Health, remarked that many miners had not worked since the 1926 stoppage and that some had not been down a pit since 1921. He commented that even now there are men who regard it as in the natural order of things that they should for all time be provided with the necessities of life without working for them. The intervention of the state in terms of the Unemployment Insurance Act of 1930, which took effect in March under the Labour Government, made it possible for large numbers of workers to survive long periods of unemployment without providing evidence that they were ‘genuinely seeking work’. Its provisions continued in effect until 30 June 1934 when the National Government’s Act establishing the Means Test came into effect.

That this ‘phenomenon’ of long-term unemployment was almost entirely without precedent is shown by Chamberlain’s description of the situation as without parallel in the modern history of this country. He suggested that even ‘the nearest parallel’, that of the Lancashire cotton famine of 1862-64, was ‘not a close one’. Prolonged mass unemployment, distinctly regional in character, was a new social phenomenon which created major problems for ‘Labour’ and ‘Capital’ alike. Given its novelty, it is not surprising that ‘social investigators’ and ‘propagandists’ alike should choose to focus on the long-term unemployed. However, few contemporaries showed any significant awareness of the varying social conditions of unemployed people.

In his (1940) book, Unemployment and the Unemployed, H. W. Singer was scathing about the generalisations in this respect, arguing that there were was no ‘unemployed man’, but only ‘unemployed men’, that there was ‘no uniformity but an intense variety’. He went on to list sixteen independent causes of unemployment and to point out that because work enforced a common routine on the people who took part in it, it was reasonable to expect that when people became unemployed their suppressed individuality would reassert itself. Poverty, the dole queue and the Means Test might all restrict diversity, but that did not mean that the unemployed could be described as:

‘… a uniform mass of caps, grey faces, hand-in-pockets, street-corner men with empty stomachs and on the verge of suicide, and only sustained by the hope of winning the pools…’

H. W. Singer, loc. cit., London, Chapter I, passim.

To begin with, Singer divided Gollan’s ‘reserve army’ into two camps, a ‘stage army’ and a ‘standing army’. Those in the former were the short-term unemployed, out of work for under three months and those in the latter were the long-term unemployed, out of work for twelve months or more. Those in the former category could therefore include workers moving from one form of employment to another, and those ‘laid-off’ or ‘temporarily stopped’ for two or three days a week from the collieries. When temporary unemployment was characterised by the experience of three days’ work and three days’ dole it could be both economically and psychologically more destabilising than being wholly unemployed. One of the few authentic coalface writers, B. L. Coombes commented in his influential (1939) book, These Poor Hands: The Autobiography of a Miner Working in South Wales, that when the Colliery managers called them for a fourth shift, their feelings were not very pleasant, because they knew that had they not been called they would have been able to claim three days’ dole. Despite working all spring and summer, he was not a penny better off than if he had been on the dole. But, he wrote, his case was ‘an average’ one; the older men with big families who had a shilling a day to pay for bus fares were actually losing money by working four days a week.

Men like Coombes who were either young or fit enough to keep working continued to work in the hope that their colliery would soon return to working six shifts, and they would be paid a full-time wage. At the same time, they had to adapt to new methods of coal-cutting by machine. Coombes was a skilled machine operator and well-adapted to the ‘speed-up’ which was happening throughout the coalfield by the mid-thirties. Those who ran a high risk of being relegated to the ranks of the ‘standing army’ of the long-term unemployed were the older colliers who found it harder to get back to the coal face after a temporary stoppage because of their comparative lack of experience using mechanised coal-cutters. The introduction of these did much to destroy the craftsman spirit in the mines and reduced the number of miners required for a specific job, plus it did little to provide higher wages and better conditions for those remaining in the industry. In fact, wages remained depressed throughout most of the period and the ‘speed-up’ that mechanisation entailed led to the repeated claim that conditions were becoming ‘murderous’.

Those among these older colliers who were no longer able to find a ‘place’ underground worked under the constant fear of joining the dole queue on a permanent basis, as did those men advancing towards middle age. Their fear, and the manner in which they tried to hide their poor health as a result, is vividly illustrated by the following passage from Coombes’ book:

‘I sympathise with the older men, and watch their struggle to keep up. I listen to the labour of their dust-clogged chests when they climb the drift to go out. They climb a few steps, pause to regain their breath and watch the younger ones hurry past. Down that coal-drift rushes a current of air that is forced and always ice-cold. This meets the sweating men as they come up and chills them to their insides. It tells on chests that are already weakened by clogging dust and the rush of work.

‘I watch how the few men who are old come to work; how weary they look; how their faces seem almost as grey as their hair; how desperate they are that the officials shall not think they are slower at work than the younger men. I can read the question that is always in their minds:

“How many more times can I obey the call of the hooter? And after I have failed, what then?”

Coombes, loc. cit., p. 222.

For the twenty thousand who were over fifty and were considered to have ‘failed’ and were unlikely to work again, there was a threefold problem. They had lost their sense of purpose as skilled, active workers and bread-winners for their families; relationships with younger, working members of the family became more difficult, particularly if these members were working away from home, and thirdly, they found it impossible to make any kind of provision which would enable them to keep up the home’s standard of living when they reached the old age pension age. The effect of the high level of unionisation in the Coalfield had kept the wage rates much higher than in many other areas of Britain, but the unemployment allowance system on which the long-term unemployed depended, took little account of regional variations.

A skilled collier in prosperous times may have brought home the equivalent of a wage of anything up to eight pounds per week, and when multiple members of the family were earning the economic standard of the family might well have been higher than an ordinary lower middle-class family such as a shopkeeper’s family in coalfield communities. The maintenance system, however, would mean an immediate drop in income of at least a pound a week, even starting from the more precarious levels of pay which existed in the mining industry in the 1930s. The contrast with the older collier’s memory of the relatively prosperous early twenties:

‘It is just the extent of this drop … which will largely determine an unemployed man’s attitude to unemployment … It is, therefore, the skilled men… that are feeling the edge of their condition of unemployment most keenly, because it is these people that are in fact being penalised by the existing system of ‘welfare’.’

Singer (1940), op. cit., pp. 15, 95-6, 112.

The Break-up of the Coal Complex:

In addition to the problems of the older colliers, youths no longer had the opportunity of learning the craft under skilled colliers, and in many districts, considerable numbers of them were dispensed with some time between their eighteenth and twenty-first birthdays. Moreover, the operation of the Seniority Rule often discriminated against younger men, thus providing them with a strong motive for migration. An array of sources provide evidence that there was a growing antipathy towards coal mining among both young men and their parents.

In his visit to South Wales in June 1929, an official at the Ministry of Labour found that parents were increasingly in favour of their boys migrating rather than working underground, despite the fact that the employment situation had improved to the point where there was a fresh demand for juvenile labour. Another report that year revealed that boys had refused the offer of underground employment in the hope of securing employment in England. In January 1934, the Juvenile Employment Officer for Merthyr reported that of the boys due to leave school at the end of term, less than seventeen per cent expressed a preference for colliery work. A quarter of them stated that they had no particular preference but invariably added that they did not want to work underground. By comparison, a quarter wanted to enter the distributive trades and ten per cent stated a preference for engineering.

This new attitude was shared by parents and offspring alike. In Abertillery, it was reported that most of the boys leaving school in 1932 were anxious to obtain employment other than mining and that their mothers were ’empathetic’ that they should not face the same hardships and unemployment as their fathers… It was the changed nature of the work involved as well as its current insecurity which promoted a preference for migration or transference. The evidence from government enquiries was well supported by impressionistic evidence from social investigators. In his survey of Nantyglo and Blaina, Philip Massey reported that migration was playing its role in the broadening of the minds of the population. He detected the erosion of what he called the coal complex.

A further ‘Investigation’ into the matter by the Ministry of Labour in 1934 found that there were 148 boys unemployed in areas where there were unfilled local vacancies in coal mining. Although only twenty-nine of these boys had stated that they were unwilling to accept mining employment, the report concluded that this antipathy was widespread. The shortage of boys wishing to enter coal mining was most marked in the Ferndale employment exchange area, although managers of all the South Wales exchanges covered by the enquiry reported this changed attitude towards pit work.

Few writers attempted to let ‘the unemployed man’ speak for himself, however, let alone their wives and children. James Hanley did so deliberately in his 1937 work, Grey Children: A Study in Humbug. A number of those interviewed by Hanley also reflected this erosion of the Coal Complex and the concurrent desire of young people in the community to ‘better themselves.’ This desire was often prompted by the extensive reading which lengthy unemployment provided time for. The following quotations from Hanley’s witnesses reveal this connection between migration, a growing disenchantment with coal mining and a broadening industrial consciousness among young men in coalfield communities:

John Jones, forty-six-year-old unemployed miner:

“Lots of them like the open-air life and have come to hate the mine and all it stands for. Many miners refuse to let their boys go below. It’s worrying the owners a lot, I can tell you. There’s a generation that’s grown up now with their eyes wide open, and it looked around and it saw things, and it has seen too the lousy deal that miners have had ever since mines were sunk and they’re having nothing of it… just look at the large-scale emigration from these valleys… most of the young fellows have gone south to England. Just look at Slough and Oxford and London.” It’s not only the absence of work for their fathers and themselves, it’s the… instinctive knowledge that all they’ll get out of it will be the same deal as their fathers had…

“…young fellers … see us who’ve spent a lifetime at it, and they say to themselves, B- it, if that’s what you get out of a lifetime of hard toil under the earth, then to hell with it … the best blood in the land has flowed elsewhere…

A lad who had walked to Oxford and back again, looking for a job at the Morris works, and trying this or that factory or foundry on his way down, but all without successs… : “I’d rather get a job anywhere than in a pit. I wish my family would leeave Wales altogether. It’s so miserable.”

Hanley, loc. cit., pp. 20-21, 131-2, 205-7.

Similarly, the American writer Eli Ginzberg recorded that many of those who left Wales looked forward in a spirit of adventure to settling in communities where coal mining was not the sole occupation. He traced the break-up of the Coal Complex to the summer of 1926, and the freedom from the mines which the stoppage provided. This had prompted many, he argued, to question the advantages of coal mining, a questioning which was intensified by the worsening conditions and reduced pay which followed the return to work at the end of the six-month lock-out. Moreover, the social tensions and divisions which followed the strike, such as in the Garw District, made men more willing to break away and start anew in strange surroundings. Respect for the traditional solidarity of the coalfield communities had been undermined. Migration was therefore not simply a response to unemployment in the coal mining industry, but a rejection of the industry itself. In London, Miles Davies found that the sole factor keeping many immigrants from returning to Wales was their antipathy for colliery work:

Nearly all those who said they would prefer to live in the valleys, made it clear that that they would only return to a job as good, or in the same trade as the one they now hold, and that on no account would they return to work underground. One man in the discussion told how struck he had been on returning to his home village on holiday after several years absence, with the exhaustion of the men he met going home from the pit. He attributed this to the ‘speeding-up processes’ which have been introduced in recent years.

NCVO/NCSS papers; typescript report on Migration to London from South Wales, n.d.

Mothers & the Means Test – its Operation & Opposition:

Women became even more antipathetic to the mines as a result of their struggle to manage falling and uncertain wages, and they sought other occupations for their sons. Among those quoted by Hanley was John Williams, who commented on his wife’s mental health:

‘ “My missus is in a mental home. We had a nice little lad, and were not doing so bad until I lost my job, and that and one thing and another, well, I suppose it got to her in that way.” ‘

James Hanley, loc. cit., pp. 9-10.

An unemployed miner’s son also told Hanley of the effect that the introduction of the Means Test had on housewives:

‘ “We’re on the Means Test now. Yesterday I was sitting in the kitchen when the man came in. It made me mad the way he questioned my mother. She got all fluttery and worried, I thought she was going to run into the street. She’s not used to it … Mother is very good in spite of the conditions. It’s wives and mothers who are the real heroines. …” ‘

Hanley, loc. cit., pp. 12-15.

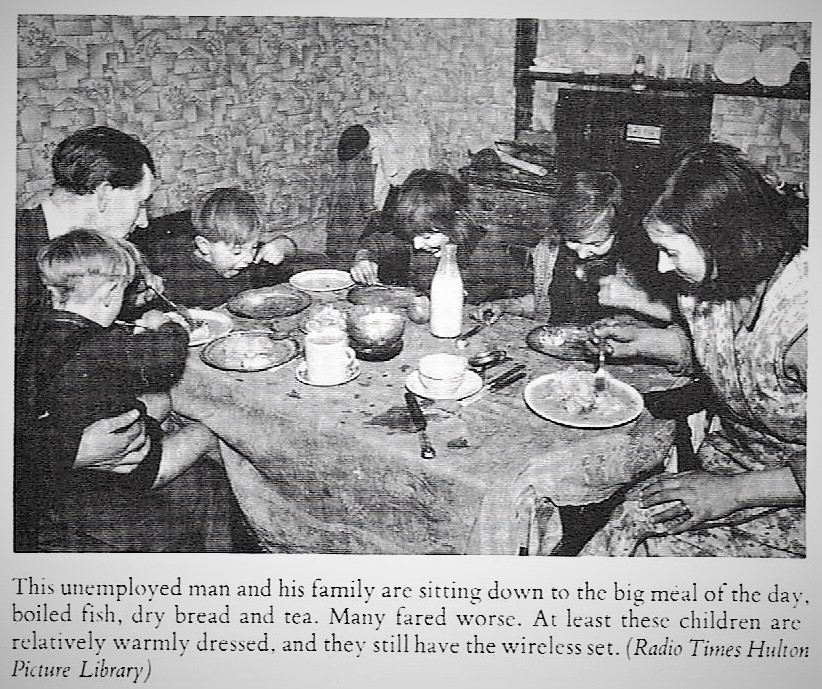

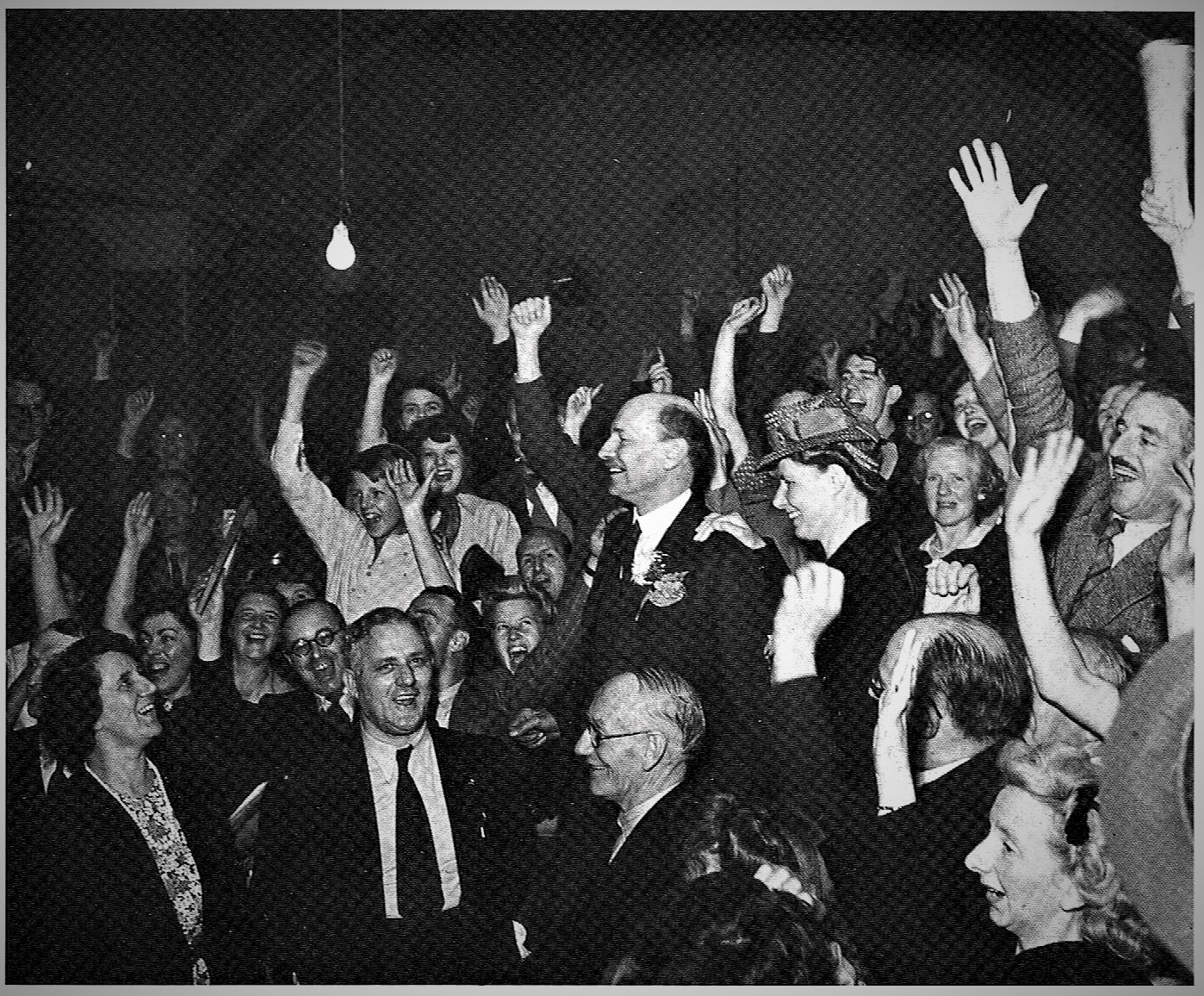

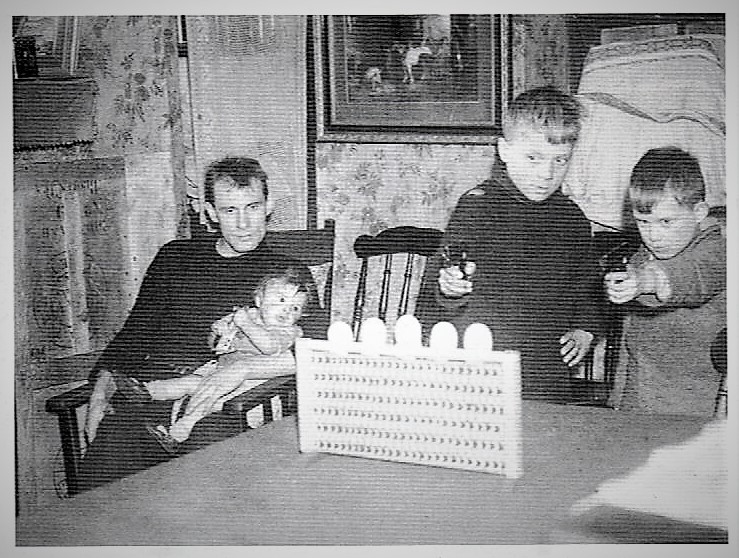

John Gorman wrote in the introduction to his Photographic Remembrance of Working Class Life (1980), that if the means test was synonymous with poverty, then poverty was synonymous with South Wales. In Merthyr in 1936, unemployment was almost sixty per cent nine thousand), and more than seventy per cent of the unemployed were subjected to the means test. Clothes were threadbare, he went on, boots a luxury, soup kitchens a necessity and prosperity a fantasy. Public opinion against the ‘wickedness’ of the principle of means-testing families reached its crescendo in the second half of that year. The iniquitous and petty economies of the National Government that brought acrimony and family division to the tables of the poor were hated across Britain, particularly by those subjected to the bureaucratic inquisition involved. A worker with a newborn child would claim the allowance, only to be asked whether the child was being breastfed. If the answer was yes, the benefit was cut. A fourteen-year-old ‘errand’ boy had his earnings counted and the family benefit was cut accordingly because the son was expected to keep his unemployed father. Mothers deprived themselves of food to feed their children, who went without boots since there was not enough money for food and boots. In the winter months, coal had to be bought for four pennyworths at a time as families struggled to exist without the miner’s allowance and on means-tested benefits.

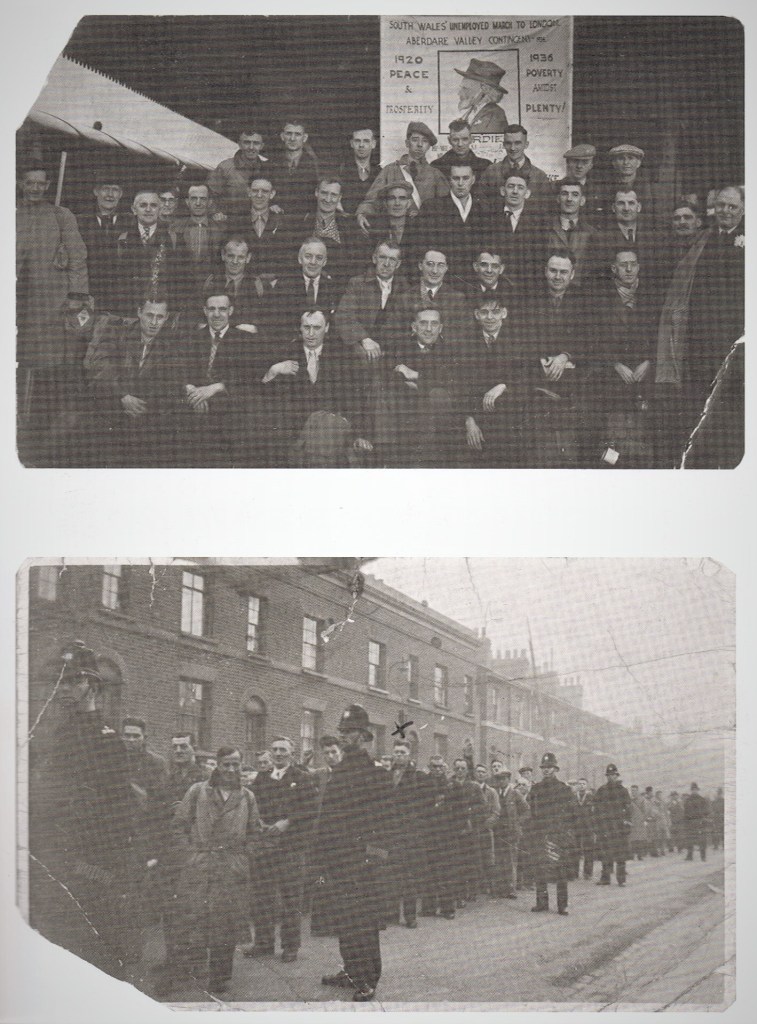

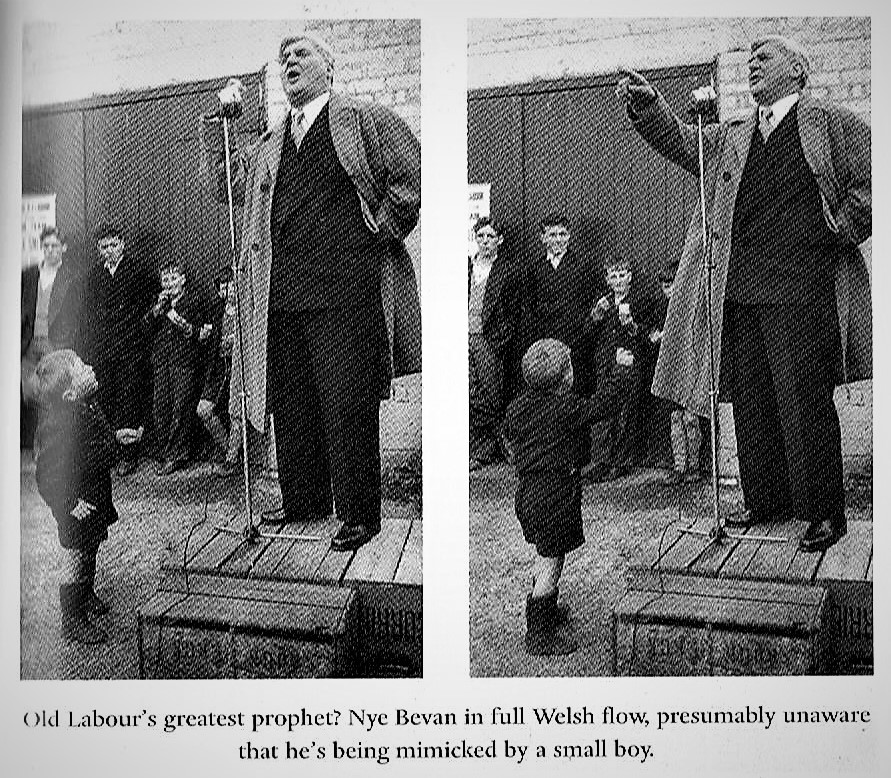

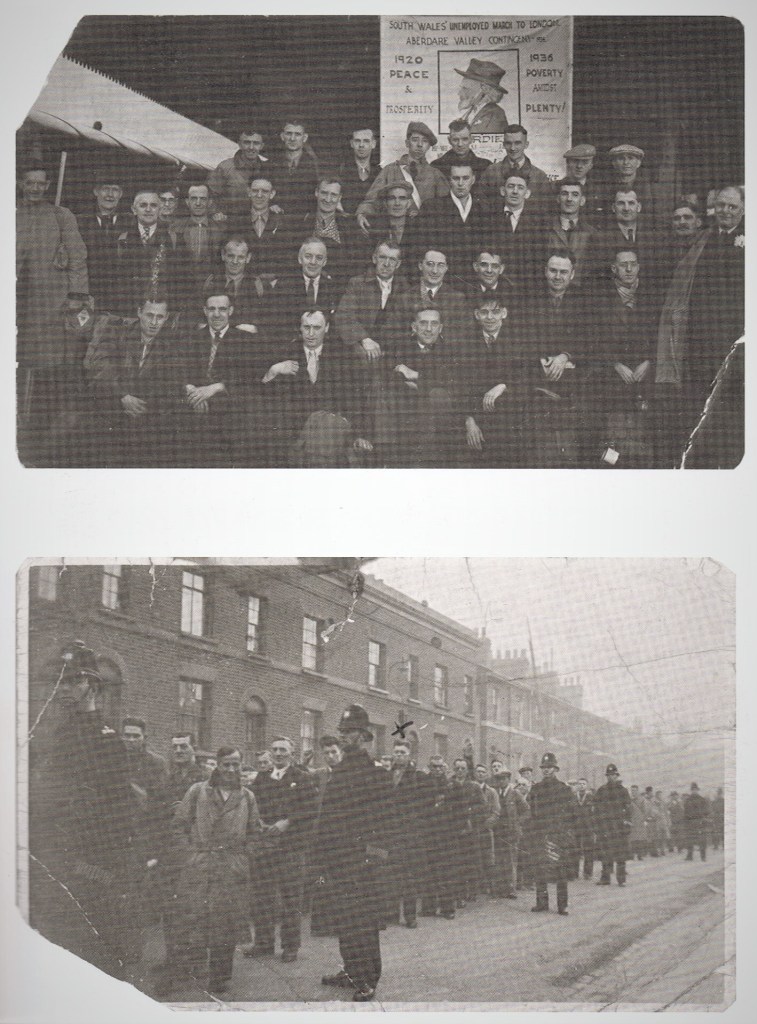

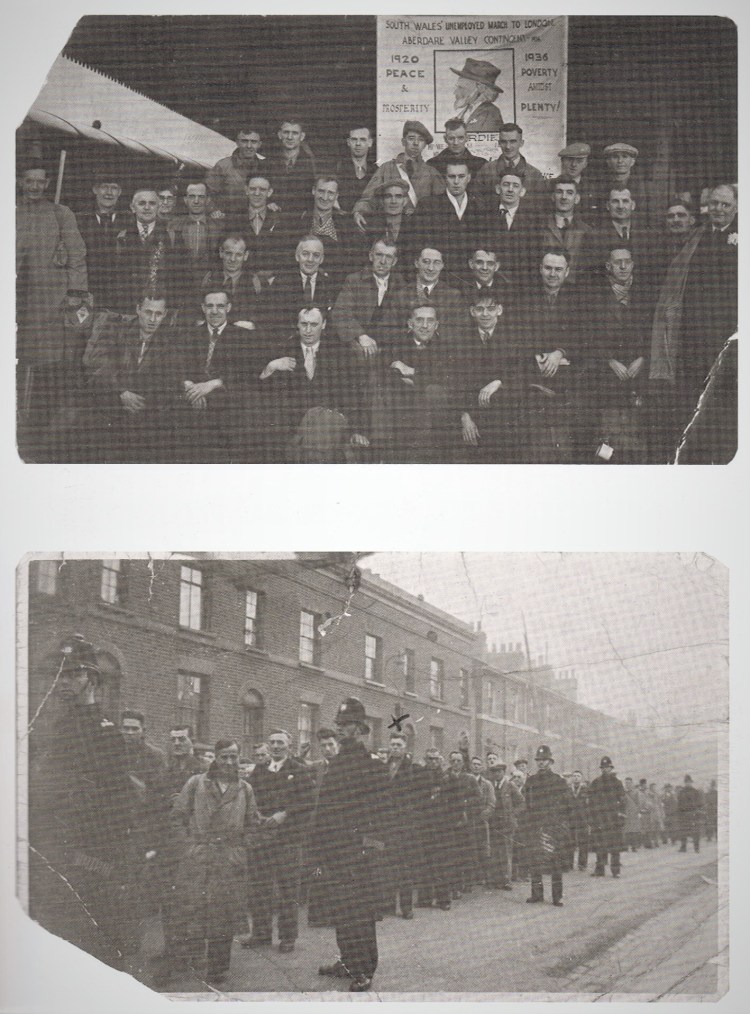

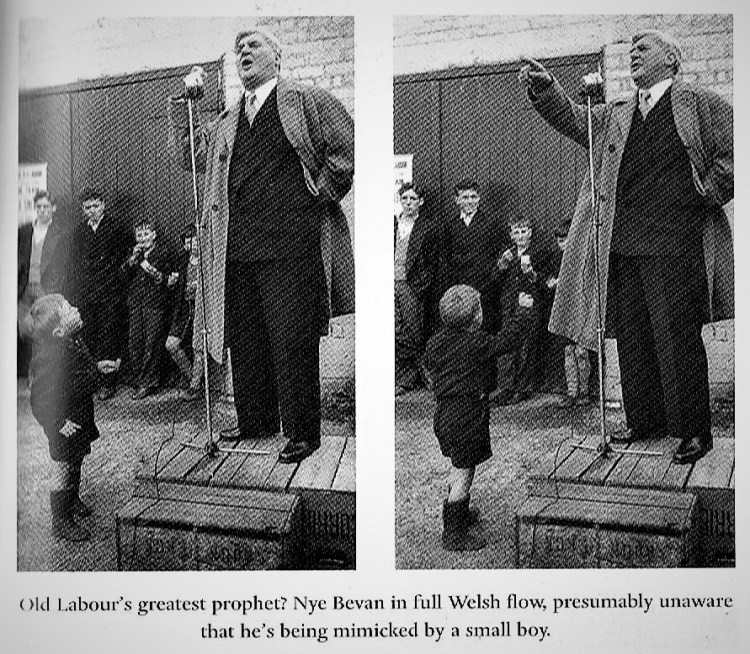

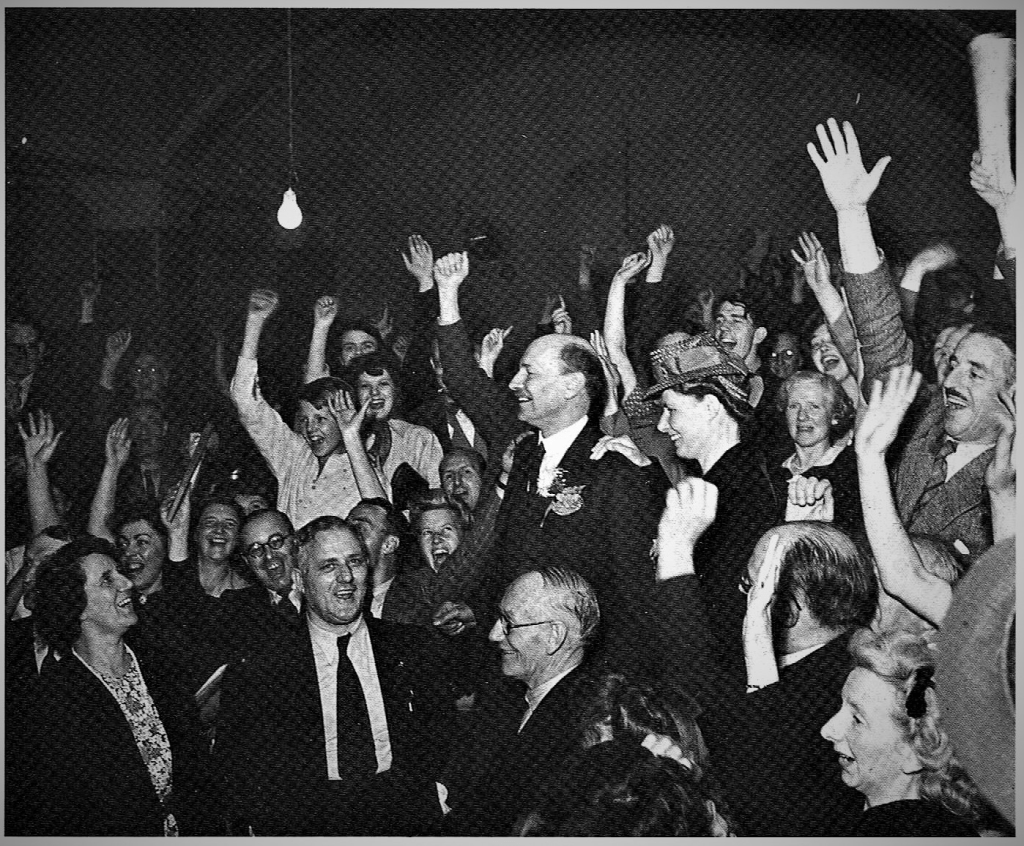

A Welsh contingent of eight hundred took part in the biggest and most united of the hunger marches against the means test in November 1936. Two postcard-sized photographs are shown above. The first appeared in Michael Foot’s biography of Aneurin Bevan (Vol. 1), and was taken by Trevor Roberts, an unemployed miner who marched with the Mountain Ash column and is seen standing next to the banner from the Aberdare Valley with a portrait of Keir Hardie and emblazoned with 1936, Poverty amidst Plenty. This group photograph, taken at Abercynon station on departure to Cardiff for the assembly point, includes officials from the trades councils in the Cynon Valley and Labour councillors. When the South Wales marchers, carrying the Cynon Valley banner reached Slough, they were met by eleven thousand, for by that time Slough had become a ‘little Wales’, peopled by those who had fled the ‘valleys of death’. The marchers joined the quarter of a million at a huge demonstration in Hyde Park. The speakers included Aneurin Bevan who said:

“The hunger marchers have achieved one thing. They have for the first time in the history of the Labour movement achieved a united platform. Communists, ILPers, Socialists, members of the Labour Party and Co-operators for the first time have joined hands and we are not going to unclasp them.”

Quoted in Gorman (1980), p. 28.

The second photograph (above) shows some of the Welsh marchers lining up at Cater Street School, Camberwell, where they had spent the night prior to the march to the Hyde Park rally. Clement Attlee, newly elected as Labour leader, also spoke at the rally, moving the resolution:

‘The scales (of unemployment benefit) are insufficient to meet the bare physical needs of the unemployed…’

Ibid.

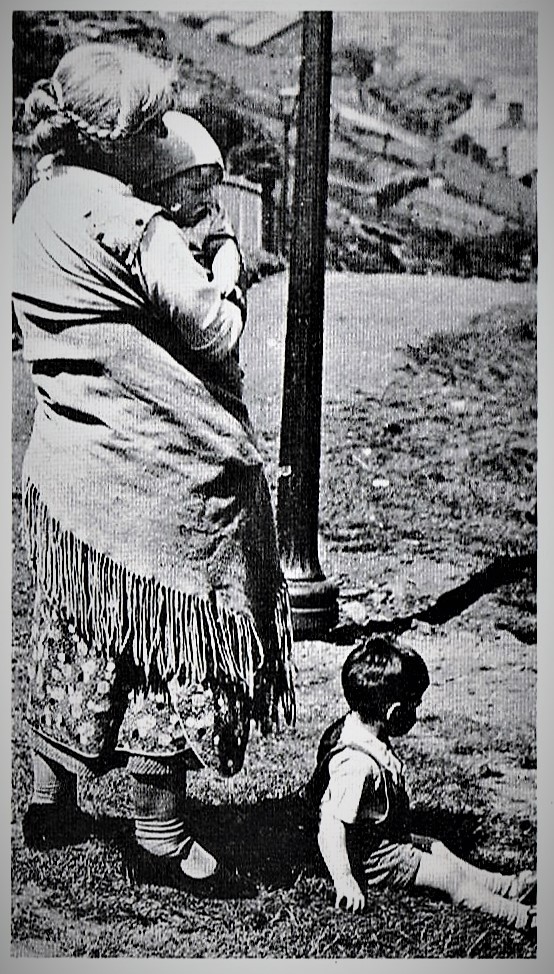

A contingent of women marchers is shown below:

The Drivers of Migration & the Obstacles to Transference:

But by the winter of 1936-37, it was no longer simply the appalling conditions accompanying long-term unemployment that drove people out of the valleys to Slough, Oxford and beyond. This author’s own oral interviews in the early 1980s with Welsh exiles in England also bear out the importance of the break-up of the ‘coal complex’ as a major factor in prompting migration. Some individuals who moved did so because they had ‘had enough’ of the mines, whether or not they were unemployed at the time. Despite having members working, some families decided to move to keep younger members from working underground. Young girls were allowed to leave home in larger numbers to go into domestic service, as they had done in Edwardian times because their parents did not want them to marry miners. The post-war shortage in ‘domestics’ led to the advertisement pages of the South Wales press being filled with exaggerated claims about the prospects awaiting young women in English towns as well as in Cardiff and Swansea. Many of the realities failed to these claims, but there is little evidence to suggest that reports of poor conditions or even deaths from tuberculosis restricted the flow of girls from the valleys.

In 1934, 67% of girls about to leave Merthyr’s schools expressed a preference for domestic service. Some would treat this employment as a short-term experience, after which they would go home to play a new role in the family or get married. This tendency was often strengthened by the erosion in the health of their mothers. At the same time, many young men, despite strong pressures to return, would not do so even when the coal industry recovered and jobs became available for them in the collieries. Nevertheless, many others saw their migration as a short-term experience, like that of their sisters. They left home out of a sense of boredom or frustration, often with vague plans. Those who stayed in the new areas often did so having moved on from temporary domestic service or distributive jobs to more lucrative employment in the manufacturing industries.

Despite all the financial incentives for young people to transfer under state supervision, the numbers doing so were very small compared to the volume of those who moved under their own devices and on their own terms, in keeping with the traditions of migration within these communities. To have accepted dependence on the state would, for many, have been an acceptance of their own demoralisation. The purpose of migration was, after all, to escape from what Hanley described as this mass of degradation, and the stink of charity in one’s nostrils everywhere.

In his first Industrial Survey of 1931, Professor Hilary Marquand commented that so large a volume of migration had already taken place, it followed that the surplus which remained consisted mainly of persons whom it was especially difficult to transfer. These included men who needed a long period of ‘reconditioning’ to make them fit for regular work. One of the most significant obstacles to both transference and migration was the widespread ill health bred by poverty and malnutrition. During the first year of the Industrial Transference Scheme, Ministry of Labour officials recognised that, among the men transferred from the depressed areas, there were many who proved unfit for the employment which was found for them and many more who developed sicknesses in their new jobs, due to the fact that long periods of unemployment had sapped their strength.

In the Autumn of 1929, the Ministry interviewed 35,715 workmen in the depressed areas aged between eighteen and forty-five who had been unemployed for at least three months. Of these, 17,262 (48%) were from the South Wales coalfield, and 27% were said to be ‘reconditioning’ prior to transfer, compared with 25% of the workmen in five areas overall. Of the Welsh sample, 85% in this condition were coal miners, compared to 76% in the five areas as a whole and it was evident from these findings that continuous unemployment had pressed even more seriously upon miners than upon other workers in the heavy industries. Moreover, a further sizeable proportion of the unemployed was deemed completely unfit for transfer, though it is impossible to quantify this precisely because the survey grouped these together with those who were ‘unable’ or ‘unwilling’ to transfer.

The health problems did not just affect the older segments of the insured population. In 1938 the Merthyr Juvenile Employment Committee (JEC) expressed its concern that out of twelve boys who went for medical examination before being transferred, only one was passed physically fit. Nine others were sent for reconditioning to the Llandough Junior Training Centre, leaving two deemed unfit for transfer. The Junior Transference Centre which was established at Llandough Castle near Cowbridge for boys who had already accepted transference to another area. They remained at the centre for a period of six to twelve weeks, during which time they were they were treated for malnutrition under the direction of the Centre’s own Medical Officer, and their physical training took the form of sporting activity rather than the hard, manual labour that adult transferees were subjected to at the Instructional Centres. King Edward VIII had visited Llandough in November 1936, with the boys on the scheme lining the route, banging the tools of the trades that they were learning: shovels, saws, dustpans and brushes. The centre also trained fourteen-year-old girls to go away into domestic service. This form of transference led to dislocation and loneliness for thousands of juveniles. The Merthyr JEC, however, received a glowing report on the Llandough Centre in its minutes for September 1939:

‘There are rooms for educational activities, metalwork, woodwork, a common room and also a large glass-covered hall which is suitable for light physical training during inclement weather… A small bathing pool has been constructed in the wooded section of the grounds where the boys swim if they so desire… they were very happy and agreed that the conditions and food were very good.’

Merthyr Education Committee Minutes, 19 September 1939.

By contrast, the poverty of diet that had been endured by many young transferees, many of them already forced to live away from their parental home due to the operation of the Means Test, is revealed by Hanley’s less formal enquiries:

It has already been seen that young people who have left Wales and gone elsewhere and have got work and gone into lodgings, have vomited up whatever first wholesome meal they have had served up to them by their landladies. I verified five instances of this.

Hanley, loc. cit., p. 130.

There were thus a number of secondary economic and cultural factors involved in the complex causation of migration, many of them connected with physical and mental health. Deteriorating housing, unhealthy and overcrowded living conditions combined with high rents and rates together with depressed incomes all played an essential part in the decision-making of potential migrants. The following quotation from Hanley’s interview with an unemployed miner, John Jones, is revealing in this respect:

‘ “Now we’re Welsh. We’re a proud people and also have a code of manners that the English quite misunderstand … when I was in work nobody interfered with me … From being just an ordinary working miner I’ve become quite an important person. We’ve all become quite important you might say. Just look at the number of people who and associations who are concerned about us! I draw the dole; well there’s quite an army of officials there, … when my benefit ceases, I go to the public relief offices. … Then there’s my union, my lodge, the welfare centres, the means test officials, the housing inspectors … An unemployed man is just ringed around with all kinds of officials and all kind of people interested in in his welfare … I want work and I want to be left alone.” ‘

Hanley, loc. cit., pp. 91, 162.

There is here a direct refusal to become demoralised, despite the pressure from officials and ‘voluntary’ social workers. In this context, both the miners’ lodges and their institutes played a significant role in upholding morale from the 1926 lock-out to the stay-down strikes against company unionism of the late 1930s. An American visitor to the coalfield, Eli Ginzberg, wrote Grass on the Slag-heaps: The Story of the Welsh Miners (New York, 1942), described how the threat to the miners’ institutes from the new social service centres was, in part, self-induced by the failure of the lodges and ‘the Fed’ failed to come to terms organisationally with the sudden impact of mass, long-term unemployment.

‘Removing’ or ‘Reviving’ the Blackspots:

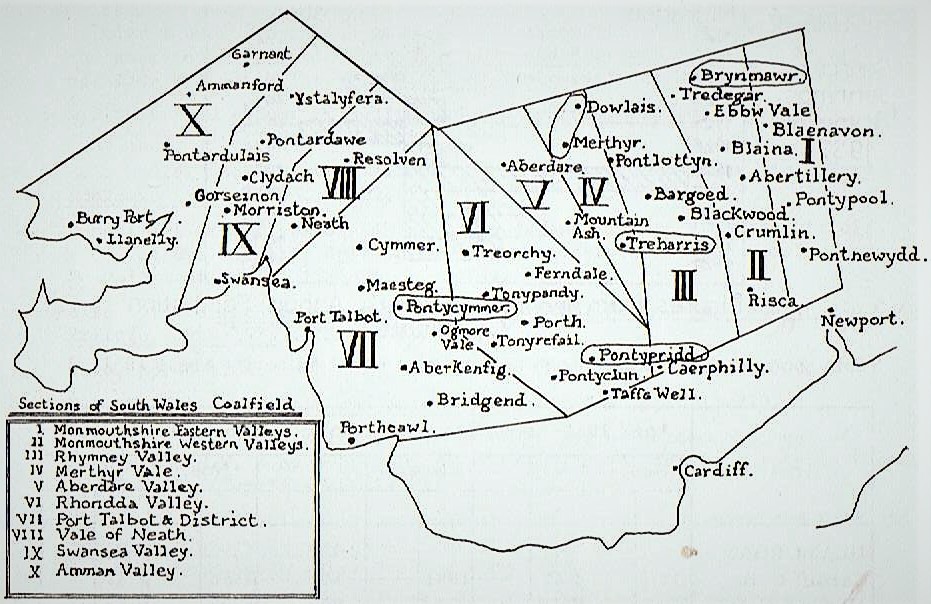

Many of the communities which experienced the highest levels of long-term unemployment were at the heads of the valleys, like Dowlais, Merthyr, Brynmawr, Nantyglo and Blaina forming, according to Marquand’s second (1937) Survey (Vol. III), a melancholy line of semi-derelict communities along the Merthyr to Abergavenny road. But much of the Survey on Brynmawr, led by the Quaker Hilda Jennings, was coloured by a eulogy of the rural heritage of the Welsh people. J. Kitchener Davies, reporting on the Welsh Nationist Party’s Summer School, held in Brynmawr, contrasted the town with its more urban neighbours:

‘ “Brynmawr… suffers from the advertisement of its poverty which had made us expect distress writ larger over it than over any other mining community. This is not so… (it) has a lovely open country, easily accessible, and this… reflected in the faces of the people, made a contrast with those of more hemmed-in communities.” ‘

The Welsh Nationalist, September 1932, p. 6.

P. B. Mais, a traveller along the Highways and Byways of the Welsh Marches in the late thirties, seemed to go into ‘culture shock’ as he came down from the Brecon Beacons (Bannau Brycheiniog) to discover the town, with these unbelievably narrow, wedged rows and rows of miners’ cottages huddled in a land where there was so much room.

… ill-nourished children playing in the over-heated, crowded streets, or in the filthy, offal-laden, tin-strewn streams at the backs of the houses with little strips of backyards that make the Limehouse backyards look like the Garden of Eden.

P. B. Mais (1939), op.cit.

Mais could not believe that Merthyr people could live in such conditions:

Are they not sprung from hillsmen, farmers, men and women who regard air and space to breathe as essentials of life? Why then, do these people go on living here? All of these South Wales mining villages want wiping out of existence, so that the men and women can start again in surroundings that are civilised, and not so ugly as to make one shiver even in memory.

Idem.

Fenner Brockway, who may be described as a contemporary ‘propagandist’, at the opposite pole of public opinion, nevertheless seemed to share this view of the town, as he used the town for his 1932 study, Hungry England (London, pp. 144, 158). His chapter naturally painted the bleakest possible portrait of the poverty and ill health among the borough’s people. Three years later, the Government appointed two commissioners to go to Merthyr, gather evidence and produce a report and recommendations on whether Merthyr should have its county borough status taken away from it. Public Assistance was costing well over half the Corporation’s yearly expenditure and twice its rateable value. The loss of rates from the closing of the Dowlais Steel Works alone amounted to Ł30,000 per annum. Since it received only minimal grants from the central government, it was forced to cut services. John Rowland of the Welsh Board of Health presented the following image of the coalfield society as one of impoverishment and demoralisation within the Borough as minatory to the health of ‘the old Welsh stock’ living there:

The prevailing impression after all my dealings with Merthyr Tydfil is of the real poverty that exists. This poverty is visible everywhere, derelict shops… and deplorable housing conditions. Merthyr is inhabited by many worthy of old Welsh stock, hard-working and religious… it is very hard to see such people gradually losing their faith in the old established order and turning to look for desperate remedies.

Recommendations of the Royal Commission; Report of John Rowland of the Welsh Board of Health.

A very different image of the Borough and its people was given by the local MP, S. O. Davies on behalf of the Trades Council. He articulated the self-image from within the community as one of communal resilience in the face of worsening conditions. This resilience would be undermined by the removal of the Borough’s civic powers. He commented that…

… there is not an institution in this borough today, whether it is a chapel or a church or anything else, that is not with the local authority contributing with a view to mitigating the worst consequences of poverty. … if the authority administering the area is to be removed twenty or thirty miles away, then I say that that … human interest, the whole of what is best in the borough, shown in its children, and those who are most impoverished, will undoubtedly be impaired very considerably…

Royal Commission Minutes of Evidence, Merthyr Library copy p. 38, statement of evidence by S. O. Davies, M. P.

Thomas Jones, the archetypal establishment Welshman, parodied the approach of many of the ‘social investigators’ with whom he came into contact by suggesting that the entire population of South Wales should be transferred out of the region so that the valleys could then be flooded, or used as an industrial museum, or for bombing practice.

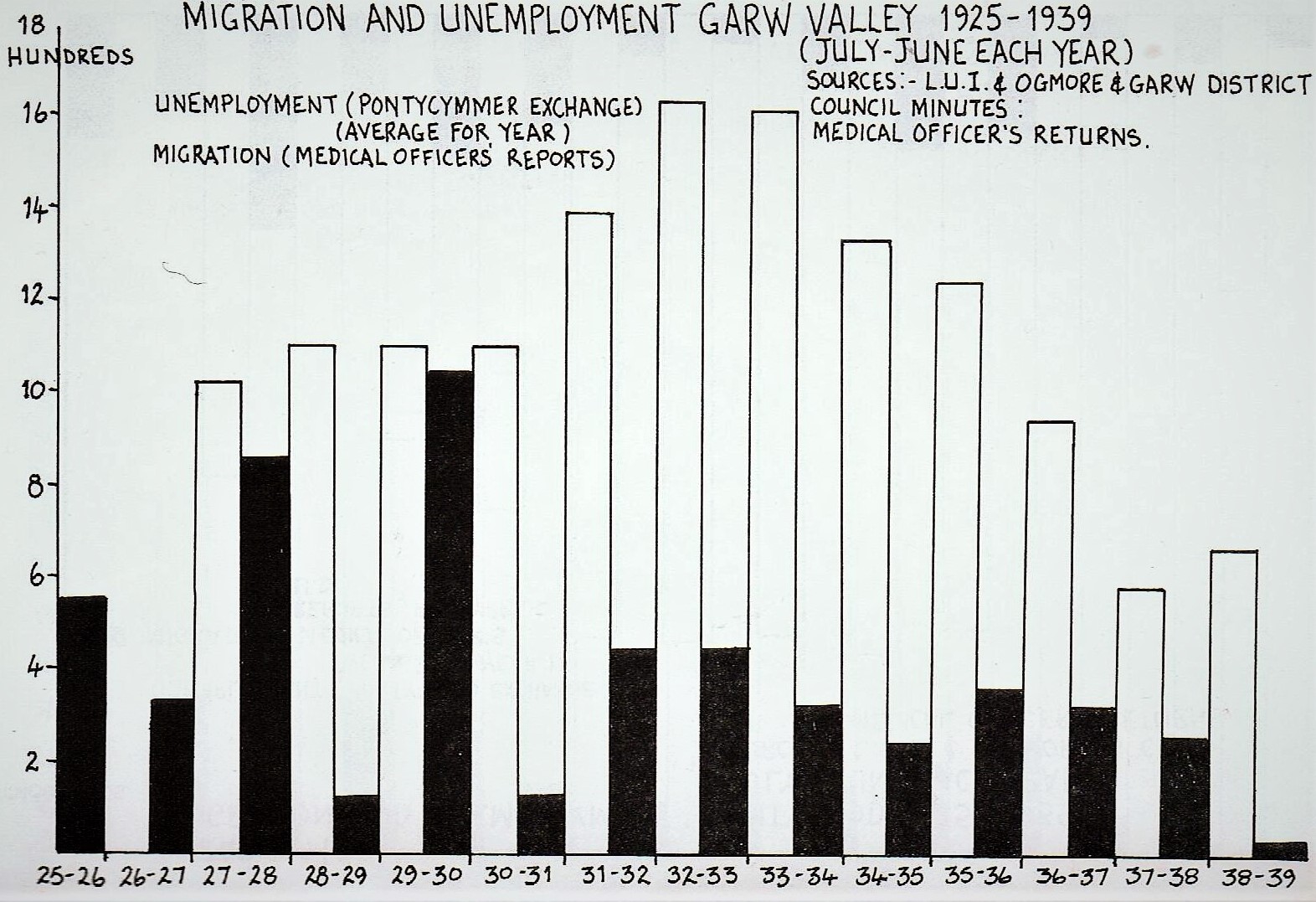

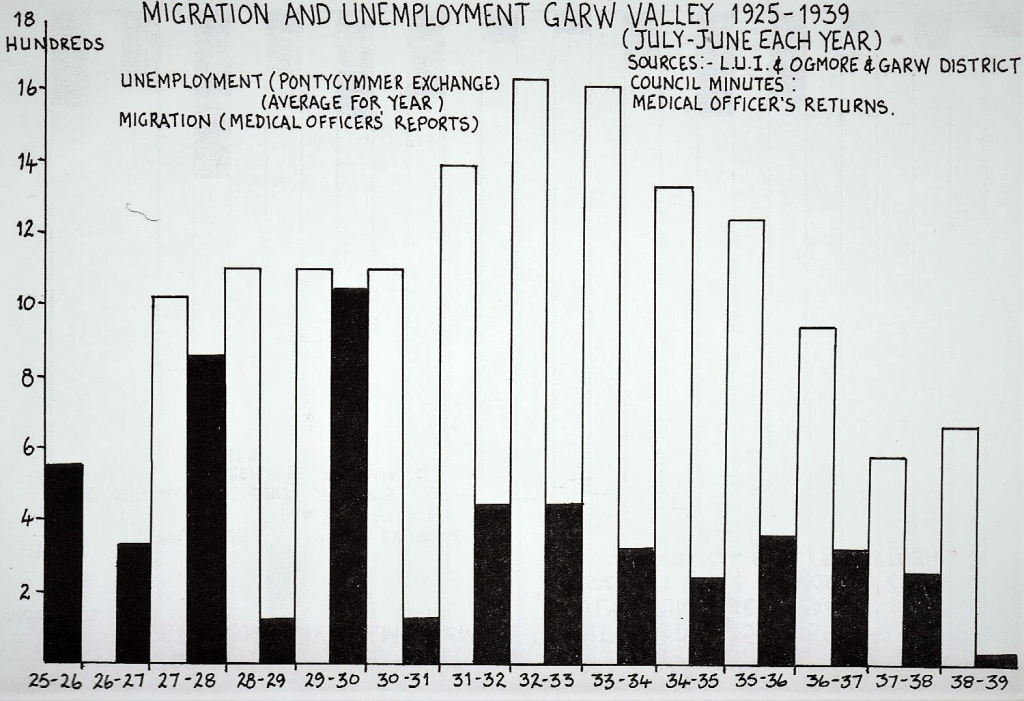

Besides their fixed outgoings for rent and rates, many people throughout the valleys also made regular contributions towards their own health care, continuing to do so in spite of the impact of the depression on their incomes. It may have been that they felt the conditions imposed on them by increasing impoverishment and dilapidating housing even more essential. In his report to the Nuffield College Reconstruction Survey in 1942, mentioned above, J. D. Evans found a widespread feeling that the existing National Health Insurance Scheme provided inadequate cover in times of sickness. Independent Medical Aid Societies and hospital contributory schemes continued to be popular throughout the coalfield. Nowhere was there better evidence of this than in the Garw Valley where there were more than 3,500 insured contributors to the local Medical Society, with a further 2,800 dependants standing to benefit from this.

This form of self-help was the valley’s means of survival during the Depression years. Due to being geographically hemmed in, the community felt the need to provide for itself a complete range of health, social and cultural services. This did not mean that it lacked a ‘wider outlook’ but rather that it used its home-grown institutions as a basis on which it could relate to the outside world on its own terms, and as a means by which it could interpret and respond to the gargantuan economic and social forces which had brought it into being and now threatened to crush it. The people of the Garw may have contained fewer members of ‘the old Welsh stock’, much eulogised by liberal nationalists, than the people of Merthyr and the other heads-of-the-valleys communities who could trace their attachments back through four or five generations, but they showed no less commitment to the abundant and vibrant institutions which had been created in the valley by the mid-1920s.

Turning the Screw Too Tight? – Resisting Transference:

Simultaneously, an intensive campaign began to encourage employers in prosperous areas to take on men and boys from depressed areas. Baldwin himself made a direct appeal for them to approach the nearest Labour Exchange, but the results of this were not as great as the Government had hoped, and Chamberlain admitted his disappointment to the South Wales Miners’ Federation (SWMF) delegation which met with both him and the Minister of Labour, Sir Arthur Steel-Maitland, in October 1928. The miners’ leaders were accompanied by seven Labour coalfield MPs. Morrel and Richards, President and General Secretary of ‘the Fed’, argued that the situation in South Wales was becoming ‘dangerous’ and this point caused some nervousness among the ministers and officials present who were sensitive to the possibility of a recurrence of the ‘disorder’ which had occurred during the 1926 Lock-out. In a memorandum on the meeting, one official wrote to the ministers that:

‘The issue is whether the screw may not have been turned too tight in the South Wales areas, as a result of our attempts… to secure the the administration of relief on sound lines and to induce local authorities their financial coat according to the available cloth… a bad winter would be a serious thing in such a such conditions of worklessness and depression as have so long prevailed in some parts of South Wales. If anything untoward should occur in these places in the winter, … there would be a risk of panic action minatory to the whole of our recent poor law policy.’

HLG 30/63: Deputation from the South Wales Miners’ Federation to the Ministers of Health and Labour, Minutes and Memoranda, 31 October 1928.

This official nervousness was further reflected by the reaction of James Evans when he heard of a proposed visit of the Prince of Wales to the coalfield in the New Year. He urged caution, and Arthur Lowry, later to head the Commission on Merthyr, was dispatched to South Wales to report on the conditions there which were recovering by the time the winter of 1928-29 came due to a recovery in the Coal trade. Both Steel-Maitland and Chamberlain echoed the view of James Evans that the provision of further relief on a long-term basis would result in further ‘demoralisation’. Steel-Maitland made this clear to the Cabinet:

‘… To leave them in their villages … involves steady demoralisation, an apalling waste of manpower and the continuance of a canker, the evil effects of which spread far beyond the locality … Relief works in the depressed areas have long exhausted their usefulness; indeed they are positively harmful in so far as they encourge men to remain where they cannot hope for continued employment.’

CAB 24/198: Industrial Transference Schemes: Report on work done and comments on objections to transference policy; CP 324, Memo by Sir Arthur Steel-Maitland, with appendices, 1 November 1928.

Some government ministers did, however, attempt to bring relief of a different kind to the depressed areas. Winston Churchill was responsible for major sections of the Local Government Act of 1929 which reformed the Poor Law and brought about de-rating and a system of block grants. He clearly saw this as a means of relieving industry in these areas and combating economic depression. In a speech on the Bill in the House of Commons, he argued that it was…

‘…much better to bring industry back to the necessitous areas than to disperse their population, at enormous expense and waste, as if you were removing people from a plague-stricken or malarious region.’

LAB 23/75: Special Areas of South Wales – Burden of local rates.

Clearly, this view was not shared by Chamberlain who saw the Bill as a means for the careful central control of local authorities, rather than as a means of equalising the effects of the low rateable values on these areas. When Lowry submitted his report to Chamberlain in February 1929, the Minister saw in them no cause to call for a change in central policy. Speaking on the report in Parliament later that month, he took up the same theme of the dangers of demoralisation that would result from further relief funding, though he was not as optimistic as the Minister of Labour regarding the length of time required for the policy of transference to achieve results. He estimated that seven years was needed, rather than the three Steel-Maitland had suggested.

There is no evidence to suggest that the Labour Government of 1929-31 tried to abandon the Transference policy. However, they did not consider that its continuance should exclude attempts to attract industries to the depressed areas or to develop public works schemes. However, the widespread nature of unemployment in these years, the lack of imagination and ineptitude of J. M. Thomas as Minister for Employment, the resistance of officials, the innate conservatism of Philip Snowden at the Exchequer and the general economic crises which beset this administration precluded the possibility of a radical response to the problem of mass unemployment.

Between 1931 and 1937 the National Government continued to uphold transference as the solitary cure for long-term unemployment in depressed areas. For most of this period, they also continued to enjoy the support of local authorities in operating the policy. A 1931 memorandum on the Distribution of Juvenile Employment reported that all fourteen of the Juvenile Employment Committees in Wales recommended transference as the only solution to local unemployment and urged the use of public funds to assist with the maintenance and travelling expenses of juveniles.

Serious Welsh opposition to the policy only became significant in May 1936, when The South Wales and Monmouthshire Council of Social Services (SWMCSS) held a special ‘Conference on Transference’ at the YMCA in Barry. The SWMCSS was founded in 1919 as part of the National Council of Social Service. As well as drawing representatives from the proliferating voluntary societies of the time, it also worked very closely with successive governments in the twenties and thirties. Nine Departments were represented, including the ministries of Health and Labour, the Home Office and the Board of Education. Up to this point, the Council had played a major role in the Government’s strategy, with a number of its leading members and workers being involved in both the social administration of the transference scheme at a regional level and the government-sponsored voluntary work in the valleys.

Most of the prominent figures in the Social Service movement across the region attended the Barry Conference. Church leaders and MPs also took part. Rev. T. Alban Davies argued that the ‘national conscience’ was being roused against the break-up of communities which represented the history and traditions of Wales and that unless the Social Service movement came out clearly in opposition to the scheme, its ameliorative involvement could be seen as evidence of its support for it. Aneurin Bevan, MP for Ebbw Vale since entering Parliament in 1929, also called for an end to the policy, and attacked the complacency of those who purported to be the leadership of the ‘Welsh Nation’:

‘… If the problem was still viewed as complacently as it had been, this would involve the breakdown of a social, institutional and communal life peculiar to Wales. The Welsh Nation had adopted a defeatist attitude towards the policy of transference as the main measure for relief of the Distressed Areas in South Wales, but objection should be taken as there was no economic case for continuing to establish industries in the London area rather than the Rhondda.’

LAB 23/102: Report of Conference on Transference, convened by the SWMCSS, 15-16 May 1936.

The reason for this complacency was made apparent by one speaker who replied to Bevan’s remarks by suggesting that East Monmouth had no Welsh Institutions or traditions likely to be damaged by large-scale transference, as most of its people were originally immigrants who had not been absorbed into local life. However, most of those present was that what was taking place was expatriation and not repatriation. Elfan Rees, who as Secretary to the SWMCSS was invited to speak to the third major Welsh conference of the year, developed this theme in his ‘Survey of Social Tendencies in Wales’ which he presented to the Welsh School of Social Service in Llandrindod Wells in August. The ‘School’ had been established by Lleufer Thomas in 1911, in a bid to ‘take back control’ of the valleys from the trades unions and socialists who were seen as ideological aliens, disruptive of the ‘Celtic Complex’. Appealing to the liberal nationalists in his audience, he pointed out that those leaving the coalfield were not the ‘rootless undesirables’ who had moved into it in the previous generation, but the young, the best and the Welsh:

‘… If transference was repatriation it might be a different story, but it is expatriation. It is the people with the roots who are going – the unwillingness to remain idle at home -the essential qualification of the transferee again, are the qualities that mark our own indigenous population. And, if this process of social despoilation goes on, the South Wales of tomorrow will be peopled with a race of poverty-stricken aliens saddled with public services they haven’t the money to maintain and social institutions they haven’t the wit to run. Our soul is being destroyed and the key to our history, literature, culture thrown to the four winds.’