The Growth of the Great Central European Empire:

Sigismund of Bohemia, pictured above, became Holy Roman Emperor in 1433, an event which marked the establishment of the great Central European Empire under Habsburg rule, through his daughter’s marriage, until 1918. As Emperor, he acted as an intermediary between Henry V of England and the King of France. From this time onward Anglo-Hungarian relations entered a new phase. The menace of Ottoman expansion loomed large over Europe and the English and Hungarian armies joined again in a common cause. Following Sigismund’s death in 1437, the Austrian-Bohemian-Hungarian alliance collapsed during the rule of his son-in-law. But in the southern borderlands of Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, a general emerged who stamped his own charismatic personality on the age more effectively than any of the crowned kings and princes of these countries. Although held to be a Transylvanian-Romanian, his family had solid Hungarian origins and he was regarded as Sigismund’s natural son. But it was his deeds which qualified him as the protector and Regent of St. Stephen’s crown lands. From a warrior of low rank, he rose to become the most eminent general of fifteenth-century Europe. At the end of his life, he owned two million hectares of landed estates, the income from which he spent almost exclusively on his campaigns against the Ottomans.

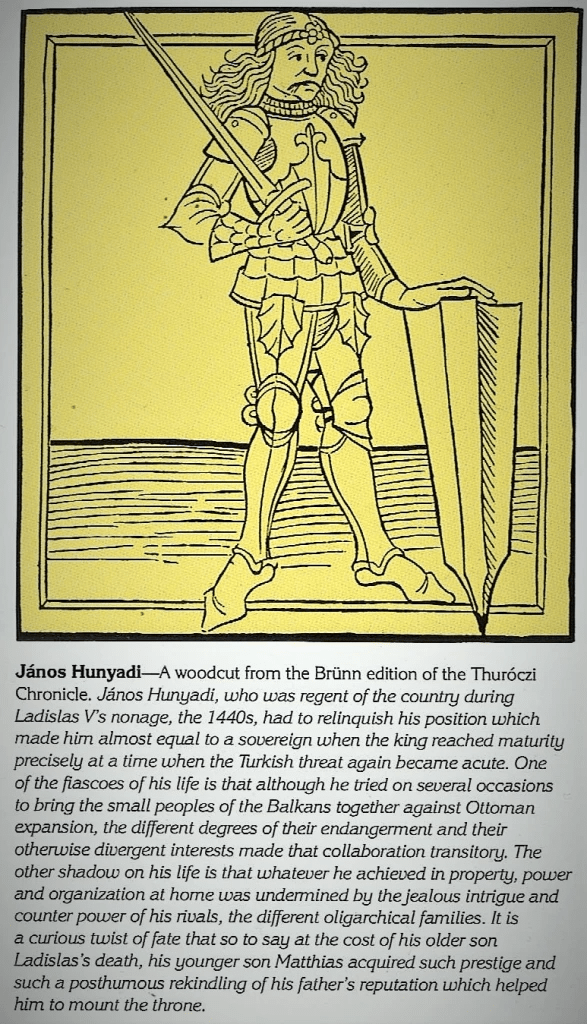

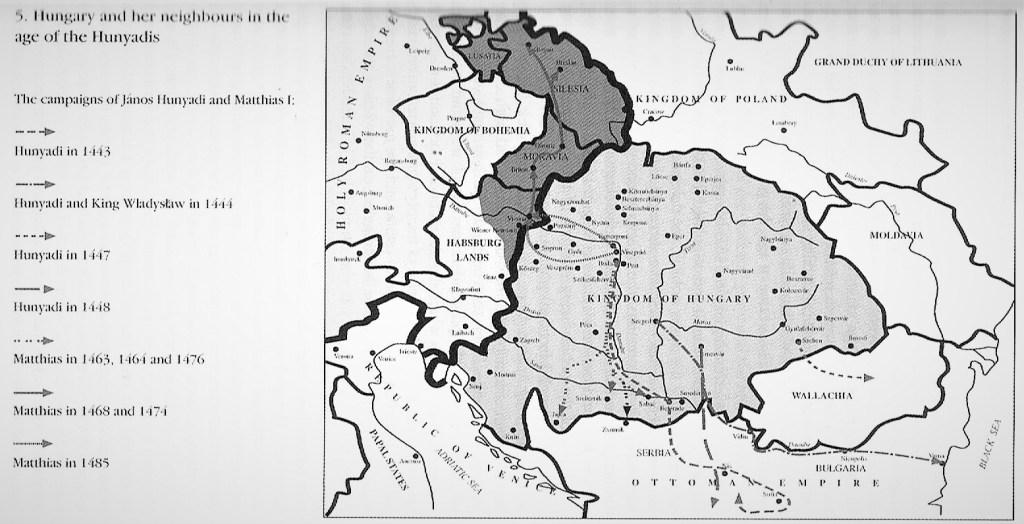

After the humiliating defeats suffered by the Hungarian-led knights, including some English Hospitallers, at Nicopolis in Bulgaria, and the 1444 defeat at the Battle of Varna (see picture above), János Hunyadi became Regent in 1446 and tried on several occasions to bring the small Balkan territories together to resist the Ottoman expansion. But despite further losses against the Turks, he gradually restored the integrity of the country and consolidated his authority among the nobility. As a result, even Frederick III acknowledged his governorship, which only came to an end in 1452 when the Austrian estates rebelled against Frederick while he was visiting Rome to get himself crowned Emperor. Hunyadi had to relinquish his position, which had made him almost equal to the King when Wladislas V came of age, which coincided with the revival of the Turkish threat. In 1456, three years after he captured Constantinople, Sultan Mohammed II led a formidable army of some hundred thousand men against Belgrade, the key fortress of Hungary’s southern defensive system.

The panic that had been caused by the fall of Constantinople gave rise to rather ineffective countermeasures both from within and outside Hungary. The Christian princes of Europe failed to respond to the call of the Pope for a Crusade. As Mehmet’s well-trained and well-equipped professional army set off to besiege Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) in early July, the defenders could only expect relief from the soldiers mobilised by Hunyadi from his estates and retinue, and insurrectionists from among the commoners of southern Hungary. Hunyadi’s army for the city’s relief was a mixture of three elements; his mercenaries, the insurgent nobles and the commoners, who responded to his call to arms despite recent rebellions against their landlords. They were recruited, in part, by an impassioned Franciscan friar of strict morals, Giovanni Capistrano who was Hunyadi’s right arm. Combined, these forces equalled less than half of those of the besiegers.

And yet, the ‘Crusader’ army gained a decisive victory in the battle, during which his guards rescued the wounded Sultan half-dead. When he had recovered, he decided to retreat., and although the opportunity for a counter-offensive was missed, this ‘triumph’ halted the Ottoman advance into Europe for several decades. Hunyadi’s immediate achievement was to secure the southern system of defence, the most important legacy of Sigismund: no Turkish attempt of similar dimensions took place until sixty-five years later. Even today, in cities, towns and villages throughout Central Europe, the pealing of bells at noon reminds people of the victory achieved on 22nd July 1456. Pope Callixtus proclaimed a Christian holiday and is said to have issued the decree for the pealing, but according to another version, he had already given instructions for bells to be rung to warn of the impending battle. In any event, the pealing of the bells at noon turned into a permanent event and certainly played an important role in the universal victory celebrations that took place throughout Christendom after the battle. Hunyadi’s exploits against the Turks were reported in contemporary records in English and subsequently influenced Elizabethan literature. Before he died, Hunyadi dispatched a special courier to England with news of his splendid victory at Nándorfehérvár in 1456. The good news was joyfully received in Canterbury, and the students celebrated the victory of the great Hungarian captain-general with the pealing of bells. We also know of three Hungarian knights who went to England during Edward IV’s reign (1461-83) to participate in tournaments.

However, barely a couple of weeks after the battle, the bells rang out again to mark the sudden death of János Hunyadi, struck down, not by the sword, but by the outbreak of plague in the encampment. Later that year, Capistrano also died from it. Hunyadi’s charisma and popular belief in his mission became strengthened his followers, thus paving his son’s path to the throne. But this path was not to be a smooth one; for the time being, Hunyadi’s death signalled an opportunity for his adversaries to weaken his ‘party’ and unleash another round of civil strife. Therefore, the loss of these two great leaders once more plunged the country into anarchy. Two influential families vied for power around the weak king and Cillei was appointed captain-general. He demanded that Hunyadi’s sons abandon the royal castles and revenues. László Hunyadi, the elder of the two, pretended to give in, but his men murdered Cillei as he marched into Nándorfehérvár. Most of Cillei’s supporters, outraged by this treachery, took sides with the king, who invested the new Hunyadi clan leader with the position of captain general, promising him impunity. In reality, however, he was only waiting for an opportunity to retaliate, and this came in March 1457 as both Hunyadi brothers were in Buda, where, in one of the bloodiest ‘episodes’ of this civil war of changing fortunes, Wladislas, aged seventeen but already a debauched, neurotic lout, had László arrested, court-martialled and brutally beheaded. Hunyadi’s widow and brother-in-law, Mihályi Silágyi responded rapidly by rising up in arms. The King then fled, first to Vienna and then to Prague, dragging with him the younger Hunyadi son, Mátyás (Matthias), as a hostage.

Matthias Hunyadi Corvinus – Hungary’s Renaissance Prince:

Ironically, by the end of the year, however, the plague had also disposed of Wladislas V, who died in Prague, not yet having reached his eighteenth birthday. His successor was the hostage himself, who quickly regained his freedom and acquired such a rekindling of his father’s reputation that he was able to advance his claim to the vacant throne. The mightiest members of the court party, Garai and Újláki soon realised that they had no chance to obtain the throne or rule the country as oligarchs, nor was there any foreign pretender who could put down the powerful Hunyadis and undertake the expensive extensions of the defences against the Ottomans at the same time. Thus they were compelled to make a compromise with the Szilágyis to arrange for the retention of their own influence in return for having Matthias, the only suitable candidate, elected King of Hungary. The lesser Hungarian nobility encamped in Pest and chose Matthias Hunyadi Corvinus (1458-1490) as their king, in a romantic fashion on the ice of the frozen Danube below the castle, though the discussion and debate about this had already happened within its walls and before that among the greater families.

Born in 1443, Matthias received a princely education from his tutors, such as János Vitéz, who introduced him not only to letters and languages but also to the rudiments of new humanist learning. He had already acquired a measure of expertise in statecraft, diplomacy and the art of war from his father and he also had the considerable prestige and economic, political and tary resources of the Hunyadi party at his disposal. If the de facto interregnum of 1444-1452 and the subsequent anarchy of Wladislas V’s reign amidst the Ottoman menace risked the disintegration of the Kingdom of Hungary, the acclamation of the son of the hero of Belgrade as king by the nobility on the frozen Danube near Pest on 24 January 1458, bode well to recover the country from that risk. Hungary had a national king once again, although the Hunyadi family acted as guardians for the fifteen-year-old until he gained his majority. Yet even before he came of age, the young Matthias had proved himself to be worthy of the family’s heraldic symbols, including the raven. The young monarch – who had been released by his Bohemian counterpart, George Podébrady, after the death of Wladislas in return for the promise of Matthias’ marriage to his daughter, Catherine – set to restoring order and central authority with great vigour. Relying mainly on the advice of his tutor, Vitéz, who had become his chancellor too, he thwarted Szilágyi’s hopes of becoming regent and replaced the barons with his own noble supporters as heads of the central law courts, the treasury and the newly-established court tribunal which administered the royal estates. The laws of the diet of June 1458 also benefited the nobility.

The disappointed barons, led by Garai and Újláki, invited and elected emperor Frederick III as king, and he attacked to make good his claim by attacking Hungary in the spring of 1459. Demonstrating skilful diplomacy, however, Matthias divided his enemies and Frederick then suffered a setback when the protracted peace talks resulted in the compromise treaty of 1463. In return for eighty thousand florins, the Holy Crown was surrendered to Matthias, who retained the title of King of Hungary, but Frederick and his successors were entitled to inherit the should Matthias die heirless. The treaty thus became the basis for the later Habsburg succession in Hungary. For the time being, however, it enabled Matthias to be crowned in 1464 and secured his place on the throne for the rest of his reign. Matthias also displayed an indulgent attitude towards the aristocracy; despite a rebellion and a conspiracy in which they were deeply implicated, he did not have any of them executed. But whereas early in his reign, Matthias enlisted the support of the nobility against the barons, later he often played the barons against the nobles or one baronial faction against another, while continually extending his own authority and reducing the circle of those on whom he depended. This is shown, among other things, by decreasing the frequency of new appointments.

Matthias has often been credited with centralising the country’s administration and even with laying the foundations of an absolute monarchy. It is tempting to draw parallels between him and some of the near-contemporary Western European monarchs who consolidated their realms after turbulent times through centralising measures, like Louis XI of France and Henry VII of England. It is also true that, especially in the latter half of his reign, his new style of governing with the pretension that he had ‘absolute power’ and was ‘unbound by the law’, made him highly unpopular and earned him denunciations as a tyrant among his most powerful subjects. However, Matthias’s centralisation undoubtedly arose out of the personal abilities and aspirations of a singularly gifted ruler, rather than from the specific conditions of late fifteenth-century Hungary. The royal council, far from becoming a group of officials trained in the law, remained the same feudal body it had been for centuries. It was in the administration of justice that professionalisation progressed most. The lesser nobles and commoners, a few of them trained at universities, but most of them only through practising the customary and statute law of the realm in everyday business, raised to the central courts after an apprenticeship in the local administration or in the lower courts, constituted the first significant stratum of the secular intelligentsia in Hungary.

Towards the end of the reign, important steps were taken towards the standardisation of the law codes across the country. The comprehensive statute book of 1486, for instance, not only expanded the authority of the palatine as well as the counties but also clarified procedural law. As a result of his judicial reforms, a rudimentary sense of the rule of law and security under the law emerged; for his personal efforts to suppress corruption and overbearing local potentates, the king was rewarded with the byname ‘Matthias the Just’ and became a popular, romantic hero of folk anecdote travelling incognito among his subjects in order to detect and punish evildoers He was…

…’the Just One, who, walking in the land in disguise, condemned fraudulent judges, shamed the greedy rich, and succoured the poor; he made love to full-blooded shepherdesses and ingenious maidens’.

István Lázár (1992), p. 54.

However, these judicial changes were second in significance to the fiscal and military reforms of Matthias’s reign, which in turn served his ambitious foreign policy. On his accession, the revenues of the crown were a rather miserable 250,000 florins per year, hardly enough to cover even the bare necessities of the defence of the country. To remedy this situation, Matthias embarked on a far-reaching reform of financial administration. He levied an ‘extraordinary’ subsidy (usually one florin per porta) over forty times during the thirty-three years of his reign and had it collected with increasing efficiency after he had consolidated his power. Exemptions from the ordinary taxes (e.g. the salt monopoly and the custom) were abolished in 1467, and they were magisterially administered by János Emuszt, a Jewish merchant who had converted to Christianity and a brilliant financial expert who later became Lord Chief Treasurer. The treasury officials were often men of humble origins and therefore owed their positions solely to the king and were therefore scrupulously loyal to the monarch. As a result of these reforms, Matthias more than doubled the revenues of the crown, and in years when the irregular subsidy was applied, if the income from the provinces conquered by him in the second half of his reign were also added, the amount might approach one million florins.

However, some of the historiographical comparisons between Matthias’s fiscal achievement and the incomes of Western countries, France or England, for instance, are based on slightly earlier data from the latter, in which revenues also doubled in the second half of the fifteenth century. Most importantly, the revenue of the Ottoman Empire in 1475 amounted to 1,800,000 florins; at least two, but even three times as much as that of Hungary and far more than any European kingdom at that time. In light of this enormous disparity, it is understandable that nearly all the surplus raised by Matthias was immediately spent on his army. In other words, while he filled out the treasury, he also left it empty at the end of his reign and burdened the country’s economy excessively. While he continued to rely on the royal and baronial banderia, the militia introduced by Sigismund, Matthias was also able to maintain a mercenary army, which he started to build up by hiring ex-Hussites pacified in northern Hungary in 1462. The multi-ethnic ‘Black Army’ consisted of heavy cavalry and Hussite-type war wagons and artillery, and, combined with the banderia and the light cavalry and infantry from the counties and banates, could be successfully employed to apply traditional Hungarian hit-and-run tactics.

Nevertheless, Corvinus maintained a largely defensive attitude against the Ottomans, not trying to push them back as his father had done. Having pillaged Western Serbia, Mehmed II took Jajce, the most important castle in Bosnia after a long siege and they conquered the territory by the end of 1463. But Matthias was successful in taking back northern Bosnia and three Hungarian banates were set up so that the territory was effectively divided between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. From then onwards Corvinus’ main attention was directed towards the West. The treaties of 1463 with Venice and Frederick III put an end to Matthias’s international isolation. With his standing army, he hoped to gain the crown of Bohemia and become Holy Roman Emperor.

Bohemia remained divided as a result of the Hussite troubles under its Hussite ruler, George of Podébrady, who had been excommunicated and proclaimed a usurper by the Pope in 1466. George’s daughter, Catherine, Matthias’s wife, had died in 1464 and Matthias severed his ties with his former father-in-law. In 1468 obtained Papal support to conduct a crusade against him. This led to the partition of the Bohemian kingdom in which Corvinus obtained Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia as well as the title ‘King of Bohemia’, which he was elected to in May 1469 by the Czech Catholic barons. But he did not gain its territory. He continued to be opposed by the Habsburg emperor, Frederick III (1440-93), the German electors and the Polish Jagiellos. Prince Wladyslaw, son of Casimir IV of Poland, accepted the Bohemian crown offered to him according to the wishes of Podébrady before his death in 1471.

Meanwhile, Matthias faced difficulties at home. Having quelled a revolt of the Transylvanian estates caused by the fiscal measures of 1467, he came under severe criticism from his former confidants János Vitéz and his nephew, the humanist poet and Bishop of Pécs, Janus Pannonius, claiming that the king had neglected Ottoman front and wasted the country’s resources on futile wars in the north. They were also concerned about Matthias’s pretensions to ‘arbitrary rule’ and they plotted to replace him with Casimir, the youngest of the Jagiello princes, but by the time the latter invaded Hungary in 1471, Matthias had stifled the criticisms by returning from Bohemia and appearing among his barons and nobles at the diet. In 1474, the leaders of the Austrian-Czech-Polish coalition missed a golden opportunity to break the ambition of the Hungarian king, surrounded by far superior forces in the Silesian city of Breslau (Wroclaw). In the subsequent Peace of Olmütz in 1478, Matthias once more gained Moravia, Lusatia and Silesia, while Wladyslaw retained only Bohemia. The treaty settled the affairs of the region on a lasting basis.

For most of the rest of Matthias’s reign, there were only minor skirmishes and occasional Turkish raids, such as the one culminating in the Battle of Kenyérmző in southern Transylvania in 1479, in which the Turks were beaten by the legendary commander, Pál Kinizsi. The reorientation of Hungarian foreign policy by Matthias has been an object of controversy among historians. As we have seen, even in his own lifetime he was criticised for neglecting the Turkish threat for the sake of his quest for personal glory in the West. But some historians have suggested that because he received practically no external help against the Turks, he sought to offset the massive superiority of the Ottoman Empire in terms of territory and manpower by uniting the resources of East-Central Europe, where the tradition had already been established of forging confederations of regional states through personal unions. As the archetypal founder of a dynasty, power-hungry as he certainly was, he was indignant at being considered an upstart among the more established dynasties of the region. The success of arms could earn what legitimacy denied him. To some extent, this was also true of his lavish patronage of the arts and learning.

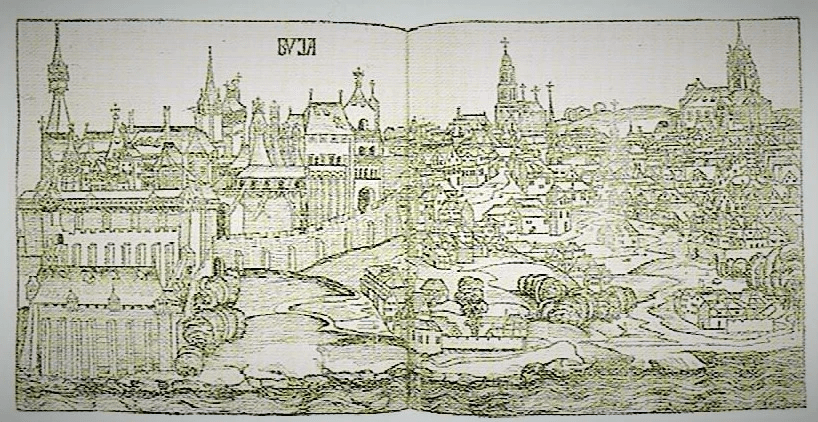

Matthias’s Renaissance court, whether held at Buda Castle or the palace at Visegrád, became known for its richness and soaring spirit. Many leading Humanists attended the court, and some even settled there. They regarded Matthias as one of the most patrons of the period, alongside the Sforzas of Milan, Federico da Montifeltro of Urbino and even Lorenzo de’ Medici of Florence. Enjoying luxury and culture equally, Matthias was a passionate book collector and customer, and among his purchases were codices, which he also commissioned. His library, the Biblioteca Corviniana, developed into the best collection in Europe, the first among many newly-founded libraries. The name derives from the byname first assigned to Matthias by Italian humanists. It was the name of an ancient Roman family, often associated with the raven (Lat. ‘Corvus’) in the Hunyadi coat-of-arms, but also possibly deriving with the village on the lower Danube, Corvino vico referred to by Bonfini as the home of the Hunyadis.

Towards the end of his life, his library collection reached a thousand titles and was ‘declared protected’, though it was depleted in the Jagiello period that followed. During their occupation of Buda, the Turks guarded what remained for a time, then transferred part of it to Constantinople. Today, about 170 ‘Corvinas’ are known to exist worldwide, only fifty of which are found in Hungary. For the grandson of an immigrant knight from Wallachia, his own erudition – he spoke several languages and not only collected but also read books – and the nearly one hundred thousand florins he spent on artistic patronage were excellent propaganda.

In the early 1480s, Matthias continued the campaign begun by his father against the Turks, who were once more seriously threatening at that time. But he also wished to protect his rear from the West either through alliances or force, by competing for the thrones of both Bohemia and Austria, to found a strong and powerful Danubian empire. Matthias’s marriage in 1476 to Princess Beatrice, daughter of King Ferdinand I of Naples had provided him with influential new allies in Italy. His ultimate aim was the imperial throne and in 1482 he declared war. In the first half of 1485, he captured Vienna and then two years later Wiener Neustadt when he also celebrated his taking complete possession of Lower Austria with this victory by holding a magnificent review of his troops. During these years, he moved about time and time again, holding court in Vienna and almost converting it into a second capital. By 1487, with his forces far superior to those of the emperor, Corvinus occupied most of Lower Austria and Styria, transferring his capital to Vienna and assuming the title Duke of Austria. Although the German electors chose Frederick’s son Maximilian as King of Rome, heir to the imperial throne, Matthias had succeeded in securing a sizeable empire of his own.

At the muster of 1487 at Weiner Neustadt, it was estimated that Matthias’s standing army numbered twenty thousand horsemen and eight thousand foot soldiers, with nine thousand war wagons, an impressive figure by the European standards of the time. There were another eight thousand soldiers permanently garrisoned in the fortresses of the superbly organised southern line of defence. Matthias was attempting to secure the succession to the throne for his bastard son, John Corvin, a Viennese commoner. His second wife, Beatrice of Naples, the queen, opposed him in this. In the end, he failed to achieve both of these objectives. He was still struggling to reach the second when he died suddenly and mysteriously in Vienna on 6th April 1490, perhaps by poisoning. His body was transported down the Danube to Buda and was finally interred in Székesfehérvár. Matthias conducted most of his campaigns not against the Turks in the Balkans, but in the north and west, and in particular against the proud bastion of Vienna (which, as a poet sang centuries later) ‘groaned under the onslaught of Matthias’s ferocious army.’ But Matthias lost what he most wanted to achieve, the power of a crescent alignment against Ottoman power. Nevertheless, ‘posterity’ mourned him and elevated him to the level of a folk hero. ‘Dead is Matthias, lost is justice’ is how the sixteenth-century tradition had the common man comment on his passing. ‘Dead is Matthias, books will be cheaper in Europe’ is reputedly how Lorenzo de’ Medici greeted the news of the death of Hungary’s Renaissance prince.

The Ascendancy of the West & the Habsburgs:

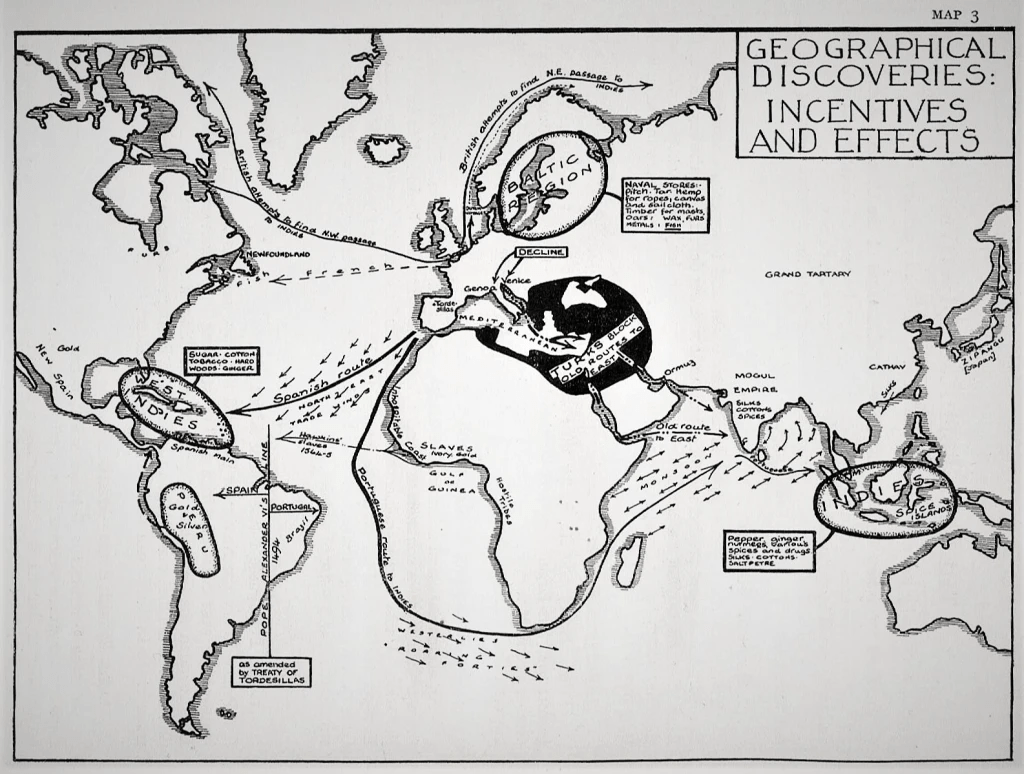

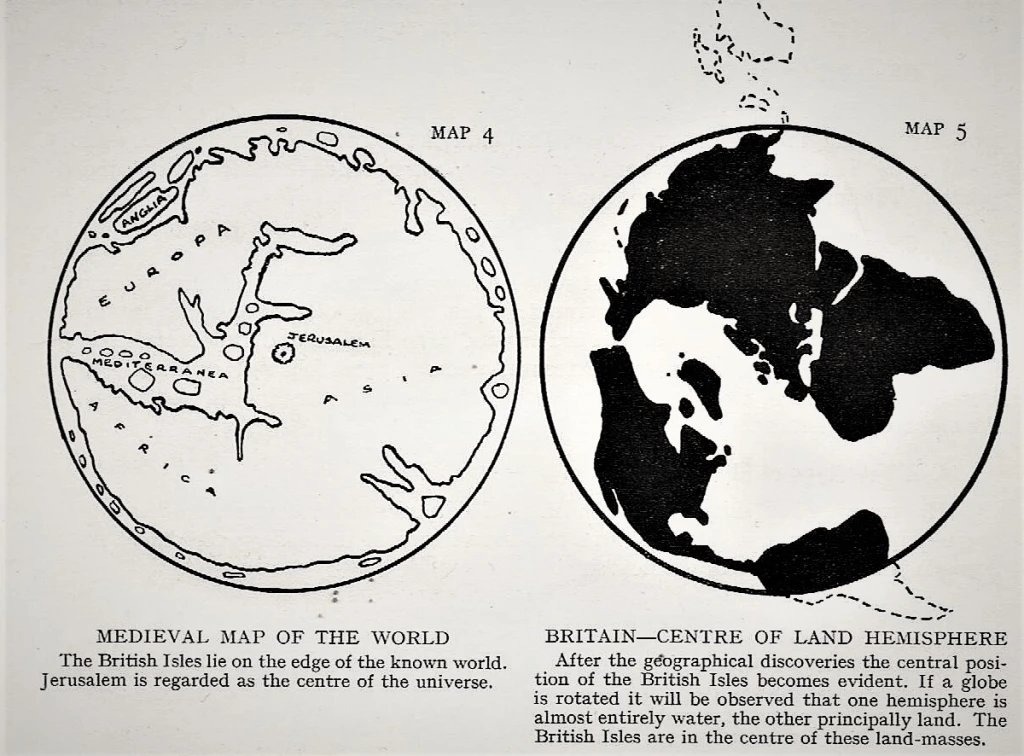

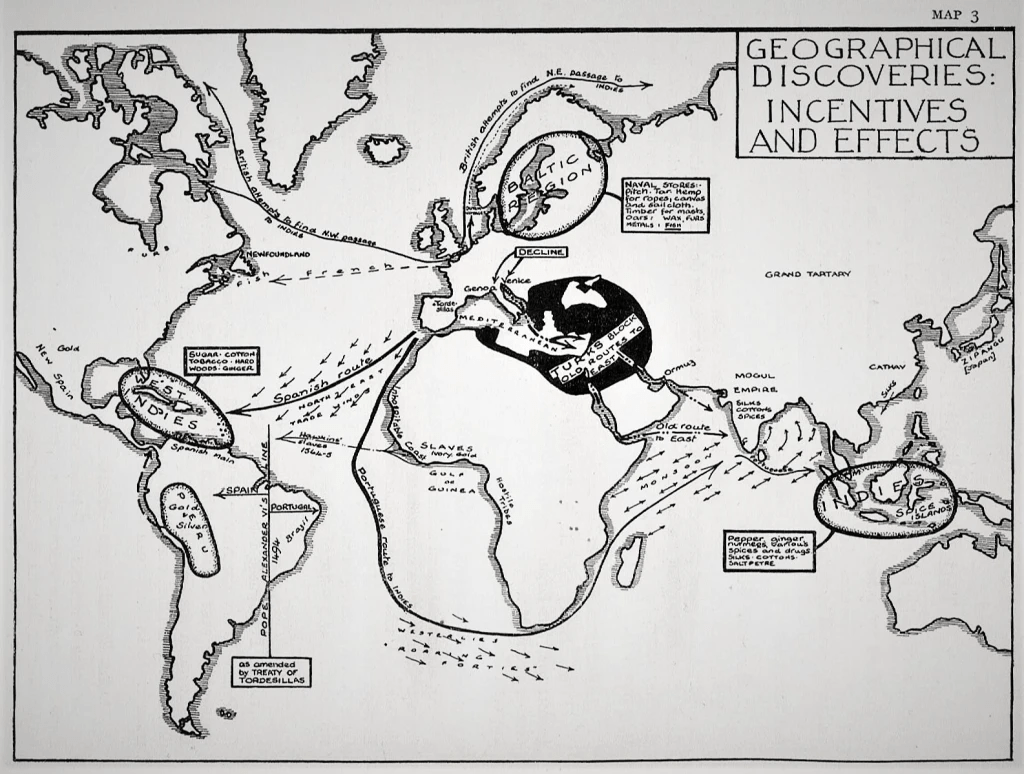

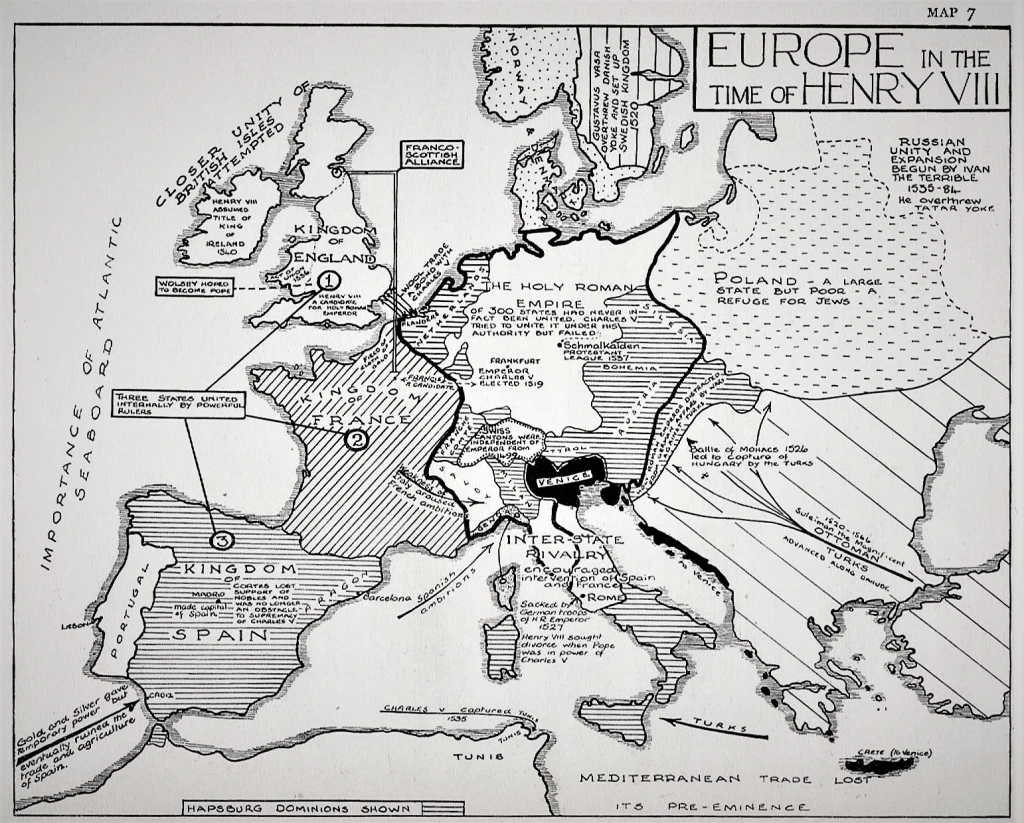

With hindsight, the near coincidence of Matthias’s death with the discovery of the Americas could be seen as symbolic of a change in Hungary’s fortunes and those of Central-Eastern Europe as a whole. The period is generally regarded as the beginning of the early modern era when the progress of commerce, finance and industry, of armies and navies, and of centralised and systematic administrations gradually raised Western Europe to the global ascendancy it enjoyed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, marked the beginning of a trend towards relative political weakness and relative social and economic decline in Central Europe. Within a few decades, the estates dismantled the achievements of centralised monarchy, and although the Jagiello brothers seemed to realise Matthias’s dream of a Central European ’empire’ by dividing the region’s thrones between them, their administrations and landed estates came increasingly under the control of the different baronial and noble factions.

The nobility’s power in the region was reinforced by the new European division of labour arising from the geographical discoveries. As the resources of the New World were channelled into Western Europe, it soon became established as the new centre of commerce, industry and finance on the old continent. At the same time, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe were confirmed as suppliers of raw materials and agricultural produce. The ‘price revolution’ resulting from the influx of gold and silver from overseas was primarily a steady and marked increase in the price of foodstuffs.

Among the succession of pretenders to the Hungarian throne who thronged around it eagerly, and made lavish promises, mustering armies to support their claims, were a group of oligarchs, who had gained new power even before the death of Matthias. They sent John Corvin packing, considering the Bohemian king, Wladislas of the House of Jagello, to be more suitable, by which they meant more controllable by them. He docilely disbanded the main support of the throne, the Black Army and with it centralised power. The resulting precariousness of the law, the oppression of the serfs, and feudal anarchy weighed heavily on the country. During the reigns of Wladyslaw, John Albert and their successors in Bohemia, Hungary and Poland with their diets pouring out edicts that tended to bind the peasants to the soil, strengthen the nobility’s legal powers over them and revive the duty of forced labour (corvée). These measures amounted to the imposition of a ‘second serfdom’ as the transformation of the peasant obligations into cash and of the peasants themselves into freeholders was overturned. They were relegated to a position more similar to that of Russian serfs rather than the independent yeoman farmers emerging in the West. The suppression of the resulting peasant unrest further increased the power of the nobility and further undermined centralised authority. Among about three and a half million subjects of the Hungarian crown, one in twenty-five were noblemen, contrasted with France, where the figure was only one in ten. The collapse of Matthias’s state and the reorientation of the world economy consolidated the traditional structures of Hungarian society, reversing trends that might have brought it closer to its Western counterparts.

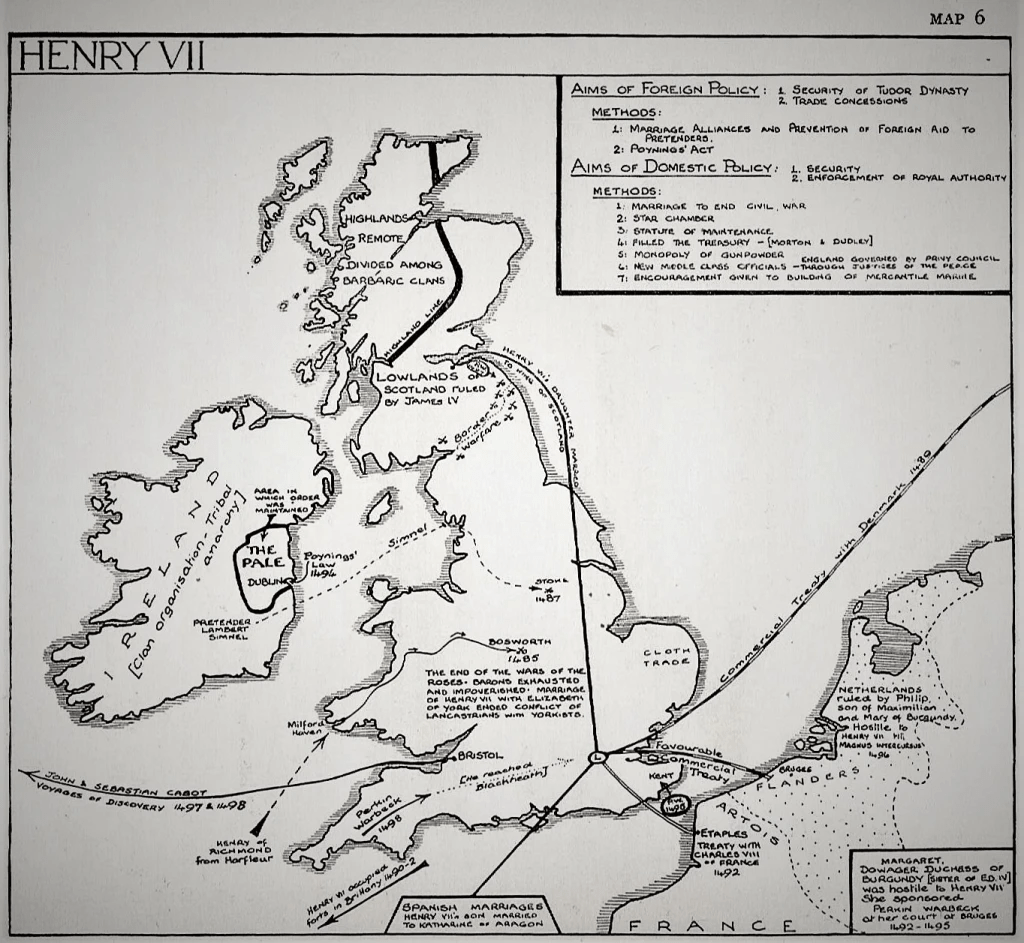

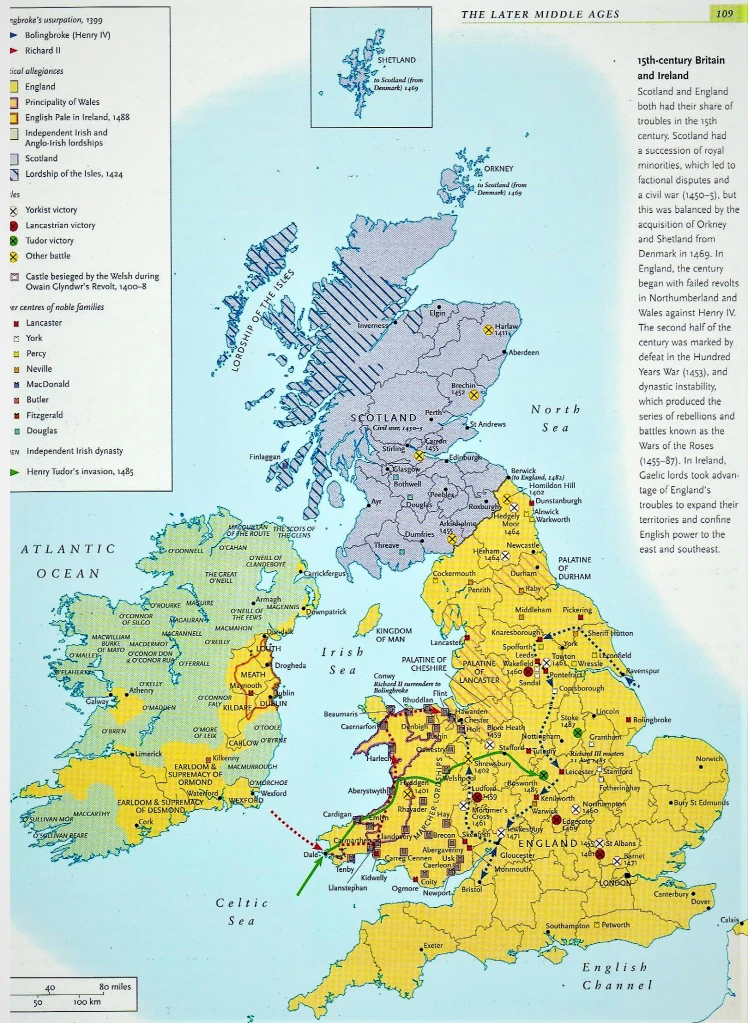

In England meanwhile, the anarchy of the thirty years of the Wars of the Roses came to an end in 1485, with the Battle of Bosworth Field (Leicestershire), at which the issue of the succession was decided, when the gold crown which had, supposedly, fallen from the head of Richard III, was placed on that of Henry Tudor. As Henry VII, he became the new Welsh master of England’s destiny. This status was confirmed with the final rout of Yorkist forces at Stoke Field in 1487. Two years later, in 1489, ambassadors and diplomats from all parts of Europe were in England and, as one of King Matthias’ biographers tells us, the King of Hungary was among those who sent envoys to Henry’s Court.

Henry VII was supposed to have made peace with the House of York when he married Elizabeth of York, thus enabling the red and white roses to bloom side by side. At least, this was the Tudor mythology, alongside the naming of Henry’s eldest son and heir as Arthur, symbolising the rising again of the Red Dragon of the ancient King of the Britons. But Henry knew he was far from secure as King of England, and it is only with hindsight that 1485 is seen as the key date in the transition from Medieval combat to Early Modern statesmanship. Henry had won the crown by force, not legitimate inheritance, just as had his Lancastrian ancestors. At the time, and at any suitable moment in it, Henry knew that the House of York might again seize the throne they still laid claim to. No regular order of succession had been established, and it was might rather than right which would keep the Tudors in contention to establish a dynasty. During the first years of his reign, he was disturbed by two insurrections led by two ‘pretenders’, one headed by the Earl of Lincoln, with Lambert Simnel as its figurehead, and the other headed by Perkin Warbeck.

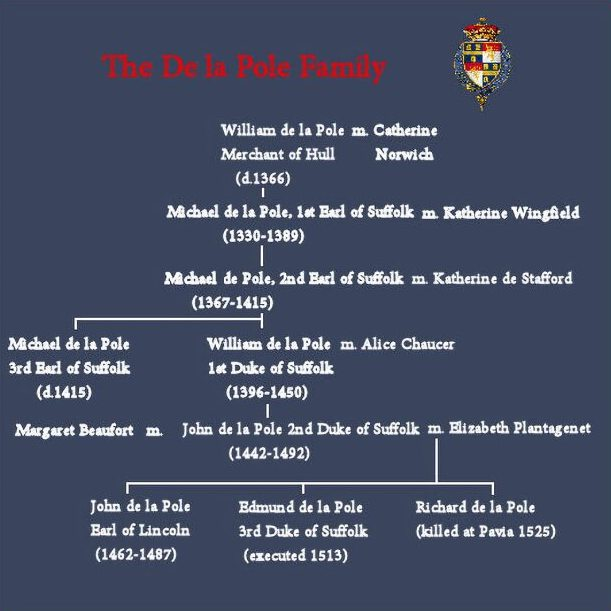

Following the Wars of the Roses and the final defeat of the Yorkist cause at the Battle of Stoke Field in 1487, the last of the Plantagenets claimants to the throne, Richard de la Pole, sought refuge at the Court of Wladislaw II of Hungary (1490-1516). Sometime between 1506 and 1508, the last hope of the Yorkists spent some time in Buda. This pretender to the throne of England was apparently related to Anna, Queen of Hungary and Wladislaw’s second wife. Richard Plantagenet’s story is but one tragic chapter in the final denouement of the dynasty. His grandfather, William de la Pole, had been imprisoned in the Tower of London and then exiled by Henry VI. He was murdered on his ship in the Channel and his body was washed ashore near Dover in 1450. His wife, Alice, brought his body home. No doubt embittered by his treatment, she continued to consolidate the family’s estates, perhaps fatefully, by abandoning their Lancastrian connections and building up their Yorkist ones. John de la Pole was the grandson of William and Alice, and the eldest son of the first Duke of Suffolk, the elder John de la Pole (d. 1491), and Elizabeth Plantagenet of York. He was therefore in direct line to the throne. Elizabeth’s brother was Edward IV, and it was he who made her son John, Earl of Lincoln. Edward had married Elizabeth Woodville, whose two sons, Edward V and Richard Duke of York were imprisoned in the Tower of London when Richard of Gloucester had the Woodville marriage declared illegal, thus enabling him to usurp the young king whose ’protector’ he had been.

When Richard III lost his only son, the Earl of Lincoln became ’de facto’ the next Yorkist in line to the throne. Although never clearly declaring him as his successor, Richard gave him the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall, titles reserved for the heir. Lincoln fought for Richard at Bosworth Field, surviving the battle. Following the ’Tudor Takeover’, both Lincoln and his father, Suffolk, at first made peace with Henry VII, who visited them at their manor in Oxfordshire to reassure them of his goodwill towards the family. However, Lincoln was then introduced to Lambert Simnel, and a plot began to form by which he hoped to secure the throne for the Yorkists, and perhaps also for himself. Simnel bore a striking resemblance to the young Edward, Earl of Warwick. Edward was born (in 1475) as Edward Plantagenet, to George, Duke of Clarence and Lady Isabel Neville, elder daughter of the 16th Earl of Warwick. Richard Neville, ’The Kingmaker’, who had eventually been killed in battle in 1471, had no sons, so Richard III had Neville’s grandson created Earl of Warwick in 1478 and knighted at York in 1483. On seizing the Crown on the battlefield at Bosworth in 1485, Henry had re-imprisoned the boy in the Tower, where he had already spent much of his young life, hence the possibility of impersonation.

Lambert Simnel was the son of an Oxford carpenter. Henry’s enemies had proclaimed him as Edward Plantagenet, claiming that he had escaped from the Tower. The Yorkists rallied around him, and when they felt strong enough, they recruited an army to support his claim. However, early in 1487, when he first heard of the plot, all Henry VII had to do was produce the real Earl of Warwick. As the Plantagenet heir, Warwick would have possessed a stronger claim to the throne than both Henry and Lincoln and was only prevented from acceding to the throne by the act of attainder by which Richard of York had usurped it. With Richard deposed, Lincoln knew that Parliament could easily be persuaded to change its mind and reinstate the boy’s claim, or Henry would be forced to disclose that Edward V and Richard Duke of York were no longer alive. Lincoln may have known this himself, especially if they had died on the orders of Richard III since he had been Richard’s heir. To scotch the rumours of Warwick’s escape from the Tower, put about by Lincoln’s supporters, Henry had the real young Earl parade through the streets of London. But Lincoln had already fled before Henry could force him to recognise the real Earl or reveal his treachery.

Some historians have suggested that this shows that Lincoln was intending to take the throne for himself. He raised an army of German mercenaries in Burgundy, with the help of Margaret of Burgundy, the sister of Edward IV, and landed in Ireland. Margaret then declared Simnel to be her nephew and Lincoln told of how he had personally rescued the boy from the Tower. He was proclaimed Edward VI and crowned in Dublin by its Archbishop, at the end of May 1487. Having acquired Irish troops, led by Sir Thomas Fitzgerald, Lincoln then landed in Lancashire on 4th June and marched his troops to York, covering two hundred miles in five days. However, the city, normally a Yorkist stronghold, refused to yield to him, perhaps because they did not wish to be governed by a king, even a Yorkist, who depended on German and Irish mercenaries. Gathering troops on the way from Coventry to Nottingham, the Tudor king met Lincoln’s forces on their way to Newark. Although the Germans under the command of Martin Schwartz fought with great valour at the Battle of Stoke Field on 16th June 1487, Fitzgerald, Lincoln and Schwartz himself were all killed, together with over four thousand of their men.

Poles, Popes & Jagiellos:

When the Tudors came to the English throne, initially they continued to support England’s Central European allies with money, though not with arms or armies, against the Turks. Nonetheless, Henry VII did send a money gift to Wladislas II to help him in his struggle against the Ottomans. Wladislas returned the gift with a golden cup, which was left by the envoy, Geoffrey Blythe, to his Cambridge College (King’s) in 1502. This may have been a demonstration by the Hungarian King that he had asked for soldiers rather than money. Hungary was a relatively wealthy country at that time, or at least its leadership was. Tamás Bakócz, Bishop of Győr and Eger, and then Archbishop of Esztergom, was a true Renaissance figure. He had first been Matthias’ secretary and became Wladislas’s all-powerful deputy. Bakócz proceeded to Rome to advance his bid for the papacy with wagons fully laden with gold; he waited patiently for the death of Julianus II, a great patron of the Arts in general and Michelangelo in particular. At the conclave to appoint the new pope, Bakócz was narrowly defeated by Giovanni De’Medici, who then mounted the papal throne as Leo X. To compensate Bakócz and to get rid of him from the Vatican, the pope granted him the right to announce a new Crusade against the Turks.

On the surface, most of Wladislas’s reign was one of tranquillity, both at home and on the frontiers. The confusion that accompanied the succession raised the appetite of the Ottomans, who made unsuccessful attempts to capture important fortresses year after year until a peace treaty was concluded in 1495. This was renewed several times, with a short interval in 1501 when Wladislas joined the coalition of the Pope and Venice; however, his main objective in doing so was to obtain the lucrative subsidy offered by his allies, and he refrained from major battles or sieges. Only the Bosnian Banate of Srebrenik was lost to the Turks, but the balance was still more unfavourable to the Hungarians since the skirmishes and raids that continued without a formal war still devastated the lands and fortresses erected by Matthias, and this cut their supply lines. It was increasingly difficult to defy Ottoman pressure. Meanwhile, the only significant conflict between Hungary and a Christian power was Maximilian’s declaration of war in response to the Hungarian estates that no foreigner ought to be elected king of Hungary, should Wladislas die heirless. The issue was settled by the inheritance treaty of 1506. Maximilian’s grandson Ferdinand was to marry Wladislas’s daughter, and any son born to them would marry Ferdinand’s sister Mary. When the treaty was disclosed, the Hungarian estates compelled the king to recommence the war with the emperor, but as Wladislas’s son Louis was born a few months later, this declaration seemed premature.

At the centre in Hungary, recruitment commenced and the army grew, predominantly with peasants. Swords were scarce but straightened scythes and flails were abundant. While Bakócz aimed at the papacy, the King hoped for a small military success to placate the nobility. But the peasants were driven by resentment against their lords and bitterness about their conditions, not by faith or zeal against the Turks. It was not only the landless, impoverished and defenceless serfs who were bitter but also the more united, well-to-do peasants of the Alföld (the Great Plain) who were held down by nobles who saw them as upstart competitors, no longer content with the production of food and goods, but also engaged in exporting surpluses. The leader of the Christian armies was neither the King nor the Archbishop but a member of the lesser nobility in Transylvania, a Székely lieutenant, György Dózsa. The most zealous recruiters and administrators of his armies were the Franciscan monks who belonged to an order that followed the strictest regulations, the Observants, most of whom were of peasant ‘stock’. In their view, the laws of God did not support the unequal distribution of property. In 1514, the armies mobilised under the Sign of the Cross, but took arms not against ‘the heathens’ but against the nobles, leading to a Peasants’ Revolt which the voivode of Transylvania, John Szapolyai, already a powerful noble in the time of Matthias, brutally suppressed.

Despite the fact that the last direct, surviving legitimate male Plantagenet claimant to the throne, the Earl of Warwick died on the scaffold in 1499, the de la Poles did not give up their claim to the throne. Lincoln had two younger brothers, Edmund and Richard. Both laid claim to the throne and both had a strong following at home and could count on support from abroad. Suffolk died and was succeeded by his second son Edmund, in 1491. He was demoted to the rank of earl by Henry VII and fled abroad in 1501, prompting the seizure of his estates. He sought to enforce what he saw as his rightful claim with the aid of Emperor Maximilian, making his way to the Tyrol to visit the latter, who at first showed great readiness to support him. Later on, however, Maximilian became reconciled with Henry and concluded a treaty with the Tudor King in which he undertook not to support the pretender in exchange for ten thousand pounds. Meanwhile, Edmund had gone to Aachen, where he was followed by his brother Richard. Financial troubles weighed heavily on the two brothers, despite the considerable sum allowed them by Maximillian to settle their debts. Formally attainted in 1504, after various adventures Edmund was captured by Henry in 1506 and was sent to the Tower. He was not immediately executed, however, for Henry had given pledges to the King of France for his safety. Although Louis had repeatedly aided Henry’s enemies, he was so powerful that the King of England had to respect his wishes.

Even then, Plantagenet resistance did not come to an end. Richard de la Pole seems to have been made of finer stuff than his brother, though left in poverty at Aachen as surety for his brother’s debts, constantly harassed by Edmund’s creditors following his attainder. Richard, however, managed to secure the protection of Erard de la Marck, Bishop of Liége, who delivered him from his straitened and dangerous circumstances. It was at this point, following his brother’s arrest, that he went to Hungary, where he lived for a time at the Court of Wladislas Jagiello II (1490-1516). This must have been because of his ties of kinship with the Royal Family of Hungary. Wladislas II’s consort and third wife, Anne of Foix-Candale, was related both to the King of France and the de la Pole family.

On 29 September 1502, Anne wed Wladislas at Székesfehérvár and she was crowned Queen of Hungary there that same day. Anne brought some members of the French court as well as French advisors with her to Hungary. These may have included Richard de la Pole and perhaps also his elder brother, Edmund. The relationship was happy at least from the king’s view, and he is reported to have regarded her as a friend, assistant and trusted advisor. She incurred debts in Venice and was said to favour this city all her life. In 1506, her signature was placed on a document alongside that of the king regarding an alliance with the Habsburgs. On July 23, 1503, Anne gave birth to a daughter, known as Anna Jagellonica, and on July 1, 1506, to the long-awaited male heir, the future king Louis II. She enjoyed great popularity, but her pregnancies ruined her health. She died in Buda on July 26, 1506, at the age of twenty-two, a little more than three weeks after the birth of her son, due to complications from the delivery.

Indeed, when the plan of his marriage to Anne was first broached, Wladislas thought she was an English princess. This belief was also held by those who were misled by the Queen of Hungary’s relationship with the de la Poles. Indeed, the English ambassador, Salisbury, had been present at Anna’s coronation at Székesfehérvár. Henry VII must have been worried by the presence of Richard de la Pole, the last pretender, in Buda, as he sent an envoy to Wladislas, asking him to surrender Richard. This Wladislas refused to do, instead lending financial aid to his English guest. Richard appears to have acquired a good military reputation while in Hungary, despite the disintegration of Matthias’s formidable mercenary army under the weak military leadership of Wladislas.

According to a note in the diary of Marino Sanuto, the ‘White Rose’ returned to Buda on 6 October 1506, and we know of a letter dated 14 April 1507 addressed to the Bishop of Liége from Richard. From these two documents, we know that Richard must have been in Hungary for at least six months. However, few details are known of his sojourn. We know that Thomas Killingworth, the loyal steward of the de la Pole family had settled Edmund’s financial matters in the Tyrol and also attended to Richard’s affairs in Buda. It seems that Richard left Buda in 1507, first for Austria and then for France. From there, he became a constant continental thorn in Henry VIII’s side as he had been in his father’s; in 1513 King Louis of France declared Richard to be the rightful King of England; in 1517 Richard was in Milan and Venice, and was rumoured to be launching an invasion from Denmark.

King Louis XII formally recognised Richard as the legitimate King of England, at Lyons, supporting his cause with men and money. In 1519 he sent Richard to Prague to plead on his behalf, in vain, to the young King Louis II of Hungary, and he also made preparations for an invasion of England in 1522-23, during another Anglo-French war. However, the invasion did not happen and Richard never set foot in England again. From 1522 he was back in Paris plotting with King Francis I. While the White Rose, as he was known, was at large, the threat of the House of York and the return of the wars of the Roses was always a very real one for the Tudors. But at the Battle of Pavia on 24th February 1525, Richard died as his ally Francis I was defeated at the hands of the Emperor Charles V. The emperor’s messenger told Henry VIII how ‘The White Rose is killed in battle … I saw him dead with the others’, to which Henry responded in joy ‘All the enemies of England are gone’. There is a portrait of Richard still preserved in Oxford bearing the inscription Le Duc de Susfoc dit Blanche Rose.

Only from a current-day perspective can we truly measure how rich the Gothic art of the Angevin period in Hungary was. During the course of the rapid changes in the architectural tastes of the sixteenth century and later over-enthusiastic reconstruction, a whole series of Gothic masterpieces became hidden under the ruins. In the magnificent Renaissance palace of Visegrád, archaeologists have dug up ornamental carvings, broken into small pieces, from the foundations of the fountain structure dating from the reign of Matthias Corvinus; in the Castle of Buda, their spades unearthed a ‘cemetery of statues’ from the Angevin period.

Before the ‘New World Discoveries’ of the late fifteenth century, England was little more than a small island state on the fringes of Europe. At the time of Matthias Corvinus, the populations of England and Hungary were roughly equal. Five centuries later, the population of England was five times that of Hungary. In the sixteenth century, the lines of power in Europe were redrawn by the Discoveries. As Atlantic trade expanded dramatically, the once proud Adriatic declined into an insignificant waterway on the periphery of the Mediterranean. Dalmatian ports like Genoa that had been resplendent city-states began to lose their economic, political and cultural significance. Venice was still experiencing its golden age, but it was about to go into a long period of decline. The Iberian peninsula had already begun to replace Italy as the centre of economic power, and the textile industry in England had already begun the country’s proto-industrial transition. This period has also been called the long sixteenth century, arching from the middle of the 1400s to the 1630s, making wage labourers out of serfs throughout northwestern Europe in new centres where the citizenry, tolerated only in some places under feudalism, had begun to forge weapons for future economic victory. In the wake of overseas discoveries and conquests, a surplus of precious metals suddenly replaced the previous scarcity of these in Europe, while prices and the terms of trade underwent a significant realignment.

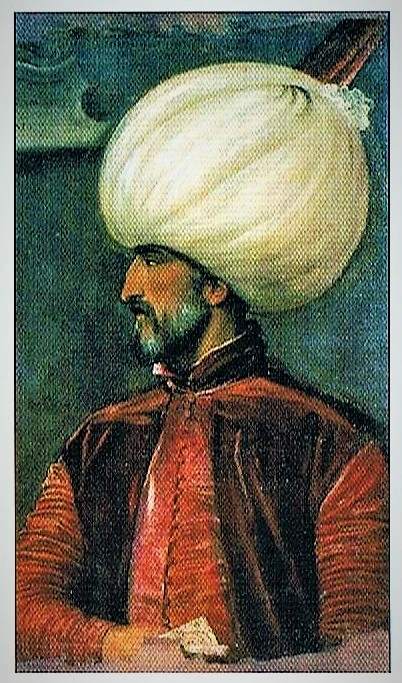

In 1512, England was again at war with France. So long as Henry VII lived, Edmund de la Pole was safe, but when Henry VIII succeeded to the throne and his brother Richard attempted, with the aid of France, to raise a rebellion against this second Tudor ‘imposter’, Henry had Edmund executed. When Edmund was beheaded in 1513, Richard took the title of Earl of Suffolk and openly laid claim to the throne of England from that time. In Hungary, meanwhile, the greediness of the Szapolyai-Werbőczi faction, which triumphed over the peasants in 1514, deprived the ‘Fuggers’ of their mining concessions, which in turn “forgot” to pay the miners’ wages. A miners’ uprising, therefore, followed that of the peasants, similarly ending in defeat and vengeance. However, the outcome of these events for the country was that there was no money left to finance the war against the Turks, even though the fortified towns in the south were falling to them one after the other. The warning bells rang in vain; even legendary Nándorfehérvár fell in 1521. Five years later, in 1526, Suleiman the Magnificent decided to wage an all-out military campaign, at a time when the shock of the brutal putting down of the 1514 peasant uprising by János Szapolyai still deeply pervaded the country.

The Debácle at Mohács:

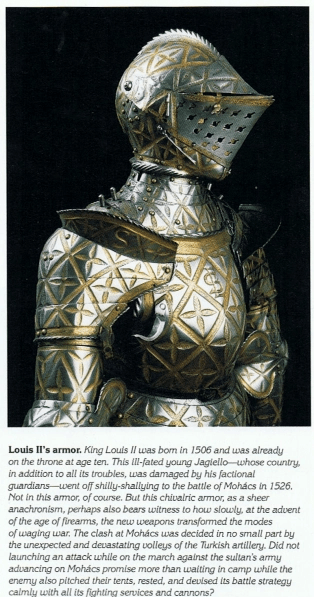

The son of Wladislas II, King Louis II (1516-1526), then a twenty-year-old, puny-looking youth, was able to dispatch a total of twenty-six thousand men to the south of Hungary; meanwhile, with his own small army of knights, he made a forlorn, heroic stand before the military juggernaut of Suleiman the Great, while waiting in vain for Szapolyai’s army of ten thousand coming from Transylvania. Historians still debate whether or not Szapolyai, who coveted the throne, was intentionally late. The Hungarian army did not attempt to block the strategically sensitive river crossings along the frontier; instead, it waited on an open field at Mohács and allowed the Turkish army with three or four times the number of troops and even greater firepower, to advance. The defeat was disastrous. The archbishops of Kalocsa and Esztergom, five bishops, enormous numbers of nobles and some ten thousand soldiers were killed. As Louis fled the battlefield, his horse stumbled into a swollen brook and rolled on top of the King. According to one version of what happened next, Louis was finished off by his own enraged nobles. His widow, Maria Habsburg, loaded his possessions on a boat and escaped upstream and then fled to the West, becoming an effective governor of the Netherlands before returning to Spain for her last years.

It may have been Wladyslaw II’s decision a few years later to give shelter to Richard de la Pole, the Tudors’ enemy as the last Yorkist claimant to the English throne, which turned the vindictive Henry VIII against the long-standing English alliance with Hungary. On the eve of the fateful Battle of Mohács of 1526, Louis II of Hungary addressed a letter to Henry VIII and Cardinal Wolsey, appealing for armed assistance. That such appeals went unanswered is evidenced by the fact that, for the next 160 years, Hungary lost its independence to Ottoman occupation on the one side of its territories, and Habsburg hegemony on the other. However, it is doubtful that this course of events could have been prevented even by the powerful Henry VIII. After 1526, however, the ‘old Hungarian glory’ grew dimmer in the public consciousness of England and Wales and the Anglo-Welsh monarchs viewed the rump of Hungary as little more than an Austrian province while maintaining links with independent Protestant Transylvania. Yet it seems that Wladislas II’s refusal to hand over Richard Plantagenet in 1506 was undoubtedly a factor in the refusal of the Tudors to lend support to Louis II in his fateful hour of need twenty years later.

Two further thorny White roses remained for the Tudors to deal with. Lady Katherine Gordon was Perkin Warbeck’s impoverished widow and a kinswoman of James IV of Scotland, who had been killed at the Battle of Flodden Field in 1513. Warbeck had pretended to be Edward, Duke of York, and was joined by many malcontents. He even received support from the King of Scotland, his relative, but was captured after a short time by Henry VII. He was imprisoned in the Tower and, when news of a fresh conspiracy reached Henry, he was hanged. Lady Katherine was granted permission to live at one of the confiscated Oxfordshire manors of the Pole family until death, provided that she did not visit Scotland or any other foreign country without a licence. After Warbeck, she married three times more. She was known as The White Rose of York and Scotland and died at the Oxfordshire manor in 1537, where she is buried together with her last husband.

The fact that all these pretenders managed to attract such powerful followings at home and abroad shows how fragile the Tudor royal dynasty really was, at least until 1525. Indeed, Henry VIII’s paranoia of the Plantagenets led him to carry on a vindictive campaign against the Pole family after Cardinal Reginald Pole, the son of the Countess of Salisbury, Margaret Pole, penned a stinging attack against the King’s divorce, from exile in Italy. This resulted in the execution of one of his brothers, William Pole, in 1539, and the suicide of the other. Margaret, the daughter of the Duke of Clarence, was an old woman in 1541, once the governess to Mary Tudor, whose mother’s betrothal to Arthur, Prince of Wales, had caused the execution of her brother, Edward Plantagenet, the rival claimant to the throne. Despite this, she became a loyal Tudor courtier. However, because she was a Neville, she was accused of complicity in the Northern Rebellion and sent to the Tower without trial. From there she was executed in May 1541, after ten or eleven blows of the axe. When Mary became Queen, her son became the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury. She herself was beatified by Pope Leo XIII in 1886. The extent of the reconciliation achieved by the end of the turbulent Tudor period is shown by the close friendship between Margaret’s granddaughter and Elizabeth I. However, descendants and relatives of the Poles continued to be implicated in, and executed for, plots against both Elizabeth and James I, the most significant being Robert Arderne, a relative of William Shakespeare, and the Wintour brothers, who were among the leaders of the 1605 ‘Gunpowder Plot’ and Midland Rebellion of the leading Catholic gentry.

Until recently, the conventional wisdom of Hungarian historians held that Mohács was a reversal of Hungarian national fortunes like that of Waterloo and Verdun to the French and Wagram to the Austrians. But in recent times, archaeologists stumbled across several long-looked-for mass graves on the battlefield. In 1526, Louis II first ordered the mobilisation of one-fifth of the serfs, then one-half, and finally all of them. But, perhaps due to the recollection of 1514, all this mobilisation failed to come about. The bulk of the dead identified from the mass graves at Mohács turned out to be foreign mercenaries. Though the ranks of Hungarian commanding officers suffered enormous casualties, the genuinely Hungarian forces remained nearly intact after the battle.

Taken together, the archaeological and documentary evidence calls into question the repeated mythological assertions made about the significance of the battle, such as…

‘Mohács is the burial ground of our national greatness…’

For his part, Suleiman could continue to pillage unimpeded with his army; he reduced tens of thousands to slavery. He even entered Buda Castle, which was left undefended. And what Queen Maria had not carried off, he loaded on boats and expropriated them, including Matthias Corvinus’s library. After that, he evacuated the castle, then the entire country and returned home. Having demonstrated his power to the Hungarians, he appeared willing to accept John Szapolyai as King John I (1526-1564). Almost to the very day of the first anniversary of the battle, Suleiman again pitched his tents on Mohács’s bloody fields and ordered Szapolyai into his presence, where ‘King John’ paid homage, kissing Suleiman’s hand.

In 1529, the Sultan’s army besieged Vienna. This was the high-water mark of their advance. Though they failed to take Vienna, the Turks’ gains confined the Habsburgs to Slovakia, Croatia and a thin strip of Hungarian territory along the Danube. This became a border area and the scene of skirmishes between the Turks and the Habsburgs for centuries to come.

Although the successors of Charles V enjoyed vast resources from their ‘New World’ conquests, they had to fight on two fronts, against the ‘infidel Muslims’ in the East and the ‘heretical Protestants’ in the West.

Sources:

Most of the evidence for this article comes from the original research of Sándor Fest (1883-1944) and his papers published in From Saint Margaret of Scotland to the Bards of Wales: Anglo-Hungarian Historical and Literary Contacts (Universitas Kiadó, 2000). Fest was educated at the Eötvös College of Budapest University and became the first professor of English Studies at Budapest University in 1938. He was a pioneer in the study of Anglo-Hungarian historical and literary contacts and generally promoted the cause of English studies in Hungarian higher education in the inter-war years. In doing so, he was swimming against the pro-German cultural tide which was beginning to swamp Hungary.

Most of the material for this article has been collected from scholarly publications and papers, some of them written in Hungarian and translated into English, which are largely unavailable today. In my recent articles on ‘the Bohemian Connection’, as well as this one, I have also included material from my own research, published online, into the Golafre/ Golliver/ Gulliver family, whose ‘fortunes’ were linked to the Plantagenets from Richard II to the Earl of Lincoln, John de la Pole, the elder brother of Edmund and Richard de la Pole, who was killed in battle at Stoke Field in 1487. According to the DNB, Lincoln’s third wife was a member of the Golafre family, although there is little contemporary information recorded about her. For further information, please see the link below:

Goerge Taylor & J. A. Morris (c. 1938), A Sketch-Map History of Britain and Europe, 1485-1783. London: Harrap.

Simon Hall & John Haywood (ed.) (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British & Irish History. London: Penguin Books.

András Bereznay, et. al. (1998), The Times Atlas of European History. London: Times Books (HarperCollinsPublishers.)

Lásló Kontler (2009), A History of Hungary. Budapest: Atlantisz Publishing House.

István Lázár (1988), One Thousand Years: A Concise History of Hungary. Budapest: Corvina.

István Lázár (1989), An Illustrated History of Hungary. Budapest: Corvina Books.